Highlights

A comprehensive review of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) in Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI), covering architectures, applications, challenges, and future directions.

What are the main findings?

- GANs enhance HSI analysis: Integrating GANs into HSI improves data interpretation, which increases the practicality and usefulness of HSI across various industries.

- Identification of research gaps: The survey highlights critical gaps in hyperparameter tuning, architectural efficiency, and domain-specific applications of GANs in HSI. This provides researchers with clear directions for improvement.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Broader industry adoption: With improved analysis powered by GANs, HSI can be applied more effectively in real-world domains such as agriculture, healthcare, and environmental monitoring.

- Future research roadmap: By exposing gaps in GAN-HSI integration, the study acts as a foundation for future innovation, guiding researchers toward developing more efficient, robust, and domain-adapted models.

Abstract

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) captures rich spectral information across a wide range of wavelengths, enabling advanced applications in remote sensing, environmental monitoring, medical diagnosis, and related domains. However, the high dimensionality, spectral variability, and inherent noise of HSI data present significant challenges for efficient processing and reliable analysis. In recent years, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have emerged as transformative deep learning paradigms, demonstrating strong capabilities in data generation, augmentation, feature learning, and representation modeling. Consequently, the integration of GANs into HSI analysis has gained substantial research attention, resulting in a diverse range of architectures tailored to HSI-specific tasks. Despite these advances, existing survey studies often focus on isolated problems or individual application domains, limiting a comprehensive understanding of the broader GAN–HSI landscape. To address this gap, this paper presents a comprehensive review of GAN-based hyperspectral imaging research. The review systematically examines the evolution of GAN–HSI integration, categorizes representative GAN architectures, analyzes domain-specific applications, and discusses commonly adopted hyperparameter tuning strategies. Furthermore, key research challenges and open issues are identified, and promising future research directions are outlined. This synergy addresses critical hyperspectral data analysis challenges while unlocking transformative innovations across multiple sectors.

1. Principles of Hyperspectral Imaging

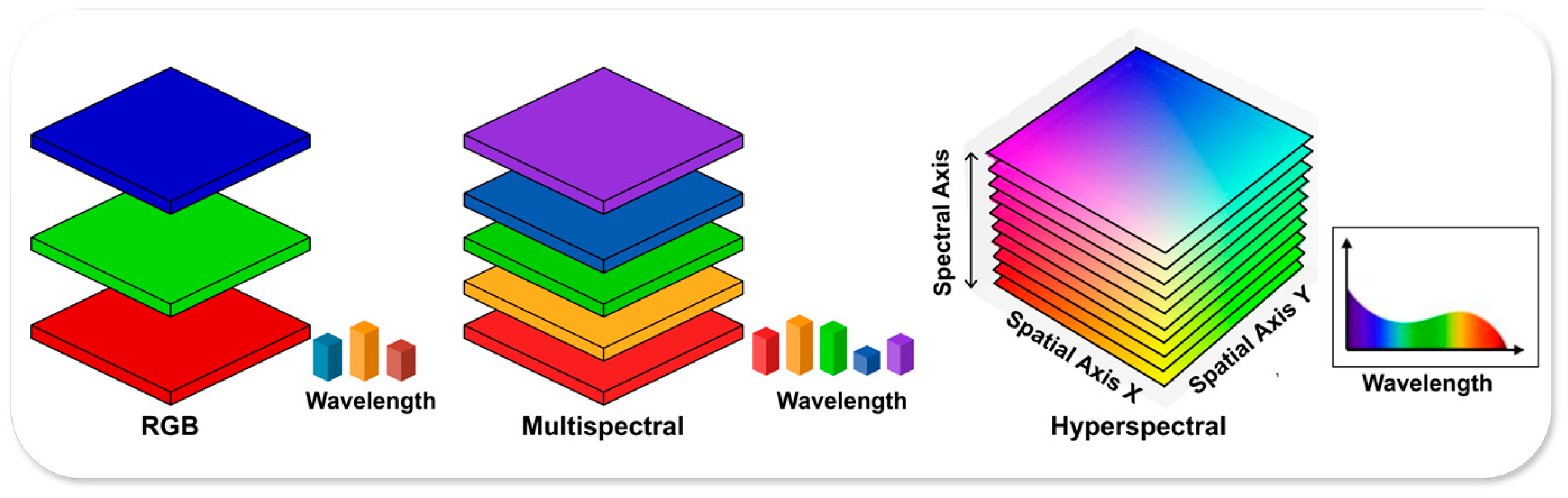

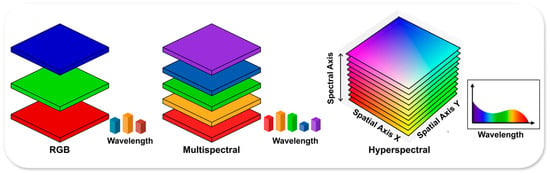

The field of imaging has witnessed transformative advancements with the emergence of HSI, a technique that transcends the limitations of traditional RGB imaging [1,2]. Unlike conventional methods that usually capture only three primary colors, HSI provides a comprehensive spectral analysis by acquiring data across hundreds of closely spaced spectral bands spanning the visible to infrared electromagnetic spectrum [3,4,5]. Figure 1 represents a sample RGB with three bands, a multispectral sample with n separated bands, and an HSI cube where each pixel within this cube represents a continuous spectrum of reflectance.

Figure 1.

RGB vs. Multispectral vs. Hyperspectral Image Representation.

The 3D HSI data cubes can be depicted as D ∈ ℝ(X × Y × Z), where X and Y are spatial dimensions and Z represents spectral bands [6,7,8]. Unlike RGB images limited to three bands, HSI captures detailed spectral signatures p(x, y) ∈ ℝZ for each pixel [8,9]. HSI integrates spatial (X, Y) and spectral (Z) data. Spatial dimensions provide geometric details for tasks like land cover classification [8,9,10,11], while spectral dimensions capture reflectance or radiance values λz, enabling material identification [11,12,13]. This integration enables the detection of subtle variations that go beyond the capabilities of traditional imaging techniques. However, as discussed in Section 1.1, there are several challenges associated with HSI processing that need to be addressed.

1.1. Challenges with HSI Processing

- Sensitivity to Environmental Variables: HSI systems are highly sensitive to environmental variables, which can lead to signal degradation and compromise data reliability.

- High-Dimensional Datasets and Computational Overload: HSI inherently generates massive high-dimensional datasets [10,14], which often over- whelm existing computational infrastructures [15,16].

- Scarcity of Labeled Training Data: HSI processing heavily relies on deep learning models due to its high-dimensional nature, but the acute shortage of labeled data limits the performance of the models [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The costly and time-consuming annotation process [9,11,22] further exacerbates this challenge across various domains.

- Spectral Complexity: The intricate spectral characteristics of HSI data make it challenging to distinguish between materials with similar spectral signatures, especially in scenarios with mixed pixels or subtle differences [23,24].

1.2. Evolution of Deep Learning Solutions, Especially GANs, for HSI Processing

Initially, researchers explored various machine learning approaches, such as sup- port vector machines, random forests, principal component analysis (PCA), transfer learning [18], traditional data augmentation techniques [19], and t-SNE [20], to address the aforementioned challenges in HSI processing. However, the conventional approaches demonstrated limited success in handling the intricate spectral complexities inherent to HSI data [21]. These methods consistently struggle with three fundamental challenges: limited sample sizes, the high dimensionality of the data, and the complex spectral variations that defy conventional computational frameworks [18,19,20,21].

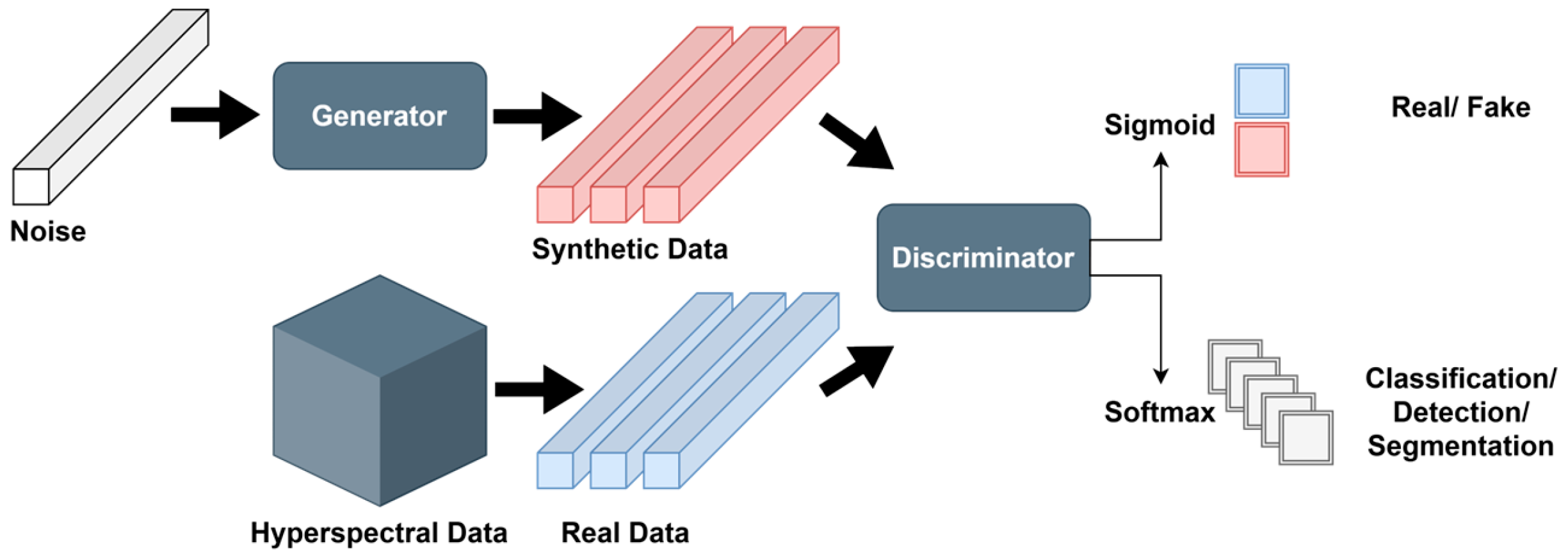

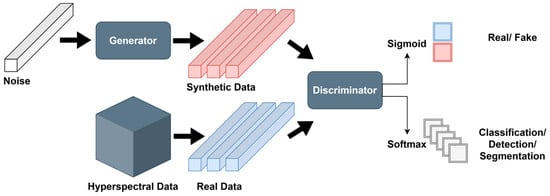

To address these challenges faced by machine learning models, deep learning models such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have emerged as a ground-breaking solution [25,26,27,28]. By leveraging an adversarial framework consisting of a generator and a discriminator as illustrated in Figure 2, GANs excel in capturing complex data distributions and synthesizing realistic hyperspectral data. This capability directly addresses the scarcity of labeled training data by augmenting datasets with high-quality synthetic samples, reducing the reliance on costly and time-intensive manual labeling [23].

Figure 2.

Architecture of Generative Adversarial Networks.

GANs also tackle the challenges of spectral complexity by effectively modeling intricate spectral characteristics and distinguishing materials with similar spectral signatures, even in mixed-pixel scenarios. Furthermore, GANs mitigate computational overload associated with the high dimensionality of HSI data by extracting and preserving essential spectral and spatial features, enabling efficient processing without compromising data integrity. They also enhance robustness against environmental variability by generating synthetic data under diverse conditions, improving the reliability and consistency of HSI applications. These advancements position GANs as a pivotal deep learning framework for overcoming traditional limitations in HSI processing, unlocking new potential across domains such as agriculture, environ- mental monitoring, and defense. To showcase their growing popularity, next section showcases the growing number of publications on amalgamation of HSI and GANs.

