Highlights

What are the main findings?

- YOLOv11-SAFM integrates a Spatially Adaptive Feature Modulation (SAFM) module, optimized MPDIoU bounding box regression loss, and a multi-scale training strategy, significantly improving small-scale landslide detection under complex mountainous conditions.

- Compared with Mask R-CNN and YOLOv8, the model shows notable improvements in precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP@0.5 for small landslide detection.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The SAFM module and MPDIoU loss enhance feature representation and localization accuracy, enabling robust and efficient automatic landslide detection.

- YOLOv11-SAFM has strong potential for application in geohazard monitoring and early warning systems in complex plateau environments.

Abstract

Landslide detection in mountainous regions remains highly challenging due to complex terrain conditions, heterogeneous surface textures, and the fragmented distribution of landslide features. To address these limitations, this study proposes an enhanced object detection framework named YOLOv11-SAFM, which integrates a Spatially Adaptive Feature Modulation (SAFM) module, an optimized MPDIoU-based bounding box regression loss, and a multi-scale training strategy. These improvements strengthen the model’s ability to detect small-scale landslides with blurred edges under complex geomorphic conditions. A high-resolution remote sensing dataset was constructed using imagery from Bijie and Zhaotong in southwest China including GF-2 optical imagery at 1 m resolution and Sentinel-2 data at 10 m resolution for model training and validation, while independent data from Zhenxiong County were used to assess generalization capability. Experimental results demonstrate that YOLOv11-SAFM achieves a precision of 95.05%, recall of 90.10%, F1-score of 92.51%, and mAP@0.5 of 95.30% on the independent test set of the Zhaotong–Bijie dataset for detecting small-scale landslides in rugged plateau environments. Compared with the widely used Mask R-CNN, the proposed model improves precision by 13.87% and mAP@0.5 by 15.7%; against the traditional YOLOv8, it increases recall by 27.0% and F1-score by 22.47%. YOLOv11-SAFM enables efficient and robust automatic landslide detection in complex mountainous terrains and shows strong potential for integration into operational geohazard monitoring and early warning systems.

1. Introduction

Landslides are a prevalent geohazard in Southwest China, with hotspots concentrated in the mountainous provinces of Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou, where steep relief, active tectonics, and recurrent heavy rainfall prevail [1]. Landslides represent a major hazard to human safety and property, while also compromising essential infrastructure, including water management, transportation, and communication systems. They lead to ecological degradation, thereby profoundly impacting regional sustainable development [2,3]. According to the report released by the Yunnan Provincial Department of Emergency Management, geological disasters in Yunnan Province in 2024 affected approximately 79,300 people and caused direct economic losses of about 1.517 billion yuan (source: https://yjglt.yn.gov.cn/html/2025/tjfx_0110/4029810.html, accessed on 10 January 2025). For instance, the landslide event in Liangshui Village, Zhenxiong County, which occurred suddenly on 22 January 2024, behind a low-lying village in winter, resulted in 44 fatalities [4]. This tragedy underscores the suddenness and high risk of landslides under unusual spatial-temporal conditions [5]. With the intensification of climate change and increasing human disturbances, landslide events have become more frequent, widespread, and abrupt, highlighting the urgent need for more effective identification methods and intelligent monitoring techniques [6]. This trend poses greater challenges and demands for the efficient identification and intelligent monitoring of geological hazards.

Visual interpretation is one of the earliest traditional methods used for landslide identification. Manual expert mapping exploits contrasts in texture, tone, and morphology observed in remote-sensing data and terrain information to separate landslides from surrounding areas [7,8]. Xue et al. [9] compiled an inventory of 3979 landslides in Zhenxiong County using high-resolution Google Earth imagery, which significantly supported the development of a regional landslide database and disaster risk assessment. However, this method is highly dependent on expert judgment, is time-consuming, and involves strong subjectivity, thereby limiting its applicability to large-scale, time-critical landslide detection.

The pixel-based feature thresholding method is one of the commonly used automated approaches for landslide identification. The pixel-based feature threshold method is one of the commonly used automated approaches for landslide identification. It determines landslide areas by analyzing differences in spectral, textural, and topographic features, and applying one or more predefined thresholds [10,11]. However, the threshold values are often region-specific and experience-driven, resulting in poor generalization performance. This limits the method’s applicability across diverse geomorphic settings and constrains its use in large-scale landslide detection. Machine learning approaches commonly draw on multi-dimensional inputs, including spectral, textural, and topographic information. They use classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) [12,13], Random Forests (RF) [14,15], and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [16,17] to distinguish landslide from non-landslide areas, offering high accuracy and moderate generalization capabilities. However, these methods rely heavily on manual feature engineering and selection, involve complex parameter tuning, and require substantial effort, which limits their applicability in large-scale and topographically complex regions.

In recent years, deep learning—particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)—has demonstrated strong feature learning capability and generalization performance in remote-sensing-based landslide identification [18,19,20,21,22]. With the evolution of network architectures, advanced U-Net variants, lightweight and efficient CNN models, and attention-enhanced networks have gradually become important research directions in geospatial object recognition. For example, Ghorbanzadeh et al. [23] constructed the Landslide4Sense dataset and systematically evaluated 11 mainstream segmentation models, highlighting the stable multi-scale representation and boundary delineation abilities of the U-Net family. Building on this work, Ghorbanzadeh et al. [24] proposed an integrated approach combining ResU-Net with rule-based OBIA for multi-temporal Sentinel-2 landslide detection, achieving more than a 22% improvement in mean intersection-over-union compared with ResU-Net alone. Meanwhile, efficient CNN architectures have also shown considerable promise. Li et al. [25] introduced FCADenseNet, which integrates surface deformation features and incorporates an attention mechanism, markedly improving landslide detection accuracy and demonstrating the potential of combining InSAR data with deep learning. Ji et al. [26] constructed a landslide dataset for Bijie City using high-resolution optical imagery and DEMs, and proposed a CNN model enhanced with spatial–channel attention. Their model achieved an F1-score of 96.62%, significantly improving detection accuracy under complex background conditions. Overall, although U-Net variants, efficient CNN architectures such as DenseNet, and attention-enhanced networks have substantially advanced landslide detection, notable challenges remain, including limited inference efficiency, susceptibility to missing small-scale landslides, and vulnerability to interference from complex mountainous backgrounds.

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series, as a representative one-stage object detection algorithm, offers advantages such as end-to-end training, fast inference speed, and a streamlined architecture [27,28,29,30]. By striking a strong speed–accuracy trade-off, YOLO is well suited to rapid landslide localization in remote-sensing imagery. It leverages multi-scale convolutional networks to extract morphological features of landslides (e.g., arcuate main scarps and accumulation bodies), spectral characteristics, and topographic context (e.g., steep-slope associations). During detection, predefined anchor boxes are used to match the aspect ratios of landslides, while classification loss (Focal Loss) and regression loss (CIoU) are jointly optimized to achieve accurate localization [31,32,33]. Ju et al. [34] employed YOLOv3 and RetinaNet to identify relict landslides, demonstrating the feasibility of using YOLO in complex background environments. This model readily accommodates the integration of attention mechanisms, thereby enhancing object detection performance [35,36,37]. Hou et al. [38] introduced YOLOX-Pro, an upgraded YOLOX variant that integrates Varifocal Loss and attention modules, substantially enhancing the identification of small and intricate landslides. Chen et al. [39] developed LSI-YOLOv8, a YOLOv8-based detector featuring a lightweight architecture and refined loss functions. The model outperforms existing mainstream approaches in both accuracy and detection speed. YOLOv11 [40] further incorporates novel architectural components such as C3k2 and C2PSA, achieving notable improvements in detection accuracy, boundary localization, and multi-task adaptability. It supports a wide range of functions including detection of objects, instance segmentation, pose inference, and oriented bounding box localization, facilitating use on diverse platforms, from lightweight edge devices to large-scale computing infrastructures. However, the original YOLO series still faces challenges in landslide detection, including missed detection of small targets, blurred boundaries, and significant interference from complex terrain backgrounds. These issues limit its practical applicability for automatic landslide identification in highland and mountainous regions. In high-resolution optical imagery of complex mountainous regions, small-scale landslides exhibit strong spectral heterogeneity, fragmented textures, and extremely small spatial scales. These characteristics can lead to feature loss during the downsampling process in convolutional neural networks, resulting in missed detections or unstable localization in traditional detectors. Moreover, landslide boundaries often present gradual or transitional characteristics, which conventional IoU-based loss functions struggle to capture accurately, causing localization deviations. To address these challenges, the proposed SAFM module, MPDIoU bounding box regression loss, and multi-scale training strategy are designed to enhance salient landslide features, improve localization accuracy, and effectively suppress complex background interference.

