Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This study developed an optimized deep learning framework for daily all-wave net radiation estimation over the Tibetan Plateau, with Xception achieving optimal balance between daily prediction accuracy (R2 > 0.94), computational efficiency, and physical interpretability under all-weather conditions.

- The framework demonstrated superior performance in daily monitoring, outperforming established products particularly in complex terrain while effectively resolving fine-scale spatial heterogeneity.

What is the implication of the main findings?

- SHAP analysis confirms physical consistency with dominant astronomical/topographic drivers governing daily variations.

- The study identified key pathways for operational daily radiation monitoring, emphasizing automated preprocessing of multi-source data, enhanced sub-diurnal dynamics capture, and physical constraint integration to advance reliable long-term daily product generation.

Abstract

Accurate daily surface net radiation (Rn) estimation over the Tibetan Plateau’s complex and highly heterogeneous terrain is essential for advancing the understanding of land–atmosphere exchanges and regional climate processes. This study developed an optimized deep learning framework that systematically evaluates 19 CNN architectures using a per-pixel multivariate regression design (1 × 1 × 21). The channel-rich representation incorporates engineered neighborhood descriptors to statistically embed spatial context while fully avoiding the mosaic and boundary artifacts common in patch-based approaches. Among all tested networks, Xception delivered the best combination of accuracy (R2 > 0.94), computational efficiency, and physical consistency. Its depthwise separable convolutions and skip connections enable hierarchical nonlinear cross-channel feature learning, effectively capturing the complex dependencies between surface variables and . Independent validation confirmed stable performance under diverse weather conditions and substantially better skill than GLASS, especially across rugged terrain and high-albedo surfaces. SHAP analysis further highlights physically meaningful behavior, with astronomical and topographic factors contributing ~70% and surface properties ~25% to predictions. Remaining challenges include dependence on continuous high-quality multi-source inputs and scale effects from mixed pixels. Future work will enhance operational deployment through automated daily preprocessing, improved sub-diurnal characterization via multi-scale data fusion, and stronger physical constraints to increase reliability.

1. Introduction

As a key component of the land–atmosphere energy balance, surface net radiation (Rn) regulates a wide range of processes within the global and regional climate systems, hydrological cycles, and terrestrial ecosystems [,,]. Accurate estimation of Rn at high spatial and temporal resolutions—particularly under all-weather conditions and at daily scales—is essential for quantifying the exchange of energy and mass between the surface and the atmosphere. Reliable daily datasets are also crucial for applications such as climate change assessment, agricultural water management, and urban heat mitigation [,,]. However, existing approaches based on ground observations or traditional satellite retrievals are often limited by cloud contamination and incomplete temporal coverage, which restrict their use in process-based and regional analyses [,]. Therefore, developing approaches capable of generating accurate and temporally continuous estimates across diverse meteorological and surface conditions remains an important challenge in remote sensing and land surface studies, with significant implications for Earth system modeling and environmental research.

Current approaches for estimating include hybrid algorithms combining meteorological and satellite observations []; data assimilation and fusion techniques integrating multi-source datasets [,]; data-driven models ranging from classical machine learning to deep learning architectures [,,]; and topographic corrections based on digital elevation models (DEMs) [,,]. Each of these pathways offers specific advantages. Some frameworks can generate high-resolution (~1 km) products with root-mean-square errors (RMSE) below 25 W·m−2 [,,]. Machine learning methods capture complex nonlinear relationships effectively [], while DEM-based corrections improve accuracy in mountainous areas such as the Tibetan Plateau [,]. Certain models also exhibit strong adaptability and computational efficiency in data-scarce regions by leveraging transfer learning and simplified input requirements [,]. Despite these advances, achieving accurate daily, all-weather estimation remains challenging. Optical methods rely on clear-sky assumptions, and cloud-induced data gaps interrupt temporal continuity [,]. Even recent all-weather retrievals still face substantial uncertainty in estimating surface temperature and albedo under cloudy conditions [,]. Simplified diurnal schemes, such as sinusoidal fitting, cannot adequately represent rapid atmospheric variations [,]. Other limitations include error propagation from input variables [,], restricted model generalization across heterogeneous surfaces such as snow and urban areas [,], and the scarcity of reliable ground observations for validation [,]. Collectively, these issues hinder further improvements in model accuracy and operational robustness.

Over the Tibetan Plateau, estimating remains particularly challenging because of its complex topography and distinctive climatic conditions. Although recent advances in high-resolution datasets [], machine and deep learning algorithms [,], and multi-source data fusion [,] have enhanced retrieval accuracy, substantial uncertainties persist. Neglecting terrain shading and three-dimensional radiative transfer can introduce errors exceeding 100 W·m−2 [,]. The scarcity of aerosol optical depth (AOD) observations, coarse albedo datasets [], and simplified albedo parameterizations in land surface models further compromise accuracy []. Spatial and temporal instability in empirical coefficients [] and the limited transferability of machine learning models across varying surface types also weaken model robustness []. All-weather estimation remains problematic, as most algorithms are optimized for clear-sky conditions [], while persistent cloud cover and oversimplified diurnal representations hinder continuous product generation []. In addition, the paucity of reliable ground-based radiation measurements and inconsistencies among reanalysis datasets continues to constrain product validation and long-term trend assessment [].

Deep learning has recently demonstrated strong potential for mapping Earth system variables, offering new opportunities for estimation. Unlike conventional empirical or physically based models, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) architectures can directly learn nonlinear relationships and spatiotemporal dependencies from multi-source datasets, thereby improving accuracy and robustness [,]. Their end-to-end frameworks allow direct estimation from input data, reducing the error propagation commonly observed in multi-step physical algorithms []. Moreover, deep learning enables the effective integration of heterogeneous information—from geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites to reanalysis datasets and ground observations—facilitating the generation of kilometer scale, all-weather products. This capability is particularly valuable in mountainous and high-latitude regions where traditional approaches often perform poorly [,,]. Transfer learning further enhances scalability by adapting models trained in data-rich areas to regions with limited observations [,]. Despite these advantages, several challenges remain. Model generalization tends to weaken under unseen or extreme conditions, increasing the risk of overfitting [,]. The development of reliable models also depends on large, high-quality training datasets, which are still limited in spatial and temporal coverage [,]. In addition, the high computational cost associated with training and optimization constrains large-scale or real-time applications [,]. Addressing these issues—particularly those related to generalization, data dependency, and computational efficiency—has become a central focus of current research in data-driven estimation.

