Highlights

What are the main findings?

- High-resolution hyperspectral satellite data (EMIT and Tanager-1) reveal strong spatial contrasts in landfill CH4 emissions across north-central Brazil, with most sites showing modest plume strengths (106–107 ppm·m3) and a few reaching super-emitter levels (>108 ppm·m3).

- Only three super-emitter events—two at Brasília and one at Marituba—dominated the regional CH4 budget, confirming a heavy-tailed, log-normal distribution of emissions.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Targeted mitigation at a handful of persistent high-emitting landfills could yield rapid, cost-effective CH4 reductions, substantially contributing to Brazil’s climate commitments under the Paris Agreement and Global Methane Pledge.

- This study demonstrates the capability of next-generation hyperspectral satellites to identify, quantify, and monitor CH4 super-emitters in data-scarce regions, strengthening the role of remote sensing in waste-sector and other facilities’ greenhouse gas management.

Abstract

Methane (CH4) is a potent greenhouse gas and a key target for near-term climate mitigation, yet major uncertainties remain in quantifying emissions from landfills, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions of the Global South. Here, we present a systematic satellite-based assessment of CH4 emissions from landfills and related sites across northern and central Brazil, based on plume detections from the Carbon Mapper public data portal. Using imaging spectroscopy data from the Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT) onboard the International Space Station and the dedicated Tanager-1 satellite, we analyzed 40 plume detections across 16 sites in nine Brazilian states spanning the Amazon forest biome and the Cerrado transition region. An adaptive thresholding algorithm was applied to each detection to quantify plume strength (ppm·m3), areal extent, and recurrence across multiple overpasses. Our results reveal a strongly heavy-tailed distribution of emissions, with most sites exhibiting modest plume strengths in the 106–107 ppm·m3 range, while a small number of facilities dominated the upper tail. Two detections at Brasília (2.22 × 108 and 2.14 × 108 ppm·m3) and one at Marituba (1.66 × 108 ppm·m3) were classified as super-emitters, exceeding all other sites by more than an order of magnitude. These facilities also demonstrated high persistence across overpasses, in contrast to smaller landfills such as Macapá and Boa Vista, where emissions were weaker (<107 ppm·m3) and episodic. Regional contrasts were also evident: sites in the Cerrado transition zone, (e.g., Brasília, Campo Grande) generally showed stronger and more frequent emissions than those in the Amazon basin. These findings underscore the disproportionate role of a few persistent super-emitters in shaping the regional CH4 budget. Targeted mitigation at these high-impact sites could yield rapid and cost-effective emission reductions, directly supporting Brazil’s commitments under the Paris Agreement and the Global CH4 Pledge. More broadly, this study demonstrates the power of high-resolution satellite imaging spectroscopy for identifying, monitoring, and prioritizing CH4 mitigation opportunities in the waste sector.

Keywords:

CH4 hyperspectral satellite observations; Carbon Mapper; EMIT; Tanager-1; Brazil; Amazon; Cerrado 1. Introduction

Methane (CH4) is the second most important anthropogenic greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide (CO2), a powerful climate warmer that accounts for approximately 20% of the increase in global radiative forcing since pre-industrial times [1,2,3]. Despite its shorter atmospheric lifetime of approximately 12 years, CH4 exhibits a global warming potential 28 times greater than that of CO2 over a 100-year horizon and 84 times greater over a 20-year horizon [4]. CH4 anthropogenic emissions arise from multiple sectors, comprising livestock, oil and gas operations, coal mining, landfills, wastewater treatment, and rice cultivation, while wetlands represent the largest natural source. Rapid reductions in CH4 emissions are therefore widely recognized as one of the most effective strategies to slow near-term climate warming [5,6,7]. In addition to its role in climate change, CH4 is also a precursor to tropospheric ozone, contributing to poor air quality and adverse health outcomes [2,8,9]. Globally, the solid waste sector, including landfills and open dumps, represents a significant yet poorly characterized source of CH4. Worldwide, CH4 emissions from solid waste and wastewater contribute roughly 18% of anthropogenic sources, and projections indicate that emissions from the solid waste sector could double by 2050, although considerable uncertainties remain [10]. It was shown that global bottom-up landfill CH4 inventories can underestimate emissions by up to 200%, but this discrepancy can be reduced by incorporating waste- and environment-specific factors [11]. Anaerobic decomposition of organic waste generates landfill gas, that is rich in CH4, which in the absence of effective capture systems, escapes into the atmosphere [12,13]. Landfills, engineered sites where solid waste is buried and decomposes under oxygen-limited conditions, are a growing CH4 source with poor management, amplifying emissions, while gas recovery and ‘zero-landfill’ strategies offer mitigation potential [14,15]. Consequently, substantial uncertainties remain in quantifying CH4 emissions from landfills and waste management activities. Previous studies demonstrate that landfills are major but underestimated CH4 sources. Measurements at the Olinda Alpha Landfill indicate 11.6–17.8 kt CH4 yr−1, showing discrepancies with US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) inventory estimates [16]. Airborne and satellite surveys reveal large emission variability among solid waste facilities, emphasizing the need for improved detection and mitigation [17]. In California, a few super-emitter landfills account for 41% of CH4 emissions, while only 0.2% of infrastructure drives most emissions [18]. The solid waste sector remains underestimated, and studies urge use of updated emission factors and remote sensing data to refine inventories [19]. High-resolution satellite analyses show ~481 kg CH4 h−1 from 60 North American landfills, with gas capture efficiencies often overestimated [20]. Airborne surveys of 217 U.S. sites reveal active tipping areas contribute ~79% of emissions revealing inventories underestimation [21]. Airborne imaging of U.S. landfills detected CH4 at ~52% of sites, with emissions ~1.4× higher than inventory estimates [22]. At a managed Paris landfill, mean emissions reached ~2.1 t CH4 d−1, concentrated at active zones [23]. Satellite studies also show Indian landfills emit more urban CH4 than those in China or the U.S., highlighting regional management differences and systematic underestimations in IPCC defaults [24]. Comparative assessments between the U.S. and China confirm large uncertainties in waste and livestock sectors, stressing the need for coordinated global mitigation strategies [25]. CH4 emissions are often dominated by a small number of “super-emitting” facilities that account for a disproportionate share of total CH4 release [19]. Airborne measurements over Four Corners reveal a lognormal CH4 emission distribution, with the top 10% of super-emitters contributing 49–66% of total flux [26]. Super-emitters in natural gas infrastructure are primarily driven by abnormal operating conditions, making a small fraction of sites responsible for a disproportionate share of CH4 emissions [27]. Across multiple U.S. basins found that a small fraction of CH4 local sources contribute disproportionately to total CH4 emissions. These super-emitters account for approximately 40% of regional CH4 fluxes [28]. Yet, reliable quantification remains challenging due to incomplete reporting, limited ground-based monitoring, and substantial differences in waste management practices across countries and regions.

At the regional scale, during the 2010–2019 decade, Brazil was identified as a CH4 high-emitting region with 47 (41–58) Tg CH4 yr−1 [29]. This estimate corresponds to a range of 41–58 Tg CH4 yr−1, with a central value of approximately 47 Tg CH4 yr−1. Brazil is also among the world’s top solid waste producers, generating more than 80 million tons annually, with nearly 40% of collected waste still disposed of in uncontrolled dumpsites and open dumps [30]. The persistence of uncontrolled disposal practices and inadequate treatment indicates that the solid waste sector remains a major contributor to national CH4 emissions [30,31]. This challenge has been recognized for more than a decade, as earlier studies already emphasized the uncontrolled release of biogas from open dumping and its implications for climate change [32]. Northern and central Brazil, encompassing both Amazonian states and the Cerrado transition region, are of particular concern, as rapid urban expansion, high organic waste fractions, and climatic conditions may amplify CH4 production. However, the region’s contribution to national and global CH4 budgets remains poorly constrained, with limited field-based data and few systematic assessments.

