Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We proposed LCFNet, the first unified and physically interpretable framework for unified time-series crack detection and evolution analysis in UAV remote sensing imagery.

- We designed the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv), which integrates Fourier-series decomposition with affine Lie group convolution to enhance anisotropic representation and geometric equivariance.

- We introduced a Lie-group-based Temporal Crack Change Detection (LTCCD) module guided by a physically grounded partial differential equation (PDE) formulation, enabling consistent matching and physically grounded modeling of crack propagation.

- LCFNet achieves superior performance on the UAV-Filiform Crack Dataset (mAP50:95 = 75.3%, F1 = 85.5%, CDR = 85.6%) while maintaining real-time inference (88.9 FPS) and strong generalization in field UAV–IoT monitoring tests.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The proposed framework establishes a new paradigm for UAV-based remote sensing crack monitoring by unifying spatial detection and temporal evolution modeling, bridging deep learning inference with physically interpretable fracture dynamics, and advancing intelligent photogrammetric monitoring of geotechnical structures.

Abstract

Surface crack detection and temporal evolution analysis are fundamental tasks in remote sensing and photogrammetry, providing critical information for slope stability assessment, infrastructure safety inspection, and long-term geohazard monitoring. However, current unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based crack detection pipelines typically treat spatial detection and temporal change analysis as separate processes, leading to weak geometric consistency across time and limiting the interpretability of crack evolution patterns. To overcome these limitations, we propose the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Network (LCFNet), a unified and physically interpretable framework that achieves, for the first time, integrated time-series crack detection and evolution analysis from UAV remote sensing imagery. At its core, the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv) integrates Fourier-series decomposition with affine Lie group convolution, enabling anisotropic feature representation that preserves equivariance to translation, rotation, and scale. This design effectively captures the elongated and oscillatory morphology of surface cracks while suppressing background interference under complex aerial viewpoints. Beyond detection, a Lie-group-based Temporal Crack Change Detection (LTCCD) module is introduced to perform geometrically consistent matching between bi-temporal UAV images, guided by a partial differential equation (PDE) formulation that models the continuous propagation of surface fractures, providing a bridge between discrete perception and physical dynamics. Extensive experiments on the constructed UAV-Filiform Crack Dataset (10,588 remote sensing images) demonstrate that LCFNet surpasses advanced detection frameworks such as You only look once v12 (YOLOv12), RT-DETR, and RS-Mamba, achieving superior performance (mAP50:95 = 75.3%, F1 = 85.5%, and CDR = 85.6%) while maintaining real-time inference speed (88.9 FPS). Field deployment on a UAV–IoT monitoring platform further confirms the robustness of LCFNet in multi-temporal remote sensing applications, accurately identifying newly formed and extended cracks under varying illumination and terrain conditions. This work establishes the first end-to-end paradigm that unifies spatial crack detection and temporal evolution modeling in UAV remote sensing, bridging discrete deep learning inference with continuous physical dynamics. The proposed LCFNet provides both algorithmic robustness and physical interpretability, offering a new foundation for intelligent remote sensing-based structural health assessment and high-precision photogrammetric monitoring.

1. Introduction

Surface cracks serve as early indicators of structural degradation in slopes, pavements, and other civil infrastructures, and their timely and reliable detection is essential for geohazard prevention and structural safety assurance. Conventional ground-based inspections are labor-intensive, subjective, and risky in hazardous environments, motivating the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to acquire high-resolution imagery in a safe and cost-efficient manner. UAVs have been successfully deployed in diverse monitoring tasks, yet the challenges of automatically detecting fine-scale cracks and tracking their temporal evolution remain unresolved due to the elongated morphology of cracks, their low contrast with surrounding textures, and geometric distortions induced by UAV flights.

Object detection has undergone rapid development over the past two decades. Early detectors relied on handcrafted features such as Haar-like descriptors [1], HOG [2], or SIFT-based pipelines, which were highly sensitive to noise and illumination. The introduction of deep learning led to convolutional architectures such as Faster R-CNN [3], Mask R-CNN [4], SSD [5], and RetinaNet [6], which improved detection accuracy through region proposals, multi-scale pyramids, and focal losses. Parallelly, one-stage detectors such as YOLO [7] revolutionized real-time detection and have evolved into modern variants including YOLOv5, YOLOv7, and YOLOv12. More recently, transformer-based detectors (e.g., DETR [8], Deformable DETR [9], DINO [10]) introduced global self-attention and anchor-free bipartite matching to improve long-range reasoning.

For UAV imagery, the detection problem becomes more challenging due to large viewpoint variations, strong scale changes, and cluttered backgrounds. Consequently, specialized lightweight or geometry-aware frameworks have been proposed for aerial scenes [11,12]. Examples include CSPDNet with deformable depthwise separable convolutions, FasterNet-16 for real-time transportation monitoring [13,14], and enhanced YOLO variants that incorporate adaptive multi-scale fusion or dynamic attention [15,16,17]. Additional efforts focus on illumination robustness [18], occlusion handling, or rotation-aware features [19]. Transformer-based UAV detectors such as UAV-DETR have also been explored [20], though they often lack strong inductive biases and may struggle with fine elongated structures [21,22]. Despite these developments, most UAV detectors rely on isotropic convolutions, making them less effective for modeling slender, highly anisotropic cracks that appear under diverse orientations and scales.

Change detection has evolved in parallel as an important direction in remote sensing. Traditional methods relied on image differencing, PCA, or change vector analysis (CVA) [23], which were sensitive to illumination or registration errors. Deep learning significantly advanced the field through Siamese FCNs [24], spatial–temporal attention [25], and dual-scale attention mechanisms [26]. Transformer-based approaches such as BIT [27] and ChangeFormer [28] further improved global temporal modeling. However, these models primarily target land use change or building monitoring [29] and rarely address fine-grained geometric evolution such as crack initiation and propagation.

For UAV temporal monitoring, many studies emphasize multi-epoch co-registration or 3D reconstruction to achieve geometric stability. Reference-image-based bundle adjustment [30,31] and unified bundle adjustment frameworks [32,33] improved temporal alignment for construction and post-disaster monitoring. Feature-driven and volumetric methods (e.g., CFTM [34], SfM-based voxel differencing [35]) provided robust change cues, while LiDAR–UAV fusion enhanced DEM-based displacement analysis [36,37]. Learning-based approaches have also been applied to detect road surface damage or infrastructure defects [38,39], often using multi-level feature differencing or OBIA-based fusion [40]. Despite their success, these frameworks largely depend on handcrafted co-registration or treat bi-temporal inputs independently, making them unsuitable for modeling the continuous, anisotropic growth of cracks observed in real slopes.

To address these limitations, we propose the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Network (LCFNet), a unified and physically interpretable framework that, for the first time, performs time-series crack detection and evolution analysis from UAV imagery. Our approach differs fundamentally from existing single-frame or static detectors by explicitly coupling spatial morphology modeling with temporal correspondence learning. At its core, the proposed Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv) integrates anisotropic strip filtering with affine Lie group convolution, allowing the network to precisely capture the elongated and oscillatory morphology of cracks while maintaining equivariance to translation, rotation, and scale variations. This design effectively mitigates the loss of geometric fidelity commonly observed in traditional isotropic kernels, leading to more accurate fitting of slender structures under complex UAV viewpoints. Beyond spatial detection, a Lie-group-enhanced spatial matching module is introduced for temporal analysis, which constructs inter-epoch correspondence through group-consistent feature alignment. This mechanism enables robust crack matching even under UAV-induced geometric distortions such as panning, scaling, or rotation, thereby supporting reliable discrimination between newly formed, propagating, and stable cracks across time. Furthermore, inspired by continuum mechanics, we formulate a PDE-based interpretation of crack evolution that bridges discrete detection with continuous fracture growth dynamics. This physically grounded formulation enhances interpretability and reveals that the spatial derivatives captured by LCFConv can be regarded as discrete analogues of strain-driven deformation fields, providing a principled foundation for understanding structural degradation over time. LCFNet achieves superior robustness under multi-temporal UAV conditions, preserving crack continuity, suppressing false positives in shadowed or low-texture areas, and maintaining consistent delineation across successive epochs, thereby establishing a new paradigm for temporal-aware UAV crack monitoring.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- We propose a unified UAV-based framework that jointly performs crack detection and temporal evolution analysis, closing the methodological gap between spatial perception and multi-temporal structural interpretation.

