Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This study proposes a multi-source hybrid network integrating CNN and Transformer, which synergistically extracts local and global features for high-accuracy phenology monitoring.

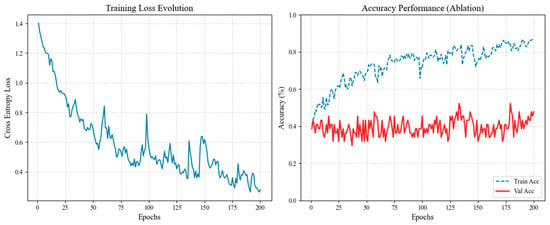

- Ablation studies demonstrate the superiority of the hybrid architecture, achieving 98.4% accuracy and significantly outperforming a pure CNN model (85.7%), validating the Transformer’s role in capturing global dependencies.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The proposed method establishes an effective multi-modal data fusion framework for precision agriculture, enhancing automated crop monitoring under complex environmental conditions.

- By combining CNN-based local feature extraction with Transformer-based global attention, our approach robustly infers phenology under water and nitrogen stress, offering a new pathway for analyzing crop stress responses.

Abstract

Effective monitoring of maize phenology under stress conditions is crucial for optimizing agricultural management and mitigating yield losses. Crop prediction models constructed from Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) have been widely applied. However, CNNs often struggle to capture long-range temporal dependencies in phenological data, which are crucial for modeling seasonal and cyclic patterns. The Transformer model complements this by leveraging self-attention mechanisms to effectively handle global contexts and extended sequences in phenology-related tasks. The Transformer model has the global understanding ability that CNN does not have due to its multi-head attention. This study, proposes a synergistic framework, in combining CNN with Transformer model to realize global-local feature synergy using two models, proposes an innovative phenological monitoring model utilizing near-ground remote sensing technology. High-resolution imagery of maize fields was collected using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with multispectral and thermal infrared cameras. By integrating this data with CNN and Transformer architectures, the proposed model enables accurate inversion and quantitative analysis of maize phenological traits. In the experiment, a network was constructed adopting multispectral and thermal infrared images from maize fields, and the model was validated using the collected experimental data. The results showed that the integration of multispectral imagery and accumulated temperature achieved an accuracy of 92.9%, while the inclusion of thermal infrared imagery further improved the accuracy to 97.5%. This study highlights the potential of UAV-based remote sensing, combined with CNN and Transformer as a transformative approach for precision agriculture.

1. Introduction

Crop phenology, the sequence of plant developmental stages, is a critical determinant of yield and a key indicator for optimizing management practices like irrigation and fertilization. Nitrogen management applied during the three-leaf and five-leaf stages of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) advanced root development and retarded leaf senescence, leading to improved nitrogen absorption and assimilation [1]. Water deficit has been shown to significantly alter developmental rhythms by affecting cell division and expansion, often leading to a shortened growing period [2,3]. Conversely, nitrogen deficiency can delay the onset of reproductive stages and prolong vegetative growth. Such divergent and non-linear shifts caused by water–nitrogen interactions [4,5,6] make it difficult for parametric curve-fitting methods to maintain high accuracy under complex field conditions [7].

Manual scouting often relies on sparse point-sampling, which fails to capture the spatial heterogeneity of crop development across expansive fields [8]. Moreover, the descriptive nature of manual records is difficult to integrate directly into automated precision agriculture systems. Therefore, there is a critical need for an automated, high-throughput scouting tool that can translate point-based phenological observations into surface-based digital phenology maps.

In current research, methods for predicting phenology are mainly divided into two categories: process-based prediction methods and data-driven prediction methods.

Process-based phenology prediction methods often rely on meteorological factors, typically using accumulated effective temperature (also known as growing degree days or thermal units) as its primary input. Classical remote sensing phenology extraction methods, such as time-series vegetation index (VI) curve fitting (e.g., Savitzky-Golay, asymmetric Gaussian, or Logistic functions [9]) and dynamic threshold methods, have been widely implemented across various scales.

Recent advancements in remote sensing-based phenological monitoring have significantly enhanced the precision of vegetation growth characterization across agricultural ecosystems. A reconstruction methodology using Sentinel-2 imagery and Savitzky-Golay (S-G) filtering for urban street trees, effectively capturing intra-annual stress events while maintaining low index variability (standard deviation: 0.02–0.03 for NDVI during maturity) [9] For high-throughput crop breeding, a kind of utilized UAV multispectral time-series data can identify soybean initial anthesis. This approach, employing a Symmetric Gauss Function (SGF) with the first-order derivative maximal feature (FDmax) on the red-edge index, achieved high accuracy with a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 3.79 days and a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 3.00 days [10]. Furthermore, A modified dynamic threshold method for MODIS-based crop phenology optimized yielded robust results, such as an RMSE of 8.1 days for summer maize (Zea mays L.) and an RMSE of 7.9 days for winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that the integration of sensor-specific indices and optimized curve-fitting algorithms is critical for achieving high-precision phenological estimations in diverse environmental contexts [7].

However, these traditional algorithms often rely on the assumption of an idealized, smooth growth trajectory, which limits their performance when crops exhibit non-linear physiological responses to environmental stressors. It works by cumulatively tracking the effective growth temperature over time to model a crop’s growth prediction curve, with specific phenological stages as the output variable [11]. Data-driven phenology prediction methods leverage multi-source information, such as remote sensing imagery, meteorological data, and soil data, to predict crop phenology using machine learning or deep learning algorithms. This approach captures patterns of crop phenological development through data analysis. For example, a visible light camera was used to capture images of flowers from three peach blossom varieties [12]. They employed four machine learning models—Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Naive Bayes (NB), and k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)—for phenology retrieval, finding that the RF model achieved the highest accuracy (an F1-score of 98.82%).

Satellite-based remote sensing such as Sentinel-2, Landsat is highly effective for large-scale phenological monitoring at county or regional levels, it often lacks the spatial and temporal granularity required for precision agriculture [13]. Satellite imagery, typically constrained by 10–30 m resolutions and fixed revisit cycles, faces challenges in capturing subtle phological changes, especially under cloud-prone conditions [14].

Recent years, the decreasing cost of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-borne sensor technology has made it increasingly feasible to acquire multispectral (MS) and thermal infrared (TIR) imagery of farmlands. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) provide centimeter-level spatial resolution and on-demand temporal flexibility. This ‘near-ground’ perspective is essential for decoupling complex crop–environment interactions, such as canopy temperature gradients under localized water and nitrogen stress, which remain largely undetectable by current satellite sensors.

The near-infrared (NIR) band in multispectral imagery, with wavelengths typically ranging from 760–900 nm, exhibits strong water absorption and is sensitive to water bodies and soil moisture content. For instance, a novel crop classification model based on multispectral remote sensing images was proposed, achieving efficient crop classification by combining Wavelet transform, RetinaNet feature extractor, and Deep Supervised Optimization (DSO) with Deep Self-Autoencoder (DSAE) to analyze 90,691 multispectral samples from the Indian Pine, Salinas, and University of Pavia datasets [15]. Similarly, Camoglu utilized multispectral data to non-destructively detect invisible water stress in agriculture and identify the irrigation threshold [16]. They also estimated the yield and physiological characteristics of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) under different levels of water stress. Furthermore, healthy vegetation exhibits a rapid increase in reflectance with wavelength in the red-edge band region of multispectral imagery. This phenomenon, known as the Red Edge Effect, can be used to detect plant chlorophyll concentration [17]. Thermal Infrared (TIR) imaging is a technique that acquires images by detecting thermal radiation emitted from an object [18]. TIR images are commonly used to display surface temperature distribution and can assess plant transpiration and water stress status [19]. There is a growing trend to integrate multispectral and thermal infrared imagery for retrieving crop growth status [20,21]. For example, a CNN model was established using thermal infrared and multispectral data from UAV-captured maize canopy images under different water and nitrogen treatments [17]. This model was used to retrieve the leaf area index (LAI) and leaf chlorophyll content (LCC) of maize at various growth stages. Their experimental results indicated that combining MS and TIR data significantly improved estimation accuracy, with R2 values for LAI and LCC increasing by 23.06% and 19.01%, respectively. Furthermore, UAVs equipped with both multispectral (MS) and thermal infrared (TIR) sensors can be used to retrieve the Crop Water Stress Index (CWSI) for wheat [22].

While these studies confirm that combining thermal infrared (TIR) and multispectral (MS) data can improve the retrieval accuracy of crop growth status, whether this combination can also be used to accurately estimate phenological stages remains to be explored. On the one hand, the advancement of crop phenology is not only related to the specific crop variety but is also influenced by environmental factors. For instance, water stress during the seedling and early jointing stages can delay the phenological development of maize [23], whereas water stress at the jointing stage can accelerate maize senescence, leading to an earlier onset of phenological events [24]. An analysis of nitrogen stress data for 117 species demonstrated that high-nitrogen treatments cause significant changes in plant phenology [25]; with the exception of the grain-filling period, all phenological timings were significantly delayed, and the overall phenological duration was shortened. However, it remains uncertain whether the synergistic use of multispectral (MS) and thermal infrared (TIR) data can accurately capture the influence of these factors on phenology. On the other hand, algorithmically, CNN is commonly employed for extracting local features and exhibit certain limitations in representing global features [26]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop specialized methods for phenology retrieval that account for environmental impacts, in order to improve the accuracy of crop phenological estimations.

Transformer, based on a self-attention mechanism, has become a prominent model in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) [27]. Numerous studies have shown that introducing the Transformer architecture into CNN-based vision tasks enables hybrid models to understand global contextual information [28]. Currently, in the agricultural sector, fusion networks of Transformer and CNN (T-CNN) have been applied to fields such as pest and disease classification [29], weed detection [30], and soybean pod counting [31], achieving high prediction accuracy. Furthermore, by employing a self-supervised spectral-spatial attention mechanism, the Transformer network offers a feasible approach for automatically and accurately predicting crop nitrogen status using UAV imagery.

