An Algorithm for Extracting Bathymetry from ICESat-2 Data That Employs Structure and Density Using Concentric Ellipses

Highlights

- High accuracy was achieved from a novel algorithm for extracting bathymetric photon events (PEs) from ICESat-2 data using PE spatial structure as well as more conventional density.

- Across three global datasets the algorithm appears to be sufficiently robust to not require local tuning.

- The high accuracy identification of bathymetric PEs may improve the accuracy of satellite derived bathymetry that uses the bathymetric PEs for training.

- The method’s robustness may provide improved efficiency in reducing the amount of manual effort required to identify bathymetric PEs in ICESat-2 tracks.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

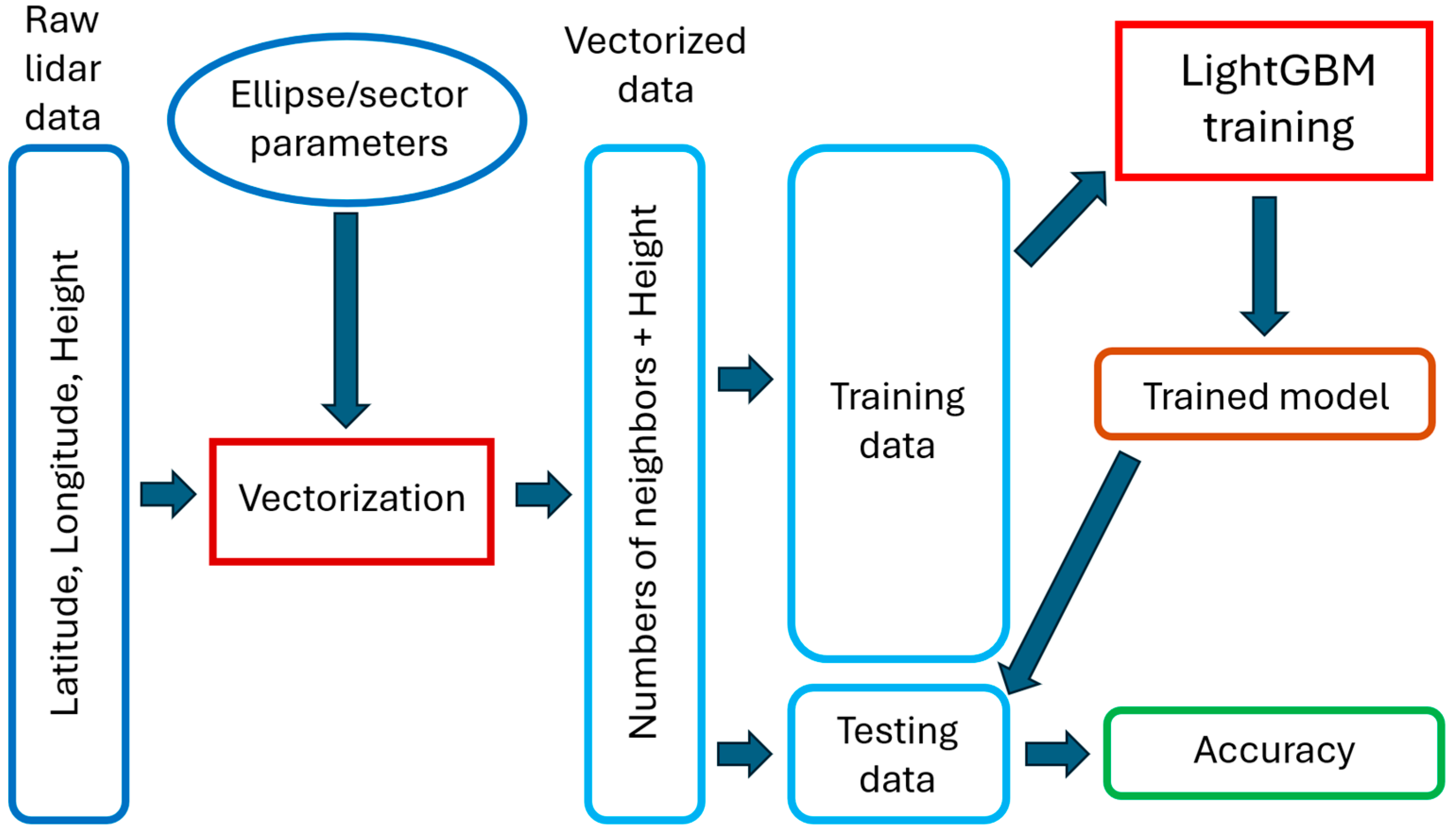

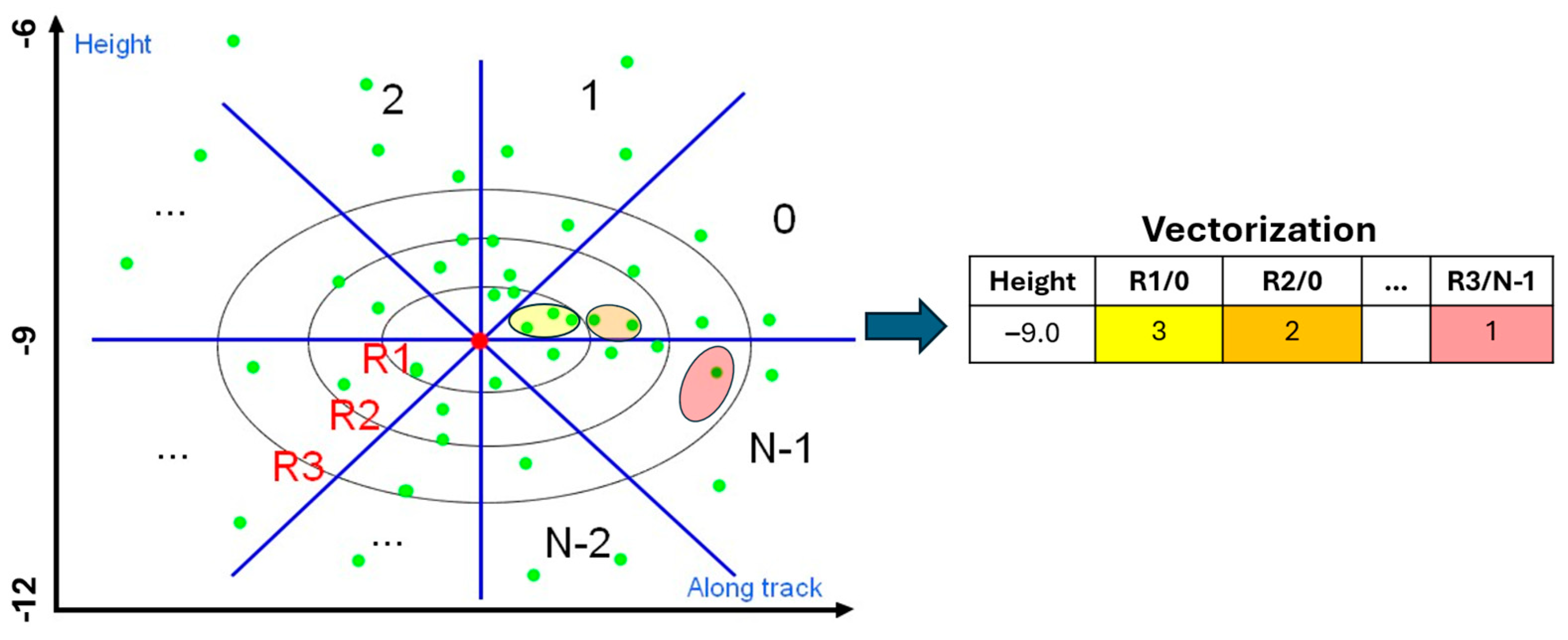

2.1. Algorithm and Description

2.2. Data and Algorithm Analysis

- Five ICESat-2 “granules” (1/14 of an orbit) recorded in 2018 around the Florida Keys (United States) region centered approximately on 24.60°N/81.50°W (lat/lon).

- A publicly available globally distributed dataset stored in the Scholars Archive at the Oregon State University [30].

