Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A two-stage, parameter-efficient fine-tuning framework with hierarchical prompting is proposed to adapt Qwen3-VL for few-shot object detection in remote sensing imagery. It substantially improves novel-class mAP while largely preserving base-class performance on the DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2 datasets.

- A three-level hierarchical prompting scheme—comprising task instructions, global remote sensing context, and fine-grained category semantics—effectively reduces class confusion and improves the localization of small and visually similar objects in complex very-high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The results show that combining large vision-language models with parameter-efficient adaptation is a practical and effective strategy for transferring general-purpose multimodal models to specialized remote sensing detection tasks under scarce annotations without incurring severe catastrophic forgetting.

- The effectiveness of injecting structured semantic priors through hierarchical prompts suggests a general paradigm for improving robustness and cross-dataset transfer in other remote sensing applications, such as instance segmentation and change detection.

Abstract

Few-shot object detection (FSOD) in high-resolution remote sensing (RS) imagery remains challenging due to scarce annotations, large intra-class variability, and high visual similarity between categories, which together limit the generalization ability of convolutional neural network (CNN)-based detectors. To address this issue, we explore leveraging large vision-language models (LVLMs) for FSOD in RS. We propose a two-stage, parameter-efficient fine-tuning framework with hierarchical prompting that adapts Qwen3-VL for object detection. In the first stage, low-rank adaptation (LoRA) modules are inserted into the vision and text encoders and trained jointly with a Detection Transformer (DETR)-style detection head on fully annotated base classes under three-level hierarchical prompts. In the second stage, the vision LoRA parameters are frozen, the text encoder is updated using -shot novel-class samples, and the detection head is partially frozen, with selected components refined using the same three-level hierarchical prompting scheme. To preserve base-class performance and reduce class confusion, we further introduce knowledge distillation and semantic consistency losses. Experiments on the DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2 datasets show that the proposed method consistently improves novel-class performance while maintaining competitive base-class accuracy and surpasses existing baselines, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating hierarchical semantic reasoning into LVLM-based FSOD for RS imagery.

1. Introduction

Remote sensing object detection (RSOD) underpins a wide range of military and civilian applications, such as target surveillance, urban management, transportation monitoring, environmental assessment, and disaster response. With continued improvements in spatial resolution and revisit frequency, along with the increasing availability of multimodal data, automatic and robust RSOD has become a core component of large-scale Earth observation systems. In the past decade, deep learning has significantly advanced this field: CNNs [1,2,3], and more recently Vision Transformers (ViTs) [4,5] together with DETR-style end-to-end detectors [6,7,8,9,10], have become the dominant paradigms for object detection in RS imagery. These models learn powerful hierarchical representations and have achieved state-of-the-art performance on many RS benchmarks. Nevertheless, RS imagery is characterized by arbitrary orientations, extreme aspect ratios, cluttered backgrounds, and pronounced scale and appearance variations, which has motivated a diverse set of oriented and rotated detection methods [11,12,13]. Despite these advances, current detectors still rely heavily on large-scale, high-quality annotations, whose acquisition is labor-intensive and requires expert knowledge due to complex scenes and visually similar categories. Although semi-supervised and weakly supervised learning, self-supervised pretraining, synthetic data, and active learning can partly reduce annotation costs, data-efficient detection remains a major bottleneck, especially for newly emerging or rare categories and under distribution shifts across regions, sensors, and seasons [6,14,15,16,17].

FSOD, which aims to detect instances of novel classes given only a few labeled examples per category, provides a promising direction to alleviate this problem. Visual-only FSOD methods, such as TFA [18], DeFRCN [19] and their variants, have achieved encouraging results on natural image benchmarks by refining feature learning and classification heads. However, in the extremely low-shot regime, these approaches still suffer from insufficient feature representations and severe overfitting. This issue becomes more pronounced in RS scenarios, where complex backgrounds, large intra-class variability, and subtle inter-class differences (e.g., among different types of vehicles, ships, or infrastructures) are ubiquitous. Moreover, most existing FSOD frameworks focus almost exclusively on visual feature learning and pay limited attention to explicit modeling of semantic information, which is essential for humans when recognizing novel objects. Semantic cues—such as textual descriptions of appearance, function, typical context, and relations between categories—can provide complementary priors to distinguish visually similar classes and to transfer knowledge from base to novel categories [20,21,22]. The insufficient exploitation of such semantic information has thus become a key barrier to building robust and generalizable FSOD models in RS imagery.

The rapid progress of LVLMs offers new opportunities to address this limitation. Recent studies have demonstrated that LVLMs possess strong category-level semantics and open-vocabulary recognition capabilities, which can in principle be transferred to RS object detection [23,24,25]. However, directly applying generic LVLMs to RS imagery is far from trivial. On the one hand, naïve fine-tuning of LVLMs is computationally expensive and prone to overfitting or catastrophic forgetting, especially when only a few RS samples are available. On the other hand, simple or manually designed prompts often fail to fully exploit the rich semantic knowledge embedded in LVLMs or to adapt it to the specific characteristics of RS imagery.

In this work, we address these challenges by proposing a two-stage fine-tuning framework of LVLMs with hierarchical prompting for FSOD in RS images. Our method builds upon Qwen3-VL [26] and adopts a parameter-efficient LoRA [27] scheme to adapt the model to remote sensing few-shot object detection (RS-FSOD) under scarce supervision. The core idea is to inject multi-level semantic priors into the detection pipeline through a hierarchical prompting mechanism, including task-level instructions, global RS context, and fine-grained category descriptions that encode appearance attributes, functional roles, and typical surroundings. Furthermore, we design a two-stage fine-tuning strategy: in the first stage, LoRA modules are inserted into the vision and text encoders and optimized jointly with a DETR-style detection head on fully annotated base classes, in order to learn RS-adapted cross-modal representations and basic detection capability; in the second stage, we freeze the visual LoRA modules and selectively adapt the text encoder and parts of the detection head using -shot novel-class samples, while introducing knowledge distillation and semantic consistency losses to preserve base-class knowledge and better align visual features with hierarchical prompts. This selective adaptation enables the model to acquire novel-class knowledge from both visual examples and semantic prompts, while alleviating catastrophic forgetting.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- We propose a novel LVLM-based framework for FSOD in RS imagery, which builds upon Qwen3-VL and employs parameter-efficient fine-tuning to adapt LVLMs to RS-FSOD under scarce annotations.

- We design a hierarchical prompting strategy that injects multi-level semantic priors—spanning task instructions, global RS context, and fine-grained category descriptions—into the detection pipeline, effectively compensating for limited visual supervision and mitigating confusion among visually similar categories.

- We develop a two-stage LoRA-based fine-tuning scheme that jointly optimizes vision and language branches on base classes and selectively adapts the text encoder and detection head for novel classes with distillation and semantic consistency constraints, thereby enhancing transferability to novel RS categories while mitigating catastrophic forgetting. Extensive experiments on DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2 demonstrate that the proposed method achieves competitive or superior performance compared with state-of-the-art FSOD approaches.

2. Related Work

Recent years have witnessed rapid progress in object detection for RS imagery, including both fully supervised detectors and few-shot models under data-scarce settings. In Section 2.1, we review representative CNN- and Transformer-based detectors for generic RSOD. In Section 2.2, we summarize advances in FSOD for RS and position our work within this line of research.

2.1. Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery

RSOD has evolved significantly with the introduction of deep learning, which has enabled detectors to better cope with the unique characteristics of aerial and satellite imagery. Early methods primarily focused on adapting traditional CNN-based architectures to handle the challenges presented by RS imagery, such as scale variation and dense object distributions. Models like ABNet [28], which integrates enhanced feature pyramids and attention mechanisms, and CFIM [29], which focuses on context-aware sampling, have laid the foundation for addressing the complexities of RSOD. These approaches typically combine enhanced feature pyramids, attention mechanisms, and multiscale processing to improve detection performance under varied scenes and object densities.

In recent years, the shift towards Transformer-based models has further advanced RSOD, largely due to their ability to model global contextual information effectively. For instance, PCViT [5] introduces a pyramid convolutional Vision Transformer that enhances feature extraction through parallel convolutional modules, showing remarkable performance in dense and multiscale RSOD scenarios. The CoF-Net framework [30] further refines this approach with a coarse-to-fine feature adaptation strategy that boosts detection accuracy under challenging conditions, such as complex backgrounds and varying object sizes. Transformer-based models have also been optimized to address specific challenges, such as rotated objects and small objects. MSFN [11] uses spatial-frequency domain features to improve the detection of rotated objects, while CPMFNet [12] focuses on arbitrary-oriented object detection through adaptive spatial perception modules. Moreover, models like EIA-PVT [13] have extended Transformer-based architectures to integrate local and global context in a more compact and efficient manner, demonstrating their potential for robust RSOD in highly variable environments.