To address these research gaps, this study developed a deep learning framework based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for estimating daily all-weather surface net radiation over the Tibetan Plateau. We systematically evaluated 19 network architectures and investigated the influence of key hyperparameters, such as maximum training epochs and batch size. By incorporating essential parameters including aerosol optical depth and surface albedo, the framework aims to mitigate uncertainties arising from data scarcity and spatiotemporal discontinuities. SHAP interpretability analysis was employed to elucidate the model’s decision-making mechanisms and assess their consistency with physical processes. The model was rigorously validated using multiple ground-based observation sites across the plateau, with a focus on its stability and generalization capability under diverse weather conditions. Furthermore, comparative analysis with existing mainstream products was conducted to evaluate the model’s performance in capturing spatial details over complex terrain. This study aims to provide more reliable data support for research on surface energy balance and eco-hydrological processes in high-altitude regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Situ Observations and Data Quality Control

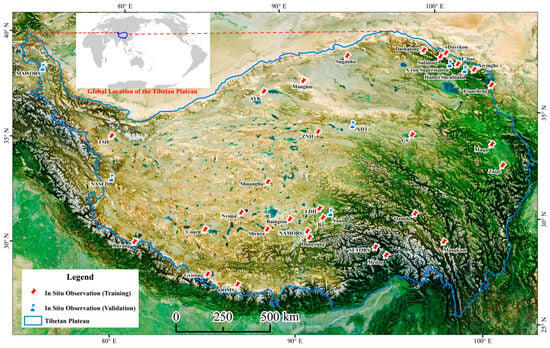

This study utilized in situ daily observations from multiple comprehensive monitoring networks across the Tibetan Plateau. Data were obtained from the Tibetan Plateau Integrated Three-Dimensional Observation and Research Platform (TPEITORP) [,], the upper reaches of the Heihe River Basin (HRB) [,], the Integrated Monitoring Dataset of Permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau (IMDP) [], the Alpine Semi-Arid Grassland and Lake Underlying Surface Process Observation Dataset in the Source Region of the Yellow River (SRYR) [,], the Cold and Arid Region Network of Lanzhou University (CARN; https://mcs.lzu.edu.cn/), and the China Terrestrial Ecosystem Flux Research Network (ChinaFLUX; http://www.chinaflux.org/). In total, these sources provided 94,518 daily records from 45 stations, which are widely distributed and representative of the typical land surface types over the plateau, thereby ensuring data representativeness and model generalization potential. For effective model training and evaluation, the dataset was divided into independent training and validation subsets. Specifically, 69,687 daily samples (73.7% of the total) from 39 stations were used to train a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), enabling it to learn the complex nonlinear mapping between input features and surface net radiation flux. The remaining 24,831 daily records (26.3%) from six separate stations were reserved as the validation set to objectively evaluate the model’s generalization performance.

Each station is equipped with a four-component radiometer, enabling the simultaneous measurement of both upward and downward shortwave and longwave radiation, from which the is derived. Prior to release, the data underwent a series of rigorous quality control procedures, including completeness checks, removal of outliers based on physically plausible thresholds, energy balance consistency checks, and verification and correction using the four-component radiation balance equation. The values were further verified and corrected using the four-component radiation balance equation. Details of the in situ observations are provided in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the in situ observation site locations on the Tibetan Plateau.

Table 1.

Information about in situ observation sites.

The daily is calculated directly from the quality-controlled 10 min (or 30-min) averaged data. The calculation formula is as follows []:

where: is the daily mean net radiation flux (W/m2), is the quality controlled average net radiation flux during the i-th time interval (W/m2), is the corresponding observation time interval in seconds (e.g., 600 or 1800 s), is the total number of valid observation periods in one day, and is the total number of seconds in a day (86,400 s).

2.2. Remote Sensing Datasets and Preprocessing

Accurate estimation of surface net radiation requires integrating variables that represent both surface and atmospheric radiative processes. It is crucial to define the scope of the “all-weather” estimation capability based on the physical properties of the primary satellite sensors used. Our model relies on optical and thermal infrared remote sensing data, which provide critical information for estimating under a wide range of conditions—from clear skies to cloudy skies where the sensor can retrieve valid observations. However, the signal from these wavelengths is subject to complete attenuation under dense clouds and particularly during heavy precipitation events (e.g., intense rainfall or snowfall). Consequently, in this study, the term “all-weather” operationally refers to conditions where retrievable satellite observations exist, encompassing clear, thin-cloud, and cloudy (non-precipitating or with light precipitation) scenarios.

Surface reflectance (MOD09GA/MYD09GA) determines surface albedo and absorbed shortwave energy, capturing variations in vegetation, soil background, and snow conditions that indirectly reflect soil moisture dynamics while maintaining consistency in data sources. Therefore, multi-band MODIS reflectance data were incorporated instead of in situ or reanalysis-based soil moisture products to ensure uniform spatial and temporal coverage [,]. Land surface temperature (TRIMS LST) governs upwelling longwave radiation via the Stefan–Boltzmann law and indicates the surface thermal state under all-weather conditions []. Aerosol optical depth and column water vapor (MCD19A2) quantify atmospheric scattering, absorption, and re-emission processes affecting both shortwave and longwave fluxes [,]. Snow cover fraction (MOD10A1F/MYD10A1F) modulates surface albedo and emissivity, influencing the seasonal radiation balance over high-elevation regions []. Finally, the daily mean blue-sky albedo provides a physically consistent representation of surface reflectivity under both clear- and cloudy-sky conditions, improving spatiotemporal continuity over complex terrain []. Collectively, these variables capture the key physical controls on from the surface and atmosphere, ensuring robust, all-weather radiative flux estimation. All datasets were harmonized to a spatial resolution of 1 km and a daily temporal scale, co-registered to a unified coordinate system to maintain spatial–temporal consistency and comparability across variables.

Surface reflectance data (MOD09GA/MYD09GA) from the Terra and Aqua platforms provided seven spectral bands covering 459–2155 nm and were processed using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. Cloud- and aerosol-contaminated pixels were identified and removed based on the MODIS Quality Assurance (QA) layers, followed by linear temporal interpolation to reconstruct continuous, cloud-free reflectance time series. The TRIMS LST dataset (2000–2024) provides daily 1 km all-weather land surface temperature derived from MODIS observations. It reconstructs missing or cloud-contaminated LST pixels by integrating multi-source satellite thermal infrared data and reanalysis fields through a temporal decomposition model, ensuring seamless spatiotemporal continuity [].