This study targets key obstacles in landslide identification across complex plateau mountainous terrains—namely small-target omission and boundary ambiguity. An improved YOLOv11-based landslide detection method is proposed, integrating attention mechanisms, multi-scale training strategies, and loss function optimization to boost detection accuracy, with pronounced gains for small-scale landslides and under complex background interference. The specific objectives are as follows:

- (1)

- To construct a high-quality landslide sample dataset by incorporating remote sensing imagery from the Zhaotong and Bijie regions, covering typical mountainous geomorphological features and providing abundant samples for model training and evaluation;

- (2)

- To embed a SAFM attention module that strengthens the model’s responsiveness to landslide spatial distributions, thereby improving detection in regions with subtle texture differences and high background complexity;

- (3)

- To employ a multi-scale training strategy and an optimized loss function, enhancing detection accuracy across varying landslide scales and improving boundary regression for finer detail capture.

2. Study Area and Datasets

2.1. Study Area

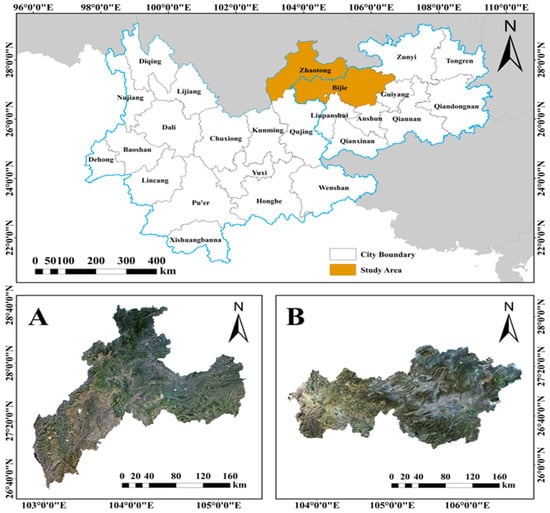

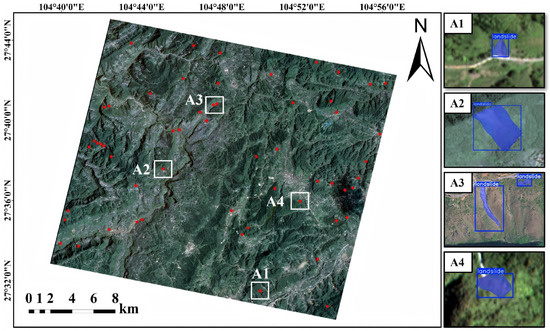

In this study, Zhenxiong County in Yunnan Province (26.34°N–28.41°N, 102.52°E–105.19°E) and Bijie City in Guizhou Province (26.35°N–27.77°N, 103.60°E–106.72°E) were chosen as the study areas (Figure 1). Both regions are located within the Wumengshan Tectonic Belt and represent typical highland mountainous terrain, characterized by pronounced topographic relief and complex geological conditions, making them high-risk areas for landslides and other geological hazards.

Figure 1.

GF-2 satellite imagery of the study areas. (A) Zhaotong region; (B) Bijie region. The images are shown as a composite (R: Band 3, G: Band 2, B: Band 1) with 4 m resolution.

Zhenxiong County experiences a highland monsoon climate, with 900–1200 mm of annual rainfall concentrated in June–September, typically as short, intense storms. The steep slopes, fractured lithology, and loose accumulated layers contribute to the frequent occurrence of landslides, debris flows, and collapses. By comparison, Bijie City experiences a subtropical humid monsoon climate, receiving 850–1100 mm of rainfall annually, most of it during May–October and often as prolonged heavy rain. The area is dominated by karst landforms with extensive underground cavities, and anthropogenic disturbances such as mining and reclamation further increase the risk of ground subsidence and landslides. Overall, the distinct topography, climate, and geological conditions of these two regions provide typical cases for landslide and related hazard studies, offering a reliable foundation for constructing high-quality landslide detection models. Moreover, disparities in regional hazard attributes bolster the model’s generalization performance and stability under complex mountainous conditions.

2.2. Datasets

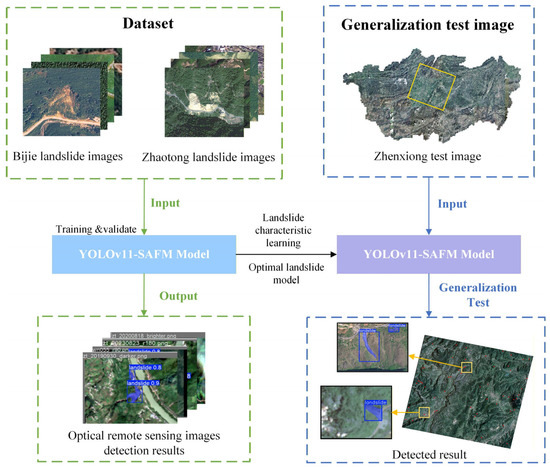

The optical imagery used for landslide detection includes the Bijie and Zhaotong landslide datasets, as well as imagery from a portion of the Zhenxiong region, which was excluded from the training phase, as shown in Figure 2. The Zhaotong landslide samples were derived from the 2020–2025 geological hazard data report of the Yunnan Geological Survey, and 272 landslide samples were manually delineated based on high-resolution GF-2 and Sentinel-2 optical imagery. The Bijie samples were sourced from publicly available remote-sensing data; in total, 770 images were extracted from TripleSat imagery [26]. To ensure consistency, all images were processed with atmospheric correction, geometric registration, cropping, and radiometric normalization.

Figure 2.

Landslide detection workflow based on the Bijie and Zhaotong datasets and the Zhenxiong test region.

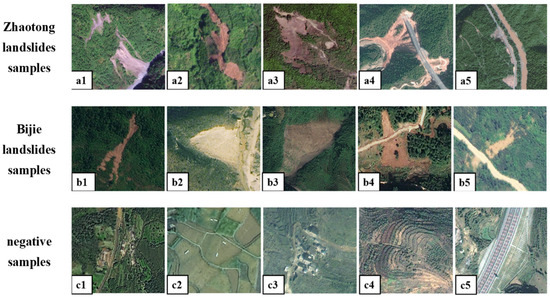

To improve robustness and generalization, we expanded the original landslide set to 2352 images via data augmentation—rotation, flipping, affine transformations, and color perturbations. In addition, 1000 non-landslide background images (e.g., mountainous areas, forests, and urban regions) were included as negative samples, resulting in a final training dataset comprising 3352 images. Images in the Bijie and Zhaotong datasets were uniformly cropped to 256 × 256 pixels and labeled in the YOLO format. Table 1 summarizes the dataset composition, and Figure 3 presents representative samples used in this study.

Table 1.

Dataset composition employed in this study.

Figure 3.

