Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A TransUNet-based deep learning framework was applied to multi-source satellite imagery (MODIS and SAR), achieving pixel-level ISW segmentation with a Dice coefficient of 71.0% and precision of 72.7%.

- The study generated the first 22-year (2002–2024) high-resolution spatiotemporal map of ISWs in the East China Sea, revealing two distinct hotspots and a significant summer peak in occurrence frequency.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The data-driven seasonal patterns align perfectly with the physics of internal tide generation body force, confirming stratification as the dominant control mechanism for ISW variability in this region.

- This study demonstrates the potential of Transformer-based models in mining massive historical remote sensing archives, providing an efficient tool for large-scale oceanographic big data analysis.

Abstract

The East China Sea (ECS) is a globally active region for internal solitary waves (ISWs); however, its overall spatiotemporal distribution remains poorly understood. To address this gap, this study proposes a deep learning method based on multi-source remote sensing imagery (MODIS and SAR) for the intelligent identification and pixel-level segmentation of ISWs in the ECS. We adopted the TransUNet model, which combines the global context-capturing capability of Transformers with the fine-grained segmentation advantages of U-Net to effectively handle the large-scale continuous characteristics of ISWs. The model achieved a Dice coefficient of 71.0% and a precision of 72.7% on the test set, significantly outperforming existing models such as FCN, SegNet, DeepLabV3+, and U-Net. Using this automated framework, multi-source satellite data from 2002 to 2024 were processed to generate the first high-resolution spatiotemporal map of ISWs covering the entire ECS. The map reveals two spatial hotspots: a primary one at the shelf break northeast of Taiwan and a secondary one in the waters southwest of Jeju Island. Furthermore, ISWs exhibit a marked seasonal cycle in both occurrence frequency and properties, peaking in summer and minimizing in winter. This seasonal pattern aligns closely with the physics of internal tide generation via body forcing. By providing the first long-term, high-resolution ISW dataset for the entire ECS, this study demonstrates the potential of deep learning techniques for ISW research in complex marginal seas.

1. Introduction

Internal solitary waves (ISWs) are nonlinear waves that occur in stably stratified oceans and are characterized by significant vertical displacements of the pycnocline [1]. As important carriers of momentum and energy, ISWs induce strong vertical shear and breaking of seawater flow, which transports nutrient-rich deep water to the euphotic zone, thereby promoting phytoplankton photosynthesis and playing a crucial role in local biogeochemical cycles. Additionally, during propagation, ISWs induce intense shear forces that pose serious threats to the safety of underwater vehicles and marine engineering facilities [2]. Owing to their multifaceted impacts on marine dynamic processes, ecosystems, and even military security, ISWs have become a key research topic in physical oceanography, marine engineering, and military applications.

Traditional in situ observation methods are limited by spatiotemporal coverage and costs, making them insufficient for large-scale, high-frequency ISW monitoring. Remote sensing technology, with its advantages of wide coverage and high revisit frequency, has become a major tool for ISW monitoring [3,4,5,6]. ISW propagation induces convergence and divergence of surface currents, thus modulating the distribution of sea surface microscale waves, changing sea surface roughness, and ultimately forming distinctive alternating bright and dark stripes in satellite images. Synthetic aperture radar (SAR, e.g., Sentinel-1) and optical sensors (e.g., MODIS) are two commonly used remote sensing data sources. Single-sensor data are often constrained by weather conditions (e.g., cloud interference in optical imagery) or imaging mechanisms (e.g., SAR sensitivity to specific wind speeds). Fusing multi-source remote sensing data from different sensors is expected to overcome the limitations of single data sources and enable comprehensive and accurate characterization of ISWs.

Starting from the traditional wavelet transform and edge discrimination [7,8], in recent years, artificial intelligence technologies represented by deep learning have developed rapidly, providing a new paradigm for the intelligent interpretation of complex marine phenomena in massive remote sensing images, and they have been widely applied to automated ISW identification tasks [9,10]. Among the various deep learning architectures, the TransUNet model [11] has recently emerged as a powerful tool. By integrating the self-attention mechanism of Transformers into the U-Net architecture, it overcomes the locality limitations of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), making it particularly suitable for capturing the global context of large-scale marine phenomena. Existing research in this field primarily focuses on two core directions: object-level detection and pixel-level segmentation. For object-level detection, researchers have used convolutional neural network (CNN) frameworks such as Faster Region-Based CNN (R-CNN) and You Only Look Once (YOLO) to automatically localize and classify ISWs in SAR images [12,13]. Other studies have constructed models using deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) to realize effective detection in multiple single-sensor datasets [10,14]. For more precise pixel-level segmentation, methods based on fully convolutional networks can not only accurately outline the morphology of ISWs but also have been applied to their temporal evolution analysis [15].

To further improve segmentation performance, recent studies have integrated attention mechanisms into U-Net-like architectures. For instance, Cai et al. (2024) [16] and Zhang et al. (2023) [10] proposed specialized models that incorporate attention modules (such as SE or CBAM blocks) to enhance feature selection and suppress background noise. These methods have successfully demonstrated that attention mechanisms can boost the identification of ISWs in complex backgrounds. Nevertheless, despite the significant progress made in the aforementioned studies, deep learning-based ISW identification still faces challenges. First, there is insufficient integration of heterogeneous multi-source information. Most existing models rely on single-sensor data, verifying ‘generalizability’ across datasets rather than achieving true ‘information fusion’. Simply concatenating data from sensors with different physical properties (e.g., SAR backscatter and visible light reflectance) at the channel or feature level fails to fully exploit their complementary information. For instance, while optical data offers high temporal resolution, it is often obscured by weather conditions, whereas SAR provides all-weather capabilities despite its lower temporal resolution [17]. This superficial fusion cannot effectively leverage these complementary physical characteristics. Second, existing network structures have limitations in capturing global contextual information. As large-scale marine phenomena, the accurate segmentation of ISWs depends not only on local textures but also on the effective perception of long-range spatial dependencies; however, the limited receptive field of traditional CNNs hinders their ability to effectively capture such large-scale dependencies [18]. This often results in incomplete segmentation of large, continuous ISW packets.

The East China Sea (ECS), as an important marginal sea of the western Pacific, features complex seabed topography and strong tidal forcing, making it an active region for ISWs. The sea area northeast of Taiwan has long been identified as a key ISW generation site in the ECS [4,19,20]. Satellite images and in situ observations show that ISWs here propagate in multiple directions, with amplitudes up to 50 m [4,19]. Subsequent numerical simulation studies have found that ISWs in this region can be generated by the interaction between local barotropic tides and topography, as well as the shoaling-induced fission of internal tides generated at the I-Lan Ridge during northward propagation.

In addition to the area northeast of Taiwan, frequent ISW activities have also been observed south of Jeju Island [21,22,23] and near the Yangtze River Estuary [24,25]. Based on typical MODIS images, Zhu et al. (2022) found that ISWs in the Jeju Island area exhibit relatively fixed spacing, indicating that they are generated by the periodic interaction between tidal currents and topography [22]. Using extensively collected MODIS data, Lee et al. (2024) found that ISWs south of Jeju Island can be roughly divided into three different propagation paths, each corresponding to a distinct ISW generation source [23]. Near the Yangtze River Estuary, ISW processes have been further studied in recent years using satellite data and in-situ observations [24,25,26]. Although these studies have advanced our understanding of ISWs in the ECS, their findings are spatially scattered and discontinuous, focusing mostly on specific potential hotspot regions. Compared with other well-studied ISW-prone regions like the South China Sea [27,28,29,30], the Sulu Sea, and the Andaman Sea [31,32,33], a systematic and complete spatiotemporal distribution map of ISWs covering the entire ECS is still lacking.

