Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The ruptured fault is dominated by normal faulting with a minor strike-slip component, and the maximum slip is up to 3.97 m.

- The postseismic deformation characteristics of the fault are basically consistent with those in the coseismic stage.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The results enhance the understanding of the rupture characteristics of the Xainza–Dinggye fault zone and provide new insights into seismic activity in complex terrain.

- The postseismic analysis provides valuable insights into the continuous deformation behavior of the fault after the earthquake.

Abstract

On 7 January 2025, an Mw 7.0 earthquake struck Dingri County, Shigatse, Tibet. This was the largest event in the region in recent years. Analysis of the Dingri earthquake is urgent for understanding the coseismic slip and early postseismic deformation characteristics. In this study, the coseismic characteristics were analyzed by using Lutan-1 and Sentinel-1 data with the Differential Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar method, and then the Okada elastic half-space dislocation model was used to invert the coseismic slip distribution of the seismogenic fault. The postseismic characteristics were analyzed by Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits, then time-series deformation results were obtained with the Small Baseline Subset InSAR method. The main results are as follows: (1) The maximum coseismic subsidence is −2.03 m and the maximum coseismic uplift is 0.68 m, the coseismic deformation is concentrated on the west side of the new rupture trace generated by the coseismic events; (2) the ruptured fault is dominated by normal faulting with a minor strike-slip component, and the slip is mainly distributed at depths of 0–15 km, with a maximum slip of about 3.97 m; (3) the deformation characteristics of the fault in the postseismic stage are basically consistent with those during the coseismic stage. The research results play an important role in understanding the earthquake fault tectonic activities.

1. Introduction

Earthquakes are one of the most destructive natural disasters on Earth, with more than 5 million occurring every year, most of which were minor in moment magnitude (Mw). Only a small proportion of earthquakes (typically Mw ≥ 6.5) result in substantial surface deformation and destructive impacts [1,2], causing incalculable losses [3]. Since the beginning of the 21st century, earthquake disasters have become increasingly frequent and severe [4]. Conducting research on earthquakes has become crucial. Since the Cenozoic period, the Indian Plate has continued to collide with and subduct beneath the Eurasian Plate, triggering significant surface deformation and geological responses, exerting a profound influence on seismic activity and crustal stability in the Tibetan Plateau region [5].

Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR), as a core technique for high precision and wide area monitoring of surface deformation, offers the advantages of strong microwave penetration, stable revisit cycles, and high spatial resolution [6]. InSAR technology can rapidly obtain the coseismic deformation field caused by an earthquake, and can track long-term postseismic deformation processes in a time series [7,8]. On 3 April 2014, the European Space Agency launched a radar Earth observation satellite through the Copernicus program. This has greatly promoted the application of technologies such as InSAR in surface deformation monitoring [9]. With the successful launch and operation of China’s Lutan-1 satellites on 27 February 2022, the data source system of InSAR technology has been further enriched [10]. On 7 January 2025, an Mw 7.0 earthquake occurred in Dingri County, Shigatse, Xizang Autonomous Region. This was the largest event in the region in recent years; the epicenter was located at 28.5°N, 87.45°E, and the focal depth was about 10 km [11]. This earthquake caused 126 fatalities, about 61,500 injuries, extensive building damage, and significant seismic damage effects [12,13].

A number of recent investigations have utilized InSAR datasets to analyze the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake, with emphasis on coseismic deformation fields, fault geometry, and stress evolution. These studies have laid the foundation for understanding the immediate tectonic response, yet postseismic deformation remains insufficiently explored. Based on Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits using Differential Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (D-InSAR), Yu et al. [14] obtained the line-of-sight (LOS) coseismic deformation field of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake, and combined the slip distribution to calculate Coulomb stress changes at different depths. Based on Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits and Lutan-1 data combined with strong motion records, Liu et al. [15] obtained the coseismic surface deformation and slip distribution using D-InSAR, and investigated the relationships among the coseismic slip distribution, aftershocks, surface rupture, and the seismogenic structure. Qiao et al. [16] proposed that the seismogenic structure consists of two conjugate normal faults forming a newly developed graben within the Xainza–Dinggye fault zone. Their analysis was based on Lutan-1 and Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits data, combined with D-InSAR and pixel offset tracking (POT), to derive the coseismic deformation field of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake, and inversion parameter results using the steepest descent method. Li et al. [17] interpreted the coseismic deformation field of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake based on Sentinel-1 descending orbit data and Lutan-1 data, inverted the focal mechanism parameters using the Okada model, and analyzed the coseismic Coulomb stress changes. Based on Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits data and GNSS data, Yu et al. [18] applied the InSAR stacking method to obtain the interseismic three-dimensional deformation field, derived the coseismic deformation field using D-InSAR and POT, and inverted a static fault slip model.

Therefore, this study uses Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits data and Lutan-1 ascending orbit data to investigate the coseismic slip and postseismic deformation characteristics of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake. Three experiments were performed: (1) The coseismic deformation of this earthquake was processed using D-InSAR, obtaining the LOS deformation field of the study area; (2) based on the Okada model, geometric parameter inversion and slip distribution inversion of the seismogenic fault were performed; (3) the postseismic Sentinel-1 time-series data were processed using the Small Baseline Subset Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (SBAS-InSAR) method, and the postseismic deformation characteristics of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake was analyzed. Lutan-1 data were not used for the analysis of the postseismic deformation mainly due to data availability limitations. Unlike Sentinel-1 data, which are openly and continuously available, Lutan-1 SAR data are not freely accessible and must be obtained through a formal application process. At present, only the coseismic Lutan-1 data have been publicly released through the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (TPDC) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home, accessed on 25 July 2025). No systematic postseismic Lutan-1 time-series data are currently available for this event.

2. Study Area and Data Sources

2.1. Geological Background of the Study Area

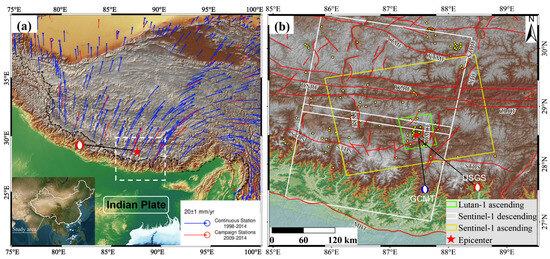

The epicenter of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake lies deep within the core of the Lhasa terrane on the Tibetan Plateau, as the direct stress-bearing zone of the continent–continent collision between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate. The regional tectonic dynamic environment exhibits complexity characterized by multi-sphere coupling under the long-term drive of a persistent compressive stress field [5]. The intense convergence between plates not only drives the eastward extrusion of crustal material along major strike-slip fault zones and differential vertical uplift, but also, through deep mantle material transport and crustal thickening, markedly accelerates tectonic and geomorphic evolution within the terrane, and seismicity exhibits high-frequency characteristics of spatial clustering and temporal periodicity [19]. Based on the modern GPS velocity field (Figure 1a), the Tibetan Plateau is being continuously compressed northward, while experiencing east–west extension, generating a tensional stress regime, and forming a series of nearly north–south striking fault zones within the plateau, especially in southern Tibet. The main fault zones include the Southern Tibetan Detachment System (STDS), the Xainza–Dinggye Fault (XDF), the Tangra Yumco–Kongco Fault (TYKF), and the Yarlung–Zangbo River Fault (YZRF). The STDS is an east–west striking extensional detachment, and the YZRF is an east–west trending structure associated with regional thrusting and compressional deformation.

In the interior of the Tibetan Plateau, a series of near-north–south-striking normal faults and extensional rift systems are commonly developed. Among them, the XDF is located in the south-central Tibetan Plateau, approximately 50 km north of the STDS. It extends northward into the central Qiangtang Plateau. Bounded by the YZRF and the STDS, the north–south striking normal fault system can be divided into northern, central, and southern segments (Figure 1b). Although these segments differ in fault geometry, they together constitute a coherent extensional tectonic system, forming a continuous, elongated negative landform in terms of geomorphology [20,21].

The epicenter of the 7 January 2025 Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake is located near the junction between the southern segment of the XDF and the STDS. The fault closest to the epicenter is the Dengmecuo Fault (DMCF). The DMCF represents the main boundary fault along the eastern margin of the Dengmecuo graben and has exhibited pronounced activity since the 2015 Nepal earthquake, during which multiple earthquakes with magnitudes greater than Mw 5 have occurred [22]. These faults are dominated by normal faulting, which is consistent with the regional extensional tectonic regime [17]. This complex superimposed tectonic effect provided specific conditions conducive to the occurrence of the Dingri earthquake.

Figure 1.

Tectonic setting of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake. (a) The plate tectonics and GPS velocity field of the study area. The blue arrows are from continuous GPS stations during 1998–2014, and the red arrows are from campaign GPS data during 2009–2014. The GPS data are from Zhao et al. [23]. The white dashed box indicates the study area of the Dingri earthquake, and the red star marks the epicenter of this earthquake. (b) The distribution of faults near the epicenter and the radar satellite orbits. The white rectangle denotes the area covered by Sentinel-1 descending orbit images, the yellow rectangle denotes the area covered by Sentinel-1 ascending orbit images, and the green rectangle denotes the area covered by Lutan-1 ascending orbit images. The yellow circles show earthquakes with 5.0 ≤ Ms ≤ 7.9 that have occurred in the study area since 2012, from the China Earthquake Network Center (CENC). The red solid lines are the known faults in the study area, from Wu et al. [24]. The red focal spheres represent the source mechanisms provided by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The blue focal spheres represent the source mechanisms provided by the Global Centroid Moment Tensor (GCMT); both the focal mechanism solutions are consistent with N-S striking normal faulting. MBT—main boundary thrust; STDS—South Tibetan Detachment System; XDF—Xainza–Dinggye Fault; YZRF—Yarlung–Zangbo River Fault; TYKF—Tangra Yumco–Kongco Fault; XTMF—Xietongmen Rift; DMCF—Dengmecuo Fault; ZLQF—Zada–Lazi–Qiongdojiang Fault.

Figure 1.

Tectonic setting of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake. (a) The plate tectonics and GPS velocity field of the study area. The blue arrows are from continuous GPS stations during 1998–2014, and the red arrows are from campaign GPS data during 2009–2014. The GPS data are from Zhao et al. [23]. The white dashed box indicates the study area of the Dingri earthquake, and the red star marks the epicenter of this earthquake. (b) The distribution of faults near the epicenter and the radar satellite orbits. The white rectangle denotes the area covered by Sentinel-1 descending orbit images, the yellow rectangle denotes the area covered by Sentinel-1 ascending orbit images, and the green rectangle denotes the area covered by Lutan-1 ascending orbit images. The yellow circles show earthquakes with 5.0 ≤ Ms ≤ 7.9 that have occurred in the study area since 2012, from the China Earthquake Network Center (CENC). The red solid lines are the known faults in the study area, from Wu et al. [24]. The red focal spheres represent the source mechanisms provided by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The blue focal spheres represent the source mechanisms provided by the Global Centroid Moment Tensor (GCMT); both the focal mechanism solutions are consistent with N-S striking normal faulting. MBT—main boundary thrust; STDS—South Tibetan Detachment System; XDF—Xainza–Dinggye Fault; YZRF—Yarlung–Zangbo River Fault; TYKF—Tangra Yumco–Kongco Fault; XTMF—Xietongmen Rift; DMCF—Dengmecuo Fault; ZLQF—Zada–Lazi–Qiongdojiang Fault.

