Highlights

What are the main findings?

- One of the first comprehensive InSAR-based subsidence maps of Mandalay, Myanmar, revealing the fastest rates up to −217 mm/yr in urban expansion zones.

- DTLCS-AHC clustering identifies four distinct deformation patterns, linking severe subsidence to irreversible, non-seasonal ground compaction.

What is the implication of the main findings?

- The results highlight the combined impact of anthropogenic activity, precipitation, geology and ground water on urban land stability.

- The framework enables unsupervised, shape-aware pattern recognition in time-series InSAR data for scalable urban geological hazard monitoring.

Abstract

Urban land subsidence poses a significant threat in rapidly urbanizing regions, threatening infrastructure integrity and sustainable development. This study focuses on Mandalay, Myanmar, and presents a novel clustering framework—Dynamic Time Warping and Trend-based Longest Common Subsequence with Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (DTLCS-AHC)—to classify spatiotemporal deformation patterns from Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) time series derived from Sentinel-1A imagery covering January 2022 to March 2025. The method identifies four characteristic deformation regimes: stable uplift, stable subsidence, primary subsidence, and secondary subsidence. Time–frequency analysis employing Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) reveals seasonal oscillations in stable areas. Notably, a transition from subsidence to uplift was detected in specific areas approximately seven months prior to the Mw 7.7 earthquake, but causal relationships require further validation. This study further establishes correlations between subsidence and both urban expansion and rainfall patterns. A physically informed conceptual model is developed through multi-source data integration, and cross-city validation in Yangon confirms the robustness and generalizability of the approach. This research provides a scalable technical framework for deformation monitoring and risk assessment in tropical, data-scarce urban environments.

1. Introduction

As the global urban population continues to grow [1] and urbanization accelerates, intensified human activities can destabilize urban land surfaces, thereby contributing to extensive city-wide subsidence [2]. Land subsidence is a widespread geological hazard affecting major cities around the world [3]. It not only compromises urban safety but also poses serious threats to infrastructure, urban planning, and residents’ quality of life [4]. Over recent years, numerous cities globally have experienced severe ground subsidence [5,6,7,8,9]. In Kolkata, India, during the period 2017–2021, widespread subsidence was observed, with multiple localized patches exhibiting significant deformation rates exceeding −10 mm/yr, as revealed by InSAR and Global Positioning System (GPS) measurements [10]. Similarly, in Dhaka, Bangladesh, accelerated subsidence was detected in the newly developed Jolshiri Abashon residential area on the city’s eastern outskirts between 2017 and 2022. Maximum deformation rates reached −55.7 mm/yr, with cumulative displacement exceeding −700 mm over the study period [11]. In Tehran, Iran, land subsidence rates as high as −217 mm/yr were observed in the southwestern part of the metropolitan area from 2017 to 2019 [12]. At the national scale, a comprehensive analysis of 82 major Chinese cities from 2015 to 2022 revealed that 15.8% of urban pixels exhibited rapid subsidence (<−10 mm/yr), while 5% of urban land areas subsided at rates exceeding −22 mm/yr [2].

InSAR has become a widely used tool for monitoring ground deformation due to its high precision, wide-area coverage, and ability to operate without ground-based instruments. It has been successfully applied in various fields, including volcano deformation monitoring [13], infrastructure monitoring [14], and urban surface change detection [15]. Multi-Temporal InSAR (MT-InSAR) is especially effective for monitoring urban ground deformation. Among MT-InSAR methods, the Small Baseline Subset (SBAS-InSAR) technique uses multiple reference images and time-series analysis to reduce errors caused by spatial and temporal decorrelation. This makes SBAS-InSAR well suited for monitoring complex areas such as mining zones and cities.

Many studies have used MT-InSAR to detect land deformation in urban areas (e.g., Mexico City [16], Hanoi, Vietnam [17], Shanghai [18], and Xi’an [19]). The reliability of these InSAR results has been confirmed by comparison with leveling measurements [20,21]. In addition, ref. [22] applied time-series analysis to post-process displacement data from PS-InSAR. They used Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and Seasonal-Trend Decomposition (STL) based on loess to estimate seasonal components of deformation on the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge. Their study showed that after removing linear and seasonal trends, sudden changes in the time series could be clearly identified. These examples highlight the effectiveness and reliability of InSAR and MT-InSAR techniques in monitoring and analyzing surface deformation in city areas.

As the capital of Myanmar’s central dry region, Mandalay is not only the nation’s second-largest city with a population over 1.7 million but is also widely regarded as the cultural and Buddhist heart of the country. It occupies a strategic position at the crossroads of vital trade routes connecting China, India, and Southeast Asia. Its infrastructure stability directly affects the resilience of its transportation networks, urban services, and densely populated built environment. Since 1990, the city has experienced rapid growth, with an annual rate of nearly 3% [23]. The combination of excessive groundwater dependence [24] and unfavorable subsurface geology substantially increases the susceptibility of Mandalay to surface deformation. Currently, official surface deformation monitoring in Myanmar relies mainly on Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) stations, which has spaced about 40 km apart and was last updated in 2022. This method is unable to subtle 2–3 cm/yr deformation gradients typical in Mandalay areas. Although time-series InSAR (TS-InSAR) technology has been widely used in urban areas, systematic studies focusing on cities in Mandalay remain limited. Hence, there is a need for more comprehensive and up-to-date investigations in Mandalay city area. Expanding the use of InSAR technology could provide valuable insights into surface deformation across broader regions and improve our understanding of urban dynamics in Myanmar.

Time-series data provide valuable temporal and spatial information about surface deformation [25]. Time-series data mining techniques can extract different deformation patterns by analyzing the shape and variation in the data over time [26].

Empirical methods are widely used to classify deformation time series based on statistical criteria. For example, ref. [27] used a manual approach to identify deformation patterns. Ref. [28] proposed an automatic classification method for Permanent Scatterer (PS) InSAR time series using conditional statistical tests. In their research, six distinct types of ground deformation were predefined, and each time series was assigned to one of these categories. Ref. [25] improved this approach by adding a class for phase unwrapping errors and applied it to a large dataset.

Some studies have conducted periodic analysis by decomposing time-series signals to extract sub-patterns and trend components that drive deformation. This helps in identifying the underlying causes. For instance, ref. [29] used independent component analysis (ICA) to decompose time-series data and identified four main components. They also analyzed the spatial relationship between these components and observed deformation patterns.

Advances in machine learning (ML) have introduced new approaches for time-series deformation analysis. Supervised learning methods use models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM), and transformers to classify deformation patterns, but they require substantial prior knowledge about the area to perform well [30,31,32]. Therefore, unsupervised learning methods are more suitable for discovering unknown or hidden deformation patterns.

The core procedure centers on dimensionality reduction and clustering. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) exemplify linear and nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques, respectively. For the clustering phase, methods like K-Means and Hierarchical Density Based Spatial Clustering (HDBSCAN) are directly applied to recognize deformation patterns, with various combinations of these techniques being implemented to accomplish the task. Researchers in [33] used PCA to reduce data dimensionality and extract key features before applying K-Means to detect deformation patterns. Ref. [34] used UMAP for nonlinear dimensionality reduction and HDBSCAN for density-based clustering to automatically identify subsidence areas. They also used a Piecewise Linear Fit (PWLF) model to detect change points in deformation acceleration. Ref. [1] extended the use of PCA and K-Means to time-series data from three SAR datasets, successfully mapping ground deformation patterns in Kunming, China.

Beyond these, other techniques such as Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [35], Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) [36], hierarchical clustering [37] and partitioning clustering [38,39], though not originally designed for InSAR, have demonstrated significant practical value in identifying time-series deformation patterns [40,41].

However, the majority of the aforementioned methods rely on point-to-point Euclidean distance to measure sequence similarity. This metric becomes suboptimal when surface deformation exhibits spatiotemporal lag effects, as it fails to adequately capture the true similarity between sequences. The deformation patterns in InSAR time-series may exhibit a spatiotemporal lag due to variations in geographical conditions. In such scenarios, the overall trend and shape of the sequences are more critical. Consequently, time-series similarity measures based on data shape often exhibit superior performance [42,43,44].

The Dynamic Time Warping and time-based Longest Common Subsequence (DTLCS) method has shown promise in capturing shape-preserving similarity for time-series classification in non-geophysical domains. It is a deformation pattern characterization method based on the slope features of time series. It preserves the temporal trend information by discretizing the extracted time-series slopes and then computes the similarity between the transformed sequences using a constrained Longest Common Subsequence (LCS) approach [45]. However, its potential for unsupervised deformation regime identification in geodetic applications has not been explored. To bridge this gap, we propose DTLCS-AHC, a data mining framework that integrates DTLCS with Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) for the automated discovery of coherent deformation patterns from InSAR time series. Unlike traditional distance metrics that are sensitive to temporal misalignment and amplitude variation, DTLCS captures shape-based similarity by integrating dynamic time warping and longest common subsequence analysis, making it particularly suitable for nonlinear and heterogeneous InSAR sequences. While DTLCS was originally developed for supervised classification in non-geophysical domains [38], this study represents its first application to unsupervised deformation regime identification in large-scale urban subsidence monitoring. This shift enables automatic pattern discovery without requiring labeled training samples, thereby expanding its applicability to data-driven geodetic analysis.