- We design the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv), a physically inspired operator based on Fourier decomposition under affine transformations that enhances the representation of elongated and low-contrast cracks.

- We introduce a Lie group-based spatial matching strategy together with a PDE-driven formulation of crack evolution, providing a geometrically robust and interpretable mechanism for tracking structural changes across UAV time series.

- By integrating these components, the proposed LCFNet forms a cohesive and interpretable system for UAV crack monitoring, achieving consistently superior detection accuracy and temporal consistency across all evaluation metrics.

2. Methods

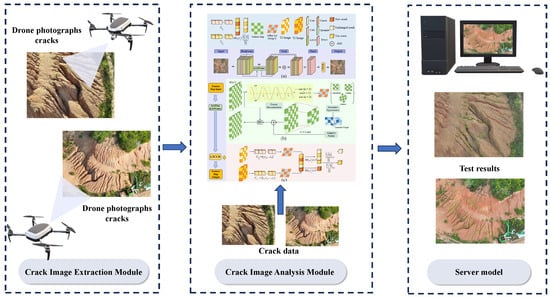

The proposed framework aims to jointly address UAV-based crack detection and temporal change analysis, bridging two tasks that have traditionally been studied in isolation. The overall methodology consists of three components. First, UAV image acquisition and preprocessing are performed to ensure high-resolution, radiometrically consistent inputs suitable for deep learning. Second, we develop the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Network (LCFNet), which enhances the YOLOv12 detector with the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv) to capture the elongated morphology of cracks under geometric variations. Finally, we introduce a Lie group-based temporal change detection module that robustly matches cracks across bi-temporal UAV images, allowing reliable identification of both newly formed and extended fractures. The integration of these components yields a unified and physically interpretable pipeline for UAV-based crack monitoring, as illustrated in Figure 1.

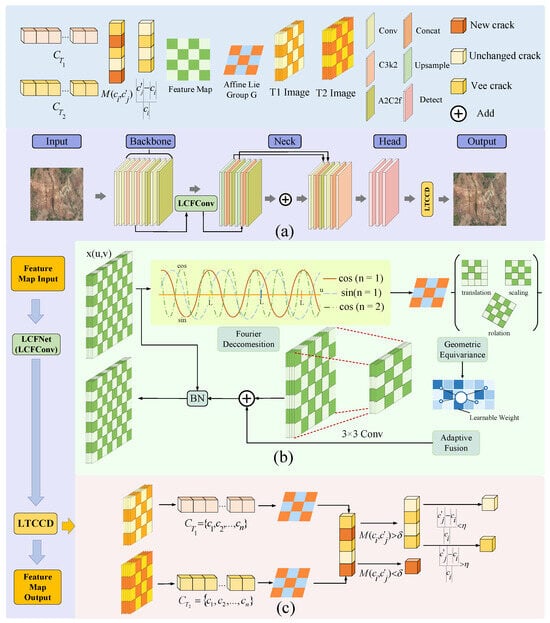

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed UAV-based crack detection and temporal change analysis framework. (a) The pipeline integrates UAV image acquisition, backbone–neck–head detection, and temporal reasoning, enabling joint spatial–temporal crack interpretation. The backbone is equipped with the proposed Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv), which embeds affine Lie group operators to enhance geometric adaptability for elongated and irregular crack patterns. (b) The detailed design of LCFConv: feature maps are decomposed in the Fourier domain to capture local oscillation modes, followed by adaptive fusion guided by learnable weights to maintain geometric equivariance under translation, rotation, and scaling. (c) The Lie-group-based Temporal Crack Change Detection (LTCCD) module compares bi-temporal feature tensors and , measures their manifold distances in the Lie group space, and identifies new, unchanged, and V-shaped extended cracks through adaptive matching. Together, LCFNet and LTCCD form a unified, interpretable pipeline that jointly performs crack detection and temporal evolution analysis from UAV imagery.

2.1. UAV Data Acquisition, Preprocessing, and Dataset Construction

To support robust crack detection and temporal evolution analysis, this study establishes a complete UAV-based imaging, preprocessing, and dataset preparation pipeline. A DJI UAV platform equipped with the Zenmuse L2 LiDAR–RGB integrated system was used to acquire high-resolution aerial imagery, achieving sub-centimeter ground sampling distance at typical flight altitudes. We provide explicit flight-project information: four acquisition sites (S1–S4) located around Longfengshan, Longfuxin Village, Ningxiang City, Hunan Province, with flight altitudes ranging from 30 to 45 m and resulting GSD values between 1.1 and 1.6 cm/pixel (see Table 1). Each site includes 820–1240 images captured under controlled illumination conditions. During data collection, the UAV followed pre-planned serpentine or grid-based trajectories with forward/side overlap ratios matching the site-specific settings reported in Table 1 (70–85% forward and 60–70% lateral overlap). These overlap parameters ensure geometric continuity and stable correspondence across repeated acquisitions while maintaining sufficient redundancy for temporal crack evolution analysis. Camera parameters were maintained consistently across flights, and imaging was conducted under stable illumination to minimize shadows, vegetation motion, and radiometric fluctuation, thereby ensuring cross-session comparability and robust downstream crack interpretation.

Table 1.

Summary of flight projects and data acquisition settings.

To support robust crack detection and temporal evolution analysis, this study establishes a complete UAV-based imaging, preprocessing, and dataset preparation pipeline. A DJI UAV platform equipped with the Zenmuse L2 LiDAR–RGB integrated system was used to acquire high-resolution aerial imagery, achieving sub-centimeter GSD at typical flight altitudes of 50–80 m. Compared with conventional ground surveys, this configuration enables safe access to hazardous slopes while maintaining wide-area coverage and temporal repeatability. During data collection, the UAV followed pre-planned serpentine or grid-based trajectories with 70–80% forward overlap and 60–70% side overlap to ensure photogrammetric alignment across acquisition sessions. Camera parameters were maintained consistently across flights, and imaging was conducted under stable illumination to minimize shadows, vegetation motion, and radiometric fluctuation.

Figure 2 illustrates the UAV platforms employed in our field campaigns, including the DJI Matrice 350 RTK with the Zenmuse L2 LiDAR–RGB module and the DJI Matrice 300 RTK equipped with a high-resolution RGB camera. These systems provide complementary geometric and radiometric sensing capabilities, ensuring that the dataset captures both fine-scale surface discontinuities and consistent multi-temporal imaging conditions.

Figure 2.

DJI UAV platforms used in this study. The left system is a DJI Matrice 350 RTK equipped with the Zenmuse L2 LiDAR–RGB integrated sensor, providing high-accuracy 3D point clouds and high-resolution optical imagery. The right system is a DJI Matrice 300 RTK carrying an interchangeable RGB camera module for complementary aerial acquisitions. These UAV platforms support stable multi-temporal imaging under varying terrain and illumination conditions.

After acquisition, a standardized preprocessing workflow was applied. Geometric correction and orthorectification were performed using onboard GNSS/IMU data and ground control points to ensure accurate spatial registration across time. Radiometric normalization, including histogram equalization and brightness standardization, mitigated illumination inconsistencies between flight missions. The corrected mosaics were then tiled into 512 × 512 patches, improving computational efficiency and enabling the detection of small and elongated crack structures. To enhance model robustness, we applied controlled data augmentation operations: random rotations within to simulate UAV attitude variation; random cropping preserving 70–100% of the original area; scaling sampled from ; and brightness/contrast adjustments within . These augmentation parameters capture common geometric and photometric variations in UAV-based crack monitoring.

To ensure the robustness and generalization of the detection model across these diverse surface features, the UAV-FCD dataset maintains a balanced distribution among the different morphological types. As summarized in Table 2, the dataset comprises a total of 10,588 images, categorized into four distinct classes based on their geometric complexity: Penetrative, Discontinuous, Branched, and Cross-linked filiform cracks. The distribution is remarkably uniform, with each category accounting for approximately 25% of the total samples (ranging from 24.7% to 25.2%). Specifically, Branched Filiform Cracks constitute the largest portion with 2672 images (25.2%), while Discontinuous Filiform Cracks represent the smallest share with 2618 images (24.7%). This high level of class balance prevents the model from developing a bias toward any specific geometric pattern, ensuring that the detector can equally and effectively capture both simple linear rills and complex, interconnected erosion networks in real-world UAV-based slope monitoring. Although we adopt the term “filiform cracks” throughout the dataset, not all surface linear structures are purely tensile cracks in a strict structural–geotechnical sense. A subset of the elongated surface features visible on natural slopes, particularly those appearing on weathered soil or loose colluvium, are shallow rills or erosion-induced grooves rather than fully developed tensile fractures. These erosion features are visually similar to cracks in UAV imagery: both manifest as narrow, elongated, high-contrast line patterns with branching or cross-linked geometries. Consequently, they pose the same detection challenges for UAV-based monitoring, including low contrast, slender morphology, and strong orientation variability.