Therefore, the objectives of this study are to (1) conduct in situ field monitoring using multispectral and thermal infrared UAVs, (2) establish a network model that fuses CNN and Transformer architectures (Multi-Hybrid), (3) provide technical support for precision agriculture management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

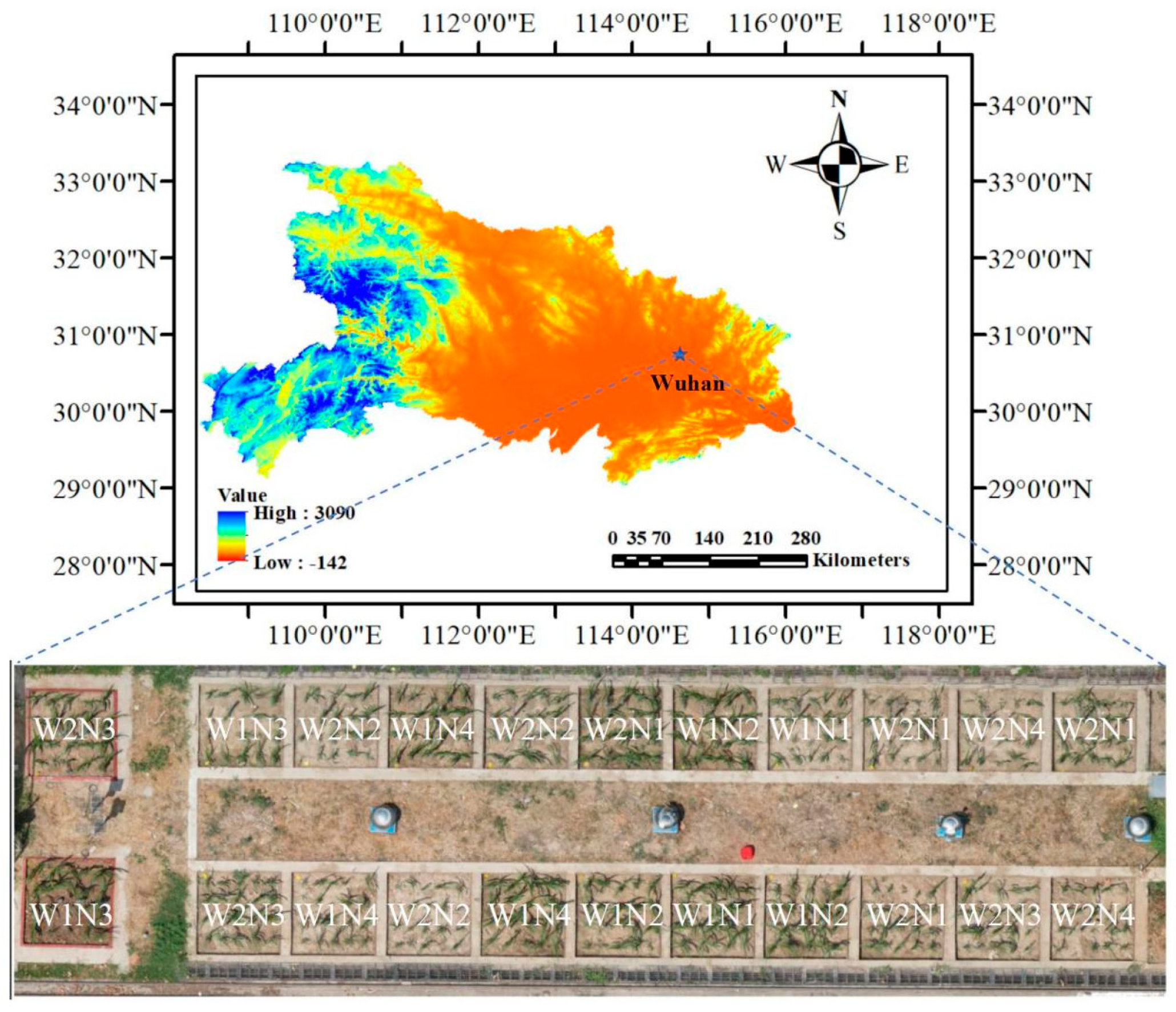

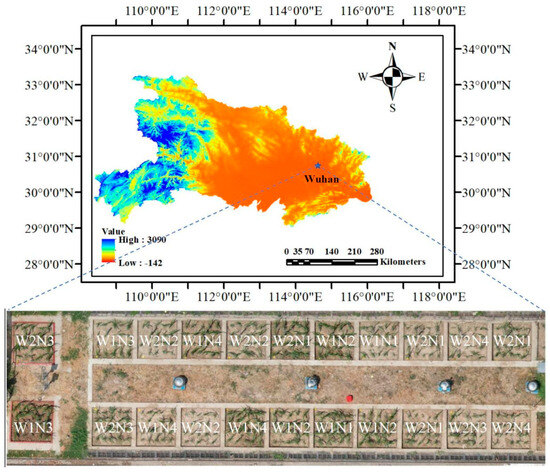

The study was conducted at the Comprehensive Experiment Station for Irrigation, Drainage, and Water Environment of Wuhan University, located in Wuhan City, Hubei Province (Figure 1). Wuhan is situated between 113°41′–115°05′E longitude and 29°58′–31°22′N latitude. The region has a subtropical monsoon (humid) climate with four distinct seasons. The total annual sunshine duration ranges from 1810 to 2100 h, the total annual radiation is between 4350 and 4750 KJ/m2, and the average annual temperature is 15.8 °C to 17.5 °C. The annual precipitation is 1150–1450 mm, with rainfall concentrated from June to August, accounting for approximately 40% of the annual total [32]. The experimental area consisted of 22 test pits at the station. Each pit measured 2.0 m × 2.0 m, with an area of 4 m2, and was equipped with an impermeable base and a rainout shelter. Twenty-five maize plants were planted in each pit, corresponding to a planting density of 6.25 plants/m2. Based on previous research on the effects of water and nitrogen stress on phenology [23,25] a factorial experiment with four nitrogen application levels and two irrigation levels was designed. The four nitrogen application levels were designated as low nitrogen (N1), moderate nitrogen (N2), high nitrogen (N3), and excessive nitrogen (N4) (Table 1). The implementation of these diverse nitrogen and irrigation gradients aims to create a heterogeneous dataset that reflects real-world agricultural complexities. This setup is crucial for evaluating whether the proposed CNN-Transformer architecture can robustly decouple phenological signals from environmental stressors such as water deficiency and nitrogen imbalance [33]. The two irrigation levels were full irrigation (W1) and water deficit (W2), with the irrigation amount for the W2 treatment being 60–70% of that for the W1 treatment (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic map of the study area. W and N denote the water and nitrogen application treatments, respectively.

Table 1.

Nitrogen fertilizer application rates in the field experiment.

Table 2.

The irrigation depth during different growth stages of maize. Only these stages received irrigation as subsequent water requirements were met by local precipitation during the experimental season.

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.2.1. Meteorological and Phenological Monitoring

Meteorological data, specifically ambient temperature for the calculation of growing degree days (GDD), were acquired from an on-site weather station (Shandong Renke Control Technology Co., Ltd., Jinan, China). Commencing in July 2022, in situ phenological assessments of the maize crop were conducted at four-day intervals. Plant developmental stages were classified according to the BBCH (Biologische Bundesanstalt, Bundessortenamt und CHemische Industrie) decimal system, a standardized framework for describing the ontogenetic development of plants [34]. The BBCH, which is a dimensionless quantity. delineates ten principal growth stages, from germination (Stage 0) to senescence and harvest (Stage 8 and 9). For the purposes of this investigation, the phenological progression of maize was monitored and recorded from the emergence of the third leaf (BBCH 13) until physiological maturity (BBCH 89), based on visual inspection of key morphological traits. The phenological stages were categorized based on the extended BBCH scale. The phenological stages were categorized based on the extended BBCH scale. Specifically, this study focused on six key transition stages: jointing (BBCH 30), tasseling (BBCH 51), silking (BBCH 65), blister (BBCH 71), milk (BBCH 75), and physiological maturity (BBCH 89). The transition date for each stage was defined as the day when 50% of the plants in a plot exhibited the corresponding morphological characteristics.

In the BBCH decimal system used here, the transition from BBCH 34 to 35 specifically signifies the development of the fourth to the fifth detectable node during the jointing stage. These numerical increments correspond to measurable morphological changes in stem elongation and biomass accumulation [34] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Field-observed BBCH codes for maize at various growth stages under different water and nitrogen treatments.

2.2.2. UAV Image Acquisition

Spectral imagery was acquired using a MicaSense RedEdge-M multispectral camera. (MicaSense Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) This sensor simultaneously captures grayscale images in five discrete spectral bands: blue (475 nm), green (560 nm), red (668 nm), red-edge (717 nm), and near-infrared (NIR, 840 nm). The camera was mounted on a DJI Matrice 200 (M200) unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), operating at a flight altitude of 50 m. Thermal infrared and RGB images were obtained using a DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), with data collected at a flight altitude of 12 m. The multispectral data acquisition campaign was conducted from 16 July to 29 September, yielding 418 usable images. The RGB and thermal infrared images were captured from 29 July to 29 September, resulting in 220 usable images. The sampling interval for both drone images is 4 days. This temporal coverage was sufficient to monitor the majority of the crop’s growing season. All aerial surveys were performed daily at 14:00. Collecting thermal infrared and multispectral images at noon is optimal due to the sun’s highest elevation angle, which minimizes temporal and lighting variations for consistent, reliable data.

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.3.1. UAV Imagery Preprocessing

The UAV-acquired images were initially processed using Pix4Dmapper (Version 4.5.6) to generate orthomosaic images. To align the spatial scales, the high-resolution thermal imagery was resampled using the Nearest Neighbor (NN) method because it preserves the original spectral digital numbers (DN) and avoids interpolation artifacts, ensuring the integrity of temperature signals for water stress analysis [35]. Subsequently, image registration was performed in ArcMap 10.8. The procedures for image cropping and band fusion were executed using custom scripts in Python 3.9. This workflow resulted in the segmentation of single-band multispectral and thermal infrared orthomosaics into images corresponding to individual experimental plots. The data processing and analysis relied on a comprehensive suite of Python libraries. Key libraries for numerical and geospatial array manipulation included NumPy 1.26.4, GDAL 3.8.5, Rasterio 1.3.10, xarray 2024.6.0, rioxarray 0.15.5, and Dask 2024.6.2. Vector data and geometric operations were handled by GeoPandas 0.14.4, Fiona 1.9.6, Shapely 2.0.4, and PyShp 2.3.1. Core image processing and data analysis tasks were performed using Pillow 10.4.0, Pandas 2.2.2, SciPy 1.14.0, Scikit-image 0.24.0, and OpenCV-Python (cv2) 4.10.0.84, while visualization was accomplished with Matplotlib 3.9.1, Seaborn 0.13.2, and EarthPy 0.9.4.

2.3.2. Meteorological Data Preprocessing

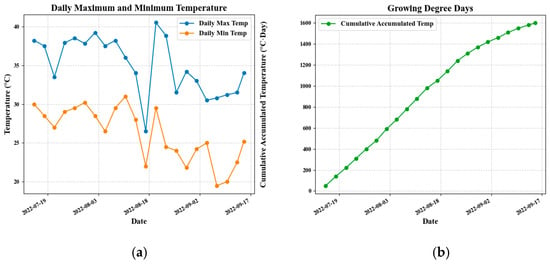

The Growing Degree Days (GDD) were calculated using the following equation:

where Ti represents the cumulative Growing Degree Days (GDD) from sowing to the i-th day (in units of °C·d); Tiavg is the daily average air temperature (°C); Tbase is the base temperature, set at 10 °C.