Despite these advancements, detecting small, low-contrast, and densely distributed objects remains challenging in RSOD due to the high variation in size and shape, along with the presence of cluttered backgrounds. Approaches like RS-TOD [31] and DCS-YOLOv8 [32] have tackled these challenges by introducing innovative modules that enhance sensitivity to small objects and improve performance on datasets with small target objects. For instance, RS-TOD employs a remote sensing attention module (RSAM) and a lightweight detection head specifically designed for tiny objects. Similarly, methods such as GHOST [33] and Lino-YOLO [34] focus on reducing model complexity and improving efficiency, which is crucial for applications where real-time detection is needed. Additionally, advancements such as Bayes R-CNN [1] and YOLOv8-SP [35] are pushing the boundaries of object detection by incorporating uncertainty estimation and small-object-focused architecture, respectively.

Furthermore, the challenges of domain adaptation and the scarcity of labeled data in RS have spurred interest in semi-supervised and few-shot learning methods. FADA [14] and FIE-Net [15] propose foreground-alignment strategies to mitigate domain shift, while UAT [16] leverages uncertainty-aware models for semi-supervised detection. Few-shot detection has seen significant progress with FSDA-DETR [6] and MemDeT [36], which enhance detection performance under limited data conditions by incorporating memory-augmented modules and cross-domain feature alignment. We provide a more detailed review of few-shot RSOD in Section 2.2. These techniques are crucial in situations where labeled data is sparse or not available for certain target domains. Self-training and pseudo-labeling techniques, such as those found in PSTDet [17], have also contributed to improving detection performance in these scenarios.

Finally, with the rise of LVLMs, the integration of semantic priors from language and multimodal pretraining has opened new possibilities for RSOD. LLaMA-Unidetector [23] leverages the power of open-vocabulary detection by utilizing large language models to identify unseen object categories, significantly reducing the reliance on manually labeled data. This approach is further enhanced by frameworks like CDATOD-Diff [37], which combine CLIP-guided semantic priors with generative diffusion modules to improve detection in SAR imagery.

We note that these LVLM/LLM-based RSOD methods are mainly evaluated under open-vocabulary/zero-shot (or generalized) protocols, which are not directly comparable to the RS-FSOD setting (base/novel split with -shot supervision) studied in this paper. To our knowledge, there are currently no publicly available LLM-based RS-FSOD results reported under the same protocol; therefore, we mainly compare with standard RS-FSOD baselines for fair and protocol-consistent evaluation. Although these models show promise, challenges remain in effectively aligning vision-language representations with the unique characteristics of RS imagery under -shot supervision. This paper aims to address this challenge by introducing a two-stage fine-tuning strategy coupled with hierarchical prompting, thereby enhancing the adaptability of LVLMs to the RS-FSOD setting.

2.2. Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery

FSOD aims to alleviate the data-hungry nature of deep detectors and has been actively explored in both natural and RS imagery. In RS, early works mainly followed meta-learning paradigms, learning class-agnostic meta-features and class-specific prototypes from episodic tasks [2,3,38,39,40]. Examples include prototype-guided frameworks such as P-CNN [2], memory-augmented MM-RCNN [3], the YOLOv3-based meta-learner [38], multiscale contrastive MSOCL [39], and discriminative prototype learning in DPL-Net [40]. Although these methods demonstrate the feasibility of FSOD in high-resolution aerial scenes, they often suffer from optimization complexity, sensitivity to episodic design, and limited scalability to large vocabularies and ultra-high-resolution images.

Motivated by progress on natural image benchmarks, fine-tuning-based FSOD has become mainstream in RS. A large body of methods adopts a two-phase “base-training then few-shot fine-tuning” pipeline, while introducing RS-specific designs for scale, orientation, and class imbalance. Prototype-centric approaches refine the classification branch with more expressive class representations: HPMF [20] and InfRS [41] construct discriminative or hypergraph-guided prototypes, while G-FSDet [42] and related generalized/incremental FSOD methods [43,44,45,46] further address catastrophic forgetting through imprinting, drift rectification, multiscale knowledge distillation, and frequency-domain prompting. Other works explicitly tackle geometric and multiscale variations via transformation-invariant alignment [47], multiscale positive refinement [48], contrastive multiscale proposals [39], and multilevel query-support interaction [21,49,50]. Domain-specific issues such as complex backgrounds, small/dense objects, and biased proposals are handled by unbiased proposal filtration and tiny-object-aware losses [51], label-consistent classification and gradual regression [52], subspace separation with low-rank adapters [53], and augmentation-/self-training-based strategies that cope with sparse or incomplete annotations [22,54,55].

In parallel, contrastive learning, memory, transformers, and domain adaptation have further enriched RS-FSOD. Contrastive objectives are used to enhance inter-class separability under high visual similarity [25,39,55,56], while memory or prototype-guided alignment stabilizes representations and mitigates forgetting [3,36,57]. Transformer-based detectors such as CAMCFormer [21], MemDeT [36], Protoalign [57], FSDA-DETR [6], and CD-ViTO [58] leverage long-range self-/cross-attention for joint modeling of query-support relations and global context, with AsyFOD [59] and FSDA-DETR [6] extending FSOD to cross-domain scenarios via asymmetric or category-aware alignment.

A clear trend in recent work is moving beyond purely visual cues toward semantic and language-guided FSOD. CLIP-based and multimodal prototype methods [24,25,36,57,60,61] exploit textual labels or LVLMs to provide category-level priors that are agnostic to specific images, thereby improving generalization to novel classes under severe data scarcity. At the same time, generative models and frequency-domain techniques are used to enrich supervision, e.g., controllable diffusion-based data synthesis in CGK-FSOD and related work [62,63], and frequency compression and new benchmarks for infrared FSOD in FC-fsd [64]. YOLO-based RS-FSOD systems [38,65,66] also incorporate global context, segmentation assistance, or distillation heads to balance efficiency and accuracy.

Despite these advances, existing RS-FSOD methods typically employ either task-specific meta-learning or single-stage visual fine-tuning, and most semantic- or language-enhanced approaches use relatively shallow fusion strategies or fixed textual prompts [24,25,36,57,60]. In the extremely low-shot regime, they still struggle with limited visual supervision, complex and cluttered backgrounds, and subtle inter-class differences (e.g., among vehicles, ships, and infrastructure). This gap motivates our work, Two-Stage Fine-Tuning of Large Vision-Language Models with Hierarchical Prompting for Few-Shot Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images, which explicitly leverages large-scale vision-language pretraining and a hierarchical prompting scheme within a two-stage fine-tuning framework, aiming to more effectively transfer semantic knowledge to novel RS categories under very scarce annotations.

3. Methods

In this section, we first formalize the few-shot detection setting and introduce the Qwen3-VL base model in Section 3.1. We then describe the overall architecture of our RS-FSOD framework in Section 3.2, followed by the hierarchical prompting mechanism in Section 3.3 and the DETR-style detection head in Section 3.4. Finally, we present the two-stage LoRA-based fine-tuning strategy with knowledge distillation and semantic consistency regularization in Section 3.5.

3.1. Preliminary Knowledge

3.1.1. Problem Setting

We adhere to the standard problem definition of FSOD established in previous works such as TFA [18] and G-FSDet [42]. The objective is to train a detector capable of identifying novel objects given only a few annotated examples, leveraging knowledge transfer from abundant base classes.

Formally, the object categories are divided into two disjoint sets: base classes () and novel classes (), where . The corresponding dataset consists of a base dataset and a novel dataset .

- Base Training Phase: The model is trained on , which contains a large number of annotated instances for categories in .

- Fine-tuning Phase: The model is adapted using , which follows a -shot setting. For each category in , only annotated instances (e.g., ) are available.

The ultimate goal is to obtain a model that achieves high detection performance on while minimizing catastrophic forgetting on .

3.1.2. Base Model: Qwen3-VL

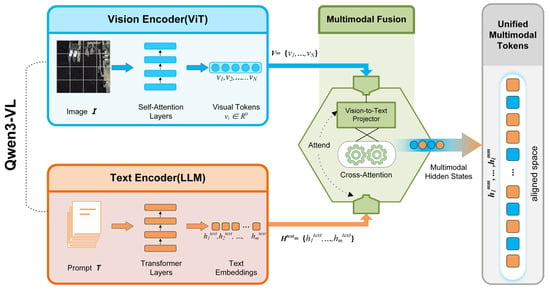

We build our method upon Qwen3-VL, an LVLM that jointly processes images and text. As illustrated in Figure 1, Qwen3-VL comprises a vision encoder, a text encoder, and a multimodal fusion module.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the base model Qwen3-VL. Qwen3-VL is an LVLM that jointly processes images and text and serves as the backbone of our proposed framework. It consists of three main components: (i) a ViT-based vision encoder that extracts visual features from the input RS images, (ii) a Transformer-based language model acting as the text encoder to obtain semantic representations from textual prompts, and (iii) a multimodal fusion module that integrates visual and textual features to produce cross-modal representations for subsequent FSOD.