2.2. SAR Data Source

Sentinel-1 data come from the C-band synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite mission of the Copernicus program; its advantages are wide coverage and free access. The Sentinel-1 has a nominal revisit cycle of 12 days for a single satellite, which can be reduced to 6 days when operating as a constellation [25]; therefore, it is widely used in seismic deformation. Lutan-1 data come from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center of China, which has a nominal revisit cycle of 8 days for a single satellite, and can be reduced to 4 days when operating as a constellation [26,27]. Its L-band multi-polarization multi-channel SAR payload can more efficiently capture regions of coseismic signal decorrelation.

In the coseismic analysis, C-band Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits SAR data and L-band Lutan-1 ascending orbit SAR data covering the epicentral area were collected, and the selected Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits data were all VV polarization, among which the ascending orbit data had track number P12, the master image date was 5 January 2025, and the slave image date was 17 January 2025. The descending orbit data had track number P121, the master image date was 1 January 2025, and the slave image date was 13 January 2025. The Lutan-1 ascending orbit data were HH polarization, the master image date was 3 January 2025, and the slave image date was 7 January 2025.

In the postseismic analysis, 14 scenes of Sentinel-1 ascending orbit data and 14 scenes of Sentinel-1 descending orbit data were selected; the time span of the ascending orbit data was from 17 January 2025 to 22 June 2025, and the time span of the descending orbit data was from 13 January 2025 to 18 June 2025. Information on the SAR data is shown in Table 1, and the spatial coverage is shown in Figure 1b. All interferometric processing steps were first carried out in the SAR coordinate system.

Table 1.

Related SAR Data.

3. Coseismic Deformation Field

3.1. D-InSAR Data Processing

The D-InSAR data processing process of Sentinel-1 and Lutan-1 SAR images was completed using the SARscape 6.1 software in this study:

- (1)

- Orbital error correction. Because the Lutan-1 satellite has not yet publicly released precise orbit products, the initial interferograms contain significant orbital phase trend errors [28], manifested as linear or nonlinear phase slopes along the azimuth and range directions (Figure 2a), whereas for Sentinel-1 data, by using the Precise Orbit Data (POD) provided by the European Space Agency (ESA), the orbital errors can be suppressed to the centimeter level.

- (2)

- Topographic phase removal. Because the study area has large relief, the Copernicus DEM GLO-30 was introduced to remove the topographic phase during differential interferometry. The Copernicus DEM GLO-30 provides high-accuracy global digital surface model data for precise co-registration of SAR images and for correcting interferogram errors caused by topography [29].

- (3)

- Multilooking processing. Differentiated settings were applied according to the characteristics of different data sources. For Lutan-1 data, the range and azimuth multilook factors were set to 9:19 [17], which effectively suppresses phase noise while retaining range-direction spatial resolution. For Sentinel-1 data, the range and azimuth multilook factors were set to 10:2 [30], increasing the number of range looks to enhance phase stability and reducing the number of azimuth looks to preserve structural details, matching the imaging characteristics of its C-band sensor and the needs of regional deformation monitoring.

- (4)

- Filtering and phase unwrapping. The Sentinel-1 and Lutan-1 satellites uniformly use Goldstein filtering, which performs multi-scale smoothing on the interferogram to reduce speckle noise while preserving phase edge features. Phase unwrapping uniformly uses the Delaunay Minimum Cost Flow method (Delaunay MCF) [31], with the minimum unwrapping threshold set to 0.3 to ensure the reliability of unwrapping in low-coherence regions.

- (5)

- Atmospheric delay correction and geocoding. Atmospheric delay errors were mitigated by using General Atmospheric Correction Online Service (GACOS) data corresponding to the SAR acquisition times [32,33], effectively removing the influence of tropospheric delay on the interferometric phase. Coseismic InSAR processing was initially conducted in the SAR geometry (range–azimuth coordinate system). Finally, the interferometric results were geocoded using an external DEM and projected from the SAR coordinate system into the WGS84 geographic coordinate system, yielding LOS deformation maps in a common spatial reference frame and generating the coseismic deformation field data of the study area.

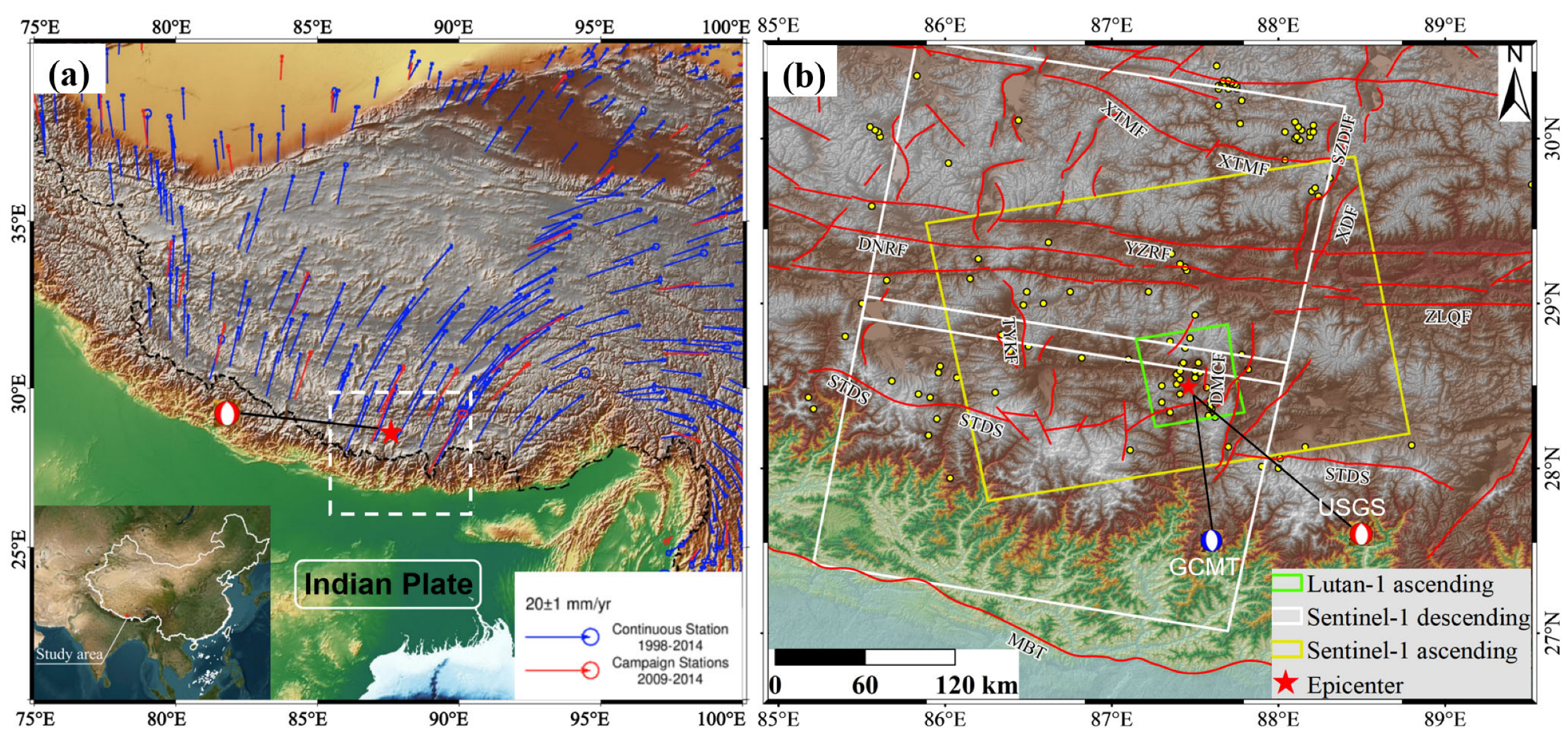

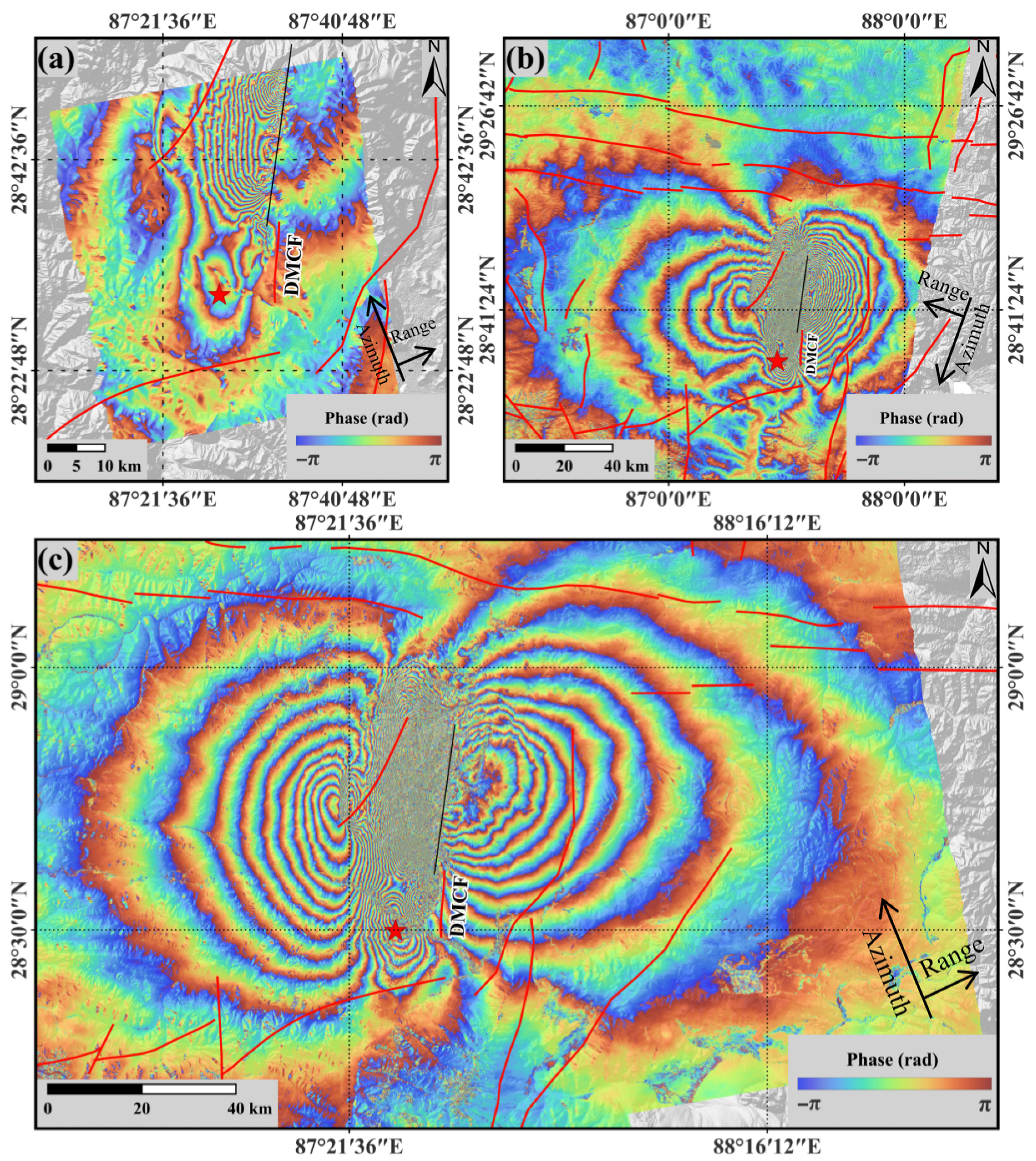

Figure 2.

