Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Using PRISMA data, adding additional bands to a 3-band base SDB model improves performance.

- Despite its lower spectral resolution, Landsat 8 OLI outperforms PRISMA for SDB, except near the limit of seafloor detection (20–30 m).

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Hyperspectral sensors may add value to SDB, especially at depths near the seafloor detection limit.

- Hyperspectral data should be viewed as complementary to multispectral data for SDB.

Abstract

Coastal bathymetric mapping is essential for marine conservation, navigation, and environmental management. Satellite-derived bathymetry (SDB) is a cost-effective solution to mapping bathymetry over large shallow areas. However, traditional multispectral instruments can produce poor depth estimates for several reasons, including image noise, atmospheric interference, waves and white caps, and where the seafloor-reflected signal is weak, e.g., in areas with deep water or a low-albedo seafloor. This study investigates the potential of PRISMA hyperspectral imagery to improve SDB performance. Through an iterative process, hyperspectral bands were added to a base Random Forest model, and model performance was assessed across different water pixel classes, including bright shallow substrates, seagrass, and deep water. The model’s performance was then compared to that of multispectral Landsat 8 imagery. The results demonstrated that adding hyperspectral bands to the base model improved bathymetric accuracy, particularly in deeper waters (25 m–30 m), where Mean Absolute Error decreased by 2.51 m from a 3-band to a 24-band model. However, the best-performing model was achieved using Landsat 8, resulting in a lower Mean Absolute Error (1.88 m) than the optimized 24-band PRISMA model (2.01 m). Our findings suggest that although additional hyperspectral bands can improve bathymetry estimation, multispectral imagery may still be more effective for general coastal bathymetry mapping despite its lower spectral resolution.

1. Introduction

Mapping and monitoring coastal environments is essential for marine conservation, safe navigation, environmental research, and management of the world’s heavily populated coastal zones. The creation of accurate bathymetric maps is a fundamental part of coastal monitoring and is essential for understanding the biological and physical processes in coastal environments [1]. Satellite-Derived Bathymetry (SDB) is an increasingly popular method for mapping the depth of shallow waters due to its practicality and low cost, especially in remote or inaccessible areas [2]. Unlike traditional bathymetric methods such as acoustic surveys, which require specialized equipment and boat-based fieldwork, typical “empirical” SDB methods estimate water depth by applying a predictive model trained on coincident pairs of depth and spectral reflectance values. However, this method implicitly assumes that information derived from spectral reflectance alone can be predictive of water depth, and it is subject to important sources of error when variations in optical water quality and/or seafloor coverage are not fully accounted for.

For example, one type of seafloor coverage that can be problematic for SDB models is dense aquatic vegetation, including Posidonia oceanica, which covers over 12,000 km2 of seafloor in the Mediterranean Sea [3], where it is the dominant seagrass species [4]. Due to its low albedo, submerged P. oceanica, even at shallow depths, often appears similar to deep water in satellite imagery, causing water depth to be poorly predicted in such areas. As a result, the spectral resolution of typical multispectral sensors has been demonstrated to limit SDB models’ ability to reliably predict depth in areas with seagrass meadows [5]. Previous studies have also demonstrated that SDB models using multispectral imagery, such as from Sentinel-2, have a limited accuracy beyond depths of 15 m and are influenced by seafloor albedo [6]. These problems are an instance of the broader issue of spectral non-uniqueness in aquatic remote sensing, in which different combinations of seafloor spectral reflectance, water quality, and water depth, can lead to near-identical spectral reflectance signatures. This makes inversion of multispectral observations an ill-posed problem [7] and makes discrimination between variations in depth and variations in bottom reflectance with such data subject to large errors [8].

Hyperspectral sensors, with their additional spectral resolution, have long been used to distinguish and identify terrestrial land cover types [9], and may prove similarly advantageous for SDB in aquatic environments. In the case of seagrass meadows, the absorption characteristics of plant pigments produce a unique spectral reflectance pattern that could allow hyperspectral sensors to better distinguish P. oceanica from deep water, and more generally to disentangle the effects of variations in substrate, water quality, and depth on the measured spectral signal. While previous research has demonstrated the effectiveness of airborne hyperspectral sensors such as HyMap and MIVIS to distinguish seagrass species from other benthic substrates [10,11], less research has been carried out on the application of satellite-borne hyperspectral sensors in bathymetric mapping (but see [12,13,14]). For example, it has been hypothesized that by increasing the number of bands in the visible spectrum, less field-based training data could be required for bathymetric models [6], but it is not clear whether benefits arising from the greater spectral resolution of spaceborne hyperspectral sensors outweigh their typically lower signal/noise ratio [15,16]. It therefore remains uncertain whether hyperspectral imagery can meaningfully reduce SDB errors, including for Posidonia-rich areas in the Mediterranean, particularly due to the analytical complexities associated with hyperspectral data and the optical properties of the water column, which can significantly obscure the spectral signatures of submerged vegetation [17].

This study investigates whether hyperspectral imagery can improve the accuracy of SDB models in areas with low albedo seafloor coverage, particularly in the case of P. oceanica meadows on the southern coast of France. To address that question, we determine whether adding hyperspectral bands improves the accuracy of an SDB model, evaluate whether such improvement can be attributed to an improved prediction in seagrass-covered and/or deep areas, and compare the performance of an SDB model using hyperspectral data to a comparable multispectral model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

