Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We propose RSDB-Net, a novel network for rotation-aware ship detection in remote sensing.

- We designed STCBackbone that uniquely fuses Swin Transformer and CNN via FCCM.

- We developed RCFHead for cross-branch feature fusion to boost orientation robustness.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The eFPN with learnable transposed convolutions is suitable for adaptive multi-scale fusion.

- RSDB-Net achieves 89.13% AP-ship on DOTA-v1.0 and 90.10% AP on HRSC2016.

Abstract

Ship detection in remote sensing imagery is hindered by cluttered backgrounds, large variations in scale, and random orientations, limiting the performance of detectors designed for natural images. We propose RSDB-Net, a Rotation-Sensitive Dual-Branch Detection Network that introduces innovations in feature extraction, fusion, and detection. The Swin Transformer–CNN Backbone (STCBackbone) combines a Swin Transformer for global semantics with a CNN branch for local spatial detail, while the Feature Conversion and Coupling Module (FCCM) aligns and fuses heterogeneous features to handle multi-scale objects, and a Rotation-sensitive Cross-branch Fusion Head (RCFHead) enables bidirectional interaction between classification and localization, improving detection of randomly oriented targets. Additionally, an enhanced Feature Pyramid Network (eFPN) with learnable transposed convolutions restores semantic information while maintaining spatial alignment. Experiments on DOTA-v1.0 and HRSC2016 show that RSDB-Net performs better than the state of the art (SOTA), with mAP-ship values of 89.13% and 90.10% (+5.54% and +44.40% over the baseline, respectively), and reaches 72 FPS on an RTX 3090. RSDB-Net also demonstrates strong generalization and scalability, providing an effective solution for rotation-aware ship detection.

1. Introduction

Ships are pivotal in maritime transport, global trade, and the exploitation of offshore resources. Consequently, accurate detection of ships in optical remote sensing imagery is crucial for both civilian and defense-related applications. Recent advances in computer vision and remote sensing have positioned deep learning as the leading paradigm in ship detection.

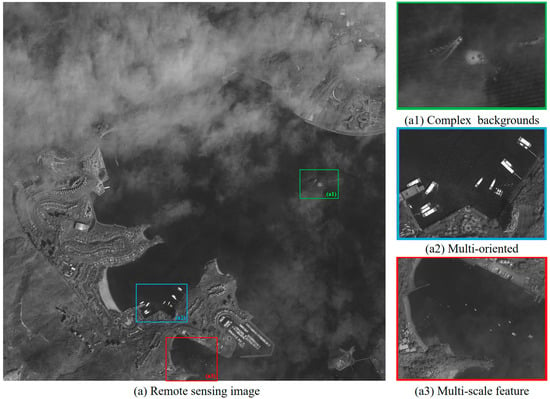

As shown in Figure 1a, satellite imagery captured from several hundred kilometers above the Earth often contains complex backgrounds (Figure 1(a1)), and ships exhibit multiple orientations (Figure 1(a2)) and sizes (Figure 1(a3)). These factors contribute to elevated false positive and negative rates, hindering detection accuracy. To overcome these challenges, various deep learning-based methods have been developed to address the above issues in remote sensing scenes.

Figure 1.

A remote sensing image (a) and three representative challenges (a1–a3) in ship detection. Early ship detection techniques relied on handcrafted features and traditional classifiers but struggled under complex maritime conditions.

With the rise of CNNs, deep learning-based detectors have become dominant in remote sensing ship detection. However, downsampling and pooling operations reduce spatial resolution and compromise global context modeling. Even with extended receptive fields, CNNs struggle to capture long-range dependencies, limiting semantic comprehension, particularly in remote sensing scenarios where object localization relies heavily on the global context. As a result, CNNs often underperform in complex scenes with diverse object orientations.

Recently, Transformer architectures powered by self-attention [1] have shown remarkable ability in modeling complex spatial transformations and long-range dependencies, and have become essential for global feature representation and multi-scale fusion in computer vision.

However, fine-grained details are often not considered in the global encoding strategy of Transformers, reducing foreground–background separability in complex maritime scenes and thus limiting detection robustness. CNNs focus on local receptive fields, using stacked convolutions to extract fine-grained details and high-frequency patterns. In contrast, the ST features a hierarchical structure to capture complex spatial relationships and long-range dependencies, emphasizing global semantic representation. These architectures are thus complementary: CNNs excel at local feature extraction, while Transformers are adept at modeling global contexts.

CNN–Transformer detectors attempt to combine both advantages; however, most existing hybrid architectures concatenate features and perform linear fusion, which leads to misaligned feature distributions between CNN and Transformer streamsand they still exhibit weak robustness and limited generalization. Moreover, conventional necks, such as the standard Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [2], are not optimized for multi-scale and multi-orientation ship targets, and their feature fusion performance is poor for slender vessels with large scale ranges. Furthermore, most detection heads still use a decoupled design, such as RoITransformer [3], and there is no interaction between classification and localization branches. This design limits feature sharing and reduces detection accuracy.

Therefore, the key challenge is not simply the combination of CNNs and Transformers; the real difficulty lies in designing a tightly coupled architecture that supports stable local–global fusion. This architecture must also provide a consistent multi-scale representation and should enable effective rotation-aware feature interaction. Existing detectors do not adequately address these requirements.

To address these issues, we propose RSDB-Net, a novel dual-branch parallel Transformer–CNN architecture tailored to multi-oriented ship detection. RSDB-Net features three coordinated modules: the STCBackbone for global–local complementary feature representation, the FCCM for stable cross-branch alignment and coupling, and the RCFHead with rotation-sensitive interaction between classification and regression branches. Together with an enhanced eFPN that preserves high-resolution details through adaptive upsampling, these components enable robust multi-scale and multi-orientation detection.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We present a tightly coupled dual-branch backbone, Swin Transformer–CNN Backbone (STCBackbone) that features integrated ST and CNN branches. Through residual feature injection and the proposed FCCM, the model effectively aligns and enhances local and global features, enabling robust multi-scale representation of ships in complex remote sensing scenes.

- We propose a rotation-sensitive RCFHead that incorporates cross-branch feature interaction and weight sharing between classification and regression tasks, leading to improved detection accuracies and orientation robustness.

