Highlights

What is the main finding?

- A three-branch model named HCTANet is proposed for remote sensing semantic change detection (SCD), which innovatively integrates three core modules: the multi-scale change mapping association (MCA) module (parallelly extracts and fuses multi-resolution dual-temporal difference features, and uses binary change detection (BCD) output to constrain semantic segmentation), the adaptive collaborative semantic attention (ACo-SA) mechanism (models cross-temporal feature semantic correlations via dynamic weight fusion and cross-window self-attention), and the spatial semantic residual aggregation (SSRA) module (fuses global context with high-resolution shallow features through residuals to restore pixel-level boundaries).

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The model effectively addresses key issues in remote sensing SCD, such as insufficient information interaction, single-scale feature limitations, and unbalanced long-range/local details, providing a reliable solution for accurate SCD in complex scenarios.

- HCTANet’s design ideas (multi-scale fusion, cross-temporal attention, residual aggregation) offer a reference for optimizing SCD models, and its performance on self-constructed AirFC dataset supports the expansion of SCD applications to professional fields (e.g., urban development, airport infrastructure dynamic monitoring).

Abstract

Semantic change detection has become a key technology for monitoring the evolution of land cover and land use categories at the semantic level. However, existing methods often lack effective information interaction and fail to capture changes at multiple granularities using single-scale features, resulting in inconsistent outcomes and frequent missed or false detections. To address these challenges, we propose a three-branch model HCTANet, which enhances spatial and semantic feature representations at each time stage and models semantic correlations and differences between multi-temporal images through three innovative modules. First, the multi-scale change mapping association module extracts and fuses multi-resolution dual-temporal difference features in parallel, explicitly constraining semantic segmentation results with the change area output. Second, an adaptive collaborative semantic attention mechanism is introduced, modeling the semantic correlations of dual-temporal features via dynamic weight fusion and cross-temporal cross-attention. Third, the spatial semantic residual aggregation module aggregates global context and high-resolution shallow features through residual connections to restore pixel-level boundary details. HCTANet is evaluated on the SECOND, SenseEarth 2020 and AirFC datasets, and the results show that it outperforms existing methods in metrics such as mIoU and SeK, demonstrating its superior capability and effectiveness in accurately detecting semantic changes in complex remote sensing scenarios.

1. Introduction

Land cover undergoes continuous and complex transformations under the combined influence of human activities and natural processes within the Earth system. Timely understanding and monitoring of land use and land cover (LULC) changes play a critical role in urban planning, dynamic resource and environmental monitoring, and disaster early warning [1,2]. Semantic change detection (SCD) has become an essential technique [3,4], aiming to track the evolution of land surface types at the semantic level by analyzing multi-temporal remote sensing imagery. Specifically, it enables the classification and delineation of diverse land cover changes before and after transformations. The results of SCD provide richer and refined interpretations of semantic changes. In recent years, with the increasing availability of high-resolution remote sensing images and the rapid advancement of computer vision models, SCD has been widely applied in various domains [5,6,7].

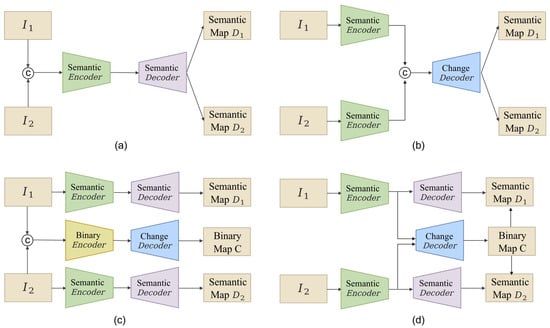

SCD primarily involves two tasks: identifying binary change information (change/no change) to locate change areas and performing the “from-to” transformation in dual-temporal remote sensing (RS) images to classify the type of change areas. With the development of SCD methods, four main architectures exist, as shown in Figure 1. In Figure 1a, the time 1 and 2 images are concatenated as input images. Early literature, such as using UNet++ [8], treats SCD as a semantic segmentation problem to obtain class maps for each region. However, in this structure, image information exploration is insufficient due to the concatenation of the two temporal images as input. Moreover, the encoder is applied to the entire image during segmentation, without focusing on the change areas. In Figure 1b, the dual-temporal images are processed through parallel semantic encoders in a Siamese structure to extract image feature information. The weights of the two encoders are shared, and the encoded features are fused through a change decoder to model the change areas. Although this method better reflects the features of the dual images compared to Figure 1a, it does not have binary change detection (BCD) results as guidance, and the change areas still do not receive enough attention. The method shown in Figure 1c combines both (a) and (b) methods, where the dual-temporal images and the concatenated images are used as inputs to the semantic and binary encoders, respectively. Semantic and change information are modeled in parallel, and after passing through the semantic and change decoders, semantic and binary maps for change areas are obtained. HRSCD-str. 3 [9] and the coarse-to-fine land use CD method [10] are typical methods of this structure. However, in this structure, semantic and change information are obtained in parallel, lacking interaction. It fails to fully utilize the LULC information in temporal features, thus limiting overall performance. In response to the issues with the above structures, Figure 1d structure is proposed. In this design, the semantic encoder of a Siamese framework extracts semantic features from paired images. The extracted semantic information is simultaneously input into both semantic and change decoders to obtain binary maps for change areas, guiding the change areas in the semantic map. Representative methods of this structure include Bi-SRNet [11] and ChangMask [12], both of which, based on parallel semantic feature extraction, incorporate binary change information to locate change areas. This approach combines explicit modeling of LULC information to enhance the richness of semantic information representation and strengthens the consistency of change representations in both semantic and spatial dimensions through change area information.

Figure 1.

Overview of the four mainstream SCD architectures. (a) Single-branch architecture; (b) Siamese single-branch architecture; (c) Dual-branch architecture; (d) Interactive dual-branch architecture.

Driven by advances in computer vision, remote sensing SCD has undergone a paradigm shift from dual-temporal independent prediction to semantic–spatial joint prediction. Evolving from early pixel-level difference discrimination using Siamese CNN encoders to the integration of key components such as Transformers and temporal attention, algorithmic performance has been steadily enhanced through temporal dependencies and attention mechanisms. Despite substantial progress, the practical application of SCD remains constrained by two major challenges. First, parallel predictions separate semantic segmentation and change detection, limiting information interaction. As a result, semantic segmentation (SS) outputs and binary change detection (BCD) maps cannot provide mutual guidance, leading to inconsistent SCD results. Second, single-scale features struggle to capture changes across multiple granularities, causing omissions or false alarms when both large-scale transformations and fine-grained facility changes appear within a scene. Moreover, high-resolution imagery presents complex spatial relationships among ground objects. Conventional CNN encoders, constrained by limited receptive fields, fail to capture long-range similarities or cross-scene semantic consistency. Although pure Transformer encoders offer global modeling capacity, they often overlook local details, making it difficult to balance long-range dependencies with fine-grained information.

Therefore, we propose HCTANet to enhance each temporal image’s spatial andcc semantic feature capabilities and model the semantic correlations and differences between different temporal images. The main contributions are as follows:

- Construct a three-branch end-to-end architecture, propose a multi-scale change mapping association module (MCA) to parallelly extract and fuse quadruple-resolution dual-temporal difference features, and explicitly constrain the SS branch with BCD output under shared encoder weights, achieving reverse calibration of semantic reasoning with the difference mask.

- Propose an adaptive collaborative semantic attention mechanism (ACo-SA), where the Dynamic Weight Fusion (DWF) module and cross-temporal cross-attention explicitly model the semantic correlation of dual-temporal features and suppress redundant feature differences. It uses cross-window self-attention to capture long-range semantic dependencies, achieving a global receptive field within just two layers while balancing computational efficiency and long-range dependency capture capabilities.

