Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A high-fidelity synthetic data generation framework effectively bridges the Sim2Real gap by integrating oblique photogrammetry with diversified rendering strategies.

- For the detection of truncated or occluded vehicles, detectors trained on high-fidelity synthetic data achieve significant performance improvements.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Offers a cost-effective and scalable data acquisition approach for UAV-based vehicle detection, alleviating the bottleneck of expensive data collection and manual annotation.

- Generates rare samples that are difficult to capture in real-world scenarios, serving as a supplement to real-world UAV data.

Abstract

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) imagery has emerged as a critical data source in remote sensing, playing an important role in vehicle detection for intelligent traffic management and urban monitoring. Deep learning–based detectors rely heavily on large-scale, high-quality annotated datasets, however, collecting and labeling real-world UAV data are both costly and time-consuming. Owing to its controllability and scalability, synthetic data has become an effective supplement to address the scarcity of real data. Nevertheless, the significant domain gap between synthetic data and real data often leads to substantial performance degradation during real-world deployment. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a high-fidelity synthetic data generation framework designed to reduce the Sim2Real gap. First, UAV oblique photogrammetry is utilized to reconstruct real-world 3D model, ensuring geometric and textural authenticity; second, diversified rendering strategies that simulate real-world illumination and weather variations are adopted to cover a wide range of environmental conditions; finally, an automated ground-truth generation algorithm based on semantic masks is developed to achieve pixel-level precision and cost-efficient annotation. Based on this framework, we construct a synthetic dataset named UAV-SynthScene. Experimental results show that multiple mainstream detectors trained on UAV-SynthScene achieve competitive performance when evaluated on real data, while significantly enhancing robustness in long-tail distributions and improving generalization on real datasets.

1. Introduction

UAVs have become an important platform for remote sensing, supporting applications such as urban monitoring, intelligent transportation, infrastructure inspection, and environmental surveillance [1,2]. Benefiting from high spatial resolution, flexible acquisition modes, and rapid response capabilities, UAV imagery effectively captures small-scale targets, making it well-suited for vehicle detection tasks in complex urban environments.

Deep learning-based detectors rely heavily on large-scale and high-quality annotated datasets [3,4]. However, collecting and labeling real-world UAV data is prohibitively costly and time-consuming. Furthermore, constrained by flight regulations, weather conditions, and operational safety, real data collection often fails to capture rare corner cases, such as truncated objects caused by variations in altitude and viewing angles, or hazardous scenarios [5,6]. These limitations hinder the acquisition of sufficiently diverse and balanced datasets for training robust vehicle detectors, especially when precise annotations are required.

Synthetic data generation provides a promising solution to address these challenges. This technology enables full control over illumination, sensor parameters, and scene composition, while providing complete and automatically generated annotations. Moreover, synthetic datasets constructed through this approach can reproduce rare, hazardous, or operationally constrained scenarios that are difficult to capture in real-world UAV missions. Consequently, synthetic data serves as an effective supplement to real data, compensating for its limitations in coverage and scene diversity.

The practical value of synthetic data depends on its ability to be effectively deployed in real-world environments. However, many existing synthetic UAV datasets, constructed using 3D engines such as Carla [7] and AirSim [8], typically rely on simplified 3D assets or generic urban templates [9]. These environments do not accurately reflect real-world geospatial structures, terrain geometry, or UAV-specific imaging characteristics. As a result, the Sim2Real domain gap remains substantial, causing models trained on such data to degrade sharply in real-world deployment [10,11,12]. Notably, most existing approaches still require mixing synthetic data with real data or fine-tuning on a real dataset to reach a satisfactory performance baseline [13,14].

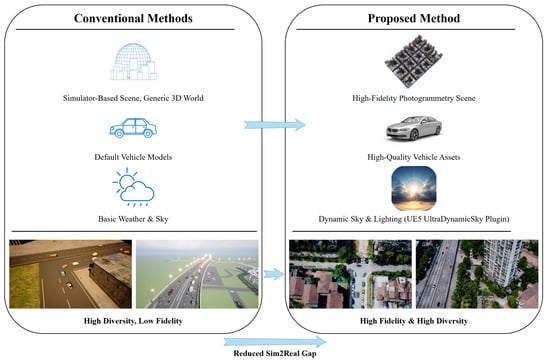

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a synthetic data generation framework that combines scene fidelity with diversified rendering (Figure 1). First, oblique photogrammetry is employed to reconstruct real-world 3D models from UAV imagery, or existing 3D tiles (e.g., .b3dm format) are directly integrated, ensuring the authenticity of geometric structures and texture details without extensive manual modeling. Second, diversified rendering strategies are adopted to simulate variations in illumination, weather conditions, and UAV viewpoints, enhancing model adaptability to complex environments. Finally, an automated annotation algorithm based on semantic masks is introduced to generate pixel-level accurate labels, significantly reducing annotation costs. Based on this framework, we construct a synthetic dataset named UAV-SynthScene (Figure 2). It further supports the controllable synthesis of long-tail and underrepresented object instances to mitigate sampling imbalance, providing an efficient and scalable supplement to labor-intensive real data acquisition.

Figure 1.

Comparison between conventional Sim2Real strategies and the proposed high-fidelity synthetic data generation method for UAV-based vehicle detection. Our approach integrates oblique photogrammetry with diversified rendering to bridge the Sim2Real gap.

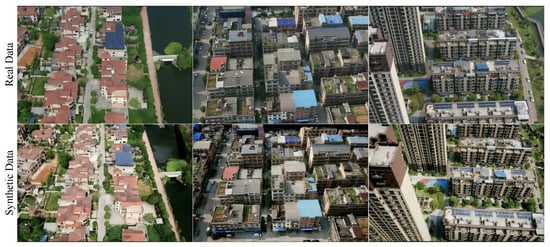

Figure 2.

Qualitative comparison demonstrating the high fidelity of our synthetic data. The top row presents sample images from the real dataset. The bottom row showcases corresponding images generated by our framework. Each column pairs a real image with its synthetic counterpart, rendered from a similar viewpoint to highlight the visual consistency.

Comprehensive experiments conducted on real-world UAV datasets using six mainstream detectors demonstrate that models trained solely on UAV-SynthScene achieve performance comparable to those trained on real data (Figure 3). In particular, the proposed synthetic data significantly improves model robustness under long-tail data distributions and exhibits a certain degree of cross-domain generalization capability across multiple real-world UAV datasets.

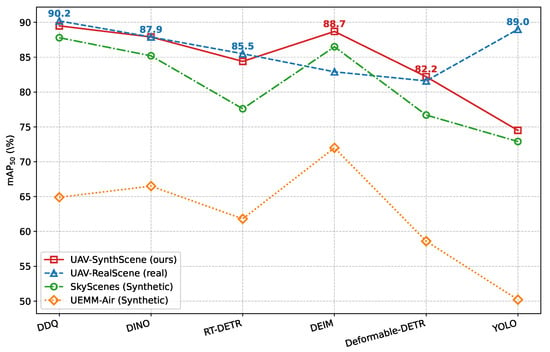

Figure 3.

Performance comparison of detectors trained on different datasets. All models were evaluated on the real-world test set using the metric. The x-axis lists detectors, sorted in descending order of performance achieved with the real training data. The proposed synthetic dataset consistently achieves performance comparable to the real dataset, and significantly outperforms other synthetic data generation methods (SkyScenes and UEMM-Air) across all tested architectures.

The main contributions are as follows:

- 1.

