Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We propose the Multi-granularity Attention Network (MA-Net), featuring three dedicated modules: the Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) for capturing structural details, the Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) for adaptive cross-scale fusion, and the Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) for background suppression.

- MA-Net achieves state-of-the-art performance on two public benchmarks, with an overall accuracy of 93.12% on FGSC-23 and 98.40% on FGSCR-42, significantly outperforming existing methods in fine-grained ship classification.

What are the implication of the main findings?

- The framework provides a robust, end-to-end solution for precise ship identification, with direct utility in maritime surveillance, traffic monitoring, and defense applications.

- Its core innovations—adaptive local attention and dynamic multi-granularity fusion—offer a transferable blueprint for advancing fine-grained classification in broader remote sensing target recognition tasks.

Abstract

The classification of ship targets in remote sensing images holds significant application value in fields such as marine monitoring and national defence. Although existing research has yielded considerable achievements in ship classification, current methods struggle to distinguish highly similar ship categories for fine-grained classification tasks due to a lack of targeted design. Specifically, they exhibit the following shortcomings: limited ability to extract locally discriminative features; inadequate fusion of features at high and low levels of representation granularity; and sensitivity of model performance to background noise. To address this issue, this paper proposes a fine-grained classification framework for ship targets in remote sensing images based on Multi-Granularity Attention Network (MA-Net), specifically designed to tackle the aforementioned three major challenges encountered in fine-grained classification tasks for ship targets in remote sensing. This framework first performs multi-level feature extraction through a backbone network, subsequently introducing an Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) module. This module employs dynamic overlapping region segmentation techniques to assist the network in learning spatial structural combinations, thereby optimising the representation of local features. Secondly, a Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) module is designed to dynamically fuse feature maps of varying representational granularities and select key attribute features. Finally, a Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) method is developed to effectively highlight target detail features, thereby enhancing feature expression capabilities. On the public FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets, MA-Net attains top-performing accuracies of 93.12% and 98.40%, surpassing the previous best methods and establishing a new state of the art for fine-grained classification of ship targets in remote sensing images.

1. Introduction

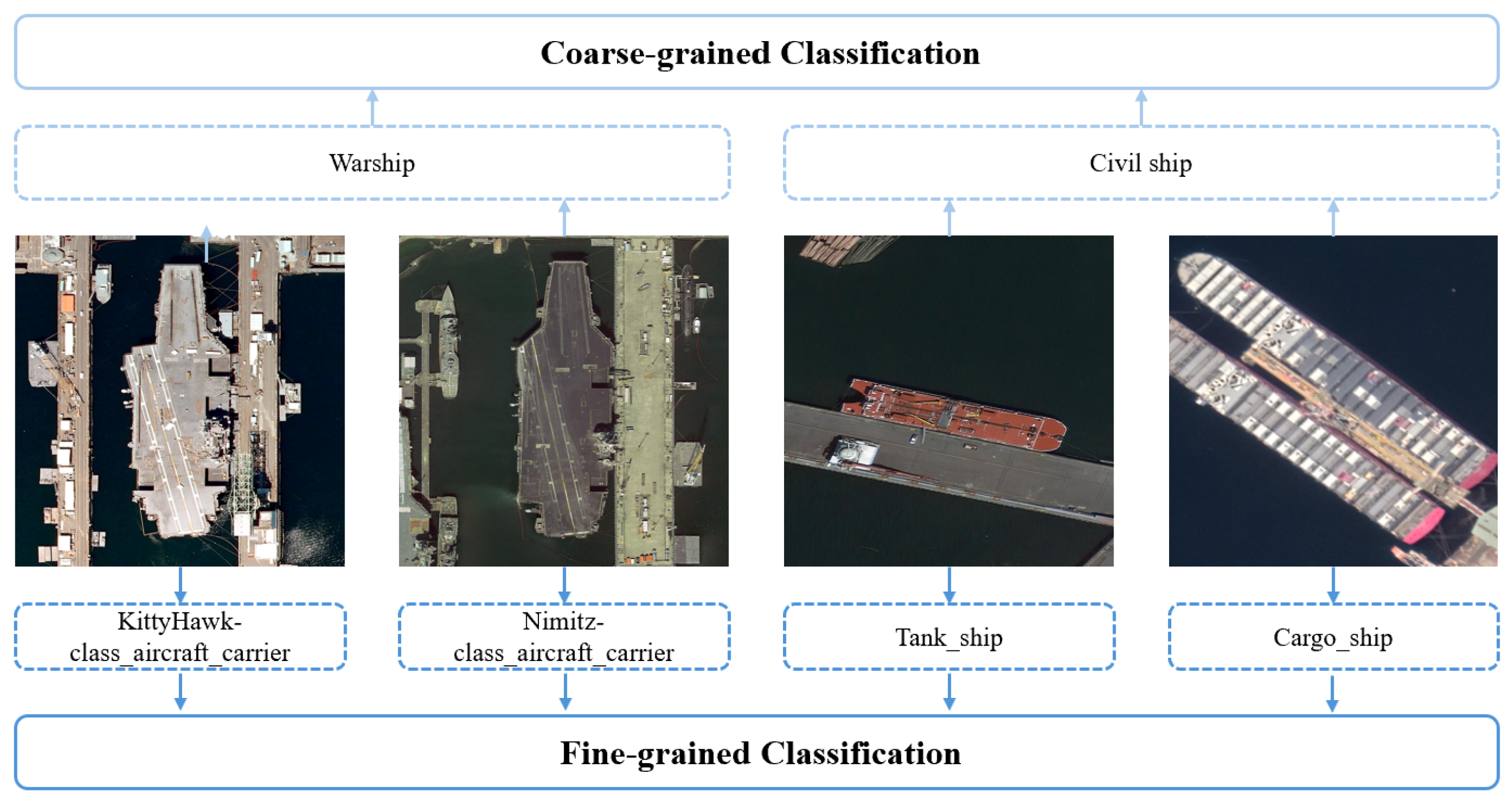

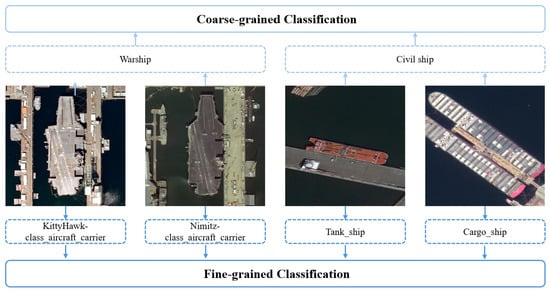

The classification of targets in remote sensing images is a core task for scene interpretation and automated analysis, which aims to assign semantic labels to observed targets. This task is broadly divided into two levels: coarse-grained classification, which distinguishes objects across broad categories (e.g., warship vs. civil ship), and fine-grained classification, which discriminates between subcategories with highly similar visual appearances. Spurred by the growing demand for precise target analysis in maritime surveillance and bolstered by advances in high-resolution imaging, fine-grained classification has emerged as a critical research frontier. As illustrated in Figure 1, this task requires the model to discern subtle, often minute, visual distinctions between subclasses, presenting a significantly greater challenge than its coarse-grained counterpart.

Figure 1.

Comparison between coarse-grained classification and fine-grained classification in RSIs.

The fine-grained classification of ship targets in remote sensing images is a task that faces pronounced challenges. First, the high inter-class similarity and low inter-class variance among subordinate ship types (e.g., different models of container ships or destroyers) demand an exceptional ability to capture and represent subtle, localized discriminative features. The model must focus on fine structural details rather than global shape, which is often similar across classes. Second, significant scale variations occur due to differing imaging altitudes and sensor resolutions, causing the same ship class to appear at vastly different sizes. This requires the model to effectively integrate and reason across multi-granularity features, from fine-grained textures to coarse-grained hull shapes. Third, complex background interference from waves, wakes, docks, and other maritime clutter can obscure target boundaries and introduce distracting features, diverting the model’s attention from the ship itself. Suboptimal imaging conditions, sensor noise, and viewpoint changes further exacerbate these difficulties.

Recent research in fine-grained classification has focused primarily on identifying such discriminative regions. Techniques range from strongly supervised methods that require extensive part annotations [1,2,3] to weakly supervised methods that use attention mechanisms [4,5,6]. The latter, along with strategies that fuse multi-level features to suppress background noise [7,8,9], have shown promise. However, a critical gap remains: these methods are generally designed for natural objects (e.g., birds or cars) and fail to account for the unique characteristics of remote sensing targets, particularly ships.

To address the core challenges in remote sensing scenarios, research in this field primarily adopts three deep learning-based approaches. These include contrastive learning-driven feature optimization [10,11,12], attention-based fine-grained feature extraction [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], and interpretability-enhanced frameworks leveraging large models [21,22]. While acknowledging difficulties like intra-class variation and complex backgrounds, these methods often do not fully exploit the inherent properties of man-made targets like ships. Unlike natural objects with flexible poses, ships are rigidly assembled entities with fixed spatial layouts of structural components (e.g., the superstructure’s consistent location). This prior is underutilized, leading to three specific shortcomings that directly correspond to the aforementioned challenges: (1) Constrained local feature expression: Models lack a mechanism to explicitly learn the spatial structural relationships between ship components, limiting their ability to capture definitive local details essential for distinguishing highly similar classes. (2) Insufficient multi-granularity feature fusion: While multi-scale features are extracted, their fusion is often static or heuristic, unable to adaptively and dynamically integrate fine details with coarse semantics crucial for handling scale variations. (3) Susceptibility to background interference: Feature learning can be dominated by complex maritime backgrounds, reducing focus on the target itself.

To address these three intertwined problems, this paper proposes the Multi-Granularity Attention Network (MA-Net), a novel framework specifically tailored for the fine-grained classification of ships in remote sensing imagery. MA-Net introduces three dedicated components, each designed to address one core challenge. The Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) module addresses the constrained local feature expression by employing dynamic, overlapping region segmentation and local self-attention, enabling the network to learn precise spatial assembly relationships of ship parts. The Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) module overcomes insufficient fusion by adaptively integrating feature maps from different semantic levels using learnable weights and channel attention, ensuring that both fine and coarse discriminative cues are effectively combined. The Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) method mitigates background interference by generating attention-guided masked images during training, forcing the model to focus on the most discriminative target regions and enhancing feature robustness.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- 1.

- We propose MA-Net, a novel framework for fine-grained ship classification that explicitly addresses the domain-specific challenges of remote sensing targets through three synergistic modules: ALFA, DMGFF, and FBDA.

- 2.

- The ALFA module captures refined local features and spatial structural relationships of rigid ship assemblies via an adaptive overlapping patch extraction strategy and local self-attention.

- 3.

- The DMGFF module enables dynamic, context-aware fusion of multi-granularity features, allowing the model to emphasize the most relevant visual cues from different scales adaptively.

- 4.

- The FBDA method enhances feature discriminability and model robustness by performing data augmentation directly on feature-space attention maps, effectively suppressing background noise.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews related works. Section 3 details the methodology of the proposed MA-Net. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, results, comparative analysis with state-of-the-art methods, ablation studies, and visualization analysis. Section 5 provides a discussion of the findings, implications, and limitations of the work. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Fine-Grained Classification in Natural Images

For fine-grained classification of natural images, the wide variation in animal poses and viewing angles presents a significant challenge to the alignment of discriminative feature regions. To address this, two primary methodological paradigms have emerged: strongly supervised and weakly supervised learning.

Strongly supervised approaches rely on additional manual annotations, including object bounding boxes and part landmarks, alongside category labels, to guide the model toward relevant regions during training. Early works in this paradigm [23,24,25,26,27] integrate this additional information to build sophisticated models, substantially improving the accuracy of classification. However, their heavy dependence on costly and labor-intensive fine-grained annotations severely limits their scalability and practical application in domains where such detailed annotations are difficult to obtain.