Table 2.

Image distribution of the four filiform crack categories in UAV-FCD.

Beyond their geometric appearance, the geological materials present at our study sites further shape the surface expressions of these lineaments. The slopes are predominantly composed of highly weathered red clay, silt-rich colluvium, and partially decomposed sandstone, each of which responds differently to stress release and rainfall infiltration. Red clay tends to develop tensile shrinkage cracks under seasonal drying–wetting cycles; colluvial deposits often exhibit shallow erosional rilling due to weak cohesion; and weathered sandstone surfaces may show crustal fractures that mimic structural fissures when viewed from UAV altitude. These material-dependent behaviors explain why tensile cracks and erosion grooves can appear morphologically similar in aerial images, despite distinct geological origins.

We therefore adopt an appearance-driven definition of “filiform cracks”, focusing on surface lineament patterns rather than strict geological genesis. This follows established practice in UAV slope inspection, where both tensile fissures and erosion-induced grooves are treated as surface indicators of instability and hydrological evolution. From a monitoring perspective, both types of lineaments are relevant: erosion rills often develop along near-surface stress-relief zones, and tensile cracks may later evolve into erosion channels under rainfall. Thus, their distinction in aerial imagery is subtle, and their temporal evolution is equally informative for hazard assessment.

In addition, the interaction between geological materials and external drivers, such as runoff concentration, slope gradient, and vegetative cover, contributes to the formation and persistence of the observed lineaments. For example, clay-rich surfaces retain moisture and form smoother discontinuities, while sandy–colluvial mixtures exhibit sharper edges due to granular erosion. These characteristics influence both the detectability of cracks and the reliability of temporal matching in UAV imagery.

We further acknowledge that most linear features in UAV-FCD are terrain-related rather than structural cracks generated by engineered materials. This is consistent with the natural slope settings of our study areas. Nonetheless, all four curated categories, penetrative, discontinuous, branched, and cross-linked, reflect real geomorphological lineament patterns that contribute to slope instability analysis. Our goal is not to differentiate the mechanical origin of each fissure, but to establish a unified computational benchmark for detecting and tracking slender surface discontinuities under UAV imaging. This clarification ensures that the dataset is correctly interpreted as a surface-lineament detection benchmark rather than a purely structural-crack dataset.

All images underwent manual quality control to remove blurred, duplicated, or low-contrast samples. The final dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and testing splits (70%, 15%, 15%), corresponding to 7412, 1588, and 1588 images. Polygonal segmentation masks and oriented bounding boxes were annotated by six researchers and verified by two senior experts in geological hazard monitoring, ensuring label reliability. Additional augmentations such as illumination adjustments and haze simulation were applied to enrich environmental diversity.

Evaluation Metrics. For object detection, we follow COCO conventions and report mean Average Precision (mAP) at IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95 (mAP50:95), as well as mAP50 and mAP75, which reflect localization precision under different overlap constraints. Inference speed is measured in frames per second (FPS). For temporal crack monitoring, we compute precision, recall, and F1-score according to

and measure spatial agreement using Intersection-over-Union (IoU) and Overall Accuracy (OA):

For object detection, the Average Precision (AP) at a given IoU threshold is defined as the integral over the precision–recall curve:

where denotes the precision evaluated at recall level r under IoU threshold . The overall COCO-style mean Average Precision is obtained by averaging AP across all IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95 in steps of 0.05:

This formulation captures detector performance under increasingly strict localization constraints, providing a comprehensive measure of accuracy.

Crack-specific temporal metrics. To ensure deterministic temporal reasoning, a detection at time is matched to a crack at time when the Lie-group-aligned similarity exceeds . Unmatched detections are labeled as new cracks. For matched pairs, an extended crack is defined when the relative area increase satisfies or when the maximum skeletal width increment exceeds pixels.

Under these rules, the Change Detection Rate (CDR) measures the proportion of correctly identified temporal events:

The Crack Extension Accuracy (CEA) quantifies the accuracy of predicted propagation magnitude:

Since all temporal event types are explicitly determined by , both CDR and CEA are reproducible, operational, and consistent with the LTCCD module.

2.2. Longitudinal Crack Fitting Network (LCFNet)

We adopt YOLOv12 as the detection framework and extend it with a geometry-aware module termed Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv). Cracks typically exhibit elongated and oscillatory structures, which can be effectively represented through Fourier basis decomposition rather than purely spatial convolution. Instead of simply combining Fourier features and geometric transformations, LCFConv integrates localized multi-harmonic representation with affine transformation behavior at the kernel level, enabling the convolution to adapt its orientation and anisotropy in a mathematically controlled manner. This coupling is specifically designed for thin, low-contrast filiform cracks whose geometry deviates from the assumptions of existing geometric CNNs. Motivated by Fourier series expansion, we reformulate crack-oriented filtering as the superposition of sinusoidal functions under affine group actions, thereby enhancing feature representation along longitudinal directions and maintaining equivariance to translation, rotation, and scaling.

Formally, a 2D feature map can be expanded along a crack-oriented axis u as a truncated Fourier series

where u denotes the longitudinal axis, v the transverse axis, L the fitting length scale, and the Fourier coefficients modulated along the transverse dimension. This decomposition naturally encodes oscillatory crack patterns with controllable frequency resolution.

Fourier representations are known to be sensitive to high-frequency fluctuations, and UAV imagery inevitably contains noise patterns arising from sensor response, illumination variation, and background textures. In LCFConv, this issue is mitigated by using a truncated Fourier expansion: the dominant energy of filiform cracks resides in the low- to mid-frequency range, while the higher-order harmonics primarily capture background noise. As a result, the coefficients corresponding to small N remain stable and informative, whereas very high-order terms are intentionally discarded.

The truncation number N therefore acts as a controllable frequency-resolution parameter. Smaller values of N capture the coarse longitudinal oscillations that characterize most cracks, while moderate values (e.g., or ) introduce additional geometric flexibility for curved or slightly wavering crack patterns. This is consistent with the scale statistics of the UAV-FCD dataset, where the principal oscillation wavelengths fall within the first few harmonic bands.

To embed geometric invariance, we consider the affine Lie group

with group action

where is a rotation matrix. Under this transformation, the Fourier basis becomes

preserving the equivariance property of LCFConv with respect to rotation and scaling.

The LCFConv output at position p is constructed as

where is a discretized subset of affine transformations, are Fourier-modulated coefficients learned during training, and are adaptive weights normalized via a softmax. This operator-level integration allows LCFConv to express both deformation-aware alignment and frequency-domain oscillations within a single lightweight module, a capability not provided by existing Fourier CNNs or Lie-group-based convolutions when used independently.

In practice, the affine Lie group G in Equation (5) is discretized into a compact set that captures only the small geometric perturbations typically induced by UAV imaging. Specifically, we sample three rotation angles , two scale factors , and two pixel-level translations , resulting in a total of transformation candidates. These transformations are applied in a single batched operation using pre-computed affine grids, avoiding repetitive interpolation and reducing the effective complexity of Equation (5) to a linear pass over the feature map. Because is deliberately kept small, the group traversal adds only a marginal constant factor to computation and does not change the asymptotic cost of the convolution.

To ensure stability, we combine Fourier-based anisotropic responses with standard isotropic convolution:

and embed residual blending as

where denotes the SiLU activation.

Finally, the Fourier interpretation of crack propagation connects naturally with a parabolic PDE model. Let be the crack response at time t, then

where the diffusion term models smooth extension along the crack axis, and the sinusoidal terms encode oscillatory variations captured by Fourier harmonics. LCFConv can therefore be viewed as a discrete operator that unifies localized harmonic modeling with affine geometric behavior, providing a principled and task-specific formulation beyond a simple combination of existing techniques. By embedding several LCFConv blocks into the CSP backbone and head layers of YOLOv12, the resulting detector, LCFNet, achieves robust crack detection under diverse orientations, scales, and geometric distortions.