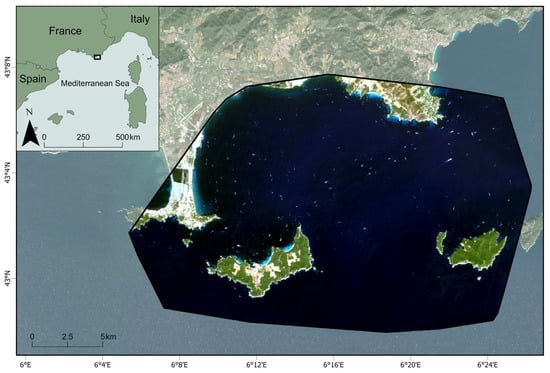

The study area (Figure 1) covers part of the Mediterranean coastal waters of Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur in France, extending between the communes of Carqueiranne and Le Lavandou. This area was selected due to its generally clear Mediterranean waters, extensive coverage of P. oceanica, and the ability to visually distinguish between bare and Posidonia-covered substrates with confidence in shallow waters (see Figure 2). This species of seagrass is found throughout the entire infralittoral zone of the Mediterranean Sea, from sea level to depths greater than 30 m [18]. The Mediterranean Sea is also characterized by some of the most oligotrophic waters in the world, with limited availability of plant nutrients, which restricts phytoplankton growth and results in exceptionally clear waters. This clarity is visible from satellite imagery [19], making the region an ideal location for the application of SDB techniques. Furthermore, the study area is well-documented, with accessible imagery and bathymetric data that support the goals of this study.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area. PRISMA imagery from 19 August 2021. Coordinates are in EPSG:2154. The inset map in the top left shows the study area’s regional context.

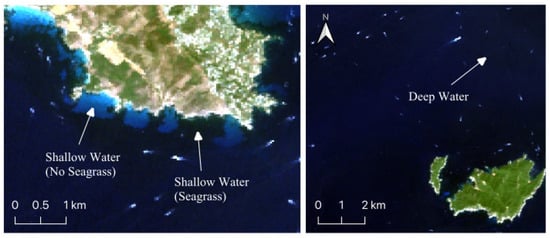

Figure 2.

Visual representation of three classes of pixels in the study area: Shallow Water (No Seagrass), Shallow Water (Seagrass), and Deep Water.

2.2. Remote Sensing Data Acquisition and Processing

The hyperspectral imagery used in this study was obtained from PRecursore IperSpettrale della Missione Applicativa (PRISMA). PRISMA is a medium-resolution hyperspectral imaging satellite providing 66 bands in the Visible/Near-Infrared (VNIR) spectrum, with a spatial resolution of 30 m and a spectral resolution narrower than 12 nm in the 400 nm–2500 nm spectral range [20]. The specific image used for this study was captured on 19 August 2021, at approximately 10:28 UTC, and has a cloud coverage of 2.63%. The data was downloaded as a Level 1 (L1) Top of Atmosphere (TOA) product, which has been radiometrically calibrated and georeferenced.

Prior to other processing, ACOLITE (v. 20250402.0), an open-source software package developed for atmospheric correction of satellite imagery over aquatic environments, was used for the atmospheric correction of the PRISMA image [21], which was then exported as a GeoTIFF file and georeferenced in ArcGIS Pro (v. 3.3.2) using a Sentinel-2 image of the study area as reference.

Preliminary analysis was conducted on the atmospherically corrected image, manually selecting 20 pixels for each of three distinct pixel classes across the image based on visual interpretation: Shallow Water (No Seagrass), Shallow Water (Seagrass), and Deep Water (Figure 2). Spectral reflectance data from bands 4–46 (VNIR) were extracted from the chosen pixels. Bands 1–3 were excluded due to missing data, and bands with wavelengths longer than 800 nm were excluded during preliminary analysis due to their limited usefulness for SDB. Each pixel class’s reflectance values at each wavelength were averaged to examine spectral differences between the pixel classes. To test for significant differences between the three classes in the 430 nm–600 nm range (bands 4–25), pairwise Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was performed using the adonis2 function in the R (v. 4.5.2) vegan package (v. 2.7-2) [22] with Euclidean distance and 9999 permutations. Jeffries–Matusita (JM) distances were then computed with the JMdist function from the R varSel package (v. 0.2) [23] following a principal component analysis (PCA) using the first five principal components.

The multispectral imagery used in this study was obtained from the Landsat 8 satellite’s Operational Land Imager (OLI), a multispectral sensor providing 5 bands in the VNIR spectrum with a spatial resolution of 30 m; this was chosen due to its spatial resolution matching that of PRISMA. The specific image used for this study was captured on August 30, 2021, at approximately 10:18 UTC, and has a cloud coverage of 1%. The data was downloaded as an L1 Terrain Precision TOA product, and ACOLITE was used for atmospheric correction of the image to produce a surface-level reflectance output.

2.3. In Situ Bathymetric Data Acquisition

The bathymetric data used in this study was collected by the Service national d’Hydrographie et d’Océanographie de la Marine (SHOM) using single-beam echosounders and leveling staffs [24]. The data was recorded over a period from 20 August 1972 to 12 November 1973. The instrument measured depths from above sea level down to a maximum of 1145 m, providing a larger depth range than necessary for this study. The measurements were recorded with a vertical resolution of 0.2 m and referenced to the Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT). This data served as reference depth data for the training and testing of the bathymetric models.

