Benchmarking Elevation Plus Land Surface Parameters Finds FathomDEM and Copernicus DEM Win as Best Global DEMs

Highlights

- Digital elevation models with one-arc-second are still the best free scale available globally. When compared to a lidar-derived reference digital terrain model, FathomDEM consistently performs best but has a restrictive license. The Copernicus DEM is the best free option, with the ALOS AW3D30 only in rugged and steep mountainous areas. We also evaluated FABDEM and GEDTM v1.2.

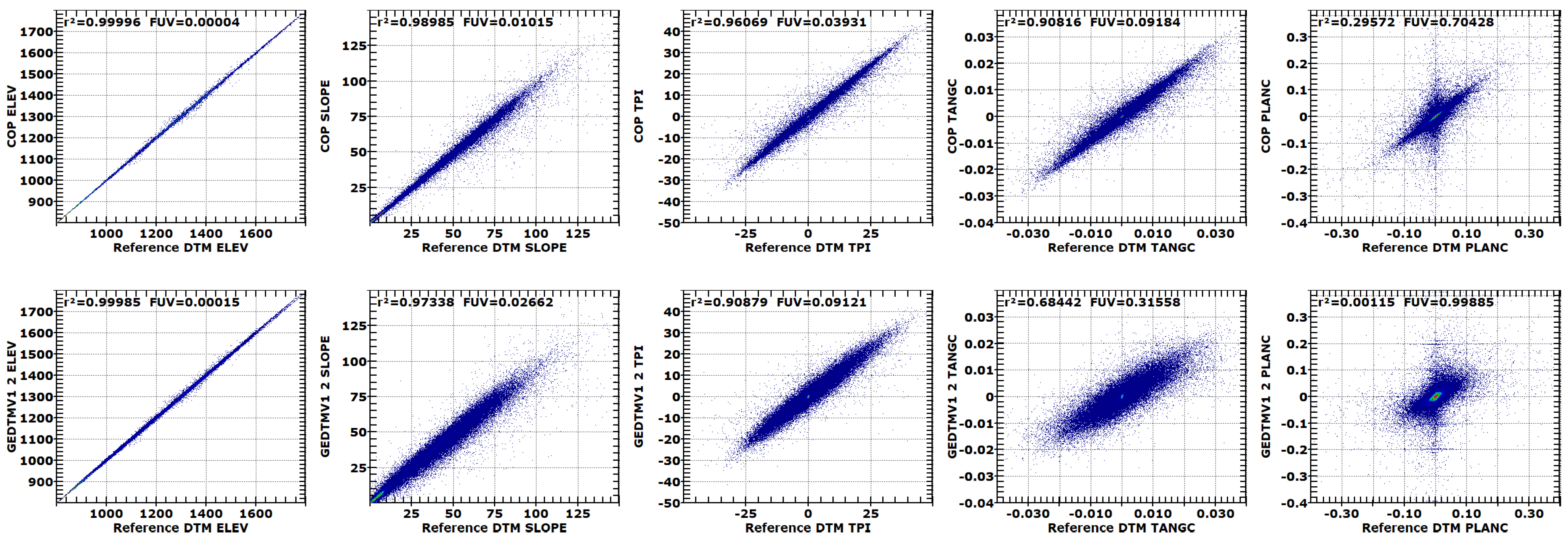

- The capability of global DEM to represent land surface parameters, such as slope, curvatures, and roughness changes in relation to land cover and morphology. Parameters computed with the second order partial derivatives show a range of correspondence, and those computed with third order partial derivatives show extremely low correspondence.

- The procedures for creating a bare earth digital elevation from a digital surface model are a black box that can hallucinate, and the results must be checked carefully. The creators should check derived land surface parameters as well as the raw elevation values, as a good digital surface model can be better than a poor digital terrain model.

- Geomorphometry workers must carefully assess the land surface parameters they use. First derivative parameters perform best; second derivative parameters, like curvature, vary in their signal-to-noise ratio; the third derivative parameters, like change of curvature, might be all noise.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Accuracy Assessments of DEMs

1.2. Rationale for This Work

1.3. UTM-Based DEMIX Tiles

- Online government portal to download DTMs in Geotiff format.

- Grid spacing of 2 m or smaller. If the country has several resolutions, such as Switzerland, we use the larger grid spacing as aggregation to one-arc-second will not benefit from the smaller grid spacing.

- Vertical datum shifts to EGM2008 from the original datum supported by GDAL [28]. If this is not possible, we can use the DEM only for LSPs that do not depend on absolute elevation values.

- Availability of tiles approximately 10 × 10 km, or under 10 × 10 km that can be merged into tiles of approximately 10 × 10 km. This rules out huge, multi-GB files. While we could extract tiles from such files, it would not add much to the diversity of test areas.

- Elevations in floating point meters with resolution to at least a decimeter.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Key Definitions

- Criterion: LSP used to compare a test and reference DEM.

- Evaluation: numerical result of a comparison between a test and reference DEM.

- Reference DTM: our best estimate of the true bare earth surface, created from a high-resolution DTM to match the pixel geometry and spacing of the test DEM.

- Test DEM: one of the group of 1-arc-sec DEMs being compared. The only changes to the test DEMs are a vertical datum shift if required to move to EGM2008.

2.2. Summary of Current Procedure

- Test DEMs are 1-arc-sec DEMs, WGS84 horizontal datum. We shift AW3D30 to the EGM2008 vertical datum used by the others. Some earlier versions of GEDTM have 0.9-arc-second spacing, which required special creation of references DTMs at that pixel size for version 3.5 of our database [26].

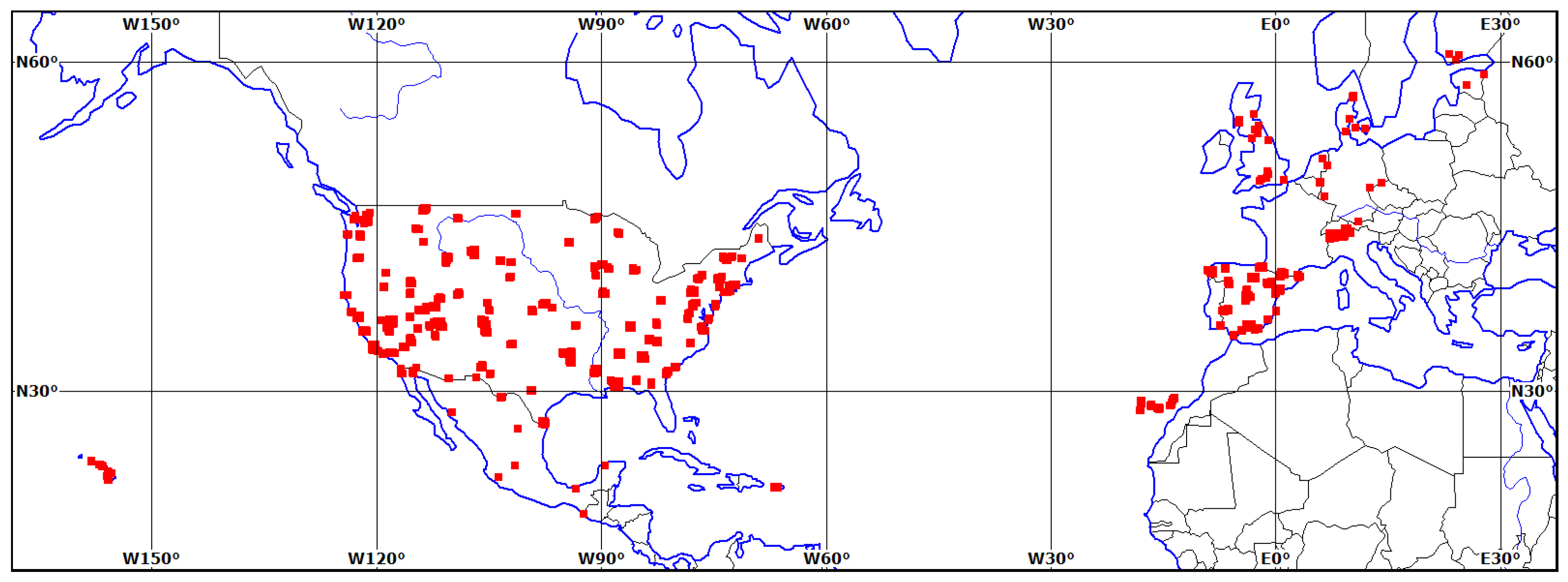

- Download high-resolution DTMs from the governmental mapping agency. Table 1 shows the national data sets we have used. Our primary US data source [41] delivers 10 × 10 km tiles with a very small boundary buffer. Due to the large size of the US and the wide range of landscapes, we feel it provides a good sample of Earth’s topography, but the additional countries in Mexico and Western Europe extend our sample.

- Use GDAL [28] to shift the source DTMs from the local projection and datum to the WGS84 ellipsoid and EGM2008 vertical datum, shifting to a UTM projection for countries that use a national projection. This results in small shifts both horizontally and vertically, which are much smaller than one arc second.