The advent of spaceborne imaging spectrometers has transformed CH4 monitoring, enabling the detection and quantification of plumes at facility scale. Instruments such as the Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT) on the International Space Station and the recently launched Tanager-1 satellite, operated by Carbon Mapper, offer hyperspectral measurements in the shortwave infrared (SWIR) region where CH4 exhibits distinct absorption features. In parallel, the Sentinel-5P mission TROPOMI provides complementary global CH4 observations at coarser spatial resolution, enabling regional context and long-term trend assessment. These systems provide spatial resolutions of 30–60 m, allowing the direct identification of landfill plumes and opening new opportunities for characterizing CH4 super-emitters in regions where ground-based data are sparse. In this study, we analyze all CH4 plume detections from the Carbon Mapper public database within northern and central Brazil. By examining 16 sites across nine states—including Amazonas, Pará, Amapá, Roraima, Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Goiás, Piauí, and Mato Grosso do Sul—we assess variability in plume strength, emission persistence across repeated satellite overpasses, and regional contrasts between the Amazon forest biome and the Cerrado transition zone. Using a consistent adaptive thresholding algorithm, we identify and characterize super-emitter events, quantify their relative contribution to the emission distribution, and evaluate their implications for Brazil’s CH4 mitigation priorities. Our findings provide a systematic satellite-based assessment of landfill CH4 emissions in this region, highlighting both the disproportionate role of a limited number of persistent super-emitters and the broader heterogeneity of waste-related emissions. By situating these results within Brazil’s climate policy context, we demonstrate the potential of targeted mitigation strategies supported by satellite monitoring to achieve rapid and cost-effective CH4 reductions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Focus and Geographic Scope

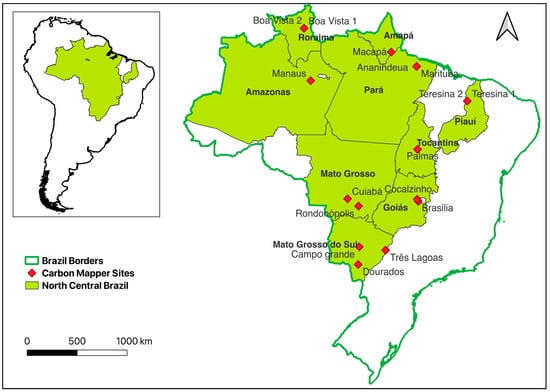

This study was designed to include all CH4-emitting sites registered by Carbon Mapper in northern and central Brazil, a region that encompasses both densely populated urban areas and rapidly expanding peri-urban zones. We specifically examined all sites provided by Carbon Mapper (https://carbonmapper.org, accessed on 19 September 2025), which are distributed across nine states: Amazonas, Pará, Amapá, Roraima, Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Goiás, Piauí, and Mato Grosso do Sul. Although the states of Acre, Rondônia, and Maranhão also belong to the defined region of study, they do not include any site. These states collectively span the Amazon forest biome and the Cerrado-Amazonia transition region, providing a natural contrast between humid tropical conditions and more seasonal savanna ecosystems (Figure 1). As a result of this site-inclusive approach, the majority of detections correspond to the solid waste sector, while a small number of cases are associated with other sectors such as a coal mine or undetermined sources. The solid waste sector in Brazil remains a critical, yet under-characterized, contributor to national CH4 emissions. Open landfills and unmanaged disposal sites often generate strong localized emission plumes due to anaerobic decomposition processes. These “super-emitter” events can be intermittent but are disproportionately important in shaping the regional CH4 budget. Several sites have only a single valid detection in the Carbon Mapper archive. These cases reflect limitations in satellite coverage rather than methodological constraints. As such, results for these sites represent isolated snapshots and should not be interpreted as long-term emission behavior. This study focuses on analyzing observed spatial patterns in Carbon Mapper CH4 detections. A quantitative investigation of the causal drivers behind inter-site emission variability (e.g., climate, landfill engineering, operational practices) is beyond the scope of the available data and is therefore not attempted here. The temporal span (2024–2025) reflects the full set of publicly available Carbon Mapper observations over the study area; therefore, the analysis captures short-term variability but does not resolve seasonal or long-term emission trends.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of Carbon Mapper sites for north-central Brazil states. The red dots indicate the Carbon Mapper sites, and the Brazilian states in which they are located are shown in light green. The square in the upper left corner locates the study area within South America. Brazil vector layers were obtained from the DIVA-GIS website (https://diva-gis.org/data.html, accessed on 3 December 2025), and the South America vector layer was obtained from the Stanford University Library Digital Repository (https://purl.stanford.edu/vc965bq8111, accessed on 3 December 2025). The figure was produced with QGIS Version 3.34 [33].

2.2. Dataset and Observation Sources

In this study, we relied on data provided by the Carbon Mapper public data portal (https://carbonmapper.org, accessed on 19 September 2025), which integrates CH4 plume detections from advanced imaging spectrometers. Carbon Mapper represents the most comprehensive, systematically curated, and openly available database of facility-scale CH4 emissions currently accessible. It combines measurements from the Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT)—a hyperspectral imaging spectrometer deployed onboard the International Space Station (ISS)—and the Tanager-1 satellite, ensuring both continuity and cross-calibration of observations. These instruments provide hyperspectral detection capabilities at high spatial resolution, enabling the identification and quantification of individual plumes that are not captured by coarser-resolution satellite products. Importantly, Carbon Mapper applies a standardized processing pipeline and quality control procedures, ensuring consistent inter-comparison of emissions across regions and sectors. Its combination of scientific reliability, open-access framework, and unique suitability for resolving CH4 super-emitters makes it particularly valuable for studies in diverse environments such as northern and central Brazil. All plume detections were obtained from the Carbon Mapper Open Data Portal, which provides preprocessed Level-3A CH4 retrievals. It should be noted that plume detections are obtained from gas retrievals based on absorption features detected from Top of Atmosphere (TOA) radiance, so a detailed atmospheric correction is not needed for this purpose [34]. The Carbon Mapper product analyzed corresponds to a column-integrated CH4 concentration enhancements in units of parts per million meter (ppm·m). Each raster pixel represents the excess CH4 concentration above the estimated local background, integrated along the atmospheric path length. Therefore, the resulting units are ppm-m which quantify the concentration anomaly integrated over a vertical column depth. We analyzed a dataset comprising approximately 16 sites and 40 individual plume detections, corresponding to multiple overpasses across 2024–2025 (Table 1).

Carbon Mapper provides georeferenced CH4 concentration and plume products derived from two complementary spaceborne imaging spectrometer sources. EMIT provides opportunistic CH4 observations with relatively broad spatial coverage and variable overpass timing. EMIT has a swath width of ~74 km, a spatial resolution of ~60 m, a spectral sampling of 7.5 nm, and a spectral range of 380–2500 nm, with a medium detection sensitivity for CH4 of 100–1000 kg h−1 [35,36]. Tanager-1—the first dedicated Carbon Mapper satellite launched in 2024—is designed for systematic CH4 and CO2 monitoring with higher temporal frequency and targeted tasking. Tanager-1 flies in a near-polar, sun-synchronous orbit with a nadir swath width of ~19 km, ~30 m nadir spatial resolution, ~5 nm spectral sampling over a spectral range of ~400–2500 nm, and a revisit rate of 2–5 days at mid-latitudes. It achieves a high detection sensitivity for CH4 of ~100 kg h−1 [34]. Both hyperspectral instruments operate in the shortwave infrared (SWIR) spectral region, where CH4 has diagnostic absorption features. Data products provided through Carbon Mapper include geolocated raster files of CH4 enhancement values (ppm-m), derived from imaging spectroscopy retrieval algorithms. In this study, we employed georeferenced CH4 concentration. Each detection corresponds to a raster field of CH4 column enhancement centered over an emitting site. By compiling detections across multiple dates, we assessed variability in plume strength among different facilities, as well as the persistence of emissions across repeated overpasses, which indicates whether sites act as continuous or intermittent super-emitters.

Table 1.

The complete list of sites included in the study. The table present the sites’ names, Brazilian states to which they belong, the emitting sectors, and the number of samples registered. The population data and was obtained from IBGE, Brazil [37] as well as the information on biomes [38]. Although states might expand across various biomes, the table indicates the biome that correspond to the site observed.

Table 1.

The complete list of sites included in the study. The table present the sites’ names, Brazilian states to which they belong, the emitting sectors, and the number of samples registered. The population data and was obtained from IBGE, Brazil [37] as well as the information on biomes [38]. Although states might expand across various biomes, the table indicates the biome that correspond to the site observed.

| Site Name | State | Biome | Population | Sector | Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manaus | Amazonas | Amazon | 4,321,616 | Solid waste | 5 |

| Marituba | Pará | Amazon | 8,711,196 | Solid waste | 5 |

| Ananindeua | Pará | Amazon | 8,711,196 | Solid waste | 1 |

| Macapá | Amapá | Amazon | 806,517 | Solid waste | 3 |

| Boa Vista 1 | Roraima | Amazon | 738,772 | Solid waste | 1 |

| Boa Vista 2 | Roraima | Amazon | 738,772 | Undetermined | 1 |

| Palmas | Tocantins | Cerrado | 1,586,859 | Solid waste | 1 |

| Cuiabá | Mato Grosso | Cerrado | 3,893,659 | Solid waste | 3 |

| Rondonópolis | Mato Grosso | Cerrado | 3,893,659 | Solid waste | 1 |

| Brasilia | Goiás | Cerrado | 7,423,629 | Solid waste | 6 |

| Cocalzinho | Goiás | Cerrado | 7,423,629 | Coal mine | 1 |

| Teresina 1 | Piaui | Cerrado | 3,384,547 | solid waste | 2 |

| Teresina 2 | Piaui | Cerrado | 3,384,547 | solid waste | 1 |

| Três Lagoas | Mato Grosso do sul | Cerrado | 2,924,631 | solid waste | 1 |

| Campo Grande | Mato Grosso do sul | Cerrado | 2,924,631 | solid waste | 6 |

| Dourados | Mato Grosso do sul | Cerrado | 2,924,631 | solid waste | 2 |

2.3. Distribution Characterization

Given that CH4 super-emitters are known to follow heavy-tailed distributions [26,28], we applied statistical distribution fitting and goodness-of-fit tests to rigorously characterize the observed variability and extreme values in the emission data. To characterize the distribution of CH4 emissions across all studied sites, we first excluded zero or missing values to focus on valid emission measurements. The resulting data were treated as a continuous, positive-valued variable. We tested several candidate probability distributions—lognormal, Weibull, gamma, and exponential—for their ability to describe the data. Parameter estimation was performed using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) implemented in R (version 4.3.0) [39] with the fitdistrplus package [40]. For each fitted model, we calculated goodness-of-fit statistics, including the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistic, Cramer–von Mises (CvM) statistic, and Anderson–Darling (AD) statistic. To compare model performance, we also computed the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for each distribution. Visual inspection complemented the statistical tests. We plotted histograms of the empirical data with fitted probability density functions overlaid and generated complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) plots on a log-log scale to assess tail behavior and the presence of extreme super-emitter events.

