Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A frequency-aware attention-based network (FANet) for tiny-object detection is proposed, incorporating two plug-and-play feature enhancement modules and a sample augmentation strategy (SAS); it achieves 24.8% mAP on AI-TOD and demonstrates consistent performance improvements on the VisDrone2019 and DOTA-v1.5 datasets.

- Our feature enhancement modules work on various two-stage detection frameworks with negligible complexity increase, boosting performance stably.

What are the implication of the main finding?

- Leveraging frequency-domain features compensates for weak spatial features of tiny objects in remote sensing images, offering a new technical path.

- SAS improves the few-shot category detection performance on tiny objects, and the plug-and-play modules support practical remote sensing applications.

Abstract

In recent years, deep learning-based remote sensing object detection has achieved remarkable progress, yet the detection of tiny objects remains a significant challenge. Tiny objects in remote sensing images typically occupy only a few pixels, resulting in low contrast, poor resolution, and high sensitivity to localization errors. Their diverse scales and appearances, combined with complex backgrounds and severe class imbalance, further complicate the detection tasks. Conventional spatial feature extraction methods often struggle to capture the discriminative characteristics of tiny objects, especially in the presence of noise and occlusion. To address these challenges, we propose a frequency-aware attention-based tiny-object detection network with two plug-and-play modules that leverage frequency-domain information to enhance the targets. Specifically, we introduce a Multi-Scale Frequency Feature Enhancement Module (MSFFEM) to adaptively highlight the contour and texture details of tiny objects while suppressing background noise. Additionally, a Channel Attention-based RoI Enhancement Module (CAREM) is proposed to selectively emphasize high-frequency responses within RoI features, further improving object localization and classification. Furthermore, to mitigate sample imbalance, we employ multi-directional flip sample augmentation and redundancy filtering strategies, which significantly boost detection performance for few-shot categories. Extensive experiments on public object detection datasets, i.e., AI-TOD, VisDrone2019, and DOTA-v1.5, demonstrate that the proposed FANet consistently improves detection performance for tiny objects, outperforming existing methods and providing new insights into the integration of frequency-domain analysis and attention mechanisms for robust tiny-object detection in remote sensing applications.

1. Introduction

Remote sensing images (RSIs) play a crucial role in a wide range of applications [1,2,3,4], including urban management, environmental monitoring, and maritime rescue. A core task of remote sensing images is the intelligent interpretation of objects of interest. However, due to the long imaging distance, large field of view, and limited spatial resolution inherent to remote sensing platforms, many critical targets—such as ships, vehicles, and airplanes—appear as tiny objects in the images (smaller than pixels) [5], which makes their detection particularly challenging.

Tiny-object detection in remote sensing faces three main challenges. First, tiny objects occupy only a few pixels with weak and inconspicuous spatial features, making them difficult to distinguish from complex backgrounds. Their small scale also leads to high sensitivity to localization errors: even slight deviations in bounding box regression can cause substantial changes in IoU. Second, variations in illumination, cloud cover, imaging altitude, and angle result in considerable intra-class variation. As illustrated in Figure 1, ships in the AI-TOD dataset [6] exhibit significantly different appearances depending on the scene context. Third, the number of instances per category is often highly imbalanced–in many datasets, one or two categories dominate while others are rare, leading to degraded detection performance for few-shot categories.

Figure 1.

Tiny objects in AI-TOD. (Left): Ships in open sea scenes. (Right): Ships near the port. Due to differences in imaging conditions and backgrounds, objects of the same category exhibit significant intra-class variation.

Typical universal object detection networks often enhance texture and boundary features to improve detection performance. However, for tiny objects, spatial features are extremely weak and the objects occupy only a few pixels, making it difficult to rely solely on spatial information for robust detection. To address this limitation, recent advances in frequency-domain analysis have shown that leveraging spectral information can effectively enhance discriminative features in remote sensing tasks. By utilizing frequency-domain features, models are able to better highlight object contours and textures, suppress background noise, and improve the representation of small targets.

Motivated by these findings, we propose FANet, a frequency-aware attention-based network for tiny-object detection in remote sensing images. Our method aims to address the insufficient spatial feature information of tiny objects and improve detection performance. In the feature pyramid network, we introduce a Multi-Scale Frequency Feature Enhancement Module, which divides feature maps into patches and applies frequency-domain weighting to adaptively enhance the texture and contour details of tiny objects while suppressing background noise. By designing multiple branches of Frequency Feature Enhancement Modules (FFEMs) with different patch sizes, our method further focuses on objects of various scales and adaptively enhances the frequency-domain features of different categories. In the RoI detection head, we propose a Channel Attention-based RoI Enhancement Module. By computing channel attention on the high-frequency response of RoI features, the module selects channels that better represent object characteristics, refining the RoI representation for subsequent classification and regression. Additionally, to address the sample imbalance in remote sensing tiny-object datasets, we perform sample augmentation strategy based on the statistical characteristics of different categories, expanding the training set for few-shot categories and further improving detection performance.

The contributions of this article are summarized as follows:

- The FANet designed for tiny-object detection in RSIs is proposed, which includes two plug-and-play modules that leverage specific frequency responses and high-frequency information of tiny objects to enhance detection performance.

- The MSFFEM is designed with multi-scale patchwise frequency-domain filtering to adaptively enhance texture and contour details of tiny objects while suppressing background noise.

- The CAREM is designed, which selectively learns feature channels reflecting the characteristics of tiny objects through high-frequency responses of RoI features, thereby strengthening RoI representation.

- The SAS is designed based on multi-directional flipping and redundancy filtering to address severe class imbalance in remote sensing datasets, significantly improving detection performance for few-shot categories.

- Extensive experiments on three public datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of our method, with both plug-and-play modules achieving consistent performance improvements with negligible computational overhead.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly reviews related works. Section 3 details the implementation of the proposed FANet. Section 4 presents the experimental settings. Section 5 details the ablation studies and results. Section 6 discusses the advantages and limitations of our method. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Tiny-Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images

Tiny object detection is a crucial research topic in remote sensing, as extremely small-scale objects are widely present in both aerial and satellite imagery. Early object detection frameworks, including Faster R-CNN [7], SSD [8], and earlier YOLO versions [9,10,11,12], were not specifically designed for tiny objects and often struggle when targets occupy only a few pixels with weak spatial features. To address the problem of insufficient spatial information, recent detectors have introduced dedicated mechanisms for small-object detection: YOLOv7 [13] and YOLOv9 [14] incorporate multi-scale feature aggregation and attention mechanisms. Feature pyramid networks (FPNs) [15] and their variants aggregate features from different layers to enhance small-object representation. For example, Liu et al. [16] introduced the Path Aggregation Network (PANet) utilizing a bidirectional feature aggregation path to enrich the feature hierarchy, and DetectoRS [17] proposes a recursive feature pyramid network, which builds more robust multi-scale feature representations through iterative fusion. Song el al. [18] proposed a boundary-aware feature fusion network (BAFNet) which leverages foreground and background clues with a dual-stream attention mechanism. Wu et al. [19] proposed a feature-and-spatial-aligned network (FSANet) to enhance the representation of tiny objects by aligning features and spatial information. However, in remote sensing applications, a practical limitation often overlooked is the preprocessing pipeline: very large images must be resized or cropped into smaller tiles before detection, which can degrade or even destroy tiny-object features regardless of the detector architecture.