Ascending and descending coseismic interferograms: (a) Lutan-1 ascending interferogram, (b) Sentinel-1 descending interferogram, (c) Sentinel-1 ascending interferogram. The red star marks the epicenter of this earthquake, the red solid lines indicate the known faults in the study area, and the black solid line is the rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms; both were delineated using the Lutan-1 ascending orbit interferogram.

Figure 2.

Ascending and descending coseismic interferograms: (a) Lutan-1 ascending interferogram, (b) Sentinel-1 descending interferogram, (c) Sentinel-1 ascending interferogram. The red star marks the epicenter of this earthquake, the red solid lines indicate the known faults in the study area, and the black solid line is the rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms; both were delineated using the Lutan-1 ascending orbit interferogram.

3.2. Coseismic Deformation Field

The coseismic differential interferograms obtained in this study are shown (Figure 2). The interferometric results derived from Sentinel-1 and Lutan-1 exhibit notable differences. Despite the varying coherence levels between the two sensors, both datasets clearly capture the deformation signals associated with the Dingri earthquake.

Overall, strong decorrelation is observed in the Sentinel-1 interferograms due to the large deformation gradients in the vicinity of the rupture zone. This area is mainly located on the western side of the DMCF, and the rupture trace was determined from the coseismic interferograms. The rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms represents a simplified surface rupture trace, which is primarily delineated based on the Lutan-1 ascending orbit interferogram [20]. In contrast, owing to the longer wavelength and higher coherence of the L-band data, the Lutan-1 interferograms preserve coherent fringes in these areas.

Specifically, the Sentinel-1 ascending and descending interferograms display a butterfly-like pattern, with coseismic fringes prominently distributed on both sides of the DMCF and the rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms. The fringe density increases as the distance to the fault decreases. The interferometric fringes are not perfectly symmetric, suggesting the presence of a minor strike-slip component during the earthquake (Figure 2a,b).

Benefiting from the longer L-band wavelength, the Lutan-1 interferograms exhibit generally good fringe clarity and continuity (Figure 2c). The number of coseismic fringes is significantly smaller than that observed in the Sentinel-1 results, and decorrelation is limited to a small meizoseismal area northwest of the DMCF. The main fringe pattern extends along a northeastward direction, and no clear interferometric fringes are observed on the eastern side of the rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms.

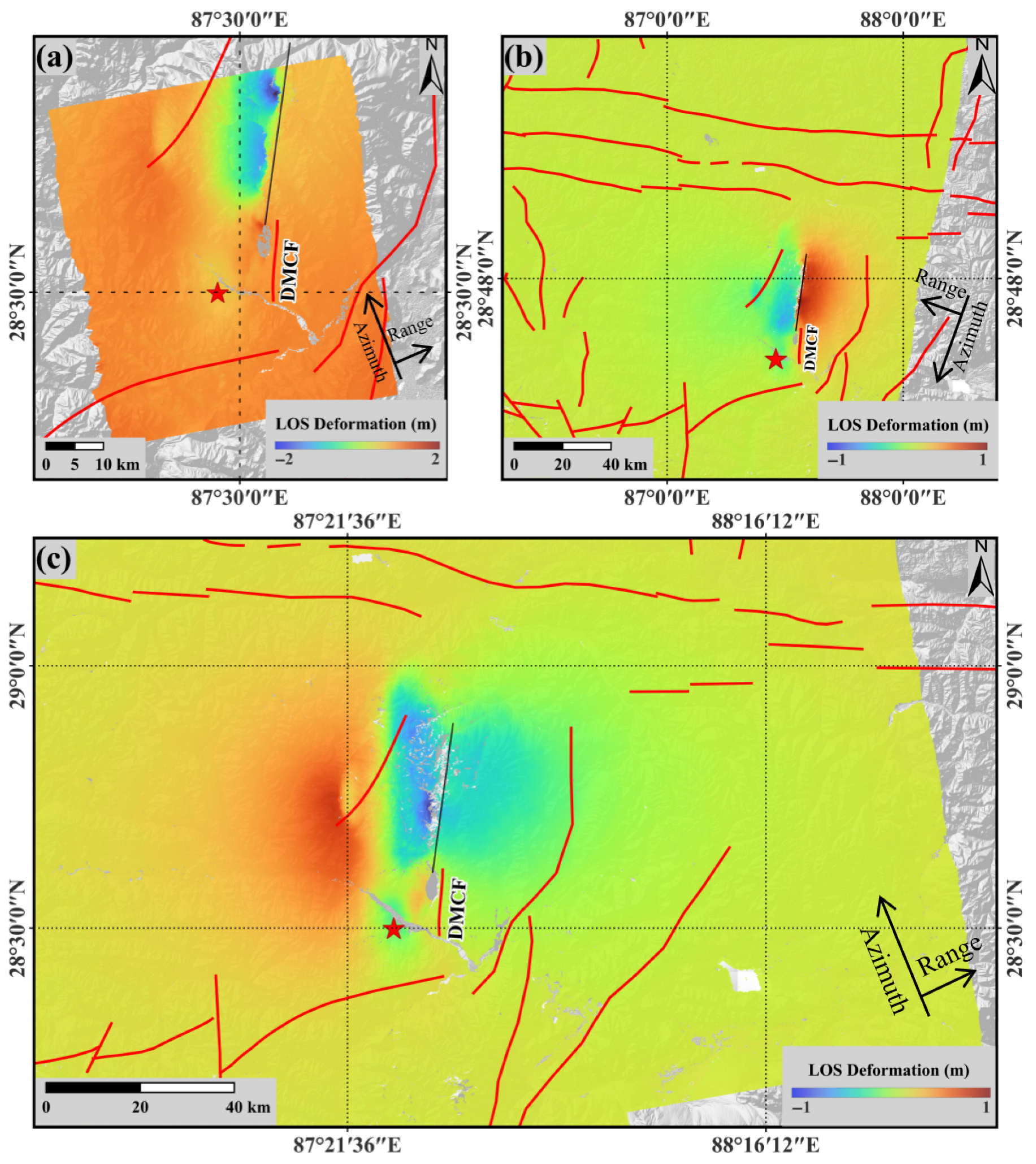

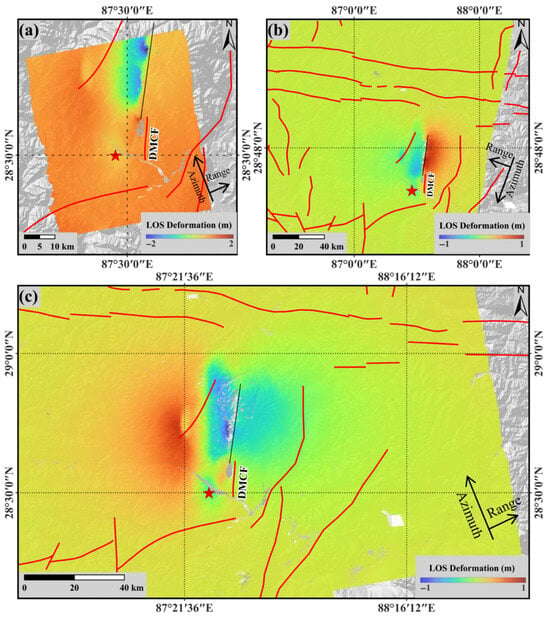

The coseismic deformation results are shown in Figure 3. The Lutan-1 ascending orbit result is dominated by LOS subsidence, which is mainly concentrated on the western side of the rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms, whereas the eastern side of the rupture trace exhibits weaker uplift deformation signals, with a maximum LOS subsidence of −2.03 m (Figure 3a). Sentinel-1 descending orbit observations show a maximum LOS subsidence of −0.93 m and a maximum LOS uplift of 0.74 m (Figure 3b). Sentinel-1 ascending orbit observations show a maximum LOS subsidence of −0.53 m and a maximum LOS uplift of 0.33 m (Figure 3c). The deformation pattern and magnitude of the coseismic observations are generally consistent with previous results [14,15,16,18], all showing that the coseismic deformation field exhibits LOS subsidence on the west side of the seismogenic fault, and that the subsidence in the Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits coseismic deformation fields is significantly greater than the uplift on the east side of the seismogenic fault. It is worth noting that the coseismic deformation obtained from the Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits in this study differs from that in Yu et al. [14] and Liu et al. [15], which is mainly because GACOS data were introduced in the processing stage for Sentinel-1, further removing the influence of atmospheric noise.

Figure 3.

Coseismic deformation fields for ascending and descending orbits: (a) Lutan-1 ascending deformation field, (b) Sentinel-1 descending deformation field, (c) Sentinel-1 ascending deformation field. The red star marks the epicenter of this earthquake, the red solid lines indicate the known faults in the study area, and the black solid line is the rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms.

The Lutan-1 ascending orbit and the Sentinel-1 descending orbit show deformation with the same LOS sign in the same area. Indicating that the surface displacement caused by this earthquake is dominated by a vertical component. The western side of the rupture trace exhibits subsidence, while the eastern side exhibits uplift; such deformation distribution identifies the hanging wall and footwall, respectively, of a west-dipping normal fault. These observations are in high agreement with the normal fault focal mechanism solution provided by the USGS. Therefore, the seismogenic fault is preliminarily identified as the DMCF.

The spatial distribution characteristics of the coseismic deformation field of the Dingri earthquake show partial differences in the data from Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits; the Sentinel-1 ascending orbit data indicate a significant LOS subsidence signal on the east side of the DMCF. This deformation characteristic is exactly opposite to the deformation observed in the Sentinel-1 descending orbit data in this area. This difference mainly arises from the different observation geometries of the Sentinel-1 satellite in ascending and descending orbits [30], which causes the same area of deformation to appear different from different observation angles. The coseismic deformation field is characterized by asymmetric LOS displacement across the fault, with subsidence dominating on the western side of the rupture trace and uplift occurring on the eastern side. Notably, the magnitude of LOS subsidence consistently exceeds that of uplift in both Lutan-1 and Sentinel-1 observations, indicating that subsidence on the western side represents the dominant coseismic deformation component. Although the deformation details show local differences between the two orbital datasets, both consistently reveal that the earthquake was a primarily LOS subsidence event.