The following subsection details the adaptive plume detection and quantification algorithm used to consistently extract plume extent, areally weighted enhancement, and strength from these raster products.

2.4. Adaptive Super-Emitter Detection and Quantification

We developed an adaptive thresholding algorithm to identify and characterize CH4 plume patches from satellite-derived raster products across multiple sites. The adaptive thresholding algorithm developed in this study operates on Carbon Mapper CH4 enhancement products level 3A. This algorithm is designed for high-spatial-resolution CH4 enhancement products from imaging spectrometers such as EMIT and Tanager-1. Owing to the coarse spatial resolution and different measurement characteristics of sensors like TROPOMI, which do not resolve individual plumes, the method is not directly applicable to TROPOMI data. The workflow was implemented in R (version 4.3.0) [39] and was designed to operate directly in the native Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate reference system to preserve spatial accuracy in area and flux estimates. The objective of this procedure is to detect super-emitter plumes, i.e., localized CH4 sources with disproportionately high concentrations compared to the surrounding background. This is achieved by applying an adaptive thresholding scheme that adjusts to the statistical distribution of CH4 values at each site, ensuring robust detection even under varying atmospheric or instrumental conditions.

2.4.1. Data Ingestion and Preprocessing

For each study site, all available GeoTIFF rasters were loaded and projected to the appropriate UTM zone (EPSG code adjusted per site). Each raster, denoted as

represents CH4 column enhancement values expressed in parts per million–meter, (ppm·m) derived from imaging spectroscopy retrievals over a spatial grid of pixels with resolution . The unit ppm·m corresponds to the path-integrated excess CH4 concentration along the atmospheric column relative to the local background (i.e., 1 ppm·m represents an excess of 1 part per million sustained over a 1-m path length). By standardizing all rasters into a common UTM-based framework, the algorithm ensures that pixel areas are measured in meters, allowing for precise calculation of plume extent and areally weighted CH4 enhancements. This step avoids distortions that would otherwise occur if geographic (latitude–longitude) coordinates were used directly.

2.4.2. Adaptive Threshold Selection

To delineate plume pixels, we computed an adaptive threshold based on quantiles of the aggregated pixel value distribution across all rasters within the site. The CH4 enhancement fields retrieved by Carbon Mapper do not exhibit a bimodal intensity distribution that would enable a single universal threshold. We therefore use an adaptive percentile-based strategy in which the segmentation begins with a conservative threshold (95th percentile) to isolate the plume core, and the quantile is gradually relaxed to 75% to recover diffuse plume edges. High percentiles suppress noise-driven false positives, while moderate percentiles improve sensitivity to lower-contrast CH4 enhancements. This progressive relaxation approach is consistent with widely used adaptive thresholding and robust image segmentation techniques that rely on percentile-based statistics to balance sensitivity and specificity in the absence of well-defined intensity clusters. The selected percentile range was determined empirically through exploratory evaluation across representative scenes and is intended as a practical operational method rather than a theoretically optimized decision rule. Specifically, we iteratively evaluated the set of quantiles

where is the -th quantile. For each candidate , we defined a binary mask

and verified that the total number of plume pixels

satisfied the condition , with . The first quantile threshold meeting this condition was selected as . If no quantile satisfied the criterion, a fallback rule was applied:

where and are the mean and standard deviation of all pixel values, respectively. This design allows the algorithm to flexibly adapt to the data distribution at each site. By starting with stringent quantiles (e.g., 95th percentile) and relaxing them gradually (down to 75th percentile), the method balances sensitivity and specificity. The fallback rule provides robustness in cases where extreme plumes are absent but moderate anomalies exist. In this way, no site is discarded due to lack of statistical extremes, and every dataset yields a threshold suitable for plume detection. If the highest percentile threshold (e.g., p95) is accepted because at least one image yields a non-zero plume, this threshold is applied uniformly to all images of the site; consequently, images with weaker enhancements may return zero detected plume pixels. In practice, for most sites the 95th percentile (p95) threshold was sufficient to identify plume pixels, (i.e., ), and thus this quantile was retained as the adopted threshold rule for the site. Consequently, the more conservative p95 threshold consistently captured the core high-contrast plume structures without requiring further relaxation of the quantile. The adaptive procedure begins with a stringent cutoff, evaluates whether a plume is detectable, and only relaxes the threshold when necessary. For most scenes, the p95 quantile provided a stable and specific delineation of plume pixels, which explains why this threshold appears most frequently in the output tables.

2.4.3. Plume Characterization

For each raster , plume pixels were identified as . The total number of plume pixels was recorded as

The mean CH4 enhancement within plume pixels was computed as

Pixel surface area was determined from raster resolution:

and total plume area was estimated as

We defined the plume strength as the product of mean enhancement and plume area:

plume strength () was computed as the product of mean enhancement (in ppm·m) and plume area (in m2), yielding units of ppm·m3. This integrated metric represents the total excess column-integrated CH4 content within the detected plume footprint. This formulation integrates both the magnitude of CH4 enhancement and the spatial extent of the plume, yielding an areally weighted emission indicator. From a physical perspective, this strength metric can be interpreted as a proxy for the total excess CH4 content contained in the plume footprint. It thus provides a meaningful way to rank detected plumes and identify the largest contributors to site-level emissions. The plume-strength metric (average enhancement × plume area) is used here as an observational indicator of emission intensity. This definition does not incorporate atmospheric transport effects such as wind speed or atmospheric stability, as our objective is not to derive absolute CH4 fluxes but to compare relative plume intensities across sites. Including wind-dependent transport modeling would require a full flux inversion framework (e.g., IME or Gaussian plume models), which is beyond the scope of this study. For this reason, the plume-strength values reported here should be interpreted as diagnostic remote-sensing indicators rather than transport-corrected flux estimates. Although plume strength is a robust metric for comparing events, its absolute value is subject to several conceptual sources of uncertainty. First, the adaptive thresholding algorithm introduces minor variability in plume delineation, as different percentile levels may slightly expand or contract the detected enhancement region. Second, plume strength depends on spatial aggregation across pixels, meaning small differences in plume boundary geometry can propagate into the integrated value. Third, the temporal sampling of available scenes affects how representative the detected plumes are of long-term behavior. These uncertainties primarily influence absolute magnitudes, while relative differences between sites and the identification of super-emitters remain stable. The adaptive thresholding method is intrinsically applicable to repeated monitoring at the same site, as it processes each methane-enhancement raster independently and can therefore be applied to any sequence of scenes to characterize temporal variations in plume strength or occurrence. When new observations become available, the algorithm can immediately generate updated plume-strength estimates using the same workflow. However, the method does not provide real-time outputs, since its temporal resolution is constrained by the acquisition and availability of new satellite products rather than by the processing algorithm itself.

2.4.4. Super-Emitter Fraction Estimation

To quantify the contribution of extreme CH4 emission sites (“super-emitters fraction”), we first removed zero or missing values from the dataset, focusing on valid emission measurements for each site . We defined super-emitters fraction using a percentile-based threshold approach. Specifically, the super-emitter threshold was set as the 90th percentile of the observed emission strengths:

where is the vector of non-zero emission strengths. The 90th percentile was selected as the super-emitter threshold because it effectively isolates the upper decile of the emission strength distribution, capturing the most anomalous and influential sources while maintaining statistical robustness. The 90th percentile provides a balance between sensitivity and robustness: it excludes noise or moderate outliers (e.g., 75th–85th percentile) while still including enough observations to analyze variability within the high-emission tail. Percentiles above the 95th or 99th would identify fewer points, risking undersampling or instability in small datasets. Following previous airborne CH4 studies that demonstrated heavy-tailed, lognormal flux distributions where the top 10% of emitters contributed more than half of the total observed emissions [26], we adopted the 90th percentile as the threshold for defining super-emitters. Therefore, the super-emitter threshold was set at the 90th percentile of observed plume strengths, consistent with the heavy-tailed distribution of CH4 emissions, where a small fraction of sources contributes disproportionately to total fluxes [18,28]. The distribution of plume-level CH4 enhancements in north-central Brazil is strongly skewed, with a heavy tail characteristic of landfill emissions. In such distributions, high-percentile thresholds provide a robust and ecologically meaningful way to isolate extreme emitters. We therefore adopt the 90th percentile as a non-parametric operational definition of “super-emitters,” consistent with the empirical structure of the regional dataset and with established practices in CH4 remote-sensing studies. Sites exceeding this threshold were labeled as super-emitters:

The fraction of super-emitter sites was then computed as:

where is an indicator function that equals 1 if the site is a super-emitter and 0 otherwise. A summary table of all sites, including mean enhancement, number of contributing pixels, area, emission strength, and super-emitter status, was generated and saved as a CSV file. A visual representation highlighting super-emitter sites was produced using a log-scaled scatter plot of site emission strengths, where super-emitter points were marked in red.