To overcome these limitations, some studies have also explored the use of attention mechanisms and contextual information to further improve tiny-object detection [20,21]. For instance, context modeling modules, including global context blocks, non-local modules [22], and DETR-based detectors [23,24], have demonstrated the ability to enhance small-object representation by utilizing surrounding information. Zhang et al. [25] proposed a multistage enhancement network (MENet) which selectively aggregates valuable context information to improve the feature representation of tiny objects. Hu et al. [26] introduced a contextual feature enhancement network (CFENet) which integrates contextual information to help models focus on informative regions and suppress irrelevant background noise. Fusion and context-aware YOLO (FFCA-YOLO) [27] presents an effective feature enhancement and context-aware detector that suppresses background clutter and strengthens model features. DETR with Dynamic Query (DQ-DETR) [28] leverages density map prediction and contextual cues to enhance the quality of tiny-object queries, thereby improving query matching. While these approaches enhance the model’s ability to utilize surrounding information, they still rely heavily on spatial-domain features, which are inherently weak for tiny objects. Wang et al. [29] proposed an asymmetric patch attention fusion network (APAFNet) to merge high-level semantics and low-level spatial details with channel attention branch. Hu et al. [30] introduced a spatial–temporal patch-tensor model to address the challenges of tiny-object detection in infrared images with multi-frame attention information.

Another important research direction focuses on addressing the challenges of sample imbalance and few-shot learning in remote sensing tiny-object detection [31]. To mitigate this, data augmentation techniques, including super-resolution methods, synthetic sample generation, and GANs [32], are frequently employed to improve model generalization. Wang et al. [33] proposed SVDDD, which leverages diffusion models to synthesize new training samples, thereby enhancing model generalization and detection accuracy. Xiang et al. [34] introduced UniFusOD, a unified multi-modal fusion framework that integrates multi-granularity attention mechanisms to improve detection performance. However, these methods often introduce additional computational complexity and may not generalize well to all scenarios. On the other hand, some research emphasizes improving the quality of label assignment for tiny objects. Methods such as Normalized Gaussian Wasserstein Distance (NWD) [35] and Gaussian Receptive Field-based Label Assignment (RFLA) [36] introduce more suitable proposal similarity metrics and label assignment method for tiny objects, thereby improving the quality and recall of positive samples generated by the region proposal network (RPN). These approaches enhance the model’s focus on tiny objects and improve positive sample selection, but they do not fundamentally address the weak feature problem of tiny objects.

In summary, although existing methods have made progress by addressing multi-scale fusion, context modeling, and data imbalance, they are still limited by their reliance on spatial-domain features, which are insufficient for robust tiny-object detection in complex remote sensing scenes. This motivates the exploration of frequency-domain information as a complementary approach, and in this article, we propose a frequency-aware network to complementarily enhance tiny-object features.

2.2. Frequency-Domain Methods in Tiny-Object Detection

To address the limitations of spatial-domain methods, frequency-domain analysis has been introduced into computer vision, especially for remote sensing imagery. Recent works employed Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and wavelet transform to extract frequency components that are less sensitive to noise and illumination changes [37]. These methods revealed that high-frequency information is closely related to object boundaries and fine details, which are critical for tiny-object detection.

Building on this, recent studies have frequently integrated convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with Fourier transforms, enabling the combination of spatial features and frequency-domain information to guide visual tasks [38,39,40,41]. Unlike spatial-domain methods that rely on texture and edge features, frequency-domain approaches utilize spectral information to enhance discriminative features. While these approaches improve the detection of hard-to-distinguish objects, most are designed for general object detection and do not specifically target the unique challenges of tiny objects in remote sensing images.

Beyond DFT- and wavelet-based approaches, recent research has explored the use of learnable frequency filters and spectral attention mechanisms. Some works combine frequency-domain and spatial-domain features for complementary representation, improving robustness to occlusion and background clutter. For instance, Zhu et al. [42] enhance infrared tiny-object segmentation and detection by attention-weighted fusion of spectral features. Patro et al. [43] introduced SpectFormer, which replaces standard self-attention with spectral attention to capture feature representation in the frequency domain. Shi et al. [44] introduced a high-frequency spatial perception FPN (HS-FPN) which leverages high-frequency responses of tiny objects through attention mechanisms to improve detection performance.

However, it is crucial to clarify that frequency-domain transforms are mathematically invertible and preserve all information from the spatial domain. Therefore, any performance improvement from frequency-based methods does not stem from extra information in the frequency domain, but rather from how the frequency representation is processed. Specifically, the frequency domain provides a natural decomposition where high-frequency components correspond to edges and textures while low-frequency components represent smooth backgrounds. This decomposition enables more targeted feature manipulation: learnable frequency weighting can selectively enhance or suppress specific frequency bands, achieving effects similar to spatial filtering but with greater flexibility and interpretability. Motivated by these observations, we propose a frequency-aware attention-based network that exploits this property through adaptive frequency weighting and multi-scale aggregation, providing an effective mechanism for enhancing tiny-object features.

3. Proposed Method

In this section, we present the overall architecture of the proposed FANet, followed by detailed descriptions of its core modules: the MSFFEM for frequency-domain adaptive feature enhancement, the CAREM for channel attention-based RoI feature refinement, and the SAS designed to address class imbalance in remote sensing datasets.

3.1. Overview

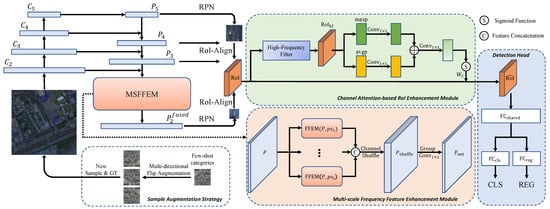

As illustrated in Figure 2, FANet is built upon the R-CNN object detection framework, consisting of a backbone network (ResNet-50) [45], a feature pyramid network (FPN) for multi-scale feature fusion, and a detection head. The key innovations of FANet are the integration of frequency-domain feature enhancement and channel attention-based RoI refinement, which are implemented as plug-and-play modules at both the feature map and RoI levels. Additionally, a multi-directional flip sample augmentation strategy is employed to balance the training data and improve the detection of few-shot categories.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed FANet. The network is built upon the R-CNN framework, with FPN incorporating the MSFFEM for frequency-domain feature enhancement at the feature map level, and the CAREM for channel attention-based RoI feature refinement at the RoI level. A sample augmentation strategy is employed to balance the training data, improving detection performance for few-shot categories.

3.2. Multi-Scale Frequency Feature Enhancement Module

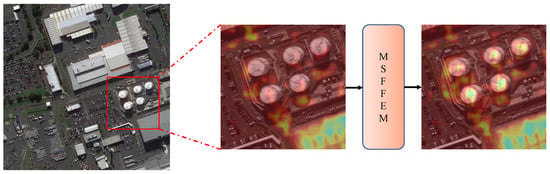

In tiny-object detection, the spatial features of objects are often weak and difficult to distinguish due to imaging limitations. Relying solely on spatial features is insufficient for robust detection, making frequency-domain features an important research direction. Inspired by previous works, we propose an MSFFEM to highlight the texture and contour details of tiny objects while suppressing background noise.