To address the above challenges and fill the gap in regional research, this study proposes an intelligent ISW identification and segmentation method for the ECS based on multi-source remote sensing imagery. Specifically, the TransUNet model is adopted, combining the advantages of Transformers for capturing long-range global dependencies and U-Net for fine-grained local segmentation, thereby enabling more effective identification of large-scale marine phenomena such as ISWs. Using this model, we will systematically identify and segment ISWs in the ECS, and finally generate a spatiotemporal distribution map of ISWs in the ECS and analyze their seasonal variation characteristics, aiming to provide a more complete data landscape and an efficient analytical tool for in-depth understanding of ISW activity patterns in this region.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Data Sources

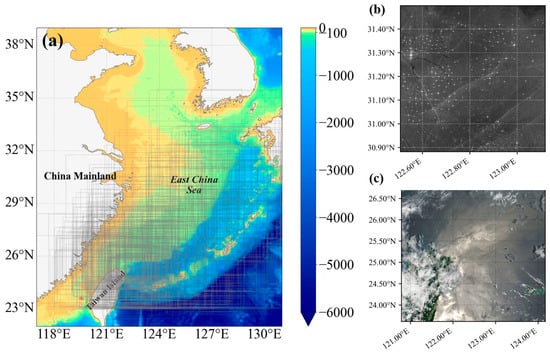

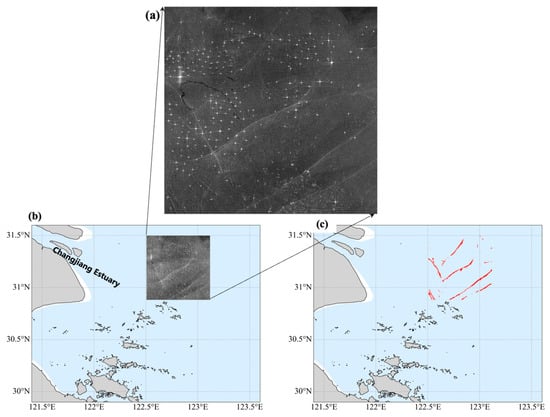

To comprehensively capture the remote sensing characteristics of ISWs under different conditions, this study uses two types of data sources: synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and optical remote sensing imagery. Figure 1b,c show typical SAR and MODIS images of ISWs in the study area, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Bathymetric map of the East China Sea (ECS) (data from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, water depth in m), where the gray box indicates the imaging area of the remote sensing satellite. (b) VV-polarized Sentinel-1 image acquired on 1 August 2024 (Greenwich Mean Time, GMT); (c) Aqua MODIS image acquired on 27 July 2005 (GMT). These panels are intended to display raw data examples and formats and do not necessarily represent the primary internal solitary waves (ISW) hotspot regions, which are analyzed in Section 4.

SAR data were obtained from the Sentinel-1 satellite of the European Space Agency (ESA). We selected its Interferometric Wide Swath (IW) mode Ground Range Detected (GRD) products, which have a swath width of 250 km and typically feature a range resolution of 5 m and an azimuth resolution of 20 m (with a 10 m × 10 m pixel spacing). For the convenience of subsequent multi-source data fusion, all SAR images were resampled to a 250 m resolution. While this resampling matches the resolution of MODIS data to facilitate consistent processing, it inevitably limits the detection of small-scale ISWs (e.g., wave widths < 250 m). However, since this study focuses on the macroscopic spatiotemporal distribution of energetic ISWs in the ECS—which typically feature scales of kilometers—this resolution is sufficient for the intended analysis. Equipped with a C-band radar, Sentinel-1 enables all-weather and day-and-night observations, making it an ideal data source for monitoring ISWs under complex sea conditions. In this study, VV polarization was selected over VH polarization due to its higher sensitivity to sea surface roughness variations induced by ISW-modulated surface currents, which results in higher contrast and clearer imaging of ISW signatures. After screening, a dataset consisting of 253 VV-polarized images (2014–2024) with clear ISW features was finally constructed in this study.

Optical data were obtained from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites. This study used its 250 m resolution Corrected Reflectance products, and true-color images were generated by combining the red (Band 1), green (Band 4), and blue (Band 3) bands. To build a high-quality dataset, a strict screening process was developed: first, images with cloud coverage exceeding 80% during the study period were automatically excluded; second, manual visual interpretation was performed on the remaining images, and finally 243 Terra images (2002–2024) and 309 Aqua images (2002–2024) were selected, totaling 552 images with clear ISW features.

To address the potential issue of insufficient model training due to limited labeled data in the study area (ECS) and to improve the model’s generalization, this study introduced a transfer learning strategy. We used the large-scale ISW dataset of the northern South China Sea constructed by Zhang et al. (2024) for pre-training [29]. The core idea of this strategy is: first, use the massive and diverse ISW samples in the South China Sea dataset to enable the TransUNet model to learn general ISW morphologies and texture features. This transfer learning strategy is effective because ISWs, despite occurring in different marginal seas, share universal morphological features, such as characteristic quasi-linear stripe patterns and similar spatial scales; second, fine-tune the pre-trained model using the ECS dataset constructed in this study. This “pre-training-fine-tuning” paradigm aims to transfer knowledge from large-scale datasets to the target region, enabling the model to better adapt to the remote sensing characteristics of the ECS and achieve higher identification accuracy with limited labeled data.

2.1.2. Dataset Construction and Pixel-Level Labeling

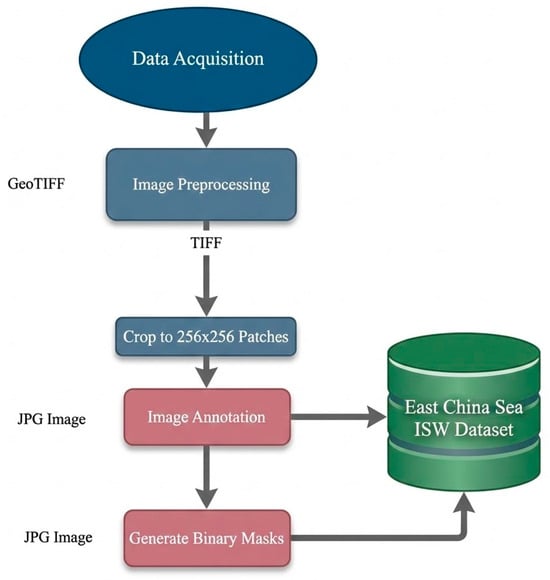

The workflow for dataset construction and pixel-level labeling in this study is illustrated in Figure 2 and comprises three key stages: data preprocessing, format conversion, and manual annotation.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the image dataset, including preprocessing, standardization, and manual annotation steps.

Original remote sensing images were first preprocessed according to their sensor type. For SAR data, inherent speckle noise was suppressed via initial filtering; this was followed by radiometric calibration to normalize backscatter intensity and subsequent geocoding to project the data into a geographic coordinate system. For MODIS optical data—already subjected to preliminary correction—processing focused on unifying file formats and projections. All preprocessed images were ultimately converted to TIFF format, which retains critical geographic information.

Next, data augmentation and manual annotation were implemented to optimize the training dataset. To expand the sample size and improve model generalization, preprocessed images were subjected to a random-cropping augmentation strategy. The resulting JPG-format image patches were then annotated pixel-by-pixel with high precision using the open-source tool LabelMe (version 5.0.1) [34], ensuring clear delineation of complete ISW wave packets or distinct wave crests. Finally, all annotation data were converted to PNG-format binary segmentation masks: ISW regions were assigned a pixel value of 255, while background regions were set to 0. These masks served as the ground truth for model training and performance evaluation. To derive geometric properties such as crest length from the prediction results (Figure 2), a post-processing workflow was applied. This involved morphological skeletonization to extract the one-pixel-wide centerlines of ISW crests, followed by connected component analysis (8-connectivity) to identify and measure individual wave objects.

