Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We developed a deep learning framework to map Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) in the DRC, supported by a pseudo-ground-truth dataset derived from ASM field observations through a multi-stage processing pipeline.

- The Late Fusion model combining Planet-NICFI optical and Sentinel-1 SAR data achieved the best performance (F1 = 0.73; overall accuracy = 88.4%) for ASM detection.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The integration of optical and SAR data enhances ASM detection under conditions of limited ground truth and persistent cloud cover.

- The resulting high-resolution maps can provide an operational tool for regional monitoring, policy support, and sustainable resource management.

Abstract

Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) significantly impacts the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) socio-economic landscape and environmental integrity, yet its dynamic and informal nature makes monitoring challenging. This study addresses this challenge by implementing a novel deep learning approach to map ASM sites across the DRC using satellite imagery. We tackled key obstacles including ground truth data scarcity, insufficient spatial resolution of conventional satellite sensors, and persistent cloud cover in the region. We developed a methodology to generate a pseudo-ground truth dataset by converting point-based ASM locations to segmented areas through a multi-stage process involving clustering, auxiliary dataset masking, and manual refinement. Four model configurations were evaluated: Planet-NICFI standalone, Sentinel-1 standalone, Early Fusion, and Late Fusion approaches. The Late Fusion model, which integrated high-resolution Planet-NICFI optical imagery (4.77 m resolution) with Sentinel-1 SAR data, achieved the highest performance with an average precision of 71%, recall of 75%, and F1-score of 73% for ASM detection. This superior performance demonstrated how SAR data’s textural features complemented optical data’s spectral information, particularly improving discrimination between ASM sites and water bodies—a common source of misclassification in optical-only approaches. We deployed the optimized model to map ASM extent in the Mwenga territory, achieving an overall accuracy of 88.4% when validated against high-resolution reference imagery. Despite these achievements, challenges persist in distinguishing ASM sites from built-up areas, suggesting avenues for future research through multi-class approaches. This study advances the domain of ASM mapping by offering methodologies that enhance remote sensing capabilities in ASM-impacted regions, providing valuable tools for monitoring, regulation, and environmental management.

1. Introduction

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of raw minerals. However, this wealth did not translate into prosperity for the population. Instead, it has often been source of conflicts, resulting in the so-called “wealth paradox” [1]. This refers to the phenomenon where countries rich in natural resources, such as minerals, often experience high levels of poverty and conflict. In the case of the DRC, the country is abundant in minerals like gold, diamonds, and coltan. Despite this wealth, the country has been plagued by poverty, violence and instability for decades. The wealth paradox in the DRC highlights the complex relationship between natural resource wealth and development. While mineral resources have the potential to contribute to economic growth and prosperity, their mismanagement and the presence of conflict can compromise these benefits and perpetuate poverty and instability. At the heart of this problematic context there is Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM). The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) defined ASM as mining activities carried out by individuals, groups, families, or cooperatives which are primarily characterized by low level of mechanization and technology, minimal investment and are substantially based on manual labour. Differently from the more industrialized mining practices, ASM is often associated with poverty and informality (https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/9268IIED.pdf, IIED, accessed on 1 November 2024), and its rapid expansion and often informal nature pose significant environmental and social challenges. In the Eastern DRC, the part of the country with the greatest concentration of ASM sites, 90% of mining activities acts as “informal”, meaning that it operates outside formal legal and regulatory framework [2], leading to environmental degradation, deforestation, and conflicts over land and resources [3]. Despite these significant challenges, ASM also has the potential to contribute to local economic development and poverty reduction if properly regulated and supported [2]. As shown by [4], ASM represents a significant livelihood for millions of people in developing countries, including sub-Saharan Africa and particularly in the DRC, where it is estimated to provide livelihoods for more than 1 million of people [4]. ASM’s contribution to local economies and its significant environmental impact underscore the urgent need for effective regulation and formalization. Ref. [5] clarified the crucial role of formalization in transforming ASM from an extralegal to a legally recognized activity, which is pivotal for mitigating its environmental impacts and enhancing its socio-economic benefits.

The challenges posed by ASM in the DRC stress the need to map its spatial extent. The accurate mapping of the extent of ASM provides insights into their scale, distribution, and environmental consequences. Such a deep understanding of the ASM landscape would empower stakeholders with the knowledge required for informed decision-making and the implementation of targeted interventions [6]. Remote sensing technologies have been pivotal in detecting and mapping ASM activities. While numerous studies have leveraged optical data from platforms like Sentinel-2 [7,8,9,10], the recent availability of high-resolution satellite imagery (HRSI) from Planet, in collaboration with Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI), has opened new prospects. In fact, this high-resolution imagery can potentially enhance the accuracy in mapping the mining extent. Moreover, the advent of deep learning, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which are designed to process images [11], has brought in an innovative era in remote sensing. These models, able to learn and extract features from satellite and UAV imagery, have demonstrated high accuracy in a variety of tasks, including land cover classification [12,13] and change detection [14,15]. Specifically, in the context of mapping ASM extents, CNNs have consistently outperformed traditional machine learning algorithms like Random Forest or Support Vector Machines [9]. Ref. [16] provide a comprehensive review of deep learning applications in the remote sensing domain, emphasizing its transformative role in the analysis of satellite or UAV imagery. ASM mapping is considered a Land Use Land Cover (LULC) classification task, and its mapping is normally carried out through image classification processes using satellite imagery. Ref. [7] aimed to detect ASM in Ghana using Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery; the authors employed a deep learning approach using a CNN to analyze this imagery, implementing a U-Net architecture [17]. This type of neural network architecture was designed for biomedical image segmentation and is a fully convolutional network [18]. Thanks to its encoder-decoder design it has proven to be highly effective for a number of applications within the remote sensing domain [6,19,20]. While various studies have explored ASM mapping using deep learning and remote sensing technologies, the fusion of SAR and optical data for this specific task remains unexplored territory. The combination of these two data types can offer a more detailed view of the ASM landscape. Optical data, with its spectral features, can capture a broader range of the electromagnetic spectrum beyond just the visible changes on the Earth’s surface, providing detailed information about land cover types and vegetation health. On the other hand, SAR data, with its ability to capture backscatter information, offers insights into the texture and structure of surfaces. This makes SAR suited for detecting disturbances in forested areas, as changes in texture often indicate logging or clearing activities [21]. In essence, while optical data provides the spectral information of the landscape, SAR offers its texture, and together, they can return a more complete picture of ASM activities. Another significant advantage of using SAR data is its ability to penetrate clouds, a crucial feature given the DRC’s location in the pantropical area where cloud cover is prevalent. Ref. [22] review supports the potential of such data fusion, highlighting that the combination of optical and SAR data has been beneficies for LULC classification, emphasizing the complementarity of these data sources in enhancing the accuracy for these classification tasks. In the domain of SAR-optical data fusion for deep learning applications, recent advancements have moved beyond traditional fusion techniques like pixel-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion. For instance, Ref. [23] employed both Early and Late Fusion in a CNN framework to map deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. Their study not only showcased the potential of these fusion techniques but also highlighted the differences in terms of performance between them, emphasizing the importance of selecting the right fusion strategy for specific tasks. Ref. [24] introduced an innovative approach to align the semantic distribution of optical and SAR data within a common feature space. This alignment ensures that the model effectively exploits the complementary information from both data modalities, potentially enhancing its predictive capabilities. While various fusion techniques have been explored in remote sensing, ASM mapping in the DRC presents unique challenges: spectral similarity to water bodies, prevalent cloud cover, and lack of reliable ground truth data. This study addresses these specific gaps by implementing a comparison of fusion approaches using high-resolution Planet-NICFI and Sentinel-1 data, developing a robust pseudo-ground truth methodology, and evaluating model performance across different fusion strategies.

