Highlights

What are the main findings?

- TPHiPr outperformed seven other gridded precipitation datasets in capturing Nepal’s complex rainfall patterns, especially at high altitudes.

- Rainfall-runoff erosivity (R-factor) is rising nationwide due to increased frequent and intense extreme precipitation, notably in high-altitude regions.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Soil erosion risk is increasing across Nepal, including areas with declining total rainfall, requiring targeted soil conservation in vulnerable zones.

- Watershed management policies must address both intensified monsoon erosion/flooding in central/eastern Nepal and elevated dry-season water scarcity in western Nepal.

Abstract

Nepal is highly vulnerable to severe soil erosion driven by monsoonal rainfall and rugged terrains. Limitations in ground observation networks have hindered comprehensive, high-resolution national assessment of precipitation and rainfall-runoff erosivity (R-factor) across Nepal. This study systematically evaluated eight global gridded precipitation datasets (GPDs) against data from 152 weather stations, identifying the optimal precipitation dataset (TPHiPr) representing Nepal’s complex topography. Based on this high-quality dataset, we provided the first independent, long-term (1979–2020), high-resolution national-scale assessment of precipitation and the R-factor for Nepal. Our analysis reveals that 1996 marked a turning point in nationwide precipitation trends: annual precipitation shifted from a decreasing to an increasing one in the humid eastern and central regions, while the drier western region transitioned from an increasing to a decreasing trend, particularly during the dry season. A clear spatial divergence was observed between total precipitation and the R-factor, highlighting the dominant role of precipitation frequency and intensity. Extreme precipitation events intensified significantly (e.g., days with ≥25 mm rainfall increased by 0.2 days yr−1, and the 95th percentile precipitation threshold increased by 0.4 mm yr−1, p < 0.01), driving a nationwide increase in the R-factor (6.3 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−2, p < 0.01), with high-altitude areas experiencing the most pronounced effects. We conclude that soil erosion risk has intensified nationwide due to increasing precipitation extremes. Watershed management must develop elevation-specific adaptation strategies that integrate climate science with practical solutions to address the dual challenges of intensified monsoon-driven erosion and growing dry-season water scarcity.

1. Introduction

The mountainous Himalayan region of Nepal faces severe soil erosion, driven by a confluence of natural and anthropogenic factors [1]. Earthquakes and glacial lake outburst floods are key natural triggers, while human activities like deforestation, overgrazing, intensive agriculture, and urbanization significantly exacerbate the problem [2]. Superimposed on these is the intense monsoon rainfall, which generates extreme hydrological conditions and high rainfall-runoff erosivity (R-factor), triggering widespread soil loss and landslides [3]. Historically, approximately 91% of Nepal’s population has relied on agriculture for their livelihoods, making these erosion-driven processes particularly devastating. Loss of top soils and landslides not only degrade farmland productivity but also cause downstream sedimentation, flooding, hydropower disruption, and dry-season water scarcity, critically impacting local communities and ecosystems [4,5,6]. The socioeconomic resilience and community livelihoods in Nepal are closely linked to the health of its water and soil resources. Therefore, accurately assessing changes in precipitation patterns and erosion risks under climate change is crucial for the country’s food security, sustainable development, and community adaptive capacity.

Assessing soil erosion at a broad scale often uses the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) and its revised model (RUSLE), which indicate that soil erosion is controlled by rainfall-runoff erosivity (R-factor), land cover (C-factor), soil erodibility (K-factor), and topography (LS-factor) [7,8,9]. The R-factor is one of the key drivers and has been well studied globally in the context of changing precipitation regimes [10,11,12]. Existing studies indicate that the intensity and frequency of extreme precipitation events in Nepal are continuously increasing, with spatial distribution patterns becoming increasingly variable. These changes are influenced by multiple factors, including the evolution of the South Asian monsoon system, teleconnection phenomena such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), and anthropogenic climate warming [13,14,15,16,17]. Concurrently, these shifts have made the spatiotemporal distribution of the R-factor more complex and difficult to predict. Therefore, characterizing precipitation and quantifying its erosive effects are challenging but crucial when assessing the impact of climate change on water resources such as soil erosion, water quality, and transportation infrastructure including road culverts [18,19].

Direct, long-term precipitation measurement across Nepal’s complex terrain is hindered by cost, accessibility, and high spatial variability [20,21]. Therefore, satellite-based observations and reanalysis models are often the only option for mapping continuous spatiotemporal precipitation patterns in regions with scarce ground observations [22,23]. Globally, gridded precipitation datasets (GPDs) were developed from in situ site observations, passive microwave remote sensing, infrared wave inversion, and simulation models. These methods aim to comprehensively integrate various precipitation factors and produce composite precipitation products for complex landscapes [24,25,26,27]. Although the accuracy of GPDs has significantly improved with the advancement of computing power and data technology, large discrepancies between precipitation amounts measured at local stations and GPDs remain in topographically complex regions like the Himalayas remains uncertain due to steep slopes, high cloud cover, and strong seasonality [28,29,30,31]. Rigorous assessments of these precipitation data are needed before they can be properly applied to address water resources management issues [12,15,32,33].

Previous studies on precipitation and the R-factor in Nepal face several known limitations: (1) Validations of GPDs often rely on sparse, short-record station networks with limited geographical and elevational coverage [24,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. (2) Few studies explicitly evaluate GPDs’ performance in reproducing extreme precipitation indices most relevant to erosion processes [16,42,43]. (3) R-factor estimates are derived from station-based annual aggregates or embedded within erosion models, lacking independent, long-term, high-resolution national mapping using spatially continuous data. These constraints impede a mechanistic understanding of erosivity trends and their socio-ecological implications, particularly for vulnerable agrarian communities [3,12,44,45,46,47].

This study provides a comprehensive, national-scale analysis of precipitation and the R-factor in Nepal from 1979 to 2020. We rigorously evaluate eight GPDs against a network of 152 weather stations to identify the dataset most capable of capturing Nepal’s complex rainfall climatology, particularly extreme events. Using the optimal dataset, we then quantify the long-term spatiotemporal trends and patterns of precipitation and the R-factor. Our work uniquely advances the field by: (1) conducting a systematic validation of GPDs over Nepal, explicitly focusing on their performance across altitudes and in reproducing extremes; (2) delivering the long-term, spatially continuous national mapping and trend analysis of the R-factor, independent of a full erosion model; and (3) revealing the spatially divergent trends in total precipitation extreme precipitation, and erosivity. These findings provide crucial high-resolution scientific evidence for soil and water conservation efforts in Nepal’s densely populated agricultural areas and ecologically fragile zones under changing climatic conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Nepal is situated between India and the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of China (80.1° E–88.2° E, 26.3° N–30.5° N) [48] (Figure 1). By longitude and administration, Nepal can be divided into Western, Central and Eastern regions, and each region has a belt-like distribution feature from south to north [49]. Nepal has four seasons [50]: Pre-monsoon (March to May), Monsoon (June to September), Post-monsoon (October to November), and Winter (December to February). About 80% of the precipitation in Nepal falls within the monsoon season, and much of this volume falls via a small number of extremely intense rainfall events [42]. Annual precipitation in the central regions can surpass 3000 mm, while the plains south of the middle hills typically receive precipitation ranging from 1500 to 2000 mm. In contrast, the high-altitude areas in the north may receive less than 1000 mm of precipitation annually (Figure 1b).

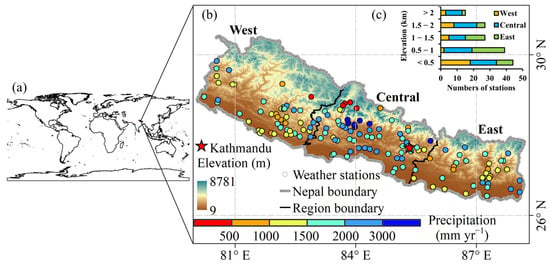

Figure 1.

Geographical locations of Nepal (a), regional division, distribution of elevation, ground meteorological observation stations and annual precipitation (b), and the distribution of the number of stations in different regions with altitude (c). In (b), the circles represent the spatial distribution of the 152 ground observation stations used in this study, and the color band shows the multi-year means of annual precipitation measured at the stations from 2001 to 2015.

Nepal has a population of approximately 30 million, with diverse community compositions. The population distribution is highly uneven, primarily concentrated in the Terai Plain and the valleys of the middle hills–areas with favorable climates and optimal agricultural conditions, typically at elevations below 3000 m [51]. Agriculture is the important economic sector in Nepal, with the majority of the population engaged in subsistence farming. Major crops include rice, maize, wheat and potatoes. Additionally, tourism (particularly trekking and mountaineering in the Himalayas), remittances from overseas workers, and the growing service sector serve as vital pillars of the economy [52]. This agriculture-based and natural landscape-based economic structure closely links the state of its ecosystems, as well as water and soil resources, to community livelihoods and national economic development.

2.2. Precipitation Datasets

The precipitation datasets used in this study include the daily ground observed data at the 152 weather stations and eight gridded precipitation datasets (GPDs) with different spatial and temporal resolutions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spatial and temporal information and data sources for the weather stations and the eight grided precipitation datasets (GPDs) used in this study.