2.1.3. Data Augmentation

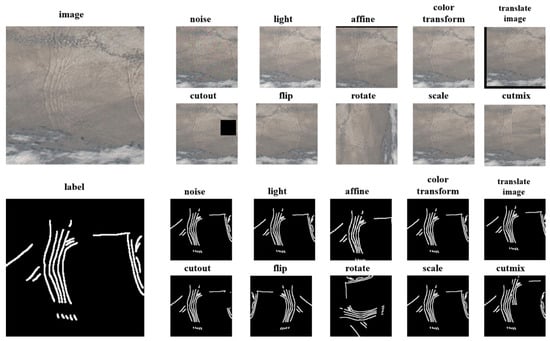

To expand the training dataset and enhance the model’s generalization, multiple online data augmentation techniques were integrated into the training phase. These methods were designed to simulate the diverse morphologies and imaging variations of ISWs encountered in real-world remote sensing scenarios, with specific operations visualized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Examples of data augmentation for images and labels. Taking a 256 × 256 pixel MODIS image as an example: the upper row shows the images, and the lower row shows their corresponding segmentation masks. The left column represents the original data, and the right column shows the results after the combined application of geometric transformation (e.g., random rotation), radiometric transformation (e.g., contrast adjustment), and regional regularization methods (e.g., Cutout).

Three core augmentation categories were implemented: geometric transformation, radiometric transformation, and regional regularization.

For geometric transformation, random horizontal/vertical flipping and rotation were employed to mimic the varied propagation directions of ISWs in the ocean. Random scaling was also applied to adapt the model to ISW morphologies across different scales and spatial resolutions.

Radiometric transformation involved random adjustments to image brightness and contrast, simulating varying solar glint conditions in optical imagery and differing backscatter intensities in SAR data. Notably, Gaussian noise was intentionally injected into SAR images to strengthen the model’s robustness against inherent speckle noise.

Within regional regularization, two key methods were adopted. One is Cutout [35]: a random rectangular region within the image was selected and filled with zeros or random noise, simulating local information loss caused by small cloud patches or sensor artifacts. This operation preserved the original label and aimed to improve the model’s ability to identify ISWs even when parts of the target were occluded. The other is Cutmix [36]: a patch was randomly cropped from another training image and pasted onto the current image, replacing the original region; critically, the corresponding label mask was modified identically. This forces the model to interpret mixed information from two distinct sources (either two ISW targets or a target and background) within a single input, significantly enriching the training data distribution, effectively suppressing overfitting, and prompting the model to learn more generalized associations between features and contexts.

The combined application of these techniques substantially boosted training data diversity, reduced the risk of model overfitting, and enabled the model to learn deep features that are less sensitive to variations in illumination, direction, noise, and local information.

2.2. Model

2.2.1. TransUNet

ISWs in marine remote sensing images typically exhibit large-scale, continuous structures, and their accurate segmentation relies heavily on understanding long-range spatial contexts. Traditional segmentation models, such as fully convolutional networks (FCNs) and U-Nets, are based on cascaded convolutional operations. While CNNs excel at extracting local features like edges and textures, their receptive fields are limited by the size of their convolution kernels, inherently restricting their focus to local information. This limitation prevents CNNs from capturing global dependencies of large-scale targets like ISWs, thereby limiting segmentation performance.

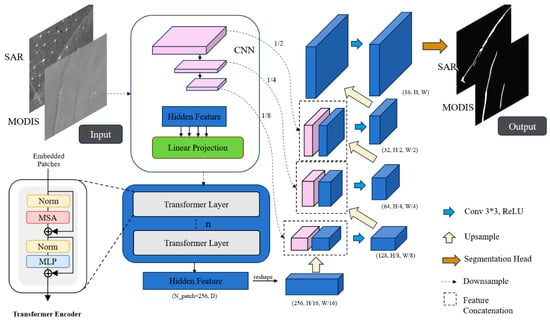

To overcome the locality constraint of CNNs, this study adopts the TransUNet model [11,37], whose architecture is shown in Figure 4. TransUNet innovatively combines the global self-attention mechanism of Transformers with the classic encoder–decoder structure of U-Net. Its core lies in a hybrid encoder design: Input remote sensing images first pass through a CNN backbone (e.g., ResNet-50) for multi-scale local feature extraction. Deep feature maps generated by the CNN are flattened into serialized patch embeddings, which are then fed into the Transformer module. It is important to note that the model architecture is designed to handle single-channel inputs; therefore, SAR and optical images are processed separately rather than being fused simultaneously at the input level. This ensures that the model can robustly operate even when only one type of data source is available. Here, the self-attention mechanism calculates the correlation weights between any two patches in the image, effectively capturing global contextual information about large-scale structures, such as overall ISW morphologies. In the decoding phase, the model uses cascaded upsampling operations and skip connections from the CNN encoding path to gradually restore the spatial resolution of feature maps, ultimately achieving precise pixel-level segmentation of ISWs.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the TransUNet model. The model adopts a hybrid encoder–decoder framework. In the encoding path, 256 × 256 input images undergo local feature extraction via a CNN backbone (ResNet-50), then are fed into the Transformer module to capture long-range global dependencies. In the decoding path, cascaded upsampling gradually restores spatial resolution, and skip connections effectively fuse fine spatial details preserved by the CNN with global contextual information generated by the Transformer, ultimately outputting pixel-level ISW segmentation results. Although a MODIS image is shown as the input example, the processing workflow for Sentinel-1 SAR images is identical. Color coding is as follows: pink blocks represent feature maps extracted by the CNN backbone, while blue blocks represent upsampled feature maps in the decoder. In the expanded Transformer Encoder view (bottom left), yellow, red, and light blue blocks denote Normalization, Multi-Head Self-Attention (MSA), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) layers, respectively.

2.2.2. Model Training Optimization

Model training and optimization were guided by a composite loss function designed to address two key challenges inherent to this ISW segmentation task. First, ISWs occupy only a small fraction of the image, resulting in a severe imbalance in pixel counts between the foreground (ISW regions) and the background. Second, the segmentation task demands high precision for ISW wave crest boundaries to ensure accurate morphological characterization. To simultaneously address these two challenges, a hybrid loss function combining Dice and Focal losses was adopted.

Dice loss is an overlap-based loss metric that excels at handling class imbalance issues. It directly optimizes segmentation performance by maximizing the Dice coefficient—a quantitative measure of similarity between two sets—between the model’s predicted segmentation mask and the ground truth label. The Dice coefficient is defined as follows:

Dice loss is then calculated as follows:

where X denotes the set of predicted mask pixels, Y denotes the set of ground truth label pixels, is the number of overlapping pixels between the two sets, and and are the total number of pixels in X and Y, respectively.

Focal loss is designed to address the imbalance between easy-to-classify and hard-to-classify samples in ISW segmentation, serving as an optimized improvement over the standard Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss. The BCE loss, which forms the basis for Focal loss, is defined as follows:

where y ∈ {0,1} is the ground truth label, and p is the model’s predicted probability that a pixel belongs to the foreground (y = 1).

Focal loss introduces a modulation factor , which enables the model to automatically allocate more attention to hard-to-classify pixels (e.g., pixels at blurry ISW boundaries) during training. Its formula is given as follows:

where is the model’s predicted probability for the true class, is a factor for balancing class weights, and is a focusing parameter—larger values increase the model’s focus on hard-to-classify samples. In this study, to effectively balance the positive and negative samples and focus on hard examples, we set the balancing factor to 0.25 and the focusing parameter to 2, following standard practices.