Therefore, this study proposes an analytical framework based on DTLCS for InSAR time series data mining—referred to as DTLCS-AHC [45]. The primary innovation of this work lies in the novel cross-domain application of the DTLCS similarity measurement method to InSAR deformation time series modeling. By adapting and integrating existing DTW and LCS techniques, the framework effectively addresses the challenge of capturing spatiotemporal lag effects in ground deformation. Specifically, we introduce DTLCS to characterize temporal similarity between InSAR displacement series and combine it with AHC to identify spatially coherent deformation patterns in urban areas. The main contributions of this work are:

- Applying SBAS-InSAR technology to derive high-resolution surface deformation distributions for the urban area of Mandalay, Myanmar, using Sentinel-1 data from 2022 to 2025.

- Introducing DTLCS as a similarity measure for InSAR time series clustering for the first time: DTLCS can simultaneously capture the similarity in morphology and temporal phase of displacement time series, enabling more robust pattern recognition compared to traditional distance metrics (such as Euclidean distance or Pearson correlation coefficient). The distance matrix constructed based on DTLCS is subsequently used for AHC.

- Conducting a comprehensive analysis of the spatial distribution and temporal evolution characteristics of clustering results by integrating human activity factors and conceptual models based on geological and groundwater conditions to reveal the potential driving mechanisms of land subsidence.

By transferring existing sequence similarity methods to geodetic time series analysis, this study demonstrates how interdisciplinary technology integration can effectively enhance unsupervised pattern discovery in urban geological hazard monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Mandalay, located in central Myanmar, belong to Mandalay State, at a latitude of 21°58′30″N and a longitude of 96°5′0″E. The city lies within the central plain, and is high in the east, low in the west, with an average elevation of 579.1 m. To the north of the city rises Mandalay Hill, while the Shan Hills flank its eastern side. The Ayeyarwady River flows along its western boundary, adjacent to the Sagaing Hills [46,47]. The exposed strata consist primarily of Quaternary (Q) deposits, predominantly alluvial and fluvio-diluvial in origin. These deposits are composed mainly of silt, sandy gravels, and cohesive soils, exhibiting a loose to semi-consolidated structure with considerable variation in thickness.

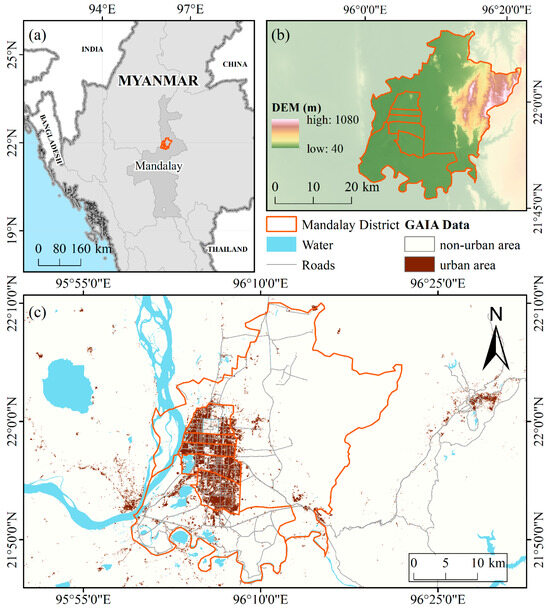

As Myanmar’s second-largest city, Mandalay serves as a vital economic, cultural, and transportation hub in the country’s Central Dry Zone [48]. According to the 2014 national census, it had a population of approximately 1.7 million, making it one of the most densely populated urban centers in Myanmar [49]. In terms of administrative division, the Mandalay region comprises seven townships: Aungmyetharzan, Chanayetharzan, Mahaaungmye, Chanmyatharzi, Pyigyidagun, Amarapura and Patheingyi. The district exhibits a concentrated pattern of building distribution, as illustrated in the map depicting the urban area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the study area: (a) Geographic location; (b) Digital elevation model (DEM); (c) Global Artificial Impervious Area (GAIA) land cover data.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Built-Up Area Data

Using 30 m resolution GAIA data [50], we created a Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) map to smooth out the land use variations within cities. This helped highlight the spatial continuity between urban core areas and their peripheries. Based on trial-and-error experiments with various density thresholds, considering both the integrity of urban forms and actual spatial distribution, an optimal threshold of 100 was chosen for defining urban boundaries. To avoid interference from small, isolated patches during boundary extraction, patches smaller than 1 square kilometer were removed, improving the accuracy and reasonableness of the boundary delineation [51].

Global Artificial Impervious Area (GAIA) data are a high-precision global dataset built from multiple sources of remote sensing data. It aims to monitor urbanization and human settlement expansion. GAIA integrates time-series Landsat images, nighttime light data (NTL), and Sentinel-1 SAR data, enhancing mapping accuracy in arid regions through adaptive NTL thresholds and SAR texture features. With a spatial resolution of 30 m and global coverage, this dataset provides valuable insights into urban development.

2.2.2. InSAR Data

Sentinel-1, part of the Copernicus Programme by the European Space Agency, is designed for global land and ocean ice monitoring. The Sentinel-1A satellite was launched in April 2014 and revisits the same area every 12 days. It operates in four data acquisition modes: Stripmap (SM), Interferometric Wide Swath (IW), Extra-Wide Swath (EW), and Wave (WV). This study utilizes data from the IW mode. The native resolution of IW SLC data is approximately 5 m in azimuth and 20 m in range; after multi-looking and geocoding, the effective spatial resolution of the derived deformation products is about 20–30 m.

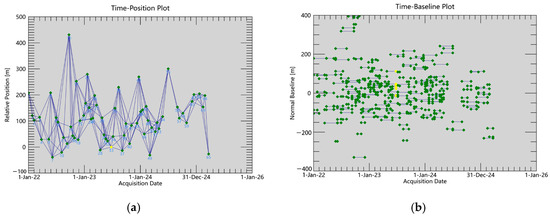

For our study, we selected orbit images from the Sentinel-1A satellite covering the period from 6 January 2022 to 22 March 2025, consisting of a total of 82 scenes. An image acquired on 25 June 2023, was chosen as the master image, with all other images coregistered and resampled accordingly.

Following the small baseline approach, we set spatial and temporal baseline thresholds to generate differential interferograms. To ensure effective connectivity among all SAR images, we set the maximum normal baseline to 120 m and the maximum temporal baseline to 60 days. The resulting time-position plot and time-baseline plot are shown in Figure 2, where green represents valid interferometric pairs. In the interferometric processing, the Minimum Cost Flow algorithm was selected as the phase unwrapping method, with the unwrapping decomposition level set to 1 and the coherence threshold for unwrapping set to 0.3. The coherence threshold of 0.3 was selected based on preliminary SBAS-InSAR tests using 2022–2024 Sentinel-1 data. While lower thresholds, like 0.2, reduced voids, they also introduced unreliable estimates over water bodies due to low temporal coherence. A threshold of 0.3 better preserves signals from urban infrastructure—our primary focus—while effectively excluding non-reflective or unstable surfaces. The Goldstein filter was applied for interferogram filtering to suppress phase noise while preserving fringe details. Atmospheric disturbances were corrected using Generic Atmospheric Correction Online Service (GACOS) [52,53,54]. Additionally, we reduced orbital phase errors by applying Precise Orbit Ephemerides (POD) and eliminated phase errors using SRTM DEM data. The Height Precision Threshold and Velocity Precision Threshold were set to 10 and 8, respectively, with the Product Temporal Coherence Threshold configured to 0.15. The unwrapped phase was then geocoded to the WGS84 coordinate system to generate the final deformation products [55,56,57].

Figure 2.

SBAS Connection Graph: (a) Time-Position plot; (b) Time-baseline plot.

The study focus on the temporal deformation characteristics of point targets. Additionally, Line-of-Sight (LOS) deformation analysis is sufficient for examining the spatial distribution of surface deformation. Hence, we focus on analyzing LOS deformation.

2.2.3. DEM Data

DEM data is from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), a project launched in 2000 by NASA and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA). The mission aimed to generate near-global digital elevation data for land surfaces. This product is derived from C-band radar interferometry and provides about 30 m spatial resolution. Given that Sentinel-1A also operates in C-band, the use of a C-band-based DEM ensures consistency in radar signal interaction with terrain, avoiding potential biases associated with cross-band DEM/SAR combinations.

2.2.4. Global Precipitation Measurement Mission (GPM)

The Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission is an international network of satellites designed to provide new-generation observations of global rainfall and snowfall. As a successor to the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM), GPM uses a “core observatory” satellite equipped with advanced radar and radiometer systems to accurately measure precipitation from space. This core satellite also serves as a standard to harmonize precipitation data collected by a constellation of research and operational satellites. In this study, we use GPM Level 3 monthly precipitation data (IMERG Final Run) with a spatial resolution of 10 km and a time resolution of one month. This dataset allows us to monitor precipitation patterns effectively over large areas and extended periods. While precipitation in Southeast Asia can be highly variable at sub-monthly timescales, the rainfall pattern in the Mandalay region is strongly seasonal, with the vast majority of precipitation occurring during the monsoon months (July–November) and negligible rainfall in the dry season (December–June), as confirmed by long-term GPM observations. Therefore, a monthly temporal resolution is sufficient to capture the dominant hydrological signal influencing surface deformation processes.