In contrast, weakly supervised methods require only image-level labels and are further divided into location-based and attention-based strategies. Location-based methods [28,29] typically employ object detection techniques to first identify semantic parts within an image. Attention-based methods [30,31,32,33,34] learn to localize discriminative regions directly by estimating attention scores on the feature map. For example, Rao et al. [34] devise a counterfactual attention mechanism to reduce the influence of background noise, leading to a more precise region localization. To capture features at multiple semantic levels, Wang et al. [8] propose a Part-Sampling Attention (PSA) module that systematically samples implicit part representations throughout the feature hierarchy. A common shortcoming of these weakly supervised strategies is their lack of explicit geometric or structural constraints, which can lead to imprecise or unstable localization, especially when dealing with objects that have a well-defined internal structure.

Beyond these, there are also network-based integration strategies [35,36,37], which either partition a dataset into similar subsets for specialized classifiers or ensemble multiple networks to improve overall fine-grained classification performance. While often effective, these strategies can significantly increase model complexity and computational overhead, making them less efficient for deployment.

Crucially, the majority of the aforementioned methods are designed for and evaluated on natural images (e.g., birds, cars). They are not directly suitable for fine-grained classification in remote sensing imagery, such as ships, due to fundamental domain differences. Natural objects exhibit flexible poses and viewpoints, whereas man-made targets like ships have rigid structures with fixed spatial layouts of components. Methods that search for or attend to “parts” in a flexible manner fail to leverage this inherent structural prior. Furthermore, remote sensing images present unique challenges like complex backgrounds, smaller target sizes relative to the image, and different imaging artifacts, which are not the primary focus of these general-purpose fine-grained models.

2.2. Fine-Grained Classification of Ship Targets in Remote Sensing Images

Recent advances in fine-grained classification of ship targets in remote sensing are predominantly driven by deep learning. The introduction of dedicated benchmark datasets, such as FGSC-23 [16] and FGSCR-42 [38], has further facilitated this shift, moving the field away from traditional handcrafted-feature methods toward data-driven learning paradigms.

To address the distinct challenges of remote sensing scenarios—including high intra-class variance, low inter-class similarity, and complex background clutter—a common approach focuses on extracting discriminative local features while suppressing irrelevant background information. For instance, Han et al. [19] propose EIRNet, which integrates multi-scale features from the backbone network to reduce background interference while preserving structural details of the target. Similarly, Sun et al. [39] design a dual-branch Transformer fusion network to effectively combine local and global information through a dedicated feature fusion module. Beyond architectural innovations, some studies introduce higher-level conceptual frameworks. Xie et al. [17] proposed DRNet for remote sensing fine-grained object detection, which integrates spatial and channel attention into a dedicated parallel fine-grained branch for feature dual refinement. Xiong et al. [21] develop a cognitive network that mimics an expert’s reasoning process from perception to cognition, offering interpretable predictions via visualized correlation scores and activation regions. Chen et al. [10] propose a push–pull network based on asynchronous contrastive learning, which tackles high inter-class similarity through a decoupling-then-aggregation strategy. Additionally, for low-resolution imagery, super-resolution techniques have been adopted to aid fine-grained classification [40].

Despite these contributions, existing methods still exhibit three key limitations when applied to ship targets in remote sensing imagery. First, their ability to represent local features is often limited, lacking explicit modeling of the rigid spatial assembly relationships inherent to ship structures. Second, while multi-level features are commonly fused, the fusion strategies tend to be static or heuristic, lacking adaptive mechanisms to dynamically align fine details with coarse semantic cues. Third, such methods remain vulnerable to background interference, as complex maritime environments can dominate the feature representation. Therefore, there is a clear need for a tailored framework that systematically addresses these interconnected challenges in remote sensing fine-grained ship classification.

3. Methodology

This section introduces the MA-Net model for fine-grained classification of ship targets in remote sensing images.The section is divided into four parts: In Section 3.1, we propose the overall framework of MA-Net, which integrates a backbone network, an Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) module, a Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) module, and an Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) method. In Section 3.2, the ALFA module is proposed as a means to optimise local structural details. In Section 3.3, the DMGFF module is introduced, which integrates multi-granularity information and emphasises key channels. Finally, in Section 3.4, the FBDA method applied during training is described, with the aim of further enhancing feature discriminative power.

3.1. Overview of the Framework

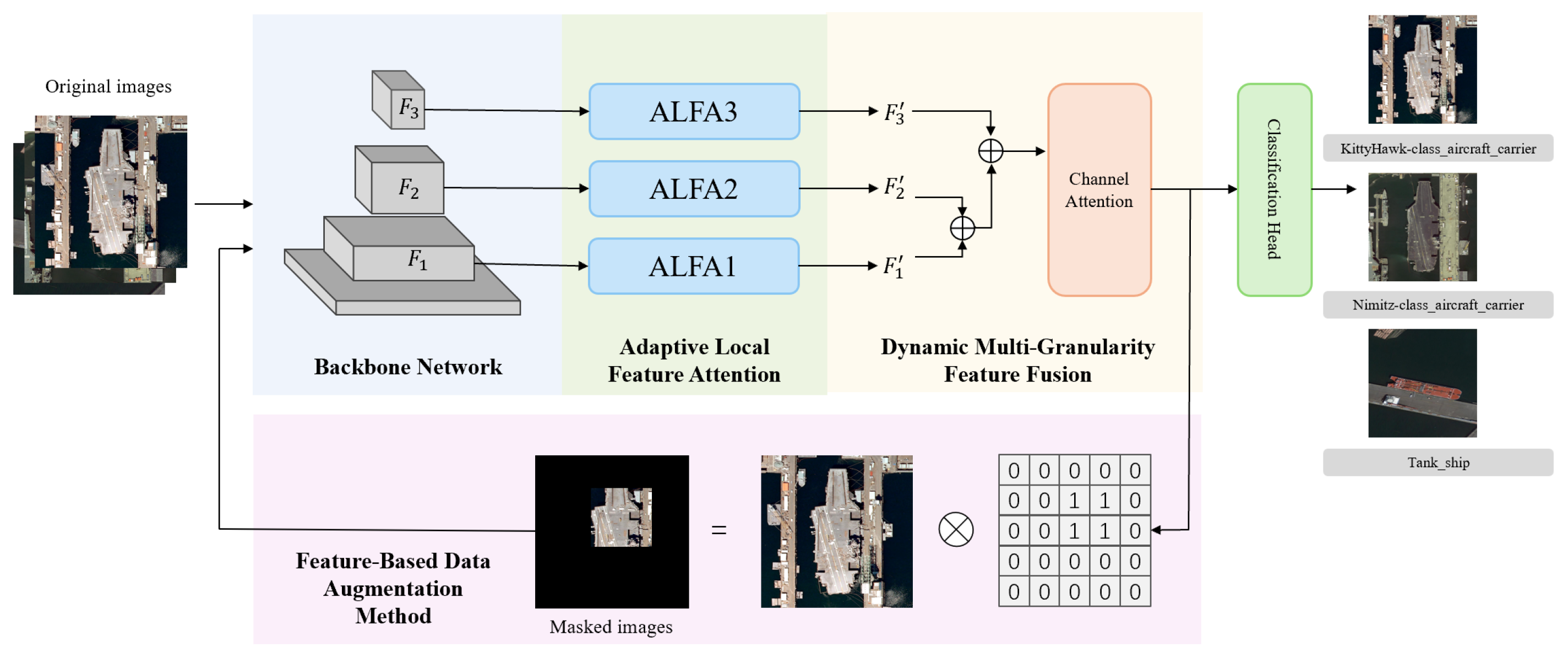

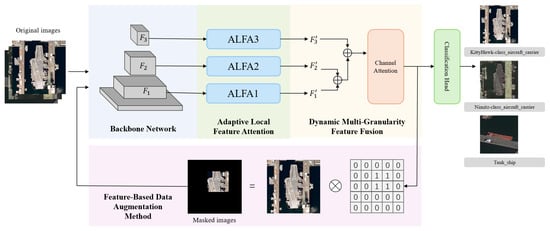

As shown in Figure 2, the proposed framework, termed the Multi-Granularity Attention Network (MA-Net), is designed to hierarchically capture discriminative features across multiple scales for precise fine-grained ship classification. The process is initiated with a convolutional backbone (ResNet50) to extract a pyramid of feature maps across multiple stages. We denote the top three feature maps from shallow to deep as , , and . These maps exhibit increasing semantic abstraction and decreasing spatial resolution, encompassing information from fine-grained local details to coarse-grained global structures.

Figure 2.

The overview of MA-Net. Multi-level feature maps are extracted from the backbone network, after which the Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) module learns discriminative local features across different granularity levels. Subsequently, the Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) module performs feature integration and channel selection, ultimately enabling classification. Concurrently, the Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) method generates a masked image to form a parallel training branch. The final prediction and total loss are computed as weighted combinations of the outputs from both the original and masked branches. Legend: ⊕ denotes feature fusion, ⊗ denotes element-wise multiplication.

To address the specific limitations outlined earlier, each feature map is processed by three dedicated modules. First, the Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) module refines , , and to enhance constrained local feature expression. It achieves this by explicitly learning the spatial assembly relationships of ship parts through adaptive patch segmentation and local self-attention, yielding refined feature maps , , and .

Subsequently, the Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) module tackles the problem of insufficient multi-granularity association. It dynamically and adaptively fuses the outputs from ALFA (, , ) using learnable weights and channel attention mechanisms. This process ensures that complementary cues from different semantic levels are effectively integrated.

To enhance robustness, the Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) method leverages attention maps from the DMGFF module to create a masked version of the input. The model is then optimized using a weighted combination of the predictions and losses from both the original and the masked branches.