- We develop an eFPN equipped with learnable transposed convolutions for adaptive upsampling. This design helps preserve fine-grained spatial details while promoting consistent and efficient multi-scale feature fusion.

- Extensive experiments demonstrate that RSDB-Net consistently outperforms existing methods in capturing detailed spatial structures and in detection performance under complex conditions.

2. Related Work

Existing ship detection methods in remote sensing can be grouped into three major categories.

2.1. Traditional Machine Learning Approaches

Earlier works relied on handcrafted geometric or texture descriptors combined with classical classifiers, such as the methods proposed by Lin [4] and Yang [5]. Although simple and interpretable, these methods are highly sensitive to illumination, sea clutter, and viewpoint changes, resulting in limited robustness in real maritime scenes.

2.2. CNN-Based Detectors

With the success of deep learning, CNN-based frameworks have become mainstream due to their ability to capture local spatial structures. CNN-based networks rely on localized convolutional receptive fields to effectively capture neighborhood information and local structural features. Building on this foundation, a variety of ship detection networks have been designed, for instance, AF2Det [6], which features attention-enhanced feature fusion to support anchor-free detection in complex maritime backgrounds. In another method, VODet [7], a vector decomposition strategy is proposed to robustly regress object orientation, overcoming the periodicity problem inherent in angle representation. FEADet [8] leverages both feature enhancement and alignment modules to strengthen geometric consistency, while ReBiDet [9] features a rotation-equivariant bidirectional feature fusion network, and RA2DC-Nett [10] combines residual convolution and deformable convolution to improve anchor-free detection adaptability.

However, CNNs inherently lack global receptive fields and struggle to fully exploit long-range dependencies, often leading to performance degradation in complex, cluttered environments.

2.3. Transformer-Based Ship Detection

The Vision Transformer [11] first demonstrated that pure Transformer-based models could rival or surpass CNNs in image classification. Building on this, hierarchical sliding-window attention was introduced in Swin Transformer [12] to reduce computational costs, enabling success in downstream tasks such as object detection. Building on these advances, Transformer-based models have been extended to remote sensing ship detection. Ship-DETR [13] adopts an end-to-end DETR [14] network to eliminate anchor boxes and improve multi-scale detection, though it struggles with slow convergence and poor performance on ultra-small objects. Popeye [15] leverages vision–language alignment for cross-domain adaptability, yet still faces challenges in regressing orientation angles accurately. These models have advanced the accuracy, efficiency, and adaptability of detection in this field. In the broader field of remote sensing segmentation, state-of-the-art models such as Swin-UNet [16] and DPT [17] have demonstrated the potential of Transformer-driven architectures in achieving superior multi-scale understanding and generalization.

Nevertheless, their global attention mechanisms often reduce the fine-grained spatial detail, and foreground–background separation is further compromised. Such deficiencies are particularly detrimental for detecting thin or small ship targets.

To combine local detail extraction and global modeling, hybrid CNN–Transformer architectures [18,19] have been proposed (e.g., FSCM [20], CrossFormer++ [21], WetMapFormer [22], PatchOut [23]). These networks generally outperform pure CNNs or Transformers. However, most hybrids rely on naïve concatenation or linear fusion, resulting in misaligned feature distributions and insufficient cross-branch complementary learning.

As shown in Table 1, despite significant progress, existing frameworks still struggle to simultaneously achieve (1) strong global–local complementarity, (2) robust rotation-aware feature interaction, and (3) consistent multi-scale fusion. These limitations motivated the development of RSDB-Net, which features a tightly coupled Transformer–CNN backbone, a rotation-sensitive detection head, and an enhanced FPN tailored for multi-scale, multi-oriented ship detection. The proposed network achieves efficient multi-scale feature fusion and cross-branch interaction, significantly enhancing ship detection accuracy in complex remote sensing scenes.

Table 1.

Representative methods and comparison with RSDB-Net.

3. Materials and Methods

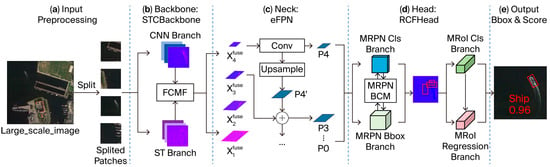

The overall architecture of RSDB-Net is shown in Figure 2. To handle large-scale remote sensing images, the input is first split into smaller patches by the preprocessing module (a). These are then processed by the STCBackbone (b), where local and global features are jointly enhanced via residual injection and FCCM. The fused features are passed to eFPN (c), which employs learnable transposed convolutions to restore spatial details and support scale-aware feature fusion. RCFHead (d) receives multi-scale features and performs classification and regression. The Mixed Region Proposal Network (MRPN) generates proposals, which are represented by the red rectangle box in Figure 2d, and the Mixed Region of Interest (MRoI) module then refines them through cross-branch interaction. Finally, the output (e) maps the predicted boxes and categories back to the original image to generate the results.

Figure 2.

Overview of RSDB-Net.