Vision encoder. The vision encoder is a Vision Transformer (ViT)-style network that takes an input image I and converts it into a sequence of visual tokens. The image is first divided into patches, which are linearly projected and added with positional embeddings. The resulting patch embeddings are processed by multiple self-attention layers, producing a sequence of visual features:

where is the number of image tokens and is the hidden dimensionality. In our framework, these visual tokens serve as the primary representation of RS images.

Text encoder (LLM). The text branch of Qwen3-VL is built on top of a large autoregressive Transformer language model. Given a tokenized prompt sequence , which in our case encodes the hierarchical instructions and category descriptions, the LLM produces contextualized text embeddings:

These embeddings capture rich semantic information about the detection task, RS context, and fine-grained categories, and can interact with visual tokens through multimodal fusion.

Multimodal fusion. Qwen3-VL integrates visual and textual information via a series of cross-attention and projection layers that map visual tokens into the language model’s representation space. Concretely, the visual features are first transformed by a vision-to-text projector and then injected into the LLM as special tokens or through cross-attention blocks. This produces a sequence of multimodal hidden states:

where each token can attend to both visual and textual information. These multimodal tokens form a unified representation space in which visual patterns and language semantics are aligned.

In our work, we treat Qwen3-VL as a frozen multimodal backbone and adapt it to the RS-FSOD task using parameter-efficient fine-tuning. We take the multimodal hidden states as the input memory for a lightweight detection head and insert LoRA modules into selected linear layers of the vision encoder and text encoder, as detailed in the following sections.

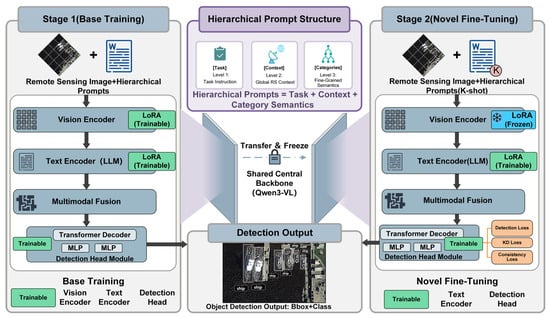

3.2. Overall Architecture

In this work, we propose a two-stage fine-tuning framework built upon the Qwen3-VL, combined with a hierarchical prompting mechanism to enhance FSOD in RS imagery. The overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 2. It consists of a Qwen3-VL backbone that performs cross-modal feature learning, a DETR-style detection head for box and class prediction, and a two-stage LoRA-based parameter-efficient fine-tuning strategy guided by hierarchical prompts, knowledge distillation, and semantic consistency constraints.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed Qwen3-VL-based few-shot detection framework. The architecture consists of a Qwen3-VL backbone for cross-modal feature learning, a DETR-style detection head, and a two-stage LoRA-based fine-tuning strategy guided by hierarchical prompts. In the Base Training stage (left), LoRA adapters are inserted into the vision and text encoders and trained jointly with the fully learnable detection head on fully annotated base classes, enabling the model to acquire remote-sensing-adapted cross-modal representations and basic detection capability. In the Novel Fine-tuning stage (right), visual LoRA modules are frozen, while LoRA in the text encoder and selected layers of the detection head remain trainable and are updated using -shot novel-class samples. Hierarchical prompts encode superclass-to-fine-class semantics for both stages, and knowledge distillation together with semantic consistency loss is applied in Stage 2 to preserve base-class knowledge and reduce semantic drift during few-shot adaptation.

We first adapt Qwen3-VL to the detection setting by attaching a detection head on top of the fused multimodal features. Concretely, we follow a DETR-style design: the multimodal hidden states produced by Qwen3-VL are treated as the encoder memory, and a set of learnable object queries is fed into a multi-layer Transformer decoder. Each decoded query feature is then passed through two small multilayer perceptrons (MLPs): a classification head that outputs category logits and a regression head that predicts bounding box parameters. This design preserves the simplicity and set-prediction nature of DETR-style detectors, while making it straightforward to consume the sequence of multimodal tokens produced by Qwen3-VL.

To adapt the large backbone to RS-FSOD in a parameter-efficient manner, we adopt LoRA and implement it through the parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) framework [67]. We insert LoRA modules into the key linear layers of the ViT-based vision encoder and the Transformer-based language model (text encoder), while the DETR-style detection head is trained with its own parameters but without LoRA adapters. During fine-tuning, we mainly update the LoRA parameters in the encoders together with the parameters of the detection head, while keeping the original Qwen3-VL weights frozen. This design significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters in the backbone and allows the pretrained multimodal knowledge to be preserved, which is particularly beneficial when transferring to RS domains with limited labeled data.

Figure 2 is organized into two panels. The left panel shows the Base Training stage: given RS images and hierarchical prompts, the vision encoder and text encoder are equipped with trainable LoRA adapters (highlighted in green), and the DETR-style detection head is fully trainable. The model is trained on fully annotated base classes to learn remote-sensing-adapted cross-modal representations and basic detection capability. The right panel shows the Novel Fine-tuning stage: the LoRA modules in the vision encoder are frozen (rendered in blue), while only the LoRA parameters in the text encoder and selected layers of the detection head remain trainable. In this stage, the model is adapted using -shot samples of novel classes, under the guidance of hierarchical prompts that encode superclass-to-fine-class semantics. Detection loss on the novel classes is augmented with knowledge distillation loss and semantic consistency loss to preserve base-class performance and reduce semantic confusion, without mixing additional base-class images into the few-shot training set.

Overall, our architecture exploits (i) cross-modal feature learning in Qwen3-VL, (ii) hierarchical prompts to inject structured semantic priors, (iii) a two-stage LoRA-based fine-tuning strategy that selectively updates the text encoder and parts of the detection head while keeping the visual backbone largely frozen, and (iv) knowledge distillation and consistency regularization to mitigate catastrophic forgetting and semantic drift, thereby achieving robust few-shot detection in complex RS scenes.

3.3. Hierarchical Prompting Mechanism

A key component of our framework is the hierarchical prompting mechanism, which injects structured semantic priors into Qwen3-VL in order to cope with the complexity of RS scenes and the scarcity of novel-class annotations. Simple prompts such as “Detect objects in this image.” provide only coarse task instructions and are insufficient to distinguish visually and semantically similar categories under few-shot supervision, for example, separating “airplane” from “airport” or “storage tank” from “chimney” in the DIOR dataset. To address this limitation, we design a three-level hierarchical prompt that explicitly encodes task instructions, global remote sensing context, and fine-grained category semantics. The dataset-specific instantiations (covering all DIOR 20 classes and NWPU VHR-10.v2 10 classes) are provided in Appendix A and Appendix B, respectively.

Level 1: Task Instruction.

The first level specifies the detection task and the desired output format. It instructs the model to localize all objects in an overhead image and output bounding boxes with category labels. This aligns the generic instruction-following capability of Qwen3-VL with the concrete objective of remote sensing object detection. For example:

You are an expert in remote sensing object detection. Given an overhead image, detect all objects of interest and output their bounding boxes and category labels.

Level 2: Global Remote Sensing Context.

The second level provides high-level priors about remote sensing imagery, including the bird’s-eye viewpoint, multiscale and densely distributed objects, and typical object families. This guides the model to interpret visual patterns under RS-specific assumptions and reduces ambiguity when visual evidence is weak. For example:

The image is an 800 × 800-pixel overhead view acquired by satellite or aerial sensors under varying ground sampling distances (approximately 0.5–30 m). Objects can be extremely multiscale, densely packed, and arbitrarily oriented, with frequent background clutter, shadows, and repetitive textures. Scenes cover airports and airfields; expressways and highway facilities (service areas, toll stations, overpasses, bridges); ports and shorelines; large industrial zones (storage tanks, chimneys, windmills, dams); and urban or suburban districts with sports venues (baseball fields, basketball/tennis courts, golf courses, stadiums). Backgrounds can be cluttered and visually similar, and discriminative cues often come from fine-grained shapes, markings, and spatial context.

Level 3: Fine-Grained Category Semantics.

