A Spike-Inspired Adaptive Spatial Suppression Framework for Large-Scale Landslide Extraction

Highlights

- A two-phase framework is proposed utilizing a PCA-based candidate extraction strategy to eliminate massive background objects and alleviate extreme sample imbalance at the data level.

- A Spike-inspired Landslide Extraction Model is developed, incorporating a spike-inspired sparse attention module (SISA) and mix-scale feature aggregation (MSFA) to adaptively suppress background noise and enhance blurred landslide boundaries.

- The framework provides a robust solution for large-scale landslide extraction, effectively overcoming the challenges of data imbalance and complex background interference.

- Integrating biologically inspired SNN sparse activation mechanisms into deep learning offers a promising new approach for accurate landslide extraction and mitigating background confusion in remote sensing.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We propose a PCA-based landslide candidate extraction method to remove extensive background regions at the data level, improving class balance and reducing irrelevant background noise, which facilitates more accurate large-scale landslide extraction.

- (2)

- A spike-inspired landslide extraction method is developed for large-scale applications. It incorporates a spike-inspired sparse attention module (SISA) to adaptively suppress background interference and a mix-scale feature aggregation module (MSFA) to enhance attention to weak and fragmented landslide features, providing a robust and precise solution for landslide extraction across large-scale and complex geological regions.

2. Datasets

2.1. Hengduan Mountains, China

2.2. Hokkaido, Japan

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Landslide Candidate Extraction