Atmospheric and cryospheric variables were obtained from the MAIAC and MODIS snow products, respectively. The MCD19A2 dataset, generated using the Multi-Angle Implementation of Atmospheric Correction (MAIAC) algorithm, provides daily 1 km aerosol optical depth (AOD) and column water vapor (CWV) data. These variables were retrieved from GEE and temporally reconstructed using a tensor completion method to enhance completeness []. Daily snow cover products (MOD10A1F/MYD10A1F) were used to calculate the Normalized Snow Index (NDSI), reflecting snow-induced variations in albedo and radiative fluxes across the Tibetan Plateau. Additionally, the daily mean blue-sky albedo dataset—generated by a convolutional neural network (CNN) framework that integrates MODIS multi-angle reflectance, atmospheric parameters, and surface characteristics—was incorporated to provide spatially and temporally continuous surface albedo under both clear- and cloudy-sky conditions []. All datasets were reprojected, resampled, and temporally aligned, forming a consistent and comprehensive multi-source data framework for subsequent estimation.

2.3. Geographic and Astronomical Radiation Variables

To describe the geographic and solar geometry characteristics of each pixel, latitude, longitude, elevation, and daily were calculated. represents the theoretical maximum incoming solar radiation at the surface without atmospheric attenuation and serves as a reference for potential radiation input. The calculation follows standard solar geometry formulations [,]:

Specifically, the Earth–Sun distance correction factor () accounts for the annual variation in the Earth–Sun distance caused by the elliptical orbit, resulting in approximately ±3.3% fluctuation in received solar irradiance. The solar declination () represents the angular position of the Sun relative to the equatorial plane, varying seasonally between +23.45° and −23.45°, and determining the solar elevation angle at a given latitude. The sunset hour angle () defines the length of daytime, thus controlling the duration of potential solar radiation at the surface. J is the Julian day, Gsc is the solar constant (1367 W/m2).

2.4. CNN Model Selection and Architectural Adaptation

2.4.1. Feature Optimization for All-Weather Surface Net Radiation Estimation

Based on an initial set of 23 predictive features derived from multi-source remote sensing data—including surface reflectance, albedo, land surface temperature, atmospheric composition, and snow cover—a feature selection procedure was applied to mitigate multicollinearity and optimize the input feature set for the subsequent convolutional neural network (CNN). A stepwise multivariate regression approach was employed to systematically identify and retain predictors with the highest informational value and lowest redundancy. The method used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and p-values (with inclusion and exclusion thresholds set at 0.05 and 0.10, respectively) to evaluate statistical significance. Starting from a null model, variables were iteratively incorporated based on their contribution to improving model explanatory power, while those rendered statistically redundant by newly added features were removed at each step. This iterative process ensured the final feature subset minimized redundancy while preserving independent explanatory power for predicting .

The stepwise regression analysis yielded an optimized set of 21 features: AOD, band7, aspect, slope, band1, CWV, latitude, longitude, band6, band2, LST, sunrise hour angle, NDVI, NDSI, band3, albedo, band4, elevation, solar constant, solar declination, earth-sun distance correction factor, and extraterrestrial solar radiation. This refined feature set will serve as the definitive input to the CNN architecture. By reducing data redundancy and the risk of overfitting, it enhances both the interpretability and generalizability of the model, providing a robust feature foundation for high-accuracy estimation.

2.4.2. Feature Normalization

To standardize feature magnitudes and stabilize Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) training, the 21 selected features were normalized to a [0, 1] range using global min–max scaling, with transformation parameters based on worldwide value ranges summarized in Table 2. This normalization ensures consistent and physically interpretable scaling of all input variables, thereby accelerating model convergence and enhancing generalizability across diverse geographical regions.

Table 2.

Input features and their global normalization ranges.

2.4.3. Convolutional Neural Network Architecture and Model Configuration

In contrast to previous studies that typically utilized two-dimensional image patches (e.g., 3 × 3–41 × 41 km2) to capture spatial context around central pixels, the patch-based method often produces mosaic or boundary artifacts in continuous spatial predictions. These artifacts arise from inconsistencies in patch boundaries, stride settings, or aggregation methods between training and inference stages.

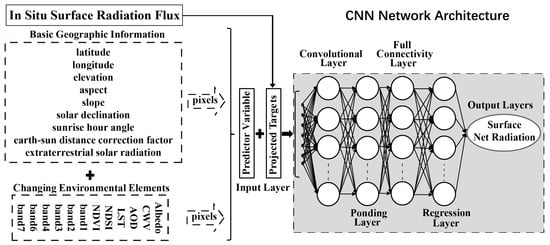

To address these issues while maximizing the use of spectral and auxiliary information, this study frames estimation as a per-pixel multivariate regression task per-pixel multivariate regression task using a channel-rich input representation. These channels include pixel-level spectral, thermal, and topographic variables, as well as engineered neighborhood descriptors (local mean, variance, and gradient metrics) computed within surrounding windows. Thus, spatial context is incorporated statistically rather than through explicit 2-D patches, ensuring spatial continuity without patch-boundary artifacts. Although the input does not contain a 2-D image grid, modern CNN backbones can operate effectively on channel-rich but spatially compact inputs. In this case, convolutional filters primarily learn nonlinear cross-channel interactions, providing hierarchical feature extraction and regularization through weight sharing. Therefore, CNNs remain suitable for this multivariate regression task even without explicit spatial dimensions.

Within the CNN architecture, these multi-source variables are processed through hierarchical convolutional layers combined with nonlinear activation functions, enabling automatic learning of feature representations at multiple abstraction levels. We implemented representative network architectures from five categories: Classical Models (AlexNet, VGG16/19), Residual & High-Performance Models (ResNet, DenseNet, Xception), Lightweight & Mobile-Optimized Models (MobileNet v2, ShuffleNet), Specialized Models (U-Net), and Pre-trained Models (Table 3). Specifically, residual connections enable deeper networks without gradient degradation, inception modules capture multiscale feature interactions, and depthwise separable convolutions improve computational efficiency. We adapted all networks for regression by replacing their original classification heads with a custom regression module consisting of a global average pooling layer followed by a fully connected regression layer (Figure 2). The pooling operation condenses learned feature maps into compact representations, while the final layer produces a single continuous value representing the estimated .

Table 3.

Summary of selected CNN model architectures by category.

Figure 2.

Network Adaptation for Regression.