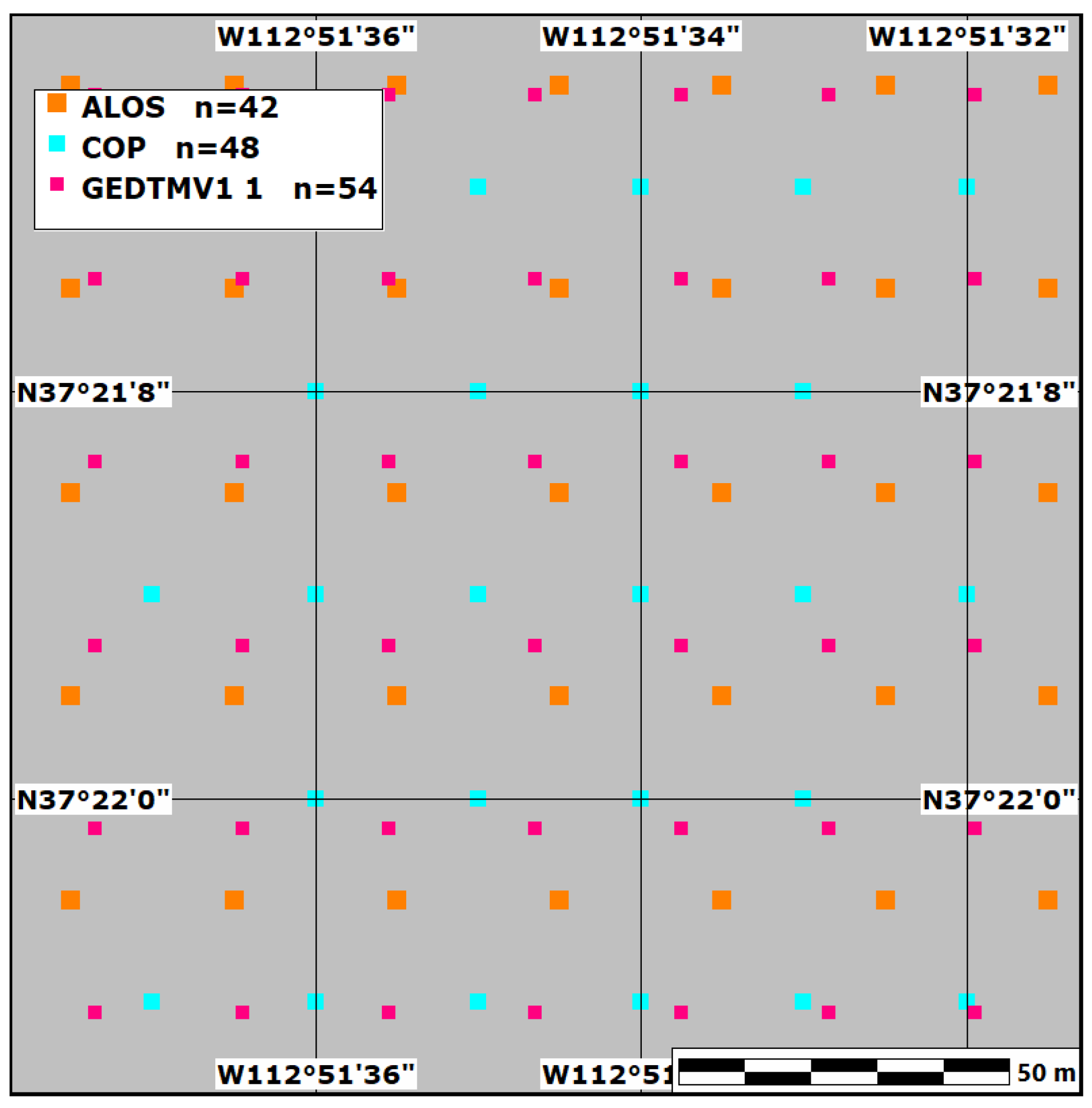

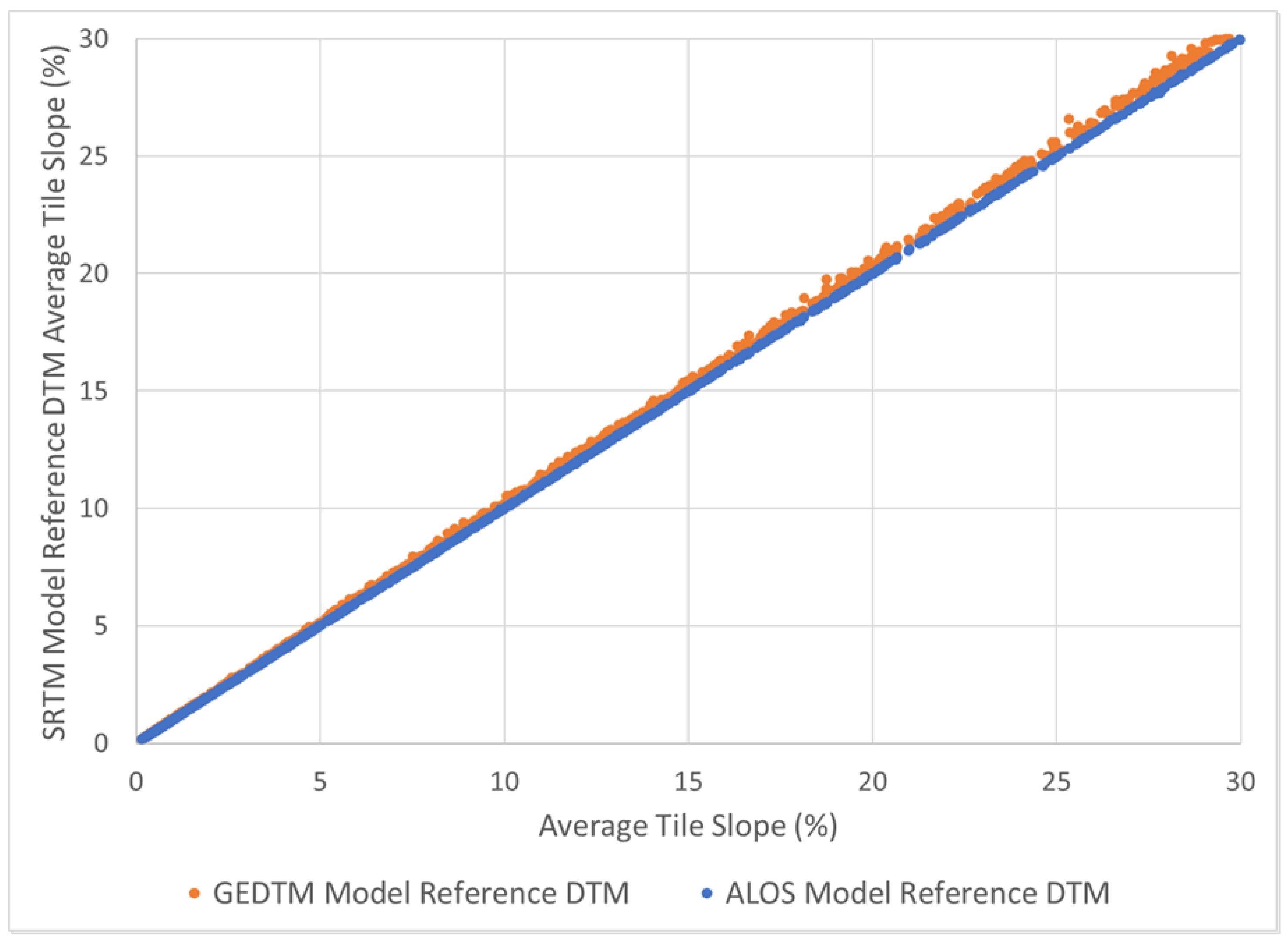

- For each test tile, create two reference DTMs (1-arc-sec SRTM geometry and 1-arc-sec ALOS geometry), and when required at higher latitudes, reference DTMs with increased longitudinal spacing. We use mean aggregation into the rectangular pixels in the geographic reference DTMs for the two geometries. The geographic grid will have small triangular missing data regions on each edge of the DEM, whose size varies with distance from the central meridian of the UTM zone. These missing data regions are ignored for the computations to follow, and have negligible effect on the statistics.

- Use a number of land surface parameters (LSPs) as analysis criteria, computed with open source programs.

- For each criterion, compute the Pearson correlation coefficient (r2) between the LSP derived from the test DEM with the appropriate reference DEM, with pixel centroids at the same geographic location.

- Mask out water using the landcover [43].

- Compute the fraction of unexplained variance (FUV), which is (1 − r2). This ranges from 0 (best) to 1 (worst).

- Create a database by computing FUV statistics for the LSP criteria for each test tile.

- Create a database for the different distributions used in the first DEMIX work [18].

- The resulting databases have a row for each DEMIX tile and criterion, and a column for each test DEM.

- Compute tile characteristics from the SRTM geometric model one-arc-second reference DTM, and the 10 m landcover, and merge them into the other databases.

2.3. Changes to Method

- We have slightly changed the selection of FUV criteria used. The actual criteria are less important than the patterns. All selected criteria are now computed with free, open-source software.

- We do not compute or use the per-pixel raster classification or vector comparison criteria, which we find redundant as they follow the same trends as the grid FUV criteria.

- All tiles have at least 35,000 valid points after water masking. The number varies because the UTM tiles have variable numbers of points due to irregular boundaries along the coast, political boundaries, or mapping project edges.

- We did not analyze coastal test DEMs. There have been a few recent changes in the edited coastal DTMs, and the conclusion that low-relief coastal DEMs at the one-arc-second scale do not perform well remains valid [25].

- We have slightly fewer test tiles after changing from GEO to UTM tiles, but more test areas. We removed some areas that did not meet our improved requirements, and some coastal areas, because of their demonstrated poor performance. When we added additional tiles, we opted for more test areas with fewer tiles each to add more geographical variety.

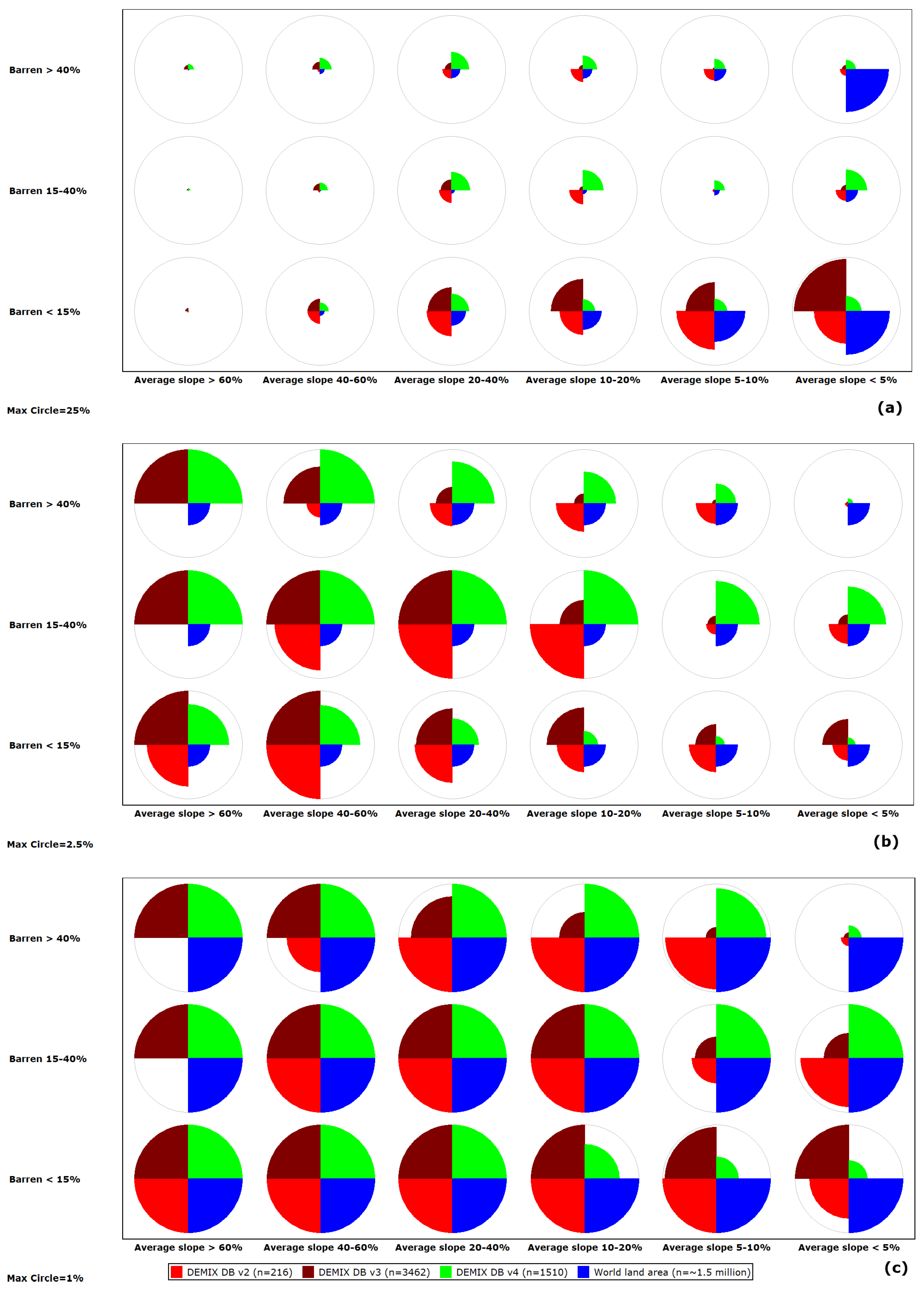

| Bielski et al., 2024 [18] | Guth et al., 2024 [25] | This Work | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database version | v2 [50] | v3 [49] | v3.5 [26] | v4 [51] |

| Test areas | 24 | 124 | 140 | 155 |

| Test tiles | 236 | 3462 | 1381 | 1510 |

| Tile geometry | Geographic [27] | Geographic [27] | National DEM projection (Table 1) | National DEM projection (Table 1) |

| Global DEMs | ALOS, ASTER, CopDEM, FABDEM, NASADEM, SRTM | ALOS, ASTER, CopDEM, FABDEM, NASADEM, SRTM, TanDEM-X | ALOS, CopDEM, FABDEM, FATHOM, EDTM, 3 GEDTM | ALOS, CopDEM, FABDEM, FATHOM, GEDTM |

| Coastal DEMs | Coastal; Delta; Diluvium | |||

| Difference distribution criteria | Elevation; slope; roughness; 5 measures each | Elevation; slope; roughness; 5 measures each | Elevation; slope; roughness; 5 measures each | Elevation; slope; roughness; 5 measures each |

| Mixed FUV criteria | 17 | 15 (open source software) | 15 (open source software) | |

| Pixel classification criteria | 8 | |||

| Vector match criteria | 2 | |||

| Partial derivative FUV criteria | 11 | 11 | ||

| Curvature FUV criteria | 28 | 28 |

2.4. Test Areas

2.5. Test DEMs Considered

2.6. DEMIX Database Version 4

- Difference distributions for elevation, slope, and surface roughness. The provides continuity with [18,25], but has limited usage in this paper because FUV provides better results [25]. For readers who want, it includes statistics like RMSE and LE90 for elevation, slope, and roughness, as well as the signed mean and median differences.

- FUV for a mixed suite of LSPs chosen to sample the full range of LSPs calculated from DEMs. These provide better rankings of the test DEMs, an estimate of the robustness of LSPs, and suggest that some LSPs should be used with caution.