Sample images used in this study. (a1–a5) Landslide samples from Zhaotong, (b1–b5) Landslide samples from Bijie, (c1–c5) Non-landslide background samples.

The dataset was further divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 14:3:3 ratio, corresponding to 2346, 504, and 502 images, respectively, as detailed in Table 2. The training split served model fitting, the validation split informed model selection, and the test split was held out without further processing for performance assessment. The training set covers diverse geomorphological features and environmental interferences, serving as a robust basis for model training and evaluation.

Table 2.

Detailed Information on Dataset Partitioning.

Imagery from the Zhenxiong region was excluded from training and employed exclusively to assess the model’s generalization performance. These images were also cropped to 256 × 256 pixels with a 50% overlap to ensure comprehensive coverage.

3. Methods

Based on the baseline YOLOv11 architecture, this study develops YOLOv11-SAFM, an efficient detection method tailored for automatic landslide identification in mountainous regions. First, the basic architecture and advantages of the YOLOv11 model are briefly introduced. Subsequently, the model is optimized in three key aspects: (1) The loss function is redesigned to better handle the irregular shapes and uneven spatial distribution of landslides. This improves boundary regression accuracy, reduces missed detections, and enhances the recall rate in dense and small-scale landslide areas. (2) To improve detection under challenging backgrounds, a Spatially Adaptive Feature Modulation (SAFM) mechanism is employed to better capture essential features in landslide imagery with indistinct boundaries. (3) A multi-scale training approach is adopted to enhance the model’s capability in identifying landslides across different scales, particularly improving detection of small-scale targets.

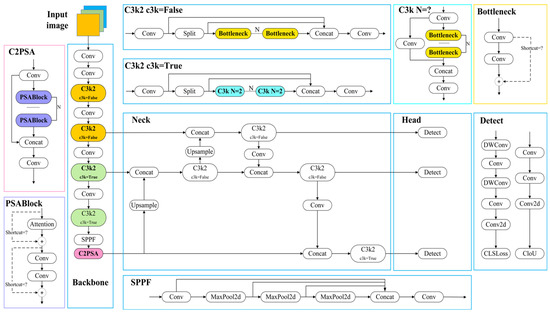

3.1. Basic YOLOv11 Model

YOLOv11, introduced by Ultralytics in 2024, as a further evolution of the YOLO series, it builds upon the anchor-free architecture and decoupled detection strategy of YOLOv8, introducing modular-level optimizations across multiple layers of the network to improve detection accuracy while maintaining inference efficiency. Its core improvements focus on the feature extraction backbone, integration of attention mechanisms, and the lightweight design of the detection head. An overview of the architecture is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Network architecture of YOLOv11.

In terms of network design, YOLOv11 incorporates the C3k2 module as an alternative to the C2f block in YOLOv8, aiming to strengthen feature extraction capacity. Derived from the Cross Stage Partial (CSP) structure [41], the C3k2 module controls cross-stage connections of feature channels through a tunable parameter. This configuration limits low-level interference with high-level semantics in the shallow stages and strengthens feature fusion in deeper stages, thereby improving the network’s overall representational capacity. Additionally, for attention mechanisms, YOLOv11 adds the C2PSA module after the original SPPF module [42], integrating a lightweight convolutional structure with multi-head parallel spatial attention. This enhancement improves the model’s capture of local spatial detail and contextual cues, yielding more accurate boundary and shape discrimination in mid- and high-level feature maps and better recognition of small landslide features. At the detection head, the model retains a decoupled classification–regression design and incorporates DWConv modules [43], sharply reducing parameters and computation. This enables real-time inference on resource-constrained devices and improves bounding-box localization accuracy.

In landslide remote sensing applications, the YOLOv11 model is trained primarily to distinguish landslide regions from non-landslide backgrounds, such as cropland and other land cover types. The model exploits its CNN architecture to learn deep spatial representations from remote-sensing imagery, which are then used for landslide classification and bounding-box localization. Morphologically, landslide areas often exhibit irregular boundaries (e.g., tear-shaped or fan-shaped), whereas croplands typically display regular geometric patterns. In terms of texture, landslides tend to exhibit pronounced heterogeneity and surface roughness, while cropland areas feature relatively uniform textures, often characterized by ridge lines formed by farming activities:

3.2. Improved YOLOv11 Model: YOLOv11-SAFM

3.2.1. Loss Function

Bounding Box Regression (BBR) plays a pivotal role in object detection and instance segmentation [44], as it enables the accurate localization of target objects within an image:

where Bp is the model’s estimated bounding box and Bgt is the reference ground-truth box.

However, in landslide instance segmentation tasks, the highly irregular geometries of landslide bodies, combined with the abundance of small-scale targets, present considerable challenges. Traditional IoU-based loss functions (e.g., GIoU [45], DIoU [46], CIoU [47]) often suffer from gradient vanishing and unstable optimization when dealing with large mismatches or high overlaps between the predicted bounding boxes and the true object locations. These issues result in slow convergence during the bounding box regression stage and lead to suboptimal performance, particularly in detecting small targets.

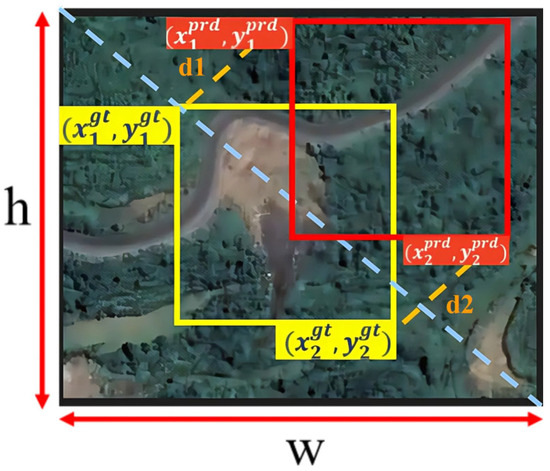

To address this issue, this study introduces MPDIoU (Multi-Perspective Decoupled IoU) as an improved regression loss function [48]. Based on the fundamental framework of IoU, MPDIoU further decouples the spatial geometric relationship between bounding boxes into multiple components—such as the distance between centers, angular direction, and overlapping or non-overlapping areas. Each component is evaluated to represent the geometric discrepancies between predicted and ground-truth boxes, as shown in Figure 5. Furthermore, MPDIoU simplifies the computational process and enhances the spatial localization accuracy of landslide targets. Its formulation is defined as follows:

Figure 5.

Illustration of the factors, showing the Euclidean distances (d1 and d2) between the predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes. The blue dashed line represents the diagonal scale reference of the predicted bounding box (), which is used to normalize the corner distance terms d1 and d2.

Specifically, and represent the squared Euclidean distances between the top−left and bottom−right corners of the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, respectively. The width (w) and height (h) of the predicted bounding box are employed to normalize the distance terms, ensuring that the resulting metric shares the same dimensionality as IoU. By simultaneously evaluating the spatial deviations of both diagonal corners, MPDIoU provides a more sensitive measure of misalignment and scale discrepancy between bounding boxes, thereby enhancing the stability of the regression process. To facilitate model optimization, the regression loss function based on MPDIoU is defined as follows:

Here, denotes the bounding box regression loss function based on MPDIoU. When the predicted and ground-truth boxes coincide exactly, MPDIoU reaches its maximum value of 1, and the loss function yields zero, indicating no localization error. Conversely, as the spatial overlap decreases and the positional deviation increases, the MPDIoU value drops and the corresponding loss increases, driving the model to iteratively improve bounding box localization during training.

In this study, MPDIoU is integrated into the YOLOv11 framework by replacing the original CIoU term in the bounding box regression branch, while the remaining loss components—including the BCE-based classification loss and the Distribution Focal Loss (DFL)—remain unchanged in both configuration and weighting. Compared to DIoU and CIoU, MPDIoU decouples spatial distances across multiple geometric channels, significantly enhancing sensitivity to boundary misalignment. This improves the stability and discriminative quality of gradient feedback, making MPDIoU particularly well-suited for detecting landslide targets in remote sensing imagery, where object shapes are complex and spatial distributions are uneven. As a result, it contributes to more accurate bounding box regression and improved overall detection performance.