As shown in Figure 3, tiny objects in remote sensing images exhibit more distinctive representations in specific frequency bands. The frequency spectrum of the patch marked by the red circle is significantly different from other patches, indicating that tiny objects have unique spectral characteristics, such as texture and edge information. Therefore, by adaptively enhancing specific frequency bands that correspond to tiny objects, we can selectively strengthen tiny-object features and smooth the background. The details of the module are introduced in the following sections.

Figure 3.

(Left): Remote sensing image containing tiny object in the red box. (Right): Patchwise FFT spectrum visualization. The patch-based FFT reveals that tiny objects exhibit distinctive responses in specific frequency bands, highlighting their spectral characteristics and aiding in discriminative feature extraction.

3.2.1. Frequency Feature Enhancement Module

Since most objects occupy only a small proportion of pixels, we divide and rearrange the feature maps into patches, transforming the original feature map into , where and denote the patch size in height and width, and , denote the number of patches along the height and width, respectively. In our experiments, we generally set and to be equal, i.e., , which is a tunable hyperparameter that controls the trade-off between frequency resolution and spatial localization and deliberately chosen to be divisors of the feature map dimensions. The patch rearrange operation, denoted as , is formally defined as follows:

where P is the input feature map and p is the feature map with patch partition.

As tiny objects primarily correspond to lower-level feature maps, we apply frequency-domain enhancement exclusively to the feature map, while higher-level feature maps remain unchanged. Unless otherwise specified, subsequent operations on feature maps are performed on . It is worth noting that after passing through the backbone network and top-down FPN fusion, the feature map already incorporates both local details and contextual information from higher-level semantic features. Therefore, our frequency-domain processing inherently operates on features that combine object-interior information with surrounding context, and the adaptive frequency weighting learns to enhance the discriminative patterns arising from this combined representation. In addition, it is important to note that the patch partition operation itself does not introduce any spatial-domain feature transformation. The patches are directly fed into the frequency-domain analysis without any spatial convolution or attention applied at the patch level.

After rearranging the feature map, we perform a 2D Discrete Fourier Transform (2D-DFT) to obtain the spectrum map. The calculation of 2D-DFT is as follows:

where is the input patch, and is the corresponding frequency-domain representation.

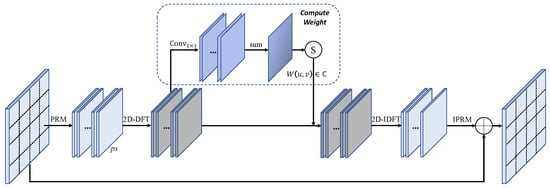

After obtaining the patchwise frequency spectrum, we fuse the multi-channel spectrum using a convolution (which takes C channels as input and outputs one channel) to produce a single-channel spectrum map. We then sum across the patch dimension to generate the final weight matrix , as illustrated in Figure 4. This process can be formulated as follows:

where denotes the sigmoid function, and . Here, the convolution is employed to aggregate frequency information across different channels. This allows the network to learn frequency-domain features of feature channels that are more conducive to object representation, thereby increasing the weights corresponding to these beneficial frequency components. Compared with the approach of directly multiplying by frequency weights, this method can adaptively learn the corresponding weights based on the intrinsic frequencies of different objects. The resulting weight matrix acts as an adaptive frequency-domain filter, enabling the network to selectively enhance discriminative frequency bands associated with tiny objects while suppressing low-frequency background noise:

Figure 4.

Illustration of the FFEM, which divides feature maps into patches, applies frequency-domain filtering, and enhances tiny-object representation.

Finally, we perform a 2D Inverse Discrete Fourier Transform (2D-IDFT) to restore the enhanced spatial features:

The enhanced patch features are then rearranged back to the original feature map through the inverse patch rearrange operation (IPRM) and combined with the initial feature map P via residual connection to obtain the final output feature:

3.2.2. Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

Since our FFEM enhances the feature map in the frequency domain, the receptive field of convolutional networks ensures that the area of the original object mapped onto the feature map is significantly larger than its original scale. Based on the receptive field calculations of ResNet, we can determine that for small objects with sizes ranging from 2 to 32 pixels, their corresponding effective receptive fields in are approximately 20 to 50 pixels. It is important to note that, given the small scale and weak features of our targets, selecting overly large patches may cause the objects to be overwhelmed by background noise. Conversely, choosing patches that are too small may lead to truncated object features, making it impossible to fully represent them.

Due to the fact that feature maps with different patch sizes tend to focus on objects of varying scales, and considering the large scale variation of objects in remote sensing datasets, we further design the MSFFEM, as illustrated in Figure 2. Specifically, the feature map is fed into several FFEM branches, each with a different patch size:

where denotes the patch size for the i-th branch, and is the corresponding enhanced feature map output. This multi-branch design enables the network to extract and enhance features at different spatial resolutions, making it more effective for handling objects of various scales. By fusing the outputs from multiple patch sizes, the model can adaptively capture both fine-grained details and broader contextual information, which is particularly beneficial for tiny-object detection in remote sensing images.

To effectively combine the multi-branch features, we employ a group convolution-based channel fusion strategy. First, we concatenate the outputs from all branches along the channel dimension, and channel shuffle is applied for group convolution.

where represents the group convolution module. This multi-scale feature fusion strategy enables the network to adaptively capture objects of different scales, further improving the representation capability for tiny objects in remote sensing images. Based on the characteristics of the dataset and the scale distribution of the objects, we set to [50, 100] for AI-TOD to cover the range of tiny to small objects. For other datasets with different image resolutions and object size distributions, the patch sizes are adjusted to [(24, 32), (48, 64)] for VisDrone2019 and [64, 128] for DOTA-v1.5, as detailed in Section 4.

3.3. Channel Attention-Based RoI Enhancement Module

The feature enhancement module described above applies frequency-aware attention to the entire feature map, which helps highlight object contours and suppress smooth background noise. However, since tiny objects typically occupy less than pixels, their proportion on the feature map is even smaller. Therefore, it is necessary to further focus on the representation of tiny objects within their corresponding RoIs. To address this, we propose a CAREM, which selectively learns feature channels related to object contours and textures by leveraging the high-frequency information of RoI features, as illustrated in Figure 2. Similar to MSFFEM, this module is plug-and-play and can be adapted to various object detection frameworks.

For the RoI feature map x obtained by RoI Align, we first extract its high-frequency information using a high-frequency filter, which has the same size of RoI features:

where and denote the 2D Discrete Cosine Transform (2D-DCT) and its inverse (2D-IDCT), respectively, and z is the Gaussian-weighted filter. Specifically, z is defined as follows:

where controls the bandwidth of the Gaussian filter, and is the Euclidean distance in the frequency-domain space from the frequency point to the high-frequency corner. Since the high-frequency information in the DCT spectrum is concentrated in the lower-right corner, the weights of the filter are smaller in the upper left region and larger in the lower-right region. In addition, we also experimented with a binary 0–1 indicator filter, and the specific forms of both filters are shown in Figure 5. In our experiments, we set to 2, which achieves the best performance, considering the RoI feature map size is . This design ensures that higher-frequency components are preserved while low-frequency background information is suppressed. By applying the high-frequency filter, irrelevant background information in the RoI features can be removed, increasing the proportion of tiny-object responses within the RoI.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the high-frequency filters used in CAREM. (Left): The 0–1 indicator filter. (Right): Gaussian-weighted filter. The Gaussian-weighted filter preserves high-frequency components in the lower-right corner, while the binary indicator filter sharply separates high and low frequencies.

