Evaluating the Performance of the STEMMUS-SCOPE Model to Simulate SIF and GPP Under Drought Stress Using Tower-Based Observations of Maize

Highlights

- The STEMMUS-SCOPE model demonstrates higher accuracy than the SCOPE model in simulating SIF and GPP under drought stress.

- The simulation performance of STEMMUS-SCOPE under drought stress is validated;

- The potential of the STEMMUS-SCOPE model to investigate the SIF-GPP relationship under drought stress is demonstrated.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. STEMMUS-SCOPE Model

2.3. Calculation of Canopy Conductance

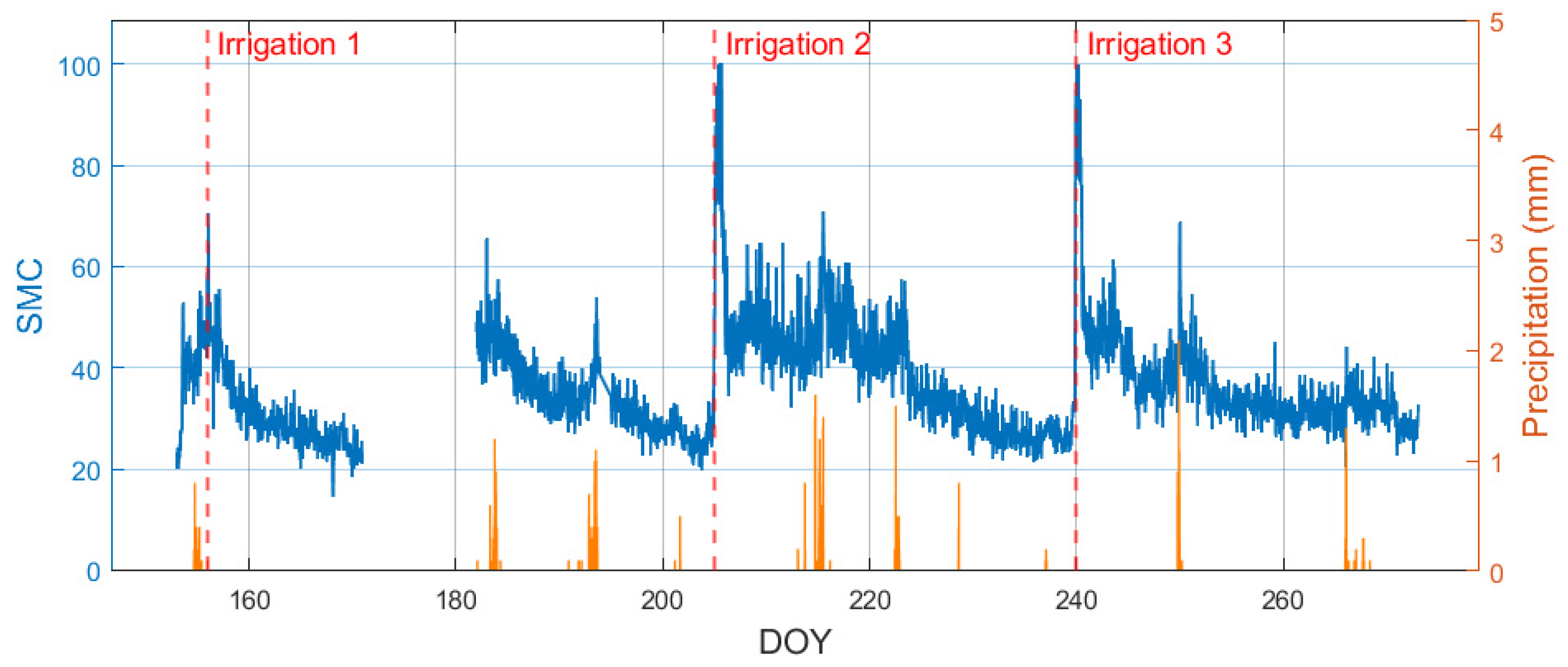

2.4. Irrigation and Changes in Soil Moisture in 2023

3. Results

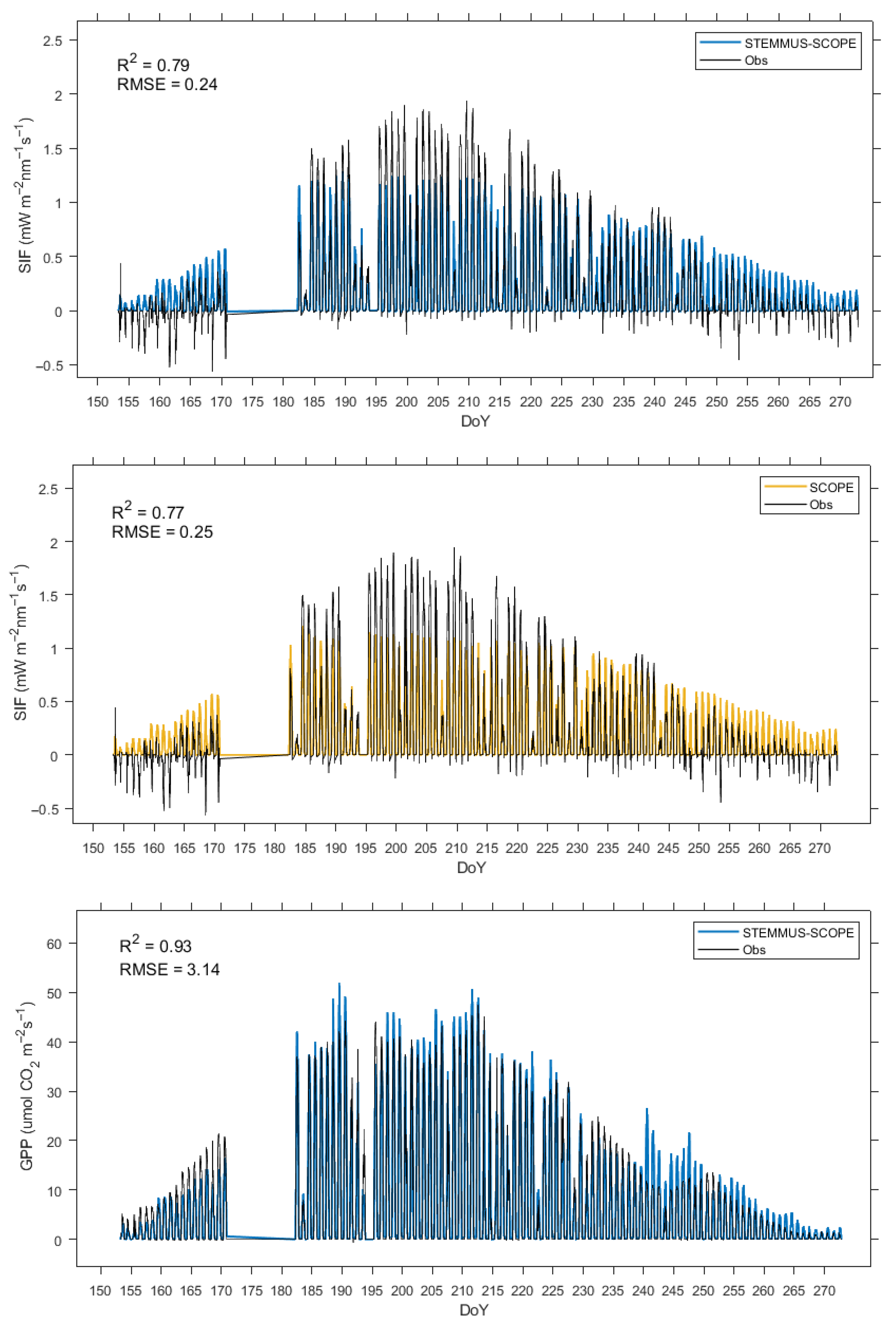

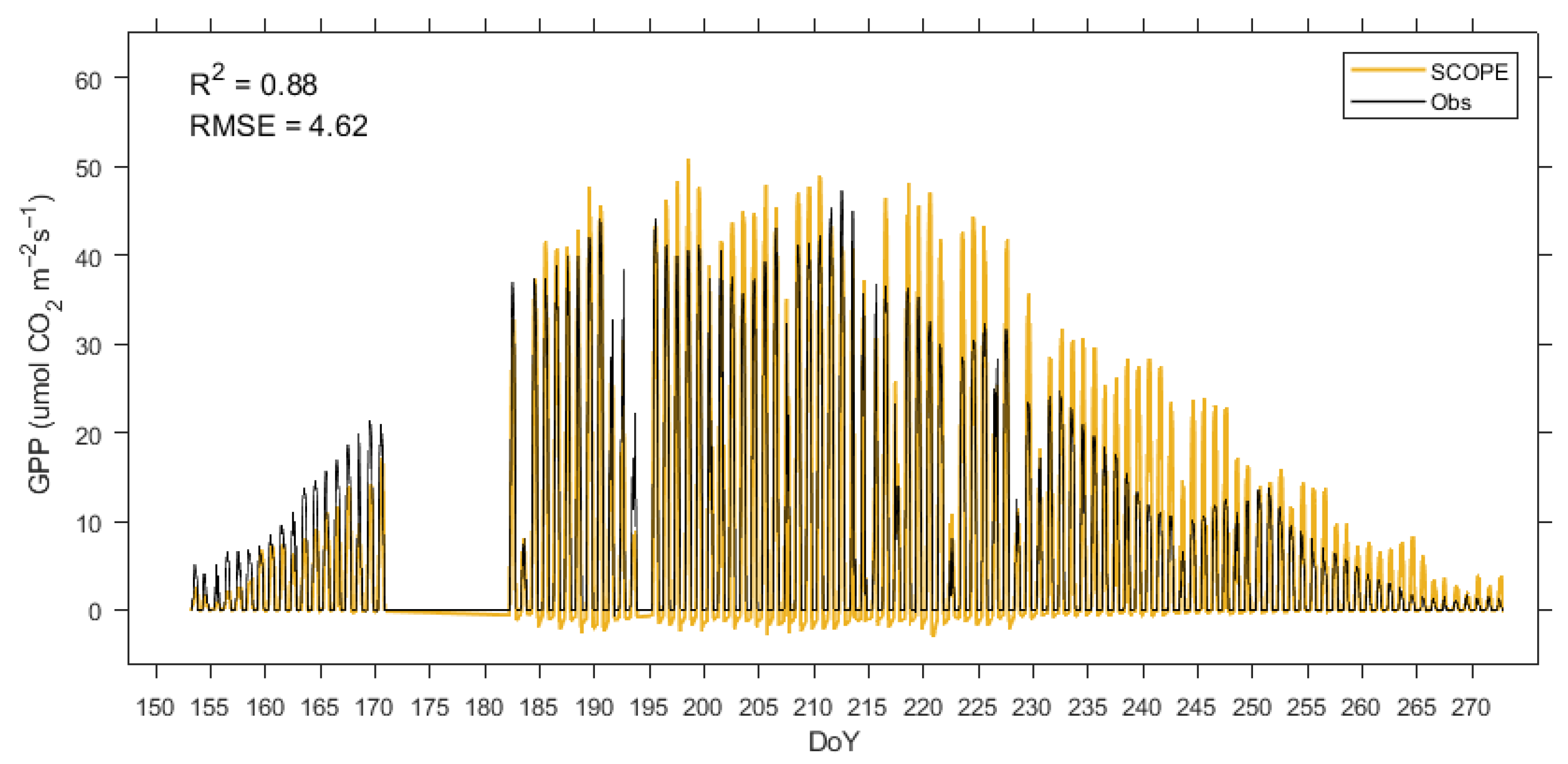

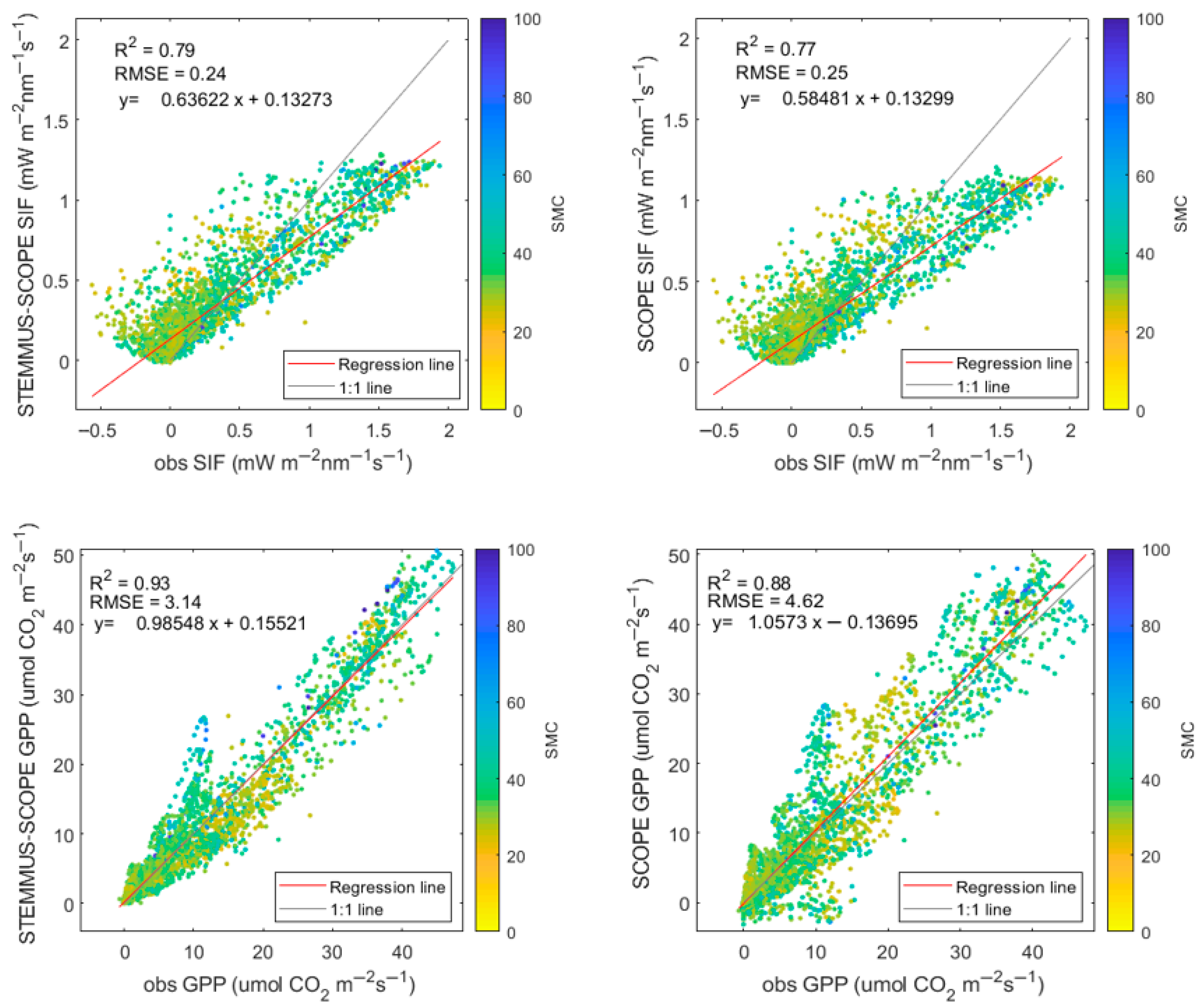

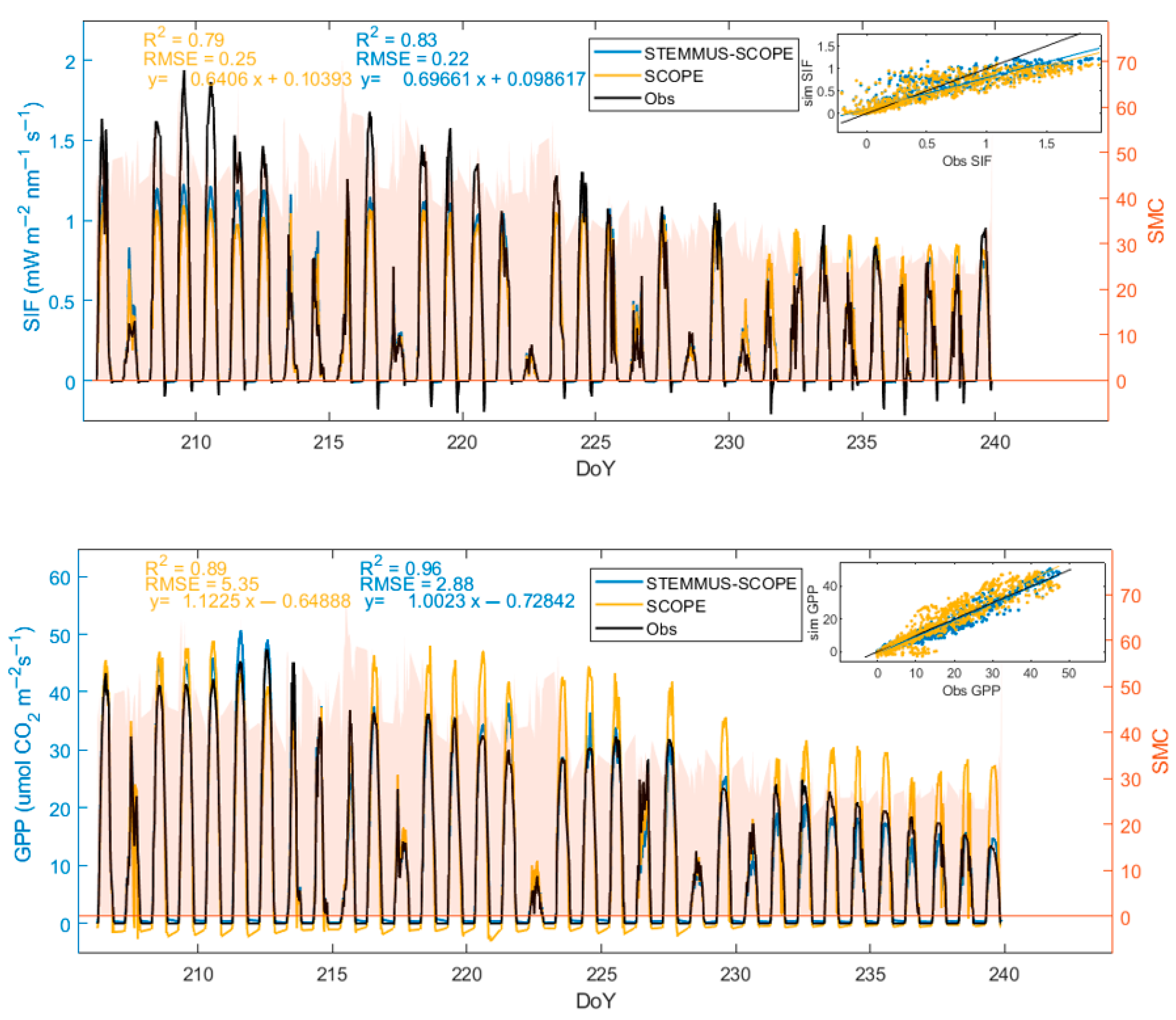

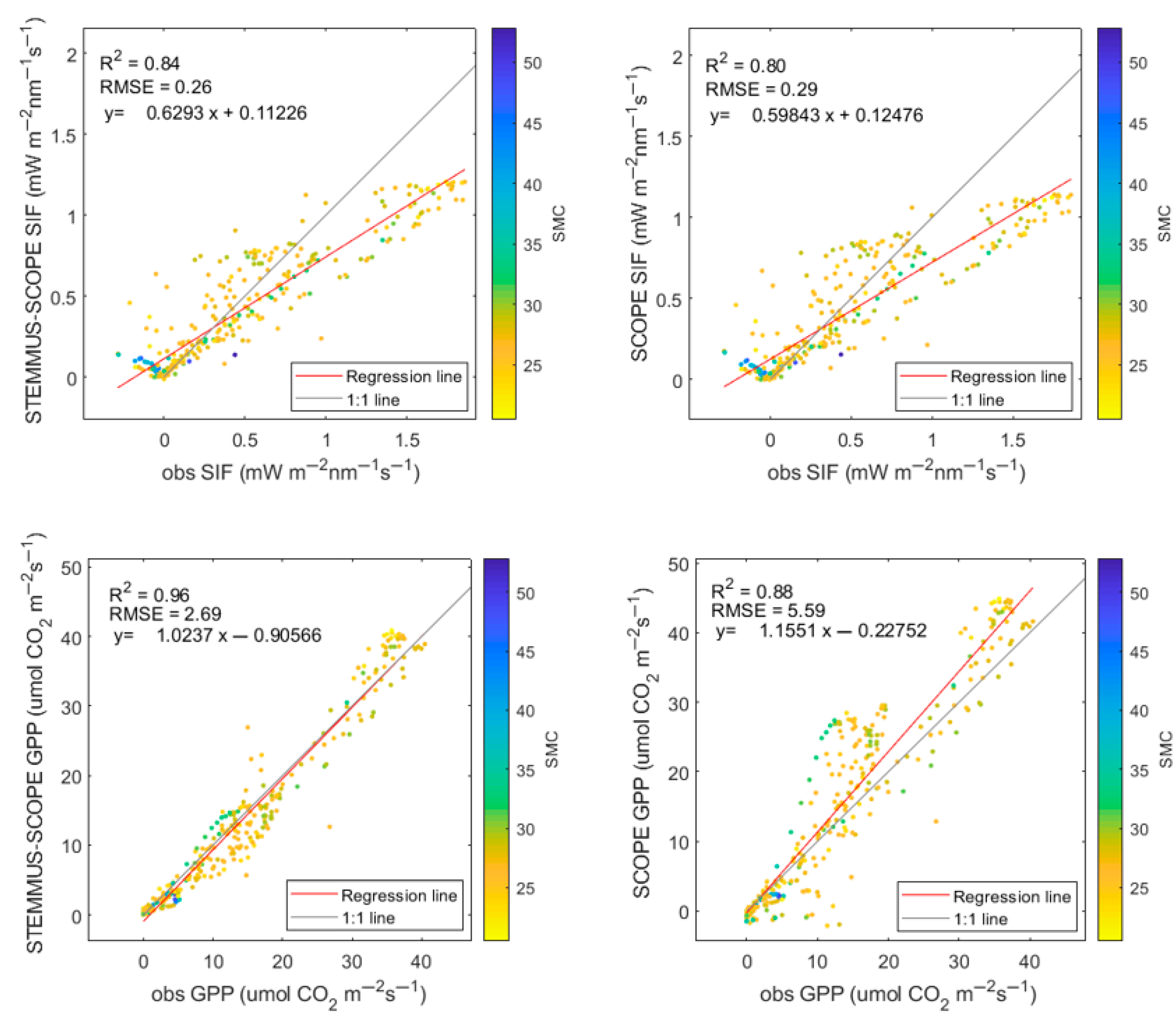

3.1. Comparison of the Accuracy of the STEMMUS-SCOPE and SCOPE Models for GPP and SIF Simulation

3.2. Performance of the STEMMUS-SCOPE Model in Tracking the Effects of Drought Stress

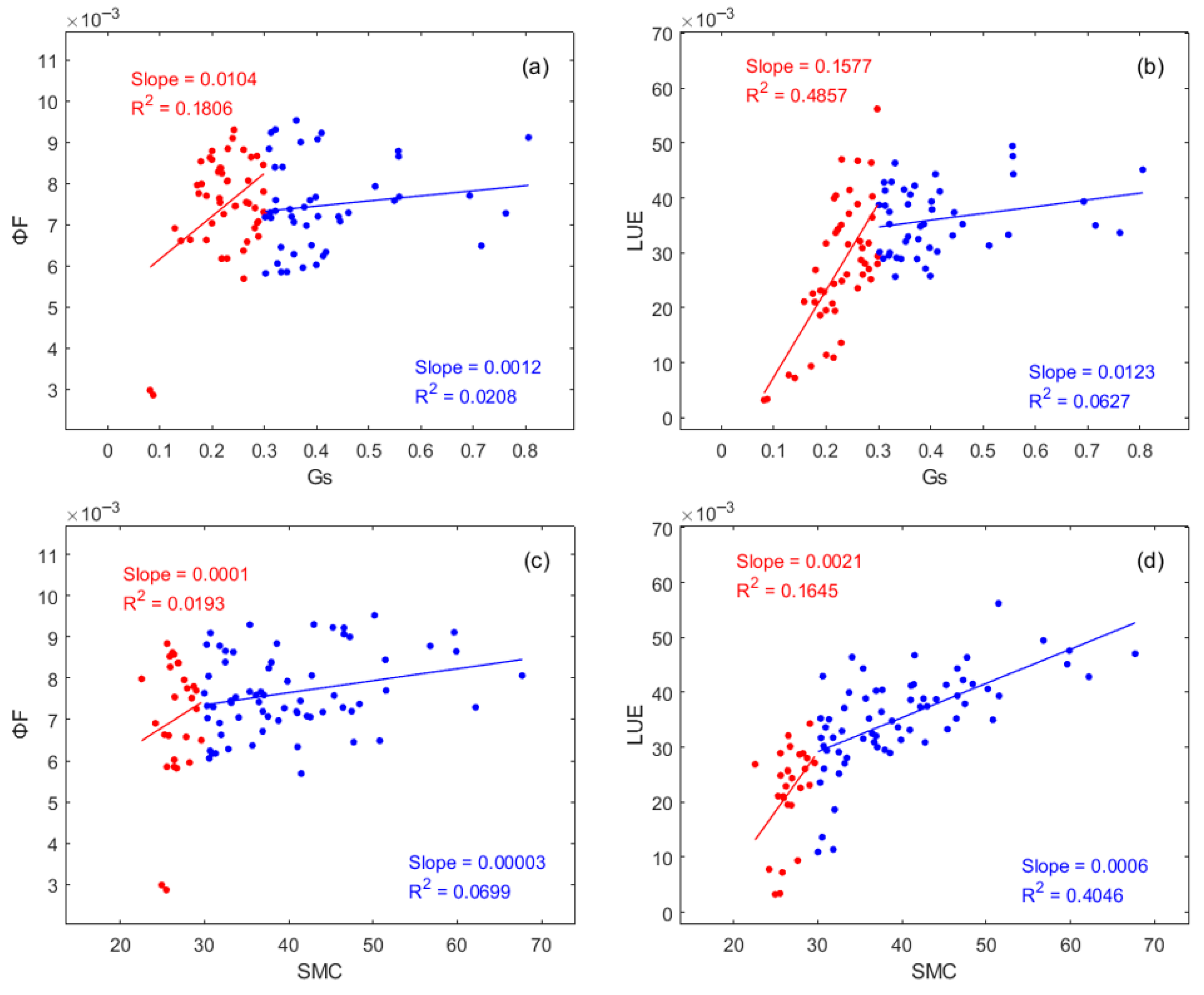

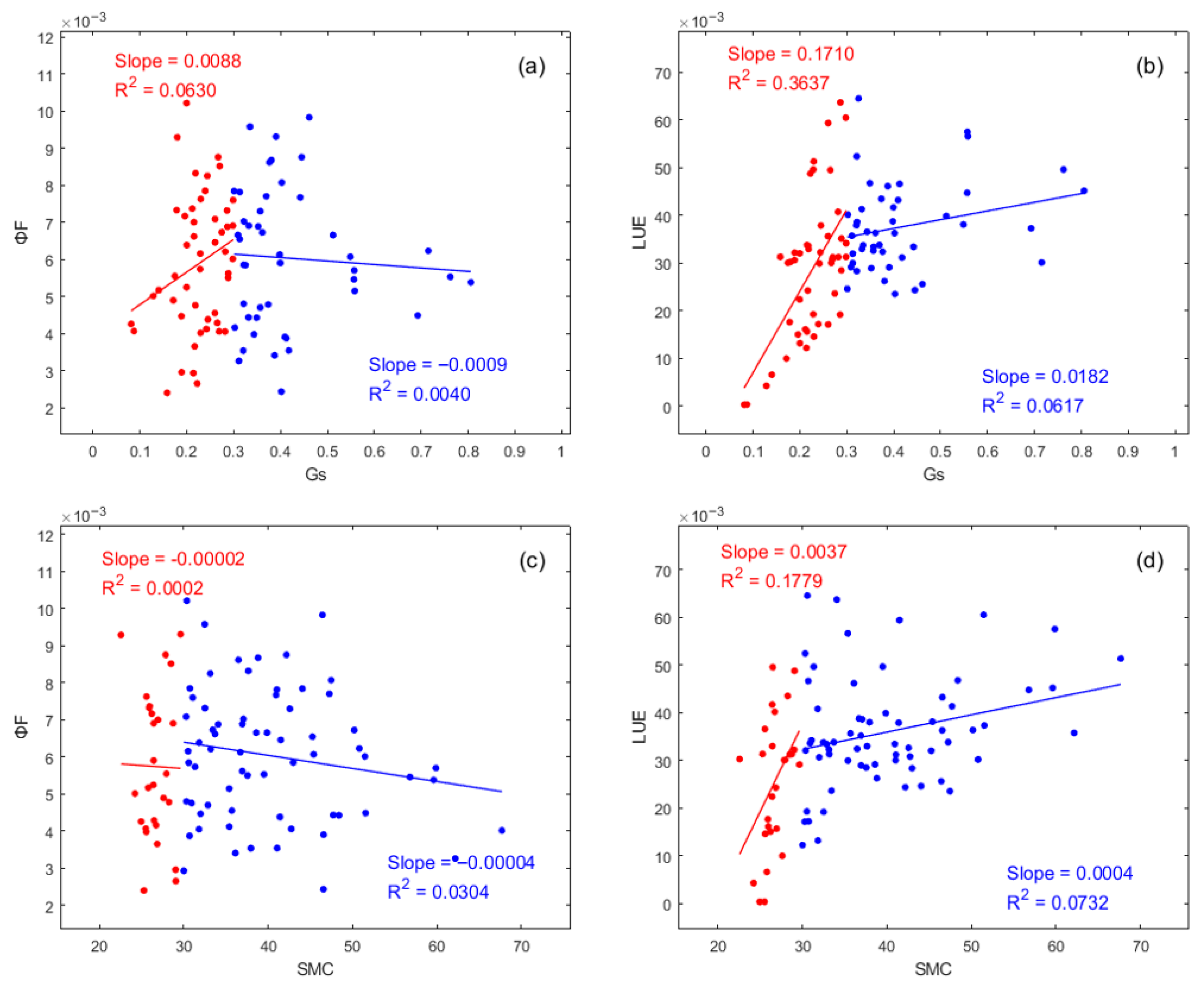

3.3. Responses of STEMMUS-SCOPE-Simulated ΦF and LUE to Varying SMC

4. Discussion

4.1. Performance of the STEMMUS-SCOPE Model for SIF and GPP Under Drought Stress

4.2. Advantages of STEMMUS-SCOPE in Quantifying Drought Effects on SIF and GPP

4.3. The Limitations of This Article

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Der Tol, C.; Berry, J.A.; Campbell, P.K.E.; Rascher, U. Models of Fluorescence and Photosynthesis for Interpreting Measurements of Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2014, 119, 2312–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, P.; Guanter, L.; Kobayashi, H.; Walther, S.; Yang, W. Assessing the Potential of Sun-Induced Fluorescence and the Canopy Scattering Coefficient to Track Large-Scale Vegetation Dynamics in Amazon Forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 204, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guan, L.; Liu, X. Directly Estimating Diurnal Changes in GPP for C3 and