A significant challenge in the context of ASM is the lack of ground truth data to identify the ASM areas. A recent work from [25] tried to address this problem by producing a freely accessible global mining land use dataset through remote sensing analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery. This dataset comprises different types of mining activities, including ASM. The study mapped 4058 polygons of ASM areas, totaling 1071.2 km2. However, it is noted that there is incomplete global coverage of ASM in this dataset, as some ASM areas require higher-resolution satellites and/or paid satellite services for analysis, which can be challenging to include in a global-scale study due to their dispersion. In fact, only a few polygons of this dataset are located in the DRC, therefore not representing the complex landscape of ASM in this country. The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) has provided a dataset for the DRC, pinpointing the locations of ASM sites as individual points. A significant challenge lies in transforming these point locations into polygon or raster representations of ASM areas, which is essential for training a model to map the ASM spatial extent in the country.

The primary goal of this study was to utilize deep learning for semantic segmentation of ASM sites in the DRC. A crucial step in achieving this involved the generation of a pseudo-ground truth dataset of ASM areas. This dataset supported the training and evaluation of standalone models using Planet-NICFI and Sentinel-1 data separately, alongside with models that employ data fusion to integrate these two data sources. The model with best performance was then deployed to map ASM sites across a territory of the Eastern DRC. The refined mapping capabilities developed in this study are essential for effective monitoring and management of ASM impacts in this resource-intensive region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. ASM Field Observations

Data from the IPIS on ASM sites in Eastern DRC’s former provinces (Orientale, North Kivu, South Kivu, Maniema, and Katanga) was accessed, together with the administrative boundaries sourced from GEE (Figure 1). This focus on Eastern DRC is due to the concentration of ASM sites in the region. The IPIS dataset comprises ASM locations in form of points, and it is acknowledged for its data collection based on field surveys. This study utilized key dataset features such as the date of last visit, the mining method, and whether a site has been abandoned. In the DRC, ASM involves a range of mining methods, including both alluvial and hard rock mining. Alluvial mining, which involves extracting minerals from riverbeds and other sedimentary deposits, is a common method in the DRC especially for minerals like gold. The country’s vast river networks and rich sedimentary deposits make it suited for alluvial mining. However, also other mining methods are applied for different minerals.

Figure 1.

ASM locations of the Eastern DRC present in the IPIS dataset. An example of alluvial ASM site is shown using ArcGIS (version 3.3) World Imagery basemap.

A visual review of ASM areas visible in 2023 using Planet-NICFI basemaps was conducted to assess site activity status, particularly useful for sites last visited years ago. This review, supported by the dataset’s attributes regarding abandoned sites and mining methods, allowed for the efficient filtering of sites not detectable in satellite imagery, such as those utilizing underground mining methods. It is important to note that a number of ASM points did not precisely pinpoint to the actual ASM area. This mismatch was often due to security concerns, as some locations are under the control of armed groups, making it unsafe to the survey teams. Additionally, accessibility issues related to weather conditions, particularly during the wet season (in the DRC, March to May, and from mid-September to mid-December), constrained the survey teams to reach certain sites with cars or other vehicles, and the sites were located too far for on-foot travel through the forest. These factors made necessary to exclude certain points were it was not possible to visually locate an ASM site in proximity of the point. The ASM locations identified were used to obtain the necessary satellite imagery from GEE. Bounding boxes of approximately 1.8 × 1.8 km dimensions were used in order to incorporate sites of various sizes. This approach facilitated the access to imagery from two distinct sources, Planet-NICFI and Sentinel-1, focusing on a six-month composite spanning from 1 January 2023, to 30 June 2023.

2.1.2. Planet-NICFI Imagery

The Planet-NICFI dataset is a collaborative initiative between the NICFI and Planet Labs (https://www.planet.com/nicfi/, NICFI, 1 October 2024). This dataset offers high-resolution satellite imagery, capturing multispectral data with a spatial resolution of 4.77 m. The primary objective of the Planet-NICFI program is to provide a comprehensive and timely view of tropical forests, aiming to support efforts in monitoring and mitigating deforestation and forest degradation. The Planet-NICFI dataset, with its high spatial resolution, serves as a pivotal tool for researchers, policymakers, and conservationists working towards forest conservation and sustainable land use practices. In particular, analysis-ready PlanetScope Surface Reflectance Mosaics were used. This imagery includes Blue, Green, Red and Near-Infrared (NIR) bands, thus allowing to the computation of various vegetation indices (VIs) [26]. In fact, three VIs were calculated when loading this imagery into the deep learning models. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was included because of its capability to discriminate vegetated areas from non-vegetated areas. This was considered important as the ASM sites are located within or adjacent to forested areas. The Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) was also included, as it allows to detect open water bodies and enhance their visibility in remotely sensed imagery [27]. It can be useful as a relevant number of ASM sites in the Eastern DRC are alluvial mines. For this data source, a median composite was used to reduce noise caused by clouds and shadows, yielding clearer and more consistent imagery.

