Highlights

What are the main findings?

- CNNs can be successfully applied to mapping diverse and numerous classes (18 classes) over a spatially large mountainous protected region using high-resolution (0.12-m) orthophotomaps.

- The mapping accuracies are exceedingly high for typical land cover classes but are not satisfactory for more sophisticated classes, such as plant species.

- Ordinary orthophotomaps are a suitable substrate for land cover type mapping but might not be sufficient for delimiting complex classes, such as plant species or plant habitats.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Orthophotomaps combined with CNNs could be a sufficient data source to perform mapping of numerous land cover types, resulting in maps with a superior spatial resolution.

- The use of high-resolution orthophotomaps and CNNs for mapping plant species, habitats, or otherwise complex classes should be investigated further.

Abstract

Land cover mapping delivers crucial information for land and environmental management stakeholders. This work investigated the use of high-resolution RGB orthophotomaps for land cover mapping in the mountainous protected area of Tatra National Park. While a typical orthophotomap has very high spatial resolution, it also lacks multiple spectral bands (especially in the NIR-SWIR region), which makes them ill-suited as input for more classical image classification approaches. With widespread access to sophisticated machine learning algorithms and paradigms such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), their use for land cover mapping can be investigated using very-high-resolution orthophotomaps. In this work, we investigated the use of CNNs for mapping land cover types of Tatra National Park using orthophotomaps with a spatial resolution of 0.12 m. The overall accuracies varied from 86% to 92% depending on the classification variant. Most classes had high accuracies (with an F1-score above 0.90), but more complex classes, such as plant species, were identified with F1-scores between 0.32 and 0.55. The application of CNNs in land cover mapping represents a significant advancement, greatly enhancing the effectiveness and precision of the mapping process.

1. Introduction

Accurate information regarding land cover is desired by numerous national and international institutions, mainly for purposes of monitoring, planning, and forecasting. Such information can be acquired via either the photointerpretation of image data or, more often, approaches using sophisticated algorithms, usually developed with machine learning and its sister sciences [1,2,3]. In the case of algorithmic approaches, the data used to create land cover maps are, most often, the limiting factor regarding the quality of results. Various satellite and aerial sensors have been used in the past with some success [4]. Moreover, the spectral resolution and quantity of spectral bands delivered by a given dataset are at odds with spatial resolution, excluding specialized sensors or use cases. Hyperspectral data acquired using aerial platforms are the gold standard for datasets, which can be, in theory, used effectively to map almost anything with highly satisfactory accuracy [5,6,7]. Unfortunately, such datasets are at a premium, usually requiring dedicated data acquisition campaigns. Moreover, data collections are spatially limited due to high cost, sensitivity to light conditions, and the laborious process of data processing [8]. This makes large-scale hyperspectral data acquisition challenging and very rare. On the one hand, orthophotomaps are a commonly acquired product by almost every nation’s institutions. Orthophotomaps have only a few spectral bands (typically three, either in the visible spectrum or including near-infrared). On the other hand, they are usually collected with a spatial resolution well below 1 m (for example, 0.25 m and better in Poland), often surpassing 0.20 m [9]. While high-resolution imagery offers a potential solution, its interpretation relies on subjective human judgment due to the lack of specialized tools. To address this issue, automated methods for efficient and reproducible classification of high-resolution imagery are needed. Exploiting high resolution requires advanced pattern detection algorithms based on deep neural networks, which have garnered increasing attention in recent years for their ability to enhance conservation strategies within national parks [10]. One must question whether such datasets can be used to tackle research topics that usually use multispectral or hyperspectral data, such as detailed multiclass land cover maps and plant species maps.

National parks were established to protect unique ecosystems and preserve the high biodiversity of natural habitats. Their mandate extends to protecting and maintaining local biodiversity, sustainable use of natural resources, and preventing ecological degradation. National parks are integral to conservation efforts, necessitating precise planning and accurate data collection. Today, accurate information is crucial for decision-makers for data-driven management of anthropogenic factors that accelerate environmental changes [11]. National parks are also the primary research area for studying and monitoring rare or endangered plant species and plant habitats [12]. Requirements for the type of vegetation protection depend on the specifics of the park and are included in the vegetation management plan. The vegetation management plan in national parks is mostly dynamic and flexible, allowing it to respond to changing environmental conditions and conservation needs. This plan also describes tasks for monitoring the condition of ecosystems. The current Tatra National Park (TNP) protection plan includes the maintenance of the unique high-mountain landscape of lower and upper mountain zone forests.

Land cover classification categorizes different areas of the Earth’s surface using various data sources, including those delivered via remote sensing. This process is crucial for various scientific, environmental, and practical applications. Identifying habitats and monitoring changes in land cover are essential for conserving biodiversity, ensuring the preservation of critical habitats and species, tracking the health of ecosystems, and conservation planning efforts [13]. Land cover mapping helps in forest management by identifying forest types, estimating timber volume, and monitoring deforestation and forest degradation [14]. It is also useful for urban planning and development, water resource management, agricultural applications, and disaster management [15]. Land cover classification is pivotal in various fields by providing essential data that support environmental conservation, resource management, urban planning, and disaster management.

Machine learning methods such as random forest (RF), support vector machines (SVMs), and XGBoost are proven to work sufficiently well for many image classification problems. However, advanced techniques are necessary for more complex problems. Deep learning methods have grown in popularity and effectiveness in recent years. They use a variety of network architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or diffusion-based models. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are extremely effective for image analysis [16]. Incorporating convolution and pooling layers into CNNs allows the detection of patterns, such as edges, textures, or characteristics [17]. In addition, the learning process of neural networks enables automatic adjustment of neuron weights via backpropagation, which allows adaptation to various inputs and improves the efficiency of image analysis depending on the specific task. A large number of pre-trained models also exists, such as AlexNet or VGG, which can be adapted to specific problems via fine-tuning. Nevertheless, in some cases, it might be necessary to develop a customized architecture tailored to meet the specific requirements of the particular challenge.

Land cover classification has seen significant advancements with the integration of deep learning techniques, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs). CNNs solve complex classification problems by applying specialized transformation layers to image data. The operational principles of CNNs are based on two components: feature extraction and a deep neural network. Feature extraction is mainly carried out via convolutional layers with trainable kernels. To further assist this process, additional specialized intermediate layers, such as pooling, normalization, and dropout, are used. The role of the feature extraction part is to transform image data into a new, less complex form with redundancies removed and key characteristics emphasized, which is fed into deep neural networks. A deep neural network is usually built by joining multiple dense layers of neurons with additional intermediate layers, such as dropout and normalization. In this part, the classification problem is solved during network training.