To further aggregate channel information and learn the response of each channel to tiny objects, we compress the spatial dimension of the high-frequency features using channel attention [46]. Specifically, we obtain feature vectors via global max pooling and global average pooling:

where c denotes the channel index, and are the spatial dimensions. These pooled vectors are then passed through two convolution layers and summed, followed by a sigmoid activation to obtain channel weights:

where is the sigmoid function, and , are convolution operations. Finally, the channel weights are multiplied with the original RoI feature input to enhance the feature response for tiny objects:

This process ensures that each channel’s high-frequency response is more representative and less affected by clutter, thereby improving the detection performance for tiny objects.

3.4. Sample Augmentation Strategy

Analysis reveals that a widespread and significant issue in current remote sensing small-object datasets is the imbalance among different categories [5]. For example, in the AI-TOD dataset, vehicle instances account for 88.22% of the trainval set, while categories such as windmill and swimming pool each comprise less than 0.1%. This raises concerns about whether the features of few-shot categories are truly learned, and whether the dominant vehicle samples may be redundant.

To address the sample imbalance, we apply a multi-directional flip SAS before training. Specifically, for few-shot categories, we perform multi-directional flip operations (horizontal, vertical, and diagonal) on the corresponding images and annotations according to the number of instances, as shown in Table 1. For the dominant category, vehicle, we randomly remove a portion of the images to reduce redundancy. The instance counts for each category are also shown in Table 1 after selective augmentation and filtering. It can be observed that the differences between few-shot categories are reduced and the samples are more balanced.

Table 1.

Category proportion and augmentation multiples in the AI-TOD dataset. The category names are abbreviated as follows: AI—airplane, BR—bridge, ST—storage tank, SH—ship, SP—swimming pool, VE—vehicle, PE—person, WM—windmill.

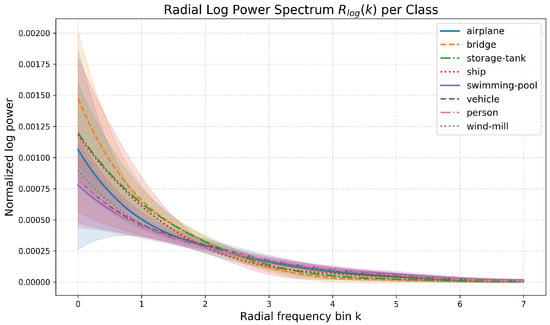

Moreover, to quantitatively analyze the frequency-domain characteristics of different object categories, we introduce the radially averaged log power spectrum as a metric. Specifically, for each object patch, we first apply a 2D Hann window to suppress boundary effects, then compute the 2D-DFT, and obtain the log power spectrum. The radial average is calculated by averaging the log power values over all pixels at the same radial frequency bin k, resulting in , which effectively reflects the distribution of frequency components for each category. The computation process is as follows:

where is the DFT of the patch, denotes the set of frequency points at radius k, and is the number of such points.

As shown in Figure 6, the analysis of for different categories reveals significant inter-class differences in frequency-domain distributions. This finding suggests that it is feasible to improve detection performance by selectively reducing redundant vehicle samples while not impacting other categories, and augmenting few-shot categories, thereby balancing the sample distribution. This observation further validates the effectiveness of our FANet, as it demonstrates that different categories exhibit distinct frequency-domain characteristics that can be leveraged for improved detection.

Figure 6.

Radially averaged log power spectrum for each object category in the AI-TOD dataset. The colored areas represent the standard deviation range. The results demonstrate significant inter-class differences in frequency-domain distributions.

The proposed SAS not only increases the diversity and number of samples for rare categories but also helps the model learn more robust and generalizable features for tiny objects. By balancing the sample distribution, the model is less biased toward dominant categories and can better capture the characteristics of few-shot objects. In addition, multi-directional flip augmentation simulates different observation angles in remote sensing scenarios, further enhancing the model’s adaptability to various scenes and viewpoints.

3.5. Training and Inference

3.5.1. Loss Function

In this section, we provide a comprehensive description of the loss functions utilized in FANet. Since our approach is built upon the vanilla-Faster R-CNN architecture, the overall loss comprises two main components: the RPN loss and the detection head loss.

The RPN loss consists of a classification loss and a regression loss, which are responsible for distinguishing foreground from background and for localizing candidate bounding boxes, respectively. Similarly, the detection head loss includes a classification loss for object category prediction and a regression loss for precise bounding box refinement. Specifically, the classification losses for both the RPN and detection head, denoted as and , are implemented using cross-entropy loss. The regression losses, and , employ the L1 loss function. By jointly optimizing these loss terms, FANet effectively enhances both proposal generation and object detection accuracy.

The classification and regression losses are formally defined as follows:

where and represent the predicted and ground-truth class labels, and denote the predicted and ground-truth bounding box coordinates, and and are normalization factors. The total loss function for FANet is denoted as follows:

where and are hyperparameters that balance the contributions of the classification and regression losses in both the RPN and detection head, both set to 1 in our experiments.

3.5.2. Inference

FANet is designed as an end-to-end detector. During inference, the model performs a forward pass on the input image to generate detection results, including the classification probability for each bounding box and its corresponding location. To further refine the output, postprocessing steps are applied: detection boxes with confidence scores below 0.05 are discarded, and Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) [47] with an IoU threshold of 0.5 is used to eliminate redundant overlapping boxes. This ensures that only high-confidence and non-overlapping detections are retained in the final results.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

Our proposed method is evaluated on three public datasets: AI-TOD, VisDrone2019, and DOTA-v1.5.

AI-TOD [6]: AI-TOD is a remote sensing dataset specifically designed for tiny-object detection. It contains 11,214 training images, 2804 validation images, and 14,018 test images, each with a resolution of pixels, covering 8 common remote sensing object categories. The average object size in AI-TOD is 12.8 pixels, which is significantly smaller than most existing remote sensing datasets. According to the definition of tiny objects mentioned earlier, the majority of targets in this dataset are tiny objects, making it suitable for our method.

VisDrone2019 [48]: The VisDrone2019 dataset (DET part) is a subset of the VisDrone dataset for UAV-based object detection, containing a large number of tiny objects of urban and rural scenes. The images are captured by UAVs at various locations, altitudes, and angles, and include 10 common object categories. The dataset consists of 6471 training images, 548 validation images, and 1610 test-dev images, and the images are basically pixels in size. VisDrone2019 is an excellent benchmark for evaluating tiny-object detectors, as it contains both extremely small and normal-sized objects.

DOTA-v1.5 [3]: DOTA is a large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images, with images collected from diverse sensors and platforms. It contains 16 common categories, 2806 images, and 403,318 instances. The training, validation, and testing sets are divided into proportions of 1/2, 1/6, and 1/3, respectively. Each image ranges in size from to 20,000 × 20,000 pixels and contains objects exhibiting a wide variety of scales, orientations, and shapes. Compared with DOTA-v1.0, extremely small instances (less than 10 pixels) are also annotated in DOTA-v1.5, making it more suitable for evaluating tiny-object detection performance. In this work, we utilize the horizontal bounding box annotations of the DOTA dataset for training and evaluation.