- A data generation framework: We propose a high-fidelity synthetic data generation framework designed to minimize the Sim2Real gap at the source. This framework enhances the practical utility of synthetic data, establishing it as a powerful supplement to real-world UAV imagery.

- 2.

- A High-Quality Synthetic Dataset: Based on the proposed framework, we construct UAV-SynthScene, a high-quality and realistic synthetic dataset specifically designed for UAV-based vehicle detection.

- 3.

- Comprehensive Experimental Validation: Extensive experiments are conducted using six mainstream detectors on multiple real-world UAV datasets to validate the effectiveness of the generated synthetic data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Synthetic Data in Remote Sensing

The scalability of deep learning models for Earth observation is often limited by the high cost and effort required for collecting and annotating real data. This has driven significant research into synthetic data generation. Early methods focused on data augmentation techniques like flipping and color jittering [15], or compositional approaches such as MixUp [16] and Copy-Paste [17]. While useful, these methods are confined to the feature space of the original dataset and cannot generate novel geospatial contexts or object variations.

Generative models, including Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [18], Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [19], and diffusion models [20], represent a more advanced direction, capable of producing photorealistic images. Approaches like SimGAN [21] can even refine rendered images to enhance realism. However, for remote sensing applications, these methods often lack the precise structural and semantic controllability required to simulate specific sensor parameters (e.g., camera intrinsics, viewing angles) or complex, geographically accurate scenes.

The most common paradigm involves using 3D graphics engines, as demonstrated by influential datasets in computer vision like Virtual KITTI [22], SYNTHIA [23], Playing for Data [24], and GTA-V [25]. These platforms allow for precise control over scene elements and automated annotation. This paradigm is typically split into two philosophies: (1) Photorealistic Rendering, which prioritizes visual fidelity by meticulously matching real-world conditions [22], and (2) Domain Randomization (DR), which prioritizes model generalization by introducing large-scale, often non-photorealistic, variations in textures and lighting [26].

Despite their success in ground-level vision, both philosophies face a critical limitation in the remote sensing context: the reliance on generic 3D assets. Such assets lack the geospatial consistency and unique topographical and textural features of real-world locations captured from aerial platforms. This fundamental “structural domain gap” is a primary reason for the performance drop when transferring models to real UAV imagery. Our work addresses this gap by grounding the synthesis in photogrammetry-based digital twins of real environments [27,28,29], thereby ensuring a high degree of geospatial fidelity from the outset.

2.2. Domain Generalization and Data Imbalance in Synthetic Imagery

The discrepancy between simulated and real data, known as the Sim2Real gap, is a central challenge. Beyond improving realism, two main strategies are used to bridge this gap: Domain Adaptation (DA) and further developments in Domain Randomization (DR).

DA methods, such as adversarial learning [30], feature alignment [31], and invariant feature extraction [32,33], aim to align feature distributions between the synthetic (source) and real (target) domains. However, they typically require a substantial amount of unlabeled real data, which can be as difficult to collect in UAV scenarios as labeled data, thus limiting their practicality.

DR-based approaches, in contrast, aim to create a synthetic data distribution so diverse that it encompasses the real-world domain. While standard DR often uses uniform random sampling, more advanced techniques like Active DR employ reinforcement learning to find more effective randomization parameters [34]. Our work builds on this concept of targeted sampling but proposes a more direct strategy: we explicitly define and generate samples for task-critical scenarios (e.g., challenging viewpoints or illumination) to enhance model generalization more efficiently.

A related challenge, particularly prominent in aerial imagery, is data imbalance and long-tail distributions. Flight geometry and framing limitations often lead to an underrepresentation of crucial instances like truncated or boundary objects. While data-level (e.g., resampling [35], hard example mining [36], generative augmentation [37]) and model-level (e.g., loss re-weighting [38], decoupled training [39], robust feature regularization [40,41]) strategies exist, they are post-hoc remedies. Our framework addresses this proactively by leveraging the full controllability of the simulation to generate a balanced distribution of these rare but critical samples.

2.3. Object Detection from UAV Platforms

Object detection from UAVs presents a unique set of challenges compared to ground-based detection, including extreme variations in object scale, high object density, and complex, cluttered backgrounds [42]. While foundational detectors like Faster R-CNN [43] and YOLO [44], and more recent transformer-based architectures like DETR [45] and DINO [46], have continuously advanced the field, their performance is ultimately capped by the quality and diversity of the training data.

Many UAV-specific adaptations have been proposed, focusing on algorithmic improvements such as multi-scale feature fusion [47,48], spectral-spatial context aggregation [49], and dynamic target perception [50]. Furthermore, recent research has expanded UAV perception capabilities to more complex tasks such as cross-modal target tracking [51] and dynamic information interaction [52], highlighting the increasing demand for robust feature representation. Despite these advances, the data bottleneck remains the primary constraint. This motivates our work: to create a scalable source of high-quality, task-oriented synthetic data that not only alleviates the need for manual annotation but is also specifically designed to address the unique challenges of UAV remote sensing, such as viewpoint variability and long-tail distributions of partially occluded targets. While prior works have made substantial progress, few have jointly optimized for geospatial fidelity and diversified rendering in a remote sensing context, which is the core contribution of our proposed framework.

Although existing literature has made substantial progress in synthetic data generation, Sim2Real transfer, and long-tail learning, a core limitation persists: prior efforts, often relying on generic 3D assets, have largely failed to synergistically optimize the geospatial fidelity derived from real-world mapping with the diversified rendering of dynamic factors such as illumination, weather, and sensor viewpoints. Moreover, systematic solutions remain scarce for two challenges inherent to aerial data acquisition: the viewpoint variability introduced by diverse flight altitudes and camera orientations, and the structural imbalance of long-tail targets (e.g., truncated or boundary objects) caused by occlusion and framing limitations. In light of these gaps, the framework proposed in this paper aims to systematically address these challenges. By fusing high-fidelity photogrammetric reconstruction with diversified physical rendering, we provide a more reliable and scalable data foundation for advancing data-driven geospatial AI research.

3. Materials and Methods

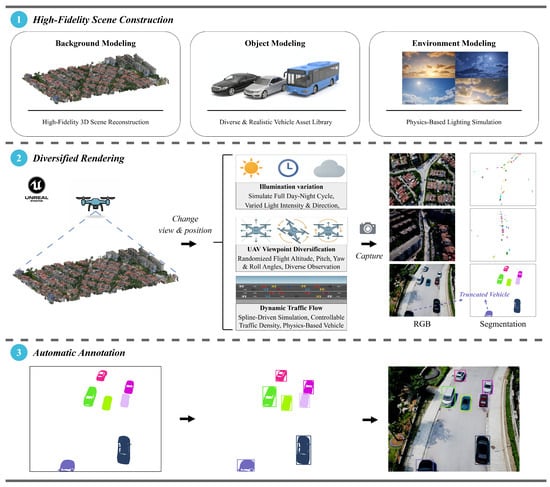

The proposed framework provides a complete workflow for generating high-fidelity, diverse synthetic data for UAV-based object detection, designed to minimize the domain gap with real-world aerial imagery. As illustrated in Figure 4, the overall pipeline consists of three key stages: scene reconstruction, rendering diversification and automatic annotation. Each stage is designed to address a specific limitation of conventional synthetic data, including insufficient realism, restricted variation, high annotation cost, and dataset imbalance, while maintaining full controllability throughout the rendering process.

Figure 4.