1.3. The Growing Intersection of GANs and HSI

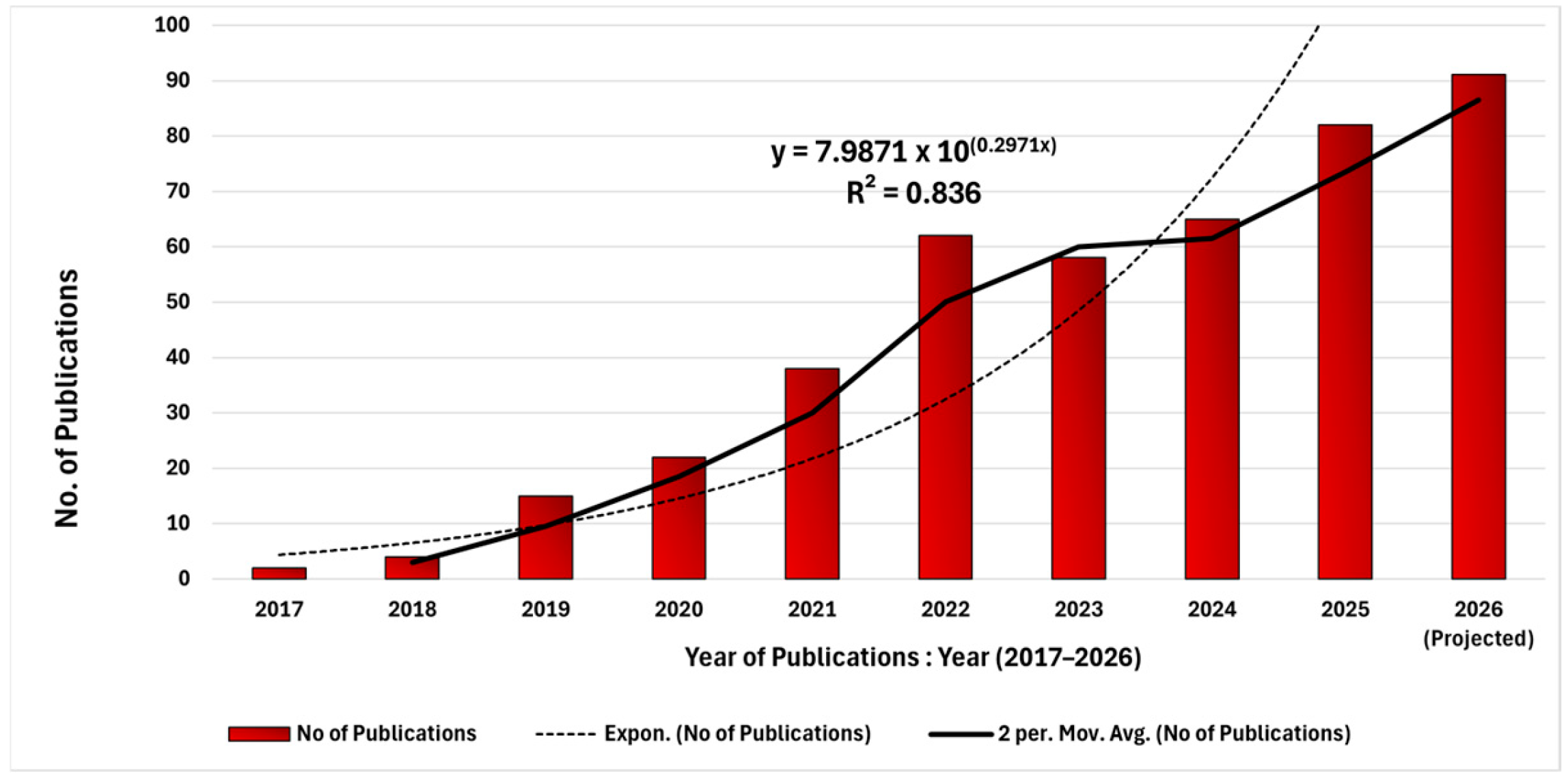

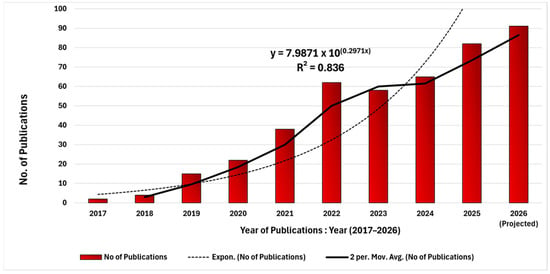

Figure 3 represents the increase in the number of publications on GAN research in HSI processing since their introduction in 2017. The growth in numbers has an exponential fit: y = 7.9871 × 100.2977x, where x is the year and y is the number of publications. The R2 value is 0.8362 indicating a good fit, explaining significant variation. The growth rate is 0.298, implying a 29.8% annual increase in publications.

Figure 3.

The Growth in Publications.

1.4. Key Contributions of Our Survey

Below are the key contributions of our study to summarizing the state of the art:

- A comprehensive and structured taxonomy of GAN architectures for HSI is presented, covering classical, conditional, attention-based, transformer-integrated, and hybrid GAN models. This taxonomy, detailed in Section 2 and Section 3, clarifies architectural evolution and highlights design choices specific to spectral–spatial data.

- An extensive survey of GAN-based HSI applications across diverse domains is conducted, including remote sensing, agriculture, environmental monitoring, medical imaging, food safety, and industrial inspection. Section 3 systematically analyzes how GANs address task-specific challenges such as limited labeled data, noise, spectral distortion, and resolution enhancement.

- A critical assessment of current limitations, open research gaps, and practical considerations is provided, including computational inefficiency, spectral–spatial trade-offs, data scarcity, domain generalization, real-time deployment constraints, evaluation metrics, benchmark datasets, ethical considerations, and model interpretability. These issues are synthesized through comparative analysis and summarized in Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6.

- Future research directions for GAN-enabled HSI are outlined in Section 4, with particular emphasis on transformer-based GANs, foundation models, multimodal learning, and scalable deployment, providing a forward-looking roadmap for the field.

1.5. Structure of Our Survey

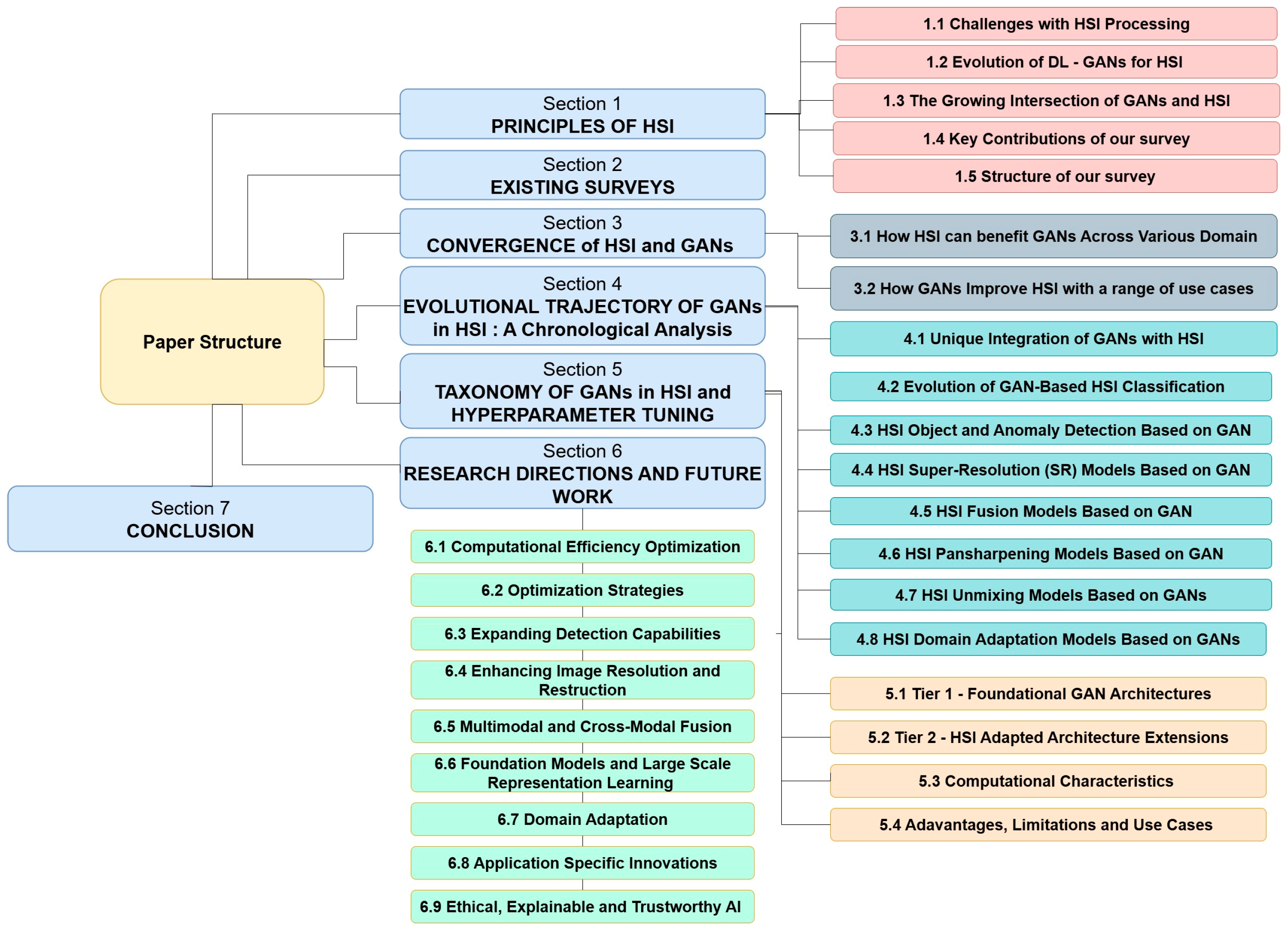

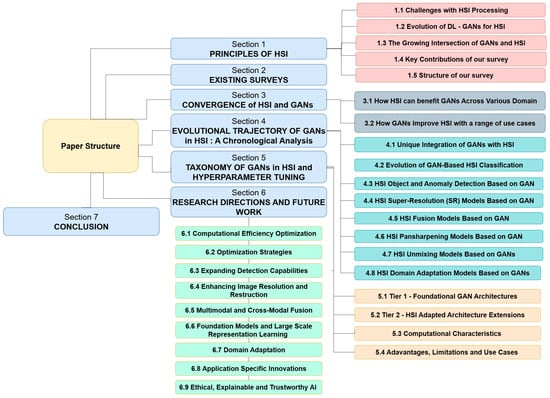

Figure 4 illustrates the six main sections of this survey on integrating GANs with HSI. Section 1 introduces HSI principles, highlights key challenges (Section 1.1), discusses the evolution of deep learning solutions (Section 1.2), talks about the growing intersection of GANs and HIS (Section 1.3) and presents our key contributions (Section 1.4). Section 2 delves into the progression of GAN-based models in HSI. Section 3 examines the synergy between GANs and HSI across different domains. Section 4 further explores the evolutionary trajectory of GANs in HSI. In Section 5, we provide a taxonomy of GAN variants and discuss hyperparameter tuning. Finally, Section 6 offers future research directions, with concluding remarks in Section 7.

Figure 4.

Flow of our study.

2. Existing Surveys

This section reviews state-of-the-art (S-O-T-A) surveys and compares them with our study, as summarized in Table 1. Since 2017, the integration of HSI and generative adversarial networks (GANs) has gained significant attention in fields such as remote sensing, agriculture, and medical diagnostics. However, most studies focus on GANs or HSI independently with limited coverage, leaving a critical gap in exploring their synergy. Despite the growing use of GANs in key applications like classification, anomaly detection, data augmentation, and super-resolution, no survey thoroughly examines their role in advancing HSI. Moreover, while deep learning-based surveys exist, they often provide limited coverage of crucial models like GANs. Appendix A shows the hyperspectral datasets used in the literature.

Table 1.

Survey of S-O-T-A Surveys in HSI and GAN.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Survey Coverage and Novel Contributions

To objectively validate the novelty and comprehensive scope of this survey, we performed a quantitative benchmarking analysis comparing our coverage against existing HSI- and GAN-related surveys published between 2017 and 2025. Three metrics were evaluated: (1) GAN Variant Coverage, (2) HSI Task Coverage, and (3) Temporal Coverage of Recent Advancements (2023–2025). Across a corpus of 42 prior surveys, the average number of GAN variants discussed per survey was 5.1, whereas the present work synthesizes 38 distinct GAN variants, representing a 6.9× increase in architectural breadth. Similarly, previous surveys addressed an average of 3.4 hyperspectral tasks, typically limited to classification, anomaly detection, or super-resolution. Our review systematically covers 10 task categories, including emerging areas such as unmixing, pan-sharpening, synthetic dataset generation, multimodal fusion, and domain adaptation—an expansion of 194% relative to the existing literature.