2.2.1. Observed Precipitation Data

Daily observed precipitation data from 198 stations across Nepal spanning from 1971 to 2020 were acquired from the Nepal’s Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM). Among all the stations, 152 stations had data coverage of more than 90% from 2001 to 2015 with elevation ranging from 63 to 3671 m (Figure 1b). Over half of the weather stations were located in the low elevation zone (<1000 m) (Figure 1c). Only 64 stations (elevations < 2642 m) covered a longer time period (2001 to 2019). Hence, 152 weather stations covering the period from 2001 to 2015 were used for evaluating gridded precipitation datasets over Nepal.

2.2.2. Gridded Precipitation Datasets (GPDs)

Eight GPDs have the merits of high spatial and temporal resolution (spatial resolution ≤ 0.25°, temporal resolution ≤ 1 day) and long time series to investigate the general modes of precipitation and their accuracies (Table 1).

These eight GPDs are generated based on various data sources, mainly including satellite remote sensing, reanalysis, and rain gauge observations. Specifically, APHRODITE is a daily product based on spatial interpolation of dense rain gauge networks across Asia and is regarded as the “quasi-ground truth” in the region [53]. CHIRPS is a global high-resolution product that integrates satellite infrared data with station observations, optimized for drought monitoring and performs well in data-scarce regions [54,55]. ERA5-Land is a high-resolution land surface reanalysis dataset produced through numerical modeling and data assimilation [56,57]. IMERG integrates satellite, infrared, and rain gauge data, offering high spatiotemporal resolution [58,59,60]. MSWEP is a weighted ensemble product that merges satellite, reanalysis, and rain gauge data, dynamically adjusting weights based on the accuracy of the three sources across different regions and seasons [61,62,63]. PDIR-Now is a high-resolution infrared retrieval product based on artificial intelligence, with advantages of extremely low latency (near real-time) [64,65,66]. TPHiPr combines high-resolution WRF model simulations, machine learning-based downscaling, and over 9000 station observations to provide reliable precipitation data for the Third Pole region, supporting water cycle and ecosystem dynamics analysis in this region [27,67,68]. TRMM is a satellite mission specifically designed for monitoring tropical and subtropical precipitation. It utilizes infrared data from geostationary satellites for temporal interpolation and extrapolation, ultimately generating high spatiotemporal resolution precipitation products [69,70,71]. More detailed descriptions are provided in Text S1.

2.3. Data Analysis Methods

2.3.1. Precipitation Data Quality Control Methods

We performed temporal aggregation for the station precipitation data and standardized the minimum temporal resolution of gridded datasets to a daily scale. To mitigate uncertainty stemming from re-interpolation, the spatial resolution of the temporally aggregated data products remains unchanged. Instead, a pixel-to-point method is employed to extract the daily data at the corresponding longitude and latitude of each station [72,73].

The quality control of the aggregated precipitation for station data is as follows: (1) If there are 3 consecutive missing days in a month or if the missing data exceeds 10% of the total data volume in that month, the accumulated rainfall is marked as missing for the month; (2) If there are 30 consecutive missing days in a year or if the missing data exceeds 10% of the total data volume in that year, the accumulated rainfall is marked as missing for the year.

It is important to emphasize that no imputation or interpolation was applied to the daily station records used for the validation against GPDs. This conservative approach ensures that the evaluation of GPDs is based solely on periods of high data completeness, thereby avoiding biases that could arise from data imputation. For the comparative assessment of different GPDs at monthly and annual scales, which aims to illustrate inter-product variability rather than to validate against station data, isolated missing monthly values were filled using the long-term monthly mean of the respective product to generate continuous monthly and annual time series for cross-product comparison. Such interpolation was performed solely for supplementary visualization purposes.

2.3.2. Gridded Precipitation Datasets Validation Methods

Multiple indicators were used to comprehensively validate GPDs (Table 2). The selection of validation indicators follows established frameworks for evaluating precipitation products in complex terrain, aiming to assess overall accuracy, event detection capability, and performance in capturing extreme events relevant to erosion studies.

Table 2.

Indicators for assessing gridded precipitation datasets.

Three typical statistical indicators, Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (CC), Relative Bias (RB), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), were used to quantify the consistency between GPDs and ground observation data [24]. Four detection indicators, Critical Success Index (CSI), False Alarm Rate (FAR), Frequency Deviation Index (FBI), and Probability of Detection (POD), were used to evaluate the detection ability of GPDs for precipitation events of different intensities [68,74]. Three extreme precipitation indices, the number of heavy rainfall days (daily rainfall ≥ 25 mm) (R25d), the 95th percentile of rainfall (R95), and the maximum consecutive wet days (CWD), which respectively characterized the frequency, the intensity, and lengths of continuous precipitation days, were used to evaluate the ability of GPDs to capture extreme precipitation events [41,49,53,75]. The calculation formulas of the indicators are shown in Table 2. A detailed description of the methods used in this study can be found in Text S2, with the precipitation intensity classification scheme shown in Table S1.

2.3.3. R-Factor Calculation Methods

In consideration of the temporal resolution and continuity of the precipitation data used in this study, as well as the suitability for a national-scale investigation, a monthly model that has been extensively validated and widely applied in regional and global assessments of rainfall-runoff erosivity was ultimately selected [9,10,76]. This approach provides a robust methodological framework for generating continuous, nationwide estimates of the R-factor across complex terrain and for evaluating its long-term (decadal) spatiotemporal trends. The formula for calculating the R-factor is as follows:

where represents rainfall-runoff erosivity factor (MJ mm ha−1 hr−1 yr−1), represents the monthly precipitation (mm), represents the annual precipitation (mm).

2.3.4. Spatiotemporal Characteristic Analysis Methods

A linear trend model was fitted using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method to quantify the overall direction and magnitude of change over time [77]. The model is expressed as:

where is the observed value at time , is the intercept, is the trend slope (representing the rate of change per unit time), and is the random error term. The slope is estimated by minimizing the sum of squared residuals:

Here, is the length of the time series, and and are the mean of time indices and observed values, respectively. A positive indicates an increasing trend, while a negative value denotes a decreasing trend. The statistical significance of the trend was evaluated by a two-tailed t-test.

The non-parametric Sequential Mann-Kendall test was applied to detect potential abrupt changes (shift points) in the time series, which is robust to non-normal distributions and outliers [78]. For a series of length , the test statistic is calculated sequentially as:

where is the sign function. Under the null hypothesis of no abrupt change, the mean and variance of are:

The standardized statistic is then obtained as:

The same procedure is repeated for the reversed series to compute . If the curves of and intersect within the critical threshold lines ( for ), the intersection point is considered a potential abrupt change point. A moving-t test was further employed to verify the change points identified by the M-K test.

To examine the monotonic relationship between the studied variables and elevation, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used [79]. This method does not assume linearity and is suitable for data that may not follow a normal distribution. For variables and , the ranks and are assigned. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (CC) is calculated by the formula in Table 2, where . The value of CC ranges from −1 to +1, with larger absolute values indicating stronger monotonic association. The significance of the correlation was tested using the t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Validation of GPDs Using Ground Precipitation Observations

3.1.1. Mean Daily Precipitation by Altitude

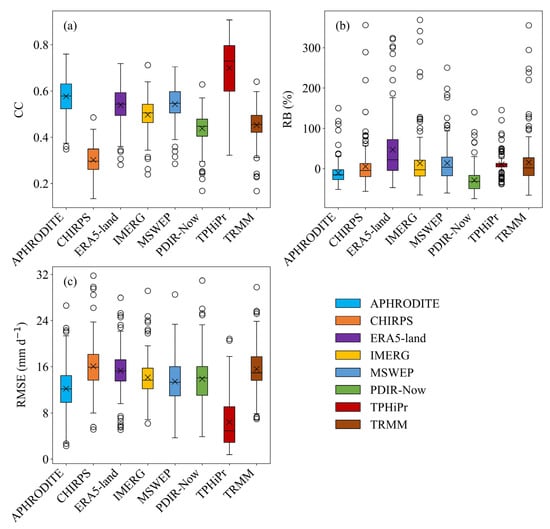

Among all GPDs, TPHiPr exhibited the highest consistency with the measured daily precipitation data as judged by the highest correlation coefficient (CC = 0.70) and the lowest RMSE (RMSE = 6.4 mm d−1) (Figure 2 and Figure S1). The second highest correlation with measured data was for APHRODITE with CC of 0.58 (Figure 2a). CHIRPS showed the lowest correlation with CC of 0.30 but the smallest RB (5.5%) compared with Gauge, followed by TPHiPr and APHRODITE with RB of 10.3% and −10.3%, respectively. ERA5-land significantly overestimated precipitation, showing an average error of 47.0% (Figure 2b). The lowest RMSE was also observed in TPHiPr, and the RMSE of other GPDs is around 15 mm d−1 (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Daily scale Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (CC, (a)), Relative Bias (RB, (b)), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE, (c)) between GPDs and ground observation data in Nepal from 2001 to 2015. The metrics were calculated per station within the time period and then used to derive the statistics (boxplots) displayed.