- Through the spatial semantic residual aggregation module (SSRA), aggregate global context with high-resolution shallow feature residuals, maintaining scene-level consistency while recovering pixel-level boundary details, ensuring segmentation accuracy at the detail level without losing spatial information.

2. Related Works

Remote sensing change detection aims to analyze multi-temporal remote sensing images to identify the state transitions of surface features in the spatiotemporal dimension. It is a core technology in monitoring the Earth’s surface system, urban planning, and ecological protection. The following sections will review the research progress and limitations of various methods.

2.1. End-to-End Change Detection

Early research on change detection adopted threshold-based analysis and statistical modeling as its core technical paradigm. For example, Ridd et al. [13] generated multiple sets of change maps using four algorithms, including image differencing and regression residuals, and derived optimal thresholds to quantify urban–suburban land cover changes. Bruzzone et al. [14] constructed a statistical distribution model based on difference images to distinguish between changed and unchanged pixels. However, such methods were constrained by their strong dependence on thresholds, leading to a gradual shift in research focus toward pixel-level spectral difference analysis. The unsupervised method based on binary hyperspectral change vectors proposed by Marinelli [15], and the local binary similarity pattern-based feature descriptor combined with Hamming distance developed by Gupta et al. [16], further advanced the technical development in this direction.

In order to further extract semantic features and reduce manual dependence, deep learning methods have been widely adopted [17,18,19]. Daudt et al. [20] first introduced Fully Convolutional Networks (FCN) into the CD task, proposing twin network structures such as FC-EF and FC-Siam-Diff, which significantly improved the accuracy of change region localization. Zhu et al. [21] leveraged neural networks’ global learning to process pixel-level samples, overcoming locality and imbalance issues of block-based methods. Fang et al. [22] addressed scene-level CD by combining VGG-16 features with pixel-level post-classification, enabling automatic sample generation without manual labels. Mou et al. [23] proposed Recurrent Convolutional Neural Networks (ReCNN), which combined CNN and RNN for the first time to learn spectral-spatial-temporal joint features in a unified framework, providing new ideas for dynamic modeling of multi-temporal imagery. Saha et al. [24] introduced DCVA, enabling unsupervised CD via pre-trained CNN features and hypervector comparison, but its variance-based selection struggles with subtle changes. To address the limited receptive field of CNN feature extraction, Chen et al. [25] proposed the Transformer-based BIT model, which uses self-attention mechanisms to capture global spatiotemporal dependencies. STFI [26] fuses convolutional and Transformer features with joint loss, improving bi-temporal CD accuracy. Recently, Zhang et al. [27] proposed CDMamba, integrating Mamba state space and convolution to balance local detail and global modeling with linear complexity, outperforming CNNs and Transformers on public datasets.

However, a vast receptive field limits the network’s detection accuracy for small change targets. More researchers have proposed multi-scale fusion approaches to extract deep semantic information while retaining shallow detail features [28,29,30]. Wang et al. [31] built a dual-stream DenseNet with attention fusion and deep supervision for multi-scale CD, though boundary discrimination remains limited. Fang et al. [32] improved CD by adding dense skip connections to retain high-resolution features and aggregating multi-semantic cues to reduce localization errors. Many researchers have combined CNN for hierarchical feature extraction and Transformer modules for aggregating multi-scale context [33,34], balancing localization and semantics to achieve efficient and precise change detection. Deep learning methods continue to improve accuracy and robustness through multi-scale, attention, and cross-domain difference modeling [9,35], providing rich and complementary solutions for change detection tasks.

2.2. Semantic Change Detection

Semantic change detection requires the model to output both land cover categories and change states, demanding fine-grained semantic understanding and spatiotemporal relationship modeling capabilities. This is a current research hotspot and challenge [36,37]. Semantic change detection achieves this by jointly modeling spectral-temporal features and semantic categories, with typical strategies including the integration of standard classification methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) [38] and improved Change Vector Analysis (CVA) [39]. For instance, He et al. [40] introduced “spatial neighborhood interference elimination” and an adaptive weighted Gaussian mixture model (CVA-AWGMM) into the CVA framework, enabling multi-class change detection with only dozens of labeled samples while reducing threshold dependence. Chen et al. [41] proposed an adaptive-weight CVA, which optimized performance by extracting regional directions and adaptively weighting object variability. Nevertheless, traditional single amplitude-direction features have limitations in distinguishing semantic categories, often requiring the introduction of additional features or post-processing steps for secondary optimization, and the final detection accuracy still fails to meet the practical requirements of complex scenarios [42,43,44].

With the advancement of deep learning, Siamese architectures based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have progressively emerged as the mainstream paradigm: FC-Siam-Conc and FC-Siam-Diff exploit bi-temporal feature discrepancies to achieve end-to-end detection [45]. Subsequently, researchers incorporated multi-scale convolution, attention mechanisms, and residual connections to enhance the representational capacity of the models. The Spatially and Semantically Enhanced Siamese Network (SSESN) achieves joint optimization of binary and semantic detection tasks through the Spatial and Semantic Feature Aggregation (SSFA) module and the Change-Aware (CA) module [46]. STSP-Net introduces a detail-aware pathway and a spatio-temporal attention module within a Siamese multi-task framework, thereby enhancing the detection of small objects and boundary delineation [4]. Furthermore, the Dual-Dimension Feature Interaction Network (DFINet) achieves deep integration of cross-temporal and cross-level features via Temporal Difference Feature Enhancement (TDFE) and an interactive attention mechanism, substantially mitigating the impact of pseudo-change interference [47]. Moreover, MTSCD-Net leverages multi-task learning to decouple semantic segmentation and binary detection into interrelated sub-tasks, while enhancing cross-temporal feature representation through a Swin Transformer encoder [45].

However, its high computational complexity and data dependence limit its practical application. The Transformer architecture provides new tools for modeling long-range spatiotemporal relationships [48]. Yuan et al. [35] proposed Pyramid-SCDFormer, which captures cross-pixel spatiotemporal dependencies based on the self-attention mechanism of Transformer, significantly improving the recognition accuracy of small changes and edge details. Multi-task collaborative learning has become an important paradigm for SCD [9]. Zheng et al. [49] proposed the ChangeOS framework, which integrates deep learning with object-based image analysis (OBIA), extracting task-independent features through twin networks and combining object-level voting mechanisms to ensure semantic consistency of buildings. It effectively addresses partial damage recognition issues in pixel-level models, but performs poorly in complex scenarios such as cloud cover. Multi-scale feature extraction is also applied to SCD to improve accuracy. Fang et al. [50] decomposed SCD into binary change detection and dual semantic segmentation sub-tasks, constructing a multi-task learning framework based on HRNet. By combining bidirectional feature fusion, they enhance semantic information transmission, but the model’s many parameters require significant storage and computational resources.

The asymmetric network design has gained attention for addressing the temporal differences in multi-temporal imagery. Yang et al. [10] proposed an Asymmetric Siamese Network (ASN), which extracts differentiated feature pairs through the Asymmetric Spatial Pyramid (aSP) and Representation Pyramid (aRP) modules, combined with Adaptive Threshold Learning (ATL) to alleviate label imbalance. This significantly improves the detection robustness in scenarios with significant land cover distribution differences. However, its complex module structure increases the difficulty of training and fine-tuning. The ClearSCD model proposed by Tang et al. [51] optimizes the intra-class consistency and inter-class separability of semantic features through Semantic-Enhanced Contrastive Learning (SACL) and Dual-Temporal Semantic Correlation Capture (BSCC) mechanisms. However, there is still a contradiction between semantics and change results during the decision-making stage.