3.2. Adaptive Local Feature Attention

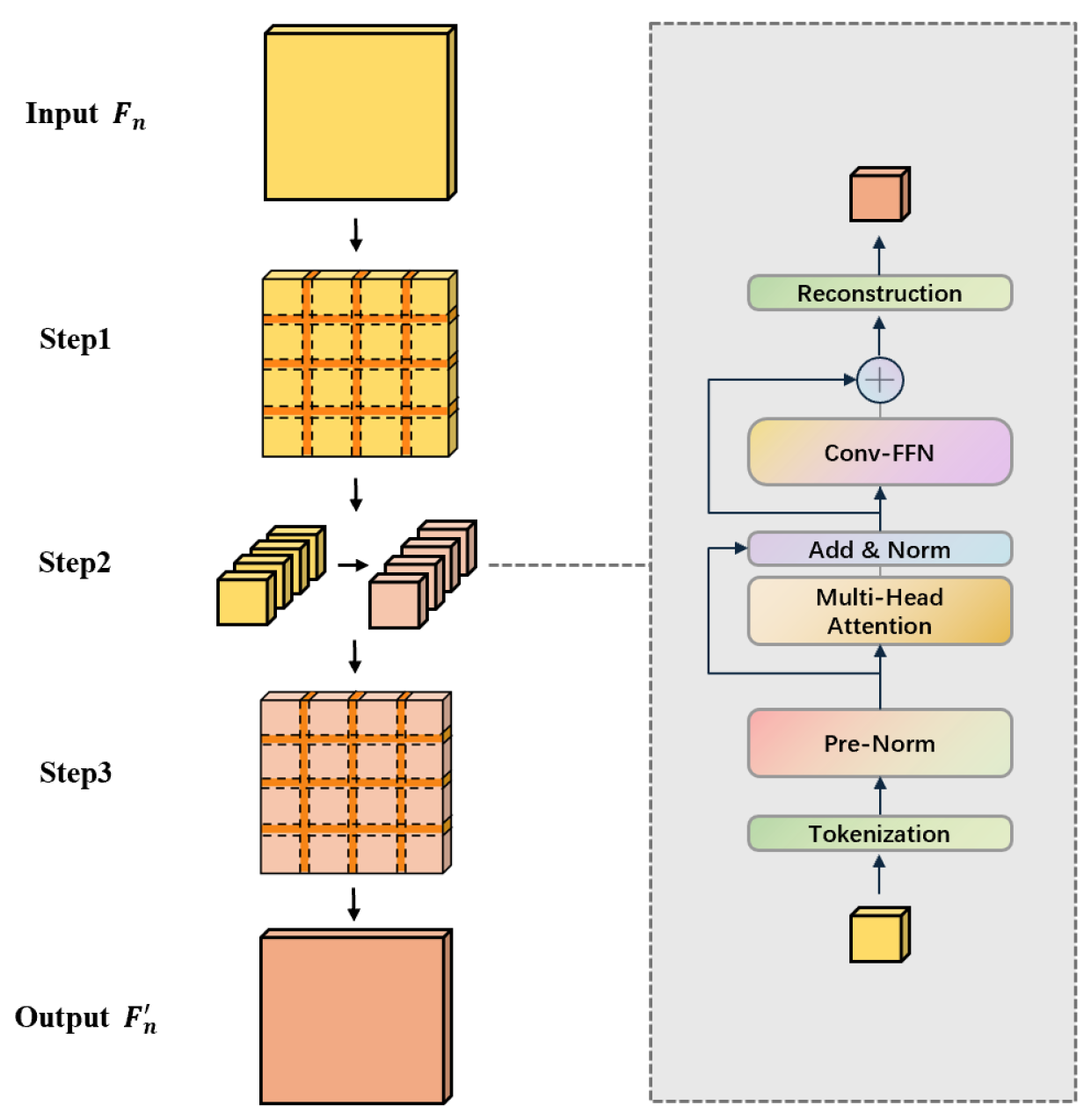

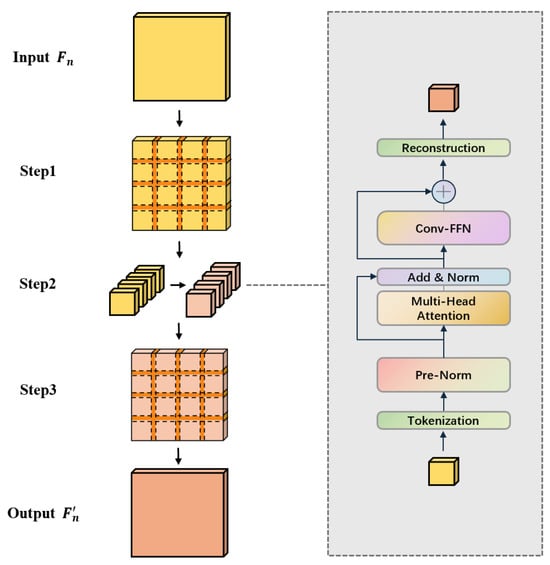

The Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) module is designed to capture fine-grained, part-specific details by adaptively focusing on localized regions within feature maps. Given an input feature map , where B, C, H, and W denote batch size, channels, height, and width, respectively, ALFA processes it through three core stages, as illustrated in Figure 3: Complexity-aware Patch Partition, Local Self-Attention, and Feature Aggregation and Enhancement.

Figure 3.

The three-step workflow of the Adaptive Local Feature Attention (ALFA) module: (1) Complexity-aware Patch Partition, (2) Local Self-Attention, and (3) Feature Aggregation and Enhancement.

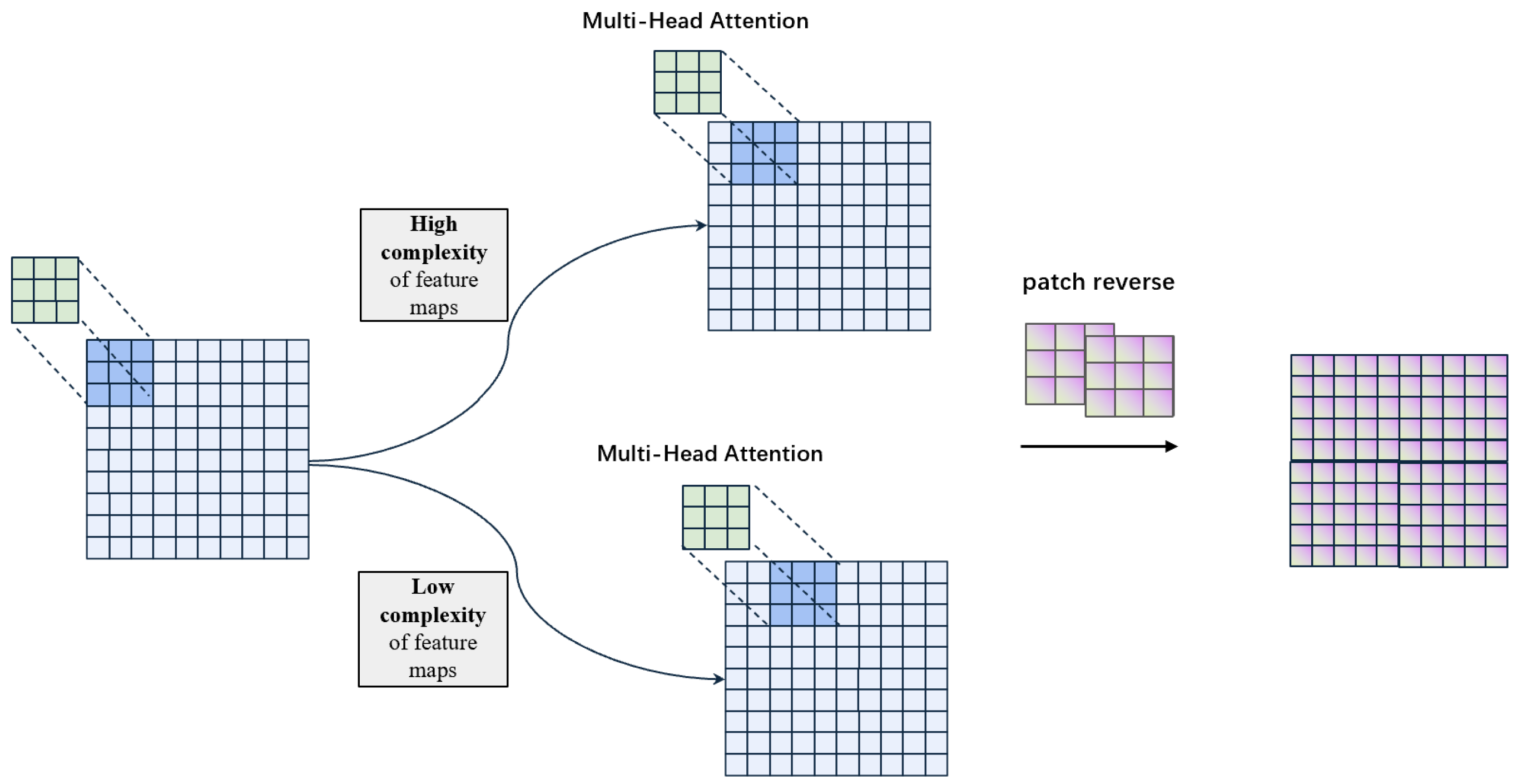

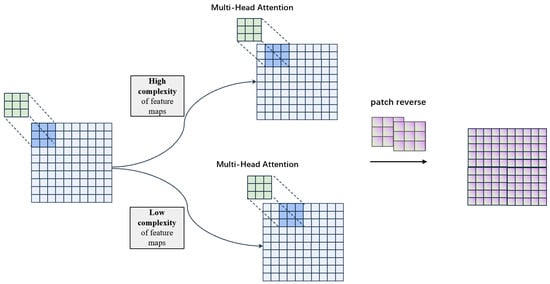

As shown in Figure 4, to overcome the limitation of fixed grid partitioning, we propose an adaptive strategy that dynamically adjusts the sampling step size based on local feature complexity. This ensures detailed regions are sampled densely while smooth regions are covered with larger strides for efficiency.

Figure 4.

Adaptive overlapping patch extraction strategy.

First, we define a feature complexity measure for the input feature map. We compute the spatial standard deviation across channels, which reflects the activation variance and indicates textural richness:

where computes the standard deviation over spatial dimensions . Higher values of indicate more complex local structures requiring finer analysis.

Given a predefined patch size , the adaptive step size s is computed as

where is the minimum step size, is the maximum step ratio, and is a scaling factor. This formulation ensures s decreases with increasing complexity.

The feature map is then partitioned into overlapping patches with size using the adaptive step s. Formally, for each starting position ,

where is the total number of patches, and , are the grid dimensions. This yields a patch tensor .

Each patch is flattened into a sequence of tokens and processed by a pre-Norm transformer block to model intra-patch dependencies. The block consists of a multi-head self-attention (MSA) layer and a convolutional feed-forward network (Conv-FFN).

Let represent the token sequence of a patch (, ). The pre-Norm operation is applied before each sub-layer:

The multi-head self-attention with h heads computes

with projection matrices , , and . Here, . The attention function uses scaled dot-product:

A residual connection is added:

The ConvFFN enhances the representation with local spatial context:

where ConvFFN comprises two linear layers and a depth-wise convolution with GELU activation, operating on the restored spatial layout of the patch.

Processed patches are reassembled into the original feature map resolution via a weighted averaging operation in overlapping regions:

where denotes the reverse patching function that accumulates contributions from overlapping patches and normalizes by the overlap count.

Finally, the aggregated feature map undergoes a global Conv-FFN to integrate information across all spatial positions:

