Highlights

What are the main findings?

- GAN-generated SAR imagery can effectively substitute for authentic SAR data in damage classification tasks.

- The proposed approach achieves accurate building damage classification using pre-disaster synthesized SAR imagery.

What are the implications of the main finding?

- Synthesized SAR data can support damage mapping when authentic pre-disaster SAR imagery is limited or unavailable.

- GAN-based SAR generation has strong potential to enhance rapid post-disaster response and recovery planning.

Abstract

Reliable assessment of building damage is essential for effective disaster management. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) has become a valuable tool for damage detection, as it operates independently of the daylight and weather conditions. However, the limited availability of high-resolution pre-disaster SAR data remains a major obstacle to accurate damage evaluation, constraining the applicability of traditional change-detection approaches. This study proposes a comprehensive framework that leverages generated SAR data alongside optical imagery for building damage detection and further examines the influence of elevation data quality on SAR synthesis and model performance. The method integrates SAR image synthesis from a Digital Surface Model (DSM) and land cover inputs with a multimodal deep learning architecture capable of jointly localizing buildings and classifying damage levels. Two data modality scenarios are evaluated: a change-detection setting using pre-disaster authentic SAR and another using GAN-generated SAR, both combined with post-disaster SAR imagery for building damage assessment. Experimental results demonstrate that GAN-generated SAR can effectively substitute for authentic SAR in multimodal damage mapping. Models using generated pre-disaster SAR achieved comparable or superior performance to those using authentic SAR, with scores of 0.730, 0.442, and 0.790 for the survived, moderate, and destroyed classes, respectively. Ablation studies further reveal that the model relies more heavily on land cover segmentation than on fine elevation details, suggesting that coarse-resolution DSMs (30 m) are sufficient as auxiliary input. Incorporating additional training regions further improved generalization and inter-class balance, confirming that high-quality generated SAR can serve as a viable alternative especially in the absence of authentic SAR, for scalable, post-disaster building damage assessment.

1. Introduction

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery plays a vital role in disaster response due to its ability to capture surface information independent of weather and lighting conditions [1,2,3]. High-resolution SAR is particularly valuable for building damage assessment, as it enables the identification of structural features such as debris and collapse patterns [4,5]. However, access to high-resolution SAR data remains limited; acquisitions are often costly, geographically restricted, and frequently available only after a disaster. For reliable building damage assessment, deep learning approaches typically require paired pre- and post-disaster observations to learn disaster-induced structural changes rather than relying solely on post-disaster backscatter intensity [6,7,8]. In the absence of pre-disaster SAR imagery as a baseline, models may misinterpret normal backscatter variability as damage, leading to an increased rate of false positive predictions. Accordingly, we focus on SAR-based damage assessment and structure our experiments to isolate the contribution of synthesized pre-disaster SAR, using authentic pre-disaster SAR as a controlled reference while keeping all other experimental settings fixed.

To address the lack of pre-disaster SAR data, simulation-based approaches have emerged as a promising alternative. Recent advances in SAR image synthesis leverage either physical modeling [9] or deep generative frameworks to approximate radar backscatter from 3D structural or land cover information [10]. Among the conditioning inputs, elevation data such as Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) and land cover maps play a key role in defining scattering geometry and shadowing effects, directly influencing the realism of the generated SAR outputs. However, the availability and spatial resolution of DEM data vary considerably across regions, raising important questions about how elevation quality affects SAR synthesis. To investigate this, we conduct an ablation study using DSM inputs of different resolutions to evaluate the impact of elevation quality on the accuracy of the generated SAR imagery.

To address this limitation, we adapt and extend the SPADE-GAN (Spatially Adaptive Normalization GAN) framework [10] for generating synthetic pre-disaster SAR imagery. Our approach leverages land cover segmentation maps and elevation data as conditioning inputs to produce realistic SAR images in regions where authentic pre-disaster acquisitions are unavailable. The proposed pipeline comprises three key steps: (1) generation of high-resolution land cover maps, (2) synthesis of SAR imagery using land cover and terrain elevation, and (3) building damage classification using generated pre-disaster SAR imagery in combination with post-disaster acquisitions. In addition, we conduct an ablation study on elevation inputs, comparing the role of DSM (Digital Surface Model) and DEM (Digital Elevation Model) sources in the synthesis process.

We evaluate the fidelity of GAN-generated SAR (hereinafter referred to as synthesized SAR) against authentic SAR using perceptual similarity metrics (FID, SSIM, MAE, and LPIPS) and assess its task-specific utility in building damage classification. For the latter, we employ a transformer-based model, MambaBDA [11], to perform multi-class building damage classification. By comparing synthesized SAR directly with authentic SAR observations, we establish a modality-consistent baseline that isolates the contribution of SAR synthesis without confounding effects from crossmodality differences.

Our experiments demonstrate that incorporating pre-disaster information is critical for accurate building damage assessment. Notably, the configuration using synthesized pre-disaster SAR and authentic post-disaster SAR achieved the best overall performance, surpassing even setups that included authentic SAR or optical imagery. This finding underscores the potential of synthesized SAR to serve as a reliable substitute when pre-disaster acquisitions are unavailable, offering a cost-effective and operationally feasible pathway for disaster response. Motivated by the limited availability of pre-disaster SAR imagery for operational damage assessment, the contributions of this work are threefold:

- We adapt and extend SPADE-GAN to synthesize SAR imagery for geographically localized datasets, explicitly addressing the scarcity of authentic pre-disaster SAR acquisitions in disaster-prone regions.

- We conduct a comprehensive evaluation of synthesized SAR fidelity using both perceptual similarity metrics and downstream building damage classification tasks.

- We demonstrate that synthesized SAR can effectively substitute or complement authentic pre-disaster SAR imagery, improving building damage detection in data-scarce regions.

