Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A PROSAIL-driven, GA-optimised MLP (NN–GA) reliably retrieves crop LAI from Sentinel-2B at 10 m, achieving RMSE/R2 = 0.44/0.73 (Minqin) and 0.40/0.56 (Zhangye), outperforming the SNAP/SL2P benchmark.

- A staged uncertainty quantification (UQ) workflow separates physical-driver and machine-learning contributions and synthesises them to report retrieval relative uncertainties (Minqin 21.37%, Zhangye 17.31%).

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The framework improves 10 m LAI retrieval accuracy and delivers a reproducible, end-to-end uncertainty decomposition to support confidence-aware agronomic applications.

- The results prioritise reductions in machine-learning stage stochasticity and recommend including uncertainty as a routine product layer to increase LAI product reliability.

Abstract

Leaf Area Index (LAI) is a key biophysical descriptor of crop canopies and is essential for growth monitoring and yield estimation. We present a physics-driven machine-learning framework for operational LAI retrieval and end-to-end uncertainty quantification that couples the PROSAIL radiative transfer model with a genetic-algorithm-optimised multilayer perceptron (NN–GA). PROSAIL is sampled across plausible parameter priors and spectra are convolved with Sentinel-2B spectral response functions to build a 30,000-sample training library; a GA is used to globally optimise network weights and biases. Total retrieval uncertainty is decomposed into a simulation component (PROSAIL parameter variability) and a training component (variability across repeated NN–GA trainings) and combined via the law of propagation of uncertainty. The model was developed in Minqin (modelling/testing area; entirely maize) and transferred to Zhangye (transfer/validation area; predominantly maize, with one sunflower plot). Sentinel-2B validation results were RMSE/R2 = 0.44/0.73 (Minqin) and 0.40/0.56 (Zhangye), indicating reasonable cross-site generalisation. The uncertainty split indicates physical-driven contributions of 11.42% and 11.48% and machine-learning contributions of 18.06% and 12.96%, respectively. The framework improves 10 m LAI retrieval accuracy and supplies a reproducible, per-pixel uncertainty budget to guide product use and refinement.

1. Introduction

Leaf Area Index (LAI), defined as one half of the total one-sided leaf area per unit ground area, is a central biophysical descriptor of crop canopies that controls light interception and photosynthetic productivity [1]. In agricultural applications, LAI underpins crop-growth modelling, yield forecasting, irrigation and fertilisation scheduling, and phenological and pest/disease monitoring; hence accurate, spatially explicit LAI estimates are of direct practical value for agronomic decision support and precision farming. Because in situ LAI measurements (e.g., destructive sampling or canopy analysers) provide only sparse point observations and are labour-intensive to acquire at scale, satellite and airborne remote sensing have become the primary means to generate continuous, wall-to-wall LAI products over operational extents [2,3].

Remote retrieval approaches for LAI broadly fall into empirical statistical methods and physics-based radiative transfer model (RTM) methods [4]. Empirical regressions or vegetation-index approaches are simple to implement and often perform well within the calibration domain, but their transferability across sensors, scene types, and phenological stages is limited [5]. Physics-based RTMs—most notably, the coupled PROSPECT (leaf optics) and SAIL (canopy scattering) system, PROSAIL—simulate canopy reflectance as a function of biophysical variables and observation geometry, providing mechanistic constraints that improve interpretability and enable the generation of large synthetic training libraries for controlled testing [6]. Since forward RTMs do not directly yield parameter estimates, practical retrievals typically invert the models using lookup tables, optimisation schemes, or data-driven regressors (e.g., neural networks, random forests, support vector regression), combining physical realism with the flexibility of machine learning to fit complex, nonlinear mappings [7,8].

Despite their strengths, coupling radiative transfer models (RTMs) with data-driven learners still faces fundamental challenges. RTMs typically rely on simplified parameterizations that cannot fully capture canopy and physiological heterogeneity; as a result, inversion problems can exhibit parameter equifinality and ill-posedness, while data-driven approaches remain highly sensitive to the representativeness and distribution of the training data, limiting out-of-domain generalisation. Together, these factors reduce the reliability and transportability of retrievals across differing crop conditions and sensor observations [9,10,11]. To mitigate these issues, global optimisation and ensemble-based strategies have been explored. In particular, genetic algorithms (GAs) provide a population-based global search that helps explore wide, multimodal parameter landscapes [7,12,13]. This capability can (i) reveal equifinality by locating distinct parameter sets that produce similar spectral responses, (ii) support multi-objective or regularised fitness formulations that penalise physically implausible parameter combinations (thereby suppressing practically irrelevant equifinal solutions), and (iii) facilitate ensemble generation (via multiple independent GA runs or archives of near-optimal solutions) whose spread offers an empirical characterisation of solution non-uniqueness and model uncertainty. When combined with a feedforward neural network (NN–GA), GAs’ global search complements the NN’s expressive power: the hybrid improves training stability and reproducibility, enables direct optimisation of bespoke fitness functions (for example, validation-weighted loss), and supplies practical diagnostics and ensemble outputs that inform uncertainty quantification and robustness analyses.

A further, often overlooked challenge is rigorous end-to-end uncertainty quantification (UQ). Existing studies on remote-sensing uncertainty predominantly focus on upstream data quality (for example, radiance, surface reflectance, or atmospheric-correction residuals), while a traceable, quantitative decomposition of errors across the entire retrieval chain—from observations and RTM forward simulation to inversion and downstream LAI estimates—remains limited [4]. Operational products such as global MODIS LAI include quality flags and per-pixel standard deviation layers (e.g., STD_LAI), and many validation studies report aggregate accuracy metrics; however, these provisions do not substitute for a systematic partitioning and quantitative propagation of uncertainties arising from prior parameter uncertainty, model structural error, and inversion-stage algorithmic variability [14]. In practice, retrieval products are typically summarised by RMSE or R2 against reference data, but are seldom accompanied by confidence intervals or a source-resolved error budget—information that is essential for uncertainty-aware model assimilation and operational decision support [15].

Some recent efforts (for example, product reprocessing and noise reduction for MODIS LAI) have improved temporal consistency and reduced spurious variability, yet they mainly address time-series quality control rather than providing a principled accounting of how specific error sources propagate through each stage of the retrieval pipeline [16]. Concurrently, the rapid adoption of machine-learning methods introduces additional uncertainty modes—such as calibration uncertainty, probabilistic predictive outputs, and model confidence—which require dedicated UQ treatments. Although methodological research on neural-network uncertainty estimation is advancing, its practical application to operational biophysical-parameter retrievals remains limited [17].

Motivated by these gaps, this study develops a physics-driven machine-learning framework that couples the PROSAIL radiative transfer model with a genetic-algorithm-optimised multilayer perceptron (NN–GA) inversion and an explicit, staged UQ protocol. Our objectives are to deliver a broadly applicable LAI retrieval model and a reproducible UQ workflow to support robust product generation and to provide methodological guidance for uncertainty estimation of other land-surface variables. Concretely, we (1) construct a PROSAIL-based forward simulation library matched to Sentinel-2 spectral response functions (SRFs); (2) integrate a feedforward multilayer perceptron (MLP) with a GA for global optimisation of network parameters; (3) evaluate the approach across contrasting agricultural sites to test transferability; and (4) decompose the LAI retrieval uncertainty-propagation chain into constituent stages, estimate the uncertainty contribution of each stage, and synthesise these estimates to produce a comprehensive quantification and assessment of the overall LAI retrieval uncertainty.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Research Area and Data Collection