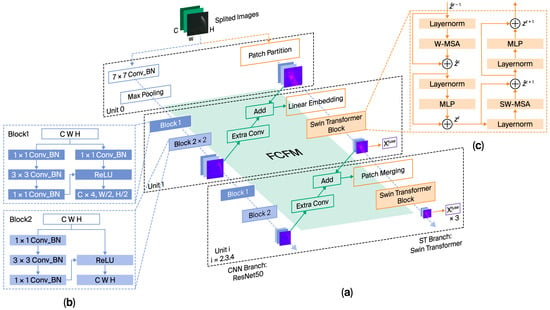

3.1. Feature Extraction Backbone: STCBackbone

We propose STCBackbone, a dual-branch architecture in which FCCM injects CNN features into the ST stream, preserving the global context and enhancing sensitivity to textures and edges. As shown in Figure 3a, STCBackbone adopts a symmetric dual-path design with five hierarchical units (Units 0–4), each generating multi-level outputs. This design simultaneously preserves fine-grained local cues and high-level semantics. The CNN branch follows a residual structure Figure 3b for spatial detail extraction, where Block 1 and Block 2 are composed of 1 × 1, 3 × 3, and 1 × 1 convolutions with an expansion ratio of 4 and a stride of 2 in the downsampling layer. The ST branch employs SW-MSA (Figure 3c) for efficient global modeling, with a window size of 7 and 12 attention heads. Both branches have synchronized resolutions, enabling effective spatial–semantic alignment through the FCCM. Furthermore, residual connections are explicitly implemented through element-wise additions within the FCCM, facilitating seamless cross-branch feature fusion while ensuring stable gradient propagation and consistent spatial–semantic alignment across stages. Detailed stage-wise configurations are provided in Table 2. In each unit, the CNN and ST branches operate at the same spatial resolution but produce inherently incompatible feature formats: the CNN outputs C × H0 × W0 feature maps, while the ST encodes inputs as patch embeddings of (K + 1) × E structure, leading to dimensional misalignment. The CNN branch has a ResNet-50 [24] bottleneck design [1 × 1, Cm]→[3 × 3, Cm, s]→[1 × 1, 4Cm], while the Swin Transformer (ST) branch follows the Swin-T configuration, with hierarchical embedding dimensions of {96,192,384,768}. A Feature Conversion and Coupling Module (FCCM) that performs channel alignment via 1 × 1 convolution and fuses CNN–Transformer features through residual coupling in token space is integrated into each stage. The outputs (C1–C4) are then forwarded to the neck (FPN or eFPN) for multi-scale aggregation. This design ensures consistent spatial alignment and balanced semantic–structural representation across stages.

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of STCBackbone: (a) Data flow between the CNN branch (blue), the ST branch (orange), and the FCCM (green). The backbone is organized into five hierarchical units (Units 0–4). (b) Internal configurations of the CNN: Blocks 1 and 2. (c) ST block, consisting of W-MSA, SW-MSA, multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), and layer normalization.

Table 2.

The STCBackbone architecture.

We design the FCCM as an intermediate transformation block that performs channel re-projection and token reshaping. Within the FCCM (Units 1–4), a learnable 1 × 1 convolutional mapping is applied to the CNN output , producing aligned features:

This mapping unifies the channel dimensions of CNN and ST streams, enabling feature-level compatibility.

To match the ST’s sequential processing format, the aligned CNN features are reshaped into token sequences , directly corresponding to Swin tokens . This one-to-one alignment supports efficient token-wise coupling. We adopt residual-style coupling, where the CNN tokens are added elementwise to the ST tokens:

This coupling maintains the identity of the Swin tokens while integrating complementary local features from the CNN stream, and the residual design supports efficient information flow and gradient propagation, which is beneficial in deep hierarchies. The fused features are then passed to the next ST unit for progressive cross-branch interaction. This coupling strategy is applied at all hierarchical levels to ensure consistent integration of global semantics and fine-grained spatial details throughout the backbone.

The pseudocode is shown in the following (Algorithm 1):

| Algorithm 1: FCCM | |

| Input: Output: Fused for Unit i. Step 1: Channel Alignment and Flattening 1. For each Unit i = 1, 2, 3,4: 2. Project CNN features via 1 × 1 convolution to match Swin dimensionality: Step 2: Reshape CNN Features into a Token Sequence 4. Flatten spatial dimensions and permute to reorder (B, C, H, W) → (B, H, W, C) for tokenization: 5. | |

| Comment: This operation ensures that the spatial tokens from the CNN branch share the same ordering and dimension layout as Swin tokens, facilitating token-wise fusion. | |

| Step 3: Additive Coupling 6. Retrieve ST token sequence: 7. 8. Fuse aligned CNN and Swin features: 9. Step 4: Forward Propagation 10. Pass to the next ST Unit. | |

3.2. Feature Fusion Neck: eFPN

Multi-scale feature fusion is essential for detecting remote sensing objects of diverse scales and orientations. The classical FPN combines semantic and spatial features via fixed interpolation, but its limited adaptability often leads to degraded features and reduced accuracy, especially for rotated ships.

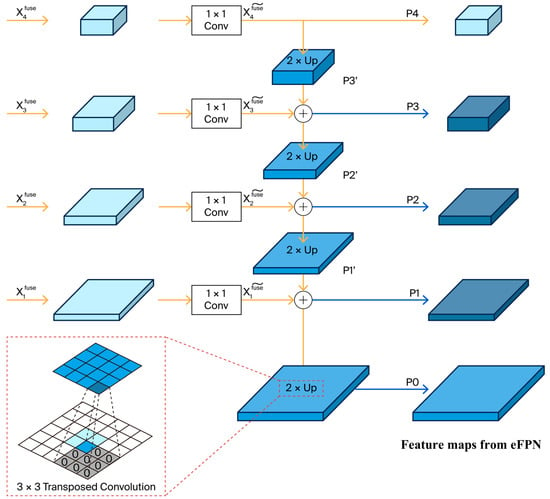

To address these limitations, we propose eFPN, as illustrated in Figure 4. eFPN employs learnable transposed convolutions for adaptive upsampling and introduces a high-resolution feature map (P0) to enhance spatial details, preserving the fine-grained structure crucial for multi-scale rotated ship detection.

Figure 4.

Overall architecture of the proposed eFPN with learnable transposed convolution-based adaptive upsampling (s = 1, p = 0, k = 3, op = 1) and an extra high-resolution level (P0). In the 3 × 3 transposed convolution: blue indicates the output feature map, light blue marks the selected output position, and grey denotes the zero-inserted inputs.

eFPN retains the lateral residual connections of the original FPN while refining the top-down pathway via trainable upsampling. Multi-scale features to are extracted at decreasing resolutions. Starting from , features are upsampled and processed via 1 × 1 convolutions and then fused with the next lower stage to form P3′, P3, and so on, down to P0. To ensure efficient fusion, features are projected to a unified channel dimension via

where is the batch size and are spatial dimensions. In the top-down pathway, each higher-level feature is upsampled and fused with its lateral counterpart to form the pyramid output:

Moreover, eFPN adopts learnable transposed convolutions to improve adaptability. The output height is determined by

where s, k, p, and op denote the stride, kernel size, padding, and output padding, respectively. To avoid checkerboard artifacts and align with lateral features, we set s = 1, p = 0, k = 3, and op = 1. To enlarge the output feature map, 3 pixels are added per dimension, avoiding grid artifacts typically observed when using a stride of 2. This design helps preserve boundary information and ensures smooth fusion between adjacent feature pyramid levels, particularly beneficial for detecting ultra-small ships.