CNNs are also used for image segmentation, which helps identify and classify different types of land cover more precisely [18]. These methods have demonstrated high accuracy and efficiency in various applications, from urban mapping to agricultural monitoring. The integration of deep learning, particularly CNNs, has revolutionized land cover classification [19]. These techniques offer high accuracy, robustness, and adaptability across various applications, from agricultural monitoring to disaster response and environmental mapping. Lin and Chuang [20] compared three CNN architectures—VGG19, ResNet50, and SegNet—to identify forest and vegetation types in Taiwan on high-resolution aerial photographs. They concluded that VGG19 achieved the highest classification accuracy, while SegNet offered the best performance and stability. Gao et al. [21] applied a fully convolutional network (FCN) based on U-Net for land cover classification in mountainous areas. They incorporated multimodal features, including topographic data, to enhance accuracy. Deigele et al. [22] utilized CNNs to detect windthrow damage from PlanetScope and high-resolution aerial imagery. They found that U-Net modifications provided effective results in identifying damaged areas post-storm, demonstrating CNNs’ potential in disaster response scenarios. Egli and Höpke [9] demonstrated that CNNs could classify tree species using high-resolution RGB images from UAVs, achieving an average accuracy of 93% after 50 epochs. This approach has proven effective regardless of phenological stages, lighting conditions, or atmospheric variations, indicating CNNs’ adaptability to different environmental conditions. Truong et al. [23] developed a high-resolution land use and land cover map for Vietnam using time-feature convolutional neural networks. Their model achieved a high overall accuracy of 90.5% by incorporating seasonal satellite data, surpassing other 10 m resolution maps for the region. The ongoing research and development in this field promise further enhancements in the precision and utility of land cover classification systems.

While many recent studies have focused on land cover classification in relatively small or homogeneous areas, this study extends these approaches to a more complex and heterogeneous mountainous region. Mapping large areas introduces additional challenges, including increased class diversity, topographic variability, and intra-class heterogeneity, all of which may reduce classification performance if not properly addressed. Furthermore, many prior studies have often neglected ecologically diverse and structurally complex environments, such as mountain ecosystems. In contrast, this study aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of using high-resolution orthophotomaps combined with convolutional neural networks to generate accurate and thematically rich land cover maps over a large and ecologically diverse area. Our area of research was Tatra National Park (TNP), a protected mountainous region characterized by a mosaic of natural habitats, including alpine grasslands, subalpine shrub communities, and forests. Our study investigated the underexplored potential of CNNs for high-resolution RGB-based mapping at the landscape scale.

The objectives of this study were as follows:

- To show the feasibility of using high-resolution orthophotomaps to create high-fidelity multiclass land cover maps using CNNs:

- ○

- To create a high-accuracy land cover map of TNP;

- ○

- To map multiple distinct classes on an RGB orthophotomap;

- ○

- To create methods for creating land cover maps using convolutional neural networks.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area

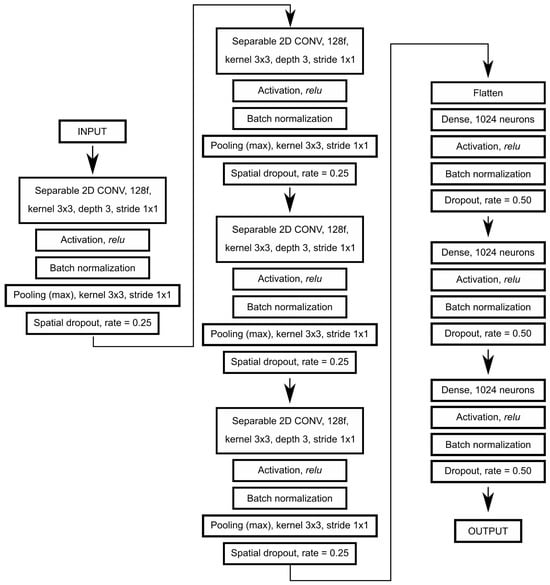

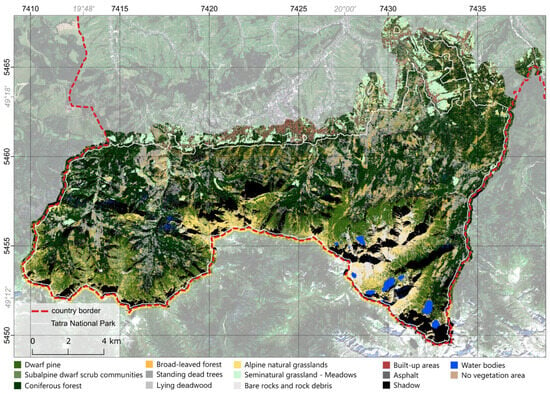

Tatra National Park (TNP) was established on 1 January 1955 and is located in southern Poland bordering Slovakia (Figure 1). Since then, it has been considered to host one of the most valuable alpine vegetation habitats in Europe. It is listed as a UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve and as a Natura 2000 site due to its unique alpine character, biodiversity, and the presence of endemic species. The National Park has a protective function, aiming to preserve and protect the unique nature and landscape of the Tatra Mountains. Conservation activities include environmental monitoring, environmental education, tourism management, and measures to preserve and restore endangered species and habitats. Most of TNP is located in a mountain climate zone. It is characterized by long winters, heavy snowfall, and a short but intense growing season. The vegetation of TNP is not only an important part of the landscape but also vital in maintaining biodiversity and mountain ecosystems. Protecting and preserving this unique ecosystem is a priority for park management and scientific research in the area. The research area is 18.5 km by 51.5 km (approx. a 211 square km area).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area with the high-resolution orthophotomap overlaid. Grayed-out background image: acquired by Sentinel-2 on 4 July 2019; RGB composition.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Reference Data

Reference data were collected during field surveys conducted at various times during the growing season from July to September in 2012–2014, 2018–2019, and 2021 [24]. Additionally, photo interpretation was used in remote or hard-to-reach areas.