To generate synchronized training samples, we applied a sliding window averaging method (window size k = 4) to align the daily GDD series with the intermittent UAV sampling dates and ground-truth phenological observations. Spatial samples were generated by segmenting the orthomosaic images into 22 individual plot-level images corresponding to the experimental treatments. The specific formula is as follows:

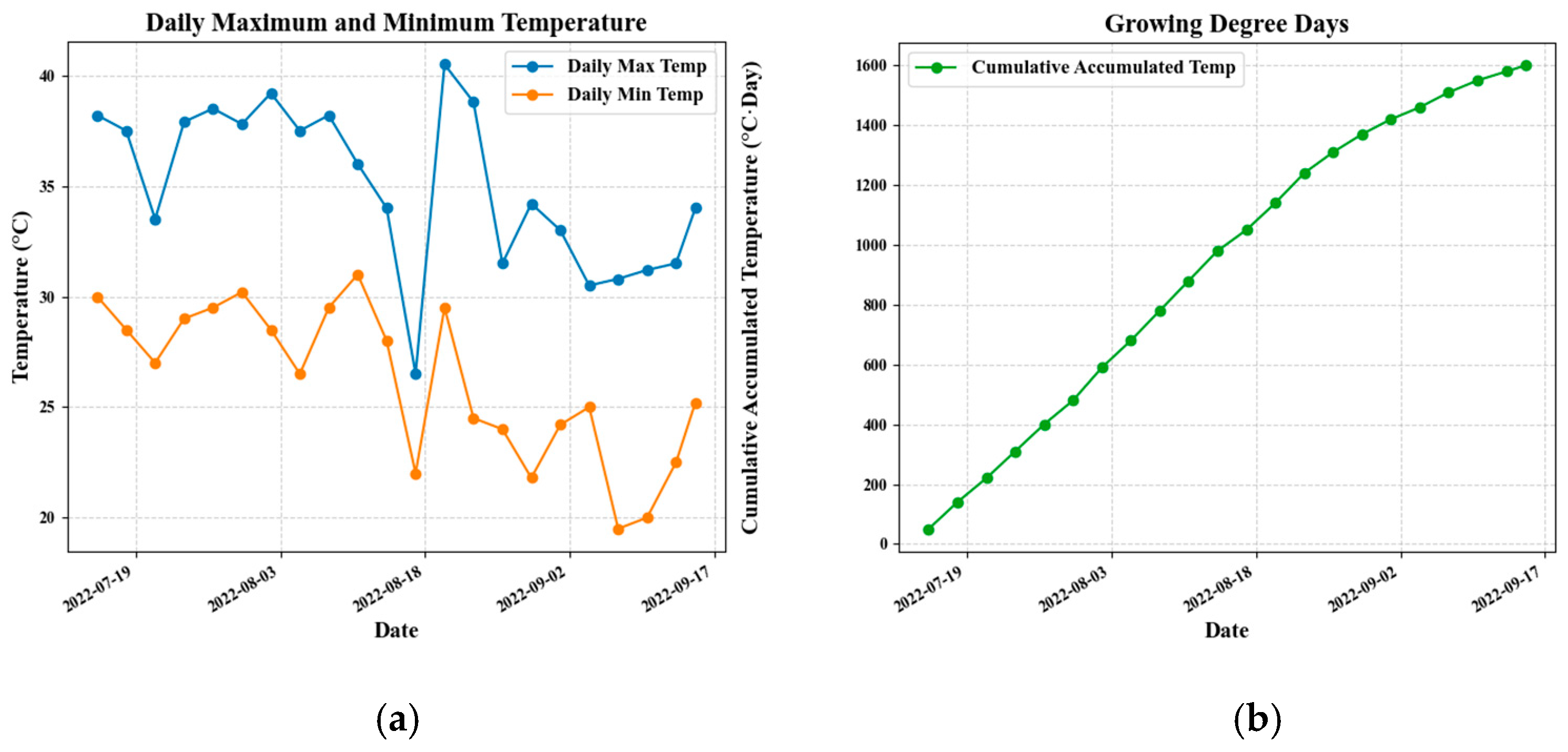

where MAi is the GDD value (°C·d) corresponding to the i-th instance of UAV sampling and phenological observation; xj represents all the GDD values within the sliding window, and k is the window size, set to k = 4. It was specifically chosen to match the four-day interval of the in situ phenological assessments and UAV data acquisition. This ensures that the meteorological inputs are temporally consistent with the temporal resolution of the experimental observations, effectively smoothing daily temperature fluctuations while preserving the cumulative thermal signal relevant to the specific observation cycle. Through this calculation, the accumulation of GDD over the entire maize growth period was determined (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in air temperature (a) and the accumulation of Growing Degree Days (GDD) (b) during the maize experiment period.

2.4. Model Construction

2.4.1. Convolutional Neural Network

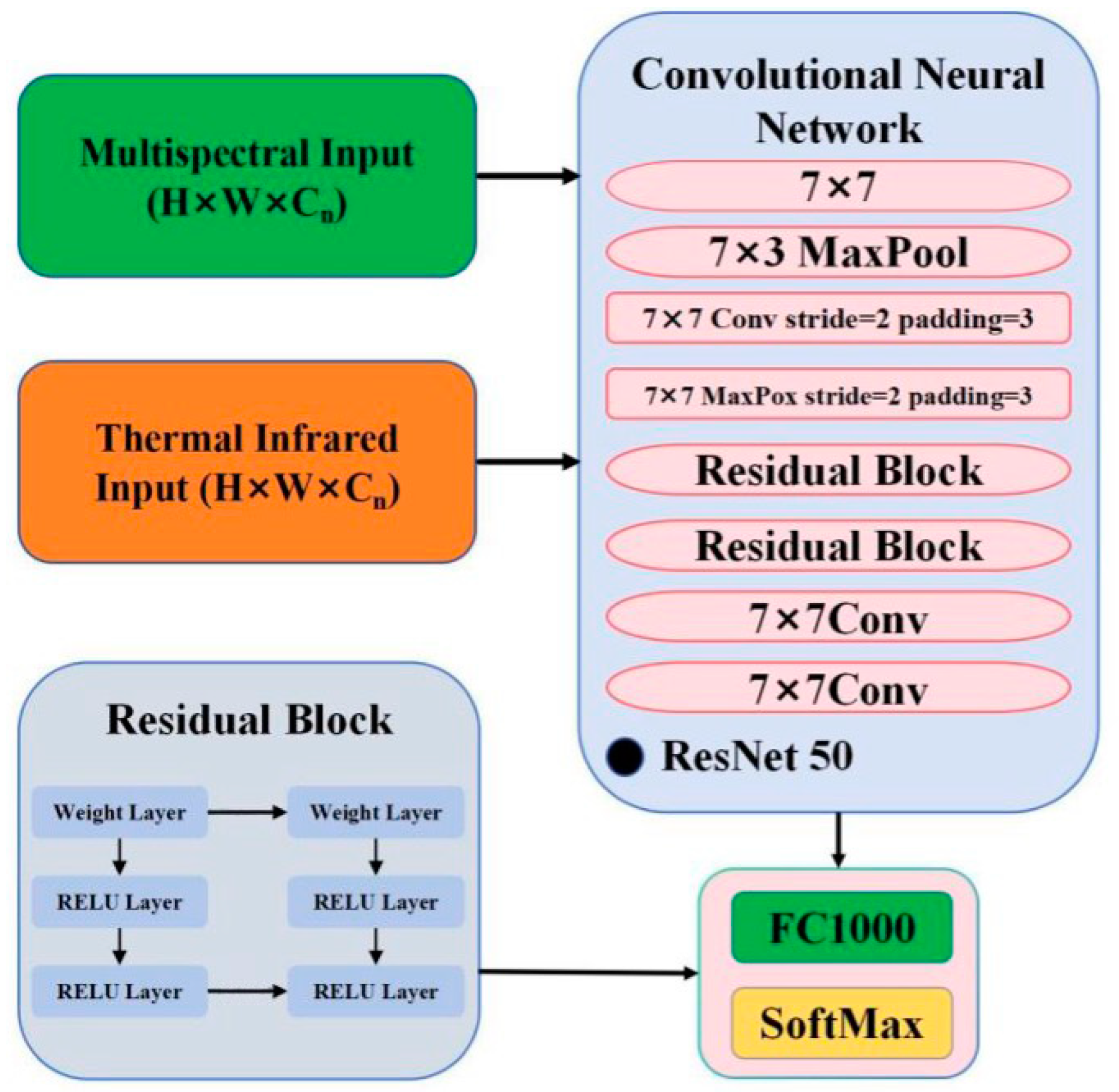

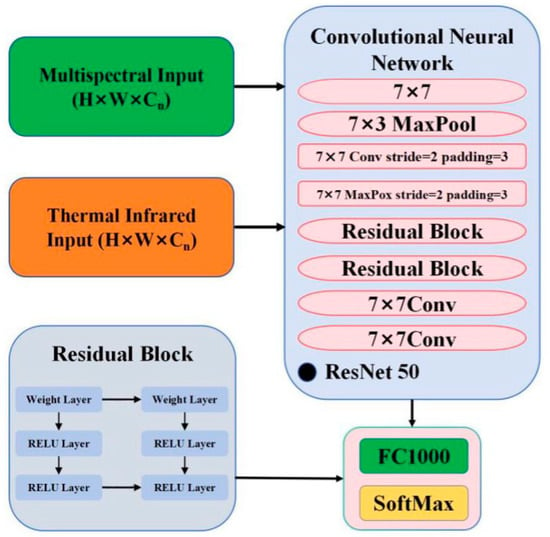

Unlike traditional feature extraction methods, a key advantage of CNNs is that they do not require manual feature engineering [31]. The fundamental components of a CNN include convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully connected layers. A Residual Neural Network (ResNet) introduces the core concept of residual connections (or skip connections). The primary purpose of these connections is to address the problems of exploding and vanishing gradients that arise when training very deep networks, thereby enabling deeper architectures to be trained effectively [36]. Within a Residual Block, the input x is passed through a weight layer followed by a ReLU activation function, and then through another weight layer. The output of this second layer is then added to the original input x, and the sum is passed through a final ReLU activation function. This structure mitigates the gradient problems. The ResNet34 architecture is composed of an initial 7 × 7 convolutional layer and a 3 × 3 max-pooling layer, followed by four stacked layers consisting of a total of 16 residual blocks. The network concludes with another 7 × 7 convolutional layer, a fully connected layer (FC 1000), and a Softmax layer for output (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

CNN Feature Extractor and Residual Block.

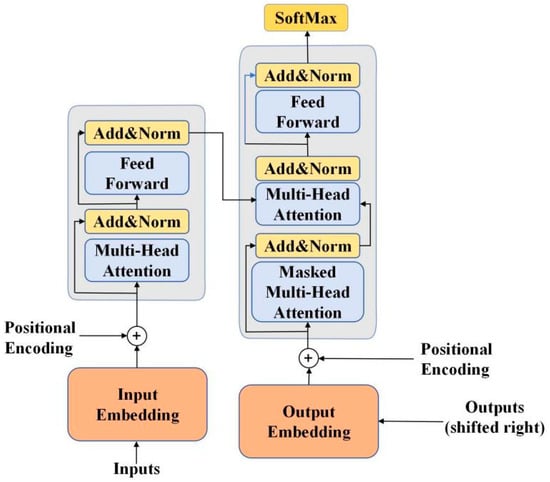

2.4.2. Transformer

The Transformer model is a deep learning architecture designed for Natural Language Processing (NLP) and other sequence transduction tasks [37]. It is composed of multi-head attention layers [38], feed-forward neural networks [39], fully connected layers [40], and normalization layers. The model utilizes a self-attention mechanism to weigh the significance of different parts of the input sequence. By calculating attention weights, the self-attention mechanism allows the model to differentially focus on various positions within the input sequence, enabling it to process all positions simultaneously. The multi-head attention mechanism extends this by introducing multiple attention “heads,” which allows the model to capture relationships across different information scales. The outputs of the multiple attention heads are then concatenated, linearly transformed, and passed as input to the next layer. In the model’s architecture, the input undergoes an input embedding process and is combined with positional encodings before being fed into the Encoder. The Encoder consists of multi-head attention and feed-forward network layers, each followed by a residual connection and layer normalization. The Decoder has a similar structure but incorporates an additional masked multi-head attention layer and takes the right-shifted output sequence as its input. The final output is passed through a linear layer and a Softmax layer to perform prediction or generation tasks (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Transformer Encoder Block.