Compared with common bilinear interpolation followed by a 3 × 3 convolution, the learnable transposed convolution in eFPN provides a trainable upsampling mechanism that adaptively adjusts kernel weights according to the input feature distribution. This learnability enables eFPN to restore spatial structures more accurately and achieve finer alignment between lateral and top-down pathways. Consequently, eFPN achieves adaptive upsampling with higher flexibility and precision than fixed interpolation-based approaches.

By preserving structural details across scales, eFPN improves resolution consistency, adaptability, and robustness in complex remote sensing scenarios. The learnable upsampling modules introduce less than 1% additional parameters but significantly enhance spatial precision and semantic representation. As a result, eFPN consistently outperforms conventional FPNs in multi-scale ship detection, especially under challenging conditions.

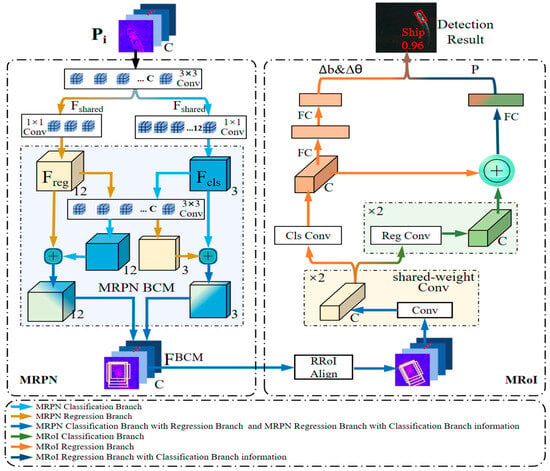

3.3. Detection Head: RCFHead

Most two-stage detectors have separate classification and regression branches in the detection head [25], extracting task-specific features to predict object categories and bounding boxes. However, this decoupled design limits inter-task information flow, often resulting in suboptimal confidence scores and localization accuracy. To address this limitation, we propose the Rotation-sensitive Cross-branch Fusion Head (RCFHead), a novel detection head that features a bidirectional cross-branch interaction mechanism.

As illustrated in Figure 5, there are two tightly coupled sub-modules—MRPN, which generates coarse proposals and abject scores, and MRoI, which refines predictions using fused features from both tasks. Unlike conventional decoupled designs, our bidirectional fusion strategy enables mutual guidance between classification and regression streams. The classifier leverages spatial and boundary cues from the regressor, improving geometric awareness, while the regressor benefits from class-aware semantic priorities, enhancing localization precision. Specifically, a shared feature tensor Fshared is generated via a 3 × 3 convolution over the neck features and then passed to MRPN’s classification and regression branches to produce Fcls and Freg, with 3 and 12 channels, respectively. Within the MRPN, the Branch Coupling Module (BCM) fuses classification and regression features via element-wise addition at each spatial location:

Figure 5.

The overall architecture of RCFHead, which consists of the Mixed Region Proposal Network (MRPN) and the Mixed Region of Interest (MRoI) module. Different colored arrows indicate different branches and their corresponding feature interactions.

This residual fusion acts as a shortcut for gradient flow, facilitating direct interaction between semantic and geometric features within a shared spatial context. It enhances mutual awareness during training: classification features respond to localization errors, while regression features assimilate semantic priors—without introducing additional computational overhead. The fusion mechanism is bidirectional; following independent processing, features from the regression branch are integrated into the classification stream, and vice versa, via symmetric element-wise addition. This dual path coupling establishes an implicit feedback loop that promotes consistent feature refinement across tasks. is then passed to the MRoI head. The classification branch outputs P, and the regression branch estimates bounding box offsets and angles and :

where and denote the learnable weight matrices of the classification and regression branches, respectively.

Unlike conventional two fully connected (two-FC) detection heads, such as Faster R-CNN [24], which separate classification and regression, MRoI employs shared convolutional blocks after RRoI Align. This shared spatial representation keeps the two tasks interdependent, allowing classification features to guide localization. The classification subhead consists of one Conv and two FC layers, while the regression subhead features two Conv and one FC layer. This design retains spatial detail for localization and semantic abstraction for classification, thus reducing overfitting and enhancing generalization.

To further improve task interaction, MRoI introduces a cross-branch fusion mechanism, integrating geometric features from the regression branch into the classification stream. This enhances the alignment between classification confidence and localization accuracy without adding parameters and can be fully optimized via backpropagation. Together with weight sharing, this reduces memory overhead and mitigates overfitting risks from large FC layers.

In summary, the core innovation of RCFHead is its feature-aware, pixel-level cross-task fusion strategy, which substantially improves detection robustness under multi-scale and rotation-sensitive conditions.

4. Experiments

We evaluated RSDB-Net on two challenging public datasets: DOTA-v1.0 [26] and HRSC2016 [27]. Extensive comparisons were conducted with state-of-the-art methods, with both quantitative metrics and qualitative visualizations confirming the effectiveness and robustness of our approach in terms of detection accuracy.

4.1. Datasets and Metrics

Both DOTA-v1.0 and HRSC2016 feature oriented bounding box annotations. DOTA-v1.0 includes 15 object categories: plane (PL), baseball diamond (BD), bridge (BR), ground track field (GTF), small vehicle (SV), large vehicle (LV), ship (SH), tennis court (TC), basketball court (BC), storage tank (ST), soccer ball field (SBF), roundabout (RA), harbor (HA), swimming pool (SP), and helicopter (HC). The dataset was divided into 1411 images for training, 458 for validation, and 937 for testing, following the official protocol. Since the test annotations are not publicly available, the results were submitted to the official evaluation server for assessment. Random flipping was applied in three directions (horizontal, vertical, and diagonal) with probabilities of [0.25, 0.25, 0.25], simultaneously transforming rotated bounding boxes.

The main purpose of HRSC2016 is ship detection, and it follows the VOC-2007 [28] evaluation protocol and comprises 1061 images split into train (436), val (181), and test (444) images. We trained on train and val (617 images), and report the results on the test set (444 images).

We report average precision (AP) at a rotated Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 (AP50) as the primary metric. For DOTA-v1.0, the mean average precision (mAP) is computed by averaging AP scores across all categories. We used the following parameters: lr 0.005, momentum 0.9, and weight decay 1e−4. All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU and PyTorch 1.12 with CUDA 11.3, running under Python 3.8.