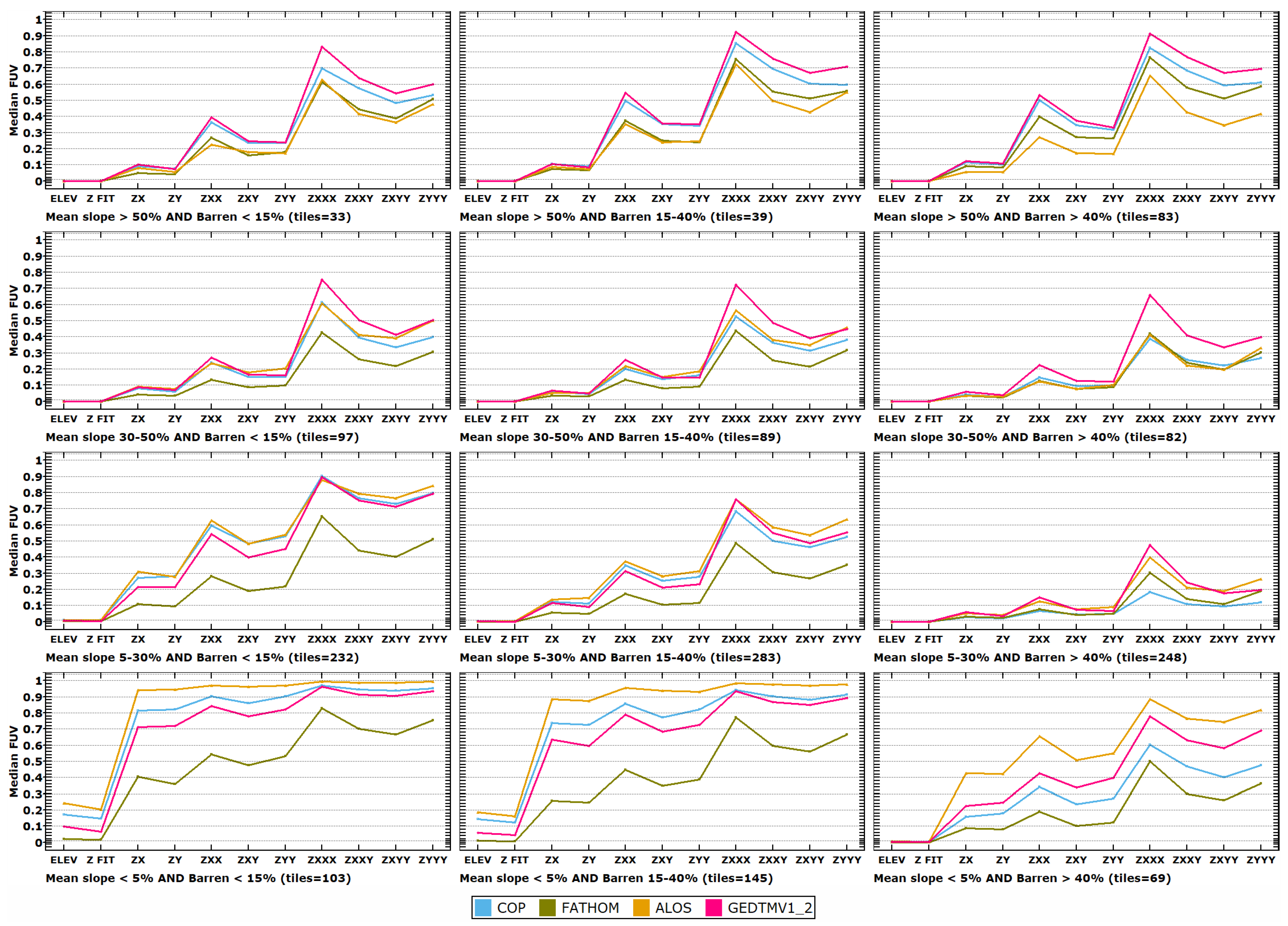

- FUV for the partial derivatives used for slope, aspect, and curvature. These results support our recommendations about LSPs.

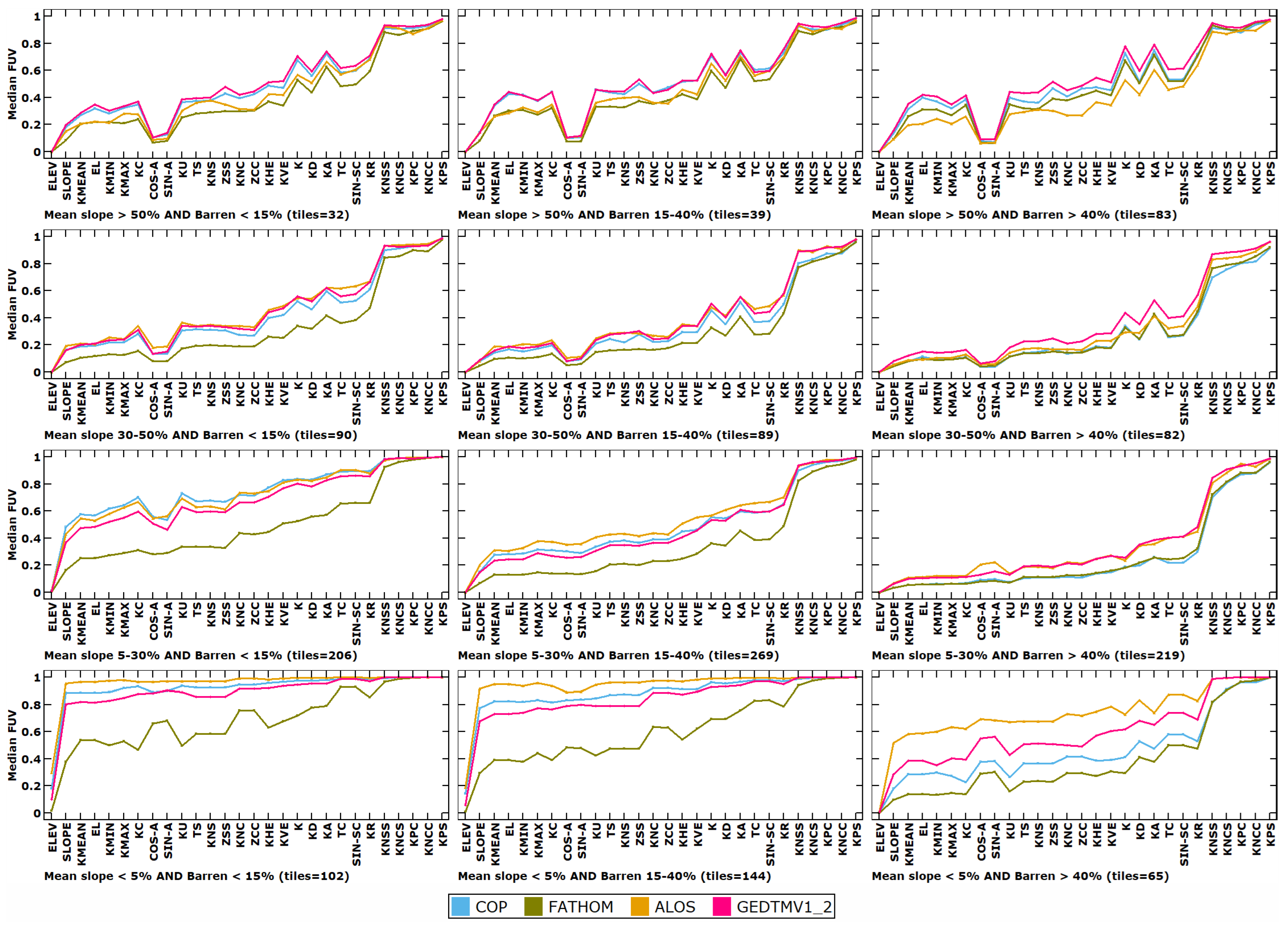

- FUV for the full suite of integrated curvature measures [48]. The slopes and curvatures in this table differ from those in the mixed suite of LSPs, which use computations with a more traditional, smaller window and lower-order polynomial. It is beyond the scope of this paper to compare the different slope and curvature algorithms, but our results will address the utility of this large suite of measures.