The performance metrics of GPDs exhibited a large variability by altitude (Figure 3, Table S2). Within the elevation range of 1.5 to 3 km, the correlation coefficient between GPDs and ground-based observations was relatively high (Figure 3a). Compared to regions below 3 km in elevation, high-altitude areas (>3 km) exhibited significantly greater relative bias (RB), but lower root mean square error (RMSE) (Figure 3b,c). A comparison among different products revealed that TPHiPr consistently demonstrated the highest correlation (0.50 to 0.71) and the lowest RMSE (1.7 mm·d−1 to 8.0 mm·d−1) across all altitude intervals. In areas below 3 km, TPHiPr’s RB ranged from 2.6% to 14.5%. Although RB was higher above 3 km, TPHiPr still outperformed other products (Table S2).

Figure 3.

The assessment statistics of GPDs vary with altitude. (a) Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (CC), (b) Relative Bias (RB) and (c) Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Stations were divided into intervals of 500 m by elevation, and the average was calculated for those stations within each altitude range. Daily precipitation from ground observations and GPDs for 152 stations from 2001 to 2015 were used in the comparison.

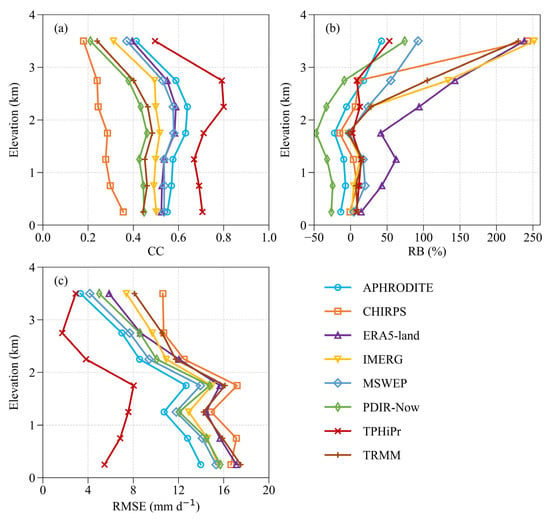

3.1.2. Precipitation Intensity

Notably, 72.2% of the observation records had negligible precipitation (0–0.1 mm daily rainfall) (Figure 4a). The proportions of light precipitation (0.1–10 mm), moderate precipitation (10.1–25 mm), heavy precipitation (25.1–50 mm), and torrential precipitation (≥50.1 mm) were 14.1%, 7.5%, 4.3%, and 2.0%, respectively. Only CHIRPS overestimated the proportion of negligible precipitation at 80.7% while underestimating the proportions of light precipitation at 5.5%. The other GPDs consistently exhibited varying degrees of underestimation for negligible precipitation days (ranging from 27.8% to 62.9%) and overestimation for light precipitation days (ranging from 23.1% to 54.6%). The observed proportion of moderate and higher intensity precipitation (≥10 mm) was only 13.7%. A similar distribution of this proportion was observed across the different GPDs, with the lowest value found in PDIR-Now (9.4%) and the highest in ERA5-Land (18.0%) (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

The proportion of each precipitation intensity level estimated by the observation data (Gauge) and eight different gridded precipitation datasets for Nepal. (a) negligible precipitation (0–0.1 mm) and light precipitation (0.1–10 mm), (b) moderate precipitation (10.1–25 mm), heavy precipitation (25.1–50 mm), and torrential precipitation (≥50.1 mm).

The proportion of different precipitation intensities varied with altitude (Figure S2). In regions below 2.5 km, the proportion of negligible precipitation decreased with increasing elevation (Figure S2a), while the proportions of light and moderate precipitation increased (Figure S2b,c). In contrast, the proportion of heavy and torrential precipitation peaked within the 1.5–2 km elevation range and declined above 2 km (Figure S2d,e).

The accuracy of GPDs in capturing different precipitation intensities was evaluated using four metrics (Table S3). Notably, TPHiPr demonstrated the highest Probability of Detection (POD = 0.78) and Critical Success Index (CSI = 0.39) across Nepal, along with the lowest False Alarm Rate (FAR = 0.57). APHRODITE, ERA5-land, and MSWEP exhibited relatively high POD, but their high FAR led to statistically significant overestimation of precipitation. Additionally, CHIRPS showed the closest frequency of precipitation capture to actual observations, and it was also the only product with a Frequency Bias Index (FBI = 0.97) value less than 1, indicating a higher likelihood of missed events, which resulted in underestimation of precipitation. Among different regions, all GPDs performed best in the central Nepal, followed by the eastern region, and lastly the western region.

In summary, TPHiPr exhibited the highest consistency with ground data at different spatiotemporal scales and rainfall intensities. Therefore, this dataset was used for further study on the spatiotemporal distribution patterns of precipitation and associated R-factor in Nepal from 1979 to 2020.

3.2. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Precipitation Based on TPHiPr

3.2.1. Seasonal and Annual Precipitation

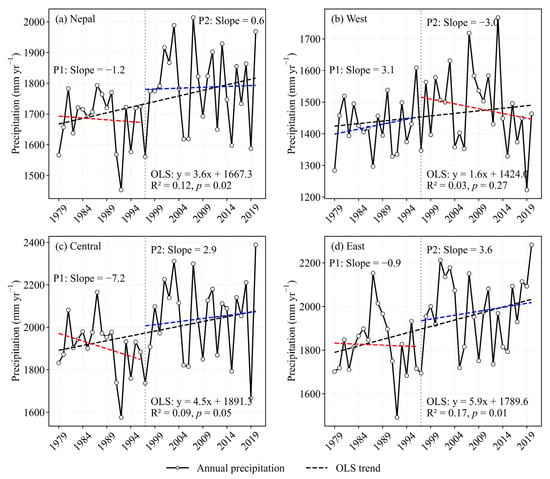

Precipitation in Nepal was highly seasonal (Table 3). The average annual precipitation in Nepal was about 1742 mm, with the majority (~80%) occurring during the monsoon season, especially in western Nepal. Over the past four decades, Nepal exhibited a significant increasing trend in annual precipitation, with a rate of 3.6 mm yr−1, primarily driven by monsoon rainfall, especially in the eastern Nepal (Figure 5a and Figure S3a, Table 3). The Sequential Mann-Kendall test indicated that 1996 is a statistically significant turning point, with annual precipitation shifting from a decreasing to an increasing trend. The central region had the highest annual precipitation, followed by the eastern region, and their trends were consistent with the trend across Nepal. The increase in the eastern region was particularly high, reaching 5.9 mm yr−1 (Figure 5c,d). In contrast, the relatively drier western region showed a slight shift from an increasing to a decreasing trend (Figure 5b). More noteworthy was that precipitation in the western region during the non-monsoon period (i.e., the dry season) also showed a decreasing trend (Table 3, Figure S3b). In summary, over the past four decades, wetter areas of Nepal have become significantly wetter, while drier areas have gradually become drier, especially during the dry season.

Table 3.

Annual values, seasonal distribution, and interannual variation trends of precipitation in different regions of Nepal from 1979 to 2020.

Figure 5.

Interannual variation of precipitation in Nepal from 1979 to 2020 based on TPHiPr. (a) for the whole Nepal, and (b–d) for the western, central, and eastern regions, respectively. The year 1996 is marked as a change point as shown by a vertical dashed line. y represents the trend of the entire study period (black dotted line), and Slope (mm yr−1) represents the ordinary least squares (OLS) trend of precipitation during the period before and after 1996 (P1: 1979–1996; P2: 1997–2020), respectively. The red and blue dotted lines indicate that precipitation has a decreasing and increasing trend at different stages, respectively. The regression equation is for the entire study period.

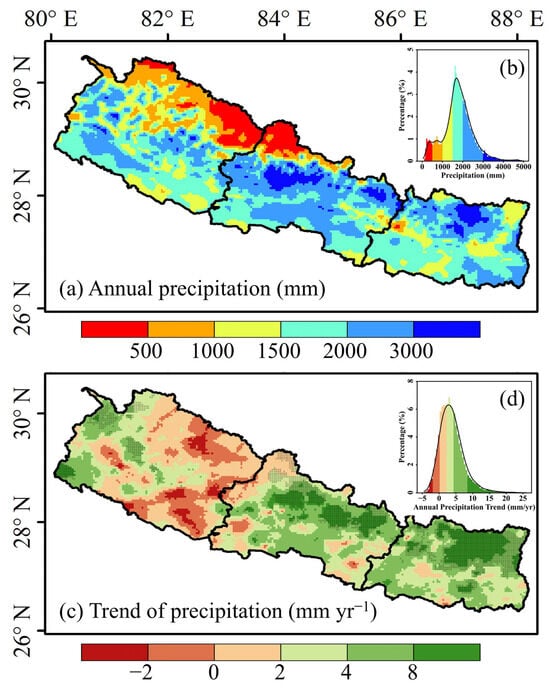

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution and Trend of Annual Precipitation

The high-altitude regions of Central and Eastern Nepal had high annual precipitation (>3000 mm). In contrast, high-altitude areas in the Western region had low annual precipitation (<500 mm). Annual precipitation was mainly concentrated between 1500–2000 mm. (Figure 6a,b). Areas with decreasing precipitation were predominantly found in the western region, while central and eastern regions showed an increasing trend in precipitation, particularly in the northern high-altitude areas. About 6% of the whole Nepal had an annual precipitation increase rate of 2–4 mm yr−1. (Figure 6c,d).