4.2. Ablation Experiments

To assess the contribution of each major component in RSDB-Net, we conducted ablation studies focusing on three key modules: STCBackbone, eFPN, and RCFHead. The model was trained for 12 epochs on a single-scale detection dataset composed of 1024 × 1024 image patches generated by tiling the original images.

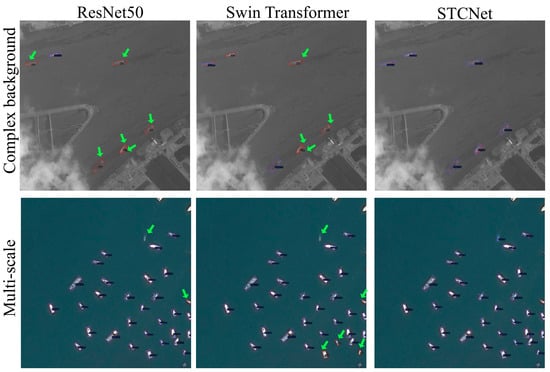

4.2.1. Effective Backbone Experiments

The detection results are presented in Figure 6. For both complex background and multi-scale ships, RSDB-Net achieves more accurate vessel detection and effectively suppresses false positives compared to baseline models. For a rigorous quantitative evaluation, all models were trained on DOTA-v1.0 for 12 epochs using a consistent configuration: FPN neck followed by an RoITransformer head [3].

Figure 6.

Detection results when using different backbones. Red boxes denote the ground truth, blue boxes indicate detected ships, and green arrows highlight missed ships.

As summarized in Table 3, substituting the conventional ResNet-50 [24] with our STCBackbone improves the AP for the ship category from 83.59% to 87.83%, and surpasses that of pure ST (82.65%) by 5.18%. This validates the novelty of STCBackbone in effectively coupling local CNN and global Transformer features. When combined with RCFHead, STCBackbone further elevates the AP to 88.12%. STCBackbone achieves similar improvements on HRSC2016, consistently outperforming existing backbones across RoITransformer and Faster_RCNN, which are marked with up arrows, confirming its robustness and strong generalization capability.

Table 3.

AP of DOTA-v1.0 with different backbones.

4.2.2. Neck Experiments

To evaluate the impact of eFPN, we conducted a comparative study between the FPN and the eFPN. Additionally, to further analyze the contribution of the high-resolution feature level (P0), we introduced an intermediate variant denoted as FPN + P0. As shown in Table 4, adding the P0 layer enhances the AP for ships from 87.83% to 88.04%, while replacing the standard FPN with the proposed eFPN further improves it to 88.40%. In the table, a single arrow indicates a slight AP improvement after adding P0, whereas a double arrow denotes the further AP enhancement achieved by the proposed eFPN. Compared with the classical FPN, these results demonstrate that incorporating the high-resolution level (P0) positively affects ultra-small ship detection. Replacing the standard FPN with eFPN in RSDB-Net improves the AP for ship detection from 87.83% to 88.40%. This demonstrates the advantages of learnable transposed convolution in adaptive multi-scale feature fusion compared with the classical FPN. Importantly, even when using conventional backbones such as ResNet50 or ST, the achieved AP remains lower than that of RSDB-Net with eFPN, underscoring the effectiveness of our neck design. These results confirm that the proposed eFPN module exhibits significantly enhanced detection accuracy, especially when integrated with the STCBackbone. Overall, these results highlight the significant advantage of including the P0 level and validate the rationality of eFPN’s hierarchical design for robust detection of small-scale objects. Moreover, the modular design of eFPN ensures robust performance and portability, allowing it to be seamlessly integrated into various detection networks without requiring architectural changes.

Table 4.

mAP of DOTA-v1.0 in different necks.

4.2.3. Effective Head Experiments

We evaluated RCFHead by testing ResNet-50, ST, and STCBackbone with a unified FPN configuration. As shown in Table 5, replacing RoITransformer with RCFHead improves the AP to 88.12% on DOTA-v1.0, verifying that the proposed cross-branch fusion mechanism enhances both classification–regression consistency and rotation sensitivity.

Table 5.

mAP of DOTA-v1.0 in different heads.

To further validate the independent contribution of the proposed interaction mechanism through more fine-grained experiments, as shown in Table 6, we conducted a comparison between the RPN (without BCM) and the proposed MRPN on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset to quantify the performance improvement introduced by the bidirectional coupling mechanism. The results verify the effectiveness of the proposed pixel-level cross-task fusion strategy.

Table 6.

Systematic ablations on RCFHead.

In addition, based on the RoITransformer framework, we integrated both MRPN and MRoI modules and compared the unfused MRoI head with the MRoI head employing the proposed cross-branch fusion strategy. The results demonstrate that this fusion mechanism enables more precise alignment between the classification and localization branches, thereby enhancing the overall detection accuracy.

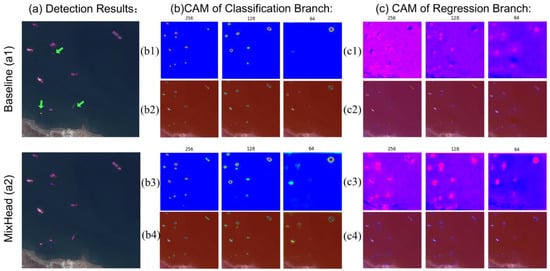

Class activation maps (CAMs) are visualized in Figure 7. RCFHead generates stronger, more focused activations across resolutions (256, 128, 64), yielding sharper boundaries and more accurate boxes. The green arrows in Figure 7(a1) highlight small vessels missed by the baseline due to weak activations in Figure 7(b1), while these are effectively detected by RCFHead, as shown in Figure 7(b3). Similarly, Figure 7(c3) exhibits more compact regression activations than Figure 7(c1), indicating better localization. These qualitative results are consistent with the improvements in performance.

Figure 7.

Comparison of detection results and class activation maps (CAMs) between the baseline and RCFHead: (a) Detection outputs, with the red boxes indicate the detected ships and green arrows indicating missed ships. (b) Classification CAMs at feature resolutions of 256, 128, and 64; (b1/b3) show CAMs of the Classification Branch for the baseline and RCFHead at 256, 128, and 64 resolutions. (b2) and (b4) show overlays with original images. (c) Regression CAMs at corresponding resolutions, and (c1/c3) show CAMs of the Regression Branch for the baseline and RCFHead at the same resolutions, with (c2) and (c4) presenting overlays.