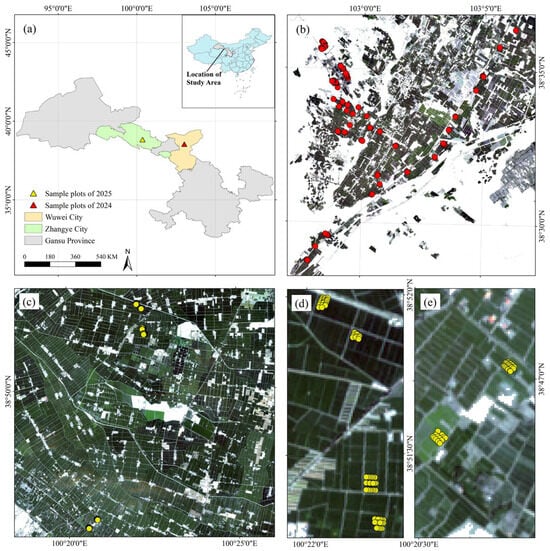

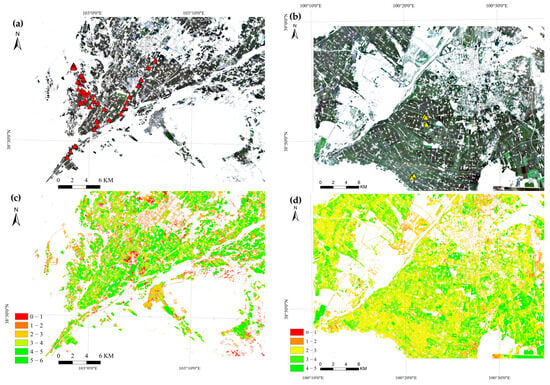

The study was carried out at two agricultural sites in northwest China. Site 1 (Minqin County, Wuwei City, Gansu Province; 102°56′–103°07′E, 38°28′–38°37′N) served as the model-development and testing area for PROSAIL simulations, NN–GA training, and preliminary parameter tuning. Site 2 (Ganzhou District, Zhangye City; 100°16′–100°27′E, 38°45′–38°53′N) was used as a transfer and demonstration/validation area to evaluate model generalisation and transfer performance. Field campaigns synchronous (or near-synchronous) with the Sentinel-2 acquisitions were conducted on 31 August–1 September 2024 (maize, maturity stage) and 3–9 July 2025 (maize and sunflower; maize at tasseling). The locations and the spatial distributions of field sampling points are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study area and sampling design. (a) Geographic locations of the two study sites in Gansu Province, China: Minqin County and Ganzhou District, Zhangye; (b) Spatial distribution of field sampling points acquired in 2024 (red markers). Base map: Sentinel-2B Level-2A true-colour composite (B4/B3/B2), ESA/Copernicus (acquisition: 29 August 2024); (c) Spatial distribution of field sampling points acquired in 2025 (yellow markers). Base map: Sentinel-2B Level-2A true-colour composite (B4/B3/B2), ESA/Copernicus (acquisition: 8 July 2025); (d) Detailed view of the four intensive sampling subplots in the northern sector of panel (c). Base map: same as panel (c); (e) Detailed view of the two intensive sampling subplots in the southern sector of panel (c). Base map: the same as panel (c). All base maps showing bottom-of-atmosphere (Level-2A) reflectance were resampled to a common 10 m grid for display, and are presented in WGS84 (EPSG:4326). Data source: Copernicus Sentinel-2 MSI (© Copernicus Sentinel data 2024/2025).

Both sites lie in the mid-latitude zone of northwest China and are characterised by a warm-temperate to temperate continental arid–semi-arid climate. Minqin, located near the desert margin, exhibits pronounced aridity and desertification, whereas Ganzhou (Zhangye) is influenced by the summer monsoon and contains irrigated oasis agriculture with more concentrated precipitation. The landscape is dominated by plains and oasis farmland at low to moderate elevations; summers are hot by day and cool at night, annual precipitation is low, and rainfall is strongly seasonal. Major crops include winter wheat, spring/summer maize, and potato; the maize growing season typically extends from late June to mid–late September.

To balance regional representativeness with accurate pixel-scale matching to satellite data, two complementary ground-sampling strategies were adopted. In Minqin (modelling/testing site), 101 sparsely distributed sample points were established (inter-point distance ≥ 300 m) to capture landscape-scale heterogeneity in topography, soil, and management practices, and to support regional generalisation tests. In Zhangye (transfer/validation site), we selected three representative 500 × 500 m blocks and deployed dense sampling grids within each block: every block contained two 48 × 48 m sampling plots in which points were laid out along three transects at 2 m intervals (≈81 points per plot) to provide robust, pixel-scale LAI estimates. All field sampling locations were sited at least 10 m from field or canopy edges to minimise the probability of boundary/mixed-pixel contamination.

Canopy LAI was measured in situ with a LAI-2200 Canopy Analyzer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) following an A–B–B–B–B sequence (one above-canopy reading “A” alternated with four below-canopy readings “B”) using the 270° view cap. For each sampling location, the four below-canopy B readings were taken to capture ridge–row variability: on the ridge, at 1/4 of the inter-row distance, at the inter-row centre, and at 3/4 of the inter-row distance. LAI values were derived using the standard LI-COR processing workflow: the single above-canopy (A) reading was paired with each below-canopy (B) reading and the LAI-2200 software (gap-fraction algorithm) produced four instantaneous PAI/LAI estimates; these four estimates were then averaged to yield the final LAI assigned to that sampling position. No additional clumping correction was applied because all field measurements were acquired within diffuse-sky conditions (uniform overcast or thick, spatially uniform cloud cover) in which directional illumination effects are minimal and the uncorrected gap-fraction retrieval is appropriate (see the LI-COR user manual). For plot- or pixel-level validation, individual point LAI measurements within a sampling plot were averaged to obtain a single representative LAI for comparison with the 10 m Sentinel-2 retrieval.

2.2. Satellite Imagery Acquisition and Processing

Sentinel-2 is an optical Earth-observation mission within the Copernicus programme, comprising two twin satellites (Sentinel-2A, launched June 2015, and Sentinel-2B, launched March 2017). Its MultiSpectral Instrument (MSI) acquires 13 spectral bands spanning the visible, red-edge, near-infrared, and shortwave-infrared portions of the spectrum, with nominal spatial resolutions of 10 m, 20 m, and 60 m. For this study, we used Level-2A bottom-of-atmosphere (BOA) surface reflectance products obtained from the ESA data platform (Dataspace); these products are radiometrically calibrated and atmospherically corrected and are therefore appropriate for quantitative vegetation retrieval.

Two Sentinel-2B scenes (29 August 2024 and 8 July 2025) were used. All reflectance bands were resampled to a common 10 m grid to ensure tight spatial co-registration for model input: continuous reflectance layers were resampled with bilinear or cubic-convolution interpolation to preserve spectral smoothness, while the Scene Classification Layer (SCL) was resampled with nearest-neighbour interpolation to avoid fractional/mixed class labels produced by continuous interpolants. Whole-scene cloud cover was 13.71% for the Minqin image and 13.57% for the Zhangye image; clouds were largely confined to desert areas, so we cropped each scene to the sampling-area centre before analysis. An SCL-derived quality mask was then applied to exclude clouds, cloud shadows, and other invalid pixels. To focus the retrieval on substantive vegetation, we applied a fixed NDVI mask: pixels with NDVI ≤ 0.20 were treated as non-vegetated and excluded from further analysis. The fixed-threshold approach defines a single lower NDVI bound below which vegetation is considered absent regardless of location or local conditions; NDVI values > 0.20 are interpreted as indicating increasing canopy cover (though the NDVI–cover relationship is not strictly linear) [18]. This conservative, widely used threshold helps remove bare soil and very sparse vegetation prior to LAI retrieval.

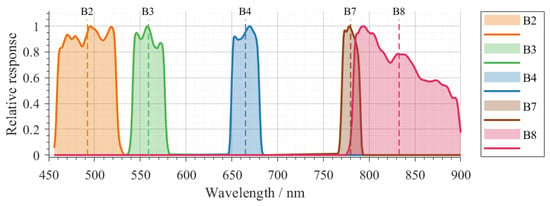

The final analysis dataset comprises spatially co-registered, quality-controlled 10 m multispectral reflectance layers used for LAI retrieval and uncertainty analysis: B2 (blue), B3 (green), B4 (red), B7 (red-edge, resampled from 20 m to 10 m), and B8 (near-infrared). Band centre wavelengths and native spatial resolutions are summarised in Table 1. The choice of this five-band set balances spectral sensitivity to canopy structure and the practical considerations of native spatial resolution and noise: red-edge and NIR channels (B7, B8, B8A) are known to carry information relevant to LAI and canopy structure (ESA Sentinel-2 MSI Technical Guide), but B8A (20 m) overlaps substantially with B8 while requiring upsampling that can introduce scale-mismatch noise and amplify saturation effects at high LAI; therefore, B8 (10 m) was preferred to maintain native spatial consistency.