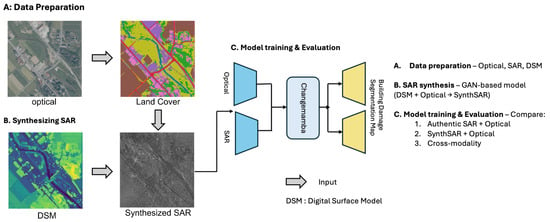

Overall, our study demonstrates the potential of synthesized SAR as a reliable complement or alternative to authentic SAR, enabling operationally feasible, large-scale building damage assessment. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 describes the datasets used in this study. Section 4 details the proposed methodology. Section 5 presents the experimental setup and ablation studies. Section 6 discusses the results of building damage assessment. Finally, Section 7 provides concluding remarks and future directions. An overview of the proposed research framework, which guides the subsequent methodology, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework. (A) Data preparation: land cover maps are generated from optical imagery. (B) SAR synthesis: generated SAR images are produced using DSM and land cover inputs using SPADE-GAN. (C) Model training and evaluation: the proposed models are trained and evaluated using the prepared datasets.

2. Related Works

In this section, we review prior research relevant to building damage assessment using remote sensing data. We first discuss traditional and machine learning-based approaches for damage classification, highlighting the strengths and limitations of optical and SAR imagery. Next, we examine methods for synthetic data generation, including GAN-based and physics-based SAR simulations, and their applications in augmenting training datasets for machine learning models.

2.1. Building Damage Classification

Accurate building damage classification is essential for effective disaster response and recovery planning. Broadly, two approaches exist, visual interpretation [12] and automated methods based on remote sensing data, which have been widely adopted for their ability to provide timely and large-scale situational awareness. Although optical imagery is valuable, its dependence on daylight, cloud-free conditions and variable spatial resolution limits its utility, motivating the use of SAR for reliable, all-weather monitoring.

More recently, SAR has emerged as a critical source of information for damage mapping. Its side-looking geometry, insensitivity to weather conditions, and distinctive scattering mechanisms offer clear advantages over optical imagery, particularly for rapid post-disaster assessment [13,14]. The effectiveness of SAR-based methods, however, depends heavily on the availability of consistent pre- and post-disaster acquisitions [15], which are often constrained by orbital dynamics, revisit intervals, and data access policies [16].

The accuracy of building damage assessment depends on multiple factors, including spatial resolution and imaging modality. Low-resolution SAR is generally limited to regional-scale analysis, whereas reliable building-level mapping typically requires high-resolution datasets, particularly within the X-band frequency range [17]. However, access to such data is constrained by the limited number of operational high-resolution SAR satellites and delays in data acquisition and distribution [18].

To address these challenges, synthesized SAR imagery has been investigated as a complementary data source. Synthetic datasets can help mitigate data scarcity and serve as valuable training datasets for machine learning models. While promising, current simulation methods are often constrained by simplified reflection models and approximated surface interactions. These physics-based simulations require accurate 3D building geometries and explicit representation of structural damage. These prerequisites make it difficult to simulate large-scale disaster scenarios or irregular, partial collapses typical of moderate damage, limiting their ability to reproduce the complex scattering behavior observed in real-world environments [19,20,21]. In contrast, GAN-based data-driven simulations can learn to approximate SAR backscattering from observed data, complementing rather than replacing physics-based approaches.

2.2. Machine Learning-Based Data Synthesis

Traditional augmentation techniques such as geometric transformations and random cropping can increase dataset diversity, but they are often less effective for SAR imagery due to its complex radiometric and geometric distortions [22].

In some cases, inappropriate transformations may even degrade detection performance [23,24]. More advanced approaches focus on generating entirely new samples through physics-based simulation or generative models.

Recent advances in deep learning have enabled powerful crossmodal translation methods that preserve structural features while synthesizing realistic imagery. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) [25] have been particularly successful. Architectures such as U-Net [26] and conditional GANs (cGANs) [27] can generate high-quality outputs from paired data, while unpaired frameworks extend this capability to broader applications. Within SAR, GAN-based methods have been applied to SAR-to-optical and optical-to-SAR translation [28,29], as well as direct SAR generation from semantic inputs [30]. For example, Pix2Pix [31] introduced supervised image-to-image translation, while SPADE-GAN [10] demonstrated semantic-guided SAR synthesis.

While GAN-based approaches have achieved impressive progress in generating realistic SAR imagery, they are inherently data-driven and may not always capture the full complexity of radar–surface interactions [32]. Nevertheless, GANs offer unique advantages over physics-based simulators: they can rapidly generate large and diverse datasets, adapt to different sensor characteristics and acquisition conditions, and produce visually realistic imagery suitable for training machine learning models. Physics-based SAR simulators [13,33,34,35], in contrast, provide fine-grained control over radar–surface interactions and ensure physical consistency, albeit at higher computational cost. Well-known simulators include RaySAR [36], CohRaS [37], SARsim [38], and SARViz [39]. Taken together, GAN-based synthesis and physics-based simulation represent complementary approaches: GANs excel at producing large, visually realistic datasets that capture real-world variability, while physics-based simulators ensure physically accurate representations of radar–surface interactions.

2.3. Synthesized Data for Damage Mapping

Synthetic data have been investigated as a means of supporting damage detection, mapping, and data augmentation in remote sensing applications [40]. In the context of building damage assessment, several studies have demonstrated the utility of synthesized SAR imagery. For instance, ref. [41] employed ray-tracing simulations with the RaySAR platform to generate pre-disaster imagery for damage mapping. Their results showed that synthesized SAR can reproduce backscattering characteristics and holds promise as a substitute for authentic data in building damage assessment tasks.

Kuny et al. [42,43,44] conducted a series of studies using the CohRas simulator in combination with TerraSAR-X post-disaster data. Their 2013 work examined SAR signatures of different types of building damage for classification [42], followed by a 2015 study focusing on distinguishing debris from high vegetation [43]. This line of research was further extended in 2016 to separate debris from other patterns such as vegetation and gravel [44]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the feasibility of synthesized SAR for extracting damage-related features. Nonetheless, the reliance on generalized three-dimensional building models, particularly for high-rise structures, restricted the diversity of damage signatures and introduced potential false positives [32].