2.4.5. Site-Level and Global Analysis and Visualization

For each site, plume statistics were extracted for all rasters and stored in tabular form. The plume with maximum was designated as the site-level highest strength patch. Across all sites, results were merged into a global database for comparative analysis. This hierarchical design (per-raster, per-site, global) allows comparisons between temporal events within a single site and spatial differences between sites. By consistently applying the same thresholding and quantification scheme, differences observed across regions can be interpreted as arising from real variations in CH4 activity rather than methodological inconsistencies. For diagnostic purposes, raster values were plotted using plasma color scales (dark blue, through purple, and then into bright yellow hues), with plume pixels () overlaid as red markers to highlight the detected excess CH4 regions. In addition, the point identifying the pixels surpassing the adaptive threshold were individually saved as shapefiles.

3. Results

3.1. Variability in Emission Strength Across Sites

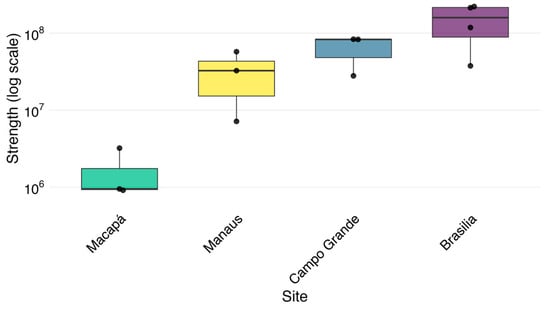

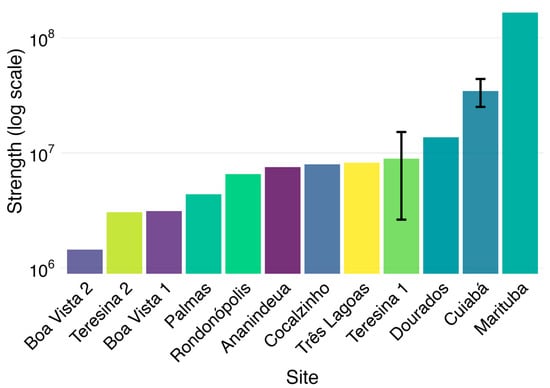

Figure 2 presents the distribution of CH4 plume strengths (expressed as ppm·m3, log10 scale) detected at four representative solid waste sites: Macapá, Manaus, Campo Grande, and Brasília. Despite the relatively small sample sizes at each site (n = 3–4 detections), consistent differences in plume strength were observed across regions. At the lower end, Macapá exhibited the weakest plumes, with median log10 emission strength of 5.98 (≈9.6 × 105 ppm·m3). The interquartile range (IQR) was narrow (Q1 = 5.97; Q3 = 6.32), and maximum values did not exceed 6.51 (≈3.2 × 106 ppm·m3), indicating relatively small and stable emissions. Manaus presented intermediate plume magnitudes, with a median log10 strength of 7.51 (≈3.2 × 107 ppm·m3). The variability was greater than in Macapá (IQR = 7.30–7.65), and the strongest plume reached 7.76 (≈5.7 × 107 ppm·m3). This suggests both higher baseline emissions and episodic intensification, likely reflecting differences in landfill scale and waste management practices in this larger metropolitan area. Campo Grande showed systematically stronger plumes, with a median of 7.92 (≈8.3 × 107 ppm·m3) and a very narrow IQR (7.74–7.92). Maximum values reached 7.92 as well, suggesting consistently high-emitting conditions across all detections. Finally, Brasília displayed the strongest plumes among the analyzed sites. The median log10 strength was 8.22 (≈1.7 × 108 ppm·m3), with an IQR spanning 7.99–8.33. Maximum values exceeded 8.34 (≈2.2 × 108 ppm·m3), nearly two orders of magnitude greater than Macapá. These results highlight the dominant contribution of Brasília’s landfill emissions relative to other sites, consistent with both urban scale and waste generation intensity. Overall, the analysis reveals a clear regional gradient in CH4 emission strength: Amazonian sites (Macapá and Manaus) show lower-to-intermediate plumes, whereas Cerrado-transition sites (Campo Grande and Brasília) are characterized by systematically stronger emissions. This pattern underscores the influence of both climatic context and landfill management practices in determining CH4 release intensity. Figure 3 presents the mean CH4 plume integrated strengths (expressed in ppm·m3, log10 scale) across 12 sites in northern and central Brazil with samples 2. Values are ordered from lowest to highest average strength, with error bars. Plume strengths spanned over two orders of magnitude, from 106 ppm·m3 at Boa Vista 2 (mean = 6.16 log10 ppm·m3) to above 108 ppm·m3 at Marituba (mean = 8.22 log10 ppm·m3). Sites with only a single detection, such as Marituba, Dourados, Palmas, and Ananindeua, displayed isolated but strong events, suggesting the presence of significant localized CH4 releases. Among sites with repeated observations, Cuiabá (n = 2) exhibited consistently high plume strengths (mean = 7.54 log10 ppm·m3, SD = 0.97), ranking second overall, while Teresina 1 (n = 2) showed intermediate levels (mean = 6.95 log10 ppm·m3, SD = 0.90). In contrast, Boa Vista 1 (mean = 6.50 log10 ppm·m3) and Teresina 2 (mean = 6.49 log10 ppm·m3) presented relatively weak emissions. Overall, the analysis indicates that while most sites in the region emit CH4 at moderate levels, a subset—particularly Marituba and Cuiabá—contributes disproportionately to the regional super-emitter profile. These findings emphasize the spatial heterogeneity of CH4 emission strengths across facilities, with some sites acting as persistent high-intensity sources while others display either isolated events or consistently lower plume magnitudes. A temporal distribution of strength for all studied sites in presented in Supplementary Material Figure S1.

Figure 2.

Distribution of CH4 plume integrated strengths (ppm·m3, log10 scale) for four representative sites in northern and central Brazil. Boxplots indicate the interquartile range (IQR) with the horizontal line marking the median, whiskers extending to 1.5× IQR, and individual points representing detections outside this range. Sites in the Amazon region (Macapá, Manaus) exhibit systematically lower plume strengths compared to sites in the Cerrado-transition region (Campo Grande, Brasília), highlighting regional contrasts in CH4 emission intensity. Boxplots show the distribution of CH4 plume strengths for each site. Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), horizontal lines mark the median, whiskers indicate the data range, and dots represent individual detections. This summarizes the variability and dispersion of observed plume strengths.

Figure 3.

Regional comparison of CH4 plume detections from solid waste sites in northern and central Brazil, based on Carbon Mapper data (EMIT and Tanager-1). Bars represent the aggregated plume strength (ppm·m3) per site, grouped by state, highlighting variability across the Amazon forest states (Amazonas, Pará, Amapá, Roraima) and the Cerrado transition region (Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Goiás, Piauí, Mato Grosso do Sul). The distribution of detections demonstrates regional contrasts in emission intensity, reflecting differences in waste management practices, climate, and urbanization patterns. The error bar corresponds to sites with 2 sample while bars without error bar have only one sample.