Combining the advantages of Dice loss (optimizing regional overlap) and Focal loss (focusing on hard samples), the total loss function was defined as a linear combination of the two:

where λ is a weight hyperparameter balancing the contributions of the two losses. This composite loss function addresses foreground–background imbalance while improving the model’s segmentation precision for ISW boundary details.

2.3. Experimental Setup

To ensure reproducibility, all model training and testing procedures were carried out in a standardized hardware and software environment. The hardware setup relied on a high-performance workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with 16 GB of video random access memory (VRAM). For software, the environment was configured with Windows 10 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), PyTorch 1.12.1 (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), and CUDA 11.3 (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) for GPU acceleration.

The constructed dataset comprised 805 images, which were randomly split into training, validation, and test sets at an 8:1:1 ratio. Key hyperparameters for model training were configured as follows: we selected the AdamW optimizer, which decouples weight decay from gradient updates and typically delivers better generalization performance than the standard Adam optimizer. For the learning rate strategy, a compound scheduling approach was adopted. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01. A warmup mechanism was used in early training stages, followed by a cosine annealing strategy to realize smooth learning rate decay.

The batch size was set to 16, a value chosen to balance GPU memory constraints and the stability of the training process. The total number of training epochs was set to 100. To prevent overfitting and save training time, an early stopping mechanism was introduced: if the core performance metric on the validation set did not improve for 20 consecutive epochs, training would be terminated early. Ultimately, the model weights that yielded the best performance on the validation set were saved and used for subsequent evaluation.

3. Model Training Results

3.1. Analysis of Model Result Metrics

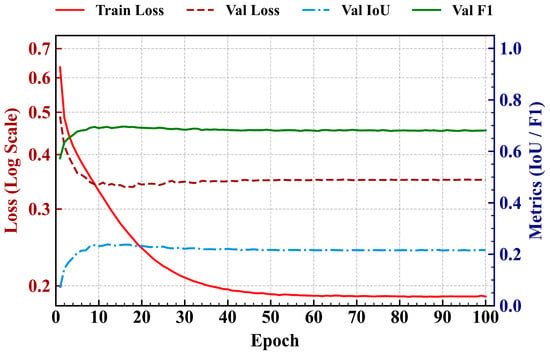

To evaluate the TransUNet model’s learning dynamics and convergence during ISW segmentation, we visualized and analyzed key training metrics, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Training dynamics and performance metrics of the TransUNet model on the ECS dataset. The plot displays the evolution of training loss (red solid line) and validation loss (brown dashed line) referenced to the left logarithmic axis. The validation performance metrics, including Intersection over Union (IoU, blue dash-dot line) and F1-score (green solid line), are referenced to the right axis.

The loss function convergence (Figure 5) shows that the model’s loss curves followed an ideal trend. Training loss dropped sharply over the first 40 epochs, indicating that the model efficiently learned ISW features from the dataset. After roughly 50 epochs, the training loss stabilized at around 0.19, indicating gradual convergence. Meanwhile, validation loss decreased rapidly during early training, reaching its minimum (approximately 0.34) at epoch 25, and then slightly increased and stabilized near 0.35. A small, stable gap existed between training and validation losses, and validation loss did not see continuous significant increases—this points to strong model generalization, as regularization strategies (e.g., weight decay and data augmentation) effectively suppressed severe overfitting.

We used the F1-score as the core metric to evaluate segmentation performance on the validation set. As shown, the F1-score rose rapidly in the first 20 epochs, closely matching the phase of rapid loss reduction (Figure 5). At around epoch 20, it peaked at 0.695, then fluctuated slightly around 0.68 and stabilized.

A combined analysis of Figure 5 reveals that the model’s optimal performance point occurred in the early training stage (approximately epochs 20–25). During this period, validation loss reached its minimum, and the F1-score peaked—fully demonstrating the model quickly grasped the key discriminative features of ISWs and achieved optimal generalization performance, as evidenced by the rapid stabilization of validation loss and metrics. This observation also provides strong data support for the adopted early stopping mechanism: it mitigates the risk of overfitting from slight overfitting in later training stages, ensuring we obtain the final optimal segmentation model.

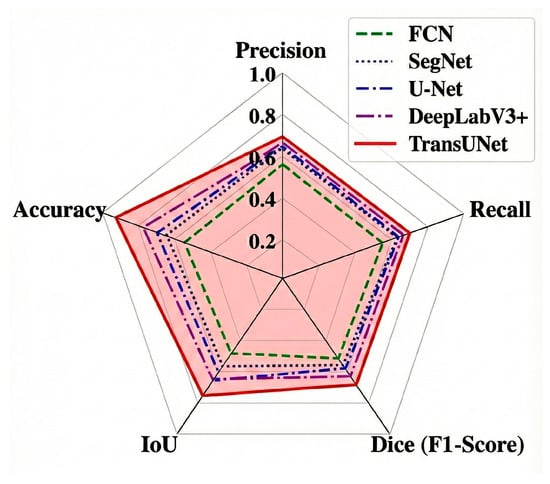

3.2. Model Performance Comparative Analysis

To evaluate the TransUNet model’s performance in ISW segmentation, four representative deep learning models in semantic segmentation were selected as baseline comparators: fully convolutional network (FCN), segmentation network (SegNet), U-Net (Ronneberger et al., 2015) [38], and DeepLabV3+. FCN pioneered end-to-end pixel-level prediction; SegNet features an efficient encoder–decoder architecture; U-Net excels at fine-grained segmentation with its skip-connection structure; and DeepLabV3+ employs atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP) to robustly capture multi-scale contextual information.

As presented in Table 1, TransUNet outperformed all baseline models across all four evaluation metrics, underscoring its superior capability in ISW segmentation. Specifically, it achieved the highest Dice coefficient (F1-Score) of 0.710 and an IoU of 0.246. Notably, its precision reached 72.7%, indicating that the model maintains a high level of reliability in identifying true ISW pixels while suppressing false positives.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different models on the ECS test set.

Compared with DeepLabV3+ (the strongest baseline among the comparators), TransUNet still delivered a solid performance gain, improving the Dice coefficient by 2.4 percentage points (from 0.686 to 0.710) and boosting the IoU by approximately 9.3% in relative terms (from 0.225 to 0.246).

To provide a more intuitive evaluation of the comprehensive model capabilities, a radar chart visualization is presented in Figure 6. As illustrated, the performance profile of TransUNet (represented by the red solid line) completely encloses the baseline models (including the advanced DeepLabV3+), exhibiting the largest coverage area. This visualization highlights that TransUNet does not merely excel in a single metric but achieves a robust balance between Precision and Recall, while maintaining a clear lead in the critical Dice and IoU metrics. This “enveloping” performance confirms its robustness in handling the complex, multi-scale features of ISWs compared to traditional CNN-based architectures.

Figure 6.

Radar chart comparing the segmentation performance of FCN, SegNet, U-Net, DeepLabV3+, and TransUNet across five key metrics: precision, recall, Dice (F1-Score), IoU, and accuracy. The TransUNet model (red solid line) consistently encloses the baseline models, demonstrating superior comprehensive performance and a balanced trade-off between precision and recall.

It is important to note that, unlike general objects, ISWs appear as extremely thin, linear features in satellite imagery. In such scenarios, minor spatial deviations (e.g., 1–2 pixels) can significantly penalize overlap-based metrics like IoU and Dice, even if the morphological structure is correctly identified. Therefore, the Dice score of 0.710 represents a high level of structural agreement and morphological integrity.