2.2.5. Road Data

Road data were obtained from OpenStreetMap (OSM), which provides comprehensive road network information for Myanmar. The dataset includes various road types, categorized as follows: major roads (motorways, trunk roads, primary roads, secondary roads, and tertiary roads); minor roads (e.g., local streets and roads within residential areas); highway connectors; very small roads; and pedestrian paths unsuitable for motor vehicles. All coordinates are provided in WGS84 geographic coordinate system (EPSG:4326) using decimal degrees as units.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) InSAR

The SBAS-InSAR time-series analysis technique was proposed by Berardino in 2002. It selects interferometric pairs with short temporal and spatial baselines to reduce decorrelation caused by changes over time and large spatial separation [58,59,60]. Assuming that SAR images covering the same study area are acquired at different times (), a total of interferometric pairs can theoretically be formed. To ensure high-quality interferograms, short-baseline pairs are selected by applying thresholds on both temporal and spatial baselines, resulting in the formation of multiple interferometric subsets. In the data processing workflow, high-coherence pixels are first identified based on interferometric coherence to ensure data quality. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), multilooking is applied with a specific window size, at the cost of reduced spatial resolution. Following pixel selection, two-dimensional (2D) or three-dimensional (3D) phase unwrapping methods are applied to each independent interferogram to retrieve the absolute phase values. The deformation phase corresponding to the -th interferogram is denoted as , and the associated deformation rate can be derived accordingly:

This equation can be rewritten as:

For the generated interferometric pairs, the following system of equations can be formulated:

is an matrix with elements of ±1, where +1 corresponds to the master image and −1 to the slave image. High-coherence pixels within each subset are first solved using a least-squares approach. Subsequently, the solutions across different subsets are integrated via singular value decomposition (SVD) to obtain the minimum-norm solution under the least-squares adjustment criterion. This yields a high-precision deformation time series and velocity map for the study area. It is important to note, however, that the SVD-based solution across subsets provides only a mathematically optimal result; it may still exhibit discrepancies in physical interpretation due to potential inconsistencies between subsets.

This method has several advantages: first, it uses temporal and spatial filtering to separate atmospheric effects from ground deformation signals, improving the accuracy of deformation estimation; second, by combining multiple interferometric pairs, it enhances monitoring capability in areas with low coherence; third, it is well suited for monitoring large-scale, slow surface deformation, and has shown strong performance in urban subsidence studies due to its wide spatial coverage.

2.3.2. Similarity Measurement Based on DTLCS

- 1.

- Dynamic Time Warping Algorithm (DTW)

The core idea of the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) algorithm is to use dynamic programming to align time series by minimizing the cumulative distance after alignment, thereby finding the best match between two time-series. This method can handle time shifts between time series effectively. The steps for this method are as follow [61]:

Assume there are two sequences and . Construct a distance matrix between the sequences with dimensions , where the element represents the distance between and . The DTW algorithm matches a warped path . represents an element in sequence , represents an element in sequence . is a traversal of matrix , and the warped path must satisfy two constraints:

- Endpoint constraint: The starting point of the path and the endpoint .

- Continuity constraint: For all , it must satisfy and .

- 2.

- Longest Common Subsequence (LCS)

The Longest Common Subsequence (LCS) algorithm is designed to find the longest subsequence shared by two time-series, allowing for some elements to be unmatched or ignored. Unlike Euclidean distance or DTW, LCS does not require all points in the sequences to be matched. However, it enforces a one-to-one matching rule: each point in one sequence can only match one point in the other sequence.

For two sequences and of lengths and , using recursive formula to compute the length of the longest common subsequence, denoted as . The similarity between the two sequences is then defined as Equation (4) [62,63]:

where is the matching threshold that defines the maximum allowable difference between two values for them to be considered a match (i.e., two points are regarded as matched if their distance is less than or equal to ), and is the warping window threshold, typically set as a percentage of the sequence length, which limits the maximum time deviation allowed between corresponding points in the sequences. In this study, all time series are of equal length. Since the extent of sequence offset was unknown prior to the experiment, the parameter was set to the full sequence length. As for the parameter , after the subsequent trend transformation, all sequence values were discretized to −1, 0, or 1. Consequently, there is no tolerance range required for point-wise matching, and thus was set to 0.

where values ranges from 0 to 1. 1 indicates that the two sequences are identical within the given thresholds, while a value close to 0 indicates very low similarity. For sequences of equal length, the denominator becomes simply (or ), and the range remains [0, 1].

- 3.

- The trend-based LCS (TLCS)

The method addresses the limitations of traditional LCS in measuring time series similarity. The core idea is to focus on the direction of change rather than raw values. It converts the slope trends of the original time series—such as rising, falling, or stable—into symbolic representations. Similarity is then computed based on these symbol sequences. The detailed computation steps are as follows [45]:

- Given a sequence of length , the slope between consecutive points is calculated using Equation (6).

- The computed slopes are then discretized into a ternary symbol sequence , as defined by Equation (7). Each symbol represents the trend direction: increasing, decreasing, or stable.

- Finally, the LCS algorithm is applied to the transformed symbol sequences to compute their similarity.

This approach emphasizes the shape and trend of the time series, making it more robust to noise and amplitude variations.

- 4.

- Combined DTW and Trend-Based LCS (DTLCS)

The DTLCS (Dynamic Time Warping and Trend-based Longest Common Subsequence) method integrates the trend-based time series classification approach with DTW distance to create a new similarity measure. This combined metric preserves both point-to-point amplitude information and overall trend patterns [45]. The formulation is given in Equation (8):

where is the distance between the original sequences and calculated by a certain method. is a weighting parameter that balances the contribution of amplitude and trends. The behavior of the method varies with :

- When , the method reduces to pure trend-based LCS (TLCS).

- When , it becomes standard DTW.

- For , both amplitude and trend information are considered (mixed mode).

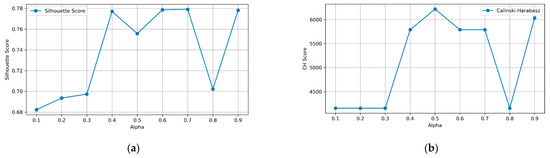

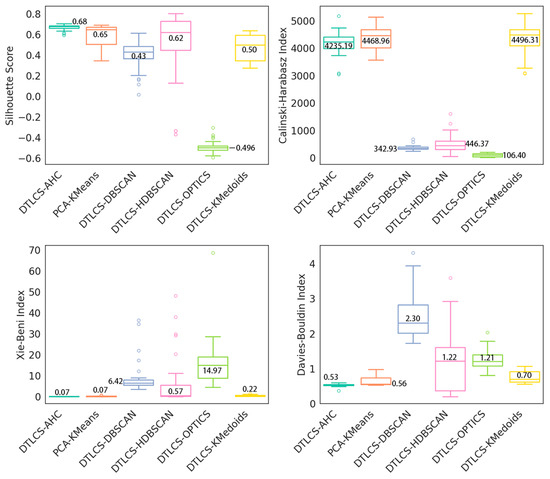

In practice, is recommended to be set to a small value to prevent the DTW component from dominating and drowning out the trend information. In this study, we employed the Silhouette Index and Calinski–Harabasz Index to evaluate parameter sensitivity, where higher values indicate better clustering performance. The results (Figure 3) show that a medium alpha value (between 0.4 and 0.7) yields superior outcomes. Considering both evaluation metrics, and to prevent DTW from dominating the similarity measure at excessively high alpha values, we ultimately set alpha to 0.5.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis of the α in the DTLCS distance metric: (a) Silhouette Index; (b) Calinski–Harabasz Index.

The choice of DTLCS is motivated by the nonlinear and temporally misaligned nature of InSAR deformation signals. In urban settings, neighboring areas often show similar subsidence trends, albeit with slight temporal lags caused by variations in soil properties or groundwater dynamics. Traditional Euclidean distance would treat such sequences as dissimilar, whereas DTLCS, by focusing on shape resemblance rather than point-to-point alignment, can effectively group them into the same deformation regime. Furthermore, DTLCS is robust to local noise and amplitude variations commonly observed in InSAR time series, enhancing the reliability of clustering results in real-world applications.

2.3.3. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC)

Hierarchical clustering is a commonly used unsupervised learning method for grouping or clustering samples in a dataset based on their similarity. Unlike other clustering methods, hierarchical clustering does not require specifying the number of clusters in advance. Instead, it builds a hierarchical structure by gradually merging or splitting samples, forming a clustering tree. There are two main types of hierarchical clustering: agglomerative and divisive.

Agglomerative hierarchical clustering is a bottom-up approach. Initially, each data point is treated as a separate cluster. In each step, the algorithm computes the distances between clusters, finds the two most similar clusters, and merges them into one. This process repeats, gradually forming a tree-like structure of clusters. The merging continues until all data points belong to a single cluster or a stopping condition is met. A key feature of this method is that it creates nested clusters with a strict containment relationship—any two clusters are either completely separate or one is contained within the other. The order in which clusters are merged is determined by the similarity between samples [64,65].

We use SSE, MSE, Xie-Beni Index, Silhouette Score, Calinski–Harabasz Index (CH Index), and Davies–Bouldin Index (DB Index) to assess the performance of clustering method we proposed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Evaluation of Clustering Effect Based on Indices.

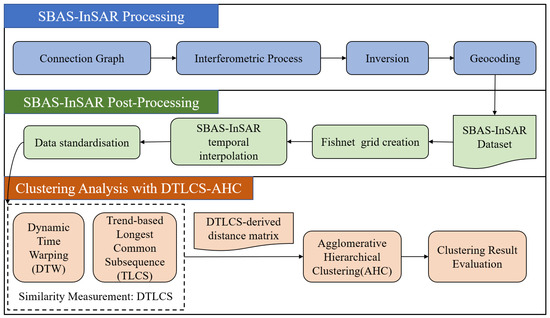

The overall processing workflow of the DTLCS-AHC framework proposed in this paper for clustering InSAR time-series deformation data is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the proposed DTLCS-AHC framework for InSAR time series clustering.