3.2. Spike-Inspired Landslide Extraction Model

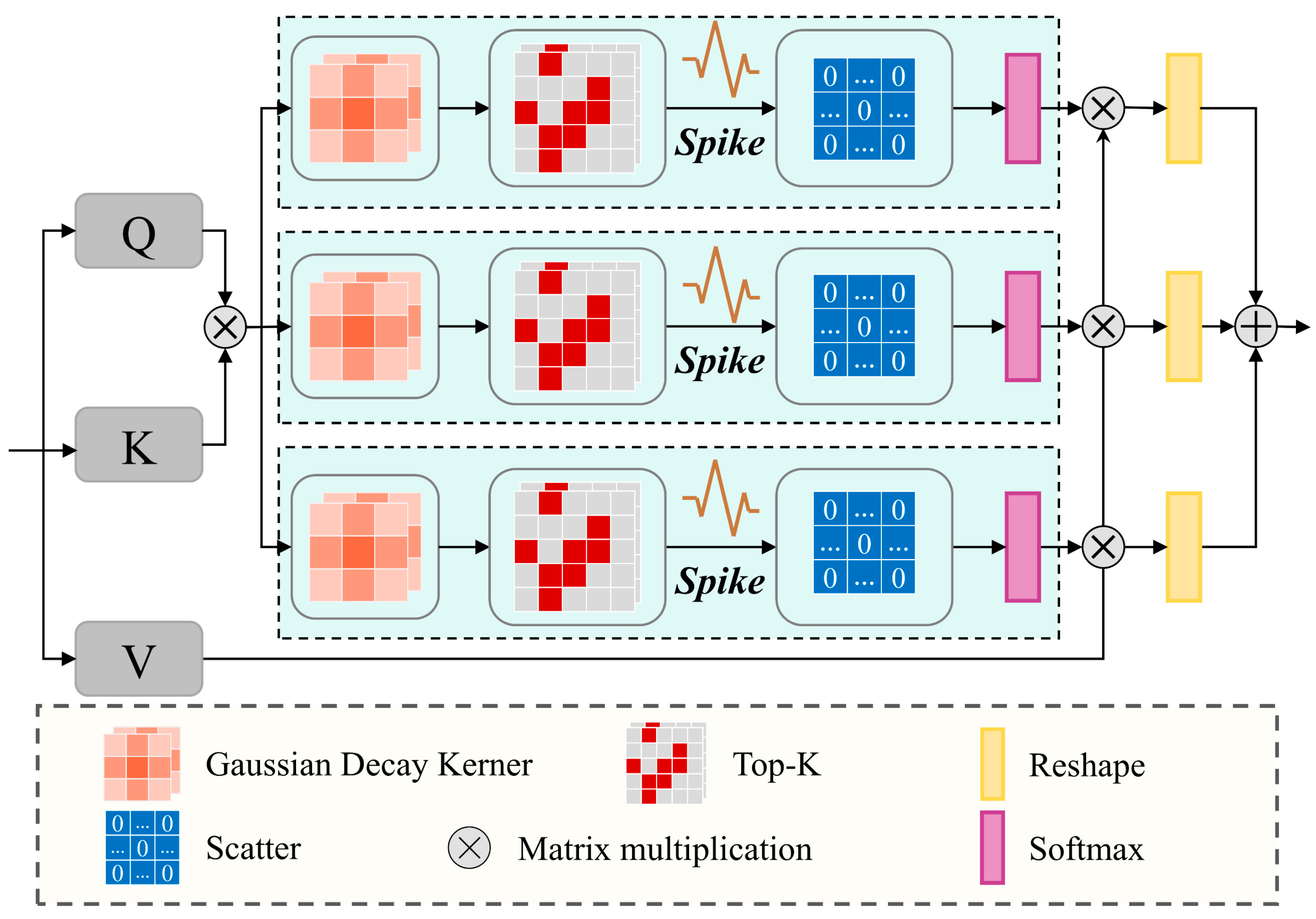

3.2.1. Spike-Inspired Sparse Attention Module (SISA)

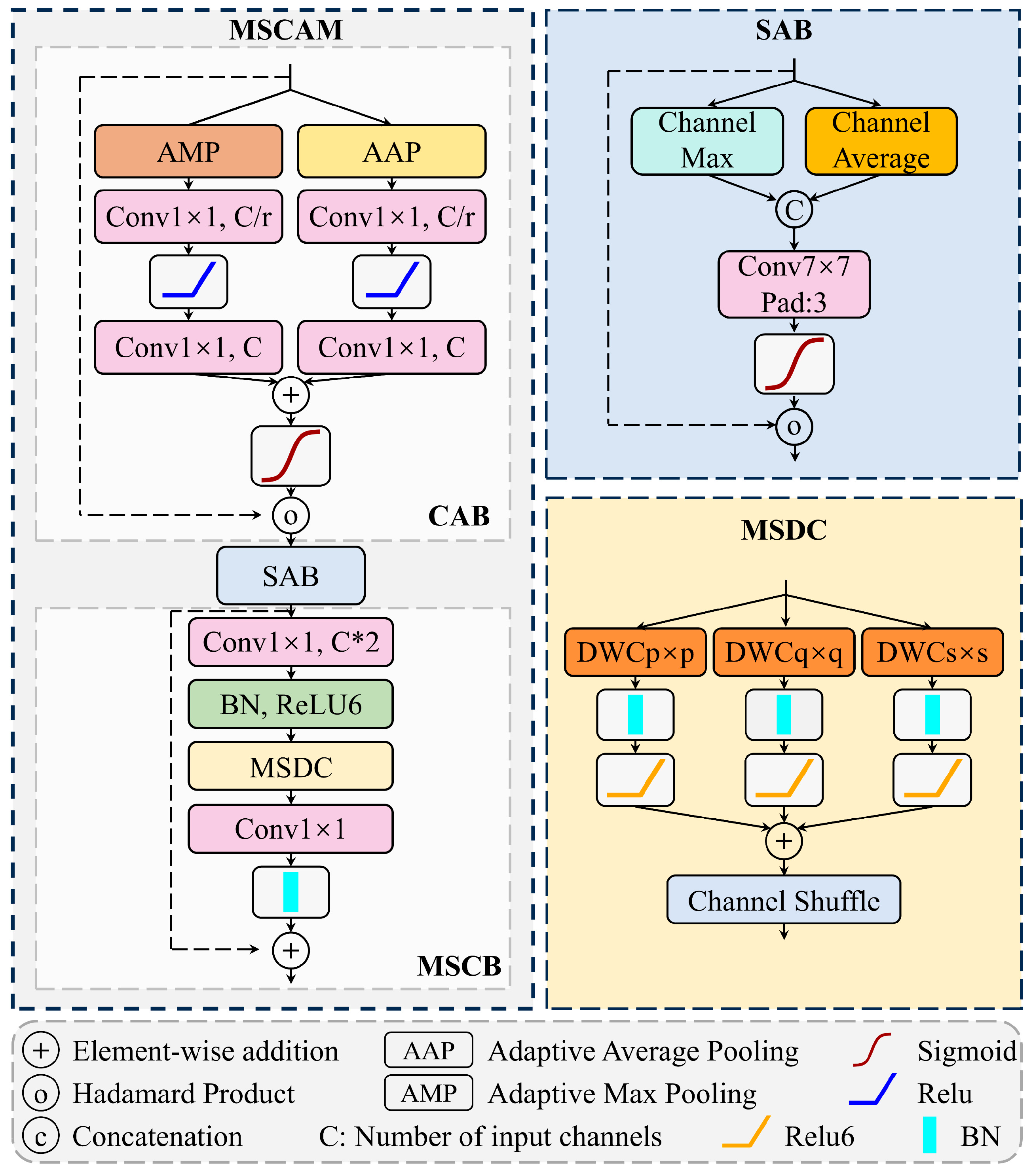

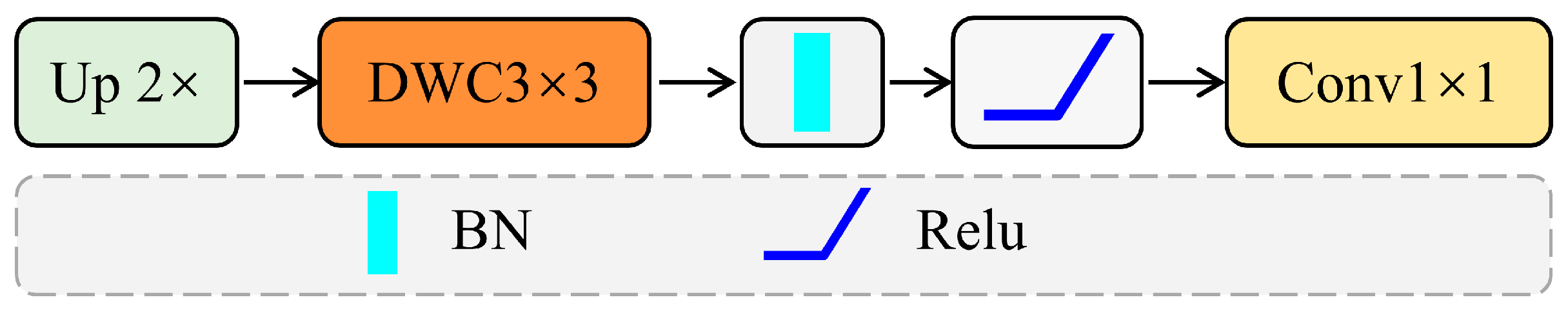

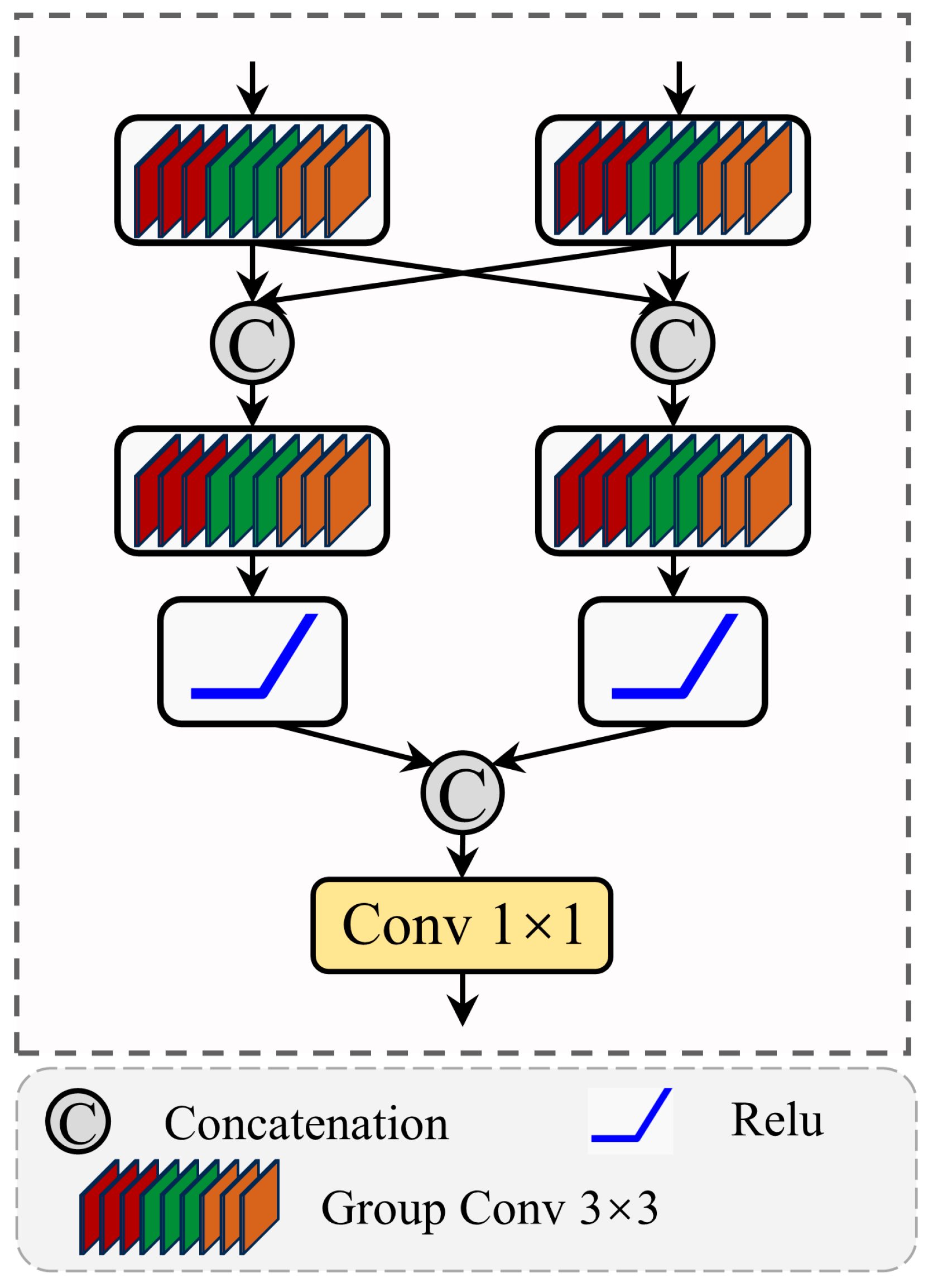

3.2.2. Multi-Scale Fusion Decoder