2.7. Criteria Used for Evaluations

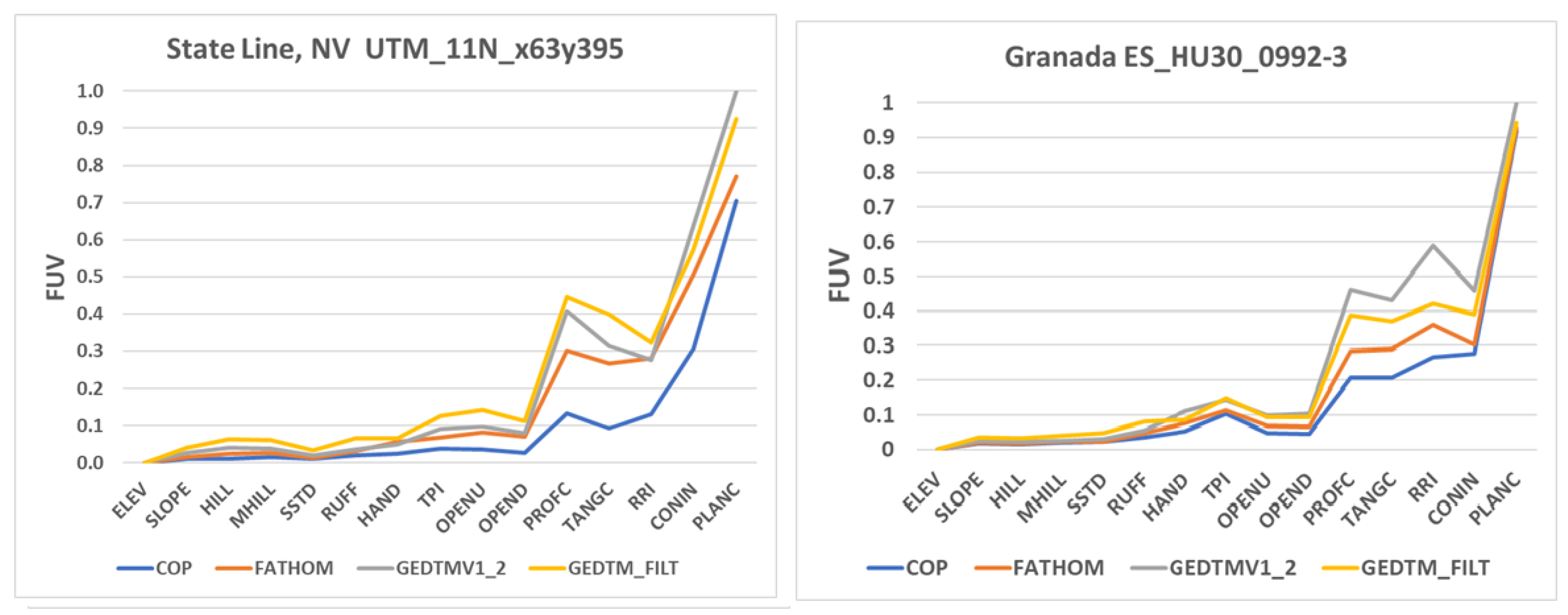

2.8. FUV Example

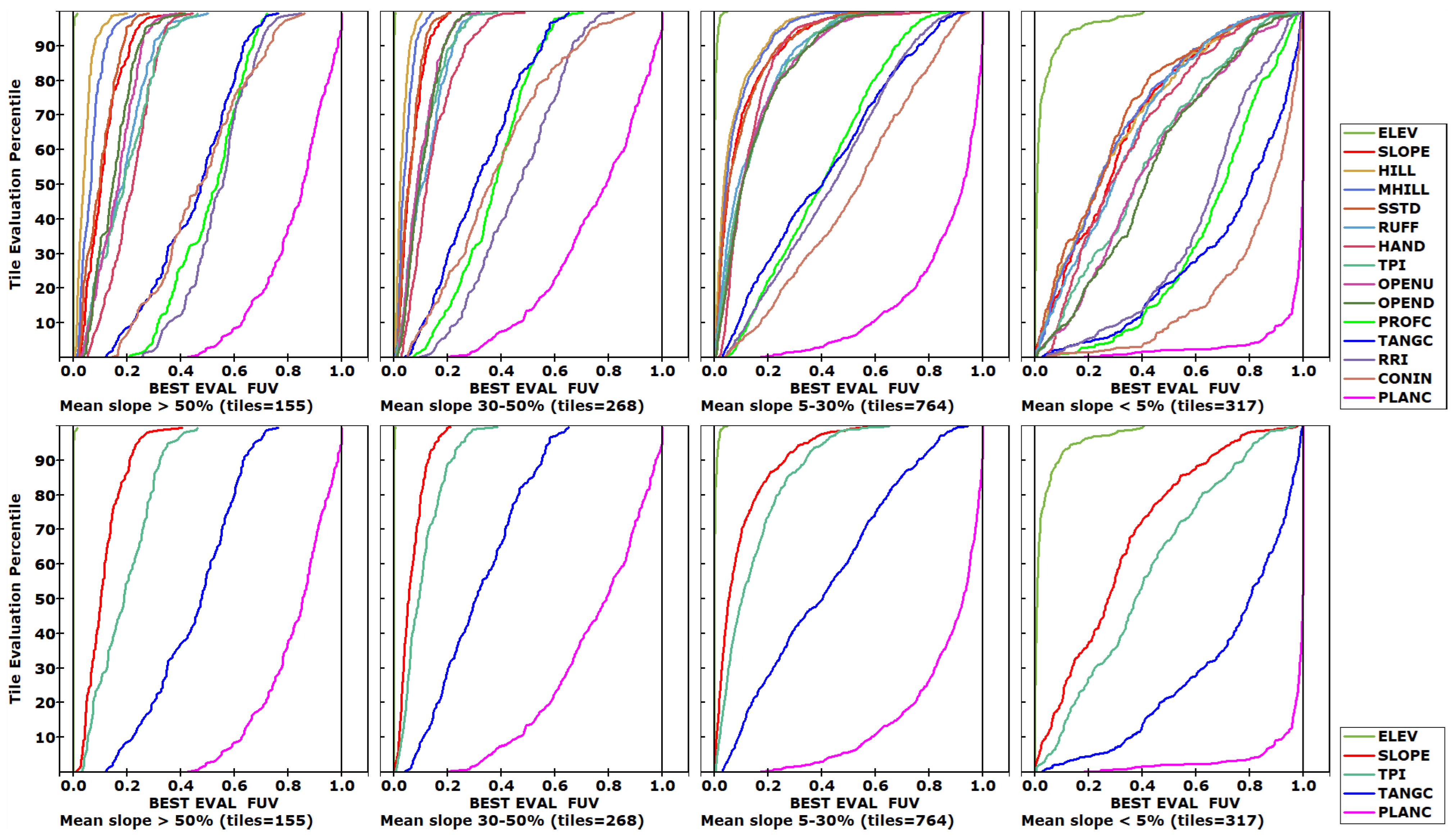

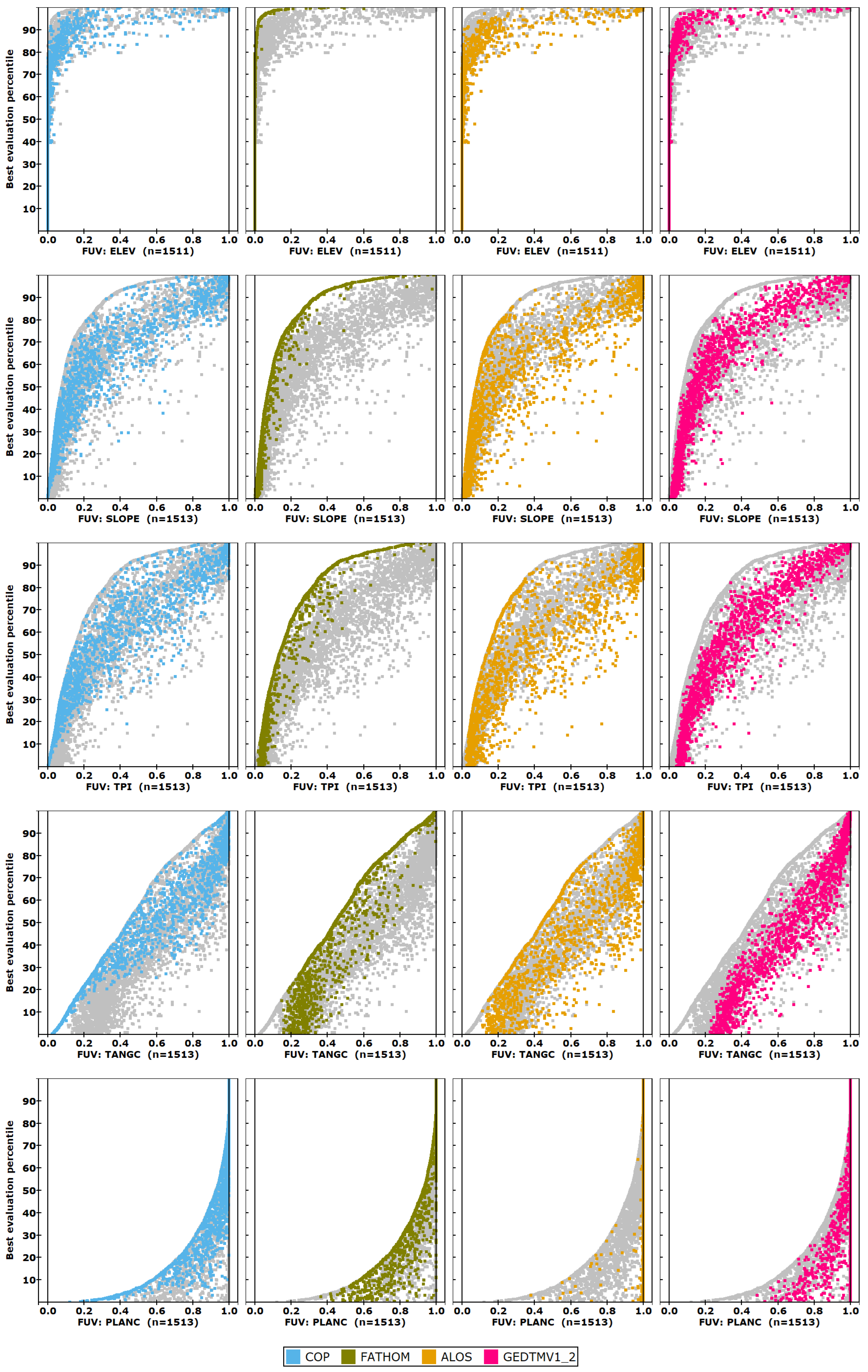

3. Results

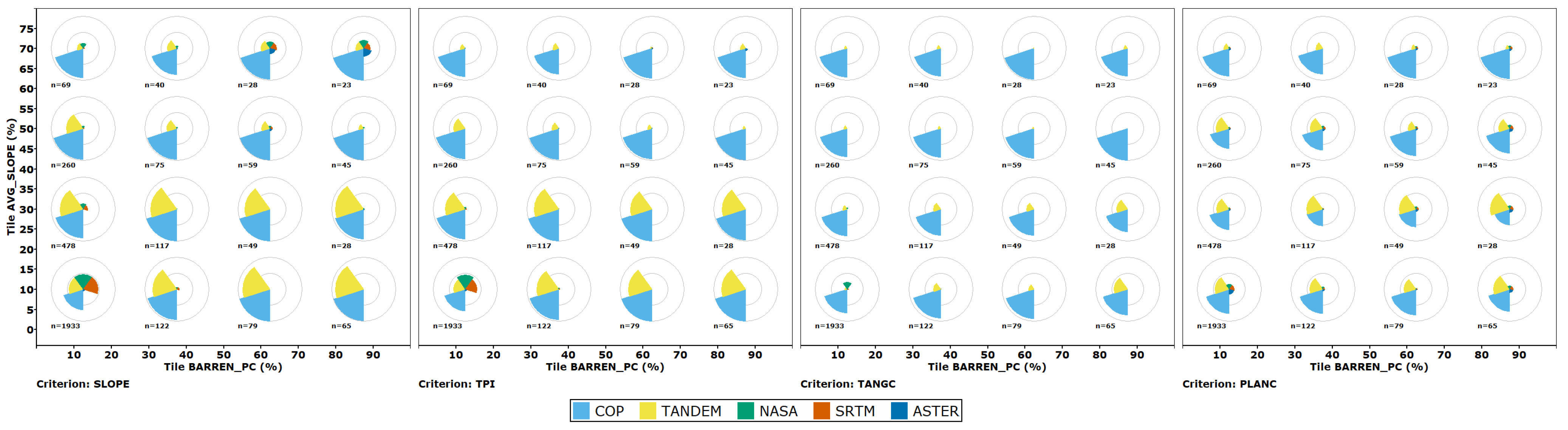

- Differences among test DEMs.

- Different responses among LSPs used as criteria.

- Characteristics of the landscape in each test tile (average slope, average roughness, percent barren, forest, urban).