C4 Crops Using Far-Red Sun-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 232, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.L. Solar Radiation and Productivity in Tropical Ecosystems. J. Appl. Ecol. 1972, 9, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guanter, L.; Frankenberg, C.; Dudhia, A.; Lewis, P.E.; Gómez-Dans, J.; Kuze, A.; Suto, H.; Grainger, R.G. Retrieval and Global Assessment of Terrestrial Chlorophyll Fluorescence from GOSAT Space Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 121, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcar-Castell, A.; Malenovský, Z.; Magney, T.; Van Wittenberghe, S.; Fernández-Marín, B.; Maignan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Maseyk, K.; Atherton, J.; Albert, L.P.; et al. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Illuminates a Path Connecting Plant Molecular Biology to Earth-System Science. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Guanter, L.; Guan, K.; You, L.; Huete, A.; Ju, W.; Zhang, Y. Satellite Sun-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence Detects Early Response of Winter Wheat to Heat Stress in the Indian Indo-Gangetic Plains. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 4023–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Rascher, U. CMLR: A Mechanistic Global GPP Dataset Derived from TROPOMIS SIF Observations. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 4, 0127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrat, Z.; Magney, T.; Parazoo, N.C.; Grossmann, K.; Bowling, D.R.; Seibt, U.; Johnson, B.; Helgason, W.; Barr, A.; Bortnik, J. Diurnal and Seasonal Dynamics of Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence, Vegetation Indices, and Gross Primary Productivity in the Boreal Forest. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2022, 127, e2021JG006588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, C.; Fisher, J.B.; Worden, J.; Badgley, G.; Saatchi, S.S.; Lee, J.