For model optimization, we trained all architectures using the RMSProp optimizer with standardized settings to ensure fair comparisons. Our comprehensive optimization strategy incorporated three key elements to enhance model robustness: L2 regularization (λ = 1 × 10−4) was applied to prevent overfitting to specific station characteristics by discouraging large weights; gradient clipping at a threshold of 0.95 was implemented to ensure stable training dynamics; and most critically, we maintained strict spatial independence between training and test sets throughout the optimization process to prevent any data leakage and ensure genuine generalization capability. The learning rate was initialized at 1 × 10−3 and decayed exponentially by a factor of 0.95 every five epochs, allowing for precise parameter adjustments during later training stages. We further enhanced generalization by shuffling the dataset at the start of each epoch to prevent order memorization. Training progress was monitored in real-time using the MATLAB 2024b Deep Learning Toolbox visualization interface. These clarifications have now been added to ensure the input design and the role of CNNs are clearly understood by readers and consistent with the research objectives.

2.5. SHAP-Based Interpretability

To interpret the CNN regression model and quantitatively assess the contribution of each predictor to the estimated , the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) method was adopted []. SHAP is grounded in cooperative game theory and provides a unified framework for model-agnostic interpretation. It assigns each input variable a Shapley value, which represents the average marginal contribution of that feature to the model prediction relative to a baseline expectation.

For a prediction based on M features, the Shapley value for the feature is defined as:

where denotes the full set of features, is a subset of excluding feature, and is the model output when only features in are considered. The SHAP value thus measures how the inclusion of feature changes the model output, averaged over all possible feature combinations.

For each sample, the model prediction can be decomposed as:

where is the mean prediction over the dataset, and the summation term represents the additive contribution of each feature.

To quantify the global importance of each predictor, the mean absolute SHAP value across all samples was calculated:

where denotes the global importance of feature , and is the total number of samples. Features with larger values have a stronger influence on the model’s predictions.

In this study, global SHAP analysis was used to identify the dominant environmental and radiative drivers of over the Tibetan Plateau, while local SHAP values were applied to interpret individual predictions and capture site-specific or temporal variability. This approach bridges the gap between deep learning performance and physical interpretability, providing insights into how remote sensing, meteorological, and surface parameters jointly modulate the spatiotemporal variability of surface net radiation.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was evaluated using the following three core statistical metrics, which provide complementary information from the perspectives of error magnitude, correlation, and dispersion:

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): Measures the average deviation between model predicted values and true values, with higher sensitivity to larger errors. It is calculated as:

where represents the true observed value of the i-th sample, is the corresponding model predicted value, and N is the total number of samples. A smaller RMSE value indicates higher overall prediction accuracy of the model.

Coefficient of Determination (R2): Used to assess the proportion of the variance in the observed values that is predictable from the model’s inputs. It provides a measure of how well the model’s predictions replicate the observed outcomes.

where and represent the mean of the true values and predicted values, respectively. An R value closer to 1 indicates better linear agreement between predictions and true values.

Mean Bias Error (MBE): Provides the average of the prediction errors, retaining their sign. It is less sensitive to outliers than RMSE and is primarily used to identify the systematic tendency of a model to over-predict (negative bias) or under-predict (positive bias).

Furthermore, to comprehensively compare the performance of different models, this study employed Taylor diagrams. A Taylor diagram is a powerful visualization tool that integrates the standard deviation, correlation coefficient with observations (which is the square root of R2 for linear models, providing a comparable visual metric), and centered root-mean-square difference (RMSE) of multiple models in a single plot, thereby intuitively revealing the capabilities and differences of various models in capturing data variance and distribution patterns.

2.7. Validation Strategy

Model validation strictly followed the principle of independent testing to ensure the reliability and generalizability of the evaluation results. Validation was conducted at two levels:

Overall Performance Validation: After training was complete, a reserved test set (which had not participated in any training or hyperparameter optimization process) was used to evaluate all 19 CNN models. This test set contained samples outside the spatio-temporal range of the training data, with the aim of testing the model’s basic ability to handle unknown data. The metrics (RMSE, R2, MBE) calculated based on this set were used to compare among models to select the optimal architecture.

Independent Site Validation and Generalization Capability Assessment: To further examine the applicability of the optimal model in real-world complex scenarios, this study used completely independent data sources for validation. Data from 6 observation sites with different typical underlying surfaces were selected. Data from these sites were not used at any stage for model training or debugging, forming a purely external validation dataset.

Validation was conducted under both all-weather conditions and cloudy conditions to quantitatively analyze the impact of meteorological factors (especially clouds) on model performance. For each site, the coefficient of determination (R2), RMSE, and MBE between the predicted values and site observations were calculated. By plotting and analyzing scatter plots and density plots, the distribution of predicted values relative to the 1:1 line of true values was visually inspected to identify any systematic overestimation or underestimation, with the MBE providing a quantitative measure of this overall bias. The R2 value for each site’s regression was a key indicator of performance.

3. Results

3.1. Optimal Convolutional Neural Networks and Parameter Selection

Numerous studies have demonstrated that Maximum Epochs (MaxEpochs) and Mini-Batch Size (MiniBatchSize) are among the most influential hyperparameters governing the convergence and generalization of deep neural networks [,,]. Building on preliminary experiments that evaluated a range of batch sizes, this study systematically evaluated these two parameters. Our comparative analysis revealed that a MiniBatchSize of 365 yielded optimal gradient stability and a favorable balance between convergence speed and generalization, whereas MaxEpochs primarily determined the model’s ability to achieve full convergence without overfitting. To balance training efficiency with predictive robustness, we further refined the configuration of both parameters accordingly. All other hyperparameters—including the learning rate, regularization coefficient, and gradient threshold—were held constant across models to ensure consistent training conditions and prevent confounding effects [].

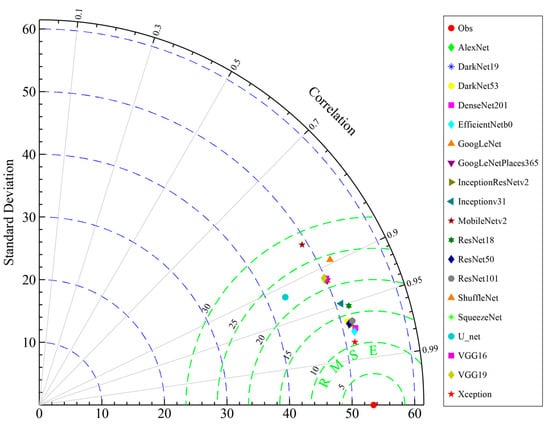

Under a standardized hyperparameter configuration (MiniBatchSize = 365), Figure 3 presents a comprehensive assessment of 19 convolutional neural network architectures for daily-scale net radiation estimation over the Tibetan Plateau, using a Taylor diagram. The results revealed a clear performance hierarchy among the models in terms of standard deviation and correlation coefficient. Xception, DenseNet201, and EfficientNetB0 formed the top-performing group, achieving standard deviations closest to observational reference values while maintaining the highest correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.94). The effectiveness of these models stems from their distinctive architectural designs: Xception employs depth wise separable convolutions to decouple spatial and channel-wise feature learning; DenseNet201 facilitates multi-level feature reuse and fusion through dense connectivity; and EfficientNetB0 optimizes the balance between network depth, width, and resolution via compound scaling. In comparison, the ResNet and Inception families demonstrated consistent yet slightly inferior performance, with marginally higher standard deviations indicating a systematic bias in capturing radiation extremes. This stratification underscores that both network depth and connectivity patterns collectively determine a model’s capacity to resolve multi-scale features in the plateau’s complex radiation regime.