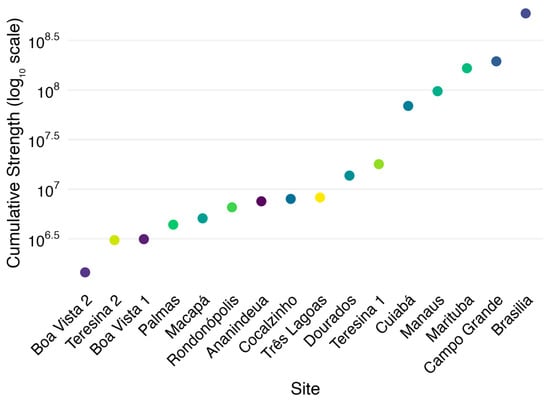

Cumulative plume strength (expressed as log-transformed total values in ppm·m3) for CH4 emissions detected at all studied sites across northern and central Brazil is shown in Figure 4. A total of 16 sites were included, with 40 individual detections from EMIT and Tanager-1 observations reported in the Carbon Mapper dataset. The strongest cumulative CH4 signals were observed in Brasília, with a total plume strength of ~5.92 × 108 ppm·m3 (log 8.77), based on four separate detections. Other sites with high cumulative values included Campo Grande (1.94 × 108 ppm·m3; log 8.29; 3 detections), Marituba (1.66 × 108 ppm·m3; log 8.22; single detection), and Manaus (9.72 × 107 ppm·m3; log 7.99; 3 detections). Intermediate emission strengths were found in Cuiabá (6.91 × 107 ppm·m3; log 7.84; 2 detections), Teresina 1 (1.79 × 107 ppm·m3; log 7.25; 2 detections), and Dourados (1.37 × 107 ppm·m3; log 7.14; single detection). A second detection from Teresina (Teresina 2) yielded a lower total (3.07 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.49). At the lower end of the distribution, single detections with relatively weak cumulative strength were reported for Três Lagoas (8.25 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.92), Cocalzinho (7.98 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.90), Ananindeua (7.55 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.88), Rondonópolis (6.57 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.82), Macapá (5.08 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.71; 3 detections), and Palmas (4.39 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.64). The weakest plumes were found in Boa Vista 1 (3.14 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.50) and Boa Vista 2 (1.45 × 106 ppm·m3; log 6.16). Overall, the results indicate strong contrasts between regions. Brasília and Campo Grande, both located in the Cerrado transition zone, exhibited the most persistent and strongest emissions, with multiple detections contributing to their high cumulative values. In contrast, several Amazonian cities such as Manaus, Marituba, and Ananindeua displayed significant but more variable plume strengths, often linked to single detection events. Sites like Boa Vista and Palmas showed much weaker plumes, possibly reflecting smaller landfill operations or less persistent emission episodes. These findings highlight both the spatial heterogeneity and temporal variability of CH4 emissions from waste sector sites in Brazil, underlining the need for sustained monitoring across diverse ecological and socio-economic regions.

Figure 4.

Cumulative CH4 plume strength (log-transformed, ppm·m3) from all studied sites in northern and central Brazil, derived from Carbon Mapper detections using EMIT and Tanager-1. Points represent the summed plume strength per site, with the number of detections ranging from 1 to 4. Strongest emissions were observed in Brasília and Campo Grande (Cerrado transition region), while intermediate and weaker signals were recorded at sites in both the Cerrado and Amazon states, illustrating regional variability in landfill-related CH4 emissions.

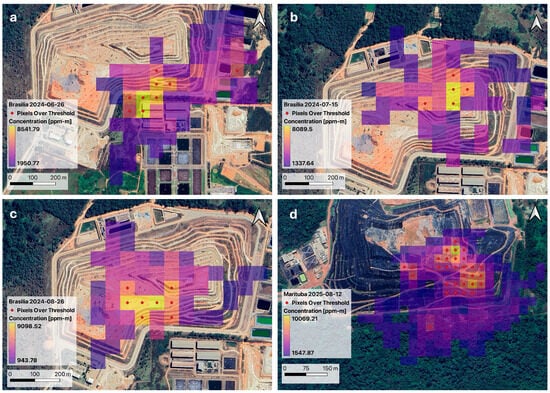

3.2. Diagnostic Plume Concentration Maps

To illustrate the detection and quantification process, we present diagnostic maps of CH4 plumes for the four sites with the highest estimated plume strengths across our study region (Figure 5). These plots combine the spatial distribution of column-averaged CH4 enhancements (ppm-m) with adaptive thresholding to identify pixels that most likely represent plume cores. Pixels exceeding the detection threshold are marked with red dots, and their concentrations, multiplied by pixel area, form the basis for estimating plume strength (ppm·m3). Panels a–c show three separate overpasses at the Brasília landfill (Federal District), highlighting the persistence of strong CH4 emissions across different dates in 2024. On 26 June 2024 (Figure 5a), nine above-threshold pixels were identified, with a mean enhancement of 7030 ppm-m covering ~31,544 m2, yielding a total plume strength of 2.22 × 108 ppm·m3. A subsequent detection on 15 July 2024 (Figure 5b) revealed five pixels above threshold with a mean enhancement of 6803 ppm-m across ~17,400 m2, corresponding to a lower integrated strength of 1.18 × 108 ppm·m3. By 26 August 2024 (Figure 5c), eight pixels exceeded the threshold, averaging 7625 ppm-m over ~28,048 m2, resulting in a plume strength of 2.14 × 108 ppm·m3. Together, these repeated detections over Brasília demonstrate both the persistence and temporal variability of landfill-related CH4 emissions, with plume cores consistently aligned over the active waste disposal areas. Panel 5d displays the detection for Marituba (Pará state) on 12 August 2025, where 30 pixels exceeded the adaptive threshold, with a mean enhancement of 6134 ppm-m across ~27,000 m2. The resulting plume strength of 1.66 × 108 ppm·m3 places this site among the most significant emitters in the dataset. The plume spatial extent covers a large fraction of the landfill area, suggesting extensive emission sources across the waste surface rather than being confined to a single hotspot. Overall, these diagnostic maps illustrate the ability of high-resolution imaging spectroscopy (EMIT and Tanager-1) to identify CH4 plumes at the scale of individual landfills. They also highlight differences in emission persistence (e.g., repeated detections at Brasília) and intensity (e.g., extensive emission extent at Marituba), reinforcing the solid waste sector as a major and heterogeneous source of CH4 in northern and central Brazil.

Figure 5.

Diagnostic CH4 plume maps. Examples of diagnostic Carbon Mapper retrievals over Brazilian landfills ((a–c) Brasilia, (d) Marituba), showing detected CH4 enhancements (ppm-m), plume footprints. Each panel includes the retrieved mean enhancement, number of pixels contributing to the detection, estimated plume area (m2), and emission strength (ppm·m3) indicated as red dots. These maps illustrate the geospatial context of detections, plume morphology, and variability in source strength across sites and dates. The CH4 enhancement rasters (with transparency) and their associated point shapefiles were overlaid on Google Maps Satellite imagery. The individual plots were generated using QGIS software (Version 3.34) [33].

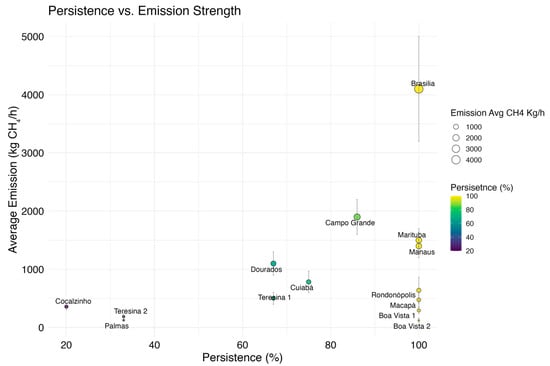

3.3. Persistence of Emissions and Variability in Plume Strength

Figure 6 presents the relationship between emission persistence (% of repeated detections across available overpasses) and average CH4 emission rates (kg CH4 h−1, defined as the daily average of all emissions attributed to a source, weighted by persistence) for the studied sites. These measures were obtained directly from the Carbon Mapper metadata accompanying each plume detection and are therefore independent from the plume strength metric (ppm·m3) calculated in this study. Figure’s point size is proportional to the number of samples, and color scale indicates emission magnitude. Two clear patterns emerge. First, persistent emitters (≥75% recurrence) are generally associated with higher average CH4 emission rates. For instance, Brasília (Federal District) exhibited the highest emission intensity, with an average of 4100 ± 900 kg CH4 h−1 across six samples and 100% persistence, marking it as the most consistent super-emitter in the dataset. Similarly, Marituba (Pará) and Manaus (Amazonas) showed 100% persistence, with average emissions of 1500 ± 200 kg CH4 h−1 and 1400 ± 200 kg CH4 h−1, respectively, across five detections each. Second, intermediate emitters displayed moderate emission magnitudes and less consistent recurrence. Campo Grande (Mato Grosso do Sul), with six samples, averaged 1900 ± 300 kg CH4 h−1 at 86% persistence, while Cuiabá (Mato Grosso) emitted 784 ± 185 kg CH4 h−1 at 75% persistence. Dourados (Mato Grosso do Sul) also reached 1100 ± 200 kg CH4 h−1 but with only 67% persistence. At the lower end, sites such as Teresina 1 (Piauí) showed relatively modest emissions (502 ± 104 kg CH4 h−1) with 67% persistence, whereas Teresina 2 averaged just 188 ± 49 kg CH4 h−1 at 33% persistence. Palmas (Tocantins) stood out with the weakest landfill emission (127 ± 22 kg CH4 h−1, persistence of 33%). Finally, single-detection cases such as Rondonópolis (640 ± 222 kg CH4 h−1), Boa Vista 1 (294 ± 54 kg CH4 h−1), and Boa Vista 2 (122 ± 41 kg CH4 h−1) confirm localized but notable CH4 releases, albeit without recurrence confirmation. An anomalous case is Cocalzinho (coal mine, Goiás), which showed 359 ± 55 kg CH4 h−1 with very low persistence (20%), highlighting the importance of sectoral attribution in CH4 source assessments. It is important to note that the average emission rate is persistence-weighted, which means that these two metrics are not fully independent. The joint analysis presented in Figure 6 is therefore intended to illustrate their co-variation across sites, rather than strict independence. In summary, the persistence–emission relationship suggests that landfills with higher mean emissions also tend to be the most reliable and continuous CH4 super-emitters (e.g., Brasília, Manaus, Marituba). Conversely, low-emission sites are typically characterized by sporadic or single detections, reflecting either intermittent activity or detection limits. This reinforces the significance of repeated monitoring in distinguishing between transient plumes and structurally persistent emission sources.