Temporal benchmarking reveals an even more significant gap. Among prior surveys, only 12% incorporated works beyond 2022, and none provided coverage of developments from 2024–2025, despite rapid growth in publications on HSI–GAN integration. In contrast, our survey includes 72 papers published between 2023 and 2025, including the newest transformer-based GANs, physics-informed GANs, abundance-guided generative models, and federated GAN frameworks—making this the first review to capture the most recent methodological advances. Collectively, these quantitative benchmarks clearly demonstrate that this survey fills a substantial gap in the existing literature by offering the most comprehensive, up-to-date, and task-integrated synthesis of GAN applications in HSI imaging to date.

Therefore, the focus of this survey is to have comprehensive coverage on HSI and GANs focusing on emerging GAN models with an in-depth coverage of these models. Significant advancements in GAN architecture and loss functions tailored for HSI have been made, but challenges like limited labeled data, spectral redundancy, high-dimensional complexity, and model interpretability persist. Additionally, the absence of robust hyperparameter tuning and multi-modal fusion techniques limit practical applications. This survey addresses these gaps, systematically analyzing the integration of GANs and HSI to uncover their full potential and provide a foundation for future research.

3. The Convergence of Hyperspectral Imaging and GANs: Domain-Specific Applications

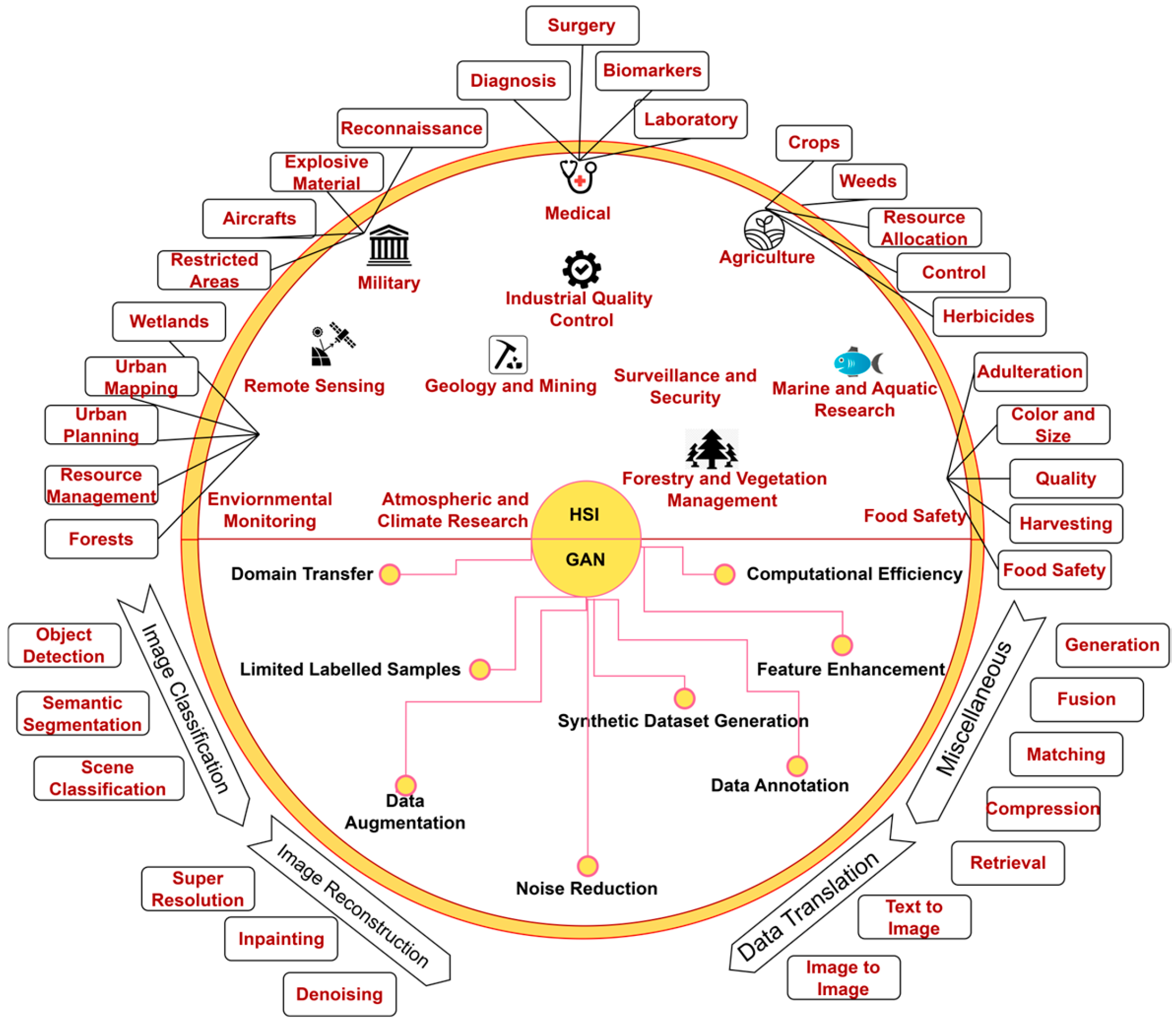

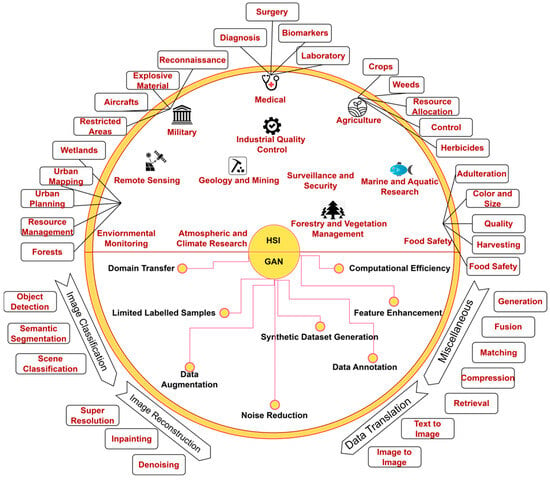

Figure 5 illustrates the synergy of HSI and GAN, depicting the wide-ranging applications of integrating GANs with HSI across various domains, showcasing their potential to address complex challenges effectively. This figure illustrates the synergistic integration of GANs with HSI, highlighting (i) domain-specific application areas (outer ring), (ii) core challenges in hyperspectral analysis (inner ring), and (iii) GAN-enabled solution mechanisms (central pathways).

Figure 5.

Integration of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI).

The outer circular layer represents major application domains—including medicine, agriculture, food safety, forestry, marine research, surveillance and security, geology and mining, industrial quality control, environmental monitoring, and cultural heritage—where HSI–GAN frameworks have demonstrated substantial impact.

The inner layer captures key challenges inherent to hyperspectral data, such as limited labelled samples, high spectral dimensionality, noise, domain shift, and computational constraints. GANs address these challenges through multiple functional roles illustrated by the connecting pathways from the central HSI–GAN core.

Limited Labelled Samples refers to the scarcity and high cost of ground-truth annotations in hyperspectral datasets. GANs mitigate this issue through synthetic dataset generation, data augmentation, and semi-supervised learning, enabling effective model training under label-constrained conditions.

Feature Enhancement denotes the ability of GANs to amplify discriminative spectral–spatial patterns that are often subtle or degraded in raw hyperspectral data, improving class separability and supporting tasks such as classification, segmentation, and anomaly detection.

In addition, GANs contribute to noise reduction by learning clean spectral manifolds and suppressing sensors and environmental noise through adversarial reconstruction. Image reconstruction and super-resolution mechanisms enable the recovery of high-quality HSI from degraded or low-resolution inputs while preserving spectral fidelity. Data translation and fusion facilitate cross-modal and cross-resolution learning—such as RGB-to-HSI generation or panchromatic–hyperspectral fusion—enhancing both spatial and spectral representation. Finally, domain adaptation allows GANs to align feature distributions across sensors, acquisition conditions, or environments, improving generalization and robustness in real-world deployments. Together, these functionalities demonstrate how GANs serve as a unifying framework for overcoming intrinsic HSI limitations while extending HSI capabilities across diverse domains and applications.

3.1. How HSI Can Benefit Across Various Domains

The wide applicability of HSI across multiple domains is significantly enhanced through the integration of GANs explained below:

- Medicine: In tissue oxygen saturation mapping, GAN-based frameworks effectively manage the inherent spectral–spatial trade-off in hyperspectral medical data. Chang et al. [37] demonstrated that adversarial learning enables the preservation of fine spectral absorption characteristics critical for oxygenation estimation, while simultaneously enhancing spatial continuity through generator–discriminator interaction. This joint optimization mitigates spectral distortion commonly introduced by purely spatial enhancement techniques. Similarly, in microscopy super-resolution, Zhang et al. [38] employed a dual-discriminator GAN architecture to decouple spatial resolution enhancement from spectral fidelity preservation. One discriminator enforces high-frequency spatial realism, while the second constrains spectral consistency, ensuring that super-resolved outputs maintain biologically meaningful spectral signatures. This design addresses the common challenge of spectral degradation during aggressive spatial up sampling in medical HSI.

- Agriculture: In agricultural applications, HSI combined with GANs supports crop and weed discrimination, resource optimization, and chemical residue analysis. Tan et al. [39] leveraged HSI for predicting pesticide residues, while Zhang et al. [40] employed attention-guided GANs to augment corn hyperspectral datasets, improving model robustness under limited labeled samples and varying growth conditions.

- Marine and Aquatic Research: In marine and aquatic environments, GAN-assisted HSI facilitates the synthesis and enhancement of vegetation and water-quality data. Hennessy et al. [41] demonstrated the use of GAN-generated hyperspectral vegetation data to support aquatic ecosystem analysis and resource management, highlighting the potential of HSI–GAN integration for studying underwater and coastal environments.

- Food Safety: HSI plays a vital role in food safety by enabling non-destructive assessment of product quality, composition, and freshness. Qi et al. [42] utilized HSI to analyze rice seed viability, while Cui et al. [43] applied GAN-based regression models to predict soluble sugar content in cherry tomatoes, illustrating how GANs enhance spectral sensitivity and prediction accuracy in food quality evaluation.

- Forestry and Vegetation Management: In forestry and vegetation monitoring, GAN-based HSI methods improve detection of defects, stress, and structural anomalies. Li et al. [44] employed GANs for identifying unsound kernels, while HSI more broadly supports large-scale vegetation assessment, forest health monitoring, and sustainable resource management.

- Surveillance and Security: In surveillance and security-related remote sensing, GANs enhance hyperspectral change detection, scene classification, and anomaly identification. Xie et al. [45] introduced federated GANs for hyperspectral change detection, enabling decentralized analysis, while Mahmoudi and Ahmadyfard [46] applied GANs for scene classification, supporting reconnaissance and monitoring of sensitive or restricted areas.

- Geological and Industrial Applications: In geological exploration, HSI–GAN methods improve material discrimination and subsurface mapping. Liu et al. [47] employed physics-informed GAN-based synthesis for geological mapping, while industrial inspection has benefited from precise spectral analysis, as demonstrated by Wang et al. [48] using single-pixel infrared HSI for quality control and defect detection.

- Environmental Monitoring and Climate Research: GAN-enhanced HSI contributes to environmental monitoring by improving biomass estimation, wetland mapping, and ecosystem analysis. Chen et al. [49] expanded wetland vegetation biomass datasets using HSI, supporting climate research and long-term environmental assessment under diverse atmospheric conditions.

- Cultural Heritage and Historical Research: In cultural heritage preservation, HSI–GAN frameworks enable non-invasive analysis and reconstruction of artifacts. Hauser et al. [50] demonstrated the use of synthetic hyperspectral data for artifact analysis, highlighting the role of GANs in enhancing spectral detail while preserving historical integrity.