The three critical elements within the self-attention mechanism are the Query, Key, and Values. The formula for self-attention is as follows:

where KT is the transpose of the Key matrix; dk is the dimension of the Key matrix; headi is the output of the i-th attention head; WO is the weight matrix for the output.

2.4.3. Development of a Fusion Model

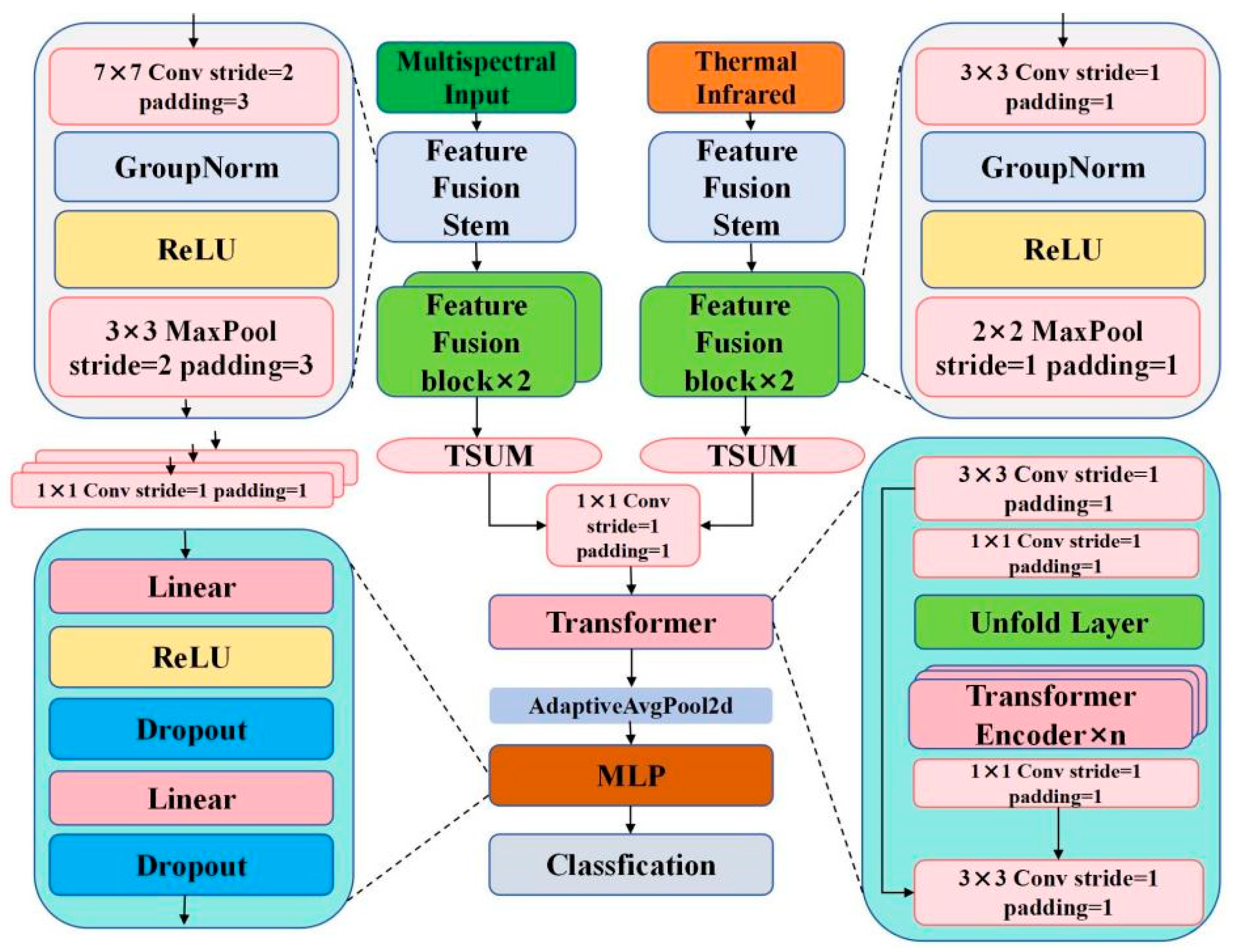

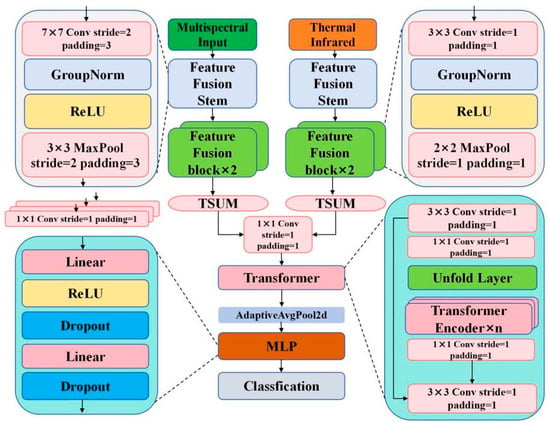

This study builds upon hybrid models by introducing convolutional modules into the Vision Transformer framework [41,42]. We propose a hybrid network based on CNN and Transformer, termed Multi-Hybrid, which is composed of a feature extraction module, a self-attention module, and an MLP module. This network is designed to leverage both the local feature extraction capabilities of CNNs and the global feature acquisition abilities of Transformers, aiming for improvements in accuracy, computational efficiency, and data augmentation capacity [42].

The Multi-Hybrid architecture is designed to reflect the hierarchical nature of maize canopies. First, the CNN backbone is employed for its established maturity in extracting fine-grained, multi-scale features at the leaf and plant levels [43]. This provides essential inductive biases, such as translation invariance, which are critical for processing localized spectral-textural information. Second, considering our specific data scale, this hybrid integration is significantly more data-efficient than pure hierarchical Transformers [44]. It allows the model to converge rapidly while maintaining robustness against environmental noise under water and nitrogen stress.

The backbone of the CNN feature fusion network includes a 7 × 7 convolution (stride 2, padding 3), Group Normalization (GroupNorm), a ReLU activation function, and a 3 × 3 max-pooling layer (window size 3 × 3, stride 2, padding 1). This backbone is used to reduce the spatial dimensions of the image while increasing the feature depth [45]. The Feature Fusion Block employs a 3 × 3 convolution (stride 1, padding 1) and a 2 × 2 max-pooling layer (stride 2, padding 1) to perform feature extraction and halve the spatial dimensions. The Feature Concat module, consisting of three 1 × 1 convolutions, optimizes feature dimensions through weight allocation to mitigate overfitting.

The Transformer module is based on the standard Transformer Encoder and incorporates Layer Normalization (LayerNorm), Dropout, the SiLU activation function, and linear layers. It utilizes Multi-Head Attention to enhance computational efficiency and extract comprehensive information [46,47]. In our model, we have modified the Transformer module by integrating Unfold and Fold operations to reduce the computational load. To further optimize training efficiency, self-attention calculations are not performed within the same patch.

The Unfold operation transforms an input tensor (image or feature map) with a shape of (B, C, H, W) into a tensor with a shape analogous to (B, L, D) or (B, D, L). In this transformation, B represents the batch size, C is the number of input channels, H is the input height, and W is the input width. The resulting sequence has a length L, corresponding to the number of extracted patches, and each flattened patch has a dimension D. This operation is governed by P, the number of padding pixels; K, the sliding window (kernel) size; and S, the stride of the sliding window (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Multi-Hybrid CNN-Transformer Architecture.

The model estimates phenology at the experimental plot level rather than for individual independent pixels. By utilizing CNN to extract localized spectral-textural features from the pixel clusters within a plot and employing Transformer to model global context, the network integrates information from all pixels to infer a representative BBCH value for the entire treatment area.

The dimensions of the output tensor are:

Total number of patches:

The flattened vector for each patch is

where i and j are the starting indices of the sliding window.

where l is the final index of a patch, derived from its vertical and horizontal starting coordinates on the input. The calculation parameters are the input width , padding , kernel size , and stride . This formula maps the 2D spatial coordinates of an image patch to a unique one-dimensional index in a sequence.

The MLP block consists of a fully connected layer, a GELU activation function, and a Dropout layer. The Dropout layer mitigates overfitting by randomly setting the output of a fraction of neurons to zero during training. Key parameters for the Transformer module are shown in the Table 4:

Table 4.

Hyperparameters for the Transformer block.

2.4.4. Hardware Environment

The hardware environment for this study comprised a 7th Generation Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-7500 CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU with 12 GB of VRAM, and 24 GB of system RAM (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The software stack was based on the CUDA 11.9 GPU computing architecture and the PyTorch v1.13.0 deep learning framework, with all code implemented in Python 3.9.

2.4.5. Model Training and Evaluation

In this study, the input variables consisted of multi-modal features: 5-band multispectral imagery (Blue, Green, Red, Red-edge, NIR), Thermal Infrared (TIR) images, and localized Growing Degree Days (GDD). The output variables were categorized into 5 discrete phenological classes based on the BBCH scale, including jointing, tasseling, anthesis, and grain-filling stages. To handle these inputs, the model employed a Cross-Entropy Loss function and the AdamW optimizer.

The dataset was partitioned into a training set, validation set, and test set at a ratio of 6:2:2. For model training, the batch size was set to 32, the number of classes was 5, and the Cross-Entropy Loss function was employed. The learning rate was set to 0.00001, the optimizer was AdamW, and the model was trained for 200 epochs. After training was complete, the model was evaluated on the test set, and the training loss, training accuracy, and test accuracy were reported. For a more targeted analysis, testing was also conducted using multispectral and thermal infrared images from key growth stages. These critical phenological stages included data from 6 August, 27 August, 2 September, and 6 September, which correspond to the jointing and tasseling stages of the maize growth cycle. This specific dataset comprised 88 multispectral images, 88 thermal infrared images, and the corresponding GDD data for those four days.

2.5. Performance Evaluation

2.5.1. Evaluation Metrics

The calculation formula of Accuracy is:

where TP is True Positives representing the model correctly predicts the negative class; TN is True Negatives representing the model correctly predicts the negative class; FP is False Positives representing the model incorrectly predicts the positive class; FN is False Negatives representing he model correctly predicts the negative class.

The calculation formula of Precision is:

The Recall is calculated by the formula:

F1 reflects the model’s ability to balance precision and recall:

2.5.2. Ablation Study

To systematically validate our multimodal deep learning framework for vegetation phenology retrieval, we conducted a comprehensive three-stage ablation study [48]. The first stage focused on an architecture comparison. In this experiment, the Transformer module within our proposed model was replaced by a standard Convolutional Neural Network. The primary objective was to directly compare the performance of our hybrid architecture against a more conventional approach, thereby demonstrating the specific advantages conferred by integrating the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism for processing phenological data.

The second stage involved an input modality analysis to isolate the contributions of different data sources. For this experiment, the Growing Degree Day (GDD) data were deliberately excluded from the model’s input. This allowed us to precisely evaluate the combined impact and synergy of the thermal (TIR) and multispectral (MS) imagery on the model’s retrieval accuracy. This step was crucial for confirming that the fusion of these two remote sensing data types provides a significant performance benefit over models that might rely on a single imaging modality.