2.3. Paradigm Shift and Core Challenges in SCD

Change detection research is shifting from “whether” to “from–to”. Traditional feature-threshold methods rely on manual rules, making it difficult to balance high-dimensional semantics and fine-grained spatiotemporal differences. Deep learning methods, through end-to-end networks, automatically learn multi-level representations and integrate CNN’s local modeling with Transformer’s global dependencies, not only achieving significant accuracy improvements in pixel-level/category-level change detection but also enhancing change localization and semantic recognition precision through attention, multi-tasking, and cross-domain difference enhancement. However, it is also crucial to model the semantic correlation and differences between dual-temporal images, which has become an urgent task in the current direction of SCD. Unlike previous works that focus primarily on dual-branch feature concatenation or pixel-level difference learning [12,52], our HCTANet introduces explicit multi-scale change mapping association and adaptive cross-temporal attention, enabling finer semantic interaction across temporal stages.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Network Architecture

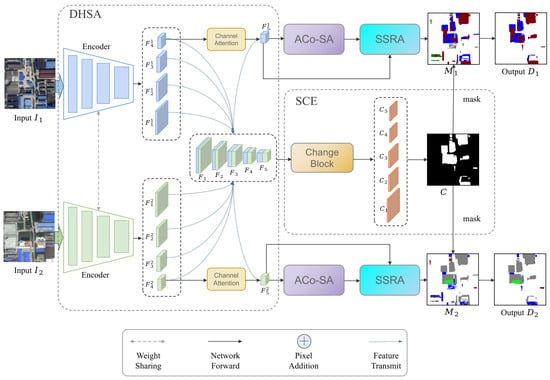

This model integrates SS and BCD into a three-branch architecture to achieve end-to-end SCD, as shown in Figure 2. For dual-temporal images, it is important not only to consider the spatial and semantic features of each temporal image, but also to model the semantic correlation and differences between the different temporal images. To this end, the proposed HCTANet employs three closely coupled modules that collaboratively enhance multi-level feature interaction and semantic consistency. Specifically, the MCA module first aligns and fuses multi-resolution dual-temporal features to emphasize potential change regions and provide coarse change priors. These priors are then transmitted to the ACo-SA module, which leverages cross-temporal attention to refine semantic relationships based on the guidance of MCA, enhancing the discrimination of category-level changes. Subsequently, the SSRA module further integrates the context-enhanced semantic features from ACo-SA with fine-grained spatial cues, enabling accurate restoration of object boundaries and spatial consistency in the decoded maps. Through this progressive and mutually reinforcing interaction, MCA supplies scale-aware difference cues, ACo-SA strengthens semantic coherence, and SSRA restores spatial precision—forming a unified learning process that jointly drives HCTANet toward more consistent and interpretable semantic change detection results.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the proposed Multi-Scale Residual Fusion Meets Cross-Temporal Attention (HCTANet) for Remote Sensing SCD.

Given two input images and from different temporal phases, the improved ResNet structure of the Siamese architecture is used as the main encoder and , performing multi-level feature extraction with shared weights on the dual-temporal images, obtaining features , , , at different scales and their attention features , where . Projected in the MCA module onto different scale binary change maps , , , and , and after feature scale alignment, the fusion results in the BCD output C for the input images, as shown in Equation (1), U representing the upsampling and concatenation fusion operation.

Meanwhile, the attention features from both temporal phases continue to propagate downward, and are projected onto the corresponding semantic feature maps , in ACo-SA , as follows:

The obtained semantic feature maps are fused in SSRA in the form of residuals, combining spatial features , and semantic features , , resulting in the final single-temporal feature map , .

The final generated single-temporal features are projected into two semantic maps and using two classifiers. Next, the BCD results C from the dual-temporal images guide and and generate the semantic change detection results and , as shown in Equation (4), where represents the upsampling scale alignment operation.

3.2. Multi-Scale Change Mapping Association Module

Semantic correlation has been shown to be beneficial for SCD results in multiple studies. More accurate BCD results are used in the three-branch SCD to reflect the semantic correlation between dual-temporal RS images [52,53,54]. In HCTANet, semantic correlation and differences are learned in the proposed MCA. The MCA consists of two components, DHSA and SCE, where the DHSA enhances semantic representation through multi-scale feature fusion, and the SCE extracts discriminative change information from precise semantic cues.

3.2.1. Dual-Temporal Hierarchical Semantic Alignment Module (DHSA)

In order to generate accurate change detection maps, exploring the rich semantic information and precise spatial details in dual-temporal images is essential. Numerous studies have attempted techniques such as multi-scale feature aggregation [37,55,56] and attention mechanisms [57,58,59]. Inspired by these advanced technologies, we combine features at different levels that contain information at various granularities, and integrate attention mechanisms to combine coarse-grained semantic information. By fusing multi-scale features, we improve the accuracy of change detection.

The process starts with the improved ResNet encoder, using the Siamese framework to perform multi-level feature extraction with shared weights from dual-temporal images, as shown in Figure 2, where the multi-level features obtained from the four different stages of ResNet are designated as , , , , these features are then propagated backward through a channel attention module for sorting, set input as , then the mapping of features can be obtained through convolution and transformation, as shown in Equation (5).

where represents the reshape operation, and represents the reordering of tensor dimensions, c represents the number of channels of the current feature, , and represent the width and height of the feature, respectively. The decomposed feature maps follows Equation (6) for channel enhancement, resulting in the output .

where, denotes the softmax operation.

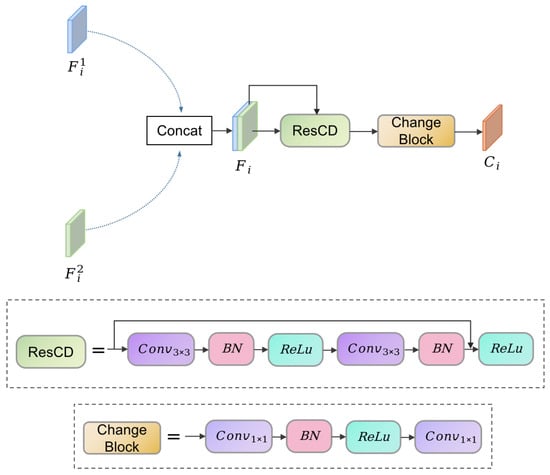

3.2.2. Siamese Change Enhancement Encoder (SCE)

Binary change information can redefine and refine semantic information, playing an important role in modeling temporal correlation between dual-temporal RS images. In the LULC task, the change areas include the location and type of changes, and information such as the scale and extent of the changes. We fully utilize the multi-scale features obtained in the DHSA module and propose the SCE, which is capable of extracting change features at different scales, providing richer information for temporal correlation analysis, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

SCE structure diagram.

Specifically, as shown in Figure 2, the multi-scale features , , , , obtained from the encoder , contain spatial and semantic information from deep to shallow. Images at the same scale from different temporal phases are combined and input into the ChangeBlock, temporal alignment operations are used to construct feature correspondences across the temporal dimension. For simplicity, we use i to represent different scales, .

In the same formula, i represents only one scale, and no cross-operation is performed between scales. The features combined at the same scale are further mapped to ensure spatiotemporal consistency of the semantic information in the multi-resolution feature space under different temporal phases within the ChangeBlock,

At this point, ResCD is composed of one set of downsampling and 6 sets of ResBlocks, which is specifically described by Equation (9), all scales follow the same operations.