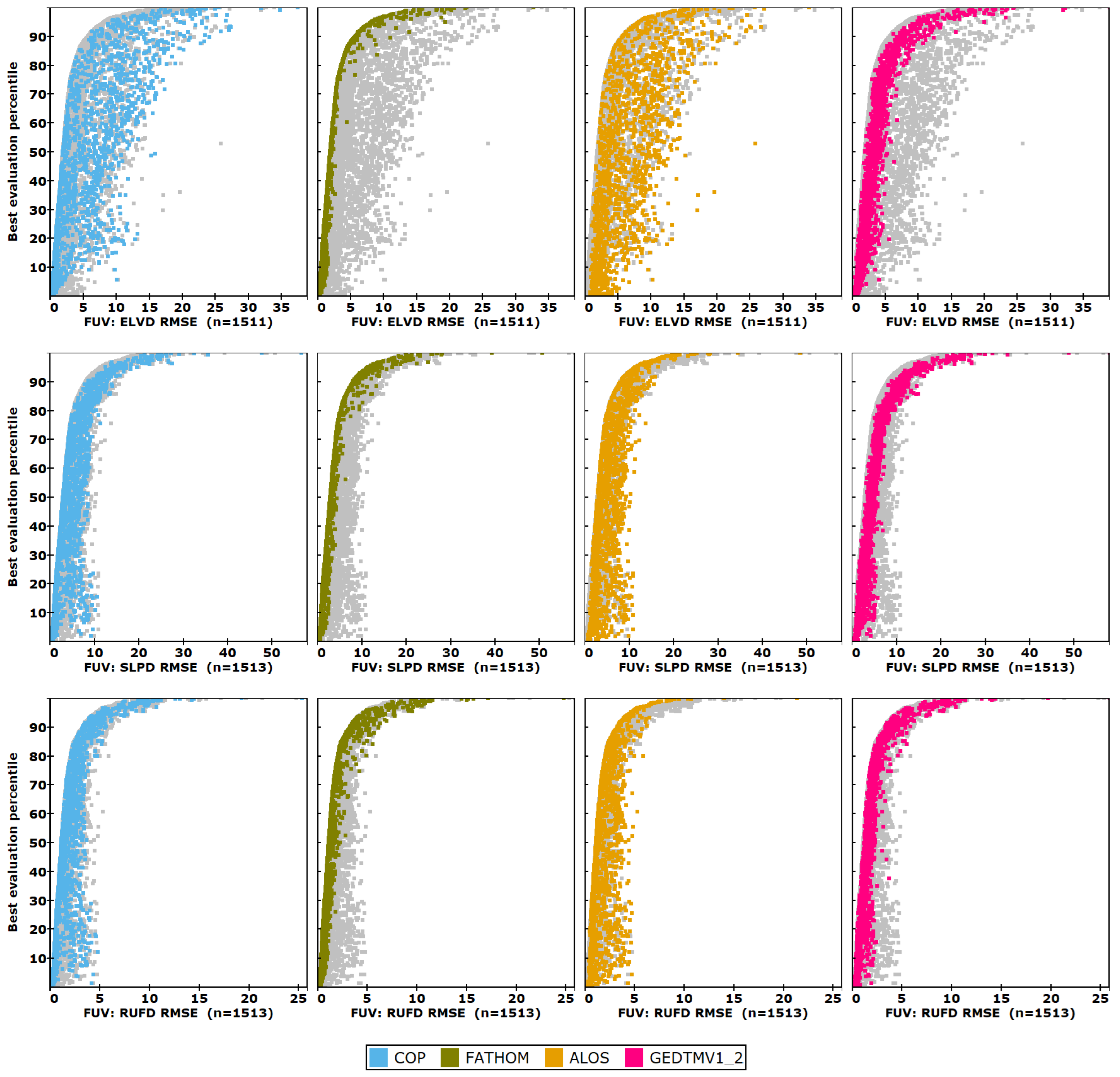

3.1. Best Evaluation in Each Tile

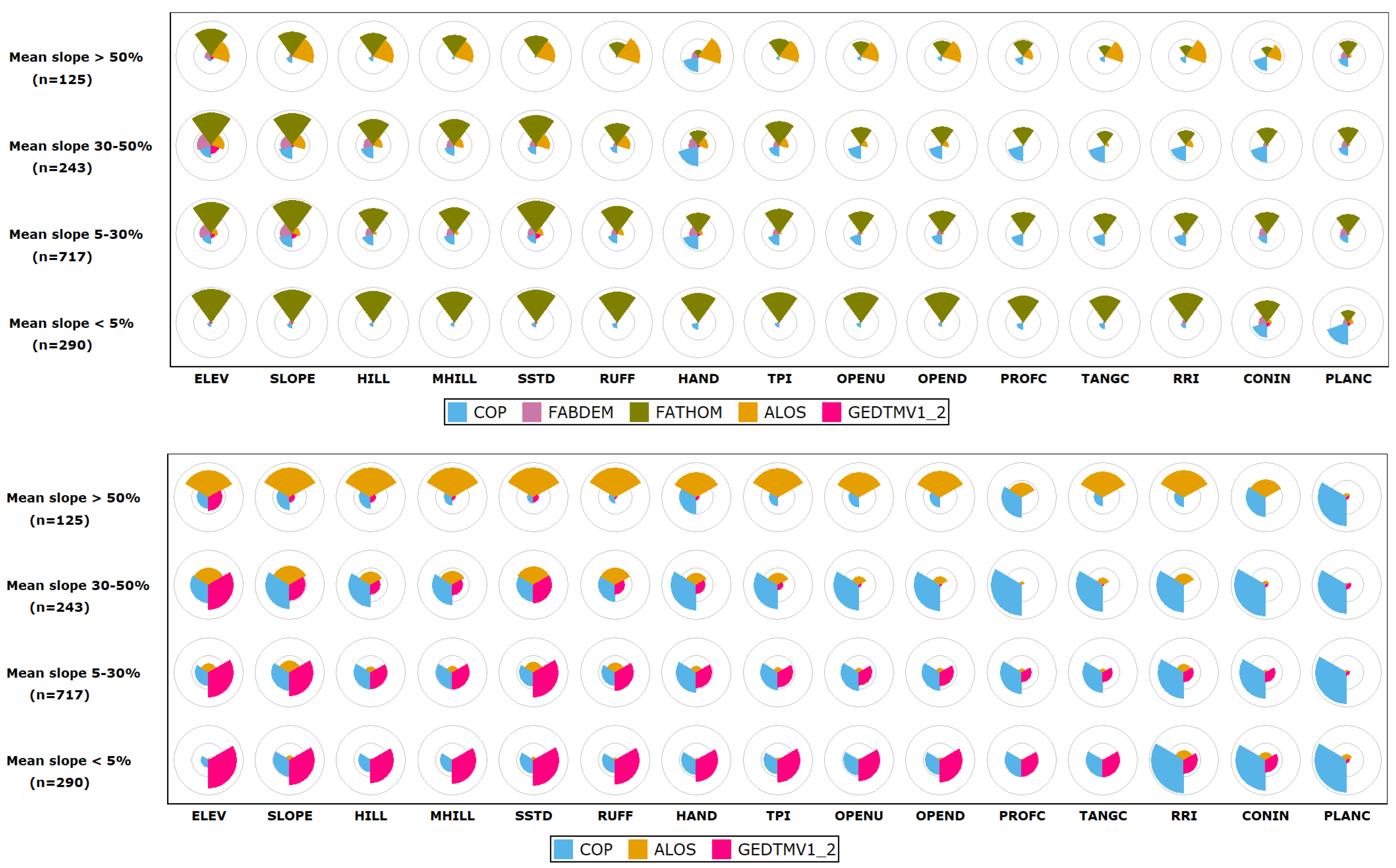

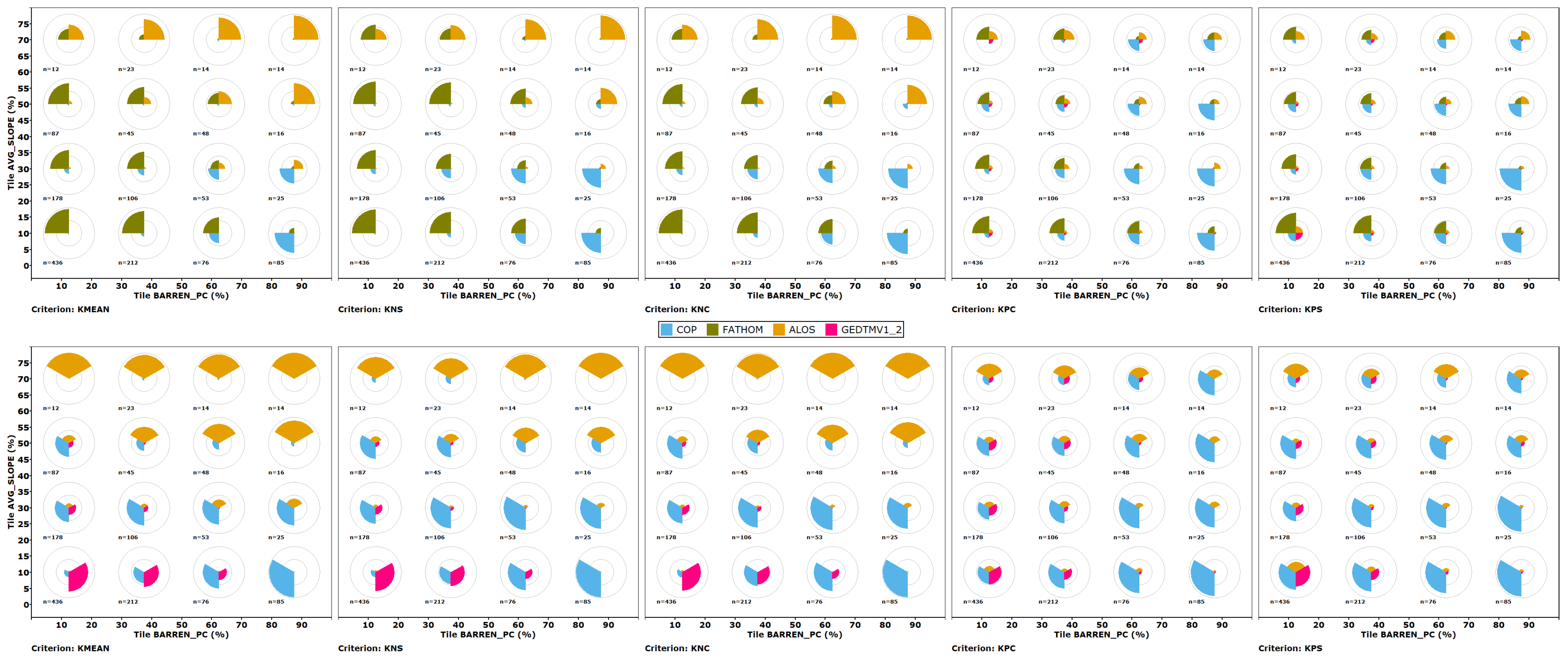

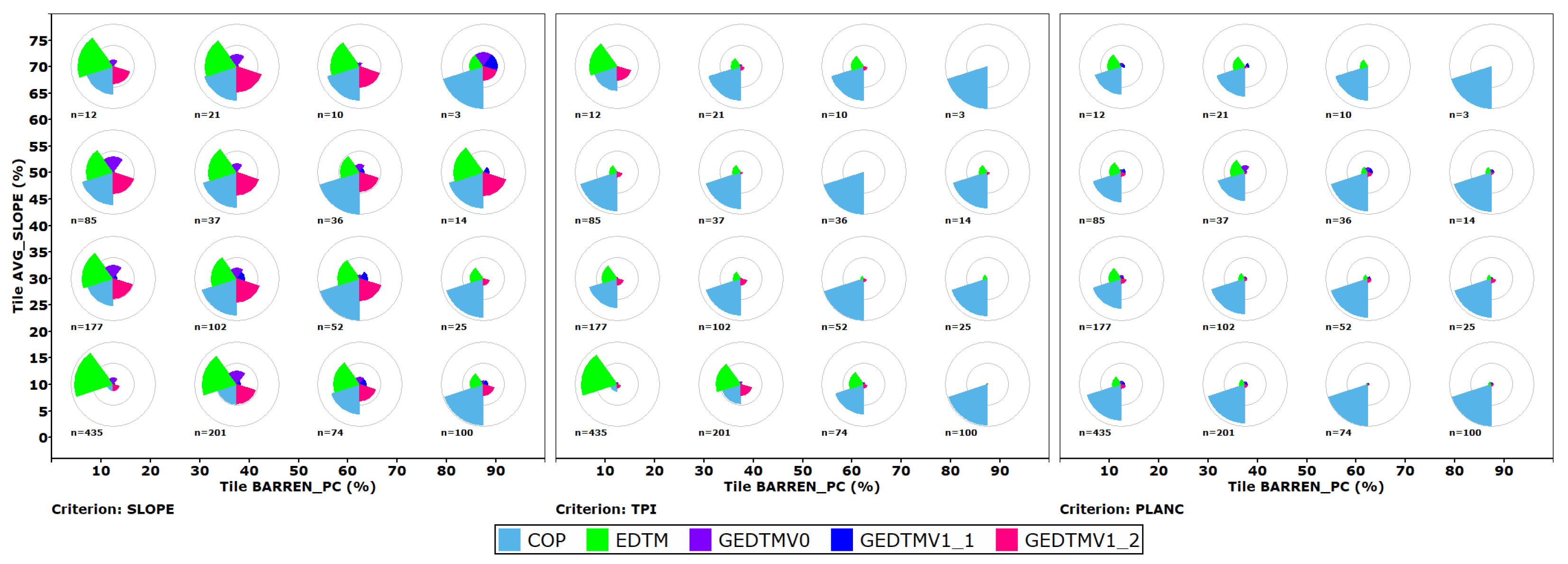

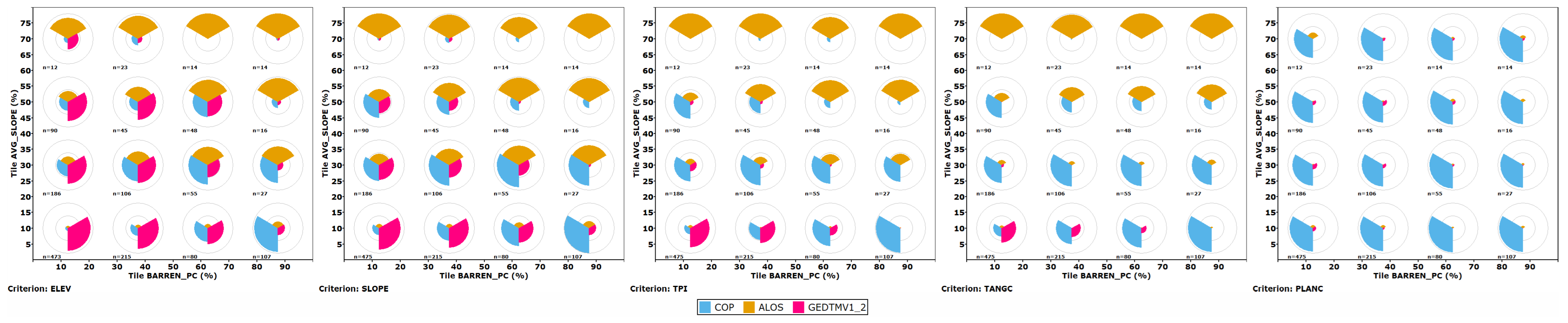

3.2. Evaluations Sorted by Tile Average Characteristics

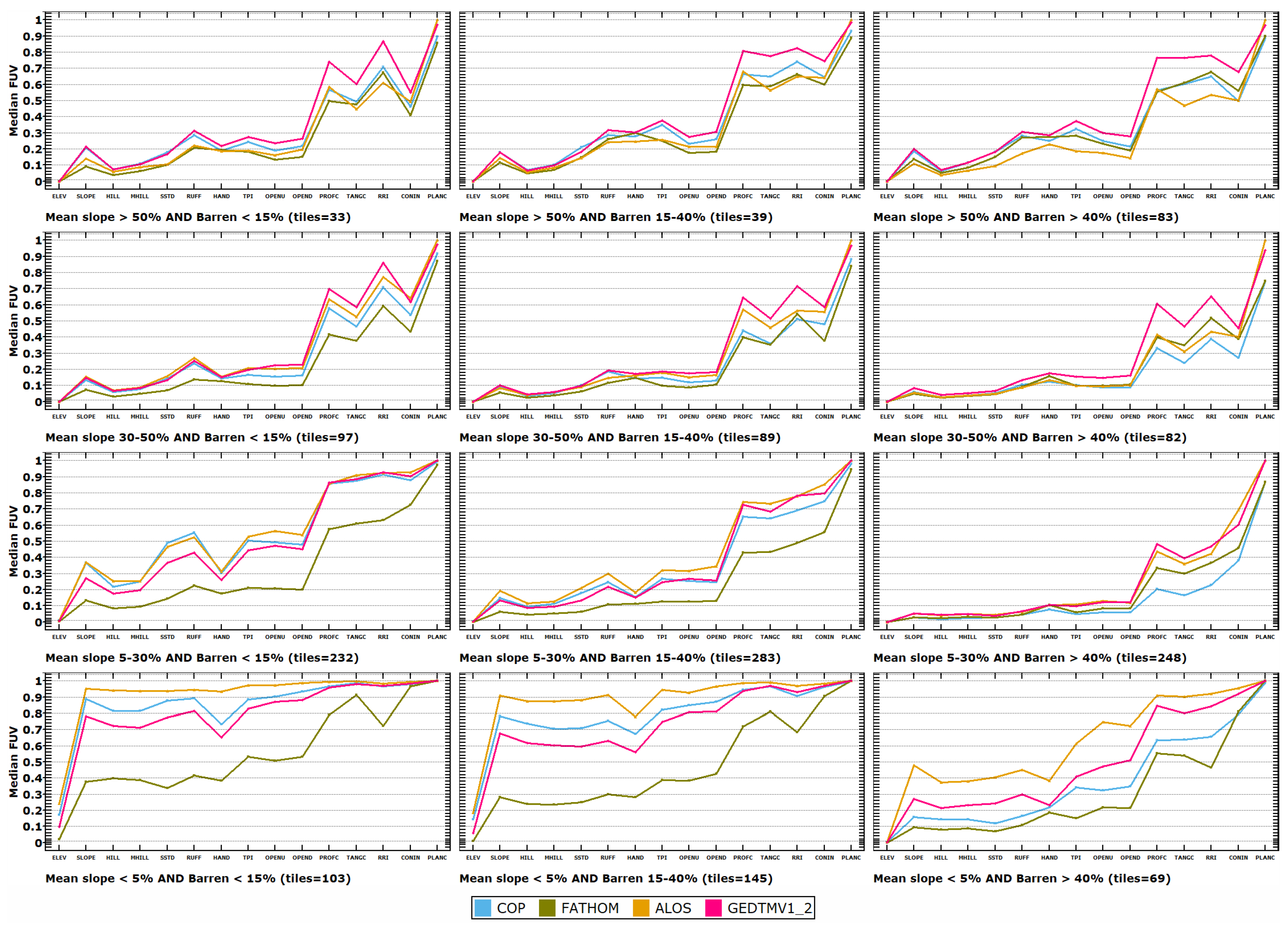

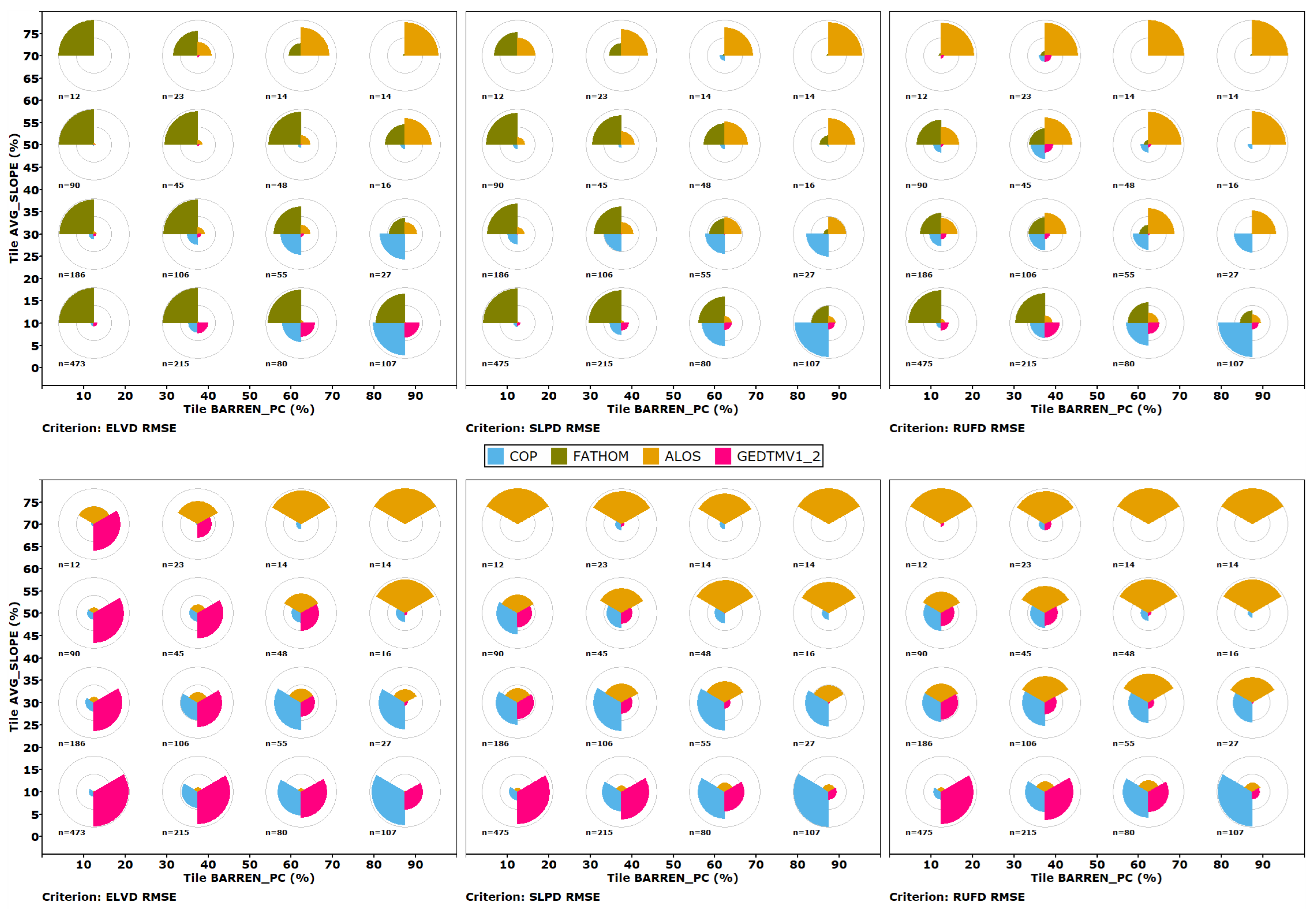

3.3. Evaluations Lumped by Terrain Categories

3.4. Performance Ranking of LSP Criteria

- The best criteria depend only on simple operations with first partial derivatives, SLOPE, and the two hillshades, which depend on the normal vector to the earth’s surface, a 3D representation of slope and aspect.

- In general, the curvature criteria, requiring second-order partial derivatives, perform more poorly compared to the other LSPs in Table 4.

- ALOS generally performs worse than CopDEM, and its integer resolution elevations provide coarser resolution, making it harder to match the reference DTM.

- Roughness is a complex metric without a common definition, and two of our metrics have been used for roughness, RUFF (standard deviation of slope) and RRI. RRI is more sensitive, with a larger FUV.

3.5. Effect of Terrain on Criteria Performance

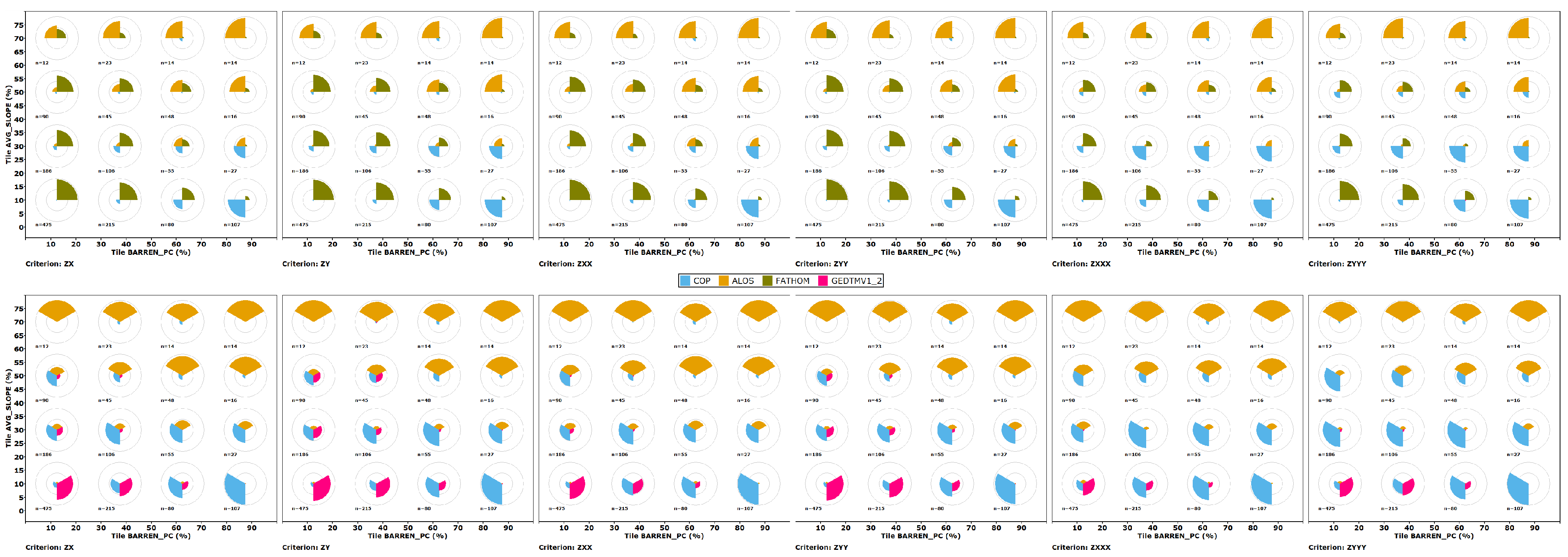

3.6. Effect of Terrain on Partial Derivatives

3.7. Effect of Terrain on Curvature Measures

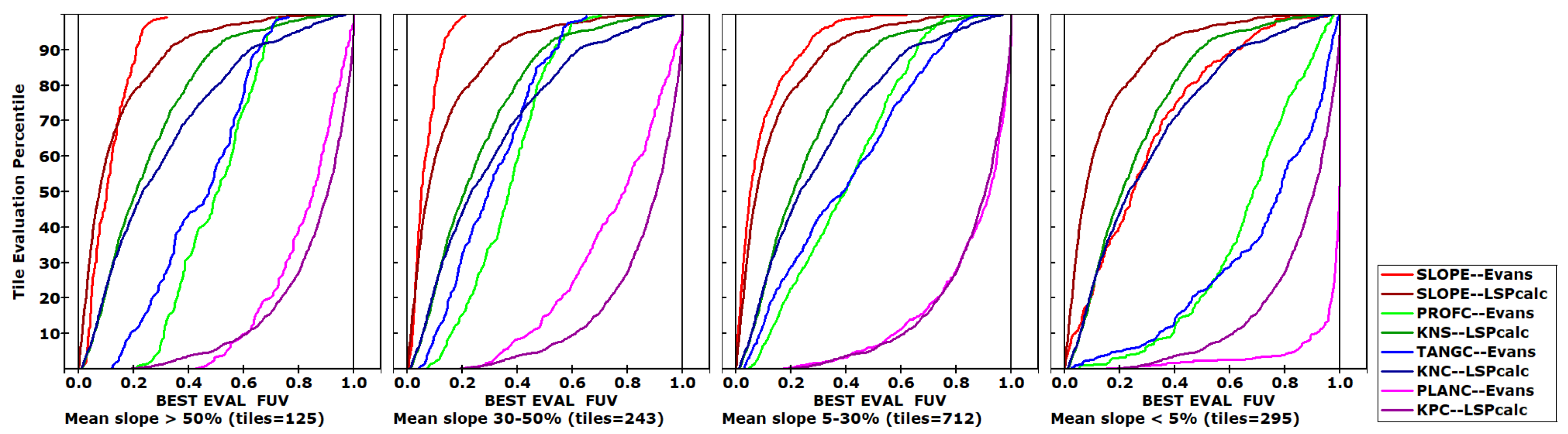

3.8. Comparing Curvature Algorithms on FUV

- For the tiles with the shallowest slopes, the LSPcalc algorithm performs best for all four of these criteria. These tiles perform poorly for all the criteria, because the algorithms amplify the small elevation differences between the test and reference DEMs. The combined effect of a larger window and higher-order polynomials lessens the differences between the test and reference DEMs.

- For the higher slope tiles, the Evans method generally works slightly better for SLOPE and PLANC/KPC, and worse for PROFC/KNS and TANGC/KNC.

- PLANC/KPC performs poorly for both algorithms, and should be used with caution.

3.9. Limitations of Simple Difference (Error) Metrics

4. Discussion

4.1. DEM Winners—Choosing the Best DEM

- Which LSPs to use, either the ones we computed or others.

- Which of our four tables to use.

- The tolerance to decide if evaluations are different or tied. The tolerances represent our subjective estimate and are defined in the parameter tables, and the evaluation software is set up to allow easy changes to the tolerances without recompiling the code or recomputing the database.

- Whether to average multiple criteria for a single evaluation, or keep each criterion separate.