2.4. Feature Extraction and Dataset Preparation

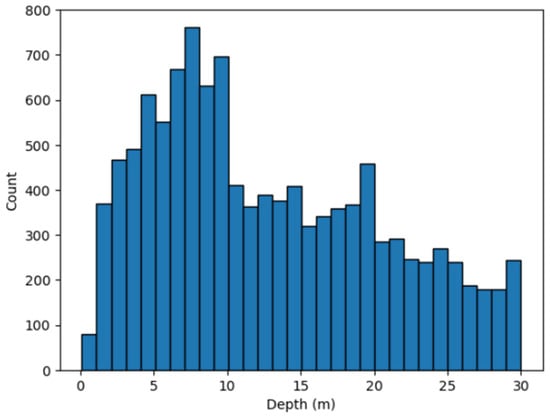

In preparation for machine learning modeling, the datasets were prepared by extracting the relevant information. Spectral reflectance values for PRISMA bands 4–46 (VNIR) and Landsat 8 bands 1–5 were sampled in QGIS for each depth measurement point. Points with depth values above sea level (Z < 0 m), missing data, and points falling outside the spatial extent of the PRISMA image were excluded. Points with depths greater than 30 m were also excluded because pixels beyond this threshold were considered to be optically deep, meaning that seafloor-reflected photons no longer influenced the measured spectral reflectance of the pixel, leading to a negligible relationship between bathymetry and pixel reflectance and thus an inability to estimate bathymetry from the reflectance measurements. Additionally, a threshold was applied to the reflectance values of PRISMA band 43, removing all pixels with a reflectance greater than or equal to 0.02 to eliminate potential non-water features in the image, such as boats, marinas, and large rocks above water. A similar threshold was applied to Landsat 8 band 5, removing all pixels with a reflectance greater than or equal to 0.02. These thresholds were selected based on visual examination of the imagery and the understanding that water reflects less light at longer wavelengths than most non-water features. The distribution of the remaining depth values (n = 11,475) in the dataset used for model development and testing is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Histogram showing the distribution of depth values from the in-situ data after dataset preparation.

2.5. Machine Learning Model Development

2.5.1. Iterative Band Addition for SDB Model Optimization

To evaluate the potential for hyperspectral imagery to improve bathymetric predictions, the first phase of model development focused on determining whether the addition of hyperspectral bands, beyond the bands typically involved in SDB with multispectral imagery, improves the accuracy of a model’s bathymetric predictions. All models were trained and tested using 5-fold cross-validation with a constant random state value across iterations to ensure consistency and reproducibility of results. The accuracy of model predictions was quantified as the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) when comparing predictions to the test set. All SDB models and MAE calculations in this study were performed using functions from the Scikit-learn module (v. 1.7.2) [25] in Python.

An iterative approach was taken to assess the impact of adding bands, which involved training and testing a series of Random Forest (RF) regression models. First, an RF model was trained using a baseline configuration with three PRISMA bands. These bands, specifically bands 33 (665 nm), 21 (559 nm), and 12 (490 nm), were chosen because they correspond most closely to the central wavelengths of the Red–Green–Blue (RGB) bands (bands 4, 3, and 2) of Sentinel-2, a satellite multispectral instrument frequently used in SDB applications [26]. This approach was chosen to ensure that any improvement in model performance could be directly attributed to the addition of spectral information, as well as indicating the bands that most contributed to the improvement.

In each iteration, one additional band from the remaining hyperspectral bands was temporarily added to the model, and the MAE value was recalculated. At the end of each iteration, the band that resulted in the greatest reduction in MAE was permanently included in the model for subsequent iterations. This process was repeated until no further improvement in MAE could be achieved by adding additional bands. The outcome of this process was a set of bands that optimized the model’s performance, ranked in order of addition.

2.5.2. Testing Model Improvements on Pixel Classes

The second phase of model development focused on determining whether an improved performance observed in the model (from Section 2.5.1) was specifically attributable to the additional bands’ ability to better differentiate between deep water and seagrass in shallow water. The objective here was to determine whether the narrow hyperspectral bands, which can be sensitive to the spectral signature of plant pigments and differentiate between absorption by pigments and water, provide sufficient information to meaningfully improve bathymetric predictions in and around seagrass-covered areas.

To investigate this, the model resulting from the iterative approach was tested separately on each of the three distinct pixel classes: Shallow Water (No Seagrass), Shallow Water (Seagrass), and Deep Water. For each class, 30 pixels were manually selected based on visual interpretation of the imagery. For the two shallow-water classes, a similar range (1.4 m–11.3 m) and distribution of depths were chosen. Deep Water pixels were selected from points with actual depths between 25 m and 30 m that were not visually obstructed by boats or other features.

The rationale behind this approach was to determine whether an improvement in overall model performance could be attributed specifically to an improved prediction of seagrass-covered or deep-water areas. If an improvement in MAE was driven by better differentiation between the spectral signatures of Shallow Water (Seagrass) and Deep Water, a greater reduction in MAE could be expected for one of these classes compared to shallow pixels without seagrass. Alternatively, if the improvement in model performance was greater for the Shallow Water (No Seagrass) pixels, or evenly distributed among the three classes, it would suggest that the additional bands improved predictions by providing spectral information not specifically related to seagrass absorption characteristics.

To analyze the results, MAE values for each pixel class were recorded across models with an increasing number of bands and plotted to visualize and compare changes in accuracy.

2.5.3. Modeling SDB Using Multispectral Imagery

For comparison to the PRISMA-based models, an SDB model was also developed using Landsat 8 multispectral data, following the same methodology as the baseline 3-band configuration described in Section 2.5.1, but using four bands, specifically the Landsat 8 OLI bands 1–4. These bands were chosen as they most closely correspond to the wavelength range of PRISMA’s bands 4–46, which were used earlier in the study. The performance of this model was also evaluated using MAE.