2.3. Influence of Model Parameters on Classification Accuracy

2.4. Potential for Elimination of the Need for Manually Extracted Training Data

3. Results

3.1. Algorithm Performance on Real Datasets

3.2. Evaluation of Accuracy Relative to Tuning/Hyper-Parameters

3.3. Using Synthetic Data for Model Training

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markus, T.; Neumann, T.; Martino, A.; Abdalati, W.; Brunt, K.; Csatho, B.; Farrell, S.; Fricker, H.; Gardner, A.; Harding, D.; et al. The Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2): Science requirements, concept, and implementation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 190, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, C.; Magruder, L.; Neuenschwander, A.; Forfinski-Sarkozi, N.; Alonzo, M.; Jasinski, M. Validation of ICESat-2 ATLAS bathymetry and analysis of ATLAS’s bathymetric mapping performance. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafarczyk, A.; Tos, C. The use of green laser in LiDAR bathymetry: State of the art and recent advancements. Sensors 2023, 23, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, S.; Yang, Y.; Herzfeld, U.; Hancock, D.; Hayes, A.; Selmer, P.; Hart, W.; Hlavka, D. ICESat-2 atmospheric channel description, data processing and first results. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSIDC (National Snow and Ice Data Center). ATL03 Data Dictionary (V07); NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center: Boulder, CO, USA. Available online: https://nsidc.org/sites/default/files/documents/technical-reference/icesat2_atl03_data_dict_v007.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Neumann, T.; Brenner, A.; Hancock, D.; Robbins, J.; Saba, J.; Harbeck, K.; Gibbons, A.; Lee, J.; Luthcke, S.; Rebold, T. ATLAS/ICESat-2 L2A Global Geolocated Photon Data (ATL03 Version 5); NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Parrish, C.E.; Magruder, L.A.; Herrmann, J.; Yoo, S.; Perry, J.S. ICESat-2 bathymetry Algorithms: A review of the current state-of-the-art and future outlook. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 223, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Zhang, H.; Cao, W.; Le, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; Lou, X. Cost-efficient bathymetric mapping method based on massive active–passive remote sensing data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 203, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.-S.; Tang, S.; Mo, F.; Ma, X. Machine learning based estimation of coastal bathymetry from ICESat-2 and Sentinel-2 data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, H.; Christiansen, P.; Kliving, P.; Andersen, O.; Nielsen, K. Evaluation of a statistical approach for extracting shallow water bathymetry signals from ICESat-2 ATL03 photon data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Liu, X.; Shen, X.; Jiang, L. A robust algorithm for photon denoising and bathymetric estimation based on ICESat-2 data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander, A.; Pitts, K.; Jelley, B.; Robbins, J.; Markel, J.; Popescu, S.; Nelson, R.; Harding, D.; Pederson, K.; Sheridan, R. Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat-2) Project Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document (ATBD) for Land-Vegetation Along-Track Products (ATL08), Version 4; NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center: Boulder, CO USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Lv, Y.; Yang, X.; Gong, H.; Li, G.; Lu, X. ICESat-2 shallow water bathymetric mapping based on a size and direction adaptive filtering algorithm. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 6279–6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Q.; Huang, G.; Tao, J. An optimal denoising method for spaceborne photon-counting LiDAR based on a multiscale quadtree. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, D. Satellite-derived bathymetry combined with Sentinel-2 and ICESat-2 datasets using machine learning. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1111817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Knudby, A. Global automated extraction of bathymetric photons from ICESat-2 data based on a PointNet++ model. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Song, Y.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, H.; Guan, H. A novel ICESat-2 signal photon extraction method based on convolutional neural network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magruder, L.; Brunt, K.; Neumann, T.; Klotz, B.; Alonzo, M. Passive ground-based optical techniques for monitoring the on-orbit ICESat-2 altimeter geolocation and footprint diameter. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA00141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-J.; Huang, C.-Y.; Jasinski, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Yamanokuchi, T.; Wang, C.-G.; Chang, T.-M.; Ren, H.; Kuo, C.-Y.; et al. A semi-empirical scheme for bathymetric mapping in shallow water by ICESat-2 and Sentinel-2: A case study in the South China Sea. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R.; Wouters, B. Supraglacial lake bathymetry automatically derived from ICESat-2 constraining lake depth estimates from multi-source satellite imagery. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 5115–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wu, T.; Xu, N. Methods to improve the accuracy and robustness of satellite-derived bathymetry through processing of optically deep waters. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Huang, P.; Li, B.; Tong, X. Auto-adaptive multi-level seafloor recognition and land-sea classification (AMSRLC) in reef-island zones using ICESat-2 laser altimetry. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 43, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xing, S.; Xu, Q.; Li, P.; Wang, D. A pre-pruning quadtree isolation method with changing threshold for ICESat-2 bathymetric photon extraction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, D.; Smith, A.; Redfern, T.; Talbot, A.; Lessnoff, A.; Dempsey, K. Using three dimensional convolutional neural networks for denoising echosounder point cloud data. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2019, 5, 1000016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Li, J.; Tang, Q.; Xu, W.; Dong, Z. ICESat-2 laser data denoising algorithm based on a back propagation neural network. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 8395–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, K.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Cui, A. A denoising methodology for detecting ICESat-2 bathymetry photons based on quasi full waveform. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4207916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Xu, N.; Zhang, W.; Li, S. Signal photon extraction method for weak beam data of ICESat-2 using information provided by strong beam data in mountainous areas. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-N. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–7 December 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- NSIDC (National Snow and Ice Data Center). Open Altimetry Platform; NSIDC: Boulder, CO, USA. Available online: https://openaltimetry.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov/data/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Ohlwiler, E.; Ghartey, C.; McCullough, R.; Parrish, C.; Magruder, L.; Dietrich, J.; Holwill, M.; Markel, J. ICESat-2 Bathymetry Training and Testing Database [Dataset]; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, C.; Magruder, L.; Perry, J.; Holwill, M.; Swinski, J.; Kief, K. Analysis and accuracy assessment of a new global nearshore ICESat-2 bathymetric data product. Earth Space Sci. 2025, 12, e2025EA004391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozinovski, S. Reminder of the first paper on transfer learning in neural networks, 1976. Informatica 2020, 44, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Region | Year | Approx. Lat/Lon Center | Number of ICESat-2 Granules | Number of Segments | Total PEs | NotBathy PEs | Bathy PEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key West (“KW”) | Florida Keys | 2019 | 24.60°N 81.50°W | 5 | 452 | 14,452,515 | 11,192,179 | 3,260,336 |

| Lin and Knudby (“L&K”) | Global | 2018 | Varies | 40 | 96 | 3,001,664 | 2,478,148 | 523,516 |

| OSU (“OSU”) | Global | 2019–2022 | Varies | Varies | 101 | 6,768,540 | 6,060,768 | 707,772 |