The third level builds a semantic dictionary of categories, where each superclass and its fine-grained classes are described by short textual definitions, including appearance attributes, functional roles, and typical locations. For each superclass , we enumerate its fine-grained classes and construct a template-based description. For example:

Superclass: Road transportation and facilities (vehicles and highway-related structures).

Fine-grained classes:

- vehicle: Small man-made transport targets on roads/parking lots (cars, buses, trucks); compact rectangles with short shadows.

- expressway service area: Highway rest areas with large parking lots, gas pumps and service buildings; near ramps.

- expressway toll station: Toll plazas spanning multiple lanes with booths and canopies; strong lane markings at entries/exits.

- overpass: Elevated roadway segments crossing other roads/rails; ramps, pylons and cast shadows.

- bridge: Elevated linear structures spanning water or obstacles; approach ramps and structural shadows.

Similarly, we define categories such as “storage tank”, “ship”, and “tennis court” based on their shapes, textures, and contextual surroundings. These detailed descriptions encourage the model to focus on discriminative cues that separate visually similar categories and to exploit the category hierarchy encoded by the prompt.

In practice, we concatenate the three levels into a single prompt sequence with explicit segment markers (“[Task]”, “[Context]”, “[Categories]”) and feed it into the Qwen3-VL text encoder. The same hierarchical prompt structure is used in both the base and novel stages; only the fine-grained category list is expanded to include novel classes in the second stage. By consistently conditioning on hierarchical prompts, the model learns to align visual features with structured semantic information and to leverage language priors for few-shot generalization, especially when novel-class examples are extremely limited.

3.4. DETR-Style Detection Head

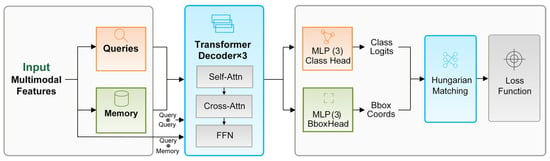

To enable end-to-end object detection in the proposed framework, we integrate a DETR-style detection head that directly processes the multimodal features extracted by Qwen3-VL. Unlike conventional anchor-based detectors, our detection head formulates object detection as a set prediction problem solved via bipartite matching, which is particularly advantageous for RS imagery characterized by varying object scales and arbitrary spatial distributions. The detailed architecture of the detection head is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the DETR-style detection head.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the detection head consists of three core components:

- A set of learnable object queries , which serve as input tokens to the decoder and are optimized jointly with the multimodal features , where denotes the hidden dimension.

- A Transformer decoder with layers that iteratively refines query representations through self-attention and cross-attention with the input multimodal features extracted from the vision-language encoder;

- Dual prediction heads that output class probabilities and bounding box coordinates in parallel. Specifically, for each query , the decoder produces an enhanced representation , which is subsequently fed into a three-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for classification and a separate three-layer MLP for bounding box regression. The classification head predicts -dimensional logits (where for the DIOR dataset, with an additional background class), while the regression head outputs normalized bounding box parameters .

Detection Loss. We employ a DETR-style detection loss based on bipartite matching between predicted queries and ground-truth objects. For each image, the Hungarian algorithm is used to find an optimal assignment that minimizes a matching cost combining classification scores, L1 box regression, and the Generalized Intersection over Union (GIoU) loss. Given a matched pair with class , the detection loss is defined as:

where denotes the classification loss, represents the L1 bounding box regression loss, and corresponds to the GIoU loss. To address the class imbalance prevalent in RS datasets, we implement as focal loss with and , and assign a reduced weight to the background class. The loss weights are empirically set to and , prioritizing localization accuracy over classification. The matching cost used in Hungarian assignment is

where denotes the predicted probability for class , and and denote the ground-truth and predicted boxes, respectively.

Adaptation for Few-Shot Learning. In the few-shot fine-tuning stage (Stage 2), we adopt a partial-freezing strategy, where the first decoder layers are frozen to preserve learned general object representations, while the final decoder layer and both prediction heads remain trainable to adapt to novel classes with limited samples. This design mitigates overfitting on scarce training data while retaining the capacity to discriminate fine-grained class-specific features. The specific detection loss and training objectives for the two stages are detailed in Section 3.5.

3.5. Two-Stage Fine-Tuning Strategy

We design a two-stage fine-tuning strategy to efficiently adapt Qwen3-VL to RS-FSOD while mitigating catastrophic forgetting and exploiting hierarchical semantic priors.

Stage 1: Base Training.

In the first stage, we insert LoRA modules into both the vision encoder and the text encoder, and jointly optimize them together with the DETR-style detection head on fully annotated base classes. Given an input RS image and its corresponding hierarchical prompt, the model outputs query-wise class probabilities and bounding box predictions. Let denote the standard DETR-style detection loss on base classes, which combines classification loss and box regression loss under Hungarian matching. The Stage-1 objective is:

Through this stage, the model acquires remote-sensing-adapted cross-modal representations and basic detection capability on the base-class set . The resulting model is then frozen as a teacher to guide the subsequent few-shot adaptation.

Stage 2: Few-Shot Adaptation.

In the second stage, we adapt the model to novel classes using only -shot labeled samples per novel class. To preserve the visual representations learned in Stage 1, we freeze all LoRA parameters in the vision encoder. For the DETR-style detection head, we adopt a partial-freezing strategy, where the first decoder layers are frozen to retain general object representations, while the final decoder layer and both prediction heads remain trainable. At the same time, we update the LoRA modules in the text encoder. This selective adaptation allows the model to refine its semantic understanding and detection behavior for novel categories, while keeping the visual backbone features and most of the detection head stable. Compared with full-parameter fine-tuning, this strategy reduces overfitting to scarce novel data and better preserves base-class detection ability.

The overall loss in Stage 2 combines the standard detection loss with a knowledge distillation loss and a semantic consistency loss:

Knowledge distillation loss.

To prevent catastrophic forgetting of base classes, we distill both classification and localization knowledge from the Stage-1 teacher model. For images containing base-class instances, let and be the classification logits of the -th query from the teacher and student, and let , denote their corresponding box predictions. The knowledge distillation loss is defined as:

where is the softmax function, and are fixed (non-learnable) hyperparameters in all experiments; we set and . This loss encourages the student to preserve the teacher’s behavior on base classes, thereby alleviating catastrophic forgetting.

Semantic consistency loss.

To better exploit the hierarchical prompts, we explicitly enforce consistency between fine-grained predictions and superclass-level semantics. Let be a mapping from each superclass to its fine-grained classes . Given the fine-grained class probabilities of a query , we aggregate them to obtain an induced superclass distribution:

Meanwhile, the model predicts an explicit superclass-level distribution using a lightweight superclass prediction head on the query features (followed by a softmax). The semantic consistency loss is then defined as:

where the superclass target is derived from the fine-grained ground-truth label through the mapping , requiring no additional annotations.

By freezing the visual LoRA modules, selectively adapting the text encoder and parts of the detection head, and incorporating knowledge distillation and semantic consistency regularization, the proposed two-stage strategy enables the model to acquire novel-class knowledge from both visual examples and hierarchical prompts, while effectively alleviating catastrophic forgetting of base classes.

4. Experiments and Results

In this section, we present experimental results to evaluate the proposed Qwen3-VL-based RS-FSOD framework. In Section 4.1, we introduce the datasets and few-shot evaluation protocols. In Section 4.2, we describe the evaluation metrics and implementation details. In Section 4.3, we report main results on the DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2 benchmarks. In Section 4.4, we conduct ablation studies on hierarchical prompting, the two-stage fine-tuning strategy, the Stage-2 freezing strategy, and the choice of LoRA rank. In Section 4.5, we further analyze the efficiency and computational cost of our method.

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.1.1. Datasets

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted extensive experiments on two widely used optical RS datasets: DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2.

DIOR Dataset [68]: The DIOR dataset is a large-scale and challenging benchmark for optical RSOD. It consists of 23,463 images with a fixed size of pixels and covers 20 categories. The images are collected from Google Earth, with spatial resolutions ranging from 0.5 m to 30 m. Characterized by high inter-class similarity and substantial variations in object scale, this dataset serves as a rigorous testbed for evaluating few-shot learning in complex scenes. The 20 object categories include: airplane, airport, baseball field, basketball court, bridge, chimney, dam, expressway service area, expressway toll station, golf course, ground track field, harbor, overpass, ship, stadium, storage tank, tennis court, train station, vehicle, and windmill.

NWPU VHR-10.v2 Dataset [69]: The NWPU VHR-10.v2 dataset is a high-resolution benchmark for geospatial object detection. It comprises 1173 optical images with a standardized size of pixels and covers 10 categories. The images are cropped from Google Earth and the Vaihingen dataset and feature very high spatial resolution details. Distinguished by its fine-grained object textures and diverse orientations, this dataset is utilized to verify the generalization ability of models across different domains. The 10 object categories include: airplane, baseball diamond, basketball court, bridge, ground track field, harbor, ship, storage tank, tennis court, and vehicle.