2.1.3. Sentinel-1 Imagery

Sentinel-1 is a satellite mission launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) as part of the Copernicus Programme, dedicated to Earth observation and providing SAR imagery. It is particularly valuable for monitoring areas with frequent cloud cover, such as the pan-tropical regions of Earth. The data from Sentinel-1 can be used in various applications, including land and ocean monitoring, disaster management, and environmental studies. The backscatter values obtained from the SAR imagery provide insights into the roughness, moisture content, and other properties of the observed surface. Sentinel-1 images are available with a pixel size of 10 m. The framework developed by [28] was used to access and preprocess Sentinel-1 imagery. In particular, for this study Sentinel-1 Ground Range Detected (GRD) scenes were accessed. The imagery comprises two bands: VV (vertical transmit/vertical receive) and VH (vertical transmit/horizontal receive). Imagery from the descending orbit was accessed. Border noise correction and terrain flattening using the NASA SRTM Digital Elevation Model [29] were applied. For Sentinel-1, a mean composite was preferred in order to highlight structural patterns. Given that a compositing operation was applied, the usage of a speckle filter was not necessary because speckle is removed when averaging multiple images.

2.2. Pseudo-Ground Truth Dataset Generation

A critical step in this study was the transition from ASM point data to categorical (binary) raster data suitable for training deep learning models for semantic segmentation. This process involved several sequential methodological steps to ensure data quality and representativeness.

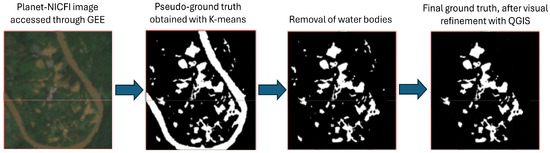

First, the K-means algorithm [30] with k = 4 was applied to Planet-NICFI imagery to obtain an initial grouping of mining sites based on their spectral characteristics. This approach facilitated the differentiation of ASM sites from surrounding features such as forests, rivers, and urban areas. However, spectral confusion remained evident in the cluster of interest, particularly between ASM sites and both water bodies and urban settlements, due to similarities in their spectral signatures. This confusion was especially pronounced for alluvial mining sites, which represent a significant portion of the study area.

To address this spectral confusion, several datasets available on Google Earth Engine (GEE) were utilized. Urban settlements and buildings were removed using the Open Buildings dataset [31] and World Settlement Footprint [32]. Water bodies were excluded using the JRC Global Surface Water Mapping Layers [33]. This masking process significantly improved the discrimination of actual ASM sites from spectrally similar land cover types.

The resulting pseudo-ground truth was exported as binary raster imagery from GEE, with pixels assigned a value of 1 for ASM areas and 0 for other LULC classes. Subsequent manual refinement using QGIS further enhanced dataset quality. This refinement stage was particularly important because many ASM sites identified by point data were situated in close proximity, leading to overlapping images. These overlapping images were systematically removed, as well as scenes lacking visible ASM sites. Additionally, images containing excessively cluttered ASM sites were identified and excluded, as their manual correction was impractical due to the significant time required for detailed adjustments. This selective exclusion process ensured that only clear, accurately represented sites were retained, thereby increasing the overall quality of the pseudo-ground truth dataset. The manual refinement process was critical for ensuring the semantic quality of the dataset, particularly in distinguishing ASM sites from other land covers that expose bare soil, such as agricultural clearing. This distinction was made possible by the high spatial resolution of the Planet-NICFI imagery (4.77 m), which allows for the identification of features unique to artisanal mining that are often not resolvable in medium-resolution data. We adopted visual interpretation criteria consistent with Slagter et al. [34] to differentiate these drivers. Specifically, ASM sites were identified by the presence of bright bare soil often accompanied by water ponds (typical of alluvial mining), irregular excavation patterns, and piles of tailings. In contrast, agricultural clearings were identified by their more regular geometric shapes, smoother texture, and lack of the heterogeneous surface roughness created by mining pits. Scenes where this distinction remained ambiguous even at high resolution were excluded from the dataset to prevent label noise.

As expected, the resulting dataset exhibited considerable class imbalance, with non-ASM pixels (class 0) substantially outnumbering ASM pixels (class 1). This imbalance was subsequently addressed during model training through appropriate loss functions. Figure 2 illustrates the progression from raw Planet-NICFI imagery to the final pseudo-ground truth, demonstrating the effectiveness of the multi-stage refinement approach.

Figure 2.

The steps from Planet-NICFI image to the final pseudo-ground truth raster.

2.3. Deep Learning for ASM Segmentation

2.3.1. Neural Network Architecture

In this study, the U-Net architecture was used. It is distinguished for its “U-shaped” structure, with a contracting (downsampling) path connected to an expansive (upsampling) path by concatenating feature maps. In particular, Residual Attention U-Net was applied [35,36,37], combining the strengths of residual connections and attention mechanisms. The model was implemented using the Segmentation Models library [38], which offers a high level API to define a neural network and choose among different encoders. Given the modest size of the used dataset (outlined in Section 3.1), pretrained weights from the ImageNet dataset were leveraged. The chosen setup for this project included the ResNet encoder [39], enhanced with spatial and channel Squeeze & Excitation (scSE) attention [40,41]. This attention mechanism enriches the model’s ability to focus on relevant spatial and channel-wise information, improving segmentation accuracy by distinguishing between areas of interest and background noise in the images. Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam, [42]) was the selected optimizer for the models. Focal loss was the selected criterion, useful to address class imbalance by decreasing the relative loss for well-classified examples, putting more focus on hard, misclassified examples [43]. It introduces a modulating factor to the standard cross-entropy loss, with the focusing parameter steering the effect of the modulation. Larger reduces the loss contribution from easy examples, allowing the model to focus training on hard negatives. It is given by:

where is the model’s estimated probability for the class with label , is the prior probability of having positive value in target, and is a tunable focusing parameter. Two regularization techniques were applied during the models’ training: batch normalization [44] and weight decay [45]. All the band data were normalized during model training, testing and inference. For both Planet-NICFI and Sentinel-1 imagery, band-specific normalization was applied using a percentile-based approach, scaling pixel values between the 2nd and 98th percentiles of the global distribution for each band. This method effectively mitigates the influence of outliers that could otherwise distort the feature distribution and negatively impact model training. The normalized values were linearly rescaled to the range [0, 1], creating a standardized input space for the neural network. A classification threshold of 0.5 was applied to convert the probability outputs from the sigmoid activation function to binary predictions (0 for non-ASM, 1 for ASM).