Table 1.

Sentinel-2B bands used in this study.

2.3. PROSAIL Radiative Transfer Modelling

The PROSAIL model couples the PROSPECT leaf-optical model with the SAIL canopy scattering model to provide a physics-based link between leaf optical properties and canopy-scale directional reflectance. In PROSPECT, a leaf is represented as a multilayer homogeneous plate; leaf absorption and scattering across the 400–2500 nm spectral domain are computed from biophysical and biochemical inputs including the leaf structure parameter (N), chlorophyll content (Cab), dry-matter content (Cm), and equivalent water thickness (Cw). The SAIL component treats the canopy as a homogeneous continuous medium and solves the radiative-transfer problem at canopy scale, accounting for canopy structural parameters (e.g., LAI and leaf angle distribution, parameterized here by average leaf angle, ALA) together with solar–sensor geometry to simulate bidirectional reflectance.

2.3.1. Sensitivity Analysis

To identify the PROSAIL inputs that most strongly influence simulated reflectance in the 450–950 nm interval, we adopted a two-step hierarchical sensitivity-analysis protocol. First, the Morris screening method was applied as a computationally efficient global filter to rank candidate parameters by their elementary effects [19]. Second, the subset of parameters selected by Morris was subjected to Sobol variance-based decomposition to obtain quantitative first-order () and total-effect () sensitivity indices [20].

For a model , the Morris elementary effect (EE) for the i-th input at a sampling point with perturbation is defined as

Repeating the procedure over multiple, independent base points yields a sample of values for each parameter. The commonly reported statistics are the mean absolute elementary effect , which measures overall parameter importance, and the standard deviation , which indicates nonlinearity or interaction [21].

Morris screening was performed on nine candidate parameters (N, Cab, Car, Cw, Cm, LIDFa, LAI, hspot, and psoil) using 40 repeats and a perturbation amplitude equal to 10% of each parameter’s range. Parameters were ranked by and the top seven were retained for subsequent Sobol analysis.

Sobol variance decomposition was then applied to the selected seven-parameter subset. Using Monte Carlo sampling with a base sample size , we estimated first-order indices and total-effect indices across the 450–950 nm spectral interval. For summary reporting, wavelength-resolved and curves were averaged over 450–950 nm to yield scalar importance measures. The Sobol runs required a total of 9000 PROSAIL model evaluations. This hierarchical scheme reduces the dimensionality of the Sobol calculation while retaining the ability to quantify main effects and interactions reliably.

This apparent discrepancy highlights the different emphases of the two methods: Morris measures the absolute magnitude of local responses to finite perturbations and is therefore sensitive to parameters that induce strong spectral derivatives in localised wavelength bands [21]; Sobol indices quantify each parameter’s contribution to the overall output variance across the full input space [22]. Combining Morris screening and Sobol decomposition therefore provides an efficient strategy to (i) identify parameters that produce strong local spectral responses and (ii) select those that drive population-scale variance—a useful basis for reducing inversion dimensionality and for designing representative forward simulation libraries.

2.3.2. Synthetic Sample Generation

Guided by the sensitivity analysis, seven influential parameters were selected for sampling: N, Cab, Cm, Cw, LAI, psoil, and ALA. Each parameter was sampled independently from a uniform distribution over a physically plausible range to generate a synthetic ensemble of 30,000 parameter combinations (Table 2).

Table 2.

PROSAIL (version D) input parameters and sampling ranges used to generate the simulated dataset.

For each sampled parameter vector, PROSAIL produced a continuous reflectance spectrum . These spectra were convolved with the Sentinel-2B SRFs (Figure 2) to synthesise band-level bottom-of-atmosphere reflectances corresponding to bands B2, B3, B4, B7, and B8:

Figure 2.

Sentinel-2B SRFs for bands B2, B3, B4, B7 and B8.

These band-aggregated reflectances, together with the associated LAI values, formed a 30,000-sample simulated training library used for subsequent NN–GA model development and uncertainty quantification.

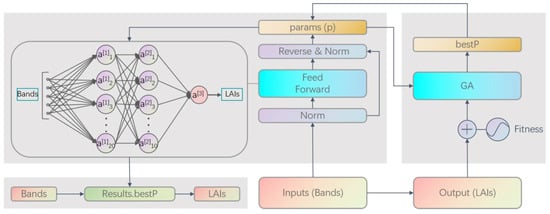

2.4. NN–GA Coupled Inversion Framework

A fully connected MLP with two hidden layers was adopted to map Sentinel-2B multispectral reflectances to LAI. The network accepts a 5-dimensional input vector (band reflectances B2, B3, B4, B7, and B8) and outputs a single scalar (LAI). The overall inversion architecture is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

NN–GA coupled inversion framework for LAI retrieval.

To promote global optimisation and explicitly favour generalisation, a population-based genetic algorithm [23,24,25] was used to optimise all network weights and biases. The PROSAIL-derived simulated dataset (30,000 samples) was randomly partitioned into training, validation, and test subsets in a 60:20:20 ratio, where the training portion supplies sufficient examples to fit the multi-parameter MLP, the validation portion is reserved to guide model selection and to guard against overfitting during optimisation, and the held-out test portion provides an unbiased estimate of final generalisation performance. All network parameters (weights and biases) were encoded as real-valued chromosomes and evolved by the GA. The GA fitness function was defined as a weighted sum of training and validation root-mean-square errors (RMSEs):

where denotes a GA individual encoding the network parameters, and are the index sets of training and validation samples with sizes and , respectively, is the reference (normalised) LAI of sample i, and is the MLP prediction under parameters . The validation error is weighted more heavily to explicitly promote generalisation during evolution and to mitigate overfitting.

Chromosome values were constrained to the interval [−5, 5]. The GA optimisation was executed independently 30 times and the individual with the best fitness was selected as the final network. We emphasise that the GA is not employed because the MLP is non-differentiable (the MLP and its activation functions are differentiable), but because evolutionary, population-based search offers practical advantages for this application. In particular, a GA enables the direct optimisation of bespoke, potentially non-differentiable fitness formulations (e.g., our weighted training/validation RMSE), explores highly non-convex and multimodal parameter landscapes to reduce sensitivity to initial weights and local minima, and naturally handles mixed or constrained parameter encodings and custom feasibility rules used during evolution [12,13]. These properties have motivated prior uses of evolutionary algorithms for neural-network training and are valuable when robustness, reproducibility, and custom fitness definitions are required. The NN–GA hybrid therefore marries the expressive power of the MLP with the GA’s global search capability to improve stability and generalisation when decoding simulated spectra and applying the trained model to Sentinel-2B imagery.

2.5. Accuracy Assessment

Model performance was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2) and the root-mean-square error (RMSE). R2 is defined as

where and are the observed and predicted LAI values, respectively, and is the mean of the observations. RMSE is defined as

Higher R2 values (approaching 1) and lower RMSE values (approaching 0) indicate better agreement between predictions and observations. These metrics were computed on the independent test sets and on the spatially co-located field observations used for Sentinel-2 validation.

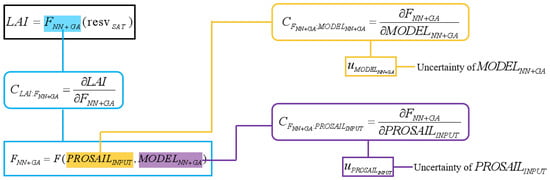

2.6. Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Method

Uncertainty quantification follows the measurement-model paradigm of the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) [26]: the quantity of interest is treated as a function of input quantities, and the propagation of their uncertainties through that function yields an uncertainty estimate for the output. In the LAI retrieval context, the measurement model can be written as

where denotes retrieved LAI and each input has an estimable central value and standard uncertainty .

Because LAI retrieval typically involves highly nonlinear, numerically driven algorithms, we use two complementary UQ approaches: the law of propagation of uncertainty (LPU), based on local linearization, and the Monte Carlo method (MCM), based on sampling [26,27,28]. The LPU employs a first-order Taylor expansion to linearize the measurement function locally and propagates input uncertainties via analytical or numerical derivatives. In contrast, MCM draws large numbers of samples from the input error (or prior) distributions, propagates each sample through the full (possibly nonlinear, black-box) retrieval pipeline, and empirically approximates the resulting output distribution [29].