FCN, SegNet, U-Net, and DeepLabV3+ were selected as baseline models because they represent the foundational milestones in the evolution of semantic segmentation architectures. However, these CNN-based models are inherently limited by their local receptive fields. Although DeepLabV3+ expands the receptive field via ASPP, it is still constrained by the locality of convolution operations. As large-scale continuous marine phenomena, accurate ISW segmentation relies not only on local features (e.g., edges and textures) but also on a global understanding of overall morphology. While U-Net effectively fuses multi-scale local features via skip connections, it lacks direct modeling of long-range spatial dependencies. In contrast, the Transformer module in TransUNet captures correlations between any two image regions through self-attention, constructing true global contextual representations. This enables it to effectively address issues like discontinuous segmentation or sensitivity to weak background interference—problems U-Net may encounter when processing large targets.

In summary, the quantitative results demonstrate that TransUNet is an ideal choice for high-precision intelligent ISW segmentation in the ECS, providing a robust balance between precision and recall.

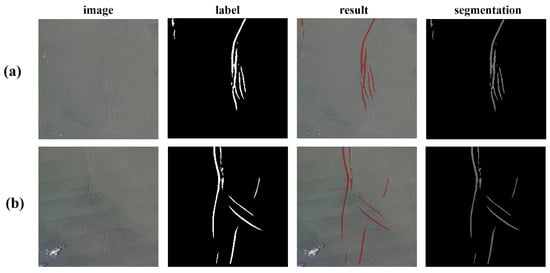

3.3. Visualization Results

Beyond quantitative metric evaluation, visualization analysis of typical test samples was conducted to more intuitively demonstrate the model’s segmentation capabilities and clarify the sources of its performance advantages. Figure 7 presents the model’s segmentation results for two representative groups of ISW images. A comprehensive analysis of these cases reveals three key capabilities of the model:

Figure 7.

Segmentation results of the TransUNet model on two sets of typical MODIS images. Rows (a,b) show segmentation cases for ISWs with different morphologies. Columns from left to right: original image, ground truth label, model prediction result (red overlay), and final binary segmentation map.

First, it exhibits excellent fine-structure preservation, enabling it to distinguish and retain independent, subtle wave crest structures within complex wave packets. Second, by leveraging the Transformer module to overcome the limited receptive field of traditional CNNs, the model maintains spatial continuity and morphological integrity of segmentation results when processing large-scale curved ISW morphologies, generating coherent segmentation masks. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 7b, the image exhibits significant striping artifacts; the segmentation results confirm that the model can effectively extract ISW features from such noisy backgrounds without being severely affected.

Despite its strong performance, the model is subject to uncertainties regarding false positives and false negatives. False positives may occasionally arise from cloud edges in optical images or distinct oceanic fronts in SAR images that mimic ISW stripes. False negatives are primarily associated with weak-amplitude ISWs that have very low contrast relative to the background sea. In cases with highly blurred wave-crest boundaries, the segmentation results may exhibit local discontinuities or reduced boundary smoothness. Notably, even experienced manual interpreters struggle with these challenging samples. Thus, these limitations do not undermine the model’s overall effectiveness but rather reflect a natural decline in fine segmentation performance under extreme signal-to-noise ratio conditions. Even in such cases, the model’s output can still serve as valuable identification cues.

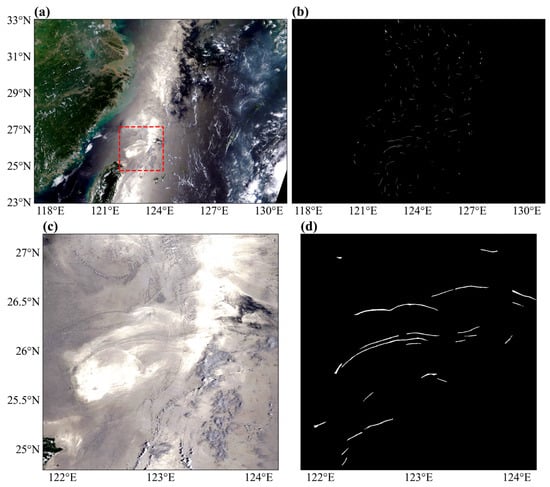

3.4. Large-Scale Image Stitching and Model Application Verification

After verifying the model’s segmentation accuracy on standard 256 × 256-pixel image patches, we further evaluated its ability to process complete, wide-area satellite images—a critical step in transforming the model from a technical verification tool into a practical scientific analysis tool. The evaluation relied on a systematic workflow for large original images: patch segmentation, ISW identification, and result stitching. This workflow aimed to test the model’s robustness in real, complex scenarios and the integrity of its stitching outcomes.

Figure 8 presents the model’s segmentation results applied to a full MODIS image covering the extensive sea area of the East China Sea (acquired on 1 August 2024). As shown in the original image (Figure 8a), this scene exhibits complexities inherent to real marine environments, including varying levels of cloud coverage and intense solar glint. The model’s stitched output (Figure 8b) successfully and automatically extracts multiple ISW groups across the entire image.

Figure 8.

Large-scale segmentation application of the TransUNet model on a complete MODIS image (Aqua satellite, 1 August 2024): (a) MODIS true-color image, with the red dashed box indicating the locally enlarged area; (b) identified ISW labels in the entire image; (c) image of the enlarged area; (d) final binary segmentation result of the enlarged area.

Local magnification regions northeast of the Taiwan island (Figure 8c,d) clearly demonstrate that the model still accurately identifies ISW morphologies even in the vicinity of solar glint. This outcome strongly confirms that the model—trained on small-scale image patches—possesses excellent generalization capability, enabling its successful extension to large-scale, complex scenarios with high background noise. More importantly, the complete segmentation of this single large image enables the systematic identification of the spatial distribution patterns of ISW groups across different geographical locations at the same timestamp.

Unlike optical images (e.g., MODIS), SAR imagery is free from constraints imposed by clouds or illumination, enabling all-weather and day-and-night observations. However, its inherent speckle noise introduces a distinct challenge to accurate ISW identification. Figure 9 shows the example SAR imagery result near the Changjiang Estuary. The ISWs near the Changjiang Estuary are characterized by much shorter crests. Our model effectively mitigates the interference of such noise, successfully extracting the main ISW structures from the noisy background. The resulting segmentation outputs exhibit clear boundaries and continuous morphological integrity, further validating the model’s robustness to the unique noise characteristics of SAR data. The ISWs in the example image mostly propagate northwestward. A few ISWs also propagate northeastward, indicating the presence of multiple propagation pathways. This implicates the multiple generation sites of ISWs near the Changjiang Estuary.

Figure 9.

Segmentation results of the TransUNet model on a Sentinel-1 image (1 August 2024): (a) location of the VV-polarized SAR image; (b) enlarged SAR image; (c) ISW segmentation result from model identification, where the identified ISW wave crests are highlighted in red.

We note that recently, studies have been carried out by researchers such as Zhang et al. (2023) and Cai et al. (2024) [10,16] to optimize deep learning models for internal wave identification. These studies successfully improved the traditional U-Net by incorporating attention mechanisms (e.g., SE or CBAM modules), which effectively enhance feature representation by focusing on salient local regions. In contrast, the TransUNet architecture employed in our study represents a distinct paradigm. By leveraging the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism to capture long-range global dependencies, it offers a robust advantage in maintaining the morphological integrity of continuous ISW structures. A direct comparative analysis of these divergent deep learning strategies holds significant value for advancing internal wave identification research. We look forward to conducting rigorous comparative benchmarking with them in our future follow-up research. Nevertheless, the successful stitching and validation of large-scale images in this section demonstrate that the automated workflow developed in this study functions as an efficient and reliable tool for extracting information from massive archives of historical remote sensing data.