4. Coseismic Slip Distribution Inversion

4.1. Inversion Methodology

The inversion of fault geometry parameters and slip distribution has significant scientific value for deepening the understanding of fault activity characteristics. Based on the coseismic deformation field obtained from the above D-InSAR technique, the Okada elastic half-space dislocation model [34] was used to invert the fault geometry parameters and slip distribution, and all operations were completed in SARscape 6.1 software. The main process is as follows:

- (1)

- Downsampling processing. To improve inversion efficiency and shorten computation time, the InSAR deformation field obtained previously was downsampled. After defining the sampling area, the sampling interval in the near-field region (deformation region of approximately 30 km of the rupture trace) was set to 500 m, while that in the far-field region (beyond the deformation region of approximately 30 km) was set to 2400 m. The Sentinel-1 descending orbit InSAR deformation field was downsampled, retaining 7320 deformation feature points.

- (2)

- Fault geometry parameter inversion. On this basis, the fault geometry parameters were inverted to determine the strike, length, width (along-dip extent), rake, and dip of the seismogenic fault. The initial source parameters were obtained from the GCMT, since two fault planes are provided in the GCMT solution. Plane 1 parameters are as follows: strike = 356°, dip = 42°, slip angle = −88°. Plane 2 parameters are as follows: strike = 173°, dip = 48°, slip angle = −92° (Table 2). Plane 2 was selected as the input considering the characteristics of this earthquake. The length of the seismogenic fault was set within 20–35 km, the width within 8–25 km, the strike range between −47° and −137°, and the dip range between 20° and 70°. The inversion was then performed within these parameter ranges based on the Okada model.

- (3)

- Slip distributed inversion. Based on the fault geometry obtained from the uniform slip inversion, a slip-distributed inversion was performed to obtain a more detailed fault slip. The rake and strike of the seismogenic fault model obtained in the previous step were fixed, then the fault was extended 75 km along strike and 36 km along dip, the fault plane was divided into 300 small rectangles of 3 km × 3 km, the damping factor was set to 0.01, and the coseismic slip distribution of the seismogenic fault was obtained.

Table 2.

Seismogenic fault parameters published by different institutions and scholars.

Table 2.

Seismogenic fault parameters published by different institutions and scholars.

| Scheme | Mw | Strike (°) | Dip (°) | Rake (°) | Maximum Sliding (m) | Earthquake Moment (N·m) | Sliding Depth (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCMT | Mw 7.1 | 356 | 42 | −88 | \ | 5.29 × | \ |

| 173 | 48 | −92 | |||||

| USGS | Mw 7.1 | 349 | 42 | −103 | \ | 4.749 × | \ |

| 187 | 49 | −78 | |||||

| Yu et al. [14] | Mw 7.1 | 189.02 | 40.6 | −82.81 | 4.6 | \ | 0–10 |

| Li et al. [17] | Mw 7.17 | 189.33 | 52.8 | −95.75 | 4.73 | 6.43 × | 0–14 |

| Zhang et al. [20] | Mw 7.0 | 185.03 | 60 | −76.81 | 4.45 | 3.53 × | 0–15 |

| This study | Mw 7.1 | 183.89 | 68 | −74.23 | 3.97 | 5.01 × | 0–15 |

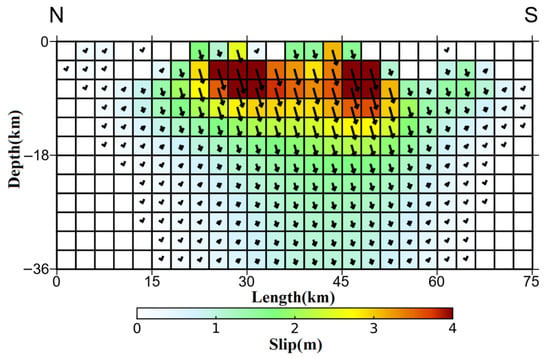

4.2. Coseismic Slip Distribution

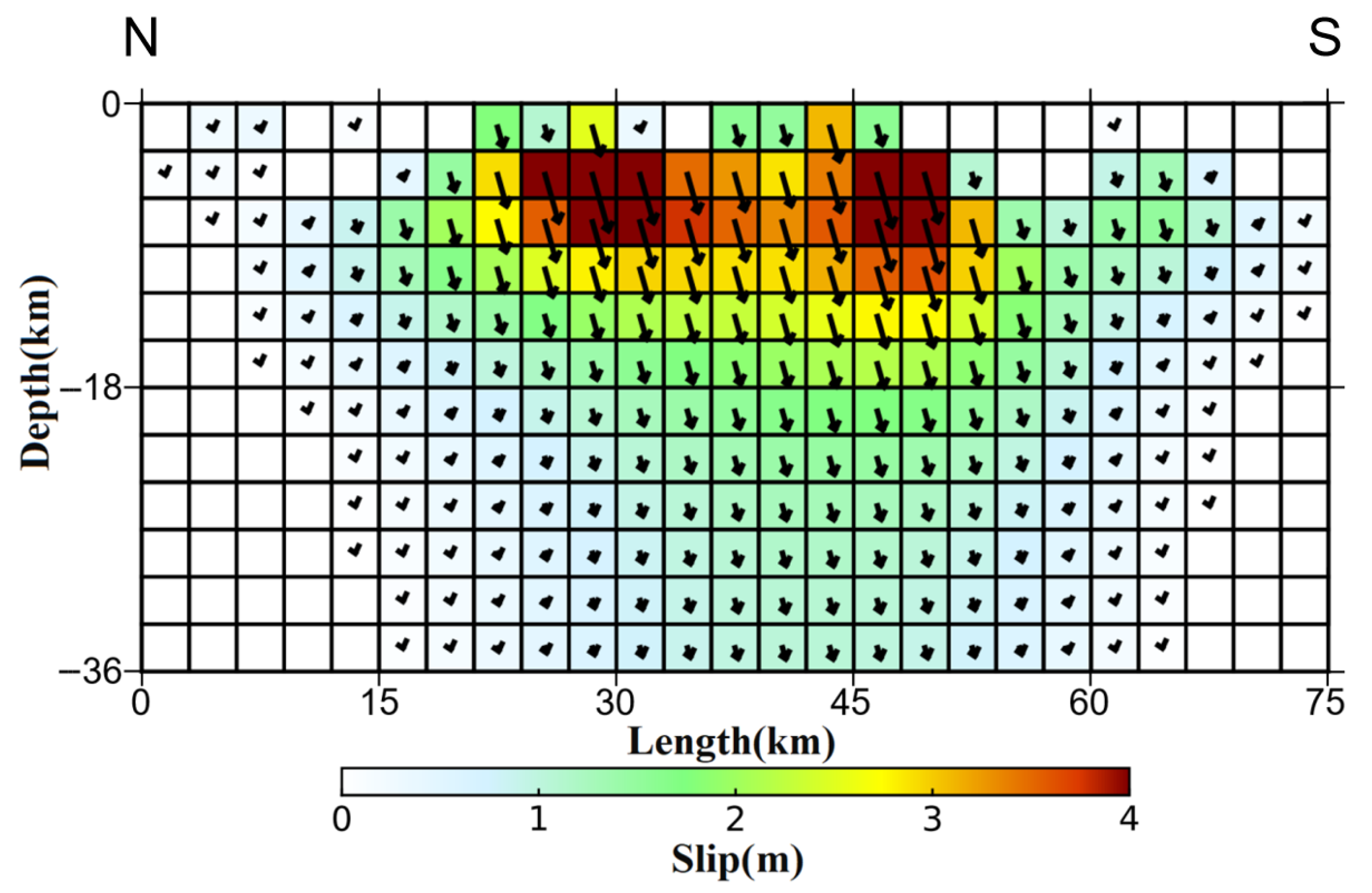

The obtained seismogenic fault parameters are shown in Table 2: the strike of the seismogenic fault is 183.89°, the fault dip is about 68°, which is a nearly north–south-striking fault. The maximum slip is about 3.97 m, the average rake is about −74.23°, between −90° and 0°. The seismic moment is calculated to be approximately 5.01 × 1019 N·m, corresponding to a moment magnitude of Mw 7.1.

The coseismic slip distribution is shown in Figure 4; the slip area of the seismogenic fault is distributed within a range of about 45 km in length and about 15 km in depth. The maximum slip is located at a depth of about 3–9 km on the seismogenic fault. From the slip direction of each of the small rectangular patches, it can be seen that this earthquake has a typical normal-faulting rupture, and it also contains a slight left-lateral strike-slip [20].

Figure 4.

Coseismic slip distribution map. The slip distribution map represents the hanging wall of the seismogenic fault. Red indicates areas with large slip magnitudes, while white indicates areas with zero slip. The left side of the seismogenic fault plane corresponds to the north direction, and the right side corresponds to the south direction. The seismogenic fault plane is discretized into several small rectangular segments, and the arrows indicate the slip direction and magnitude of each segment.

The inversion results of this study are close to the moment magnitudes given by USGS and GCMT, both consider that the main rupture type of this earthquake is north–south-striking normal faulting, and it is accompanied by a certain strike-slip component. These results provide a reliable basis for further in-depth research on the kinematic properties of the fault.

5. Postseismic Geodetic Observations

5.1. SBAS-InSAR Processing

The study area is located in a high-elevation region of the Tibetan Plateau, and the terrain is complex. Traditional InSAR processing in this region is prone to temporal decorrelation, which can significantly degrade the accuracy of inversion results [35]. To reduce the adverse effects of temporal decorrelation, this study adopted the SBAS-InSAR method for postseismic time-series coherence processing.

In the same research area, SAR images of multiple temporal phases are collected, one of which is selected as the main image. The other auxiliary images are registered and differentially interfered with the main image to obtain differential interference images [36], where satisfies the conditions shown in Formula (1):

The calculation formula for the deformation observation phase of the i-th interferogram at a pixel is given in Equation (2).

where the deformation observation phase of the i-th interferogram is denoted as ; and represent the cumulative surface displacements relative to the initial time at epochs and , respectively, with > ; denotes the topographic phase error; denotes the atmospheric phase error; denotes the orbital phase error; and is the radar wavelength.

The interferometric phases of the differential interferograms are expressed as an matrix, as shown in Equation (3).

where is an M × N matrix; is the average phase velocity; is the interferometric phase at the point (x, r).

Finally, the solution in the sense of the minimum norm is obtained using Single Value Decomposition (SVD), and the time-series deformation amount within the observation period is derived.