These works represent physics-based simulation approaches, which can reproduce detailed scattering mechanisms through ray tracing. However, they depend heavily on accurate 3D building models and are computationally demanding, limiting their scalability for large-scale applications. In contrast, SPADE-GAN offers a data-driven alternative that synthesizes SAR imagery from readily available auxiliary data, such as DSMs and land cover maps. By learning statistical relationships from real SAR data, this approach generates realistic backscattering patterns and scalable training samples, making it well suited for deep learning–based damage assessment.

2.4. Machine Learning-Based Damage Classification

Recent advances in machine learning have significantly advanced automated damage mapping from remote sensing imagery [45]. Random Forest [46], SVM [47], Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and encoder–decoder architectures such as U-Net have been widely adopted for pixel-level classification. These models demonstrate strong performance but remain dependent on the availability of large, well-annotated datasets.

The rise of transformers has further transformed the field. Self-attention mechanisms enable global context modeling, improving the detection of subtle or spatially disjoint damage features. Recent architectures include [48], the Bitemporal Attention Transformer [49], and Swin Transformer variants for building-level damage mapping [50]. Hybrid approaches that integrate CNN backbones with transformer modules have also been proposed to leverage both local texture features and long-range dependencies [51] for remote sensing change detection.

Despite these advances, several challenges persist. Model performance is hindered by data scarcity, particularly for high-resolution SAR; by the high cost of manual annotation; and by inconsistencies across different disaster domains [52]. To alleviate these issues, synthesized SAR imagery has been explored as a means to augment training datasets and improve model robustness [19,20,21].

3. Dataset

This section describes the datasets used in this study and the preprocessing steps applied to prepare them for training and evaluation. We employed datasets from GeoNRW [53] and Japan (Noto and Shizuoka), which include LiDAR-derived DSMs and corresponding SAR imagery at 1 m resolution. To adapt SPADE-GAN for a geographically localized setting in Japan, we expanded the training set to incorporate the Noto and Shizuoka regions.

In the Noto, Japan, and Shizuoka, Japan, datasets, DSMs were synthesized from LiDAR data to capture terrain and building structures, while the corresponding SAR images were obtained from the Synspective StriX-3 satellite, as summarized in Table 4.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

Preprocessing was applied to both SAR and LiDAR datasets to ensure consistency and quality. For SAR imagery, preprocessing included speckle filtering using a Lee filter with a window, followed by radiometric calibration and geocoding. For LiDAR point clouds, point filtering and rasterization were performed using GDAL (https://gdal.org/en/stable/ accessed on 3 July 2025). The datasets used in this study have different spatial resolutions: 0.25 m for Noto, Japan, and Shizuoka, and 1.0 m for GeoNRW. To synchronize the spatial resolution of datasets, the Noto and Shizuoka from Synspective [54] data were downsampled to 1.0 m resolution.

3.2. Building Damage Dataset

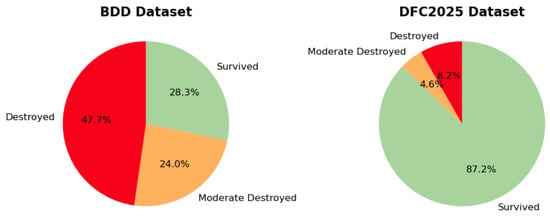

In this study, we employ a building damage dataset that integrates multimodal remote sensing imagery with annotated building-level damage labels. The dataset comprises pre- and post-disaster SAR and optical imagery, which serve as the primary inputs for training and evaluating our proposed models. An overview of the dataset is presented in Table 1, and the distribution of pixels across different damage categories in both the BDD and DFC datasets is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Overview of BDD dataset, events, remote sensing data, and building damage datasets.

Figure 2.

Distribution of pixels across different building damage categories in the BDD and DFC2025 datasets, showing the proportion of survived, moderately damaged, and destroyed buildings.

Because the ground-truth annotations were compiled from multiple sources, inconsistencies were observed in the original damage grading schemes. To ensure comparability across scenarios, we reclassified the labels into three standardized categories: survived, moderately damaged, and destroyed. The availability of pre- and post-disaster data for each region is summarized in Table 1.

For model training and evaluation, all imagery was partitioned into fixed-size patches (512 × 512 pixels) to accommodate large scene dimensions and preserve spatial alignment across modalities. This preprocessing ensured consistent input dimensions for both SAR and optical data while maintaining correspondence with building-level annotations.

3.3. DFC2025 Dataset

In addition to the above dataset, we utilized the DFC2025 dataset [55], a globally distributed multimodal building damage assessment benchmark released as part of the IEEE GRSS Data Fusion Contest 2025. It contains very-high-resolution imagery (0.3–1 m) for all-weather disaster response, covering five types of natural disasters and two types of man-made disasters across regions worldwide. The dataset places particular emphasis on developing countries, where external assistance is most needed. The optical and SAR imagery in DFC2025 provides detailed representations of individual buildings, making it well suited for precise damage assessment. Since the dataset includes only pre-disaster SAR and post-disaster optical imagery, we synthesized SAR images using SPADE to adapt it for our multimodal damage classification experiments. The details of the dataset are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of the DFC2025 dataset: events, remote sensing data sources, and number of paired samples.

4. Methodology

This section presents the methodology employed for building damage assessment using GAN-based SAR data synthesis. We begin by describing land cover mapping derived from OEM data, followed by the process for generating synthesized SAR imagery. Next, we outline the design of our ablation studies and the evaluation metrics used to assess model performance.

4.1. Land Cover Mapping from OEM

Accurate land cover classification plays a foundational role in damage assessment by delineating built-up areas and other relevant land types. In this study, we utilized the OpenEarthMap (OEM) dataset [56], a large-scale benchmark for global high-resolution land cover mapping.