4.2. Implementation Details

All experiments are conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, and model training is based on PyTorch 2.0 [49] and CUDA 11.8. Our implementation is built upon the open-source MMDetection framework [50]. All the backbone models are pre-trained on ImageNet. All models are trained using the SGD optimizer with a momentum of 0.9, a weight decay of 1 × 10−4, and a batch size of 2. The total number of training epochs is set to 12 for all datasets, with a random seed of 2025 to ensure reproducibility. The initial learning rate is set to 0.005 and decays at the 8th and 11th epochs. Models are saved at every epoch. During training, the input image size is adjusted according to the characteristics of each dataset: for AI-TOD, for VisDrone2019, and for DOTA-v1.5. Additionally, the number of RPN proposals is set to 3000. It is worth noting that, due to the significant variation in image resolution within the DOTA dataset, we apply a sliding window cropping strategy to partition the original images into fixed-size patches before training. All the other parameters are set the same as default in MMDetection. The evaluation metrics for both datasets follow the AI-TOD benchmark. The above parameters are consistent across all experiments unless otherwise specified.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

In order to comprehensively and accurately evaluate the performance of our model, we adopt the average precision (AP) metric introduced by microsoft common objects in context (MSCOCO) [51] for both the AI-TOD and VisDrone2019 datasets. AP is calculated from the precision–recall curve and is defined as

where r denotes recall and is the corresponding precision.

Recall and precision are computed as follows:

where TP, FP, and FN represent the numbers of true positive, false positive, and false negative samples, respectively.

It should be noted that both precision and recall are calculated under a specific IoU threshold. Therefore, we report AP at different IoU thresholds, including and , which correspond to IoU thresholds of 0.5 and 0.75, respectively. The overall AP refers to the average AP over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05. Specifically, to further evaluate the model’s performance on small objects, the AI-TOD benchmark defines objects as very tiny, tiny, small, and medium with different size ranges: [2, 8], [8, 16], [16, 32], and [32, ] pixels. Accordingly, , , , and denote the AP for each size category.

Additionally, to assess the overall detection performance across all categories, we report the mean average precision (mAP), defined as

where C is the total number of categories, and is the average precision for category c.

5. Results

In this section, we first conduct comprehensive ablation studies and provide a detailed analysis and evaluation of each module, including MSFFEM, CAREM, and SAS, where all results are reported on the AI-TOD test set. Next, we report the performance of the proposed model on the datasets and compare it with other methods. Experimental results demonstrate that our plug-and-play modules consistently improve tiny-object detection performance in remote sensing images.

5.1. Ablation Studies

5.1.1. Faster R-CNN with RFLA as Baseline

To ensure a fair comparison, we select the RFLA method based on the vanilla-Faster R-CNN framework as our baseline. RFLA introduces a Gaussian Receptive Field-based Label Assignment strategy, which replaces the traditional IoU metric with RFLA for proposal matching. This allows the model to generate higher-quality proposals, making it more suitable for tiny-object detection. The traditional R-CNN detection framework combined with RFLA can effectively detect tiny objects without increasing model complexity or computational cost, making it an ideal baseline for evaluating tiny-object detection performance in our experiments.

Complexity and Inference Speed: Our proposed FANet leverages frequency-aware attention to compensate for the insufficient spatial information of tiny objects in remote sensing images. Compared with the baseline, our FANet brings 0.8% AP, 2% AP50, and 0.5% AP75 improvements. Importantly, the two plug-and-play modules proposed in FANet add negligible model parameters and computational complexity, which is competitive with our baseline in model size (41.16 M versus 41.17 M) and computation complexity (134.42 G versus 134.65 G). We also evaluated inference speed on RTX 4090 GPU; FANet runs at 38.7 FPS versus 42.5 FPS for the baseline with a 9% reduction, while still maintaining high real-time performance suitable for practical applications. Profiling in Section 3 shows that the majority of the additional inference latency arises from CAREM by RPN-dependent RoI proposals and larger effective batch processing, whereas the runtime impact of the MSFFEM is negligible.

Generalization analysis of different methods: To further validate the generality of our proposed modules, we conduct experiments on various detection frameworks and methods. As shown in Table 2, our plug-and-play modules can be seamlessly integrated into different object detection frameworks and consistently bring performance improvements, demonstrating stable and robust gains across various methods. Specifically, our modules improve AP50 by 1.6%, 2.6%, and 2% on vanilla-Faster R-CNN, NWD-RKA, and RFLA, respectively, and achieve 0.7% AP50 improvement on Cascade R-CNN.

Table 2.

Generalization of MSFFEM and CAREM across different methods on the AI-TOD test set. + Ours indicates the integration of both MSFFEM and CAREM. All label assignment methods are based on the Faster R-CNN framework. Floating-point operations per second, parameter counts, and frames per second are reported for each method.

5.1.2. Effectiveness of MSFFEM

We first experimentally verify the effectiveness of the proposed MSFFEM, which adaptively enhances the responses of tiny objects in specific frequency bands while smoothing background information for multi-scale objects. Compared with the baseline, our proposed MSFFEM with patch sizes of [50, 100] yields a notable performance improvement. As shown in Table 3, it brings improvements of 1.9%, 0.5%, 0.6%, and 1.0% in , , , and on different object scales, respectively. To provide an intuitive understanding of MSFFEM’s effect, we visualize the feature maps before and after MSFFEM processing using Eigen-CAM [53]. As shown in Figure 7, the visualization demonstrates that MSFFEM effectively enhances discriminative features for objects with distinctive frequency characteristics, such as storage tanks which exhibit clear geometric structures and regular patterns. These results demonstrate that MSFFEM can effectively enhance the feature representation of objects at different scales, particularly benefiting the detection of tiny objects in remote sensing images.

Table 3.

Ablation study on FFEM and multi-scale (MS) feature fusion. Results in bold indicate the best.

Figure 7.

Visualization of feature maps before and after MSFFEM processing using Eigen-CAM.

Impact of Patch Size: Patch size plays a crucial role in determining the frequency bands captured by the model. If the patch size is too large, the proportion of tiny-object features within each patch becomes very low, making them more susceptible to background noise and resulting in noisier frequency spectra. Conversely, if the patch size is too small, object features may be incomplete, potentially causing aliasing effects and preventing the model from fully extracting the frequency-domain information of the target. To investigate this, we conduct ablation experiments with different patch sizes on the AI-TOD dataset, where the feature map size is . We compare patch sizes of 10, 25, 50, and 100. As shown in Table 4, smaller patch sizes usually lead to higher APvt (8.8% and 9.1% for patch sizes 10 and 25, respectively), indicating that the model can better focus on very tiny objects, and when the patch size is 100, the model achieves the highest AP for medium-sized objects, boosted by 0.8% (32.1% versus 32.9%), which echoes our theory. For most patch sizes, AP50 is consistently improved, demonstrating that FFEM generally enhances the feature response for tiny objects in specific frequency bands.

Table 4.

Ablation study on patch size hyperparameter. Results in bold indicate the best.

Impact of Frequency Level: As discussed in the method section, the FPN neck selects different feature map levels according to the predicted object scale. For very tiny, tiny, and small objects, the model predominantly uses the feature map for prediction and classification during training, and only medium-sized objects are occasionally mapped to or higher-level feature maps. This means is mainly responsible for small-scale targets, while medium objects may leverage both and for improved representation. As shown in Table 5, the AP metrics from APvt to APm are all very similar between the two settings, and applying frequency enhancement to both and feature maps yields results with the overall AP even slightly lower than those obtained by enhancing only . This indicates that adding FFEM to multiple feature map levels does not necessarily lead to straightforward performance gains, primarily because the vast majority of objects are mapped to the feature map. Therefore, for reasons of computational efficiency and simplicity, we apply frequency enhancement only to the feature map in subsequent experiments.