2.6. Comparison to Support Vector Machine

To assess the robustness of our results to the model type used here, Random Forest, we repeated the modeling from Section 2.5.1, Section 2.5.2 and Section 2.5.3 using a Support Vector Machine (SVM) and compared the results to those produced by the Random Forest modeling.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

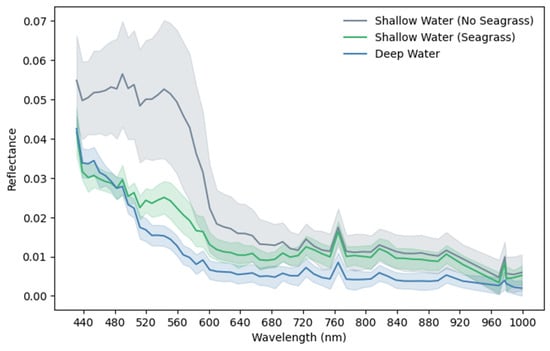

An initial analysis of the spectral reflectances of the three pixel classes (Figure 4) demonstrates a close similarity between the spectral signatures of Deep Water and Shallow Water (Seagrass). In contrast to these two classes, the Shallow Water (No Seagrass) signature exhibits significantly higher reflectance between the wavelengths 430 nm and 600 nm. However, subtle differences between the Shallow Water (Seagrass) and Deep Water signatures are observed in the shorter wavelengths of the visible spectrum. From approximately 450 nm to 550 nm, Shallow Water (Seagrass) has a flatter spectral slope, as its reflectance is lower than that of Deep Water at 450 nm, is approximately similar at 490 nm, and higher at 550 nm. The 450 nm–490 nm range is the only one in the VNIR spectrum where Shallow Water (Seagrass) has lower reflectance than Deep Water.

Figure 4.

Mean reflectance spectra with standard deviation error bands for three different pixel classes: Shallow Water (No Seagrass), Shallow Water (Seagrass), and Deep Water.

All pairwise PERMANOVA tests showed statistically significant (p < 0.001) differences between the pixel classes in the 430 nm–600 nm wavelength range, and JM distance values indicated strong separability between all classes, with the greatest separation observed between Shallow Water (No Seagrass) and Deep Water (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pairwise comparison statistics between Shallow Water (No Seagrass), Shallow Water (Seagrass), and Deep Water pixel classes in the 430 nm–600 nm wavelength range, including PERMANOVA p-values and JM distances.

3.2. Model Performance with the Addition of Hyperspectral Bands

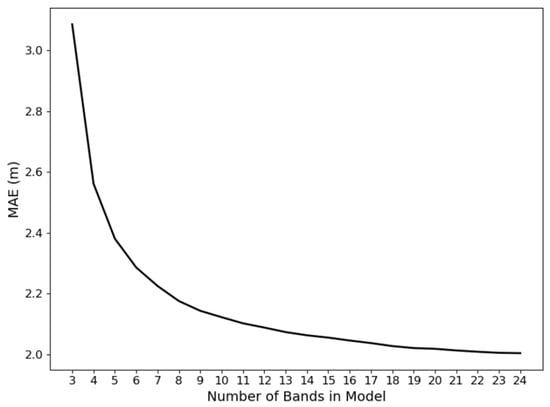

The iterative selection and addition of the best-performing hyperspectral bands to the SDB model resulted in improved bathymetric predictions in the 0 m–30 m depth range, as demonstrated by a significant reduction in MAE as the number of bands increased (Figure 5). The addition of the first extra band to the baseline 3-band configuration reduced the model’s MAE by 0.50 m, from 3.06 m to 2.56 m, with subsequent additions resulting in progressively smaller improvements as the effectiveness of additional information diminished with each added band. The first band added to the baseline model, as selected through the iterative process, was band 6 (446 nm), followed by band 20 (551 nm) and band 22 (567 nm). The iterative process ended with a 24-band model, which obtained an MAE of 2.01 m.

Figure 5.

Relationship between MAE and the number of bands used in the RF model.

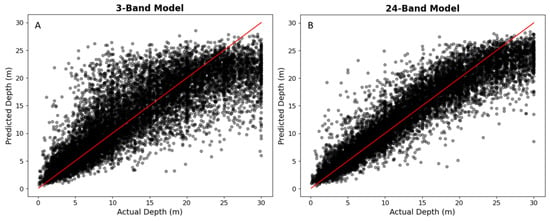

The improved model accuracy with the addition of bands is further illustrated in Figure 6, which shows the measured depths (x-axis) and predicted depths (y-axis) of the test set. The 24-band model has a tighter clustering of points around the 1:1 line than the 3-band model. Both models exhibit a positive linear association, with a weaker association at depths greater than 20 m. However, the 24-band model demonstrates more accurate predictions at greater depths than the 3-band model, exemplified by the smaller dispersion of points in the 25 m–30 m range. Also, while a few outliers in the 3-band model were not predicted better in the 24-band model, there is a visible reduction in the quantity of outliers in the 24-band model. Overall, the model’s MAE in the 0 m–30 m range improved by 1.05 m with the addition of the 21 spectral bands.

Figure 6.

Comparison of RF depth prediction accuracy between (A) the 3-band model (MAE = 3.06 m, R2 = 0.69) and (B) the optimized 24-band model (MAE = 2.01 m, R2 = 0.86). A 1:1 line has been drawn in red.

3.3. Prediction Improvements on Pixel Classes

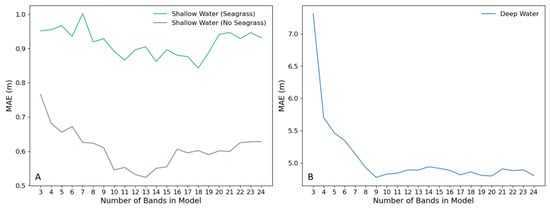

Testing the models from the iterative approach separately on Shallow Water (No Seagrass), Shallow Water (Seagrass), and Deep Water pixels revealed the differing effects of additional hyperspectral bands depending on pixel class (Figure 7). Shallow Water (Seagrass) depth prediction accuracy was the least improved by the additional bands, with MAE slightly increasing with the first and second additional bands and only improving by 0.02 m from the 3-band to the 24-band model. The most accurate model, with 18 bands, had an MAE of 0.84, compared to 0.95 for the 3-band model. Shallow Water (No Seagrass) depth prediction accuracy improved to a greater extent, reducing MAE from an initial value of 0.77 m for the 3-band model to 0.52 m at its lowest value for the 13-band model.

Figure 7.