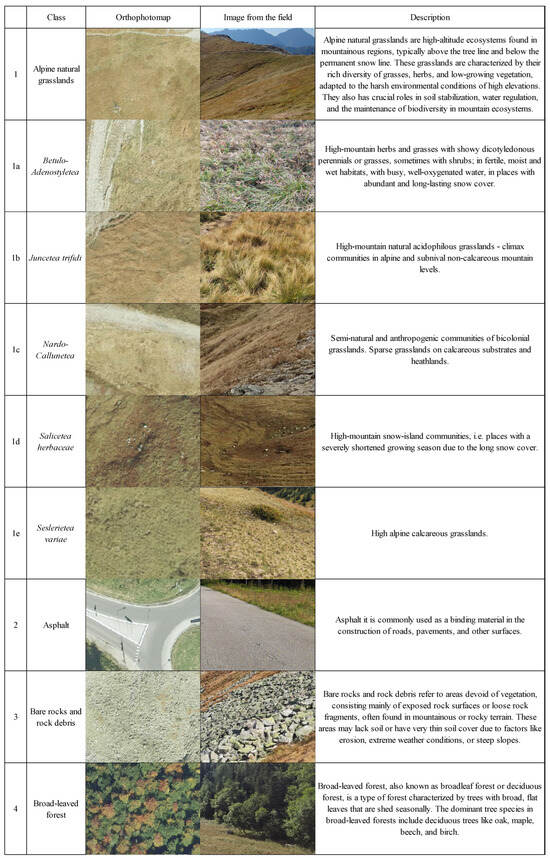

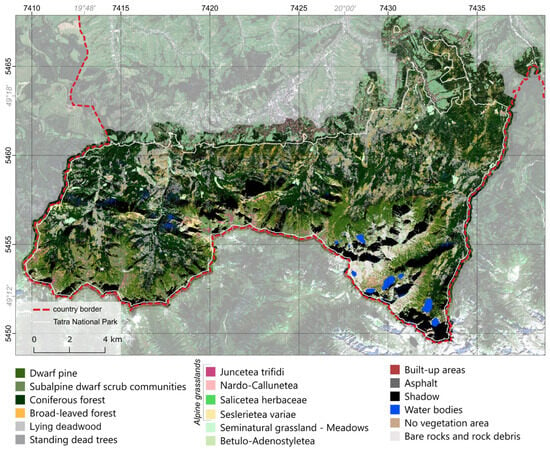

We created two land cover class variants to test our algorithm and dataset. The first one was more generalized, while the other split the class “alpine natural grasslands” into five distinct subclasses, representing plant species associated with this class (Table 1). Variant A contained 14 classes, while variant B contained 18 classes.

Table 1.

Number of reference polygons per class.

The class names were arranged to correspond with classes derived from Corine Land Cover (CLC). Detailed descriptions of the classes are presented in Figure 2. Due to the disturbances caused by the bark beetle in TNP (mainly concentrated in coniferous forests), additional classes were distinguished: lying and standing deadwood. Since alpine grasslands are the dominant non-forest community characterized by significant internal diversity, it was decided to divide this class into subclasses. Within the framework of alpine grasslands, the following sub-classes were distinguished in variant B: Betulo-Adenostyletea, Juncetea trifidi, Nardo-Callunetea, Salicetea herbaceae, and Seslerietea variae (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Descriptions of delimited classes with photo key.

2.2.2. Orthophotomap

The orthophotomap used in this paper was acquired on 1 October 2019. The high-resolution aerial imagery used in this study was obtained as part of the project “Inventory and assessment of natural resources in Tatra National Park using modern remote sensing technologies” (POIS.02.04.00-00-0010/18), funded under the Operational Program of Infrastructure and Environment. The ground-sampling distance (GSD) of the images was 12 cm. The images were acquired in RGB composition (red, green, and blue). The flight altitude above ground level ranged from 1410 to 2830 m, with a longitudinal overlap of 70% and a lateral overlap of 30%. A network of photogrammetric ground control points was established and measured using a GPS-equipped device to ensure high geometric accuracy. Aerotriangulation was performed using the INPHO Match-AT software with precise orientation parameters derived from DGPS and INS data. The orthophotomap was generated using INPHO OrthoVista with radiometric correction and tonal balancing applied to ensure consistency across the mosaic. Orthorectification was performed using a digital terrain model (DTM) with a 0.5 m grid. The completeness, geometric accuracy, and radiometric consistency of the orthophotomap were thoroughly checked. No significant geometric or radiometric errors were detected during the quality control procedures. In this work, we will refer to the map as a three-band RGB or RGB orthophotomap. The orthophotomap covers the whole area of TNP.

3. Methods

The convolutional neural network architecture used in this work was simulated using the TensorFlow (2.10.1) [25] and Keras (2.10.0) [26] packages for Python 3.10. Additionally, the Pandas (1.5.2) [27], Geopandas (0.12.2) [28], Rasterio (1.2.10) [29], and NumPy (1.24.0) [30] packages were used for preprocessing and general data manipulation.

Before the network-training step, all reference polygons were divided into training and validation datasets in a ratio of 63.2% to 36.8%. We divided our samples at the polygon level before attempting to create image signatures for each reference polygon. This way, we ensured that image signatures coming from the same polygon were either in the training or validation dataset. Failure to ensure so would result in skewed accuracy results due to a high correlation between image samples coming from the same reference polygon [6].

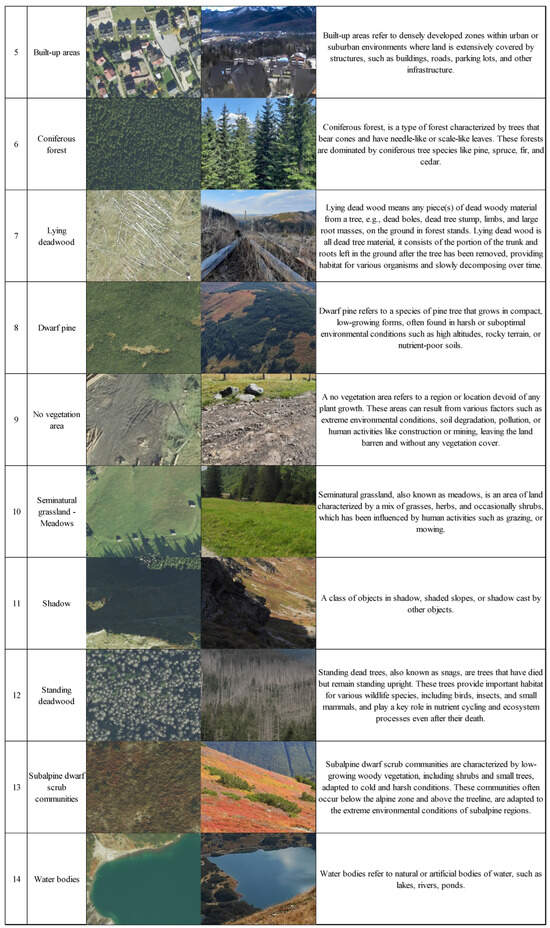

Convolutional neural networks are designed to analyze data samples obtained as structured data (such as an image matrix or a data table). Vector reference polygons with varying sizes are only used to delimit which image pixels belong to a given class. One must create image samples to create useful data for CNN training. There are many ways one could approach this dilemma. In this work, we used an image window of arbitrary size centered around a reference pixel. We decided experimentally to use a square window size of 9 pixels. The window size is always a trade-off between the amount of information contained in the window (i.e., the pixel number) and the processing time [9]. This relation is nonlinear; thus, using bigger windows will rapidly and dramatically increase processing and network training times while also posing a risk of exhausting memory resources, making the process impossible.