After spatiotemporal alignment and sorting of multi-scale features from different temporal phases, each scale feature retains the spatial structural details of the original data while also containing rich temporal correlation information.

Decode to obtain the Changemap for each scale, labeled as . First, the input features undergo semantic compression along the channel dimension and preliminary spatial feature recovery through the first convolutional layer, the non-linear activation function enhances the representation ability of the features, then, the second convolutional layer further completes the feature detail reconstruction and classification mapping.

Using the feature map size output by the first-stage feature extraction module as the spatial reference, bilinear interpolation is used to resample the Changemaps generated by decoders at different levels to the target resolution, to achieve refined fusion of change detection results, resulting in the BCD result C, providing a foundation for dual-temporal semantic change analysis with both spatial details and temporal correlation.

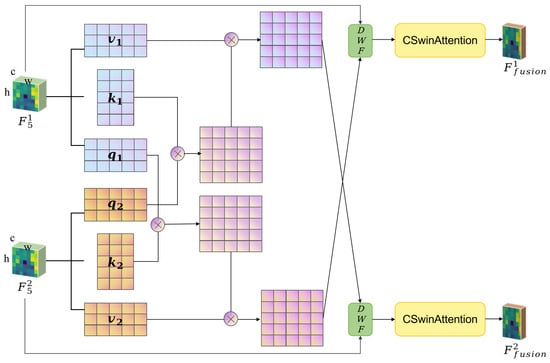

3.3. Adaptive Collaborative Semantic Attention Mechanism

The feature relationships between dual-temporal images are entirely associated with facilitating the information interaction between features of different temporal phases, especially when dealing with multi-temporal, multi-scale features with complementary semantics. After feature extraction, an adaptive collaborative semantic attention mechanism is proposed, as shown in Figure 4. The ACo-SA module focuses on modeling cross-temporal feature interaction through adaptive collaborative attention.

Figure 4.

ACo-SA structure diagram.

In the aforementioned dual-temporal layered semantic alignment module encoder, the features are organized and obtained , , where they are mapped into two sets of vectors , , and , , , cross operations are performed between the vectors as shown in Equation (12).

where, represents the softmax operation, This cross-operation design enables the two feature maps to guide each other’s attention allocation, capturing richer dual-temporal semantic correlations.

Next, DWF is used to merge it with the original features, and two trainable weight parameters , are applied with an initial value of 0, as shown in Equation (13), allowing the model to adaptively allocate the weight of semantic-related features.

Finally, to better model the long-range dependencies in the image with the fused features, the fused features , are introduced with the cross-window self-attention mechanism (CSwinAttention) [60], taking advantage of the global modeling capability of the Transformer to capture the movement of objects and the relationship with the surrounding environment in the scene. Specifically, the feature map is divided into horizontal and vertical windows, For multi-head attention computation with attention heads, attention heads are used for the horizontal self-attention calculation of the horizontal window, while attention heads are used for the vertical self-attention calculation of the vertical window, and they are executed separately:

Unlike traditional full-window self-attention, this strategy can obtain a global receptive field with just two layers, significantly enhancing the feature’s ability to model long-range dependencies, while also reducing the computational cost.

3.4. Spatial Semantic Residual Aggregation Module

In remote sensing images, complex ground landscapes and different imaging conditions can cause a reduction in image clarity, leading to incomplete segmentation edges, requiring features to retain semantic information to distinguish between foreground and background, while not losing spatial information, ensuring the accuracy of segmentation details. We propose a residual approach to directly fuse the abstract semantic features extracted from deep layers with the raw features from shallow layers, enhancing feature expression capability, allowing the model to capture local details while grasping global semantics, improving task performance in complex scenes, while also avoiding gradient vanishing and accelerating training.

In the previous section, we obtained features and with dual temporal associations and rich long-range semantics, which are fused with the original features and obtained from the encoder , through an element-wise addition operation, achieving complementary enhancement between the original features and transformed features. Specifically, the fusion process can be represented by Equation (16):

where, ⊕ represents the pixel-wise addition calculation, resulting in the final feature map for each time phase. To introduce non-linear transformation and enhance feature discriminability, the fused features are further passed through the ReLU activation function, ensuring the model’s expressive capability.

3.5. Loss Function Design

In semantic change detection tasks, relying on a single loss function often fails to simultaneously ensure high semantic classification accuracy and effective constraints on change regions. To address this issue, this study employs a combination of multiple loss functions, including semantic segmentation loss, binary change detection loss, and change-region feature similarity loss. The overall loss function can be formulated as:

where denotes the image semantic segmentation loss in the first phase, denotes the image semantic segmentation loss in the second phase, represents the binary change detection loss, and corresponds to the change-region feature similarity loss.

To quantitatively evaluate model performance in multi-class semantic segmentation, we adopt the multi-class IoU (MIoU) as a loss function. Let the model’s predicted tensor be and the ground truth labels be . The predicted outputs are first passed through a softmax function to obtain pixel-wise probability distributions, while the ground truth labels are converted to one-hot encodings. The IoU loss for each class is defined as:

where and T denote the predicted probability and the one-hot encoded ground truth, respectively, and is a smoothing term to prevent division by zero. The final IoU loss is given by:

The binary change detection branch, , predicts the differences between paired images, producing a binary mask with ground truth M. A weighted binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss is used:

where balances the contribution of positive and negative samples, N denotes the number of pixels.

In regions without changes, the semantic segmentation predictions of the two time phases are expected to remain consistent. To enforce this, a feature similarity constraint is introduced:

where denotes the unchanged regions, n denotes the current pixel, and and are the predictions of the two time phases, respectively. This loss encourages the model to maintain consistent semantic representations in unchanged areas.

4. Experiment Settings and Result Analysis

4.1. Datasets Description and Experimental Settings

4.1.1. Datasets

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the HCTANet model, we first conducted experiments on the SCD benchmark dataset SECOND. In addition, to better align with real-world applications, we constructed a large-scale airport facility change dataset named Airport Facility Change (AirFC), which increases the difficulty of experimental analysis by focusing on fine-grained changes within airports. Furthermore, we included the SenseEarth 2020 dataset, a large-scale benchmark for remote sensing interpretation, to further validate the generalization capability of our method under diverse and complex change scenarios. The detailed settings of these three datasets are introduced below.

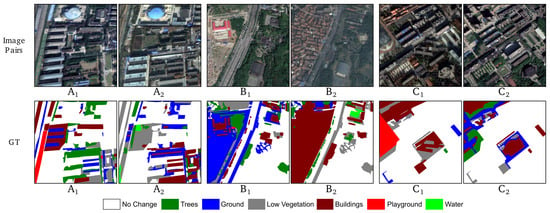

SECOND: The SECOND dataset [10], as shown in Figure 5, includes 4662 pairs of dual-temporal images, of which 2968 pairs are publicly available, collected from multi-platform sensors, including satellite and aerial images, covering typical urban areas in China, such as Hangzhou, Chengdu, and Shanghai. It mainly reflects the temporal span of urban development, with image resolution ranging from 0.5 to 3 m per pixel, and the spatial size is unified at 512 × 512 pixels. The dataset includes six land cover categories: no-change, non-vegetated ground surface, tree, low vegetation, water, buildings, and playgrounds, with pixel-level annotations that accurately depict the spatiotemporal migration of ground objects. We divided the dataset into training, validation, and testing sets in a 7:2:1 ratio during the experiment.

Figure 5.

Schematic visualization of the SECOND dataset. , and represent three distinct image pairs, along with their corresponding GT detail information.