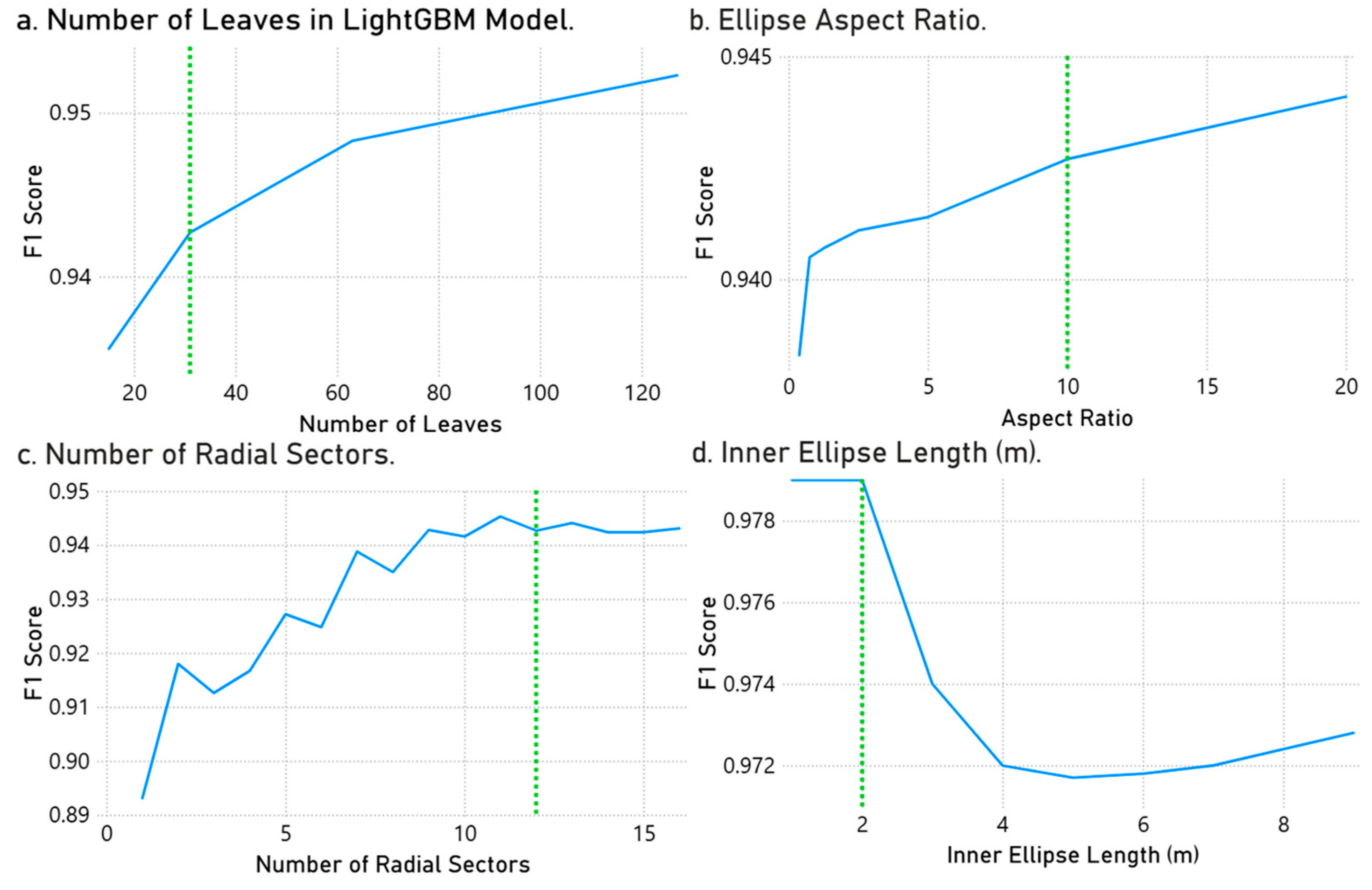

| Parameter | Type | Value Range Evaluated | Value Selected for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Leaves | Model | 15 to 127 | 31 |

| Aspect Ratio | Vectorization | 0.375 to 20 | 10 |

| Number of Sectors | Vectorization | 1 to 15 | 3 |

| Inner Horizontal Ellipse Length 1 | Vectorization | 1 to 9 | 2 1 |

| Dataset | Class | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support (% of Total) | NB + Bathy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KW | NotBathy | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 11,192,179 (77) | 14,452,515 |

| Bathy | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 3,260,336 (23) | |||

| L&K | NotBathy | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 2,478,148 (83) | 3,001,664 |

| Bathy | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 523,516 (17) | |||

| OSU | NotBathy | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 6,060,768 (90) | 6,768,540 |

| Bathy | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 707,772 (10) |

| Section | Subject | Figures– Tables | Results Summary Focus | Range of Results Metrics/ Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

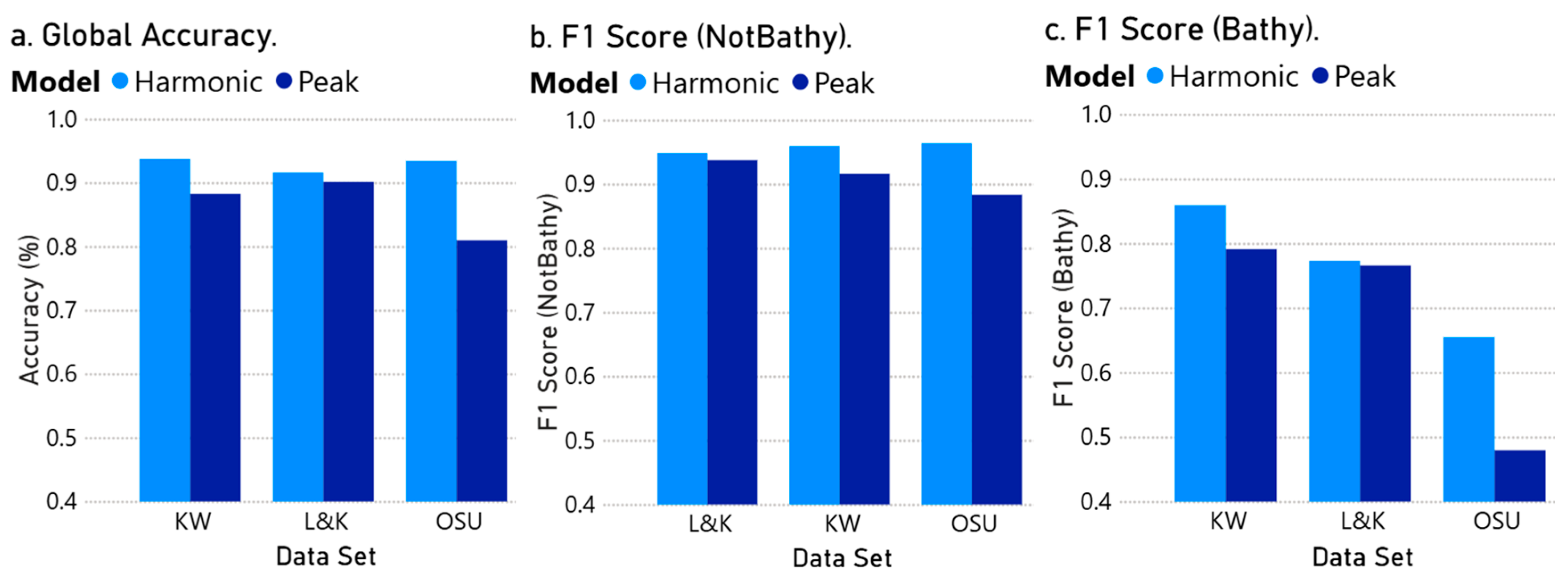

| Section 3.1 | Model goodness-of-fit | Table 4 | Classification Accuracy | 0.97–0.98 |