- The landscape categories to consider.

4.2. DEM Winners—Mixed LSPs

4.3. DEM Winners—Difference Distributions

- FathomDEM is generally the best, considering all four DEMs. CopDEM is best in many tiles with low slope and high barenness, and ALOS is best in high slope and barren tiles.

- Among the unrestricted license, GEDTM performs best for low slope tiles that are not barren, ALOS best for high slopes, and CopDEM for intermediate cases.

- The cases where ALOS is best are characterized by small numbers of test tiles. The superior performance of ALOS in steep terrain is consistent in all our results and with previous results [25,67], but such steep terrain is relatively rare globally, and the preferential use of ALOS should be restricted to those areas.

- The three metrics considered for the difference distributions are the best, fourth, and sixth best of the criteria used in our FUV comparisons (Table 4 and Figure 7). Using more criteria, particularly for the LSPs that consistently compare worse to the reference DTM, can change conclusions from this simpler analysis using just these three criteria.

4.4. DEM Winners—Partial Derivatives FUV

4.5. DEM Winners—Curvatures Family of LSPs

4.6. Can a DSM Be “Better” than a DTM?

4.7. EDTM, GEDTM, and Precomputed LSPs

4.8. Is Filtering DEMs the Answer?

- Should we only filter GEDTM, or should we filter all the test and reference DEMs? CopDEM, produced by aggregating higher resolution radar data, might have been filtered implicitly during aggregation or as a later processing step.

- If a DEM needs to be filtered, we think that it would most often apply to all users and would best be applied by the data producer, and not left to the end user.

- Filtering changes the data support, complicating the comparison we want to make.

- Any pre-processing applied by the data producer must be carefully considered. For example, not all users might want depressions filled, because the loss of real features like sinkholes, quarries, or bomb craters might not be justified to create a drainage network that does not actually exist in those areas. Fixing hydrology can lead to other undesired changes in the DEM [71].

- Filter the DEM before any analysis.

- Reduce the DEM resolution before analysis, and compute the LSP only on a smaller grid.

- Filter the LSP after computation.

- Should all LSPs use the same filter, or should slope be handled differently than change of curvature, since our results indicate that those LSPs have very different characteristics?

- Do all DEMs require the same filtering?