Table 5.

Effect of frequency enhancement on different FPN levels. Results in bold indicate the best.

Effectiveness of Multi-Scale Feature Fusion: The previous ablation studies show that different patch size branches tend to focus on targets of different scales. In addition, we further investigate the individual and combined effects of FFEM and multi-scale fusion on detection performance, as shown in Table 3. When only the FFEM with patch size 50 is used to enhance the feature map, AP, AP50, and AP75 are improved by 0.6%, 1.4%, and 0.6%, respectively. After multi-branch FFEMs are fused, the model achieves further improvements across objects of different scales, demonstrating the effectiveness of multi-scale feature fusion for robust tiny-object detection.

5.1.3. Effectiveness of CAREM

As described in Section 3, the proposed CAREM first extracts the high-frequency responses of RoI features, and then applies channel attention weighting to selectively enhance channels that more accurately represent tiny-object characteristics, while suppressing channels biased toward background and semantic-level features. As reported in Table 6, compared with the baseline, the introduction of both the high-frequency filter and the channel attention module yields 0.8% AP, 1.2% AP50, and 1.0% APvt improvements. This result demonstrates that CAREM can effectively extract high-frequency response feature maps and adaptively learn channel features that are more relevant to tiny-object representation, thereby further enhancing RoI features.

Table 6.

Ablation study of high-frequency filters and channel attention modules (CAMs) on RoI features. Results in bold indicate the best.

Impact of the Gaussian Filter Bandwidth σ: We also investigate the effect of the bandwidth parameter in the Gaussian-weighted filter on detection performance. As shown in Table 7, when is small, the filter removes most of the low-frequency background information, making the representation of tiny objects more prominent and resulting in significant improvements in APvt and APt. Conversely, when is large, the filter retains more low-frequency information, leading to smoother filtering effects and relatively weaker improvements for tiny-object detection. In our experiments, setting to 2 yields the best results, with AP increased by 0.8%, AP50 by 1.2%, and APvt by 1%.

Table 7.

Impact of Gaussian filter bandwidth () on detection performance. Results in bold indicate the best.

Effectiveness of the High-Frequency Filter: Considering the annular frequency characteristics of 2D spectrum maps and the need to avoid completely suppressing low-frequency components, we adopt a Gaussian-weighted filter. We also explore the impact of using different filters and no filter (i.e., all weights set to 1) on detection performance, as shown in Table 6. A 0–1 filter refers to a binary mask that retains high-frequency components while completely removing low-frequency components, defined as follows:

where are frequency coordinates, are the height and width of the DCT spectrum (which match the size of the RoI feature map), and controls the cutoff frequency. Following the conclusions of previous work [44] and considering the scale of RoI features, we set to 0.3 in our experiments. Experimental results show that when using a 0–1 filter or no filter, even in combination with the channel attention module, the model’s AP is slightly lower than that achieved with the Gaussian-weighted filter. This indicates that the Gaussian filter can better preserve useful high-frequency information while suppressing irrelevant background, leading to more effective feature enhancement. As previously discussed, the 0–1 indicator filter completely removes low-frequency information and sharply separates high and low frequencies, which may result in the loss of some texture details. In contrast, the Gaussian filter smoothly retains part of the low-frequency information, thus achieving better overall performance.

Effectiveness of the Channel Attention Module: By applying channel attention weighting to the frequency responses of RoI features, the model can selectively learn specific channel features and strengthen its representation of tiny objects. To further investigate the effectiveness of the channel attention module, we apply it solely to the initial RoI features without any frequency filtering. As shown in Table 6, when no filter is used but the channel attention module is applied, AP and improve by 0.3% and 1.0%, respectively, compared to the baseline. This confirms that channel attention based on RoI features can indeed adaptively learn relevant channel representations.

Overall, these ablation experiments demonstrate that both the high-frequency filter and channel attention modules contribute to improved detection performance for tiny objects. The Gaussian filter is particularly effective in extracting discriminative high-frequency features, while channel attention further enhances the representation of tiny objects within RoIs. The combination of these modules enables the network to focus on informative channels and suppress background noise, leading to more robust and accurate detection results.

5.1.4. Effectiveness of SAS

Based on the multi-directional flip SAS proposed, we expand the few-shot categories and randomly filter out redundant vehicle samples. Experimental results show that this strategy effectively balances the category distribution and significantly improves the detection performance for few-shot categories, as detailed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Effect of SAS and vehicle instance reduction on detection performance. We report the class-wise detection results with AP metrics under different IoU thresholds. Category abbreviations are defined in Table 1. denotes the proportion of retained vehicle samples, and indicates the corresponding number of vehicle instances. Results in bold indicate the best.

It can be observed that multi-directional flip augmentation for few-shot categories leads to substantial improvements in , , , and , with increases of 8.3%, 5.8%, 10.9%, and 4.8%, respectively. This is mainly because the initial training set contains very few samples for these categories, and the dominant vehicle category has an overwhelming number of instances, making it difficult for the model to learn stable features for few-shot objects. After or augmentation, the model can better capture the characteristics of these objects. Additionally, multi-directional flip augmentation simulates different remote sensing observation angles, enhancing the model’s robustness to scene and viewpoint variations.

For categories such as , , and , the improvement is less than 1.2%. This is because these categories already have sufficient samples, and further augmentation yields diminishing returns. Moreover, some categories, such as storage tank (ST), have high intra-class similarity and distinctive features (e.g., rotational invariance), so conventional augmentation strategies have limited impact.

Impact of Sample Redundancy: We also investigate the redundancy of vehicle samples by progressively reducing their proportion and comparing detection performance. As shown in Table 8, reducing vehicle instances from 369 k to 163 k results in a decrease in from 24.6% to 21.3%, slightly below the baseline. Moreover, for both few-shot categories (AI, BR, SP, WM) and normal categories (ST, SH, PE), the model’s detection performance does not show any significant decline. Compared to the baseline, there are notable improvements for few-shot categories and at least comparable results for normal categories. This outcome further demonstrates that the inter-class spectral differences among various object categories are substantial, while intra-class similarities also exist. In our experiments, the number of vehicle instances remains much higher than other categories, and the model maintains robust detection performance for vehicle objects.

5.1.5. Effectiveness of MSFFEM, CAREM, and SAS

To comprehensively validate the effectiveness of each proposed module, we conduct detailed ablation studies comparing the MSFFEM, CAREM, and the SAS, as summarized in Table 9. The results show that both the MSFFEM and CAREM, when used independently, improve by 0.6% and 1.2% compared to the baseline (50.4%→51.0%, 50.4%→51.6%). When both plug-and-play modules are combined, increases by 2%, indicating that MSFFEM and CAREM are complementary. Specifically, MSFFEM adaptively highlights the feature maps corresponding to tiny objects through spectral weighting, while simultaneously smoothing and suppressing low-frequency background components. CAREM further refines the RoI representation by leveraging high-frequency responses, making the features of tiny objects more prominent. Moreover, when the SAS is incorporated to enhance the detection performance of few-shot categories, both modules also yield improvements of 0.4% in AP and 1.7% .

Table 9.

Detailed ablations of MSFFEM, CAREM, and SAS on AI-TOD test set. Results in bold indicate the best.