Change in MAE with additional bands in (A) Shallow Water (Seagrass), Shallow Water (No Seagrass), and (B) Deep Water pixels.

Finally, Deep Water depth prediction accuracy was the most significantly improved, with an MAE reduction from 7.31 m for the 3-band model to 4.78 m for the 9-band model, and 4.80 for the 24-band model.

Overall, shallow water pixel depths were significantly more accurately predicted than deep water pixel depths. The addition of bands to the baseline model generally decreased MAE values for all three classes of selected pixels, until approximately 10 bands, after which MAE values were relatively constant or increased slightly with the further addition of bands. Note that this specific result, which pertains to the 90 pixels manually selected from the three pixel classes, is different from what was seen for the full test dataset, where the addition of bands continued to reduce MAE until a total of 24 bands were included in the model.

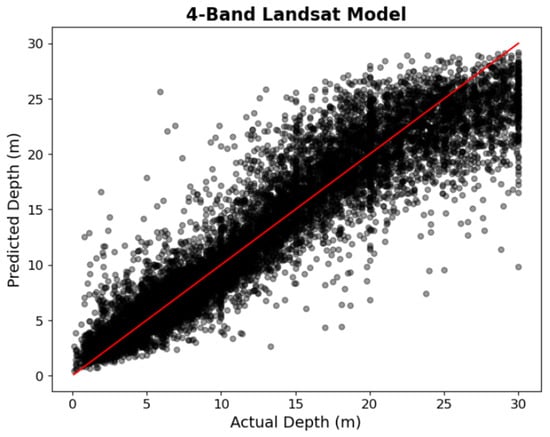

3.4. Model Performance Using Multispectral Imagery

The SDB model using Landsat 8 data resulted in the lowest MAE (1.88 m) of all models developed in this study. The prediction accuracy of the model is illustrated in Figure 8. The model has a positive linear association and a similar clustering of points around the 1:1 line to that of the 24-band PRISMA model in Figure 6, including a similar weaker association at greater depths.

Figure 8.

RF depth prediction accuracy of the 4-band Landsat 8 model (MAE = 1.88 m, R2 = 0.88). A 1:1 line has been drawn in red.

3.5. Comparison to SVM Model

The SVM model performed similarly, but slightly worse, than the RF model in all comparisons. The 3-band PRISMA SVM model produced an MAE of 3.43 m (compared to 3.06 m for RF), and the iterative addition of bands resulted in a final 26-band model that produced an MAE of 2.27 m (compared to 2.01 m for RF). The bands initially added by the iterative process were the same as for RF, with band 6 (446 nm) added first, followed by band 20 (551 nm) and band 22 (567 nm). Reduction in MAE from adding bands, for the three pixel types, also showed a similar pattern: The bulk of the improvement was seen for Deep Water pixels, whose MAE was reduced by 2.07 m, from 7.79 m for the 3-band model to 4.86 m for the 26-band model, while MAE values for the Shallow Water (Seagrass) and Shallow Water (No Seagrass) pixels were both only reduced by 0.04 m. Finally, the Landsat SVM model produced an MAE of 2.21 m (compared to 1.88 m for RF); as for the RF model, this slightly outperforms the full 26-band model based on PRISMA data.

4. Discussion

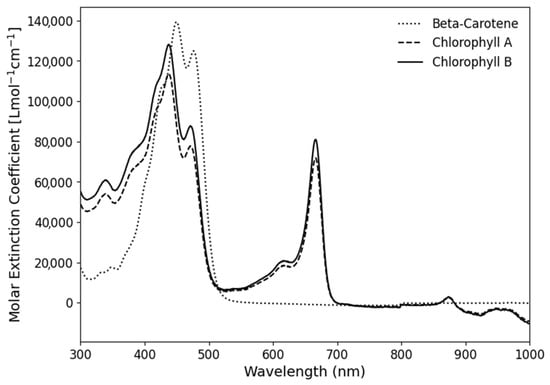

The initial comparison of spectral signatures of the three pixel classes (Section 3.1) suggests that the high spectral resolution of hyperspectral imagery has the potential to improve the distinction between Shallow Water (Seagrass) and Deep Water pixels at shorter wavelengths, particularly around 450 nm–550 nm. Notably, the 450 nm wavelength corresponds closely to a key feature in the absorption spectra of several photosynthetic pigments found in P. oceanica (Figure 9), where a large amount of incident light is absorbed. The existence of this absorption feature, combined with the fact that the 446 nm band was the first to be added in the iterative band addition process, suggests that a band in this wavelength range may indeed contribute to differentiating between absorption of ~450 nm wavelengths by seagrass and water, respectively.

Figure 9.

Absorption spectra of key plant pigments. Plotted from data sourced from [27].

The results from the iterative approach indicate that the addition of a select set of hyperspectral bands can meaningfully improve SDB model accuracy, although only a limited number of bands are needed to do so. This is consistent with previous studies which have found that approximately 15 strategically placed bands in the 400 nm–800 nm range are sufficient for most coastal applications, even when using sensors with medium or lower spatial resolution [28]. Furthermore, the error values observed here are comparable to those reported elsewhere within a similar depth range and using similar methods [6]. Our study also highlights a potential limitation of methods that consider only a limited amount of spectral information, such as the approach proposed by [29], as they may exclude valuable spectral information that could improve model accuracy.

The first band added in the iterative process, band 6 (446 nm), aligns closely with the chlorophyll absorption peak (Figure 9), which points to the reason this specific wavelength could play a role in better distinguishing Shallow Water (Seagrass) from Deep Water and thereby reduce SDB prediction errors for these classes. The addition of this band substantially decreases MAE values for deep water, while it slightly increased them for the shallow seagrass pixels. The subsequent two bands added, with wavelengths of 551 nm and 567 nm, respectively, do not correspond to high-absorption features in the pigment absorption spectra, but they do fall in the wavelength range with maximum separation between the reflectance values of deep water and shallow seagrass, which may explain their role in further decreasing MAE values. It is also important to note that these bands are both adjacent to band 21, the green band used in the baseline model. The reason behind the reduction in MAE associated with the addition of these bands is thus unclear; one possible explanation is that their adjacency to band 21 may help mitigate the effects of noise in individual bands within this wavelength range, thus improving overall model accuracy.