-E.; Toon, G.C.; Butz, A.; Jung, M.; Kuze, A.; et al. New Global Observations of the Terrestrial Carbon Cycle from GOSAT: Patterns of Plant Fluorescence with Gross Primary Productivity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L17706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechant, B.; Ryu, Y.; Badgley, G.; Köhler, P.; Rascher, U.; Migliavacca, M.; Zhang, Y.; Tagliabue, G.; Guan, K.; Rossini, M.; et al. NIRVP: A Robust Structural Proxy for Sun-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Photosynthesis across Scales. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 268, 112763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ryu, Y.; Dechant, B.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.S.; Kornfeld, A.; Berry, J.A. Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence Is Non-Linearly Related to Canopy Photosynthesis in a Temperate Evergreen Needleleaf Forest during the Fall Transition. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hou, R.; Tao, F. Interactive Effects of Different Warming Levels and Tillage Managements on Winter Wheat Growth, Physiological Processes, Grain Yield and Quality in the North China Plain. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 295, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Mao, J.; Ricciuto, D.; Lu, D.; Xiao, J.; Li, X.; Thornton, P.E.; Knapp, A.K. Seasonal Changes in GPP/SIF Ratios and Their Climatic Determinants across the Northern Hemisphere. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 5186–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Gu, L.; Rascher, U. Improving Estimates of Sub-Daily Gross Primary Production from Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence by Accounting for Light Distribution within Canopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 300, 113919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajewicz, P.A.; Zhang, C.; Atherton, J.; Van Wittenberghe, S.; Riikonen, A.; Magney, T.; Fernandez-Marin, B.; Plazaola, J.I.G.; Porcar-Castell, A. The Photosynthetic Response of Spectral Chlorophyll Fluorescence Differs across Species and Light Environments in a Boreal Forest Ecosystem. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 334, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcar-Castell, A.; Tyystjarvi, E.; Atherton, J.; van der Tol, C.; Flexas, J.; Pfuendel, E.E.; Moreno, J.; Frankenberg, C.; Berry, J.A. Linking Chlorophyll a Fluorescence to Photosynthesis for Remote Sensing Applications: Mechanisms and Challenges. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4065–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magney, T.S.; Bowling, D.R.; Logan, B.A.; Grossmann, K.; Stutz, J.; Blanken, P.D.; Burns, S.P.; Cheng, R.; Garcia, M.A.; Köhler, P.; et al. Mechanistic Evidence for Tracking the Seasonality of Photosynthesis with Solar-Induced Fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11640–11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, H.; Wu, G.; Guo, C.; Gu, L. SIF-Based GPP Modeling for Evergreen Forests Considering the Seasonal Variation in Maximum Photochemical Efficiency. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 344, 109814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Li, T.; Huang, K.; Gu, P.; Peng, H.; Chen, Z. Response of Vegetation Photosynthesis to the 2022 Drought in Yangtze River Basin by Diurnal Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2/3 Satellite Observations. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 5, 0445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhol, N.; Pandey, S.; Singh, V.P.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Tran, L.-S.P.; Tripathi, D.K. Link between Plant Phosphate and Drought Stress Responses. Research 2024, 7, 0405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ji, X.; Xu, M.; Zhao, G.; Zheng, Z.; Tang, Y.; Chen, N.; Zhu, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y. Influences of Drought on the Stability of an Alpine Meadow Ecosystem. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under Drought and Salt Stress: Regulation Mechanisms from Whole Plant to Cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galmés, J.; Medrano, H.; Flexas, J. Photosynthetic Limitations in Response to Water Stress and Recovery in Mediterranean Plants with Different Growth Forms. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.P.; Machado, E.C.; Silva, J.A.B.; Lagôa, A.M.M.A.; Silveira, J.A.G. Photosynthetic Gas Exchange, Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Some Associated Metabolic Changes in Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) during Water Stress and Recovery. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 51, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Mao, J.; Ricciuto, D.; Xiao, J.; Frankenberg, C.; Li, X.; Thornton, P.E.; Gu, L.; Knapp, A.K. Moisture Availability Mediates the Relationship between Terrestrial Gross Primary Production and Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence: Insights from Global-Scale Variations. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Du, S.; Ma, Y.; Liu, L. Effects of Drought on the Relationship Between Photosynthesis and Chlorophyll Fluorescence for Maize. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 11148–11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Peng, L.; Zhou, M.; Wei, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Dou, T.; Chen, J.; Wu, X. SIF-Based GPP Is a Useful Index for Assessing Impacts of Drought on Vegetation: An Example of a Mega-Drought in Yunnan Province, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; He, Q.-Q.; Yu, H. Response of Vegetation Productivity to Greening and Drought in the Loess Plateau Based on VIs and SIF. Forests 2024, 15, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, Y.; Wang, G. Detecting Drought-Induced GPP Spatiotemporal Variabilities with Sun-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence during the 2009/2010 Droughts in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qiao, N.; Huang, C.; Wang, S. Monitoring Drought Effects on Vegetation Productivity Using Satellite Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Tol, C.; Verhoef, W.; Timmermans, J.; Verhoef, A.; Su, Z. An Integrated Model of Soil-Canopy Spectral Radiances, Photosynthesis, Fluorescence, Temperature and Energy Balance. Biogeosciences 2009, 6, 3109–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, B.; van der Tol, C.; Yang, P.; Verhoef, W. Extending the SCOPE Model to Combine Optical Reflectance and Soil Moisture Observations for Remote