4. Experiment

4.1. Image Preprocessing

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Implementation Details

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

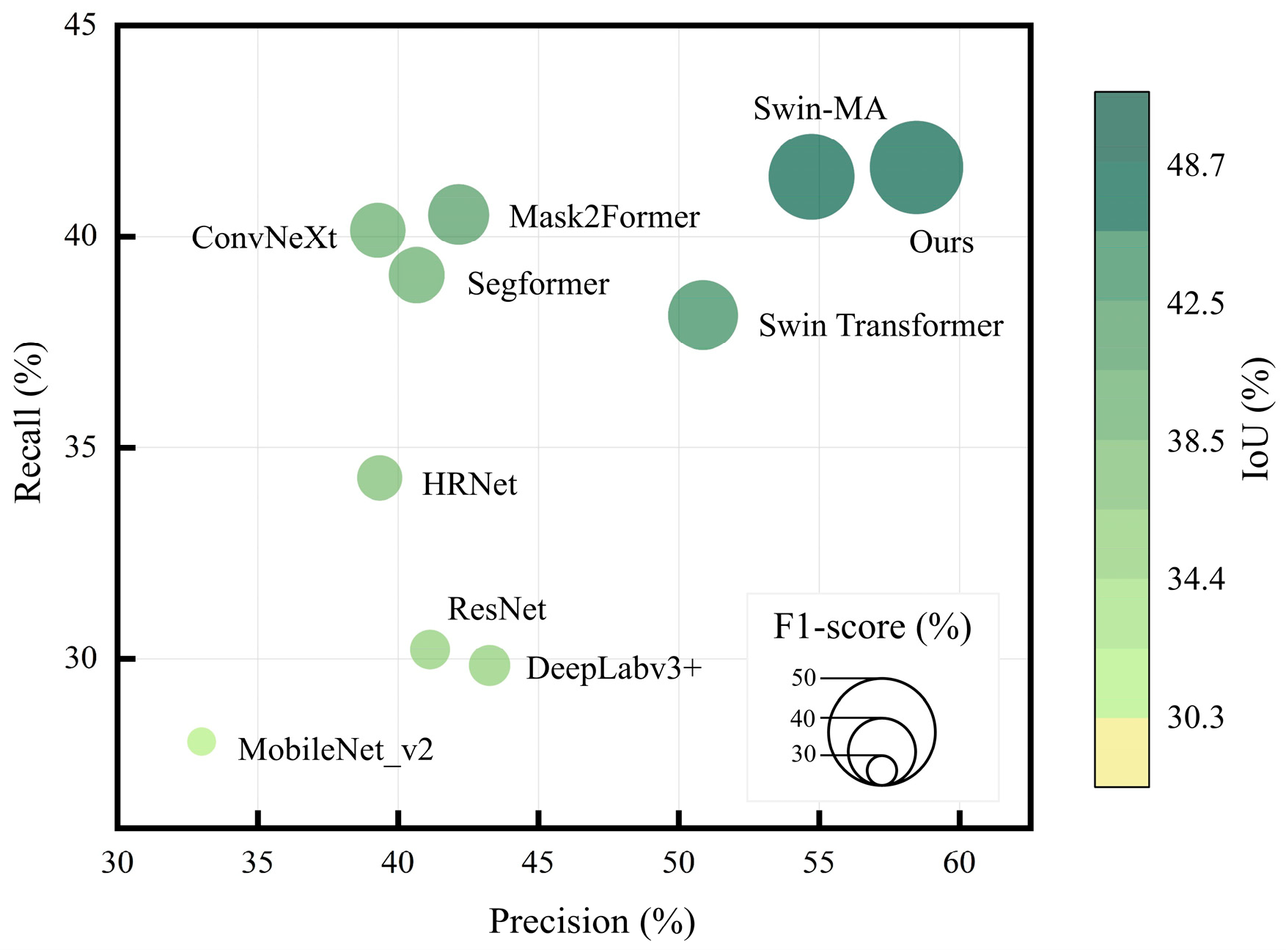

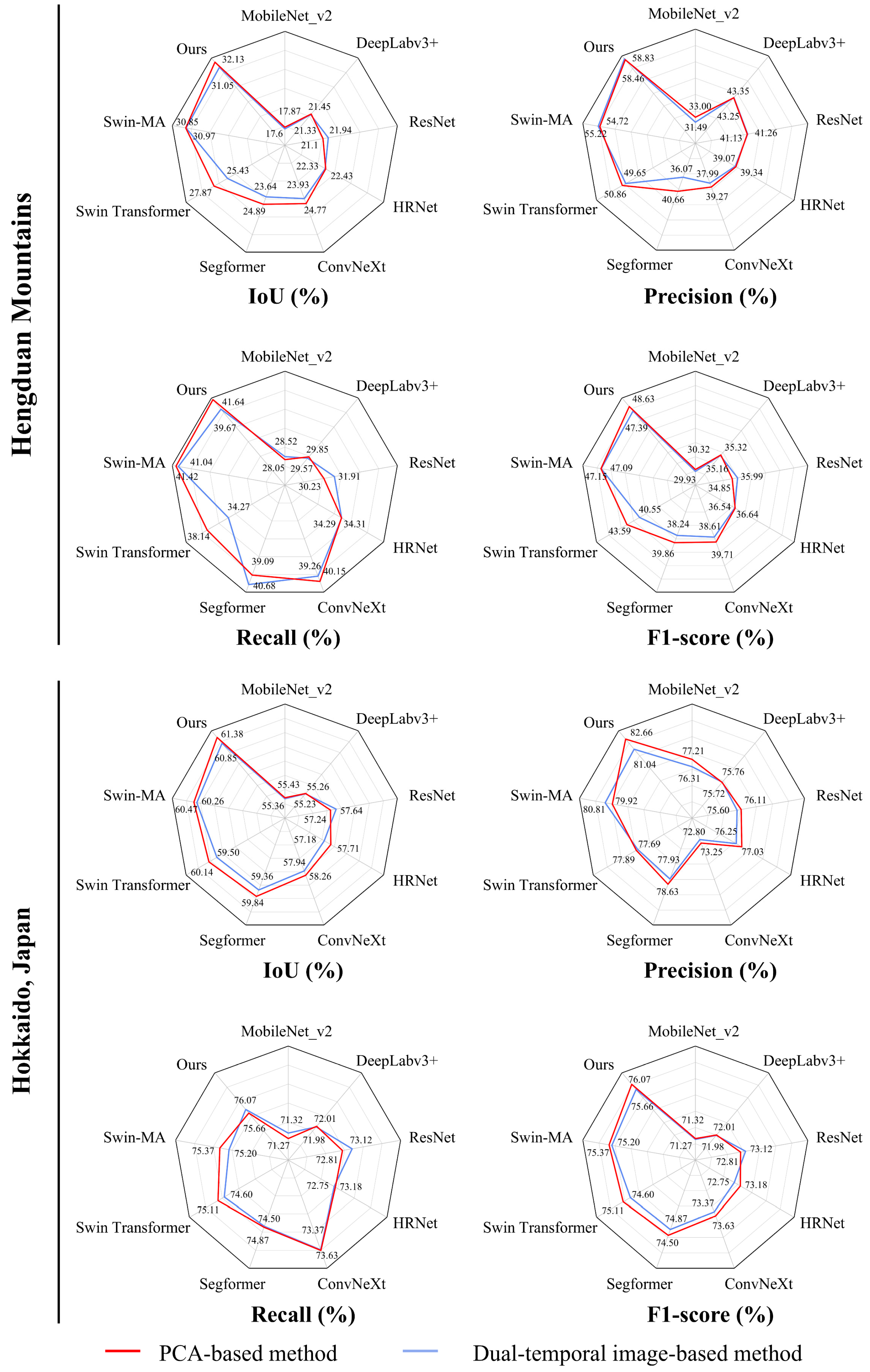

5.1. Quantitative Comparison