3.2.2. Introduction of the Spatial Adaptive Feature Modulation (SAFM) Module

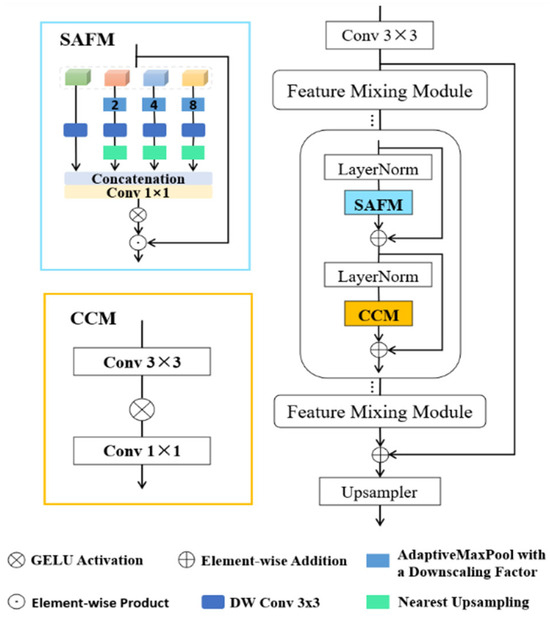

To improve the network’s ability to extract discriminative features and accurately represent small-scale landslides in complex backgrounds, this study incorporates the Spatially Adaptive Feature Modulation (SAFM) mechanism [49], originally proposed in the lightweight image super-resolution model SAFMN.

The network architecture comprises stacked Feature Mixing Modules (FMMs) together with a lightweight upsampling module. As illustrated in Figure 6, a 3 × 3 convolution is first applied to the low-resolution input image ILR to project it into the feature space, generating the initial shallow feature map F0. Subsequently, a stack of FMM blocks extracts deep features from F0, producing high-level feature representations for reconstructing high-resolution images. Each FMM comprises two key submodules: Spatially Adaptive Feature Modulation (SAFM) and the Convolutional Channel Mixer (CCM). The SAFM submodule performs long-range feature modeling and adaptively adjusts the weights across spatial positions based on image content, significantly enhancing the representation of critical regions—such as the edges and textures of small-scale landslides—in remote sensing imagery. The CCM is then employed to extract local contextual information and efficiently fuse features across the channel dimension, thus strengthening the capability to model complex multi-scale target semantics. This architectural design is well-suited for landslide detection tasks in remote sensing imagery, where target sizes vary significantly, boundaries are often ambiguous, and background interference is substantial. The feature mixing process can be formally described as:

Figure 6.

Network architecture of SAFM.

Then, LN(·) denotes the layer normalization operation, while X, Y and Z represent intermediate features at various stages of the network.

To better recover high-resolution details, we introduce a global residual path that facilitates learning of high-frequency content. Additionally, a lightweight upsampling module—consisting of a 3 × 3 convolution followed by a sub-pixel convolution—is used in the output stage to facilitate efficient and rapid image reconstruction. The overall network can be succinctly expressed as:

Here, ILR denotes the input image, represents the initial features extracted by the convolutional layer, denotes the Feature Mixing Module (FMM) composed of SAFM and CCM, and is the upsampling operator responsible for restoring the spatial resolution of the output image ISR. During training, we optimize the model with a composite loss that couples spatial- and frequency-domain terms, improving the perceptual quality of the reconstructed images. The loss takes the following form:

Here, IHR denotes the corresponding high-resolution ground-truth image, represents the L1 norm, and denotes the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), used to capture the image’s frequency-domain characteristics. The parameter is an empirically set weighting factor, fixed at 0.05 in our experiments. This loss function is designed to ensure accurate image reconstruction while effectively preserving structural details and texture information, making it well-suited for high-quality image restoration tasks.

3.2.3. Multi-Scale Training Strategy

To improve YOLOv11’s detection across varied target scales in complex terrain, we adopt a multi-scale training regimen during model training [50,51,52]. This strategy dynamically adjusts the input image resolution, exposing the model to samples of different scales during training. As a result, the network exhibits improved multi-scale feature representation and greater scale-invariant performance. Given that landslides in remote sensing imagery typically exhibit substantial scale variations, blurred boundaries, and diverse morphologies, multi-scale training effectively addresses the limitations of fixed-resolution training—namely, the perceptual blind spots for small targets and redundant feature extraction for large ones.

From a methodological perspective, multi-scale training introduces spatial-scale variation by randomly resizing input images within a range of 320 × 320 to 640 × 640 at each training iteration, allowing the network to learn feature representations under varying resolution conditions. This strategy encourages the model to continuously adapt its convolutional kernels to features of varying scales, thereby improving its capacity to resolve fine-edge details of small landslides while effectively representing the overall structure of larger features. YOLOv11 inherently employs a multi-level feature fusion architecture. With the integration of multi-scale input, feature maps from different receptive fields can collaboratively learn spatial representations of landslide targets at various scales, effectively improving both detection precision and recall.

Moreover, multi-scale training introduces a form of regularization by varying the input distribution during training. This breaks the model’s dependence on fixed feature scales, reduces the risk of overfitting, and enhances robustness and generalization in real-world complex scenarios.

4. Results

This section presents a comprehensive assessment and comparative analysis of the proposed enhanced YOLOv11 framework for landslide detection. The experiments cover overall detection performance, visualization-based analysis of detection results, and generalization capability assessment, aiming to systematically evaluate the performance and reliability of the enhanced approach.

4.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were run on a workstation with an Intel Core i7-12700 CPU, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB VRAM), using Python 3.10 with the PyTorch 12.8 framework.

During training, we adopted the cosine–annealing learning-rate scheduler with an initial warmup phase, following the official YOLO optimization strategy. This scheduler gradually reduces the learning rate throughout the training process, enabling stable convergence across 400 epochs. In addition, the data enhancement strategy adopts the Mosaic method. This approach randomly selects four training images, applies independent scaling and cropping operations, and then merges them into a single composite image. This process effectively increases sample diversity and enhances the model’s robustness to scale variations and complex background conditions.

To ensure consistency across all experiments, a unified set of hyperparameters was adopted throughout the training process. Before finalizing these settings, the official YOLOv11 configuration was used as the initialization baseline, and key optimizer parameters were further examined using the Ray Tune framework within a constrained search space to verify their stability and convergence on the landslide dataset. Subsequent validation-based adjustments were applied to obtain more reliable training performance. The finalized hyperparameter settings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Configuration of Experimental Training Process.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the recognition performance of the proposed YOLOv11-SAFM model, four standard metrics were employed: Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and mean Average Precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP@0.5). The evaluation metrics are computed as follows:

In these definitions, TP, FP, and FN represent the numbers of true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The F1 score, combining precision and recall harmonically, serves as an integrated measure of a model’s performance in capturing positive cases accurately and completely. A low F1-score typically indicates deficiencies in either precision or recall, which may result from poor recognition of true positives or a high number of false detections. Conversely, a high F1 score indicates strong performance in both precision and recall, reflecting well-balanced and overall optimized classification.

Here, APi denotes the Average Precision for the i class, and N represents the total number of classes in the training dataset (in this study, N = 1). mAP@0.5 is the mean Average Precision over all classes evaluated at an IoU threshold of 0.5. In this study, Mask AP is adopted as the primary metric for evaluating the segmentation accuracy of the YOLO-based instance segmentation model. This metric integrates segmentation precision under varying levels of localization strictness, offering a more thorough evaluation of the model’s detection performance over a range of IoU thresholds.