3.2. How GANs Improve HSI with a Range of Use Cases

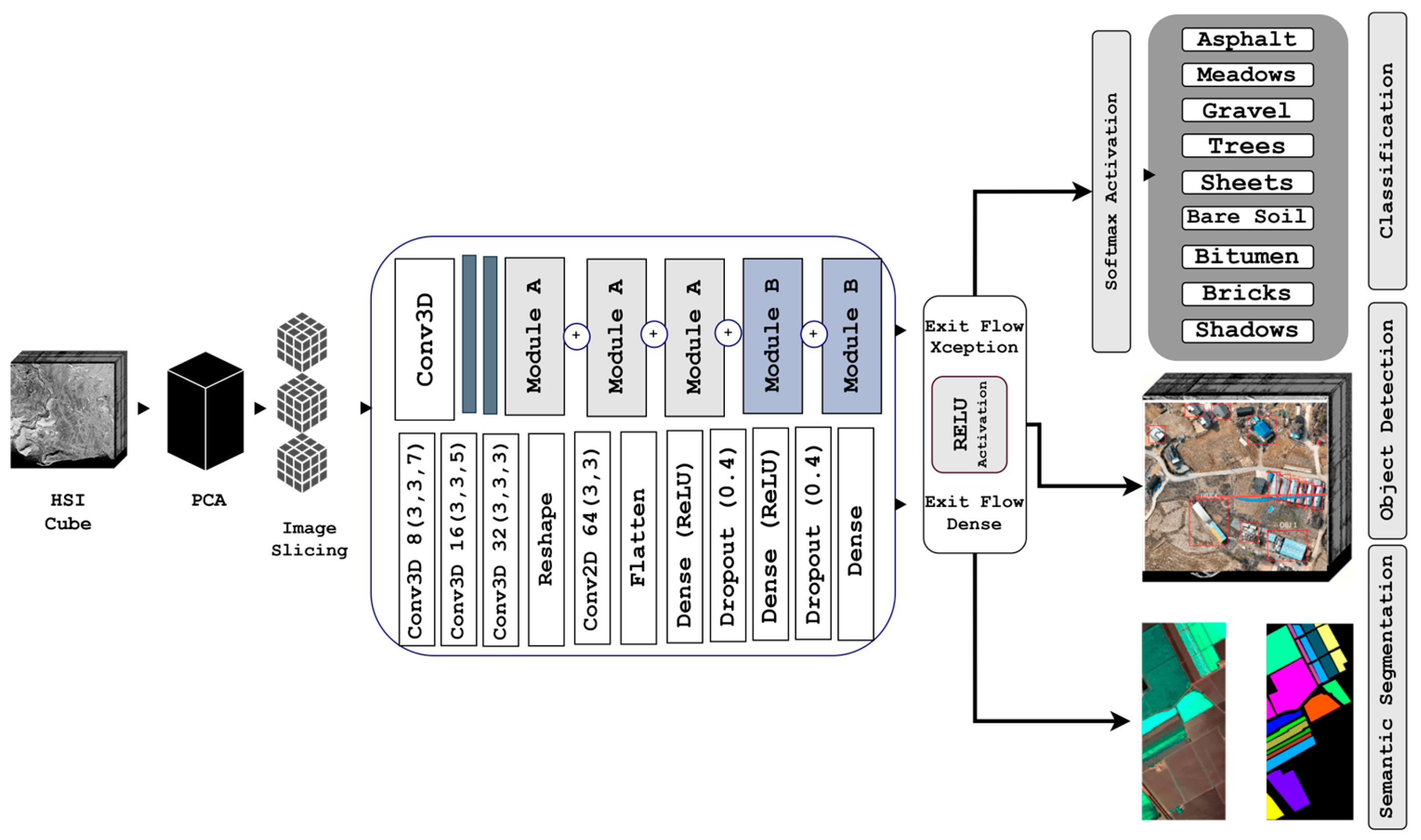

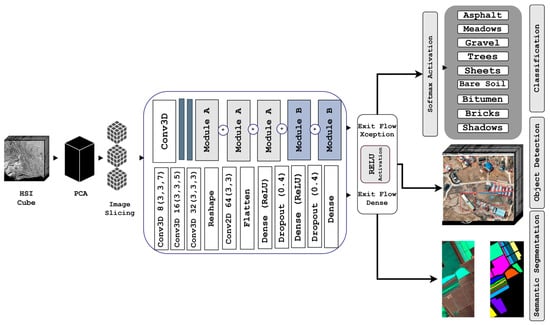

This section highlights the prominent applications of GANs in HSI. Figure 6 depicts a deep learning model with customized modules depending on prominent applications such as classification, object detection and segmentation.

Figure 6.

A customizable Deep Learning CNN based model for Classification, Object Detection and Segmentation Applications.

Classification: GANs have revolutionized HSI classification by enabling robust spatial-spectral feature extraction. Zhu et al. (2018) [2] proposed a GAN framework that significantly improved classification accuracy. Yu and Cui (2024) [3] introduced a state-of-the-art model tailored for challenging datasets, while Ranjan et al. (2024) [16] designed a spectral-spatial auxiliary GAN integrated with convolutional LSTM to enhance feature learning. In scenarios with limited labeled data, semi-supervised GANs like those developed by Zhan et al. (2023) [23] used spectral angle distance to achieve accurate classification.

Segmentation: In HSI segmentation, GANs have made significant strides. Zhu et al. (2023) [15] proposed QIS-GAN, which employs quadtree implicit sampling for efficient and accurate segmentation. Transformer-based GANs introduced by Li et al. (2024) [51] further refined pixel-level segmentation, leveraging attention mechanisms to preserve spatial-spectral coherence.

- Anomaly Detection: GANs are highly effective in detecting anomalies in HSI. Shanmugam and Amali (2024) [52] developed a dual-discriminator conditional GAN optimized with hybrid algorithms for anomaly detection. Xie et al. (2024) [45] introduced decentralized federated GANs, which facilitated anomaly detection in distributed edge computing environments.

- Spectral Unmixing: GANs have advanced spectral unmixing by enabling accurate pixel-to-abundance translations. Wang et al. (2024) [46] proposed a conditional GAN integrated with patch transformers [53,54,55] to enhance unmixing accuracy. Sun et al. (2024) [56] tackled shadowing challenges in unmixing by developing a generative autoencoder.

- Super pixel and Super-Resolution Applications: In super pixel-based HSI processing, GANs ensure spatial consistency and improve fusion of spectral-spatial data. Zhu et al. (2023) [15] demonstrated their effectiveness in enhancing classification and segmentation through super pixel representation. Additionally, GANs play a critical role in noise reduction and super-resolution tasks. Zhang et al. (2021) [57] showcased a degradation learning approach for unsupervised hyperspectral im- age super-resolution, reconstructing high-quality imagery while preserving spectral details.

- Data Augmentation and Unmixing: GANs excel in expanding limited hyper spectral datasets, addressing scarcity challenges. Zhang et al. (2023) [58] proposed a features-kept GAN strategy to enhance HSI classification, while Tan et al. (2024) [24] utilized an improved DCGAN for pesticide residue identification. Dong et al. (2021) [11] leveraged GANs for both spectral fidelity and spatial enhancement. Furthermore, Sun et al. (2024) [56] applied generative autoencoders for shadow removal and abundance estimation.

- Domain Adaptation: GANs facilitate seamless translation between different HSI platforms, standardizing spectral representations across diverse sensor technologies. Zhao et al. (2024) [59] developed HSGANs to reconstruct hyperspectral data from RGB images, enabling cross-platform spectral compatibility.

Feature Enhancement: GANs amplify subtle spectral patterns often over- looked by traditional methods. Liang et al. (2021) [13] proposed a spectral-spatial attention-based feature extraction method to improve classification, while Chen et al. (2021) [60] introduced a self-attention conditional variational autoencoder GAN to enhance classification performance.

Synthetic Dataset Generation: GANs enable the creation of diverse and realistic synthetic hyperspectral datasets. Hauser et al. (2021) [50] developed SHS- GAN, which enhanced natural hyperspectral databases, while Dam et al. (2020) [61] addressed class imbalance in HSI classification using a mixture of spectral GANs.

4. Evolutionary Trajectory of Generative Adversarial Networks in Hyperspectral Imaging: A Chronological Analysis

4.1. Unique Integration Mechanisms of GANs with Hyperspectral Data

Hyperspectral data possess inherent characteristics—high spectral dimensionality, strong band-to-band correlation, significant spectral variability, and nonlinear spectral mixing—that fundamentally differentiate them from conventional RGB or multispectral imagery. Consequently, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) require specialized architectural and methodological adaptations when applied to HSI. Existing studies reveal several unique integration mechanisms through which GANs effectively model hyperspectral distributions.

4.1.1. Joint Spectral–Spatial Representation Learning

Unlike natural images, hyperspectral cubes exhibit strong coherence along both spectral and spatial dimensions. To exploit this structure, HSI-specific GANs frequently adopt 3D convolutions, hybrid 3D–2D networks, or spectral attention modules. These components enable the generator and discriminator to learn spectral–spatial relationships simultaneously, improving fidelity in both domains. Transformer-based GANs further enhance long-range dependencies across spectral bands, addressing redundancy and reducing spectral distortion—an issue prevalent when applying conventional 2D GAN architectures to HSI.

4.1.2. Spectral Variation Compensation

HSI spectra are highly sensitive to illumination changes, atmospheric conditions, sensor characteristics, and scene geometry. GAN models address these challenges using Spectral Angle Distance (SAD) loss, physics-informed constraints, and domain-adversarial objectives. These mechanisms stabilize the spectral manifold learned by the generator, ensuring that variations due to acquisition conditions do not alter intrinsic material signatures. Such adaptation is particularly important for cross-sensor and cross-environment applications where spectral mismatch is prominent.

4.1.3. Modelling and Mitigating Spectral Mixing

Nonlinear spectral mixing—where a pixel contains contributions from multiple endmembers—is a core challenge in hyperspectral analysis. Modern GAN-based unmixing frameworks incorporate abundance-supervised generators, autoencoder–GAN hybrids, and pixel-to-abundance translation networks. These approaches recover pure endmember spectra while predicting abundance distributions, effectively performing nonlinear unmixing within an adversarial framework. By modelling mixture distributions directly, GANs overcome the limitations of traditional linear mixing models.

4.1.4. Stable Training for High-Dimensional Spectral Data

The extremely high dimensionality of HSI (often hundreds of channels) intensifies training instability, increasing susceptibility to mode collapse. HSI-oriented GANs employ techniques such as Wasserstein loss with gradient penalty, latent-space regularization, hybrid reconstruction–adversarial loss functions, and multiscale discriminators. These techniques ensure smoother optimization dynamics and improve convergence, enabling generators to synthesize high-resolution spectra with minimal noise amplification.

4.1.5. Mechanism–Gap Alignment

The integration mechanisms described above provide direct responses to known gaps in hyperspectral analysis. Joint spectral–spatial modelling mitigates spectral distortion; physics-constrained losses address environmental variability; abundance-aware generators solve nonlinear spectral mixing; and WGAN-GP–based training stabilizes high-dimensional optimization. This demonstrates that GAN–HSI integration extends beyond simple data synthesis and requires specialized mechanisms tailored to the physical and statistical properties of hyperspectral data.