3. Results

3.1. InSAR Land-Subsidence Deformation Results

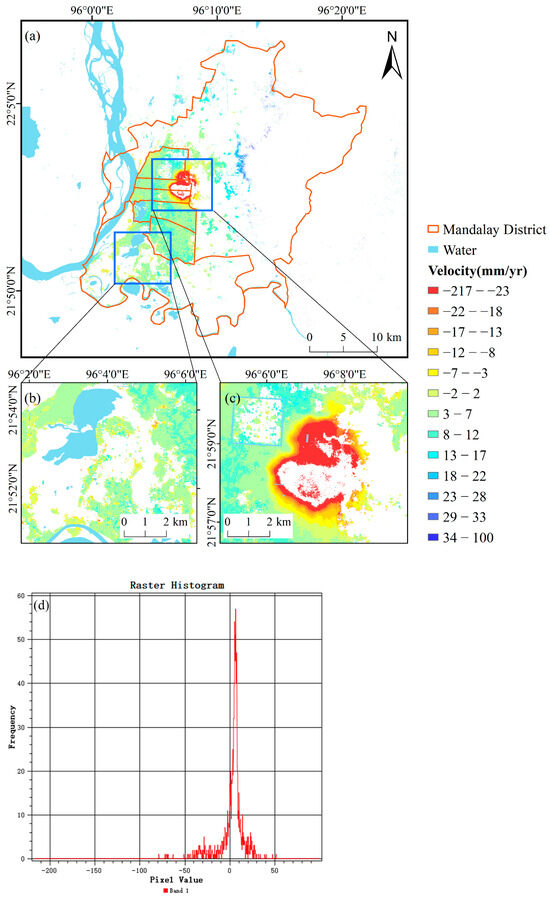

Figure 5 displays the distribution of surface deformation rates across the main urban areas of Mandalay City from January 2022 to March 2025, based on data from about 330,000 sample points obtained through SBAS-InSAR. The area shows a maximum difference in deformation rates of up to 119 mm/year, with the fastest subsidence and uplift rates being −217 mm/yr and 99 mm/yr, respectively. The map reveals that subsidence is mainly concentrated in the Mandalay district, especially in the eastern part, where it is most noticeable. An interesting observation is the ring-like pattern of this subsidence, mostly appearing around the outer edges of the monitored area.

Figure 5.

Deformation monitoring results: (a) deformation velocity results from SBAS-InSAR for Mandalay city; (b,c) present enlarged details of the key subsidence areas; (d) deformation velocity histogram.

The deformation rate histogram (Figure 5d) further illustrates the characteristics of surface deformation in Mandalay. There is a clear peak in the deformation rate near zero, indicating that most parts of the city are relatively stable or experiencing minor changes. However, there is a notable long-tail distribution in the negative values (indicating subsidence), which aligns with the significant subsidence observed in the eastern region.

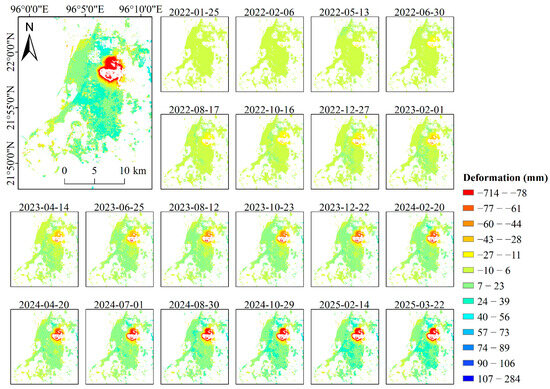

Looking at the cumulative deformation charts over different stages (Figure 6), we observe that the differences in surface deformation rates increased gradually throughout the monitoring period. This suggests that the trends and speeds of deformation vary across different areas. Starting from the 10th month of monitoring, the eastern region showed an increasingly evident trend of subsidence, becoming more pronounced over time. This created a clear boundary between areas experiencing subsidence and those that were relatively stable or uplifting. By the end of the monitoring period, the total accumulated subsidence reached −714 mm.

Figure 6.

Cumulative deformation of densely built areas in Mandalay city at different periods.

This analysis provides valuable insights into the ongoing changes in Mandalay’s urban landscape, highlighting areas requiring closer attention due to their higher rates of subsidence.

3.2. Accuracy Assessment of InSAR Monitoring Results

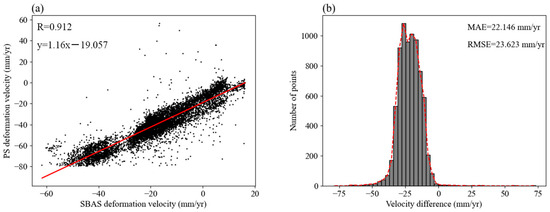

This research introduces a clustering approach that utilizes surface subsidence rates and time-series data obtained through InSAR technology. The accuracy of the InSAR monitoring results significantly influences the outcomes of the clustering analysis. The absence of contemporary leveling and GPS measurements makes it difficult to rigorously assess the accuracy of our monitoring data. Therefore, we employed cross-validation between PS-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR results to indirectly assess the internal accuracy of the monitoring data and determine the more suitable method for subsequent applications.

We processed Sentinel-1A images covering the period from January 2022 to October 2024 (Figure 7). By comparing the results of PS-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR, we found that in the heavily subsiding areas of Mandalay, among 7555 corresponding points, the deformation rates derived from different MT-InSAR methods showed a strong positive correlation (R = 0.912). This indicates that the MT-InSAR method provides high reliability and consistency for surface subsidence monitoring.

Figure 7.

Accuracy assessment results: (a) scatterplot of deformation velocity between PS-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR; (b) distribution of velocity difference, and the red dashed line represents the fitted curve of the velocity difference distribution.

However, the velocity measured by PS-InSAR was generally slightly higher than that of SBAS, with differences increasing as the rate of deformation increased. This bias can be attributed to several conceptual and methodological differences between the two approaches:

- Reference point stability: If the selected reference pixel has undetected motion, it introduces a constant bias across the entire displacement field. Differences in reference point selection between PS-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR can thus lead to an overall offset in the estimated velocities.

- Atmospheric phase screen (APS) estimation: PS-InSAR typically removes atmospheric artifacts using spatial high-pass filtering, while SBAS employs temporal-spatial decomposition (e.g., via singular value decomposition). Incomplete removal of stratified tropospheric delays may result in residual biases, particularly in regions with strong vertical atmospheric gradients.

- Scatterer type and density: PS-InSAR focuses on high-amplitude stable points (e.g., building corners, metallic fixtures), which in our study area—dominated by 2–3 story residential buildings—are often located on structurally vulnerable elements such as roof edges or weak foundations. These points are prone to localized, non-uniform subsidence and thus tend to exhibit higher deformation rates. In contrast, SBAS-InSAR incorporates both persistent and distributed scatterers and applies spatial averaging, which provides a more spatially continuous representation but may smooth out extreme deformation signals. This averaging effect is particularly evident in heterogeneous urban fabrics, where SBAS may underestimate peak subsidence rates due to the inclusion of more stable surrounding areas.

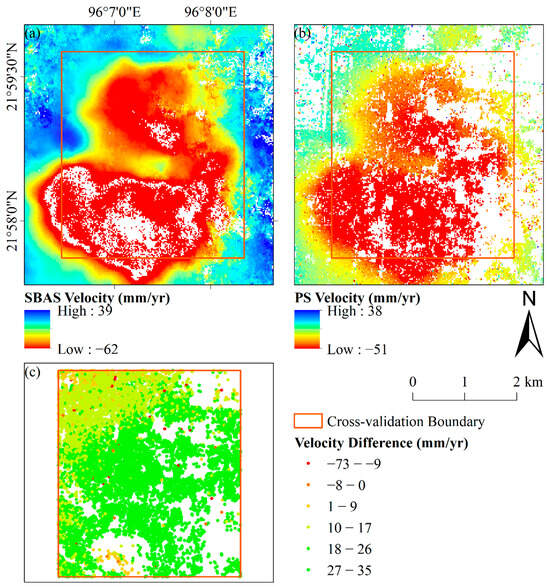

To further investigate the characteristics of the discrepancy between PS-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR, we generated both a comparative velocity map and a spatial distribution map of their differences over the cross-validation area (Figure 8). The validation site is underlain primarily by Quaternary alluvial deposits, with relatively homogeneous geological conditions and no significant faults or lithological contrasts. The difference map shows no pronounced spatial clustering of the bias. Although slightly larger discrepancies are observed in regions experiencing high subsidence rates (<−30 mm/yr), we attribute this deviation primarily to the conceptual and methodological differences between the two approaches, as discussed above.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of velocity differences in the cross-validation area: (a) SBAS-InSAR deformation velocity map over the validation region; (b) PS-InSAR deformation velocity map over the validation region; (c) spatial distribution of the velocity difference between SBAS and PS-InSAR results.

Despite this systematic bias, the high correlation in spatial patterns (R = 0.912) supports the robustness of the observed deformation signals. Furthermore, SBAS-InSAR demonstrates superior performance in reducing data gaps and improving spatial coverage, which is essential for continuous monitoring in heterogeneous urban environments [66].

After comprehensive consideration, this study ultimately selected the SBAS-InSAR method for future surface subsidence monitoring activities. This choice was made based on its superior performance in covering gaps and its overall suitability for our specific research needs.