Overall, these ablation experiments demonstrate that the proposed MSFFEM, CAREM, and SAS are effective and complementary. Their combination enables the network to adaptively enhance tiny-object features, suppress background noise, and address sample imbalance, resulting in robust and accurate detection performance across various categories. Furthermore, we conduct ablation experiments on the VisDrone2019 and DOTA-v1.5 datasets to further validate the generalization capability of the two plug-and-play feature enhancement modules, with results presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Ablation studies on VisDrone2019 and DOTA-v1.5 validation sets. Results in bold indicate the best.

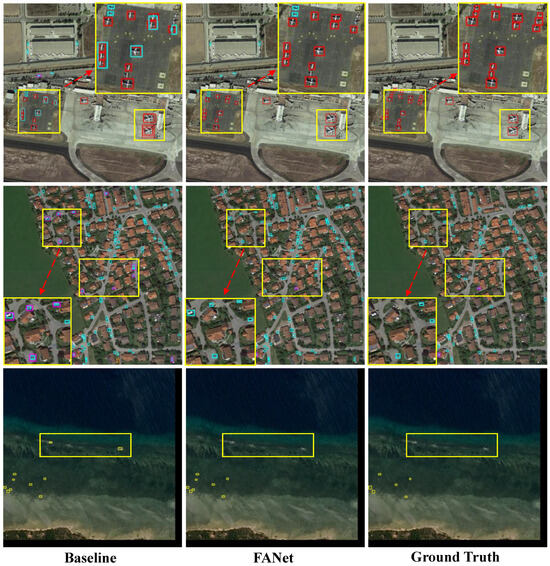

For visualization results, Figure 8 compares the detection results of FANet with the baseline Faster R-CNN w/ RFLA over the score threshold of 0.3 and NMS IoU threshold of 0.5. It can be seen that, by accurately enhancing features in the frequency domain, our FANet effectively reduces false positives in challenging scenarios, such as ships in open sea areas and airplanes or swimming pools in complex scenes.

Figure 8.

Qualitative comparison of detection results on the AI-TOD test set. From left to right: baseline results, FANet results, and ground truth. Highlighted regions show that FANet produces fewer false positives and more accurate detections compared to the baseline, as frequency-domain enhanced features better emphasize the characteristics of tiny objects and help suppress false alarms.

5.2. Comparisons with Other Methods

5.2.1. Results on AI-TOD Dataset

As shown in Table 11, we compare our FANet with various other methods on the AI-TOD test set, including anchor-based detectors (Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet, Cascade R-CNN, DetectoRS, etc.) and anchor-free detectors (FCOS, M-CenterNet, FSANet, etc.). All the other methods are trained with the same 1x training schedule for fair comparison. It is noted that results of anchor-based and anchor-free methods are mainly obtained from [19,36]. Under the same settings, FANet outperforms most previous methods and achieves better results than the baseline Faster R-CNN w/ RFLA. Without sample augmentation, FANet achieves an AP of 21.4%, and with SAS, the AP increases to 24.8%.

Table 11.

Comparison of the proposed FANet with previous methods on AI-TOD test set. All methods were trained for 12 epochs. Red denotes the best results, and blue second-best. Note that † indicates method reproduced, ‡ indicates method trained with SAS, and FCOS* means using P2–P6 of FPN.

Both the MSFFEM and CAREM modules in FANet are plug-and-play and can be integrated into most object detection frameworks. It is important to acknowledge the fundamental challenges associated with extremely tiny objects in AI-TOD. Objects of the very tiny scale contain very limited intrinsic information, and their detection inevitably relies on contextual cues from surrounding structures. Additionally, annotation uncertainty becomes significant at such scales: slight variations in bounding box placement can substantially affect IoU calculations, leading to evaluation instability. Compared to the baseline, FANet achieves improvements of 0.8% in AP and 2.0% in AP50 without SAS, and 4.2% in AP and 7.7% in AP50 with SAS. RFLA enhances the number of positive samples in RPN proposals through RFD score and hierarchical label assignment, improving RoI feature representation to some extent. However, it still suffers from feature mixing and background noise interference. Our MSFFEM and CAREM further enhance feature maps and RoI representations, leading to superior performance in tiny-object detection. Moreover, Figure 9 presents qualitative detection results of our FANet on the AI-TOD dataset. For sparse scenes such as open sea areas, the spatial features of ships are extremely weak and difficult to distinguish. Similarly, in complex scenes with dense objects, tiny targets are also easily affected by background noise. By incorporating frequency-domain feature enhancement, our method can better highlight the characteristics of tiny objects, making them more distinguishable from the background. The results demonstrate that FANet achieves robust and superior performance in these challenging scenarios, effectively detecting tiny objects even in low-contrast and noisy environments.

Figure 9.

Qualitative detection results achieved by our FANet on AI-TOD test set. One color stands for one object class. We could see that FANet demonstrates strong capability in detecting tiny objects with weak features in complex and dense scenes.

5.2.2. Results on VisDrone2019 and DOTA-v1.5 Datasets

We compare the detection performance of our FANet with several representative methods on the VisDrone2019 and DOTA-v1.5 validation sets, including both one-stage detectors (RetinaNet, FCOS) and two-stage detectors (Faster R-CNN, Cascade R-CNN, DetectoRS). Table 12 presents detailed AP metrics under different IoU thresholds. It is important to note that, due to the statistical characteristics of these two datasets, the SAS was not applied; thus, we only evaluate the combined effect of MSFFEM and CAREM. Additionally, since the image resolution and object size distribution differ from those in AI-TOD, we adjusted the multi-scale patch sizes in MSFFEM accordingly. Based on the input feature map size during training, we set the MSFFEM patch sizes to [(24, 32), (48, 64)] for VisDrone2019 and [64, 128] for DOTA-v1.5.

Table 12.

Comparison of detection performance on VisDrone2019 and DOTA-v1.5 validation sets. All methods were trained for 12 epochs. Red denotes the best results, and blue second-best. Results of previous methods were reproduced. Note that FCOS* means using P2–P6 of FPN.

The results show that our proposed model achieves consistent improvements across most metrics. Compared with the baseline, FANet improves and by 0.8% and 0.5% on VisDrone2019, 1.0% and 0.9% on DOTA-v1.5, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of frequency-domain feature enhancement and channel attention mechanisms for tiny-object detection in UAV-based remote sensing images. Furthermore, we visualize qualitative detection results on VisDrone2019, as shown in Figure 10. For UAV perspectives, due to the lower flight altitude, the images contain more occlusions and complex backgrounds, as well as a wide variety of object categories and significant scale variations. With frequency-domain feature enhancement, our FANet effectively improves the representation capability for tiny objects, achieving robust detection performance even in these challenging scenarios.

Figure 10.

Qualitative detection results achieved by our FANet on VisDrone2019 val set. One color stands for one object class.

6. Discussion

6.1. Analysis of Effectiveness

Our experimental results reveal that frequency-domain enhancement is most effective when objects possess distinguishable boundary and texture features that manifest as characteristic high-frequency responses. For instance, on AI-TOD, FANet achieves notable improvements for categories such as storage tanks and ships, which exhibit clear geometric structures and contrast against their backgrounds.