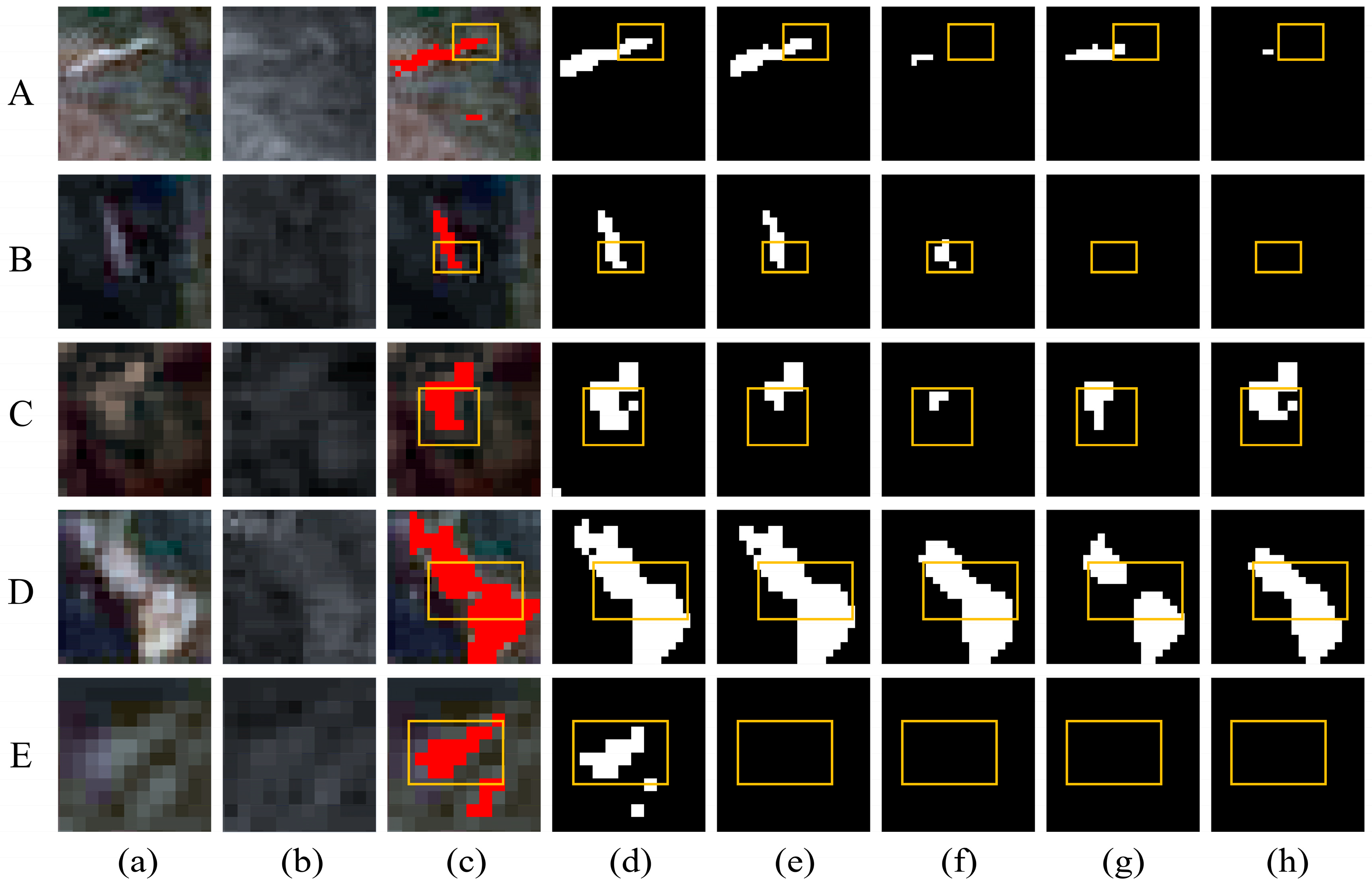

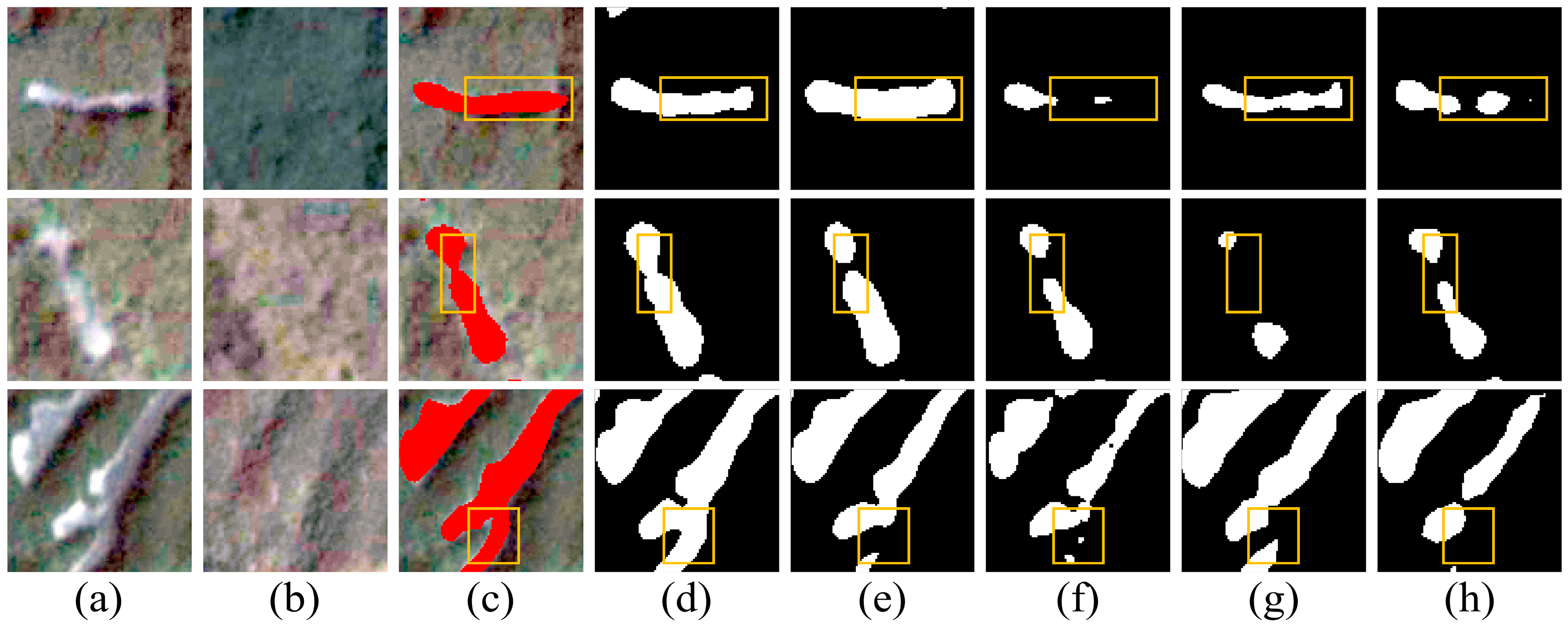

5.2. Visualization Comparison

5.3. Ablation Study

6. Discussion

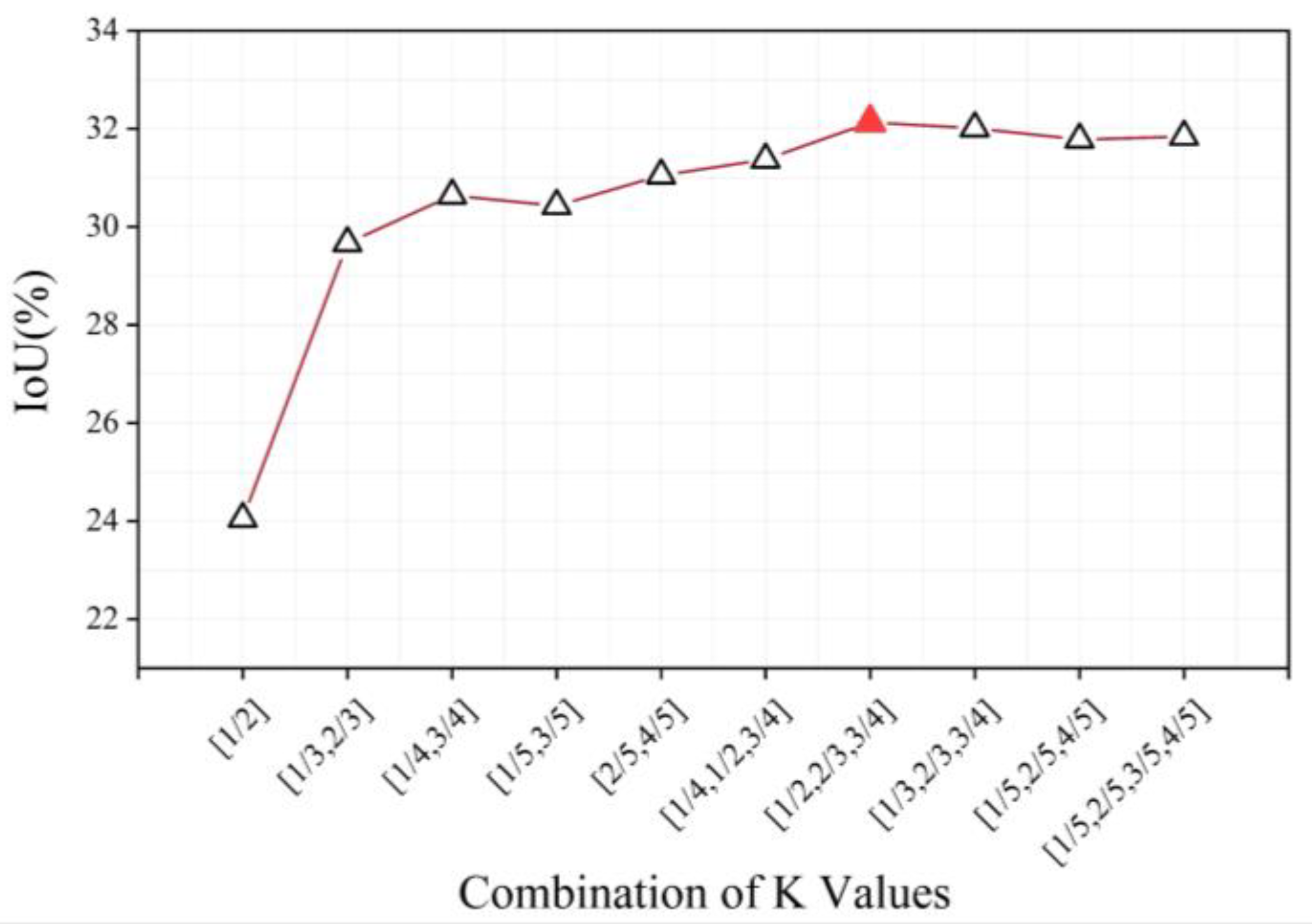

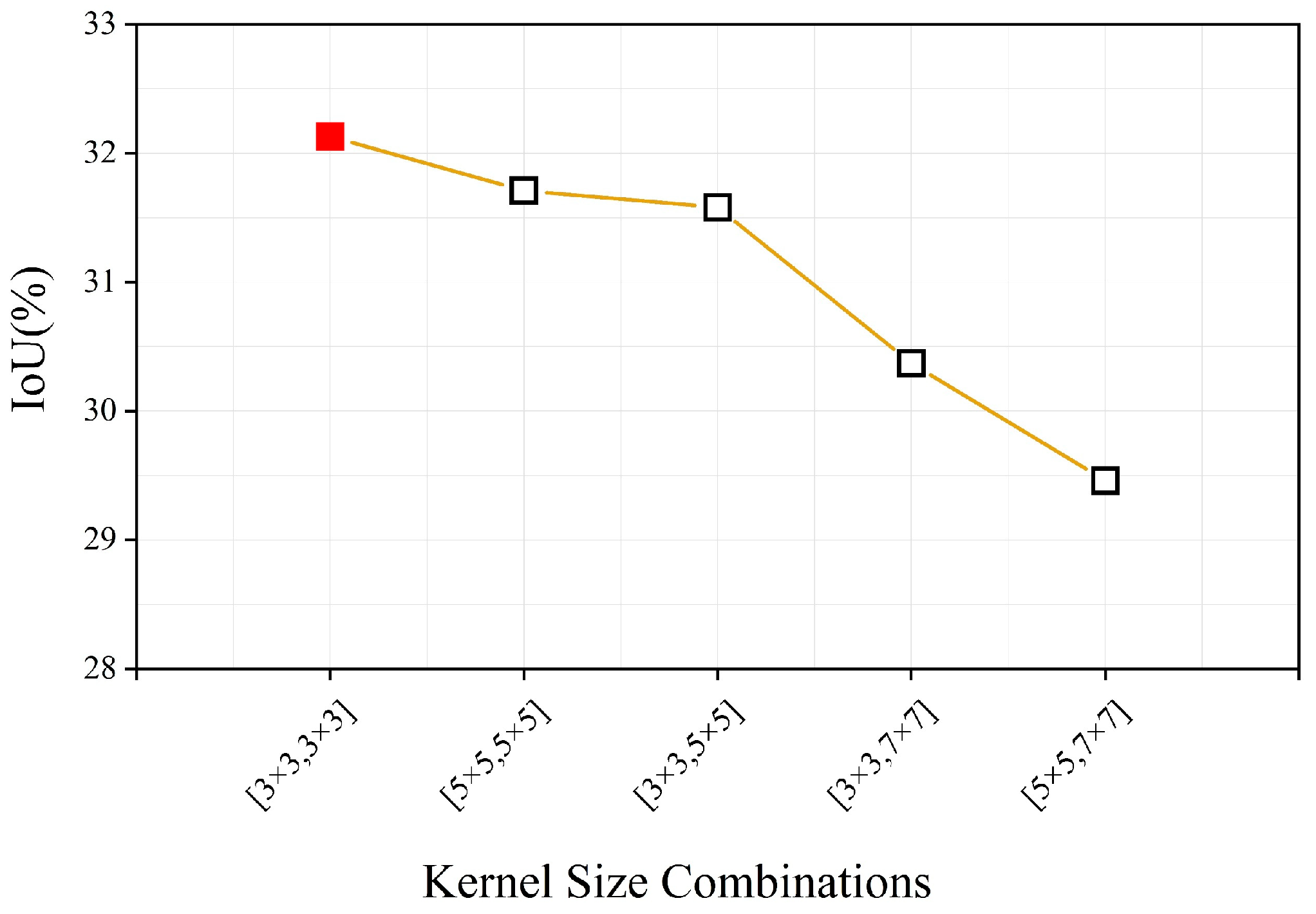

6.1. Optimal Parameter Settings for SISA and MSFA

6.2. Impact of Feature Confusion Between Landslides and Background in the Hengduan Mountains

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SISA | Spike-inspired sparse attention |

| MSFA | Mix-scale feature aggregation |

| GDK | Gaussian decay kernel |

| MSF-Decoder | Multi-scale fusion decoder |

| MSCAM | Multi-scale convolutional attention module |

| EUCB | Efficient upsampling convolution block |

| CAB | Channel attention block |

| SAB | Spatial attention block |

| MSCB | Multi-scale convolution block |

| NDSI | Normalized Difference Snow Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