The complete ALFA transformation for a single-scale feature is summarized as

3.3. Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion Module

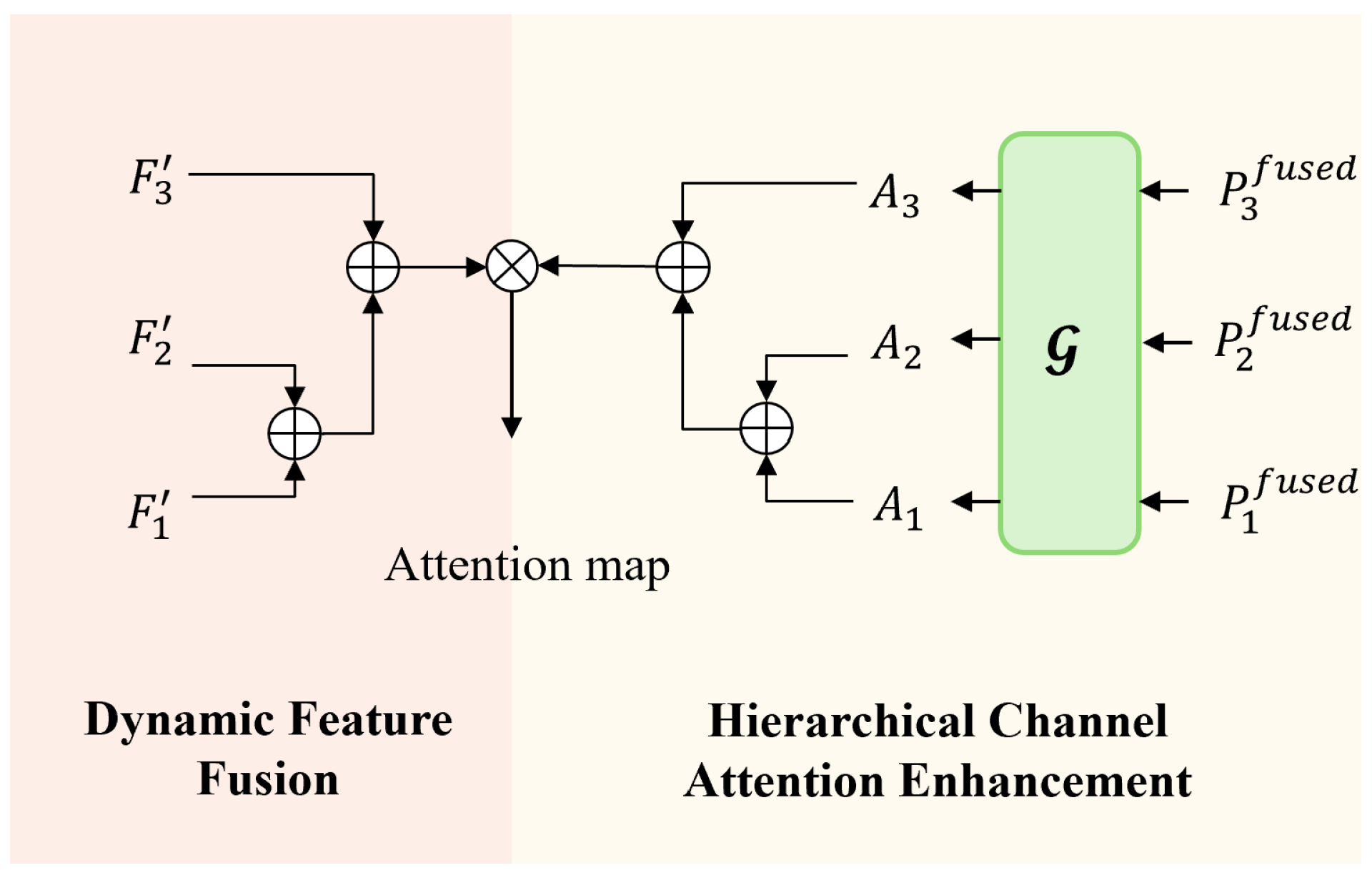

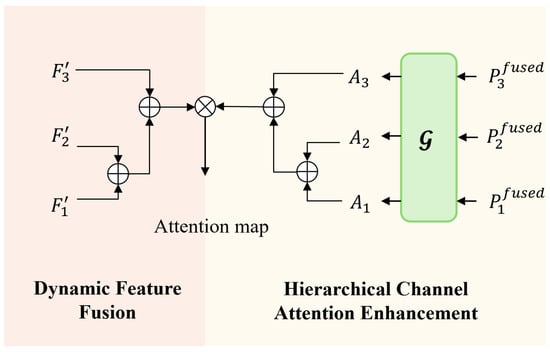

The Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) module (Figure 5) is designed to adaptively integrate multi-scale feature representations from the ALFA-enhanced feature maps . Unlike traditional feature pyramid networks that employ fixed fusion strategies, DMGFF introduces two key innovations: (1) learnable fusion weights that dynamically adjust the contribution of different granularities, and (2) hierarchical channel attention that propagates discriminative cues across scales.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the Dynamic Multi-Granularity Feature Fusion (DMGFF) Module.

Given three ALFA-enhanced feature maps , , and (from fine to coarse granularity), the DMGFF module first aligns their channel dimensions to a unified dimension M through convolutions. For the coarsest feature , we additionally apply a Feature Pyramid Attention (FPA) operation to incorporate global context:

where GAP denotes global average pooling. For the finer features, we use

All aligned features are further refined with convolutions: .

To overcome the limitations of fixed fusion ratios, we introduce learnable fusion weights that adapt to each input sample. The fusion proceeds in a bottom-up manner, progressively integrating fine details into coarser representations. The fusion between adjacent levels is computed as

where is the sigmoid function ensuring weights in , and denotes bilinear upsampling. This design enables the model to dynamically decide how much fine-grained information should flow to coarser levels based on the specific characteristics of each ship target.

To enhance feature discriminability, we apply a hierarchical channel attention mechanism. For each pyramid level , channel attention weights are computed via a ChannelGate module that consists of global average pooling followed by two convolutions with a ReLU activation between them. These attention weights are then propagated upward using the same fusion weights :

This ensures consistency between feature fusion and attention propagation. The final output is obtained by applying the refined attention to the coarsest feature and projecting it to the output dimension:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

The DMGFF module thus provides a flexible and adaptive mechanism for multi-granularity feature integration, which is crucial for fine-grained ship classification where discriminative features may appear at varying scales. By dynamically balancing contributions from different granularities and propagating discriminative channel attention across scales, DMGFF effectively captures both local details and global semantics.

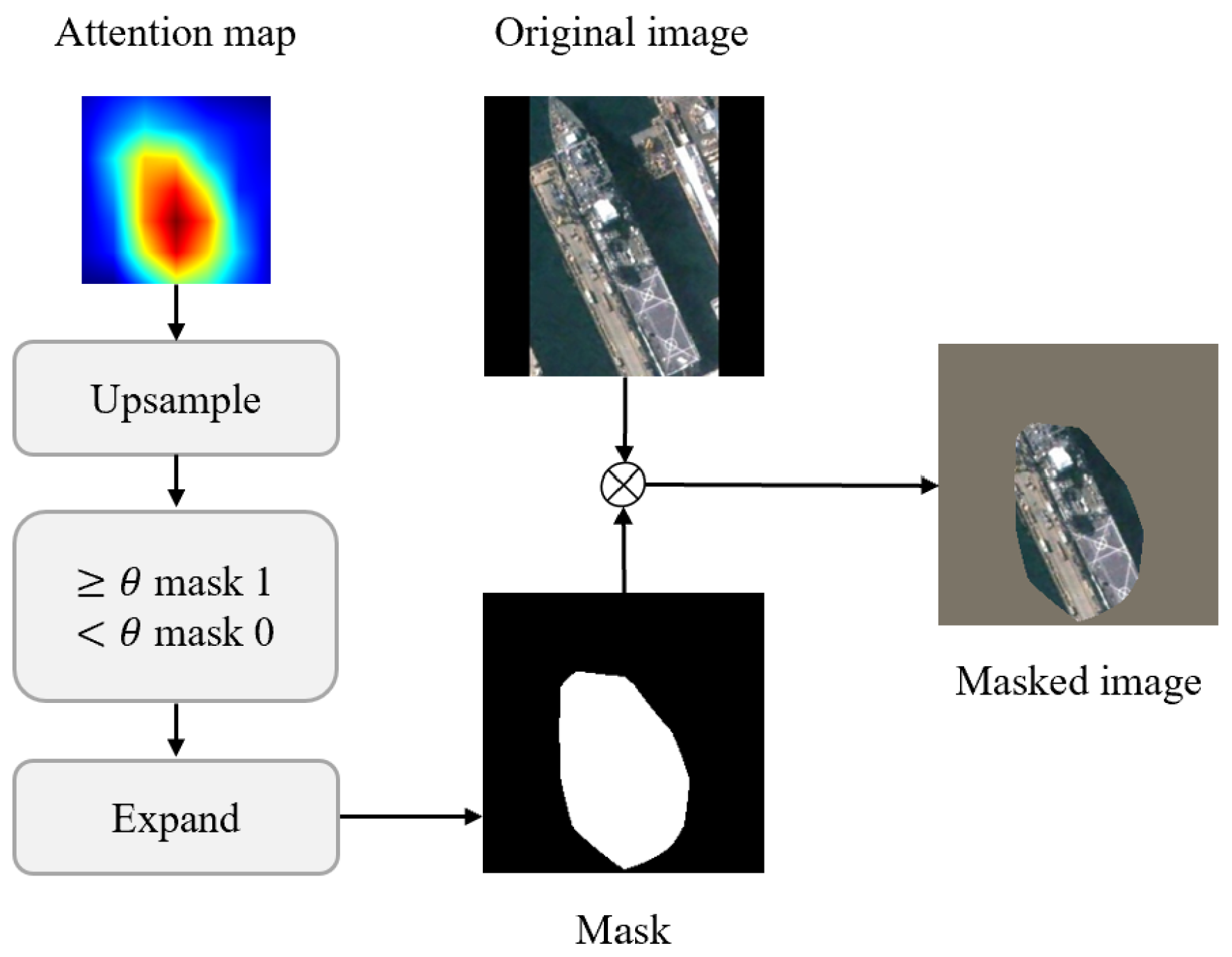

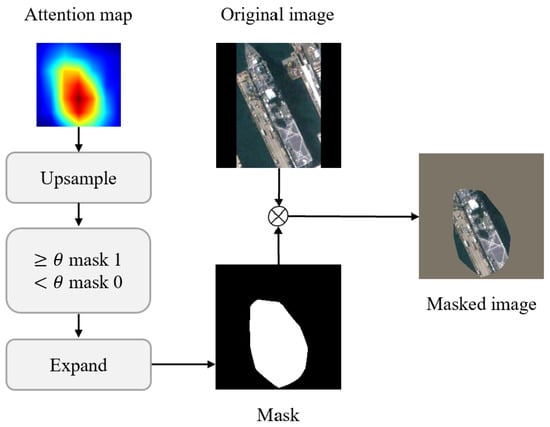

3.4. Feature-Based Data Augmentation Method

To enhance the model’s focus on discriminative regions and improve robustness against background noise, we propose a novel Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) strategy. This method leverages the attention maps generated by the DMGFF module to create attention-aware masked versions of input images, which emphasize salient regions while suppressing less informative areas.

As shown in Figure 6, given an input image and its corresponding attention map from the DMGFF module, we first upsample the attention map to match the input image dimensions:

Figure 6.

The pipeline of the Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) method: from attention maps to masked images for enhanced feature learning. The masked region in the masked image appears gray due to the standard ImageNet normalization applied to the input image.

We then compute a dynamic threshold to distinguish between high-attention and low-attention regions:

where denotes uniform random sampling between and , and represents the attention map for the i-th sample in the batch.

The binary mask is then generated by comparing the upsampled attention map with the threshold:

where is the indicator function. The mask is expanded to match the channel dimension of the input image:

Finally, the masked image is obtained by element-wise multiplication:

where ⊙ denotes multiplication by element. This operation effectively sets low-attention regions to zero while preserving high-attention regions.

During training, both the original image and its masked version are fed into the network. The network parameters are shared between the two pathways. Let represent the MA-Net model with parameters . The predictions for the original and masked images are

The final prediction is computed as the weighted average of both predictions:

Correspondingly, the loss function also adopts a weighted combination. Given a classification loss function (cross-entropy) and ground truth labels , the total loss is calculated as follows:

where is an adjustable hyperparameter that controls the relative importance of the original image features and the masked image features during training.

4. Experiments and Results

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed MA-Net framework in addressing the challenging task of fine-grained ship classification within remote sensing imagery, a comprehensive experimental protocol was established. The primary objectives of these experiments were threefold: first, to quantitatively validate the overall classification performance of MA-Net against current state-of-the-art methods; second, to systematically dissect and assess the individual contribution of each novel component—ALFA, DMGFF, and FBDA—through ablation studies; third, to qualitatively analyze the model’s behavior and learned feature representations to provide interpretative insights. This rigorous evaluation was conducted on two publicly available and widely recognized benchmark datasets in the remote sensing domain: the FGSC-23 dataset and the more challenging FGSCR-42 dataset. The selection of these datasets ensures a robust assessment under varying conditions, including different numbers of fine-grained categories, diverse ship types, and complex maritime backgrounds, thereby thoroughly examining the model’s generalization capability and practical utility.