4.3. Experimental Results

4.3.1. Landslide Detection Results

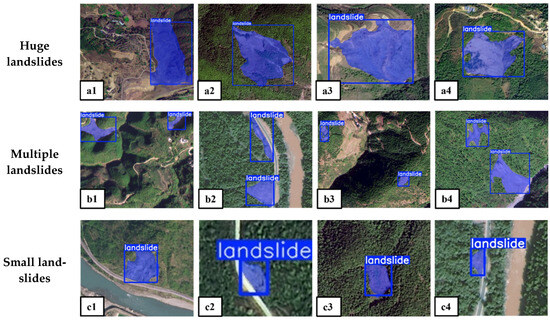

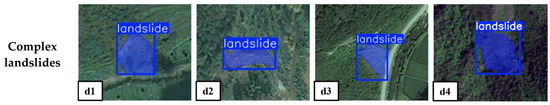

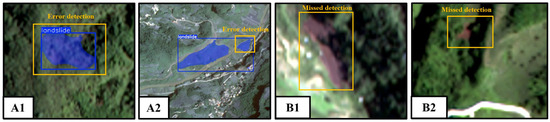

Representative detection results of the YOLOv11-SAFM model on the test set are illustrated in Figure 7 to assess its performance in real-world scenarios. In the figure, blue masks indicate the landslide boundaries automatically segmented by the model.

Figure 7.

Landslide detection examples using the YOLOv11-SAFM model on the test set. Blue masks indicate landslide boundaries automatically identified by the model. (a1–a4) Examples of large-scale landslides; (b1–b4) Scenarios with multiple co-existing landslides; (c1–c4) Detection results for small-scale landslides; (d1–d4) Landslides partially obscured by vegetation.

The results show that YOLOv11-SAFM can accurately extract landslide boundary contours. In scenarios with clearly defined single targets, the model produces compact and well-overlapping boundary predictions. Figure 7(b1–b4) depicts scenarios involving multiple landslide regions. In these complex cases—where targets appear simultaneously with considerable scale variation—YOLOv11-SAFM demonstrates strong spatial separation capability, clearly distinguishing the position and extent of each landslide body. Figure 7(c1–c4) showcases robust detection of small landslides, which frequently occur on mountain slopes or along roads. High localization accuracy in such cases is crucial for early landslide detection and effective risk mitigation. In addition, Figure 7(d1–d4) shows landslides in complex backgrounds, including areas covered by surface vegetation, where the surrounding environment appears visually similar. In such scenarios, the model must identify landslide features that are obscured by confounding visual elements. The detection results indicate that YOLOv11-SAFM effectively suppresses vegetation interference and correctly segments potential landslide regions, demonstrating strong background adaptability and robustness against noise.

In summary, YOLOv11-SAFM exhibits high accuracy and strong robustness in landslide detection tasks. It performs well not only in identifying large, clearly defined landslides but also in detecting small-scale targets and operating under complex background conditions.

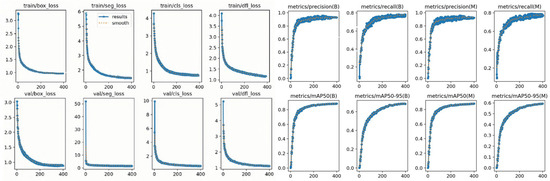

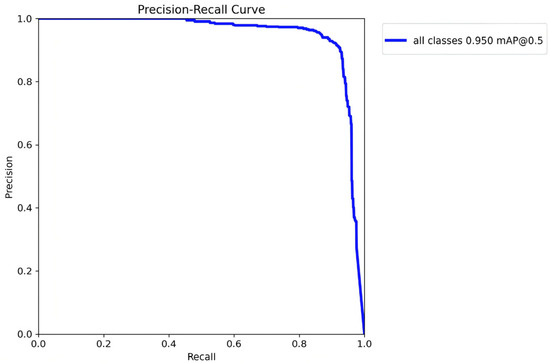

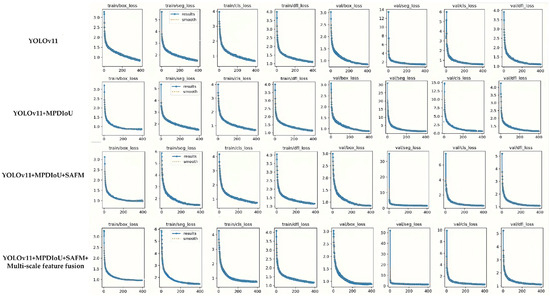

To evaluate the stability and convergence of the model, the training and validation loss curves (Figure 8) and the Precision–Recall curve (Figure 9) were analyzed. All loss components decrease smoothly throughout training, and the validation curves closely follow the training trends, indicating stable optimization without overfitting. The Precision–Recall curve exhibits a near-ideal shape, maintaining high precision across a wide range of recall levels, with an mAP@0.5 of approximately 0.95. These results confirm that the model achieves stable training dynamics and strong discriminative performance under different confidence thresholds.

Figure 8.

Training and validation loss curves and evaluation metrics of the YOLOv11-SAFM model.

Figure 9.

Precision–Recall curve of the proposed YOLOv11-SAFM model.

4.3.2. Comparing Different Detection Models

To validate the performance advantage of the proposed YOLOv11-SAFM model in landslide detection tasks, four representative object detection models were selected for comparison: Mask R-CNN [53], YOLOv8, YOLOv8-SAFM, YOLOv11, YOLOv12 and YOLOv11-SAFM. The evaluation metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and mAP@0.5. The experimental results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of Detection Performance Across Different Models.

As shown in the table, refining the loss, integrating attention, and adopting multi-scale training substantially improve overall detection performance. For example, in the YOLOv8 series, the integration of SAFM increased the F1-score from 70.04% to 85.45%, mAP@0.5 from 70.70% to 87.4%, and recall from 63.10% to 79.4%, respectively. These results demonstrate that the SAFM module strengthens the model’s perceptual modeling, thereby improving both detection accuracy and recall.

Similarly, YOLOv11 exhibited further improvements after incorporating the SAFM module and optimizing the loss function. The F1-score increased from 84.45% to 92.51%, recall improved from 77.90% to 90.10%, and mAP@0.5 reached 95.30%. These findings further validate the adaptability and generalizability of the SAFM module and MPDIoU loss function across different YOLO architectures.

To further enhance the completeness of the comparison, we evaluated YOLOv11-SAFM against YOLOv12 under identical training configurations. YOLOv12 achieved a precision of 88.60%, recall of 76.50%, and mAP@0.5 of 89.80%. While YOLOv12 provides strong baseline performance, YOLOv11-SAFM outperforms it with a higher recall of 90.10% and mAP@0.5 of 95.30%. Despite YOLOv12 introducing innovative architecture and attention mechanisms (such as the R-ELAN module and Flash Attention), landslide detection was not the primary focus of YOLOv12’s optimization. While these innovations are effective in other tasks, they did not yield the expected results when handling the blurry boundaries and small-scale targets typical of landslides. Additionally, YOLOv12’s increased computational load resulted in slower inference speeds, which negatively impacted its performance in landslide detection. Our results suggest that the performance improvement of YOLOv11-SAFM is primarily attributed to the integration of the SAFM module and MPDIoU loss, rather than differences between YOLO architecture versions.

Notably, the improvement in recall attributed to the SAFM module and MPDIoU loss function is particularly significant, with increases of 16.30% and 12.20% observed in YOLOv8 and YOLOv11, respectively. This demonstrates the module’s strong effectiveness in enhancing the model’s capability to identify landslide regions, especially under complex backgrounds or in the presence of small-scale targets.