Figure 3.

Standard deviation of model predictions versus observations. The annotated points (e.g., AlexNet, DenseNet201, Xception) correspond to the 19 distinct convolutional neural network architectures evaluated in this study.

Conversely, lightweight models—including MobileNetv2, ShuffleNet, and SqueezeNet—exhibited considerable limitations. Their predicted sequences displayed standard deviations that deviated markedly from observed values, alongside correlation coefficients generally below 0.85, confirming inherent difficulties in resolving spatial heterogeneity. Notably, the U-Net architecture produced the most pronounced smoothing effect. Although its encoder–decoder structure ensures output stability, this comes at the cost of systematically underestimating radiation extremes, a particular drawback under the rapidly changing weather conditions characteristic of the plateau.

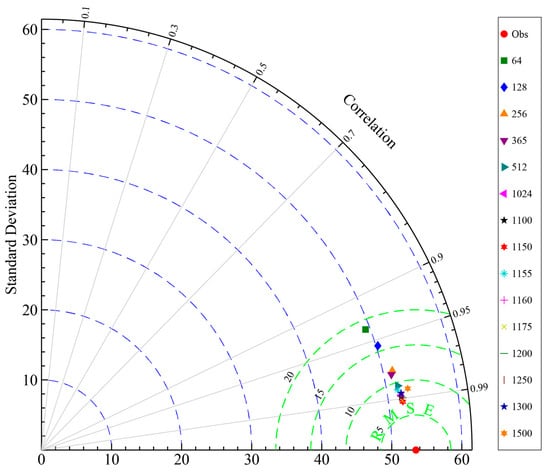

This analysis examined how training duration affects surface radiation balance predictions over the Tibetan Plateau, using 15 epoch settings from 64 to 1500. As shown in Figure 4, model performance varied nonlinearly with training epochs. The target radiation sequence maintained a stable standard deviation (49.35–53.01) across all epoch settings, consistent with the region’s strong diurnal and seasonal radiative patterns. Performance improved substantially as epochs increased from 64 to 1150, with RMSE dropping from 18.63 to 7.13 (61.7% reduction) and R2 rising from 0.878 to 0.982. The extended training enables better capture of medium-to-long-term processes like seasonal albedo changes and persistent cloud effects, while filtering short-term weather noise.

Figure 4.

Correlation between predicted and observed values across different model configurations. The numbers (64 to 1500) denote the Maximum Epochs used during model training.

Beyond 1200 epochs, performance declined (RMSE: 8.86, R2: 0.972), indicating overfitting and model limitations in representing interannual variability and delayed snow-albedo feedbacks. This reveals a key trade-off between learning complex patterns and maintaining generalization capability. The optimal epoch range is 1000–1200, with best performance at 1150 epochs (RMSE: 7.13, R2: 0.982). This configuration captures essential seasonal radiation features while minimizing prediction error.

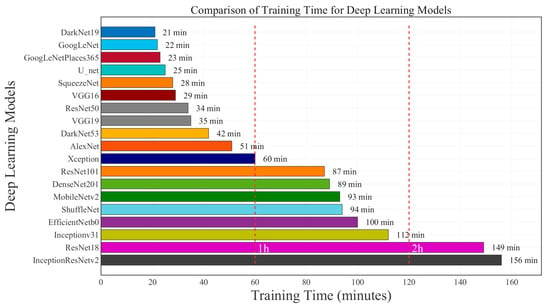

Figure 5 presents the training times of the 19 convolutional neural network architectures evaluated in this study. The results revealed substantial variation in computational requirements, directly corresponding to differences in model complexity and design. Architectures with simpler structures and fewer parameters, such as DarkNet19 (21 min), GoogLeNet (22 min), and GoogLeNetPlaces365 (23 min), required the shortest training times. In contrast, models with deeper networks or complex connectivity mechanisms, including ResNet101 (87 min), DenseNet201 (89 min), MobileNetv2 (93 min), and EfficientNetb0 (100 min), exhibited considerably longer training durations. The Xception model, with a training time of 60 min, fell into a moderate range—neither as fast as the lightweight models nor as time-consuming as the most complex ones. This distribution of training times demonstrates that while model depth and structural complexity directly impact training efficiency, training time alone is not a definitive predictor of model performance.

Figure 5.

Training Time Comparison Across Deep Learning Architectures.

Based on a comprehensive evaluation of model accuracy, training efficiency, and the capacity to represent key geophysical processes, Xception was identified as the optimal model in this study. It demonstrated exceptional predictive performance, evidenced by a high agreement with observations on the Taylor diagram (R2 > 0.94). This performance is attributed to its deep separable convolutions and compound scaling mechanism, which enable effective learning of multi-scale radiative features and complex nonlinear relationships. Furthermore, during the step-size analysis, Xception achieved the best goodness-of-fit at the optimal step size of 1150 (RMSE = 7.13, R2 = 0.982).

This indicates that its architecture successfully captures the dominant radiative processes at seasonal and sub-seasonal scales while filtering out short-term noise, thereby more accurately representing the physical mechanisms of land–atmosphere interactions over the Tibetan Plateau. In terms of computational cost, Xception required only 60 min for training, making it significantly more efficient than other high-performance models of similar complexity (e.g., DenseNet201, InceptionResNetv2) while substantially outperforming faster, lightweight models. Consequently, Xception achieves an optimal balance among predictive accuracy, physical representativeness, and computational cost, establishing it as the most suitable choice for estimating daily mean net radiation in this research.