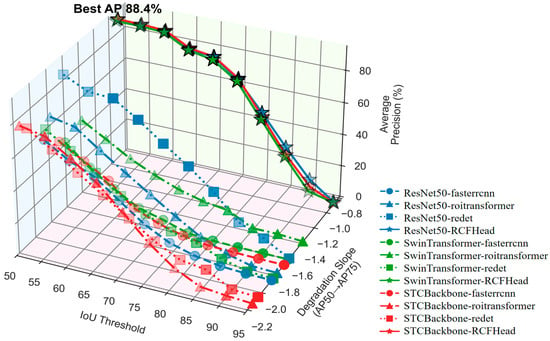

We further evaluated four detection heads: Faster R-CNN, RoITransformer, ReDet [29], and the proposed RCFHead. These heads were combined with three backbone networks on HRSC2016, and the detection performance was measured at IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95. The slope between AP50 and AP75 was also calculated to quantify localization degradation, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Quantitative comparison of detection heads across IoU thresholds in HRSC2016.

RCFHead consistently achieves the highest performance across all IoU thresholds (AP50–AP95). It achieves an average precision of 88.4% and a degradation slope of −0.876, indicating minimal accuracy loss as IoU increases. In contrast, ReDet and RoITransformer show much steeper declines (slope < −1.8). This indicates that their stability decreases significantly under large-angle rotations.

As shown in Figure 8, RCFHead consistently outperforms all other heads across the entire IoU range. Notably, it maintains stable performance even at IoU ≥ 0.85, at which the performance of conventional methods drops sharply. The degradation slope remains above –0.90 in all cases, with the STCBackbone + RCFHead combination achieving the flattest decline (–0.876). This indicates that its predictions are more geometrically aligned with the ground truth even under strict thresholds.

Figure 8.

Analysis of AP across IoU thresholds and degradation slopes for various detector configurations on HRSC2016. The best AP (88.4%) is achieved by STCBackbone-RCFHead.

These improvements are mainly attributed to RCFHead’s rotation-consistent convolution module and dynamic fusion strategy, which jointly enhance feature adaptability to multi-oriented targets. This highlights RCFHead’s superior localization precision, robustness under stringent conditions, and adaptability across different architectures. It offers a practical solution to the long-standing challenge of balancing classification and regression in rotated-object detection.

4.2.4. Experiments on DOTA-v1.0 and HRSC2016

We evaluated RSDB-Net on DOTA-v1.0 and HRSC2016 to validate the proposed architecture. As shown in Table 8, RSDB-Net significantly outperforms the baseline on both datasets. On HRSC2016, RSDB-Net achieved an AP50 of 88.4%—a 42.7% improvement over the baseline’s 45.7%, nearly doubling the detection performance. This gain is attributed to the combined contributions of STCBackbone, eFPN, and RCFHead, which enhance feature representation and localization precision. Similarly, on DOTA-v1.0, incremental improvements from ST to STCBackbone and further to RCFHead highlight the effectiveness of each component in rotation-aware ship detection.

Table 8.

Ablation experiment using DOTA-v1.0 and HRSC2016.

4.3. RSDB-Net Visual Effects

We further validated RSDB-Net’s practical reliability through qualitative comparisons. Figure 9 presents representative detection results across three challenging scenarios. RSDB-Net successfully detects ships in complex backgrounds, diverse orientations, and scale variations, demonstrating strong robustness and generalization in real-world conditions.

Figure 9.

Representative results of RSDB-Net under three challenging scenarios in real-world remote sensing imagery: (a) complex backgrounds; (b) multiple orientations; (c) multi-scale features. The green boxes indicate the ships detected by the network.

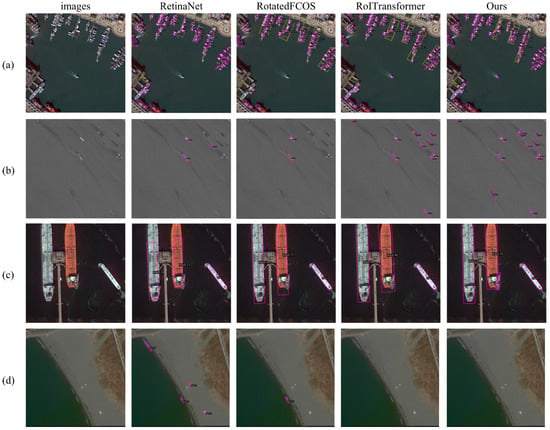

Figure 10 presents a qualitative comparison of four detection networks: RetinaNet, Rotated FCOS, RoITransformer, and the proposed RSDB-Net. The first column showcases the original images, with the following columns displaying the detection outcomes. In comparison to the other methods, RSDB-Net demonstrates superior performance, particularly where (a) complex backgrounds, (b) significant scale variations, (c) random object orientations, and (d) poorly visible ships are present. RSDB-Net generates fewer false positives and exhibits an enhanced discriminative accuracy. These findings underscore the robustness and practical applicability of RSDB-Net for real-world remote sensing applications.

Figure 10.

Comparison of results across different networks under various scenarios. (a) complex backgrounds, (b) significant scale variations, (c) random object orientations, and (d) poorly visible ships are present. The red boxes indicate the ships detected by the network, while the yellow boxes highlight docks that are prone to being falsely detected as ships.

4.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Networks

We evaluated RSDB-Net against leading detectors on HRSC2016 and DOTA-v1.0. All models are trained on official splits and tested under identical conditions. The model was trained for 36 epochs on a multi-scale segmentation dataset with image resolutions of 512 × 512, 1024 × 1024, and 2048 × 2048. As shown in Table 9, RSDB-Net outperforms the other networks in 6 of 15 categories, achieving top AP scores. In the ship (SH) category, it achieves an AP of 89.13%, significantly surpassing the baseline (77.81%) and RoITransformer (69.56%), which particularly highlights the superior performance of our method in this category. The results are from the original papers or were reproduced using consistent setups. These results highlight RSDB-Net’s robustness and generalization, driven by its modular components that improve multi-scale representation and geometric adaptability.

Table 9.

Comparison of RSDB-Net with state-of-the-art methods on DOTA_v1.0.

