Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Based on a three-year time-series UAV monitoring dataset, the study reconstructed the stand-scale diffusion process of pine wilt disease (PWD). The results revealed a dominant short-range spread (50% of events within 17.2 m) and a clear seasonal variation in mortality latency, which was shortest in spring and summer.

- A tree-level mortality risk prediction framework was developed using multi-source remote sensing features, with the random forest model achieving the best performance (AUC = 0.96) and accurately identifying 98.6% of high-risk trees.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The results highlight that localized diffusion dominates PWD transmission, suggesting a 28 m sanitation radius and enhanced surveillance within 141 m for effective control.

- The proposed risk prediction framework provides a practical basis for dynamic early warning and precision management of pine wilt disease at the individual-tree scale.

Abstract

Pine wilt disease (PWD) is one of the fastest-spreading invasive forest pathogens worldwide, causing rapid mortality of infected trees and posing a severe threat to global forest ecosystem security and carbon sink capacity. However, the spatial dynamics and diffusion characteristics of PWD at the stand scale remain poorly understood. In this study, we selected a typical epidemic area in Qingyuan County, Liaoning Province, China, as the study site. By integrating 23 phases of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) multispectral imagery, airborne LiDAR data, and field survey observations, we reconstructed the spatiotemporal diffusion process of PWD from 2023 to 2025 and developed a stand-scale, tree-level mortality risk prediction model. Our results show that 50% of transmission events occurred within 17.2 m, and the spatial autocorrelation range was approximately 28 m. The peak of the lethal latency period occurred 17 days after infection, with 40% of mortality events occurring within 11–22 days and 50% of infected trees dying within 40 days. The latency period was significantly shorter in spring and summer than in winter (). Among tree-level mortality risk prediction approaches, the random forest model performed best, improving overall accuracy by more than 15% compared with other methods and correctly identifying 98.6% of high-risk individuals. The distance to the nearest infected or dead tree was identified as the dominant predictor, followed by tree height and vegetation parameters reflecting host physiological status. This study reveals the spatial diffusion characteristics of PWD at the stand scale and proposes a tree-level risk prediction framework, providing a theoretical foundation and technical support for dynamic monitoring, early warning, and precision management of PWD.

1. Introduction

Biological invasions are intensifying globally and have become a critical threat to ecological security and sustainable development. Over the past 50 years, the cumulative global economic losses from biological invasions have exceeded USD 1.29 trillion, with an accelerating trend of approximately tripling every decade [1]. Pine wilt disease (PWD), caused by the pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus), a typical invasive forest disease, has been reported in dozens of countries since its first documentation in Japan in 1905 [2], with about 2300 confirmed cases worldwide [3]. In China, PWD outbreaks in highly susceptible areas have spread across 184,000 km2 [4], endangering up to 99 million tonnes of forest carbon storage, causing direct economic losses of over USD 1.11 billion, and leading to ecosystem service losses exceeding USD 6.29 billion [5]. These impacts pose a significant threat to forest ecosystem stability, regional carbon sink capacity, and the sustainable development of forestry in China and neighboring countries. Systematically analyzing the spatiotemporal spread and mortality dynamics of PWD, and clarifying its dispersal mechanisms, is crucial for refining theoretical frameworks for disease spread and prediction, as well as for developing effective control strategies to protect forest ecological security and carbon sink functions.

The lethal progression of PWD exhibits significant latency and concealment. The pathogenic nematodes block xylem vessels within the host tree [6], yet external symptoms—such as needle discoloration, wilting, and tree death—typically appear only after several weeks [7]. This characteristic limits the efficiency and timeliness of traditional monitoring methods, such as field surveys and molecular diagnostics [8], which struggle to support real-time tracking of disease spread and timely management decisions. Remote sensing technologies, with their advantages of large-scale coverage, temporal continuity, and non-invasive observation, have been widely adopted for PWD monitoring. Since the early 21st century, medium- and low-resolution satellite imagery, such as MODIS [9] and Landsat series [10], has shown potential for regional-scale forest health assessments. However, their spatial resolution and revisit frequency constraints—even when improved through image fusion—limit their ability to capture disease dynamics at the individual-tree level [11]. High-resolution satellites like GF-2 and WorldView-3 have improved target detection, achieving nearly 80% accuracy in open-canopy areas [12], but mixed-pixel effects in dense forest stands [13] hinder precise localization and tracking of infected trees. In contrast, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology provides centimeter-level high-resolution imagery. When combined with hyperspectral, LiDAR, and other sensor data [14] and machine learning models like YOLO [15], Mask R-CNN [16], and SVM [17], UAVs achieve individual-tree detection accuracies exceeding 85%, making them a standard tool for PWD surveillance by local forestry authorities [18].

Current research on unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based monitoring of pine wilt disease predominantly focuses on single-time-point “static classification.” The canopy infection process is typically divided into four stages—healthy, initial infection, early stage, late stage, and death—with hyperspectral data [19] and deep learning methods [20] achieving recognition accuracies exceeding 90% under controlled conditions. However, such studies [21] often rely on single-flight sampling, emphasizing spectral differences without continuous monitoring of individual tree conditions. Furthermore, many experiments depend on small-sample artificial inoculation in controlled environments [22], which limits their ability to characterize the continuous degradation processes in natural forest stands. Although recent multi-temporal approaches, such as Lee et al.’s use of time-series data to enhance detection accuracy [23], have improved sensitivity to feature differences, they still lack systematic modeling of physiological degradation trajectories and state transition mechanisms. Overall, existing UAV applications are primarily confined to multi-stage feature identification of diseased trees at single time points, falling short of addressing the needs for spatiotemporal disease progression analysis and regional spread early warning.

At different spatial scales, the spread of PWD primarily occurs through three major pathways: autonomous movement of nematodes within the xylem, dispersal via vector insect flight, and long-distance transportation of infected wood by human activities [24]. Macro-scale studies primarily construct models based on transmission mechanisms [25] and ecological adaptability [26]. However, both approaches rely excessively on the assumption of homogeneity in single explanatory factors, thereby raising concerns regarding the generalizability of their conclusions. For instance, outbreaks in Liaoning (2016) and Jilin (2021) have challenged this assumption, and recent research has revealed a “northward and westward expansion” trend in the spatial distribution of PWD across China [27], suggesting that conventional regional-scale models fail to capture the true evolutionary dynamics of the epidemic. The climate of Northeast China—characterized by prolonged, frigid winters, abundant snowfall, and a structurally complex forest mosaic—creates a transmission environment markedly different from that of traditional southern epidemic regions. Correspondingly, the spread dynamics of PWD in this region exhibit distinct features, including altered seasonal activity patterns and host-mortality processes. As demonstrated by Wang et al. (2023), populations of the pinewood nematode in Northeast China show greater cold tolerance than those in southern endemic zones, and newly infected host species have also been identified [28]. Together, these factors reveal region-specific ecological responses and transmission mechanisms, thereby necessitating analytical frameworks that differ from conventional southern-based or macro-scale suitability models [7].

At the stand scale, research has primarily focused on pathological mechanisms [29], vector insect ecology [30], host resistance [31], and control strategies [32]. These studies emphasize micro-level physiological processes or management practices but pay insufficient attention to the quantitative prediction of disease dispersal dynamics. A few studies [33] have employed individual-based models to simulate local spread within a 100 m range, capturing certain aggregation patterns; however, these models rely heavily on oversimplified assumptions—such as neglecting spatial heterogeneity and homogenizing vector feeding behavior—resulting in substantial deviations from field observations.To address these limitations, Tan et al. [34] utilized 12 temporal UAV image series acquired within a single year and estimated dispersal distances based on the nearest-neighbor relationships between newly infected and previously infected trees. Yet, this method essentially represents spatial density patterns rather than true transmission pathways or causal mechanisms. In summary, studies focusing on PWD dispersal characteristics and transmission pathways at the stand scale remain limited. There is an urgent need to develop novel modeling frameworks that integrate time-series remote sensing data with multi-source environmental variables to reconstruct transmission pathways at the individual-tree level, thereby improving early-warning precision and supporting targeted management of forest pest epidemics.

To this end, this study focuses on Qingyuan Manchu Autonomous County in Liaoning Province, a representative epidemic area of PWD, as the study region. Leveraging high-density, long-term multispectral UAV remote sensing imagery, we establish a monitoring and detection framework for PWD at the individual-tree scale. By extracting multi-source remote sensing features of infected tree canopies throughout the mortality process, we systematically characterize the spatial diffusion patterns and lethal dynamics of the disease. On this basis, we integrate multi-temporal vegetation indices, individual-tree structural attributes, and topographic–environmental variables to construct a spatiotemporal variable set driving PWD spread. Multiple machine learning models are then introduced to predict individual-tree mortality risk at the stand scale, thereby assessing their capability to identify transmission pathways and model dispersal dynamics across spatial domains.