2.3.2. Dataset Split

To ensure spatial independence and avoid spatial autocorrelation [46], spatial splits were created. The study area was divided into a regular grid of spatial blocks, and each image tile was assigned to its corresponding block based on geographic location. An iterative optimization approach was used to allocate blocks between training and testing sets while maintaining approximately 70% of tiles for training and 30% for testing (Figure 3). This approach ensures both spatial separation and consistent ratios. To make the methodology more robust and minimize the effects of any particular spatial configuration, five different spatial splits were created with varying block allocations, and each model was trained and tested on all five splits to assess performance consistency.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the spatial splits approach used to organize the datasets in training and testing sets. (a) shows the spatial distribution of the training data, and (b) shows the spatially independent test data. The blue and green points represent the ASM point locations.

2.3.3. Model Configurations, Optimization, Training and Testing

This study implemented four model configurations: two standalone models using individual data sources (Planet-NICFI and Sentinel-1), and two data fusion approaches integrating both datasets. The fusion methods explored were Late Fusion and Early Fusion. The Late Fusion approach employs separate encoders for each data stream, allowing each modality (optical and SAR) to extract features independently. This ensures the unique characteristics of each data source are effectively captured before integration. Following extraction, features from both streams are combined using one of three integration methods: concatenation, summation, or weighted averaging [47].

The Late Fusion approach leverages modality-specific features before integration, allowing complementary information from optical and SAR data to enhance overall segmentation performance. To balance the contributions from each modality, learnable fusion weights were implemented that dynamically adjust during training. Conversely, the Early Fusion method combines the input data at the initial stage, generating a unified input before any processing occurs. This approach concatenates images from different data sources along the channel dimension, resulting in a single composite input that is fed into a single-encoder network. The model applies a channel attention mechanism that dynamically weights the contribution of each input band, allowing it to focus on the most relevant features from each data source.

Given the discrepancy in pixel size of the two data sources (4.77 m for Planet-NICFI, 10 m for Sentinel-1), the resampling strategy was included as a hyperparameter in the optimization process. Two strategies were evaluated: upsampling Sentinel-1 to match Planet-NICFI resolution using cubic interpolation, and downsampling Planet-NICFI to match Sentinel-1 resolution using area-based resampling.

Each model setup underwent hyperparameter optimization using Bayesian optimization with the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) sampler [48,49]. This approach efficiently samples the hyperparameter space by estimating probability distributions based on previous trial results. The optimization was configured to maximize the F1-score on the ASM class in the validation set, with 50 trials conducted for each model configuration. Different hyperparameters were optimized depending on the model type, with fusion-specific parameters only applicable to Late Fusion and Early Fusion models. Table 1 presents the hyperparameter search space explored during optimization.

Table 1.

Hyperparameters optimized for each model configuration.

The best hyperparameter configuration for each model setup was selected and trained/tested over five spatial splits. Performance was assessed using Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Overall Accuracy (OA). These metrics are calculated based on pixel-level classifications, where True Positives () represent correctly classified ASM pixels, False Positives () are non-ASM pixels incorrectly classified as ASM, True Negatives () are correctly identified non-ASM pixels, and False Negatives () are ASM pixels missed by the model. The metrics are defined as follows:

Precision indicates the reliability of the model’s positive predictions, Recall measures its ability to detect all relevant instances, and the F1-score provides the harmonic mean of the two, serving as a critical metric for imbalanced datasets.

2.4. Model Application and Map Accuracy Assessment

The best-performing model was used to generate a map of ASM sites in the Mwenga territory, located in South Kivu Province, DRC. Mwenga is a region heavily affected by artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) activities [50]. The rapid expansion of ASM and semi-industrial mining operations has intensified conflicts and violence, driven by disputes over land rights [51] and by increasing environmental degradation [50].

To evaluate the accuracy of the generated ASM map, an accuracy assessment was conducted using stratified random sampling [21,52]. Three strata comprising a total of 500 sample points were defined. Specifically, 200 points were assigned to the ASM stratum to estimate commission error, and 200 points were allocated to the buffer zone around ASM locations and rivers, representing areas with a higher likelihood of additional ASM sites, to estimate omission error. A buffer distance of 500 m was applied. The remaining 100 points were assigned to the No ASM stratum. The sampling unit corresponded to a single pixel. Since the strata did not directly correspond to the map classes, accuracy estimation followed the methodology described by [53].

Validation of the sampled locations was conducted using very high-resolution imagery available through Google Earth, with the most recent data for the area of interest dating from June and July 2023. This independent, higher-resolution reference source was selected in line with best practices for map accuracy assessment as recommended by [52]. Using a reference dataset distinct from that employed for model training and inference was essential to ensure a robust and unbiased evaluation of the map’s accuracy.

Unequal inclusion probabilities were considered in the accuracy assessment, as the different strata varied in areal extent and the sample points were not allocated proportionally to their areas [54]. The calculation of inclusion probabilities allowed for the derivation of estimation weights, which were used to construct a weighted confusion matrix. This facilitated the computation of overall accuracy, user’s accuracy (UA), and producer’s accuracy (PA), providing a comprehensive evaluation of the ASM map. All analyses were carried out using QGIS (version 3.36) and the R package https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mapaccuracy/index.html, mapaccuracy, accessed on 1 March 2024.

3. Results

3.1. ASM Pseudo-Ground Truth Dataset

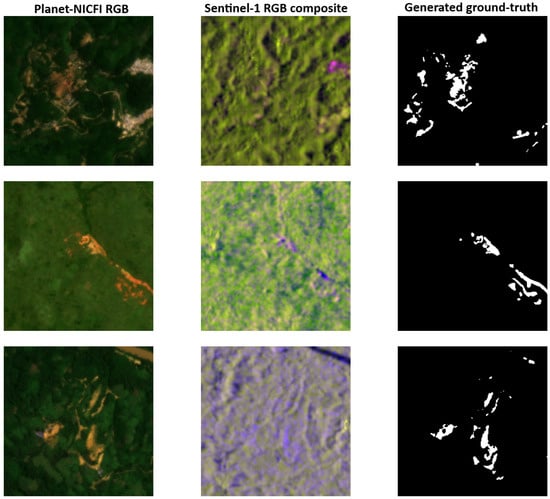

In this study, a pseudo-ground truth dataset comprising 782 tiles was obtained (Figure 4). Each tile include a set of three images: a Planet-NICFI image (256 × 256 px), a Sentinel-1 image (128 × 128 px) and a correspoding ground truth image.