2.6.1. Physics-Driven-Stage Uncertainty

In this study, the physics-driven-stage is defined as the propagation of uncertainty arising from variability in non-LAI PROSAIL inputs (e.g., Cab, Cm, Cw, N, psoil, ALA) through the forward model and the Sentinel-2 spectral response convolution into band reflectances. For the physics-driven component, and for each fixed LAI level, non-LAI PROSAIL inputs are modelled as truncated normal perturbations . The nominal value is set to the midpoint of the prescribed range and is set to one-sixth of the range so that approximately covers the interval. For a given LAI level, N Monte-Carlo draws are drawn from the joint (marginal, initially independent) distributions and each sample is propagated through PROSAIL and the Sentinel-2 SRFs to produce band reflectances . From the output sample set , the sample mean and the relative standard uncertainty associated with perturbations of the inputs can be computed. In particular, the relative uncertainty induced by the input ensemble is estimated as the coefficient of variation in the output:

To account for statistical dependence between PROSAIL inputs, pairwise associations between input-induced output responses are estimated and propagated. For two distinct inputs and , the corresponding output response vectors and are formed (each obtained by perturbing one parameter while sampling others). The Pearson correlation coefficient between these two response series is computed as

where and are the sample means of and , respectively. The corresponding error covariance is then approximated by

With per-input variances and covariances thus estimated, the law of propagation of uncertainty (LPU) is applied to obtain the band-level output variance for the forward model :

The sensitivity coefficients are evaluated numerically by central finite differences (appropriate when no closed-form derivative is available) [30]:

With step h set to 1% of the corresponding input parameter range. In addition, to represent small sensor–scene geometry jitter during inversion, we independently perturb the observation geometry (solar zenith tts, sensor zenith tto, and relative azimuth psi) by ±1% when propagating uncertainties. For a fixed LAI level, this procedure yields band-level relative uncertainties for each Sentinel-2 band b. The bandwise uncertainties are then combined into a single physics-driven-stage uncertainty for that LAI level by a weighted-variance sum:

where denotes the weight assigned to band b. It should be noted that band-width weighting is a pragmatic and computationally efficient approximation to account for differing spectral information content and to partially accommodate inter-band correlation.

Finally, the representative physics-driven-stage uncertainty reported in the paper is obtained by RMS aggregation over a discrete set of LAI levels:

This workflow preserves the sample-based strengths of Monte-Carlo propagation while introducing a straightforward, empirically grounded estimate of input parameter dependence. The approach balances improved realism (through covariance terms) with computational tractability for the multi-parameter PROSAIL forward model.

2.6.2. Machine-Learning-Stage Uncertainty

To quantify uncertainty arising from the stochasticity of the NN–GA training, the full training pipeline was repeated R independent times to produce R trained models. Using an NDVI-guided sampling strategy, representative pixels were drawn from the target scene. Let denote the LAI predicted for pixel p by model j. For each pixel, we compute the model mean and the absolute standard uncertainty:

And the pixelwise relative training uncertainty is . The summary machine-learning-stage relative uncertainty is the RMS over the sampled pixels:

2.6.3. Uncertainty Combination

The total uncertainty of a single LAI retrieval is decomposed into two stage-wise components (Figure 4). Building on the pixelwise machine-learning-stage uncertainty estimates, we compute the corresponding pixelwise physics-driven-stage uncertainties for the selected sample pixels and then evaluate the statistical dependence between the two components. The total variance is therefore expressed as

where denotes the physics-driven-stage relative standard uncertainty and denotes the machine-learning-stage relative standard uncertainty. The term is the covariance between the two stage-wise relative uncertainties (evaluated across the representative pixel set). In practice, we estimate this covariance empirically as the sample covariance over representative pixels:

where and are the sample means. If the empirical covariance is negligible, Equation (17) reduces to the usual LPU (quadrature) combination ; otherwise, the covariance term is retained to account for statistical dependence between the two stages.

Figure 4.

Uncertainty decomposition and computational workflow for LAI retrieval.

2.7. Workflow Summary

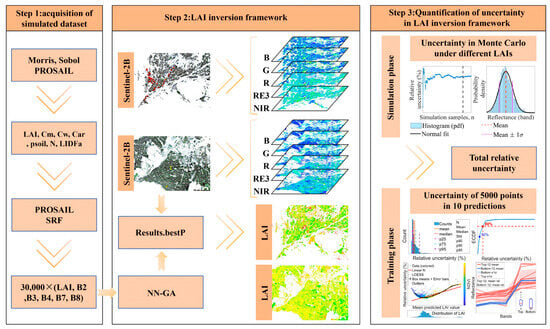

The technical workflow of the proposed physics-driven machine-learning framework is summarised in Figure 5 and comprises three sequential steps. In Step 1, a hierarchical sensitivity analysis (Morris screening followed by Sobol decomposition over 450–950 nm) identified seven influential PROSAIL inputs; PROSAIL was sampled across prior ranges and simulated spectra were convolved with Sentinel-2B SRFs to synthesise a 30,000-sample five-band BOA reflectance library (B2, B3, B4, B7, B8). In Step 2, a two-hidden-layer MLP was trained on the simulated library with all weights and biases globally optimised by a GA (NN–GA); the optimal model was then applied to Sentinel-2B reflectance imagery to produce spatial LAI maps. In Step 3, the total relative uncertainty of the LAI product was decomposed into the physics-driven-stage component (uncertainty propagated from non-LAI PROSAIL input variability to band reflectances, quantified by MCM) and the machine-learning-stage component (prediction variability across repeated NN–GA trainings); each component was quantified independently and the two standard uncertainties were combined under the LPU to produce per-retrieval relative uncertainty estimates for the LAI maps.

Figure 5.

Workflow diagram illustrating computational steps for coupled PROSAIL–NN–GA LAI retrieval and uncertainty quantification.

3. Results

3.1. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Sample Generation Based on the PROSAIL Model

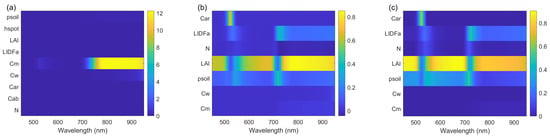

A hierarchical sensitivity-analysis protocol combining Morris screening and Sobol variance decomposition was applied to quantify the sensitivity of PROSAIL-simulated reflectance across 450–950 nm. The wavelength-resolved outcomes are summarised in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis results for PROSAIL-simulated reflectance (450–950 nm). (a) Morris heatmap showing the mean absolute elementary effects of model inputs across wavelength; (b) Sobol first-order index heatmap indicating the fraction of output variance attributable to each input; (c) Sobol total-effect index heatmap representing each input’s overall contribution including interactions.

Morris screening (averaged across 450–950 nm) ranked the top seven parameters by the mean absolute elementary effect as: ( = 5.1220), ( = 0.1244), ( = 0.0670), LAI ( = 0.0254), N ( = 0.0241), LIDFa ( = 0.0012), and ( = 0.0005). The Morris results indicate that produces substantially larger local responses than the other parameters in the 700–950 nm region; i.e., the model exhibits high local sensitivity to in the NIR.

Sobol variance decomposition applied to the Morris-selected subset provided complementary, population-level information. Averaged over 450–950 nm, LAI dominates the simulated reflectance variance: the mean first-order index for LAI is ≈0.64 (64%) and the mean total-effect index is ≈0.75 (75%), indicating that LAI accounts for the largest share of output variance with only partial entanglement in interactions. By contrast, although ranks highest in Morris, its mean Sobol first-order contribution is small (mean ), reflecting that ’s strong influence is concentrated in a limited spectral/parameter region and therefore contributes little to the global variance under the prescribed input distributions.