This study addresses two fundamental scientific questions: (1) How does PWD spread over time and space at the stand scale? Do its transmission pathways exhibit identifiable structural characteristics, and what are the patterns of its spatial scale and anisotropy? (2) Based on key factors revealed by the transmission mechanisms, can a generalized individual-tree mortality risk prediction model be developed to characterize future spread trajectories? The outcomes of this research are expected to advance the development of high-temporal-resolution forest health monitoring systems and intelligent early-warning models, enhance the precision of monitoring and targeted control of invasive forest pests, and provide both theoretical foundations and data support for elucidating stand-scale transmission mechanisms and dynamic prediction of forest diseases.

2. Data and Study Area

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

The study area is located in Qingyuan Manchu Autonomous County, Liaoning Province, northeastern China (125°01′00″E, 42°08′30″N), situated within the northern low-mountain and hilly region of the Changbai Mountain range. The terrain is dominated by erosional–denudational mid- to low-altitude mountains, characterized by pronounced relief, dense valley networks, diverse slope aspects, and elevations ranging from approximately 300 to 450 m.The region has a temperate humid monsoon climate, featuring cold and dry winters and warm, humid summers. The mean annual temperature is about 5.5 °C, and annual precipitation ranges from 800 to 1000 mm, with most rainfall occurring between June and September. Forest vegetation is primarily composed of Pinus koraiensis plantations and mixed conifer–broadleaf stands. The dominant species include P. koraiensis, Larix gmelinii, Betula platyphylla, Acer mono, and Quercus mongolica, reflecting a typical pattern of artificial cultivation interspersed with near-natural secondary succession.

The primary biotic stress in the region is PWD, which spreads mainly through short-distance transmission within forest stands mediated by insect vectors, chiefly Monochamus saltuarius [35] and Monochamus alternatus [36]. PWD was first detected in the study area around 2017; it expanded gradually in 2018, when dead trees first appeared, and since 2019 the number of infected trees has increased sharply, marking the onset of a high-incidence outbreak phase.Local control efforts focus mainly on the removal of individual infected trees, involving selective felling and chipping of diseased individuals. In addition, tree stumps are sealed with wire-mesh enclosures to prevent further spread of the pathogen.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Sources

2.2.1. Field Survey

To obtain high-precision ground truth data for UAV image classification training and model validation, a total of twenty 10 m × 10 m sample plots were established within the study area in July 2023. These plots encompassed representative stand types and a full range of disease severity levels. A tree-by-tree field survey was conducted within each plot, recording diameter at breast height (DBH), health condition (e.g., needle discoloration, wilting symptoms), and disease stage (healthy, initial infection, early stage, late stage, or dead). The assignment of health condition and disease stage during the field survey was based on physiological symptoms directly observable at the tree level, including the proportion of needle discoloration (green → yellow → reddish-brown), the severity of needle wilting, the extent of crown defoliation, branch dieback, and the presence of dry or cracked bark. Spatial locations of individual trees were also documented. The survey additionally generated tree species classification data, which served as supplementary information on stand structure. These data were used for comparison with remote sensing classification results and for validating forest stand distribution across the study area. Spatial coordinates of individual trees and plot boundaries were acquired using a Trimble R8 GNSS receiver (Trimble Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA), achieving a positional accuracy better than 5 cm. Under dense canopy conditions, each observation point was measured in static mode for 10 min and repeated three times to obtain the mean value. All coordinates were georeferenced to the WGS 1984 coordinate system.

2.2.2. Remote Sensing Data Acquisition

The remote sensing dataset used in this study comprised multispectral imagery and airborne LiDAR point cloud data, which were employed for periodic monitoring of the core infestation zone of pine wilt disease. Detailed specifications of the sensors and acquisition parameters are provided in Table 1. Multispectral imagery was obtained using a DJI Mavic 3 Multispectral UAV (DJI, Shenzhen, China). Data collection was conducted from July 2023 to July 2025 during the vegetation growing season (April–October) [37], resulting in 23 temporal phases with an average revisit interval of approximately 15–20 days. The imagery covered an area of approximately 130 ha. To ensure the consistency and quality of the long-term multi-temporal dataset, several measures were implemented during data acquisition. Under dense canopy conditions, GNSS observations were collected in repeated static mode to reduce positioning errors. All UAV flights were conducted within narrow morning time windows under clear skies to minimize illumination differences across the 23 campaigns. A standardized lawn-mower flight pattern with bidirectional overlapping paths was adopted for all missions to ensure consistent spatial coverage and minimize geometric distortion. Flight paths and flight altitudes were periodically adjusted to maintain a stable ground sampling distance over variable terrain. The UAV was equipped with an RTK positioning module (DJI, Shenzhen, China), enabling sub-decimeter geolocation accuracy and facilitating precise co-registration among temporal phases. In addition, multispectral imagery was radiometrically calibrated before each flight using the Mavic 3M onboard sunshine sensor (DJI, Shenzhen, China), and both multispectral and LiDAR datasets were processed using standardized radiometric and geometric workflows to ensure cross-phase consistency. To complement the multispectral dataset with structural and topographic information, airborne LiDAR point cloud data were acquired in September 2024 using a VLP-16 LiDAR sensor (Velodyne Lidar, San Jose, CA, USA). Positional accuracy was corrected using an onboard real-time kinematic (RTK) differential positioning system.

Table 1.

Description of Remote Sensing Data.

2.2.3. Remote Sensing Data Preprocessing

Multispectral image preprocessing was conducted using Agisoft PhotoScan Professional (version 1.4.3) to perform orthomosaic generation and geometric alignment. To ensure strict spatial consistency among multi-temporal images, a secondary geometric registration was carried out in ENVI 5.3.1 (Harris Geospatial Solutions, Broomfield, CO, USA) using homologous ground control points [38] for absolute orientation correction, yielding a root mean square error (RMSE) of less than one pixel.

The processed orthomosaic images were exported at a centimeter-level spatial resolution of 5 cm per pixel, projected to the UTM Zone 51N coordinate system based on WGS 1984. Radiometric calibration was implemented using the empirical line method, integrating measurements from an onboard sunshine sensor and three fixed ground reflectance targets—black, white, and gray panels [39]—to mitigate the effects of atmospheric and illumination variability on image spectral characteristics [40]. The final preprocessed results are presented in Figure A1.

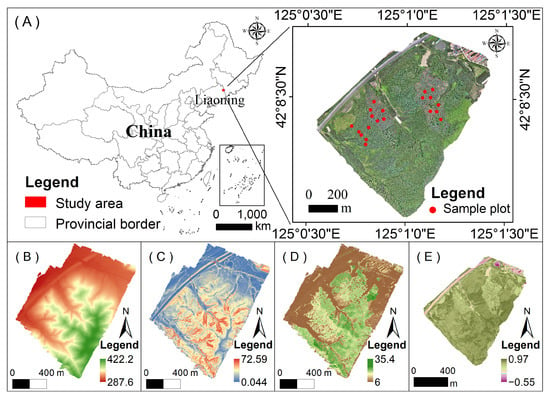

The preprocessing of airborne LiDAR data followed the workflow described by Zhai et al. (2023) [41]. Point cloud normalization began with noise removal through height thresholding and isolated-point detection, followed by separation of ground and non-ground returns using progressive morphological filtering or progressive TIN densification [42]. A digital elevation model (DEM) was generated from ground points, and the elevations of non-ground points were normalized by subtracting the DEM, producing vegetation height information relative to the ground surface (Figure 1B). Based on the DEM, additional topographic factors, including slope and aspect, were derived (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Overview of the study area. (A) Location of the study area in Qingyuan County, Liaoning Province, northeastern China. The right panel shows a high-resolution orthophoto and the distribution of field sampling plots. (B) Digital elevation model (DEM, m). (C) Slope (°) derived from the DEM. (D) Canopy height model (CHM, m) generated from airborne LiDAR data. (E) Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) derived from multispectral imagery.

The normalized point cloud was then resampled and interpolated to enhance data continuity and precision. A canopy height model (CHM) with a 1 m spatial resolution was generated through rasterization, and Gaussian filtering was applied to smooth local noise and suppress outliers (Figure 1D).

2.2.4. Index Calculation and Tree Crown Extraction

For each temporal image, the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) were calculated using the respective spectral bands, defined as follows:

where NIR, RED, and GREEN denote the reflectance values of the near-infrared, red, and green spectral bands, respectively.

Individual tree crown segmentation followed the method proposed by Dalponte and Coomes (2016) [43]. A canopy height model (CHM) derived from the preprocessed LiDAR data was used to identify canopy apexes through a 3 × 3 local maximum filter (LMF). A minimum height threshold of 2 m was applied to remove low-lying vegetation. The detected treetops served as seed points for watershed segmentation, which delineated individual tree crown boundaries as vector polygons.

Given that the dominant host species affected in the study area is Scots pine, a winter-season NDVI threshold (>0.4) was applied to extract evergreen coniferous canopies [44], serving as a proxy for Scots pine distribution. Subsequently, the regional statistics tool in ArcMap 10.8 was used to calculate the median NDVI and NDWI values within each delineated canopy, representing the canopy’s spectral characteristics.