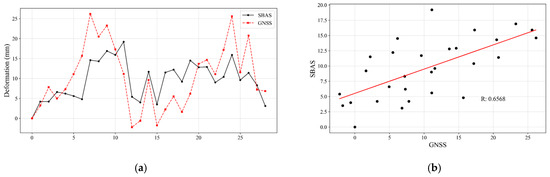

In addition, we further validated the SBAS-InSAR results using GNSS station data. Due to the absence of nearby GNSS stations within the study area, we selected a GNSS station located within the same Sentinel-1 scene for comparative analysis. However, the GNSS observations suffer from temporal gaps and are only available up to December 2020. To ensure temporal consistency, we collected 29 ascending Sentinel-1A images acquired between January 2019 and August 2020 and applied the SBAS-InSAR technique. The resulting deformation time series were then compared with the co-temporal GNSS measurements to evaluate the applicability and accuracy of SBAS-InSAR in this region. Figure 9 presents the comparison between the GNSS and SBAS-InSAR results. A moderate positive correlation (R = 0.6568) is observed between the two datasets, suggesting broad consistency in the long-term deformation pattern at the regional scale. Although the GNSS station lies outside the immediate study area and its representativeness may be limited, the overall consistency provides preliminary support for the reliability of the SBAS-derived displacements and indicates that MT-InSAR is capable of capturing large-scale surface deformation signals in this region.

Figure 9.

Accuracy assessment results with GNSS: (a) Comparison of deformation time series between SBAS-InSAR and GNSS; (b) Correlation between SBAS-InSAR and GNSS deformation measurements.

3.3. DTLCS Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering Results

3.3.1. TS-InSAR Post-Processing

Post-processing of InSAR data was performed to prepare the dataset for subsequent similarity measurement and clustering analysis.

First, spatial interpolation was applied. An adaptive gridding method was used to integrate the sparse measurement points (MPs) onto a uniform spatial grid, ensuring that each grid cell contained at least one MP. The process begins by generating a set of geometric polygons, each representing an individual grid cell, based on the spatial extent of the InSAR datasets. The optimal grid cell size is determined as follows: over the interval (in degrees), the total number of grid cells produced at each grid size n is evaluated. The optimal size corresponds to the smallest possible grid dimension—thereby preserving higher spatial resolution through a larger number of cells ()—while still being large enough to contain at least one monitoring point (MP). This optimal size is identified by plotting against the range of n values and locating the point of maximum curvature using the Kneed algorithm. Grid cells that remain empty due to missing data from either geometry are automatically removed. This approach eliminates the subjectivity associated with manual grid-size selection and ensures that every retained grid cell contains deformation information from at least one MP. The optimal grid size was determined to be 0.002 degrees.

Next, temporal interpolation was conducted to fill gaps in the time series. Several mathematical models (linear, quadratic, and cubic) were tested to identify the best fit for each time series, aiming to minimize interpolation error while preserving the non-stationary characteristics of the original data. The performance of each model was evaluated using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Results showed that the linear interpolation method yielded the best average prediction accuracy. Therefore, linear interpolation was adopted to fill missing values, with a fixed time step of 12 days.

Additionally, to identify an appropriate number of clusters that accurately represent distinct deformation patterns, an iterative clustering procedure was performed. Starting with two clusters, the number of clusters was incrementally increased in each iteration. The optimal number was determined using a trial-and-error approach combined with the minimum non-zero inter-cluster distance. The iteration stopped when further increases in cluster number did not lead to a significant decrease in the minimum inter-cluster distance and no new distinct deformation trends emerged [67].

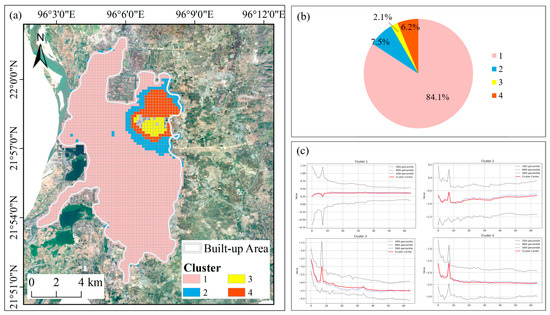

3.3.2. Clustering Result

Based on existing InSAR results, this study employs the DTLCS-AHC method to analyze time-series deformation patterns. By considering the similarity between time series (TS), DTLCS-AHC classifies the TS-InSAR dataset into four distinct cluster types:

- Cluster 1: Stable Upward

This cluster accounts for approximately 84.1% of the monitored points in the study area, making it the most widespread and dominant deformation pattern. The time series shows a slow and steady upward trend with small amplitude changes, indicating overall stability, with an average annual deformation rate of about 10 mm/yr. These areas are mainly located in the urban periphery and non-densely built-up zones. The uplift may be related to regional crustal rebound, tectonic uplift, or soil expansion caused by gradual groundwater recharge, reflecting a relatively stable crustal environment in the city.

- Cluster 2: Stable Downward

This cluster represents about 7.5% of the points and is characterized by a long-term, uniform, and slight subsidence with a stable negative deformation rate. This type of deformation is commonly found in transitional zones at the urban edge, possibly due to natural soil consolidation or mild land subsidence caused by limited groundwater extraction.

- Cluster 3: Subsiding Primary

Accounting for 2.1%, this cluster shows a significant and continuous accelerating subsidence, with a clearly increasing negative deformation rate over time. It exhibits the most intense deformation among all subsidence types, and its deformation curve displays a clear nonlinear acceleration. This pattern may indicate a high risk of local ground collapse or fault activity.

- Cluster 4: Subsiding Secondary

This cluster makes up 6.2% and also shows continuous subsidence, but at a slower rate compared to Cluster 3, representing moderate subsidence. Notably, Clusters 3 and 4 share some similarity in their overall time-series patterns—for example, both show periods of accelerated deformation. However, Cluster 3 stands out in terms of trend intensity and magnitude, suggesting a higher risk of structural instability.

In terms of spatial distribution, Clusters 2, 3, and 4 are not randomly scattered but are concentrated in the northeastern part of Mandalay City, forming a “ring-shaped” or “semi-ring-shaped” pattern around the stable and uplifting areas. This spatial configuration may suggest the presence of local geological weak zones, buried fault activity, or uneven loading due to urban development. Further analysis will be conducted in the following sections.

The cluster centroids and typical time-series deformation patterns for each TS-InSAR cluster are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Clustering results based on DTLCS-AHC: (a) spatial distribution of clusters; (b) percentage distribution of clusters; (c) deformation rate profiles of cluster centroids. In panel (c), the red line represents the cluster centroid, the blue line indicates the cluster mean, and the gray dashed lines denote the 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively.

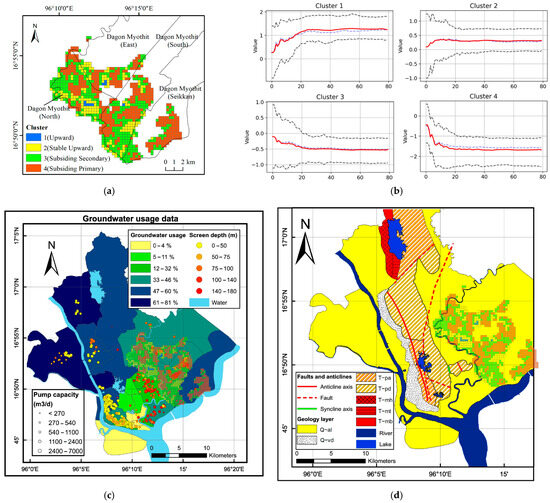

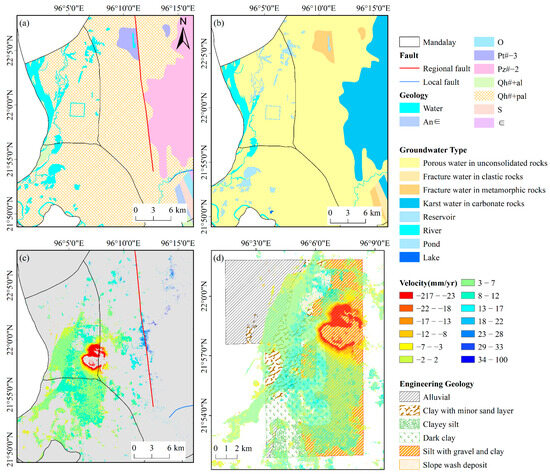

3.3.3. Comparison of Clustering Result with Yangon

The spatial distribution of the derived clusters is compared with regional anthropogenic activities and geological conditions. It should be noted that the unsupervised clustering method used aims to reveal hidden deformation patterns in InSAR time series. Areas that do not exhibit significant deformation cannot be regarded as reliable ground truth references [33].

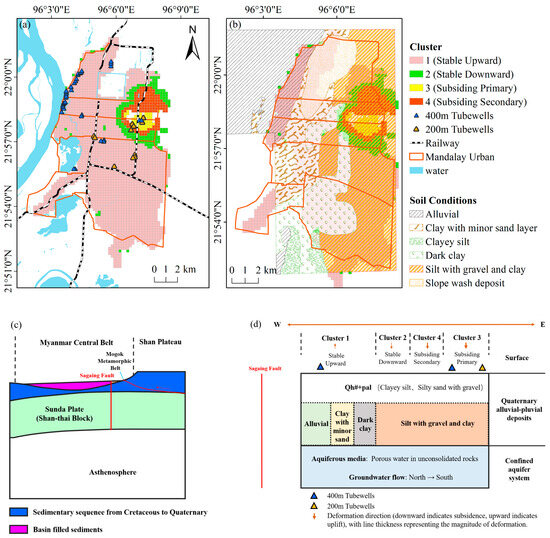

The urban area within Mandalay district (the six townships in Figure 11a) can be further subdivided into Mandalay sub-district and Amarapura sub-district (source by MIMU).