References

- Lu, P.; Qin, Y.; Li, Z.; Mondini, A.C.; Casagli, N. Landslide mapping from multi-sensor data through improved change detection-based Markov random field. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassa, K.; Fukuoka, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, G. Landslides: Risk Analysis and Sustainable Disaster Management; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Froude, M.J.; Petley, D.N. Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2161–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, R. Active Thickness Estimation and Failure Simulation of Translational Landslide Using Multi-Orbit InSAR Observations: A Case Study of the Xiongba Landslide. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 129, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Xu, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, N.; Wang, L. HADeenNet: A hierarchical-attention multi-scale deconvolution network for landslide detection. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2022, 111, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S., S.; S.S., V.C.; Shaji, E. Landslide Identification Using Machine Learning Techniques: Review, Motivation, and Future Prospects. Earth Sci. Inform. 2022, 15, 2063–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, D.B.; Adler, R.; Hong, Y.; Hill, S.; Lerner-Lam, A. A Global Landslide Catalog for Hazard Applications: Method, Results, and Limitations. Nat. Hazards 2010, 52, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yu, B.; Li, B. A practical trial of landslide detection from single-temporal Landsat8 images using contour-based proposals and random forest: A case study of national Nepal. Landslides 2018, 15, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzetti, F.; Mondini, A.C.; Cardinali, M.; Fiorucci, F.; Santangelo, M.; Chang, K.-T. Landslide inventory maps: New tools for an old problem. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2012, 112, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, P.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Hou, Y.; Nuremanguli, T.; Ma, H. Landslide mapping with remote sensing: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 1555–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Zhang, F.; Ma, J. Automated Landslides Detection for Mountain Cities Using Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing Imagery. Sensors 2018, 18, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, H.; Guan, W.; Yang, A. Pakistan’s 2022 floods: Spatial distribution, causes and future trends from Sentinel-1 SAR observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 304, 114055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Du, E.; Jia, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Lagged effects of atmospheric circulation teleconnections on agricultural drought prediction in China. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2528628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Sun, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, F.; Wang, L. Post-disaster building damage assessment based on gated adaptive multi-scale spatial-frequency fusion network. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2025, 141, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Chen, F.; Ye, C.; Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, L. Temporal Expansion of the Nighttime Light Images of SDGSAT-1 Satellite in Illuminating Ground Object Extraction by Joint Observation of NPP-VIIRS and Sentinel-2A Images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, N.; Ma, P.; Yu, B. Retrieval of dominant methane (CH4) emission sources, the first high-resolution (1–2 m) dataset of storage tanks of China in 2000–2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 3369–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, A.; Nan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, G. Postearthquake Landslides Mapping from Landsat-8 Data for the 2015 Nepal Earthquake Using a Pixel-Based Change Detection Method. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 1758–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Al-Najjar, H.A.; Sameen, M.I.; Mezaal, M.R.; Alamri, A.M. Landslide detection using a saliency feature enhancement technique from LiDAR-derived DEM and orthophotos. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 121942–121954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Zhu, M.; Chen, F.; Wang, N.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L. Multi-scale differential network for landslide extraction from remote sensing images with different scenarios. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2441920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Blaschke, T.; Gholamnia, K.; Meena, S.R.; Tiede, D.; Aryal, J. Evaluation of different machine learning methods and deep-learning convolutional neural networks for landslide detection. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.D.; Yao, X.J.; Duan, H.Y.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Pang, W.L. Glacier extraction based on high-spatial-resolution remote-sensing images using a deep-learning approach with attention mechanism. Cryosphere 2022, 16, 4273–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H. A Research on Landslides Automatic Extraction Model Based on the Improved Mask R-CNN. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, M.; Ke, H.; Fang, X.; Zhan, Z.; Chen, S. Landslide Recognition by Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 4654–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; He, Y.; Xu, Q.; Deng, J.; Li, W.; Wei, Y. Detection and segmentation of loess landslides via satellite images: A two-phase framework. Landslides 2022, 19, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yao, S.; Yang, W.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, B. A landslide extraction method of channel attention mechanism U-Net network based on Sentinel-2A remote sensing images. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 552–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The Research on Landslide Detection in Remote Sensing Images Based on Improved DeepLabv3+ Method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xu, C.; Li, L. Landslide detection based on ResU-net with transformer and CBAM embedded: Two examples with geologically different environments. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; He, Z.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, H. Cost-effective and real-time landslide monitoring method based on ultra-wideband using ultra-wideband transformer neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 11185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Fu, Y.; Li, W.; Bai, H.; Jiang, Y. ETGC2-Net: An Enhanced Transformer and Graph Convolution Combined Network for Landslide Detection. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L. Dynamic detr: End-to-end object detection with dynamic attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2988–2997. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, H.; Jia, Y.; Chen, R.; Ge, Y.; Ming, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, H. MAST: An Earthquake-Triggered Landslides Extraction Method Combining Morphological Analysis Edge Recognition with Swin-Transformer Deep Learning Model. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 2586–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, R.; Ju, N.P.; Zhang, A.; Gou, J.S.; He, G.L.; Lei, Y.Z. Landslide mapping based on a hybrid CNN-transformer network and deep transfer learning using remote sensing images with topographic and spectral features. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2024, 126, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Y. DBSANet: A Dual-Branch Semantic Aggregation Network Integrating CNNs and Transformers for Landslide Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Gong, W.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Ren, T. TCNet: Multiscale fusion of transformer and CNN for semantic segmentation of remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 3123–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Chen, F.; Xu, C. Landslide detection based on contour-based deep learning framework in case of national scale of Nepal in 2015. Comput. Geosci. 2020, 135, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Xu, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhao, B.; Luo, Y. CAS Landslide Dataset: A Large-Scale and Multisensor Dataset for Deep Learning-Based Landslide Detection. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Pun, M.-O.; Shi, W. Cross-Domain Landslide Mapping from Large-Scale Remote Sensing Images Using Prototype-Guided Domain-Aware Progressive Representation Learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 197, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Si, T.; Ullah, K.; Han, W.; Wang, L. DSFA: Cross-Scene Domain Style and Feature Adaptation for Landslide Detection from High Spatial Resolution Images. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 2426–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Soatto, S. FDA: Fourier Domain Adaptation for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 4084–4094. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Du, J.; Wu, M.; Chai, B.; Miao, F.; Wang, Y. Potential of Synthetic Images in Landslide Segmentation in Data-Poor Scenario: A Framework Combining GAN and Transformer Models. Landslides 2024, 21, 2211–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Gao, P.; Wang, Y.; Tai, Y.; Wang, C. Prototypical Contrast Adaptation for Domain Adaptive Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.06654. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, G.; Pei, J.; Deng, L. Spike Attention Coding for Spiking Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 18892–18898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Panda, P. Towards Spike-Based Machine Intelligence with Neuromorphic Computing. Nature 2019, 575, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Li, B.; Yu, Z. Sparsespikformer: A co-design framework for token and weight pruning in spiking transformer. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 6410–6414. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Q.; Deng, H.; Duan, Y.; Deng, L.-J. Tcja-Snn: Temporal-Channel Joint Attention for Spiking Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 5112–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, C.; Ma, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Inventory and spatial distribution of landslides triggered by the 8th August 2017 MW 6.5 Jiuzhaigou earthquake, China. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 30, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Ma, S.; Xu, C.; Zhang, P.; Wen, B.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Cui, Y. Planet Image-Based Inventorying and Machine Learning-Based Susceptibility Mapping for the Landslides Triggered by the 2018 Mw6.6 Tomakomai, Japan Earthquake. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ryu, J.-H.; Kim, I.-S. Landslide susceptibility analysis and its verification using likelihood ratio, logistic regression, and artificial neural network models: Case study of Youngin, Korea. Landslides 2007, 4, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhou, Q.; Niu, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhi, Z. Spatial Risk Assessment of the Effects of Obstacle Factors on Areas at High Risk of Geological Disasters in the Hengduan Mountains, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Xie, S.; Mi, J. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 2753–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xu, X.; Yao, X.; Dai, F. Three (nearly) complete inventories of landslides triggered by the May 12, 2008 Wenchuan Mw 7.9 earthquake of China and their spatial distribution statistical analysis. Landslides 2014, 11, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomonson, V.V.; Appel, I. Estimating Fractional Snow Cover from MODIS Using the Normalized Difference Snow Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 89, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Pan, J. Learning a sparse transformer network for effective image deraining. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 5896–5905. [Google Scholar]