4. Results and Discussion: Spatiotemporal Distribution of ISWs

4.1. Spatial Distribution

After verifying the model’s effectiveness, the automated framework was applied to years of satellite images to extract and geocode ISW location, morphology, and distribution from each valid image. These results were integrated to reveal the overall spatiotemporal distribution patterns of ISWs in the ECS. Using the TransUNet model constructed in this study, a high-resolution dataset of ECS ISW wave crests was generated.

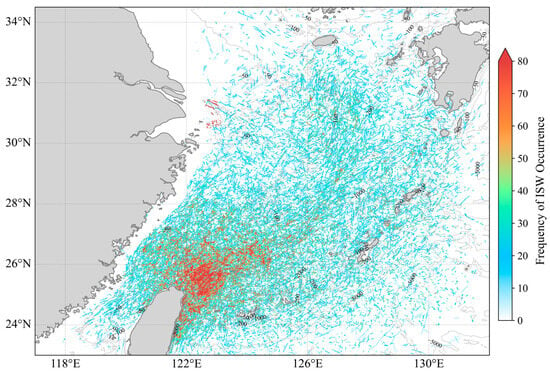

By spatiotemporally superimposing all identified wave crests, the resulting ISW spatial distribution frequency map (Figure 10) reveals that ISW activity in the ECS is not randomly distributed but concentrated in specific hotspot areas. The shelf break zone northeast of Taiwan (approximately 25.0°N–27.5°N, 122.0°E–124.0°E) stands out as the most intense ISW hotspot across the entire ECS. As shown in Figure 10, the wave crests of these ISWs are primarily oriented northeast–southwest; from the curvature of the wave crests, it can be inferred that the ISWs propagate mainly northwestward, from the steep shelf break toward the shallow shelf. This aligns with the typical identification results of ISWs northeast of Taiwan presented in Figure 8, where the identified wave crests reach 102.94 km in length. This finding is also consistent with previous satellite observations in this sea area (e.g., Figure 13 in Duda et al., 2013) [19]. The underlying mechanism involves the interaction between strong barotropic M2 tides and complex seabed topography. This interaction converts substantial energy into baroclinic energy, exciting intense internal tides. These internal tides then evolve nonlinearly into ISW wave packets as they propagate toward the shelf. Beyond the dominant northwestward-propagating ISWs, Figure 10 also captures ISWs propagating in multiple other directions in this sea area—highlighting the complexity of ISW generation mechanisms here.

Figure 10.

Spatial distribution frequency map of ISWs in the ECS generated from the model identification results. The map is created by superimposing all identified ISW wave crests during the study period, with a spatial resolution of 250 m. The color scale represents the cumulative occurrence count (frequency) of ISW detections at each pixel, clearly revealing the ISW activity hotspot northeast of Taiwan. Gray contours represent seabed topographic isobaths.

The sea area south of Jeju Island is another key ISW hotspot in the ECS (Figure 10). Unlike the concentrated generation source northeast of Taiwan, wave crests here are more dispersed, and their propagation directions (inferred from curvature) are diverse. This complex distribution feature, derived from the data-driven model, corroborates the latest findings in physical oceanography. Through MODIS image analysis, Lee et al. (2024) decomposed ISWs in this region into three types with distinct propagation directions [23]. They identified their unique generation sources: northwestward-propagating waves from the northern Okinawa Trough, westward-propagating waves from the southwest of Fukue Island, and southward-propagating waves from the southwest of Jeju Island. The diverse wave crest pattern identified by our model also reflects this complex generation mechanism.

Although previous studies have observed frequent ISW activity near the Yangtze River Estuary [24], and our results in Figure 10 also show some activity in this area, our targeted identification did not classify it as a significant hotspot. One potential explanation for this discrepancy is the limited satellite observation data available for the Yangtze River Estuary (Figure 1), which warrants further in-depth analysis.

4.2. Seasonal Variation

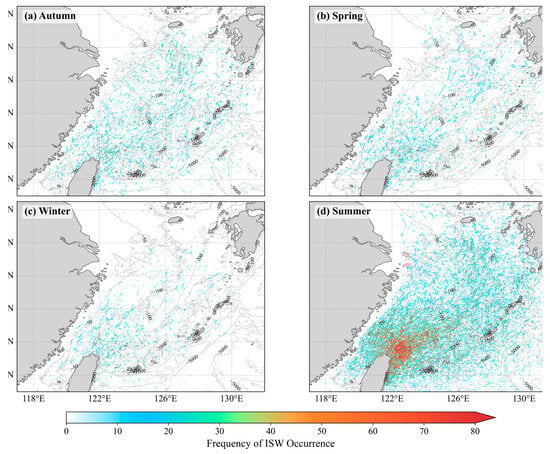

The occurrence frequency of ISWs in the ECS exhibits a distinct seasonal cycle, as shown in Figure 11. Statistical analysis reveals that ISW detection frequency peaks in summer (June–August), is moderate in spring (March–May) and autumn (September–November), and drops to its annual minimum in winter (December–February). The intense ISW hotspot northeast of the Taiwan Island is evident across all four seasons, with this pattern being most distinct in summer (Figure 11d).

Figure 11.

Seasonal distribution of ISW occurrence frequency in the ECS: (a) Autumn (September–November), (b) Spring (March–May), (c) Winter (December–February), and (d) Summer (June–August). The color scale represents the frequency of ISW occurrences. Results show a strong seasonal signal, with the highest activity in summer and the lowest in winter.

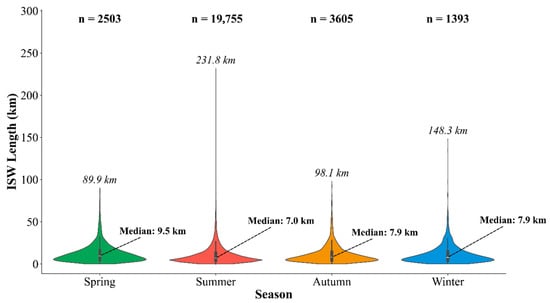

The ECS is characterized by seasonal stratification, especially in the shelf area. In summer, the region develops a highly stable and prominent seasonal pycnocline; this strong stratification acts as an ideal “waveguide,” facilitating the effective generation and long-distance propagation of internal tides. These internal tides then undergo nonlinear evolution into high-frequency ISWs that are detectable by satellites. The summer peak in ISW activity identified by our model aligns with the physical background of maximum seawater stratification intensity in the ECS. Beyond this seasonal variation in occurrence frequency, Figure 12 further details the statistical distribution of ISW crest lengths, revealing a more complex relationship between wave quantity and scale. Although ISW crests exhibit a similar typical (median) length (7–10 km) across all four seasons, the stable summer ‘waveguide’ conditions facilitate the formation of extreme outliers, with maximum crest lengths reaching 231.8 km.

Figure 12.

Seasonal characteristics of ISWs. The plot shows the seasonal length distribution (violin plots, Y-axis) overlaid with the total occurrence frequency (n) for each season. Annotations indicate the median and maximum observed ISW lengths (km).

Strong convection and wind forcing in winter erode or even completely disrupt the seasonal pycnocline established in summer, leading to vertically homogeneous seawater—especially in shelf areas [39]. This strong vertical mixing causes the buoyancy frequency to approach zero. According to Equation (6), the internal tide generation body force is directly proportional to ; thus, a vanishing leads to a negligible body force, effectively shutting down the generation mechanism of internal tides and ISWs. This directly explains why the model detects almost no ISW in the ECS main shelf with water depth shallower than 100 m during winter (Figure 11c). The moderate ISW activity observed in spring and autumn accurately reflects the “intermediate state” of the marine stratification environment: stratification is neither fully established (as in summer) nor completely absent (as in winter).