4.1. Datasets and Metrics

4.1.1. Introduction to Experimental Datasets

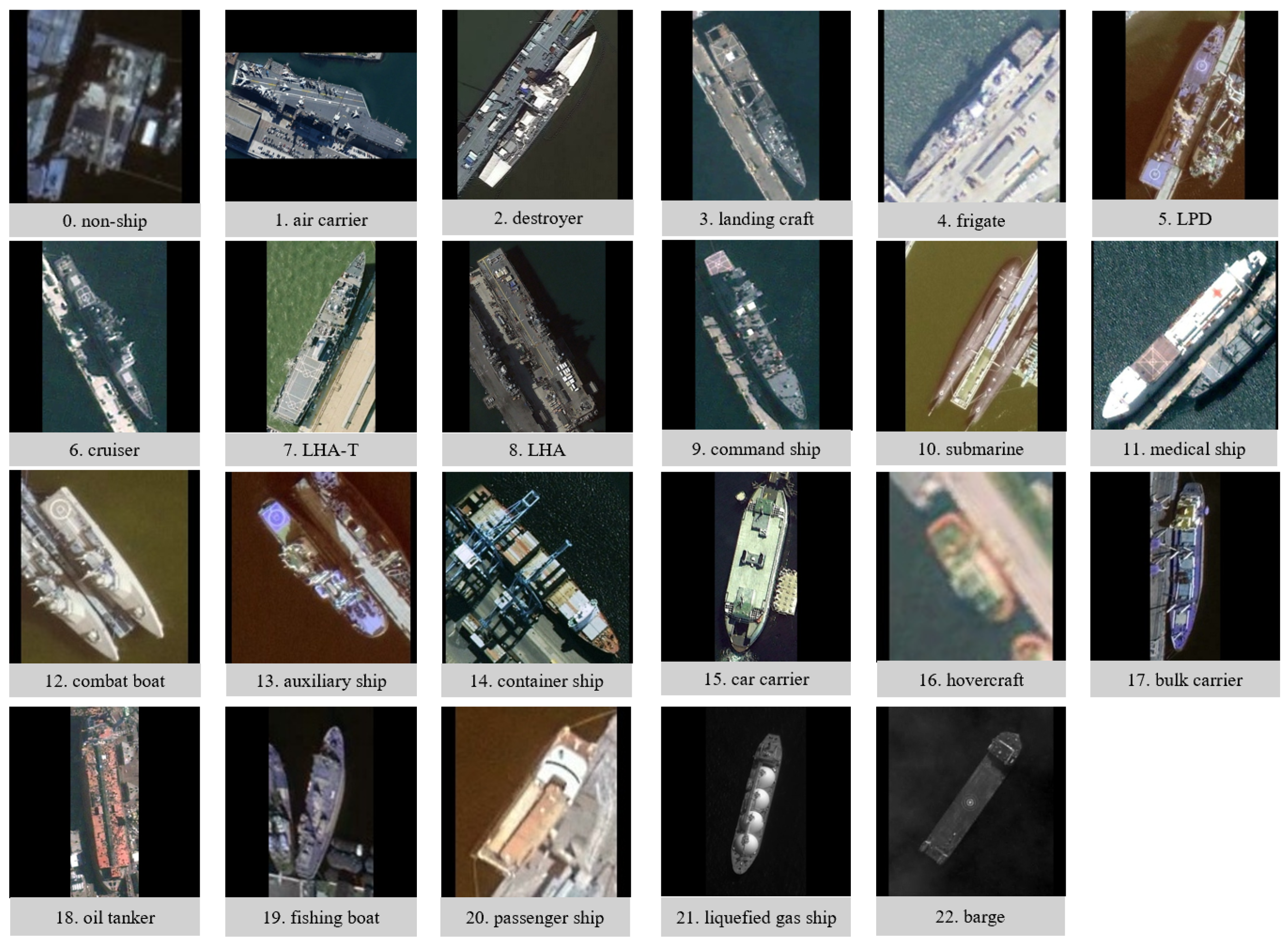

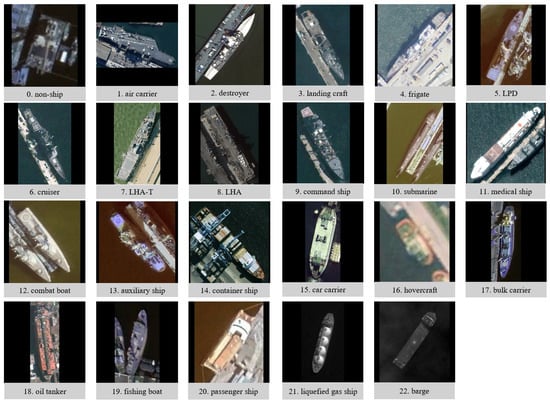

- FGSC-23. The images contained within the FGSC-23 dataset are primarily derived from publicly available Google Earth data and GF-2 satellite panchromatic remote sensing imagery [16]. Certain ship segments originate from the publicly accessible HRSC-2016 ship detection dataset, which features image resolutions ranging from 0.4 to 2 m. The dataset under consideration comprises 4052 segments of foreign ships. The samples are divided into 23 distinct categories: Class 1 denotes non-ship objects that resemble ships, while Classes 2–22 represent ship targets, including container ships, bulk carriers, fishing vessels, and passenger ships. The annotation class numbers range from 0 to 22 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Samples of the FGSC-23 dataset.

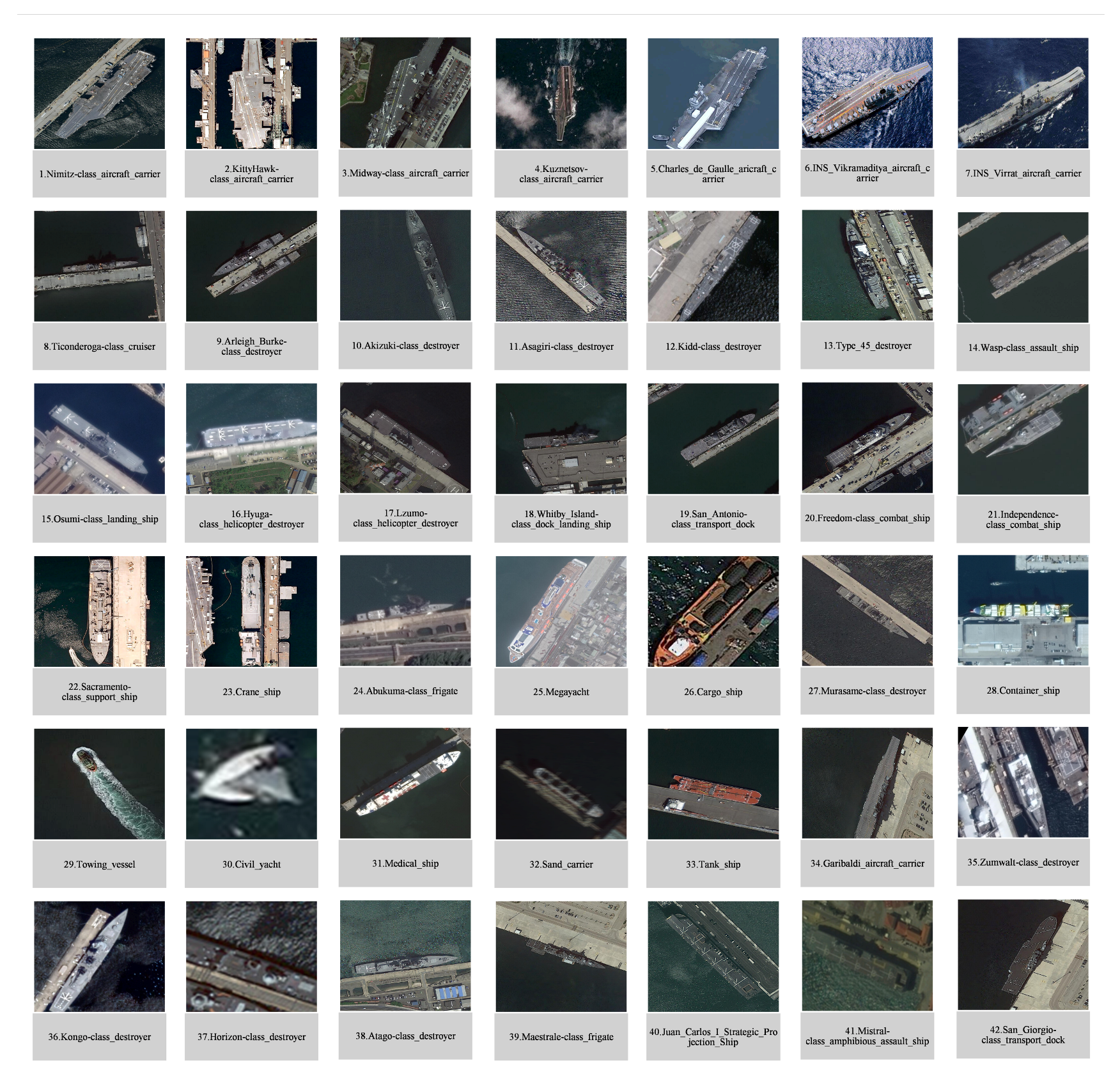

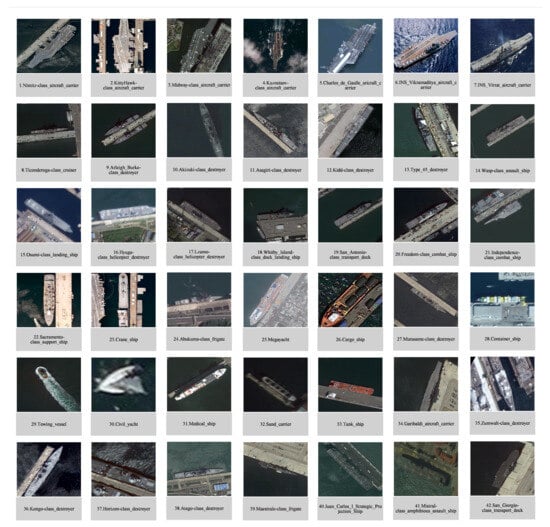

Figure 7. Samples of the FGSC-23 dataset. - FGSCR-42. The imagery for FGSCR-42 comprises segmented images from target detection datasets including DOTA, HRSC2016, and NWPUVHR-10 [38]. The dataset under consideration encompasses 42 categories, the ships of which are classified into 10 broad classes and 42 fine-grained subcategories. The ships in question include the Kitty Hawk-class aircraft carrier, the Nimitz-class destroyer, and superyachts. A comparison of the FGSCR-42 dataset with the FGSC-23 dataset reveals a more sophisticated categorization, extending to particular ship models (Figure 8). Table 1 presents a comparison of the two datasets.

Figure 8. Samples of the FGSCR-42 dataset.

Figure 8. Samples of the FGSCR-42 dataset. Table 1. Comparison between FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 Datasets.

Table 1. Comparison between FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 Datasets.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed MA-Net and ensure fair comparison with existing methods, we employ two widely adopted evaluation metrics in remote sensing image classification: Overall Accuracy (OA) and Average Accuracy (AA). These metrics provide complementary perspectives on model performance, addressing different aspects of classification quality.

Overall Accuracy (OA) is the most intuitive metric, calculated as the ratio of correctly classified samples to the total number of test samples:

where K is the number of classes, denotes the true positives for class i, and is the total number of test samples. While OA provides a general performance measure, it can be biased in imbalanced datasets where certain classes dominate.

Average Accuracy (AA) addresses the class imbalance issue by computing the mean of per-class accuracies:

where represents the total number of samples in class i. AA ensures that each class contributes equally to the final metric, making it particularly valuable for fine-grained classification where class distributions are often uneven.

These two metrics were selected for the following reasons: (1) OA provides a straightforward, holistic view of model performance; and (2) AA ensures fair assessment across all classes regardless of sample distribution, which is crucial for fine-grained tasks where minority classes (rare ship types) are equally important. Together, they form a comprehensive evaluation framework that captures both overall effectiveness and per-class consistency, aligning with the challenges of fine-grained ship classification in remote sensing imagery.

4.2. Implementation Details

In order to ensure the maintenance of scientific rigor and the principles of fairness, all experiments were conducted under identical conditions. All models utilized the PyTorch framework, with the experimental hardware comprising an RTX 4090 GPU featuring 24 GB of VRAM and 90 GB of system memory. The software environment utilized PyTorch 1.9.0, torchvision 0.10.0, and Python 3.8. The learning rate was initialized at , with a batch size of 16. The total number of training epochs was set to 100, employing the AdamW optimizer. The is set to 0.5 and is set to 0.75 in FBDA module.

4.3. Comparisons with Other Methods

We evaluate the proposed MA-Net against several state-of-the-art methods for fine-grained ship classification on the FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets. The comparative results, measured by Overall Accuracy (OA), are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of different methods on FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets.