As indicated by Table 4, Mask R-CNN underperforms YOLOv11-SAFM across all evaluation metrics. Moreover, the F1-score, calculated as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a balanced measure of the model’s overall detection performance. The marked gains in F1 score after integrating SAFM indicate that the module boosts precision while sustaining high recall, yielding a more balanced and stable detection performance.

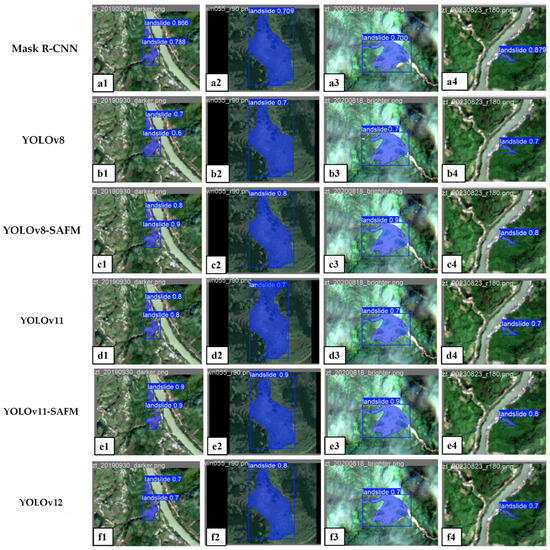

Under the same testing scenario (Figure 10), we conducted a side-by-side comparison of Mask R-CNN, YOLOv8, YOLOv8-SAFM, YOLOv11, YOLOv12 and YOLOv11-SAFM. The results show that Mask R-CNN, affected by its two-stage framework and feature sampling, tends to produce coarse masks, jagged boundaries, and partial misses in the presence of complex textures and shadow interference. YOLOv8 exhibits insufficient sensitivity to small-scale landslides, frequently resulting in partial or missed detections. With the introduction of SAFM, YOLOv8-SAFM improves the representation of fine-grained edges and weak-texture regions, resulting in better boundary continuity and small-object recognition. YOLOv11 achieves higher localization accuracy than YOLOv8, yet still presents edge omissions and over-segmentation in some cases. Although YOLOv12 provides a strong baseline, it still tends to incorrectly include nearby buildings as part of the landslide targets when dealing with small and densely distributed landslides, and its delineation of landslide boundaries is not sufficiently complete. By contrast, YOLOv11-SAFM delivers the best performance under similar conditions, more fully capturing fine-grained edge cues and effectively suppressing background interference, thereby demonstrating stronger adaptability and robustness while balancing precision and recall.

Figure 10.

Comparison of detection results among different models on the test set. Blue masks indicate landslide regions automatically detected by the models, and the overlaid text denotes the class label and confidence score. The confidence score reflects the probability that a detected object is indeed a landslide, with higher values indicating higher certainty. (a1–a4) Mask R-CNN, (b1–b4) YOLOv8, (c1–c4) YOLOv8-SAFM, (d1–d4) YOLOv11, (e1–e4) YOLOv11-SAFM, (f1–f4) YOLOv12.

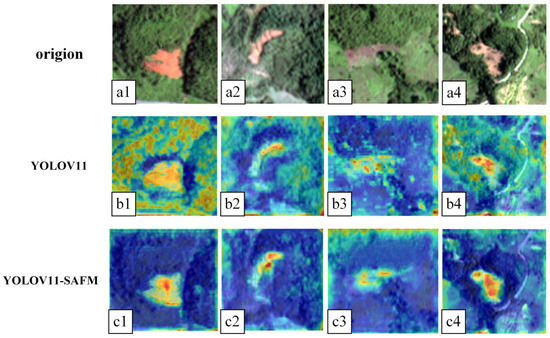

4.3.3. Heatmap Visualization Analysis

To further evaluate the contribution of the SAFM module to spatial feature adaptation and its influence on the model’s internal feature perception, Grad-CAM attribution maps were generated for both YOLOv11 and YOLOv11-SAFM. As shown in Figure 11, the baseline YOLOv11 presents relatively dispersed activation regions and is easily affected by background textures such as shadows and vegetation, making it difficult to consistently focus on landslide structures in complex environments.

Figure 11.

Figure X. Grad-CAM visualizations of YOLOv11 and YOLOv11-SAFM. (a1–a4) Original images. (b1–b4) YOLOv11 heatmaps. (c1–c4) YOLOv11-SAFM heatmaps with more focused activation on landslide features. The color scale represents the intensity of activation, with warmer colors (yellow to red) indicating higher activation values and cooler colors (blue to green) representing lower activation values, highlighting areas with more significant model attention on landslide features.

In contrast, YOLOv11-SAFM produces more concentrated and semantically coherent activation patterns, with attention directed primarily toward the key structural components of the landslide while effectively suppressing background interference. These visual comparisons demonstrate that the SAFM module substantially enhances the model’s spatial feature representation capability, enabling more accurate perception of landslide features and thereby improving overall detection robustness.

4.3.4. Landslide Detection Results in Zhaotong

To evaluate the generalization capability of the YOLOv11-SAFM model in previously unseen geographic regions, this study conducted automatic landslide detection in Zhenxiong County, Yunnan Province, which was entirely excluded from the model’s training process. As shown in Figure 12, the detection results clearly illustrate the spatial distribution pattern of the identified landslides, with a total of 55 landslide instances detected. Overall, the model exhibited strong detection performance in this unfamiliar region, with only a few instances of missed or error detections. The yellow and blue markers indicate missed detections and error detections, respectively. As shown in Figure 13, some landslides marked by yellow points were missed due to the occlusion of key features by dense vegetation shadows. Meanwhile, the areas marked by blue points represent bare surfaces heavily eroded by rainfall, which were incorrectly detected as landslides due to their high visual similarity to actual landslide features. To address these challenges caused by specific scene complexities—such as vegetation-induced shadowing and erosion-related interference—additional training samples featuring similar occlusion conditions and easily confused erosional surfaces were incorporated into subsequent model training for targeted enhancement. In summary, this out-of-region generalization test demonstrates the model’s effective transferability and its promising potential for real-world landslide detection across diverse geographic environments.

Figure 12.

Example of landslide detection using the YOLOv11-SAFM model in a selected area of Zhenxiong County. The blue masks represent the landslide boundaries automatically identified by the model. Red, blue, and yellow dots indicate landslide, error detection, and missed detection, respectively.

Figure 13.

Examples of error detections and missed detections in landslide recognition. (A1,A2) present false positive cases, where (B1) corresponds to erosion landforms and (B2) shows bare soil misidentified as landslides. (B1,B2) illustrate missed detections caused by dense vegetation shadows obscuring key features.

5. Discussion

This study proposes an improved landslide detection framework built upon the YOLOv11 architecture, integrating a SAFM module, a refined loss function, and a multi-scale training scheme. Generalization experiments were conducted using high-resolution remote sensing data from Zhenxiong County, Zhaotong, Yunnan Province. Experimental evaluation indicates that the proposed model markedly enhances detection performance, improves the identification of small-scale landslides, and achieves more accurate boundary localization. To offer a thorough evaluation of the model’s performance and practical utility, the subsequent section analyzes the key findings from multiple perspectives.

5.1. Module Effectiveness Analysis

To further assess the individual contributions of each proposed component to landslide detection performance, we conducted component-wise ablation experiments using the YOLOv11 framework. Specifically, three improved models were constructed by sequentially integrating the MPDIoU bounding box regression loss, the SAFM spatial attention module, and the multi-scale feature fusion strategy. These variants were evaluated on a standardized landslide remote sensing dataset. The detection performance of each model, in terms of Precision, Recall, AP@0.5, and F1-score, is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation of Detection Performance Across Model Variants.