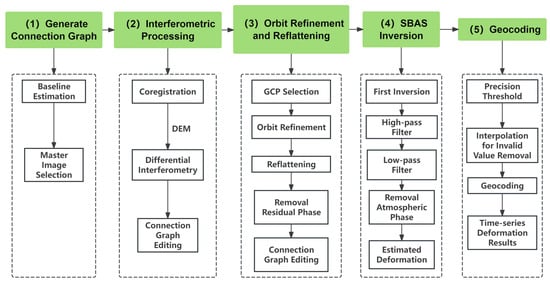

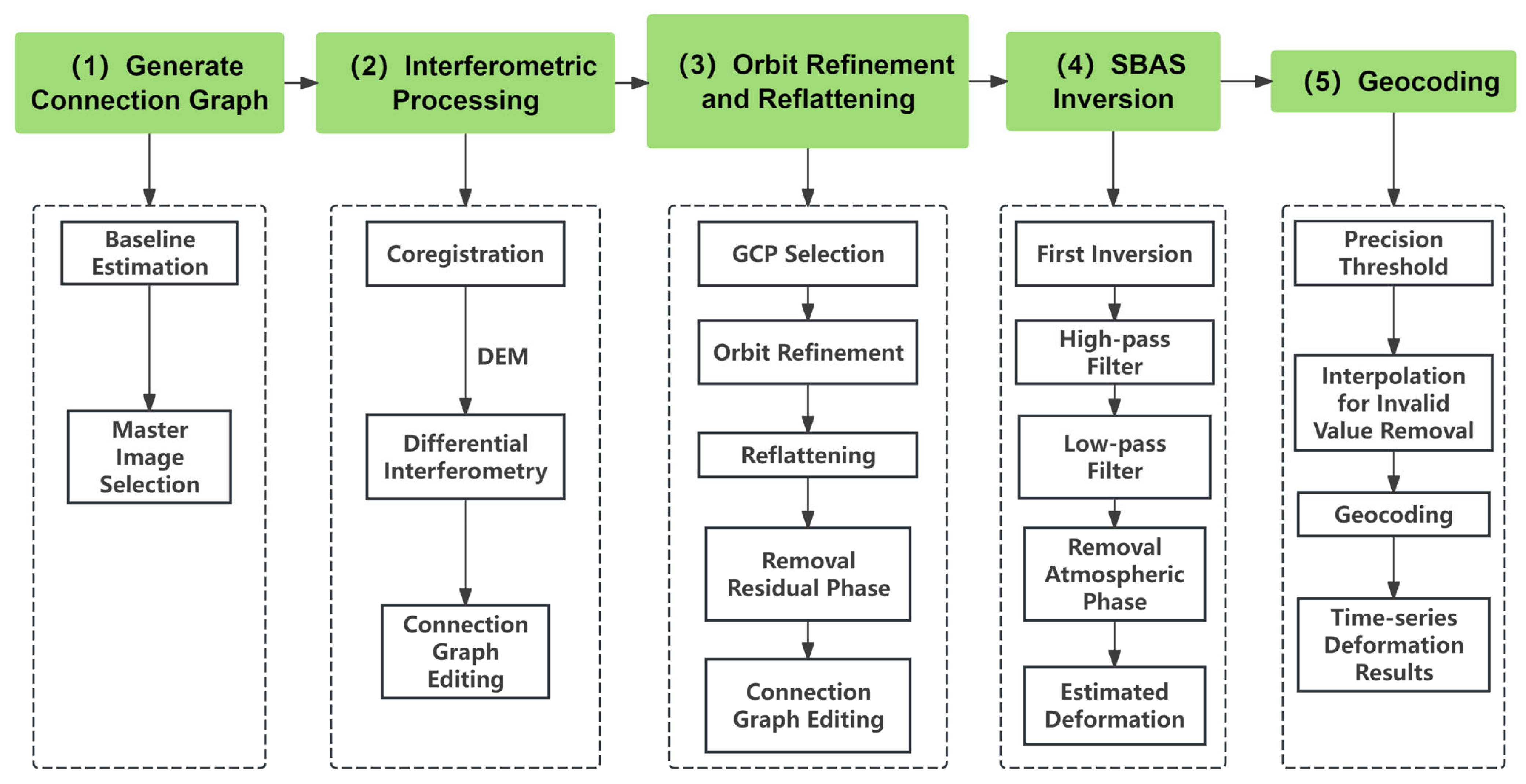

In this study, SAR images from Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits spanning from 13 January 2025 to 22 June 2025 were selected as the processing data. Combined with the Sarscape 6.1 software, the surface deformation data within the study area were obtained. The data processing workflow of the SBAS-InSAR method is shown in Figure 5. The implementation of the SBAS-InSAR method includes the following five steps:

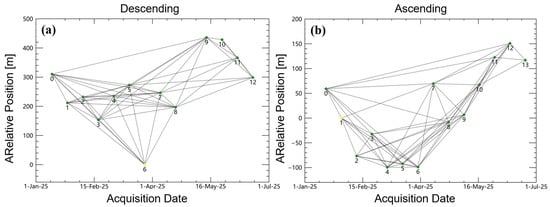

- (1)

- Connection graph generation. For the descending orbit data, the spatial baseline threshold and temporal baseline threshold were set to 50 m and 150 days, respectively, initially generating 77 interferometric pairs. For the ascending orbit data, the same baseline threshold parameters were used, obtaining 91 interferometric pairs. Multiple rounds of optimization were then applied to the initial interferometric pairs to remove pairs with overall low coherence and poor phase unwrapping, retaining only the valid data with high coherence and continuous unwrapping results. After screening with the criterion that each small-baseline subset retains at least five qualified observations, the Sentinel-1 descending orbit data finally retained 54 valid interferometric pairs (Figure 6a), and the ascending orbit data retained 63 valid interferometric pairs (Figure 6b).

- (2)

- Interference workflow: The topographic phase was removed using Copernicus DEM GLO-30 data [29], the noise phase was removed using Goldstein filtering, and the phase unwrapping was performed using the Delaunay MCF [31]. The unwrapping coherence coefficient threshold was set to 0.3.

- (3)

- Orbital refinement and reflattening: Select an appropriate number of Ground Control Points (GCPs) to remove the residual phase [37]. This study selects 30 GCPs for processing.

- (4)

- SBAS inversion: The first inversion estimates the residual topographic phase and performs the phase unwrapping on the differential interferogram. The second inversion conducts filtering in the spatial and temporal domains to estimate and remove the atmospheric delay phase [38], and finally obtains time-series deformation results.

- (5)

- Geocoding: Convert the SAR coordinates into ground deformation results under geographic coordinates. The DEM is used as a coordinate reference for generating LOS displacement in the GCS-WGS-84 coordinate system, which facilitates further spatial analysis.

Figure 5.

SBAS-InSAR processing workflow.

Figure 5.

SBAS-InSAR processing workflow.

Figure 6.

Optimized spatial baseline plots: (a) Sentinel-1 descending orbit spatial baseline, (b) Sentinel-1 ascending orbit spatial baseline. The green dots are the slave images, the yellow dots represent the super master images, and each line represents an interferometric pair. The numbered points (0–13) represent the time-series indices of each SAR image, where smaller numbers correspond to earlier acquisition dates and larger numbers correspond to later acquisition dates.

Figure 6.

Optimized spatial baseline plots: (a) Sentinel-1 descending orbit spatial baseline, (b) Sentinel-1 ascending orbit spatial baseline. The green dots are the slave images, the yellow dots represent the super master images, and each line represents an interferometric pair. The numbered points (0–13) represent the time-series indices of each SAR image, where smaller numbers correspond to earlier acquisition dates and larger numbers correspond to later acquisition dates.

5.2. Two-Dimensional (2-D) Postseismic Deformation Decomposing

Because this earthquake is dominated by normal faulting, obtaining vertical deformation data is crucial. InSAR measures the projection of the actual surface deformation between two acquisition times in the direction of the radar LOS. In addition, due to the near-polar flight characteristics of spaceborne radars, the monitoring capability of north–south deformation is weak, so the north–south component of LOS deformation is often ignored [39]. Therefore, it is necessary to combine the ascending and descending InSAR observation data to solve the vertical component and east–west component of the surface deformation field. According to the spatial observation geometry of the SAR satellite, we have the following:

where and are the unknowns of vertical and east–west surface deformation. The two equations need to be solved jointly; therefore, the ascending orbit LOS deformation is ; the descending orbit LOS deformation is ; , and , are the acquisition times of the four scenes for ascending and descending orbits, respectively; and are the incidence angles of the ascending and descending images; and and are the angles between the ascending and descending flight directions and geographic north [40]. Under the assumption that the acquisition times of the ascending and descending orbits data are the same, solving this system of equations yields the vertical and east–west deformation fields of the surface.