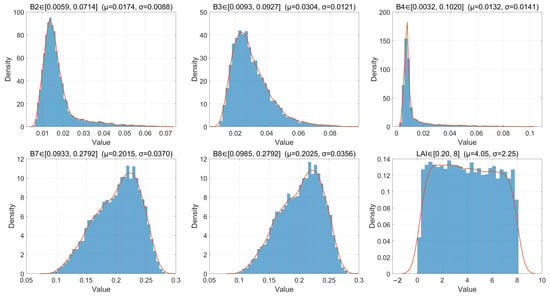

Guided by the sensitivity analysis, seven influential parameters (listed above) were sampled uniformly within physically plausible priors to generate the synthetic dataset. PROSAIL spectra were convolved with the Sentinel-2B SRFs to produce band-level (B2, B3, B4, B7, B8) bottom-of-atmosphere reflectances paired with LAI. The resulting simulated data distributions for the site are shown as histograms with kernel density estimates in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Distributions (histogram + kernel density estimate) of the simulated Sentinel-2B five-band reflectances (B2, B3, B4, B7, B8) and associated LAI values used for model training and uncertainty analysis (30,000 samples).

3.2. Crop LAI Retrieval and Accuracy Analysis Based on NN–GA

3.2.1. Crop LAI Retrieval

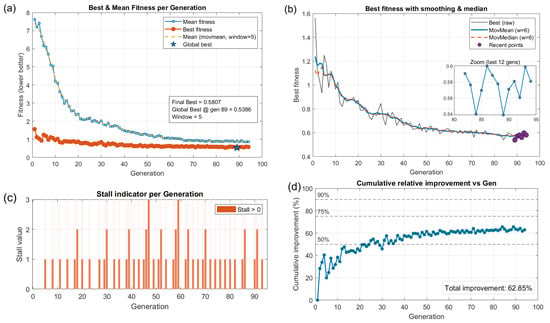

The convergence, stability, and generalisation behaviour of the NN–GA training were examined via the diagnostic metrics summarised in Figure 8. The diagnostics include: generation-wise best and mean fitness, a smoothed view of the best fitness trend (moving average and median), a per-generation stall indicator, and the cumulative relative improvement referenced to generation 1.

Figure 8.

Training optimisation diagnostics for the NN–GA inversion framework. (a) Best and mean fitness per generation; (b) smoothed best fitness trend (moving average and median); (c) per-generation stall indicator; (d) cumulative relative improvement versus generation 1 (percentage).

At initialization, the best individual fitness was 1.56; the algorithm reduced this value rapidly during early evolution, reaching the run minimum of 0.5386 at generation 89 and finishing with a best-of-run value of 0.58 at the final generation (i.e., the final best is slightly above the observed run minimum). The population mean fitness fell from 7.62 at initialization to ≈0.87 at termination, indicating consistent improvement across the population as a whole. Most of the aggregate fitness reduction occurred in the early-to-mid phase of the run (roughly generations 10–40), corresponding to broad global exploration; later generations produced smaller, incremental gains consistent with local exploitation and fine-tuning. Calculating relative improvement from the initial best to the run minimum gives (1.56 − 0.5386)/1.56 ≈ 66%. Performance on the simulated test data indicates that the NN–GA framework locates stable, high-quality solutions: the training-set RMSE was 0.73 and the independent test-set RMSE was 0.85, demonstrating reasonable generalisation while leaving scope for further improvements (e.g., cross-validation or local fine-tuning). Overall, the GA-based global search efficiently identified promising regions of the parameter space and produced reproducible network solutions suitable for application to Sentinel-2B imagery.

3.2.2. Accuracy Assessment of LAI Retrieval

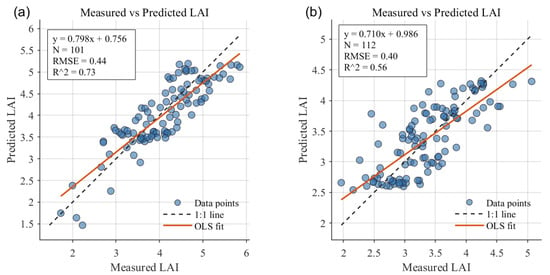

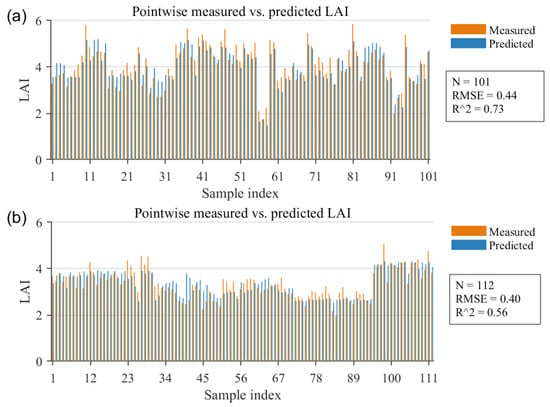

To assess the practical performance and transferability of the trained NN–GA mapping, we applied the model to near-synchronous Sentinel-2B scenes and validated the pixelwise retrievals against LI-COR LAI-2200 field measurements. The spatial distributions of predictions and validation samples for Minqin (modelling/testing area) and Zhangye (transfer/validation area) are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Spatial distributions of predicted LAI and ground-sample locations. (a) True-colour composite of the Minqin site; red triangles denote LAI-2200 measurement locations. (b) True-colour composite of the Zhangye site; yellow triangles denote LAI-2200 measurement locations. (c) LAI retrieval map for Minqin. (d) LAI retrieval map for Zhangye.

Pointwise comparison (Figure 10 and Figure 11) returns the following validation statistics: Minqin (101 measured points)—RMSE = 0.44, R2 = 0.73; Zhangye (112 measured points)—RMSE = 0.40, R2 = 0.56. The Minqin results show tighter scatter about the 1:1 line and higher explained variance, whereas the Zhangye results exhibit greater dispersion and unexplained variability despite a comparable RMSE.

Figure 10.

Observed versus predicted LAI (LAI-2200 vs. NN–GA). (a) Minqin (101 measured points). (b) Zhangye (112 measured points). Dashed line: 1:1 reference; solid line: least-squares regression.

Figure 11.

Observed versus predicted LAI (LAI-2200 vs. NN–GA) shown as point-by-point bar charts. (a) Minqin (101 measured points). (b) Zhangye (112 measured points). Orange and blue bars indicate measured and predicted values, respectively.

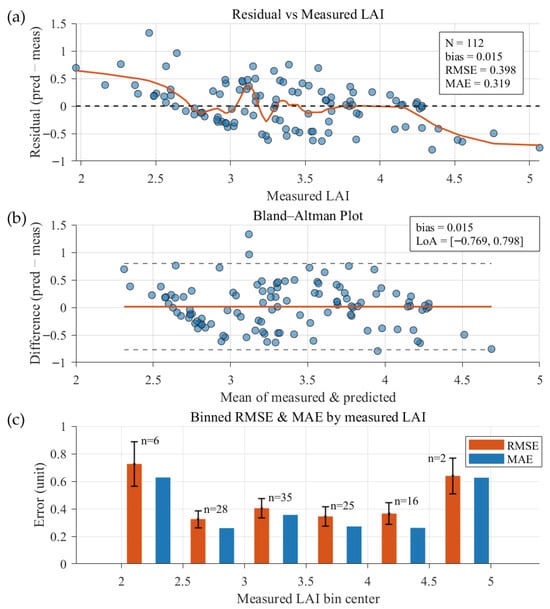

Residual diagnostics for Zhangye (Figure 12) indicate a small overall bias (0.015) and a weak pattern of overestimation at low LAI and underestimation at high LAI, with near-zero bias in the midrange (≈2.75–4.25).

Figure 12.

Residual analysis for Zhangye (Site 2; 112 measured points). (a) Residuals vs. measured LAI with a LOESS smoothed trend line; (b) Bland–Altman plot showing the mean bias (0.015, solid line) and 95% limits of agreement (dashed lines); (c) Binned error statistics grouped by measured LAI. Orange and blue bars denote RMSE and MAE, respectively; error bars represent the standard error.

Bland–Altman analysis produces 95% limits of agreement of approximately [−0.77, 0.80], implying that individual prediction errors can reach on the order of ±0.8 LAI units. Binned error statistics reveal a U-shaped dependence on observed LAI: both RMSE and MAE increase at low (<2.5) and high (>4.5) LAI, with several extreme residuals located in the distribution tails.