Figure 6.

Spatial pattern of annual precipitation in Nepal (1979–2020). (a) spatial distribution, (b) precipitation frequency distribution, (c) interannual trend of annual precipitation, and (d) interannual precipitation trend frequency distribution. The black lines in (b,d) are Gaussian smooth curves explain the annual precipitation and its trend in different ranges as a percentage of the area of Nepal. The cross areas in (c) indicate significant trend in annual precipitation (p < 0.05).

Precipitation showed a significant correlation with elevation (Figure S4a–d). In central and western Nepal, the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (CC) were −0.43 and −0.02, respectively, indicating that annual precipitation tends to decrease with increasing altitude. In contrast, the eastern region exhibited a positive correlation (CC = 0.21), which is closely linked to the observed high-precipitation zones at higher elevations in eastern Nepal (Figure 6c). Specifically, the negative correlation was most pronounced in western Nepal, persisting across all elevations below 6 km (Figure S4b). In the central region, the negative correlation only appeared in areas with the altitude between 3 km and 6 km, while the positive correlation was found in areas with the altitude below 3 km and above 6 km (Figure S4c). In the eastern region, a positive correlation existed below 4 km, shifting to negative above 4 km (Figure S4d).

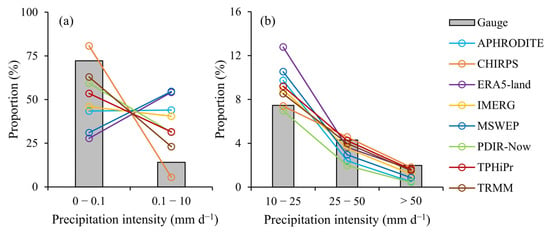

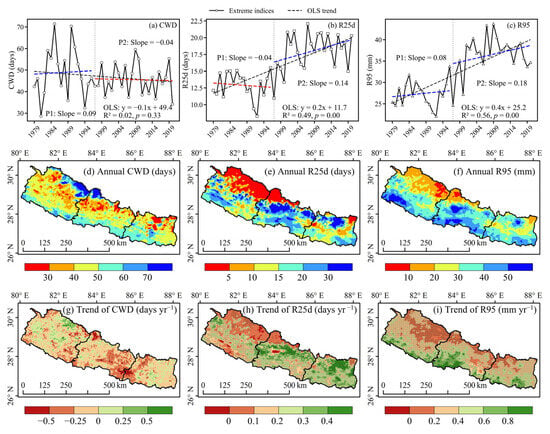

3.2.3. Variations of Extreme Precipitation

Extreme precipitation patterns such as event lengths, frequency, and intensity, were examined using metrics of CWD, R25d, and R95 (Figure 7). Over the past four decades, the maximum number of consecutive wet days in a year reached 47 days, the number of days with daily precipitation exceeding 25 mm was 16 days in a year, the 95th percentile of precipitation was 32.6 mm. Interannually, both the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events showed a significant increase, with R25d increasing at a rate of 0.2 days yr−1, and R95 increasing at a rate of 0.4 mm yr−1 (Figure 7b,c). However, the lengths of precipitation events showed an insignificant downward trend, indicating that a sporadic nature of such events increased (Figure 7a). Taking 1996 as the turning point, CWD shifted from an increasing trend to a decreasing trend, R25d changed from a decreasing trend to an increasing trend, and R95 consistently maintained an increasing trend. This suggests that rainfall persistence in Nepal has weakened, while both the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events have increased.

Figure 7.

Interannual variations and spatial patterns of extreme precipitation in Nepal (1979–2020). (a–c) interannual variations, (d–f) spatial distribution of multi-year mean, (g–i) spatial distribution of interannual variability. The cross areas in (g–i) indicate significant trend (p < 0.05). CWD is the maximum consecutive wet days, R25d is the number of days with daily rainfall ≥ 25 mm, and R95 is the 95th percentile of precipitation. The year 1996 is marked as a change point as shown by a vertical dashed line. y represents the trend of the entire study period (black dotted line), and Slope (mm yr−1) represent the ordinary least squares (OLS) trend of precipitation during the period before and after 1996 (P1: 1979–1996; P2: 1997–2020), respectively. The red and blue dotted lines indicate that precipitation has a decreasing and increasing trend at different stages, respectively. The regression equation is for the entire study period.

Among the three regions, western Nepal had the longest consecutive wet days (CWD = 49 days), but the lowest frequency (R25d = 12 days) and intensity (R95 = 29.2 mm) of extreme precipitation. The eastern region showed the shortest duration of extreme precipitation events (CWD = 47 days), while the central region exhibited the highest intensity and frequency of extreme events (R25d = 20 days, R95 = 36.5 mm) (Figure 7d–f). The interannual variations in extreme-event characteristics were broadly similar across regions, with CWD showing a decreasing trend, whereas R25d and R95 displayed significant upward trends (Figure 7g–i). Around 1996, CWD in the central and eastern regions followed the overall pattern, shifting from an increasing to a decreasing trend, while the western region showed the opposite change (Figure S5a–d). For R25d, the central and eastern regions aligned with the overall trend, whereas both the western and eastern regions exhibited a sustained increasing tendency (Figure S5e–h). Across all regions, R95 consistently showed an increasing trend before and after 1996 (Figure S5i–l).

Extreme precipitation also exhibited a significant linear correlation with altitude, though the correlation varied across different elevation ranges in different regions (Figure S4c–p). The altitudinal trends of extreme indices in the western and central regions resembled the overall pattern, whereas the eastern region displayed distinct differences. Generally, the frequency, intensity, and duration of extreme precipitation events showed negative correlations with elevation (CC < 0). In the western and central regions, both R25d and R95 tended to decrease with increasing altitude below 6 km, while above 6 km, R25d and R95 increased, and CWD decreased, indicating that short-duration heavy precipitation events are more likely to occur at higher elevations. The altitudinal characteristics in the eastern region differed from those in other areas, with the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events remaining relatively stable across elevations.

3.3. Spatiotemporal Patterns of R-Factor Based on TPHiPr

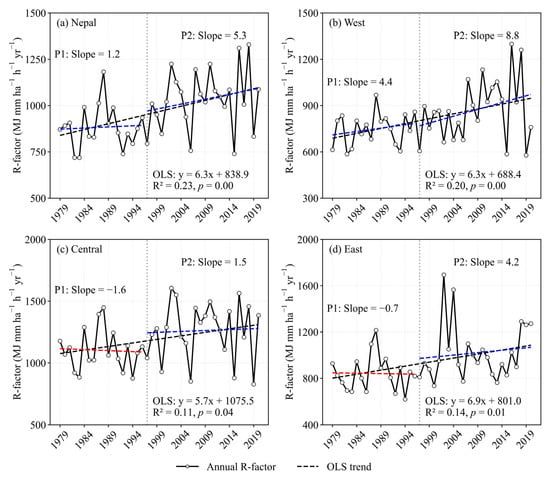

3.3.1. Seasonal and Annual R-Factor

From 1979 to 2020, the R-factor across Nepal showed a significant increasing trend (Figure 8a). The multi-year mean of the annual R-factor was 968 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1, with an increasing rate of 6.3 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−2. The R-factor in the monsoon period (June to September) dominated annual R-factor (Table S4), reflecting the effects of monsoon precipitation that accounts for about 78% of the annual total precipitation. During the monsoon period, the multi-year mean of the R-factor was 942 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1, accounting for about 97.3% of the annual R-factor, and increased at a rate of 6.0 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−2, contributing 95.8% to the annual R-factor change rate.

Figure 8.

Interannual variation of the annual R-factor across Nepal from 1979 to 2020: (a) Whole Nepal, (b) Western Nepal, (c) Central Nepal, (d) Eastern Nepal. The year 1996 is marked as a change point as shown by a vertical dashed line. y represents the trend of the entire study period (black dotted line), and Slope (mm yr−1) represent the ordinary least squares (OLS) trend of precipitation during the period before and after 1996 (P1: 1979–1996; P2: 1997–2020), respectively. The red and blue dotted lines indicate that precipitation has a decreasing and increasing trend at different stages, respectively. The regression equation is for the entire study period.

The central region recorded the highest R-factor in the country, with an average annual value of 1193 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1, followed by the eastern region (Table S5). However, the R-factor in the eastern region experienced the largest increase over the past four decades, at a rate of 6.9 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−2 (Figure 8d). Before and after 1996, the R-factor in western Nepal showed no distinct turning point, maintaining an overall increasing trend that aligns with the overall trend of Nepal (Figure 8b). In contrast, the R-factor in the central and eastern regions shifted from a decreasing to an increasing trend (Figure 8c,d). This indicates a significantly rising trend of rainfall erosivity across the entire Nepal.