2.3. LieGroup Temporal Crack Change Detection (LTCCD)

Given that UAV-based monitoring is typically conducted over multiple time periods, a central challenge lies in accurately identifying whether a crack is newly generated or has extended compared to an earlier observation. Conventional change detection approaches often rely on axis-aligned bounding box overlaps or pixel-wise subtraction, which are highly sensitive to geometric misalignment caused by UAV flight angle variations, local terrain relief, or scale differences in altitude. In particular, IoU-based matching assumes that two detections are well aligned in the image plane, an assumption that frequently fails for narrow filiform cracks whose apparent orientation and scale vary substantially across UAV viewpoints [41,42,43]. As a result, standard IoU matching often underestimates true correspondences and produces ambiguous temporal labels.

To address these limitations, we introduce a Lie group enhanced spatial matching algorithm that treats cracks as geometric entities embedded in an affine transformation group, thereby ensuring robustness under translation, rotation, and scale variation. Rather than replacing IoU entirely, the proposed method can be viewed as an extension that evaluates overlap after plausible geometric compensation, thus retaining the interpretability of IoU while correcting for UAV-induced distortions.

Let the sets of detected cracks at two time points and be

Each crack is represented by its oriented bounding box obtained from LCFNet, where is the center, are width and height, and is the in-plane orientation. Instead of directly comparing these boxes via Euclidean IoU, we embed them into the affine Lie group and define the matching similarity as

where is the affine transformation associated with group element g and is a discretization of the group. This matching effectively aligns candidate cracks under plausible UAV-induced distortions before computing overlap. In this sense, the method retains IoU as its core matching criterion but augments it with a physically motivated alignment step that compensates for orientation and scale discrepancies. A correspondence is established if , with a predefined threshold.

To facilitate a fair comparison, we also implement a traditional IoU-based matching baseline and observe that it often fails to associate the same crack between and when the UAV viewing angle differs by more than or when altitude variation causes apparent scale shrinkage. The Lie group enhanced method explicitly addresses these limitations by restricting geometric adjustments to a compact set of affine transformations that reflect real UAV perturbations, thereby improving stability without significantly increasing computational complexity.

To ensure computational feasibility, the maximization over in Equation (10) uses the same compact discretization described earlier, yielding a total of candidate affine transformations. All candidates are evaluated in parallel using a single batched grid_sample operation, and the best-aligned overlap is obtained through a fused reduction. This implementation keeps the traversal overhead extremely low in practice: evaluating all elements in contributes less than 6% of the total inference time. The reported real-time speed of 88.9 FPS fully includes this group-search overhead, as the LieGroup matching is executed within the timed forward pass without any post-processing.

A temporal correspondence between and is established when the group-aligned similarity satisfies . We adopt a fixed threshold , selected based on the empirical distribution of aligned overlaps in the training set. True crack continuations typically yield aligned IoU values in the range , whereas unrelated detections fall below , making a stable separation margin that is robust to UAV-induced geometric perturbations. We further verify threshold values in the range and find that temporal performance metrics (F1, CDR, CEA) vary by less than 0.3 points, indicating that the method is not overly sensitive to the exact choice of . For reproducibility, all experiments in this work use the fixed correspondence threshold .

To further capture the dynamic nature of crack evolution, we model the crack width function defined along the crack skeleton as a spatio-temporal field evolving under anisotropic growth dynamics. Its temporal progression is approximated by a nonlinear partial differential equation of the form

where and denote second-order derivatives parallel and perpendicular to the crack axis respectively, is the UAV image intensity, is a Heaviside activation capturing thresholded edge responses, and are balancing coefficients. The PDE describes how crack width diffuses longitudinally, remains constrained laterally, and grows when edge energy exceeds a threshold, consistent with physical propagation behavior of surface fractures. In practice, repeated application of LCFConv filters approximates this PDE evolution, linking the discrete detection framework with continuous geometric modeling.

Based on the above formulation, a crack is labeled as a new crack if no corresponding satisfies . Conversely, if such a correspondence exists but the estimated width or area has increased beyond a scale-adjusted threshold, i.e.,

then is categorized as an extended crack. Here and are empirically chosen parameters controlling sensitivity to expansion.

Based on the above formulation, the classification of temporal crack events follows explicitly defined criteria. A detection at time is labeled as a new crack if no crack at time satisfies , meaning that no geometrically consistent predecessor exists even after affine alignment. Conversely, when a valid correspondence is found, the event is categorized as an extended crack if the relative area increase satisfies or if the maximum skeletal width increment exceeds along the crack centerline. We empirically set and pixels based on dataset statistics, corresponding to the minimal visually discernible crack growth under 640 × 640 UAV imaging. These deterministic rules enable the CDR and CEA metrics to be evaluated in a fully operational manner and ensure that the temporal labels are unambiguous and reproducible across experiments.

The superiority of this Lie group-based approach stems from its ability to handle UAV-specific acquisition challenges. Traditional pixel-wise or IoU-based matching fails to generalize across viewpoint variations and altitude-induced scale drift, whereas the proposed affine-consistent formulation provides a principled way to compensate for these distortions before computing similarity. Due to varying flight paths, imaging altitudes, and viewpoint rotations, direct pixel-wise alignment is prone to false alarms. By embedding the matching into the affine group structure, we achieve equivariance to the dominant geometric variations and maintain stable crack tracking across temporal sequences. Furthermore, the PDE-driven formulation reflects the anisotropic nature of crack propagation observed in real-world slopes, thereby aligning algorithmic predictions with physical fracture processes. In summary, the proposed temporal detection framework not only provides robust geometric matching but also yields physically interpretable indicators of crack evolution, enabling reliable UAV-based structural monitoring.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Settings

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB memory), an Intel Core i9-13900K CPU, and 128 GB RAM, running under Ubuntu 22.04 LTS. The software environment consisted of Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.3, CUDA 12.1, and cuDNN 8.9, with the training pipeline built upon the official YOLOv12 framework. Data preprocessing and visualization were implemented in OpenCV 4.8 and Matplotlib 3.7.

All UAV images used in this study were captured by the DJI M300 RTK platform with a 24 mm RGB camera. The dataset contains only single-epoch RGB images and does not include orthomosaics, DEMs, or multi-temporal photogrammetric products. The complete UAV-FCD dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets following a 70:20:10 ratio, corresponding to 7412/2118/1058 images, respectively. All subsequent experiments, including ablation studies, strictly follow this fixed 7:2:1 split to ensure reproducibility and fair comparison.

The training configuration was carefully designed to balance convergence stability and UAV crack detection accuracy. The input image resolution was fixed at pixels, which is sufficient to preserve the fine-scale geometry of elongated cracks while maintaining computational feasibility. Each model was trained for 300 epochs with a batch size of 16 on a single GPU. To avoid excessive augmentation effects during the later stages of training, the mosaic augmentation was disabled after 50 epochs by setting close_mosaic = 50, ensuring that the model gradually adapts to realistic crack appearances. Early stopping was enabled with a patience of 50 epochs, preventing overfitting when the validation loss plateaued.

Optimization was performed using the AdamW optimizer, which provides decoupled weight decay and stable convergence for transformer-enhanced architectures. The base learning rate was initialized at , decayed to through a cosine annealing schedule (cos_lr = True). The momentum parameter was fixed at 0.937 to stabilize gradient updates, while the weight decay was set to 0.0005 to regularize the network and prevent overfitting. These hyperparameters were empirically validated to achieve robust detection of small, low-contrast crack structures.

During training, the experimental outputs, including intermediate checkpoints, logs, and visualizations, were organized under the runs/train directory with the experiment tag exp_crack. The dataset was defined by the configuration file crack.yaml, which specified the training and validation splits, class definitions, and annotation formats. Caching was disabled (cache = False) to ensure scalability to large UAV datasets without exceeding GPU memory constraints.

It is worth noting that all ablation studies—including Fourier truncation analysis for LCFConv and matching, threshold sensitivity tests in the LTCCD module, were conducted under the exact same training environment, dataset split, augmentation settings, and optimizer configuration. This consistent setup ensures that performance differences arise solely from architectural modifications rather than training variance.

Overall, this experimental setup ensures that the proposed LCFNet can fully exploit high-resolution UAV imagery while maintaining efficient and stable training dynamics, providing a fair comparison baseline for subsequent performance evaluation and ablation studies.