The whole procedure of creating image signatures was as follows (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Procedure for creating image signature.

- Each training or validation polygon was transformed into a mesh of points in such a way that each point was always at least half of the window size (in pixels) away from any of its neighbors. Additionally, for particularly large polygons, this distance was increased to balance the overall number of image signatures across all classes.

- For each point, an image signature was created by clipping a window (n by n pixels) centered around that point. In this particular case, image signatures were 9-by-9-pixel image cutouts. All spectral bands were included in the image signature. Additional information about the image signature, such as the class it represented and the unique ID of the reference polygon from which it came, was added.

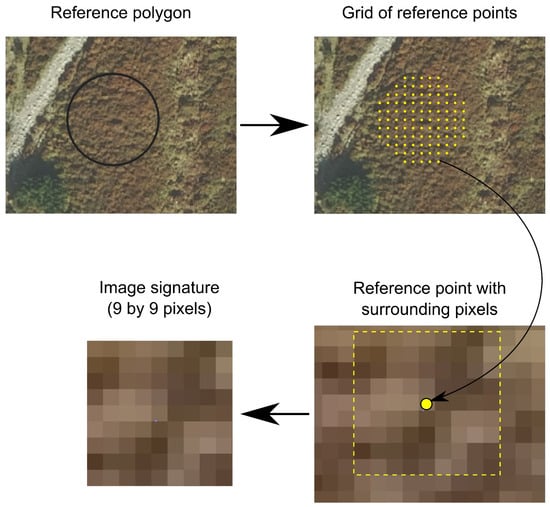

The above procedure resulted in two (henceforth referred to as training and validation datasets; Table 2) four-dimensional tensors with the following dimensions: (number of image signatures, window size, window size, number of spectral bands). Our approach allowed us to use information regarding neighboring pixels while also trying to leverage information that is not available for pixel-based approaches, such as texture and structure. Textural and structural information can be extracted by CNNs during the training process. Moreover, we used specialized separable convolution layers instead of typical convolution layers. Separable convolution layers carry an additional convolution on each channel (band) separately, in addition to further convolutions. One glaring disadvantage of the proposed method is its extreme computational cost compared with other methods. The artificial neural network architecture used in this work consisted of four convolutional blocks, each with its own normalization, pooling, and dropout layers, followed by three dense layers intertwined with normalization and dropout layers (Figure 4). Finally, the training dataset was augmented during the training process (image signatures were randomly flipped either horizontally or vertically).

Table 2.

Number of image signatures for each class per classification variant and dataset type (training or validation).

Figure 4.

Artificial neural network architecture used in this work.

The following training parameters and methods were used during network training:

- A batch size of 1024;

- An epoch number of 256;

- An initial learning rate of 0.05;

- The Adam training optimizer;

- A categorical cross-entropy loss function;

- A reduction in the learning rate to 90% of its previous value, every 10 epochs;

- A dynamic reduction in the learning rate in the event of a training plateau (the network no longer trains itself successfully).

After each epoch, the trained network model was saved if it performed better than any of the previously saved networks. This allowed saving only progressively better networks, avoiding saving overtrained or poorly performing networks. The model with the lowest loss function value for the validation dataset was used for the final image classification and accuracy assessment. The best saved model and validation dataset were used to calculate the confusion matrix during the accuracy assessment. The calculated accuracy measures were as follows: overall accuracy (OA), producer accuracy (recall; PA), user accuracy (precision; UA), and F1-score. After the accuracy assessment, the best model was used to classify all orthophotomap tiles to create a land cover map on TPN. The final classification procedure was as follows:

- For each pixel on the image,

- ○

- Create an image signature (9-by-9-pixel square window), centered on a given pixel;

- ○

- Infer class label of image signature via model inference;

- ○

- Assign a class label to the pixel.

The last step is contrary to the approaches shown in the works by Jiang et al. [31] or Egli and Höpke [9], where each image window is given a label instead of a single pixel.

4. Results

The classification results for variant A achieved an overall accuracy of 92% (Figure 5). All but one class (subalpine dwarf scrub communities) had producer accuracy above 80%, similarly for user accuracy, where only two classes (subalpine dwarf scrub communities and lying deadwood) ended up with a user accuracy below 70%. A total of 12 out of 14 classes achieved an F1-score above 0.8, while 11 were characterized by an F1-score higher than 0.9. The worst-classified classes were the subalpine dwarf scrub communities (F1 0.72) and lying deadwood (F1 0.71) classes (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Classification map results for variant A.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix and accuracy measures for variant A.

The classification results for variant B achieved an overall accuracy of 86% (Table 4). The worst-performing classes were Betulo-Adenostyletea, Juncetea trifidi, Nardo-Callunetea, Salicetea herbaceae, and Seslerietea variae (with a producer or user accuracy of no more than 63%), indicating the poor performance of the classification algorithm in distinguishing them. Among the remaining classes, all but two (subalpine dwarf scrub communities and lying deadwood) achieved producer accuracies above or close to 90%. Besides plant species classes, only the classes of lying deadwood and built-up areas had a user accuracy below 85%. Overall, nine classes achieved an F1-score above 0.90, with five classes not reaching an F1-score of 0.60.

Table 4.

Confusion matrix and accuracy measures for variant B.

The most underestimated class was subalpine dwarf scrub communities (with a producer accuracy of 76.78%), which was most often confused with the alpine natural grasslands class. The least-reliable classification results were obtained for the class lying deadwood (61.31% user accuracy) and subalpine dwarf scrub communities (67.60% user accuracy) classes. The lying deadwood class was confused with standing deadwood, bare rocks, and rock debris classes, while the subalpine dwarf scrub communities class was most frequently confused with the alpine natural grasslands class.