4.9. Suggestions for DTM Creators

4.10. Best DEM Locally or Consistent DEM Globally?

4.11. Future Directions for DEM Comparisons

- Improve the metrics we use to determine whether our selection of test tiles is representative of the world. There is a wide range of potential data sets classifying geomorphology, climate, and vegetation, and the choice must find a balance between over-specifying categories and generalizing into larger categories. For instance, we could use 14 biomes or 846 ecoregions [79], which have significant implications for how we should select a test area. While every one of the 1.5 million 10 × 10 km areas in the world is unique, we need a much smaller number of categories that we should match.

- Improve the geographic distribution of our test tiles. The limited number of test tiles in the southern and eastern hemispheres in the earlier versions of our work did not meet the criteria we specified when we redesigned the methodology to use projected national coordinates to define test areas. Hopefully, more lidar-derived DEMs will become available, and we can also investigate if we can relax our criteria. The vertical datum shift was the most restrictive criterion we used, and one way to mitigate its impact would be to use derived LSPs and not consider raw elevation. Not matching the vertical datum does not affect almost all LSPs, which only consider neighborhood elevation differences.

- To some degree, these improvements are related. If we are confident that we have DEMs in Western Europe or North America that match the characteristics that we think affect the quality of a DEM, then it becomes less important that we have reference DEMs from every region or country. We can reliably measure the global characteristics with satellite data, which effectively covers the world.

- Consider using landforms to evaluate if our test tiles are representative. The atlas of archetypal landforms [80,81,82] highlights some of the challenges we would see. The atlas has 10 DEMs with resolutions between 0.5 and 10 m, with sizes between 1.5 × 1.5 km and 45 × 45 km, and are coded for 22 different landforms. The extents of the tiles and selected resolution were manually determined by experts. In contrast, our tiles were selected quasi-randomly based on the map tiles distributed by national mapping agencies, and the target scale of the one-arc-second global DEMs we evaluate results in the landscapes appearing very different, and all the tiles are approximately the same size.

- Two specific landforms show some of the issues we foresee. Karst embodies a number of forms, from sinkholes to cockpit karst with very different geomorphology, and only the largest features will appear at a one-arc-second scale. We could take a map of potential karst in the United States, which has 6 categories [83], to see how many of our tiles could be categorized as karst. This would include the tiles at Mammoth Cave and Puerto Rico, but the vegetation there might be a bigger factor than the karst features apparent with 30 m pixel spacing. Volcanoes might be easier as a landform category, with 1429 Pleistocene and 1232 Holocene volcanoes in the world as picked by experts [84]. With 1.5 million 10 × 10 km tiles in the world, for each age, the probability of a volcano in any given tile would be about one in a thousand (and our sample includes Mount Saint Helens). Is that enough, or should we over-represent volcanoes? Do we need to sample the most common types (shield and strato volcanoes), and do we need multiple examples to trust that the samples are truly representative and not more related to slope or forest cover? Stepping back, how many landforms do we need to cover? Every earth scientist will have favorites; structural geologists might want to see fault block mountains, not included in [80,81,82].

- Evaluate urban test areas. While we did not actively select urban areas, the urban percentage of our test tiles matches the global distribution. This could result from the size of the tiles, where a few 10 × 10 km tiles will contain only urban 10 m pixels. All of the one-meter DTMs we have seen (the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and the US) have very clear remnants of the roads and building footprints, which clearly survive aggregation to 5 m resolution, and are still visible at 30 m, which decreases our confidence in our urban reference DTMs. Lidar sees the world differently than optical or radar satellite sensors, and reconciling the two is not simple. We think there is more required than simply adding test areas for New York City, Paris, and London. Users of the one-arc-second DEMs in urban areas need to consider their purpose and the appropriateness of one-arc-second data.

- Evaluate tiles with tropical forests, for which we should be able to find test areas, and keep looking for desert areas in the great belt from North Africa through the Middle East into Central Asia. We already have some desert areas (e.g., Colorado’s Great Sand Dune, but they lack the great dune fields where a DSM and DTM should be identical. Users who want guidance on the best global DEM to use in those cases must use our general guidance and determine which DEM would be best in their circumstances.

- Investigate alternative aggregation methods to create the reference one-arc-second reference DTM from the one-meter source DTMs. Our current method uses mean aggregation, effectively mean filtering over an irregular rectangular window, and we might use the median, or a weighted function that places more weight on the central point.

- Investigate the need for filtering before creating LSPs. The recommendations to filter first are several decades old, when DEMs had only a meter vertical resolution and were created with very different technology. We see three questions that further research should resolve: (1) should all DEMs be filtered; (2) should the producer or user do the filtering; and (3) what filter should be used.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALOS | AW3D30 DEM |

| COP, CopDEM | Copernicus DEM |

| DEM | Digital elevation model |

| DEMIX | Digital Elevation Model Intercomparison Exercise |

| DSM | Digital surface model |

| DTM | Digital surface model |

| FUV | Fraction of unexplained variance |

| GNSS | Global navigation satellite system |

| LE90 | Linear error 90th percentile |

| LSP | Land surface parameter |

| MAE | Mean average error |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

References

- Guth, P.L.; Van Niekerk, A.; Grohmann, C.H.; Muller, J.P.; Hawker, L.; Florinsky, I.V.; Gesch, D.; Reuter, H.I.; Herrera-Cruz, V.; Riazanoff, S.; et al. Digital Elevation Models: Terminology and Definitions. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, F.; Paiva, R.; Durand, M.; Alsdorf, D.; Bates, P. A multi-sensor approach towards a global vegetation corrected SRTM DEM product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 182, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, D.; Ikeshima, D.; Tawatari, R.; Yamaguchi, T.; O’Loughlin, F.; Neal, J.C.; Sampson, C.C.; Kanae, S.; Bates, P.D. A high-accuracy map of global terrain elevations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 5844–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, L.; Uhe, P.; Paulo, L.; Sosa, J.; Savage, J.; Sampson, C.; Neal, J. A 30 m global map of elevation with forests and buildings removed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 024016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.F.; Grohmann, C.; Lindsay, J.; Reuter, H.; Parente, L.; Witjes, M.; Hengl, T. GEDTM30: Global ensemble digital terrain model at 30 m and derived multiscale terrain variables. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blewitt, G.; Hammond, W.; Kreemer, C. Harnessing the GPS data explosion for interdisciplinary science. Eos 2018, 99, e2020943118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevada Geodetic Laboratory. Space Reference Points (SRPs). Available online: https://geodesy.unr.edu/gps_timeseries/IGS20/llh/llh.out (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Han, M.; Enwright, N.M.; Gesch, D.B.; Stoker, J.; Danielson, J.J.; Amante, C.J. Contractor Vertical Accuracy Checkpoints for 3D Elevation Program Digital Elevation Models in the Northern Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coastal Regions, 2012–2020; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2024; Volume 751. Available online: https://data.usgs.gov/datacatalog/data/USGS:64b8833ed34e70357a2b56a0 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Han, M.; Enwright, N.M.; Gesch, D.B.; Stoker, J.M.; Danielson, J.J.; Amante, C.J. Assessing the vertical accuracy of digital elevation models by quality level and land cover. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 15, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIRBUS. Space Reference Points (SRPs). Available online: https://space-solutions.airbus.com/imagery/3d-elevation-and-reference-points/srp/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Zhu, X.; Nie, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, B.; Li, W. Evaluation and Comparison of ICESat-2 and GEDI Data for Terrain and Canopy Height Retrievals in Short-Stature Vegetation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Shan, J. Comprehensive evaluation of the ICESat-2 ATL08 terrain product. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 8195–8209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Yan, B.; Yue, L.; Wang, L. Global DEMs vary from one to another: An evaluation of newly released Copernicus, NASA and AW3D30 DEM on selected terrains of China using ICESat-2 altimetry data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 1149–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracná, P.; Šárovcová, E.; Liu, X.; Eltner, A.; Marešová, J.; Gdulová, K.; Urbazaev, M.; Torresani, M.; Kozhoridze, G.; Moudrý, V. Towards 90 m resolution Digital Terrain Model combining ICESat-2 and GEDI data: Balancing Accuracy and Sampling Intensity. Sci. Remote Sens. 2025, 12, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Washington; NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. SlideRule. Available online: https://client.slideruleearth.io/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. OpenAltimetry. Available online: https://openaltimetry.earthdatacloud.nasa.gov/data/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Guth, P.L.; Geoffroy, T.M. LiDAR point cloud and ICESat-2 evaluation of 1 second global digital elevation models: Copernicus wins. Trans. GIS 2021, 2245–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielski, C.; López-Vázquez, C.; Grohmann, C.; Guth, P.; Hawker, L.; Gesch, D.; Trevisani, S.; Herrera-Cruz, V.; Riazanoff, S.; Corseaux, A.; et al. Novel Approach for Ranking DEMs: Copernicus DEM Improves One Arc Second Open Global Topography. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhe, P.; Lucas, C.; Hawker, L.; Brine, M.; Wilkinson, H.; Cooper, A.; Saoulis, A.A.; Savage, J.; Sampson, C. FathomDEM: An improved global terrain map using a hybrid vision transformer model. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathom (United Kingdom). FathomDEM v1-0 Americas. 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14523356 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Fathom (United Kingdom). FathomDEM v1-0 Eurasia and Africa. 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14511570 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ho, Y.F.; Hengl, T. Global Ensemble Digital Terrain Model 30 m (GEDTM30) (Version 0) [Data Set]. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14900181 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ho, Y.F.; Hengl, T. Global Ensemble Digital Terrain Model 30 m (GEDTM30) (Version 1.1) [Data Set]. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15689805 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ho, Y.F. GEDTM30. Available online: https://s3.opengeohub.org/global/dtm/v1.2/gedtm_rf_m_30m_s_20060101_20151231_go_epsg.4326.3855_v1.2.tif (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Guth, P.L.; Trevisani, S.; Grohmann, C.H.; Lindsay, J.; Gesch, D.; Hawker, L.; Bielski, C. Ranking of 10 Global One-Arc-Second DEMs Reveals Limitations in Terrain Morphology Representation. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, P.L. DEMIX GIS Database Version 3.5 [Data Set]. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/17247343 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Guth, P.L.; Strobl, P.; Gross, K.; Riazanoff, S. DEMIX 10k Tile Data Set (1.0). Dataset on Zenodo. 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7504791 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- GDAL/OGR Contributors. GDAL/OGR Geospatial Data Abstraction Software Library. Open Source Geospatial Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://gdal.org/en/stable/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica (Spain). Download Center. Available online: https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/buscar-mapa (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Danish Climate Data Agency. Denmark’s Elevation Model—Terrain. Available online: https://dataforsyningen.dk/data/930 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Land and Spatial Development Board. Elevation Data Map Sheet Query. Available online: https://geoportaal.maaamet.ee/eng/spatial-data/elevation-data/download-elevation-data-p664.html (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- National Land Survey of Finland. Elevation Model. Available online: https://asiointi.maanmittauslaitos.fi/karttapaikka/tiedostopalvelu/korkeusmalli?lang=en (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- State Office for Geoinformation Saxony. Batch Download. Available online: https://www.geodaten.sachsen.de/batch-download-4719.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Bavarian Surveying Authority. Digital Terrain Model 1 m (DGM1). Available online: https://geodaten.bayern.de/opengeodata/OpenDataDetail.html?pn=dgm1 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- The Surveying and Cadastral Administration of Rhineland-Palatinate. Digital Terrain Model Grid Spacing 1 m. Available online: https://geoshop.rlp.de/opendata-dgm1.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- INEGI. Continental Relief. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/relieve/continental/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (AHN). Data Feed—Digital Terrain Model (DTM) 0.5 m. Available online: https://service.pdok.nl/rws/ahn/atom/dtm_05m.xml (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Federal Office of Topography Surveys Switzerland. swissALTI3D—Download. Available online: https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/de/hoehenmodell-swissalti3d#swissALTI3D—Download (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Department for Environment. Defra Survey Data Download. Available online: https://environment.data.gov.uk/survey (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Scottish Government. Scottish Remote Sensing Portal. Available online: https://remotesensingdata.gov.scot/data#/map (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- United States Geological Survey. TNM Download (v2.0). Available online: https://apps.nationalmap.gov/downloader/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Guth, P.L. prof-pguth-git_microdem. Available online: https://github.com/prof-pguth/git_microdem (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Zanaga, D.; Van De Kerchove, R.; Daems, D.; De Keersmaecker, W.; Brockmann, C.; Kirches, G.; Wevers, J.; Cartus, O.; Santoro, M.; Fritz, S.; et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2021 v200 (Version v200) [Data Set]. 2022. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7254221 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Buchhorn, M.; Smets, B.; Bertels, L.; Roo, B.D.; Lesiv, M.; Tsendbazar, N.E.; Herold, M.; Fritz, S. Copernicus Global Land Service: Land Cover 100 m: Collection 3: Epoch 2019: Globe. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/3939050 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Feciskanin, R.; Hajdúchová, V. New Tool for Calculating Land Surface Parameters. Zenodo. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15005370 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Feciskanin, R. Land Surface Parameters Calculator. Available online: https://github.com/xiceph/physical-geomorphometry-tools/tree/main/lsp-calculator (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Guth, P.L. MICRODEM: Open-Source GIS with a Focus on Geomorphometry. Available online: https://microdem.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Minár, J.; Evans, I.S.; Jenčo, M. A comprehensive system of definitions of land surface (topographic) curvatures, with implications for their application in geoscience modelling and prediction. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 211, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, P.L. DEMIX GIS Database (3.0). 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/13331458 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Guth, P.L. DEMIX GIS Database Version 2. 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/8062008 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Guth, P.L. DEMIX GIS Database Version 4 [Data Set]. 2025. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/17538186 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ho, Y.F.; Hengl, T.; Leandro, P. Ensemble Digital Terrain Model (EDTM) of the World (1.1) [Data Set]. 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/7676373 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ho, Y.F.; Hengl, T.; Parente, L. An Ensemble Digital Terrain Model of the World at 30 m Spatial Resolution (EDTM30) on Medium. Medium. 2023. Available online: https://medium.com/nerd-for-tech/an-ensemble-digital-terrain-model-of-the-world-at-30-m-spatial-resolution-edtm30-b4fcff38164c (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- AIRBUS Defence and Space. Copernicus DEM Product Handbook Version 5. Available online: https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/sites/default/files/media/files/2024-06/geo1988-copernicusdem-spe-002_producthandbook_i5.0.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Access to Copernicus Digital Elevation Model (DEM). Available online: https://explore.creodias.eu/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Precise Global Digital 3D Map “ALOS World 3D” Homepage. Available online: https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/ALOS/en/dataset/aw3d30/aw3d30_e.htm (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Tadono, T.; Nagai, H.; Ishida, H.; Oda, F.; Naito, S.; Minakawa, K.; Iwamoto, H. Generation of the 30 M-Mesh Global Digital Surface Model by ALOS PRISM. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, XLI-B4, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.; Hawker, L. FABDEM V1-2. 2023. Available online: https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/s5hqmjcdj8yo2ibzi9b4ew3sn (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Whitebox Software. Available online: https://www.whiteboxgeo.com/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Welcome to the SAGA Homepage. Available online: https://saga-gis.sourceforge.io/en/index.html (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Grohmann, C.H.; Smith, M.J.; Riccomini, C. Multiscale Analysis of Topographic Surface Roughness in the Midland Valley, Scotland. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 1200–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, R.; Shirasawa, M.; Pike, R.J. Visualizing topography by openness: A new application of image processing to digital elevation models. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2002, 68, 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Olaya, V. Chapter 6 Basic Land-Surface Parameters. In Developments in Soil Science; Hengl, T., Reuter, H.I., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 33, pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.P. Digital terrain modeling. Geomorphology 2012, 137, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minár, J.; Drăguţ, L.; Evans, I.S.; Feciskanin, R.; Gallay, M.; Jenčo, M.; Popov, A. Physical geomorphometry for elementary land surface segmentation and digital geomorphological mapping. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 248, 104631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, M.; Jones, S.; Reinke, K. Vertical accuracy assessment of freely available global DEMs (FABDEM, Copernicus DEM, NASADEM, AW3D30 and SRTM) in flood-prone environments. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2308734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisani, S.; Skrypitsyna, T.; Florinsky, I. Global digital elevation models for terrain morphology analysis in mountain environments: Insights on Copernicus GLO-30 and ALOS AW3D30 for a large Alpine area. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shary, P.A.; Sharaya, L.S.; Mitusov, A.V. Fundamental quantitative methods of land surface analysis. Geoderma 2002, 107, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, H.; Hengl, T.; Gessler, P.; Soille, P. Preparation of DEMs for geomorphometric analysis. Dev. Soil Sci. 2009, 33, 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florinsky, I.V. Computation of the third-order partial derivatives from a digital elevation model. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2009, 23, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, J.N.; Van Niel, K.P.; Boggs, G.S. How does modifying a DEM to reflect known hydrology affect subsequent terrain analysis? J. Hydrol. 2007, 332, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, M.; Reinke, K.; Jones, S. Explaining machine learning models trained to predict Copernicus DEM errors in different land cover environments. Artif. Intell. Geosci. 2025, 6, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS EROS Archive—Digital Elevation—Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 1 Arc-Second Global. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/science/usgs-eros-archive-digital-elevation-shuttle-radar-topography-mission-srtm-1-arc?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_object (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Rodriguez, E.; Morris, C.H.; Belz, J.E. A global assessment of the SRTM performance. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2006, 72, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, P.L. Geomorphometry from SRTM: Comparison to NED. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2006, 72, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M.; Crippen, R.; Fujisada, H. ASTER Global Digital Elevation Model (GDEM) and ASTER Global Water Body Dataset (ASTWBD). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA JPL. NASA SRTM-Only Height and Height Precision Global 1 Arc Second V001. Distributed by NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. 2020. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-nasadem-shhp-001 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Franks, S.; Rengarajan, R. Evaluation of Copernicus DEM and Comparison to the DEM Used for Landsat Collection-2 Processing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, E.; Olson, D.; Joshi, A.; Vynne, C.; Burgess, N.D.; Wikramanayake, E.; Hahn, N.; Palminteri, S.; Hedao, P.; Noss, R.; et al. An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience 2017, 67, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennelly, P.J.; Patterson, T.; Jenny, B.; Huffman, D.P.; Marston, B.E.; Bell, S.; Tait, A.M. Elevation models for reproducible evaluation of terrain representation. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 48, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennelly, P.J.; Patterson, T.; Jenny, B.; Huffman, D.P.; Marston, B.E.; Bell, S.; Tait, A.M. Elevation Models for Reproducible Evaluation of Terrain Representation—Archetypal Landforms [Data Set Version 2.0]. Dataset on Zenodo. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4323616 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kennelly, P.J.; Patterson, T.; Jenny, B.; Huffman, D.P.; Marston, B.E.; Bell, S.; Tait, A.M. Sample Elevation Models for Evaluating Terrain Representation. Available online: https://shadedrelief.com/SampleElevationModels/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Weary, D.; Doctor, D. Karst in the United States: A Digital Map Compilation and Database; Open-File Report 2014-1156; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distributed by Smithsonian Institution, Compiled by Venzke, E. Volcanoes of the World (Database v. 5.3.2; 30 Sep 2025). Available online: https://volcano.si.edu/gvp_votw.cfm (accessed on 12 November 2025).

