Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency and the Impacts of Drought Legacy on the Loess Plateau, China, Since the Onset of the Grain for Green Project

Highlights

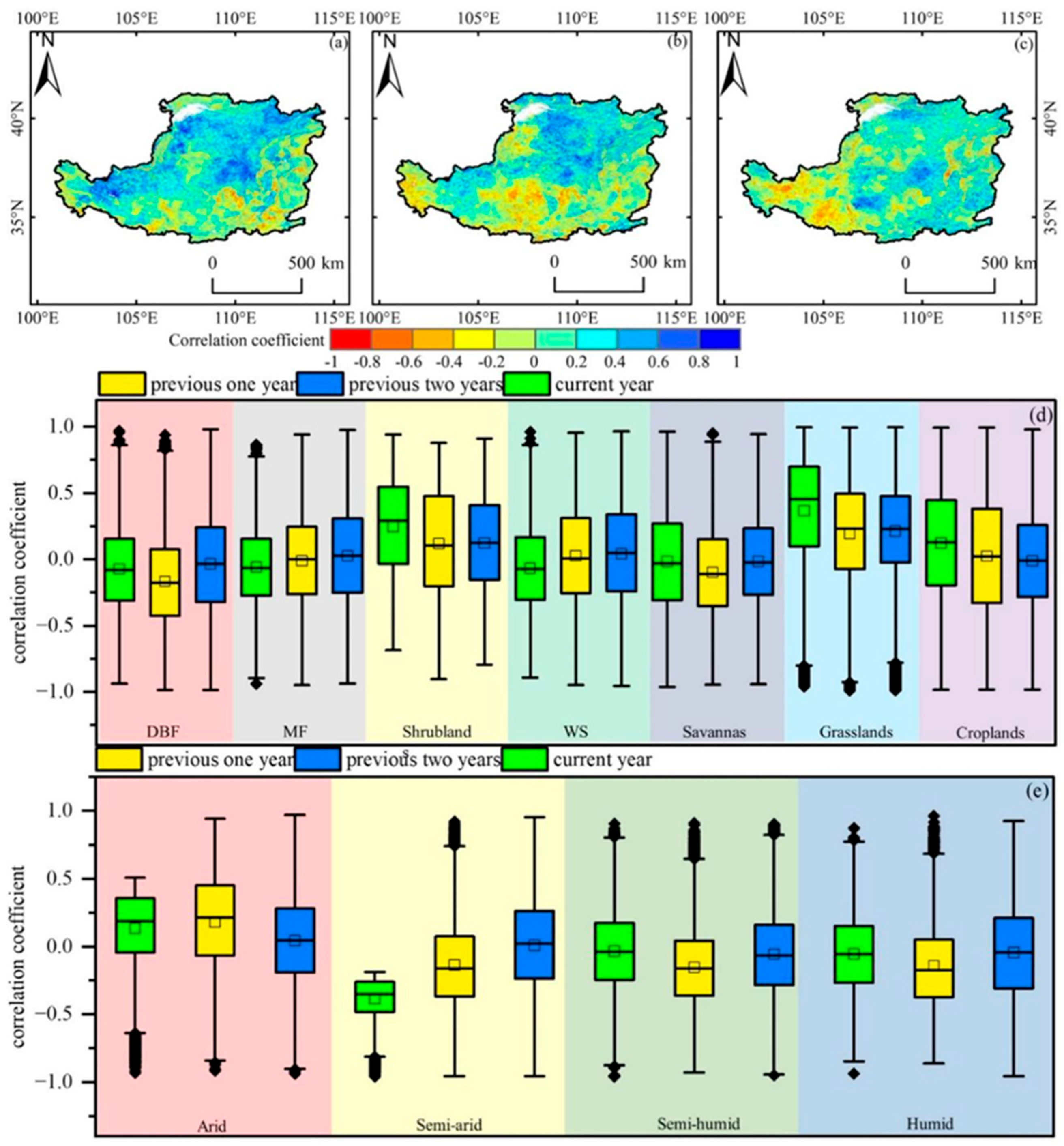

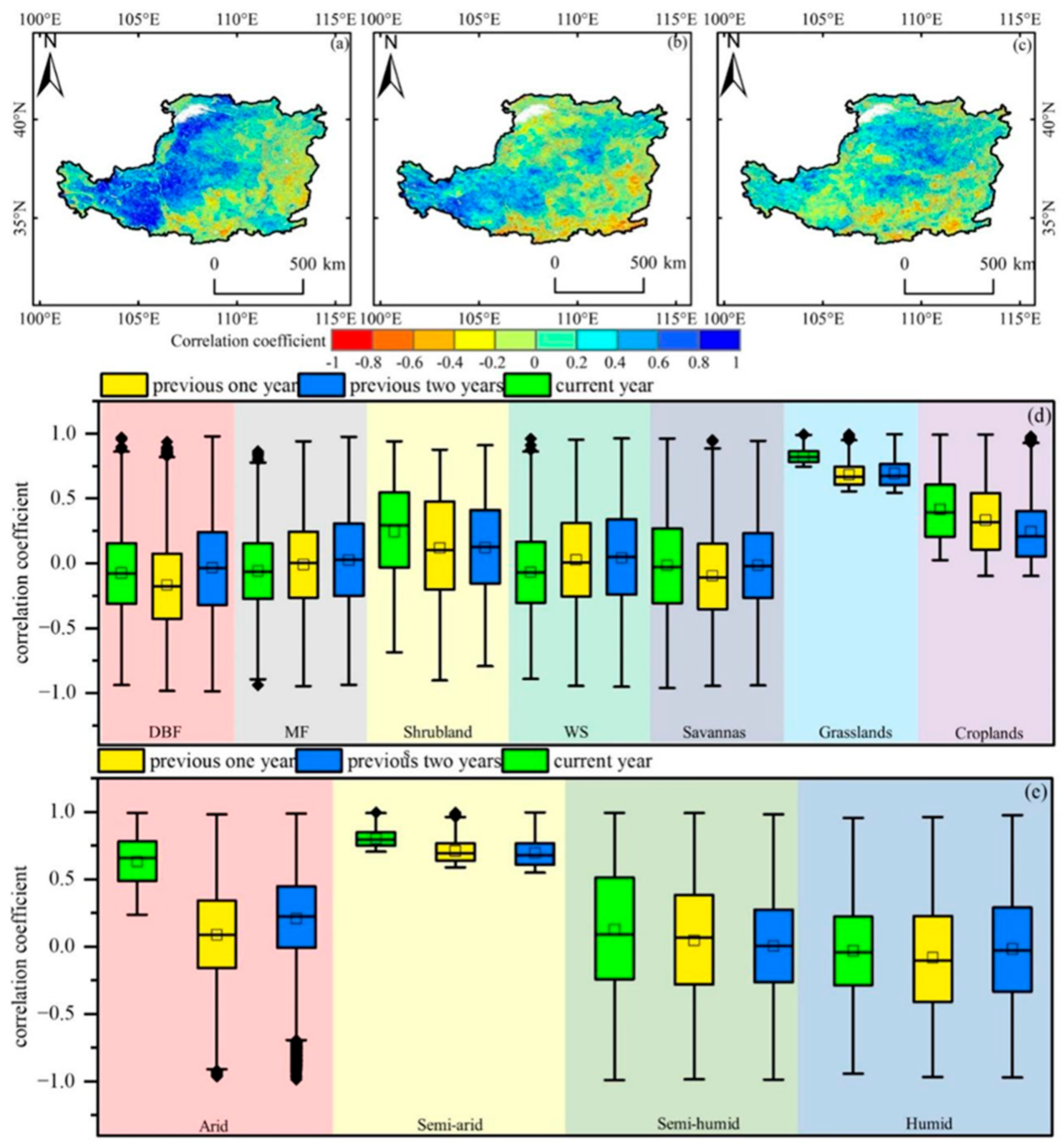

- Ecosystem water use efficiency (eWUE) exhibits a pronounced two-year legacy effect; the correlation with the lagged drought index two years prior is stronger than the correlation with the current year’s index.

- A widespread positive correlation between eWUE and the drought index across the LP suggests a robust ecosystem adaptation strategy that enhances water use efficiency under high moisture limitation.