Contrary to initial expectations, Shallow Water (Seagrass) bathymetric predictions were the least improved with the addition of spectral bands. This finding may be further confirmation that the spectral features of plant pigments are too subtle to make a meaningful difference in SDB models. However, it is noteworthy that depth predictions for Shallow Water (Seagrass) were already quite accurate in the 3-band model in this study, with an MAE value of only 0.95 m in the 1.4 m–11.3 m depth range. By comparison, Shallow Water (No Seagrass) predictions exhibited only a marginally lower MAE value of 0.77 m, indicating that there was little room for improvement for either of those pixel classes in this particular study.

The most significant improvements from the addition of hyperspectral bands occurred for Deep Water pixels (Table 2). It is possible that the spectral similarity between Deep Water and Shallow Water (Seagrass) pixels led to depths of Deep Water being underestimated in the baseline 3-band model because Deep Water pixels were “confused” with Shallow Water (Seagrass) pixels, and that the addition of hyperspectral bands eliminated or reduced the effect of such confusion. However, since the training dataset contained a high number of deep-water points, this explanation is questionable. The fact that hyperspectral bands contributed to reducing MAE at these greater depths nonetheless suggests that hyperspectral imagery has potential for improving multispectral SDB models at the threshold between optically shallow and optically deep waters. This aligns with previous findings that hyperspectral imagery can still provide meaningful bathymetric predictions up to 25 m, even where multispectral approaches typically fail [6], and that hyperspectral imagery outperforms multispectral imagery for SDB specifically in deep waters [30].

Table 2.

Depth-stratified MAE values for the 3-band and 24-band PRISMA models and the Landsat model.

Finally, a comparison between the accuracy of the optimized 24-band PRISMA model and the 4-band Landsat 8 model revealed that multispectral imagery outperformed hyperspectral imagery by 0.13 m, despite using a smaller number of spectral bands with lower spectral resolution. There are likely many and complex reasons for this; the two images were acquired on different days that may have had different atmospheric, sea-surface and water quality conditions, the sensors have different signal-noise ratios, image artifacts and geometric accuracy, and the two images were separately georeferenced. Additional similar comparisons would be required to determine whether the superior performance of Landsat 8 observed in this study is consistent across study areas and environmental and observation contexts; evidence to date is mixed concerning the relative performance for SDB of hyperspectral and multispectral sensors [30,31], and some evidence suggests that artificial reduction in spectral resolution via binning leads to improved performance due to noise reduction [16]. Nonetheless, our work contributes to what may be an emerging pattern suggesting that hyperspectral imagery is especially performant for SDB at relatively deeper depths. In our work, the 24-band PRISMA model outperformed the 3-band model the most for deeper depth intervals and slightly outperformed the Landsat model for waters deeper than 20 m (Table 2); a similar finding was observed in an SDB comparison between Sentinel-2 and PRISMA imagery [30]. These findings were consistent between the RF and SVM models, demonstrating that they are not unique to the specific structure of either model type.

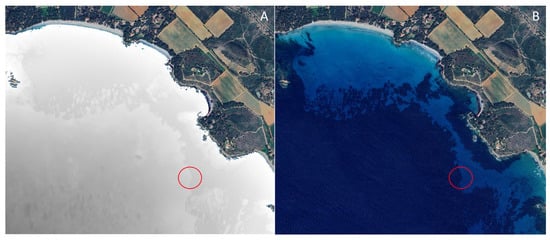

Important limitations in the study include constraints regarding the in situ data and study area. For example, since the in situ bathymetric dataset was recorded from 1972 to 1973, it does not reflect any subsequent bathymetric changes due to sediment transport or any changes in the extent of the P. oceanica meadows. Also, the horizontal accuracy of this data is subject to the quality control measures implemented by SHOM, and the vertical accuracy is constrained by the limitations of the echosounder technology. More recent airborne lidar bathymetry (ALB) data from the study area, acquired in 2015, are also available from SHOM [32]. However, visual inspection of this ALB data revealed a spatial pattern (Figure 10) in which Posidonia-covered areas (dark blue, Figure 10B) are shown as noticeably shallower (light gray, Figure 10A) than nearby unvegetated areas (vice versa), with depth differences of ~1.5 m–2 m between neighboring pixels. This suggests that the ALB system was unable to penetrate the dense seagrass canopy and effectively measured the location of the top of the canopy instead of the solid sandy/rocky seafloor. For the purposes of this study, we therefore considered the older acoustic data to be more suitable.

Figure 10.

Coincident spatial patterns observed in the 2015 ALB data available from SHOM (A), and the Sentinel-2 image (B). Dark areas in the Sentinel-2 image are covered in Posidonia meadows, and the ALB data shows these meadows as typically ~1.5 m–2 m shallower than neighboring unvegetated pixels. Note coincident transition between deep/shallow water (A) and bare/seagrass cover (B) from right to left across the red circles.