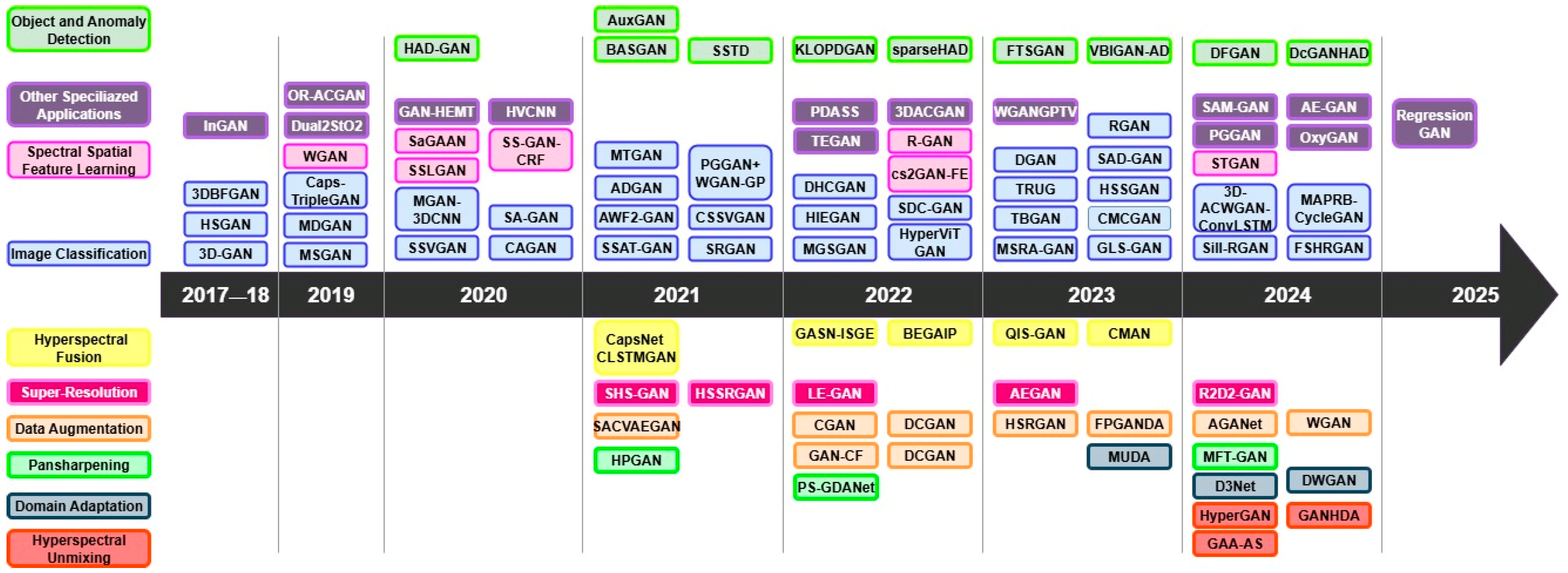

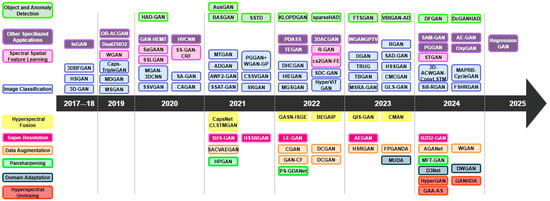

The integration of GANs into HSI has transformed the field, showcasing an extraordinary journey of computational advancements from 2017 to 2025, as summarized in Figure 7. This review captures the chronological evolution of HSI-specific GAN architectures, highlighting their growing sophistication and expanding applications across diverse domains. The reference is given in Table 2.

Figure 7.

HSI-specific GANs proposed in the literature sorted by domain and year.

Table 2.

GANs in HSI discovered in the literature (Listing with References).

4.2. Evolution of GAN-Based HSI Classification

HSI classification has been a primary driver of early and sustained adoption of GANs in HSI research for instance models like SSVGAN [118], HIEGAN [86], CMAN [71]. The chronological evolution of GAN-based classification reflects a gradual shift from generic adversarial frameworks toward HSI-specific, mechanism-aware architectures. Early efforts (2017–2019), including models such as 3DBFGAN and TripleGAN, primarily employed semi-supervised learning to address limited labeled data. These models demonstrated the feasibility of adversarial learning for hyperspectral classification but suffered from spectral distortion and training instability due to the high dimensionality of hyperspectral data. Between 2020 and 2021, research progressed toward explicit spectral–spatial modeling using 3D convolutions, capsule networks, and recurrent architectures. The adoption of Wasserstein-based losses and gradient penalties improved training stability and enabled GAN-based classifiers to scale to standard hyperspectral benchmarks, achieving competitive classification performance. From 2022 onward, attention mechanisms and refined loss formulations became prominent. Models incorporating spectral and spatial attention, spectral angle distance constraints, and class-conditional objectives improved robustness to spectral redundancy and mixed pixels, particularly under label-scarce settings. Recent developments (2024–2025) have introduced transformer-based and physics-guided GANs, enabling long-range spectral dependency modeling and improved cross-domain generalization. While these architectures achieve state-of-the-art performance, they also introduce higher computational complexity, motivating research into lightweight and deployable GAN-based classification frameworks. A chronological summary of GAN-based HSI classification models is presented in Table 2, with related advances in anomaly detection and other tasks discussed in subsequent sections.

4.3. HSI Object and Anomaly Detection Based on GAN

The evolution of GAN-based anomaly detection in HSI has been a fascinating journey, reflecting the dynamic interplay between innovation and practicality. In 2020, models like HAD-GAN [108] laid the groundwork with foundational unsupervised approaches. However, these early attempts grappled with noise sensitivity, underscoring the need for more robust designs.

By 2021, the field expanded its horizons with the introduction of models like SSTD [75] and BASGAN [68]. These architectures pushed the boundaries of spectral learning, incorporating separability constraints to enhance detection accuracy. Yet, scalability issues emerged as a critical bottleneck, prompting researchers to rethink their strategies for handling large-scale data.

The period from 2022 to 2024 saw a paradigm shift toward practical deployment and autonomy. Models like KLOPDGAN [90] eliminated the dependency on manual labeling, significantly simplifying workflows. Meanwhile, DFGAN [45] introduced decentralized federated learning, achieving a 17.3% reduction in training time while addressing the demand for distributed data handling. Despite these advancements, challenges in synchronization within decentralized architectures highlighted the evolving nature of the field.

4.4. HSI Super-Resolution (SR) Models Based on GAN

The integration of GANs into HSI SR has progressively redefined the balance between spectral fidelity and spatial resolution. The journey began in 2021 with HSSRGAN [87], which introduced dual-network architecture utilizing dense residual blocks to reduce over-smoothing. However, it faced challenges in managing the computational demands required for high-band spectral fidelity. At the same time, SHSGAN [50] innovatively synthesized hyperspectral cubes from RGB images, enhancing data augmentation capabilities, though its focus on the visible spectrum restricted its use in remote sensing. By 2023, advancements continued with AE-GAN [124], which incorporated attention mechanisms and a U-Net discriminator to improve training stability and feature discrimination. Despite these improvements, its increased complexity raised concerns about computational efficiency. In 2024, R2D2-GAN [38] bridged the HSI distribution gap through a game-theoretic approach and dynamic adversarial loss, demonstrating notable potential in biomedical applications. Future work must now focus on creating streamlined architectures for real-time use, while maintaining a balance between spatial enhancement and spectral fidelity, particularly in biomedical imaging and remote sensing.

4.5. HSI Fusion Models Based on GAN

In 2021, CLSTMGAN [91] leveraged Capsule Networks and Convolutional LSTMs for artificial sample generation, improving contextual feature extraction de- spite persistent computational overhead. By 2022, GASN-ISGE [69] fused panchromatic and hyperspectral data to enhance spectral and spatial resolutions, though its segmentation-based injection required precise parameter tuning. In 2023, QIS-GAN [15] introduced lightweight hierarchical sampling to balance performance and size, while CMAN [71] employed multi-attention mechanisms and coupled autoencoders for high-resolution outputs, albeit with computational challenges.

4.6. HSI Pan Sharpening Models Based on GAN

Hyperspectral pan-sharpening merges high-resolution panchromatic and low-resolution HSI. In 2021, HPGAN [93] introduced a 3D spectral-spatial GAN with optimized constraints for sensor generalization, though its architecture remained computationally demanding. By 2024, MFT-GAN [85] employed transformers with multiscale feature guidance to improve fidelity in pansharpened images, but its reliance on transformer-based discriminators increased resource demands.

4.7. HSI Unmixing Models Based on GANs

The year 2024 marked notable advancements in GAN-based unmixing. GAN [88], LE-GAN [104], and GAA-AS [56] tackled the challenge of labeling scarcity by employing domain adaptation to transfer knowledge from labeled to unlabeled datasets, bridging critical gaps. Meanwhile, HyperGAN [46] leveraged a conditional GAN with a patch transformer for spectral unmixing, delivering state-of-the-art results, albeit at the cost of increased training complexity.

4.8. HSI Domain Adaptation Models Based on GANs

Recent strides in GAN-based domain adaptation have addressed challenges such as limited data and mode collapse. GANHDA [88], MUDA [76] and MTGAN [100] introduced multitask learning for simultaneous reconstruction and classification, enhancing generalization capabilities. PDASS [47] achieved an MPSNR of 47.56 by improving spectral reconstruction using RGB-derived hyperspectral data. MS-GAN [4] advanced classification accuracy with a spatial-spectral discriminator, though careful optimization was essential. By augmenting datasets, 3DACGAN [96] improved anomaly detection, while DHCGAN [99] mitigated mode collapse through a dual hybrid convolution approach. Further innovations included LE-GAN [104], which used a latent encoder for super-resolution to enhance spectral fidelity, and TBGAN [12], which addressed complex data structures to boost classification performance. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in balancing computational efficiency with model complexity, addressing scalability issues, and improving robustness for real-world applications [53,102,125,126].

Based on evolution, Table 3 summarizes critical gaps in the literature.

Table 3.

Critical Gaps in HSI GAN Applications.

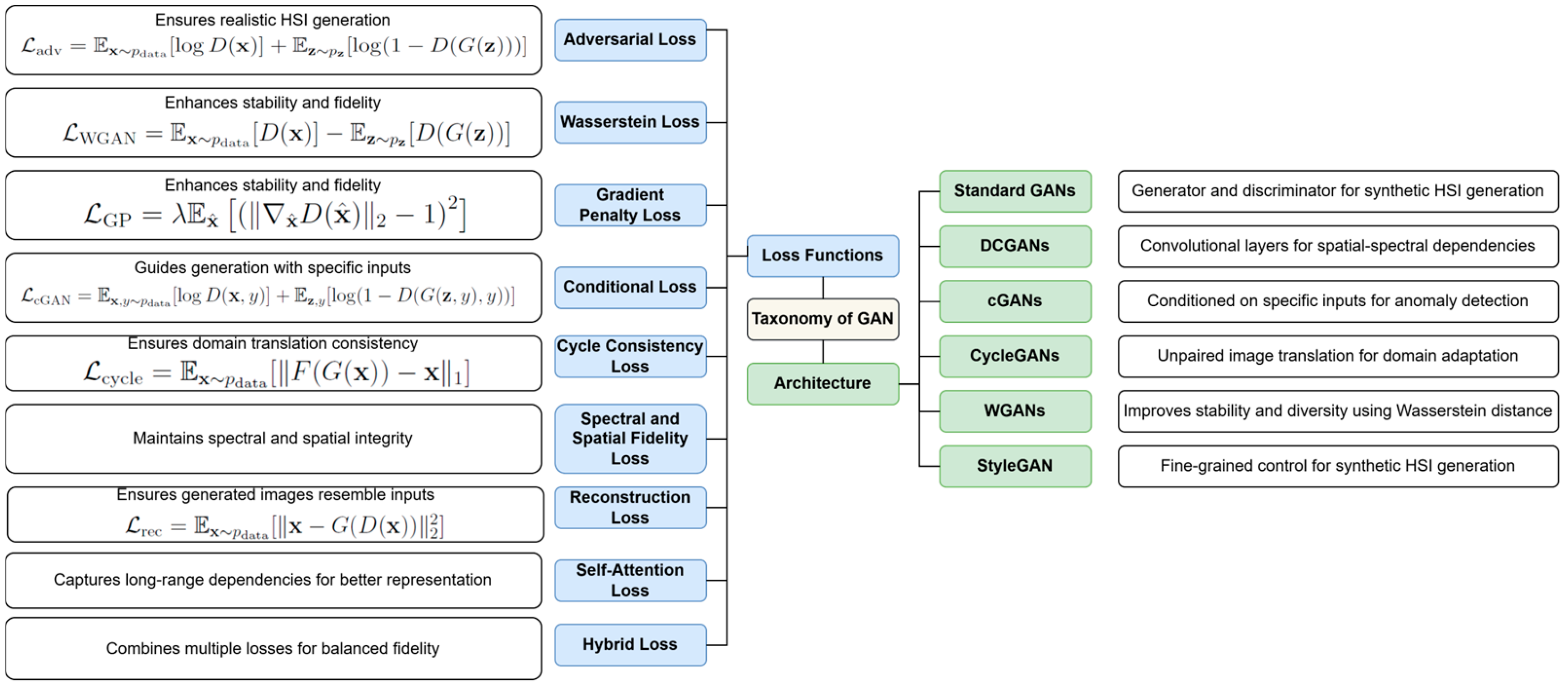

5. Taxonomy of GANs in HSI and Hyperparameter Tuning

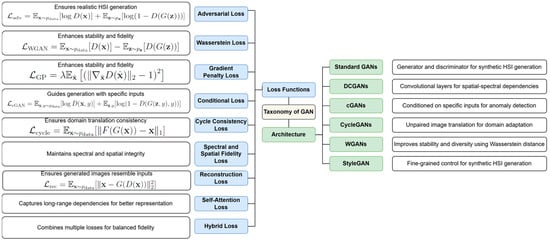

Section 5 presents a hierarchical taxonomy of GANs in HSI focusing on foundational architecture (Tier 1) and HSI-adapted loss and architectural extensions (Tier 2) (Figure 8). Task-oriented categorization is addressed through the chronological application-specific analysis in Section 4.