Using this workflow, approximately 8491 individual tree crowns were extracted. Comparison with field survey data indicated an overall canopy extraction accuracy of 98.6%.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Visual Interpretation of Tree Crowns and Classification of Disease Stages Based on High-Resolution Imagery

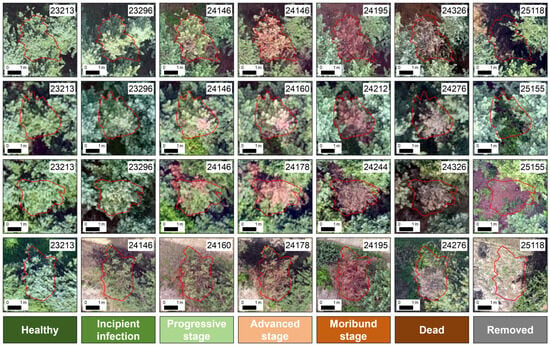

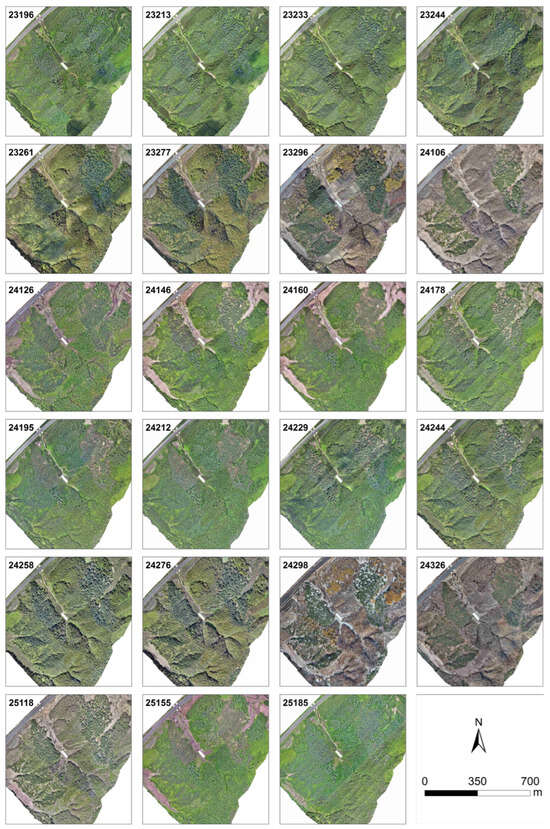

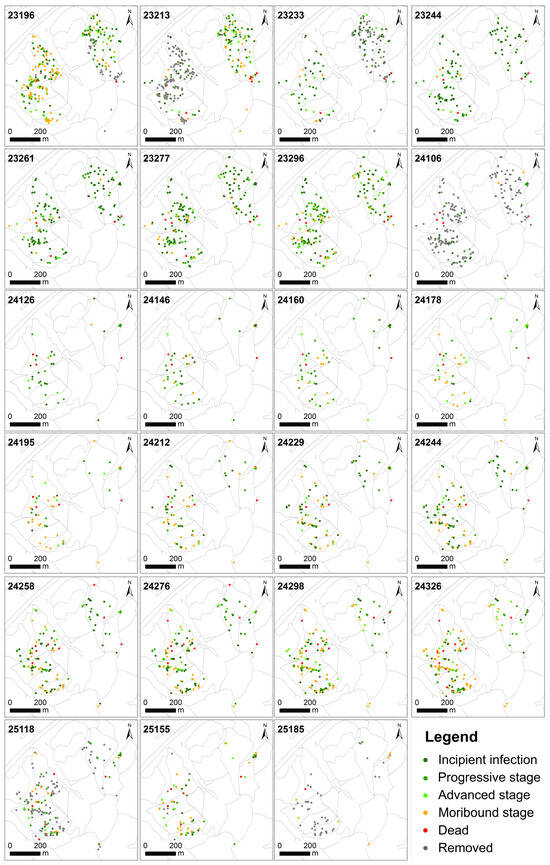

To accurately identify the progressive stages of pine wilt disease, high-resolution multispectral imagery acquired by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) was employed. Manual visual interpretation was conducted to analyze canopy characteristics of individual trees, thereby establishing diagnostic criteria for disease staging. The interpretation criteria included canopy color, textural features, structural integrity, and the degree of branch and foliage exposure (Table 2, Figure 2). Canopy color was primarily used to capture the transition of needle coloration from green to yellow and subsequently to red, while texture and structural integrity characterized canopy density and fragmentation. The degree of branch and foliage exposure reflected the progression of crown degradation and mortality. To ensure the objectivity and reliability of the labeling results, three interpreters independently performed blind assessments without access to others’ annotations or prior information, followed by a reconciliation process for inconsistent cases. To assess the reliability of the interpretation results, the visually derived classifications were systematically compared with field survey data from 20 sample plots. The results exhibited a high degree of concordance, with an overall canopy condition classification accuracy of 98.4% at the plot scale, demonstrating that the proposed visual interpretation criteria effectively discriminate between healthy and declining trees. The annotated results for Phase 23 are presented in Figure A2.

Table 2.

Visual interpretation characteristics of trees at different infection stages.

Figure 2.

Canopy conditions at different stages of pine wilt disease. Red outlines delineate individual tree crowns. The five-digit code in the upper-right corner of each panel indicates the image acquisition date, where the first two digits denote the year and the last three digits represent the day of year (DOY). For example, “23213” corresponds to the 213th day of 2023 (1 August 2023). All subsequent figures use the same date-annotation format.

2.3.2. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE)

To characterize the spatial aggregation pattern of dead or diseased trees, the Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) method was employed to generate a continuous spatial distribution surface. The computation was performed using the Kernel Density tool in ArcGIS 10.8. A default radial basis kernel function was adopted, and the bandwidth (search radius) was automatically optimized according to Silverman’s rule, yielding an optimal range of approximately 50–100 m. The resulting output was a raster surface with a spatial resolution of 5 m. The KDE is defined as follows:

where denotes the estimated density at location x; n is the number of sample points; d is the spatial dimension; h is the bandwidth (search radius); and is the kernel function (here, the Quartic kernel).

2.3.3. Lethal Distance Analysis Based on Semivariance Analysis

Semivariance analysis was employed to quantify the spatial heterogeneity in infection spread distance. For each newly infected tree iii (whose initial infection or mortality time was denoted as ti), the Euclidean distance was measured to the nearest previously infected tree within the set Sti—that is, all trees that had been infected prior to ti and were still present (not yet removed) and capable of disease transmission at that time.

To assess spatial autocorrelation and identify the characteristic scale of disease spread, the empirical semivariogram of the spatial variable Z(x) was calculated as:

where h is the spatial lag interval and N(h) denotes the number of point pairs within that interval. A lag interval of 5 m and a maximum distance of 500 m were used for binning, implemented with geopandas and scipy, using vectorized computation of pairwise distances.

2.3.4. Construction and Evaluation of Spatial Prediction Models

To predict tree mortality risk at the individual-tree level, three machine learning models were developed and compared: a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Random Forest (RF). Prior to model construction, Pearson correlation analysis was performed among all candidate predictors, and variables exhibiting high collinearity (|r| > 0.7) were excluded.

Input variables included temporal diffusion metrics (derived from multi-period distances to infected or dead trees), topographic factors (e.g., slope, aspect), and vegetation structural attributes. To address multicollinearity among sequential distance variables, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied, with the first principal component—explaining over 85% of the total variance—used as a composite variable representing integrated diffusion pressure for modeling.

Model training and validation were conducted using five-fold cross-validation to assess generalization performance. The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied to balance class distributions and mitigate bias due to the limited number of mortality samples. Feature importance was quantified using the percentage increase in mean squared error (%IncMSE) and the increase in node purity (IncNodePurity).

Finally, model performance was evaluated using multiple classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC). These results provided the basis for subsequent mortality probability mapping and identification of key environmental drivers.

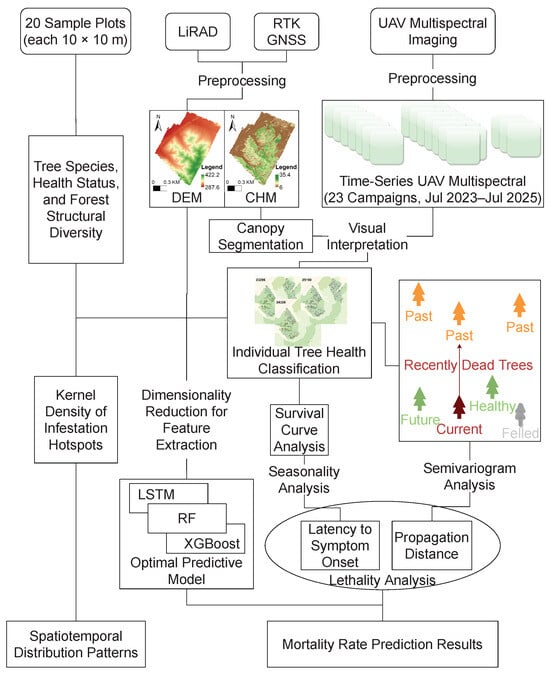

This study establishes a comprehensive technical workflow spanning data acquisition, preprocessing, and model development. The overall procedure is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the methodology.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Pine Wilt Disease–Induced Tree Mortality

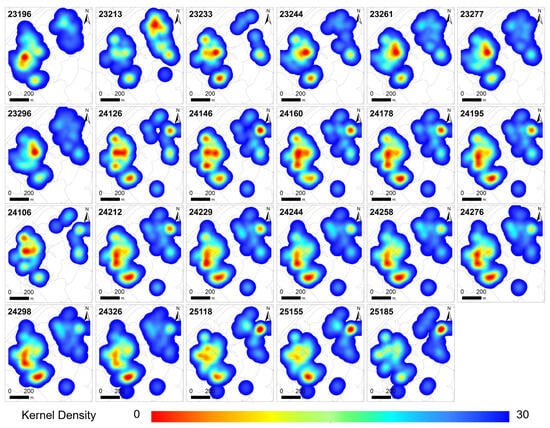

Figure 4 illustrates that tree mortality caused by pine wilt disease consistently displays significant spatial clustering. However, the morphology, intensity, and location of core areas exhibit dynamic changes over time, driven by both disease progression and human interventions.