3.2. Main Results

Table 3 summarizes the performance of representative detectors and change detection frameworks adapted to UAV-based crack monitoring. Both detection performance (mAP50:95, mAP50, mAP75) and temporal change detection performance (Precision, Recall, F1-score, IoU, OA) are reported. To capture crack-specific monitoring requirements, we further introduce Change Detection Rate (CDR) for evaluating the proportion of true temporal changes detected, and Crack Extension Accuracy (CEA) for quantifying the precision of expansion estimation. We present the experimental results in this section, while the interpretation and mechanism-level analysis are provided separately in Section 5 (Discussion) to avoid mixing results with methodological explanations.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of detection and change detection methods on UAV-based crack monitoring.

As shown in Table 3, the YOLO series offers strong and efficient one-stage baselines, but their convolutional receptive fields remain limited in modeling elongated and fine-grained crack structures. Two-stage detectors achieve competitive accuracy yet suffer from reduced inference speed. Transformer-based detectors such as Deformable DETR, DINO, and RT-DETR improve robustness under geometric distortions, while ChangeFormer exhibits superior temporal stability but falls short in detection precision. Mamba-based detectors demonstrate a promising balance between accuracy and efficiency, though their long-range modeling capability is still insufficient for complex crack morphologies. Beyond generic object detectors, we additionally compare two crack-specific baselines tailored for fine-grained structural perception. CrackForest [44] relies on hand-crafted structural features and random structured forests, yielding moderate detection performance (mAP50:95 of 52.4) with high speed (38.4 FPS), but its handcrafted design leads to fragmented predictions and poor generalization under UAV viewpoints. In contrast, the Transformer-based CrackFormer [45] achieves higher accuracy (mAP50:95 of 71.8) and better captures thin crack patterns, yet its encoder–decoder architecture incurs high computational cost, resulting in only 22.6 FPS and limiting its suitability for real-time UAV deployment.

In comparison, our proposed LCFNet, built upon the YOLOv12 backbone (CSPDarknet-P6), achieves the highest performance across both detection and change detection metrics. LCFNet improves mAP50:95 by more than 5% over YOLOv12 and significantly surpasses all baselines, including crack-specific methods, in CDR and CEA, demonstrating its strong capability for UAV-based crack monitoring and temporal evolution analysis.

3.3. Ablation Study

3.3.1. Overall Effectiveness

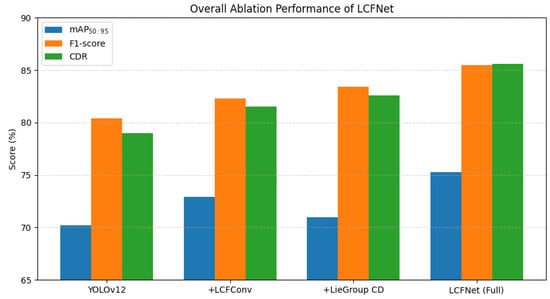

To verify the effectiveness of each proposed component, we first conduct ablation experiments on UAV crack monitoring by progressively adding the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv) and the LieGroup-based temporal change detection module. Table 4 reports results in terms of both object detection (mAP50:95, mAP50, mAP75) and temporal change detection (Precision, Recall, F1, IoU, OA, CDR, CEA). Figure 3 visually displays the performance results of the comparison.

Table 4.

Overall ablation study on UAV crack monitoring. Detection metrics are in percentages. Change detection metrics are averaged across new and extended crack categories.

Figure 3.

Overall ablation results of the proposed framework. Each bar group represents the progressive integration of LCFConv and LieGroup CD modules into the YOLOv12 baseline. The complete LCFNet achieves consistent improvements across detection (mAP50:95) and temporal change metrics (F1 and CDR).

The baseline YOLOv12 detector achieves reasonable performance but shows limited accuracy on elongated crack instances and temporal correspondence. Incorporating LCFConv leads to higher detection scores, reflected by consistent gains across all spatial metrics. Introducing the LieGroup-based temporal change detection module further improves temporal evaluation results. The full LCFNet obtains the best overall performance, exceeding YOLOv12 by more than 5% in mAP50:95 and achieving the highest values in all temporal metrics.

3.3.2. Ablation on LCFConv Internal Design

All ablation experiments are conducted by replacing or modifying individual modules on top of the YOLOv12 baseline, ensuring that any performance changes originate solely from the introduced components rather than from differences in the underlying detector. We further analyze the contribution of different components inside LCFConv. Four configurations are compared: (1) replacing LCFConv with standard convolution, (2) using strip convolution without Fourier expansion, (3) Fourier expansion with limited harmonics (), (4) full LCFConv with multi-harmonic Fourier basis, isotropic residual branch, and normalization. Results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ablation on LCFConv design. Detection and change detection metrics reported as before.

The results show that strip convolution already improves detection of elongated cracks compared to standard convolution. Incorporating Fourier expansion further enhances the ability to capture oscillatory structures. Increasing the number of harmonics N yields additional gains, while combining with isotropic residual branches and normalization achieves the best overall performance.

3.3.3. Ablation on LieGroup Temporal Change Detection

All ablation experiments are conducted by replacing or modifying individual modules on top of the YOLOv12 baseline, ensuring that any performance changes originate solely from the introduced components rather than from differences in the underlying detector. We evaluate the design choices of the LieGroup-based temporal crack change detection module. We compare: (1) a naive IoU-based matching between bounding boxes, (2) affine Lie group matching without PDE constraint, (3) full LieGroup matching with PDE-driven crack evolution regularization. Results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Ablation on LieGroup temporal change detection. Detection and change detection metrics reported as before.

The results confirm that IoU-based matching is inadequate for UAV imagery, as it cannot compensate for geometric misalignment. Affine Lie group matching improves temporal consistency by aligning cracks under rotation and scaling. Further adding PDE-driven evolution regularization yields the best performance, improving F1, CDR, and CEA, maintaining stable detection results.

3.3.4. Ablation on Fourier Harmonic Truncation Number N

To further investigate the impact of the Fourier decomposition in Equation (1), we analyze how the truncation number N affects the expressive capacity of LCFConv. Since N determines the highest harmonic included in the Fourier expansion, it directly influences the ability of the network to model oscillatory crack patterns while also introducing additional computational cost. We evaluate under identical settings, and report the detection and temporal change performance in Table 7.

Table 7.

Ablation on harmonic truncation number N. Detection and change detection metrics are reported in percentages.

The results show a clear progression as N increases. From to , both detection accuracy and temporal consistency improve steadily. This trend reflects the physical characteristics of surface cracks: UAV imagery commonly presents elongated structures with moderate, smooth oscillations rather than abrupt high-frequency variations. Lower-order harmonics primarily capture the dominant longitudinal pattern, while additional harmonics introduce richer frequency components that better describe the subtle undulations produced by weathering, erosion, and terrain-induced texture irregularities. Consequently, increasing N enlarges the frequency span of LCFConv and enhances its ability to model longitudinal oscillation modes, leading to consistent gains in mAP50:95, F1, CDR, and CEA.

When N increases beyond 4, the performance begins to saturate and then slightly declines. Higher-order harmonics in UAV imagery tend to correlate more with noise patterns than with meaningful crack morphology, causing the filter responses to overfit high-frequency background textures or illumination fluctuations. This behavior results in marginal decreases in accuracy and temporal metrics for , accompanied by a drop in FPS due to increased computation.

Overall, achieves the best balance between representation capacity and stability. It provides sufficient harmonic resolution to capture the dominant oscillatory behavior of cracks while avoiding the noise sensitivity and computational overhead associated with larger N. This observation aligns with the measured oscillation scales of cracks in the UAV-FCD dataset, where the primary geometric variations fall within the frequency range represented by the first four harmonics.