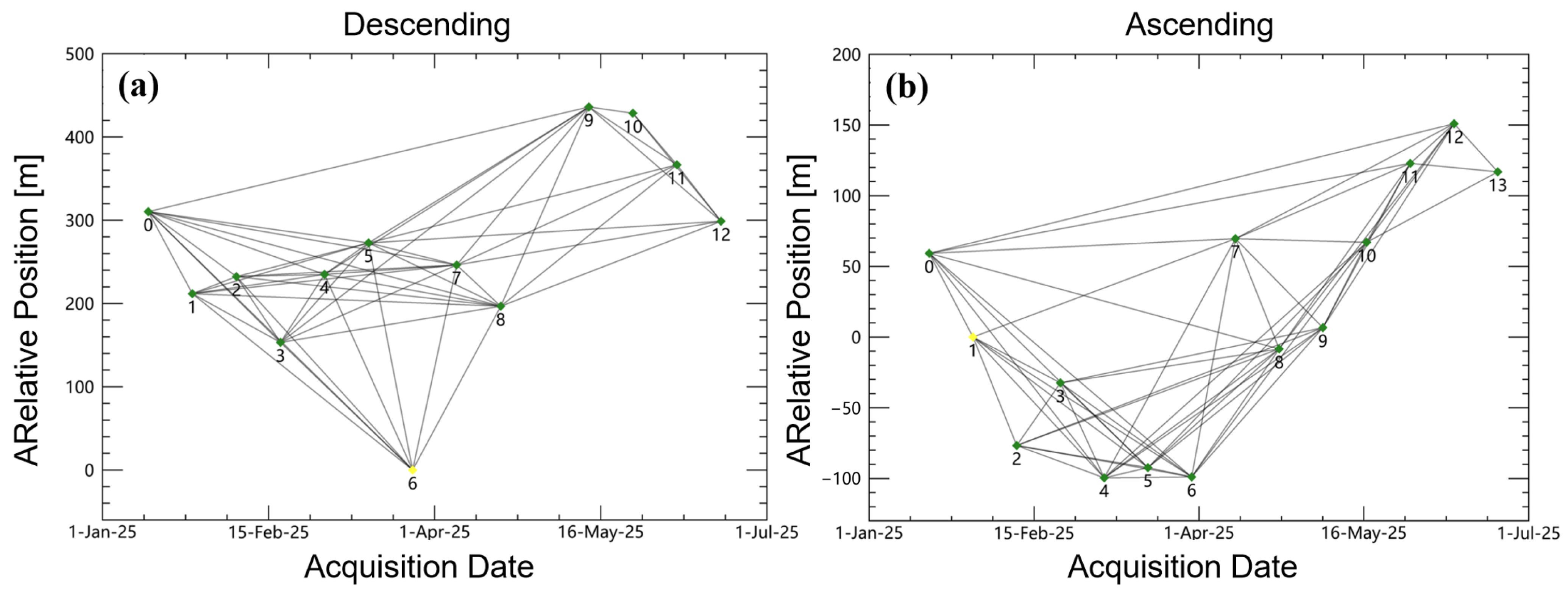

5.3. Early Postseismic Deformation Analysis

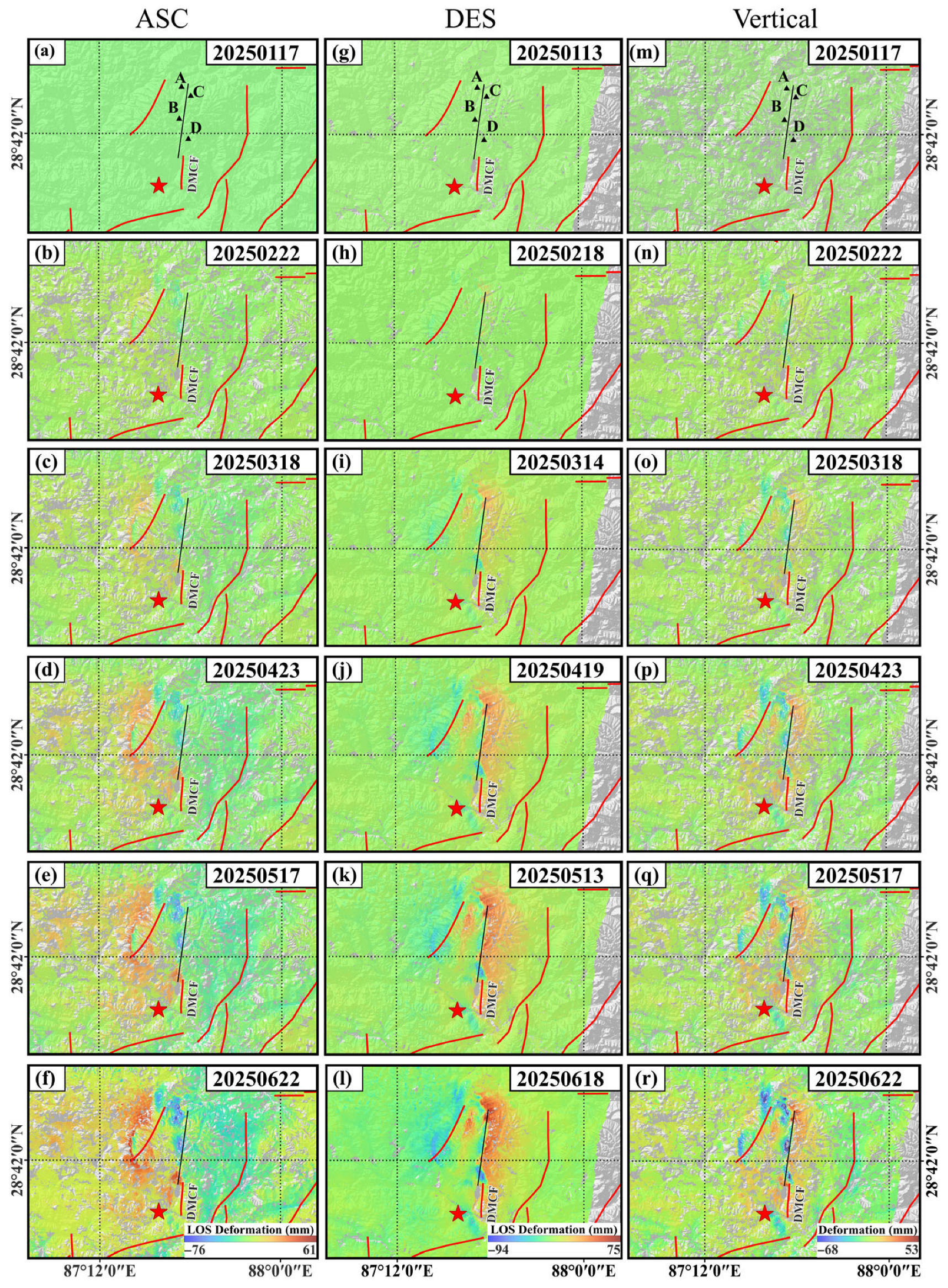

To better understand the postseismic deformation characteristics of the Dingri earthquake, this study, based on Sentinel-1 ascending and descending orbits data, plotted the LOS deformation time series from 13 January 2025 to 22 June 2025, and further solved for the vertical surface deformation results (Figure 7a–r). In the postseismic result, the main LOS subsidence and uplift are distributed along the strike of the fault trace. The vertical time-series deformation shows that subsidence is mainly distributed along the rupture trace on the hanging wall, whereas uplift is mainly distributed along the rupture trace on the footwall. In the past half year, the LOS deformation in the ascending orbit is −76 to 61 mm, in the descending orbit it is −94 to 75 mm, and the time-series results show a clear cumulative trend over time in the deforming areas. The vertical deformation obtained from the ascending–descending decomposition is mainly concentrated in −68 to 53 mm. In the far field of the fault, more than 60% of the area had surface deformation in the past half-year, concentrated in −10 to 10 mm. The postseismic deformation area and deformation magnitude obtained in this study are basically consistent with the results from Yang et al. [41]; the main difference is that the postseismic time period covered in this study is longer, and the final cumulative deformation is larger.

Figure 7.

Postseismic time-series deformation: (a–f) LOS time-series deformation of Sentinel-1 ascending orbit during the postseismic half-year, (g–l) LOS time-series deformation of Sentinel-1 descending orbit during the postseismic half-year, (m–r) vertical time-series deformation solved from the 2-D postseismic deformation decomposing during the half-year. Points A–D indicate the selected ascending and descending orbits deformation feature fitting points. The red pentagram marks the epicenter of this earthquake, the red solid lines indicate the known faults in the study area, and the black solid line is the rupture trace determined from the coseismic interferograms. The coordinates of four points: A (28.86°N, 87.56°E), B (28.74°N, 87.55°E), C (28.83°N, 87.6°E), and D (28.66°N, 87.59°E).

InSAR observations over the six months following the earthquake show that the deformation area of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake is not continuous. Deformation primarily occurs on both sides of the rupture trace and is clearly distributed along the rupture trace. As time progresses, the deformation magnitude continues to increase, and the affected area expands.

In the western area close to the rupture trace, both the ascending and descending LOS time-series deformation fields exhibit discontinuous subsidence signals. The overall subsidence area on the western side is smaller than that on the eastern side, with a maximum cumulative LOS subsidence of approximately −94 mm over the first half-year (Figure 7l). On the eastern side of the rupture trace, the ascending-orbit LOS deformation field shows small-magnitude subsidence or uplift, which can be attributed to complex topography and differences in observation geometry.

In contrast, the descending orbit LOS deformation field is characterized by widespread uplift on the eastern side, with a maximum cumulative LOS uplift of about 75 mm over the same period (Figure 7l). The vertically resolved time-series deformation field obtained through two-dimensional decomposition indicates that the western side of the rupture trace is dominated by relatively continuous subsidence, with a maximum vertical subsidence of approximately −68 mm, whereas the eastern side is characterized by uplift. Reaching a maximum of about 53 mm (Figure 7r). In the postseismic vertical deformation time series, the deformation patterns on both sides of the rupture trace are basically consistent with those observed during the coseismic stage. The opposite deformation directions across the fault trace suggest that the postseismic deformation may partially inherit the kinematic characteristics of coseismic normal-fault motion [41].

Generally, postseismic afterslip tends to occur within several months to one year after a mainshock and is typically distributed on both sides of the ruptured fault [42]. The postseismic deformation observed in this study suggests that afterslip may be a primary driving mechanism for the early postseismic deformation [41]. In addition, a small area to the southeast of the epicenter exhibits different degrees of subsidence in the descending orbit and vertical time-series results, with a cumulative deformation reaching a maximum of approximately 41.2 mm. Meanwhile, a previously mapped NE–SW striking regional fault on the west side of the rupture trace also shows some degree of surface subsidence.