Overview of the proposed high-fidelity synthetic data generation framework. The pipeline begins with ① High-Fidelity Scene Construction, where photogrammetry is used to reconstruct realistic 3D environments (e.g., terrain, buildings) from real UAV imagery, which are then populated with a diverse library of vehicle assets. This ensures foundational realism. Next, in the ② Diversified Rendering stage, a wide spectrum of training images is generated by systematically varying dynamic factors such as lighting, weather, and UAV viewpoints, while simulating dynamic traffic flow to enhance model generalization. Finally, the ③ Automated Ground Truth Generation module programmatically generates pixel-perfect ground-truth labels (segmentation masks and bounding boxes) for each rendered image, creating a cost-effective and scalable data pipeline.

Our methodology is implemented within an advanced simulation pipeline built upon Colosseum [53] (the successor to Microsoft AirSim) and Unreal Engine 5.1. First, realistic static environments are reconstructed from real UAV imagery through oblique photogrammetry, which ensures geometrical and textural consistency with real-world urban scenes. Second, dynamic environmental conditions such as lighting, weather, and camera viewpoint are systematically varied using physically based rendering to improve generalization. Third, each rendered image is automatically annotated with precise bounding boxes derived from semantic instance masks generated within the rendering engine. Finally, targeted synthesis of long-tail samples—including truncated, occluded, or boundary vehicles—is performed to mitigate the long-tail distribution commonly observed in UAV datasets.

3.1. High-Fidelity Scene Construction

Background modeling. We employ automated photogrammetry to reconstruct textured 3D meshes from UAV imagery, generating high-fidelity digital twin environments. The reconstructed background preserves the geometry of terrain, roads, and buildings, while retaining intricate texture details and spatial layouts. Compared with generic 3D asset libraries, this approach substantially reduces the stylistic gap between synthetic and real scenes, which helps reduce the domain gap from the source.

Object modeling. A comprehensive vehicle asset library is developed, covering various categories such as sedans, SUVs, trucks, and buses. By leveraging Unreal Engine’s material system, realistic surface properties are assigned to each vehicle, including color, metallicity, roughness, and albedo. This ensures both accurate geometric fidelity and broad coverage of real-world appearance variations, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Examples from the high-quality vehicle asset library, showcasing 15 distinct vehicle models, each available in multiple color configurations. These assets serve as high-fidelity building blocks for the generation of realistic and heterogeneous synthetic traffic scenes.

Environment modeling. We integrate the UltraDynamicSky plugin of Unreal Engine to simulate physically based temporal and weather dynamics. This includes solar elevation, illumination color, shadow intensity, as well as complex weather conditions such as overcast skies, rainfall, and fog. Such modeling provides UAV target detection with spatiotemporal variations that closely resemble those observed in real environments.

3.2. Diversified Rendering

While static scene reconstruction achieves high fidelity, simulation alone cannot fully capture the complexity of real-world phenomena such as illumination, atmospheric scattering, and dynamic camera perspectives. To overcome this limitation, we implement targeted diversification strategies to ensure our synthetic data covers a wide spectrum of complex conditions encountered in real-world operations.

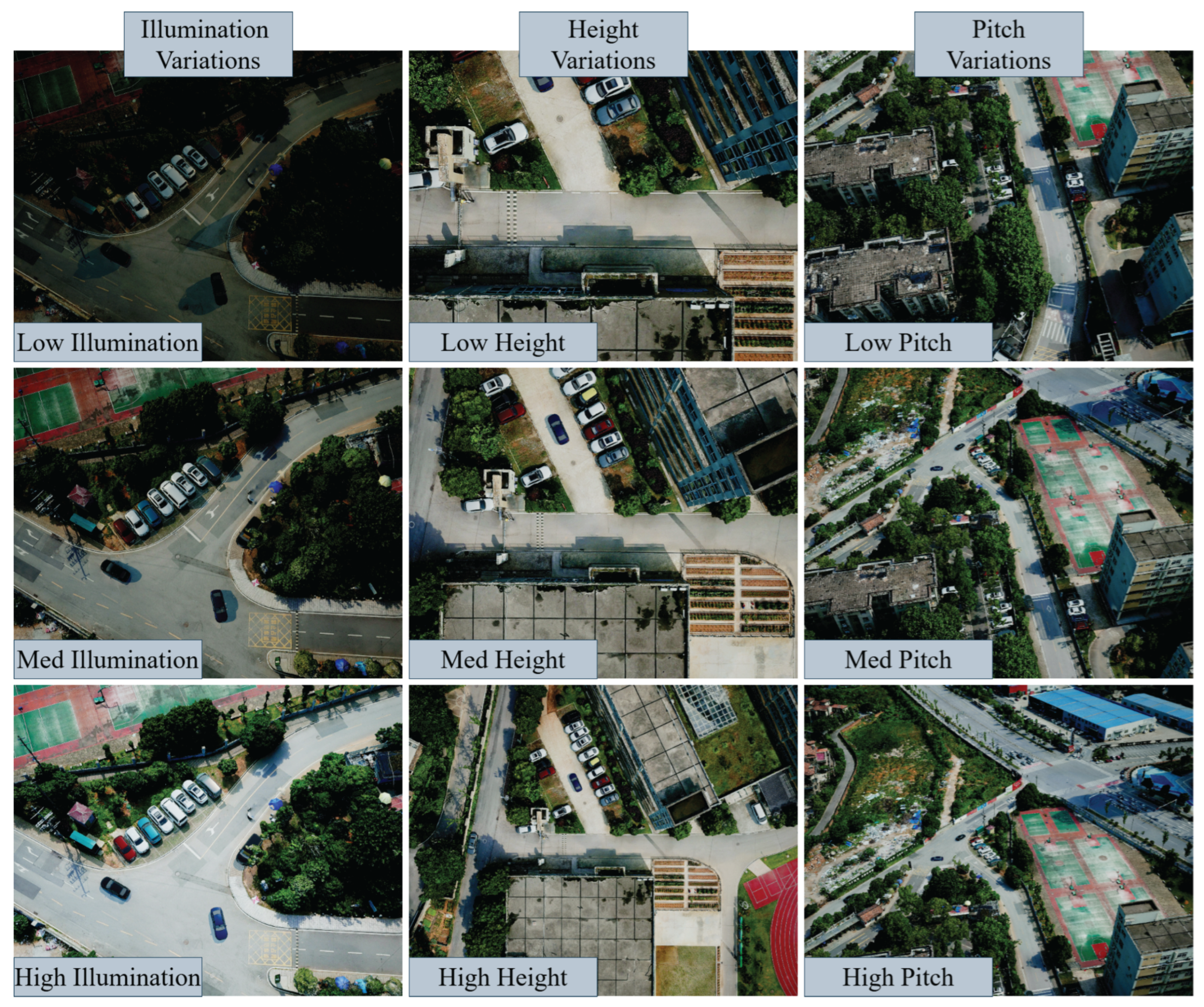

To achieve illumination diversity, we simulate the full diurnal cycle and a variety of weather scenarios (Figure 6) by dynamically adjusting solar elevation, light intensity, and atmospheric conditions. This ensures that the dataset spans a wide range of lighting and meteorological conditions.

Figure 6.

Visualization of the proposed diversified rendering strategy. This controlled diversity enables the synthetic dataset to cover a wide range of environmental and viewpoint conditions encountered in real UAV operations.

To ensure UAV viewpoint diversity, we produce multi-perspective observations by randomizing flight altitude, pitch, yaw, and roll. This enhances the robustness of detectors when deployed in real UAV missions. The camera in Unreal Engine is configured with a focal length of 10 mm, a sensor size of 6.4 mm × 5.12 mm, and a resolution of 1920 × 1536.