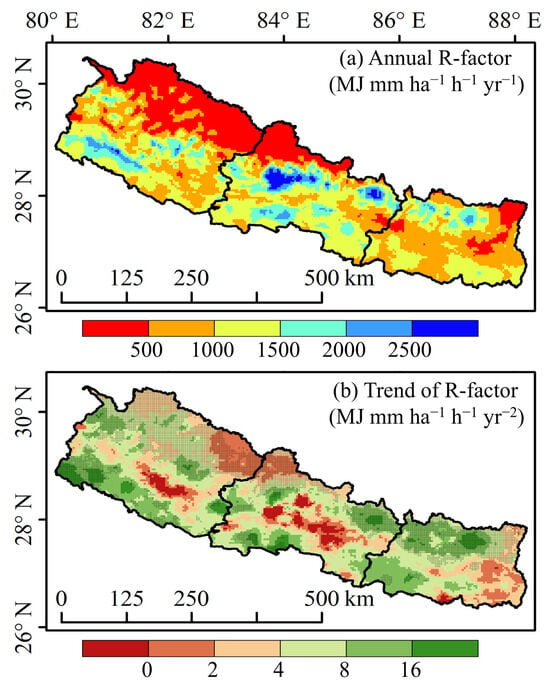

3.3.2. Spatial Distribution and Trend of R-Factor

Low values (<500 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1) were found in the northwestern high-altitude mountainous areas with low precipitation, while high values (>2000 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1) appeared in the central region with abundant precipitation. Additionally, relatively high R-factor values were also present in parts of the southwestern and northeastern regions. The spatial distribution pattern of the R-factor was similar to those of precipitation (Figure 6a), R25d (Figure 7e), and R95 (Figure 7f).

Notably, the trend of the R-factor change was not fully synchronized with precipitation. Overall, the R-factor generally showed an increasing trend, especially in the high-altitude areas of northern Nepal (Figure 9b). Meanwhile, a relatively significant and rapid increasing trend was also observed in the low-altitude areas of the southwest Nepal. However, precipitation exhibited a decreasing trend in this specific region (Figure 6c), whereas both R25d and R95 in the same region show a significant increasing trend (Figure 7h,i), highlighting the high sensitivity of the R-factor to extreme precipitation intensity and frequency.

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of annual R-factor and its interannual trend (1979–2020): (a) multi-year mean of the annual R-factor, (b) interannual trend of the annual R-factor. The cross-hatched areas indicate a significant trend in the annual R-factor (p < 0.05).

3.3.3. R-Factor Variation with Altitude

The R-factor decreased with the increasing altitude (Table 4). In areas below 3 km in altitude, the R-factor exceeded 1000 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1, while in areas with the altitude above 5 km, it was only about half of that value. R-factor showed a significant interannual increasing trend in all altitude ranges (p < 0.05). The maximum increasing rate of 7.4 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−2 was observed in areas below 1 km in elevation, followed by the medium-altitude areas of 2–3 km. In contrast, areas above 5 km exhibited the lowest increasing rate, at 4.0 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−2.

Table 4.

Multi-year mean (1979–2020) and changing rate of annual R-factor across different altitude ranges in Nepal.

Regarding regional differences (Table S5, Figure S4q–t), the variation of the R-factor with altitude in the western region was similar to the overall pattern in Nepal: the R-factor decreased with increasing altitude below 6 km but increased above 6 km (Figure S4r). The altitudinal distribution characteristics of the R-factor in this region were consistent with those of R25d and R95 (Figure S4j,n). In the central region, the R-factor decreased with altitude in the 3–6 km elevation range but showed an increasing trend in the 0–3 km and above 6 km elevation ranges (Figure S4s). Its distribution pattern aligned well with annual precipitation and R25d (Figure S4c,k). In the eastern region, the R-factor generally exhibited a gradually decreasing trend with increasing altitude (Figure S4t), and its distribution characteristics were similar to those of annual precipitation, R25d, and R95 (Figure S4d,l,p). The increase in the R-factor was more pronounced within the 2–4 km altitude range (Table S5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Data Limitations and Their Impact on Rainfall Erosivity Assessment

The significant discrepancies observed among the eight gridded precipitation datasets (GPDs) evaluated in this study highlight the challenges in accurately characterizing precipitation patterns over complex terrains such as the Himalayas. Among them, the TPHiPr dataset, which integrates observations from over 9000 stations, demonstrated the best performance in capturing spatiotemporal precipitation patterns, particularly extreme events. The discrepancies between the GPDs and ground-based observations can be attributed to several factors: the terrain shielding effect in high-altitude Himalayan regions reduces the accuracy of radar and satellite observations [80,81]; the data fusion algorithms of different products (e.g., smoothing of extreme events in MSWEP) and differences in spatial resolution (ranging from 0.25° to 0.03°, Figure S8) also lead to systematic overestimation or underestimation [82,83].

The selection of GPDs should be based on specific application needs, as each dataset has its own strengths in capturing different aspects of precipitation dynamics. All eight datasets are capable of capturing the monthly variations and seasonal distribution of precipitation in Nepal. However, they exhibit varying degrees of overestimation or underestimation compared to ground-based observations (Figure S6), particularly during the dry season (e.g., winter). Meanwhile, different datasets capture different characteristics of the interannual variability of precipitation. APHRODITE, IMERG, TPHiPr, and TRMM show trends in annual precipitation, frequency, and intensity of extreme precipitation events that are similar to those of ground observations (Figure S7). For continuous precipitation events, only TPHiPr is relatively consistent with ground observations, though it exhibits a slight overestimation. The substantial uncertainties in GPDs emphasize the importance of ground-based observations for validation and calibration, particularly in high-altitude areas where data are scarce.

Although TPHiPr shows the best performance in capturing Nepal’s precipitation climatology, especially at high altitudes, all datasets contain biases that propagate into the estimation of the R-factor. For example, PDIR-Now exhibits a relative bias of −28.6% compared to ground observations and underestimates heavy precipitation (≥25 mm) by 4.4% (Figure 4), which may lead to an underestimation of erosion risk. Conversely, the overestimation of precipitation by ERA5-Land (RB = 47.0%) could result in an inflated estimate of erosion in central Nepal. This variability underscores the necessity of dataset-specific uncertainty quantification when applying GPDs to erosion modeling.

4.2. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Variations in Precipitation and Their Physical Mechanisms

4.2.1. Seasonal and Annual Precipitation

The TPHiPr dataset clearly shows an east–west gradient in annual precipitation, consistent with the findings of ref. [53] (p. 26). However, the temporal trend identified in our study differs from that reported in ref. [53] (p. 26), which suggested that eastern Nepal became drier and western Nepal became wetter after 2003. Their conclusion was derived using extreme precipitation indices calculated from local observation data. Changes in the upper-level jet stream and the associated lower-level monsoon trough have been identified as critical factors influencing extreme precipitation trends after 2003 [53]. Our analysis indicates that 1996 marks a key turning point in precipitation trends across Nepal: annual precipitation nationwide shifted from a decreasing to an increasing trend, but regional responses diverged. The humid central and eastern regions experienced an acceleration in precipitation increase, while the relatively drier western region transitioned to a slight declining trend, with precipitation reduction during the dry season. The shift in precipitation trends around 1996 is closely associated with documented changes in large-scale climate patterns and topographic effects. The precipitation trends in eastern and central Nepal align with the enhancement of moisture transport from the Bay of Bengal since the mid-1990s, while the trends in western Nepal reflect differentiated changes in atmospheric circulation [84,85].

The differential responses across elevation intervals further highlight atmosphere–terrain interactions. In eastern Nepal, precipitation shows a positive correlation with elevation (CC = 0.21), whereas negative correlations are observed in the western and central regions (CC = −0.43 and −0.02, respectively; Figure S4). This suggests that the dominant moisture sources and transport pathways vary across the country. In the east, persistent moisture supply enables continued orographic enhancement of precipitation even at higher elevations. In the west, limited moisture supply restricts precipitation generation primarily to lower elevations [86].

4.2.2. Extreme Precipitation

Based on the TPHiPr dataset, we observed an increase in the intensity of extreme precipitation—R25d increasing by 0.2 days yr−1 and R95 increasing by 0.4 mm yr−1 (p < 0.01), while the maximum consecutive wet days decreased (Figure 7). This represents a key shift toward more intermittent and higher-intensity rainfall, which is consistent with previous findings [49]. We further highlight that this change exhibits distinct spatial heterogeneity: robust growth in the central and eastern regions, while the increase is relatively weaker in the western region. This disparity pattern likely stems from the interaction between topography and monsoon moisture transport [53,87].