Figure 4.

Examples the tiles obtained during the pseudo-ground truth dataset generation process. Sentinel-1 RGB composite was obtained using the VV, VH and VV/VH bands.

3.2. Models’ Accuracy Assessment

This section presents the comparative performance of the four model configuration: Planet-NICFI standalone, Sentinel-1 standalone, Late Fusion and Early Fusion. Table 2 shows the optimal hyperparamater configurations for each model setup following Bayesian optimization.

Table 2.

Best hyperparameter configurations for each model setup.

Performance metrics for each model configuration, evaluated in five spatial splits, are summarized in Table 3. The Late Fusion model achieved the highest precision (0.741 ± 0.045), recall (0.744 ± 0.049), and F1 score (0.736 ± 0.019) for the ASM class. The Planet-NICFI standalone model produced an ASM class F1 score of 0.716 ± 0.019, while the Early Fusion approach yielded 0.685 ± 0.038. The Sentinel-1 standalone model recorded the lowest performance with an ASM class F1 score of 0.424 ± 0.015.

Table 3.

Performance metrics (average and standard deviation calculated over the 5 different spatial splits) for each model configuration—Planet-NICFI standalone, Sentinel-1 standalone, Early Fusion and Late Fusion.

Figure 5 illustrates example predictions from all four models across three representative test sites. In Example 1, the Late Fusion model distinguished ASM sites from urban areas, which were classified as ASM by the Planet-NICFI standalone model. The Sentinel-1 model detected fewer ASM sites in this example. Examples 2 and 3 demonstrate the models’ performance in avoiding segmentation of rivers as ASM, which occurred in both the Planet standalone model and Early Fusion model. The Late Fusion approach combined the spectral information from Planet-NICFI with the textural information from Sentinel-1, resulting in reduced misclassification of rivers and built-up areas as ASM sites.

Figure 5.

Segmentation examples of the implemented models. The input satellite images and related ground truth are displayed together with the corresponding model predictions. Sentinel-1 tiles are shown as RGB composite of the bands VV-VH-VV/VH ratio. ‘ASM’ class is represented in white, ‘Other’ class in black.

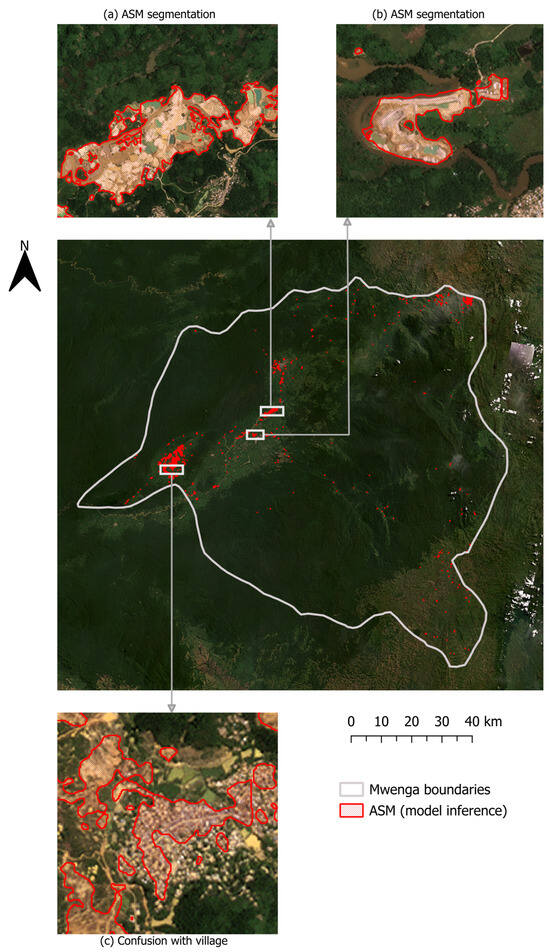

3.3. ASM Sites Map

The ASM map generated over the Mwenga territory is shown in Figure 6. The confusion matrix (Table 4) shows 298 true positives for the Non-ASM class, and 144 true positives for the ASM class. However, the model also misclassified 57 non-ASM areas as ASM. By a visual review of the ASM segmentation, it was observed that the major land use causing confusion to the model was represented by built-up areas. An example can be observed in inset (c) of Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The ASM map resulting from the application of the Late Fusion model on the Mwenga territory. Planet-NICFI Global Quarterly (April 2023–June 2023) product is used as basemap.

Table 4.

Confusion matrix resulting from the sampling for the map accuracy assessment.

Map accuracy assessment results are shown in Table 5. The map achieved an overall accuracy of 88.4%, indicating a high level of accuracy across all classifications. User’s accuracy for Non-ASM was very high at 99.7%; however, User’s Accuracy (UA) for ASM was lower at 71.6%. Producer’s Accuracy (PA) for Non-ASM was at 83.0%, and for ASM at 99.3%.

Table 5.

Map accuracy metrics.

4. Discussion

4.1. Deep Learning for ASM Mapping

This study demonstrates the efficacy of deep learning approaches for mapping ASM sites in the DRC using high-resolution satellite imagery. The implementation of Residual Attention U-Net with spatial and channel Squeeze & Excitation attention mechanisms proved effective in segmenting ASM areas while differentiating them from spectrally similar landscapes. The success of this architecture aligns with findings from other studies utilizing attention-based models for remote sensing applications [10,35], confirming the value of attention mechanisms in focusing on relevant spatial and spectral features.

Our model’s performance metrics (precision of 74.1%, recall of 74.4%, and F1-score of 73.6% for the Late Fusion model) compare favorably with previous studies on ASM mapping. These results exceed those reported by [10], who achieved precision of 69%, recall of 61%, and F1-score of 65% using an ADSMS U-Net architecture with Sentinel-2 data. This improvement can be attributed to two key factors: the higher spatial resolution of Planet-NICFI imagery (4.77 m versus 10 m for Sentinel-2) and the integration of complementary SAR data through fusion approaches.