Our proposed MA-Net achieves the highest classification accuracy of 93.12% on the FGSC-23 dataset, outperforming all existing methods. Specifically, MA-Net surpasses the second-best method Cog-Net by 0.10%, demonstrating the effectiveness of our multi-granularity attention framework. The results indicate that traditional methods like SIM and DCN achieve relatively lower accuracy (86.30% and 90.66%, respectively), while more recent approaches incorporating attention mechanisms and feature enhancement techniques show improved performance. The superior performance of MA-Net can be attributed to the ALFA module, the DMGFF module, and the FBDA method, which together enable the model to capture fine-grained details and integrate multi-scale information effectively.

On the FGSCR-42 dataset, MA-Net achieves the highest accuracy of 98.40%, outperforming all compared methods, including Cog-Net (98.09%), SIM (97.90%), and IELT (97.31%). Notably, MA-Net exhibits a more pronounced advantage on FGSCR-42, surpassing the second-best method by 0.31%, compared to 0.10% on FGSC-23. This indicates that our approach is particularly effective in handling more challenging scenarios with larger numbers of fine-grained categories and more complex backgrounds. The consistent performance improvement across both datasets validates the robustness and generalization capability of our multi-granularity attention framework.

The experimental results demonstrate that MA-Net establishes new state-of-the-art performance on both benchmarks. The performance gains are especially significant on FGSCR-42, which contains more categories and diverse maritime backgrounds. This can be attributed to MA-Net’s ability to: (1) adaptively focus on discriminative local regions through the ALFA module, (2) dynamically fuse multi-granularity features via the DMGFF module, and (3) enhance feature robustness against background interference through the FBDA method. The consistent superiority of MA-Net across both datasets highlights the importance of an integrated approach that simultaneously addresses local feature extraction, multi-scale fusion, and background suppression for fine-grained ship classification in remote sensing imagery.

4.4. Ablation Studies

In this section, comprehensive ablation studies are conducted to evaluate the contributions of the proposed components and hyperparameters in MA-Net. These experiments systematically investigate the individual and combined effects of the ALFA, DMGFF, and FBDA modules, analyze the impact of the parameters and in the FBDA module, and examine the performance with different backbones. Together, these studies demonstrate the effectiveness of our design and the synergistic effects among the proposed modules.

4.4.1. Ablation Study of Three Proposed Components

To thoroughly evaluate the contribution of each proposed component in MA-Net, we conduct comprehensive ablation experiments on both FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets. The baseline model corresponds to using only the ResNet50 backbone without any of our proposed modules. The experimental results, reported in terms of Overall Accuracy (OA) and Average Accuracy (AA), are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ablation study results of the MA-Net model on FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets. Results are reported in terms of Overall Accuracy (OA, %) and Average Accuracy (AA, %).

As shown in Table 3, the baseline model achieves OA/AA scores of 89.02%/86.50% on FGSC-23 and 92.26%/91.45% on FGSCR-42. Notably, when the ALFA module is individually incorporated (applied to the final feature map of the baseline), it yields substantial improvements: OA/AA increases by +3.01/+3.80 percentage points on FGSC-23 and +5.24/+5.65 points on FGSCR-42. This significant gain demonstrates that ALFA’s adaptive local feature attention mechanism effectively enhances the model’s capacity to capture fine-grained, discriminative details, which are crucial for distinguishing highly similar ship subcategories. The DMGFF module, when added alone, also improves upon the baseline but shows more moderate gains (+2.35/+3.10 on FGSC-23 and +3.18/+3.55 on FGSCR-42). This suggests that while multi-granularity feature fusion is beneficial, its full potential is better realized when combined with enriched local features provided by ALFA. Notably, we do not include an isolated experiment for the FBDA method because it is intrinsically designed to operate on the attention maps generated during the forward pass of our model. Its implementation relies on the intermediate feature representations produced by modules like ALFA and DMGFF, making a standalone ablation without these components infeasible.

The combination of ALFA and DMGFF yields OA/AA of 92.60%/91.20% on FGSC-23 and 98.18%/97.85% on FGSCR-42, outperforming either module alone. This synergy indicates that the local discriminative features extracted by ALFA and the adaptive multi-scale fusion performed by DMGFF complement each other effectively. The addition of the FBDA method to this combination produces the best overall results, with OA/AA reaching 93.12%/92.38% on FGSC-23 and 98.40%/98.15% on FGSCR-42. The consistent improvement across both OA and AA, especially the notable increase in AA (which is sensitive to per-class performance), confirms that FBDA successfully enhances feature robustness and mitigates background interference, leading to more balanced and reliable classification.

The ablation study validates the effectiveness and complementary nature of the three proposed components. ALFA provides a strong foundation by capturing fine-grained local features; DMGFF builds upon this by dynamically integrating multi-granularity information; and FBDA further refines the feature representation by suppressing background noise. The progressive performance improvement from the baseline to the full model underscores the importance of addressing the intertwined challenges of fine-grained ship classification through a holistic, multi-component design.

4.4.2. Ablation Study of Different in the FBDA Module

To systematically evaluate the influence of the threshold parameter in the Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) module, we conduct a comprehensive ablation study examining both fixed and random thresholding strategies. The threshold controls which regions of the attention maps are preserved (above threshold) or suppressed (below threshold) during data augmentation, directly affecting the balance between foreground preservation and background suppression. This analysis quantifies how different parameter settings impact classification performance, background suppression effectiveness, and model generalization capability across both datasets.

We evaluate the two thresholding strategies defined in Equation (21). For the fixed threshold approach, we set with values of 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, and 0.7. For the random threshold approach, we set with ranges [0.3, 0.5], [0.4, 0.6], and [0.5, 0.7]. All experiments maintain .

The experimental results on both FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets are summarized in Table 4. The fixed threshold with achieves the highest performance on both datasets, attaining state-of-the-art accuracies of 93.12% on FGSC-23 and 98.40% on FGSCR-42. This optimal value represents a balanced approach where approximately 50% of the attention map (based on relative intensity) is preserved, effectively suppressing background noise while maintaining sufficient discriminative foreground features for fine-grained classification.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different parameter settings in the FBDA module on FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets. Results are reported in terms of Overall Accuracy (OA, %).

Lower threshold values () preserve excessive background regions, diminishing the FBDA module’s effectiveness in background suppression and leading to performance degradation (92.45% on FGSC-23). Conversely, higher thresholds () overly suppress the attention maps, potentially removing important discriminative features along with background noise, resulting in reduced accuracy (92.31% on FGSC-23). This demonstrates the critical trade-off controlled by : lower values preserve more features but retain background noise, while higher values aggressively suppress noise but risk removing discriminative details.

The random thresholding strategy with range achieves competitive performance (93.06% on FGSC-23, 98.36% on FGSCR-42), demonstrating enhanced generalization capability compared to fixed thresholds. This approach introduces beneficial variability during training, forcing the model to adapt to different levels of feature preservation and improving robustness against varying attention map characteristics. The range [0.4, 0.6] provides the optimal balance, while narrower or shifted ranges ([0.3, 0.5] and [0.5, 0.7]) yield slightly reduced performance.

This ablation study quantitatively validates the importance of proper threshold selection in the FBDA module. The optimal setting ( for fixed threshold or [0.4, 0.6] for random threshold) achieves an effective balance between background suppression and feature preservation, contributing significantly to MA-Net’s state-of-the-art performance.

4.4.3. Ablation Study of Different in the FBDA Module

To investigate the influence of the balancing parameter in our Feature-Based Data Augmentation (FBDA) module, we conduct an ablation study with varying values of on both the FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets. The parameter controls the relative weighting between the original image features and the augmented (masked) features during the final prediction and loss computation, as defined in Equations (27) and (28). The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

OA (%) with different values in the FBDA module.

The results reveal a clear trend: the model achieves optimal performance when , yielding the highest accuracy of 93.12% and 98.40% on FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42, respectively. This indicates that a moderate emphasis on the original features, combined with a controlled contribution from the augmented features, provides the most beneficial regularization effect.

When , the model degenerates to using only the original features, effectively disabling the FBDA module. Although performance remains strong, it is slightly lower than the best configuration, confirming that feature-level augmentation contributes positively to generalization. Conversely, when is reduced to 0.25, performance declines noticeably. This suggests that over-relying on the augmented features—which are derived from partially masked regions—may dilute the discriminative information present in the original features, especially for fine-grained details critical in ship classification.

The superior results with demonstrate that the FBDA module works best when it acts as a regularizing complement rather than a dominant source of features. This balance allows the model to retain robust original representations while still benefiting from the variability and noise robustness introduced by the masked features. The small performance drop at further supports the notion that an equal weighting may not optimally trade-off between information preservation and augmentation. In practice, can be tuned as a hyperparameter to adapt to different datasets or tasks, though our experiments suggest a value around 0.75 is generally effective for fine-grained classification of ship targets.

4.4.4. Ablation Study of Different Convolutional Backbones

To investigate the impact of the feature extraction capability of the convolutional backbone on the performance of MA-Net, we conduct ablation experiments using three widely adopted architectures: VGG16, ResNet18, and ResNet50. The comparative results on both FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets, in terms of Overall Accuracy (OA) and Average Accuracy (AA), are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Performance of MA-Net with different convolutional backbones on FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets. Results are reported in terms of Overall Accuracy (OA, %) and Average Accuracy (AA, %).

As shown in Table 6, the choice of backbone significantly influences the classification performance. Among the three backbones, ResNet50 consistently achieves the highest scores across both datasets and both evaluation metrics, establishing itself as the most effective feature extractor for our framework. Specifically, with ResNet50, MA-Net attains OA/AA of 93.12%/92.38% on FGSC-23 and 98.40%/98.15% on FGSCR-42. This superior performance can be attributed to ResNet50’s deeper architecture and the powerful residual learning mechanism, which facilitate the extraction of richer hierarchical and discriminative features essential for fine-grained recognition.

Comparing the results across different backbones, a clear performance hierarchy is observed: ResNet50 > ResNet18 > VGG16. This trend holds for both OA and AA on each dataset. The performance gain from VGG16 to ResNet18 is substantial (e.g., an increase of 2.25% in OA on FGSC-23), demonstrating the advantage of residual connections in mitigating gradient vanishing and enabling effective training of deeper networks. The further improvement from ResNet18 to ResNet50, though smaller in absolute terms, confirms that increased depth and capacity continue to benefit the challenging task of fine-grained ship classification.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that on the more challenging FGSCR-42 dataset, which contains 42 fine-grained categories, all backbones achieve relatively higher OA values compared to FGSC-23. This might be attributed to the potentially more balanced data distribution and the distinct inter-class characteristics in FGSCR-42, as indicated by the smaller gap between OA and AA values across all backbones. Nevertheless, ResNet50 still delivers the most robust and balanced performance, with the highest AA scores, indicating its effectiveness in handling all categories fairly, including potential minority classes.

In conclusion, the ablation study validates that a powerful and deep convolutional backbone is crucial for the proposed MA-Net. The superior and consistent results obtained with ResNet50 justify its selection as the default backbone for our model in all other experiments.

4.5. Visualization Analysis

To elucidate the internal mechanism and the representation of features of MA-Net, we perform a dual-perspective qualitative analysis: visualization of attention through Grad-CAM and visualization of feature embedding using t-SNE.