Figure 4.

Kernel density analysis of hotspots of pine wilt disease–induced tree mortality.

In the early phase of the 2023 outbreak (days 23196–23296), tree mortality was highly aggregated, predominantly concentrated within the interior of the forest stand. Following the initial logging operation on day 23213, the core zone area decreased sharply by 17.2%, with a notable reduction in hotspot frequency. The western hotspot weakened significantly, leaving only a few residual high-density points.

A transient hotspot emerged in the northeast but rapidly dissipated after subsequent logging. Conversely, the previously declining western region developed a new core area, with the overall hotspot centroid shifting northeastward. This indicates a dynamic reconfiguration of the spatial pattern, driven by localized disease spread and management interventions.

By 2024, the spatial pattern stabilized, though it became more fragmented, with hotspot centers progressively migrating southward. Except for a brief disturbance caused by intensive logging in April (day 24106), the epidemic transitioned from localized clustering to broader diffusion across a larger area.

Selective logging reduced both the number and intensity of hotspots but may have inadvertently slowed the decline of residual hotspots by altering stand structure, thereby influencing the tempo and trajectory of disease spread. In 2025, two consecutive logging events further reshaped the spatial configuration, resulting in an overall reduction in kernel density and lateral expansion of hotspots toward both sides of the forest stand. A new high-density center gradually formed in the northeast, while the western hotspot nearly disappeared, signaling a marked shift in the direction of spread. The diffusion pattern evolved from a concentrated form to a multi-centered, multidirectional configuration.

In spatial terms, the extent of pine wilt disease (PWD) impact within the study area expanded annually. The total hotspot area increased from 8.71 ha in 2023 to 10.0 ha in 2024, before slightly decreasing to 9.96 ha in 2025, yet remaining above the initial level. Concurrently, hotspot intensity declined steadily, with kernel density values dropping from 30–37 to approximately 20, indicating reduced clustering and a transition to a more dispersed spatial distribution.

Throughout the study period, tree mortality remained concentrated within the interior of the forest stand, with no expansion along its edges. This pattern suggests that disease transmission was predominantly driven by short-range diffusion, while surrounding heterogeneous landscape features, such as broad-leaved forests, croplands, and water bodies, acted as consistent barriers to epidemic spread.

Overall, the PWD epidemic exhibited a dynamic evolution characterized by range expansion, intensity attenuation, and directional shifts. This trajectory reflects the interplay of diffusion mechanisms, host distribution patterns, and management interventions.

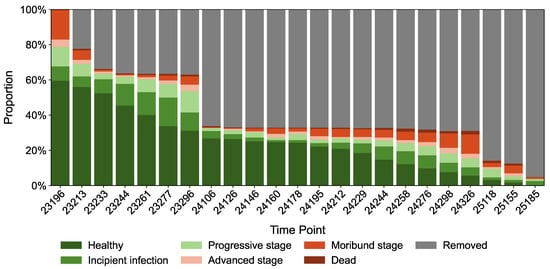

From a temporal perspective, Figure 5 illustrates the temporal changes in the proportional composition of trees across disease severity classes relative to the total number of dead or affected trees. Initially, the forest stand was predominantly composed of healthy and mildly declining trees, which gradually transitioned to a dominance of dead individuals over time. Under intensive logging interventions, the proportion of declining trees decreased significantly, and the rate of disease progression shifted from rapid to slower, eventually stabilizing. Based on logging records and interannual variations, the monitoring period can be divided into three distinct phases:

Figure 5.

Temporal Variation in Disease Severity Classes.

Phase I (Initial Survey, 2023, Day 23196): Healthy trees comprised 59.55% of the stand, with low proportions of late-declining, dying, and dead individuals. Disease severity remained mild to moderate, and no logging had been implemented. From days 23213 to 23277, the proportion of healthy trees declined steadily, with a notable accumulation of early- and mid-stage declining individuals. By day 23244, healthy trees fell below 50%, while the harvested proportion increased to 36.2%, indicating accelerated disease spread.

Phase II (15 April 2024, Day 24106): Early-stage decline progressed to mid- and late-stage or dying conditions, with a continued rise in these categories. Intensive selective logging increased the harvested proportion to approximately 66%, significantly reducing the decline rate of healthy trees from an annual average of 4.7% to 1.9%. This highlights the critical role of targeted interventions in mitigating disease spread and optimizing forest stand structure.

Phase III (2025): The decline in healthy tree proportions slowed further to an average of 1.8%, accompanied by a reduction in damaged individuals. By the final survey (day 25185), the harvested proportion reached 95%, with nearly all diseased trees removed. However, the proportion of healthy trees dropped to zero, with no evidence of recovery, suggesting an irreversible decline primarily driven by pine wilt nematode infection.

3.2. Spatial Spread and Mortality Analysis of Pine Wilt Disease

3.2.1. Transmission Distance

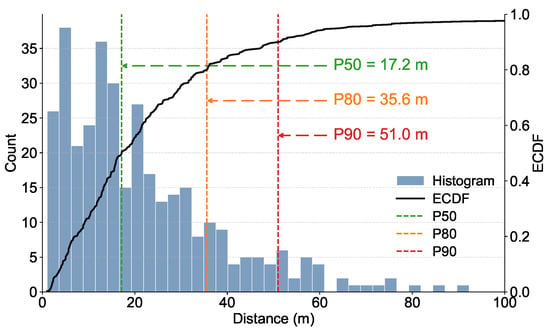

In this study, the straight-line distance between each newly infected pine and the nearest previously dead pine was defined as the “nearest diseased-tree distance” and quantified directly, with results presented in Figure 6. The distribution of these distances exhibited a pronounced right-skewed pattern, with most newly infected trees occurring at relatively short distances, indicating strong local dispersal and spatial clustering of pine wilt disease. Specifically, 50% of transmission events occurred within 17.2 m (P50), suggesting that disease spread is primarily driven by localized, neighbor-to-neighbor transmission. Additionally, 80% of events were confined within 35.6 m (P80), and 90% did not exceed 51.0 m (P90), demonstrating that the majority of transmission events occur within a fine-scale range of less than 20 m. Although rare long-distance transmission events exceeding 80 m were observed in the tail of the distribution, their low frequency underscores that local reinfection and short-range spread among adjacent trees dominate the dispersal dynamics of pine wilt disease. Long-distance dispersal events are likely associated with vector insect activity, topographic factors, or anthropogenic disturbances.

Figure 6.

Distribution of transmission distances of pine wilt disease.

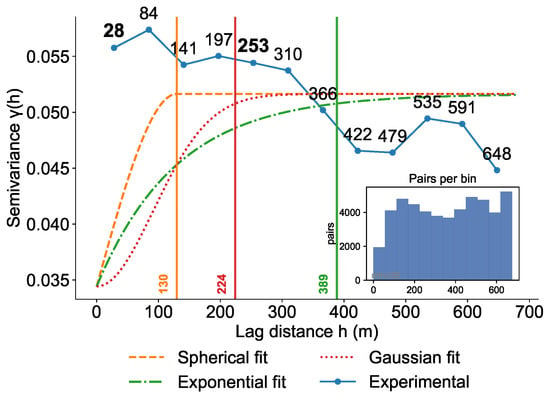

To quantify the spatial dependence of pine wilt disease transmission and elucidate the spatial autocorrelation structure among infection events, we conducted model fitting and analysis using the semivariance function, as shown in Figure 7. Based on the empirical and theoretical semivariogram structures, we further derived two key management thresholds. We first identified the short-range spatial dependence by locating the inflection point of the empirical semivariogram. A smoothing spline was fitted to , and the first derivative was calculated. The results indicated significant spatial autocorrelation within approximately 28 m, reflecting strong similarity among neighboring trees. Because this point corresponds to the maximum curvature of the semivariogram, it delineates the upper limit of strong local spatial dependence attributable to short-distance beetle-mediated transmission; accordingly, a radius of 28 m was adopted as the sanitation threshold. This range corresponds to localized, short-range transmission, where primary infections typically occur within tens of meters. As spatial separation increased, the semivariance rose rapidly, stabilizing at approximately 80–100 m, indicative of robust spatial autocorrelation within this range. At larger scales, the empirical semivariogram displayed a local peak at around 254 m ( = 0.055), followed by a decline to a trough near 424 m ( = 0.045), suggesting that transmission beyond 300 m exceeds the effective correlation range, with infection events becoming spatially random. This pattern is likely driven by external factors such as anthropogenic activities or sporadic long-distance dispersal. Fitting with three theoretical models—spherical, Gaussian, and exponential—yielded correlation ranges of 130 m, 225 m, and 390 m, respectively, with the spherical model providing the best fit. The sill (0.052) was comparable to the nugget effect (0.035), indicating that a portion of the variation may stem from microscale heterogeneity or measurement error. The distance corresponding to 95% of the theoretical sill is 141 m. At this distance, the empirical semivariance closely matches the theoretical semivariance, indicating that spatial structural dependence has nearly diminished and is transitioning toward random variation. Therefore, 141 m is identified as the key monitoring radius. The transmission pattern exhibited a dual-scale structure: local spread is primarily driven by vector insect activity, while long-distance dispersal is influenced by external disturbances. Based on these findings, we recommend a 28-m radius for sanitation and removal efforts, intensive monitoring within 141 m, and targeted interventions at high-risk interfaces around 254 m.