To address concerns regarding real-time efficiency, we performed quantitative comparisons of inference speed (FPS) and computational complexity (GFLOPs and Parameters), as shown in Table 10. Specifically, RSDB-Net achieves 72 FPS on an RTX 3090 GPU with an input size of 512 × 512, corresponding to 101.6 GFLOPs and 89.49 M parameters, while maintaining a higher accuracy than other state-of-the-art detectors. These results demonstrate that RSDB-Net not only exhibits a competitive detection performance but also achieves a favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency, supporting real-time inference for practical deployment.

Table 10.

Comparison of computational complexity and real-time performance on DOTA_v1.0.

Table 11 summarizes the detection results on HRSC2016, comparing RSDB-Net with various existing methods. AP values, except for the baseline, are sourced from the original publications.

Table 11.

Comparison of RSDB-Net with state-of-the-art methods on HRSC2016.

RSDB-Net achieves an AP50 of 90.1% (as shown in Table 11) with high-resolution inputs, surpassing most previous methods. This demonstrates its exceptional adaptability to high-resolution imagery, where increased detail often introduces scale imbalance. Unlike many detectors that degrade at higher resolutions due to inadequate multi-scale fusion, RSDB-Net ensures stable and accurate detection. This robustness stems from its unified design: the STCBackbone captures fine-grained textures, the eFPN maintains cross-scale consistency, and RCFHead enhances geometric localization. Notably, RSDB-Net outperforms other popular networks in remote sensing. These results highlight that RSDB-Net not only excels in accuracy but also scales effectively with resolution, making it ideal for real-world scenarios with dense, complex objects with varying orientations.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents RSDB-Net, a novel dual-branch Transformer–CNN detector designed to address the challenges of complex backgrounds, multi-scale objects, and random orientations in remote sensing ship detection. The network features a dual-path STCBackbone, with an ST branch for global semantic context and a CNN branch for local spatial details. These features are effectively aligned and fused through the FCCM, enhancing adaptability to multi-scale objects and complex scenes. The Rotation-sensitive Cross-branch Fusion Head (RCFHead), which enables bidirectional task interaction between classification and localization, significantly improves the detection accuracy, especially for arbitrarily oriented objects. This design enhances robustness in complex backgrounds by overcoming the traditional decoupling of classification and regression tasks. Moreover, the enhanced Feature Pyramid Network (eFPN) with learnable transposed convolutions restores high-level semantics lost during downsampling, further improving robustness in dense and complex backgrounds.

Experiments on the DOTA-v1.0 and HRSC2016 datasets demonstrate RSDB-Net’s superiority, with it achieving AP-ship scores of 89.13% and 90.1%, respectively, and outperforming state-of-the-art methods. These quantitative gains demonstrate RSDB-Net’s strong generalization and reliability for real-world ship monitoring, maritime traffic control, and harbor surveillance applications. Its modular design allows for easy integration into other detection networks.

In the future, we will focus on real-time deployment through lightweight model compression and parallel inference optimization and will also explore domain adaptation strategies and larger-scale datasets to enhance generalization under diverse imaging and oceanic conditions (Algorithm 2).

| Algorithm 2: RSDB-Net |

| Input: Preprocessed training data I and corresponding labels t. Output: Trained object detection network and detection results. Step 1: Feature Extraction 1. For each training iteration t = 1, 2, …, T: 2. For each Unit i = 1, 2, …, 4: 3. Extract features MC using the CNN branch in Unit i. 4. Extract features MS using the ST branch in Unit i-1. 5. If the features are from the CNN branch: 6. Fuse MC with MS using the FCCM to obtain fused features MSMS. 7. Pass the fused features MSMS. to the next unit. Step 2: Feature fusion 8. Propagate features through the feature pyramid module. 9. Apply transposed convolution to perform upsampling and enhance the feature maps. 10. Construct the feature pyramid P = {P1, P2, P3, P4, P5}. 11. For each feature map Pi∈P, predict the detection results r. Step 3: Post-Processing Detection Results 12. Compute the overlap between the predicted boxes pb and all ground truth. 13. If the max_overlap > 0.5, then: 14. Assign the corresponding ground truth as the object and label the predicted box as a positive example. 15. Return the final detection results. |

