Semantic Segmentation of Typical Oceanic and Atmospheric Phenomena in SAR Images Based on Modified Segformer

Highlights

- A semantic segmentation dataset covering 12 typical oceanic and atmospheric phenomena is constructed, using 2383 Sentinel-1 WV mode images and 2628 IW mode sub-images with 100 m resolution and 256 × 256 pixels.

- Our modified Segformer model named Segformer-OcnP (integrating improved ASPP, CA modules, and progressive upsampling), outperforms classic models like U-Net and original Segformer, achieving 80.98% mDice, 70.32% mIoU, and 86.77% OA.

- The dataset addresses the lack of diverse, multi-phenomenon SAR segmentation data, supporting AI-driven ocean–atmosphere observation research.

- Segformer-OcnP has improved segmentation accuracy for small-scale and complex phenomena, providing a tool for pixel-level recognition of oceanic and atmospheric processes.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dataset

2.1. Focused Phenomena

2.2. Dataset Construction

3. Methodology

3.1. Segformer-OcnP

3.1.1. Encoder

3.1.2. Decoder

3.2. Training Strategy

4. Results and Validation

4.1. Ablation Experiments Results

4.2. Overall Evaluation Results

4.3. Segmentation Results for Different Phenomena

4.4. Comparison with Visual Interpretation Results

4.5. Case Study

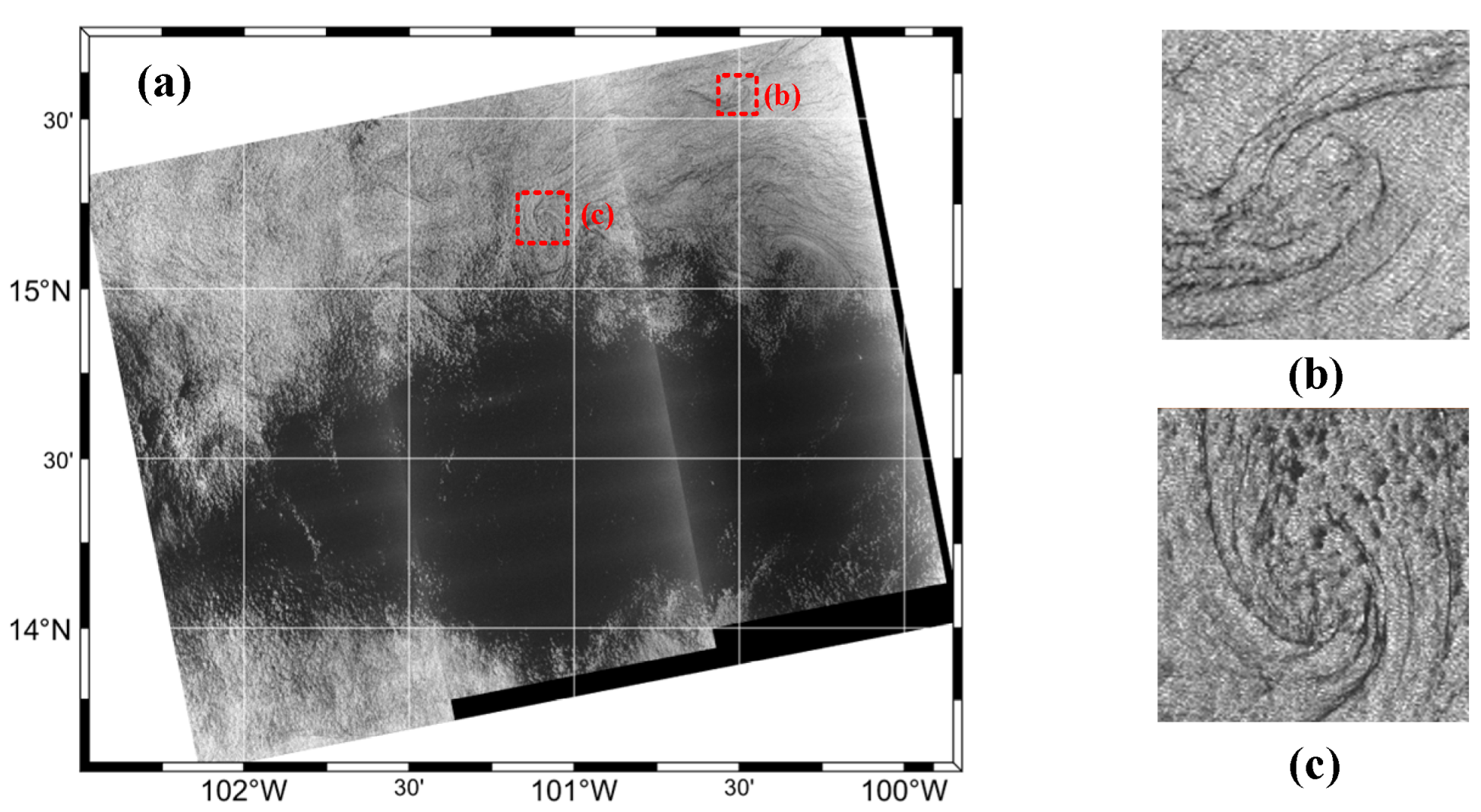

4.5.1. Oceanic Internal Wave

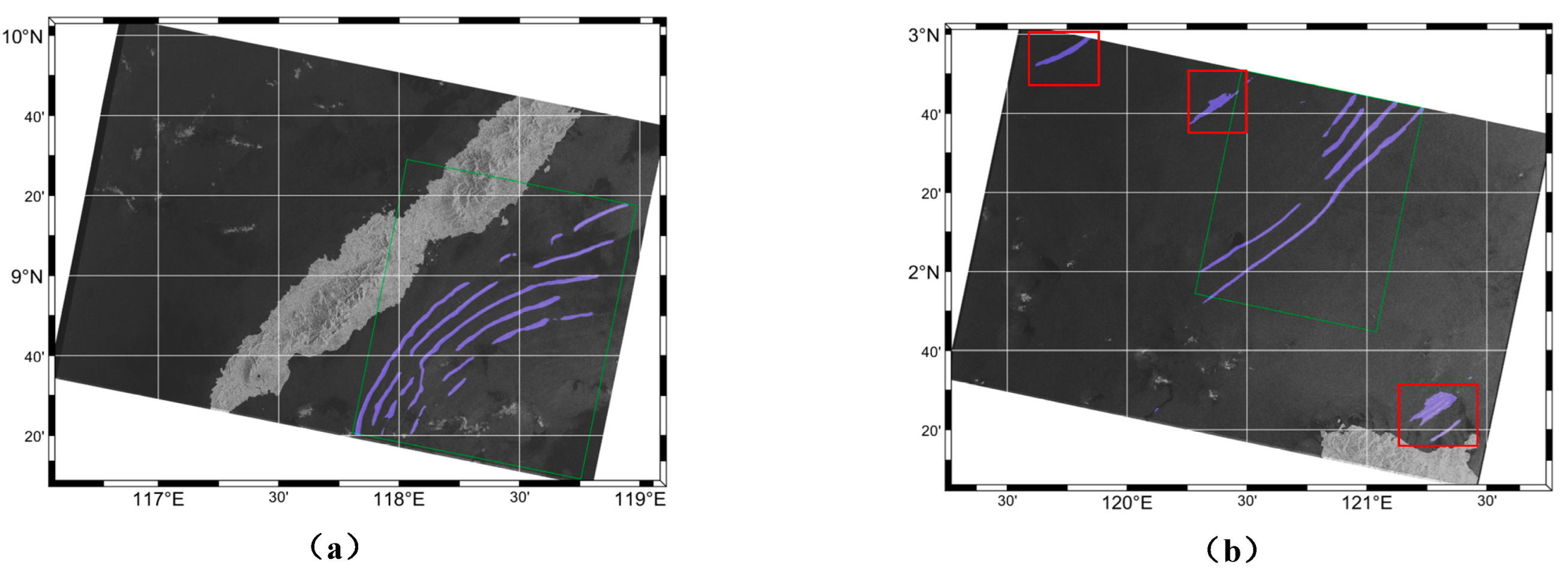

4.5.2. Rainfall

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deike, L. Mass Transfer at the Ocean–Atmosphere Interface: The Role of Wave Breaking, Droplets, and Bubbles. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2022, 54, 191–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, I.M. The Partitioning of the Poleward Energy Transport between the Tropical Ocean and Atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 2001, 58, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.Z.; Rasmusson, E.M. Measurements of the Atmospheric Mass, Energy, and Momentum Budgets Over a 500-Kilometer Square of Tropical Ocean. Mon. Weather Rev. 1973, 101, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, B.; Zheng, G.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, F. Deep-learning-based information mining from ocean remote-sensing imagery. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1584–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiyabi, R.M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Tameh, S.N.; Amani, M.; Jin, S.; Mohammadzadeh, A. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for Ocean: A Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 9106–9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, K.; Yoshida, T. On the Interpretation of Synthetic Aperture Radar Images of Oceanic Phenomena: Past and Present. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpers, W.; Huang, W. On the Discrimination of Radar Signatures of Atmospheric Gravity Waves and Oceanic Internal Waves on Synthetic Aperture Radar Images of the Sea Surface. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Yang, J. Typical Ocean Features Detection in SAR Images. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Workshop on Education Technology and Training & 2008 International Workshop on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, Shanghai, China, 21–22 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella, B.; Giancaspro, A.; Nirchio, F.; Pavese, P.; Trivero, P. Oil spill detection using marine SAR images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 3561–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topouzelis, K.; Kitsiou, D. Detection and classification of mesoscale atmospheric phenomena above sea in SAR imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 160, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Song, W.; He, Q.; Huang, D.; Liotta, A.; Su, C. Deep learning with multi-scale feature fusion in remote sensing for automatic oceanic eddy detection. Inform. Fusion 2019, 49, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Kim, J.; Vadivel, S.K.P.; Kim, D.-J. A study on classifying sea ice of the summer arctic ocean using sentinel-1 A/B SAR data and deep learning models. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2019, 35, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krestenitis, M.; Orfanidis, G.; Ioannidis, K.; Avgerinakis, K.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Oil Spill Identification from Satellite Images Using Deep Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, N.; Li, X.-M.; Gade, M.; Fu, H.; Min, S. Ocean eddy detection based on YOLO deep learning algorithm by synthetic aperture radar data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 307, 114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, F.; Dong, J.; Wang, S. Transferred Deep Learning for Sea Ice Change Detection From Synthetic-Aperture Radar Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1655–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasimoto-Beltran, R.; Canul-Ku, M.; Mendez, G.M.D.; Ocampo-Torres, F.J.; Esquivel-Trava, B. Ocean oil spill detection from SAR images based on multi-channel deep learning semantic segmentation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qi, K.; Ding, L.-Y. Stripe segmentation of oceanic internal waves in SAR images based on SegNet. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 8567–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Mouche, A.; Tandeo, P.; Stopa, J.E.; Longépé, N.; Erhard, G.; Foster, R.C.; Vandemark, D.; Chapron, B. A labelled ocean SAR imagery dataset of ten geophysical phenomena from Sentinel-1 wave mode. Geosci. Data J. 2019, 6, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, A.; Fablet, R.; Tandeo, P.; Husson, R.; Peureux, C.; Longépé, N.; Mouche, A. Semantic Segmentation of Metoceanic Processes Using SAR Observations and Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Ferreira, A.M.; Da Silva, J.C.B.; Magalhaes, J.M. SAR Mode Altimetry Observations of Internal Solitary Waves in the Tropical Ocean Part 1: Case Studies. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Xu, G.; Dong, C.; Yang, J.; Xia, C. Submesoscale eddies in the East China Sea detected from SAR images. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2021, 40, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Xu, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y. An Internal Waves Data Set From Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar467Imagery and Preliminary Detection. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2022EA002528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tandeo, P.; Mouche, A.; Stopa, J.E.; Gressani, V.; Longepe, N.; Vandemark, D.; Foster, R.C.; Chapron, B. Classification of the global Sentinel-1 SAR vignettes for ocean surface process studies. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 234, 111457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchaabane, A.; Peureux, C.; Soulat, F. A Labelled Dataset Description for SAR Images Segmentation; College Localisation Satellites: Ramonville Saint-Agne, France, 2022; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gade, M.; Byfield, V.; Ermakov, S.; Lavrova, O.; Mitnik, L. Slicks as indicators for marine processes. Oceanography 2013, 26, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, I.E.; Artamonova, A.V.; Manucharyan, G.E.; Kubryakov, A.A. Eddies in the Western Arctic Ocean From Spaceborne SAR Observations Over Open Ocean and Marginal Ice Zones. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 2019, 124, 6601–6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhlmacher, A.; Gade, M. Statistical analyses of eddies in the Western Mediterranean Sea based on Synthetic Aperture Radar imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 250, 112023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Chen, P.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, D.; Huang, Z.; Hou, X.; Cottrell, G. Understanding convolution for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, M.-M.; Feng, J. Strip Pooling: Rethinking Spatial Pooling for Scene Parsing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H.; et al. Rethinking Semantic Segmentation from a Sequence-to-Sequence Perspective with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, 18 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Catto, J.L.; Nicholls, N.; Jakob, C.; Shelton, K.L. Atmospheric fronts in current and future climates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 7642–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figshare. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/IWs_Dataset_v1_0/21365835 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Pradhan, R.K.; Markonis, Y.; Godoy, M.R.V.; Villalba-Pradas, A.; Andreadis, K.M.; Nikolopoulos, E.I.; Papalexiou, S.M.; Rahim, A.; Tapiador, F.J.; Hanel, M. Review of GPM IMERG performance: A global perspective. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 268, 112754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quankun, L.; Xue, B.; Xupu, G. A Dataset for Semantic Segmentation of Typical Oceanic and Atmospheric Phenomena from Sentinel-1 Images; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment | mDice (%) | mIoU (%) | OA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exp0: Segformer (Cross-entropy Loss) | 78.02 | 67.17 | 85.26 |