Figure 7.

Semivariogram model fitting and spatial autocorrelation analysis.

3.2.2. Latency Period

Using temporal annotations of individual pine trees within plots derived from a continuous series of remote sensing images, we defined the onset of disease symptoms as the “disease phase” and the appearance of terminal states—such as tree death, felling, or complete crown damage—as the “death phase.” The interval between these phases, termed the lethal latency period, quantifies the duration from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus infection to host mortality.

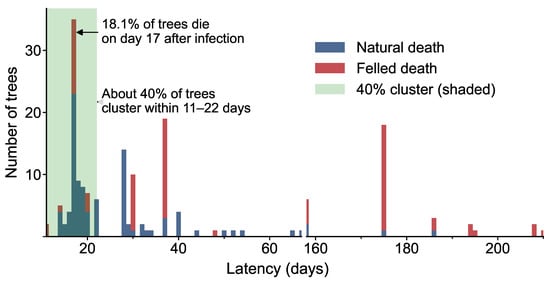

Through continuous time-series monitoring, we reconstructed the latency period distribution from initial infection to host death, distinguishing between natural mortality and logging removals (Figure 8). The latency distribution exhibited a pronounced multimodal structure, with a right-skewed pattern and a high concentration of mortality events within a short timeframe. Approximately 40% of deaths occurred within 11–22 days post-infection, peaking at day 17, when 18.1% of trees succumbed, indicating a rapid lethality rate in the early infection stage. Secondary and tertiary mortality peaks occurred on days 37 and 175, representing 9.8% and 9.3% of total deaths, respectively, suggesting delayed mortality responses in some individuals during mid- and late-stage disease progression.

Figure 8.

Statistical Distribution of the Lethal Latency Period of Pine Wilt Disease.

Further analysis revealed that 90% of mortality events occurred within 16–275 days, with an extended tail indicating substantial inter-individual variation in disease progression. Naturally deceased trees were predominantly associated with shorter latency periods, while logging removals were more frequent in the intermediate to late stages.

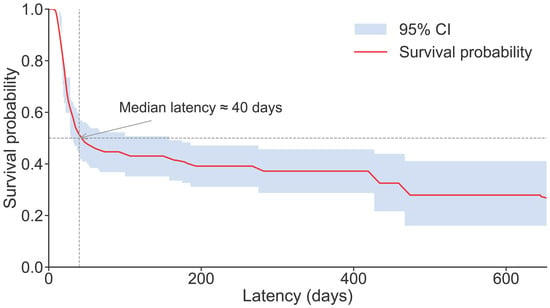

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve (Figure 9) delineates the distributional characteristics of the latency period from Bursaphelenchus xylophilus infection to host mortality in pine wilt disease. The survival probability exhibited a characteristic multi-phase decline over time. In the early latency phase (0–60 days), survival probability decreased rapidly, with approximately 50% of individuals succumbing by day 40, indicating that most hosts entered the lethal phase shortly after infection. Between 60 and 300 days, the rate of decline slowed considerably, with mortality events becoming more dispersed, reflecting inter-individual variability in response to infection and heterogeneity in disease progression. Beyond 300 days, the curve showed a modest long-tail extension; however, due to the limited sample size and sparse mortality events in this period, declines in survival probability and fluctuations in confidence intervals were primarily driven by individual cases and should be interpreted cautiously. Overall, the latency distribution was predominantly characterized within the first 200 days, marked by early concentrated mortality, a gradual mid-term decline, and occasional delayed deaths in later stages.

Figure 9.

Kaplan–Meier Survival Curve of the Latency Period in Pine Wilt Disease.

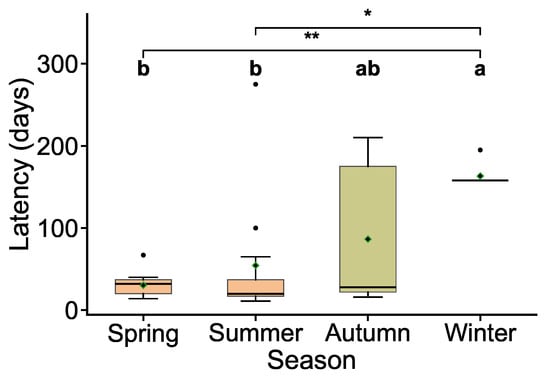

To investigate the temporal heterogeneity of the latency period in pine wilt disease, we categorized infected samples into four seasonal groups based on the timing of infection: spring (April–May), summer (June–August), autumn (September–October), and winter (November). A non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate overall differences in latency distributions across the four groups, followed by pairwise comparisons using the Mann–Whitney U test with Holm correction for multiple testing.

The results revealed significant seasonal variations in latency distributions (Figure 10), with hosts infected in different seasons displaying distinct temporal patterns. Spring and summer infections exhibited significantly shorter latency periods compared to winter infections (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). Spring infections had a median latency below 50 days with a tightly clustered distribution, while summer infections also showed short latencies but with a higher prevalence of outliers, both reflecting rapid disease progression and concentrated mortality events. In contrast, autumn infections displayed significantly prolonged latency periods with a wider interquartile range, indicating increased inter-individual variability and a more dispersed distribution of mortality events. Winter infections exhibited the longest latency periods, with both median and mean values significantly exceeding those of other seasons, suggesting enhanced overwintering capacity and a potential for delayed transmission risk within the disease cycle.

Figure 10.

Seasonal Variation in the Distribution of Lethal Latency Periods. Box plots depict the median (horizontal line) and mean (diamond). Black dots represent outliers. Letters above the boxes denote results from one-way ANOVA with post hoc tests (identical letters indicate non-significant differences). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

3.3. Spatial Prediction Model for the Spread of Pine Wood Nematode Disease

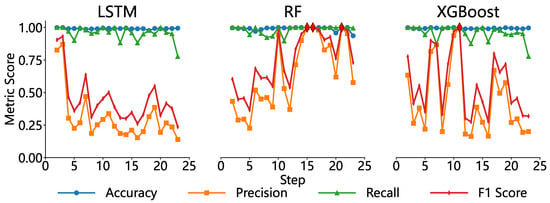

To evaluate the effectiveness of various machine learning algorithms in predicting individual tree mortality risk during the spread of pine wood nematode (PWN) disease, this study constructed and compared three predictive models—Random Forest (RF), Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—using stand structural and topographic features derived from multi-temporal UAV remote sensing data (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Comparison of Model Performance in Predicting Disease Outbreaks.

Overall, all three models exhibited high accuracy and recall, with mean values approaching or exceeding 0.90, indicating robust capability in identifying most infected trees. However, notable differences were observed in precision and F1 scores across the models.

The Random Forest model demonstrated the most consistent performance, achieving mean precision and F1 scores of 0.85 and 0.87, respectively, with a standard deviation below 0.05. This suggests that RF effectively minimized false positives while maintaining a high detection rate, striking an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity. In contrast, while the LSTM model achieved near-perfect accuracy (close to 1.0), its precision was lower at 0.65, with a false positive rate of approximately 30%, indicating a tendency toward over-prediction, where many healthy trees were misclassified as infected. XGBoost performed well in short-term predictions (1–3 steps ahead), but its precision and F1 scores fluctuated significantly with increasing prediction horizons (standard deviation > 0.10), reflecting poor temporal stability and limiting its utility for continuous forecasting tasks. Therefore, RF was chosen as the final model due to its superior overall performance among the three tested algorithms.

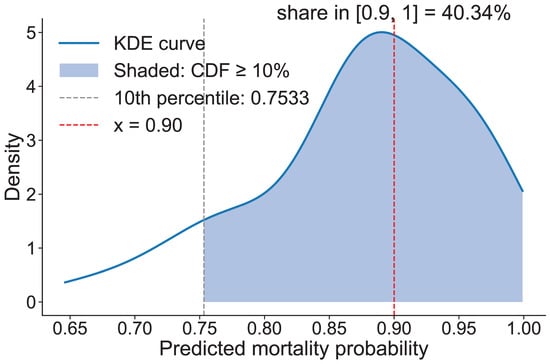

To further validate the model’s capability to identify individual tree mortality risk due to PWD, we conducted a statistical analysis of the predicted mortality probability distribution for all confirmed dead trees (Figure 12). The results revealed that the predicted probabilities for these trees were predominantly concentrated in the high-risk range, indicating the model’s effectiveness in assigning elevated risk scores to trees that ultimately succumbed to the disease.