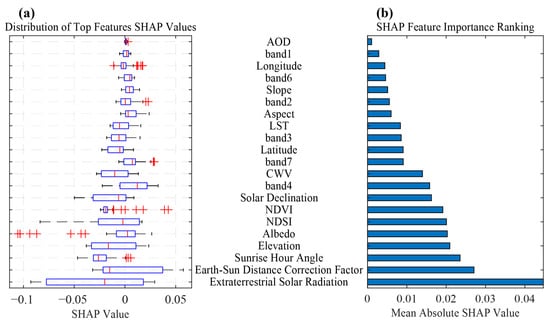

3.2. SHAP-Based Feature Importance Analysis Under Xception’s Architecture

Building upon the established hierarchical architecture of the Xception model—characterized by its depthwise separable convolution design that efficiently processes multi-scale spatial and spectral patterns—the SHAP-based feature importance analysis revealed a distinct three-tiered structure in the model’s estimation of . This architectural framework enables the model to systematically prioritize features according to their physical significance and predictive value (Figure 6). The most influential features are astronomical and geometric parameters—namely, the Earth–Sun distance correction factor (≈0.038), sunrise hour angle (≈0.035), solar declination (≈0.030), and elevation (≈0.032) (Figure 6). These variables collectively establish the theoretical top-down irradiance incident at the surface, and their consistently positive SHAP values align well with fundamental principles of solar radiation physics, forming what can be termed the core layer of the model, accounting for approximately 70% of the total feature influence. At an intermediate level of importance, surface and atmospheric variables—including land surface temperature (LST ≈ 0.019), column water vapor (CWV ≈ 0.022), surface albedo (≈0.028), and NDVI (≈0.020)—constitute a regulatory layer responsible for about 25% of the model’s decisions. Each of these plays a specific physical role: LST incorporates the bidirectional feedback inherent in the surface energy balance; CWV enhances net radiation through its role in downwelling longwave radiation; albedo directly governs the reflection of shortwave radiation; and NDVI modulates the partitioning of available energy via vegetation-related evapotranspiration processes.

Figure 6.

Hierarchical interpretation of feature importance in Xception model using SHAP analysis: (a) Beeswarm plot of SHAP values (elements from left to right: whiskers show data range, box shows IQR, midline indicates median, cross marker represents mean); (b) Mean absolute SHAP values for global feature ranking. All negative values are displayed with standard minus signs (−).

In contrast, features such as aerosol optical depth (AOD ≈ 0.005), the blue spectral band, and longitude exhibit minimal influence, as reflected in their narrow SHAP value distributions. The particularly negligible contribution of AOD suggests that the model effectively captures information related to atmospheric scattering and absorption through the combined spectral signatures of multiple optical bands (band1–band4 and band7), thereby rendering the standalone AOD feature largely redundant. This group constitutes a refinement layer, contributing less than 5% to the overall output, and appears to provide only minor local adjustments rather than driving large-scale variations in .

3.3. Model Validation Under All-Weather and Cloudy Conditions

The proposed Xception-based CNN model for estimating daily net surface radiation (Rn) was validated against independent ground-based observations from six sites under all-weather and cloudy-sky conditions. This independent daily-scale assessment confirms the model’s robustness across diverse atmospheric and surface regimes.

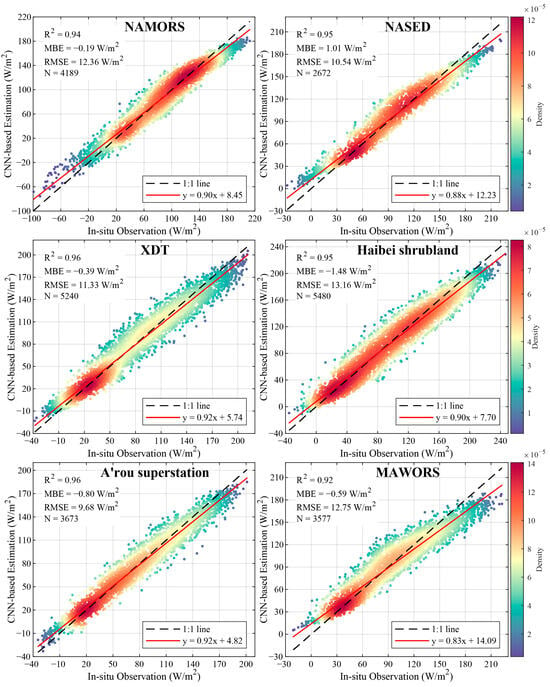

3.3.1. All-Weather Validation

Under all-weather conditions, the model achieved high accuracy across all validation sites (Figure 7), with R2 values ranging from 0.92 to 0.96. The MBE and RMSE varied between −1.48 to 1.01 W/m2 and 9.68 to 13.16 W/m2, respectively, indicating consistent performance in capturing the daily variability under varied meteorological conditions. Notably, the XDT site (N = 5240) exhibited well-balanced performance (R2 = 0.96, y = 0.92x + 5.74), with a slope close to unity and a small positive intercept, suggesting minimal systematic bias. The Haibei shrubland site, which had the largest sample size (N = 5480), also performed strongly (R2 = 0.95, y = 0.90x + 7.70), aligning with the overall regression trends. The A’rou superstation (N = 3673) recorded the lowest RMSE (9.68 W/m2) while maintaining an R2 of 0.96. Both NAMORS (N = 4189) and NASED (N = 2672) achieved R2 values of 0.94 and 0.95, respectively, with similar regression relationships (y = 0.90x + 8.45 and y = 0.88x + 12.23). Even at MAWORS, where performance was comparatively lower (R2 = 0.92, y = 0.83x + 14.09), the regression structure remained consistent.

Figure 7.

Comparison of In situ Observed and CNN Simulated Surface Net Radiation Flux under All-Weather Conditions.

Regression slopes across all sites were slightly below unity (0.83–0.92) with positive intercepts (4.82–14.09), forming a coherent regression-to-the-mean pattern. This reflects the model’s ability to generalize physical relationships across varying conditions without overfitting. The large sample sizes (N = 2672–5480) further support the statistical reliability of these results.