| Bathy/NotBathy F1 Scores | Bathy: 0.86–0.98 NotBathy: 0.98–1.0 | |||

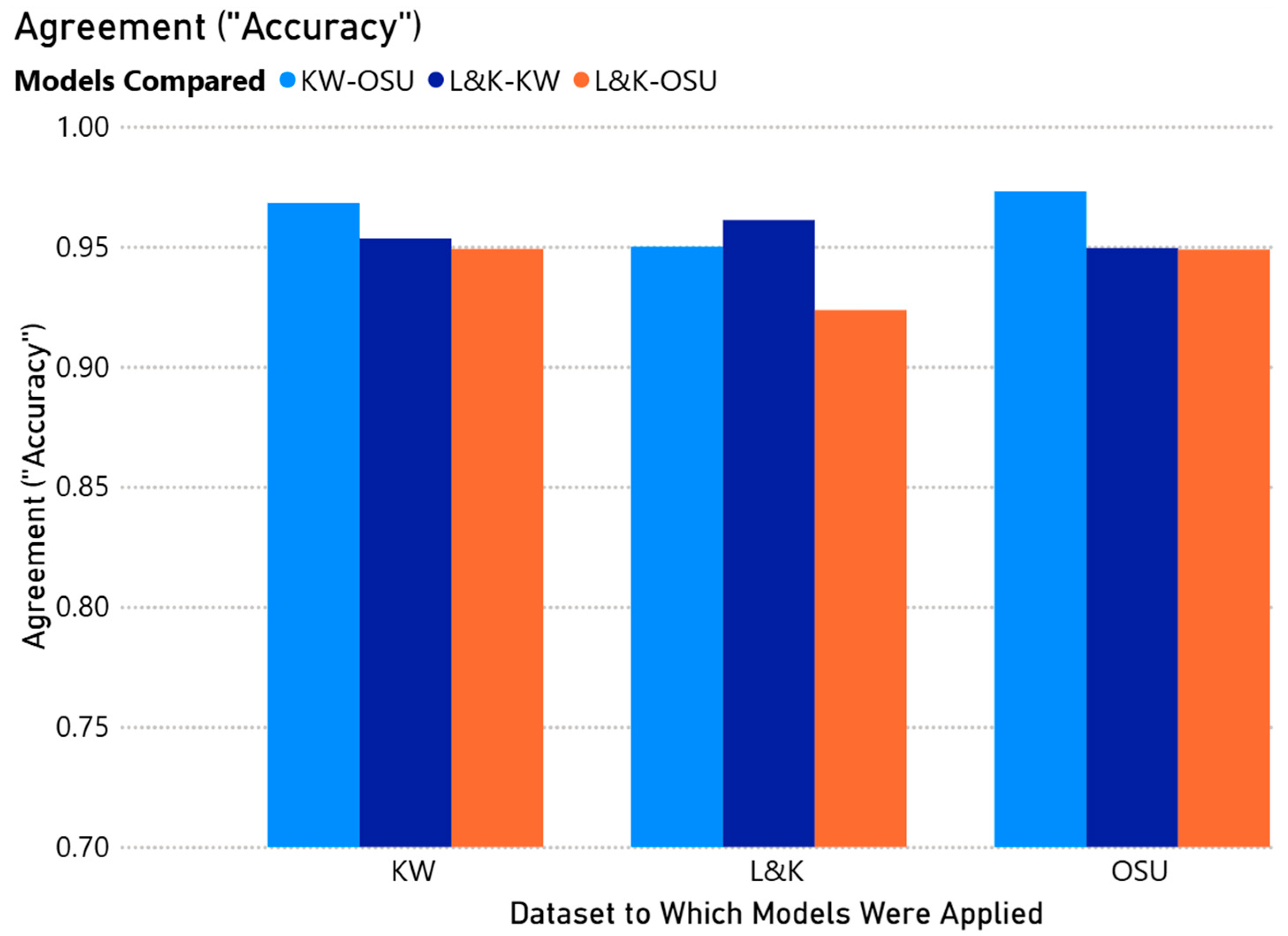

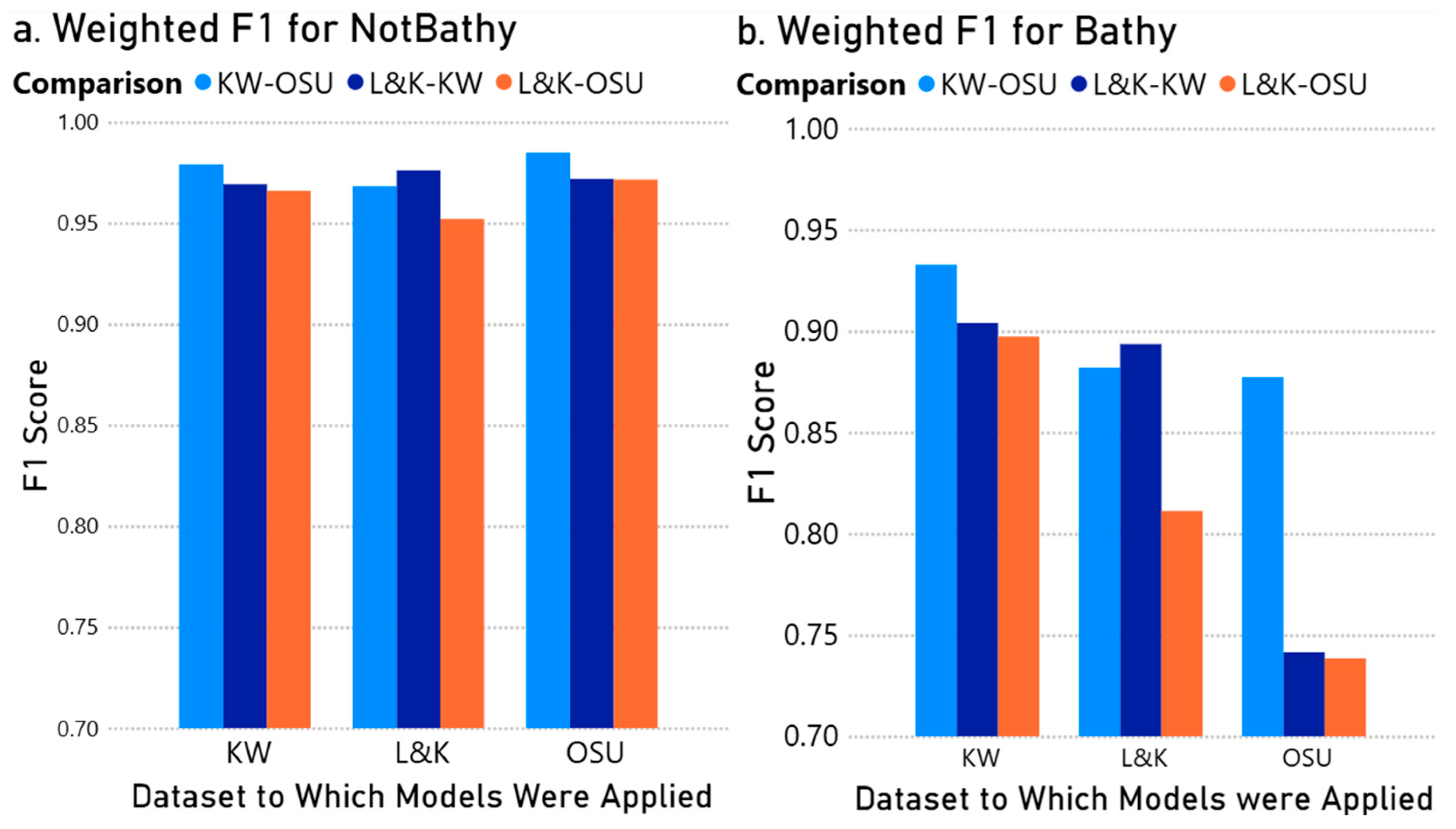