To evaluate parameter efficiency of Transformer, we designed a Light Transformer variant. While the original model utilizes 12 Transformer blocks and 12 self-attention heads, the Light Transformer reduces the number of self-attention heads to 8. This comparison allows us to quantify the performance trade-offs associated with model architectural complexity.

3. Results

3.1. Performance of the Multi-Hybrid Model

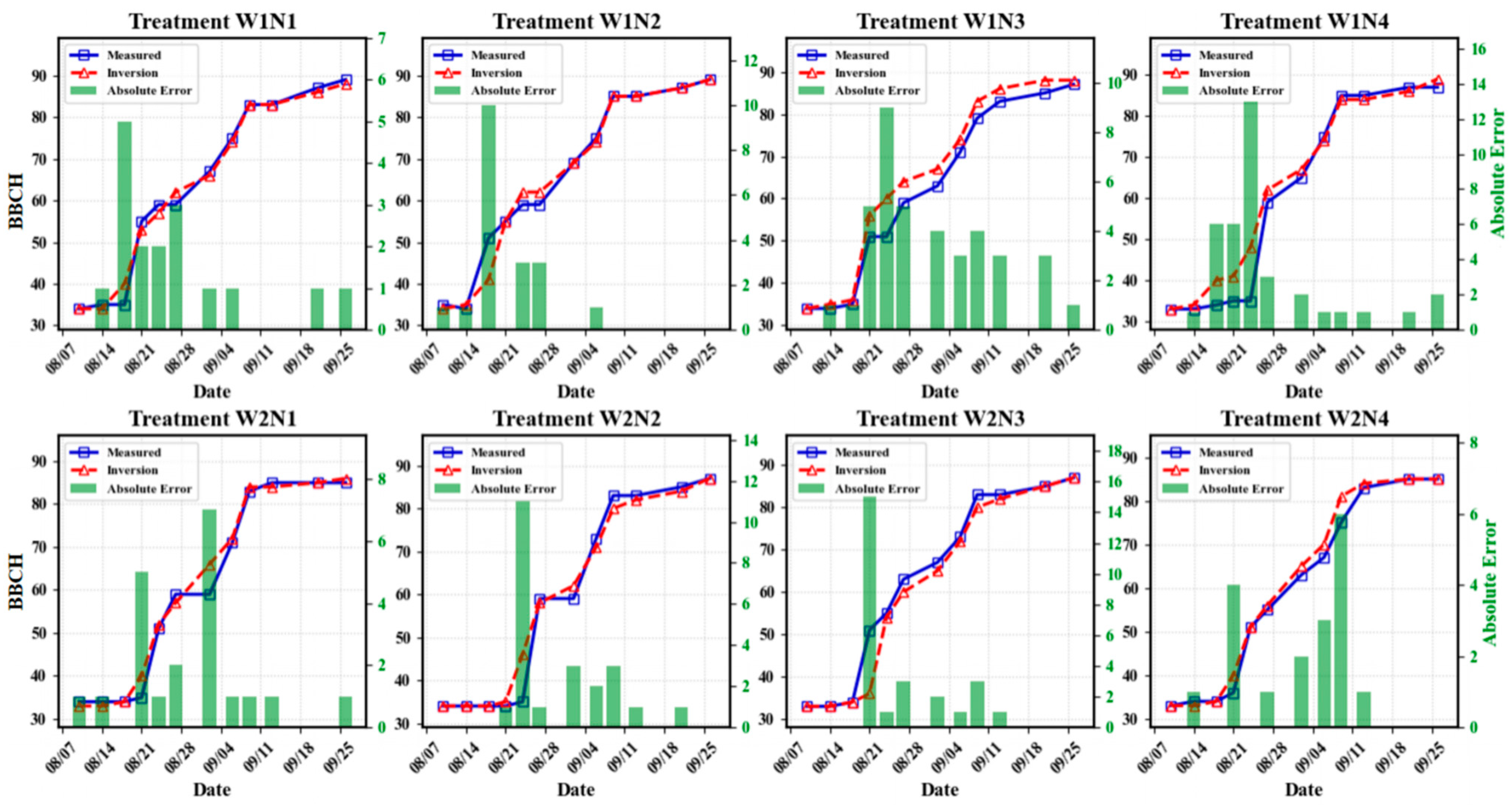

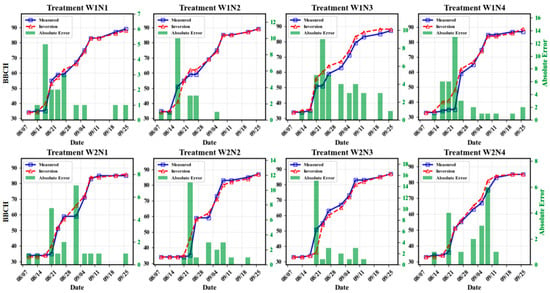

The model accurately tracked phenological progression during the initial jointing (BBCH 34–50) and later reproductive stages (BBCH 63–89) (Table 5). However, a notable discrepancy between predicted and observed values emerged during the rapid development phase from mid-jointing to tasseling (BBCH 51–62), where prediction errors were highest, particularly for the W1N3 and W1N4 treatments (Figure 6). A detailed breakdown of prediction errors (RMSE and MAE) for each treatment and growth stage is provided in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 5.

Model-retrieved BBCH codes for maize at various growth stages under different water and nitrogen treatments.

Figure 6.

Comparison of model-predicted values and field-observed values, along with the corresponding error curve.

Table 6.

Predictive performance of the Multi-Hybrid model for the entire growing season under different nitrogen and water treatments.

Table 7.

Predictive performance of the Multi-Hybrid model at different phenological stages under various nitrogen and water treatments.

When the model was applied to the entire growth period of the crop, the prediction error peaked for the W1N4 treatment and the W2N3 treatment. In contrast, the W2N4 treatment demonstrated the optimal global prediction capability. The model’s retrieval accuracy exhibited the greatest fluctuation during the period from mid-jointing to the pre-grain-filling stage. In this phase, the RMSE ranged from 2.483 (W2N4) to 6.519 (W1N4). Notably, the MAE for W1N4 (5.167) was 104% higher than its average over the entire growth period. Conversely, during the early- to mid-jointing stage, the model’s accuracy improved significantly, with the W2N2 and W2N3 treatments achieving zero error (RMSE = 0, MAE = 0), and the average RMSE across all treatments was only 0.64 ± 0.25. From the mid-to-late grain-filling stage until harvest, the W1N2 treatment had an RMSE and MAE of zero, whereas the W2N4 treatment produced the largest error within this stage (RMSE = 3.041, MAE = 1.75). These results indicate that the model is more sensitive to variations in the nitrogen gradient under the W2 (water-deficit) condition, exhibiting a stronger environmental interaction response, particularly during the reproductive growth phase (grain-filling). This stage-specific fluctuation in accuracy suggests that future crop model development should focus on improving the parameterization of post-anthesis physiological processes. Overall, the model performed optimally under conventional water and fertilizer (W1N1) and water-saving, high-nitrogen (W2N4) treatments.

3.2. Computational Performance of the Multi-Hybrid Model

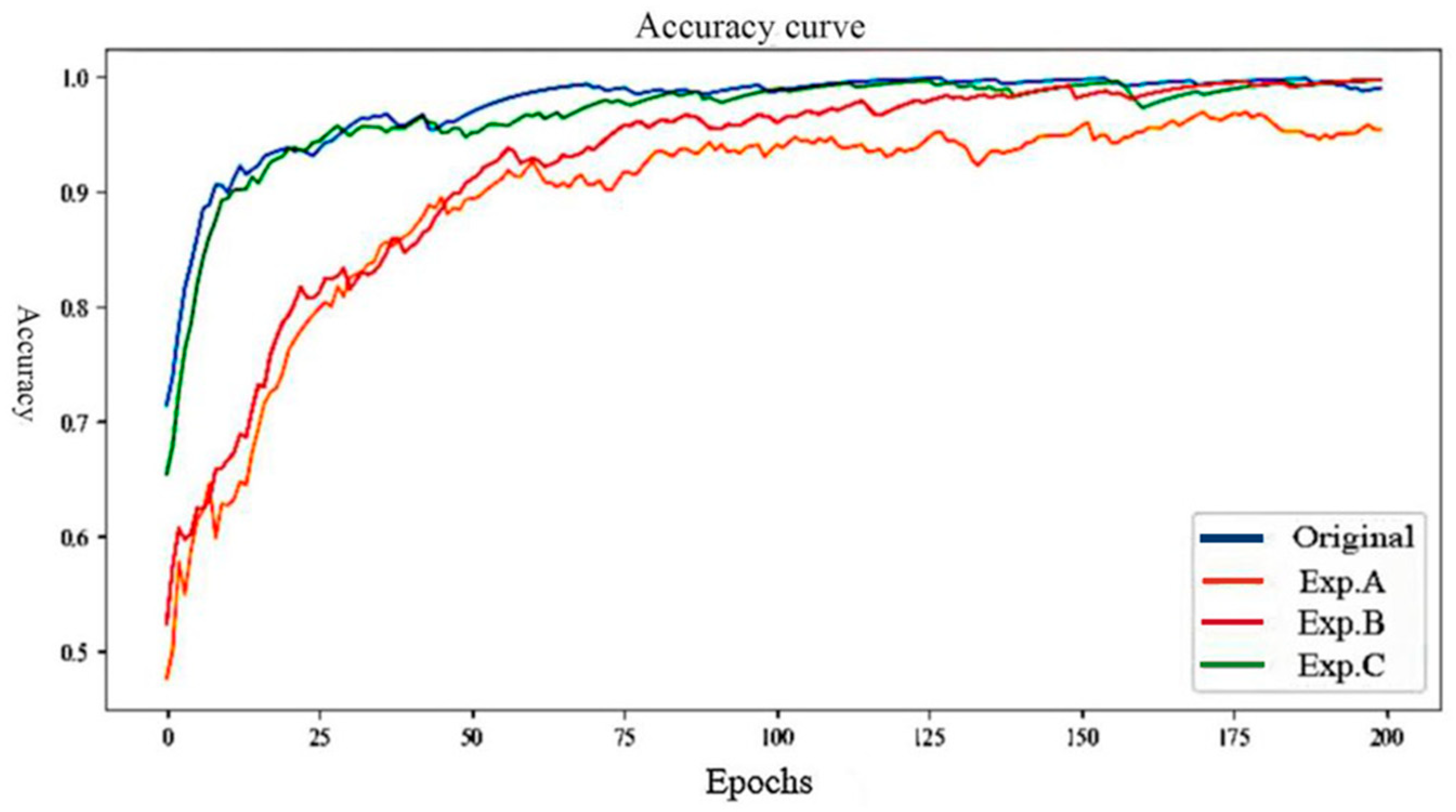

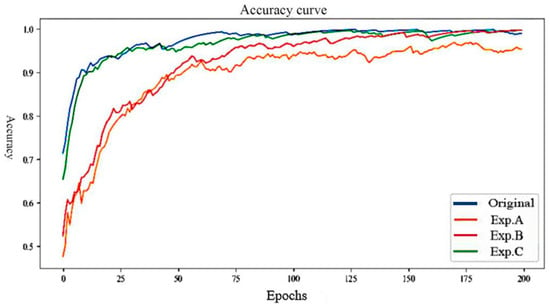

During training, the model achieved a test accuracy of 98.4% within 200 epochs and maintained stable performance over the subsequent 100 iterations (Δacc = 0%). This result validates that the model had fully converged after 200 epochs.