We first trained a land cover classification model using optical Earth observation imagery (OEM) and subsequently applied it to the optical imagery of the Shizuoka and Noto datasets to generate segmentation maps. The resulting land cover maps were then used as conditioning inputs for the SAR synthesis stage. The land cover classification model is based on a U-Net architecture with an EfficientNet-B4 encoder backbone pretrained on ImageNet. The network takes optical imagery as input and produces pixel-wise land cover predictions for eight classes. Training was conducted for 150 epochs using the Adam optimizer with a fixed learning rate of . To address class imbalance, a composite loss function consisting of Jaccard loss, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) loss, and focal loss was employed. The model was evaluated using mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) across all classes. The corresponding land cover classes are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Land cover classes and visualization colors in OpenEarthMap.

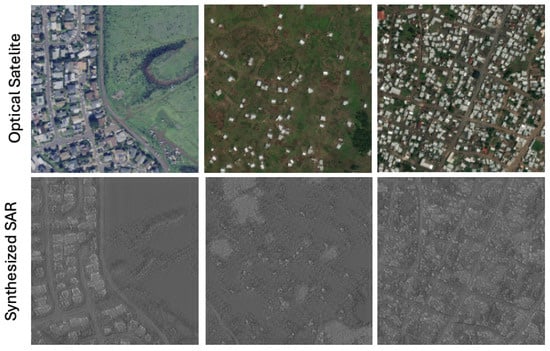

4.2. Generation of Synthesized SAR Imagery

High-resolution pre-disaster SAR imagery is often unavailable, limiting the application of SAR-based change detection for rapid disaster response. To address this gap, we used SPADE-GAN as in [10], a generative adversarial network for semantic image synthesis, to generate synthetic SAR imagery. The model was conditioned on the prepared land cover maps together with elevation data from DSMs or DEMs of varying resolutions. By combining structural cues from land cover with elevation information, SPADE-GAN produced realistic pre-disaster SAR images that could be used in subsequent experiments on damage detection. For training, we adopted the original SPADE-GAN architecture to maintain consistency with adjustments to the learning rate to accommodate the specific characteristics of our dataset. Whereas the original SPADE-GAN model was trained on the GeoNRW dataset [53], we extended the training set with additional samples from Shizuoka and Noto to increase geographic diversity and improve the model’s ability to generalize across different urban layouts and terrain types. The training configuration follows the two-time-scale update rule (TTUR) [57], with generator and discriminator learning rates set to and , respectively. Training was conducted for 200 epochs with a batch size of 64. The input land cover map and DEM were resized to during training using random cropping from the original inputs. The model capacity parameter was set to 64, with four sampling layers and two multi-scale discriminators. The loss balancing coefficient was fixed to 5.0 throughout training. The dataset details are summarized in Table 4, and an example of the synthesized SAR is shown in Figure 3.

Table 4.

Overview of datasets used for SPADE-GAN training, including SAR, DSM, land cover data, and sources.

Figure 3.

Synthesized SAR and corresponding optical imagery covering grass, roads, and buildings in the dataset.

The quality of the synthesized imagery was evaluated using the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), a widely adopted metric for assessing generative model performance. The evaluation was conducted on test scenes within the GeoNRW region, including Düsseldorf, Herne, and Neuss. As summarized in Table 5, the extended dataset reduces the FID score from 0.0005 (GeoNRW + Noto + Shizuoka) to 0.0002, demonstrating improved realism and diversity in the synthesized SAR imagery.

Table 5.

Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores for SPADE-GAN trained on the original GeoNRW dataset and retrained with additional Noto and Shizuoka samples. Lower FID indicates improved realism of synthesized SAR images.

Overall, by incorporating semantic priors from land cover maps and geometric constraints from DEMs, the proposed approach generates realistic and diverse synthetic SAR images that can effectively substitute for authentic pre-disaster SAR data in building damage assessment workflows.

4.3. Evaluation Schemes and Metrics

We designed a two-fold evaluation framework to assess both the quality of synthesized SAR imagery and its usefulness for building damage classification. In particular, we adopt the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) evaluation using pretrained U-Net segmentation models from [10].

The image similarity metrics used are particularly appropriate for imbalanced datasets. Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation: image similarity metrics assess the realism and fidelity of the synthesized SAR images, while the score quantifies the effectiveness for building damage classification.

- Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) [58]: measures the distributional distance between feature embeddings of real and synthesized images, with lower values indicating higher realism. Here, the FID is computed using features extracted from a pretrained U-Net adapted for SAR.

- Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) [59]: captures structural consistency, luminance, and contrast.

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [60]: computes the average absolute pixel-wise difference.

- Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [61]: evaluates perceptual similarity using deep feature representations from pretrained networks.

The score balances precision and recall:

4.4. Comparative Studies on Elevation Input for SAR Synthesis

SPADE-GAN relies on land cover segmentation, with elevation data included as auxiliary inputs. Prior work in [10] has shown that DEMs help reduce ambiguities in image generation; however, DEMs alone cannot distinguish flat regions such as water, roads, or agricultural fields, often leading to class confusion. In practice, land cover maps are more readily available. In contrast, high-resolution LiDAR-derived DSMs are not, making coarser global datasets (e.g., DSM 30 m) from SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission) a more feasible alternative.

We conducted ablation experiments to evaluate the impact of different elevation sources during the SAR synthesis phase. The SPADE-GAN model was trained with LiDAR DSM + land cover maps, and during generation, we substituted DSM 30 m or DTM 5 m as auxiliary inputs. The resulting synthesized SAR images were compared to reference outputs using SSIM, MAE, and LPIPS to quantify similarity.

The quantitative similarity analysis (Table 6) shows that DSM 30 m versus DSM 1 m achieves a higher SSIM and lower MAE and LPIPS compared to DTM 5 m versus DSM 1 m, indicating closer alignment with the high-resolution LiDAR DSM. These results suggest that the model relies primarily on land cover segmentation rather than fine elevation details, as even the coarser DSM preserves sufficient structural cues for building shapes and terrain context. For subsequent experiments, including building damage detection, we selected DSM 30 m as the auxiliary elevation input for Haiti, Tohoku, Tacloban, and Palu, balancing the availability of global DSM data with the need to retain essential structural information. Moreover, when DSM data are unavailable, SAR imagery synthesized from available inputs can serve as a practical substitute, providing sufficient structural information to maintain robust model performance.

Table 6.