We adopt standard class splitting and -shot sampling protocols [42,60]. For DIOR, 15 categories are used as base classes and the remaining 5 are treated as novel classes; for NWPU VHR-10.v2, 7 categories are designated as base and 3 as novel. The detailed compositions of base and novel sets for both datasets are provided in Table 1 and Table 2. During training, the model is first trained on the base classes with abundant annotations and then fine-tuned in a second stage on a balanced few-shot dataset containing exactly annotated instances per class. We evaluate performance under four low-data regimes with .

Table 1.

Base/novel class splits on DIOR.

Table 2.

Base/novel class splits on NWPU VHR-10.v2.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

We adopt the Mean Average Precision (mAP) at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 as the primary evaluation metric for our few-shot object detector. To comprehensively analyze the model’s performance and the problem of catastrophic forgetting, we report three specific indicators:

Base mAP (): The mAP on the base classes, used to monitor the extent of knowledge retention from the Base Training stage.

Novel mAP (): The mAP calculated only on the unseen novel classes. This is the most critical metric for evaluating few-shot learning efficacy.

Overall mAP (): The mAP averaged over all categories.

4.2. Implementation Details

4.2.1. Environment and Pretraining

All experiments are implemented in PyTorch (v2.5.1) using the HuggingFace Transformers (v4.57.1) and PEFT libraries (v0.18.0). Training is conducted on two NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada GPUs with mixed-precision (FP16) to accelerate both stages, and we employ DeepSpeed (v0.18.2, Stage 2) for memory-efficient data-parallel training. We adopt Qwen3-VL-8B as the backbone model. The backbone is initialized from the publicly released Qwen3-VL-8B checkpoint, and all original backbone parameters are kept frozen during fine-tuning; only the LoRA adapters in the vision and text encoders, together with the lightweight DETR-style detection head, are updated.

4.2.2. Hyperparameters

We use the same set of hyperparameters for all experiments with Qwen3-VL-8B. AdamW is used for optimization with a weight decay of in both stages.

Stage 1 (base training): initial learning rate , batch size 16 images per GPU (total 32), maximum 30 epochs.

Stage 2 (few-shot adaptation): initial learning rate , batch size 8 images per GPU (total 16), maximum 15 epochs.

In both stages, we adopt a cosine learning-rate schedule with a linear warm-up of 1 epoch. The LoRA rank is set to 128 by default, with and .

4.2.3. Training Details

In Stage 1, the model is trained on the full base dataset with hierarchical prompts covering all base classes. In Stage 2, we construct the few-shot novel set by randomly sampling instances per novel class and fine-tune the model using only these -shot novel samples under the detection loss, while employing knowledge distillation and semantic consistency losses to preserve base-class knowledge and reduce semantic drift. For both stages, we use early stopping based on validation mAP: if the validation performance does not improve for 5 consecutive epochs, training is stopped and the checkpoint with the best validation mAP is retained.

To reduce the variance caused by few-shot sampling, each -shot configuration is repeated five times with independent sampling trials for the Qwen3-VL-8B model. For each trial, we re-sample instances per novel class and re-train Stage 2 starting from the same Stage-1 checkpoint. We report the mean mAP over these five runs as the final performance.

4.3. Main Results

To rigorously evaluate our method, we conduct comprehensive experiments on the DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2 benchmarks, comparing it against six recent state-of-the-art FSOD approaches that collectively span the two dominant paradigms in RS-FSOD. Specifically, we consider fine-tuning-based methods—such as G-FSDet [42] and RIFR [49]—which emphasize efficient transfer learning and careful balancing of base and novel class performance to alleviate catastrophic forgetting; and prototype-/meta-learning-based methods, including Meta-RCNN [70], P-CNN [2], TPG-FSOD [60], and GIDR [43], which construct class prototypes from limited support samples and align query features via metric learning, attention mechanisms, or hypergraph-guided refinement. Under a unified evaluation protocol—using standard base/novel splits and mAP@0.5 across 3/5/10/20-shot settings—our approach attains consistently competitive performance and, in many settings, yields clear improvements over existing methods.

4.3.1. Results on DIOR

Table 3 presents a detailed comparison on DIOR under 3/5/10/20-shot settings and four splits. Several trends align well with the design of our Qwen3-VL-based two-stage fine-tuning framework. First, our method achieves strong or competitive base mAP compared with fine-tuning-based baselines such as G-FSDet [42] and RIFR [49]. For example, in Split 1, our base mAP remains comparable to RIFR [49] across all shot settings, and is slightly higher at medium and high shots (e.g., 71.03% vs. 69.72% at 10-shot and 71.14% vs. 70.96% at 20-shot), while in Split 2 we obtain the highest base mAP at 3-shot and 20-shot (71.63% and 71.89%). Similar trends can be observed in Splits 3 and 4, where our base performance closely tracks or slightly improves over G-FSDet [42] and RIFR [49]. These results indicate that freezing the vision-side LoRA adapters in the second stage, together with knowledge distillation and semantic consistency losses, effectively preserves the generic visual representations learned from base classes and mitigates catastrophic forgetting.

Table 3.

Comparison of FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) on the DIOR dataset under different -shot settings. We report base mAP, novel mAP, and overall mAP for four splits. The best and second-best results in each column are highlighted in red and blue, respectively.

Second, our approach delivers consistent and often substantial gains on novel mAP across almost all splits and shot settings. In Split 1, our method achieves the best novel mAP under every -shot condition, e.g., 34.94% vs. 28.51% (RIFR [49]) and 34.20% (TPG-FSOD [60]) at 3-shot, and 44.21% vs. 41.32% (RIFR [49]) and 43.80% (GIDR [43]) at 20-shot. Similar improvements are observed in Split 2, where our novel mAP clearly surpasses fine-tuning-based methods and prototype/meta-learning approaches as increases (e.g., 27.24% vs. 24.10% for RIFR [49] and 24.40% for GIDR [43] at 20-shot). In Splits 3 and 4, our method also achieves consistently higher or highly competitive novel mAP across all -shot settings. These gains suggest that the cross-modal Qwen3-VL backbone, when combined with hierarchical prompting, LoRA-based adaptation in the text encoder, and partial fine-tuning of the detection head in the second stage, can effectively encode structured semantic priors and better exploit limited novel-class examples, thereby improving category discrimination in few-shot regimes.

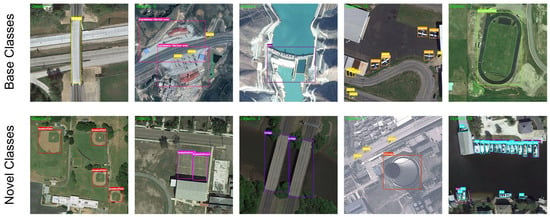

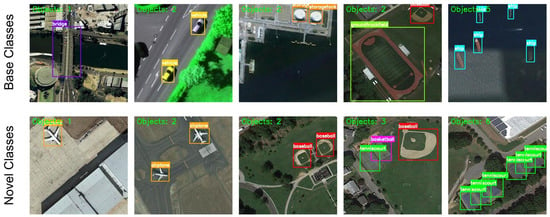

Finally, the overall mAP () of our method is consistently competitive and, in most cases, superior to all baselines, especially in the medium- and high-shot settings. For instance, in Split 1, our method achieves the highest overall mAP for 10- and 20-shot (63.85% and 64.41%), and in Split 2 it generally achieves the best overall mAP, especially at 3-, 10-, and 20-shot settings (e.g., 60.73% at 20-shot vs. 59.80% for RIFR [49]). In Splits 3 and 4, our overall mAP is comparable to RIFR [49] while consistently outperforming prototype/meta-learning methods, and in Split 4 it further surpasses RIFR [49] across all -shot configurations. This reflects a favorable trade-off between base and novel performance: the model not only improves recognition of novel categories but also maintains strong base-class accuracy. The robustness of these gains across different class splits further indicates that the proposed two-stage LoRA fine-tuning strategy, guided by hierarchical prompts and distillation/consistency constraints, provides a stable and effective solution for FSOD in complex RS scenes. To further provide an intuitive understanding of the detection quality under the few-shot setting, Figure 4 visualizes representative 10-shot detection results on DIOR Split 1, where the first row shows base-class predictions and the second row shows novel-class predictions.

Figure 4.

Visualization of detection results in the 10-shot experiments on the DIOR dataset under Class Split 1. The first row presents examples from the base classes, while the second row presents examples from the novel classes.