| Exp1: Segformer (Combined Loss) | 78.83 | 68.08 | 85.20 |

| Exp2: Exp1 + ASPP | 79.46 | 68.59 | 85.39 |

| Exp3: Exp2 + MPM | 79.92 | 69.18 | 85.45 |

| Exp4: Exp3 + CA | 80.31 | 69.71 | 86.41 |

| Exp5: Exp4 + Progressive Upsampling | 80.98 | 70.32 | 86.77 |

| Model | mDice (%) | mIoU (%) | OA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net [33] | 72.31 | 59.29 | 79.07 |

| DeepLabV3+ [34] | 78.81 | 68.04 | 84.93 |

| SETR [35] | 78.21 | 67.50 | 84.81 |

| Segformer [28] | 78.83 | 68.08 | 85.20 |

| Segformer-OcnP (Ours) | 80.98 | 70.32 | 86.77 |

| Model | AF | OF | RF | IC | SI | POW |

| U-Net | 49.35 | 57.06 | 74.84 | 46.10 | 95.02 | 79.9 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 61.17 | 64.81 | 84.17 | 44.01 | 99.31 | 84.33 |

| SETR | 63.18 | 63.86 | 87.17 | 34.93 | 99.27 | 83.05 |

| Segformer | 61.73 | 63.62 | 87.58 | 39.46 | 99.85 | 85.65 |

| Segformer-OcnP | 63.11 | 67.02 | 87.79 | 48.99 | 99.87 | 86.47 |

| Model | WS | LWA | BS | MCC | IWs | Eddy |

| U-Net | 86.65 | 85.61 | 85.32 | 80.25 | 82.42 | 45.17 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 92.69 | 89.11 | 90.67 | 84.68 | 86.99 | 63.87 |

| SETR | 91.72 | 89.99 | 90.78 | 84.71 | 84.64 | 65.18 |

| Segformer | 91.44 | 89.54 | 90.60 | 84.50 | 86.10 | 65.92 |

| Segformer-OcnP | 94.08 | 89.90 | 90.61 | 84.67 | 87.08 | 72.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Bai, X.; Hu, L.; Li, L.; Bao, Y.; Geng, X.; Yan, X.-H. Semantic Segmentation of Typical Oceanic and Atmospheric Phenomena in SAR Images Based on Modified Segformer. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010113

Li Q, Bai X, Hu L, Li L, Bao Y, Geng X, Yan X-H. Semantic Segmentation of Typical Oceanic and Atmospheric Phenomena in SAR Images Based on Modified Segformer. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010113

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Quankun, Xue Bai, Lizhen Hu, Liangsheng Li, Yaohui Bao, Xupu Geng, and Xiao-Hai Yan. 2026. "Semantic Segmentation of Typical Oceanic and Atmospheric Phenomena in SAR Images Based on Modified Segformer" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010113

APA StyleLi, Q., Bai, X., Hu, L., Li, L., Bao, Y., Geng, X., & Yan, X.-H. (2026). Semantic Segmentation of Typical Oceanic and Atmospheric Phenomena in SAR Images Based on Modified Segformer. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010113