Comparison of elevation datasets against LiDAR DSM (DSM1m). A higher SSIM and lower MAE/LPIPS indicate better structural similarity. DTM5m = 5 m Digital Terrain Model, DSM30m = 30 m Digital Surface Model, and DSM1m = 1 m LiDAR DSM (reference). The arrow symbols indicate the preferred direction of each metric: ↑ means higher values indicate greater similarity, while ↓ means lower values indicate greater similarity.

5. Experimental Setup and Results

In this section, we evaluate the performance of our proposed GAN-based SAR data synthesis framework for building damage assessment. We first describe the datasets, preprocessing procedures, and model configurations used in our experiments. Next, we present the evaluation metrics and experimental protocols, followed by a detailed discussion of the results and their implications. Since this study focuses on SAR-based damage assessment, synthesized SAR imagery is compared against authentic SAR observations, providing a direct and task-relevant baseline for evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed SAR synthesis framework.

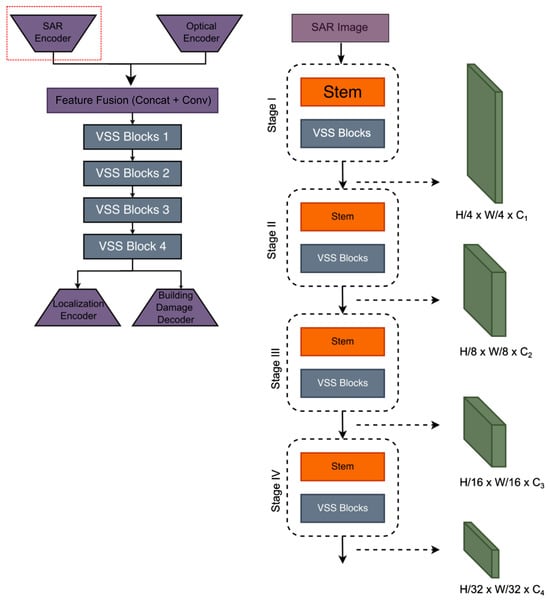

5.1. Model Architecture

The model used in this study is based on the transformer-based MambaBDA framework proposed by [11]. MambaBDA is a dual-branch Siamese encoder–decoder architecture designed for joint building localization and damage classification. The network follows a dual-branch architecture, The network consists of two task-specific branches, where one branch focuses on building localization and the other on damage classification. Both branches are built upon a shared backbone encoder based on the Vision State Space Model (VMamba) [62], which is capable of capturing long-range dependencies in image sequences while maintaining computational efficiency. To adapt MambaBDA to our experimental setting, we introduce an additional encoder to process pre-disaster SAR imagery. While the original MambaBDA employs weight-sharing Siamese encoders for pre- and post-disaster optical images, our modified architecture incorporates a dedicated VMamba-based encoder specialized for SAR inputs. This design enables the network to better exploit the complementary characteristics of optical and SAR modalities for robust building damage assessment. An overview of the Mamba architecture is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Overview of the MambaBDA architecture. The right part shows the SAR encoder based on stacked Vision State Space (VSS) blocks with hierarchical downsampling, while the extracted multi-scale features are provided to the decoder for damage assessment. The red box highlights the added SAR encoder introduced in this study.

5.2. Loss Function

The loss formulation follows the original MambaBDA [11] with minor adaptations. The outputs of the localization and classification branches, including the additional SAR encoder introduced in this study, are used to compute the combined cross-entropy and Lovasz-Softmax loss. Following MambaBDA, we adopt the same loss weighting configuration (1, 1, 0.5, and 0.75) without further tuning to ensure full comparability with the baseline implementation.

where and are cross-entropy losses for localization and classification, and and are Lovasz-Softmax losses that improve boundary alignment. This formulation ensures both accurate building footprint detection and precise damage categorization.

5.3. Data Modality Scenarios

Change-detection approaches that utilize pre- and post-disaster imagery under similar observation conditions are highly effective for building damage assessment. However, in real-world disaster response, pre-disaster data, particularly SAR imagery, are often unavailable. To evaluate the feasibility of using synthesized SAR as a substitute for authentic pre-disaster SAR, we define two experimental scenarios.

In our experiments, the synthesized SAR imagery is generated using a SPADE-GAN-based generator trained on two configurations: (1) the GeoNRW dataset and (2) the combined GeoNRW + Japan dataset (ours). Incorporating the Japan data introduces greater scene diversity, enabling the generator to learn more varied structural and textural patterns, thereby enhancing the realism and generalization of the synthesized SAR imagery.

- Authentic Pre-disaster SAR + Optical and Post-disaster SAR: In this ideal scenario, both pre- and post-disaster SAR and optical imagery are available. The optical images primarily serve for building localization, while SAR imagery provides complementary structural information. This setting represents the upper bound of achievable model performance.

- Synthesized Pre-disaster SAR + Optical and Post-disaster SAR: In this more realistic scenario, authentic pre-disaster SAR data are unavailable and are replaced with synthesized SAR imagery generated from the available DSM and land cover maps. The optical imagery is again used for building localization. This configuration simulates practical post-disaster conditions where pre-disaster SAR acquisitions are missing and serves as the main focus of this study.

5.4. Implementation Details

The MambaBDA model was trained using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with a momentum of 0.9 and a weight decay of . Training was performed for 200 epochs with a batch size of 2. The initial learning rate was set to 0.1, following the original Mamba configuration, and was decayed by a factor of 0.1 at epochs 100 and 150 using a MultiStep learning rate scheduler.