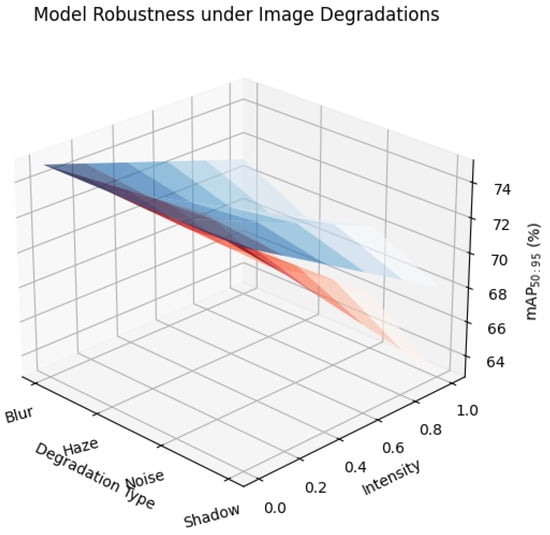

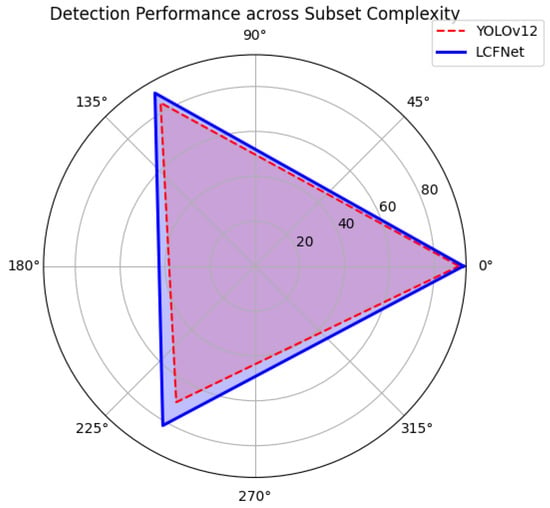

3.4. Robustness and Generalization Test

The comprehensive visualization results in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 further verify the superiority and generalization ability of the proposed LCFNet under diverse UAV imaging conditions. As shown in Figure 4, which evaluates model robustness against common degradation factors including blur, haze, noise, and shadow, the proposed method demonstrates a markedly slower performance decay compared with YOLOv12. This robustness arises from the Fourier-based representation embedded in the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv), which decomposes elongated crack textures into harmonic basis functions. Such frequency-domain modeling acts as a low-pass stabilizer, preserving crack-aligned oscillations while suppressing high-frequency noise. Furthermore, the affine Lie group transformation ensures equivariance to geometric distortions caused by UAV flight-path variations, leading to smoother accuracy curves across degradation intensity levels.

Figure 4.

Model robustness under image degradations. The figure illustrates detection accuracy (mAP50:95) of YOLOv12 and LCFNet under various degradation types (blur, haze, noise, and shadow) and increasing intensity levels. LCFNet demonstrates significantly slower accuracy decay, indicating enhanced resilience to UAV imaging artifacts.

Figure 5.

Detection performance across subset complexity levels. Each vertex corresponds to a scene subset (simple, moderate, complex) in the UAV crack dataset. Compared with existing detectors, LCFNet maintains higher accuracy and stability as scene complexity increases.

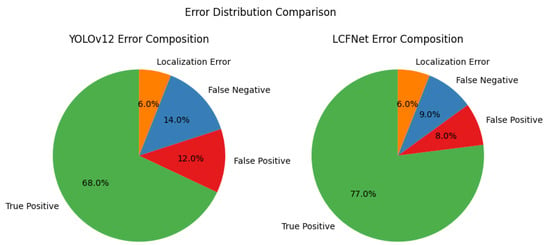

Figure 6.

Detection error distribution comparison between YOLOv12 and LCFNet. The proposed model achieves higher true-positive rates and significantly reduces false positives and false negatives, indicating improved structural precision and robustness.

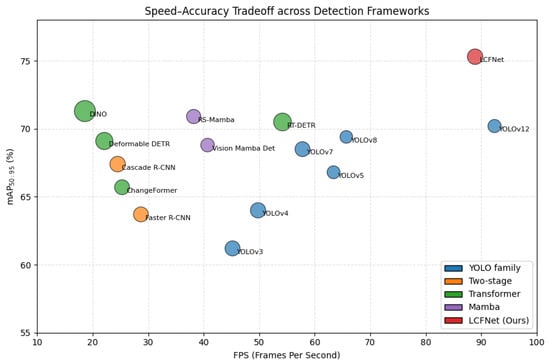

Figure 7.

Speed–accuracy tradeoff across representative detection frameworks. Bubble size indicates parameter scale, and color represents model family. LCFNet achieves the best overall balance between inference efficiency and detection accuracy among YOLO, Transformer, and Mamba-based architectures.

Figure 5 presents the radar analysis across subsets with different scene complexity. Traditional detectors, such as YOLOv8 and Cascade R-CNN, exhibit pronounced performance degradation when facing occluded or texture-overlapping crack regions, reflecting their limited receptive field anisotropy. In contrast, LCFNet maintains high accuracy in both moderate and complex scenes, validating that the proposed LCFConv effectively enhances directional sensitivity through longitudinal kernel fitting. This directional inductive bias, combined with affine group equivariance, allows the network to dynamically align its convolutional responses with the underlying crack geometry, even under vegetation camouflage or severe shadow interference.

Figure 6 provides an error composition analysis comparing YOLOv12 and LCFNet. The proportion of false positives and false negatives is significantly reduced in LCFNet, which benefits from its PDE-driven temporal matching module. By modeling crack evolution as an anisotropic diffusion process, the LieGroup-based change detection framework constrains growth along the crack axis while regularizing lateral expansion. This physically interpretable mechanism improves correspondence stability between bi-temporal UAV images and minimizes mismatched detections around extended or newly formed cracks. Such PDE-guided regularization complements the Fourier-based spatial representation, yielding a coherent spatial–temporal formulation that bridges discrete convolutional learning and continuous geometric evolution.

Finally, Figure 7 illustrates the speed–accuracy tradeoff across representative detectors. Despite integrating additional geometric modeling components, LCFNet achieves a superior balance between inference speed (88.9 FPS) and detection accuracy (mAP50:95 = 75.3). Compared with Transformer-based methods (e.g., DINO, RT-DETR) and Mamba-based architectures, LCFNet occupies the optimal region in the tradeoff space, demonstrating that its efficiency-oriented design does not compromise accuracy. The combination of harmonic decomposition and group-equivariant filtering yields compact yet expressive feature representations, leading to both computational parsimony and enhanced crack sensitivity.

In summary, these analyses collectively highlight that the integration of Fourier-series-based convolution and PDE-guided temporal modeling enables LCFNet to achieve robust, interpretable, and efficient UAV crack monitoring across challenging conditions. The method not only surpasses prior CNN-, Transformer-, and Mamba-based frameworks in quantitative performance but also aligns closely with the physical process of crack propagation and geometric deformation, offering a unified and theoretically grounded solution for UAV-based structural health assessment.

3.5. Visualization

To qualitatively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed LCFNet, we provide visualization results comparing it with the baseline YOLOv12 detector. Visualization is particularly important in crack monitoring, as it not only reflects detection accuracy but also reveals the ability of a model to capture the elongated and low-contrast structures that are often overlooked in quantitative metrics. By directly observing detection outcomes on representative UAV images, we can better illustrate the robustness and interpretability of our method.

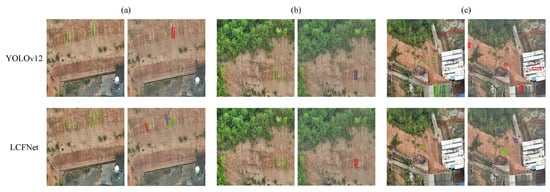

As shown in Figure 8, YOLOv12 tends to miss thin or fragmented cracks and occasionally produces false positives on soil textures and shadows. LCFNet produces more complete detections on elongated and low-contrast cracks and reduces false alarms in these scenes. In the visualization, green regions denote the original crack extent, red regions indicate the portions identified as crack extension between temporal pairs, and blue regions highlight newly formed cracks. These qualitative comparisons show that LCFNet yields more stable crack delineation and fewer misdetections in UAV imagery.

Figure 8.

Qualitative comparison between YOLOv12 and the proposed LCFNet on three typical landslide inspection scenes. (a) Bare slope: features weak textural contrast and subtle surface cracks; LCFNet provides clearer localization and boundary precision than YOLOv12. (b) Vegetation-covered slope: dense vegetation causes camouflage and occlusion; LCFNet successfully distinguishes landslide traces hidden beneath foliage. (c) Construction-area slope: contains complex man-made structures and shadow interference; LCFNet maintains more accurate contour detection and suppresses false alarms on background objects. In the visual results, red boxes indicate correctly detected crack structures, blue marks false positives, and green highlights cracks that were missed by YOLOv12 but recovered by LCFNet, allowing a clear comparison of accuracy and error reduction across scenes.