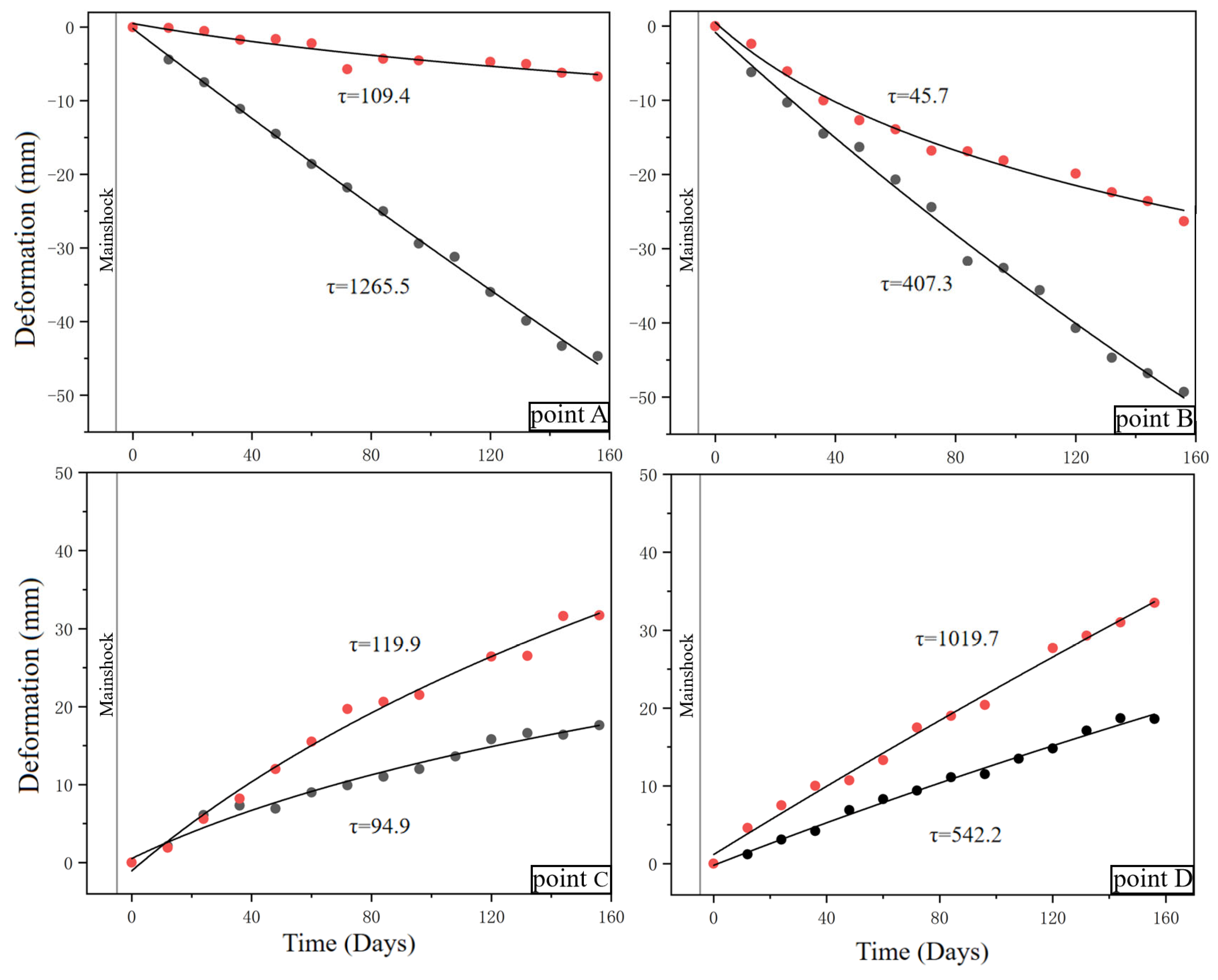

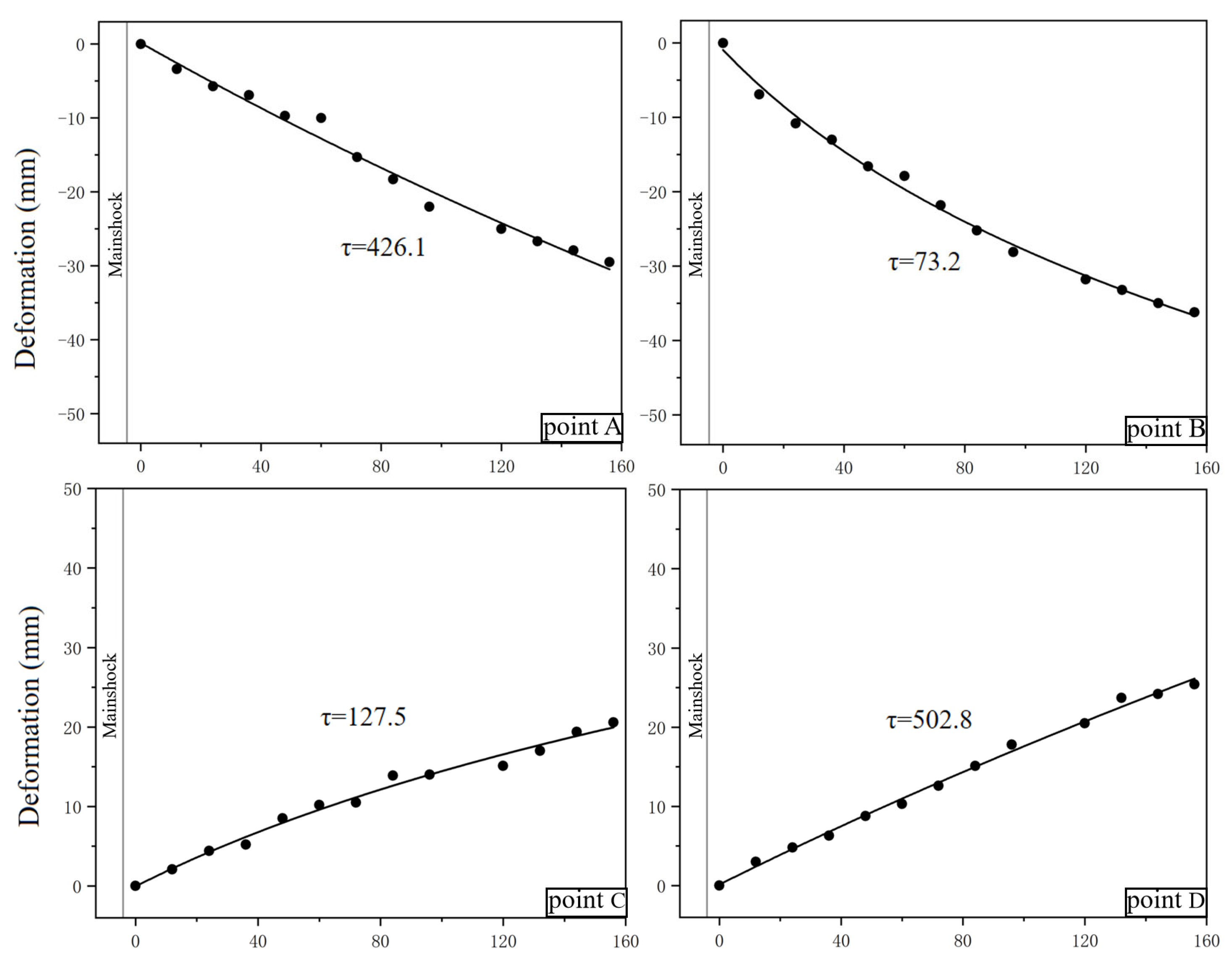

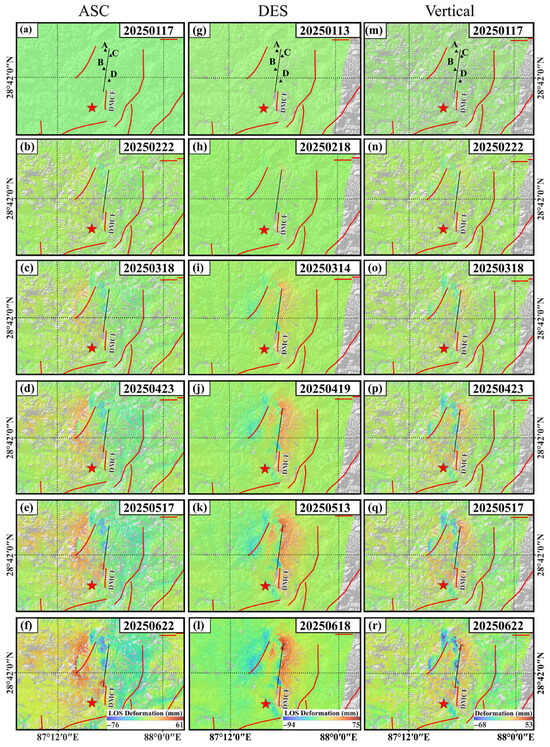

For the time-series deformation results of the four locations A–D with obvious deformation characteristics, the optimal fit is performed using Formula (5) [42] is as follows:

where indicates the fitting deformation time series, is the scaling factor, indicates the observation time (days), indicates the decay coefficient (unit in days), and indicates the offset of the curve. This formula is highly consistent with the logarithmic decay nature of postseismic deformation, with the decay coefficient τ being the key parameter. A smaller τ indicates faster decay, whereas a larger value indicates slower decay.

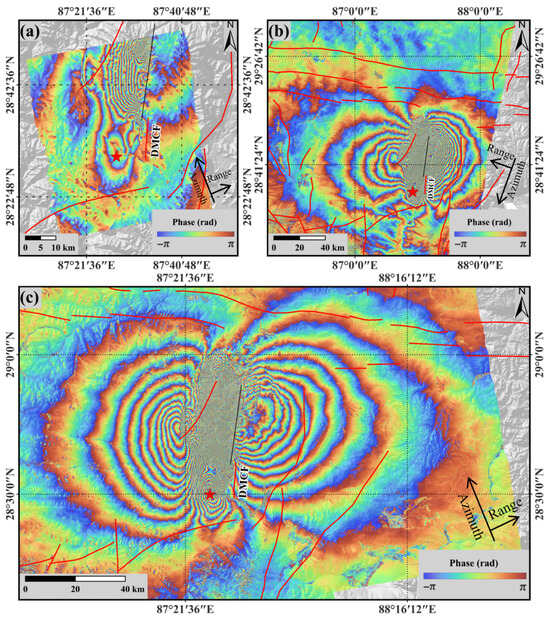

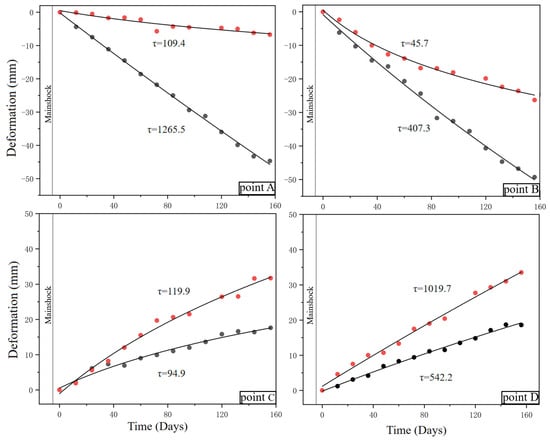

According to the above formula, the fitting results of the SBAS-InSAR ascending and descending orbits time series at the four feature points are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Postseismic time series and decay coefficient τ of typical deformation points. Red scatter points represent the descending orbit deformation time series, black scatter points represent the ascending orbit deformation time series, the black curve represents the optimal fitting curve, and the gray vertical lines represent the time when the mainshock occurred.

Figure 8 shows the fitted postseismic deformation time series at four feature points (A–D). Points A and B are located on the hanging wall of the rupture trace, while points C and D are situated on the footwall. Overall, the ascending (black scatter points) and descending (red scatter points) observations exhibit opposite deformation trends across the fault: the hanging wall (points A and B) generally shows LOS subsidence, whereas the footwall (points C and D) displays LOS uplift.

From the logarithmic fitting curves (black curves), it can be seen that the deformation time series of the points all show a gradual accumulation trend over time, with noticeable differences in the decay coefficient τ. Points B and C have relatively small τ values (45.7 days and 94.9 days, respectively), while the observation window spans approximately 160 days, covering their characteristic decay periods. This suggests that the deformation at these locations decayed relatively quickly, possibly related to rapid stress release in shallow fault segments. In contrast, points A and D have much larger τ values (1265.5 days and 1019.7 days, respectively), indicating that no obvious decay trend was observed during the observation period and that deformation is still ongoing.

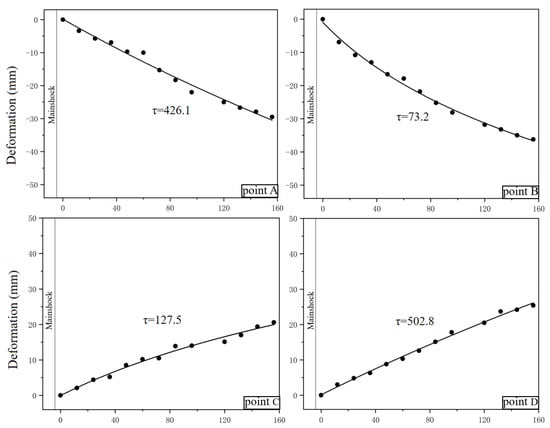

To further clarify the postseismic vertical deformation pattern, we extracted vertical deformation time series at four representative points (A–D, location in Figure 7m) located on opposite sides of the rupture trace (Figure 9). The vertical deformation at each point was fitted using a logarithmic decay function.

Figure 9.