For dynamic traffic flow modeling, we employ spline-driven trajectories to simulate traffic flow, producing realistic spatial distributions and relative vehicle motions. In contrast to purely random placement, this method preserves naturalistic traffic patterns while ensuring sufficient diversity.

For long-tail sample generation, we systematically generate truncated samples by controlling camera poses and sampling strategies to position objects at image boundaries. This mechanism significantly mitigates the scarcity of long-tail samples commonly found in real datasets.

3.3. Automated Ground Truth Generation

To circumvent the high cost of manual labeling, we generate instance-level semantic segmentation maps in parallel with RGB images during rendering. Each vehicle is encoded with a unique RGB value, enabling automated extraction of object masks and bounding boxes. The entire procedure is detailed in Algorithm 1. Compared with manual annotation, this approach offers three distinct advantages:

- 1.

- Consistency and completeness: Eliminates the subjective biases and annotation omissions inherent in manual labeling.

- 2.

- Low-cost scalability: Enables the generation of large-scale, richly annotated datasets at a near-zero marginal cost, removing the primary barrier to data scaling.

- 3.

- Annotation precision: In contrast to the inherent imprecision of manual labeling, our approach guarantees tightly fitted boxes derived from instance segmentations, thus providing superior annotation quality.

| Algorithm 1 Automated Annotation from Semantic Masks |

|

In summary, high-fidelity scene modeling ensures consistency with real-world environments, diversified rendering enhances the model’s robustness to complex scenarios, and fully automated ground-truth generation resolves the cost bottleneck of large-scale labeling.

4. Results

This section systematically validates the effectiveness and superiority of our proposed high-fidelity synthetic data generation framework through a series of comprehensive experiments. Our evaluation revolves around several core dimensions. First, we conduct a direct performance comparison of our generated synthetic dataset, UAV-SynthScene, against real data and two other mainstream public synthetic datasets to confirm its viability as an effective supplement to real data. Next, we delve into the framework’s robustness in handling typical long-tail distribution scenarios, such as “truncated objects.” Furthermore, we assess the cross-domain generalization capability of models trained exclusively on our synthetic data in unseen environments through zero-shot transfer experiments. Finally, through meticulous ablation studies, we precisely quantify the individual key contributions of the two core components of our framework: high-fidelity scene reconstruction and diversified rendering.

4.1. Datasets

Our experiments are conducted on a collection of real and synthetic UAV datasets:

- UAV-RealScene: A real dataset captured by DJI Mavic 3T UAVs (Shenzhen, China) across an area of approximately 1000 m × 2000 m, covering both urban and suburban environments. It contains 8736 images at a resolution of 640 × 480, with 8000 images used for training and 736 for testing. All vehicle instances are manually annotated. This dataset serves as the real-world benchmark for performance comparison.

- UAV-SynthScene: Constructed using the proposed synthetic data generation framework. Ten flight paths were designed, with altitudes randomly sampled between 50–300 m, heading and pitch angles varied within −10° to 10° and −45° to −90°, respectively, while roll angles were fixed at 0°. In total, 4659 images of resolution 1920 × 1536 were generated. The rendering process incorporated diverse weather conditions (sunny, cloudy, foggy) and lighting conditions (sunrise, noon, sunset), with dynamic simulation of solar and cloud variations to enhance generalization.

- SkyScenes [13]: A large-scale public synthetic dataset for aerial scene understanding. This dataset is generated using a high-fidelity simulator and provides rich annotations for various computer vision tasks. In our experiments, SkyScenes serves as an advanced synthetic data benchmark for performance comparison with the proposed data generation method.

- UEMM-Air [54]: A large-scale multimodal synthetic dataset constructed using Unreal Engine, covering aerial scenes, environmental variations, and multi-task annotations. It is used in ablation studies to compare the performance of our high-fidelity reconstruction approach against generic 3D asset–based generation.

- RGBT-Tiny [55]: A public UAV-based visible-thermal benchmark dataset containing multiple image sequences. In our cross-domain generalization tests, to maintain evaluation consistency, we selected one representative sequence for testing.

- VisDrone [56]: A large-scale, challenging benchmark dataset captured by various drone platforms across 14 different cities in China. It encompasses a wide spectrum of complex scenarios, including dense traffic, cluttered backgrounds, and significant variations in object scale and viewpoint. Due to its diversity and difficulty, VisDrone serves as an ideal unseen real-world benchmark in our experiments to rigorously evaluate the cross-domain generalization capability of the models.

4.2. Implementation Settings

The majority of our experiments were implemented using the MMDetection toolbox [57] on a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU. Models available in this library (DINO, Deformable-DETR [58], DDQ [59]) were trained using their default configurations with a ResNet-50 backbone and a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) neck. For detectors not integrated into MMDetection, we utilized their official open-source implementations: DEIM [60] was trained using its author-provided code, YOLOv11 and RT-DETR [61] were trained via Ultralytics. All vehicle types are treated as a single category for both training and evaluation.