Figure 8.

Taxonomy of GANs [Standard GANs [53], DCGANs [44,52,74,77], cGANs [47,115], CycleGANs [44,52], WGANs [16,43,66,106,110], StyleGANs [50], Adversarial Loss [59,68], Wasserstein Loss [16,43,70,106,110], Gradient Penalty Loss [70,117], Conditional Loss [47,115], Cycle Consistency Loss [44,74], Spectral and Spatial Fidelity Loss [63], Reconstruction Loss [57,104], Self-Attention Loss [60,122], Hybrid Loss [79,86]].

5.1. Tier 1—Foundational GAN Architectures

These correspond to the diagram’s right column:

- Standard GANs: foundational adversarial generators and discriminators used for early HSI synthesis and semi-supervised classification (e.g., 3DBFGAN [116], TripleGAN [119]).

- DCGANs: convolution-driven architectures that model spatial–spectral features more effectively (e.g., DcGAN-HAD [52]).

- cGANs: conditional GANs guided by class labels or anomaly signatures (e.g., ADGAN [72], GAN-CF [49]).

- CycleGANs: unpaired domain translation models widely used for domain adaptation (e.g., MUDA [76], MAPRB-CycleGAN [94]).

- WGANs/TV-WGAN-GP: architectures improving stability and spectral fidelity via Wasserstein and gradient-penalty losses (e.g., TV-WGAN-GP [66], PG-WGAN-GP [70]).

- StyleGAN variants: used for fine-grained spectral manipulation and high-quality synthetic HSI generation (e.g., BEGAIP [84]).

5.2. Tier 2—HSI-Adapted Architecture Extensions (Mapped to the Loss Branch)

In practice, these losses define the modifications that differentiate Tier 2 HSI-specific GANs from Tier 1 foundational GANs. These are described below:

- Adversarial Loss → used universally across all architectures.

- Wasserstein + Gradient Penalty Loss → enables stable spectral reconstruction (used in TV-WGAN-GP [66], 3DACWGAN [98]).

- Conditional Loss → enables guided reconstruction/classification (used in cGAN-based ADGAN [72], GAN-CF [49]).

- Cycle Consistency Loss → essential for domain adaptation (used in MUDA [76], MAPRB-CycleGAN [94]).

- Spectral and Spatial Fidelity Loss → maintains spectral integrity (used in PDASS [47], Sill-RGAN [3]).

- Reconstruction Loss → central to SR and unmixing (used in R2D2-GAN [38], HSSRGAN [87]).

- Self-Attention Loss → drives long-range spectral dependency modeling (used in SAGAN [114], SSAT-GAN [13]).

- Hybrid Loss → multiloss balancing found in transformer-based and physics-guided models (HyperViTGAN [63], LE-GAN [104]).

5.3. Computational Characteristics and Resource Considerations

Because GAN-based solutions for HSI vary significantly in computational cost, practitioners benefit from a clear understanding of the trade-offs that influence feasibility in real-world deployments. Architectures such as SSVGAN [118], QIS-GAN [15], and AEGAN [78] maintain relatively small parameter sizes and shallow generator–discriminator designs, making them suitable for low-resource environments. Models incorporating attention (e.g., SAGAN [114], SSAT-GAN [13]) or multi-branch encoders (e.g., HIEGAN [86], MGSGAN [62]) require more computational resources, reflecting increased spectral modeling capacity.

High-complexity architectures—such as transformer-driven models (HyperViTGAN [63], TEGAN [79]), evolutionary-trainable GANs (HIEGAN [86]), and physics-guided multi-loss frameworks (PDASS [47], LE-GAN [104])—demand larger GPU memory allocations and longer training times. Dual-discriminator systems (e.g., R2D2-GAN [38], DFGAN [45]) incur additional computational overhead but yield enhanced spectral consistency and robustness. Providing computational metrics in a comparative table enables researchers to match GAN models to constraints in hardware, data volume, and application context.

5.4. Advantages, Limitations, and Recommended Use Cases of GAN-Based HSI Models

Given the breadth of GAN architectures applied to HSI, a clear articulation of model advantages and limitations is essential for guiding practitioners toward appropriate design choices. This section synthesizes insights across representative GAN-based HSI methods and contextualizes their suitability for specific application domains.

5.4.1. Multiscale and Fusion-Oriented Models

Architectures such as MFT-GAN [85], QIS-GAN [15], and GAN-CF [49] are designed to enhance spatial fidelity while maintaining spectral consistency, making them particularly effective for pan sharpening, image fusion, and super-resolution tasks. Their multiscale attention mechanisms and hierarchical feature extraction strategies yield strong reconstruction performance. However, these models often require substantial memory and computational resources and may exhibit longer convergence times when trained on large-scale datasets.

5.4.2. Federated and Distributed Learning Models

Models such as DFGAN [45], GANHDA [88], and related domain-adaptive architectures introduce distributed training protocols that allow for decentralized learning across multiple sensing nodes. These methods are highly suitable for federated change detection, privacy-preserving learning, and cross-sensor generalization. Their primary limitations include synchronization overhead, communication latency, and sensitivity to heterogeneous data distributions across participating clients.

5.4.3. Transformer-Enhanced Spectral Models

Architectures such as HyperViTGAN [63] and TEGAN [79] incorporate transformer blocks to capture long-range spectral dependencies. These models demonstrate state-of-the-art performance in spectral reconstruction and fine-grained classification. However, they are computationally intensive, exhibit high GPU memory demands, and may be less suitable for time-sensitive or resource-constrained deployments.

5.4.4. Physics-Guided and Fidelity-Constrained Models

Models such as PDASS [47], LE-GAN [104], and Sill-RGAN [3] incorporate physics-based constraints, spectral fidelity terms, or illumination-aware modules to produce physically plausible spectra. These approaches excel in spectral unmixing, anomaly detection, and reconstruction under variable environmental conditions. Their limitations stem from the need for domain knowledge to design appropriate constraints and potential difficulties in generalizing across different sensors.

5.4.5. Classification-Oriented Semi-Supervised Models

Approaches such as SSVGAN [118], HIEGAN [86], and SS-GAN-CRF [121] leverage semi-supervised learning to address label scarcity in HSI classification. These models offer improved generalization with limited annotated data. However, they can be sensitive to the quality of unlabeled samples and may require careful regularization to avoid mode collapse in imbalanced scenarios.

5.4.6. Dual-Discriminator and High-Fidelity Reconstruction Models

Models such as R2D2-GAN [38] and HSSRGAN [87] employ dual-discriminator designs or specialized fidelity losses to preserve fine spectral details. These architectures are highly suitable for biomedical HSI, high-resolution reconstruction, and tasks requiring precise material identification. The trade-offs include increased training complexity and reduced efficiency due to multi-branch discriminator optimization.

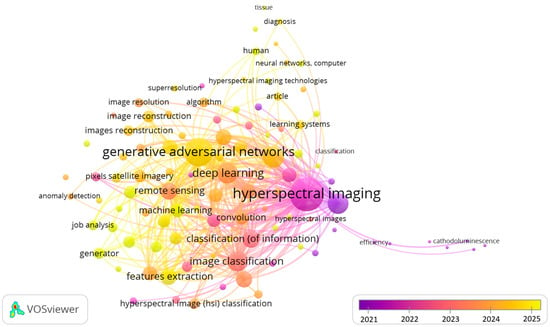

6. Research Directions for Future Work

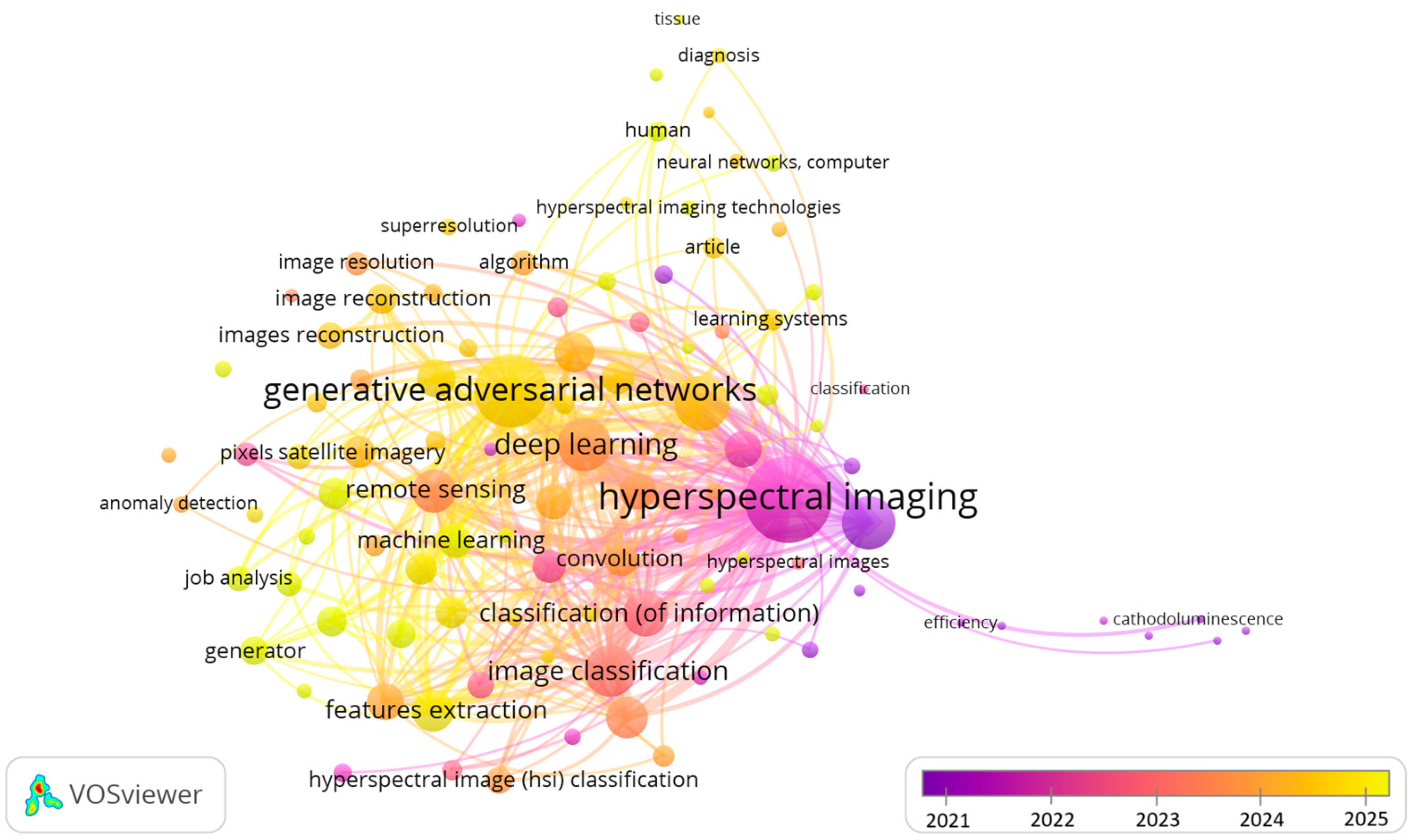

Despite the substantial progress made in HSI and its integration with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), several research challenges and opportunities remain. These gaps provide fertile ground for innovation, particularly in addressing methodological limitations and extending applicability across diverse domains. The keyword occurrence chart in Figure 9 highlights major focus areas such as anomaly detection, classification, resolution enhancement, multimodal fusion, computational efficiency, and explainability, thereby guiding future research priorities.