4.5.1. Attention Visualization with Grad-CAM

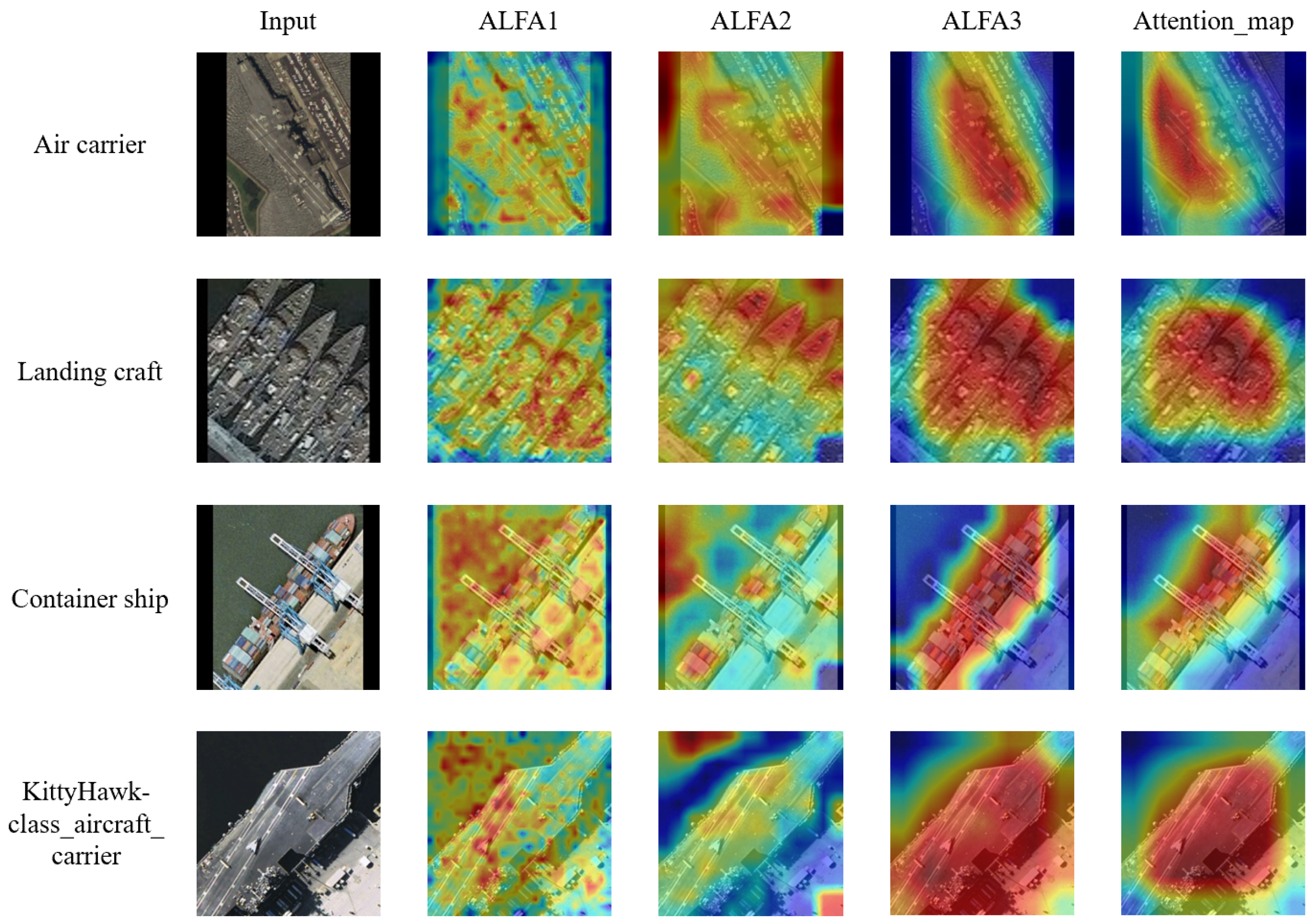

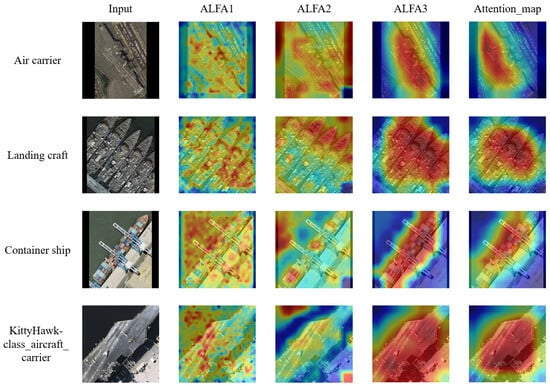

To gain deeper insights into the proposed MA-Net, we employ visualization techniques, including Grad-CAM and feature activation maps, to analyze the model’s focus across different stages. This analysis specifically targets the outputs of our two core components: the attention maps generated by the multi-scale ALFA modules and the final fused attention map produced by the DMGFF module.

The visualization results in Figure 9 elucidate the hierarchical and integrative attention mechanism of the proposed MA-Net. The multi-scale ALFA modules generate attention maps that operate at distinct feature resolutions, embodying a coherent progression from local saliency to global semantics.ALFA1 functions on the highest-resolution feature map (e.g., ), producing activations that pinpoint fine-grained local details. As shown in the second column, its focus is granular, highlighting textural patterns, sharp edges, and small structural elements on the ship’s hull or superstructure. This level of detail provides the foundational cues for distinguishing subtle inter-class variations. ALFA2 operating on a medium-resolution feature map (e.g., ), shifts attention to mid-level discriminative parts. Its activation maps, shown in the third column, cover larger contiguous regions corresponding to functional components of the ship, such as distinct sections of the deck, the bridge structure or cargo handling equipment. This represents an aggregation of local features into semantically meaningful parts. ALFA3 works on the coarsest feature map (e.g., ), capturing holistic target-level semantics. Its activations, depicted in the fourth column, encompass the entire object or its major subsections, providing contextual understanding and shape priors. This global view ensures that the model maintains structural coherence and suppresses attention to irrelevant background regions.

Figure 9.

Differences in the activation maps of different module outputs. The first three rows of images are from the FGSC-23 dataset, and the last row is from the FGSCR-42 dataset. The model’s focus across stages is analyzed using Grad-CAM and feature activation visualization. ALFA1, ALFA2, and ALFA3 represent local attention outputs at three granularities, while attention map is the multi-granularity fused output from the DMGFF module. From ALFA1 to ALFA3, there is a shift in attention from fine-grained to coarse-grained features, indicating that the model transitions from focusing on local details to emphasizing overall semantics. Subsequently, the DMGFF module fuses these multi-granularity features to obtain combined local and global attention regions, making the discriminative parts of different categories more prominent.

The final attention map, generated by the DMGFF module, synthesizes these multi-granularity cues through dynamic feature fusion. As evidenced in the last column, the fused map is neither a simple superposition nor a dominant selection from a single scale. Instead, it achieves a context-aware integration: it preserves precise localization from high-resolution cues (ALFA1) while being guided by the semantic significance provided by coarser scales (ALFA2, ALFA3). Consequently, the most discriminative regions for the target category—such as the distinctive flight deck and island of an air carrier, the ramp of a landing craft, or the stacked container arrays on a container ship—are highlighted with remarkable focus and accuracy. This demonstrates the DMGFF module’s efficacy in consolidating a spatially coherent and semantically rich attention profile, which is critical for robust fine-grained classification where both local distinctive features and their global spatial configuration are paramount.

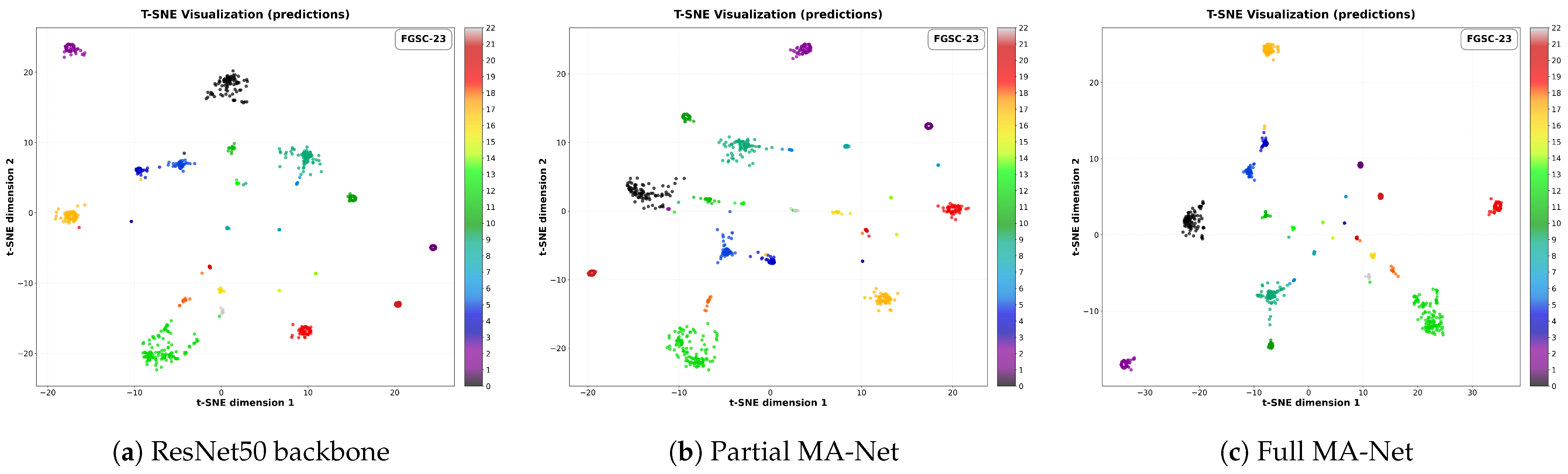

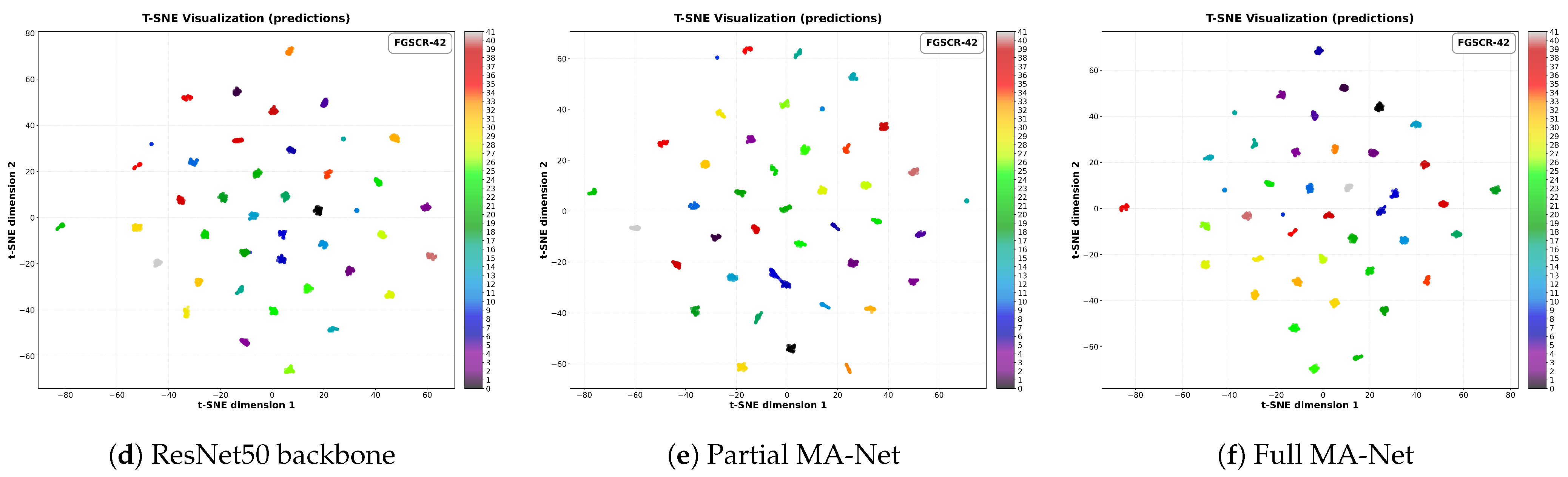

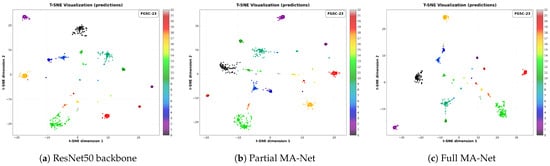

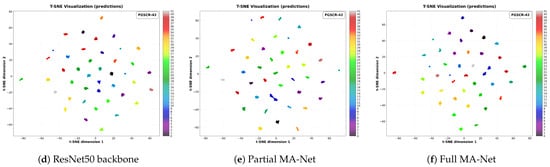

4.5.2. Feature Distribution Visualization with t-SNE

To quantitatively assess the discriminative power of the learned feature representations, we visualize the high-dimensional feature embeddings from the layer preceding the final classifier using t-SNE. This non-linear dimensionality reduction technique allows us to project the final feature vectors of test samples from the FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 datasets onto a two-dimensional plane, thereby intuitively revealing the inter-class separability and intra-class compactness.