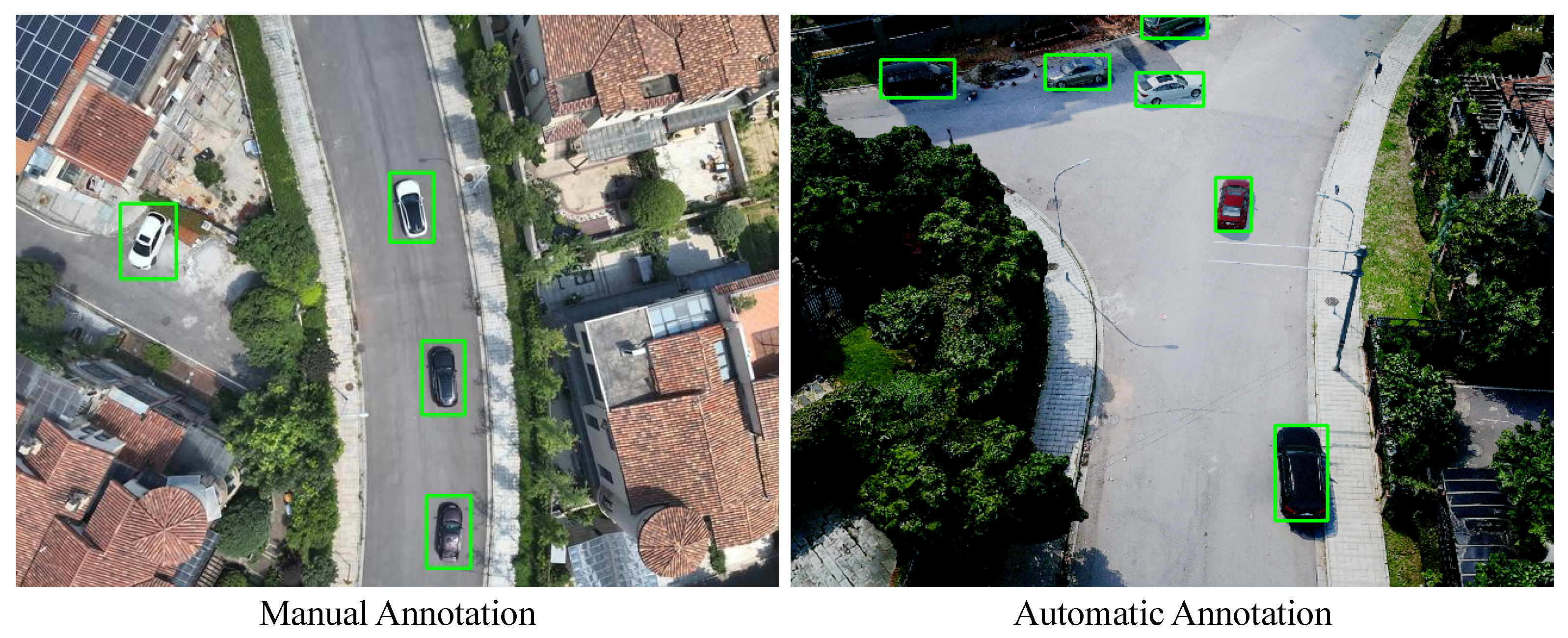

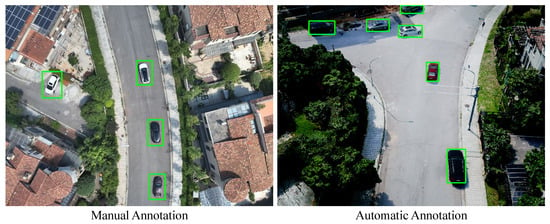

For performance evaluation, we adhere to the official COCO protocol. It is crucial to note the discrepancy between the ground truth annotations in our synthetic data and those in real datasets. The bounding boxes in our synthetic datasets are programmatically derived from pixel-perfect instance masks, yielding exceptionally precise boundaries. Conversely, manual annotations may exhibit unavoidable looseness due to annotation subjectivity (Figure 7). This inherent difference can lead to the penalization of accurate predictions at high Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds (e.g., , ). To mitigate this bias and focus more on detection recall than on hyper-precise localization, we have selected as our primary evaluation metric. Accordingly, will serve as the default metric for all experiments presented hereafter, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Figure 7.

Comparison of annotation precision. The green rectangles represent the Ground Truth (GT) bounding box annotations. (Left) Manual annotations often exhibit looseness and include excessive background. (Right) Our automated method ensures pixel-level tightness derived from instance masks.

4.3. Performance Evaluation

4.3.1. Effectiveness of Synthetic Data as a Scalable Supplement to Real Data

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of our UAV-SynthScene dataset, we conducted rigorous performance benchmark tests against the real-world UAV-RealScene dataset and two other public synthetic datasets, SkyScenes and UEMM-Air. Significantly, to ensure practical meaning, all experiments utilized real data as the evaluation benchmark. Specifically, six representative detectors, including YOLOv11, Deformable-DETR, DINO, DDQ, DEIM, and RT-DETR, are selected for experimental validation. These models cover both Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based and Transformer-based architectures, encompassing high-accuracy and real-time detection paradigms. This comprehensive evaluation is designed to assess the general applicability of the proposed synthetic dataset across different architectures, thereby ensuring the robustness and generality of the research conclusions.

The experimental results are presented in Table 1. The analysis reveals several key points. First, the performance of models trained exclusively on our UAV-SynthScene is remarkably close to that of models trained on the large-scale real-world UAV-RealScene data. Using the metric as an example, the model trained on our synthetic data achieved 87.9% with the DINO detector, which is identical to the performance of the model trained on real data. Second, compared to the other two synthetic datasets, our UAV-SynthScene demonstrates a clear advantage. For instance, when using the DEIM detector, our model achieved an of 88.7%, significantly outperforming models trained on SkyScenes (86.5%) and UEMM-Air (72.0%). This performance advantage is consistent across all tested detector architectures, strongly proving that our strategy of combining high-fidelity reconstruction with diversified rendering is superior to existing synthetic data generation methods in bridging the Sim2Real gap.

Table 1.

Performance comparison across different detector architectures and training datasets on the full UAV-RealScene test set. The best results are marked in bold.