4.2. Data Fusion Benefits and Challenges

The comparison of standalone models versus fusion approaches revealed insights into the complementary nature of optical and SAR data for ASM mapping. The Late Fusion model consistently outperformed both standalone models across all metrics, demonstrating that the integration of spectral information from optical imagery with information from SAR data gives a more robust representation of ASM sites.

A key finding was the Late Fusion model’s improved ability to distinguish ASM sites from water bodies and built-up areas, a persistent challenge in standalone optical-based approaches. Rivers and ASM sites often show similar spectral characteristics in optical imagery, particularly for alluvial mining operations, which frequently occur alongside or within water bodies. The SAR data’s unique backscatter properties provided critical discriminative information by capturing distinct scattering mechanisms. While water bodies act as specular reflectors, appearing as dark pixels with low backscatter, ASM sites exhibit higher, more variable backscatter patterns due to the surface roughness of exposed soil and tailings. Furthermore, the model leverages the volume scattering of forests (particularly in VH) and the double-bounce scattering of built-up areas to further differentiate these classes from mining sites. This effectiveness of SAR-optical fusion for distinguishing between spectrally similar classes with different structural properties confirms the observations by [22] and offers a novel solution to the specific challenges noted by [7].

The better performance of Late Fusion over Early Fusion aligns with findings in deep learning-based land cover mapping, such as those by Maretto et al. [23]. Optical imagery and SAR data represent different physical properties: the former captures spectral reflectance related to surface chemistry, while the latter captures structural geometry and dielectric properties. Early Fusion forces the network to learn joint representations from these disparate statistical distributions immediately at the input level, which can be inefficient when noise patterns (e.g., SAR speckle vs. cloud-free optical pixels) are uncorrelated. In contrast, the Late Fusion architecture allows separate encoders to learn high-level abstractions for each specific modality, such as the texture of mining pits in SAR and the spectral signature of bare soil in optical, before merging them. This preserves the unique characteristics of each source and allows the network to compare the high-level semantic features of one modality against the other.

4.3. Pseudo-Ground Truth Generation

The generation of a reliable pseudo-ground truth dataset represented a crucial step in this study. The conversion of point-based ASM locations to segmented areas through a multi-stage process involving K-means clustering, auxiliary dataset masking, and manual refinement addressed a significant gap in available training data for ASM mapping in the DRC.

This approach aligns with emerging methodologies for semi-automated dataset creation in remote sensing applications [55,56], and represents a practical solution to the challenge of limited labeled data in regions where field validation is difficult due to accessibility, security concerns, or resource constraints. However, this methodology introduces potential biases and inaccuracies that may propagate to the trained models. The reliance on spectral clustering to identify candidate ASM areas may miss sites with atypical signatures or incorrectly include spectrally similar non-ASM areas.

Despite these limitations, our approach demonstrates a viable pathway for developing training datasets in data-scarce environments. The performance of models trained on this pseudo-ground truth dataset, as evidenced by both the testing metrics and the map accuracy assessment, validates the efficacy of our methodology. Future work could enhance this process through more sophisticated annotation techniques, additional auxiliary datasets, or limited but targeted ground validation where feasible.

4.4. Practical Application and Map Accuracy

The application of the Late Fusion model to map ASM sites across the Mwenga territory demonstrated the practical utility of our approach. The overall map accuracy of 88.4% indicates good reliability, though the lower User’s Accuracy for ASM (71.6%) compared to the very high Producer’s Accuracy (99.3%) reveals some classification errors.

The higher commission error (classifying non-ASM as ASM) versus omission error (missing actual ASM sites) suggests the model tends toward over-detection rather than under-detection of mining sites. While this presents challenges for precise area estimation, it aligns with a precautionary approach for environmental monitoring, where detecting potential mining activities, even with some false positives, may be preferable to missing actual sites.

The persistent confusion between ASM sites and built-up areas, evident in our map validation, represents a limitation not fully addressed by our fusion approach. This confusion likely stems from the similar textural patterns and bright signatures that both built-up areas and bare soil in mining sites exhibit in both optical and SAR imagery. This challenge was previously noted by [7], who addressed it by including built-up areas as a separate class in their classification scheme. Their approach suggests a potential pathway for improving our model by expanding from binary segmentation to multi-class segmentation.

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

While our study demonstrates attempts to advance ASM mapping, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the pseudo-ground truth generation methodology, though practical, introduces uncertainties that could affect model accuracy. Future work could enhance this process through more sophisticated annotation techniques or limited but targeted ground validation. A limitation regarding the dataset generation was the inability to perform a quantitative validation (e.g., IoU or Kappa coefficient) of the pseudo-ground truth masks themselves. This was due to the absence of a polygon dataset for ASM in the DRC. The available IPIS dataset consists of point locations which, as previously mentioned, often suffer from spatial offsets due to security and accessibility constraints during field data collection. Calculating overlap metrics against these imprecise point locations would yield misleading results; therefore, the quality of the pseudo-ground truth is indirectly reflected by the model’s final performance against independent high-resolution validation imagery.

Second, the persistent confusion between ASM sites and built-up areas highlights a limitation in our current approach. As suggested by [7], expanding to a multi-class segmentation framework that explicitly includes built-up areas could potentially address this challenge. This confusion likely comes from the similar textural patterns and bright signatures that both built-up areas and mining sites show in optical and SAR imagery. Addressing this will likely require moving beyond binary classification, explicitly training the model to recognize ’built-up’ as a distinct semantic class would force the network to learn the subtle feature differences between urban structures and mining activities, rather than treating them both as generic foreground or background.

Also, the reliance on proprietary Planet-NICFI imagery, while beneficial for accuracy due to its high spatial resolution, may limit the widespread application of our methodology in resource-constrained settings. Exploring alternative approaches using freely available imagery, such as Sentinel-2 combined with Sentinel-1, presents an important direction for future research.

Additionally, the current study focuses on detecting ASM presence without distinguishing between different types of mining operations or minerals being extracted. The IPIS dataset contains information about mineral types at various locations, which could potentially be leveraged to develop more specialized models that not only detect ASM sites but also classify them by mineral type or mining method.

Another limitation is that the model’s generalization capability to other geographic regions or distinct temporal periods was not validated in this study. While our spatial split methodology ensures robustness within the diverse landscapes of the Eastern DRC, testing transferability to entirely new areas is currently constrained by the lack of high-quality, spatially detailed ground truth data for ASM. Future research efforts should focus on the collection and generation of such datasets to evaluate and improve the model’s applicability on a broader scale.