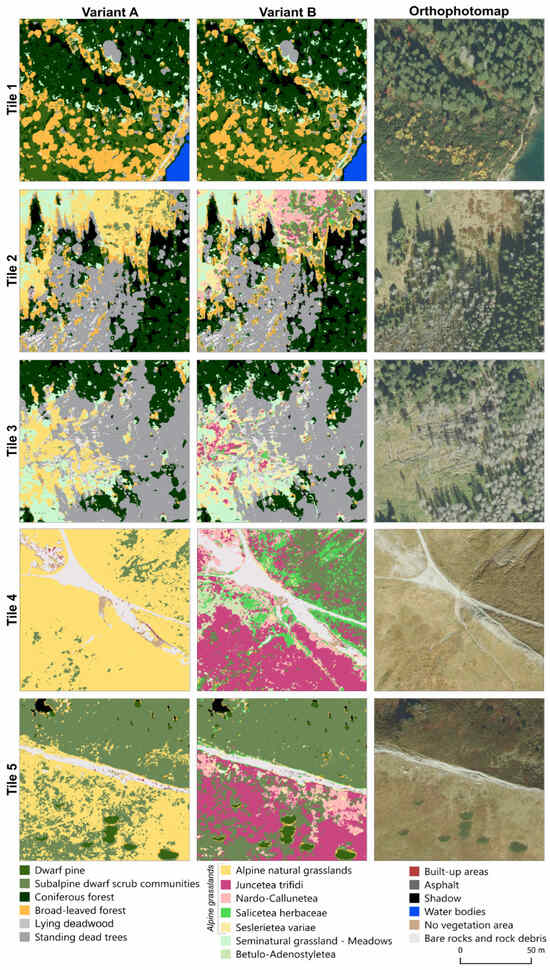

In the case of classification variant B (Figure 6), both classes (subalpine dwarf scrub communities and lying deadwood) showed similar results. However, the subalpine dwarf scrub communities class showed varying degrees of confusion with the alpine natural grasslands class (with the highest confusion with the Juncetea trifidi class). The subalpine dwarf scrub communities class was often mixed with the alpine natural grasslands class. This might have resulted from their frequent intermixing, creating a vegetation mix that is not easily distinguished, even with high-resolution RGB data.

Figure 6.

Classification map results for variant B.

Comparing variants A and B, differences between the identically named classes were minimal and did not exceed a 0.05 F1-score (classes: lying deadwood, standing deadwood, asphalt, and dwarf pine). The biggest difference between those two variants was due to the inclusion of additional classes (plant communities) into variant B, which resulted in lower overall accuracy and lackluster accuracy in identifying those classes (Betulo-Adenostyletea, Juncetea trifidi, Nardo-Callunetea, Salicetea herbaceae, and Seslerietea variae).

In variant B, the lying deadwood class was also misclassified with the bare rocks, rock debris, and standing deadwood classes. This was due to the very similar reflectance values for standing and lying deadwood, as well as the influence of the substrate, exposed soil, or rocks, which are present in areas where deadwood has not yet developed significant undergrowth. This is illustrated in Figure 7 (tiles 1, 2, and 3), where correctly classified pixels for the lying deadwood class are visible. However, the standing deadwood class was overestimated, encroaching on the undergrowth areas. Tile 1 shows the classification results for a forested area, with correctly classified pixels for the coniferous forest, broad-leaved forest, and dwarf pine classes. However, in areas of low undergrowth, some areas were mistakenly classified as dwarf pine or subalpine dwarf scrub communities. These incorrectly classified pixels represent undergrowth, mostly consisting of low vegetation, ferns, shrubs, and blueberry patches. Tiles 4 and 5 in Figure 7 illustrate example classification results for an area with abundant sites of alpine natural grasslands class (variant A) and its subclasses (variant B). Additionally, there was a noticeable variation in classification results between north-facing and south-facing slopes (tile 5). South-facing slopes were predominantly covered by alpine natural grasslands (variant A) and, specifically, by Juncetea trifidi, Salicetea herbaceae, Nardo-Callunetea, Betulo-Adenostyletea, and Seslerietea variae (variant B). The class Betulo-Adenostyletea was most often misclassified as the class Juncetea trifidi, followed by the classes broad-leaved forest, Salicetea herbaceae, and Seslerietea variae. Moreover, all plant species classes classified in variant B showed similar characteristics.

Figure 7.

Comparison of classification variants A and B for different example areas (tile size: 1000 × 1000 px).