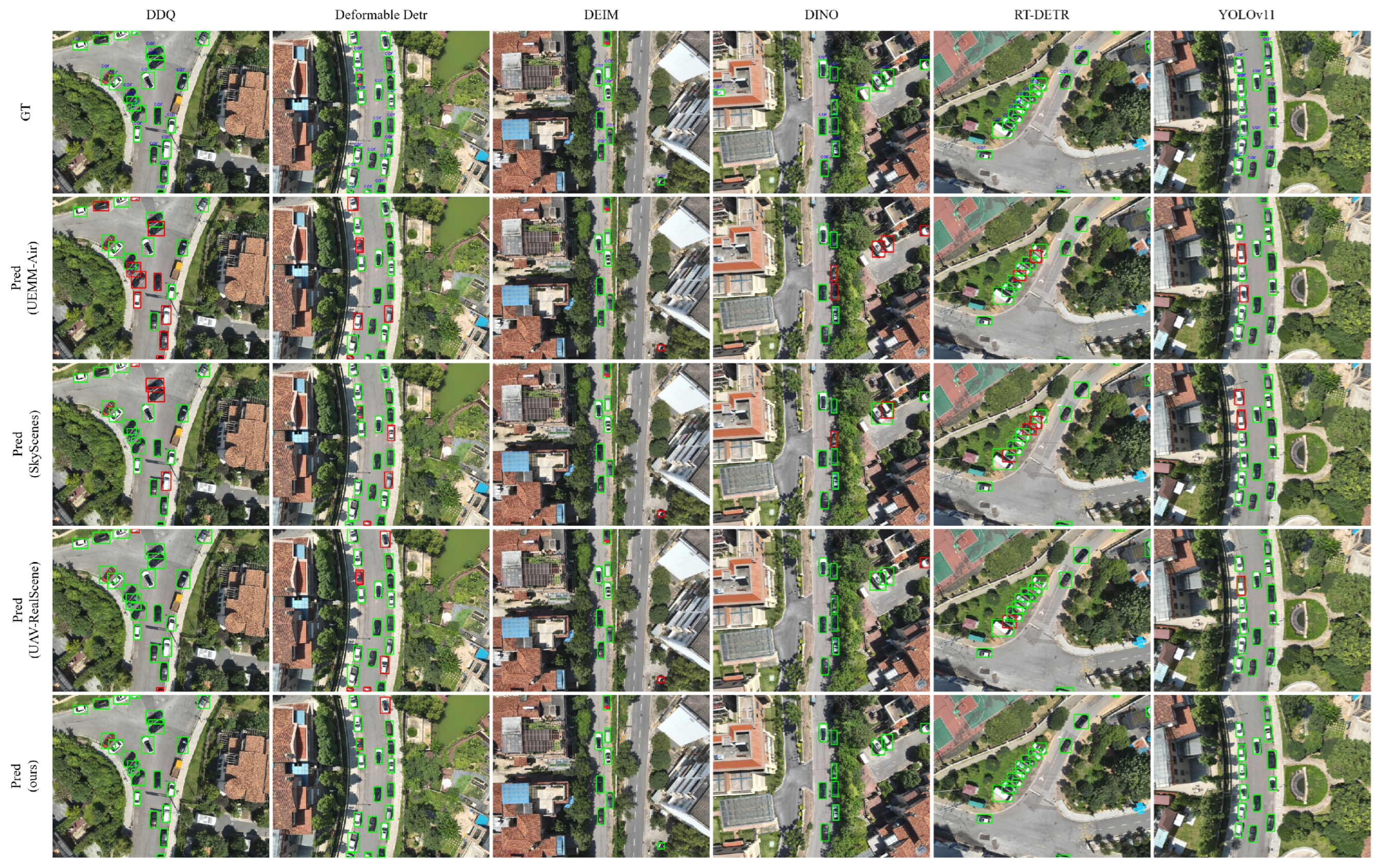

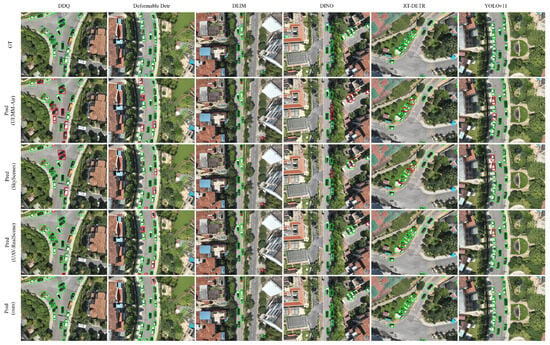

In addition to the quantitative metrics, we further conducted a qualitative analysis through visualization of the detection results (Figure 8) to gain deeper insights into the impact of different training datasets on model robustness, green bounding boxes denote correctly detected vehicles, while red boxes prominently highlight missed detections (false negatives). A clear visual inspection reveals that models trained on SkyScenes and UEMM-Air exhibit severe missed detections, as evidenced by the abundance of red boxes. In sharp contrast, models trained on our UAV-SynthScene dataset (“Pred (ours)” row) show a remarkable reduction in missed detections. As illustrated, the number of red boxes is minimal, indicating superior detection completeness that even surpasses models trained solely on real data.

Figure 8.

Qualitative results on real-world imagery. The first row displays the GT. Models were trained on UEMM-Air (row 2), SkyScenes (row 3), real data (row 4), and our synthetic data (row 5). Green boxes denote correct detections (True Positives), while red boxes highlight missed detections (False Negatives). Our method (row 5) demonstrates substantially higher recall and robustness, significantly outperforming all other training datasets.

This demonstrates that the proposed synthetic data can provide detection performance comparable to manually collected real data, effectively bridging the Sim2Real gap. Thus, synthetic data can serve as a high-quality supplement to costly, manually annotated real imagery.

4.3.2. Robustness in Long-Tail Scenarios

One of the core strengths of synthetic data lies in its ability to actively control data distribution, thereby addressing inherent sampling biases in real datasets. To validate this, we focused on truncated objects, which represent a typical long-tail scenario.

As shown in Table 2 and visually evidenced in Figure 8, the proposed synthetic dataset achieves markedly superior detection performance on truncated vehicles compared to both real-world and existing synthetic datasets. Models trained on UAV-SynthScene exhibit notably higher recall for partially visible targets, effectively mitigating the severe missed detections observed in SkyScenes and UEMM-Air.

Table 2.

Performance comparison on the truncated-object subset of the UAV-RealScene test set. The best results are marked in bold.

Across all detectors, models trained on UAV-SynthScene consistently and substantially outperform those trained on all other datasets (including real data) in detecting truncated objects. For example, with the DINO detector, our model achieved an of 73.0% on the truncated-object test set, which not only far surpasses the model trained on real data (56.3%) but also significantly exceeds those trained on SkyScenes (56.9%) and UEMM-Air (50.8%). Furthermore, the Recall metric supports this advantage, showing that our framework maintains robust detection completeness for boundary targets. These results suggest that the active generation strategy effectively helps reduce missed detections for such hard-to-capture instances.

This strong quantitative and qualitative consistency demonstrates that the active long-tail sample generation strategy embedded in our framework is highly effective. It enables precise augmentation of sparse yet crucial sample categories in real data, thereby greatly enhancing the model’s robustness in complex and non-ideal long-tail detection scenarios.

4.3.3. Cross-Domain Generalization

To assess the cross-domain generalization of our synthetic data, we conducted a series of zero-shot transfer experiments. Models trained on UAV-SynthScene and three baseline datasets (one real, two synthetic) were evaluated directly on two unseen real-world benchmarks, RGBT-Tiny and VisDrone, without any fine-tuning.

The results, presented in Table 3, indicate a clear advantage in generalization for models trained on our UAV-SynthScene. Across most detector architectures, our synthetic-data-trained models consistently outperform those trained on the other synthetic baselines (SkyScenes and UEMM-Air). Notably, in several instances, their performance is also highly competitive with or even exceeds that of models trained on our real data (UAV-RealScene).

Table 3.

Cross-domain generalization performance across different training datasets on unseen real-world benchmarks (RGBT-Tiny and VisDrone). The best results are marked in bold.

For example, when evaluated on the RGBT-Tiny benchmark, the DINO model trained on UAV-SynthScene achieves 96.5% . This result is substantially higher than the performance of models trained on SkyScenes (76.5%) and UEMM-Air (65.0%), and is closely comparable to the in-domain real-data baseline (97.1%). Similar performance trends are observed on the VisDrone dataset.

These findings suggest that our high-fidelity synthetic data generation strategy yields synthetic data with strong transferability. The combination of a photorealistic scene foundation and diversified rendering likely enables the models to learn more fundamental and robust visual representations, contributing to improved generalization performance in novel real-world environments.

4.4. Ablation Study

To quantify the independent contributions of the two core components in our framework—high-fidelity scene reconstruction (Fidelity) and diversified rendering (Diversity)—we conducted a series of ablation studies across all five detectors.

Contribution of diversified rendering. To quantify the contribution of our diversified rendering strategies, we created a baseline dataset, UAV-SynthScene-Static, by rendering all images under a fixed set of conditions: clear noon lighting from a static viewpoint (150 m altitude, −80° pitch, 0° roll/yaw). We then trained all five detector architectures on both this static dataset and our full, diversified dataset. The performance of these models was evaluated on two versions of the real-world test set: the complete set (“Overall”) and a challenging subset containing only truncated objects (“Trunc.”).

The detailed results, presented in Table 4, reveal a stark performance degradation when diversified rendering is removed. On average, the across all detectors drops by nearly 10 points on the “Overall” set and a staggering 20 points on the “Trunc.” subset. To highlight a specific example, the DINO detector’s performance on truncated objects plummets from 73.0% with our full method to a mere 44.2% when trained on the static data. This substantial gap underscores that exposing the model to a wide spectrum of environmental conditions is not merely beneficial but essential for learning robust features that can generalize to the unpredictable nature of real-world scenarios.

Table 4.

Ablation study on the impact of diversified rendering. Performance (mAP50) is compared on the full test set (Overall) and its truncated subset (Trunc.).

Contribution of High-Fidelity Reconstruction. To evaluate the importance of high-fidelity scene reconstruction, we compared our approach against Generic-Synth3D, a dataset generated using generic 3D assets but also incorporating diversified rendering. This allows us to isolate the impact of the scene’s foundational realism. Models were trained on these respective datasets and evaluated on our real-world test set, with performance measured on both the complete set (“Overall”) and its truncated subset (“Trunc.”).

The results, presented in Table 5, reveal a dramatic performance gap and unequivocally demonstrate the critical role of scene fidelity. Models trained on the Generic-Synth3D dataset consistently and substantially underperform those trained on our photogrammetry-based UAV-SynthScene. As highlighted by the “Average” row, switching from generic assets to our high-fidelity scenes yields a staggering average improvement of +22.5 points. The performance leap is particularly pronounced for detectors like RT-DETR, which saw a gain of +27.5 points. This massive disparity validates our core hypothesis: high-fidelity reconstruction is the cornerstone of effective Sim2Real transfer. By mirroring the unique geometry and textures of the target environment, our method enables models to learn priors that are directly and effectively transferable, paving the way for performance that rivals real-world training data.

Table 5.

Impact of high-fidelity scene reconstruction on detector performance.

5. Discussion

Experimental results demonstrate that high-fidelity synthetic data can effectively bridge the Sim2Real gap for UAV-based vehicle detection. This section discusses the broader implications of these findings, positions our work in the context of existing literature, and outlines its limitations and future research directions.