Clusters 2–4 all exhibit subsidence trends of varying degrees, and their spatial distribution aligns closely with administrative boundaries and engineering geological zones. These clusters are predominantly concentrated within the Mandalay Urban area, often in stratigraphic units characterized by silt with gravel and clay. Cluster 3 (subsiding primary) contains two 400 m deep wells and two 200 m deep wells [23], indicating high water demand in this area. Although the water supply capacity is insufficient for 24 h operation—with supply typically limited to 6–8 h—the groundwater extraction volume in Cluster 3 is higher than in other areas. This is likely the main reason for the observed accelerating subsidence pattern. In contrast, Cluster 4 (subsiding secondary) contains three 200 m deep wells, but the pumping intensity is presumably lower, which may explain why its subsidence rate is relatively moderate compared to Cluster 3. Furthermore, relevant research [68] indicates that between 2000 and 2020, urban expansion was concentrated in the eastern part of Mandalay District, further intensifying local resource pressure and surface loading.

To verify the generalizability and transferability of the proposed method, a comparative experiment was conducted in Yangon, another major city in Myanmar. Yangon was selected because, together with Mandalay, it ranks as the first and second largest city in Myanmar, with high population density and significant water resource demands—both facing risks of groundwater over-extraction [69]. The stratigraphic types in the Yangon area are diverse. For this comparative analysis, we selected areas with quaternary alluvial deposits (Q-al), as these share hydrogeological characteristics similar to the Qh#+pal formation in Mandalay and are similarly sensitive to groundwater extraction.

Using 80 Sentinel-1A ascending orbit images acquired between 2022 and 2025, surface deformation was inverted using the SBAS-InSAR method. Four typical deformation patterns were identified through DTLCS-AHC: upward, stable upward, subsiding secondary, and subsiding primary. The results show that in Yangon, the primary and secondary subsidence areas are also predominantly distributed in regions with high water consumption, dense tube wells, and greater well depths—exhibiting a high degree of consistency with the spatial distribution characteristics observed in Mandalay (Figure 12). This confirms that the proposed method can effectively identify linear subsidence patterns driven by human activities.

Figure 11.

Clustering results: (a) distribution of clustering results in relation to railways and tube wells (tube well data sourced from [23]); (b) spatial correspondence between clustering results and engineering geology (engineering geology map from [70]); (c) geological cross-section modified from [47]; (d) conceptual geological model of the clustering profile, synthesized from multiple sources (tube wells: [23]; stratigraphy: China–Laos–Myanmar–Bangladesh Joint Laboratory; engineering geology: [70]; groundwater flow: [71]).

Figure 12.

Comparison of clustering result with Yangon: (a) distribution of clustering results in the Yangon region; (b) deformation rate profiles of cluster centroids. In panel (b), the red line represents the cluster centroid, the blue line indicates the cluster mean, and the gray dashed lines denote the 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively; (c) overlay of clustering results and ground water usage; (d) overlay of clustering results and geological dat. Both overlay maps (c,d) are sourced from [69].

3.3.4. Analysis of Temporal Deformation Patterns Using EMD and DFT

To understand the underlying motion components driving the time-series deformation patterns, we selected typical monitoring points from the cluster centroid cells of different clusters for decomposition. The time series of these points were analyzed using Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) [72]. This allowed us to break down the time series into trend components, seasonal components, and other periodic components. The residual obtained from EMD can reveal long-term trends in ground movement (such as stability, subsidence, or uplift), while DFT helps identify periodic components, aiding in the recognition of annual cycles and other seasonal movements.

Table 2 lists the dominant frequencies, correlation coefficients, variance contribution rates, and FFT periods for each Intrinsic Mode Function (IMF) component. Notably, Cluster 1 exhibits a semi-annual periodic component (IMF2, FFT Period = 198 days), suggesting significant semi-annual movement in this area. Cluster 2 shows a roughly four-month periodic component (IMF2, FFT Period = 132 days), which may be linked to specific seasonal factors.

Table 2.

Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), periods, correlation coefficients, and variance contribution rates of the clusters.

Although longer-period components are present in both Cluster 1 and Cluster 2, their dominant frequencies are zero, leading us to interpret these as very long-term trend components rather than clear seasonal components. For Clusters 3 and 4, the seasonal components are not prominent, with the deformation patterns being mainly driven by the residual terms.

In summary, the analysis provides insights into the underlying mechanisms driving deformation in different areas. Specifically:

- Cluster 1: Shows a semi-annual cycle (IMF2, FFT Period = 198 days), indicating significant semi-annual movement.

- Cluster 2: Exhibits a roughly four-month cycle (IMF2, FFT Period = 132 days), potentially related to seasonal factors.

- Clusters 3 and 4: Have less pronounced seasonal components, with deformation primarily influenced by residual terms.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Advantages and Disadvantages of DTLCS-AHC Methods

Based on the work of [33], we conducts a clustering analysis of urban surface deformation patterns. To ensure consistency and comparability in data processing, we adopted the same time-series data post-processing workflow as used in their study, which significantly improved processing efficiency. However, a key difference lies in the clustering approach: while Alessandro et al. used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) combined with K-means clustering, we employed a DTLCS-AHC method for classifying deformation patterns.

Mandalay City covers a large area, but much of the eastern part consists of mountainous terrain. The actual urban area is relatively concentrated and limited in extent. PCA is a linear decomposition technique and is less sensitive to nonlinear deformation patterns. When using traditional PCA and K-means methods, the deformation patterns could only be roughly divided into two classes. Important local deformation features were either overlooked or merged, leading to a loss of detailed pattern information.

In contrast, the DTLCS similarity measure used in this study effectively preserves the shape and trend information of time series. By inputting the distance matrix computed using DTLCS into the AHC algorithm, we achieved a more detailed and accurate classification of deformation patterns.

Furthermore, we evaluated the clustering performance using multiple metrics, including the Silhouette Score, Calinski–Harabasz Index, and Davies–Bouldin Index. As shown in Table 3, the evaluation results for different clustering methods are presented. This notation helps highlight the best-performing method for each evaluation metric.

Table 3.

Results of evaluation for the different clustering methods. The up and down arrows indicate the optimal values for each metric. Specifically, a downward arrow (↓) indicates that a lower value is preferred, while an upward arrow (↑) indicates that a higher value is preferred. Underlined entries denote the best performance per metric.

When comparing DTLCS-AHC with other commonly used clustering algorithms, our method demonstrates clear advantages across various evaluation criteria, confirming its superior performance in capturing the complex deformation patterns in the study area.

In addition, we performed 30 bootstrap experiments, each time sampling 70% of the data with replacement for clustering analysis. Performance was evaluated using multiple metrics, and statistical significance was assessed via the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The results (Figure 13) show that DTLCS-AHC achieved superior performance in terms of the Silhouette Score (Sil), XB Index (XB), and Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI), with median values of 0.661, 0.081, and 0.538, respectively—significantly higher (p < 0.01) than all other methods. Although DTLS-KMedoids obtained a slightly higher Calinski–Harabasz (CH) index, DTLCS-AHC demonstrated the best overall clustering performance and stability across all four metrics.

Figure 13.

Boxplot comparison of clustering performance on Silhouette, Calinski–Harabasz, Xie–Beni, and Davies–Bouldin indices. The median values are explicitly labeled.

The improved performance of DTLCS-AHC is primarily attributed to its shape-preserving similarity measurement. Unlike PCA-KMeans, which relies on linear dimensionality reduction and Euclidean distance, DTLCS captures temporal evolution patterns through dynamic time warping and longest common subsequence analysis—metrics that are robust to phase shifts and local noise common in InSAR time series. As a result, pixels exhibiting similar deformation trends but with slight timing delays (e.g., due to heterogeneous subsurface conditions) can still be grouped together, leading to more physically coherent clusters. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying spatially contiguous deformation zones such as subsidence bowls or fault-related strain accumulation areas.

The DTLCS-AHC method also has several limitations:

First, the method involves computing a distance matrix and performing hierarchical clustering, which results in relatively high computational complexity. For large datasets or those with fine spatial resolution, both computation time and memory usage can increase significantly. For example, in large areas like Mandalay City, processing a greater number of sample points or longer time series may reduce the computational efficiency of the DTLCS-AHC method.

Second, the performance of DTLCS-AHC depends heavily on parameter selection, such as the distance threshold and the weight parameter () that balances the contributions of DTW and LCS in similarity measurement. Different parameter settings may lead to different clustering results. Although this study used multiple clustering evaluation metrics to assess performance, determining optimal parameters in new study areas remains a challenge.

Therefore, future research should focus on improving the computational efficiency and adaptability of the DTLCS-AHC method. Potential directions include optimizing algorithms for faster distance matrix computation, exploring parallel processing techniques, and developing automated parameter selection strategies to enhance the method’s scalability and robustness across diverse geographic and environmental conditions.

4.2. Spatiotemporal Variability of Pre-Earthquake Surface Deformation

A magnitude 7.7 earthquake struck Mandalay Region, Myanmar, on 28 March 2025. The seismogenic mechanism of this earthquake is essentially a dextral strike-slip strain release process dominated by the Sagaing Fault, occurring within the tectonic context of the oblique subduction of the Indian Plate [47]. The long-term slip rate of this fault is approximately 16–24 mm/yr [73]. However, due to the predominantly near-north–south direction of fault motion and the relatively low sensitivity of InSAR technology to surface deformation in this direction [74], no significant pre-seismic deformation along the fault was detected [47].