In summary, the NN–GA framework provides satisfactory LAI estimates at both sites (Zhangye: RMSE = 0.40, MAE = 0.32, R2 = 0.56), with stronger agreement at the model-development site. The error patterns—poorer performance at very low and very high LAI and the presence of outliers—are plausibly attributable to factors such as crop structural anomalies during the satellite overpass (e.g., exposed ears/inflorescences and altered leaf-angle distributions associated with tasseling) that increase optical heterogeneity [31], and to optical saturation and background-mixing effects that disproportionately affect extreme LAI values [32]. These observations motivate the following section’s systematic uncertainty decomposition of the retrieval chain, which aims to identify dominant error sources and guide targeted improvements.

3.3. Quantification of LAI Retrieval Uncertainty via a Coupled Physics-Driven and Machine-Learning Approach

We decompose and quantify two stochastic uncertainty sources in the retrieval chain: the physics-driven-stage uncertainty arising from variability of non-LAI PROSAIL inputs propagated to Sentinel-2 band reflectances, and the machine-learning-stage uncertainty arising from variability across repeated NN–GA trainings. Below, we summarise the physics-driven-stage analysis and present band-wise and aggregated uncertainty results; Machine-Learning-Stage diagnostics follow.

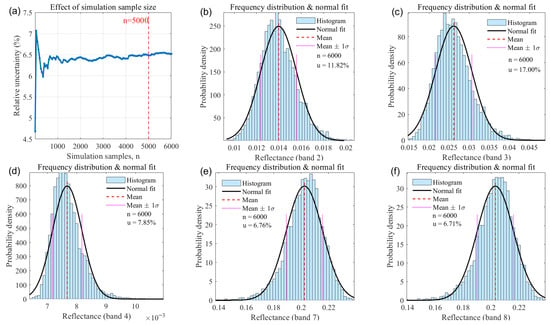

To determine a stable Monte-Carlo sample size for the physics-driven-stage propagation, we examined the convergence of the estimated output uncertainty for a representative case with LAI fixed at 3. As shown in Figure 13, the estimated standard relative uncertainty decreases and stabilises as the number of Monte-Carlo draws N increases; beyond N ≈ 5000, the uncertainty curve is effectively converged and fluctuations are substantially reduced. Balancing statistical stability and computational cost, we therefore adopted N = 6000 for all subsequent Monte-Carlo runs.

Figure 13.

Physics-driven-stage uncertainty diagnostics and bandwise reflectance perturbation distributions (LAI = 3). (a) Monte Carlo convergence of the estimated standard relative uncertainty as a function of sample size (diagnostic used to select N = 6000); (b–f) show the bandwise reflectance distributions under parameter perturbations for Sentinel-2B bands B2, B3, B4, B7, and B8 (MinQin).

Applying the same Monte-Carlo propagation across the sampled LAI range, Table 3 and Table 4 summarise the band-wise relative uncertainties and the aggregated (combined) standard relative uncertainty for Minqin (modelling/testing area) and Zhangye (transfer/validation area), respectively. When LAI is fixed and other PROSAIL inputs are perturbed within the prescribed prior ranges, the aggregated physics-driven-stage standard relative uncertainties are 11.42% for Minqin and 11.48% for Zhangye. The slightly larger value for Zhangye primarily reflects differences in the prescribed prior ranges (notably the soil-background factor psoil) used in the two site-specific simulations. Band- and LAI-resolved patterns in Table 3 and Table 4 indicate that relative uncertainty depends on both LAI and wavelength: certain bands (e.g., B3 and B4 in several LAI bins) exhibit higher relative uncertainty, and the aggregated uncertainty varies across LAI levels where spectral sensitivity to perturbed inputs is larger. These estimates form the basis for combination with machine-learning-stage uncertainty and for producing uncertainty maps of the final LAI product.

Table 3.

Band-wise and aggregated physics-driven-stage uncertainties for Minqin (modelling/testing area), listed by LAI bin.

Table 4.

Band-wise and aggregated physics-driven-stage uncertainties for Zhangye (transfer/validation area), listed by LAI bin.

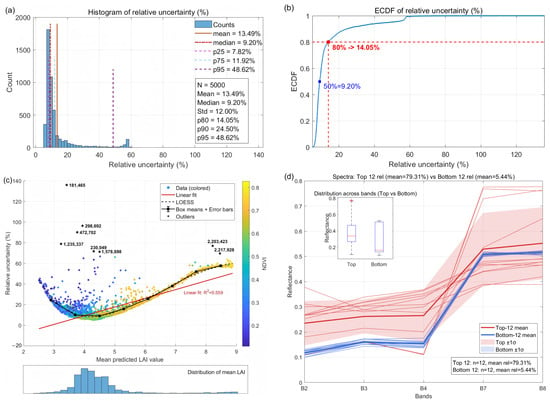

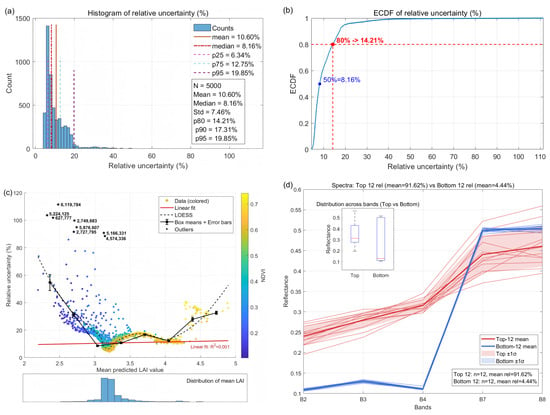

For the machine-learning-stage, the complete NN–GA training pipeline was repeated R = 10 independent times to produce R trained models. Using NDVI-guided sampling of the target scenes, M = 5000 representative pixels were drawn and each pixel was predicted by the R models. The aggregated machine-learning-stage standard relative uncertainty was then computed as the root-mean-square (RMS) of pixelwise relative standard deviations. The resulting values are = 18.06% for Minqin and = 12.96% for Zhangye, indicating that stochastic factors in NN–GA training (e.g., random initialization and evolutionary search variability) substantially affect output stability.

Figure 14 and Figure 15 present summary diagnostics of per-pixel machine-learning-stage relative uncertainty for Minqin and Zhangye, respectively. For Minqin (Figure 14), 75% of the sampled pixels have relative uncertainty ≤ 11.9% and 80% ≤ 14.1%; the empirical cumulative distribution shows a slow rise across the lower 80% and a steeper tail across the upper 20%, indicating a minority of pixels with markedly higher training uncertainty. A LOESS-smoothed scatter of mean predicted LAI versus relative uncertainty reveals a U-shaped dependence: uncertainty is elevated at low (≤2) and high (≥6) LAI and minimal in the mid-range (3–6). Spectral inspection shows that many high-uncertainty pixels are mixed-boundary pixels (vegetation–soil/road), supporting the hypothesis that mixed pixels and limited training coverage in distribution tails drive elevated training uncertainty. Zhangye (Figure 15) displays broadly similar behaviour, indicating spatial transferability of the NN–GA uncertainty patterns.

Figure 14.

Comprehensive analysis of per-pixel machine-learning-stage relative uncertainty for Minqin (M = 5000). (a) Histogram; (b) ECDF; (c) mean predicted LAI vs. relative uncertainty with LOESS smoothing (point colour indicates NDVI); (d) mean spectra for Top-12 and Bottom-12 pixels.

Figure 15.

The same diagnostics as Figure 14, but for Zhangye.

We evaluated the statistical dependence between the physics-driven and machine-learning stage uncertainties and quantified its effect on the combined retrieval uncertainty. The results are reported for two study areas (N = 5000 sample pixels each).

In Minqin, the sample means of the stage-wise relative standard uncertainties are and . The paired-sample Pearson correlation between these per-pixel uncertainties is (two-sided ); a permutation test (2000 permutations) confirms that this correlation is highly unlikely under the null hypothesis of independence (permutation ). Bootstrap estimation (B = 2000) yields with 95% CI = . Substituting the empirically estimated covariance into Equation (17), the combined standard uncertainty increases from ≈0.1743 (covariance neglected) to ≈0.1752 (with covariance), corresponding to an absolute increase of ≈ and a relative change of about +0.47%. In Zhangye, we find , , Pearson (two-sided ), and bootstrap covariance (95% CI = ). Including this covariance increases the combined standard uncertainty from ≈0.1488 to ≈0.1491, an absolute change of or +0.19% relative.