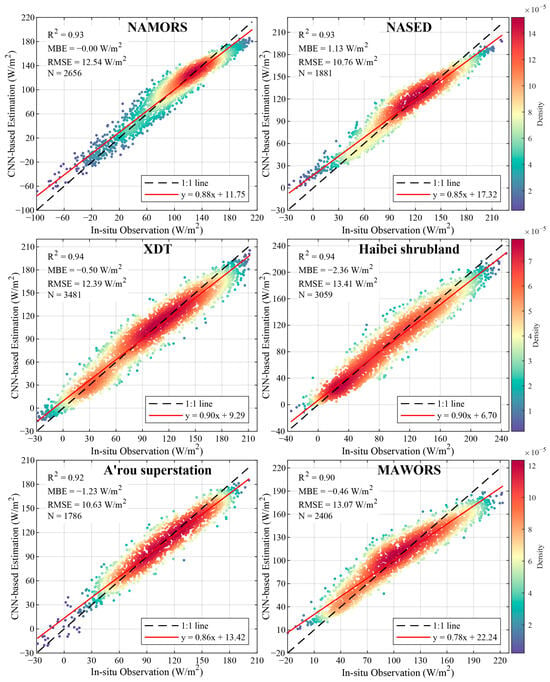

3.3.2. Cloudy-Sky Validation

Under cloudy-sky conditions, the model maintained strong performance despite increased uncertainties from variable cloud optical properties (Figure 8). R2 values ranged from 0.90 to 0.94, with MBE and RMSE between −2.36 to 1.13 W/m2 and 10.63–13.41 W/m2, respectively—only a slight decline compared to all-weather results. The XDT site (N = 3481) recorded the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.94, y = 0.90x + 9.29), while the Haibei shrubland site (N = 3059) showed similarly robust results (R2 = 0.94, y = 0.90x + 6.70). The A’rou superstation (N = 1786) achieved the lowest RMSE (10.63 W/m2) with an MBE of −1.23 W/m2, confirming model effectiveness even with limited cloudy-sky samples. Both NAMORS (N = 2656) and NASED (N = 1881) attained R2 = 0.93, with slopes of 0.88 and 0.85, and MBE values of −0.00 W/m2 and 1.13 W/m2, respectively. MAWORS exhibited the lowest slope (0.78) and highest intercept (y = 0.78x + 22.24), along with an MBE of −0.46 W/m2, likely due to persistent cloud cover and site-specific shrubland characteristics. Compared to all-weather results, regression slopes under cloudy conditions were systematically lower (0.78–0.90) and intercepts higher (6.70–22.24), indicating a more pronounced regression-to-the-mean tendency. This conservative bias reflects the model’s response to the high spatiotemporal variability in cloud optical thickness and its nonlinear influence on surface radiation.

Figure 8.

Comparison of In situ Observed and CNN Simulated Surface Net Radiation Flux under Cloudy Conditions.

The CNN model demonstrated robust and physically consistent performance under both all-weather and cloudy-sky conditions. Its sustained accuracy under cloudy skies supports its use in continuous, all-weather monitoring for surface energy balance and land–atmosphere interaction studies.

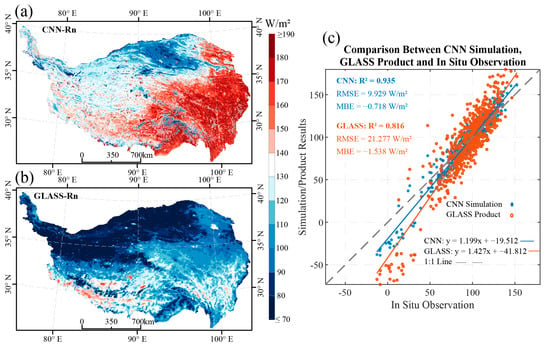

3.4. Spatial Pattern Comparison and Independent Validation

In the generated spatial maps, the CNN model demonstrated superior capability in resolving fine-scale heterogeneity of surface net radiation compared to the GLASS product (Figure 9a,b). Across complex terrain, the CNN more accurately represented topographic influences such as shadowing and slope-aspect variations, which are often oversmoothed in the GLASS data. The model also exhibited enhanced sensitivity in high-altitude glacier and snow-covered zones, where it successfully captured the characteristically low values of surface net radiation resulting from high albedo—a key physical signal that is frequently attenuated or inadequately represented in the GLASS product. Furthermore, in regions characterized by extreme radiation values, the CNN significantly reduced systematic biases observed in GLASS, leading to improved spatial consistency and physical realism across heterogeneous land-cover mosaics.

Figure 9.

Spatial pattern comparison and validation of surface net radiation between CNN and GLASS products: (a) Spatial distribution of CNN-estimated net radiation; (b) Spatial distribution of GLASS net radiation product; (c) Scatter plot comparison of CNN simulations and GLASS products against in situ observations.

These findings are further supported by validation against 653 daily mean surface net radiation observations, which were selected to match the temporal period of the mapping output (1–30 September 2014) (Figure 9c). The CNN simulation achieved a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.935, a root mean square error (RMSE) of 9.93 W/m2, and a mean bias error (MBE) of −0.72 W/m2. In comparison, the GLASS product yielded an R2 of 0.816, an RMSE of 21.28 W/m2, and an MBE of −1.54 W/m2. Regression analysis shows that the CNN model exhibited a regression slope closer to 1, with a slight systematic deviation in the estimated values. In contrast, the GLASS product showed a steeper slope around 1.43, indicating a tendency to overestimate both high and low radiation values. These results indicate that the CNN model provides more balanced and consistent estimates across the full dynamic range of surface net radiation.

Overall, the CNN model demonstrated greater reliability and spatial applicability in regions with complex terrain. It effectively reproduced the spatial distribution patterns of surface net radiation while maintaining close agreement with in situ measurements. The integration of deep learning techniques thus offers a promising approach for improving the spatial accuracy of surface radiation flux mapping and contributes to more reliable assessments of regional energy balance and plateau climate processes.

4. Discussion

SHAP analysis revealed that Earth’s orbital mechanics and local topography exert dominant control over the spatial distribution and seasonal evolution of diurnal across the Tibetan Plateau [,]. Astronomical and geometric parameters—including Sun–Earth distance, solar hour angle, solar declination, and elevation—collectively contribute approximately 70% of the model’s explanatory power, aligning with established principles of solar radiation physics [,]. Under equivalent incoming radiation conditions, surface properties—particularly albedo, vegetation status, and temperature—modulate , accounting for an additional 25% of influence [,]. Surface albedo emerged as the dominant regulator in snow-covered and high-altitude glacial regions, while land surface temperature and NDVI jointly govern surface energy partitioning.