6. Result and Discussion

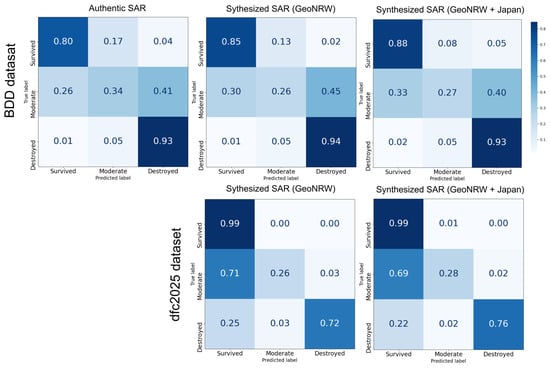

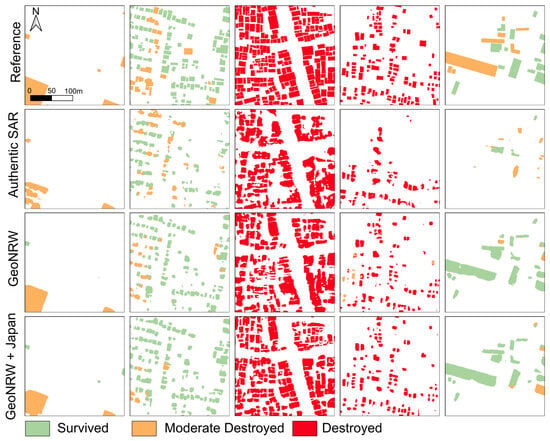

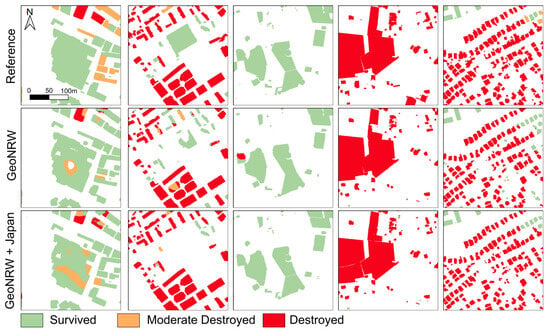

In our experiments, we assessed building damage classification performance using both authentic and synthesized SAR data from two datasets: BDD (2409 pairs) and DFC2025 (3239 pairs). Table 7 and Figure 5 summarize the scores and confusion matrices, highlighting consistent trends across different data modalities and datasets. Visual comparisons of the resulting damage maps are provided for BDD in Figure 6 and for DFC2025 in Figure 7.

Table 7.

Per-class scores for building damage classification across different datasets and SAR modalities. The highest for each class is highlighted in bold.

Figure 5.

Normalized per-building confusion matrices for building damage classification. Each cell shows the proportion of buildings predicted as each class. Top row: BDD and DFC2025 datasets, with left showing authentic SAR input (GeoNRW) and right showing synthesized SAR input (GeoNRW). Bottom row: same datasets with left showing synthesized SAR input (GeoNRW) and right showing synthesized SAR input from the extended dataset (GeoNRW + Japan).

Figure 6.

Comparison of selected damage classification results in the BDD dataset using synthesized SAR images generated by SPADE from the GeoNRW and GeoNRW-Japan datasets.

Figure 7.

Comparison of selected damage classification results in the DFC2025 dataset using synthesized SAR images generated by SPADE-GAN from the GeoNRW and GeoNRW-Japan datasets.

For the BDD dataset, the model trained with authentic SAR exhibited the lowest performance across all damage categories, particularly for the moderate class. In contrast, the use of synthesized SAR significantly improved the classification results. The model using synthesized SAR generated from the GeoNRW + Japan dataset achieved the highest overall score (0.654), outperforming both the authentic SAR and the GeoNRW-only synthetic SAR configurations. This improvement suggests that the inclusion of diverse training scenes particularly from the Japan dataset enhances the generator’s ability to produce more realistic and generalizable SAR representations, ultimately benefiting downstream damage classification.

For the DFC2025 dataset, which was used to further validate model generalization, both synthetic SAR configurations achieved strong and consistent performance. Notably, the GeoNRW + Japan model again outperformed the GeoNRW-only model across all damage classes, achieving an overall score of 0.737. This result demonstrates the transferability of the synthesized SAR approach to previously unseen regions and supports the feasibility of using synthesized SAR as a substitute when authentic pre-disaster SAR imagery is unavailable.

Figure 5 presents the normalized per-building confusion matrices for both the BDD and DFC2025 datasets under different SAR input configurations. For per-building evaluation, pixel-wise predictions within each building footprint were aggregated using majority voting, and the resulting building-level labels were used to compute the confusion matrices. Consistent with the F1 results in Table 7, models using synthesized SAR (GeoNRW and GeoNRW + Japan) exhibit comparable or even improved classification performance relative to those using authentic SAR inputs.

For the BDD dataset, the authentic SAR model achieves strong performance for the destroyed class but tends to misclassify moderate damage as destroyed or survived. Incorporating synthesized pre-disaster SAR (GeoNRW) improves balance across classes, particularly increasing the correct identification of moderate damage. The GeoNRW + Japan variant further stabilizes predictions, reducing cross-class confusion and improving the consistency of survived vs. moderate separation.

For the DFC2025 dataset, both synthesized SAR settings yield highly accurate survived predictions (0.98) and maintain reliable discrimination of destroyed buildings. However, the moderate class remains the most challenging across all settings. This difficulty arises because moderate damage often represents an intermediate physical state that produces subtle or inconsistent backscattering changes in SAR imagery, making it visually and radiometrically similar to neighboring categories. From a SAR imaging perspective, slightly damaged buildings can either increase or decrease backscatter depending on geometric and structural changes. In particular, moderate damage may still preserve strong double-bounce returns, causing such buildings to appear similar to the survived class. Additionally, moderate damage samples are often underrepresented and subject to labeling inconsistencies, which further hinder model learning. Although slight structural deformations or rotations may occur, these changes are typically too minor to produce consistent backscatter variations in SAR intensity imagery, even with pre- and post-event data. Geometric distortions further obscure the detection of such intermediate damage states.

Overall, these results confirm that high-quality synthesized SAR can effectively substitute for authentic SAR in multimodal damage assessment. The GeoNRW + Japan configuration, trained on geographically diverse data, further enhances model robustness and inter-class balance across different regions.