Overall, although a weak but statistically significant positive correlation between the two stage-wise uncertainties is observed in both regions, the covariance term has a negligible numerical impact on the final combined uncertainty (well below 1% relative). The physics-driven-stage standard uncertainty and the machine-learning-stage standard uncertainty were combined according to the law of propagation of uncertainty (root-sum-square of independent standard uncertainties) to yield the final per-retrieval relative uncertainty. Table 5 lists the combined results. After combination, the single-retrieval relative uncertainties are 21.37% for Minqin and 17.31% for Zhangye. Both values exceed the GCOS reference target of 15% for certain biophysical products, indicating that further methodological improvements—for example, refined sampling strategies, explicit handling of mixed pixels, inclusion of ancillary indices such as NDVI, or multisource data fusion—will be required to reach climate-grade uncertainty levels.

Table 5.

Final relative uncertainties for single LAI retrievals after combination of physics-driven-stage and machine-learning-stage components.

In summary, the staged UQ procedure identifies dominant contributors to retrieval uncertainty and points to concrete mitigation strategies (e.g., targeted augmentation of training samples in extreme LAI regimes, mixed-pixel treatment, and reduction in training stochasticity) that can directly reduce the overall LAI product uncertainty.

4. Discussion

4.1. Method Performance and Comparison

SL2P (Simplified Level-2 Product Processor) is a canopy biophysical retrieval algorithm developed by the European Space Agency for Sentinel-2 data [33]. The method uses feed-forward neural networks trained on a radiative-transfer model simulation library to combine physical realism with the computational speed of empirical retrievals [34]. SL2P is capable of efficiently estimating key biophysical variables from Sentinel-2 imagery, including leaf area index (LAI), fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (fAPAR), and fractional vegetation cover (FVC). Because SL2P delivers consistent wall-to-wall estimates at 10 m resolution and has been widely adopted as a baseline algorithm, we selected it as the primary retrieval method for this study [35].

In this work, we ran the SL2P implementation available in SNAP’s S2_10m Biophysical Processor (SNAP v10.0.0). The processor was supplied with Sentinel-2 Level-2A bottom-of-atmosphere (BOA) reflectance as input and was executed with its default configuration: no user-tunable lookup tables (LUTs), priors, or inversion parameters were modified. Output biophysical products were quality-filtered using the Scene Classification Layer (SCL) to remove clouds, cloud shadow, and other invalid pixels. Because the S2_10m configuration uses only the 10 m bands, the resulting LAI, fAPAR, and FVC products are provided at 10 m spatial resolution.

The NN–GA retrieval was validated against site-level LI-COR LAI-2200 measurements. Pointwise statistics are: Minqin (modelling/testing area; 101 measured points)—RMSE = 0.44, R2 = 0.73; Zhangye (transfer/validation area; 112 measured points)—RMSE = 0.40, R2 = 0.56. For benchmarking, we compared these results with operational Sentinel-2 LAI estimates from the SNAP/SL2P processor evaluated on the same validation sets: Minqin (SL2P)—RMSE = 0.83, R2 = 0.04; Zhangye (SL2P)—RMSE = 0.61, R2 = −0.03. Under the present data and parameter settings, the NN–GA framework substantially reduces absolute error (∆RMSE ≈ 0.39, ∼47% relative improvement for Minqin; ∆RMSE ≈ 0.21, ∼35% for Zhangye) and markedly increases explained variance versus the SL2P baseline.

Observed differences between the two study areas are largely attributable to sampling design and sample representativeness. Minqin was sampled sparsely across the landscape (101 points, inter-point distance ≥ 300 m) to capture regional heterogeneity, whereas Zhangye used dense, within-field sampling (≈81 points per 48 × 48 m plot) to represent pixel-scale variability. Sparse designs tend to enlarge the reference variance and—when a model captures broad spatial contrasts—may yield higher R2, but they also increase the risk of pixel–plot mismatch and measurement noise, which can inflate RMSE. Conversely, dense sampling typically reduces pixel–plot mismatch and RMSE, but may lower R2 because of reduced sample variance. These sampling effects also help explain differences in SL2P performance across sites. Accordingly, algorithm comparisons and validation statements should explicitly account for sampling strategy and scale; we recommend reporting stratified or weighted validation statistics and clearly documenting sampling layouts to enable fair, reproducible assessments.

Overall, the NN–GA framework shows improved absolute accuracy and explanatory power relative to the SNAP/SL2P benchmark in our experiments, indicating stronger fit and transfer potential under the tested conditions. Nonetheless, the evaluation underscores that sampling design and measurement repeatability remain critical determinants of apparent performance and should be integral to future method comparisons and operational assessments.

4.2. Analysis of Uncertainty Sources

The two study areas exhibited broadly consistent uncertainty patterns (distributional shapes, LOESS-indicated nonlinearity, and the spectral/spatial characteristics of high-uncertainty pixels), suggesting that the proposed NN–GA retrieval and the staged UQ workflow generalise across the regions and phenological stages examined. Quantitatively, the machine-learning-stage uncertainty was comparable to or larger than the physics-driven-stage uncertainty: = 18.06%/12.96% versus = 11.42%/11.48% for Minqin/Zhangye, respectively. This finding indicates that stochasticity in model training (e.g., random initialisation, evolutionary search variability, and hyperparameter choices) is a major contributor to overall retrieval variance and therefore a primary target for improvement.

We also note key simplifying assumptions in the present UQ analysis that may bias the absolute numerical estimates: (i) non-LAI PROSAIL inputs were modelled as truncated normal perturbations with independently applied draws; (ii) input parameter correlations were neglected; and (iii) NDVI-guided pixel sampling was used as a proxy for scene variability. These choices were adopted for tractability and reproducibility but restrict the interpretation of the reported uncertainty as a baseline conditional on the stated assumptions. Future work should relax these assumptions by explicitly incorporating parameter covariances, enlarging the prior sample space and observational constraints, and by adopting fully probabilistic (e.g., Bayesian) UQ approaches that jointly estimate parameter posteriors and predictive uncertainty. Additional practical avenues to reduce total uncertainty—suggested by our diagnostics—include (a) reducing training stochasticity via ensemble/aggregation methods, systematic hyperparameter optimisation, or regularisation; (b) targeted augmentation of training samples in LAI distribution tails; (c) explicit treatment of mixed pixels (sub-pixel unmixing or masking); and (d) fusion with ancillary sources (e.g., higher-resolution UAV data, topographic data, or management metadata). Implementing these strategies is expected to lower both the machine-learning-stage and physics-driven-stage contributions and to move operational LAI retrievals closer to application-level uncertainty targets.

5. Conclusions

We developed and validated a physics-driven machine-learning framework for crop Leaf Area Index (LAI) retrieval that jointly addresses accuracy and end-to-end UQ. The approach couples PROSAIL forward simulations (convolved with Sentinel-2B SRFs) to construct a 30,000-sample training library, trains a two-hidden-layer multilayer perceptron whose weights and biases are globally optimised by a genetic algorithm (NN–GA), and implements a two-stage uncertainty workflow: Monte-Carlo propagation to characterise uncertainty arising in the physics-driven-stage, and repeated independent NN–GA trainings to quantify uncertainty originating in the machine-learning-stage. The two standard uncertainty components are combined according to the law of propagation of uncertainty to yield a single, reproducible estimate of retrieval uncertainty.

A hierarchical sensitivity analysis confirmed that LAI is the dominant driver of reflectance variance across the visible–near-infrared bands considered, justifying the chosen parameter reduction and guiding efficient sampling. Validation against LI-COR LAI-2200 measurements at two northwest China sites demonstrates robust retrieval performance and cross-site transferability: Minqin (modelling/testing site) achieved RMSE = 0.43 and R2 = 0.73, while Zhangye (transfer/validation site) achieved RMSE = 0.40 and R2 = 0.56. Compared with the SNAP/SL2P baseline, the NN–GA framework substantially reduced absolute error and increased explained variance at the sample scale.