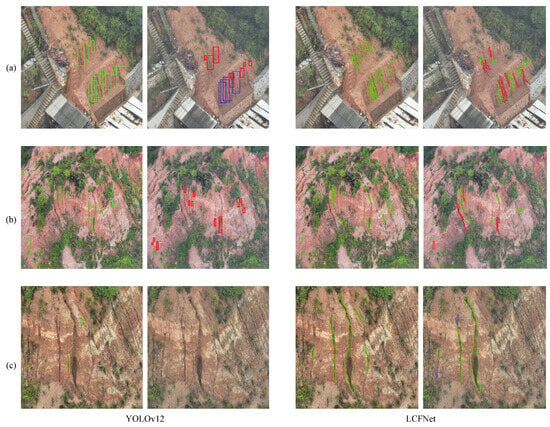

As shown in Figure 9, LCFNet provides clearer crack outlines and more consistent localization than YOLOv12 across different terrain conditions. Here, green corresponds to pre-existing crack structures, red marks extended segments, and blue represents novel crack occurrences. In scene (a), YOLOv12 produces redundant rectangular detections overlapping with construction materials, while LCFNet gives tighter and more accurate bounding regions. In scene (b), vegetation and shadows lead YOLOv12 to multiple false positives; LCFNet preserves a more continuous crack shape under these conditions. In scene (c), weathered soil creates blurred textures that cause YOLOv12 to miss faint discontinuities, while LCFNet outputs more complete crack traces. Overall, the qualitative results indicate that LCFNet produces more reliable crack depictions and reduces missed and false detections in complex slope environments.

Figure 9.

Visual comparison of landslide crack detection between YOLOv12 and the proposed LCFNet across three representative scenarios: (a) construction slope with man-made interference, (b) vegetation-covered red-soil slope, and (c) weathered bare slope with erosion marks. LCFNet adopts an irregular-oriented bounding strategy, enabling more accurate localization of elongated and oblique cracks while effectively suppressing redundant false detections around texture edges. In the visual results, red boxes indicate correctly detected crack structures, blue marks false positives, and green highlights cracks that were missed by YOLOv12 but recovered by LCFNet, allowing a clear comparison of accuracy and error reduction across scenes.

4. Practical Application Testing

To verify the generalization ability and real-world applicability of the proposed LCFNet, we constructed a UAV–IoT system for automated crack monitoring over landslide-prone slopes in Changsha, Hunan Province. The system integrates UAV-based image acquisition, crack analysis, and remote server inference, as illustrated in Figure 10. The UAV platform employs a DJI Phantom 4 Pro equipped with a 20-megapixel RGB camera (4000 × 2250 resolution) capable of shooting from 0°–90°. UAVs continuously captured oblique and nadir images along pre-defined flight routes. The acquired crack images were transmitted in real time via the IoT module to a remote server running the proposed LCFNet model. The inference results, including crack localization and temporal change detection, were visualized on a monitoring terminal for further inspection. The overall workflow consists of three modules: (1) crack image extraction, (2) crack image analysis using LCFNet, and (3) server-based result visualization and longitudinal change comparison.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the crack change detection system of the IoT based on LCFNet. (a) network pipeline; (b) Lie group-based complex feature convolution (LCFConv) for robust morphology capture; (c) temporal crack change detection (LTCCD) for status categorization.

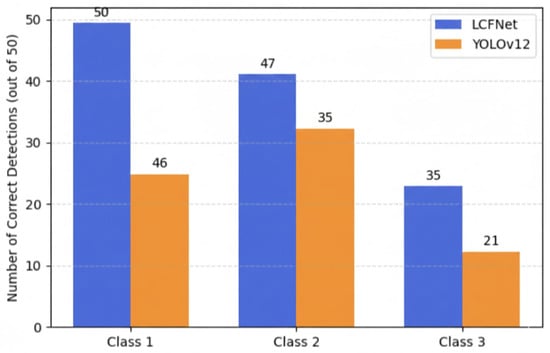

To further evaluate the robustness of the system under field conditions, we conducted a series of tests across three types of crack scenes: Class 1 (clear and regular cracks), Class 2 (partially occluded or irregular cracks), and Class 3 (fine or discontinuous cracks under strong illumination variation). For each class, 50 UAV images were randomly selected for testing. The comparison results between LCFNet and the baseline YOLOv12 are shown in Figure 11. From the figure, it can be observed that LCFNet achieves the highest detection completeness in all categories, detecting all 50 images in Class 1, 47 in Class 2, and 42 in Class 3, whereas YOLOv12 detected only 46, 35, and 21 images, respectively. The superiority of LCFNet is most evident in Class 3, where crack structures are extremely thin and fragmented. This improvement stems from the anisotropic strip filtering and affine Lie group convolution embedded in LCFConv, which enhance sensitivity to elongated and oscillatory crack features while maintaining robustness against rotation and scale variation. These field results demonstrate that the proposed LCFNet not only generalizes well to complex UAV scenes but also enables stable, time-consistent monitoring through the IoT-based system. Such capability is of practical significance for early risk assessment of geological hazards and infrastructure maintenance.

Figure 11.

Comparison of detection results between LCFNet and the baseline YOLOv12 across three crack categories, each containing 50 UAV images. The vertical axis indicates the number of correctly detected samples (out of 50). LCFNet detects nearly all samples in Class 1 and maintains high accuracy in Class 2 and Class 3, where YOLOv12 suffers from severe omissions. The significant improvement on Class 3 demonstrates that LCFNet effectively captures slender and discontinuous crack structures under challenging UAV imaging conditions.

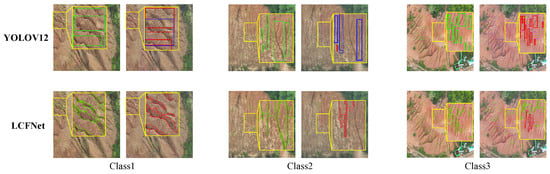

As illustrated in Figure 12, compared with the baseline YOLOv12, the proposed LCFNet shows clear superiority across three representative UAV crack detection scenarios. In Class 1, where cracks are wide and irregular, YOLOv12 tends to produce fragmented bounding boxes and blurred boundaries due to limited geometric adaptability, while LCFNet achieves smoother contour fitting and more accurate morphological alignment through its longitudinal crack fitting mechanism. In Class 2, where cracks extend continuously along the mountain slope, YOLOv12 often suffers from structural discontinuity and background interference, whereas LCFNet maintains coherent detection by preserving the continuity of elongated fractures and effectively distinguishing cracks from soil textures. In Class 3, which contains numerous small and discontinuous cracks, LCFNet captures finer crack segments with higher sensitivity and better completeness, overcoming the under-detection issue of YOLOv12. Overall, these results demonstrate that LCFNet can adaptively fit the elongated morphology of cracks under diverse terrain conditions, ensuring higher precision and continuity in UAV-based crack inspection.

Figure 12.

Qualitative comparison between YOLOv12 and the proposed LCFNet on three representative UAV-based crack inspection scenarios. (a) Class 1: YOLOv12 tends to produce fragmented rectangular boxes and incomplete boundaries, while LCFNet precisely fits the elongated morphology through irregular rectangular fitting and continuous edge delineation. (b) Class 2: in this complex terrain, YOLOv12 often fails to capture the full continuity of cracks along the slope, whereas LCFNet maintains structural coherence and avoids over-segmentation by leveraging the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv). (c) Class 3: LCFNet demonstrates superior detection sensitivity for multiple small-scale fractures, achieving denser and more consistent localization than YOLOv12.

5. Discussion

This work operates directly on raw multi-view UAV images rather than relying on photogrammetric products such as orthomosaics or digital elevation models (DEM). Although full photogrammetric reconstruction can provide globally consistent geometry, its resampling and mosaicking procedures often smooth high-frequency textures and distort narrow filiform cracks on sloped terrains. By retaining the original perspective imagery, the proposed framework preserves native resolution, contrast, and surface texture, enabling more accurate modeling of fine-scale crack morphology. Multi-angle raw views (nadir and oblique) also provide richer geometric cues than a single orthorectified surface, which is advantageous for the detection of elongated cracks with complex depth variations. Future extensions may incorporate DEM information when large-scale topographic context is beneficial, but for crack-level interpretation, raw imagery offers superior structural fidelity.