4.3. Internal Tide Generation Body Force

To better understand the ISW generation sources and the seasonal variability, the vertical integral formula for internal tide generation body force in the ECS was further calculated as follows [40]:

where is the M2 tidal angular frequency (rad s−1), is the vertical direction (with at the sea surface and positive upward), is the total water depth, is the squared buoyancy frequency varying with the depth, and is the barotropic tidal flux (i.e., , where and are the zonal and meridional barotropic velocity, respectively.

Bathymetric data were obtained from the ETOPO1 dataset provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) [41]. The data of the M2 barotropic tide were acquired from the TPXO9 global tide model based on the Oregon State University Tidal Inversion Software (OTIS) [42]. The squared buoyancy frequency N2 was calculated with the climatological mean of temperature and salinity data from the World Ocean Atlas 2023 (WOA23) [43]. The original data of temperature, salinity, and barotropic tide are uniformly interpolated on a grid of 1/4° resolution, yielding the seasonal variation map of the spatial maximum of the internal tide generation body force in the ECS.

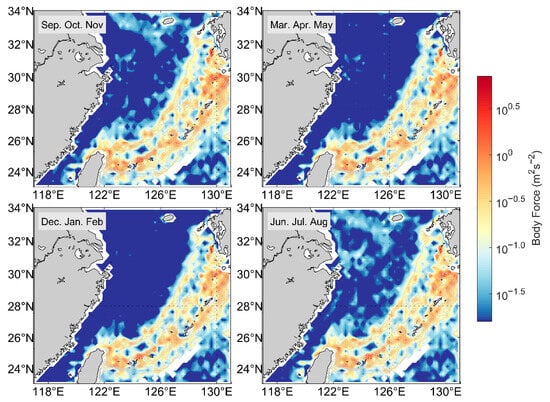

The internal tide generation body force is produced when tidal currents interact with steep topography, creating unbalanced horizontal pressure gradients that drive ISWs. This concept has been widely applied in ISW research across various marine regions [20,44]. The ECS is dominated by M2 internal tides [45]; thus, the M2 tidal component-induced internal tide generation body force was calculated to identify major ISW generation sites in the ECS. As shown in Figure 13, high values of internal tide generation body force are primarily concentrated in sea areas with dramatic topographic changes, such as the ECS shelf slope and the Ryukyu Island chain. This corresponds to the high M2 semidiurnal tidal energy conversion rates in these areas [45].

Figure 13.

Seasonal distribution of internal tide generation body force in the ECS. This physical diagnostic parameter (F) integrates tidal effects, topographic gradients, and marine stratification intensity to identify potential generation sources of internal tides and ISWs. The figure shows the seasonal body force distribution corresponding to autumn (Sep, Oct, Nov), spring (Mar, Apr, May), winter (Dec, Jan, Feb), and summer (Jun, Jul, Aug), as labeled in each panel. The color scale represents the magnitude of body force F (unit: m2s−2).

Furthermore, the internal tide generation body force exhibits significant seasonal variations, most notably in shelf seas (water depth < 200 m). Its magnitude peaks in summer, moderates in spring and autumn, and becomes negligible in winter. Barotropic tide data are prescribed only as sinusoidal oscillations; long-period variabilities (e.g., seasonal or interannual changes) are excluded. Thus, enhanced internal tide generation body force in summer and autumn occurs only when oceanic stratification intensifies. This variation pattern matches the seasonal variation of ISWs identified by our model. The seasonal variation of ISW occurrence frequency driven by stratification changes is consistent with characteristics observed in other marine regions, such as the South China Sea [29,46], Sulu Sea [31,47], and Andaman Sea [32].

5. Conclusions

Aiming to address the lack of systematic, large-scale observations of ISWs in the ECS, this study extensively collected Sentinel-1 satellite images (2014–2024) and MODIS Terra/Aqua images (2002–2024) to construct a long-term, high-resolution ISW dataset for the region. Based on this dataset, the TransUNet deep learning framework was applied for automated identification and segmentation of multi-source remote sensing imagery. The TransUNet model effectively handles the complexity of remote sensing images, achieving high-precision, pixel-level segmentation of ISW wave crests in the ECS. The segmentation results maintain the continuity and integrity of ISW morphologies while resolving internal structures of complex wave packets, successfully constructing a spatiotemporal ISW dataset with precise geographic location information. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model performs exceptionally well in identifying ISWs in the ECS, achieving a Dice coefficient of 71.0%, precision of 72.7%, and other metrics that outperform those of comparative models.

Using the TransUNet model’s identification results from multi-year MODIS and Sentinel-1 data, this study systematically generated the first ISW spatial distribution map covering the entire ECS. The results clearly identify two core hotspots of ISW activity in the ECS: the most intense activity is concentrated in the shelf break zone northeast of Taiwan. In contrast, a more dispersed activity area is located on the northern ECS shelf southwest of Jeju Island. The model’s identification results also reveal a distinct seasonal cycle of ISW activity in the ECS, with the highest occurrence frequency in summer and near-absence in winter. This purely data-driven finding shows consistency with the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of the physics-based internal tide generation body force. In ISW hotspots like the South China Sea and the Andaman Sea, ISWs exhibit relatively well-defined generation zones, consistent propagation directions, and uniformly long wave crest lines. In contrast, the East China Sea is characterized by diverse ISW generation sources, shorter wave crests, and variable propagation directions, resulting in significantly more complex ISW systems overall. This work highlights the value of deep learning in extracting complex marine signals from multi-source remote sensing data, laying a solid foundation for more efficient and accurate ISW monitoring in regions with complex ISW systems. Furthermore, it provides a methodological reference for advancing understanding of internal wave dynamics and refining related research frameworks in complex ISW-prone marginal seas worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X. and W.Y.; methodology, J.X. and R.S.; software, J.X. and T.Y.; validation, J.X., X.L. and R.S.; formal analysis, J.X. and T.Y.; investigation, J.X. and X.L.; resources, W.Y. and H.W.; data curation, X.L. and J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.X.; writing—review and editing, W.Y. and H.W.; visualization, J.X.; supervision, W.Y. and H.W.; project administration, W.Y.; funding acquisition, W.Y. and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42276009, and the Open Fund Project of the Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Information Technology, Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China.