- The pronounced drought legacy necessitates a paradigm shift toward multi-year strategic water resource planning in semiarid land management to buffer the effects of future persistent droughts.

- The diverse eWUE responses across vegetation types require adopting “right tree, right place” policies to optimize ecological restoration, preventing the exacerbation of soil drying and water resource pressure.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Field

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. eWUE

2.4. Temperature–Vegetation–Precipitation Drought Index (TVPDI)

2.5. Legacy Effects of Early Drought on eWUE

2.6. Trend Analysis

3. Results

3.1. GPP/ET/eWUE

3.2. Temporal and Spatial Evolution of TVPDI

3.3. Response of eWUE to TVPDI Changes

3.4. Hysteresis Effect of Drought on eWUE

3.4.1. Correlation Between eWUE and TVPDI and Legacy Effects of Drought from 2001 to 2012

3.4.2. Correlation Between eWUE and TVPDI and Legacy Effects of Drought Between 2013 and 2020

4. Discussion

4.1. The Rationality of the Drought Level Thresholds of TVPDI

4.2. Temporal and Spatial Heterogeneity of eWUE

4.3. eWUE Response to Drought

4.4. Drought Legacy Effect of eWUE

4.5. Understanding and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lavergne, A.; Graven, H.; De Kauwe, M.G.; Keenan, T.F.; Medlyn, B.E.; Prentice, I.C. Observed and modelled historical trends in the water-use efficiency of plants and ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2242–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T.; Hou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wu, H.; Xie, B.; Qi, P.; Zhang, J. Vegetation in Arid Areas of the Loess Plateau Showed More Sensitivity of Water-Use Efficiency to Seasonal Drought. Forests 2022, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Pan, J.; Zhou, B.; Muhammad, T.; Zhou, C.; Li, Y. Micro-Nano bubble water oxygation: Synergistically improving irrigation water use efficiency, crop yield and quality. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, C. Ecosystem water use efficiency was enhanced by the implementation of forest conservation and restoration programs in China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.-J.; Wang, X.-P.; Zhao, C.-Y.; Zhang, X.-X. Responses of ecosystem water use efficiency to meteorological drought under different biomes and drought magnitudes in northern China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 278, 107660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Sun, S.; Yao, R.; Sun, P.; Li, M.; Bian, Y. Long-Term vegetation phenology changes and response to multi-scale meteorological drought on the Loess Plateau, China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, M.H.; Bulut, B.; Duzenli, E.; Amjad, M.; Yilmaz, M.T. Global spatiotemporal consistency between meteorological and soil moisture drought indices. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 316, 108848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.R.; Mahmoudi, M.R.; Moghimi, M.M. Determining the most appropriate drought index using the random forest algorithm with an emphasis on agricultural drought. Nat. Hazards 2022, 115, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Aryal, S.K.; Ha, T.T.V.; Baig, F.; Naz, F. A composite drought index developed for detecting large-scale drought characteristics. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, X.; Tian, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Aryal, S. Drought index revisited to assess its response to vegetation in different agro-climatic zones. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, A.K.; Ramadas, M.; Panda, R.K. Changes in drought characteristics based on rainfall pattern drought index and the CMIP6 multi-model ensemble. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 266, 107568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wei, F.; Xiao, P.; Shen, Z.; Lv, X.; Shi, Y. Determining the Contributions of Vegetation and Climate Change to Ecosystem WUE Variation over the Last Two Decades on the Loess Plateau, China. Forests 2021, 12, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadez, V.; Pilloni, R.; Grondin, A.; Hajjarpoor, A.; Belhouchette, H.; Brouziyne, Y.; Chehbouni, G.; Kharrou, M.H.; Zitouna-Chebbi, R.; Mekki, I. Water Use Efficiency (WUE) across scales: From genes to landscape. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 4770–4788. erad052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Li, J. Conservation tillage improves soil water storage, spring maize (Zea mays L.) yield and WUE in two types of seasonal rainfall distributions. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Wen, Z.; Khalifa, M.; Zheng, C.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z. Assessing the impacts of drought on net primary productivity of global land biomes in different climate zones. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Shan, N.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, F.; Liu, W.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Q. Separating the effects of climate change and human activity on water use efficiency over the Beijing-Tianjin Sand Source Region of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Ju, W.; Shen, S.; Wang, S.; Yu, G.; Han, S. How recent climate change influences water use efficiency in East Asia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2014, 116, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Ding, J.; Welp, M.; Huang, S.; Liu, B. Assessing the Response of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency to Drought During and after Drought Events across Central Asia. Sensors 2020, 20, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Luo, J.; Li, X.; Ding, Z.; Xie, J. Potential of MODIS data to track the variability in ecosystem water-use efficiency of temperate deciduous forests. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 91, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A.; Inatomi, M. Water-Use Efficiency of the Terrestrial Biosphere: A Model Analysis Focusing on Interactions between the Global Carbon and Water Cycles. J. Hydrometeorol. 2012, 13, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X. Spatial–Temporal dynamics of gross primary productivity, evapotranspiration, and water-use efficiency in the terrestrial ecosystems of the Yangtze River Delta region and their relations to climatic variables. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 2654–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, A.; Yang, L.; Peng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, C. Spatial characteristics of the rainfall induced landslides in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2020, 26, 2462–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yao, S.; Yang, W.; Sun, Q. Effects and contributions of meteorological drought on agricultural drought under different climatic zones and vegetation types in Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, Y. Contrasting trends in water use efficiency of the alpine grassland in Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tang, X.; Zheng, C.; Gu, Q.; Wei, J.; Ma, M. Differences in ecosystem water-use efficiency among the typical croplands. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 209, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Du, J.; Tian, Z.; Xu, W.; Deng, J.; Han, G. Study on the Application of Seismic-Based Casing Deformation Prediction Technology in Xinjiang Oil Field. In Proceedings of the 2021 China-Europe International Conference on Pipelines and Trenchless Technology, Tianjin, China, 17–19 December 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, X.; Luo, H.; Gao, S.; Li, Z.; Cao, L. Diverse responses of different structured forest to drought in Southwest China through remotely sensed data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 69, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, S. Effects of Multi-Temporal Scale Drought on Vegetation Dynamics in Inner Mongolia from 1982 to 2015, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Meng, Z.; Fu, Y. Drought and water-use efficiency are dominant environmental factors affecting greenness in the Yellow River Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Zou, B.; Nie, Y.; Ye, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, S. Land use and cover change (LUCC) impacts on Earth’s eco-environments: Research progress and prospects. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 71, 1418–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shi, M.; Huang, J. Estimating loess plateau average annual precipitation with multiple linear regression kriging and geographically weighted regression kriging. Water 2016, 8, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Sun, F.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Cui, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Du, B. Response of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency to Drought over China during 1982–2015: Spatiotemporal Variability and Resilience. Forests 2019, 10, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, A.; Gao, M.; Slette, I.J.; Piao, S. The impact of the 2009/2010 drought on vegetation growth and terrestrial carbon balance in Southwest China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 269, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Ciais, P.; Papale, D.; Valentini, R.; Running, S.; Viovy, N.; Cramer, W.; Granier, A.; Ogée, J.; Allard, V. Reduction of ecosystem productivity and respiration during the European summer 2003 climate anomaly: A joint flux tower, remote sensing and modelling analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2007, 13, 634–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Yao, F.; Guo, H. The potential of remote sensing-based models on global water-use efficiency estimation: An evaluation and intercomparison of an ecosystem model (BESS) and algorithm (MODIS) using site level and upscaled eddy covariance data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 287, 107959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; He, B.; Han, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. A global examination of the response of ecosystem water-use efficiency to drought based on MODIS data. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601–602, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wang, D.; Cui, X.; Yao, X.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, B. Distribution and Driving Force of Water Use Efficiency under Vegetation Restoration on the Loess Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Du, L.; Meng, C.; Dan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, L. Characteristics of water use efficiency in terrestrial ecosystems and its influence factors in Ningxia Province. Acta Ecol. Sin 2019, 39, 9068–9078. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Yin, H.; Li, W.; Zhao, S. Seasonal Variations of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency and Their Responses to Climate Factors in Inner Mongolia of China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Wu, K.; Lin, Q. How to construct a coordinated ecological network at different levels: A case from Ningbo city, China. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Shi, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Xie, B.; Zhou, J.; Li, C. Regional-scale assessment of environmental vulnerability in an arid inland basin. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 109, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Lu, J.; Chen, X. A novel comprehensive agricultural drought index reflecting time lag of soil moisture to meteorology: A case study in the Yangtze River basin, China. Catena 2022, 209, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, T. Assessment of the spatiotemporal characteristics of vegetation water use efficiency in response to drought in Inner Mongolia, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 6345–6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: The standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, L.; Xie, B.; Zhou, J.; Li, C. Comparative evaluation of drought indices for monitoring drought based on remote sensing data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 20408–20425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, W.; Liu, T.; Lu, D.; Wang, J.; Yan, P.; Xie, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H. Construction of Temperature-Vegetation-Precipitation Dryness Index (TVPDI) and Dry–Wet Condition Monitoring Across China. Int. J. Climatol. 2025, 45, e70025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Yan, P.; Xie, B.; Zhou, J.; Liu, T.; Lu, D. The response of global terrestrial water storage to drought based on multiple climate scenarios. Atmos. Res. 2024, 303, 107331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiao, W.; Zeng, X.; Xing, X.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Hong, Y. Drought monitoring based on a new combined remote sensing index across the transitional area between humid and arid regions in China. Atmos. Res. 2021, 264, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.J.; Wang, X.P.; Zhao, C.Y.; Yang, X.M. Assessing the response of vegetation photosynthesis to meteorological drought across northern China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 32, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleverly, J.; Eamus, D.; Van Gorsel, E.; Chen, C.; Rumman, R.; Luo, Q.; Coupe, N.R.; Li, L.; Kljun, N.; Faux, R. Productivity and evapotranspiration of two contrasting semiarid ecosystems following the 2011 global carbon land sink anomaly. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016, 220, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yin, Q.; Zhao, T.; Chen, K.; Qian, L.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Zhang, B. Detecting ecosystem water use efficiency responses to drought from long-term remote sensing data. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, G.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fu, B. Ecosystem water use efficiency and carbon use efficiency respond oppositely to vegetation greening in China’s Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 964, 178575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Bai, Y.; Xun, L.; Zhang, S.; Cao, D.; Wang, J. The ratio of transpiration to evapotranspiration dominates ecosystem water use efficiency response to drought. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 363, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Yang, X.; Bai, L.; Sun, Q. The monitoring and analysis of the coastal lowland subsidence in the southern Hangzhou Bay with an advanced time-series InSAR method. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2017, 36, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiu, J.; Leng, G.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Fan, Y.; Luo, J. The potential utility of satellite soil moisture retrievals for detecting irrigation patterns in China. Water 2018, 10, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, G. Spatial variation in sediment connectivity of small watershed along a regional transect on the Loess Plateau. Catena 2022, 217, 106473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Vulnerability assessment and its driving forces in terms of NDVI and GPP over the Loess Plateau, China. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2022, 125, 103106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Lai, Q.; Zhang, J.; Bao, Y.; Lusi, A.; Ma, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, F. Spatiotemporal drought variability on the Mongolian Plateau from 1980–2014 based on the SPEI-PM, intensity analysis and Hurst exponent. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X. Unrevealing past and future vegetation restoration on the Loess Plateau and its impact on terrestrial water storage. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 129021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Hu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wu, G.; Feng, X.; Chen, R.; Hao, G. Shifts in ecosystem water use efficiency on China’s loess plateau caused by the interaction of climatic and biotic factors over 1985–2015. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 291, 108100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Gu, F.; Mei, X.; Hao, W.; Li, H.; Gong, D.; Li, X. Light and water use efficiency as influenced by clouds and/or aerosols in a rainfed spring maize cropland on the loess plateau. Crop Sci. 2018, 58, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Duan, Y.; Wang, L.; Kang, D.; Awasthi, M.K.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Seasonal variation of net ecosystem CO2 exchange and its influencing factors in an apple orchard in the Loess Plateau. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 43452–43465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eamus, D.; Cleverly, J.; Boulain, N.; Grant, N.; Faux, R.; Villalobos-Vega, R. Carbon and water fluxes in an arid-zone Acacia savanna woodland: An analyses of seasonal patterns and responses to rainfall events. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 182, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Glidden, S.; Grogan, D.S.; Li, X.; Cheng, Y.; Frolking, S. Modeling impacts of management on farmland soil carbon dynamics along a climate gradient in Northwest China during 1981–2000. Ecol. Model. 2015, 312, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, G.; Brunsell, N.A.; Moraes, E.C.; Shimabukuro, Y.E.; Bertani, G.; dos Santos, T.V.; Aragao, L.E.O.C. Evaluation of MODIS-based estimates of water-use efficiency in Amazonia. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 5291–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Jianjun, Z.; Guo, X.; Tong, S. Estimation of water-use efficiency based on satellite for the typical croplands. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 220533–220541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z. A new indicator of ecosystem water use efficiency based on surface soil moisture retrieved from remote sensing. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 75, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ding, Z.; Wu, C.; Song, L.; Ma, M.; Yu, P.; Lu, B.; Tang, X. Divergent responses of ecosystem water-use efficiency to extreme seasonal droughts in Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Cabello, D.; Tomás-Burguera, M.; Martín-Hernández, N.; Beguería, S.; Azorin-Molina, C.; El Kenawy, A. Drought variability and land degradation in semiarid regions: Assessment using remote sensing data and drought indices (1982–2011). Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4391–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yan, F.; Yu, P.; Man, W.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; Tang, X. Restored vegetation is more resistant to extreme drought events than natural vegetation in Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.; Law, B.E.; Thomas, C.K.; Johnson, B.G. The influence of hydrological variability on inherent water use efficiency in forests of contrasting composition, age, and precipitation regimes in the Pacific Northwest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 249, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Su, X.; Singh, V.P.; Zhang, G. A novel index for ecological drought monitoring based on ecological water deficit. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horion, S.; Ivits, E.; De Keersmaecker, W.; Tagesson, T.; Vogt, J.; Fensholt, R. Mapping European ecosystem change types in response to land-use change, extreme climate events, and land degradation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, N.; Biswas, A.; Zou, Y.; Meng, Q.; Liu, F. The lagged effect and impact of soil moisture drought on terrestrial ecosystem water use efficiency. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, J.; He, W.; Yong, Z.; Wang, X. Responses of the Remote Sensing Drought Index with Soil Information to Meteorological and Agricultural Droughts in Southeastern Tibet. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Y.; Ma, W.T.; Yu, Y.Z.; Fang, K.; Yang, Y.; Tcherkez, G.; Adams, M.A. Overestimated gains in water-use efficiency by global forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4923–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Yu, K.-X.; Li, Z.-B.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Wang, A.-N.; Ma, L.; Xu, G.-C.; Zhang, X. Temporal and spatial variation of rainfall erosivity in the Loess Plateau of China and its impact on sediment load. Catena 2022, 210, 105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TVPDI Values | Type |

|---|---|

| 0–0.5 | No Drought |

| 0.5–0.6 | Mild Drought |

| 0.6–0.7 | Moderate Drought |

| 0.7–0.8 | Severe Drought |

| 0.8–1 | Extreme Drought |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, X.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Bian, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, S. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency and the Impacts of Drought Legacy on the Loess Plateau, China, Since the Onset of the Grain for Green Project. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3980. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243980

Bao X, Wang W, Li X, Li Z, Bian C, Wang H, Wang S. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency and the Impacts of Drought Legacy on the Loess Plateau, China, Since the Onset of the Grain for Green Project. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3980. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243980

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Xingwei, Wen Wang, Xiaodong Li, Zhen Li, Chenlong Bian, Hongzhou Wang, and Sinan Wang. 2025. "Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency and the Impacts of Drought Legacy on the Loess Plateau, China, Since the Onset of the Grain for Green Project" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3980. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243980

APA StyleBao, X., Wang, W., Li, X., Li, Z., Bian, C., Wang, H., & Wang, S. (2025). Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency and the Impacts of Drought Legacy on the Loess Plateau, China, Since the Onset of the Grain for Green Project. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3980. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243980