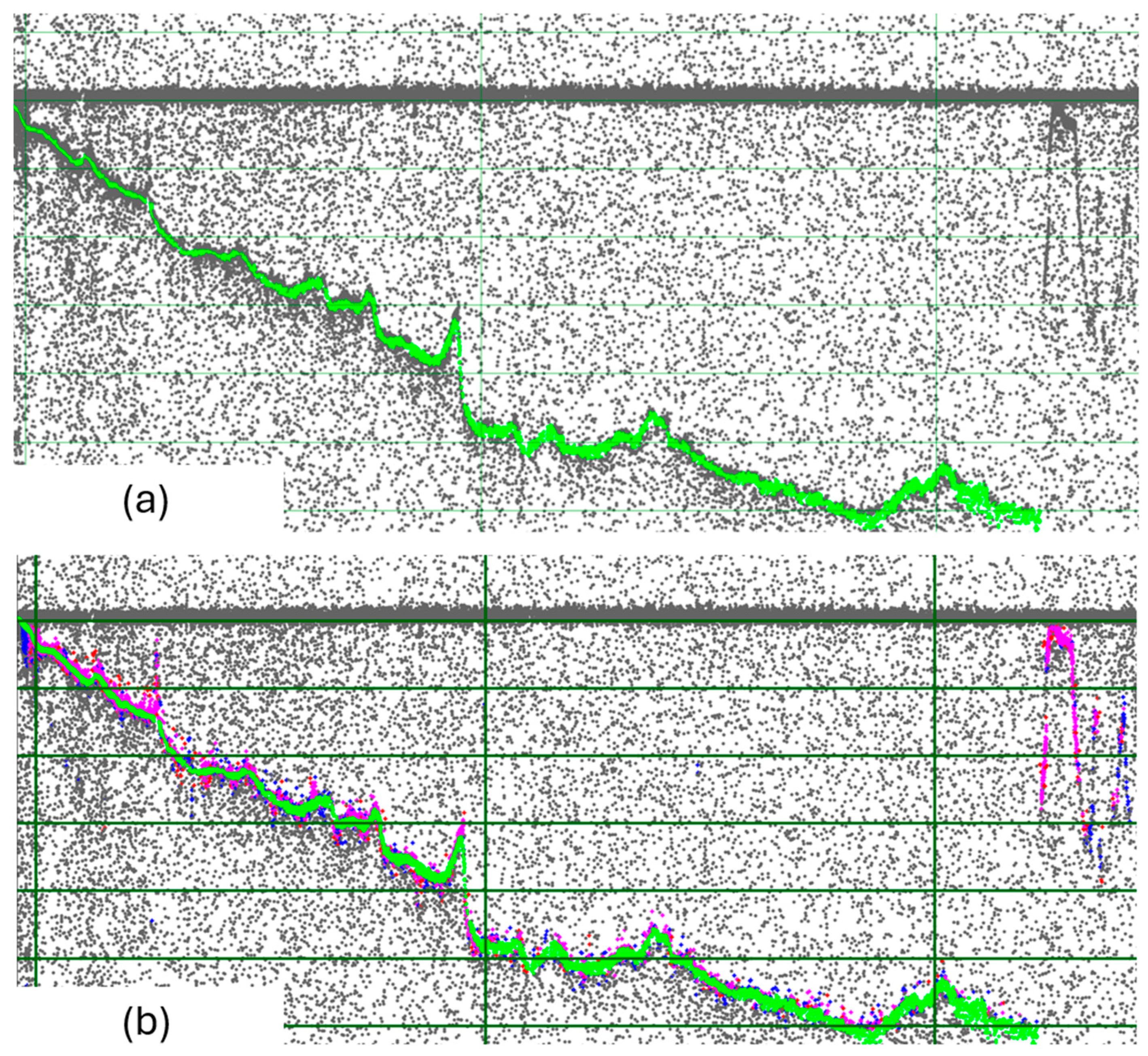

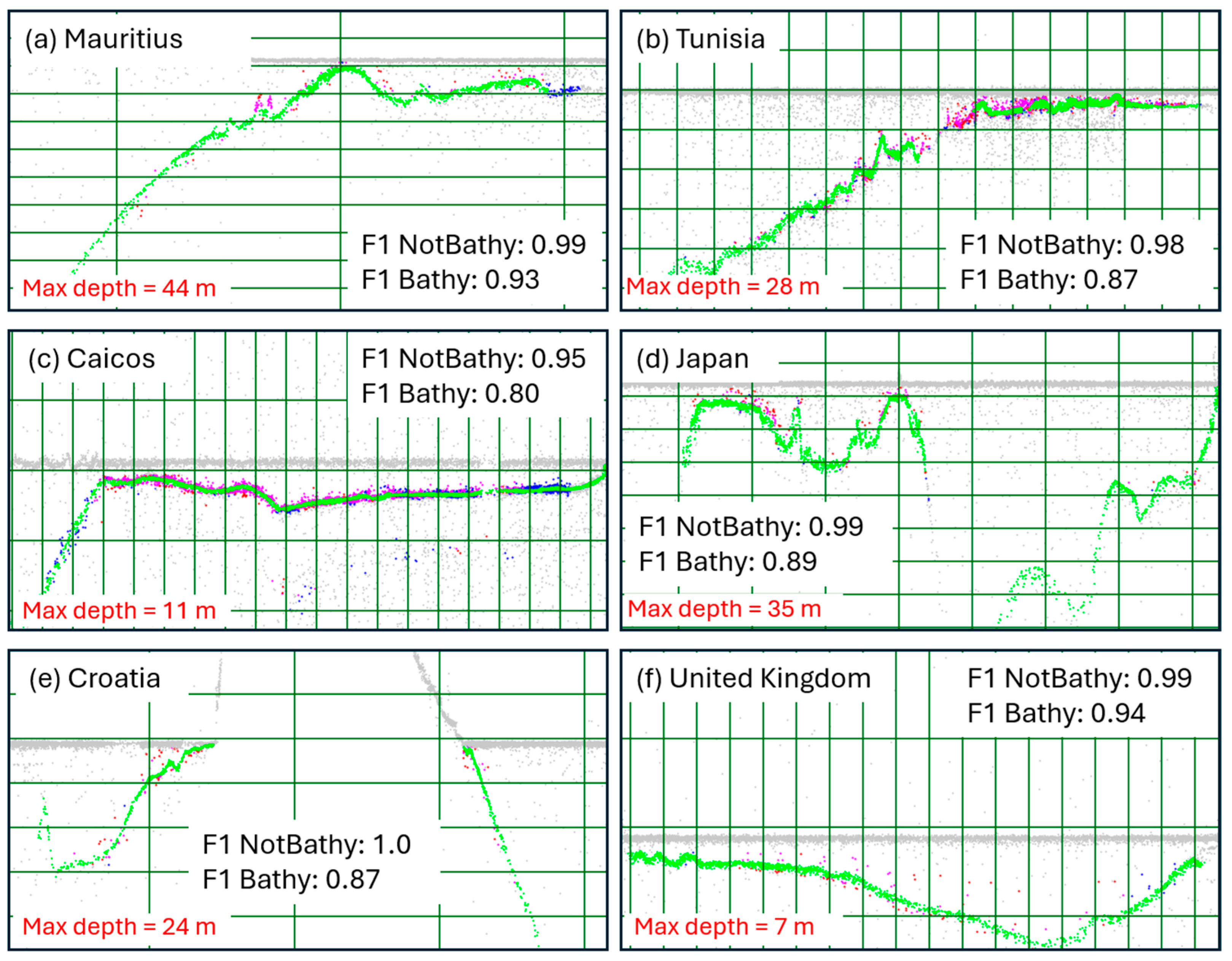

| Application of “Model A” to “Dataset B” | Figure 5 | Classification Accuracy | 0.925–0.975 | |

| Figure 6 | Bathy/NotBathy F1 Scores | Bathy: 0.73–0.93 NotBathy: 0.95–0.98 | ||