Figure 12.

Predicted Results.

For the purposes of risk stratification and practical management, the predicted mortality probabilities were categorized into four intervals: 0–30% (low risk), 30–60% (moderate risk), 60–90% (high risk), and 90–100% (extremely high risk). The analysis showed that 40.34% of the confirmed dead trees were classified as extremely high risk (≥90%), while 98.6% fell within the high-risk category (≥60%) when this threshold was applied.

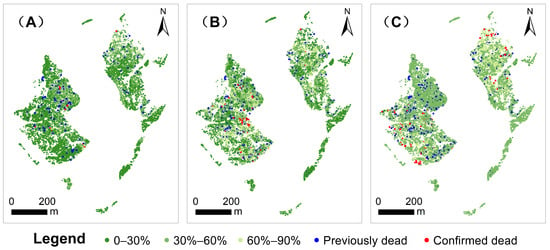

Simulations of PWD disease spread from 2023 to 2025, based on the Random Forest model, demonstrate the model’s ability to accurately replicate the spatiotemporal distribution of the disease, with a high degree of spatial concordance between predicted and observed tree mortality locations (Figure 13). The predictions indicate that the disease will continue to spread, with the affected area expanding progressively and regions of high mortality rates exhibiting pronounced spatial clustering. Without effective control measures, this trend poses a growing threat to regional forest ecosystems.

Figure 13.

Predicted Results. (A) Predicted pine wilt disease outbreak in 2023. (B) Predicted outbreak in 2024. (C) Predicted outbreak in 2025.

Spatially, low-mortality areas (0–30%) persist throughout the study period, while moderate- to high-mortality areas (30–90%) expand annually, reflecting the ongoing propagation and cumulative impact of the disease. By 2025, high-mortality zones (≥90%) become significantly clustered within core forest stands, showing strong alignment with observed mortality points, which underscores the model’s reliability in predicting high-risk areas. Notably, later observed mortality points (blue dots) exhibit substantial spatial overlap with early predicted high-probability mortality points (red dots), further validating the model’s effectiveness in identifying risk hotspots.

Additionally, the predictions highlight the temporal dynamics of disease spread. As sample size increases and transmission effects accumulate, the number of potentially dead trees rises steadily, with both the abundance and spatial distribution of high-probability mortality trees closely matching observed data.

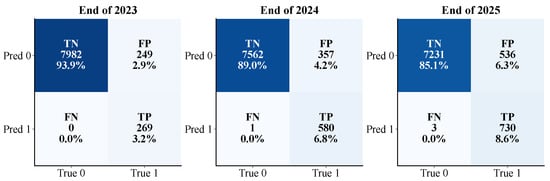

Figure 14 illustrates the Random Forest model’s tree-level predictions for red pines affected by PWD disease across 2023, 2024, and 2025. Overall, the model consistently demonstrated strong discriminative performance, maintaining an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.96 across all three years, indicating robust and reliable differentiation between healthy and infected trees.

Figure 14.

Confusion Matrices of Random Forest Model Predictions for 2023–2025.

However, the structural composition of the prediction results varied significantly over time. In 2023, the model achieved balanced classifications, with an accuracy of approximately 80% for identifying healthy trees, though the detection rate for infected trees was relatively low. As the disease progressed and sample distribution shifted, the 2024 model improved its detection of infected trees but exhibited a notable increase in false positives among healthy trees, suggesting a shift toward over-predicting high-risk classifications. By 2025, this trend intensified, with the model classifying the majority of trees as potentially infected, resulting in a recognition rate for healthy trees dropping below 10%. This indicates that, as the disease spread expanded, the model’s sensitivity to risk increased, but its specificity significantly declined.

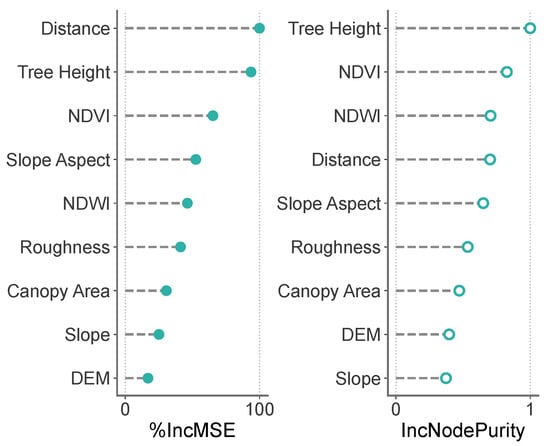

To assess the relative influence of environmental and stand-structural factors on tree mortality risk due to PWD, this study conducted a feature importance analysis using the Random Forest model. The analysis employed two complementary metrics—percentage increase in mean squared error (%IncMSE) and increase in node purity (IncNodePurity)—to quantify the contribution of each input variable to the model’s predictive performance (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Feature Importance Analysis of the Random Forest Model.

The results identified Distance (distance to the nearest dead tree) and Tree Height as the top-ranking factors in both metrics, underscoring their critical role in driving model accuracy. Notably, Distance exhibited the highest %IncMSE value, highlighting spatial proximity as the primary driver of disease occurrence and spread, consistent with the limited dispersal capacity of vector insects and the pronounced spatial clustering of PWD. In terms of IncNodePurity, Distance consistently contributed the most to improving node purity, while Tree Height played a more prominent role in node-splitting decisions, indicating that the clustering of nearby dead trees and stand structural characteristics increasingly amplify mortality risk as the epidemic progresses.

Spectral vegetation indices, such as NDVI and NDWI, also demonstrated high importance, ranking among the top three in IncNodePurity and within the top five in %IncMSE. This suggests that host physiological traits, including growth vigor and water status, significantly influence disease susceptibility. In contrast, topographic factors exhibited relatively lower contributions, indicating limited direct effects at the stand scale, though they may indirectly influence disease spread through effects on microclimatic conditions or vector insect behavior.

4. Discussion

This section interprets the major findings of our study and relates them to previous work on PWD transmission, mortality dynamics, and remote-sensing-based monitoring. Using long-term UAV and LiDAR observations, we provide new evidence on spatial spread, temporal progression, and host-related risk factors. The following subsections discuss these results in comparison with existing studies and highlight their implications for disease forecasting and management.

4.1. Stand-Scale Characteristics of Individual-Tree Transmission Dynamics and Lethality Analysis

This study achieved continuous temporal monitoring and reconstruction of PWD transmission dynamics at the individual-tree level under natural stand conditions. This approach represents a significant methodological advancement over previous research, which predominantly relied on controlled experiments [22], single-phase remote sensing detection [21], or macro-scale spatial analyses [25]. By providing novel evidence, this work enhances our understanding of the disease’s transmission dynamics and lethal mechanisms at the stand scale.

The findings indicate that approximately 50% of transmission events occur within a 17.2-m radius, highlighting a pronounced near-field clustering pattern at small spatial scales. This result aligns closely with Tan et al.’s reported transmission scale of 10.26 m, derived from mean nearest-neighbor distances, although their method, which relied on identifying dead trees via visible canopy symptoms, may have been confounded by other diseases [34]. At a broader scale, Choi et al. observed that 88.8% of dispersal events occurred within 1 km, with a maximum dispersal distance of 7.71 km [45]. Together, these findings support a composite transmission model characterized by predominantly short-distance spread interspersed with occasional long-distance jumps.

This study further reveals that the observed diffusion pattern is strongly influenced by ecological factors, including the limited foraging range of vector beetles and human-mediated timber transport. These factors form a critical ecological foundation for understanding the spatiotemporal dynamics of PWD.

From a temporal perspective, approximately 40% of mortality events occurred 11–22 days post-infection, with about 50% of hosts succumbing within 40 days. These results are consistent with prior studies on disease progression. For instance, Melakeberhan and Webster reported that hosts may die as early as 14 days post-inoculation, exhibiting early symptoms such as needle discoloration and vascular necrosis [46]. Similarly, Kiyohara noted a strong seasonal dependency in mortality, with summer-infected trees typically dying within 40–60 days, while those infected in autumn or winter experienced significantly delayed mortality [47]. The continuous observations in this study confirm these patterns of concentrated and seasonally influenced mortality, suggesting that ecological processes—such as temperature, host metabolic state, and vector beetle activity—collectively shape the temporal progression of PWD.

In contrast to previous studies relying on static remote sensing or point-based epidemiological inferences [32], this research utilized 23 phases of centimeter-level UAV imagery, LiDAR point clouds, and ground surveys to quantitatively reconstruct the entire individual-tree process of “infection–decline–death/removal.” This approach revealed critical transmission characteristics, including fluctuations in the latent period and spatial diffusion heterogeneity, which are challenging to detect using traditional methods.