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

The near-identical performance between models trained on UAV-SynthScene and UAV-RealScene (as shown in Table 1) is a significant finding. It suggests that for UAV-based object detection, the “reality gap” can be substantially closed if the synthetic environment accurately captures the geospatial structure and textural characteristics of the target domain. Our results from the ablation study (Table 5) strongly support this, revealing that high-fidelity reconstruction contributed a substantial +23.3 gain over generic 3D assets. This confirms our central hypothesis: for top-down remote sensing views, structural and textural fidelity is a more critical factor than for ground-level vision, where generic urban layouts can often suffice.

Furthermore, the superior performance in long-tail scenarios (Table 2) highlights a fundamental advantage of simulation. Real data collection is inherently a process of passive, uncontrolled sampling, leading to inevitable data imbalances. Our framework transforms this into a process of active, goal-oriented sampling. By programmatically generating truncated and occluded objects, we can directly address known failure modes of detectors, a capability that traditional data augmentation or post-hoc resampling methods cannot fully replicate.

5.2. Comparison with Existing Works and Methodological Implications

Our high-fidelity approach presents a conceptual counterpoint to the philosophy of pure domain randomization, which often sacrifices realism for diversity. While DR is effective for learning domain-agnostic features, our results indicate that for geo-specific tasks, starting from a high-fidelity baseline provides a much stronger foundation. The strong cross-domain generalization performance (Table 3) suggests that our method, by combining a realistic foundation with controlled diversity, allows models to learn features that are not only robust but also more transferable to novel geographic environments.

Compared to other high-fidelity simulation datasets like SkyScenes [13], our framework’s key differentiator is the use of photogrammetry-based digital twins instead of artist-created 3D worlds. While the latter can be visually stunning, they may lack the subtle, imperfect, and unique signatures of a real location. The consistent performance advantage of UAV-SynthScene suggests that these authentic geo-specific details are crucial for training models that can operate reliably in the real world. This work therefore advocates for a tighter integration of survey-grade 3D mapping techniques (such as photogrammetry and LiDAR) into the pipeline of synthetic data generation for geospatial artificial intelligence.

5.3. Implications for Remote Sensing Applications

The findings of this study have significant practical implications for the remote sensing community. The proposed framework offers a scalable and cost-effective pathway to overcome the data annotation bottleneck, which is a major impediment to the deployment of artificial intelligence in areas such as:

- Urban Planning and Traffic Management: Large-scale, diverse datasets of vehicle behavior can be generated for different cities without extensive manual annotation, enabling the development of more robust traffic monitoring systems.

- Disaster Response and Damage Assessment: By creating digital twins of pre-disaster areas, it becomes possible to simulate post-disaster scenarios (e.g., placing debris, damaged vehicles), thereby generating crucial training data for automated damage detection systems before a real event occurs.

- Sensor Simulation and Mission Planning: The framework can be used as a high-fidelity sensor simulator. This allows for testing and validating new perception algorithms or planning UAV survey missions under a wide range of simulated environmental conditions (e.g., different times of day, weather) to predict performance and optimize flight parameters.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Although the proposed framework has proven effective, certain limitations remain. First, the current reliance on static digital twins does not account for environmental dynamics, such as seasonal vegetation shifts and urban development. Future work should explore updating 3D environments using multi-temporal satellite imagery or periodic UAV surveys to dynamically refresh scene topology and textures, thereby maintaining fidelity for long-term monitoring. Second, while the framework effectively addresses geometric long-tail scenarios (e.g., truncated objects), a fidelity gap persists under complex illumination. Although photogrammetry ensures geometric consistency, the interaction between simulated lighting and reconstructed textures inevitably approximates real-world optics. This discrepancy may lead to missed detections under extreme lighting or complex material reflectance conditions. Finally, while this study focuses on the independent transferability of synthetic data, future research should explore joint training strategies that combine synthetic and real-world datasets. Such mixed-training approaches represent a promising avenue for further boosting detector performance in practical applications.

While the proposed framework offers clear advantages in data scalability, it is important to acknowledge practical trade-offs relative to real-world data collection. Real UAV data acquisition typically incurs high operational costs, including flight permissions, specialized equipment, and personnel, and annotation effort increases linearly with dataset size. In contrast, the proposed framework relies on a limited amount of real UAV imagery for photogrammetric reconstruction rather than large-scale data collection. Although this introduces upfront modeling and computational costs, the imagery used for reconstruction does not require manual bounding box annotation. Once this foundation is established, the marginal cost of generating and annotating large volumes of synthetic data is relatively low. As a result, the proposed framework is well suited to difficult, rare, or unsafe scenarios and serves as a supplement to real-world UAV data rather than a replacement.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduces a high-fidelity synthetic data generation framework for UAV-based remote sensing. Our framework integrates oblique photogrammetry with diversified rendering strategies to bridge the Sim2Real gap. Extensive experiments on multiple real-world datasets demonstrate that detectors trained solely on our synthetic dataset, UAV-SynthScene, achieve performance comparable to those trained on large-scale manually annotated real data. Crucially, the proposed synthetic data are not intended to replace real data but to serve as a scalable supplement, alleviating data scarcity and enhancing robustness in scenarios where real data is limited or difficult to acquire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L. and Y.L.; methodology, F.L.; software, F.L. and Y.L.; validation, W.X., X.W. and G.L.; formal analysis, W.X.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, K.Y.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.; writing—review and editing, W.X.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, W.X.; project administration, W.X., X.W. and G.L.; funding acquisition, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The public benchmark datasets used for comparison in this study are available at their respective official websites: SkyScenes at https://hoffman-group.github.io/SkyScenes/ (accessed on 6 January 2026), UEMM-Air at https://github.com/1e12Leon/UEMM-Air (accessed on 8 January 2026), and the VisDrone dataset at https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset (accessed on 10 January 2026). The source code for the proposed data generation framework and the complete UAV-SynthScene dataset generated in this study will be made publicly available upon acceptance of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| Sim2Real | Simulation-to-Reality |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| VAEs | Variational Autoencoders |

| DR | Domain Randomization |

| DA | Domain Adaptation |

| RGB | Red-Green-Blue |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| AP | Average Precision |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| mAP50 | mean Average Precision at IoU = 50% |

| mAP75 | mean Average Precision at IoU = 75% |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| DETR | Detection Transformer |

| DINO | DETR with Improved Denoising Anchor Boxes |

| RT-DETR | Real-Time DETR |

| DDQ | Dense Distinct Query |

| DEIM | DETR with Improved Matching |

References

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Arun, P.V.; Jiao, C.; Zhou, H.; Xiang, P.; Cheng, K. Siamstu: Hyperspectral video tracker based on spectral spatial angle mapping enhancement and state aware template update. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 150, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yan, W.; You, M.; Zhang, J.; Arun, P.V.; Jiao, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral anomaly detection based on empirical mode decomposition and local weighted contrast. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 33847–33861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2014); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.-J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2009), Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Lian, S.; Pan, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W. AD-DET: Boosting object detection in UAV images with focused small objects and balanced tail classes. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, T.; Chen, C. Towards resolving the challenge of long-tail distribution in UAV images for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV 2021), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 3258–3267. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Ros, G.; Codevilla, F.; Lopez, A.; Koltun, V. CARLA: An open urban driving simulator. In Proceedings of the PLMR Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL 2017), Mountain View, CA, USA, 13–15 November 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Dey, D.; Lovett, C.; Kapoor, A. AirSim: High-fidelity visual and physical simulation for autonomous vehicles. In Field and Service Robotics (FSR 2017); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 621–635. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, S.; Yan, W.; Shen, Q.; Wang, C.; Yang, M. Choose your simulator wisely: A review on open-source simulators for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 4861–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisic, A.; Petric, F.; Bogdan, S. Sim2Air—Synthetic aerial dataset for UAV monitoring. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 3757–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxey, C.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.; Manocha, D.; Kwon, H. UAV-Sim: NeRF-based synthetic data generation for UAV-based perception. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2024), Paris, France, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 5323–5329. [Google Scholar]