4.3.2. Results on NWPU VHR-10.v2

Table 4 reports the few-shot detection results on NWPU VHR-10.v2 under 3/5/10/20-shot settings and two splits. Overall, the trends further validate the effectiveness and generalization ability of our Qwen3-VL-based two-stage fine-tuning framework.

Table 4.

Comparison of FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) on the NWPU VHR-10.v2 dataset under different -shot settings. We report base mAP, novel mAP, and overall mAP for two splits. The best and second-best results in each column are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. Note that RIFR [49] reports results only on Class Split 1.

In Split 1, our method consistently achieves the best performance across all shot settings. For base classes, we obtain the highest base mAP in every -shot configuration (e.g., 96.67%/96.54%/96.61% at 3/10/20-shot), clearly surpassing fine-tuning-based methods such as G-FSDet [42] and RIFR [49]. At the same time, we substantially improve novel mAP over these baselines (e.g., 67.51% vs. 53.17% for RIFR [49] at 3-shot, and 86.74% vs. 79.46% at 20-shot), while also outperforming prototype/meta-learning approaches such as GIDR [43] under all shot settings. As a result, our method achieves the best overall mAP across all -shot settings, with particularly large margins in the high-shot regime (e.g., 93.65% vs. 90.61% for RIFR [49] and 85.00% for TPG-FSOD [60] at 20-shot). These results indicate that the proposed two-stage LoRA fine-tuning, combined with knowledge distillation and semantic consistency regularization, can effectively preserve base-class knowledge while significantly enhancing novel-class detection.

In Split 2, our approach shows similarly strong performance and stable behavior across different -shot settings. At low-shot (3-shot), we already achieve the best novel mAP (51.48%) and overall mAP (79.58%), while maintaining a higher base mAP than P-CNN [2] and comparable or better base mAP than G-FSDet [42] and TPG-FSOD [60]. As increases, the advantages of our framework become more pronounced: at 5/10/20-shot, we obtain the highest base mAP (91.51%, 91.27%, and 91.02%), the highest novel mAP (59.68%, 70.19%, and 78.47%), and the highest overall mAP (81.96%, 84.95%, and 87.26%) among all compared methods. This demonstrates that, as more support examples are available, our cross-modal Qwen3-VL backbone—adapted via hierarchical prompts, LoRA-based updates in the text encoder, and partial fine-tuning of the detection head—can better exploit both visual and semantic cues to boost novel-class discrimination without sacrificing base-class performance.

Taken together, the NWPU VHR-10.v2 results complement our findings on DIOR and show that the proposed Qwen3-VL-based two-stage fine-tuning framework generalizes well across RS datasets. By jointly leveraging cross-modal feature learning, hierarchical prompting, parameter-efficient LoRA adaptation, and distillation/consistency constraints, our method achieves a favorable balance between base-class retention and novel-class generalization, leading to consistently superior overall mAP in diverse few-shot settings. To further provide an intuitive understanding of the detection quality under the few-shot setting, Figure 5 visualizes representative 10-shot detection results on the NWPU VHR-10.v2 dataset under Class Split 1, where the first row shows base-class predictions and the second row shows novel-class predictions.

Figure 5.

Visualization of detection results in the 10-shot experiments on the NWPU VHR-10.v2 dataset under Class Split 1. The first row presents examples from the base classes, while the second row presents examples from the novel classes.

4.4. Ablation Studies

We conduct ablation studies to analyze the contributions of the key components in our framework, including hierarchical prompting, the two-stage fine-tuning strategy, the Stage-2 freezing strategy, and the choice of LoRA rank. All ablations are performed on the DIOR dataset using Class Split 1 under the standard few-shot setting.

4.4.1. Effect of Hierarchical Prompting

To examine the effectiveness of semantic injection via prompts and to disentangle the impact of content richness from hierarchical structure, we compare the following variants under the same training and evaluation settings:

- No Prompt: The text encoder is not conditioned on any instruction; only class labels are provided as identifiers.

- L1 Only: We use only the first-level task instruction (i.e., the same detection instruction as in our hierarchical design), without additional global context or fine-grained semantics.

- L1 + L2: We add the second-level global remote sensing context on top of L1, while excluding category-specific descriptions.

- Flat Detailed Prompt: We include the same information as the complete three-level prompt (L1–L3) but flatten it into a single paragraph without explicit hierarchical formatting, serving as a control to isolate the effect of hierarchical structure.

- Hierarchical Prompt (ours): The full three-level design described in Section 3.3, comprising task instruction (L1), global remote sensing context (L2), and fine-grained category semantics (L3).

This set of comparisons allows us to (i) quantify the contribution of each prompt level (L1 → L1 + L2 → L1 + L2 + L3) and (ii) assess whether the hierarchical organization itself provides benefits beyond simply adding more descriptive text (Flat Detailed vs. Hierarchical).

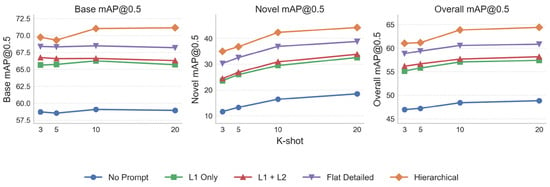

Table 5 summarizes the effect of different prompt designs under Class Split 1 on DIOR across -shot settings, and Figure 6 provides a visual illustration of these trends. Overall, introducing prompts consistently improves FSOD performance, with the most pronounced gains on novel classes. Compared with No Prompt, even the minimal task instruction (L1 Only) yields large improvements across all shots (e.g., novel mAP increases from 11.62 to 23.59 at 3-shot, and from 18.47 to 32.57 at 20-shot), indicating that explicitly conditioning the text encoder with task-related instructions already strengthens vision–language alignment and benefits few-shot transfer.

Table 5.

Effect of hierarchical prompting on FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) under Class Split 1 on DIOR across different -shot settings. The best results are highlighted in bold.

Figure 6.

Effect of different prompting strategies on FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) on DIOR under Class Split 1 across varying -shot settings. From left to right, we report base, novel, and overall mAP, respectively. Each curve corresponds to one prompt variant, including No Prompt, L1 Only, L1 + L2, Flat Detailed Prompt (L1–L3 content flattened into a single paragraph), and the proposed hierarchical prompt (explicit three-level structuring with the same L1–L3 content). The proposed hierarchical prompt consistently achieves the best performance across all shot settings, with particularly large improvements on novel classes.

Further, adding global remote-sensing context (L2) on top of L1 brings consistent but relatively modest gains. For instance, the novel mAP improves from 23.59/25.95/29.47/32.57 (L1 only) to 24.41/26.84/30.89/33.82 (L1 + L2) under 3/5/10/20-shot settings. In contrast, injecting fine-grained category semantics (i.e., adding L3 content) contributes the largest marginal improvement. When moving from L1 + L2 to Flat Detailed (which contains the same full L1–L3 semantic information but removes explicit hierarchical formatting), novel mAP increases by +5.87, +5.72, +5.98, and +4.97 for 3/5/10/20-shot, respectively, showing that detailed category-level semantics are most critical for recognizing novel categories with limited labeled examples.

Finally, the proposed hierarchical prompt consistently achieves the best results across all -shot regimes, outperforming Flat Detailed despite using the same L1–L3 semantic content, which verifies the additional benefit of hierarchical structuring beyond simply adding more descriptive text. Specifically, Hierarchical Prompt improves novel mAP over Flat Detailed from 30.28/32.56/36.87/38.79 to 34.94/36.76/42.31/44.21 under 3/5/10/20-shot and increases overall mAP from 58.85/59.37/60.56/60.84 to 61.03/61.17/63.85/64.41. These results indicate that while L1 provides essential task conditioning and L2 offers minor complementary context, fine-grained L3 semantics bring the largest performance gains, and the explicit hierarchical organization further enhances both novel-class and overall detection performance.

4.4.2. Effect of Two-Stage Fine-Tuning Strategies

We next study the impact of the two-stage fine-tuning scheme. We compare:

- Joint Training: base and novel classes are mixed and trained in a single stage using all available data, with all LoRA modules updated jointly.

- Two-Stage (ours): the proposed Stage-1 base training followed by Stage-2 few-shot adaptation, with selective freezing of visual LoRA modules, partial fine-tuning of the detection head, and additional knowledge distillation and semantic consistency losses.

Table 6 reports the ablation results of different fine-tuning strategies under Class Split 1 on DIOR. Overall, the proposed two-stage scheme brings consistent gains over Joint Training across all -shot settings.

Table 6.

Effect of two-stage fine-tuning strategies on FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) under Class Split 1 on DIOR for different -shot settings. The best results are highlighted in bold.