| Country | Resolution (m) | Tile Geometry | Merged Tiles | Horizontal Datum | Vertical Datum (EPSG) | Tile Size (km) | Download |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canary Islands | 2 | Quarter MTN25 map sheet | 1 | ETRS89 UTM | 9397 | 16.9 × 10.0 | [29] |

| Denmark | 0.4 | UTM 1 × 1 km in 10 × 10 km zip | 100 | ETRS89 UTM | 5799 | 10 × 10 | [30] |

| Estonia | 1 | 5 × 5 km 1:10 K quarter map sheets | 4 | 3301 | 9663 (no GDAL support) | 10 × 10 | [31] |

| Finland | 2 | UTM 6 × 6 km TM35 map divisions | 4 | ETRS89 UTM | 3900 | 12 × 12 | [32] |

| Germany (by State) | 1 | UTM 1 × 1 km | 100 | ETRS89 UTM | 7837 | 10 × 10 | [33,34,35] |

| Mexico | 1.5 | Quarter 1:10 K map sheets | 4 | NAD83 UTM | 5703 | 10.6 × 14.0 | [36] |

| Netherlands | 0.5 | Quarter map sheet | 4 | EPSG 28992 | 5730 | 10.0 × 12.5 | [37] |

| Spain | 2 | Quarter MTN25 map sheet | 1 | ETRS89 UTM | 5782 | 14.7 × 9.7 | [29] |

| Switzerland | 2 | Swiss grid 1 × 1 km | 100 | EPSG 2056 | 5728 | 10 × 10 | [38] |

| UK (England, Scotland) | 1 | OSGB Quarter 10 km | 4 | EPSG 27700 | 5701 | 10 × 10 | [39,40] |

| USA | 1 | UTM 10 × 10 km | 1 | NAD83 UTM | 5703 | 10 × 10 | [41] |

| DEM | License | Pixel Geometry | Source Data | DTM Edit Methods | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CopDEM v2023-1 (DSM) | Free | SRTM | Radar | None (DSM) | [54,55] |

| AW3D30 v3.2 (DSM) | Free | ALOS | Optical | None (DSM) | [56,57] |

| FABDEM v1.2 (DSM) | Restrictive | SRTM | Radar | Random forest | [4,58] |

| Fathom v1 DTM | Restrictive | SRTM | Radar | Hybrid vision transformer model | [19,20,21] |

| GEDTM v1.2 | Free | SRTM | Radar | Two-stage random forest model | [5,22,23,24] |

| Criterion | Name | Units | Algorithm | Window | Program | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELEV | Elevation | Meter | Directly from test DEM | 0.0001 | ||

| HILL | Hillshade | 3 × 3 | MICRODEM | 0.005 | ||

| MHILL | Multidirectional hillshade | 3 × 3 | Whitebox | 0.005 | ||

| SLOPE | Slope | Percent | Evans | 3 × 3 | MICRODEM | 0.02 |

| SSTD | Spherical StdDev Of Normals | 5 × 5 | Whitebox | 0.01 | ||

| RUFF | Roughness | Percent | Std slope [61] | 5 × 5 | MICRODEM | 0.01 |

| TPI | Topographic position index | meter | 3 × 3 | MICRODEM | 0.01 | |

| HAND | Height above nearest drainage | Meter | Whitebox | 0.05 | ||

| OPENU | Upward Openness | Degree | [62] | 11 × 11 | MICRODEM | 0.005 |

| OPEND | Downward Openness | Degree | [62] | 11 × 11 | MICRODEM | 0.005 |

| TANGC | Tangential curvature | per meter | 3 × 3 | Whitebox | 0.0001 | |

| PROFC | Profile curvature | per meter | 3 × 3 | Whitebox | 0.0001 | |

| RRI | Radial roughness index | meter | 5 × 5 | MICRODEM | 0.015 | |

| CONIN | Convergence index | degrees | SAGA | 0.01 | ||

| PLANC | Plan curvature | per meter | 3 × 3 | Whitebox | 0.000025 |

| Criterion | Name | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| ELEV | Elevation | 0.0001 |

| Z_FIT | Fitted elevation | 0.0001 |

| ZX | First order derivative | 0.001 |

| ZY | First order derivative | 0.001 |

| ZXX | Second order derivative | 0.001 |

| ZXY | Second order mixed derivative | 0.001 |

| ZYY | Second order derivative | 0.001 |

| ZXXX | Third order derivative | 0.001 |

| ZXXY | Third order mixed derivative | 0.001 |

| ZXYY | Third order mixed derivative | 0.001 |

| ZYYY | Third order derivative | 0.001 |

| Criterion | Name | Partial Order | Units | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELEV | Elevation | 0 | m | 0.0001 |

| SLOPE | slope | 1 | Degree | 0.0001 |

| COS-A | cosine aspect | 1 | none | 0.0001 |

| SIN-A | sine aspect | 1 | none | 0.0001 |

| EL | Elevation Laplacian | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KMEAN | Mean curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KMIN | Minimal curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KMAX | Maximal curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KC | Casorati curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KU | Unsphericity curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| TS | Slope line torsion | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KNS | Normal slope line (profile) curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| ZSS | Second slope line derivative | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KNC | Normal contour (tangential) curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| ZCC | Second contour derivative | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KHE | Horizontal excess curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KVE | Vertical excess curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KD | Difference curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| K | Gaussian curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KA | Total accumulation curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| TC | Contour torsion | 2 | rad·m−1 | 0.0001 |

| SIN-SC | Contour change of sine slope | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KR | Total ring curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KNSS | Slope line change of normal slope line curvature | 3 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KNCS | Slope line change of normal contour curvature | 3 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KPC | Projected contour (plan) curvature | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KNCC | Contour change of normal contour curvature | 3 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

| KPS | Projected slope line curvature (rotor) | 2 | m−1 | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guth, P.L.; Trevisani, S.; Grohmann, C.H.; Lindsay, J.B.; Reuter, H.I. Benchmarking Elevation Plus Land Surface Parameters Finds FathomDEM and Copernicus DEM Win as Best Global DEMs. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233919

Guth PL, Trevisani S, Grohmann CH, Lindsay JB, Reuter HI. Benchmarking Elevation Plus Land Surface Parameters Finds FathomDEM and Copernicus DEM Win as Best Global DEMs. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233919

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuth, Peter L., Sebastiano Trevisani, Carlos H. Grohmann, John B. Lindsay, and Hannes I. Reuter. 2025. "Benchmarking Elevation Plus Land Surface Parameters Finds FathomDEM and Copernicus DEM Win as Best Global DEMs" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233919

APA StyleGuth, P. L., Trevisani, S., Grohmann, C. H., Lindsay, J. B., & Reuter, H. I. (2025). Benchmarking Elevation Plus Land Surface Parameters Finds FathomDEM and Copernicus DEM Win as Best Global DEMs. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3919. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233919