Figure 6.

Persistence versus average CH4 emission strength. Scatter plot of emission persistence (percentage of overpasses with repeated detections) against average emission rate (kg CH4 h−1) for all sites. Point size is proportional to the number of samples, and point color represents emission magnitude. Highly persistent emitters (e.g., Brasília, Manaus, Marituba) show both strong and recurrent emissions, while low-persistence sites (e.g., Palmas, Teresina 2, Boa Vista) correspond to weaker or sporadic emissions.

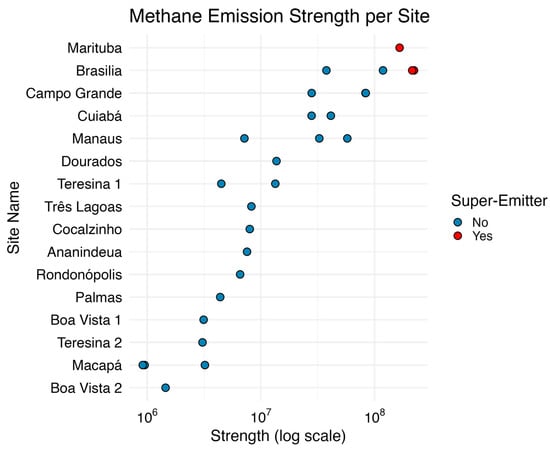

3.4. Distribution and Super-Emitters Fraction

The statistical characterization of CH4 emission strengths across the studied sites revealed that the observed values are best described by a log-normal distribution. Alternative distributions, including Weibull, gamma, and exponential, either fitted poorly or failed to converge, supporting the presence of extreme super-emitter events consistent with a heavy-tailed distribution. Goodness-of-fit tests demonstrated that the log-normal model consistently outperformed the Weibull distribution. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistic was 0.126 for the log-normal fit compared to 0.171 for Weibull, the Cramer–von Mises (CvM) statistic was 0.055 versus 0.104, and the Anderson–Darling (AD) statistic was 0.336 versus 0.590, indicating closer agreement between the empirical data and the log-normal model. Information criteria further supported this conclusion, with the log-normal distribution yielding lower Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC = 997.87) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC = 1000.46) values than the Weibull distribution (AIC = 1000.31, BIC = 1002.91). Visual confirmation of the fit and tail behavior is provided in Supplementary Material Figures S2–S6, including density comparisons, cumulative distribution functions, QQ-plots, histograms with log-normal overlays, and log-log complementary cumulative distribution functions (CCDFs). The suitability of the log-normal model reflects the heavy-tailed nature of CH4 emissions, consistent with the occurrence of extreme super-emitter events at several sites. While most sites exhibited moderate CH4 emissions, a small fraction contributed disproportionately high values, highlighting the critical role of super-emitters in the overall emission distribution. To quantify the contribution of extreme CH4 emission events, we identified super-emitter sites as those with strength values exceeding the 95th percentile of the nonzero emission dataset. The total dataset included 27 valid emission observations after excluding zero or missing values. Using this threshold, the super-emitter cut-off was determined to be 1.37 × 108 ppm·m3 (137,270,566), corresponding to the 95th percentile of all valid plume strength values, and representing the boundary between routine landfill emissions and exceptional high-intensity events. Applying this criterion, 3 sites—two in Brasilia and one in Marituba—were classified as super-emitters, representing 11.1% of the total valid sites. Figure 7 presents the distribution of plume strengths (ppm·m3) for all detected sites, plotted on a logarithmic scale. Most sources clustered between 106 and 107 ppm·m3, with relatively modest enhancements and plume extents. Examples include: Boa Vista 2 (1.45 × 106 ppm·m3); Palmas (4.4 × 106 ppm·m3) and Teresina 2 (3.1 × 106 ppm·m3). Sites such as Ananindeua (7.5 × 106 ppm·m3) and Cocalzinho (8.0 × 106 ppm·m3) also fell within this mid-range, consistent with localized but non-persistent emissions. A second group of detections reached the 107–108 ppm·m3 range, indicating stronger plumes from larger landfill complexes. These included Cuiabá (2.8–4.1 × 107 ppm·m3), Campo Grande (2.8–8.3 × 107 ppm·m3), Dourados (1.4 × 107 ppm·m3), and Manaus (7.2 × 106–5.7 × 107 ppm·m3 across three detections). While substantial, these emissions were still below the “super-emitter” threshold. Only three events, highlighted in red, exceeded 108 ppm·m3 and were classified as super-emitters. Two correspond to Brasília, with plume strengths of 2.22 × 108 ppm·m3 (26 June 2024) and 2.14 × 108 ppm·m3 (26 August 2024), associated with mean enhancements above 7000 ppm-m and plume areas of ~28,000–31,000 m2. The third was detected at Marituba on 12 August 2025, with a plume strength of 1.66 × 108 ppm·m3, the product of a large plume footprint (30 pixels, 27,000 m2) and a mean enhancement of ~6100 ppm-m. These three super-emitters stand out by more than an order of magnitude compared with the majority of sites. The log scaling of the x-axis highlights the sharp contrast between routine landfill emissions (~106–107 ppm·m3) and exceptional super-emitter events (>108 ppm·m3). Collectively, this analysis demonstrates that while CH4 plumes are widespread across urban landfills, a very limited number of extreme events dominate the upper tail of the distribution and are likely responsible for a disproportionate share of regional CH4 fluxes.

Figure 7.

CH4 emission strength per site highlighting super-emitter sites. Each dot represents a site, with emission strength plotted on a logarithmic scale. Sites exceeding the 90th percentile of emission strength (super-emitters) are shown in red with black borders, while the remaining sites are shown in blue. This visualization illustrates that a small fraction of sites contributes disproportionately high emissions, emphasizing the critical role of super-emitter events in the overall distribution.

4. Discussion

This study provides a systematic satellite-based characterization of CH4 emissions from solid waste facilities and related point sources across northern and central Brazil. By leveraging high-resolution plume detections from Carbon Mapper, we were able to document substantial variability in plume strength, persistence, and spatial distribution across 16 sites spanning nine states. Several key insights emerge regarding the heavy-tailed nature of emissions, the dominance of a limited number of super-emitters, and the regional contrasts between Amazonian and Cerrado-transition environments.

Our results highlight clear geographic differences in CH4 emission intensity across Brazil’s north-central region. Sites located in the Cerrado transition zone, particularly Brasília and Campo Grande, consistently exhibited the strongest and most persistent CH4 plumes, with cumulative strengths exceeding 108 ppm·m3. These findings are consistent with the larger population density, waste generation rates, and the greater reliance on unmanaged landfill practices in these rapidly urbanizing centers. By contrast, Amazonian sites such as Macapá and Boa Vista presented much weaker and less frequent detections, typically below 107 ppm·m3, despite comparable landfill activity. This pattern suggests that both climatic conditions (e.g., higher rainfall and humidity potentially limiting aerobic cover efficiency) and differences in waste handling infrastructure shape emission magnitudes. Our analysis highlights substantial differences in landfill CH4 emissions across Brazilian regions. These contrasts reflect a combination of waste composition, landfill management practices, and climatic factors that favor anaerobic decomposition. Similar regional patterns have been observed elsewhere, where differences in regulatory enforcement and landfill infrastructure strongly influence emission magnitudes [12,13,30,31]. In Brazil, the persistence of uncontrolled dumpsites, particularly in northern and central states, underscores the challenge of constraining the contribution of the waste sector to national CH4 budgets. These findings align with earlier concerns that uncontrolled biogas release from dumpsites may represent a long-standing and under-quantified climate risk [32]. In addition, although focused on biomass-burning sources, recent multi-sensor analyses have revealed pronounced regional differences in methane emissions across the Amazon, underscoring that strong spatial contrasts in CH4 fluxes are not unique to the waste sector [41].