First, the two-stage strategy yields substantial improvements on novel classes while maintaining or slightly enhancing base performance. In low-shot regimes (3/5-shot), the two-stage training improves novel mAP from 25.17% to 34.94% (+9.77) and from 26.58% to 36.76% (+10.18), respectively, while base mAP remains very similar or slightly better (69.17% → 69.73% and 68.82% → 69.31%). As increases, the novel-class gains remain clear: at 10/20-shot, novel mAP is boosted from 34.89%/39.17% (Joint) to 42.31%/44.21% (two-stage), with improvements of +7.42 and +5.04. Meanwhile, base mAP also benefits more in the higher-shot settings (69.57% → 71.03% at 10-shot and 69.35% → 71.14% at 20-shot). These results indicate that Stage-1 base training followed by Stage-2 few-shot adaptation, together with selectively freezing visual LoRA modules and partially fine-tuning the detection head, effectively protects and even refines the base-class representations while allowing the model to better absorb the sparse novel-class data.

Second, the overall mAP () of the two-stage strategy consistently surpasses that of Joint Training for all -shot configurations. The gains are relatively stable, around +2.6 to +3.0 points (e.g., 58.17% → 61.03% at 3-shot, 60.90% → 63.85% at 10-shot, and 61.81% → 64.41% at 20-shot). This reflects a more favorable balance between base and novel performance: Joint Training, which updates all modules on mixed base and novel data in a single stage, tends to underfit novel classes (especially at low shot) and risks mild forgetting on base classes as training proceeds. In contrast, the two-stage scheme leverages knowledge distillation and semantic consistency losses in Stage 2 to regularize the adaptation process, enabling the cross-modal Qwen3-VL backbone to integrate novel-class semantics without sacrificing, and in some cases improving, base-class detection. Overall, these findings validate the effectiveness of the proposed two-stage fine-tuning strategy for FSOD in RS scenes.

4.4.3. Effect of Stage-2 Freezing Strategies

We analyze the Stage-2 freezing strategy in our two-stage framework. In Stage 2, we keep the partial detection head fine-tuning and all losses unchanged and only vary which LoRA branch is updated. We compare three settings:

- Freeze Text + Train Visual: freeze text LoRA and update visual LoRA in Stage 2.

- Update Both: update both visual and text LoRA in Stage 2.

- Freeze Visual + Train Text (ours): freeze visual LoRA and update text LoRA in Stage 2.

Table 7 reports the ablation results of different Stage-2 freezing strategies under Class Split 1 on DIOR. Overall, enabling visual LoRA updates in Stage 2 leads to pronounced base-class forgetting, and consequently a worse overall trade-off, while our strategy (Freeze Visual + Train Text) achieves the best overall performance across all -shot settings.

Table 7.

Effect of Stage-2 freezing strategies on FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) under Class Split 1 on DIOR for different -shot settings. The best results are highlighted in bold.

First, training visual LoRA in Stage 2 consistently degrades base mAP. Compared with our strategy, Freeze Text + Train Visual reduces base mAP from 69.73/69.31/71.03/71.14 to 64.52/64.49/64.56/64.36 at 3/5/10/20-shot, i.e., drops of −5.21/−4.82/−6.47/−6.78. Similarly, Update Both further lowers base mAP to 64.31/63.86/63.98/63.52, corresponding to −5.42/−5.45/−7.05/−7.62 relative to ours. This clearly indicates that updating the visual branch during few-shot adaptation tends to overwrite Stage-1 knowledge and causes significant forgetting on base categories.

Second, while updating visual LoRA can yield slightly higher novel mAP in some settings (e.g., at 10-shot: 43.24 vs. 42.31, and at 20-shot: 45.68 vs. 44.21), these gains are small and inconsistent, and they come at the cost of a much larger drop in base mAP. As a result, the overall mAP (All) is substantially worse when training visual LoRA. In particular, our strategy achieves 61.03/61.17/63.85/64.41 All mAP at 3/5/10/20-shot, outperforming Freeze Text + Train Visual by +3.94/+3.49/+4.76/+4.86, and Update Both by +3.93/+3.86/+5.06/+5.35, respectively.

Overall, these results validate our design choice: Stage-2 training of visual LoRA causes large base-class forgetting, whereas freezing visual LoRA and updating text LoRA provides a better balance between preserving base performance and adapting to novel classes, leading to the best overall FSOD performance.

4.4.4. Effect of LoRA Rank

Finally, we investigate the influence of the LoRA rank on performance and parameter efficiency. We evaluate while keeping all other hyperparameters fixed. For each rank, we measure the total number of trainable parameters (LoRA + detection head) and the corresponding base/novel mAP.

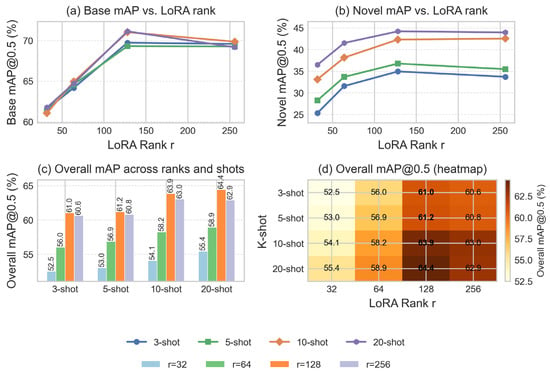

Table 8 summarizes the impact of the LoRA rank on few-shot detection performance under Class Split 1 on DIOR, and Figure 7 provides a visual illustration of these trends. Overall, increasing the rank from 32 to 128 consistently improves both base and novel mAP across all -shot settings, whereas further increasing the rank to 256 brings marginal or no gains and sometimes slightly degrades performance.

Table 8.

Effect of LoRA rank on FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) under Class Split 1 on DIOR across different -shot settings. The best results are highlighted in bold.

Figure 7.

Effect of the LoRA rank on FSOD performance (mAP@0.5) under Class Split 1 on DIOR across different -shot settings. (a) Base mAP@0.5 vs. LoRA rank. (b) Novel mAP@0.5 vs. LoRA rank. (c) Overall mAP@0.5 (“All”) across different combinations of LoRA rank and -shot. (d) Heatmap of overall mAP@0.5, where rows and columns denote the -shot setting and LoRA rank , respectively.

At the low-rank setting (), the model shows clear capacity limitations: both base and novel mAP are noticeably lower than those of higher-rank configurations. For example, at 10-shot, base/novel/overall mAP are 61.05%/33.12%/54.07%, which are significantly below the corresponding values at and . Increasing the rank to yields substantial improvements, especially on novel classes. At 3-shot, novel mAP improves from 25.32% to 31.56% (+6.24), and overall mAP rises from 52.49% to 56.02% (+3.53). Similar trends are observed at 5/10/20-shot, indicating that a moderate increase in LoRA capacity allows the model to better leverage hierarchical prompts and scarce novel-class examples.

Further increasing the rank to brings consistent and often the best performance across all -shot settings. For instance, at 20-shot, achieves 71.14% base mAP and 44.21% novel mAP, leading to the highest overall mAP of 64.41%, compared with 58.92% at and 55.42% at . The gains from to are smaller than those from to , but still clear (e.g., +4.17 novel mAP and +5.61 overall mAP at 10-shot), suggesting that provides a good balance between representational capacity and effective adaptation.

When the rank is further increased to , performance tends to saturate and even slightly decline in terms of overall mAP, despite the significant growth in trainable parameters. For example, at 3/5/20-shot, overall mAP at (60.62%, 60.82%, 62.87%) is slightly lower than at (61.03%, 61.17%, 64.41%). Novel mAP also shows small fluctuations (e.g., 34.94% → 33.71% at 3-shot and 44.21% → 43.95% at 20-shot). These patterns indicate diminishing returns and a potential risk of overfitting when the LoRA subspace is overly large under the current few-shot data scale.

Taken together, these results show that the LoRA rank has a non-trivial effect on few-shot performance: too small a rank () underfits, while an excessively large rank () offers limited benefits relative to its parameter cost. Medium ranks, especially (and to a lesser extent ), strike a favorable trade-off between parameter efficiency and detection accuracy, and are thus preferable choices for the proposed Qwen3-VL-based few-shot detection framework.

4.5. Efficiency and Computational Cost Analysis

To complement the accuracy evaluation, we further analyze efficiency and computational cost. Following common practice, we report three indicators—Params, FLOPs, and FPS—and compare our method with two representative RS-FSOD baselines that follow different paradigms: Meta-RCNN [70], a typical meta-learning approach, and RIFR [49], a representative fine-tuning strategy.