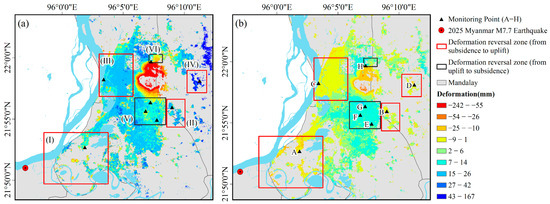

Interestingly, InSAR time-series analysis revealed a spatially heterogeneous pattern of surface deformation in the study area over several years prior to the earthquake.

By comparing cumulative displacements over two periods, a long-term phase (1 January 2022 to 11 September 2024) and a recent phase (11 September 2024 to 22 March 2025), we identified deformation trend reversals in multiple areas. Four regions (I, II, III, IV) exhibited uplift during the long-term phase but transitioned to subsidence in the recent phase, indicating a clear reversal of deformation trends. In contrast, two regions (V, VI) showed no significant trend in the long-term phase but began to uplift during the recent phase (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Comparison of surface deformation characteristics during the long-term and recent phase: (a) Cumulative displacement during the long-term phase (1 January 2022–11 September 2024); (b) Cumulative displacement during the near-term phase (11 September 2024–22 March 2025).

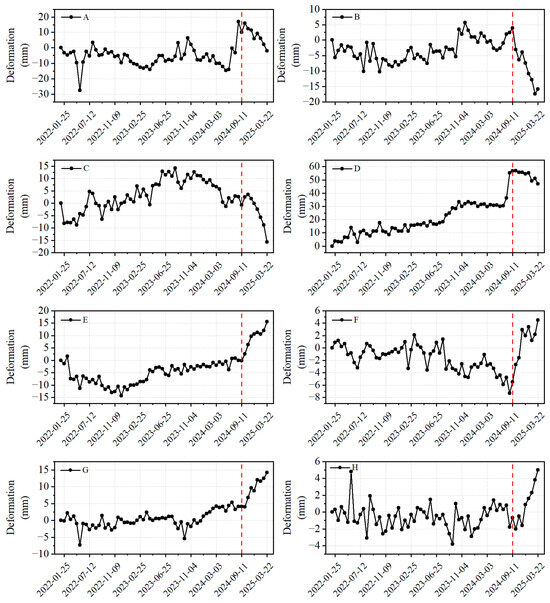

Eight representative monitoring points were selected from the six regions, corresponding to points A–H in Figure 14. Further analysis of their time-series displacement curves revealed diverse deformation patterns (Figure 15):

- Points A–D (located in pre-seismic subsidence areas): points A and B showed brief uplift before the recent phase, followed by continuous subsidence; Point C transitioned from stability to subsidence; Point D experienced slow uplift during the long-term phase, followed by a strong uplift event, and then transitioned to subsidence.

- Points E–H: exhibited minor fluctuations during the long-term phase but clear uplift in the recent phase.

Figure 15.

Time series of representative points (A–H) within the deformation reversal zone. The red dashed line indicates the time point seven months prior to the earthquake.

Overall, approximately seven months before the mainshock, the surface deformation rates accelerated in multiple regions, accompanied by systematic changes in deformation trends.

Notably, these changes began about 6–8 months before the mainshock, showing a temporal similarity to pre-seismic deformation patterns observed in other major earthquakes, such as the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake in Italy [75].

However, due to the lack of independent geophysical or hydrological observational constraints, we do not interpret these changes as definitive pre-seismic signals. Instead, we regard them as anomalous phenomena worthy of further attention and suggest that future studies may combine multi-source monitoring and numerical modeling for in-depth investigation.

4.3. Likely Explanations of Deformation

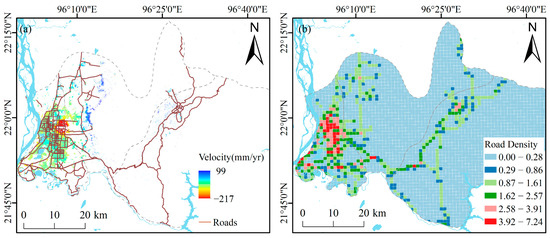

4.3.1. Road Density

To investigate the relationship between land subsidence and road networks, road density was calculated for Mandalay City using a grid size of 1 km × 1 km. Road density is defined as the total length of roads within each grid divided by the grid area.

Road network density reflects the stage of urban development to some extent. Areas with higher road density are typically more developed and have fewer ongoing construction activities. In contrast, areas with lower road density are often newly developing or planned expansion zones, where extensive civil engineering projects may be underway—activities that can contribute to land subsidence [76].

Using the natural breaks (Jenks) classification method, the road density grid was divided into six levels. The spatial distribution of road networks in Mandalay shows significant imbalance: high-density areas are mainly concentrated in the western and central parts of the city (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Impact of road density on subsidence: (a) road distribution in Mandalay city; (b) road network density.

Notably, our results found that land subsidence is particularly pronounced at the boundaries where road density transitions from high to low. This pattern is likely closely related to construction activities. Specifically, during urban expansion from highly developed city centers to outer areas, the interface between established and newly developed zones often experiences intensive engineering work. Such concentrated human activity may accelerate localized ground subsidence.

4.3.2. Rainfall

The climate of Mandalay is predominantly characterized by a tropical wet and dry climate. Situated in Myanmar, Mandalay experiences distinct tropical weather conditions, marked by a pronounced dry season. The rainy season spans from May to October, while the dry season lasts from November to April, exhibiting clear cyclical variations.

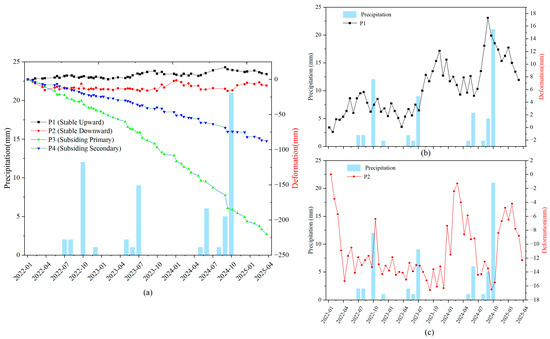

Analysis of GPM (Global Precipitation Measurement) data reveals a significant seasonal pattern of precipitation within the study area, with most rainfall occurring between May and October. To investigate the impact of precipitation on surface deformation, we utilized monthly GPM precipitation data alongside empirical mode decomposition (EMD) of time series centered around cluster centroids. Results indicated that only time series within the areas covered by Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 exhibited pronounced periodic variations. Overlay analysis of monthly precipitation and deformation measurements confirmed these findings, showing fluctuations specifically within the ranges of these two clusters, aligning with the EMD results.

Our study found that monthly rainfall within the range of 12 to 25 mm tends to induce more noticeable ground subsidence. Among randomly selected time series points from different cluster regions (as shown in Figure 17), monitoring points in Clusters 3 and 4 displayed linear subsidence, whereas those in Clusters 1 and 2 showed nonlinear subsidence patterns, correlating with the cyclical changes in rainfall. Higher rainfall amounts resulted in prolonged periods of ground subsidence, while subsidence caused by monthly rainfall less than 10 mm exhibited a lag effect.

Figure 17.

Analysis of the relationship between rainfall and surface deformation: (a) deformation of monitoring points P1 (Stable Upward), P2 (Stable Downward), P3 (Subsiding Primary), and P4 (Subsiding Secondary) and changes in monthly rainfall; (b) P1 and rainfall; (c) P2 and rainfall.

In summary, the relationship between precipitation and surface deformation in Mandalay demonstrates that higher rainfall intensities lead to longer durations of subsidence, with notable impacts observed particularly within specific clusters [77].

4.3.3. Geology and Ground Water

Analysis of land deformation rates in the study area reveals that both severe and minor subsidence zones are distributed within the same stratigraphic unit—Qh#+pal (Holocene alluvial–proluvial and lacustrine deposits). This suggests that lithology may not be the primary factor controlling the spatial variation in subsidence. Instead, the degree of settlement is likely influenced more by local conditions such as groundwater extraction intensity, soil structure, and aquifer response.

The study area is widely covered by Quaternary Holocene alluvial–proluvial deposits (Qh#+pal), which are composed mainly of muddy soil and fine-grained soils containing gravel. These strata are characterized by loose structure and high compressibility, making them prone to primary consolidation settlement under conditions of groundwater over-extraction. Specifically, the groundwater in this area is predominantly pore water within unconsolidated or weakly consolidated Quaternary sediments such as sand, silt, and clay. Such aquifer systems are typically shallow, with short recharge cycles, strong heterogeneity, and high accessibility for extraction. These same characteristics also make them highly sensitive to anthropogenic pumping. Long-term excessive extraction can easily lead to irreversible land subsidence.

Comparison with the engineering geological map (Figure 18d) shows that areas with severe subsidence are mostly distributed within zones classified as “silt with gravel and clay.” This soil assemblage is characterized by a certain gravel content that enhances the skeletal support of the soil matrix, combined with abundant silt and clay components that contribute to high plasticity and adsorption capacity. However, when these soils become fully saturated, their shear strength can decrease significantly, leading to an increased risk of subsidence.

Figure 18.

Relationship between subsidence and geology: (a) geology; (b) groundwater type distribution; (c) surface deformation rates; (d) comparison with engineering geology (based on a map digitized from [70]).