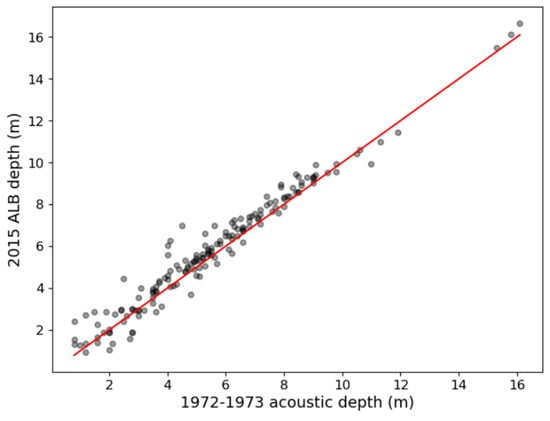

To assess the potential bathymetric changes experienced in the area since 1972–1973, we manually sampled 165 pixels that we visually determined to not contain seagrass, and compared their depths in the 1972–1973 acoustic data and the 2015 ALB data. Figure 11 shows a generally tight relationship with few outliers and a Mean Absolute Difference of 0.48 m between the two datasets. This suggests that any bathymetric changes since 1972–1973 are of a smaller magnitude (~0.5 m) than the errors produced by the limited canopy penetration of the ALB data shown in Figure 10 (~1.5 m–2.0 m).

Figure 11.

A comparison of 1972–1973 acoustic depth measurements and 2015 ALB depth measurements for 165 manually sampled pixels visually determined to not contain seagrass. A 1:1 line has been drawn in red.

This study was also limited to one PRISMA image of a study area with exceptionally clear waters; this may not be representative of other environments in which the effectiveness of SDB using hyperspectral imagery could be different. Neither is it necessarily representative of the potential of hyperspectral imagery for SDB more generally; for example, Xi et al. [31] found that EnMAP consistently outperformed both Sentinel-2 and Landsat 9 across several SDB models.

The results of this study provide insights into the potential of hyperspectral imagery to improve the accuracy of SDB models, suggesting that the addition of hyperspectral bands improves bathymetric predictions in coastal waters, principally by reducing prediction errors in deep water. These results contribute to the broader understanding of how hyperspectral data may be suited to address challenges in SDB applications. To build upon the findings of this study, future research should expand to different geographic regions, which would help determine whether the specific bands identified in this study, such as band 6 (446 nm), are universally useful in this methodology. Additionally, hyperspectral bands could be incorporated into SDB models utilizing multispectral imagery to assess whether a hybrid approach could benefit from the strengths of both data types, especially since PRISMA TOA radiances are very similar to Sentinel-2 data [33] allowing for easy integration of these two data sources that have complementary strengths, PRISMA providing high spectral resolution, and Sentinel-2 providing higher (10 m) spatial resolution.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that incorporating select hyperspectral bands into an SDB model can substantially improve SDB model accuracy in the Mediterranean Sea, compared to a baseline 3-band SDB model. The most substantial improvements were observed in deeper waters (25 m–30 m), where the addition of spectral bands decreased the MAE value by 1.51 m, suggesting that hyperspectral sensors may be especially suited for SDB at depths near the seafloor detection limit. Shallow-water depth prediction improved less, especially for seagrass-covered areas, where the MAE reduction was only 0.11 m from the baseline model to its best-performing iteration, suggesting that pigment-related spectral features are subtle relative to other sources of SDB error. Finally, despite improved accuracy with the addition of hyperspectral bands, even the best SDB model using PRISMA data was outperformed by a model using Landsat 8 data, despite Landsat 8 using fewer and broader bands. This suggests that, despite its lower spectral resolution, multispectral imagery may still be more effective for general coastal bathymetry mapping, while hyperspectral imagery is most valuable for improving depth retrieval towards the optically deep limit. Taken together, our results indicate that spaceborne hyperspectral data should be viewed as a complementary addition to, rather than a replacement for, multispectral SDB. Future work should test whether these patterns persist across other environments and sensors (e.g., EnMAP), and explore hybrid approaches that combine multispectral and hyperspectral observations to exploit the strengths of both.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J. and A.K.; methodology, R.J. and A.K.; validation, R.J.; formal analysis, R.J.; investigation, R.J.; data curation, R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J.; writing—review and editing, A.K.; visualization, R.J.; supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original remote sensing data from PRISMA and Landsat 8 presented in the study are available from https://prisma.asi.it (accessed on 30 September 2024) and https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 30 June 2025), respectively. The original acoustic data from SHOM are available from https://cdi.seadatanet.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Yulun Wu for providing technological assistance and Luke Copland for providing feedback throughout the writing process of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALB | Airborne Lidar Bathymetry |

| JM | Jeffries–Matusita |

| LAT | Lowest Astronomical Tide |

| L1 | Level 1 |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| OLI | Operational Land Imager |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PRISMA | PRecursore IperSpettrale della Missione Applicativa |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RGB | Red–Green–Blue |

| SDB | Satellite-Derived Bathymetry |

| SHOM | Service national d’Hydrographie et d’Océanographie de la Marine |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TOA | Top of Atmosphere |