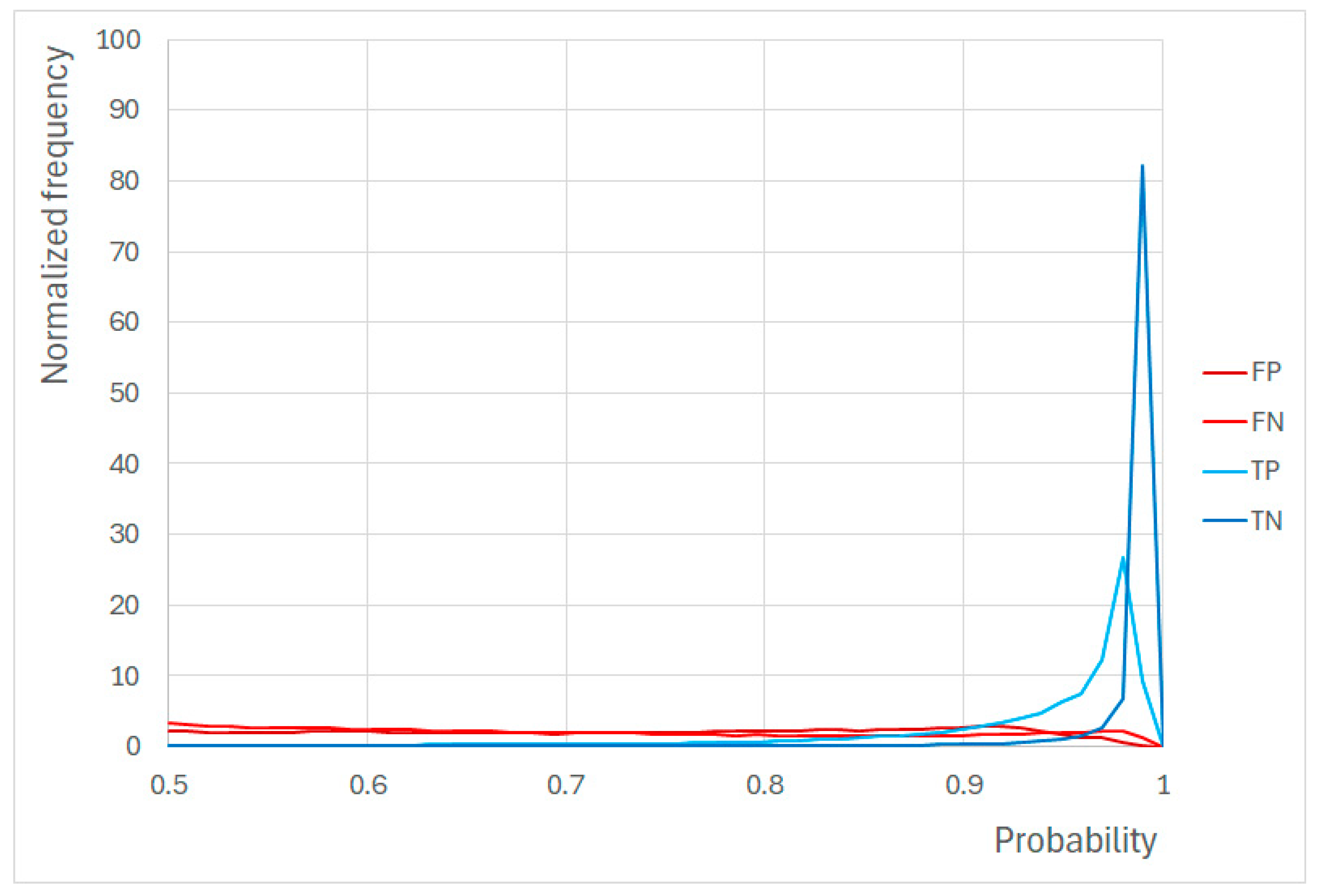

| Uncertainty of Classification | Figure 7 | Frequency distribution of p(Bathy) and p(NotBathy) relative to correctness of classification | True positives (p(Bathy)): 0.9–1.0 True negatives (p(NotBathy)): 0.97–1.0 | |

| Section 3.2 | Model sensitivity to tuning/hyper- parameters | Figure 8 | Change in F1 score for identification of Bathy PEs with change in parameter value | Conclusion: Sensitivity of model accuracy is low for (a) the number of leaves in a LightGBM model, (b) ellipse shape, (c) number of radial sectors dividing ellipses, (d) ellipse size. |

| Section 3.3 | Goodness-of-fit of models fitted using synthetic data | Figure 10 | Classification accuracy | 0.8–0.93 |

| Bathy/NotBathy F1 Scores | Bathy: 0.86–0.98 NotBathy: 0.48–0.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rzhanov, Y.; Lowell, K. An Algorithm for Extracting Bathymetry from ICESat-2 Data That Employs Structure and Density Using Concentric Ellipses. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010025

Rzhanov Y, Lowell K. An Algorithm for Extracting Bathymetry from ICESat-2 Data That Employs Structure and Density Using Concentric Ellipses. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleRzhanov, Yuri, and Kim Lowell. 2026. "An Algorithm for Extracting Bathymetry from ICESat-2 Data That Employs Structure and Density Using Concentric Ellipses" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010025

APA StyleRzhanov, Y., & Lowell, K. (2026). An Algorithm for Extracting Bathymetry from ICESat-2 Data That Employs Structure and Density Using Concentric Ellipses. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010025