4.2. Predictive Performance of the Random Forest Model and Application of Risk Thresholds

This study systematically evaluated the performance of three machine learning models across varying forecasting horizons, revealing significant differences in their predictive capabilities. In the context of early warning systems for forest pest and disease outbreaks—a task characterized by class imbalance—the Precision–Recall (PR) curve offers a robust measure of a model’s ability to effectively manage false positives [48].

The results indicated that, despite achieving relatively high overall accuracy, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model exhibited consistently low Precision and F1 scores, reflecting its limited ability to distinguish true positives from false positives. This aligns with the known tendency of deep temporal models to overfit in small-sample scenarios, prioritizing higher Recall over Precision [49]. The XGBoost model demonstrated superior Precision and F1 scores at specific forecasting horizons but displayed significant temporal variability, underscoring its sensitivity to data distribution, consistent with prior findings on the instability of boosting-based models [50].

In contrast, the Random Forest (RF) model exhibited the most balanced performance across all metrics, with multi-step forecasting Precision improving by approximately 15–20% and F1 scores increasing by 10–18%. Notably, RF maintained significantly greater stability during mid-to-late forecasting stages compared to other models, effectively mitigating the pronounced performance fluctuations observed in XGBoost [51]. This robustness stems from RF’s superior capacity to handle noise in spatiotemporal data and capture nonlinear relationships, rendering it particularly well-suited for individual-tree-level risk prediction and management decision-making.

Consistent with prior research, RF has demonstrated reliable performance in both individual-tree remote sensing identification and regional-scale predictions [52,53], surpassing other models in accuracy, stability, and practical applicability. Additionally, this study introduced the concept of high-probability mortality to quantify the model’s ability to accurately identify trees at risk of death, providing an actionable threshold for individual-tree risk management. Unlike conventional static classification methods [14,34], this study leveraged long-term dynamic monitoring to directly correlate predicted mortality probabilities with observed death events, revealing distinct spatial and seasonal clustering patterns of high-risk individuals for the first time.

4.3. Key Influencing Factors and Driving Mechanisms of Transmission

The diffusion modeling results of this study indicate that structural characteristics at both stand and landscape levels play a central regulatory role in the transmission and mortality dynamics of PWD. The findings are consistent with previous research, showing that stands with higher tree density, greater canopy closure, and stronger landscape connectivity are subjected to increased pressure from vector beetles, leading to elevated infection rates and mortality risks [54].

Local host abundance and landscape continuity exhibited a pronounced synergistic effect in enhancing the potential for disease spread. Among all structural variables, tree height ranked among the highest in both feature-importance metrics, suggesting that vigorously growing individuals with larger diameters at breast height (DBH) serve as core hosts within the transmission network [55]. Chemical ecology studies have demonstrated that such trees emit higher concentrations of monoterpenes (e.g., -pinene) [56], which strongly attract vector beetles and render these trees preferred targets for feeding and pathogen transmission. Once infected, these individuals often become secondary centers of disease spread, accelerating localized outbreaks [57].

Remote sensing vegetation indices also showed substantial explanatory power in the model. As indicators of canopy vigor and chlorophyll content, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and its red-edge or narrow-band variants ranked within the top three in IncNodePurity and the top five in %IncMSE. Previous studies have reported a marked decline in NDVI following infection [11]; this study further demonstrates that pre-infection NDVI levels can serve as an early signal of host susceptibility, providing an actionable indicator for outbreak early warning.

The distance to the nearest dead tree ranked first in %IncMSE, underscoring the dominant influence of spatial proximity on disease transmission. This finding supports the mechanism described in earlier studies [33], in which dying or dead hosts act as focal sites for vector beetle feeding and oviposition, thereby facilitating nematode dispersal to adjacent healthy individuals. In contrast, while crown width reflects the host’s growth condition, its explanatory power for transmission dynamics is limited, as canopy contact does not constitute a direct pathway for pathogen spread. Therefore, in spatial modeling of PWD, the distance between tree stem centers should be adopted as a key spatial parameter [34], rather than relying solely on canopy overlap to assess transmission risk.

5. Conclusions

This study employed a 23-phase UAV remote-sensing dataset to reconstruct the development trajectory of PWD within the study area, enabling high-precision characterization of its spatial diffusion patterns and temporal evolution at the stand scale. Based on these results, we further developed and validated a stand-level model capable of predicting tree-level mortality risk. The main findings are as follows:

- At the stand scale, PWD exhibited a pronounced short-distance diffusion pattern (approximately 17 m), with exceptionally strong spatial autocorrelation within a 28 m radius. Regarding infection latency and mortality dynamics, approximately half of the infected trees died within 40 days after initial infection, while the latent period was markedly prolonged during winter.

- Among all evaluated algorithms, including XGBoost and LSTM, the random forest model demonstrated the highest predictive performance for tree-level mortality risk (AUC = 0.96). By applying a 60% risk threshold, the model achieved highly accurate identification of high-probability mortality cases, with a prediction accuracy of up to 98%.

Overall, this study provides a scalable methodological framework for high-temporal-resolution monitoring of forest disease dynamics and operational-scale risk management, thereby bridging the gap between mechanistic understanding of pathogen diffusion and precision-oriented disease control strategies.

6. Limitations and Prospects

This study utilized high-temporal-resolution, long-term unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery to characterize the spatiotemporal dynamics of PWD at the individual-tree scale, establishing a methodological framework for precise monitoring and risk prediction in the epidemic. However, constrained by research conditions and data characteristics, the interpretability and generalizability of the findings are subject to several limitations.

First, the spatial scope of the study is limited, covering only 130 hectares with minimal environmental heterogeneity, which hindered the statistical identification of the effects of climatic and micro-environmental factors. Meteorological variables such as temperature, humidity, and precipitation exhibited negligible spatial variation across the study area and thus could only be represented by a single weather-station time series. After removing seasonal trends, their short-term fluctuations did not align with the 15–20-day UAV revisit interval, making it difficult to establish meaningful correspondence with the infection and mortality progression of individual trees. Consequently, this study reflected climatic effects only indirectly through the “seasonal variation in lethal latency,” rather than incorporating climate variables as explicit predictors in the spatial forecasting model. Future research will expand to larger spatial scales and diverse climatic gradients, incorporating multi-level modeling and analyses of extreme weather events to more comprehensively elucidate the regulatory effects of climate change on transmission rates and mortality risks.

Second, the influences of forest stand structure and tree species composition remain underexplored. The study area exhibits a mosaic of forest types with low species mixing and minimal variation in vector population density. While results suggest that disease spread is primarily driven by host distribution and landscape configuration, this conclusion is limited by the representativeness of the study site. Field surveys and multi-temporal UAV imagery consistently showed that infections were almost entirely confined to plantations of Pinus koraiensis, with no signs of spread into adjacent mixed forests throughout the monitoring period. Accordingly, it was not feasible to construct statistically meaningful cross-type comparisons among forest stands. Moreover, although factors such as slope, aspect, elevation, and surface roughness were included as covariates in the model, their overall contributions were markedly lower than those of host spatial distribution and local dispersal pressure, likely due to the relatively modest topographic variation and the high homogeneity of stand composition. Future studies should target regions with greater forest type diversity to validate the influence of structural characteristics on transmission dynamics and enhance model applicability.

Overall, these limitations highlight deficiencies in spatial scale, structural diversity, and mechanistic representation. Expanding research to encompass broader spatiotemporal scales, additional ecological processes, and more sophisticated data integration will deepen our understanding of PWD transmission mechanisms and risk dynamics, ultimately providing robust scientific support for optimizing integrated management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B., C.Z. and Z.R.; methodology, X.J., G.B. and C.Z.; software, X.J. and X.X.; validation, X.J. and T.L.; formal analysis, X.J., G.B. and T.L.; investigation, X.J., M.D., X.X. and S.X.; resources, G.B. and Z.R.; data curation, M.D., X.X. and S.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.J.; writing—review and editing, X.J., G.B., Z.R. and C.Z.; visualization, X.J. and T.L.; supervision, G.B. and C.Z.; project administration, G.B.; funding acquisition, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research and Development Project of Jilin Province, grant number 20230202098NC.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Time-series UAV orthomosaics showing forest canopy changes over 23 observation periods.

Figure A2.

Spatiotemporal dynamics of infected and dead trees over 23 observation periods.