The elevation dependence of extreme precipitation changes reveals important nuances. Although extreme precipitation frequency and intensity generally decrease with increasing elevation (CC < 0), this relationship reverses above 6 km elevation in western and central Nepal, where both R25d and R95 increase with elevation (Figure S4). This intensification at high elevations, combined with a shortening of precipitation duration, indicates that storm characteristics are changing in high-altitude areas. Specifically, more frequent, short-duration, high-intensity events are increasing. Notably, there is a decoupling between total precipitation and extreme precipitation trends in western Nepal. Despite a declining trend in annual precipitation, extreme precipitation indices show increases, indicating a redistribution of precipitation toward fewer but more intense events. Due to the nonlinear relationship between rainfall intensity and erosive energy, this shift is expected to have a disproportionately large impact on erosion.

4.3. Rising R-Factor and a Large Variability Across Nepal

Our study shows that estimating the R-factor using only annual precipitation time series, without considering intra-annual variability and extreme rainfall events, may lead to bias in a region such as Nepal where monsoon rainfall is prominent and rainfall intensity varies spatially. However, because there are no long-term observation stations in areas above 4 km elevation in Nepal, R-factor estimated based on station data may be inaccurate for high-mountain areas [3]. This study employed a common model to estimate the R-factor at the national level. We acknowledge that there are many other models for estimating the R-factor with different data requirements, and direct comparisons among published products are challenging and problematic.

Previous studies have shown similar spatial distributions of the R-factor, but we found large discrepancies in the numerical values. For example, ref. [45] (p. 25) used an annual precipitation map to show that the R-factor values ranged from 150 to 2000 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1, which is similar to our results. Due to the diversity of estimation methods and data sources, R-factor values reported in other studies at the basin or national scale range from several hundred to tens of thousands [3,46,88,89,90]. Ref. [3] (p. 24) produced the first national R-factor map but acknowledged significant uncertainties above 4000 m due to sparse station coverage.

This study is the first to independently analyze the long-term dynamics of the R-factor across Nepal based on long-term gridded daily precipitation data. The results indicate that, under the combined influence of an overall increase in total precipitation and extreme precipitation events, Nepal’s R-factor increased significantly (6.3 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−2), especially during the monsoon period. One of the most critical findings is that in western Nepal, despite a declining trend in annual precipitation, the R-factor increased sharply. This highlights the high sensitivity of the R-factor to precipitation intensity and frequency rather than total amount. Analysis reveals that extreme precipitation indices (R95, R25d) in this region increased significantly during the same period (Figure 7h,i). This indicates that even as total rainfall decreases, the precipitation structure is shifting toward “fewer but more intense” events. A few high-intensity events can contribute far more to annual erosivity than numerous light-rain events. Ref. [90] (p. 27) emphasized that the R-factor depends not only on total precipitation but also on the pattern and intensity of precipitation, which also affects rainfall erosivity. This finding carries an important warning: in the context of climate change, focusing solely on precipitation amount trends may mislead the assessment of soil erosion risk. A region that is becoming “drier” in terms of annual precipitation may actually face aggravated soil-loss threats if accompanied by an increase in heavy rainfall events. This also highlights the necessity of incorporating extreme-precipitation dynamics into erosion models, because traditional models based solely on monthly or annual total precipitation may underestimate erosion risk in high-elevation areas.

4.4. Toward Better Future Management of Soil and Water Resources

As a nation of approximately 30 million people heavily reliant on climate-sensitive subsistence agriculture and natural resource-based livelihoods [52], the integrity of water and soil resources is fundamental to Nepal’s food security, economic stability, and community resilience. The intensifying monsoon patterns, shifting precipitation regimes, and escalating rainfall erosivity documented in this study are not merely climatic statistics, but tangible risk drivers affecting millions of people. Therefore, translating this high-resolution climatic understanding into actionable management strategies is crucial for Nepal’s sustainable development.

Our study demonstrates that the high uncertainty of precipitation in high-elevation areas hinders accurate estimation of the R-factor. The scarcity of long-term meteorological data over complex terrain, especially at high elevations, severely constrains observation-based national-scale hydrological and soil-erosion risk assessments. Remote mountainous regions indeed generally face a severe shortage of hydrological and meteorological data. Part of the reason is that government agencies often assign lower priority to high-elevation sites due to cost and logistical challenges [91]. In Nepal, 80% of the hydrological stations installed by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) are located at low altitudes (<500 m). The lack of monitoring of precipitation and river flows in high-elevation watersheds can lead to serious prediction errors of major floods during the monsoon season. For example, due to strong interannual variations in river flow and sediment, some large high-elevation watersheds, which include rain-on-snow runoff mechanisms, are sources of flood hazards and are rarely used by mountain communities for water supply and irrigation. Instead, local residents rely on smaller streams for irrigation [92]. Small settlements are typically situated at high elevations beyond the reach of any national-scale water-resources management and planning interventions. With very limited hydro-meteorological information, mountain communities heavily depend on their indigenous knowledge to manage the available water resources, which are increasingly vulnerable to climate change [93]. Therefore, our study also recommends that precipitation monitoring efforts should prioritize high-elevation areas where GPDs exhibit greater uncertainty. This suggestion aligns with ref. [94] (p. 27), which calls for more weather stations in high-altitude regions to monitor potential evaporation for water-balance calculations.

Our analysis reveals the most pronounced increases in the R-factor within the 2–4 km elevation range (Table 4, Figure 9), which coincides with the densely populated Middle Hills—a region critical for staple crop production (e.g., rice, maize, wheat). This escalating erosivity directly threatens the region’s thin topsoil layer, the foundation of its agricultural productivity. Accelerated soil loss can lead to declining crop yields, increased siltation of vital irrigation channels, and reduced water retention capacity of soils [2]. For communities predominantly engaged in subsistence farming, these impacts compound existing vulnerabilities, potentially undermining household food security and income. This calls for adjustments in agricultural practices, promoting soil and water conservation measures such as contour farming, terracing, and cover cropping, and integrating erosion-risk information into agricultural extension systems.

The diverging precipitation trends portend contrasting sets of socio-ecological challenges (Figure 5, Table 3). In western Nepal, the observed decline in dry-season precipitation exacerbates the region’s inherent aridity. This trend is likely linked to the depletion of springs and baseflows, heightening drought stress on rain-fed agriculture and forests, and intensifying competition for scarce water resources. Such conditions will threaten the water security of mountain communities, potentially triggering livelihood stresses and migration pressures [4,6]. Conversely, central and eastern Nepal are experiencing not only increased total rainfall but, more critically, a significant rise in the intensity and frequency of extreme precipitation events (Figure 7). This shift greatly elevates the risks of flash floods, landslides, and associated infrastructure damage (roads, bridges, settlements). These hazards can cause immediate loss of life and property, disrupt transportation and market access, isolate communities, and lead to substantial economic losses. Moreover, the increased sediment load from heightened erosion can silt up reservoirs, reducing the lifespan and efficiency of critical hydropower infrastructure [3,18,19].

Overall, the information derived from this study can aid in designing nature-based solutions to address future changes in precipitation and erosion—two critical hydrological variables that govern watershed processes and ecosystem resilience. In low-elevation areas (<1.5 km), although the R-factor is high, communities possess relatively stronger adaptive capacity. Emphasis should be placed on floodplain management, irrigation system maintenance, promotion of erosion-resistant crop varieties, and the development of community-based flood-warning systems. Mid-elevation areas (1.5–4 km) represent a critical zone characterized by dense populations, active agriculture, and the most pronounced increasing trend in the R-factor. Policies should prioritize strengthening soil and water conservation engineering in this region, imposing strict limits on steep-slope cultivation in land-use planning, and advancing community-based integrated watershed management. In high-elevation areas (>4 km), observational data are scarcest and uncertainties greatest, yet the increasing trend of the R-factor is evident. These areas serve as important water-source regions for downstream catchments. The primary recommendation is to strategically establish additional hydro-meteorological monitoring stations at feasible sites. Future research should prioritize: (1) developing elevation-sensitive erosion models that incorporate the nonlinear relationships between precipitation characteristics and erosivity; (2) generating high-resolution projections of future R-factor changes using dynamically downscaled climate models; and (3) conducting integrated erosion-risk assessments that account for land-use change scenarios and adaptive management options. Such work will support Nepal in implementing targeted, science-based soil-conservation strategies under changing climatic conditions, while enabling comprehensive cost–benefit evaluations of different soil-conservation measures and their impacts on food security and livelihood improvement, thereby providing more direct decision-support for sustainable resource management.

5. Conclusions

Our study represents the first comprehensive analysis of long-term precipitation (including extreme events) and rainfall erosivity (R-factor) across Nepal using multiple precipitation data sources. The results indicate that global gridded precipitation datasets exhibit significant discrepancies compared to local ground observation data, and ground-based observational data for high-altitude regions are particularly lacking.

Overall, since 1996, annual precipitation in eastern and central Nepal has increased significantly, while it has decreased to some extent in the western region. Over time, extreme precipitation events have become more frequent and intense, although the duration of precipitation events has shortened. The R-factor values across Nepal have increased significantly and exhibit altitude dependence, and this increase is not fully synchronized with trends in total precipitation. Even in the western region, where annual precipitation is decreasing, erosion risk is on the rise, highlighting the high sensitivity of the R-factor to changes in rainfall intensity and frequency rather than total amount.