7. Conclusions

In our experiments, we evaluated the use of synthesized pre-disaster SAR for multimodal building damage assessment across the BDD and DFC2025 datasets. The resulting scores (Table 7) and confusion matrices (Figure 5) consistently show that models incorporating synthesized SAR outperform those relying solely on authentic pre-disaster and post-disaster SAR settings. On the BDD dataset, authentic SAR yielded the lowest performance across all classes, particularly for the moderate damage category. In contrast, synthesized SAR especially the GeoNRW + Japan configuration achieved the highest overall score (0.654), indicating that geographically diverse training data improves SAR realism and downstream classification accuracy. On the DFC2025 benchmark, synthesized SAR again demonstrated strong generalization, with the GeoNRW + Japan model achieving an overall score of 0.737. These results confirm that synthesized SAR can effectively substitute for authentic pre-disaster SAR acquisitions, enabling reliable damage assessment even in regions where historical SAR coverage is unavailable. Aside from building damage assessment, the proposed SAR synthesis framework opens opportunities for other SAR-based remote sensing tasks where pre-disaster radar observations are scarce. Potential applications include flood mapping, landslide detection, coastline monitoring, urban change assessment, and general bitemporal SAR change detection. The framework could also support advanced classification and detection architectures in SAR-based tasks, such as transformer-based classifiers or multi-scale memory networks, further illustrating its broader applicability. Future work will focus on improving class imbalance performance (notably moderate damage), enhancing domain adaptation for cross-regional generalization, and extending the framework to additional hazard types and multitemporal settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y.H. and B.A.; methodology, C.Y.H. and B.A.; formal analysis, C.Y.H.; resources, G.B. and S.W.; data curation, C.Y.H.; writing—original draft, C.Y.H.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.H.; supervision, B.A., E.M., M.K. and S.K.; Project administration, S.K.; Funding acquisition: S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, 21H05001, 22K21372, and 22H01741) and the Cross ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP) (JPJ012289), and JST SICORP (JPMJSC2311). Magaly Koch’s work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. NSF-CNS 2420847: Collaborative Research: CPS: NSF-JST: Enabling Human-Centered Digital Twin for Community Resilience.