According to Table 5, the baseline YOLOv11 exhibited reliable detection performance, with Precision, Recall, AP@0.5, and F1-score of 92.21%, 77.90%, 88.08%, and 84.45%, respectively. Replacing the original loss with the proposed MPDIoU-based bounding-box regression loss markedly improves localization, with pronounced gains on small landslide instances. Specifically, Recall increased to 83.21%, AP@0.5 rose to 90.71%, and F1-score reached 87.51%. These results confirm that the MPDIoU loss effectively enhances localization accuracy while reducing missed detections.

Building on this improvement, incorporating the SAFM attention mechanism further strengthens the model’s discrimination of landslide regions under complex background conditions. As a result, Recall and F1-score increase to 89.61% and 92.60%, respectively, while mAP@0.5 improves to 94.90%. These findings indicate that the attention mechanism enables the model to focus on prominent landslide features while mitigating interference from background noise.

Finally, the adoption of a multi-scale feature fusion strategy leads to further performance gains. The final model, YOLOv11 enhanced with MPDIoU, SAFM, and multi-scale fusion, achieves the best results across all evaluation metrics, with Recall reaching 90.10%, F1-score attaining 92.51%, and mAP@0.5 peaking at 95.30%.

In conclusion, the ablation analysis demonstrates that the introduced enhancements significantly contribute to improved detection accuracy. The synergy among the introduced modules is evident, and the final YOLOv11-SAFM model exhibits strong generalization capability and adaptability to complex background conditions, rendering it highly applicable for real-world landslide detection in mountainous regions.

To further investigate the influence of each module on the training dynamics, we compared the training and validation loss curves of the four model configurations, as illustrated in Figure 14. The results show that the MPDIoU loss accelerates the convergence of the regression branch and effectively reduces loss fluctuations during the early stages of training. With the incorporation of the SAFM module, the segmentation loss exhibits a more stable downward trend, indicating that SAFM enhances spatial feature representation and contributes to a more stable optimization process. After integrating the multi-scale feature fusion structure, the overall loss curves become smoother, and the convergence trends of both the training and validation phases become more consistent. Overall, these components not only improve the final detection performance but also positively influence optimization efficiency, convergence stability, and the characteristics of the loss landscape throughout the training process.

Figure 14.

Training and validation loss curves of the four compared models.

5.2. Limitations and Future Challenges

While the improved model shows strong overall detection capability, its effectiveness is still constrained under real-world conditions. On one hand, optical remote sensing imagery is inherently susceptible to interference from terrain shadows, cloud cover, and vegetation, which often leads to boundary ambiguity or missed detections in complex terrains such as mountainous gorges. In addition, distinguishing natural landslides from human-induced excavated slopes remains challenging. Although YOLOv11-SAFM can leverage morphological and textural cues—such as arcuate scarps, heterogeneous roughness patterns, and irregular deposition zones—to differentiate the two to some extent, engineered cuts and quarry slopes often exhibit spectral and geometric characteristics highly similar to true landslides in high-resolution optical imagery. As a result, misclassifications may still occur under visually ambiguous or background-complex conditions. This reflects an inherent limitation of optical remote sensing in mountainous environments, where even expert interpreters may encounter difficulty achieving stable and reliable discrimination. Future work will therefore expand the diversity of engineered-slope samples and explore the integration of LiDAR-derived topographic metrics or SAR-based deformation features to enhance the model’s ability to separate natural landslides from human-modified surfaces.

To improve the model’s applicability and intelligence, future work may explore the following avenues. First, integrating multi-source remote sensing data—such as radar, thermal infrared, and LiDAR—with optical imagery could improve multi-perspective perception and all-weather detection capabilities. Second, expanding the model’s ability to classify different landslide types would allow for more refined disaster identification and severity assessment. Furthermore, incorporating landslide detection with InSAR-based deformation monitoring and meteorological early warning systems could facilitate the development of an integrated “detection–early warning–response” framework for intelligent geohazard monitoring, advancing landslide remote sensing applications toward greater operational viability and intelligence.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces YOLOv11-SAFM, an enhanced deep learning framework for automated landslide detection in complex mountainous environments. The model integrates a Spatially Adaptive Feature Modulation (SAFM) attention mechanism, an optimized MPDIoU bounding box regression loss, and a multi-scale training strategy, improving its ability to identify small-scale, blurred-edge, and heterogeneous landslide features. High-resolution remote sensing datasets from Bijie and Zhaotong in southwest China were used for training and validation, while independent imagery from Zhenxiong County evaluated generalization performance.

YOLOv11-SAFM demonstrates robust detection performance in rugged plateau terrains, achieving 95.05% precision, 90.10% recall, 92.51% F1-score, and 95.30% mAP@0.5 for small-scale landslides. Compared with Mask R-CNN, precision and mAP@0.5 increased by 13.87% and 15.7%, respectively; relative to traditional YOLOv8, recall and F1-score improved by 27.0% and 22.47%. The results indicate that the framework achieves superior precision, recall, and resilience under challenging background conditions.

In summary, YOLOv11-SAFM offers an efficient, robust, and generalizable framework for automated landslide detection. By combining fine-resolution satellite imagery with advanced deep learning approaches, the model substantially enhances the speed and accuracy of geohazard monitoring, providing a reliable technical foundation for landslide risk assessment, early warning, and emergency management. Moreover, the framework exhibits strong scalability and can be integrated with multi-source remote sensing data, InSAR-based deformation monitoring, and intelligent early warning systems, facilitating the development of comprehensive and smart landslide monitoring strategies in mountainous regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and B.-H.T.; methodology, C.Z.; software, C.Z. and F.C.; validation, C.Z., B.-H.T. and M.L.; formal analysis, C.Z.; investigation, C.Z.; resources, B.-H.T. and D.F.; data curation, C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.-H.T. and M.L.; visualization, F.C.; supervision, B.-H.T.; project administration, B.-H.T.; funding acquisition, B.-H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 42230109, in part by the Yunling Scholar Project of the “Xingdian Talent Support Program” of Yunnan Province under Grant 41961053, in part by the Yunnan International Joint Laboratory for Integrated Sky-Ground Intelligent Monitoring of Mountain Hazards under Grant 202403AP140002, and in part by the Platform Construction Project of High Level Talent in the Kunming University of Science and Technology under Grant 141120210012, and in part by the Ministry-Provincial Cooperation Pilot Project under Grant 2023ZRBSHZ048.