Finally, exploring the integration of short-wave infrared (SWIR) bands, available in sensors like Sentinel-2 but not in Planet-NICFI, represents another promising direction. Previous research has highlighted the value of SWIR bands for distinguishing mining areas from other land cover types due to their sensitivity to soil mineral composition [7]. Super-resolution techniques to enhance Sentinel-2 resolution [57,58] or novel fusion approaches incorporating SWIR bands from Sentinel-2 with high-resolution RGB-NIR from Planet could potentially address this limitation.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a novel approach to mapping Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) in the Democratic Republic of Congo using high-resolution satellite imagery and deep learning. Several key achievements and insights emerged from this research. First, we developed a methodology for generating reliable pseudo-ground truth data by converting point-based ASM locations to segmented areas through a multi-stage process. This approach addresses a critical gap in available training data for ASM mapping and offers a viable solution for regions where field validation is challenging due to accessibility, security concerns, or resource constraints. Second, we demonstrated the effectiveness of deep learning, specifically the Residual Attention U-Net architecture with spatial and channel Squeeze & Excitation attention mechanisms, for accurately segmenting ASM sites in satellite imagery. This confirms the value of attention-based neural networks in capturing the complex spatial and spectral characteristics of mining areas within their surrounding landscapes. Third, we established that the fusion of optical and SAR data significantly enhances ASM detection capabilities compared to using either data source alone. Specifically, the Late Fusion approach achieved the highest performance (F1-score of 73.6%), outperforming both standalone models and the Early Fusion approach. The optimal solution identified in this study consists of a Late Fusion deep learning architecture utilizing a ResNet34 encoder, which integrates upsampled Sentinel-1 SAR data (capturing textural features) with high-resolution Planet-NICFI optical imagery (capturing spectral features) to maximize the segmentation accuracy of artisanal mining sites. This finding underscores the complementary nature of these data sources: optical imagery provides rich spectral information about land cover types, while SAR data offers textural information and all-weather capabilities that help distinguish ASM sites from spectrally similar features such as water bodies and built-up areas. Then, we successfully applied our best-performing model to produce an ASM map of the Mwenga territory with high overall accuracy (88.4%), demonstrating the practical utility of our approach for real-world environmental monitoring applications. The map revealed patterns of ASM activity across the region, providing valuable spatial information that can support more targeted interventions and policy decisions.

Despite these achievements, challenges remain, particularly regarding the confusion between ASM sites and built-up areas, which contributed to a lower User’s Accuracy for the ASM class (71.6%). This limitation points to opportunities for further methodological refinements, such as expanding to multi-class segmentation frameworks or incorporating additional spectral bands.

The methodology and findings from this study contribute to the growing body of research on remote sensing applications for monitoring mining activities in conflict-affected regions. By enabling more accurate and efficient mapping of ASM sites, this approach can support better-informed decision-making for addressing the environmental, social, and economic challenges associated with artisanal mining in the DRC and similar contexts globally. Future research should focus on addressing the identified limitations and exploring the potential for transferability of this approach to other regions, integration of additional data sources such as SWIR bands, and extension to multi-class approaches that could distinguish between different types of mining operations or minerals being extracted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, F.P.; software, F.P.; validation, F.P.; formal analysis, F.P.; investigation, F.P.; resources, R.N.M. and J.R.; data curation, F.P. and R.N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P.; writing—review and editing, R.N.M. and J.R.; visualization, F.P.; supervision, R.N.M. and J.R.; funding acquisition, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project received from the Open Domain Science project Forest Carbon Crime (Project Number: OCENW.M.21.203) of the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO).

Data Availability Statement

All the code used to perform this study is freely available on https://github.com/96francesco/asm-mapping, GitHub, accessed on 10 October 2025.