Author Contributions

D.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation. Y.X.: Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Validation. S.Y.: Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition. P.F.: Data curation, Funding acquisition. J.L.: Writing—review and editing, Investigation, Methodology. N.W.: Writing—review, Funding acquisition, Supervision. R.D.: Writing—review and editing, Project administration, Supervision, Data curation, Formal analysis. L.L.: Writing—review, Funding acquisition, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Grant No. XDB0460000; in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62334008, 62274154, U21A20504, and 62134004; and in part by the Youth Innovation Promotion Association Program, Chinese Academy of Sciences under Grant 2021109.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.S.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI Transformer for Oriented Object Detection in Aerial Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2849–2858. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Yang, X.; Xiao, S.; Yu, Y.; Jia, C. A Line Segment-Based Inshore Ship Detection Method. In Future Control and Automation, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Future Control and Automation (ICFCA 2012), Changsha, China, 1–2 July 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, B.; Ji, S.; Gao, F.; Xu, Q. Ship detection from optical satellite images based on sea surface analysis. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2013, 11, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Guo, H.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Xu, Q.; Lin, Y.; Ding, L. An Anchor-Free and Angle-Free Detector for Oriented Object Detection Using Bounding Box Projection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5618517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, M.; Dong, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhao, S.; Wang, H. Vector Decomposition-Based Arbitrary-Oriented Object Detection for Optical Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; You, Z.H.; Chen, S.B.; Huang, L.L.; Tang, J.; Luo, B. Feature Enhancement and Alignment for Oriented Object Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 17, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Xie, Y.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Sun, F. ReBiDet: An Enhanced Ship Detection Model Utilizing ReDet and Bi-Directional Feature Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Cai, C.; Tang, W.; Tian, Y.; Huang, K. RA2DC-Net: A Residual Augment-Convolutions and Adaptive Deformable Convolution for Points-Based Anchor-Free Orientation Detection Network in Remote Sensing Images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X. Ship-DETR: A Transformer-Based Model for Efficient Ship Detection in Complex Maritime Environments. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 3559107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020, Proceedings of the 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Lei, G.; Zhuang, Y.; Mao, X. Popeye: A Unified Visual-Language Model for Multi-Source Ship Detection from Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 20050–20063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D. Swin-UNet: Unet-Like Pure Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2022, Proceedings of the 25th International Conference, Singapore, 18–22 September 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Xu, H.; Liu, H. DPT: Deformable Patch-Based Transformer for Visual Recognition. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual Event, China, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 2899–2907. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wen, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, Z. Single-Image Super Resolution for RGB Remote Sensing Imagery Via Multi-Scale CNN-Transformer Feature Fusion. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 18, 1302–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Huang, X.; Guan, Q. TabCtNet: Target-Aware Bilateral CNN-Transformer Network for Single Object Tracking in Satellite Videos. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 128, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Fan, G.; Wu, Q. FSCMF: A Dual-Branch Frequency–Spatial Joint Perception Cross-Modality Network for Visible and Infrared Image Fusion. Neurocomputing 2025, 587, 130376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, L.; Wu, B.; Lin, B.; Li, L.; Liu, W. Crossformer++: A Versatile Vision Transformer Hinging on Cross-Scale Attention. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 3123–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamali, A.; Roy, S.K.; Ghamisi, P. WetMapFormer: A Unified Deep CNN and Vision Transformer for Complex Wetland Mapping. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 120, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Tan, K.; Wang, X.; Tang, S.; Sun, J.; Niu, C.; Pan, C. PatchOut: A Novel Patch-Free Approach Based on a Transformer-CNN Hybrid Framework for Fine-Grained Land-Cover Classification on Large-Scale Airborne Hyperspectral Images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 138, 104457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.-S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A Large-Scale Dataset for Object Detection in Aerial Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3974–3983. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Weng, L.; Yang, Y. A High Resolution Optical Satellite Image Dataset for Ship Recognition and Some New Baselines. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods (ICPRAM 2017), Porto, Portugal, 24–26 February 2017; pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.K.I.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Shao, Z. ReDet: A Rotation-Equivariant Detector for Aerial Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 2786–2795. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Ren, Y.; Sheng, K.; Dong, W.; Yuan, H.; Guo, X.; Ma, Z.; Xu, C. Dynamic Refinement Network for Oriented and Densely Packed Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11207–11216. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Yuan, M.; Jiang, F.; Celik, T.; Li, H.-C. Removal Then Selection: A Coarse-to-Fine Fusion Perspective for RGB-Infrared Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10731. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Shen, S.; Fan, L.; Yao, S.; Song, M.; Hui, P. Free3Net: Gliding Free, Orientation Free, and Anchor Free Network for Oriented Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 7089–7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yao, R.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J.; Xiong, S.; Chen, Y. Oriented Object Detector with Gaussian Distribution Cost Label Assignment and Task-Decoupled Head. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Q.; Miao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Dong, Y. CFC-Net: A Critical Feature Capturing Network for Arbitrary-Oriented Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, Z.; He, T. R3Det: Refined Single-Stage Detector with Feature Refinement for Rotating Object. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 3163–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Cheng, G.; Lang, C.; Xie, X.; Han, J. Centric Probability-Based Sample Selection for Oriented Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 10289–10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, C.; Hu, B.; Li, J.; Plaza, A. Efficient Object Detection in Large-Scale Remote Sensing Images via Situation-Aware Model. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 22486–22498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Chen, C.; Yan, S.; Li, W.; Wang, P. FADL-Net: Frequency-Assisted Dynamic Learning Network for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 9939–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ding, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, H.; Du, W.L.; Yao, R.; El Saddik, A. OrientedFormer: An End-to-End Transformer-Based Oriented Object Detector in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. EOOD: End-to-end Oriented Object Detection. Neurocomputing 2025, 621, 129251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Yao, Y.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Han, J. Dual-Aligned Oriented Detector. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wei, M.; Gao, G.; Li, C.; Liu, Z. SARFA-Net: Shape-Aware Label Assignment and Refined Feature Alignment for Arbitrary-Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 8865–8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Liao, W.; Yang, X.; Tang, J.; He, T. SCRDet++: Detecting Small, Cluttered and Rotated Objects via Instance-Level Feature Denoising and Rotation Loss Smoothing. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 2384–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuan, S.; Zheng, W.; Zhijing, X. Ship-Yolo: A Deep Learning Approach for Ship Detection in Remote Sensing Images. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Wang, J.; Cheng, G.; Xie, X.; Han, J. Learning orientation-aware distances for oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wu, X. Small Object Detection in Synthetic Aperture Radar with Modular Feature Encoding and Vectorized Box Regression. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Qi, N. LTGS: An optical remote sensing tiny ship detection model. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2025, 28, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Liu, H.; Tang, H.; Wu, Z.; Song, P. AO2-DETR: Arbitrary-Oriented Object Detection Transformer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 2342–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fu, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xia, G.S.; Bai, X. Gliding Vertex on the Horizontal Bounding Box for Multi-Oriented Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Leng, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Quan, P.; Zhao, W. SKNet: Detecting Rotated Ships as Keypoints in Optical Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 8826–8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Shen, W. Research on Oriented Object Detection in Aerial Images Based on Architecture Search with Decoupled Detection Heads. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Miao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Ming, Q.; Dong, Y. Optimized Point Set Representation for Oriented Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Jing, D.; Lu, B.; Zheng, D.; Ren, S.; Chen, Z. Shape-Aware Dynamic Alignment Network for Oriented Object Detection in Aerial Images. Symmetry 2025, 17, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wei, Z.; Plaza, J.; Plaza, A. A Mask Guided Oriented Object Detector Based on Rotated Size-Adaptive Tricube Kernel. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5615815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Liu, N.; Celik, T.; Li, H.-C. An Arbitrary-Oriented Object Detector Based on Variant Gaussian Label in Remote Sensing Image. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 8013605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, L.; Bi, H. Gaussian Focal Loss: Learning Distribution Polarized Angle Prediction for Rotated Object Detection in Aerial Image. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4707013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, L. ABFL: Angular Boundary Discontinuity Free Loss for Arbitrary-Oriented Object Detection in Aerial Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Zhao, B.; Lei, D.; Mao, Y. A Robust Multi-Scale Ship Detection Approach Leveraging Edge Focus Enhancement and Dilated Residual Aggregation. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, H. Contour Modeling Arbitrary-Oriented Ship Detection from Very High-Resolution Optical Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).