The staged uncertainty decomposition exposes the relative contributions of the retrieval chain: physics-driven-stage standard relative uncertainties were 11.42% (Minqin) and 11.48% (Zhangye), while machine-learning-stage standard relative uncertainties were 18.06% (Minqin) and 12.96% (Zhangye). After variance synthesis, the single-run relative uncertainties are 21.37% (Minqin) and 17.31% (Zhangye). These results indicate that, under the current implementation, stochasticity associated with model training (initialization, hyperparameter search, and optimisation variability) is a major contributor to total uncertainty; reducing training variability (for example, via ensemble strategies, more systematic hyperparameter optimisation, or regularisation) should therefore be a priority to lower final product uncertainty.

In conclusion, the proposed NN–GA retrieval pipeline advances 10 m Sentinel-2 crop LAI estimation by combining improved accuracy with a transparent, reproducible uncertainty-quantification workflow. The framework supplies actionable uncertainty diagnostics that can guide targeted algorithmic improvements and supports the production of confidence-aware LAI products for agricultural monitoring and downstream applications. Future work should focus on (i) reducing machine-learning-stage stochasticity, (ii) incorporating parameter correlations and Bayesian UQ to relax current assumptions, and (iii) exploring multi-source data fusion and mixed-pixel handling to further tighten uncertainty and broaden operational applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. and X.Z.; methodology, W.L. and S.Y.; software, W.L. and S.Y.; validation, X.Z. and Z.G.; formal analysis, W.L. and S.Y.; investigation, W.L. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L. and S.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and Z.G.; supervision, X.Z. and Z.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFB3905804; 2022YFB3903501), Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, China (2025CXGC010113); and the Future-Star program of the Aerospace Information Research Institute (E2Z106010F).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, the data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of the Sentinel-2 Level-2A (MSI) product from the Copernicus Programme/European Space Agency (ESA), accessed via the Google Earth Engine platform. We thank the teams at ESA/Copernicus for their support and for providing the data that have been essential to our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, J.M.; Black, T.A. Defining leaf area index for non-flat leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 1992, 15, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belward, A.; Bourassa, M.; Dowell, M.; Briggs, S.; Dolman, H.A.J.; Holmlund, K.; Husband, R.; Quegan, S.; Simmons, A.; Sloyan, B.; et al. The Global Observing System for Climate: Implementation Needs; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Yin, T.; Dissegna, M.A.; Whittle, A.J.; Ow, G.L.F.; Yusof, M.L.M.; Lauret, N.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J. An assessment study of three indirect methods for estimating leaf area density and leaf area index of individual trees. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 292, 108101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Verger, A.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xu, B.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, J.; Liu, Q. Retrieval of High Spatiotemporal Resolution Leaf Area Index with Gaussian Processes, Wireless Sensor Network, and Satellite Data Fusion. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Verhoef, W.; Baret, F.; Bacour, C.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Asner, G.P.; François, C.; Ustin, S.L. PROSPECT + SAIL models: A review of use for vegetation characterization. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, S56–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, R.; Bellingeri, D.; Fasolini, D.; Marino, C.M. Retrieval of leaf area index in different vegetation types using high resolution satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Liang, S.; Kuusk, A. Retrieving leaf area index using a genetic algorithm with a canopy radiative transfer model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 85, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Taberner, M.; Moreno-Martínez, Á.; García-Haro, F.J.; Camps-Valls, G.; Robinson, N.P.; Kattge, J.; Running, S.W. Global Estimation of Biophysical Variables from Google Earth Engine Platform. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guisuraga, J.M.; Verrelst, J.; Calvo, L.; Suárez-Seoane, S. Hybrid inversion of radiative transfer models based on high spatial resolution satellite reflectance data improves fractional vegetation cover retrieval in heterogeneous ecological systems after fire. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 255, 112304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Atzberger, C.; Danner, M.; D Urso, G.; Mauser, W.; Vuolo, F.; Hank, T. Evaluation of the PROSAIL Model Capabilities for Future Hyperspectral Model Environments: A Review Study. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Jiang, L.; Yue, P.; Gong, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, S.; Tan, H.; Liu, C.; Shangguan, B.; Yu, D. A large scale training sample database system for intelligent interpretation of remote sensing imagery. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 1489–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.; Cortez, P.; Neves, J. Evolutionary Neural Network Learning. In Progress in Artificial Intelligence; Pires, F.M., Abreu, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, P.; Amato, A.; Venticinque, S. Cloud-based analysis of aerial imagery for unveiling ancient archaeological patterns. J. Cloud Comput. 2025, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.B.; Park, Y. MODIS Collection 6 (C6) LAI/FPAR Product User’s Guide; NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC (LP DAAC); USGS EROS Center: Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2020.

- Fang, H.; Wei, S.; Liang, S. Validation of MODIS and CYCLOPES LAI products using global field measurement data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 119, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Wang, J.; Peng, R.; Yang, K.; Chen, X.; Yin, G.; Dong, J.; Weiss, M.; Pu, J.; Myneni, R.B. HiQ-LAI: A high-quality reprocessed MODIS leaf area index dataset with better spatiotemporal consistency from 2000 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2024, 16, 1601–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlikowski, J.; Tassi, C.R.N.; Ali, M.; Lee, J.; Humt, M.; Feng, J.; Kruspe, A.M.; Triebel, R.; Jung, P.; Roscher, R.; et al. A survey of uncertainty in deep neural networks. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 56, 1513–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Zhou, P.; Chen, H.; Lei, S.; Tan, Z.; Huang, J.; Guo, Y. Process-Based Remote Sensing Analysis of Vegetation–Soil Differentiation and Ecological Degradation Mechanisms in the Red-Bed Region of the Nanxiong Basin, South China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.D. Factorial sampling plans for preliminary computational experiments. Technometrics 1991, 33, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, I.M. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Math. Comput. Simul. 2001, 55, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolongo, F.; Cariboni, J.; Saltelli, A. An effective screening design for sensitivity analysis of large models. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2007, 22, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Annoni, P.; Azzini, I.; Campolongo, F.; Ratto, M.; Tarantola, S. Variance based sensitivity analysis of model output. Design and estimator for the total sensitivity index. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010, 181, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Conn, A.R.; Gould, N.I.; Toint, P. A globally convergent augmented Lagrangian algorithm for optimization with general constraints and simple bounds. Siam J. Numer. Anal. 1991, 28, 545–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, A.; Gould, N.; Toint, P. A globally convergent Lagrangian barrier algorithm for optimization with general inequality constraints and simple bounds. Math. Comput. 1997, 66, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint, C.F.G.I. Evaluation of Measurement Data—Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement; Bureau International des Poids et Mesures: Sèvres, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.; Siebert, B. The use of a Monte Carlo method for evaluating uncertainty and expanded uncertainty. Metrologia 2006, 43, S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorroño, J.; Guanter, L.; Graf, L.V.; Gascon, F. A Framework for the Estimation of Uncertainties and Spectral Error Correlation in Sentinel-2 Level-2A Data Products. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5634613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolliams, E.; Hueni, A.; Gorroño, J. Intermediate Uncertainty Analysis for Earth Observation (Instrument Calibration Module): Training Course Textbook; National Physical Laboratory: Teddington, UK, 2015; pp. 14–28. Available online: https://www.meteoc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/35/2017/11/uaeo-int-trg-course-v2.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Leveque, R. Finite Difference Methods for Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations: Steady-State and Time-Dependent Problems; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, C.; Xu, B.; Feng, H.; Feng, Z.; Ren, L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Fine-Scale Quantification of the Effect of Maize Tassel on Canopy Reflectance with 3D Radiative Transfer Modeling. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, X.; Jing, X.; Geng, L.; Che, T.; Liu, L. Enhancing Leaf Area Index Estimation for Maize with Tower-Based Multi-Angular Spectral Observations. Sensors 2023, 23, 9121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Baret, F.; Jay, S. S2ToolBox Level 2 products: LAI, FAPAR, FCOVER; Version 2.1; INRAE: Avignon, France, 2020; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Najib, D.; Fernandes, R.; Sun, L.; Canisius, F.; Hong, G. Python Version of Simplified Level 2 Prototype Processor for Retrieving Canopy Biophysical Variables from Sentinel 2 Multispectral Instrument Data. 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/10654520 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Djamai, N.; Zhong, D.; Fernandes, R.; Zhou, F. Evaluation of Vegetation Biophysical Variables Time Series Derived from Synthetic Sentinel-2 Images. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).