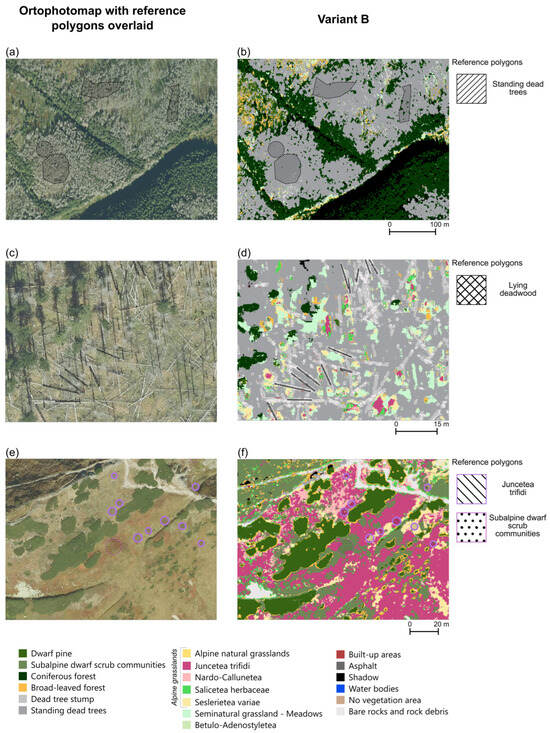

A more direct view into the results can be seen in Figure 8. This figure shows six pictures showcasing three different areas. Each area is presented on a pair of images. The first is an image of the orthophotomap with reference polygons for specific classes overlaid. The second is the classification result for variant B with reference polygons overlaid. The selection of the classes was based on the overall availability of a sufficiently small area with interesting classes. Due to the number of classes, only four were discussed in detail: standing dead trees, lying deadwood, subalpine dwarf scrub communities, and Junceatea trifidi. Insets a and b show the results of the classification on a mostly wooded area with large patches of standing dead trees. The area covered by the standing deadwood class closely matched the expected range for this class if one were to perform photointerpretation of the orthophotomap. Similarly, the classes coniferous forest and shadow were also well behaved. Most questionable areas were located in the top left part of insets a and b, where forest clearing appeared, and no reference was collected. This area was inferred to be covered by a mixture of the following classes: alpine natural grasslands, subalpine dwarf scrub communities, broad-leaved forest, and Seslerietea variae. Insets c and d show areas covered by lying deadwood mixed with patches of low vegetation and coniferous trees. The area covered by the class lying deadwood was exaggerated, while cleared areas were classified as standing dead trees. In this area, the class standing deadwood was questionable at best and was overestimated. A class describing ecological succession that happened in this area would be more appropriate. Unfortunately, in this work, no such class was created. Insets e and f show the mountain top area covered by a mixture of dwarf pine and alpine grasslands. Dwarf pine was delimited with high accuracy. This was spoiled by the “halo” effect that can be seen surrounding patches of draft pine (“halo” pixels were mostly labeled as the class broad-leaved forest). This “halo” effect seems to have been caused by the large window size used during the classification procedure. Smaller window sizes would reduce or even eliminate this effect, but at the price of decreased accuracy. Some reference polygons for the class Juncerea trifidi were completely covered by pixels labeled as the class Seslerietea variae, while others were perfectly assigned to the proper class. Moreover, areas covered by alpine grasslands were misclassified as class subalpine dwarf scrub communities. Overall, the post-classification images show a very diverse mixture of plant species, which is hard to confirm by analyzing the orthophotomap alone. Such are notoriously hard to map due to difficulties in collecting large, representative reference (i.e., permits, difficult rugged terrain, distance from roads, the necessity of performing data collection in situ, challenges in properly distinguishing specimens in the field, difficulty in finding large homogenous patches, and mixed vegetation with varying shares of plant species in habitats).

Figure 8.

Comparison between orthophotomap with reference polygons overlaid and classification results for variant B. Three example areas are showcased.

Additionally, the accuracy was also influenced by the timing of orthophotomap acquisition, as some classes significantly change their appearance over time. For example, the Juncetea trifidi class changes color from green to brown in late summer/early autumn. Calcareous alpine meadows (classes Seslerietea variae and Salicetea herbaceae) are a particularly valuable habitat in this area. These meadows develop on calcareous substrates on relatively shallow and not very moist soils with a high pH (known as rendzinas). For example, the area of Czerwone Wierchy, where the peaks are covered by a mantle of crystalline rocks (granites and gneisses), is predominantly covered by the Juncetea trifidi class. Meanwhile, the subalpine dwarf scrub communities class includes a mix of dwarf vegetation and shrubs that change color during the summer and autumn periods. This poses a significant challenge for accurate classification on an orthophotomap obtained at a single point in the growing season. The subalpine dwarf scrub communities class also includes blueberry patches, which sometimes covered excessively large areas on the resulting map. This was due to the misclassification of blueberry patches as the Salicetea herbaceae class. Such issues are particularly prevalent in depressions and low-lying areas where vegetation exhibits significantly different reflectance values in RGB images compared with the same species on slopes.

5. Discussion

Many research teams incorporated additional image data, such as the NIR band, achieving increased accuracy. Ayhan et al. [32] demonstrated the detection performance of DeepLabV3+, a custom deep learning method based on a CNN (using RGB and RGB-NIR bands), and NDVI-ML (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index–machine learning) (RGB-NIR) in their vegetation detection studies. They showed that the detection results of DeepLabV3+ using only RGB color bands were better than the results obtained with conventional methods using only the NDVI index and were close to the results of NDVI-ML, which utilized the NIR band along with several advanced machine learning and computer vision techniques. Their studies revealed that adding NDVI to the RGB input parameters improved the overall classification accuracy. The DeepLabV3+ network outperformed other deep learning methods studied, such as UNet, FCN, PSP, and SegNet. Researchers have also tested different sets of data. For instance, Kwan et al. [33] applied four bands (RGB and NIR) and five bands (RGB, NIR, and LiDAR) for land cover classification (15 land cover classes). The results showed that by using deep learning methods and EMAP extension, RGB+NIR (four bands) or RGB+NIR+LiDAR (five bands) could achieve a very good classification performance, surpassing that obtained using conventional classifiers, such as SVM and JSR (joint sparse representation). It was noted that while adding the LiDAR band to the RGB+NIR bands significantly improved classification performance compared with conventional classifiers (JSR and SVM), it did not substantially impact the performance for deep learning methods, as their results were already very good using just the RGB+NIR bands [33]. Gao et al. [21] showed the land cover mapping of mountainous areas using a fully convolutional network-based classifier (U-Net) for supervised land cover classification. They also investigated the contribution of multimodal features to improve classification accuracy by using several sets of input features: three features (RGB), four features (RGB+NIR), five features (RGB+NIR+NDVI), and six features (RGB+NIR+NDVI+DEM). The results showed that additional features resulted in higher classification accuracies compared with using only three features. Six features achieved the best results for croplands, impervious surfaces, and coniferous forests, while five features performed well for waterbodies and deciduous forests. The greatest improvement was achieved for waterbodies (where the Kappa coefficient increased from 0.741 to 0.924), followed by coniferous forests (where the Kappa coefficient increased from 0.629 to 0.805), with only slight improvements observed for the remaining three types. Additionally, the accuracy for croplands and impervious surfaces remained relatively high even without additional features, and the texture feature played a crucial role. The final land cover map was generated by combining the optimal results for each type using a hierarchical integration strategy. The overall classification accuracy was 90.6% [21].

An important contribution of this study is the inclusion and classification of deadwood, which was divided into distinct land cover classes (standing deadwood and lying deadwood). Deadwood areas, though often overlooked in land cover classifications, are ecologically critical indicators of forest health and biodiversity [34,35]. Standing dead trees (snags) represent the initial stage of wood decay, providing essential habitats for saproxylic insects, birds, and fungi, while lying deadwood supports nutrient cycling, moisture retention, and regeneration processes [36]. Deadwood serves as a proxy for post-disturbance regeneration and forest decline, and its distribution is closely tied to topographic and climatic gradients. Our classification results demonstrate that these classes can be identified with reasonable accuracy using high-resolution RGB orthophotomaps and CNNs. The class lying deadwood achieved an F1-score of 0.71, despite occasional confusion with the rock debris and standing deadwood classes. In the context of increasing forest disturbances due to climate change, particularly bark beetle outbreaks and drought-induced tree mortality [37], the ability to map and quantify deadwood at different stages is crucial. Although multispectral or hyperspectral data and LiDAR offer more detailed structural insights [35], our results show that ordinary orthophotomaps can contribute meaningful information about forest degradation patterns, particularly in protected mountain areas where access and operational feasibility of advanced sensors may be limited. Our approach enhances the applicability of land cover mapping for forest monitoring, management, and biodiversity assessments under changing environmental conditions by incorporating these structurally and ecologically significant features.