Our study suggests that hydro-climatic extremes are intensifying and diverging across Nepal. Erosion and flooding threats driven by monsoon rainfall are worsening in the central and eastern regions, while water scarcity during the dry season is becoming increasingly severe in the west. The findings emphasize that soil erosion risk assessment cannot rely solely on trends in total precipitation but must also account for changes in rainfall intensity and frequency. This necessitates the development of differentiated watershed management strategies tailored to different regions and elevations. Prioritizing soil and water conservation measures in vulnerable mid-elevation agricultural zones, enhancing hydro-meteorological monitoring in data-scarce high-altitude areas, and integrating extreme precipitation dynamics into erosion models are crucial for building resilience in the context of climate change.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rs18010069/s1, Text S1: Detailed description of all precipitation datasets used in this study; Text S2: Evaluation methods of gridded precipitation datasets; Table S1: Precipitation intensity classification scheme; Table S2: Mean values of statistical indicators across different altitude intervals; Table S3: Detection indicators of GPDs in different regions; Table S4: Multi-year mean and changing rate of seasonal and annual R-factor; Table S5: Multi-year mean and changing rate of annual R-factor in different regions; Figure S1: Spatial distribution of statistical indices of GPDs at the daily scale from 2001 to 2015; Figure S2: The variation of precipitation intensity levels from ground observations and all GPDs with altitude; Figure S3: Interannual changes of seasonal precipitation and extreme precipitation indices at different regional scales based on TPHiPr from 1979 to 2020; Figure S4: Variations in annual precipitation, extreme precipitation indices, and the R-factor with altitude across different regions of Nepal (1979–2020); Figure S5: Interannual variations in extreme precipitation characteristics across different regions of Nepal (1979–2020); Figure S6: Results of in-situ observation data and GPDs on monthly variations (a) and seasonal distribution (b) of precipitation in Nepal from 2001 to 2015; Figure S7: Detection of interannual changes in annual precipitation and extreme precipitation indices in Nepal from 2001 to 2015 by different datasets; Figure S8: The impact of GPDs’ spatial resolution on data consistency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S. and L.H.; methodology, R.T.; software, R.T.; formal analysis, R.T.; investigation, R.T.; resources, R.P.A.; data curation, R.T. and K.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T.; writing—review and editing, R.T., R.P.A., K.J., L.W., N.L., K.R.T., C.S., D.M.A., G.S. and L.H.; visualization, R.T.; supervision, G.S. and L.H.; project administration, L.H.; funding acquisition, L.H. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China-United Nations Environment Programme (NSFC-UNEP) International Joint Research Project (funding number: 42061144004; funder (principal investigator): Lu Hao, NUIST) and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) Project on Coupling Human and Nature Systems (funding number: ICER-2108238; funder (principal investigator): Conghe Song, UNC). Partial support is also from the Southern Research Station USDA Forest Service. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Data Availability Statement

Data sets used for this study were obtained from several published sources. Weather station data (https://www.dhm.gov.np/data-service/, accessed on 26 August 2024); APHRODITE (https://www.chikyu.ac.jp/precip/, accessed on 26 August 2024); CHIRPS (https://www.chc.ucsb.edu/, accessed on 26 August 2024); ERA5-land (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/, accessed on 26 August 2024); IMERG (https://gpm.nasa.gov/data/imerg/, accessed on 26 August 2024); MSWEP (https://www.gloh2o.org/mswep/, accessed on 26 August 2024); PDIR-Now (https://chrsdata.eng.uci.edu/, accessed on 26 August 2024); TPHiPr (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/en/, accessed on 26 August 2024); TRMM (https://gpm.nasa.gov/missions/trmm/, accessed on 26 August 2024).

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chalise, D.; Kumar, L.; Kristiansen, P. Land degradation by soil erosion in Nepal: A review. Soil Syst. 2019, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; Tara, N.B.; Keshar, M.S.; Hiroshi, O. Soil erosion and sediment disaster in Nepal-A review. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 1998, 42, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talchabhadel, R.; Prajapati, R.; Aryal, A.; Maharjan, M. Assessment of rainfall erosivity (R-factor) during 1986-2015 across Nepal: A step towards soil loss estimation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatta, L.D.; van Oort, B.E.H.; Stork, N.E.; Baral, H. Ecosystem services and livelihoods in a changing climate: Understanding local adaptations in the Upper Koshi, Nepal. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2015, 11, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.M.A.; Biggs, E.M.; Dash, J.; Atkinson, P.M. Spatio-temporal trends in precipitation and their implications for water resources management in climate-sensitive Nepal. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 43, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Case Studies on Sustainable Livelihoods in Rural Areas of Nepal: Ecosystem Restoration and Conservation for Resilient Livelihoods in the Rupa Lake Watershed of Nepal; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting Rainfall Erosion Losses; Agriculture Handbook Number 537; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; pp. 285–291.