- Keerthi, S.S.; Lin, C.J. Asymptotic Behaviors of Support Vector Machines with Gaussian Kernel. Neural Comput. 2003, 15, 1667–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Munir, M.; Marculescu, R. Emcad: Efficient multi-scale convolutional attention decoding for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 11769–11779. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, K.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, B.; Deng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Mu, Y.; Tan, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Deep high-resolution representation learning for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 3349–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11966–11976. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Misra, I.; Schwing, A.G.; Kirillov, A.; Girdhar, R. Masked-Attention Mask Transformer for Universal Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1290–1299. [Google Scholar]

| Study Area | Model | IoU | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hengduan Mountains | MobileNet_v2 | 17.87 | 33.00 | 28.05 | 30.32 |

| DeepLabv3+ | 21.45 | 43.25 | 29.85 | 35.32 | |

| ResNet | 21.10 | 41.13 | 30.23 | 34.85 | |

| HRNet | 22.43 | 39.34 | 34.29 | 36.64 | |

| ConvNeXt | 24.77 | 39.27 | 40.15 | 39.71 | |

| Segformer | 24.89 | 40.66 | 39.09 | 39.86 | |

| Mask2Former | 26.04 | 42.15 | 40.52 | 41.32 | |

| Swin Transformer | 27.87 | 50.86 | 38.14 | 43.59 | |

| Swin-MA | 30.85 | 54.72 | 41.42 | 47.15 | |

| Ours | 32.13 | 58.46 | 41.64 | 48.63 | |

| Hokkaido, Japan | MobileNet_v2 | 55.43 | 77.21 | 66.27 | 71.32 |

| DeepLabv3+ | 56.26 | 75.72 | 68.64 | 72.01 | |

| ResNet | 57.24 | 76.11 | 69.78 | 72.81 | |

| HRNet | 57.71 | 77.03 | 69.71 | 73.18 | |

| ConvNeXt | 58.26 | 73.25 | 74.01 | 73.63 | |

| Segformer | 59.84 | 78.63 | 71.46 | 74.87 | |

| Mask2Former | 58.52 | 76.50 | 71.34 | 73.83 | |

| Swin Transformer | 60.14 | 77.89 | 72.52 | 75.11 | |

| Swin-MA | 60.47 | 79.92 | 71.30 | 75.37 | |

| Ours | 61.38 | 82.66 | 70.45 | 76.07 |

| Study Area | Base | SISA | MSFA | IoU | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hengduan Mountains | √ | 26.13 | 41.19 | 34.80 | 41.43 | ||

| √ | √ | 28.27 | 55.48 | 36.56 | 44.08 | ||

| √ | √ | 28.02 | 51.41 | 38.11 | 43.77 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 32.13 | 58.46 | 41.64 | 48.63 | |

| Hokkaido, Japan | √ | 60.14 | 77.89 | 72.52 | 75.11 | ||

| √ | √ | 61.01 | 79.43 | 72.46 | 75.78 | ||

| √ | √ | 60.52 | 78.95 | 72.16 | 75.40 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 61.38 | 82.66 | 70.45 | 76.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, M.; Chen, F.; Wang, L.; Yu, B. A Spike-Inspired Adaptive Spatial Suppression Framework for Large-Scale Landslide Extraction. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010129

Gao M, Chen F, Wang L, Yu B. A Spike-Inspired Adaptive Spatial Suppression Framework for Large-Scale Landslide Extraction. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Mengjie, Fang Chen, Lei Wang, and Bo Yu. 2026. "A Spike-Inspired Adaptive Spatial Suppression Framework for Large-Scale Landslide Extraction" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010129

APA StyleGao, M., Chen, F., Wang, L., & Yu, B. (2026). A Spike-Inspired Adaptive Spatial Suppression Framework for Large-Scale Landslide Extraction. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010129