In terms of water demand, the study area is located in the central dry zone of Myanmar, where precipitation is highly seasonal and surface water resources are limited, leading to a high dependency on groundwater among the local population. According to available data, the public water supply system in Mandalay City covers only about 55% of the population, with an average daily supply duration of just 10 h. The remaining residents rely heavily on private shallow wells for domestic water. Furthermore, the urban water distribution network is aging, with a reported leakage rate as high as 52% [24], which not only exacerbates water shortages but also indirectly encourages unregulated groundwater extraction. Such uncontrolled extraction is likely one of the key anthropogenic factors triggering and accelerating land subsidence in the region.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an integrated SBAS-InSAR and DTLCS-AHC framework to investigate urban land subsidence in Mandalay, Myanmar, from January 2022 to March 2025. The main findings are summarized as follows:

Land subsidence in Mandalay is highly heterogeneous, with the most severe deformation occurring in the eastern part of Mandalay Township, reaching rates up to −217 mm/yr and cumulative displacement of −714 mm over three years.

Four distinct deformation regimes were identified: stable (upward/downward), primary subsidence, and secondary subsidence. The spatial distribution of rapidly subsiding clusters aligns with expanding urban zones, highlighting the role of anthropogenic activity.

Spectral and trend analysis reveals that stable areas exhibit seasonal oscillations (dominant periods: 4–6 months), whereas severely subsiding regions are dominated by non-seasonal, linear trends, indicating irreversible ground compaction.

Deformation patterns correlate strongly with environmental and human factors:

- Subsidence intensifies at urban transition zones with moderate road density;

- Rainfall events (>12 mm/month) trigger accelerated sinking in vulnerable areas;

- Pre-seismic anomalies—including trend reversals up to 7 months before the Mw 7.7 earthquake—suggest potential crustal precursors.

The DTLCS-AHC framework proves effective in extracting shape-based deformation patterns without labeled data, offering a scalable approach for urban subsidence monitoring. These results enhance understanding of the multi-driver nature of ground deformation in rapidly urbanizing cities and support future risk assessment and sustainable planning.

For future work, we have two promising avenues. First, we suggest focusing on the worst-subsiding areas (where land sinks more than 30 mm/yr). To work with local agencies to do two key things: drill shallow holes to check for soft, compressible soil layers, and monitor groundwater levels. This fieldwork will provide direct evidence to see if the sinking is caused by groundwater pumping. Combining this on-site data with satellite maps will make our understanding of the sinking process much stronger and help us predict future subsidence more accurately, especially in places like Myanmar where data is scarce. Second, the DTLCS-AHC framework demonstrates considerable potential for international application, particularly in diverse geological settings such as inland cities and mining areas worldwide. Its core advantage lies in its independence from region-specific conditions, making it generically applicable to InSAR time-series scenarios characterized by complexity, nonlinearity, and asynchronous evolution. For instance, in inland cities facing severe groundwater over-extraction, such as those in the North China Plain, land subsidence often manifests as a combination of seasonal fluctuations superimposed on long-term trends. Similarly, surface deformation in mining areas may exhibit abrupt collapse or phased rebound. Time-series data from these regions commonly present challenges including temporal offset and localized similarity [74]. By integrating DTW for elastic temporal alignment with LCS analysis for state recognition, the proposed framework provides a robust and adaptable tool for analyzing such human activity-induced deformation across a wide range of geographic and environmental contexts, thereby enhancing its international applicability and practical utility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Q.; methodology, J.Q.; software, J.Q.; validation, J.Q.; formal analysis, J.Q.; investigation, J.Q.; resources, J.Q.; data curation, J.Q., C.L., X.W. and T.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Q.; writing—review and editing, J.Q., D.Z. and Z.Z.; visualization, J.Q. and M.Y.; supervision, J.Q.; project administration, J.Q.; funding acquisition, J.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Yunnan International Joint Laboratory of China-Laos-Bangladesh-Myanmar Natural Resources Remote Sensing Monitoring, grant No. 202303AP140015.

Data Availability Statement

The Sentinel-1 A data can be downloaded at: ASF (https://search.asf.alaska.edu/) (accessed on 1 April 2025), DEM (https://dwtkns.com/srtm30m/) (accessed on 1 April 2025), GPM (https://gpm.nasa.gov/data/directory) (accessed on 1 April 2025), GAIA data (http://data.ess.tsinghua.edu.cn) (accessed on 1 April 2025), Road Data (https://download.geofabrik.de/asia/myanmar.html#) (accessed on 1 April 2025), Myanmar District Boundaries and Railway data (https://geonode.themimu.info/layers/?limit=100&offset=0) (accessed on 1 April 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the authors of [33] for openly sharing their implementation, which helped us with InSAR data post-processing and clustering analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, M.; Li, M.; Huang, C.; Zhang, R.; Liu, R. Exploring the InSAR Deformation Series Using Unsupervised Learning in a Built Environment. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Z.R.; Hu, X.M.; Tao, S.L.; Hu, X.; Wang, G.Q.; Li, M.J.; Wang, F.; Hu, L.T.; Liang, X.Y.; Xiao, J.F.; et al. A national-scale assessment of land subsidence in China’s major cities. Science 2024, 384, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, A.H.M.; Liu, Z.Y.; Du, Z.Y.; Huang, H.W.; Wang, H.; Ge, L.L. A novel framework for combining polarimetric Sentinel-1 InSAR time series in subsidence monitoring—A case study of Sydney. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Zhu, L.; Dai, Z.X.; Gong, H.L.; Guo, T.; Guo, G.X.; Wang, J.B.; Teatini, P. Spatiotemporal modeling of land subsidence using a geographically weighted deep learning method based on PS-InSAR. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramondo, S.; Bozzano, F.; Marra, F.; Wegmuller, U.; Cinti, F.R.; Moro, M.; Saroli, M. Subsidence induced by urbanisation in the city of Rome detected by advanced InSAR technique and geotechnical investigations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3160–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, F.; Osmanoglu, B.; Cabral-Cano, E.; Dixon, T.H.; Alejandro Avila-Olivera, J.; Hugo Garduno-Monroy, V.; DeMets, C.; Wdowinski, S. Monitoring land subsidence and its induced geological hazard with Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry: A case study in Morelia, Mexico. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Luo, X.; Chen, Q.; Huang, D.; Ding, X. Detecting land subsidence in Shanghai by PS-networking SAR interferometry. Sensors 2008, 8, 4725–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aobpaet, A.; Cuenca, M.C.; Hooper, A.; Trisirisatayawong, I. InSAR time-series analysis of land subsidence in Bangkok, Thailand. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 2969–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh Ho Tong, M.; Le Van, T.; Thuy Le, T. Mapping Ground Subsidence Phenomena in Ho Chi Minh City through the Radar Interferometry Technique Using ALOS PALSAR Data. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 8543–8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, A.; Sreejith, K.M.; Rose, M.S.; Agrawal, R.; Sunil, P.S.; Sunda, S.; Chaudhary, B.S. Two decades of land subsidence in Kolkata, India revealed by InSAR and GPS measurements: Implications for groundwater management and seismic hazard assessment. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 2593–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S.; Xie, S.R. Accelerated Land Subsidence and Complex Temporal Variations in Newly Developed Areas in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Observed by InSAR. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 3001305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Emadodin, S.; Beitollahi, A.; Abdolazimi, H.; Ghods, B. Assessments of land subsidence in Tehran metropolitan, Iran, using Sentinel-1A InSAR. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Mann, D.; Freymueller, J.T.; Meyer, D.J. Synthetic aperture radar interferometry of Okmok volcano, Alaska: Radar observations. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 2000, 105, 10791–10806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- En, J.; Mingfei, W.; Xiang, Z. Deformation monitoring approach of Shanghai Yangtze River Bridge based on PSInSAR. Jiangsu Sci. Technol. Inf. 2022, 39, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, J.; Fang, L. Research Advances of Monitoring and Controlling Technology for Urban Land Subsidence. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2008, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chaussard, E.; Wdowinski, S.; Cabral-Cano, E.; Amelung, F. Land subsidence in central Mexico detected by ALOS InSAR time-series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 140, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.K.; Doubre, C.; Weber, C.; Gourmelen, N.; Masson, F. Recent land subsidence caused by the rapid urban development in the Hanoi region (Vietnam) using ALOS InSAR data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.C.; Samsonov, S.; Yin, H.W.; Ye, S.J.; Cao, Y.R. Time-series analysis of subsidence associated with rapid urbanization in Shanghai, China measured with SBAS InSAR method. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.H.; Zhao, C.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, Z.; Pepe, A. Long-Term Continuously Updated Deformation Time Series From Multisensor InSAR in Xi’an, China From 2007 to 2021. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 7297–7309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.Y.; Dai, K.; Xing, C.Q.; Li, Z.H.; Tomás, R.; Clark, B.; Shi, X.L.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R.; Qiu, Q.; et al. Land subsidence in Beijing and its relationship with geological faults revealed by Sentinel-1 InSAR observations. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 82, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.C.; Pei, X.J.; Wang, S.Y.; Huang, R.Q.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Z.L. Model test study on the hydrological mechanisms and early warning thresholds for loess fill slope failure induced by rainfall. Eng. Geol. 2019, 258, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Wang, C.; Qin, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, Q. Time-Series Analysis on Persistent Scatter-Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (PS-InSAR) Derived Displacements of the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Bridge (HZMB) from Sentinel-1A Observations. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalay City Development Committee for the Asian Development Bank. Mandalay Urban Services Improvement Project: Initial Environmental Examination. 2015. Available online: https://www.adb.org/projects/47127-002/main (accessed on 16 October 2025).