A striking feature of our results is the heavy-tailed distribution of landfill emissions, where a small number of facilities account for a disproportionately large share of total CH4 flux. This pattern has been consistently reported for CH4 point sources globally, including landfills [11,18,22,26]. In northern central Brazil, the dominance of a few high-emitting sites suggests that effective mitigation could be achieved by focusing on targeted interventions at these facilities. Out of 27 valid detections, only three exceeded the 95th percentile threshold and were classified as super-emitters—two at Brasília and one at Marituba. These accounted for 11% of detections but contributed orders of magnitude larger emission strengths compared to routine plumes. The Brasília detections alone consistently exceeded 2 × 108 ppm·m3 across multiple overpasses, demonstrating both persistence and intensity, whereas the Marituba event represented an extensive plume covering ~27,000 m2. Such extreme events highlight the significance of localized operational conditions, such as active waste dumping areas, inadequate soil cover, or unmanaged leachate zones, in driving disproportionate CH4 releases.

Beyond plume intensity, persistence analysis revealed that sites with stronger average emissions also tended to show higher recurrence across overpasses. For example, Brasília, Marituba, and Manaus were detected during nearly every available observation (≥100% persistence for the period with sufficient sampling), whereas weaker sites such as Palmas and Teresina 2 exhibited only sporadic detections. This persistence–emission link suggests that the most problematic sites are not only extreme in magnitude but also structurally consistent CH4 sources, likely reflecting chronic management deficiencies. Conversely, intermittent detections at smaller landfills could represent operational variability, meteorological masking, or episodic anaerobic hotspots. These distinctions are crucial for mitigation strategies, as persistent super-emitters may require long-term infrastructure upgrades, while episodic emitters may be more amenable to targeted operational changes.

The disproportionate role of super-emitters has critical implications for Brazil’s CH4 inventory and mitigation strategies. Current bottom-up estimates of waste-sector CH4 emissions often assume uniformity in landfill activity, potentially underestimating the role of a few dominant facilities. Our results suggest that targeted monitoring and mitigation at a handful of high-emitting landfills could yield significant reductions in regional CH4 fluxes. Our findings raise the possibility that national greenhouse gas inventories may underestimate landfill emissions, a pattern demonstrated in recent satellite-based studies across multiple regions [19,20]. In Brazil, where the waste sector remains a major potential contributor to total CH4 fluxes [30,31], systematic underrepresentation of landfill emissions could lead to significant biases in the national CH4 budget. Targeted monitoring of high-emitting facilities therefore represents a cost-effective strategy to reduce these uncertainties.

Our use of spaceborne imaging spectrometers provides new insights into landfill emissions at regional scale, yet methodological considerations remain. First, sensor detection thresholds and revisit frequencies can influence CH4 plume detectability. Recent advances in hyperspectral instruments such as EMIT and Carbon Mapper offer improved sensitivity for attributing CH4 to specific facilities [10,34,36]. Continued integration of satellite, airborne, and ground-based approaches will be essential to refine emission estimates and validate spaceborne retrievals. Second, our dataset remains constrained by the limited number of overpasses, particularly for sites with only one or two detections, where episodic emissions may bias interpretation. In addition, the Amazon and the Cerrado transition region are cloudy much of the time, which reduces the number of valid satellite overpasses. Third, the adaptive thresholding algorithm, while robust to varying backgrounds, may under- or over-estimate plume extents in highly heterogeneous environments. The adaptive thresholding scheme presented here is not intended as a replacement for full physics-based algorithms (e.g., IME) or machine-learning classification models. Instead, it provides a computationally simple and explainable method tuned to hyperspectral sensors such as EMIT and Tanager-1, with particular utility for regional landfill assessments. Its main limitation is that it has not been benchmarked against cross-sensor or multi-method frameworks, which would require a dedicated algorithm evaluation study.

Although the dataset primarily consists of MSW landfill emissions, it also includes one coal-mine plume and one plume from an undetermined sector. The adaptive thresholding algorithm successfully delineated plume regions in both cases, indicating that the approach is not inherently restricted to landfill-type morphology. Nonetheless, these represent isolated examples, and no systematic cross-sector validation is attempted. As emission characteristics can vary markedly across industries, especially for low-intensity or diffuse plumes, sensitivity may be limited by the retrieval signal-to-noise ratio. Comprehensive evaluation across broader source types lies outside the scope of this study.

Nevertheless, the consistency of our results across multiple sites, the strong statistical fit to a log-normal distribution, and the alignment with known landfill management practices lend confidence to our conclusions.

The identification of persistent landfill super-emitters in Brazil highlights urgent opportunities for mitigation. Given that a limited number of facilities account for the bulk of observed emissions, targeted interventions could provide rapid and cost-effective reduc tions, consistent with global CH4 abatement priorities [5,6]. Beyond climate impacts, landfill emissions also pose significant risks for air quality, public health, and local environmental justice [9]. Strengthening monitoring frameworks, improving waste treatment infrastructure, and integrating satellite observations into regulatory processes represent critical steps toward aligning Brazil’s waste sector with national and international climate goals.

This study demonstrates the value of high-resolution satellite spectroscopy (EMIT, Tanager-1) for monitoring waste-sector CH4 emissions in Brazil, yet it also underscores the need for sustained and expanded efforts. While the focus of this work is on characterizing CH4 enhancements detected over north-central Brazil, a systematic international comparison is outside the scope of this study. Nevertheless, the observed plume strengths in this region are broadly consistent with patterns of CH4 emissions and super-emitter behavior reported in other landfill-dominated CH4 studies worldwide [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Future research should aim to (i) integrate plume detections with local meteorological data to derive quantitative fluxes; (ii) couple remote sensing with ground-based and airborne campaigns to validate retrievals; (iii) expand coverage to include currently unobserved states (e.g., Acre, Rondônia, Maranhão); and (iv) explore the effectiveness of landfill management interventions through repeated monitoring. In addition, linking CH4 plume data with socio-economic indicators such as population, waste generation rates, landfill design, and policy enforcement could provide actionable insights for municipal and federal decision-makers. Together, these proposed extensions—regional expansion, integration with meteorology, ground-based validation, and sector-wide application—represent the intended next phase of this research program and outline a clear path for advancing CH4 super-emitter detection and characterization in Brazil and beyond.

In summary, our findings confirm that CH4 emissions from solid waste facilities in northern and central Brazil are characterized by strong spatial heterogeneity, a heavy-tailed distribution, and the dominance of a small number of persistent super-emitters. The integration of Carbon Mapper detections with adaptive plume quantification provides a novel lens on landfill CH4 emissions in Brazil, revealing both the scale of the problem and potential high-impact mitigation opportunities. By prioritizing action at the most persistent and extreme sites, Brazil could achieve substantial CH4 reductions, contributing both to local air quality improvements and to global climate mitigation goals.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a regional satellite-based assessment of CH4 emissions from landfills and related point sources across northern and central Brazil using Carbon Mapper data from the EMIT and Tanager-1 hyperspectral sensors. We identified pronounced spatial contrasts in plume strength, persistence, and recurrence across 16 sites in nine states. A small number of persistent super-emitters—notably the landfills in Brasília and Marituba—dominate regional emissions, with plume strengths exceeding 108 ppm·m3, whereas most other sites exhibited weaker and sporadic emissions (106–107 ppm·m3). This heavy-tailed distribution indicates that a limited number of high-impact sources account for a disproportionate share of total CH4 output.

Emission persistence was associated with magnitude, suggesting that chronic operational deficiencies, such as poor waste cover or inadequate leachate control, sustain long-term CH4 release. In contrast, smaller or partially managed facilities showed intermittent emissions more influenced by operational and meteorological variability. These findings imply that targeted mitigation at a few major landfills could deliver substantial climate benefits.

From a policy perspective, the results highlight the potential of satellite-based monitoring to support Brazil’s CH4 reduction pledges under the Paris Agreement and the Global Methane Pledge. Integrating such observations with municipal waste management systems can enhance mitigation efficiency and co-benefits for local air quality and public health.

Methodologically, this work demonstrates the value of high-resolution imaging spectroscopy for detecting and characterizing CH4 super-emitters, offering insights unattainable from coarser satellite products or inventory-based approaches. While limited by site coverage and the absence of atmospheric transport modeling, the consistency of detections across instruments and dates supports the robustness of the results.