Data Availability Statement

(1) The MODIS true-color imagery was obtained from NASA’s Worldview portal, available at https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 20 November 2024). (2) The Sentinel-1 SAR data were obtained from the Alaska Satellite Facility (ASF), available at https://search.asf.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 20 November 2024). (3) The MODIS pre-training dataset was obtained from the “Internal Solitary Wave Spatial Position Dataset 1.0”, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.12157/IOCAS.20240409.001 (accessed on 20 November 2024). (4) The SAR pre-training dataset was obtained from the “S1-IW-2023 Dataset”, available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11090328 (accessed on 20 November 2024). (5) Bathymetric data were obtained from the ETOPO1 Global Relief Model, available at https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/ (accessed on 15 August 2025). (6) Climatological temperature and salinity data were obtained from the World Ocean Atlas 2023 (WOA23), available at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-atlas (accessed on 15 August 2025). The derived high-resolution ECS ISW dataset generated and analyzed in this study is not publicly available due to its proprietary nature as a laboratory asset. Requests for access to this derived dataset should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECS | East China Sea |

| ISWs | Internal Solitary Waves |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FCN | Fully Convolutional Network |

| SegNet | Segmentation Network |

| ASPP | Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling |

| TransUNet | Transformer-based U-Net |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| BCE | Binary Cross-Entropy |

| GRD | Ground Range Detected |

| IW | Interferometric Wide Swath |

| VV | Vertical–Vertical (polarization) |

| GMT | Greenwich Mean Time |

| VRAM | Video Random Access Memory |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| WOA23 | World Ocean Atlas 2023 |

| TPXO | TOPEX/Poseidon Global Tidal Model |

References

- Osborne, A.R.; Burch, T.L. Internal solitons in the Andaman Sea. Science 1980, 208, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrova, O.Y.; Mityagina, M.I.; Serebryany, A.N.; Sabinin, K.D.; Kalashnikova, N.A.; Krayushkin, E.V.; Khymchenko, I. Internal waves in the Black Sea: Satellite observations and in-situ measurements. In Proceedings of the Remote Sensing of the Ocean, Sea Ice, Coastal Waters, and Large Water Regions 2014; SPIE: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 9240, pp. 248–260. [Google Scholar]

- Alpers, W. Theory of radar imaging of internal waves. Nature 1985, 314, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-K.; Liu, A.K.; Liu, C. A study of internal waves in the China Seas and Yellow Sea using SAR. Cont. Shelf Res. 2000, 20, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. Internal wave detection using the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS). J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, C004220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.R. An empirical model for estimating the geographic location of nonlinear internal solitary waves. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2009, 26, 2243–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenas, J.A.; Garello, R. Internal wave detection and location in SAR images using wavelet transform. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1998, 36, 1494–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, D.; Tatnall, A.R.; Robinson, I.S. The automated detection and recognition of internal waves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 4581–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, B.; Zheng, G.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, F. Deep-learning-based information mining from ocean remote-sensing imagery. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1584–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Internal wave signature extraction from SAR and optical satellite imagery based on deep learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4203216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Meng, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. Detection of ocean internal waves based on Faster R-CNN in SAR images. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2020, 38, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Xu, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y. An internal waves data set from Sentinel-1 synthetic aperture radar imagery and preliminary detection. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2022EA002528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Cai, Z.; Yang, X. IWResNet-MA: A deep learning framework for extracting internal wave stripe and propagation direction from SAR imagery. Ocean Eng. 2025, 328, 121030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Qi, K.; Zhang, H. Stripe segmentation of oceanic internal waves in synthetic aperture radar images based on Mask R-CNN. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 14480–14494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hu, W.; Yan, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X. Automatic Extraction of Internal Wave From Complex Background Using Polarimetric SAR and Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barintag, S.; An, Z.; Jin, Q.; Chen, X.; Gong, M.; Zeng, T. MTU2-Net: Extracting internal solitary waves from SAR images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Wen, X.; Li, X.; Dong, H.; Zang, S. Learning a 3D-CNN and Convolution Transformers for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, T.; Newhall, A.; Gawarkiewicz, G.; Caruso, M.; Graber, H.; Yang, Y.; Jan, S. Significant internal waves and internal tides measured northeast of Taiwan. J. Mar. Res. 2013, 71, 47–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, W.; Wei, H.; Jiang, C.; Liu, C.; Zhao, L.; Liu, H.; Yang, W.; Wei, H.; Jiang, C.; et al. On characteristics and mixing effects of internal solitary waves in the northern Yellow Sea as revealed by satellite and in situ observations. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lozovatsky, I.; Jang, S.; Jang, C.J.; Hong, C.S.; Fernando, H.J.S. Episodes of nonlinear internal waves in the northern East China Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L18601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Yang, W.; Jiang, C.; Wang, T.; Wei, H. Observations of turbulent mixing and vertical diffusive salt flux in the Changjiang Diluted Water. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2022, 40, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Nam, S.; Noh, S. New generation site and estimated propagation of nonlinear internal waves under varying background stratification in the northeastern East China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2024, 129, e2024JC021497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Han, Z.; Xu, L. Internal solitary waves in the East China Sea. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2008, 27, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Wei, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J. Turbulence and vertical nitrate flux adjacent to the Changjiang Estuary during fall. J. Mar. Syst. 2020, 212, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhang, W.; Lin, F.; Xie, X.; Zhou, F. Observations of intense turbulent mixing by unsteady mode-2 internal lee waves off the Yangtze River Estuary. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2025, 130, e2025JC022410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, M.H.; Peacock, T.; MacKinnon, J.A.; Nash, J.D.; Buijsman, M.C.; Centurioni, L.R.; Chao, S.-Y.; Chang, M.-H.; Farmer, D.M.; Fringer, O.B.; et al. The formation and fate of internal waves in the South China Sea. Nature 2015, 521, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.A.; Chen, L.; Xiong, X.J. Research frontiers and highlights of internal waves in the South China Sea. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2022, 40, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X. Constructing a 22-year internal wave dataset for the northern South China Sea: Spatiotemporal analysis using MODIS imagery and deep learning. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 5131–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, L.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Cai, S. Strong hazardous internal waves in the South China Sea and along the maritime silk road. Adv. Earth Sci. 2025, 40, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X. Combination of satellite observations and machine learning method for internal wave forecast in the Sulu and Celebes Seas. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 2822–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhou, L.; He, S.; He, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, A.K.; Hsu, M.K. Distribution of internal waves in the Andaman Sea and its adjacent waters based on multi-satellite remote sensing data. J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, Q. A machine-learning model for forecasting internal wave propagation in the Andaman Sea. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 9387–9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.C.; Torralba, A.; Murphy, K.P.; Freeman, W.T. LabelMe: A database and web-based tool for image annotation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2008, 77, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, T.; Taylor, G.W. Improved regularization of convolutional neural networks with Cutout. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.04552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Han, D.; Chun, S.; Oh, S.J.; Yoo, Y.; Choe, J. CutMix: Regularization strategy to train strong classifiers with localizable features. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6022–6031. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, K.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z. Strip segmentation of oceanic internal waves in SAR images based on TransUNet. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2023, 42, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Q.; Mao, X.; Yang, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, W. Seasonal variations of several main water masses in the southern Yellow Sea and East China Sea in 2011. J. Ocean Univ. China 2013, 12, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, P.G. On internal tide generation models. Deep Sea Res. Part A 1982, 29, 307–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amante, C.; Eakins, B.W. ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model: Procedures, Data Sources and Analysis; NOAA Technical Memorandum NESDIS NGDC-24; National Geophysical Data Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert, G.D.; Erofeeva, S.Y. Efficient inverse modeling of barotropic ocean tides. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2002, 19, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagan, J.R.; Boyer, T.P.; García, H.E.; Locarnini, R.A.; Baranova, O.K.; Bouchard, C.; Cross, S.L.; Mishonov, A.V.; Paver, C.R.; Seidov, D.; et al. World Ocean Atlas 2023; NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.C.B.; New, A.L.; Magalhaes, J.M. Internal solitary waves in the Mozambique Channel: Observations and interpretation. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2009, 114, C05001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; Guo, J.; Wei, H. Energetics and variability of semidiurnal internal tides across the East China Sea shelf: Local generation versus remote forcing. Prog. Oceanogr. 2025, 238, 103563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Hu, J. Generation sites of internal solitary waves in the southern Taiwan Strait revealed by MODIS true-colour image observations. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 4086–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yang, J.; Ma, Z.; Liu, B.; Ren, L.; Liu, A.K.; Chen, P. Generation of diurnal internal solitary waves (ISW-D) in the Sulu Sea: From geostationary orbit satellites and numerical simulations. Prog. Oceanogr. 2024, 225, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.