- Rüter, J.; Maienschein, T.; Schirmer, S.; Schopferer, S. Filling the gaps: Using synthetic low-altitude aerial images to increase operational design domain coverage. Sensors 2024, 24, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khose, S.; Pal, A.; Agarwal, A.; Deepanshi; Hoffman, J.; Chattopadhyay, P. Skyscenes: A synthetic dataset for aerial scene understanding. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2024), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J. Learning from synthetic data for object detection on aerial images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image, Signal Processing, and Pattern Recognition (ISPP 2024), Beijing, China, 15–17 July 2024; Volume 13180, pp. 832–838. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cisse, M.; Dauphin, Y.N.; Lopez-Paz, D. Mixup: Beyond empirical risk minimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2018), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, G.; Cui, Y.; Srinivas, A.; Qian, R.; Lin, T.-Y.; Cubuk, E.D.; Le, Q.V.; Zoph, B. Simple copy-paste is a strong data augmentation method for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2021), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 2918–2928. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, A.; Pfister, T.; Tuzel, O.; Susskind, J.; Wang, W.; Webb, R. Learning from simulated and unsupervised images through adversarial training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2017), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–23 July 2017; pp. 2107–2116. [Google Scholar]

- Gaidon, A.; Wang, Q.; Cabon, Y.; Vig, E. Virtual worlds as proxy for multi-object tracking analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 4340–4349. [Google Scholar]

- Ros, G.; Sellart, L.; Materzynska, J.; Vazquez, D.; Lopez, A.M. The SYNTHIA dataset: A large collection of synthetic images for semantic segmentation of urban scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 3234–3243. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, S.R.; Vineet, V.; Roth, S.; Koltun, V. Playing for data: Ground truth from computer games. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2016), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–16 October 2016; pp. 102–118. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Roberson, M.; Barto, C.; Mehta, R.; Sridhar, S.N.; Rosaen, K.; Vasudevan, R. Driving in the matrix: Can virtual worlds replace human-generated annotations for real world tasks? In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2017), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 746–753. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, J.; Prakash, A.; Acuna, D.; Brophy, M.; Jampani, V.; Anil, C.; To, T.; Cameracci, E.; Boochoon, S.; Birchfield, S. Training deep networks with synthetic data: Bridging the reality gap by domain randomization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW 2018), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 16–20 June 2018; pp. 969–977. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes Reyes, M.; Xie, Y.; Yuan, X.; d’Angelo, P.; Kurz, F.; Cerra, D.; Tian, J. A 2D/3D multimodal data simulation approach with applications on urban semantic segmentation, building extraction and change detection. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 205, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, H.; Wang, Y.; Dianati, M.; Debattista, K.; Donzella, V. A unified generative framework for realistic LiDAR simulation in autonomous driving systems. IEEE Sensors J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, C.; Pan, X.; Li, Z. Digital twin-assisted graph matching multi-task object detection method in complex traffic scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, E.; Hoffman, J.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Adversarial discriminative domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2017), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–23 July 2017; pp. 7167–7176. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Sakaridis, C.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Domain adaptive faster R-CNN for object detection in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2018), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3339–3348. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Tao, D.; Yu, Z.; Qi, G. Attribute-aligned domain-invariant feature learning for unsupervised domain adaptation person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 16, 1480–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Ou, Z.; Wu, T. Domain-invariant progressive knowledge distillation for UAV-based object detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, B.; Diaz, M.; Golemo, F.; Pal, C.J.; Paull, L. Active domain randomization. In Proceedings of the PLMR Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL 2020), Auckland, New Zealand, 30 November–3 December 2020; pp. 1162–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. LVIS: A dataset for large vocabulary instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 5356–5364. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Ji, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Peng, Z.; Wang, R.; Fang, L.; Shen, C. Hard adversarial example mining for improving robust fairness. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 20, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wu, G.; Li, C. Toward understanding generative data augmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 54046–54060. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Hong, F.; Yao, J.; Han, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Revive re-weighting in imbalanced learning by density ratio estimation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 79909–79934. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Pan, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, D.; Jiang, J. Decoupled training: Return of frustratingly easy multi-domain learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2024), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–22 February 2024; pp. 15644–15652. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Yan, S.; He, X.; Sun, J. Distribution alignment: A unified framework for long-tail visual recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2021), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 2361–2370. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Bai, S.; Li, A.; Cui, J.; Wang, L. Dense relation distillation with context-aware aggregation for few-shot object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2021), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 10185–10194. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, J.; Ye, Y.; Mo, M.; Gao, C.; Gan, J.; Xiao, B.; Gao, X. Recent advances for aerial object detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27 June–1 July 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Ni, L.M.; Shum, H.-Y. DINO: DETR with improved denoising anchor boxes for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.03605. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Huang, K.; Zhu, X.; Arun, P.V.; Jiang, W.; Li, S.; Pei, X.; Zhou, H. SASU-Net: Hyperspectral video tracker based on spectral adaptive aggregation weighting and scale updating. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 272, 126721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Sheng, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cai, L.; Ling, H. M2Det: A single-shot object detector based on multi-level feature pyramid network. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2019), Honolulu, HI, USA, 2–7 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, M.; Huang, K.; Zhong, W.; Arun, P.V.; Li, Y.; Asano, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhou, H. OCSCNet-tracker: Hyperspectral video tracker based on octave convolution and spatial–spectral capsule network. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, B.; Jiang, W.; Zhong, W.; Arun, P.V.; Cheng, K.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral video tracker based on spectral difference matching reduction and deep spectral target perception features. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 194, 109124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, D.; Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Arun, P.V.; Asano, Y.; Xiang, P.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral video object tracking with cross-modal spectral complementary and memory prompt network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 295, 114595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhong, W.; Ge, M.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, X.; Arun, P.V.; Zhou, H. SIAMBsi: Hyperspectral video tracker based on band correlation grouping and spatial-spectral information interaction. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 126, 106063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Laboratories LLC. Colosseum: Open Source Simulator for Autonomous Robotics Built on Unreal Engine with Support for Unity. Available online: https://github.com/CodexLabsLLC/Colosseum (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Liu, F.; Yao, L.; Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, T. UEMM-Air: A Synthetic Multi-Modal Dataset for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, X.; Xiao, C.; An, W.; Li, R.; He, X.; Li, B.; Cao, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; et al. Visible-thermal tiny object detection: A benchmark dataset and baselines. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 6088–6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q.; Peng, T.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. VisDrone-DET2019: The vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW 2019), Seoul, Republic of the Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Pang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, S.; Feng, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. MMDetection: Open MMLab detection toolbox and benchmark. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable-DETR: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Pang, J.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, W.; Luo, P.; Chen, K. Dense distinct query for end-to-end object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2023), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19–24 June 2023; pp. 7329–7338. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Lu, Z.; Cun, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X. DEIM: DETR with improved matching for fast convergence. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference (CVPR 2025), Paris, France, 16–21 June 2025; pp. 15162–15171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2024), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.