When the number of Transformer blocks was increased from 8 to 12, the single-epoch training time decreased by 8 s (t = 8 s), representing a 14.3% improvement in efficiency. This suggests that moderate module expansion can enhance computational efficiency through parallelization advantages. However, upon further expansion to 16 blocks, the single-epoch training time conversely increased by 4 s (t = +4 s), a 6.7% decrease in efficiency. As model complexity hyperparameters were altered, corresponding changes were observed in both computational cost and prediction accuracy (Figure 7, Table 8).

Figure 7.

Comparison of training accuracy from the ablation study.

Table 8.

Training hyperparameters for the Multi-Hybrid model.

The final Multi-Hybrid model has a parameter count of 35.42 M and achieved an accuracy of 98.4% on the general test set, demonstrating its strong generalization ability and capacity to adapt to diverse data distributions. Its performance on the specific task of identifying key growth stages was also notable, achieving an accuracy of 88.6%, a recall of 97.3%, and an F1-score of 0.887.

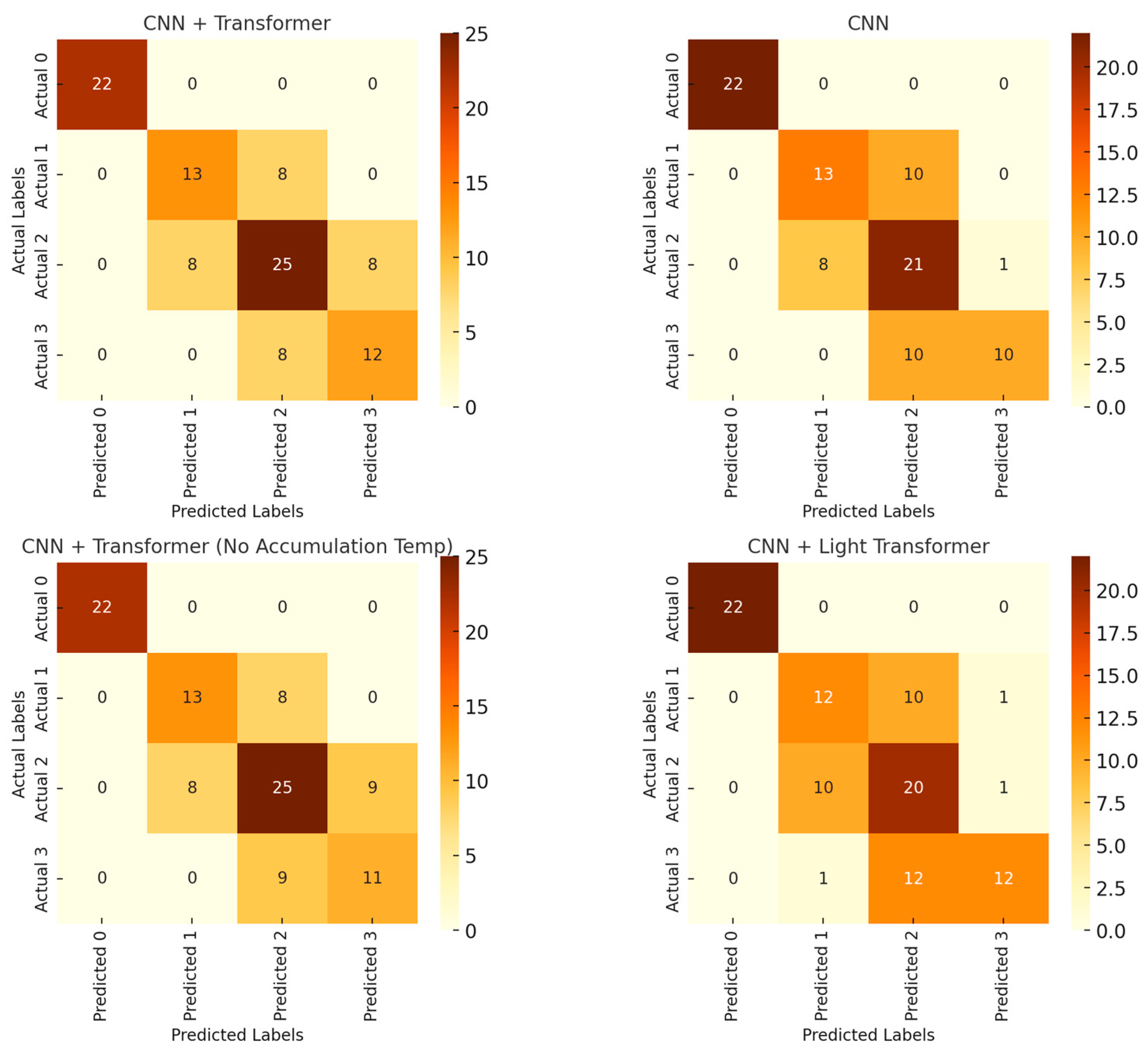

3.3. Performance Validation via the Ablation Study

The full-modality Multi-Hybrid network, which incorporates Thermal Infrared (TIR), Multispectral (MS), and Growing Degree Days (GDD, denoted as AT) data, demonstrated the highest accuracy in the vegetation phenology retrieval task (Figure 7), achieving a 98.4% accuracy. This represents a 12.7 percentage point improvement over the baseline CNN model.

Structural compression experiments revealed that when the number of self-attention heads in the Transformer module was reduced from 12 to 8, the resulting lightweight model (Light Transformer) still maintained a test accuracy of 92.5%. This constituted only a 5.9% relative decline in performance, proving the architecture’s excellent parameter efficiency (Table 8). In the feature modality ablation study, excluding the GDD time-series feature resulted in a dual-modality system (TIR + MS) where the test accuracy dropped to 90.5%. The precision (83.8% ± 1.2%) and recall (82.6% ± 0.9%) of this system showed a statistically significant difference (t-test, p < 0.05) compared to the complete system (84.4% ± 0.8% and 83.9% ± 1.1%, respectively).

This phenomenon confirms that the GDD feature enhances the model’s ability to identify transition points between phenological development stages by quantifying the effects of heat accumulation. Further analysis indicates that the complete Multi-Hybrid network achieves an optimal balance among performance metrics, with an F1-score of 84.15%, which is 0.95 percentage points higher than the dual-modality system (83.20%). Moreover, the proportion of diagonal elements in its confusion matrix (98.4%) was significantly higher than that of other comparative models (Δ > 12.9%).

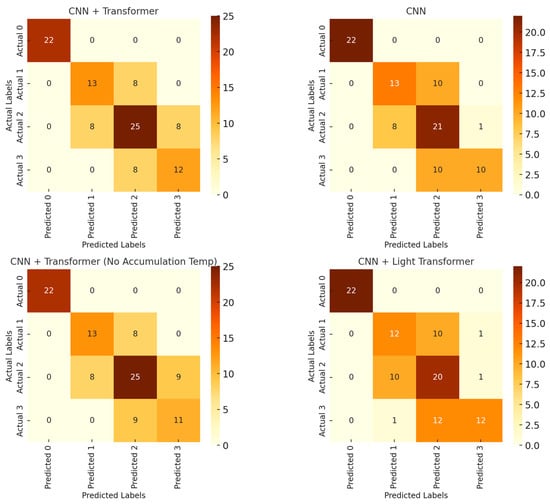

The full CNN + Transformer model demonstrated optimal performance across all evaluation metrics, including a test set accuracy of 98.4% and an F1-score of 0.818. In an ablation study, the CNN + Transformer (No GDD) model, which excluded the GDD feature, achieved an F1-score of 0.805. While slightly lower than the complete model, this performance level remains high. In contrast, the performance of the model using only the CNN component dropped significantly, yielding an F1-score of just 0.604. Furthermore, the CNN + Light Transformer model performed well in terms of test set accuracy (92.5%), but its scores for accuracy, precision and the F1-score (0.75) were slightly lower than those of the full Transformer model (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Confusion matrices from the ablation study. Note: The predicted classes 0–3 correspond to the jointing, tasseling, anthesis (flowering) and grain-filling stages, respectively.

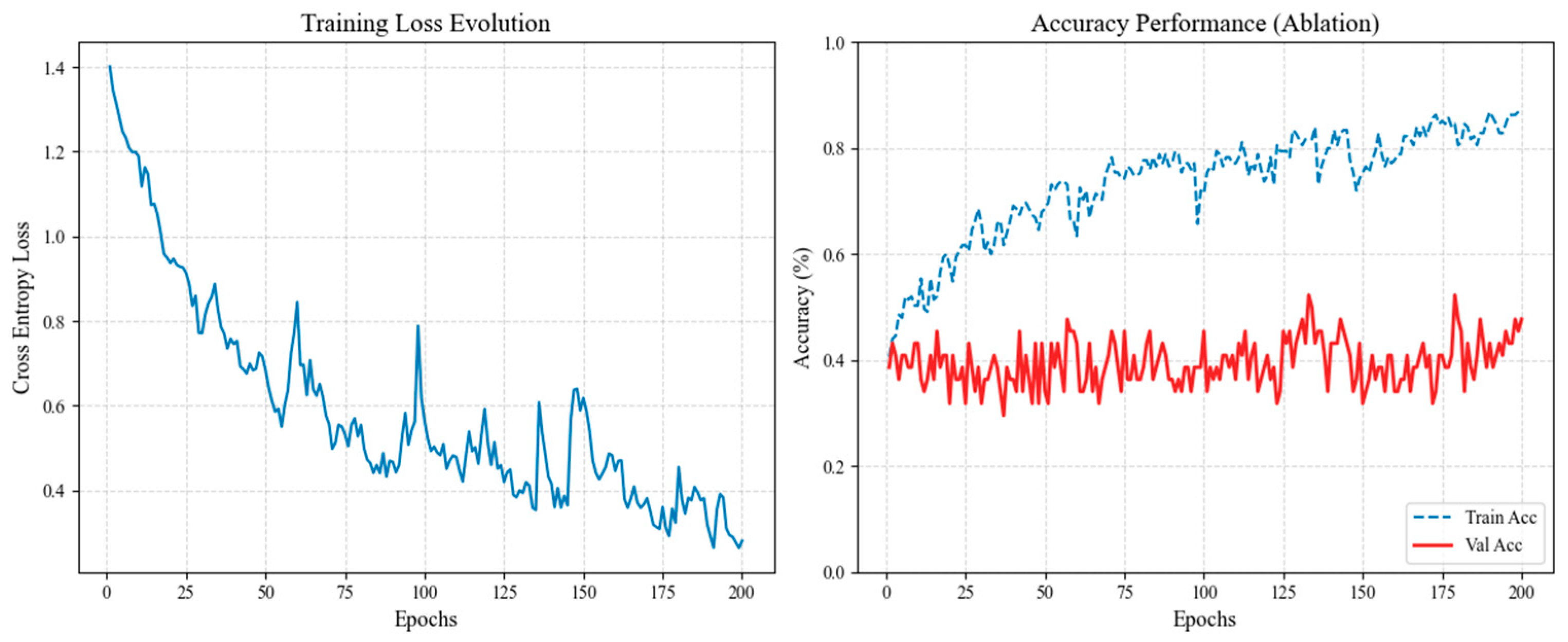

It is noted that the architectural necessity of the hybrid framework was further validated through a standalone Transformer ablation study (Exp D). The standalone model suffered from severe overfitting and convergence instability, reaching a training accuracy of 84.73% but failing to generalize, with a validation accuracy of only 47.73%. This stark performance gap underscores that standalone attention mechanisms, when applied to localized agricultural imagery at this data scale, tend to capture idiosyncratic noise rather than robust phenological signals. In contrast, our Multi-Hybrid model avoids such pitfalls by leveraging CNNs to provide essential inductive spatial biases, resulting in a significantly more stable and accurate (98.4%) monitoring performance under complex field conditions (Figure 9, Table 9).