- Renard, K.G.; Laflen, J.M.; Foster, G.R.; McCool, D.K. The revised universal soil loss equation. In Soil Erosion Research Methods; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Yin, S.; He, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, H.; Klik, A. Projections of rainfall erosivity in climate change scenarios for mainland China. Catena 2023, 232, 107391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Nearing, M.A.; Borrelli, P.; Xue, X. Rainfall erosivity: An overview of methodologies and applications. Vadose Zone J. 2017, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, C.; Sun, G.; McNulty, S.; Zhang, Y. Potential impacts of climate change on soil erosion vulnerability across the conterminous United States. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2014, 69, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Misra, D.; Amatya, D.M.; Grace, J.M.; Thompson, A. Advances in modeling soil erosion risk. In Ch 9: Understanding and Preventing Soil Erosion; Seeger, M., Ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2024; pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, D.; Attada, R.; Shukla, K.K.; Chakraborty, R.; Kunchala, R.K. Monsoon precipitation characteristics and extreme precipitation events over Northwest India using Indian high resolution regional reanalysis. Atmos. Res. 2022, 267, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Vittal, H.; Sharma, T.; Karmakar, S.; Kasiviswanathan, K.S.; Dhanesh, Y.; Sudheer, K.P.; Sunthe, S.S. Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall: Implications of Contrasting Trends in the Spatial Variability of Means and Extremes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Sabin, T.P.; Madhura, R.K.; Vellore, R.K.; Mujumdar, M.; Sanjay, J.; Rajeevan, M. Non-monsoonal precipitation response over the Western Himalayas to climate change. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 52, 4091–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlinger, P.; Sorteberg, A. A comprehensive view on trends in extreme precipitation in Nepal and their spatial distribution. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 38, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, M.; Yoneda, M.; Talchabhadel, R.; Thapa, B.R.; Aryal, A. Use of indices on daily timescales to study changes in extreme precipitation across Nepal over 40 years (1976–2015). Earth Space Sci. 2023, 10, e2020EA001509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Bai, C.; Zhu, Y.; Shao, M.A.; Han, X.; Qiao, J. Future soil erosion risk in China: Differences in Erosion driven by general and extreme precipitation under climate change. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2024EF005390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Panda, S.; Amatya, D.M.; Lew, R.; Dobre, M.; Campbell, J.L.; Johnson, S.L.; Elder, K.; Jalowska, A.M.; Grace, J.M. Hydro-geomorphological assessment of culvert vulnerability to flood induced erosion and siltation using ensemble modeling approach. J. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 183, 106243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. Using High-Density Rain Gauges to Validate the Accuracy of Satellite Precipitation Products over Complex Terrains. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, L.; Wei, J.; Xie, X. Spatiotemporal variability of alpine precipitable water over arid northwestern China. Hydrol. Process. 2020, 34, 3524–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Du, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Evaluating extreme precipitation estimations based on the GPM IMERG products over the Yangtze River Basin, China. Geomatics. Nat. Hazards Risk 2020, 11, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Ma, Z.; He, K.; Han, X.; Ji, Q.; He, Y. Evaluations on gridded precipitation products spanning more than half a century over the Tibetan Plateau and its surroundings. J. Hydrol. 2020, 582, 124455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Hodnebrog, Ø.; Daloz, A.S.; Sen, S.; Badiger, S.; Krishnaswamy, J. Measuring precipitation in Eastern Himalaya: Ground validation of eleven satellite, model and gauge interpolated gridded products. J. Hydrol. 2021, 599, 126252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Miao, C.; Duan, Q.; Ashouri, H.; Sorooshian, S.; Hsu, K. A Review of global precipitation data sets: Data sources, estimation, and intercomparisons. Rev. Geophys. 2018, 56, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Su, F. Precipitation Correction and Reconstruction for Streamflow Simulation Based on 262 Rain Gauges in the Upper Brahmaputra of Southern Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L. Effects of climate change on runoff in a representative Himalayan basin assessed through optimal integration of multi-source precipitation data. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Liu, J.; Tuo, Y.; Chiogna, G.; Disse, M. Evaluation of eight high spatial resolution gridded precipitation products in Adige Basin (Italy) at multiple temporal and spatial scales. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 1536–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Amatya, D.M.; Jalowska, A.M.; Campbell, J.L.; Johnson, S.L.; Elder, K.; Panda, S.; Grace, J.M.; Kikoyo, D. Comparison of on-site versus NOAA’s extreme precipitation intensity-duration-frequency estimates for six forest headwater catchments across the continental United States. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 4051–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchiola, D.; Brunetti, L.; Soncini, A.; Polinelli, F.; Gianinetto, M. Impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food security in the Himalayas: A case study in Nepal. Agric. Syst. 2019, 171, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijnzeel, L.; Sun, G.; Zhang, J.; Tiwari, K.; Hao, L. Forests, Water, and Livelihoods in the Lesser Himalaya. Eos 2024, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Haugen, J.E.; Xu, C. Precipitation pattern in the Western Himalayas revealed by four datasets. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 5097–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Yang, K.; Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Lazhu; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y. Ground-Based Observations Reveal Unique Valley Precipitation Patterns in the Central Himalaya. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2019JD031502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamal, K.; Khadka, N.; Rai, S.; Joshi, B.B.; Dotel, J.; Khadka, L.; Bag, N.; Ghimire, S.K.; Shrestha, D. Evaluation of the TRMM Product for Spatio-temporal Characteristics of Precipitation over Nepal (1998–2018). J. Inst. Sci. Technol. 2020, 25, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamal, K.; Sharma, S.; Khadka, N.; Baniya, B.; Ali, M.; Shrestha, M.S.; Xu, T.; Shrestha, D.; Dawadi, B. Evaluation of MERRA-2 Precipitation Products Using Gauge Observation in Nepal. Hydrology 2020, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Amarnath, G.; Ghosh, S.; Park, E.; Baghel, T.; Wang, J.; Pramanik, M.; Belbase, D. Assessing the Performance of the Satellite-Based Precipitation Products (SPP) in the Data-Sparse Himalayan Terrain. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, B.; Bao, Q.; Wu, G. Assessing Multi-Source Precipitation Estimates in Nepal: A Benchmark for Sub-Seasonal Model Assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2024JD040759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, K.; Li, X.; Niu, X.; Khadka, N. Evaluation of GPM-Era Satellite Precipitation Products on the Southern Slopes of the Central Himalayas Against Rain Gauge Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Khadka, N.; Hamal, K.; Shrestha, D.; Talchabhadel, R.; Chen, Y. How Accurately Can Satellite Products (TMPA and IMERG) Detect Precipitation Patterns, Extremities, and Drought Across the Nepalese Himalaya? Earth Space Sci. 2020, 7, e2020EA001315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.; Su, F.; Yang, D.; Hao, Z. Evaluation of satellite precipitation retrievals and their potential utilities in hydrologic modeling over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talchabhadel, R.; Shah, S.; Aryal, B. Evaluation of the Spatiotemporal Distribution of Precipitation Using 28 Precipitation Indices and 4 IMERG Datasets over Nepal. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Khadka, N.; Hamal, K.; Baniya, B.; Luintel, N.; Joshi, B.B. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Precipitation and Its Extremities in Seven Provinces of Nepal (2001–2016). Appl. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, D.; Sharma, S.; Hamal, K.; Jadoon, U.K.; Dawadi, B. Spatial Distribution of Extreme Precipitation Events and Its Trend in Nepal. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, J.K.; Yu, I.; Jeong, S. Estimation of soil erosion using RUSLE model and GIS techniques for conservation planning from Kulekhani Reservoir Catchment, Nepal. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2016, 16, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, P.; Thakuri, S.; Joshi, S.; Chauhan, R. Estimation of soil erosion in Nepal using a RUSLE modeling and geospatial tool. Geosciences 2019, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Matin, M.A.; Maharjan, S. Assessment of land cover change and its impact on changes in soil erosion risk in Nepal. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Murthy, M.S.R.; Wahid, S.M.; Matin, M.A. Estimation of soil erosion dynamics in the Koshi Basin using GIS and remote sensing to assess priority areas for conservation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talchabhadel, R.; Karki, R.; Thapa, B.R.; Maharjan, M.; Parajuli, B. Spatio-temporal variability of extreme precipitation in Nepal. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 4296–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, S.; Bookhagen, B. The spatial pattern of extreme precipitation from 40 years of gauge data in the central Himalaya. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2022, 37, 100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Subedi, R.; Jin, K.; Hao, L. Spatiotemporal variation of potential evapotranspiration and meteorological drought based on multi-source data in Nepal. Nat. Hazards Res. 2023, 3, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Kong, B.; Su, Y.; Song, X. On the Water Resource Availability and Rural Households’ Livelihood Adaptation Chain Framework in Mountainous Areas of Nepal: Taking Koshi River Basin as an Example. Mt. Res. 2019, 37, 564–574. [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli, S.; Shrestha, J.; Ghimire, S. Organic farming in Nepal: A viable option for food security and agricultural sustainability. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2020, 5, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Hao, L.; Sun, G. Changing extreme precipitation patterns in Nepal over 1971–2015. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2024EA003563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Tan, M.L.; Zhang, F.; Chun, K.P.; Li, L.; Kabir, M.H. Evaluating the effectiveness of CHIRPS data for hydroclimatic studies. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 1519–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S. Performance assessment of CHIRPS, MSWEP, SM2RAIN-CCI, and TMPA precipitation products across India. J. Hydrol. 2019, 571, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Su, J.; Ren, W.; Lü, H.; Yuan, F. Statistical comparison and hydrological utility evaluation of ERA5-Land and IMERG precipitation products on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Srinivasan, J.A. Comprehensive Evaluation of Near-Real-Time and Research Products of IMERG Precipitation over India for the Southwest Monsoon Period. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhong, R.; Lai, C.; Chen, J. Evaluation of the GPM IMERG satellite-based precipitation products and the hydrological utility. Atmos. Res. 2017, 196, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Gao, W.; Hu, J.; Du, L.; Du, L. Capability of IMERG V6 Early, Late, and Final Precipitation Products for Monitoring Extreme Precipitation Events. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Wood, E.F.; Pan, M.; Fisher, C.K.; Miralles, D.G.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; McVicar, T.R.; Adler, R.F. MSWEP V2 Global 3-Hourly 0.1° Precipitation: Methodology and Quantitative Assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Levizzani, V.; Schellekens, J.; Miralles, D.G.; Martens, B.; de Roo, A. MSWEP: 3-hourly 0.25° global gridded precipitation (1979–2015) by merging gauge, satellite, and reanalysis data. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 589–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shangguan, D.; Liu, S.; Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Evaluation and comparison of CHIRPS and MSWEP daily-precipitation products in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau during the period of 1981–2015. Atmos. Res. 2019, 230, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Comprehensive Evaluation of High-Resolution Satellite Precipitation Products over the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau Using the New Ground Observation Network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.U.; Anjum, M.N.; Afzal, A.; Azam, M.; Hussain, F.; Usman, M.; Javaid, M.M.; Mukhtar, M.A.; Majeed, F. Assessment of Multi-Satellite Precipitation Products over the Himalayan Mountains of Pakistan, South Asia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Ombadi, M.; Gorooh, V.A.; Shearer, E.J.; Sadeghi, M.; Sorooshian, S.; Hsu, K.; Bolvin, D.; Ralph, M.F. PERSIANN Dynamic Infrared–Rain Rate (PDIR-Now): A Near-Real-Time, Quasi-Global Satellite Precipitation Dataset. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 2893–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, K.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, X.; He, J.; Lu, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, B.; et al. TPHiPr: A long-term (1979–2020) high-accuracy precipitation dataset (1∕30°, daily) for the Third Pole region based on high-resolution atmospheric modeling and dense observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, S.; Ma, Y.; Ma, W.; Cun-Bo Han, C. Extreme precipitation detection ability of four high-resolution precipitation product datasets in hilly area: A case study in Nepal. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2024, 15, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, V.; Singh, C. Evaluation of error in TRMM 3B42V7 precipitation estimates over the Himalayan region. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 12458–12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, G.J.; Bolvin, D.T.; Nelkin, E.J.; Wolff, D.B.; Adler, R.F.; Gu, G.; Hong, Y.; Bowman, K.P.; Stocker, E.F. The TRMM Multi-satellite Precipitation Analysis (TMPA): Quasi-Global, Multiyear, Combined-Sensor Precipitation Estimates at Fine Scales. J. Hydrometeorol. 2007, 8, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, Q.; Chen, X.; Xu, C.; Chen, S.; Moss, E.M.; Huang, Y. Evaluation of TRMM Multisatellite Precipitation Analysis in the Yangtze River Basin with a Typical Monsoon Climate. Adv. Meteorol. 2016, 2016, 7329765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malede, D.A.; Agumassie, T.A.; Kosgei, J.R.; Phan, A.B.; Andualem, T.G. Evaluation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates in a Rugged Topographical Basin Over South Gojjam Basin, Ethiopia. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2022, 50, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]