Figure 9.

Keyword Occurrence Chart.

6.1. Computational Efficiency Optimization

A major bottleneck in deploying GANs for hyperspectral analysis is their high computational and memory requirements. State-of-the-art architectures such as Caps-TripleGAN [119], transformer-based models (e.g., HyperViTGAN [63]), and attention-heavy frameworks often require extensive training time and resources, limiting scalability and real-time deployment. The keyword chart also emphasizes “computational efficiency” as a recurring concern. Future research should prioritize energy-efficient architectures through model pruning, quantization, lightweight transformer approximations, and federated or decentralized learning strategies. These approaches would reduce computational overhead, lower carbon footprints, and enable deployment in resource-constrained and edge-computing environments.

6.2. Optimization Strategies and Hyperparameter Sensitivity

Hyperparameter configurations reported for GAN-based hyperspectral models vary significantly across studies, particularly with respect to learning rate, batch size, optimizer choice, and loss formulation. Such variability complicates reproducibility and fair performance comparison. A comparative summary of commonly used hyperparameters for GAN-based HSI classification models is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hyperparameters for GAN based Classification Models for HSI.

Similarly, GAN-based object detection and anomaly detection models employ diverse optimization strategies and loss formulations reflecting task-specific requirements. The corresponding training configurations are summarized in Table 5. Future work should explore automated hyperparameter optimization, adaptive loss balancing, and standardized training protocols to improve robustness and reproducibility.

Table 5.

Hyperparameters for Object Detection and Anomaly Detection Models.

6.3. Expanding Object/Anomaly Detection Capabilities

Hyperspectral anomaly and object detection remain critical application areas where GANs can make a transformative impact. Recent advances, such as LRR-Net [127] and spectral-constrained GANs [90], have demonstrated promising results, consistent with the strong emphasis on “anomaly detection” observed in the keyword chart. However, scalability to large datasets and generalization across diverse environments remain unresolved challenges. Future research should emphasize unsupervised and semi-supervised frameworks capable of handling domain shifts with minimal labeled data. Hybrid approaches combining GANs with traditional detection techniques may further balance detection accuracy and computational efficiency [128,129].

6.4. Enhancing Image Resolution and Reconstruction

The use of GANs for HSI resolution and reconstruction has shown promise in recent studies [6,8,26,93]. However, challenges such as spectral distortion and loss of spatial details persist. The keyword chart highlights terms such as “image reconstruction” and “resolution enhancement,” reflecting the community’s focus on this area. Advanced architectures like Residual Dense Networks [95,101] or the integration of attention mechanisms, as seen in SRGAN [57] and ESRGAN [122] for natural images, could be adapted for hyperspectral data. Additionally, multi-task GAN frameworks that simultaneously optimize resolution enhancement and classification accuracy could prove beneficial.

6.5. Multimodal and Cross-Modal Fusion

The integration of hyperspectral data with multimodal datasets, such as LiDAR or RGB imagery, presents a significant opportunity for holistic environmental monitoring and precision agriculture. The prominence of terms like “multimodal fusion” in the keyword chart indicates the increasing interest in this area. While GAN-based approaches have been extensively used for single-modality HSI analysis, there is limited exploration of their capabilities in fusing multimodal information. Future research could develop GAN architectures capable of synthesizing complementary data modalities to improve both spatial and spectral representation.

6.6. Foundation Models and Large-Scale Representation Learning

Recent advances in foundation models, including large-scale vision and multimodal architectures, present significant potential for hyperspectral image (HSI) analysis. By leveraging self-supervised and pretraining paradigms on large, diverse datasets, foundation models can learn generalized spectral–spatial representations that transfer effectively across downstream HSI tasks such as classification, unmixing, anomaly detection, and domain adaptation. When integrated with GAN frameworks, foundation models can serve as robust encoders, discriminators, or conditioning modules, enhancing data efficiency and generalization, particularly in few-shot and cross-domain scenarios. Despite their promise, challenges remain in adapting foundation models to the high dimensionality and limited availability of labeled hyperspectral data, highlighting an important direction for future GAN–HSI research.

6.7. Domain Adaptation for Cross-Environment Applications

Domain adaptation and class-balancing techniques have enabled knowledge transfer across hyperspectral datasets acquired under different environmental conditions and sensor configurations [130]. The prominence of keywords such as “domain adaptation” and “cross-domain learning” underscores their growing importance.

However, existing methods often require extensive retraining and lack robustness in real-world scenarios. Future work should explore class-aligned and self-supervised GAN frameworks that dynamically adapt to new domains while preserving spectral consistency and minimizing retraining costs.

6.8. Application-Specific Innovations

Emerging applications, including food quality assessment [24,74,94] and disease diagnosis [131], demonstrate the versatility of GAN-enabled HSI. Keywords such as “food spectroscopy” and “disease detection” reflect increasing attention to these domains.

These applications often require customized architectures capable of handling domain-specific constraints, such as lighting variability, object texture, and limited data availability. Lightweight GAN models with domain-specific pretraining may enhance robustness and deployability in such settings.

6.9. Ethical, Explainable, and Trustworthy AI in HSI

As GAN-based HSI models are increasingly deployed in sensitive domains—including defense, agriculture, medical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring—ethical, societal, and technical concerns warrant systematic attention. The growing occurrence of keywords such as “explainability,” “fairness,” and “privacy” highlights the community’s awareness of these issues.

The authenticity and spectral fidelity of GAN-generated data remain central concerns, particularly in reconstruction-oriented models such as SRGAN [57], HSSRGAN [87], and Sill-RGAN [3]. Unvalidated synthetic spectra may distort material signatures and bias downstream decision-making. Dual-use risks also arise in surveillance and defense contexts, where advanced reconstruction capabilities may enable intrusive monitoring.

Furthermore, fairness and bias mitigation are critical, as GANs trained on geographically or demographically biased datasets may exhibit uneven generalization. Future research should prioritize explainable GAN architectures, uncertainty quantification, fairness-aware learning, and transparent reporting of data provenance. Sustainable AI practices—through computationally efficient and energy-conscious design—must also be integrated into GAN-HSI research.

The fusion of GANs and HSI has enabled substantial advances in anomaly detection, classification, and image reconstruction. However, continued progress depends on addressing challenges related to efficiency, robustness, multimodal integration, explainability, and ethical responsibility. By aligning future research with these thematic priorities, the community can ensure that GAN-based HSI technologies evolve in a scientifically rigorous, socially responsible, and practically deployable manner.

The integration of GANs with HSI introduces ethical and interpretability challenges, particularly when synthetic data are used in high-impact applications such as mineral exploration and agricultural quality assessment. In mineral mapping, GAN-generated spectra may deviate from physically valid reflectance signatures, potentially leading to mineral misidentification if not rigorously validated. Similarly, in agriculture, synthetic HSI samples may introduce unrealistic crop stress or quality indicators, affecting decision-making in yield assessment or food safety.

To mitigate these risks, recent studies emphasize physics-guided GANs, cross-validation with spectral libraries, and expert-in-the-loop verification to ensure spectral fidelity of synthetic data. Additionally, uncertainty quantification mechanisms can help flag unreliable GAN-generated samples before deployment.

Model interpretability is equally critical for responsible adoption. Recent advances incorporate saliency and attention map–based GAN frameworks, enabling visualization of influential spectral bands and spatial regions in tasks such as HSI anomaly detection and classification. These techniques help distinguish true spectral anomalies from noise or generative artifacts, improving transparency and trust. Integrating explainability modules within GAN architectures or using post-hoc attribution methods aligns naturally with the proposed taxonomy and supports ethical, accountable use of GAN-HSI models.

7. Conclusions

This survey has presented a comprehensive analysis of how GANs can be integrated with HSI to advance tasks ranging from anomaly detection and feature extraction to resolution enhancement and classification. Our findings confirm that GAN-based approaches have already made significant headway in mitigating some of the inherent complexities of high-dimensional hyperspectral data. The review reveals that critical gaps still impede broader adoption and real-world scalability. Many proposed models face high computational overheads, limiting their deployment on resource-constrained devices; others exhibit environmental vulnerability or struggle with spectral–spatial balancing. These shortcomings highlight the urgent need for more efficient, adaptable, and robust architecture. Furthermore, a closer examination of community-driven keyword trends indicates growing interest in multimodal data fusion, domain adaptation, and explainable AI—elements poised to become transformative in the next wave of GAN–HSI research. Multimodal fusion could involve synthesizing complementary information from LiDAR, RGB, or other sensor data, thus enriching spatial representation and bolstering model generalization. Likewise, domain adaptation remains essential for real-world applications, as HSI often spans diverse environments and sensor modalities. Yet these techniques, while promising, require further refinement to ensure that models adapt reliably without exhaustive retraining or intricate parameter tuning. The review also underscores a rising emphasis on interpretability and ethics, pointing to the need for transparent and accountable GAN-based solutions, particularly in high-stakes domains such as healthcare and defense. Looking ahead, the field would benefit substantially from hybrid approaches that combine GAN-based synthesis with classic detection or classification strategies, potentially balancing computational demands with state-of-the-art performance. Optimization strategies such as pruning, quantization, and federated learning can also help manage resource requirements and carbon footprints. Ultimately, the rich interplay of emerging techniques such as attention-driven architecture, domain-specific pretraining, and self-supervised learning reveals a dynamic research landscape where innovative solutions to computational efficiency, explainability, and multimodality will shape the future. By tackling these challenges, researchers and practitioners can unlock the full potential of GAN–HSI integration across an array of practical applications, ensuring robust, interpretable, and scalable implementations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R. and R.K.; methodology, S.A.; software, A.N.; validation, P.R. and R.K.; formal analysis, A.N.; investigation, S.A.; resources, S.A.; data curation, P.R. and R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.; writing—review and editing, P.R., A.N., S.A. and R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be downloaded from this link https://www.ehu.eus/ccwintco/index.php/Hyperspectral_Remote_Sensing_Scenes, accessed on 30 August 2025.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIS | Hyperspectral Data |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ML | Machine Learning |

Appendix A

Table A1 shows the HSI datasets used in the literature.

Table A1.

Common Hyperspectral Datasets Used in GAN-Based HSI Research.

Table A1.