Looking ahead, extending this framework to additional Brazilian states and other CH4-emitting sectors—such as agriculture, fossil fuels, and coal mining—will be key to building a comprehensive national CH4 emission map. Coupling these observations with meteorological and in situ data will further improve flux quantification and source attribution. By pinpointing where and when the strongest emissions occur, this study provides a foundation for regionally relevant and globally significant mitigation strategies. Moreover, the approach can be readily applied in data-scarce regions, facilitating CH4 super-emitter detection where ground-based information is limited.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rs17243973/s1, Figure S1: Temporal distribution of all studied sites as a function of strength; Figure S2: Density comparison of strength fits; Figure S3: Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF); Figure S4: Quantile–Quantile (QQ) plot; Figure S5: Log-log Complementary Cumulative Distribution Function (CCDF); Figure S6: Histogram of strength with log-normal fit. The Supplementary files also include the codes used for the adaptive thresholding and super-emitter fraction calculations (with accompanying README files), as well as the CSV file containing the algorithm outputs. A complete list of the satellite images analyzed in this study is provided in the included CSV file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis, G.I.C., V.F.V.V.d.M. and J.C.J.; software, resources, and data curation, G.I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.I.C.; writing—review and editing, G.I.C., V.F.V.V.d.M. and J.C.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All CH4 concentration plumes data employed in this study can be downloaded from Carbon Mapper Open Data Portal (https://carbonmapper.org/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fernández-Amador, O.; Francois, J.F.; Oberdabernig, D.A.; Tomberger, P. The methane footprint of nations: Stylized facts from a global panel dataset. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 170, 106528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, K.A.; Unger, C.; Walderdorff, L.; Butler, T. Beyond CO2 equivalence: The impacts of methane on climate, ecosystems, and health. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 134, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folberth, G.; O’Connor, F.; Jones, C.; Gedney, N.; Wiltshire, A. Drivers of persistent changes in the global methane cycle under aggressive mitigation action. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.F.; Middelburg, J.J.; Röckmann, T.; Aerts, R.; Blauw, L.G.; Egger, M.; Jetten, M.S.M.; de Jong, A.E.E.; Meisel, O.H.; Rasigraf, O.; et al. Methane Feedbacks to the Global Climate System in a Warmer World. Rev. Geophys. 2018, 56, 207–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yin, D.; Sun, Z.; Ye, B.; Zhou, N. Global trend of methane abatement inventions and widening mismatch with methane emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.B.; Salas, S.D.; Chen, Q.; Allen, D.T. Prioritize rapidly scalable methane reductions in efforts to mitigate climate change. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 2789–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, C.; Martín, J.G.; Johansson, D.J.A.; Sterner, T. The social cost of methane. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniaszek, Z.; Griffiths, P.T.; Folberth, G.A.; O’Connor, F.M.; Abraham, N.L.; Archibald, A.T. The role of future anthropogenic methane emissions in air quality and climate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoye, B.J.; Olagbemideu, P.T.; Ogunnusi, T.A.; Akpor, O.B. Environmental and Human Health Impacts of Municipal Solid Wastes Landfill Emissions: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 5th International Conference on Electro-Computing Technologies for Humanity (NIGERCON), Ado Ekiti, Nigeria, 26–28 November 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, A.K.; Green, R.O.; Thompson, D.R.; Brodrick, P.G.; Chapman, J.W.; Elder, C.D.; Irakulis-Loitxate, I.; Cusworth, D.H.; Ayasse, A.K.; Duren, R.M.; et al. Attribution of individual methane and carbon dioxide emission sources using EMIT observations from space. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, M.; Lou, Z.; He, H.; Guo, Y.; Pi, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, K.; Fei, X. Methane emissions from landfills differentially underestimated worldwide. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Peng, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Q. Quantification of methane emissions from municipal solid waste landfills in China during the past decade. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riman, H.S.; Adie, G.U.; Anake, W.U.; Ana, G.R.E.E. Seasonal methane emission from municipal solid waste disposal sites in Lagos, Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiehbadroudinezhad, M.; Merabet, A.; Hosseinzadeh-Bandbafha, H. Landfill source of greenhouse gas emission. In Advances and Technology Development in Greenhouse Gases: Emission, Capture and Conversion; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Tirpude, A.; Mathew, N.; Arfin, T. Gaseous Emissions from Solid Waste Disposal. In Waste Derived Carbon Nanomaterials; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Volume 1, pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Krautwurst, S.; Gerilowski, K.; Jonsson, H.H.; Thompson, D.R.; Kolyer, R.W.; Iraci, L.T.; Thorpe, A.K.; Horstjann, M.; Eastwood, M.; Leifer, I.; et al. Methane emissions from a Californian landfill, determined from airborne remote sensing and in situ measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 3429–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusworth, D.H.; Duren, R.M.; Thorpe, A.K.; Tseng, E.; Thompson, D.; Guha, A.; Newman, S.; Foster, K.T.; Miller, C.E. Using remote sensing to detect, validate, and quantify methane emissions from California solid waste operations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 054012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duren, R.M.; Thorpe, A.K.; Foster, K.T.; Rafiq, T.; Hopkins, F.M.; Yadav, V.; Bue, B.D.; Thompson, D.R.; Conley, S.; Colombi, N.K.; et al. California’s methane super-emitters. Nature 2019, 575, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Lou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hussain, A.; Zhan, L.; Yin, K.; Fang, M.; Fei, X. Underestimated Methane Emissions from Solid Waste Disposal Sites Reveal Missed Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Opportunities. Engineering 2024, 36, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.J.; Thoma, E.D.; Bryant, A.; Brantley, H.; MacDonald, M.; Green, R.; Thorneloe, S. A High-Resolution Satellite Survey of Methane Emissions from 60 North American Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15080–15091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpelli, T.R.; Cusworth, D.H.; Duren, R.M.; Kim, J.; Heckler, J.; Asner, G.P.; Thoma, E.; Krause, M.J.; Heins, D.; Thorneloe, S. Investigating Major Sources of Methane Emissions at US Landfills. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21545–21556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusworth, D.H.; Duren, R.M.; Ayasse, A.K.; Jiorle, R.; Howell, K.; Aubrey, A.; Green, R.O.; Eastwood, M.L.; Chapman, J.W.; Thorpe, A.K.; et al. Quantifying methane emissions from United States landfills. Science 2024, 383, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Caldow, C.; Broquet, G.; Shah, A.; Laurent, O.; Yver-Kwok, C.; Ars, S.; Defratyka, S.; Gichuki, S.W.; Lienhardt, L.; et al. Detection and long-term quantification of methane emissions from an active landfill. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 1229–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lei, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of Methane Emission from Msw Landfills in China, India, and the U.S. From Space Using a Two-Tier Approach. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, J.; Smith, S.J.; Yu, S.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, M.; Williams, J.; Cheng, X.; Dule, A.A.; Li, W.; et al. United States and China Anthropogenic Methane Emissions: A Review of Uncertainties and Collaborative Opportunities. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2024EF005298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, C.; Thorpe, A.K.; Thompson, D.R.; Hulley, G.; Kort, E.A.; Vance, N.; Borchardt, J.; Krings, T.; Gerilowski, K.; Sweeney, C.; et al. Airborne methane remote measurements reveal heavy-tail flux distribution in Four Corners region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9734–9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavala-Araiza, D.; Alvarez, R.A.; Lyon, D.R.; Allen, D.T.; Marchese, A.J.; Zimmerle, D.J.; Hamburg, S.P. Super-emitters in natural gas infrastructure are caused by abnormal process conditions. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusworth, D.; Thorpe, A.; Ayasse, A.; Stepp, D.; Heckler, J.; Asner, G.; Miller, C.; Chapman, J.; Eastwood, M.; Green, R.; et al. Strong methane point sources contribute a disproportionate fraction of total emissions across multiple basins in the U.S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2202338119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Martinez, A.; Poulter, B.; Zhang, Z.; Raymond, P.A.; Regnier, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Patra, P.K.; Bousquet, P.; et al. Global methane budget 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1873–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, F.A.M.; Ismail, K.A.R.; Castañeda-Ayarza, J.A. Municipal solid waste treatment in Brazil: A comprehensive review. Energy Nexus 2023, 11, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadario, N.; Gabriel Filho, L.R.A.; Cremasco, C.P.; Santos, F.A.; dos Rizk, M.C.; Mollo Neto, M. Waste-to-Energy Recovery from Municipal Solid Waste: Global Scenario and Prospects of Mass Burning Technology in Brazil. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, F.A.M.; Ismail, K.A.R. Analysis of the potential of municipal solid waste in Brazil. Environ. Dev. 2012, 4, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Version 3.34. Geographic Information System. Open-Source Geospatial Foundation Project 2024. Available online: https://www.qgis.org/en/site/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Duren, R.; Cusworth, D.; Ayasse, A.; Howell, K.; Diamond, A.; Scarpelli, T.; Kim, J.; O’neill, K.; Lai-Norling, J.; Thorpe, A.; et al. The Carbon Mapper emissions monitoring system. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J.; Varon, D.J.; Cusworth, D.H.; Dennison, P.E.; Frankenberg, C.; Gautam, R.; Guanter, L.; Kelley, J.; McKeever, J.; Ott, L.E.; et al. Quantifying methane emissions from the global scale down to point sources using satellite observations of atmospheric methane. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 9617–9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.R.; Green, R.O.; Bradley, C.; Brodrick, P.G.; Mahowald, N.; Dor, E.B.; Bennett, M.; Bernas, M.; Carmon, N.; Chadwick, K.D.; et al. On-orbit calibration and performance of the EMIT imaging spectrometer. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 303, 113986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estimativas da População Residente Para os Municípios e Para as Unidades da Federação IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9103-estimativas-de-populacao.html (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Biomas e Sistema Costeiro-Marinho do Brasil, IBGE. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/apps/biomas/#/home (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Delignette-Muller, M.L.; Dutang, C. fitdistrplus: An R Package for Fitting Distributions. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 64, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]