While our work does not enrich its imagery, one can and should incorporate additional data, such as LiDAR-derived products or multispectral imagery, provided they can match the spatial resolution of a typical orthophotomap. Researchers are increasingly adding additional features, such as DSM (digital surface model) and NDVI, to multispectral images for more accurate class differentiation [38]. While the literature suggests that the inclusion of features such as DSM or NDVI can enhance class separability [38], our results demonstrate that even with only RGB data, it is possible to achieve detailed and accurate land cover maps. An additional challenge lies in delivering LiDAR products that match the spatial resolution of underlying orthophotomaps (around 10 cm). While LiDAR point cloud densities have increased dramatically in recent years, the acquisition of new datasets for large protected areas lags behind, necessitating planning of additional data collection campaigns. In this work, no suitable additional dataset could be incorporated; thus, we limited ourselves to RGB aerial imagery.

As shown in Table 5, the overall accuracy of our approach is comparable to or exceeds that of several recent studies that used only RGB data [18,39,40,41] and, in some cases, approaches the performance of methods utilizing additional bands or ancillary data. Moreover, the final map created as a result of this study offers a higher level of thematic detail compared with widely used global products. For instance, relative to Dynamic World, our map includes 5–9 more land cover categories and correctly distinguishes the dwarf pine class, which is otherwise grouped as shrub/scrub in global datasets. Compared with ESA World Cover, our map provides 6–10 additional categories. This increased detail, achieved using only RGB imagery, facilitates more nuanced environmental monitoring and enables analyses such as multi-temporal change detection for specific classes. This does not diminish the information provided by such services; it simply demonstrates a different accuracy in land cover classification and highlights the challenge of remote sensing in selecting an appropriate scale for phenomena, objects, or issues raised in research. Our study highlights the potential of high-resolution RGB-based approaches for local and regional applications, as well as the ongoing challenge in remote sensing of selecting appropriate data and scales for specific research questions.

Table 5.

Comparison between recent studies in mapping land cover using deep learning techniques.

In summary, our study demonstrates that high-resolution RGB imagery alone can yield land cover maps with both high accuracy and thematic richness, comparable to or exceeding those reported in the recent literature.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, our work highlights the use of high-resolution RGB orthophotomaps for land cover types mapping with the application of convolutional neural networks. Most classes were characterized with high accuracy. Our experiments classifying individual plant species showed much less promise. This can be seen when comparing classification variants a and b. When we split the class alpine grassland into five subtypes, we achieved far lower accuracies (the PA and UA decreased from around 90% to less than 60%). Thus, the image data we used might be unsuitable for accurately mapping individual plants. Applying CNNs for mapping land cover/land use greatly enhances the effectiveness and precision of the mapping process. Detailed conclusions of this work are listed below.

The disadvantages are as follows:

- Lack of finesse: The presented method shows simple use for CNNs, without delving into developing custom layers or translation layers. Nevertheless, this can also be considered an advantage.

- Computationally expensive: Performing classification for each pixel with the corresponding image signature creates a lot of redundant calculations. Typically, neighboring pixels share around 8/9 of the pixels between them. Diffusion or transposed convolution approaches remove this inefficiency but might introduce other challenges. This should be investigated in the future.

- In general, the results seem to agree with reality but lack detail and refinement (blur-like features on the post-classification map). This effect is exaggerated by the large window size. A large window size tends to add a “halo” of dissimilar classes around objects (which can be seen around large rocks, patches of dwarf pine, and forest edges). Smaller kernels (3 by 3) result in almost no “halo” but yield lower accuracies and are characterized by a heavy “salt-and-pepper” effect, especially prevalent in heterogeneous mountain tops and high-mountain meadows, where bare soil, rocks, and vegetation form a diverse spatiospectral mixture. The overall picture looks promising, but analyzing fine details leaves users wondering if it is just an illusion. High accuracy is not a substitute for a good map. Given the size of the area mapped and spatial resolution (12 cm), it is hard to assess the true accuracy of our map, even with expert knowledge about the lay of the land in TNP.

- Due to CNNs’ nature, a trained model cannot be reasoned with and is of limited usability for more thorough analyses. Moreover, it does not answer key questions and only delivers results.

The advantages are as follows:

- Competitive accuracies: Our work achieved classification accuracies within what was reported in the literature. More broadly defined classes (such as types for forest) were classified with an F-score above or around 0.9, which is excellent. Only more sophisticated classes regarding different plant species showed lacking results. This result suggests that either the algorithm used or the data are not suitable to delimit plant species at this scale. While mapping plant species, it is crucial to consider their phenological cycle, especially the flowering phase, which is often cited as a reason for high accuracy.

- CNNs can exploit both spatial and spectral domains, which might be an important addition to image classification techniques. The model incorporates structural and textural information into the solution.

- The model works on very-high-resolution imagery, delivering sensible results.

- The model works with three-band imagery, possibly with single-band imagery too, but with reduced efficiency. This alone opens many previously unused datasets for investigation and use in future studies (panchromatic aerial photos). Three-band RGB imagery is one of the cheapest and most widely available imagery. Moreover, the data acquisition is competitively priced.