Sensing of Ecosystem Functioning under Water Stress Conditions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 221, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, L.; Yang, P.; Van Der Tol, C.; Yu, Q.; Lü, X.; Cai, H.; Su, Z. Integrated Modeling of Canopy Photosynthesis, Fluorescence, and the Transfer of Energy, Mass, and Momentum in the Soil–Plant–Atmosphere Continuum (STEMMUS–SCOPE v1.0.0). Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 1379–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Su, Z.; Wan, L.; Wen, J. A Simulation Analysis of the Advective Effect on Evaporation Using a Two-Phase Heat and Mass Flow Model. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, 010701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ju, W.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, L.; Tang, J.; Zhu, X.; et al. ChinaSpec: A Network for Long-Term Ground-Based Measurements of Solar-Induced Fluorescence in China. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2020JG006042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Che, T.; Xiao, Q.; Ma, M.; Liu, Q.; Jin, R.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; et al. The Heihe Integrated Observatory Network: A Basin-Scale Land Surface Processes Observatory in China. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldocchi, D.D.; Hincks, B.B.; Meyers, T.P. Measuring Biosphere-Atmosphere Exchanges of Biologically Related Gases with Micrometeorological Methods. Ecology 1988, 69, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, L.; Guo, J.; Du, S.; Liu, X. Upscaling Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence from an Instantaneous to Daily Scale Gives an Improved Estimation of the Gross Primary Productivity. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guanter, L.; Liu, L.; Damm, A.; Malenovský, Z.; Rascher, U.; Peng, D.; Du, S.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.-P. Downscaling of Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence from Canopy Level to Photosystem Level Using a Random Forest Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 110772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Lamb, D.W.; Stanley, J.N. The Impact of Solar Illumination Angle When Using Active Optical Sensing of NDVI to Infer fAPAR in a Pasture Canopy. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 202, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Peng, Y.; Huemmrich, K.F. Relationship between Fraction of Radiation Absorbed by Photosynthesizing Maize and Soybean Canopies and NDVI from Remotely Sensed Data Taken at Close Range and from MODIS 250 m Resolution Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 147, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Verhoef, A.; Vereecken, H.; Ben-Dor, E.; Veldkamp, T.; Shaw, L.; Ploeg, M.V.D.; Wang, Y.; Su, Z. Monitoring and Modeling the Soil-Plant System Toward Understanding Soil Health. Rev. Geophys. 2025, 63, e2024RG000836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Lin, S.; Huete, A.; Liu, L.; Croft, H.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. A Novel Red-Edge Spectral Index for Retrieving the Leaf Chlorophyll Content. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 2771–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.; Curran, P.J. The MERIS Terrestrial Chlorophyll Index. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 5403–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, X.; Jing, X.; Geng, L.; Che, T.; Liu, L. Enhancing Leaf Area Index Estimation for Maize with Tower-Based Multi-Angular Spectral Observations. Sensors 2023, 23, 9121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, W.; Bach, H. Coupled Soil-Leaf-Canopy and Atmosphere Radiative Transfer Modeling to Simulate Hyperspectral Multi-Angular Surface Reflectance and TOA Radiance Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 109, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemeur, R.; Blad, B.L. A Critical Review of Light Models for Estimating the Shortwave Radiation Regime of Plant Canopies. In Developments in Agricultural and Managed Forest Ecology; Stone, J.F., Ed.; Plant Modification for More Efficient Water Use; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1975; Volume 1, pp. 255–286. [Google Scholar]