Data Availability Statement

The Bijie data used in this study were obtained from publicly available remote sensing datasets. The landslide samples in Zhenxiong County, Yunnan Province, were collected and annotated based on high-resolution optical imagery from the China High-resolution Earth Observation System (GF-2). The processed data and model results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the China National Space Administration for providing access to the GF-2 high-resolution satellite imagery and to the European Space Agency for making the Sentinel-2 data publicly available. The authors also thank Kunming University of Science and Technology for the technical and computational support provided during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.; Song, D.Q.; Du, Y.M.; Dong, L.H. Investigation on the spatial distribution of landslides in Sichuan Province, southwest China. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2232085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Gong, W.P.; Jaboyedoff, M.; Chen, J.; Derron, M.H.; Zhao, F.M. Landslide Identification in UAV Images Through Recognition of Landslide Boundaries and Ground Surface Cracks. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Pang, H.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Fan, L.; Wei, S.J.; Yuan, Z.W.; Fang, Y.Q. Applications and Advancements of Spaceborne InSAR in Landslide Monitoring and Susceptibility Mapping: A Systematic Review. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Chen, N.S.; Huang, D.X.; Wang, Y.K. A medium-sized landslide leads to a large disaster in Zhenxiong, Yunnan, China: Characteristics, mechanism and motion process. Landslides 2025, 22, 3365–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Gao, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Dou, J.; Niu, R.Q.; Plaza, A.J. BisDeNet: A new lightweight deep learning-based framework for efficient landslide detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 3648–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.Y.; Gao, O.Y.; Lu, W.J.; Liu, W.; Lai, T. Reg-SA-UNet++: A lightweight landslide detection network based on single-temporal images captured postlandslide. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 9746–9759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.P.; Hasegawa, H.; Fujiwara, S.; Tabita, M.; Koarai, M.; Une, H.; Iwahashi, J. Interpretation of landslide distribution triggered by the 2005 northern Pakistan earthquake using SPOT 5 imagery. Landslides 2007, 4, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Q.; Li, W.L. Analysis of the geo-hazards triggered by the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2009, 68, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.W.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Feng, L.Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.R.; Zhu, D.J.; Sun, J.J.; Wang, P.; Li, L.; et al. Inventory of landslide relics in Zhenxiong County based on human-machine interactive visual interpretation, Yunnan Province, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 12, 1518377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshchinsky, B.A.; Olsen, M.J.; Tanyu, B.F. Contour Connection Method for automated identification and classification of landslide deposits. Comput. Geosci. 2015, 74, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, T.R.; Kerle, N.; Jetten, V.; van Westen, C.J.; Kumar, K.V. Characterising spectral, spatial and morphometric properties of landslides for semi-automatic detection using object-oriented methods. Geomorphology 2010, 116, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.H.; Hu, G.D. Time Series Prediction of Landslide Displacement Using SVM Model: Application to Baishuihe Landslide in Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 239–240, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yin, K.L.; Zhou, C.; Ahmed, B. Establishment of Landslide Groundwater Level Prediction Model Based on GA-SVM and Influencing Factor Analysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stumpf, A.; Kerle, N. Object-oriented mapping of landslides using Random Forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 2564–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.X.; Wu, X.L.; Niu, R.Q.; Yang, K.; Zhao, L.R. The assessment of landslide susceptibility mapping using random forest and decision tree methods in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezaal, M.R.; Pradhan, B. An improved algorithm for identifying shallow and deep-seated landslides in dense tropical forest from airborne laser scanning data. Catena 2018, 167, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsevski, P.V.; Brown, M.K.; Panter, K.; Onasch, C.M.; Simic, A.; Snyder, J. Landslide detection and susceptibility mapping using LiDAR and an artificial neural network approach: A case study in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park, Ohio. Landslides 2016, 13, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Ma, L.; Fu, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Tang, M.; Li, N.W. Landslides Information Extraction Using Object-Oriented Image Analysis Paradigm Based on Deep Learning and Transfer Learning. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, T.; Niu, R.Q.; Plaza, A. Landslide Detection Mapping Employing CNN, ResNet, and DenseNet in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 11417–11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Blaschke, T.; Gholamnia, K.; Meena, S.R.; Tiede, D.; Aryal, J. Evaluation of Different Machine Learning Methods and Deep-Learning Convolutional Neural Networks for Landslide Detection. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.L.; Wang, Y.; Si, T.Z.; Ullah, K.; Han, W.; Wang, L.Z. MFFSP: Multi-scale feature fusion scene parsing network for landslides detection based on high-resolution satellite images. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, M.Z.; Li, D.F.; Jia, J.R.; Yang, A.Q.; Zheng, W.F.; Yin, L.R. Conv-trans dual network for landslide detection of multi-channel optical remote sensing images. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1182145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Xu, Y.H.; Ghamisi, P.; Kopp, M.; Kreil, D. Landslide4Sense: Reference Benchmark Data and Deep Learning Models for Landslide Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5633017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Gholamnia, K.; Ghamisi, P. The application of ResU-net and OBIA for landslide detection from multi-temporal Sentinel-2 images. Big Earth Data 2023, 7, 961–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Shi, A.C.; Li, X.R.; Dou, J.; Li, S.J.; Chen, T.X.; Chen, T. Deep Learning-Based Landslide Recognition Incorporating Deformation Characteristics. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.P.; Yu, D.W.; Shen, C.Y.; Li, W.L.; Xu, Q. Landslide detection from an open satellite imagery and digital elevation model dataset using attention boosted convolutional neural networks. Landslides 2020, 17, 1337–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, Y.; Challa, M. YOLOv8: Advancements and innovations in object detection. In Smart Trends in Computing and Communications. SmartCom 2024; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Senjyu, T., So–In, C., Joshi, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 946, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, J. A Method for Constructing a Loss Function for Multi-Scale Object Detection Networks. Sensors 2025, 25, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putra, H.A.A.; Arymurthy, A.M.; Chahyati, D. Enhancing Bounding Box Regression for Object Detection: Dimensional Angle Precision IoU-Loss. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 81029–81047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.H.; Fang, Q.; Xu, X. Joint Optimization Loss Function for Tiny Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.Z.; Xu, Q.; Jin, S.C.; Li, W.L.; Su, Y.J.; Dong, X.J.; Guo, Q.H. Loess Landslide Detection Using Object Detection Algorithms in Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhao, K.; Liu, X.C.; Mu, J.Q.; Zhao, X.P. Partial convolution-simple attention mechanism-SegFormer: An accurate and robust model for landslide identification. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 151, 110612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, N.; Vaidya, H.; Satyam, N.; Tang, X.C.; Singh, S.; Meena, S.R. A Novel Multi-Layer Attention Boosted YOLOv10 Network for Landslide Mapping Using Remote Sensing Data. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, 70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Tang, R.; Pu, C.H.; He, Y.S. Condition monitoring of heterogeneous landslide deformation in spatio-temporal domain using advanced graph attention network. Geom. Nat. Hazards Risk 2025, 16, 2519429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.Y.; Chen, M.X.; Tie, Y.B.; Li, W.L. A Universal Landslide Detection Method in Optical Remote Sensing Images Based on Improved YOLOX. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Deng, X.P. LSI-YOLOv8: An Improved Rapid and High Accuracy Landslide Identification Model Based on YOLOv8 From Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 97739–97751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, J.W.; Yeh, I.H. CSPNet: A New Backbone that can Enhance Learning Capability of CNN. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ren, S.Q.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Hwang, S.; Cho, H. BiRD: Bi-Directional Input Reuse Dataflow for Enhancing Depthwise Convolution Performance on Systolic Arrays. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2024, 73, 2708–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.L.; Pang, Y.W.; Han, J.G.; Li, X.L. Hierarchical Regression and Classification for Accurate Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 2425–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.L.; Zhang, N.N.; Wang, W. Smooth GIoU Loss for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Shu, X.; Fan, N.N.; Chang, X.J.; Liu, Q.; He, Z.Y. Accurate bounding-box regression with distance-IoU loss for visual tracking. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2022, 83, 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.H.; Wang, P.; Ren, D.W.; Liu, W.; Ye, R.G.; Hu, Q.H.; Zuo, W.M. Enhancing Geometric Factors in Model Learning and Inference for Object Detection and Instance Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 8574–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.Y.; Shen, Y.J. Underwater Target Detection Based on Improved YOLOv7 Algorithm with BiFusion Neck Structure and MPDIoU Loss Function. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 105165–105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Dong, J.; Tang, J.; Pan, J. Spatially-Adaptive Feature Modulation for Efficient Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 13144–13153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Liu, B.; Ren, Y.X.; Jiang, P. Unsupervised learning inversion of seismic velocity models based on a multi-scale strategy. Geophys. Prospect. 2025, 73, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.L.; Ou, J.; Zhong, J.H.; Jiang, T.X.; Ma, T.S. Multi-scale feedback residual network for image super-resolution. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Zhu, X.B.; Qin, J.Y.; Xu, Y.; Cesar, R.M., Jr.; Yin, X.C. Multi-Scale Texture Fusion for Reference-Based Image Super-Resolution: New Dataset and Solution. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2025, 133, 6971–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xi, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, M.; Yang, L.; Xie, D. Landslide Detection and Segmentation Using Mask R-CNN with Simulated Hard Samples. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan. Univ. 2023, 48, 1931–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.