All experiments are conducted on the NWPU VHR-10.v2 dataset using a workstation equipped with two NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada GPUs. For a fair comparison, all methods are evaluated under the same input resolution (400 × 400) and the same testing pipeline. Specifically, FPS is measured end-to-end and includes post-processing. The results are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Efficiency and computational cost comparison.

As shown in Table 9, Meta-RCNN [70] and RIFR [49] adopt a ResNet-101 backbone and thus achieve relatively lower computational cost and higher inference speed. In contrast, our method employs the Qwen3-VL-8B multimodal backbone, resulting in a substantially larger model scale (8.2B) and higher FLOPs (993.74), which leads to a lower FPS (1.57). This difference reflects a typical trade-off between representation capacity and runtime efficiency when moving from conventional CNN-based backbones to large-scale multimodal foundation models.

Importantly, the increased cost is not merely a “heavier backbone” choice; it is also tied to the capabilities introduced by our design. By leveraging a strong multimodal encoder, our model can align visual regions with language-level semantics and exploit richer prior knowledge, which is particularly beneficial for few-shot recognition of novel categories in remote sensing imagery. Moreover, our training strategy adopts parameter-efficient adaptation (e.g., LoRA) instead of full fine-tuning, which reduces the number of trainable parameters and makes training more feasible despite the large backbone.

Overall, we include these metrics to explicitly present the accuracy–efficiency trade-off and to facilitate a more comprehensive comparison across methods with different backbone capacities. Future work will focus on improving inference efficiency while preserving the benefits of multimodal representations for RS-FSOD.

5. Discussion

5.1. Mechanism Analysis

From a cross-modal knowledge transfer perspective, LVLMs such as Qwen3-VL provide a strong semantic prior for FSOD. Pretrained on massive image-text pairs, they encode rich knowledge about object appearance, context, and attributes that cannot be learned from a handful of annotated RS images. In our framework, this prior is injected through the text encoder and prompts, so the detector starts from a semantically informed initialization rather than learning categories purely from sparse visual examples.

The proposed two-stage LoRA-based fine-tuning further structures this transfer. Stage 1 adapts both vision- and text-side LoRA modules to the RS domain and base-class taxonomy, anchoring cross-modal features to aerial viewpoints and cluttered backgrounds. Stage 2 then freezes the visual LoRA modules and updates the text-side LoRA together, while partially fine-tuning the detection head under knowledge distillation and semantic consistency losses. The ablation on two-stage strategies shows that this design consistently improves novel mAP while maintaining or slightly boosting base mAP compared with Joint Training, indicating that selective updates and distillation are effective in preserving base knowledge and focusing adaptation on new categories.

Hierarchical prompting provides an additional, empirically validated mechanism for shaping decision boundaries. Compared with No Prompt or a single generic instruction, the three-level prompts—task-level instruction, global remote sensing context, and fine-grained category descriptions—yield large gains in novel and overall mAP. This multi-granularity guidance structures the label space and encourages the model to separate visually similar categories (e.g., storage tank vs. stadium, basketball court vs. tennis court, baseball field vs. ground track field) by exploiting semantic differences, which is particularly beneficial under few-shot supervision.

The LoRA rank ablation further clarifies the capacity-efficiency trade-off. Increasing the rank from 32 to 64 and 128 steadily improves both base and novel mAP, while a too-small rank underfits and a too-large rank (256) brings diminishing returns or slight degradation despite more parameters. This suggests that a medium rank (128) is sufficient to capture the task-relevant variations when combined with hierarchical prompts and the two-stage scheme.

5.2. Performance on Specific Classes

On both DIOR (20 classes) and NWPU VHR-10.v2 (10 classes), the class-wise results are consistent with our mechanism analysis. Categories with distinctive geometric structures and relatively stable contextual cues—such as storage tank, tennis court, baseball/basketball court, ground track field, and airport—benefit the most from cross-modal priors and hierarchical prompts. These objects typically exhibit clear man-made layouts (e.g., circles, rectangles, runways, and track-field rings) and often appear in predictable surroundings. Leveraging the LVLM’s pretrained knowledge of such facilities, together with prompts that emphasize shape, function, and typical context, enables the model to align sparse remote-sensing evidence with rich semantic prototypes, leading to notable AP gains over purely visual FSOD baselines.

By contrast, categories characterized by extreme scale variation, heavy clutter, and ambiguous appearance—such as small vehicles in dense urban traffic, ships in complex harbor scenes, and building-like structures (e.g., overpass, bridge, chimney, and windmill) under diverse viewpoints—show more modest improvements. In these cases, high-level semantics (e.g., “ship on water” or “vehicle on road”) are less effective when targets are extremely small, densely packed, or heavily occluded. Moreover, label noise and imperfect bounding box annotations in existing datasets can further reduce the benefits of semantic guidance, especially under -shot supervision.

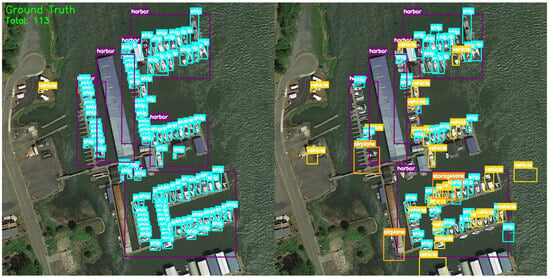

To provide a balanced view, we further present a representative failure case in an ultra-dense harbor scene in Figure 8, where the left panel shows the ground truth and the right panel shows our predictions. Although harbor-related categories with stable context can improve on average, object detection in extremely crowded port areas—especially for ships—remains challenging. In this example, the image contains 113 ground-truth instances in total, while our method detects 71 objects, resulting in 49 missed detections (43.4%). We also observe 20 misclassifications (17.7%), 20 localization errors (17.7%), and 7 false positives, with only 28 correct detections (24.8%). These errors are mainly caused by severe crowding and occlusion, as well as strong appearance similarity among ships and between ships and surrounding port structures (e.g., docks and container stacks), which makes it difficult to separate adjacent instances and accurately localize object boundaries under limited supervision. Overall, while cross-modal priors and hierarchical prompting substantially benefit many typical RS categories, the remaining gains are still bounded by target visibility, background confusion, annotation quality, and extreme appearance variations in challenging scenes.

Figure 8.

Qualitative failure cases in an ultra-dense harbor scene. The (left) panel shows the ground-truth annotations and the (right) panel shows the predictions of our method. Severe crowding and occlusion lead to frequent missed detections, misclassifications, and localization errors for ships in complex port backgrounds.

5.3. Limitations

Despite promising results, our approach has several limitations. First, the inference cost is non-trivial, especially for Qwen3-VL-8B on high-resolution RS images: large inputs and long prompts increase latency and memory usage, which may hinder deployment in real-time or resource-constrained scenarios. Second, efficient training currently assumes relatively strong hardware; the benefits of LVLM-based FSOD on much smaller models are less clear without careful tuning. Third, the design of hierarchical prompts still relies on human expertise, and the LVLM’s semantic space is not perfectly aligned with RS taxonomies, so some categories remain challenging despite careful prompt engineering.

These limitations suggest several directions for future work. One promising direction is automated prompt optimization (e.g., prompt tuning, prefix tuning, or instruction tuning on RS corpora) to reduce manual effort and improve robustness across datasets. Another is to develop more lightweight LVLMs or hybrid architectures tailored to overhead imagery that combine strong semantics with compact visual backbones. Finally, knowledge distillation from LVLM-based detectors to purely visual, task-specific models is a natural next step to retain most of the semantic benefits while substantially reducing inference cost and improving deployability.

6. Conclusions

We presented an LVLM-based framework for FSOD in RS, built on the Qwen3-VL model. The framework combines a two-stage LoRA fine-tuning strategy with hierarchical prompting to better exploit cross-modal knowledge learned during large-scale vision-language pretraining. Stage 1 adapts the model to the RS domain and base classes; Stage 2 performs parameter-efficient few-shot adaptation on novel classes with selective LoRA updates, knowledge distillation, and semantic consistency constraints. Hierarchical prompts provide multi-granularity semantic guidance—task instruction, global remote sensing context, and fine-grained category descriptions—while an appropriate LoRA rank ensures a good balance between capacity and efficiency.

Extensive experiments on DIOR and NWPU VHR-10.v2 show that our method consistently improves novel-class mAP over state-of-the-art few-shot detectors while maintaining strong base-class performance and transferring well across datasets. Ablation studies on prompting, two-stage strategies, and LoRA rank support our design choices and clarify how each component contributes to the final performance. Future work will focus on more efficient distillation to lightweight visual detectors and on automatic prompt optimization to further reduce manual effort and enhance robustness in diverse RS scenarios.

Author Contributions