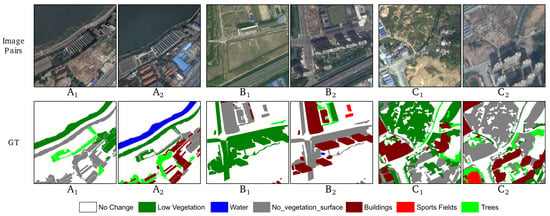

SenseEarth 2020: The SenseEarth 2020 dataset [61] is part of the SenseTime SenseEarth AI Remote Sensing Interpretation competition. As shown in Figure 6, this dataset consists of high-resolution multi-temporal optical satellite images covering diverse urban, suburban, and rural scenes in China, with a spatial resolution of 0.8–2 m. Pixel-level annotations are provided for multiple land-cover classes, including built-up areas, vegetation, roads, bare land, and water bodies. The dataset contains about 2968 training images pairs and supports semantic segmentation and semantic change detection tasks. Its large scale, fine-grained labels, and diverse landscapes make it a challenging benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness and generalization of deep learning-based remote sensing interpretation methods.

Figure 6.

Schematic visualization of the SenseEarth 2020 dataset. , and represent three distinct image pairs, along with their corresponding GT detail information.

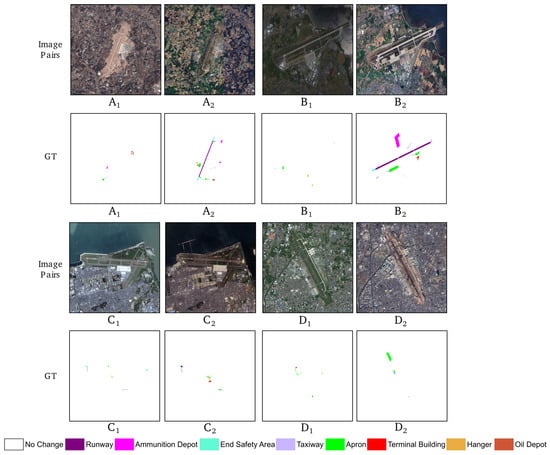

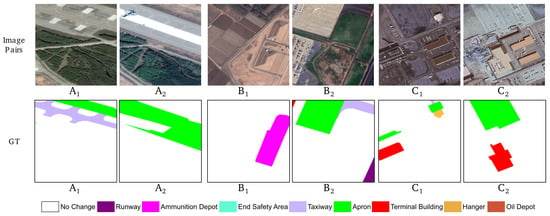

AirFC: The AirFC is a multi-source remote sensing dataset aimed at dynamic monitoring of airport infrastructure, as shown in Figure 7, and aims to provide a standardized research platform for change detection tasks such as airport expansion and runway maintenance. The dataset includes a total of 350 pairs of dual-temporal images; the images are collected from multi-platform sensors such as GF1, GF2, GF6, and Google, covering typical regions in China, Japan, the United States, and other countries, and fully document the evolution of airport facilities during the peak period of civil aviation development, with image resolution ranging from 0.45 to 2 m per pixel, and sub-pixel level alignment ensures spatial consistency across multi-temporal data. The dataset is annotated at the pixel level and divided into 15 categories: runway, taxiway, connector, apron, hangar, fuel depot, aircraft shelter, others, and unchanged areas. Considering network training efficiency and consistency, the entire airport image is slid and cropped to a spatial size of 512 × 512 pixels for neural network training and inference. The cropped images remove the non-target all-black image pairs to form the dataset, which consists of 1540 image pairs. Figure 8 presents the visualization of the cropped detailed information.

Figure 7.

Schematic visualization of the AirFC dataset. , , , and denote four different image pairs, each accompanied by its corresponding ground truth (GT). The GT refers to a pixel-level annotation obtained manually, providing accurate reference for evaluation.

Figure 8.

Schematic visualization of the details of the AirFC dataset. , and represent three distinct image pairs, along with their corresponding GT detail information.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

For the task of SCD, we evaluate our model’s effectiveness using the following metrics: Overall Accuracy(OA), Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) and Separated Kappa (SeK).

Overall Accuracy (OA) is often used as an evaluation standard for remote sensing image semantic segmentation and change detection, to measure the overall classification accuracy of the model across all class samples. Its calculation formula is based on the Confusion Matrix, Let the confusion matrix be Q, where represents the number of samples with true class i predicted as class j. Then:

where n is the total number of categories, and N is the total number of samples, the numerator represents the number of correctly classified samples, which is represented by the sum of the diagonal elements in the confusion matrix. Since OA assigns equal weight to each pixel in the calculation, when unchanged pixels dominate the dataset, this metric may introduce evaluation bias due to the high proportion of the majority class.

We introduce mIoU to evaluate the segmentation of changed and unchanged areas. The calculation formula is as follows:

where TP, FN, FP, and TN symbolize the respective counts of true positives, false negatives, false positives, and true negatives in terms of pixels. represents the unchanged area of mIoU, and represents the changed area of mIoU.

When unchanged areas occupy a large number of pixels, the SeK metric corrects for this through expected consistency, preventing the dominant pixel categories from overly influencing the metric. The specific calculation is shown in Equation (25) below:

where, represents the total number of pixels with the true class i, and represents the total number of pixels predicted as class i.

4.1.3. Experiment Setup

All experiments were implemented in PyTorch (version 1.12.0) and conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB). The proposed model was trained using the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4, which was reduced by a factor of 0.1 upon stagnation of validation performance. The batch size was fixed at 2, and the training proceeded for 100 epochs.

To assess the sensitivity of the model to hyperparameters, we conducted additional experiments by varying the learning rate, batch size, and optimizer. The results demonstrate that the model maintains stable performance when the learning rate is varied within the range of to , with the best accuracy consistently observed at . Increasing the batch size beyond 8 led to a slight decline in accuracy due to gradient instability under memory constraints, while excessively small batch sizes (≤2) resulted in slower convergence. Furthermore, the AdamW optimizer yielded faster and more robust convergence compared with SGD, particularly during the early stages of training when gradients were noisy. These observations indicate that the proposed framework is relatively insensitive to hyperparameter variations, although careful tuning of the learning rate and batch size remains critical for achieving optimal performance.

4.2. Comparative Experiments

4.2.1. Quantitative Analysis

To verify the proposed algorithm’s performance in remote sensing change detection tasks, we benchmarked it against several advanced algorithms on the SECOND, Senseearth 2020 and AirFC datasets. The algorithms involved in the comparison include FC-EF [20], UNet++ [8], SSESN [46], FC-Siam-diff [20], SCDNet [58], HRSCD-str.4 [9], SSCD-l [11], Bi-SRNet [11], TED [62], SCanNet [62], ChangeMamba [63] and SCNet [64]. Among them FC-EF and FC-Siam-diff were originally designed for binary change detection. To adapt them for semantic change detection, we replaced their binary classification heads with multi-class segmentation heads and adjusted the loss function accordingly to support multiple semantic categories. Additionally, we ensured that the training labels correspond to semantic-level changes rather than simple change masks. These modifications allow the models to perform semantic change detection while maintaining their original architectures. These algorithms cover various network architectures and design concepts, providing a comprehensive and challenging comparison for evaluating our algorithm.

The results are shown in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, proving the superior performance of our method on the public SECOND, senseearth2020 and AirFC datasets. Notably, compared to the current leading methods, the proposed algorithm, HCTANet, performs excellently in mIoU, Sek, and OA metrics. HCTANet consistently achieves the highest mIoU across all datasets, reaching 74.08% on SECOND, 53.27% on AirFC, and 77.29% on SenseEarth 2020. Compared with the baseline Bi-SRNet, the improvements are 1.15%, 0.89%, and 1.08%, respectively, indicating the stronger semantic segmentation capability of the proposed model. The reason is that our proposed spatial semantic residual aggregation module integrates the abstract semantic features extracted by deep networks with the raw features obtained by shallow networks, which provides global semantic understanding for the SS task while incorporating rich local detail information, enhancing the feature representation ability and the overall performance of the model.