Postseismic time series and decay coefficient τ of typical deformation points. Black scatter points represent the vertical deformation time series, the black curve represents the optimal fitting curve, and the gray vertical lines represent the time when the mainshock occurred.

As shown in Figure 9, points A and B, located on the hanging wall (western side of the rupture trace), exhibit continuous vertical subsidence after the mainshock, whereas points C and D, located on the footwall (eastern side of the rupture trace), show persistent uplift. This deformation pattern is basically consistent with the normal-faulting characteristics observed during the coseismic stage, suggesting that a certain degree of deformation continued to occur along both sides of the rupture trace after the coseismic stage.

Overall, the deformation characteristics on both sides of the fault after the earthquake are basically consistent with those observed during the coseismic stage, suggesting that the postseismic deformation process may be related to continued fault slip or stress readjustment. The differences in the decay coefficient τ among different locations may be closely associated with the segmental variations along the Xainza–Dinggye fault zone.

6. Conclusions

This study integrated D-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR methods with Lutan-1 and Sentinel-1 SAR data to obtain the coseismic surface deformation field of the Mw 7.0 Dingri earthquake on 7 January 2025, inverted the detailed geometric parameters and slip distribution of the seismogenic fault, and analyzed the postseismic time-series surface deformation field. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The multi-orbit coseismic deformation fields obtained using the D-InSAR technique show that the maximum LOS subsidence in the study area reached −2.03 m, located west of the rupture trace, while the maximum LOS uplift was 0.74 m, located east of the rupture trace. The deformation on the western side of the fault was significantly greater than on the eastern side.

- (2)

- The fault slip inversion results indicate that the seismogenic fault of this earthquake is the nearly north–south-trending fault. The initial identification is DMCF, with a strike of 183.89°, a dip of 68°, and a rake of −74.23°. The maximum slip is approximately 3.97 m. The released seismic moment is 5.01 × N·m, corresponding to a moment magnitude of Mw 7.1.

- (3)

- The postseismic results indicate that the main deformation was concentrated in the near-field areas on the hanging wall and footwall along the rupture trace. The surface deformation characteristics on both sides of the rupture trace were basically consistent with those observed during the coseismic stage. The differences in the decay coefficient τ suggest that deformation in the B and C areas decayed relatively quickly, while that in the A and D areas decayed more slowly and continued to accumulate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and C.S.; methodology, Y.X. and Q.D.; software, D.L.; validation, Q.D. and C.S.; formal analysis, D.L. and Q.D.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L. and Y.X.; writing—review and editing, D.L., Y.X., Q.D., C.S., X.Z., Y.Q., W.W. and Z.M.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, Q.D. and Z.M.; project administration, Y.X.; funding acquisition, Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Development Fund of Macau (FDCT) (grant Nos. 0021/2024/RIA1, 0158/2024/AFJ, and 002/2024/SKL) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No.42501577).

Data Availability Statement

Sentinel-1 SAR images were downloaded from the European Space Agency (ESA) (https://search.asf.alaska.edu/#/, accessed on 22 July 2025). Lutan-1 SAR images were downloaded from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (TPDC) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home, accessed on 25 July 2025). The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The European Space Agency provided the Sentinel-1data, and the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (TPDC) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home, accessed on 25 July 2025) provided data support. Some figures in this paper were created using GMT 5 software, and some scripts were provided by teachers from the College of Geoexploration Science and Technology, Jilin University, Changchun.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Luo, H.; Wang, T.; Wei, S.; Liao, M.; Gong, J. Deriving Centimeter-Level Coseismic Deformation and Fault Geometries of Small-to-Moderate Earthquakes from Time-Series Sentinel-1 SAR Images. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 636398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.Y.; Liu, J.; Shao, Y.X.; Wang, P.; Yuan, Z. Analysis about the Minimum Magnitude Earthquake Associated with Surface Ruptures. Seismol. Geol. 2015, 37, 1193–1214. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Q.; Xu, C. Advances in Earthquake and Cascading Disasters. Nat. Hazards Res. 2025, 5, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulger, G.R.; Dong, L. Induced Seismicity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Strak, V.; Schellart, W.P. Geodynamics of Long-Term Indian Continental Subduction and Indentation at the India-Eurasia Collision Zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2025, 130, e2025JB031427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, A.; Calò, F. A Review of Interferometric Synthetic Aperture RADAR (InSAR) Multi-Track Approaches for the Retrieval of Earth’s Surface Displacements. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gens, R.; Van Genderen, J.L. Review Article SAR Interferometry—Issues, Techniques, Applications. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1803–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ding, X.; Li, Z. Monitoring Earth Surface Deformations with InSAR Technology: Principles and Some Critical Issues. J. Geospat. Eng. 2000, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Parvin, N.S.; Abudu, D. Reviewing the Pertinence of Sentinel-1 SAR for Urban Land Use Land Cover Classification. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. 2020, 11, 529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiao, Q.; Jiang, W.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Y. Application of Lutan-1 SAR Satellite Constellation to Earthquake Industry and Its Prospect. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2024, 49, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, H.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z. Rapid Disaster Assessment of a 6.8-Magnitude Earthquake in Dingri, Tibet. Earthq. Res. Adv. 2025, 5, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Guo, H.; Dou, J.; Cao, L. Investigation on Seismic Source Activity and Active Geological Hazards of the Ms 6.8 Dingri Earthquake in Tibet. J. Earth Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Q.; Zhou, Z. Rapid Report of Seismic Damage and Consequence Analysis in the 2025 M 6.8 Dingri Earthquake. Earthq. Res. Adv. 2025, 5, 100394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, S.; Luo, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, J. The Tectonic Significance of the MW 7. 1 Earthquake Source Model in Tibet in 2025 Constrained by InSAR Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hua, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, W.; Zang, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, H. Geodetic Observations and Seismogenic Structures of the 2025 Mw 7.0 Dingri Earthquake: The Largest Normal Faulting Event in the Southern Tibet Rift. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Lu, Z.; Yan, S.; Shi, H.; Zhi, M.; Zhao, D. The 2025 MW7.0 Dingri Earthquake: Conjugate Normal Faulting of a Graben Structure in the Southern Xainza-Dinggye Rift. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2025GL116154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, Q.; Lu, H.; He, G.; Fan, L.; Qin, J. InSAR Coseismic Deformation Detection and Fault Slip Distribution Inversion of the Ms 6.8 Earthquake in Dingri, Tibet on January 7, 2025. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 52, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, X.; Song, C.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Han, B.; Liu, Z.; Liu, M.; et al. Source Characteristics and Induced Hazards of the 2025 M6.8 Dingri Earthquake, Xizang, China, Revealed by Imaging Geodesy. J. Earth Sci. 2025, 36, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusok, A.E.; Stegman, D.R. The Convergence History of India-Eurasia Records Multiple Subduction Dynamics Processes. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hong, S.; Dong, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, J.; He, J. Coseismic Deformation and Fault Slip Distribution of the January 7, 2025, Dingri Mw 7.1 Earthquake. Earth Sci. 2025, 50, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Tian, L.; Jiang, X.; Xue, Y.; Yao, Q.; Xie, M.; Zang, Y.; Song, J.; Lu, X.; et al. Summary of the 20 March 2020 Ms 5.9 Dingri Earthquake in Tibet. Seismol. Geomagn. Obs. Res. 2020, 41, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Ding, L. Structural characteristics of the southern segment of the Xainza-Dinggye normal fault system and its relationship with the South Tibet Detachment System. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2002, 47, 738–743. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Tan, K.; Du, R. Crustal Deformation on the Chinese Mainland during 1998–2014 Based on GPS Data. Geod. Geodyn. 2015, 6, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, X.; Yu, G.; Ren, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, G.; Xu, C.; Du, K.; Huang, X.; Yang, H. The China Active Faults Database (CAFD) and Its Web System. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 3391–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.; Snoeij, P.; Geudtner, D.; Bibby, D.; Davidson, M.; Attema, E.; Potin, P.; Rommen, B.; Floury, N.; Brown, M. GMES Sentinel-1 Mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, T.; Fan, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Tian, Z. Mining Deformation Monitoring Based on Lutan-1 Monostatic and Bistatic Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, D.; Liang, D.; Fang, T.; Wang, R. On the Processing of Dual-Channel Receiving Signals of the LuTan-1 SAR System. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, H.; Amelung, F. InSAR Uncertainty Due to Orbital Errors. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 199, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, S.; Rengarajan, R. Evaluation of Copernicus DEM and Comparison to the DEM Used for Landsat Collection-2 Processing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Meng, Z.; Wu, Q.; Xiong, W.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, D. Coseismic and Early Postseismic Deformation Mechanism Following the 2021 Mw 7.4 Maduo Earthquake: Insights from Satellite Radar Interferometry and GPS. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, A.P.; Zebker, H. Edgelist Phase Unwrapping Algorithm for Time Series InSAR Analysis. J. Opt. Soc. Amer. A 2010, 27, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Li, Z.; Penna, N.T. Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Atmospheric Correction Using a GPS-Based Iterative Tropospheric Decomposition Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 204, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, Z.; Penna, N.T.; Crippa, P. Generic Atmospheric Correction Model for Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Observations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2018, 123, 9202–9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y. Surface Deformation Due to Shear and Tensile Faults in a Half-Space. Bull. Seism. Soc. Am. 1985, 75, 1135–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Lan, H.; Yin, H.; Li, L.; Strom, A.; Sun, W.; Tian, C. Deformation, Structure and Potential Hazard of a Landslide Based on InSAR in Banbar County, Xizang (Tibet). China Geol. 2024, 7, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, W.; Li, Z. Review of the SBAS InSAR Time-Series Algorithms, Applications, and Challenges. Geod. Geodyn. 2022, 13, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y. Error Compensation and High-Precision Baseline Estimation in InSAR Geolocation Using GCPs. In Proceedings of the Geoinformatics 2006: GNSS and Integrated Geospatial Applications; SPIE: Cergy, France, 2006; 6418, pp. 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Fu, H.; Liu, L.; Feng, G.; Peng, X.; Wen, D. Orbit Error Removal in InSAR/MTInSAR with a Patch-Based Polynomial Model. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smittarello, D.; d’Oreye, N.; Jaspard, M.; Derauw, D.; Samsonov, S. Pair Selection Optimization for InSAR Time Series Processing. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2021JB022825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, C.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Z.; Duan, P. Landslide Displacement Prediction Using Time Series InSAR with Combined LSTM and TCN: Application to the Xiao Andong Landslide, Yunnan Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 3857–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wen, Y.; Xu, C.; Hu, Q. Complex Multifault Rupture During the 2016–2025 Dingri Earthquakes, Southern Tibetan Plateau, Unraveled by Multisource InSAR Observations. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2025, 97, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Chen, W.; Wang, D.; Wen, Y.; Nie, Z.; Liu, G.; Dijin, W.; Yu, P.; Qiao, X.; Zhao, B. Coseismic Slip and Early Afterslip of the 2021 Mw 7.4 Maduo, China Earthquake Constrained by GPS and InSAR Data. Tectonophysics 2022, 840, 229558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.