Author Contributions

E.R.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, and project administration; M.K. (Marlena Kycko): conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and visualization; M.K. (Marcin Kluczek): conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The airborne data were acquired for the project “Inventory and assessment of the state of natural resources in the Tatra National Park using modern remote sensing technologies” (no. POIS.02.04.00-00-0010/18-00; the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management) and delivered to Tatra National Park, which is the owner of the data. The reference polygons were acquired during field mapping by Marlena Kycko and Marcin Kluczek.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Tatra National Park for providing airborne remote-sensing data and permitting them to conduct field research in the park.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Murphy, J.H. An Overview of Convolutional Neural Network Architectures for Deep Learning; Microway Inc.: Plymouth, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–22. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:35625222 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Diez, Y.; Kentsch, S.; Fukuda, M.; Caceres, M.L.L.; Moritake, K.; Cabezas, M. Deep Learning in Forestry Using UAV-Acquired RGB Data: A Practical Review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagajewski, B.; Kluczek, M.; Raczko, E.; Njegovec, A.; Dabija, A.; Kycko, M. Comparison of Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and Neural Networks for Post-Disaster Forest Species Mapping of the Krkonoše/Karkonosze Transboundary Biosphere Reserve. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagajewski, B.; Kluczek, M.; Zdunek, K.B.; Holland, D. Sentinel-2 versus PlanetScope Images for Goldenrod Invasive Plant Species Mapping. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowska-Ochtyra, A.; Zagajewski, B.; Raczko, E.; Ochtyra, A.; Jarocińska, A. Classification of High-Mountain Vegetation Communities within a Diverse Giant Mountains Ecosystem Using Airborne APEX Hyperspectral Imagery. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat-Tomala, A.; Raczko, E.; Zagajewski, B. Comparison of Support Vector Machine and Random Forest Algorithms for Invasive and Expansive Species Classification Using Airborne Hyperspectral Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarocińska, A.; Kopeć, D.; Niedzielko, J.; Wylazłowska, J.; Halladin-Dąbrowska, A.; Charyton, J.; Piernik, A.; Kamiński, D. The utility of airborne hyperspectral and satellite multispectral images in identifying Natura 2000 non-forest habitats for conservation purposes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, R.; Shu, R.; Wang, J. Status and application of advanced airborne hyperspectral imaging technology: A review. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2020, 104, 103115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, S.; Höpke, M. CNN-Based Tree Species Classification Using High Resolution RGB Image Data from Automated UAV Observations. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Dang, K.B.; Giang, T.L.; Hoang, T.H.N.; Le, V.H.; Ha, H.N. Deep learning models for monitoring landscape changes in a UNESCO Global Geopark. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, L.; Molnár, A.P.; Bede-Fazekas, A.; Öllerer, K.; Varga, A.; Szabados, K.; Tucakov, M.; Kiš, A.; Biró, M.; Marinkov, J.; et al. Controlling invasive alien shrub species, enhancing biodiversity and mitigating flood risk: A win–win–win situation in grazed floodplain plantations. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, M.A.; Berauer, B.J.; Duc, A.L.; Ingrisch, J.; Niu, Y.; Bahn, M.; Jentsch, A. Increases in functional diversity of mountain plant communities is mainly driven by species turnover under climate change. Oikos 2023, 2023, e09922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Zhen, L.; Miah, G.; Ahamed, T.; Samie, A. Impact of land use change on ecosystem services: A review. Environ. Dev. 2020, 34, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuyper, M.; Roberto, O.; Chávez, R.O.; Lohbeck, M.; Lastra, J.A.; Tsendbazar, N.; Hackländer, J.; Herold, M.; Vågen, T. Continuous monitoring of forest change dynamics with satellite time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, K.; Apan, A.; Maraseni, T. Comparing global and local land cover maps for ecosystem management in the Himalayas. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 30, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural networks. Commun. ACM 2012, 60, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S.; Garg, R.D.; Meshram, V.; Mistry, S. Sen-2 LULC: Land use land cover dataset for deep learning approaches. Data Brief 2023, 51, 109724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Bretz, M.; Dewan, A.A.; Delavar, M.A. Machine learning in modeling land-use and land cover-change (LULCC): Current status, challenges and prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.C.; Chuang, Y.C. Interoperability Study of Data Preprocessing for Deep Learning and High-Resolution Aerial Photographs for Forest and Vegetation Type Identification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Luo, J.; Xia, L.; Wu, T.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H. Topographic constrained land cover classification in mountain areas using fully convolutional network. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 7127–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deigele, W.; Brandmeier, M.; Straub, C.A. Hierarchical Deep-Learning Approach for Rapid Windthrow Detection on PlanetScope and High-Resolution Aerial Image Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.T.; Hirayama, S.; Phan, D.C.; Hoang, T.T.; Tadono, T.; Nasahara, K.N. JAXA’s new high-resolution land use land cover map for Vietnam using a time-feature convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kycko, M.; Zagajewski, B.; Lavender, S.; Dabija, A. In Situ Hyperspectral Remote Sensing for Monitoring of Alpine Trampled and Recultivated Species. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous systems. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1603.04467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Keras: Deep Learning for Humans. 2015. Available online: https://keras.io (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordahl, K.; Van Den Bossche, J.; Fleischmann, M.; Wasserman, J.; McBride, J.; Gerard, J.; Tratner, J.; Perry, M.; Garcia Badaracco, A.; Farmer, C.; et al. GeoPandas, Python Tools for Geographic Data; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, S.; Ward, B.; Petersen, A. Rasterio: Geospatial Raster i/o for Python Programmers. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/rasterio/rasterio (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Feng, X.; Liu, F.; Xu, Y.; Huang, H. Multi-Spectral RGB-NIR Image Classification Using Double-Channel CNN. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 20607–20613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, B.; Kwan, C.; Budavari, B.; Kwan, L.; Lu, Y.; Perez, D.; Li, J.; Skarlatos, D.; Vlachos, M. Vegetation Detection Using Deep Learning and Conventional Methods. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.; Ayhan, B.; Budavari, B.; Lu, Y.; Perez, D.; Li, J.; Bernabe, S.; Plaza, A. Deep Learning for Land Cover Classification Using Only a Few Bands. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutras-Perreault, M.-C.; Gobakken, T.; Næsset, E.; Ørka, H.O. Comparison of Different Remotely Sensed Data Sources for Detection of Presence of Standing Dead Trees Using a Tree-Based Approach. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yrttimaa, T.; Saarinen, N.; Luoma, V.; Tanhuanpää, T.; Kankare, V.; Liang, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Holopainen, M.; Vastaranta, M. Detecting and characterizing downed dead wood using terrestrial laser scanning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 151, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, N.; Pirotti, F.; Lingua, E. Airborne and Terrestrial Laser Scanning Data for the Assessment of Standing and Lying Deadwood: Current Situation and New Perspectives. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczek, M.; Bogdan Zagajewski, B. Mapping spatiotemporal mortality patterns in spruce mountain forests using Sentinel-2 data and environmental factors. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 86, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, S.; Babapour, G.; Shah-Hosseini, R. An encoder–decoder network for land cover classification using a fusion of aerial images and photogrammetric point clouds. Surv. Rev. 2024, 57, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshari, E.A.; Abdulkareem, M.B.; Gawali, B.W. Classification of land use/land cover using artificial intelligence (ANN-RF). Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 964279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejasree, G.; Agilandeeswari, L. Land use/land cover (LULC) classification using deep-LSTM for hyperspectral images. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2024, 27, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Islam, R.; Uddin, P.; Ulhaq, A. Spectrally Segmented-Enhanced Neural Network for Precise Land Cover Object Classification in Hyperspectral Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Dragićević, S.; Li, S. Land-Use Change Detection with Convolutional Neural Network Methods. Environments 2019, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yang, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, B.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S. Land Use Classification of the Deep Convolutional Neural Network Method Reducing the Loss of Spatial Features. Sensors 2019, 19, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, H.A.H.; Kalantar, B.; Pradhan, B.; Saeidi, V.; Halin, A.A.; Ueda, N.; Mansor, S. Land Cover Classification from fused DSM and UAV Images Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.