Table 1.

Comparison of proposed methods with existing methods in the literature for SECOND dataset.

Table 2.

Comparison of proposed methods with existing methods in the literature for AirFC dataset.

Table 3.

Comparison of proposed methods with existing methods in the literature for Senseearth 2020 dataset.

In terms of SeK, HCTANet also outperforms other methods, achieving 25.14%, 12.95%, and 29.04% on the three datasets. The improvements over Bi-SRNet are 2.44%, 0.22%, and 1.67%, respectively, showing the model’s advantage in accurately capturing semantic changes and reducing false detections. HCTANet can more accurately identify change regions in change detection tasks, ignoring the unchanged background regions, which reduces false positives and false negatives in the target regions. The main reasons are analyzed as follows: On the ond hand, our proposed dual-temporal correlation mapping module fully considers the differences in information granularity contained in features of different levels, enhancing the richness and accuracy of feature representation, thereby significantly improving the accuracy of binary change detection.

Additionally, the OA values for HCTANet obtains 88.45% on SECOND, 95.97% on AirFC, and 89.95% on SenseEarth 2020. Although the OA on SECOND is slightly lower than Bi-SRNet due to the dataset’s large proportion of unchanged regions, our method still achieves competitive results, and it consistently outperforms existing approaches on AirFC and SenseEarth 2020. Considering that evaluation metrics OA can be biased due to the high proportion of the majority class, the SECOND dataset has a larger proportion of unchanged regions compared to the AirFC dataset, resulting in instability in the OA, causing the proposed model’s result on the SECOND dataset to be slightly lower than that of Bi-SRNet, but it still outperforms other algorithms on the AirFC dataset and Senseearth dataset, reflecting the good performance of the algorithm in the overall classification task. Moreover, through the Params in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, it can be analyzed that our algorithm does not increase the number of parameters while improving accuracy. FLOPs shows that compared with the baseline algorithm Bi-SRNet, our algorithm has achieved a slight improvement in speed.

4.2.2. Qualitative Analysis

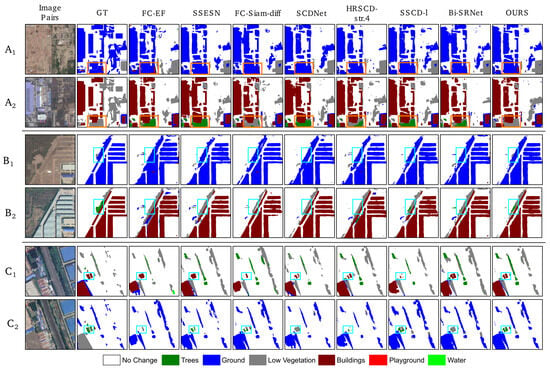

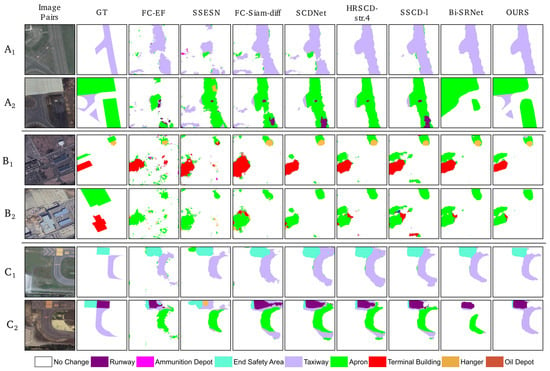

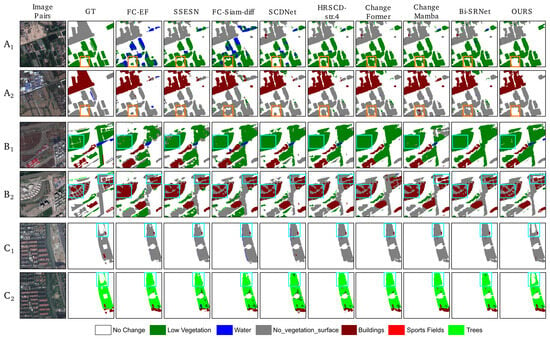

Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrates the qualitative results of HCTANet compared with several baseline methods on the SECOND, AirFC and Senseearth2020 datasets. Among them, the light blue box indicates the detail advantage at the edge, and the orange box indicates the correctness of the category distinction.

Figure 9.

Visualization results on the SECOND dataset for HCTANet and comparison methods. , , represent three different pairs of images.

Figure 10.

Visualization results on the AirFC dataset for HCTANet and comparison methods. , , represent three different pairs of images.

Figure 11.

Visualization results on the Senseearth 2020 dataset for HCTANet and comparison methods. , , represent three different pairs of images.

As highlighted in the light blue box in Figure 9, our algorithm can detect details that other algorithms fail to identify, outperforming other comparison methods in detail and edge processing. On the other hand, addressing the inherent complementary semantic characteristics of multi-temporal data, this study proposes an adaptive collaborative semantic attention mechanism, enabling the model to dynamically integrate semantic information from different temporal phases, strengthening the consistency of dual-temporal feature representation. As indicated in the orange box in Figure 9, our algorithm achieves more accurate results in category classification.

Our method produces more accurate and detailed semantic change maps, especially in complex regions with small or irregularly shaped changes. HCTANet demonstrates superior boundary preservation and effectively distinguishes subtle changes that are often missed by other methods, such as FC-Siam-diff and Bi-SRNet. In addition, the model shows strong robustness in suppressing false positives in unchanged areas, resulting in cleaner change detection maps. These qualitative results, together with the quantitative metrics, validate that HCTANet can accurately capture semantic changes across diverse scenarios while maintaining high visual fidelity.

4.3. Ablation Experiments

In order to assess the individual contributions of our components, we conduct comprehensive ablation experiments on the SECOND and AirFC datasets, and Table 4 shows the ablation results, ✓ represents the module used in the current experiment. We conducted individual and integrated effect analysis of each innovative component, and the effect reached its best when all three components were used together.

Table 4.

Ablation analysis for the proposed components on the SECOND and AirFC datasets.

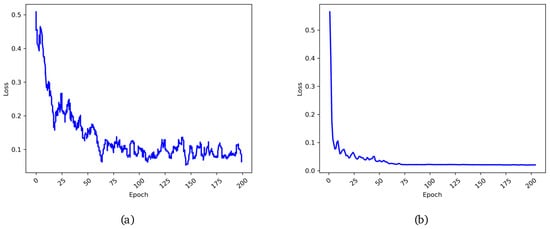

Table 4 reflects the effects of the innovative components we proposed when used individually and in combination. The bolded results indicate the best ones in the comparative experiments. From the table analysis, it is clear that, based on the baseline model, the model performance gradually improved by incrementally adding MCA, ACo-SA, and SSRA. The model performance was progressively enhanced. Furthermore, Figure 12 shows the training and validation curves, indicating stable convergence without overfitting.

Figure 12.

The curves of the loss function as epochs increase during training and validation. (a). The relationship between the number of iterations and the loss value during the training process; (b). The relationship between the number of iterations and the loss value during the verification process.