Figure 9.

Ablation study results for the standalone Transformer without CNN backbone.

Table 9.

Results of the ablation study.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Water and Nitrogen on Crop Phenology and Model Retrieval Performance

Under conditions of high water supply (W2), the model’s retrieval error during the mid-jointing stage (BBCH 51-62) with an RMSE range of 0.447–0.894 was significantly lower than that of the low-water treatment (W1) during the corresponding stage (RMSE range: 2.708–6.519). This suggests that sufficient water enhances the identifiability of spectral features by stabilizing the crop’s physiological activity, thereby improving the model’s retrieval accuracy. Under excessive nitrogen conditions (N3, N4), the model’s prediction error for the tasseling to grain-filling stage (BBCH 63-89) increased significantly (W2N3: RMSE = 6.364). The suboptimal performance under high nitrogen treatments (W1N3, W1N4, W2N3) is primarily driven by two synergistic factors. First, high nitrogen levels (N3, N4) significantly elevate chlorophyll concentrations. This saturation effect increases light absorption in the visible and red-edge spectral regions, which introduces spectral interference and reduces the stability of phenological feature extraction. Second, high nitrogen promotes rapid biomass accumulation and canopy closure [49]. Canopy closure, is particularly common in densely planted, broad-leaf crops like maize. Canopy closure has a significant impact on ecosystem functions, micro-environmental conditions, and remote sensing monitoring [50,51]. It is noteworthy that canopy closure induced by high nitrogen levels can exacerbate micro-environmental heterogeneity [52], leading to increased noise in remote sensing data. This structural density exacerbates micro-environmental heterogeneity within the canopy, generating significant structural noise in the UAV-acquired multispectral and thermal data. Since the current Multi-Hybrid model does not explicitly incorporate a specific denoising module for canopy shadows or structural overlaps, the increased noise directly led to higher RMSE and MAE values—peaking at 4.2 for W1N4—during the mid-jointing to grain-filling transition. Therefore, nitrogen regulation influences model prediction accuracy not only by altering spectral characteristics but also by indirectly affecting chlorophyll content. Therefore, in the 9-day period following tasseling and prior to grain-filling, the model’s prediction accuracy was lower compared to the early- to mid-jointing and mid-to-late grain-filling periods, with particularly significant errors observed for the W1N3, W1N4, and W2N3 treatments.

An analysis of the confusion matrix reveals that the highest misclassification rates occurred between the tasseling and anthesis stages. This phenomenon can be theoretically explained by the biological continuity of these two phases, which typically transition within a narrow window of 3 to 5 days. Spectrally, the morphological shift from a fully emerged tassel to the onset of pollen shedding is subtle compared to the dramatic biomass increases observed during the vegetative-to-reproductive transition. Consequently, the multispectral and thermal signatures of these two stages exhibit significant overlap.

4.2. Simulation Performance of the Multi-Hybrid Network Model

Quantitative comparison reveals that the proposed Multi-Hybrid model (98.4% accuracy) not only outperforms the self-constructed pure CNN baseline (85.7%) but also significantly exceeds other convolutional frameworks reported in the literature, such as the 91.2% accuracy achieved in similar rice phenology studies. Compared to the substantial prediction errors of traditional curve-fitting methods under environmental stress—which often range from 3 to 8 days—our model maintains higher precision and robustness across complex water-nitrogen scenarios. This validates the superior performance of hybrid architectures in capturing non-linear phenological responses, providing a more reliable tool for precision agriculture than traditional parametric approaches [10]. The introduced residual network structure successfully addresses the performance degradation issue that can occur in traditional neural networks as their depth increases, through the design of “residual blocks” [53]. These blocks facilitate more effective gradient propagation during backpropagation, mitigating the problems of vanishing or exploding gradients and allowing for more stable training of deeper networks. In terms of operational speed, the incorporated Unfold and Fold modules enhance the flexibility and efficiency of tensor operations, enabling the model to perform data transformation and feature extraction more rapidly and thus accelerating the overall training process [54]. Concurrently, the LayerNorm within the model not only improves the performance of the multi-head attention layers but also stabilizes the training process, allowing the model to converge in fewer iterations [27].

CNNs have limitations in processing long-range dependencies [48]. The Multi-Hybrid model integrates a Transformer module with the CNN. This combination leverages the strengths of CNNs in local feature extraction and the capability of Transformers in capturing long-range dependencies, achieving a more comprehensive understanding of the image information. This mechanism captures more holistic and complex feature information by dynamically adjusting the degree of attention paid to different features based on the calculated similarity between each element and all other elements in the sequence [37]. Additionally, the LayerNorm normalization technique within the Transformer stabilizes the training process, enhances the expressive power of the multi-head attention layers, and improves the model’s robustness and accuracy when processing multi-source data [55].

In terms of architectural rationality, the synergy between CNN and Transformer addresses the diverse spatial scales of agricultural remote sensing. While hierarchical Transformers like Swin use window-based attention for efficiency, our model preserves a global receptive field through its Transformer module. This is vital for maize phenology monitoring, where identifying synchronized transitions across a population requires a holistic scene understanding. The experimental results, achieving 98.4% accuracy, validate that our specific combination of localized CNN feature extraction and global Transformer attention is compatible with the requirements of precision agriculture management.

In the ablation study, removing the Transformer module led to a significant decrease in model accuracy. This finding underscores the critical role of the Transformer module in capturing long-range dependencies within the images, a task for which CNNs are limited by their local receptive fields. Through its self-attention mechanism, the Transformer effectively models these long-range relationships, enhancing the model’s ability to comprehend global image information and thereby improving its predictive accuracy.

Reducing the number of Transformer blocks resulted in a progressive degradation of model performance, which can be attributed to the shortening of information pathways and the interruption of gradient flow [17]. Conversely, when the number of Transformer blocks was increased from 8 to 12, both the model’s computational speed and its accuracy improved. This can be explained by several factors. First, the computations within the Transformer architecture can effectively leverage the inherent vectorization properties of the softmax function, leading to higher hardware utilization [56]. Second, the multiple layers in a Transformer can enhance efficiency by decomposing tasks and executing them concurrently [57]. Although adding more layers increases the model’s overall computational load, the self-attention mechanism and feed-forward networks are designed in a way that optimizes hardware efficiency.

Although the proposed model achieved a remarkable predictive accuracy of 98.4%, certain inherent limitations warrant further consideration. The current framework relies on a linear Growing Degree Days (GDD) approach, which operates under the assumption of a constant rate of development above a base temperature. However, this simplification may fail to capture the non-linear physiological responses of plants to extreme thermal conditions, particularly near the upper critical thresholds [58]. In biological systems, heat sensitivity often exhibits a parabolic or sigmoidal trend where developmental rates plateau or decline beyond an optimal temperature [59]. Future iterations could integrate Beta functions to better simulate these non-linear dynamics, thereby enhancing the model’s robustness under diverse climatic scenarios and heat stress conditions.

Additionally, as validation was restricted to a single year and site, future research will utilize transfer learning and domain adaptation to improve robustness across diverse climates and regions. Furthermore, this study focused on a single cultivar, whereas maize durations vary significantly (90–120 days) among varieties. Although our stress treatments induced some phenological shifts, they do not represent the full range of genetic diversity. Future research should incorporate multi-cultivar datasets to develop cultivar-agnostic models to ensure broader reliability across diverse agricultural seed types.

4.3. Effect of Source Dataset Type on Model Retrieval Performance

Previous research has demonstrated that a CNN model designed using UAV-based RGB imagery can achieve a retrieval accuracy of 83.9% [60]. Beyond RGB retrieval, multispectral imaging analysis is becoming an increasingly popular tool for high-throughput plant phenotyping. For instance, a prior study proposed a CNN-based crop classification method that utilized the 12 spectral bands from Sentinel-2 satellite imagery as an input source, integrating the spectral data into a simplified synthetic matrix to reduce computational complexity [61]. This work suggests the feasibility of using multispectral image data acquired from UAVs as an input source for predicting phenology.

In multimodal data input, the diversification of image data sources is more beneficial for improving model performance. This is because image data are inherently high-dimensional [62], containing a vast amount of spatial, textural, color, and shape features, which are fundamental for the model to complete visual tasks [52]. By acquiring image data from multiple sources, the model can learn a greater number of visual features relevant to the target task, thereby enhancing the performance of classification, detection, or segmentation. In contrast, data like GDD can be considered a linear sequence, whose information density is far less rich than that of image data. Consequently, the GDD data did not make a significant contribution to the model’s performance.

The interpretability of deep learning models is essential for aligning algorithmic predictions with the biological mechanisms of crop growth. In this study, while visual saliency methods like Grad-CAM provide intuitive insights, their application to multi-modal phenology monitoring is constrained by specific data and architectural limitations. The input features include five multispectral bands and two thermal channels, many of which (e.g., NIR, Red-edge, and TIR) are beyond the visible spectrum. Overlaying attention weights derived from these non-visible signatures onto standard RGB backgrounds often results in poor visualization quality and potential misinterpretation of the model’s focus. Furthermore, the Multi-Hybrid model generates final decision-level feature maps at a significantly reduced spatial scale (e.g., 7 × 7) compared to the input resolution. Consequently, upsampling these maps onto TIF inputs with inherent resolution constraints results in coarse heatmaps that lack the precision to distinguish fine-grained morphological traits.

5. Conclusions

This study developed and validated Multi-Hybrid, a novel deep learning model that fuses a Convolutional Neural Network with a Vision Transformer to accurately monitor maize phenology. By leveraging multi-source UAV data, including multispectral and thermal infrared imagery, the model effectively captures both local and global features, leading to robust performance under varying water and nitrogen stress conditions. The CNN + Transformer architecture achieved a test accuracy of 98.4% with the full modality input (TIR + MS + GDD), demonstrating its potential to provide critical technical support for precision agriculture management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z.; methodology, Y.G.; validation, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and Y.L.; visualization, H.Z. and C.A.; supervision, W.Z.; funding acquisition, W.Z. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (52379045) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. B240201076).