Figure 10c,f presents the t-SNE visualization for the entire MA-Net model. The result demonstrates highly discriminative feature organization: samples belonging to different fine-grained ship categories form distinct, well-separated clusters with clear decision boundaries. This pronounced separation is a direct visual correlate of the high classification accuracy of the model. Notably, even sub-classes with subtle visual differences are effectively pulled apart in the embedding space.

Figure 10.

T-SNE visualization of feature distributions on the FGSC-23 (first row) and FGSCR-42 (second row) datasets. (a,d) ResNet50 backbone, (b,e) partially ablated MA-Net, and (c,f) full MA-Net model. The full MA-Net exhibits clearer inter-class separation and tighter intra-class clustering on both datasets.

This superior feature distribution can be attributed to the synergistic effect of our proposed modules. The ALFA module enriches the feature set with discriminative multi-granularity details, providing more distinctive cues for separation. The DMGFF module dynamically fuses these cues, creating a more robust and holistic representation for each class that is less susceptible to intra-class variance. Furthermore, the FBDA method enhances generalization by simulating feature-level variations, which likely contributes to tighter within-class clusters. For comparison, Figure 10a,d and b,e show the t-SNE plots for the ResNet50 baseline and a partially ablated version of MA-Net, respectively. The baseline exhibits significant overlap and diffuse structures for several categories, while the progressive integration of our modules leads to successively more compact and isolated clusters. This visualization conclusively validates that MA-Net learns a feature-embedding space where semantic similarity is accurately encoded as spatial proximity, which is the fundamental reason for its state-of-the-art performance in fine-grained ship classification.

5. Discussion

The experimental results establish MA-Net as a state-of-the-art method for fine-grained ship classification in remote sensing imagery. Such performance is attributable to the framework’s specialized architecture, which systematically addresses the domain-specific challenges inherent in remote sensing. The significant improvement in the more challenging FGSCR-42 dataset confirms our underlying thesis: a model that dynamically focuses on structurally salient regions (via ALFA), intelligently combines features from different semantic levels (via DMGFF), and actively reduces distraction from irrelevant backgrounds (via FBDA) is better equipped to discern subtle inter-class differences.

Our approach differentiates itself from mainstream fine-grained classification methods, which are often developed for and evaluated on natural objects like birds or cars. While those objects exhibit flexible poses, ships possess a more constrained and consistent physical layout. MA-Net does not enforce a rigid, predefined structural model. Instead, ALFA introduces an inductive bias toward learning spatially organized features through its adaptive, overlapping patch mechanism and local self-attention. This allows the network to discover and leverage the consistent spatial configurations of ship components (e.g., superstructure placement) from the data itself, which is a distinguishing factor from methods designed for amorphous or highly deformable objects. DMGFF further supports this by ensuring that both fine-grained part-level cues and coarse-grained shape-level information are preserved and contextually fused, a process critical for recognizing man-made artifacts where both detail and overall form matter.

This work has several limitations that open avenues for future research. The performance gains of MA-Net come with an increase in parameter count and computational demand compared to a standard backbone network. Future work could explore network pruning or more efficient attention formulations to improve inference speed for potential real-time applications. Furthermore, the current evaluation is conducted on optical satellite imagery. Validating the framework’s efficacy on other maritime remote sensing data sources, such as Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery—where ship appearances are governed by different scattering mechanisms—would be a valuable test of its generalizability.

In summary, MA-Net presents a potent solution tailored to the nuances of fine-grained ship classification. Its core innovation lies not in imposing a strict structural prior, but in providing a flexible architectural substrate (ALFA, DMGFF) that empowers the model to learn and exploit the inherent structural regularity of its targets. The principles of adaptive multi-granularity analysis and feature-space augmentation are likely transferable to other remote sensing fine-grained tasks involving structured objects.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose MA-Net, a Multi-Granularity Attention Network for fine-grained classification of ship targets in remote sensing images. MA-Net addresses key challenges in this domain—limited local feature expression, insufficient multi-granularity fusion, and background interference—through three novel components: The ALFA module captures detailed local features via complexity-aware overlapping patch extraction and local self-attention. The DMGFF module adaptively integrates multi-level features with learnable fusion weights and channel attention. The FBDA method enhances feature discriminability by generating attention-guided masked images during training.

Extensive experiments on FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 demonstrate that MA-Net achieves state-of-the-art or highly competitive performance. Ablation studies confirm the complementary contributions of each component, with the full model improving significantly over the baseline. The proposed framework provides a robust and adaptable solution for fine-grained ship classification, with potential applications in marine surveillance, traffic monitoring, and defense systems. Future research will focus on optimizing computational efficiency and extending MA-Net to other fine-grained classification of ship targets in remote sensing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Q., B.N. and F.W.; methodology, J.Q.; software, J.Q.; validation, P.L.; formal analysis, X.X.; resources, G.Z., B.N. and Y.H.; data curation, J.Q. and Q.W.; writing—original draft, J.Q.; writing—review and editing, B.N. and Y.H.; visualization, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The public datasets FGSC-23 and FGSCR-42 are openly available, reference number [16,38].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Branson, S.; Perona, P.; Belongie, S. Strong supervision from weak annotation: Interactive training of deformable part models. In 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göering, C.; Rodner, E.; Freytag, A.; Denzler, J. Nonparametric Part Transfer for Fine-Grained Recognition. In 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 2489–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, S.; Horn, G.V.; Belongie, S.; Perona, P. Bird Species Categorization Using Pose Normalized Deep Convolutional Nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Fu, J.; Zha, Z.J.; Luo, J. Looking for the Devil in the Details: Learning Trilinear Attention Sampling Network for Fine-Grained Image Recognition. In 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 5007–5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wen, S.; Xie, J.; Chang, D.; Si, Z.; Wu, M.; Ling, H. AP-CNN: Weakly Supervised Attention Pyramid Convolutional Neural Network for Fine-Grained Visual Classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2826–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; He, X.; Zhao, J. Object-Part Attention Model for Fine-Grained Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, B.; Yang, M.; Wu, Z.; Yao, Y.; Wei, Z. Two-stage fine-grained image classification model based on multi-granularity feature fusion. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 146, 110042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, B.; Luo, B.; Tang, J. Multi-Granularity Part Sampling Attention for Fine-Grained Visual Classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 4529–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazilov, S.; Yusupov, O.; Khandamov, Y.; Eshonqulov, E.; Khamidov, J.; Abdieva, K. Remote Sensing Scene Classification via Multi-Feature Fusion Based on Discriminative Multiple Canonical Correlation Analysis. AI 2026, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, K.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Contrastive Learning for Fine-Grained Ship Classification in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4707916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. Contrastive Learning with Part Assignment for Fine-grained Ship Image Recognition. In 2023 International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Machine Vision and Intelligent Algorithms (PRMVIA); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Li, R.; Hu, Q.; Niu, C.; Liu, W.; Lu, W. Contrastive Learning Network Based on Causal Attention for Fine-Grained Ship Classification in Remote Sensing Scenarios. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Fine-Grained Classification of Optical Remote Sensing Ship Images Based on Deep Convolution Neural Network. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Z. Multi-Feature Fusion with Convolutional Neural Network for Ship Classification in Optical Images. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q. Fine-Grained Ship Classification by Combining CNN and Swin Transformer. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.; Yao, L.; Xiong, W.; Fu, C. A New Benchmark and an Attribute-Guided Multilevel Feature Representation Network for Fine-Grained Ship Classification in Optical Remote Sensing Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 1271–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Li, W.; Lang, C.; Zhang, P.; Yao, Y.; Han, J. Learning Discriminative Representation for Fine-Grained Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 8197–8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Bian, C.; Li, L. Adap-EMD: Adaptive EMD for Aircraft Fine-Grained Classification in Remote Sensing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 6509005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yang, X.; Pu, T.; Peng, Z. Fine-Grained Recognition for Oriented Ship Against Complex Scenes in Optical Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, C. Transformer and CNN Hybrid Deep Neural Network for Semantic Segmentation of Very-High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4408820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Xiong, Z.; Yao, L.; Cui, Y. Cog-Net: A Cognitive Network for Fine-Grained Ship Classification and Retrieval in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5608217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Yao, J.; Yokoya, N.; Li, H.; Ghamisi, P.; Jia, X.; et al. SpectralGPT: Spectral Remote Sensing Foundation Model. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5227–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Donahue, J.; Girshick, R.; Darrell, T. Part-based R-CNNs for Fine-grained Category Detection. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1407.3867. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, K.J.; Mallya, A.; Singh, S.; Hoiem, D. Part Localization using Multi-Proposal Consensus for Fine-Grained Categorization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1507.06332. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Xu, Z.; Tao, D.; Zhang, Y. Part-Stacked CNN for Fine-Grained Visual Categorization. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Shen, X.; Lu, C.; Jia, J. Deep LAC: Deep localization, alignment and classification for fine-grained recognition. In 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.S.; Xie, C.W.; Wu, J. Mask-CNN: Localizing Parts and Selecting Descriptors for Fine-Grained Image Recognition. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.06878. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, T.; Yin, J.; See, S.; Liu, J. Learning Gabor Texture Features for Fine-Grained Recognition. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wu, X.; Chu, A.; Huang, L.; Wei, Z. SwinFG: A fine-grained recognition scheme based on swin transformer. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 244, 123021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Tian, Y. Part-Guided Relational Transformers for Fine-Grained Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 9470–9481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Gao, Y. Feature Fusion Vision Transformer for Fine-Grained Visual Categorization. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2107.02341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, J.N.; Liu, S.; Kortylewski, A.; Yang, C.; Bai, Y.; Wang, C. TransFG: A Transformer Architecture for Fine-grained Recognition. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.07976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiang, B.; Luo, B. Fine-Grained Visual Classification via Internal Ensemble Learning Transformer. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 9015–9028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Chen, G.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. Counterfactual Attention Learning for Fine-Grained Visual Categorization and Re-identification. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.08728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; McCool, C.; Sanderson, C.; Corke, P. Subset feature learning for fine-grained category classification. In 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Bewley, A.; McCool, C.; Corke, P.; Upcroft, B.; Sanderson, C. Fine-grained classification via mixture of deep convolutional neural networks. In 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, G. Learning Fine-grained Features via a CNN Tree for Large-scale Classification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1511.04534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, H. A Public Dataset for Fine-Grained Ship Classification in Optical Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Leng, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, B.; Ji, K.; Kuang, G. Ship Recognition for Complex SAR Images via Dual-Branch Transformer Fusion Network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4009905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Tong, T.; Yao, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; He, Y.; Lu, H. Feature Balance for Fine-Grained Object Classification in Aerial Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5620413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; He, X.; Peng, Y. SIM-Trans: Structure Information Modeling Transformer for Fine-grained Visual Categorization. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.14607. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, W.; Mei, T. Destruction and Construction Learning for Fine-Grained Image Recognition. In 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 5152–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Xiong, Z.; Cui, Y. An Explainable Attention Network for Fine-Grained Ship Classification Using Remote-Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5620314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.