Specifically, compared to the baseline model, when using only the multi-scale fusion binary change detection module, the model’s mIoU, Sek, and OA on the SECOND dataset improved by 0.41%, 1.18%, and 0.27%, respectively, and on the AirFC dataset, mIoU, Sek, and OA improved by 0.19%, 0.3%, and 0.05%, respectively. From Figure 9, it can be observed that in the baseline method results, many detailed areas were neglected. Under the support of the MCA module, the detailed areas were more detected and processed, further proving that our MCA module can effectively capture change features at different scales, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize change regions. In addition, when the MCA module is employed in conjunction with the ACo-SA module and the SSRA module simultaneously, the accuracy experiences another upward trend. Specifically, ACo-SA compensates for the deficiency in the semantic relevance of the MCA module between the two temporal phases. The integrated utilization of these components leads to a substantial enhancement in accuracy.

We conducted ablation experiments to evaluate the contributions of the three proposed modules. The ACo-SA module provides more substantial gains, the model shows modest improvements, with the mIoU increasing by 0.7% on the SECOND dataset and 0.46% on the AirFC dataset, indicating that it facilitates cross-temporal feature interaction and enhances semantic correlation modeling. When only SSRA is employed, with mIoU improving by 0.24% on SECOND and 0.32% on AirFC, reflecting its effectiveness in integrating deep semantic features with shallow spatial details and improving both local boundary precision and global context understanding. Using MCA together with ACo-SA further boosts performance, increasing mIoU by 1.28% on SECOND, which demonstrates that multi-scale change modeling and semantic attention complement each other. Finally, incorporating all three modules achieves the highest performance, reaching 74.08% mIoU on SECOND and 53.27% on AirFC, confirming that their synergistic interaction fully exploits multi-scale representation, semantic correlation, and spatial–semantic aggregation. These results highlight not only the individual importance of each module but also the benefit of their coordinated design in enhancing semantic change detection.

5. Discussion

This study proposes HCTANet, a three-branch architecture integrating multi-scale residual fusion and cross-temporal attention for remote sensing SCD. The discussion below elaborates on the model’s performance characteristics, technical contributions, inherent limitations, and future research directions, contextualized within the broader SCD research landscape.

Performance characteristics: HCTANet achieves state-of-the-art performance on multiple benchmark datasets, demonstrating robust adaptability and generalization across diverse scenarios. Its superior accuracy stems from the synergistic design of its core modules: the MCA module captures multi-scale change features, the ACo-SA mechanism enhances cross-temporal semantic correlations, and the SSRA module refines boundary details, effectively balancing global context and local precision. The model excels at detecting subtle, fine-grained changes while maintaining computational efficiency, with 23.36 M parameters and 189.8 G FLOPs, outperforming comparable methods such as SCNet and ChangeMamba both in accuracy and efficiency. This combination of precise feature modeling, semantic interaction, and lightweight design makes HCTANet suitable for real-world change detection applications.

Technical contributions: HCTANet advances semantic change detection through three key contributions. First, it unifies BCD and SS in a three-branch framework, where BCD outputs reverse-calibrated semantic inference via the MCA module. This overcomes the typical limitation of parallel SCD architectures, where semantic and change cues lack mutual guidance; ablation shows that MCA alone improves mIoU by 0.41% on SECOND. Second, the ACo-SA mechanism enhances cross-temporal feature modeling through dynamic weight fusion and cross-window self-attention, adaptively emphasizing relevant features and efficiently capturing long-range dependencies, thereby improving semantic consistency and reducing pseudo-changes. Third, the SSRA module reconciles deep semantic abstraction with shallow spatial detail preservation via residual feature fusion, retaining pixel-level boundaries while maintaining global context, as reflected in clearer delineation of change regions compared to Bi-SRNet and SCanNet.

Inherent limitations: While HCTANet achieves competitive accuracy, it has several limitations. First, it retains more parameters than lightweight architectures such as FC-EF, primarily due to the MCA module’s parallel processing of dual-temporal features across five scales, which incurs substantial memory consumption during feature extraction and fusion. Second, the model relies solely on optical remote sensing images, limiting its robustness under challenging imaging conditions such as cloud cover, shadows, or multi-modal data. Third, it is designed for bi-temporal change detection and does not directly handle dynamic multi-temporal changes, such as seasonal vegetation variations or phased construction.

Future research directions: Future research will address these limitations along three directions. First, lightweight design: replacing full-scale MCA feature fusion with hierarchical sparse fusion and employing model compression techniques to reduce memory consumption without compromising performance. Second, cross-modal fusion: incorporating SAR, hyperspectral, and textural data to enhance robustness under challenging imaging conditions, leveraging multi-modal attention to exploit complementary information. Third, multi-temporal modeling: extending the three-branch architecture to sequential temporal data with temporal attention and recurrent units, enabling long-term change monitoring such as land cover evolution.

6. Conclusions

The proposed HCTANet model adopts a three-branch architecture that jointly performs bi-temporal semantic segmentation and binary change detection. Its MCA module concurrently extracts and fuses multi-resolution bi-temporal difference features, leveraging the BCD output to explicitly constrain the SS branch and thereby enabling reverse calibration of semantic inference via the difference mask. The ACo-SA mechanism models cross-temporal semantic correlations through cross-temporal cross-attention and cross-window self-attention, efficiently capturing long-range dependencies. The SSRA module fuses deep-level semantic and shallow-level spatial features via residual connections, preserving global consistency while refining fine-grained segmentation boundaries. Experimental results on the SECOND, SenseEarth 2020 and AirFC datasets demonstrate that the model surpasses existing approaches regarding mIoU, SeK, and related metrics, confirming its efficacy in complex scenes.

While our model attains competitive accuracy, it nevertheless retains a larger number of parameters compared with lightweight architectures such as FC-EF. Specifically, the MCA module necessitates the parallel processing of dual-temporal features across five scales, which incurs substantial memory consumption during the stages of feature extraction and fusion. Specifically, the MCA module necessitates the parallel processing of dual-temporal features across five scales, which incurs substantial memory consumption during the stages of feature extraction and fusion.

Future work will focus on lightweight module design to improve computational efficiency, explore cross-modal data fusion strategies for enhanced adaptability to challenging imaging conditions, and extend the framework to multi-temporal dynamic change modeling. Although the current study focuses on urban and facility changes, the HCTANet framework is task-agnostic and can be directly extended to other semantic domains such as forest gain/loss detection. We leave this for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X. and G.W.; methodology, Z.X. and Z.W.; software, Z.X. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.X., G.W. and Z.W.; supervision, G.W. and N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data provided in this study can be made available upon request from the corresponding author, as some content may involve confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the constructive suggestions from the experts and sincerely thank the students who provided help.

Conflicts of Interest

This study has no conflicts of interest, and all participants approved the manuscript for publication.