- Penman, H.L. Natural Evaporation from Open Water, Bare Soil and Grass. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1948, 193, 120–145. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Gentine, P.; Lin, C.; Zhou, S.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, C. A Simple and Objective Method to Partition Evapotranspiration into Transpiration and Evaporation at Eddy-Covariance Sites. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 265, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Gentine, P.; Huang, Y.; Guan, K.; Kimm, H.; Zhou, S. Diel Ecosystem Conductance Response to Vapor Pressure Deficit Is Suboptimal and Independent of Soil Moisture. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 250–251, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, F.; Yang, S.; Chen, X. Soil Water Dynamics and Water Use Efficiency in Spring Maize (Zea mays L.) Fields Subjected to Different Water Management Practices on the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Wang, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X. Effects of Soil Water Deficit at Different Growth Stages on Maize Growth, Yield, and Water Use Efficiency under Alternate Partial Root-Zone Irrigation. Water 2021, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Yu, D.; Wu, H.; Qiao, C.; Van Der Tol, C.; Du, L.; Su, Z. Understanding the Effects of Revegetated Shrubs on Fluxes of Energy, Water, and Gross Primary Productivity in a Desert Steppe Ecosystem Using the STEMMUS–SCOPE Model. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durigon, A.; de Jong van Lier, Q. Canopy Temperature versus Soil Water Pressure Head for the Prediction of Crop Water Stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 127, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; An, S.; Tang, J. Comparison of Phenology Estimated from Reflectance-Based Indices and Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence (SIF) Observations in a Temperate Forest Using GPP-Based Phenology as the Standard. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idso, S.B. Non-Water-Stressed Baselines: A Key to Measuring and Interpreting Plant Water Stress. Agric. Meteorol. 1982, 27, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounis, A.; Evain, S.; Flexas, J.; Tosti, S.; Moya, I. Adaptation of a PAM-Fluorometer for Remote Sensing of Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Photosynth. Res. 2001, 68, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Medrano, H. Drought-Inhibition of Photosynthesis in C3 Plants: Stomatal and Non-Stomatal Limitations Revisited. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Duursma, R.A.; Medlyn, B.E.; Kelly, J.W.G.; Prentice, I.C. How Should We Model Plant Responses to Drought? An Analysis of Stomatal and Non-Stomatal Responses to Water Stress. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 182–183, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Han, J.; Wood, J.D.; Chang, C.Y.-Y.; Sun, Y. Sun-Induced Chl Fluorescence and Its Importance for Biophysical Modeling of Photosynthesis Based on Light Reactions. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmond, B.; Badger, M.; Maxwell, K.; Björkman, O.; Leegood, R. Too Many Photons: Photorespiration, Photoinhibition and Photooxidation. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, L.T.; Shi, H.; Lerdau, M.T.; Yang, X. Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Short-Term Photosynthetic Response to Drought. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farquhar, G.D.; von Caemmerer, S.; Berry, J.A. Models of Photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Description | Symbol | Unit | Value/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | Leaf chlorophyll content | Cab | µg cm−2 | Inversion |

| Leaf carotenoid content | Cca | µg cm−2 | 0.25 Cab | |

| Leaf dry matter content | Cdm | g cm−1 | 0.012 | |

| Senescent material content | Cs | / | 0 | |

| Ball–Berry stomatal conductance parameter | m | / | 6.8, 10 | |

| Canopy | Leaf area index | LAI | m2 m−2 | Inversion |

| Leaf inclination distribution function | LIDFa | / | −0.35 | |

| Leaf inclination distribution function | LIDFb | / | −0.15 | |

| Maximum carboxylation rate | Vcmax | 60–80 | ||

| Meteorology | Incoming shortwave radiation | Rin | W m−2 | Measurement |

| Air temperature | Ta | °C | Measurement | |

| Wind speed | u | m s−1 | Measurement | |

| Air vapor pressure | ea | hPa | Measurement | |

| CO2 concentration | Ca | µmol m−3 | Measurement | |

| Incoming longwave radiation | Rli | W m−2 | Measurement | |

| Relative humidity | RH | % | Measurement | |

| Relative humidity | VPD | hPa | Measurement | |

| Air pressure | P | hPa | Measurement | |

| Soil moisture content | SMC | % | Measurement | |

| precipitation | Rain | mm | Measurement |

| Year | SIF | GPP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMMUS-SCOPE | SCOPE | STEMMUS-SCOPE | SCOPE | |||||

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |

| 2017 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 5.93 | 0.71 | 7.64 |

| 2018 | 0.62 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.90 | 5.75 | 0.88 | 6.82 |

| 2019 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.89 | 4.96 | 0.86 | 6.85 |

| 2020 | 0.56 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.86 | 5.18 | 0.83 | 5.77 |

| 2021 | 0.83 | 0.24 | 0.83 | 0.32 | 0.90 | 4.77 | 0.86 | 5.60 |

| 2022 | 0.74 | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.89 | 4.78 | 0.86 | 6.17 |

| 2023 | 0.79 | 0.24 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 0.93 | 3.14 | 0.88 | 4.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, L. Evaluating the Performance of the STEMMUS-SCOPE Model to Simulate SIF and GPP Under Drought Stress Using Tower-Based Observations of Maize. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243931

Li M, Liu X, Liu L. Evaluating the Performance of the STEMMUS-SCOPE Model to Simulate SIF and GPP Under Drought Stress Using Tower-Based Observations of Maize. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243931

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Mengchen, Xinjie Liu, and Liangyun Liu. 2025. "Evaluating the Performance of the STEMMUS-SCOPE Model to Simulate SIF and GPP Under Drought Stress Using Tower-Based Observations of Maize" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243931

APA StyleLi, M., Liu, X., & Liu, L. (2025). Evaluating the Performance of the STEMMUS-SCOPE Model to Simulate SIF and GPP Under Drought Stress Using Tower-Based Observations of Maize. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3931. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243931