However, the improvements are more modest for very tiny objects where the intrinsic information is fundamentally limited—at such scales, detection inevitably relies on contextual cues rather than object-interior features. The varying effectiveness across different object scales (reflected in vs. ) suggests that frequency-domain enhancement provides greater benefits when sufficient spatial extent exists for meaningful spectral analysis.

Furthermore, the consistent improvements observed across multiple datasets and detection frameworks demonstrate the generalization capability of our approach. The plug-and-play nature of MSFFEM and CAREM allows seamless integration into existing detection pipelines without architectural modifications, making our method practical for real-world applications.

6.2. Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of the current work that warrant discussion: First, for very tiny objects, the intrinsic information within the object region is fundamentally limited, and detection performance inevitably depends on contextual cues from surrounding structures. While our frequency-domain enhancement helps highlight object boundaries, it cannot create information that does not exist in the original features. Second, the effectiveness of FANet may vary when contextual patterns change significantly across different scenes or domains, as the learned frequency weights are optimized on specific training distributions. Third, our current approach focuses on static images; incorporating temporal information from image sequences could potentially provide additional cues for tiny object detection.

7. Conclusions

In this article, we propose a novel frequency-aware attention-based tiny-object detector, namely FANet, to enhance tiny-object detection in remote sensing images from the perspective of spectral information. Specifically, we introduce two plug-and-play modules to address the limitations of conventional spatial feature extraction. The MSFFEM adaptively highlights the contour and texture representations of tiny objects while smoothing background information. The CAREM further improves the representation of RoI features by selectively emphasizing the texture details of tiny objects based on high-frequency responses. Additionally, to tackle the sample imbalance commonly found in remote sensing tiny-object datasets, we propose a multi-directional flip SAS, which significantly boosts the detection performance for few-shot categories. Furthermore, extensive experiments demonstrate that FANet consistently improves detection performance across all modules, with each component complementing and reinforcing the others.

In summary, FANet demonstrates that frequency-domain analysis offers a valuable complementary perspective for tiny-object detection in remote sensing images. And in future work, we will explore domain adaptation strategies to improve generalization across diverse remote sensing scenarios and investigate the integration of temporal characteristics in sequential imagery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.; methodology, Z.W., Y.L. (Yuhan Liu) and Y.L. (Yuan Li); software, Z.W.; validation, Z.W.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, Z.W.; resources, Z.W.; data curation, Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Z.W., P.L., Y.L. (Yuhan Liu), J.C., X.X., Y.L. (Yuan Li), H.W., Y.Z. and G.Z.; visualization, Z.W.; supervision, Z.W. and Y.L. (Yuhan Liu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available via the following links: (1) AI-TOD at https://github.com/jwwangchn/AI-TOD (accessed on 14 May 2025); (2) VisDrone at https://github.com/VisDrone/VisDrone-Dataset(accessed on 14 May 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheng, G.; Han, J. A survey on object detection in optical remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 117, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Tuia, D.; Mou, L.; Xia, G.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F. Deep learning in remote sensing: A comprehensive review and list of resources. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J. DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3974–3983. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object Detection in 20 Years: A Survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Yuan, X.; Yao, X.; Yan, K.; Zeng, Q.; Xie, X. Towards Large-Scale Small Object Detection: Survey and Benchmarks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 13467–13488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Guo, H.; Zhang, R.; Xia, G. Tiny Object Detection in Aerial Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 3791–3798. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Proceedings of the 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Proceedings of the 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S.; Chen, L.C.; Yuille, A. Detectors: Detecting objects with recursive feature pyramid and switchable atrous convolution. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 10213–10224. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Zhou, M.; Luo, J.; Pu, H.; Feng, Y.; Wei, X. Boundary-Aware Feature Fusion with Dual-Stream Attention for Remote Sensing Small Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5600213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Pan, Z.; Lei, B.; Hu, Y. FSANet: Feature-and-Spatial-Aligned Network for Tiny Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5630717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Proceedings of the 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Ni, L.M.; Shum, H.-Y. DINO: DETR with Improved DeNoising Anchor Boxes for End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Wang, G.; Han, X.; Tang, X. Multistage Enhancement Network for Tiny Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5611512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Chen, S.B.; Tang, J. CFENet: Contextual Feature Enhancement Network for Tiny Object Detection in Aerial Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4703113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, P.; Yan, J. FFCA-YOLO for Small Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5611215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.X.; Liu, H.I.; Shuai, H.H.; Cheng, W.H. DQ-DETR: DETR with Dynamic Query for Tiny Object Detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Proceedings of the 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 290–305. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lei, B.; Hu, Y. APAFNet: Single-Frame Infrared Small Target Detection by Asymmetric Patch Attention Fusion. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 7000405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y. Infrared Dim and Small Target Detection from Complex Scenes via Multi-Frame Spatial-Temporal Patch-Tensor Model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisantal, M.; Wojna, Z.; Murawski, J.; Naruniec, J.; Cho, K. Augmentation for small object detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosquet, B.; Cores, D.; Seidenari, L.; Brea, V.M.; Mucientes, M.; Bimbo, A.D. A full data augmentation pipeline for small object detection based on generative adversarial networks. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 133, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Pan, Z.; Wen, Z. Svddd: Sar vehicle target detection dataset augmentation based on diffusion model. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Zhou, G.; Niu, B.; Pan, Z.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Wen, Z.; Qi, J.; Gao, W. Infrared-Visible Image Fusion Meets Object Detection: Towards Unified Optimization for Multimodal Perception. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Yu, L.; Xia, G.-S. Detecting tiny objects in aerial images: A normalized Wasserstein distance and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Yu, L.; Xia, G.S. RFLA: Gaussian receptive field based label assignment for tiny object detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Proceedings of the 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 526–543. [Google Scholar]

- Finder, S.E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet Convolutions for Large Receptive Fields. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Proceedings of the 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Li, B.; Tang, L.; Kuang, S.; Wu, S.; Ding, S. Detecting Camouflaged Object in Frequency Domain. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 4504–4513. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, R.; Sun, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y. Frequency Perception Network for Camouflaged Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; 2023; pp. 1179–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Fu, M.; Cao, J.; Dong, J.; Du, Q. Adaptive Frequency Enhancement Network for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5619415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, G.; Li, L.; Xie, X.; Ren, J. Frequency-Domain Guided Swin Transformer and Global-Local Feature Integration for Remote Sensing Images Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5612611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Fan, F.; Huang, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, X. Toward Robust Infrared Small Target Detection via Frequency and Spatial Feature Fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 2001115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, B.N.; Namboodiri, V.P.; Agneeswaran, V.S. SpectFormer: Frequency and Attention is what you need in a Vision Transformer. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Hu, J.; Ren, J.; Ye, H.; Yuan, X.; Ouyang, Y.; He, J.; Ji, B.; Guo, J. HS-FPN: High Frequency and Spatial Perception FPN for Tiny Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirty-Seventh Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Fifteenth Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 6896–6904. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Neubeck, A.; Van Gool, L. Efficient non-maximum suppression. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR’06), Hong Kong, China, 20–24 August 2006; Volume 3, pp. 850–855. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Du, D.; Bian, X.; Fan, H.; Hu, Q. Detection and Tracking Meet Drones Challenge. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 7380–7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Pang, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, S.; Feng, W.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; et al. MMDetection: Open MMLab Detection Toolbox and Benchmark. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2014, Proceedings of the 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade R-CNN: Delving Into High Quality Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6154–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, M.B.; Yeasin, M. Eigen-CAM: Class Activation Map using Principal Components. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]