| VNIR | Visible/Near-Infrared |

References

- Wölfl, A.-C.; Snaith, H.; Amirebrahimi, S.; Devey, C.W.; Dorschel, B.; Ferrini, V.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; Jakobsson, M.; Jencks, J.; Johnston, G.; et al. Seafloor Mapping—The Challenge of a Truly Global Ocean Bathymetry. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Najar, M.; Thoumyre, G.; Bergsma, E.W.J.; Almar, R.; Benshila, R.; Wilson, D.G. Satellite Derived Bathymetry Using Deep Learning. Mach. Learn. 2023, 112, 1107–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telesca, L.; Belluscio, A.; Criscoli, A.; Ardizzone, G.; Apostolaki, E.T.; Fraschetti, S.; Gristina, M.; Knittweis, L.; Martin, C.S.; Pergent, G.; et al. Seagrass Meadows (Posidonia oceanica) Distribution and Trajectories of Change. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornes, A.; Basterretxea, G.; Orfila, A.; Jordi, A.; Alvarez, A.; Tintore, J. Mapping Posidonia oceanica from IKONOS. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2006, 60, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaña-Borja, S.P.; Fernández-Mora, A.; Stumpf, R.P.; Navarro, G.; Caballero, I. Semi-Automated Bathymetry Using Sentinel-2 for Coastal Monitoring in the Western Mediterranean. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 120, 103328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizos, E. A Combined Machine Learning and Residual Analysis Approach for Improved Retrieval of Shallow Bathymetry from Hyperspectral Imagery and Sparse Ground Truth Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffione, R. Hyperspectral Optical Properties, Remote Sensing, and Underwater Visibility; Technical Report; Hydro-Optics, Biology, and Instrumentation Laboratories: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2001; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA627908.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Maritorena, S.; Morel, A.; Gentili, B. Diffuse reflectance of oceanic shallow waters: Influence of water depth and bottom albedo. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1994, 39, 1689–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanchí Golondrino, G.E.; Ospina Alarcón, M.A.; Saba, M. Vegetation Identification in Hyperspectral Images Using Distance/Correlation Metrics. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciraolo, G.; Cox, E.; La Loggia, G.; Maltese, A. The Classification of Submerged Vegetation Using Hyperspectral MIVIS Data. Ann. Geophys. 2006, 49, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peneva, E.; Griffith, J.A.; Carter, G.A. Seagrass Mapping in the Northern Gulf of Mexico Using Airborne Hyperspectral Imagery: A Comparison of Classification Methods. J. Coast. Res. 2008, 24, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, D.; Kabolizadeh, M.; Rangzan, K.; Zaheri Abdehvand, Z.; Balouei, F. New Methodology for Improved Bathymetry of Coastal Zones Based on Spaceborne Spectroscopy. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 3359–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Chu, S.; Chen, H.; Cheng, J.; Xu, R.; Qu, Z. Hyperspectral Satellite-Derived Bathymetry Considering Substrate Characteristics. Mar. Geod. 2025, 48, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Shan, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Dai, T.; Qu, G.; Xie, T.; Tong, C.; Naing, H.; Zhang, M. Partially Empirical Model-Based Water Depth Retrieval in Shallow Sea Using GF5-AHSI Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study on Meizhou Bay in Fujian Province, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghelli-Roman, A.; Goreac, A.; Mathieu, S.; Spigai, M.; Gouton, P. Comparison of Bathymetric Estimation Using Different Satellite Images in Coastal Sea Waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 5737–5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghelli, A.; Chami, M.; Guillaume, M.; Lei, M.; Dune, C. Retrieval of Benthic Habitat Abundance and Bathymetry from Hyperspectral Data (DESIS) in Shallow Waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 1467–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, R.C.; Dekker, A.G. Aquatic Optics: Basic Concepts for Understanding How Light Affects Seagrasses and Makes Them Measurable from Space. In Seagrasses: Biology, Ecologyand Conservation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 295–301. ISBN 978-1-4020-2942-4. [Google Scholar]

- Boudouresque, C.-F.; Bernard, G.; Bonhomme, P.; Charbonnel, E.; Diviacco, G.; Meinesz, A.; Pergent, G.; Pergent-Martini, C.; Ruitton, S.; Tunesi, L. Protection and Conservation of Posidonia oceanica Meadows; RAMOGE and RAC/SPA Publisher: Tunis, Tunisia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turley, C.M.; Bianchi, M.; Christaki, U.; Conan, P.; Harris, J.R.W.; Psarra, S.; Ruddy, G.; Stutt, E.D.; Tselepides, A.; Van Wambeke, F. Relationship between Primary Producers and Bacteria in an Oligotrophic Sea—The Mediterranean and Biogeochemical Implications. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Halstenbek 2000, 193, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA (Hyperspectral). Available online: https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/prisma-hyperspectral (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Vanhellemont, Q.; Ruddick, K. Atmospheric Correction of Metre-Scale Optical Satellite Data for Inland and Coastal Water Applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 216, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.7-2. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Dalponte, M.; Oerka, H.O. varSel: Sequential Forward Floating Selection Using Jeffries-Matusita Distance. R Package Version 0.2. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=varSel (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Service National d’Hydrographie et d’Océanographie de la Marine. Levé S197400800 [DATA SET]. SeaDataNet. 2022. Available online: https://services.data.shom.fr/geonetwork/srv/fre/catalog.search#/metadata/S197400800 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Mudiyanselage, S.; Abd-Elrahman, A.; Wilkinson, B.; Lecours, V. Satellite-Derived Bathymetry Using Machine Learning and Optimal Sentinel-2 Imagery in South-West Florida Coastal Waters. GIScience Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.D.; Noble, S.D. Spectrographic Measurement of Plant Pigments from 300 to 800 nm. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.; Carder, K.L. Effect of Spectral Band Numbers on the Retrieval of Water Column and Bottom Properties from Ocean Color Data. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, R.P.; Holderied, K.; Sinclair, M. Determination of Water Depth with High-Resolution Satellite Imagery over Variable Bottom Types. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2003, 48, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, D.; Gravey, M.; Price, T.D.; Nijland, W.; de Jong, S.M. Surveying Nearshore Bathymetry Using Multispectral and Hyperspectral Satellite Imagery and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Guo, G.; Gu, J. Band Weight-Optimized BiGRU Model for Large-Area Bathymetry Inversion Using Satellite Images. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service National d’Hydrographie et d’Océanographie de la Marine. Litto3D—PACA 2015 [Data Set]. 2015. Available online: https://diffusion.shom.fr/donnees/altimetrie-littorale/provence-alpes-cote-d-azur/litto3d-paca-2015.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Giardino, C.; Bresciani, M.; Braga, F.; Fabbretto, A.; Ghirardi, N.; Pepe, M.; Gianinetto, M.; Colombo, R.; Cogliati, S.; Ghebrehiwot, S.; et al. First Evaluation of PRISMA Level 1 Data for Water Applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.