Acknowledgments

We thank the three anonyms reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maystadt, J.F.; De Luca, G.; Sekeris, P.G.; Ulimwengu, J. Mineral resources and conflicts in DRC: A case of ecological fallacy? Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2014, 66, 721–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geenen, S. A dangerous bet: The challenges of formalizing artisanal mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otamonga, J.P.; Poté, J.W. Abandoned mines and artisanal and small-scale mining in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Survey and agenda for future research. J. Geochem. Explor. 2020, 208, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; McQuilken, J. Four decades of support for artisanal and small-scale mining in sub-Saharan Africa: A critical review. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2014, 1, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.; Veiga, M.M. Artisanal and small-scale mining as an extralegal economy: De Soto and the redefinition of “formalization”. Resour. Policy 2009, 34, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masolele, R.N.; De Sy, V.; Marcos, D.; Verbesselt, J.; Gieseke, F.; Mulatu, K.A.; Moges, Y.; Sebrala, H.; Martius, C.; Herold, M. Using high-resolution imagery and deep learning to classify land-use following deforestation: A case study in Ethiopia. GISci. Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1446–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallwey, J.; Robiati, C.; Coggan, J.; Vogt, D.; Eyre, M. A Sentinel-2 based multispectral convolutional neural network for detecting artisanal small-scale mining in Ghana: Applying deep learning to shallow mining. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 248, 111970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamekye, C.; Ghansah, B.; Agyapong, E.; Obuobie, E.; Awuah, A.; Kwofie, S. Examining the performances of true color RGB bands from Landsat-8, Sentinel-2 and UAV as stand-alone data for mapping artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM). Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 24, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamekye, C.; Ghansah, B.; Agyapong, E.; Kwofie, S. Mapping changes in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) landscape using machine and deep learning algorithms. - a proxy evaluation of the 2017 ban on ASM in Ghana. Environ. Chall. 2021, 3, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, L.; Cuevas, M.; Meena, S.R.; Catani, F.; Monserrat, O. Artisanal and Small-Scale Mine Detection in Semi-Desertic Areas by Improved U-Net. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 2507905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecun, Y.; Bengio, Y. Convolutional Networks for Images, Speech, and Time-Series. In The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Preetham, A.; Vyas, S.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, S.N.P. Optimized convolutional neural network for land cover classification via improved lion algorithm. Trans. GIS 2024, 28, 769–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarakati, H.M.; Khan, M.A.; Hamza, A.; Khan, F.; Kraiem, N.; Jamel, L.; Almuqren, L.; Alroobaea, R. A Novel Deep Learning Architecture for Agriculture Land Cover and Land Use Classification from Remote Sensing Images Based on Network-Level Fusion of Self-Attention Architecture. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 6338–6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Multiscale Fusion CNN-Transformer Network for High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image Change Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 5280–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhu, K.; Peng, D.; Tang, H.; Yang, K.; Bruzzone, L. Adapting Segment Anything Model for Change Detection in VHR Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5611711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.X.; Tuia, D.; Mou, L.; Xia, G.S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Fraundorfer, F. Deep Learning in Remote Sensing: A Comprehensive Review and List of Resources. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelhamer, E.; Long, J.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, H. End-to-End Change Detection for High Resolution Satellite Images Using Improved UNet++. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yuan, Y.; Song, M.; Ding, Y.; Lin, F.; Liang, D.; Zhang, D. Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery and Deep Learning UNet to Extract Rice Lodging. Sensors 2019, 19, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, J.; Mullissa, A.; Slagter, B.; Gou, Y.; Tsendbazar, N.E.; Odongo-Braun, C.; Vollrath, A.; Weisse, M.J.; Stolle, F.; Pickens, A.; et al. Forest disturbance alerts for the Congo Basin using Sentinel-1. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 024005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Baumann, M.; Ehammer, A.; Fensholt, R.; Grogan, K.; Hostert, P.; Jepsen, M.R.; Kuemmerle, T.; Meyfroidt, P.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; et al. A Review of the Application of Optical and Radar Remote Sensing Data Fusion to Land Use Mapping and Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maretto, R.V.; Fonseca, L.M.G.; Jacobs, N.; Körting, T.S.; Bendini, H.N.; Parente, L.L. Spatio-Temporal Deep Learning Approach to Map Deforestation in Amazon Rainforest. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sun, K.; Li, W.; Wei, J.; Miao, S.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Q. Aligning semantic distribution in fusing optical and SAR images for land use classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 199, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Werner, T.T. Global mining footprint mapped from high-resolution satellite imagery. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, e1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFEETERS, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullissa, A.; Vollrath, A.; Odongo-Braun, C.; Slagter, B.; Balling, J.; Gou, Y.; Gorelick, N.; Reiche, J. Sentinel-1 SAR Backscatter Analysis Ready Data Preparation in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; et al. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, RG2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume 1: Statistics; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 5.1, pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Sirko, W.; Kashubin, S.; Ritter, M.; Annkah, A.; Bouchareb, Y.S.E.; Dauphin, Y.; Keysers, D.; Neumann, M.; Cisse, M.; Quinn, J. Continental-Scale Building Detection from High Resolution Satellite Imagery. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.12283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconcini, M.; Metz-Marconcini, A.; Üreyen, S.; Palacios-Lopez, D.; Hanke, W.; Bachofer, F.; Zeidler, J.; Esch, T.; Gorelick, N.; Kakarla, A.; et al. Outlining where humans live, the World Settlement Footprint 2015. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekel, J.F.; Cottam, A.; Gorelick, N.; Belward, A.S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 2016, 540, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagter, B.; Reiche, J.; Marcos, D.; Mullissa, A.; Lossou, E.; Peña-Claros, M.; Herold, M. Monitoring direct drivers of small-scale tropical forest disturbance in near real-time with Sentinel-1 and -2 data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, D.; Sigedar, P.; Singh, M. Attention Res-UNet with Guided Decoder for semantic segmentation of brain tumors. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 71, 103077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Liu, X.; Shahzad, R.; Reimer, R.; Thiele, F.; Zhang, H. Advanced Deep Learning Approach to Automatically Segment Malignant Tumors and Ablation Zone in the Liver With Contrast-Enhanced CT. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 669437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.L.; Bian, G.B.; Zhou, X.H.; Hou, Z.G.; Xie, X.L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.J.; Li, R.Q.; Li, Z. RAUNet: Residual Attention U-Net for Semantic Segmentation of Cataract Surgical Instruments. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.10360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakubovskii, P. Segmentation Models Pytorch. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/qubvel/segmentation_models.pytorch (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.G.; Navab, N.; Wachinger, C. Recalibrating Fully Convolutional Networks with Spatial and Channel ‘Squeeze & Excitation’ Blocks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.08127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1709.01507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1708.02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1502.03167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P. Spatial Autocorrelation: Trouble or New Paradigm? Ecology 1993, 74, 1659–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzicki, K.; Khamsehashari, R.; Zetzsche, C. Early vs Late Fusion in Multimodal Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Rustenburg, South Africa, 6–9 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; Kégl, B. Algorithms for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki, Y.; Tanigaki, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Nomura, M.; Onishi, M. Multiobjective Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2022, 73, 1209–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasso, D.S.; Kassam, D.; Kwakanaba, A.M.; Kamani, S.T.; Ahanyirwe, E.T.; Masumbuko, C.B.; Basengere, R.B.A. Unraveling Fishers’ Perceptions: Mining’s Impact on Fish Yield and Diversity in Mwenga, South Kivu, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo; Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo: South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladewig, M.; Cuni-Sanchez, A.; Angelsen, A.; Imani, G.; Baderha, G.K.; Bulonvu, F.; Kalume, J. Between a rock and a hard place: Livelihood diversification through artisanal mining in the Eastern DR Congo. Resour. Policy 2025, 106, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E.; Wulder, M.A. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehman, S.V. Estimating area and map accuracy for stratified random sampling when the strata are different from the map classes. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 4923–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehman, S.V.; Wickham, J.D.; Smith, J.H.; Yang, L. Thematic accuracy of the 1992 National Land-Cover Data for the eastern United States: Statistical methodology and regional results. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.S.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, C.; Zhang, L. Accurate Annotation of Remote Sensing Images via Active Spectral Clustering with Little Expert Knowledge. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 15014–15045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippa, T.; Lennert, M.; Beaumont, B.; Vanhuysse, S.; Stephenne, N.; Wolff, E. An Open-Source Semi-Automated Processing Chain for Urban Object-Based Classification. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaras, C.; Bioucas-Dias, J.; Galliani, S.; Baltsavias, E.; Schindler, K. Super-resolution of Sentinel-2 images: Learning a globally applicable deep neural network. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 146, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro Romero, L.; Marcello, J.; Vilaplana, V. Super-Resolution of Sentinel-2 Imagery Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).