Data Availability Statement

The original data such as the DSM, optical, and SAR are publicly available in the following repositories: DFC2025 [https://zenodo.org/records/15385983, accessed on 24 December 2025] and DSM [https://www.gsi.go.jp/top.html,https://virtualshizuokaproject.my.canva.site/, accessed on 24 December 2025]. SAR StriX data are not publicy available and thus the commercial data were provided to us through a joint agreement between IRIDeS and Synspective.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Synspective Inc. for providing the SAR data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Gerald Baier was employed by the company Synspective Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Ge, P.; Gokon, H.; Meguro, K. A review on synthetic aperture radar-based building damage assessment in disasters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 240, 111693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Duan, J.; Liu, S.; Dai, Q.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y.; Guo, R.; Ma, C. Crowdsourcing rapid assessment of collapsed buildings early after the earthquake based on aerial remote sensing image: A case study of yushu earthquake. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, D.; Lemoine, G.; Bruzzone, L. Earthquake damage assessment of buildings using VHR optical and SAR imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2010, 48, 2403–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Adriano, B.; Mas, E.; Koshimura, S. New insights into multiclass damage classification of tsunami-induced building damage from SAR images. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, C.N.; Gokon, H.; Jimbo, M.; Koshimura, S.; Sato, M. Disaster debris estimation using high-resolution polarimetric stereo-SAR. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 120, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchiarulo, V.; Giardina, G.; Milillo, P.; Aktas, Y.D.; Whitworth, M.R. Integrating post-event very high resolution SAR imagery and machine learning for building-level earthquake damage assessment. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 23, 5021–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriano, B.; Mas, E.; Koshimura, S.; Gokon, H.; Liu, W.; Matsuoka, M. Developing a method for urban damage mapping using radar signatures of building footprint in SAR imagery: A case study after the 2013 Super Typhoon Haiyan. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 26–31 July 2015; pp. 3579–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriano, B.; Koshimura, S.; Karimzadeh, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Koch, M. Damage Mapping After the 2017 Puebla Earthquake in Mexico Using High-Resolution Alos2 Palsar2 Data. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2018—2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; pp. 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, S. 3D Synthetic Aperture Radar Simulation for Interpreting Complex Urban Reflection Scenarios. In Deutsche Geodätische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Dissertationen; Beck, R.C., Ed.; Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Munich, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, G.; Deschemps, A.; Schmitt, M.; Yokoya, N. Synthesizing Optical and SAR Imagery From Land Cover Maps and Auxiliary Raster Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4701312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Han, C.; Xia, J.; Yokoya, N. ChangeMamba: Remote Sensing Change Detection with Spatiotemporal State Space Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4409720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovo, R.; Adriano, B.; Wiguna, S.; Ho, C.Y.; Morales, J.; Dong, X.; Ishii, S.; Wako, K.; Ezaki, Y.; Mizutani, A.; et al. The 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake building damage dataset: Multi-source visual assessment. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 2025, 5259–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, W.; Yang, J.; Li, W. SAR Target Recognition Using cGAN-Based SAR-to-Optical Image Translation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, N.Y.D.; Shao, Z.; Altan, O. Remote Sensing and GIS Methods in Urban Disaster Monitoring and Management—An Overview. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 2019, 3, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Peng, G.H.; Yan, W.d.; Pan, L.L.; Wang, L.Y. Change detection in SAR images based on superpixel segmentation and image regression. Earth Sci. Inform. 2021, 14, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshimura, S.; Moya, L.; Mas, E.; Bai, Y. Tsunami damage detection with remote sensing: A review. Geosciences 2020, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriano, B.; Yokoya, N.; Xia, J.; Miura, H.; Liu, W.; Matsuoka, M.; Koshimura, S. Learning from multimodal and multitemporal earth observation data for building damage mapping. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 175, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citize; Molch, K. Radar Earth Observation Imagery for Urban Area Characterisation; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Inkawhich, N.; Inkawhich, M.J.; Davis, E.K.; Majumder, U.K.; Tripp, E.; Capraro, C.; Chen, Y. Bridging a Gap in SAR-ATR: Training on Fully Synthetic and Testing on Measured Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 2942–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Sun, B.; Zuo, Z. SAR image synthesis based on conditional generative adversarial networks. J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8093–8097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolenko, S.I. Synthetic Data for Deep Learning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, M.; McKinstry, A.; Maul, T.; Vu, T. Data augmentation approaches for satellite image super-resolution. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 4, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, R.; Deng, Y.; Jia, X.; Zhang, H. Rethinking the random cropping data augmentation method used in the training of CNN-based SAR image ship detector. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, R.; Yin, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, X. A review of data augmentation methods of remote sensing image target recognition. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2014), Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; Ghahramani, Z., Welling, M., Cortes, C., Lawrence, N., Weinberger, K., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.; Osindero, S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1411.1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zou, H.; Sun, L.; Cao, X.; He, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. CFRWD-GAN for SAR-to-optical image translation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Dong, Q. SAR-to-Optical Image Translation with Hierarchical Latent Features. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5233812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, T.C.; Zhu, J.Y. Semantic Image Synthesis with Spatially-Adaptive Normalization. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C.Y.; Neuschmidt, H.; Mas, E.; Adriano, B.; Koshimura, S. Building damage estimation using RaySAR, a Synthetic Aperture Radar simulator. In Proceedings of the XXVIII General Assembly of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG), Berlin, Germany, 11–20 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennison, A.; Lewis, B.; DeLuna, A.; Garrett, J. Convolutional and generative pairing for SAR cross-target transfer learning. Proc. SPIE 2021, 11728, 1172805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, G.F.; Machado, R.; Pettersson, M.I. A Tailored cGAN SAR Synthetic Data Augmentation Method for ATR Application. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf23), San Antonio, TX, USA, 1–5 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Li, Y. A SAR-to-Optical Image Translation Method Based on PIX2PIX. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, Brussels, Belgium, 11–16 July 2021; pp. 3026–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, S.; Bamler, R.; Reinartz, P. RaySAR—3D SAR simulator: Now open source. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Beijing, China, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 6730–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, H.; Schulz, K. Coherent simulation of SAR images. Proc. SPIE 2009, 7477, 74771G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.M.; Collins, M.J. SARSIM: A digital SAR signal simulation system. In Proceedings of the Remote Sensing and Photogrammetry Society Annual Conference, RSPSoc 2007, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 11–14 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Balz, T.; Stilla, U. Hybrid GPU-Based Single- and Double-Bounce SAR Simulation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 3519–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Luo, B.; Liu, J. Synthetic data augmentation using multiscale attention CycleGAN for aircraft detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 4009205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezaki, Y.; Ho, C.Y.; Adriano, B.; Mas, E.; Koshimura, S. Evaluation of Simulated SAR images for building damage classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 22, 4002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuny, S.; Schulz, K.; Hammer, H. Signature analysis of destroyed buildings in simulated high resolution SAR data. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium—IGARSS, Melbourne, Australia, 21–26 July 2013; pp. 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuny, S.; Hammer, H.; Schulz, K. Discriminating between the SAR signatures of debris and high vegetation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 26–31 July 2015; pp. 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuny, S.; Hammer, H.; Schulz, K. Assessing the Suitability of Simulated SAR Signatures of Debris for the Usage in Damage Detection. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, XLI-B3, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalathu, S.; Sun, H.; Nweke, C.C.; Yi, Z.; Burton, H.V. Classifying earthquake damage to buildings using machine learning. Earthq. Spectra 2020, 36, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajeb, M.; Karimzadeh, S.; Matsuoka, M. SAR and LIDAR datasets for building damage evaluation based on support vector machine and random forest algorithms—A case study of Kumamoto earthquake, Japan. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.C.; Tateishi, R.; Hara, K.; Nguyen, H.T.; Gharechelou, S.; Nguyen, L.V. Earthquake damage visualization (EDV) technique for the rapid detection of earthquake-induced damages using SAR data. Sensors 2017, 17, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Lee, C.C.; Mostafavi, A.; Mahdavi-Amiri, A. Large-scale building damage assessment using a novel hierarchical transformer architecture on satellite images. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 38, 2072–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wei, L.; Nguyen, M. Bitemporal attention transformer for building change detection and building damage assessment. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4917–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiguna, S.; Adriano, B.; Mas, E.; Koshimura, S. Evaluation of deep learning models for building damage mapping in emergency response settings. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 5651–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Hua, Z.; Li, J. Hybrid transformer-CNN networks using superpixel segmentation for remote sensing building change detection. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 2754–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Eineder, M. QuickQuakeBuildings: Post-Earthquake SAR-Optical Dataset for Quick Damaged-Building Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4011205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, G.; Deschemps, A.; Schmitt, M.; Yokoya, N. GeoNRW. 2020. Available online: https://ieee-dataport.org/open-access/geonrw (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Orzel, K.; Fujimaru, S.; Obata, T.; Imaizumi, T.; Arai, M. StriX-α SAR satellite: Demonstration of observation modes and initial calibration results. In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2022; 14th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, Leipzig, Germany, 25–27 July 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Dietrich, O.; Broni-Bediako, C.; Xuan, W.; Wang, J.; Shao, X.; Wei, Y.; Xia, J.; Lan, C.; et al. BRIGHT: A globally distributed multimodal building damage assessment dataset with very-high-resolution for all-weather disaster response. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.06019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Yokoya, N.; Adriano, B.; Broni-Bediako, C. OpenEarthMap: A Benchmark Dataset for Global High-Resolution Land Cover Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–7 January 2023; pp. 6243–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Y. Frechet Inception Distance (fid) for Evaluating Gans; China University of Mining Technology Beijing Graduate School: Beijing, China, 2021; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Horé, A.; Ziou, D. Image Quality Metrics: PSNR vs. SSIM. In Proceedings of the 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Istanbul, Turkey, 23–26 August 2010; pp. 2366–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, M.; Härkönen, E.; Lehtinen, J. E-lpips: Robust perceptual image similarity via random transformation ensembles. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.03973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. Vmamba: Visual state space model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 103031–103063. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.