Common Hyperspectral Datasets Used in GAN-Based HSI Research.

| Dataset | Sensor/Platform | Bands | Wavelength Range | Spatial Resolution | Scene Type | Typical GAN-HSI Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Pines [17] | AVIRIS | 200 | 0.4–2.5 µm | 20 m | Agricultural fields | Classification, anomaly detection, domain adaptation |

| Salinas [17] | AVIRIS | 204 | 0.4–2.5 µm | 3.7 m | Agriculture (high-resolution) | Classification, super-resolution, reconstruction |

| Pavia University [17] | ROSIS | 103 | 0.43–0.86 µm | 1.3 m | Urban campus | Classification, denoising, SR |

| Pavia Center [17] | ROSIS | 102 | 0.43–0.86 µm | 1.3 m | Urban area | Classification, domain adaptation |

| Houston 2013 [17] | CASI | 144 | 0.38–1.05 µm | 2.5 m | Urban (multi-class) | Classification, domain adaptation, change detection |

| Botswana [17] | Hyperion | 242 | 0.4–2.5 µm | 30 m | Wetlands/Savanna | Classification, anomaly detection |

| Kennedy Space Center (KSC) [17] | AVIRIS | 176 | 0.4–2.5 µm | 18 m | Coastal/Vegetation | Classification, spectral unmixing |

| CAVE [132] | CAVE Multispectral Camera | 31 | 0.4–0.7 µm | ~1 mm/pixel | Indoor scenes/objects | Super-resolution, spectral reconstruction, GAN training |

| Harvard Scene Dataset [133] | Custom HS Camera | 31 | 420–720 nm | Varies | Indoor objects, natural scenes | Super-resolution, spectral reconstruction |

| Chikusei [134] | Headwall Hyperspec | 128 | 0.36–1.0 µm | 2.5 m | Agricultural/residential | Classification, SR, fusion |

| UAV-HSI [135] | Headwall, Cubert sensors | 50–270 | Visible–NIR | 0.03–0.3 m | Precision agriculture, forestry | Super-resolution, anomaly detection, lightweight GAN evaluation |

| HyRANK Benchmark [130] | ROSIS/Hyperion | 200–242 | Visible–SWIR | 30 m | Mixed land-cover | Domain adaptation, classification |

| PU-Net Multispectral [136] | Multiple UAV sensors | 5–13 | Visible–NIR | cm-level | Agriculture/forestry | GAN fusion, SR, data augmentation |

| Medical HSI (Skin/Tissue) [137] | Various biomedical HSI cameras | 31–200 | Visible–NIR | Sub-mm | Biomedical imaging | Spectral reconstruction, anomaly detection, generative modeling |

References

- Keshava, N.; Mustard, J.F. Spectral unmixing. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2002, 19, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, Y.; Ghamisi, P.; Benediktsson, J.A. Generative adversarial networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 5046–5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cui, W. Robust hyperspectral image classification using generative adversarial networks. Inf. Sci. 2024, 666, 120452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Cao, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, L. Classification of hyperspectral images based on multiclass spatial–spectral generative adversarial networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 5329–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; You, J.; Lee, J. HSIGAN: A conditional hyperspectral image synthesis method with auxiliary classifier. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 3330–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. A review of hyperspectral image super-resolution based on deep learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y. Information leakage in deep learning-based hyperspectral image classification: A survey. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, D.; Olaniyi, E.; Huang, Y. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) for image augmentation in agriculture: A systematic review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Zhou, J.; Jia, S. Unsupervised spatial-spectral cnn-based feature learning for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5524617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharram, M.A.; Sundaram, D.M. Land use and land cover classification with hyperspectral data: A comprehensive review of methods, challenges and future directions. Neurocomputing 2023, 536, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Hou, S.; Xiao, S.; Qu, J.; Du, Q.; Li, Y. Generative dual-adversarial network with spectral fidelity and spatial enhancement for hyperspectral pansharpening. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 7303–7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Tang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C. Two-branch generative adversarial network with multiscale connections for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Access 2022, 11, 7336–7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Bao, W.; Shen, X.; Zhang, X. Spectral–spatial attention feature extraction for hyperspectral image classification based on generative adversarial network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 10017–10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, R.S.; Rambabu, M.; Dua, Y. Deep learning for hyperspectral image classification: A survey. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2024, 53, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Deng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, L.J.; Wu, Q. QIS-GAN: A lightweight adversarial network with quadtree implicit sampling for multispectral and hyperspectral image fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5531115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Girdhar, A.; Ankur; Kumar, R. A novel spectral-spatial 3D auxiliary conditional GAN integrated convolutional LSTM for hyperspectral image classification. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 5251–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Girdhar, A. A comprehensive systematic review of deep learning methods for hyperspectral images classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 6221–6306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, B.; Song, Y.; Zhang, B. Transfer Learning of Spatial Features from High-resolution RGB Images for Large-scale and Robust Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5505732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Kumar, R.; Girdhar, A. A 3D-convolutional-autoencoder embedded Siamese-attention-network for classification of hyperspectral images. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 8335–8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.J.; Yang, M.L.; Li, H.C.; Long, C.F.; Fang, K.; Du, Q. Feature Dimensionality Reduction with L2,p-Norm-Based Robust Embedding Regression for Classification of Hyperspectral Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5509314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, B.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, J.; Liu, P.; Li, X. A review of deep learning used in the hyperspectral image analysis for agriculture. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 5205–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.R.; Singh, S.K. Transformer-based generative adversarial networks in computer vision: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 4851–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X. Semisupervised hyperspectral image classification based on generative adversarial networks and spectral angle distance. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Hu, Y.; Ma, B.; Yu, G.; Li, Y. An improved DCGAN model: Data augmentation of hyperspectral image for identification pesticide residues of Hami melon. Food Control 2024, 157, 110168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhou, Z.; Shang, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, L. Class-aligned and class-balancing generative domain adaptation for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5509617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Girdhar, A. Deep Siamese network with handcrafted feature extraction for hyperspectral image classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 2501–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, P.; Girdhar, A. Xcep-Dense: A novel lightweight extreme inception model for hyperspectral image classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 5204–5230. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, P.; Gupta, G. A Cross-Domain Semi-Supervised Zero-Shot Learning Model for the Classification of Hyperspectral Images. J. Indian. Soc. Remote Sens. 2023, 51, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guerri, M.F.; Distante, C.; Spagnolo, P.; Bougourzi, F.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. Deep learning techniques for hyperspectral image analysis in agriculture: A review. ISPRS Open J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 3, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Al-qaness, M.A.; AL-Alimi, D.; Dahou, A.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Abualigah, L.; Ewees, A.A. Land use/land cover (LULC) classification using hyperspectral images: A review. Geo-Spatial Inf. Sci. 2024, 28, 345–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Luo, D.; Mu, J. A research review on deep learning combined with hyperspectral Imaging in multiscale agricultural sensing. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, Z.; Asaari, M.S.M.; Ibrahim, H.; Abidin, I.S.Z.; Ishak, M.K. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for Image Augmentation in Farming: A Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 179912–179943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, A.A.; Gebresilassie, B.G.; Mukherjee, A.; Hassija, V.; Chamola, V. Advancing Medical Imaging Through Generative Adversarial Networks: A Comprehensive Review and Future Prospects. Cognit. Comput. 2024, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Chehri, A.; Song, Y. A review of GAN-based super-resolution reconstruction for optical remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.; Patel, V. A comprehensive review: Active learning for hyperspectral image classifications. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 1975–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozdani, S.; Chen, D.; Pouliot, D.; Johnson, B.A. A review and meta-analysis of generative adversarial networks and their applications in remote sensing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 108, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Lee, W.; Jeong, K.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Jung, C.H. Efficient Mapping of Tissue Oxygen Saturation using Hyperspectral Imaging and GAN. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 153822–153831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Tian, J.H.; Su, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. R2D2-GAN: Robust Dual Discriminator Generative Adversarial Network for Microscopy Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 4064–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Ma, B.; Xu, Y.; Dang, F.; Yu, G.; Bian, H. An innovative variant based on generative adversarial network (GAN): Regression GAN combined with hyperspectral imaging to predict pesticide residue content of Hami melon. Spectrochim. Acta Part. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 325, 125086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, G.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, W.; Pan, X. AGANet: Attention-Guided Generative Adversarial Network for Corn Hyperspectral Images Augmentation. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 71, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yu, X. Hyperspectral target detection with an auxiliary generative adversarial network. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4454. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.; Huang, Z.; Jin, B.; Tang, Q.; Jia, L.; Zhao, G.; Cao, D.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, C. SAM-GAN: An improved DCGAN for rice seed viability determination using near-infrared hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Men, J.; Wu, L. Utilizing wasserstein generative adversarial networks for enhanced hyperspectral imaging: A novel approach to predict soluble sugar content in cherry tomatoes. LWT 2024, 206, 116585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Rao, Z.; Ji, H. Discrimination of unsound wheat kernels based on deep convolutional generative adversarial network and near-infrared hyperspectral imaging technology. Spectrochim. Acta Part. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 268, 120722. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Xu, X.; Li, Y. Decentralized Federated GAN for Hyperspectral Change Detection in Edge Computing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 8863–8874. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Dong, H.; Meng, H.; Jiao, L. Pixel-to-Abundance Translation: Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks Based on Patch Transformer for Hyperspectral Unmixing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 5734–5749. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Zou, Z. Physics-informed hyperspectral remote sensing image synthesis with deep conditional generative adversarial networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5528215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.Y.; Bie, S.H.; Chen, X.H.; Yu, W.K. Single-Pixel Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging via Physics-Guided Generative Adversarial Networks. Photonics 2024, 11, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Ma, Y.; Ren, G.; Wang, J. Aboveground biomass of salt-marsh vegetation in coastal wetlands: Sample expansion of in situ hyperspectral and Sentinel-2 data using a generative adversarial network. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 270, 112885. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, J.; Shtendel, G.; Zeligman, A.; Averbuch, A.; Nathan, M. SHS-GAN: Synthetic enhancement of a natural hyperspectral database. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2021, 7, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, R.; Chen, Z.; Gao, H.; Xu, S. Transformer-inspired stacked-GAN for hyperspectral target detection. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 4961–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, P.; Amali, S.A.M.J. Dual-discriminator conditional generative adversarial network optimized with hybrid manta ray foraging optimization and volcano eruption algorithm for hyperspectral anomaly detection. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122058. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Cao, W.; Tang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Y. ACTN: Adaptive coupling transformer network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5503115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Li, B. Pixel-Level and Global Similarity-Based Adversarial Autoencoder Network for Hyperspectral Unmixing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 7064–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, F.; Farooque, G.; Shao, Y.; Yang, J.; Xiao, L. DSSFT: Dual branch spectral-spatial feature fusion transformer network for hyperspectral image unmixing. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Su, Y.; Sun, H.; Bai, J.; Li, P.; Liu, F.; Liu, D. Generative Adversarial Autoencoder Network for Anti-Shadow Hyperspectral Unmixing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 5506005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fu, G.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y. Degradation learning for unsupervised hyperspectral image super-resolution based on generative adversarial network. Signal Image Video Process. 2021, 15, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Gong, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, H. Features kept generative adversarial network data augmentation strategy for hyperspectral image classification. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 142, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Po, L.M.; Lin, T.; Yan, Q.; Liu, W.; Xian, P. HSGAN: Hyperspectral reconstruction from RGB images with generative adversarial network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 34, 17137–17150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tong, L.; Qian, B.; Yu, J.; Xiao, C. Self-attention-based conditional variational auto-encoder generative adversarial networks for hyperspectral classification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3316. [Google Scholar]

- Dam, T.; Anavatti, S.G.; Abbass, H.A. Mixture of spectral generative adversarial networks for imbalanced hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 19, 5502005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, B.; Wei, Z. Cross-scene classification of hyperspectral images via generative adversarial network in latent space. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5526217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Xia, K.; Ghamisi, P.; Hu, Y.; Fan, S.; Zu, B. Hypervitgan: Semisupervised generative adversarial network with transformer for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 6053–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Gao, A.; Shang, R.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, L. Multi-complementary generative adversarial networks with contrastive learning for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5520018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, A.; Clarke, K.; Lewis, M. Generative adversarial network synthesis of hyperspectral vegetation data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wan, M.; Kong, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q.; Gu, G. Hybrid spatial-spectral generative adversarial network for hyperspectral image classification. JOSA A 2023, 40, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhao, N.; Shang, R.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, L. Self-supervised divide-and-conquer generative adversarial network for classification of hyperspectral images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5536517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Lei, J.; Du, Q. Characterization of background-anomaly separability with generative adversarial network for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 6017–6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Yang, Y.; Qu, J.; Xie, W.; Li, Y. Fusion of hyperspectral and panchromatic images using generative adversarial network and image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5508413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bai, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Pei, C. An optimized training method for GAN-based hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 18, 1791–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Sui, Y.; Yuan, Y. An unmixing-based multi-attention GAN for unsupervised hyperspectral and multispectral image fusion. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, F.; Dong, J.; Du, Q. Adaptive DropBlock-enhanced generative adversarial networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 5040–5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Xia, Y.; Ye, Y. Generative adversarial network with transformer for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 5510205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Nie, Q.; Ji, H.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; An, D. Hyperspectral imaging combined with generative adversarial network (GAN)-based data augmentation to identify haploid maize kernels. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 106, 104346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhang, J.; Lei, J.; Li, Y.; Jia, X. Self-spectral learning with GAN based spectral–spatial target detection for hyperspectral image. Neural Netw. 2021, 142, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Han, B.; Li, J.; Du, Y. Domain-invariant feature and generative adversarial network boundary enhancement for multi-source unsupervised hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; An, D. Near-infrared hyperspectral imaging technology combined with deep convolutional generative adversarial network to predict oil content of single maize kernel. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 131047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Xie, B.; Mei, S. Attention-enhanced generative adversarial network for hyperspectral imagery spatial super-resolution. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Lu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jiao, L. Generative adversarial networks based on transformer encoder and convolution block for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]