Beyond the imaging strategy, a deeper discussion of why the proposed LCFNet achieves substantial improvements is warranted. The frequency-domain branch of LCFConv captures oscillatory patterns characteristic of filiform cracks, enabling the network to distinguish true crack traces from background textures that exhibit irregular or non-periodic variations. Meanwhile, the Lie-group geometric component enhances robustness to UAV-induced viewpoint fluctuations, a common source of misalignment in slope monitoring. The empirical gains observed in the ablation studies can therefore be interpreted as a consequence of jointly modeling longitudinal texture continuity and local geometric transformations, two factors that strongly govern crack visibility under aerial observation.

The choice of evaluation metrics also warrants discussion. For the spatial detection task, mAP is adopted because each UAV-FCD image includes manually annotated oriented bounding boxes and segmentation masks, allowing classical supervised object detection evaluation. mAP50:95 is computed by matching each predicted bounding box to ground-truth annotations at IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95, following the widely accepted COCO protocol. This multi-threshold design also reveals whether a detector is merely coarsely locating cracks or genuinely achieving fine-grained boundary alignment, which is essential for slender lineaments.

In contrast, temporal crack monitoring is formulated as a categorical event classification problem, where each crack between two time-adjacent images is labeled as unchanged, newly formed, or extended. Because the output is a discrete semantic state rather than a bounding box, confusion-matrix–based metrics (precision, recall, F1, IoU, OA) more accurately reflect decision correctness. Importantly, temporal evaluation always uses pairs of UAV images acquired at different epochs, each with manually validated ground-truth change labels. Although confusion-matrix metrics could be adapted to detection, doing so would sacrifice comparability with existing detectors, making mAP the more appropriate choice for evaluating spatial localization.

Taken together, these design choices highlight a fundamental distinction in UAV-based crack analysis: spatial localization and temporal interpretation are not symmetric tasks and therefore benefit from different performance metrics. The use of raw multi-view UAV imagery provides high-fidelity geometric information, while the complementary metric sets allow LCFNet to be evaluated fairly and rigorously in both spatial and temporal dimensions.

Despite these advantages, several limitations deserve attention. First, severe vegetation occlusion or deep shadows can still obscure crack visibility, occasionally leading to missed detections even after geometric alignment. Second, the discretized Lie-group transformation set cannot fully represent extreme viewpoint or scale changes, suggesting room for a continuous or learned transformation model. Third, while the UAV-FCD dataset covers diverse slope conditions, certain structural cracks on engineered materials (e.g., concrete retaining walls) remain underrepresented and may require domain adaptation.

Future work may extend LCFNet in several directions: integrating LiDAR-derived micro-topographic cues to enhance depth-awareness; developing adaptive harmonic selection to improve frequency-domain robustness; incorporating multi-temporal transformers for end-to-end tracking rather than pairwise matching; and expanding the dataset to include man-made structures and post-disaster terrains. These extensions would further enhance the generality and operational applicability of the proposed framework.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated UAV-based crack detection and temporal change analysis for slope monitoring, with a focus on the challenges posed by elongated, low-contrast fracture patterns in complex terrains. Traditional detectors often fail to capture such structures due to their isotropic receptive fields and sensitivity to geometric variations across different flight sessions. To address these limitations, we proposed the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Network (LCFNet), which integrates the Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution (LCFConv) to better model anisotropic crack morphology and embeds an affine Lie group-based matching scheme for robust temporal change detection. Extensive experiments demonstrate that LCFNet effectively captures fine-scale crack patterns under varying orientations and scales, while the proposed Lie group matching mechanism reliably distinguishes between new and extended cracks across multi-temporal UAV imagery. Compared to baseline detectors, our framework achieves superior robustness and consistency, particularly in handling geometric distortions induced by UAV flights. Moreover, the PDE-inspired formulation of crack evolution provides a physically interpretable perspective on fracture growth, linking the discrete detection outputs to underlying propagation dynamics. By combining these modules, the proposed LCFNet achieves the best overall performance. On our UAV-FCD datasets, it reaches mAP50:95 = 75.3 (+5.1 over YOLOv12), mAP50 = 93.0 (+4.9), and F1 = 85.5 (+5.1), with corresponding CDR = 85.6 and CEA = 83.1.

In future work, we plan to extend the proposed framework towards large-scale multi-sensor fusion, integrating UAV-based LiDAR and hyperspectral modalities with visual imagery to capture both structural and material properties of monitored slopes. Additionally, real-time deployment on edge devices will be investigated to support rapid in-field hazard assessment and early warning systems for geotechnical safety.

Overall, this study establishes a foundational framework for reliable UAV-based remote sensing of structural crack evolution, unifying detection, temporal reasoning, and physical interpretability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W.; methodology, C.W.; software, C.W.; validation, C.W. and J.T.; formal analysis, C.W.; investigation, C.W.; resources, J.T.; data curation, J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, J.T.; visualization, C.W.; supervision, J.T.; project administration, J.T.; funding acquisition, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Scientifc Research Project of Xiang JiangLab (No.23XJ02002), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (No.2025JJ50396).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCFNet | Longitudinal Crack Fitting Network |

| LCFConv | Longitudinal Crack Fitting Convolution |

| LTCCD | Lie-group-based Temporal Crack Change Detection |

| PDE | Partial Differential Equation |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| HPT | Height-Point Tracking |

| GSD | Ground Sampling Distance |

| RSOD | Remote Sensing Object Detection |

| RT-DETR | Real-Time Detection Transformer |

| RS-Mamba | Remote Sensing Mamba Network |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once (object detection framework) |

| CFTM | Common-Feature-Track-Matching |

| RIBC | Reference-Image-Based Co-registration |

| UBA | United Bundle Adjustment |

| OBIA | Object-Based Image Analysis |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| F1 | Harmonic Mean of Precision and Recall |

| CDR | Change Detection Rate |

| CEA | Crack Extension Accuracy |

| UAV-FCD | UAV-Filiform Crack Dataset |

References

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; pp. I–I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Pang, J.; Gao, W.; Chen, K.; Sun, J. DINO: DETR with Improved DeNoising Anchor Boxes for End-to-End Object Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Du, D.; Tian, Q.; Sebe, N. The unmanned aerial vehicle benchmark: Object detection, tracking and baseline. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 1141–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Chen, Q.; Chen, W. A new lightweight network for efficient UAV object detection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Huang, Z.; Chang, Y.C.; Liu, L.; Pei, Q. A low-cost and lightweight real-time object-detection method based on uav remote sensing in transportation systems. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Huang, L.; Ruan, C. Small object detection in UAV images based on Yolov8n. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Lan, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shang, K.; Zhang, F. DAU-YOLO: A Lightweight and Effective Method for Small Object Detection in UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Cui, M.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yu, S. MFR-YOLOv10: Object detection in UAV-taken images based on multilayer feature reconstruction network. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jing, Y.; Zhao, J.; Cui, G. LAM-YOLO: Drones-based Small Object Detection on Lighting-Occlusion Attention Mechanism YOLO. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.00485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Kong, X.; Shimada, T.; Tomiyama, H. TOE-YOLO: Accurate and efficient detection of tiny objects in UAV imagery. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, K.; Gan, Z.; Zhu, G. UAV-DETR: Efficient End-to-End Object Detection for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01855. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Lang, C.; Yao, Y.; Han, J. Anchor-free oriented proposal generator for object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5625411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Ji, S. A new spatial-oriented object detection framework for remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 4407416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Review article digital change detection techniques using remotely-sensed data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1989, 10, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, R.C.; Le Saux, B.; Boulch, A. Fully convolutional siamese networks for change detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; pp. 2117–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yao, H.; Xu, X. A Spatial-Temporal Attention-Based Method and a New Dataset for Remote Sensing Image Change Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 198–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L. A Deeply Supervised Attention Metric-Based Network and an Open Aerial Image Dataset for Remote Sensing Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5604816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, Z. Remote sensing change detection using bi-temporal image transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3968–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.G.C.; Patel, V.M. Changeformer: A transformer-based siamese network for change detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Shrivastava, P.; Dhurvey, P. Change Detection Techniques in Remote Sensing: A Review. Int. J. Wirel. Mob. Commun. Ind. Syst. 2017, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]