References

- Albarakati, H.M.; Khan, M.A.; Hamza, A.; Khan, F.; Kraiem, N.; Jamel, L.; Almuqren, L.; Alroobaea, R. A novel deep learning architecture for agriculture land cover and land use classification from remote sensing images based on network-level fusion of self-attention architecture. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 6338–6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Bibi, T.; Rahim, S.; Gul, Y.; Niaz, A.; Mumtaz, S.; Shedayi, A.A. Spatio-temporal change detection of land use and land cover in Malakand Division Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, using remote sensing and geographic information system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 10982–10994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jing, W.; Chi, K.; Yuan, Y. Cross-difference semantic consistency network for semantic change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4406312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ning, X.; Zhang, R.; Chang, D.; Hao, M. Spatial-temporal semantic perception network for remote sensing image semantic change detection. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. Change-guided similarity pyramid network for semantic change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5637917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Wang, M.; Jiang, X.; Xie, G.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, P. Dual-task semantic change detection for remote sensing images using the generative change field module. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zuo, X.; Cheng, X. CGMNet: Semantic change detection via a change-aware guided multi-task network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Guan, H. End-to-end change detection for high-resolution satellite images using improved UNet++. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, R.C.; Le Saux, B.; Boulch, A.; Gousseau, Y. Multitask learning for large-scale semantic change detection. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2019, 187, 102783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xia, G.S.; Liu, Z.; Du, B.; Yang, W.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. Asymmetric Siamese networks for semantic change detection in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5609818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Guo, H.; Liu, S.; Mou, L.; Zhang, J.; Bruzzone, L. Bi-temporal semantic reasoning for the semantic change detection in HR remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5620014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Tian, S.; Ma, A.; Zhang, L. ChangeMask: Deep multi-task encoder-transformer-decoder architecture for semantic change detection. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 183, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridd, M.K.; Liu, J. A comparison of four algorithms for change detection in an urban environment. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 63, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, L.; Prieto, D.F. Automatic analysis of the difference image for unsupervised change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 38, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, D.; Bovolo, F.; Bruzzone, L. A novel change detection method for multitemporal hyperspectral images based on binary hyperspectral change vectors. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 4913–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Pillai, G.V.; Ari, S. Change detection in optical satellite images based on local binary similarity pattern technique. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 15, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, H.; Yan, L.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bruzzone, L.; Atkinson, P.M. MSCD-Net: From unimodal to multimodal semantic change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4508017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.; Gubbi, J.; Ramaswamy, A.; Balamuralidhar, P. ChangeNet: A deep learning architecture for visual change detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, B.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. From W-Net to CDGAN: Bitemporal change detection via deep learning techniques. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 58, 1790–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudt, R.C.; Le Saux, B.; Boulch, A. Fully convolutional Siamese networks for change detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Athens, Greece, 7–10 October 2018; pp. 4063–4067. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Guo, X.; Deng, W.; Shi, S.; Guan, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. Land-use/land-cover change detection based on a Siamese global learning framework for high-spatial-resolution remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 184, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Guo, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Lin, C.; Du, P. Automatic urban scene-level binary change detection based on a novel sample selection approach and advanced triplet neural network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5601518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Bruzzone, L.; Zhu, X.X. Learning spectral-spatial-temporal features via a recurrent convolutional neural network for change detection in multispectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 57, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Bovolo, F.; Bruzzone, L. Unsupervised deep change vector analysis for multiple-change detection in VHR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 3677–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, Z.; Shi, Z. Remote sensing image change detection with transformers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5607514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Si, T.; Ye, C.; Guo, Q. Semantic-aware transformer with feature integration for remote sensing change detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 135, 108774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. CDMamba: Incorporating local clues into mamba for remote sensing image binary change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4405016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Fan, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Han, L. NestNet: A multiscale convolutional neural network for remote sensing image change detection. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 4898–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, Y.; He, H.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, L. Network and dataset for multiscale remote sensing image change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 18, 2851–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Zhou, T.; Liu, J.; Guo, T.; Gong, X.; Ren, J. Multiscale diff-changed feature fusion network for hyperspectral image change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5502713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, F.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Zheng, F.; Chen, X. Y-Net: A multiclass change detection network for bi-temporal remote sensing images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Li, K.; Shao, J. SNUNet-CD: A densely connected Siamese network for change detection of VHR images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 8007805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Tong, X.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, H. MFATNet: Multi-scale feature aggregation via transformer for remote sensing image change detection. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chai, Z.; Deng, H.; Liu, R. A CNN-transformer network with multiscale context aggregation for fine-grained cropland change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 4297–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.G.C.; Patel, V.M. A transformer-based Siamese network for change detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–22 July 2022; pp. 207–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.S.; Xu, Y.Y.; Zhang, C.L.; Xia, G.S.; Peng, Y.X. CAT: A coarse-to-fine attention tree for semantic change detection. Vis. Intell. 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Shao, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, M. MLFA-Net: Multi-level feature-aggregated network for semantic change detection in remote sensing images. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2398070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Du, B.; Cui, X.; Zhang, L. A post-classification change detection method based on iterative slow feature analysis and Bayesian soft fusion. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 199, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Cui, X.; Chen, J. Change vector analysis in posterior probability space: A new method for land-cover change detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2010, 8, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Chen, H.; Yang, S.; Guo, Z. A small-sample-based multiclass change detection method using change vector analysis with adaptive-weight Gaussian mixture model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5626416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, Y. Multi-feature object-based change detection using self-adaptive weight change vector analysis. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Liu, S.; Lin, C.; Meng, Y. An improved change detection approach using tri-temporal logic-verified change vector analysis. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 161, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, T. Remote sensing image change detection combined with saliency. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 18108–18121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Awadhiya, K. Integrating deep change vector analysis and SAM for class-specific change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 18439–18449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Jiang, J. MTSCD-Net: A network based on multi-task learning for semantic change detection of bitemporal remote sensing images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 118, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhao, Z.; Gong, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Xiong, X.; Li, S. Spatially and semantically enhanced Siamese network for semantic change detection in high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H. Dual-dimension feature interaction for semantic change detection in remote sensing images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 9595–9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Long, X.; Zheng, Y. A transformer-based Siamese network and an open optical dataset for semantic change detection of remote sensing images. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 1506–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, A.; Zhang, L. Building damage assessment for rapid disaster response with a deep object-based semantic change detection framework: From natural disasters to human-made disasters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Li, W.; Yang, S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X. BT-HRSCD: High-resolution feature is what you need for a semantic change detection network with a triple-decoding branch. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4416714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Xu, F.; Chen, X.; Dong, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, J. The ClearSCD model: Comprehensively leveraging semantics and change relationships for semantic change detection in high-spatial-resolution remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 211, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Stein, A. Semantic change detection using a hierarchical semantic graph interaction network from high-resolution remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 211, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Su, X.; Wu, C.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. SAAN: Similarity-aware attention flow network for change detection with VHR remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 2599–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Ye, Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Lei, C.; Yang, W.; Li, Y. SCD-SAM: Adapting segment anything model for semantic change detection in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5626713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Gong, Y.; Dong, S. Dual-resolution guided multiscale network for land-cover semantic change detection. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2024, 18, 048502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Guo, H.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. A late-stage bitemporal feature fusion network for semantic change detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 22, 6001105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Su, X.; Zheng, L.; Yuan, Q. Statistic ratio attention-guided Siamese U-Net for SAR image semantic change detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4004405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, F.; Zi, Y.; Zhang, Z. MSSM-SCDNet: A multiclass semantic change detection network suitable for coastal areas based on multiband spatial–spectral attention mechanism. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 15816–15833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lin, S.; Zhong, Y.; Shi, Q.; Li, J. A memory-guided network and a novel dataset for cropland semantic change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4410013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Bao, J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Yu, N.; Yuan, L.; Chen, D.; Guo, B. CSWin Transformer: A general vision transformer backbone with cross-shaped windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 12124–12134. [Google Scholar]

- SenseTime Research. SenseEarth 2020 Change Detection Dataset. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/LiheYoung/SenseEarth2020-ChangeDetection?tab=readme-ov-file (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Ding, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, B.; Bruzzone, L. Joint spatio-temporal modeling for semantic change detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5610814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Han, C.; Xia, J.; Yokoya, N. ChangeMamba: Remote sensing change detection with spatiotemporal state space model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4409720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Y.; Ye, Z.; Yang, H. Semantic enhancement and change consistency network for semantic change detection in remote sensing images. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2496790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).