Data Availability Statement

The Multi-Hybrid code, BBCH dataset and other observed data are publicly available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/vfvv9dv6fp/1 (accessed on 17 January 2026). It serves as a zip file.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the constructive comments and suggestions of the anonymous reviewers, which have greatly helped to improve this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Chao, Y.; Song, G.; Nie, C.; Wang, L. Response of Different Varieties of Maize to Nitrogen Stress and Diagnosis of Leaf Nitrogen Using Hyperspectral Data. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogola, J.; Wheeler, T.; Harris, P. Effects of Nitrogen and Irrigation on Water Use of Maize Crops. Field Crops Res. 2002, 78, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Dugo, V.; Durand, J.-L.; Gastal, F. Water Deficit and Nitrogen Nutrition of Crops. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celette, F.; Gary, C. Dynamics of Water and Nitrogen Stress along the Grapevine Cycle As Affected by Cover Cropping. Eur. J. Agron. 2012, 45, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.R.; Rufty, T.W. Nitrogen and Water Resources Commonly Limit Crop Yield Increases, Not Necessarily Plant Genetics. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Santiago-Arenas, R.; Ferdous, Z.; Attia, A.; Datta, A. Improving water use efficiency, nitrogen use efficiency, and radiation use efficiency in field crops under drought stress: A review. Adv. Agron. 2019, 156, 109–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, C.; Yang, G.; Ren, P.; Ma, Y.; Chen, W.; Feng, H.; Chen, R.; Chen, X.; Li, H. Identification of the Initial Anthesis of Soybean Varieties Based on UAV Multispectral Time-Series Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, A.; Keatinge, J.; Wheeler, T.; Papastylianou, I.; Subedi, M.; Shah, P.; Musitwa, F.; Cespedes, E.; Bening, C.; Ellis, R.; et al. Validation of a Photothermal Phenology Model for Predicting Dates of Flowering and Maturity in Legume Cover Crops Using Field Observations. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2000, 17, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero-Belinchon, C.; Adeline, K.; Lemonsu, A.; Briottet, X. Phenological Dynamics Characterization of Alignment Trees with Sentinel-2 Imagery: A Vegetation Indices Time Series Reconstruction Methodology Adapted to Urban Areas. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhu, W.; Atzberger, C.; Liu, Q. The Optimal Threshold and Vegetation Index Time Series for Retrieving Crop Phenology Based on a Modified Dynamic Threshold Method. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.; Sorensen, I.; Jamieson, P. Effect of Soil Temperature on Phenology, Canopy Development, Biomass and Yield of Maize in a Cool-Temperate Climate. Field Crops Res. 1999, 63, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Yong, L.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Sang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, H. Infiltration Process of Irrigation Water in Oasis Farmland and Its Enlightenment to Optimization of Irrigation Mode: Based on Stable Isotope Data. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 258, 107173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, G. A Novel Method for Identifying Crops in Parcels Constrained by Environmental Factors Through the Integration of a Gaofen-2 High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image and Sentinel-2 Time Series. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, S.; Woodcock, C.E. Improvement and Expansion of the Fmask Algorithm: Cloud, Cloud Shadow, and Snow Detection for Landsats 4–7, 8, and Sentinel 2 Images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 159, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, D.P.K.; Devi, N.; K, L.; Narne, C. Evaluation of Grain Quality Traits in Popular Rice Varieties of Andhra Pradesh. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2021, 10, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoglu, G.; Demirel, K.; Genc, L. Use of Infrared Thermography and Hyperspectral Data to Detect Effects of Water Stress on Pepper. Quant. InfraRed Thermogr. 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lu, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, Z.; Gu, G. Gradient Aggregation Based Fine-Grained Image Retrieval: A Unified Viewpoint for CNN and Transformer. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 149, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werema, C.W.; Yang, D.A.; Laven, L.J.; Mueller, K.R.; Laven, R.A. Evaluating Alternatives to Locomotion Scoring for Lameness Detection in Pasture-Based Dairy Cows in New Zealand: Infra-Red Thermography. Animals 2021, 11, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Dong, X.; Wu, Z.; Wei, C.; Li, L.; Yu, D.; Fan, X.; Ma, Y. Using Infrared Thermal Imaging Technology to Estimate the Transpiration Rate of Citrus Trees and Evaluate Plant Water Status. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garajeh, M.K.; Salmani, B.; Naghadehi, S.Z.; Goodarzi, H.V.; Khasraei, A. An Integrated Approach of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Analysis for Modeling and Predicting the Impacts of Climate Change on Food Security. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thao, N.T.T.; Khoi, D.N.; Denis, A.; Viet, L.V.; Wellens, J.; Tychon, B. Early Prediction of Coffee Yield in the Central Highlands of Vietnam Using a Statistical Approach and Satellite Remote Sensing Vegetation Biophysical Variables. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, S.S.; Scobie, M.; Baillie, J.; Plant, C.; Shammi, S.; Das, A. Integrating UAV-based Multispectral and Thermal Infrared Imageries with Machine Learning for Predicting Water Stress in Winter Wheat. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Cao, H.; Wang, H.; Pan, X. The Physiological Responses of Tomato to Water Stress and Re-Water in Different Growth Periods. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, Z.; Ullah, I.; Chen, S. Effect of Two Types of Irrigation on Growth, Yield and Water Productivity of Maize under Different Irrigation Treatments in an Arid Environment. Irrig. Drain. 2020, 69, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tang, Y. Responses of Plant Phenology to Nitrogen Addition: A Meta-analysis. Oikos 2019, 128, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, X.; Cui, Y.; Wu, J. Transformer-Based Fused Attention Combined with CNNs for Image Classification. Neural Process. Lett. 2023, 55, 11905–11919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucudean, G.; Bucos, M.; Dragulescu, B.; Caleanu, C.D. Natural Language Processing with Transformers: A Review. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Seo, S.-W. Discrete Wavelet Transform Meets Transformer: Unleashing the Full Potential of the Transformer for Visual Recognition. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102430–102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padshetty, S.; Umashetty, A. Agricultural Innovation Through Deep Learning: A Hybrid CNN-Transformer Architecture for Crop Disease Classification. J. Spat. Sci. 2024, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, R.; Du, J.; Chen, T. SWFormer: A Scale-Wise Hybrid CNN-Transformer Network for Multi-Classes Weed Segmentation. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 6999–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, C.-Y.; Qu, W.-Y.; Li, W.-Z. Passive Design Strategies Based on Climatic Characteristics in Hot-Summer and Cold-Winter Zone: Taking Wuhan City for Example. Build. Energy Effic. 2013, 4, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yin, W.; Fan, H.; Fan, Z.; Hu, F.; Yu, A.; Zhao, C.; Chai, Q.; Aziiba, E.A.; Zhang, X. Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Water and Nitrogen Coupling for Enhanced High-Density Tolerance and Increased Yield of Maize in Arid Irrigation Regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 726568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancashire, P.; Bleiholder, H.; Vandenboom, T.; Langeluddeke, P.; Stauss, R.; Weber, E.; Witzenberger, A. A Uniform Decimal Code for Growth Stages of Crops and Weeds. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1991, 119, 561–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra-Serrano, I.; Pena, J.M.; Torres-Sanchez, J.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F.J.; Lopez-Granados, F. Spatial Quality Evaluation of Resampled Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Imagery for Weed Mapping. Sensors 2015, 15, 19688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.-M.; Zhang, B.-K.; Guo, W.; Ma, X.-S. Analysis of Low C/N Wastewater Treatment and Structure by the CEM-UF Combined Membrane-Nitrification/Denitrification System. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2018, 39, 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, S.; Fang, Y. Object Detection Algorithm Based On Multiheaded Attention. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayian, M.; Niknam, V.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Oxidative Damage and Antioxidative System in Algae. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basha, S.H.S.; Dubey, S.R.; Pulabaigari, V.; Mukherjee, S. Impact of Fully Connected Layers on Performance of Convolutional Neural Networks for Image Classification. Neurocomputing 2020, 378, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xiao, B.; Codella, N.; Liu, M.; Dai, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L. CvT: Introducing Convolutions to Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jegou, H. Training Data-Efficient Image Transformers & Distillation Through Attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; Volume 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Iqbal, I.; Bhatti, U.A.; Liu, J.; Awwad, E.M.; Sarhan, N. ResNet50 in Remote Sensing and Agriculture: Evaluating Image Captioning Performance for High Spectral Data. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tan, Z.; Lv, Q.; Li, J.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Y. An Efficient Hybrid CNN-Transformer Approach for Remote Sensing Super-Resolution. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, D.E.; Iakovidis, D.K. Fuzzy Pooling. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 29, 3481–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, J.; Sun, Q.; Liu, K.; Yang, X.; Zhang, F. Multi-head Multi-Order Graph Attention Networks. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 8092–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Zhang, H.; DeJonge, K.C.; Comas, L.H.; Trout, T.J. Estimating Maize Water Stress by Standard Deviation of Canopy Temperature in Thermal Imagery. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 177, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, S.; Zhou, G. Joint Data Association, Spatiotemporal Bias Compensation and Fusion for Multisensor Multitarget Tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 1509–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.; Ganesh, P.; Saisravan, A.; Dawson, J. Effect of Nitrogen and Iron Levels on Growth and Yield of Rabi Hybrid Maize (Zea mays L.). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 2297–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S.; Ansari, S.A.; Ansari, M.I.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species: Generation, Signaling, and Defense Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Cao, W.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ni, J. Spectrum- and RGB-D-Based Image Fusion for the Prediction of Nitrogen Accumulation in Wheat. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, S.-Y.; Kong, L.-Y.; Chen, G.-J. Seasonal Variations and Driving Factors of Phytoplankton Community Shift in Datun Lake with Long-Term Stress of Arsenic Contamination. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 1845–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tang, H.; Pan, G. Spiking Deep Residual Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 5200–5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yuan, M.; Yan, D.M.; Wu, T. Deep Unfolding Multi-Scale Regularizer Network for Image Denoising. Comput. Vis. Media 2023, 9, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Huo, X.; Qian, L.; Du, Y.; Liu, D.; Cao, Q.; Wang, W.E.; Hu, X.; Yang, X.; Fan, S. Combining UAV Multispectral and Thermal Infrared Data for Maize Growth Parameter Estimation. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltekis, C.; Alexandridis, K.; Dimitrakopoulos, G. Reusing Softmax Hardware Unit for GELU Computation in Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on AI Circuits and Systems, AICAS 2024, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 22–25 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, A.H.N.; Qiu, J.; Zhao, Z. Tigr: Transforming Irregular Graphs for GPU-Friendly Graph Processing. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Williamsburg, VA, USA, 24–28 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.Y.; Oh, M.-M.; Son, J.E. Modeling Approaches for Estimating Cardinal Temperatures by Bilinear, Parabolic, and Beta Distribution Functions. Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2009, 27, 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, S.S.; Kafi, M.; Nezami, A.; Aval, M.B. Evaluation of base, optimum and ceiling temperature for (Kochia scoparia L. schard) with application of five-parameters-beta model. J. Agroecol. 2011, 3, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Fan, Y.; Li, B. Research on dimensionality reduction and classification of hyperspectral images based on LDA and ELM. J. Electron. Meas. Instrum. 2020, 34, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siesto, G.; Fernandez-Sellers, M.; Lozano-Tello, A. Crop Classification of Satellite Imagery Using Synthetic Multitemporal and Multispectral Images in Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Shi, L.; Han, J.; Yu, J.; Huang, K. A Near Real-Time Deep Learning Approach for Detecting Rice Phenology Based on UAV Images. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 287, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.