References

- Diagne, C.; Leroy, B.; Vaissiere, A.C.; Gozlan, R.E.; Roiz, D.; Jaric, I.; Salles, J.M.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Courchamp, F. High and rising economic costs of biological invasions worldwide. Nature 2021, 592, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiya, Y. History of pine wilt disease in japan. J. Nematol. 1988, 20, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Aierken, N.; Wang, G.; Chen, M.; Chai, G.; Han, X.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, X. Assessing global pine wilt disease risk based on ensemble species distribution models. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, D.; Zhang, B.; Sun, H.; Yan, J.; Ding, J.; Ma, X. Risk Assessment of Carbon Stock Loss in Chinese Forests Due to Pine Wood Nematode Invasion. Forests 2025, 16, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Su, H.; Ding, T.; Huang, J.; Liu, T.; Ding, N.; Fang, G. Refined Assessment of Economic Loss from Pine Wilt Disease at the Subcompartment Scale. Forests 2023, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Fu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Shu, Q. Early feature study of Yunnan pine pinewood nematode disease based on hyperspectral remote sensing of ground objects. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Ren, J.; Ren, L.; Luo, Y. Pine Wilt Disease in Northeast and Northwest China: A Comprehensive Risk Review. Forests 2023, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, S.; Hassan, S.S.; Yang, L.; Ma, M.; Li, C. Detection Methods for Pine Wilt Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Plants 2024, 13, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beurs, K.; Townsend, P. Estimating the effect of gypsy moth defoliation using MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3983–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquarella, V.J.; Bradley, B.A.; Woodcock, C.E. Near-Real-Time Monitoring of Insect Defoliation Using Landsat Time Series. Forests 2017, 8, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, D.; Ren, L.; Luo, Y. Identification of Pine Wilt Disease-Infested Stands Based on Single- and Multi-Temporal Medium-Resolution Satellite Data. Forests 2024, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, H.; Shen, H.; Ma, L.; Sun, L.; Fang, G.; Sun, H. Surveillance of pine wilt disease by high resolution satellite. J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Zhao, J.; Huang, J. Monitoring Pine Wilt Disease Using High-Resolution Satellite Remote Sensing at the Single-Tree Scale with Integrated Self-Attention. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, D.; Ren, L. A machine learning algorithm to detect pine wilt disease using UAV-based hyperspectral imagery and LiDAR data at the tree level. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 101, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Feng, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, H.; Jin, G. YOLOv8-MFD: An Enhanced Detection Model for Pine Wilt Diseased Trees Using UAV Imagery. Sensors 2025, 25, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, L.; Yao, Z.; Li, N.; Long, L.; Zhang, X. Intelligent Identification of Pine Wilt Disease Infected Individual Trees Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xie, Z.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Long, Y.; Lan, Y.; Liu, T.; Sun, S.; Zhao, J. Early detection of pine wilt disease based on UAV reconstructed hyperspectral image. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1453761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Technical Scheme for the Control of Pine Wood Nematode Disease (2024 Edition) SSS; National Forestry and Grassland Administration: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, H.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, D.; Huang, J. A GA and SVM Classification Model for Pine Wilt Disease Detection Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Imagery. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, D.; Ren, L. Early detection of pine wilt disease using deep learning algorithms and UAV-based multispectral imagery. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 497, 119493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Zhang, B.; Fang, G.; Yang, S.; Guo, L.; Huang, W.; Yao, J.; Jiao, Q.; Sun, H.; Yan, J. Early Detection of Pine Wilt Disease by Combining Pigment and Moisture Content Indices Using UAV-Based Hyperspectral Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Lin, J.; Xie, T. Exploring the Potential of UAV-Based Hyperspectral Imagery on Pine Wilt Disease Detection: Influence of Spatio-Temporal Scales. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.G.; Cho, H.B.; Youm, S.K.; Kim, S.W. Detection of Pine Wilt Disease Using Time Series UAV Imagery and Deep Learning Semantic Segmentation. Forests 2023, 14, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linit, M. Nematode vector relationships in the pine wilt disease system. J. Nematol. 1988, 20, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, X. Occurrence Prediction of Pine Wilt Disease Based on CA–Markov Model. Forests 2022, 13, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Chen, A.; Li, Y.; Han, X.; Lin, H. Predicting the Potential Distribution of Pine Wilt Disease in China under Climate Change. Insects 2022, 13, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, J.; Huang, J.; Fang, G. Risk prediction of pine wilt disease based on graphical convolutional network in China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 6550–6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Deng, J.; Yan, W.; Zheng, Y. Habitat Suitability of Pine Wilt Disease in Northeast China under Climate Change Scenario. Forests 2023, 14, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Du, G.; Fang, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, T.; Li, R. UGT440A1 Is Associated With Motility, Reproduction, and Pathogenicity of the Plant-Parasitic Nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 862594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, R.; Hu, X.; Liang, G.; Huang, S.; Lian, C.; Zhang, F.; Wu, S. Landscapes drive the dispersal of Monochamus alternatus, vector of the pinewood nematode, revealed by whole-genome resequencing. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 529, 120682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estorninho, M.; Chozas, S.; Mendes, A.; Colwell, F.; Abrantes, I.; Fonseca, L.; Fernandes, P.; Costa, C.; Máguas, C.; Correia, O.; et al. Differential Impact of the Pinewood Nematode on Pinus Species Under Drought Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 841707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiya, Y. Pathology of the pine wilt disease caused by Bursaphelenchus-xylophilus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1983, 21, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Chon, T.S.; Takasu, F.; Choi, W.I.; Park, Y.S. Simulating Pine Wilt Disease Dispersal With an Individual-Based Model Incorporating Individual Movement Patterns of Vector Beetles. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 886867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Lin, Q.; Du, H.; Chen, C.; Hu, M.; Chen, J.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Y. Detection of the Infection Stage of Pine Wilt Disease and Spread Distance Using Monthly UAV-Based Imagery and a Deep Learning Approach. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, H.; Sheng, R.C.; Sun, H.; Sun, S.H.; Chen, F.M. The First Record of Monochamus saltuarius (Coleoptera; Cerambycidae) as Vector of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and Its New Potential Hosts in China. Insects 2020, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xian, X.; Yang, N.; Guo, J.; Zhao, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, W. Risk assessment framework for pine wilt disease: Estimating the introduction pathways and multispecies interactions among the pine wood nematode, its insect vectors, and hosts in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F.; Xing, Y.; Niu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zong, S.; Tao, J. Unveiling winter survival strategies: Physiological and metabolic responses to cold stress of Monochamus saltuarius larvae during overwintering. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 5656–5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.v.d.W.; Gomes Pereira, L.; Oliveira, B.R.F. Assessing Geometric and Radiometric Accuracy of DJI P4 MS Imagery Processed with Agisoft Metashape for Shrubland Mapping. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, V.; Thomasson, J.A.; Hardin, R.G.; Rajan, N.; Raman, R. Radiometric calibration of UAV multispectral images under changing illumination conditions with a downwelling light sensor. Plant Phenome J. 2024, 7, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Kootstra, G.; Khan, H.A. The impact of variable illumination on vegetation indices and evaluation of illumination correction methods on chlorophyll content estimation using UAV imagery. Plant Methods 2023, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Ding, M.; Ren, Z.; Bao, G.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Ma, H.; Lin, H. A LiDAR-Driven Effective Leaf Area Index Inversion Method of Urban Forests in Northeast China. Forests 2023, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xiang, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, J. An Improved Adaptive Grid-Based Progressive Triangulated Irregular Network Densification Algorithm for Filtering Airborne LiDAR Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalponte, M.; Coomes, D.A. Tree-centric mapping of forest carbon density from airborne laser scanning and hyperspectral data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, T.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Muhanmmad, F. The NDVI-CV Method for Mapping Evergreen Trees in Complex Urban Areas Using Reconstructed Landsat 8 Time-Series Data. Forests 2019, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.I.; Song, H.J.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, D.S.; Lee, C.Y.; Nam, Y.; Kim, J.B.; Park, Y.S. Dispersal Patterns of Pine Wilt Disease in the Early Stage of Its Invasion in South Korea. Forests 2017, 8, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melakeberhan, H.; Webster, J. Relationship of Bursaphelenchus-xylophilus population-density to mortality of pinus-sylvestris. J. Nematol. 1990, 22, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.T.; Moens, M.; Mota, M.; Li, H.; Kikuchi, T. Bursaphelenchus xylophilus: Opportunities in comparative genomics and molecular host–parasite interactions. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The Precision-Recall Plot Is More Informative than the ROC Plot When Evaluating Binary Classifiers on Imbalanced Datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Gupta, L. Training LSTMS with circular-shift epochs for accurate event forecasting in imbalanced time series. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Hussain, F.; Haque, M.M. Advances, challenges, and future research needs in machine learning-based crash prediction models: A systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 194, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Breiman, L. Using Random Forest to Learn Imbalanced Data; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R.; Huo, L.; Huang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, B.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, H.; Yang, L.; Ren, L.; et al. Early detection of pine wilt disease tree candidates using time-series of spectral signatures. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1000093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Fang, G.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y. Long-Term Spatiotemporal Pattern and Temporal Dynamic Simulation of Pine Wilt Disease. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, L.; Li, H.; Huang, H.; Luo, Y. Impact of stand- and landscape-level variables on pine wilt disease-caused tree mortality in pine forests. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.S.; Chung, Y.J.; Moon, Y.S. Hazard ratings of pine forests to a pine wilt disease at two spatial scales (individual trees and stands) using self-organizing map and random forest. Ecol. Inform. 2013, 13, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, Y. Feeding Preferences and Responses of Monochamus saltuarius to Volatile Components of Host Pine Trees. Insects 2022, 13, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, C.S.; Ayres, M.P.; Vallery, E.; Young, C.; Streett, D.A. Geographical variation in seasonality and life history of pine sawyer beetles Monochamus spp: Its relationship with phoresy by the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Agric. For. Entomol. 2014, 16, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).