The deep learning model demonstrates successful internalization of radiative transfer physics, as evidenced by the fundamental reorganization of feature importance across temporal scales. Whereas aerosols and clouds dominate at instantaneous scales, their influence substantially diminishes at diurnal resolutions, giving way to quasi-static determinants like orbital geometry and terrain. Critically, the robust performance of the chosen CNN backbones is attributed to leveraging advanced architectural topology for channel-wise feature learning. By utilizing the 1 × 1 × 21 channel-rich input, the convolutional filters primarily performed pointwise convolution [], effectively learning the hierarchical nonlinear interactions among the 21 heterogeneous surface variables. The architectural advantages of these backbones—such as residual connections and dense skip connections []—are crucial for facilitating robust, deep feature abstraction across channels, a capability that is often lacking in standard Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs). This mechanism enabled the architecture to model complex physical relationships more effectively than conventional shallow regression models. While SHAP analysis effectively quantifies individual feature contributions [], it cannot directly elucidate variable interaction mechanisms or energy transfer pathways. Furthermore, although diurnal averaging smooths transient fluctuations, it may obscure cumulative effects arising from intraday nonlinearities. Future work should extend to sub-diurnal resolutions to clarify impacts of transient radiative processes and dynamic cloud fields, while developing hybrid modeling approaches that integrate physical constraints to enhance interpretability.

The observed slight regression toward the mean under extremely thick cloud cover or highly heterogeneous illumination can be attributed to a combination of factors inherent to the model’s design and training. Primarily, the L2 regularization applied during training penalizes large weights, thereby discouraging the complex mappings required to predict rare extreme values and biasing predictions toward the safer central tendency of the data distribution. This effect is synergistically amplified by the CNN architecture’s inherent tendency, through mechanisms like global average pooling (GAP) in the regression head, to prioritize learning broadly representative features over fitting localized extremes. Furthermore, the inherent statistical under-representation of extreme radiative conditions in the training data means that the model receives a stronger signal for the more frequent moderate scenarios. Independent validation confirmed robust model performance under all-weather conditions (R2 > 0.90), producing stable and reproducible results. Although slight regression toward the mean occurred under extremely thick cloud cover or highly heterogeneous illumination, the bias structure remained stable and accuracy degradation manageable. This indicates the model has learned inherent nonlinear relationships in radiative transfer processes rather than simply memorizing training samples [,]. While data scarcity in glacier and lake regions challenges model reliability, incorporating surface albedo and NDSI significantly reduced simulation errors over high-albedo regions.

The pixel-based regression approach effectively captures spatial heterogeneity induced by rugged topography, avoiding artefacts common in large-area masking procedures. The pixel-based multivariate regression approach, implemented via the 1 × 1 × 21 input tensor, is central to our method’s operational strength. By incorporating engineered spatial metrics directly into the channels, we statistically account for spatial context. This design effectively captures spatial heterogeneity induced by rugged topography and, crucially, avoids the mosaic and boundary artifacts common in traditional large-patch-based CNN approaches [], thereby ensuring seamless spatial continuity in the final product.

In the systematic evaluation of 19 CNN architectures, Xception achieved an optimal balance between accuracy (R2 > 0.94), interpretability, and computational efficiency. Xception’s superior performance is attributed to its efficient architecture based on depthwise separable convolutions, which significantly reduces computational cost and parameter count compared to fully connected convolution blocks. Training required merely 60 min—significantly faster than complex frameworks like DenseNet201—while generating daily 1 km resolution albedo maps for the Tibetan Plateau took only 15 min, demonstrating strong suitability for the operational production of long-term products. Improved reconciliation between in situ observations and remote sensing pixels remains crucial for further error reduction. Scale-induced errors from mixed pixels persisted even at 1 km resolution, challenging accurate characterization of pixel-average values from point measurements []. Linear regressions between most in situ observations and corresponding pixels achieved R2 > 0.7, while integrating NDVI and land surface temperature enabled the effective capture of surface heterogeneity. Fundamentally resolving scale discrepancies will require data fusion or sub-pixel decomposition using high-resolution imagery from Sentinel-2 or PlanetScope to better represent mixed pixels and constrain model estimates [].

Comparative analysis with the GLASS product demonstrates the CNN model’s superior performance in complex terrain and under extreme radiative conditions. GLASS’s observed overestimation and spatial detail smoothing reflect inherent limitations of its inversion algorithm in extreme plateau environments [,], underscoring how output quality fundamentally depends on input data accuracy and consistency. Notably, preprocessing foundational data proved more time-consuming than model construction, with the acquisition of high-quality MODIS reflectances, AOD, and CWV data requiring substantial high-performance computing resources. The considerable challenges encountered in securing merely one month of high-quality data (September 2014) highlight that producing decadal-scale, daily, kilometer-resolution products will necessarily depend on highly automated processing chains and robust high-performance computing support [].

Looking ahead, several challenges point to meaningful directions for future work. First, the framework relies on continuous and high-quality satellite data, underscoring the importance of developing more robust and harmonized preprocessing pipelines. Second, the use of diurnal averaging inherently smooths out short-term aerosol–cloud–radiation interactions, motivating future experiments at sub-daily or multi-scale temporal resolutions. Third, scale mismatch and mixed pixels continue to be major sources of uncertainty; these could be alleviated through data fusion with higher-resolution optical imagery. Finally, embedding physical constraints—such as radiative transfer equations or energy balance principles—into deep learning models may improve interpretability and ensure physical consistency, especially under out of distribution scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a deep learning framework designed to estimate all-wave across the complex terrain of the Tibetan Plateau. By framing the problem as a pixel-wise multivariate regression task, the model leverages the hierarchical feature learning ability of CNN architectures, eliminating the need for conventional spatial sliding windows. Out of the 19 candidate networks tested, Xception performed best, striking an optimal trade off among prediction accuracy, computational cost, and physical consistency. Its depthwise separable convolution structure capably models nonlinear cross channel relationships within the 1 × 1 × 21 input format, while the high channel count, together with engineered spatial descriptors, maintains smooth spatial continuity and reduces artifacts typically introduced by patch-based methods.

Interpretability analysis using SHAP confirmed that the model aligns well with radiative transfer theory: astronomical and topographic factors dominate distribution, whereas land surface properties—such as albedo, vegetation condition, and temperature—act as primary modulators under similar radiative forcing. Comparisons with the GLASS product highlight the framework’s improved performance in rugged terrain and under extreme radiative conditions. In summary, this work offers an accurate, computationally efficient, and physically coherent method for generating high-resolution datasets over the Tibetan Plateau. It can thereby support long-term energy balance monitoring and regional climate studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M., Y.M. and W.M.; methodology, B.M.; software, B.M.; validation, B.M.; formal analysis, B.M.; investigation, B.M.; resources, B.M., Y.M. and W.M.; data curation, B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M.; writing—review and editing, B.M. and Y.M.; visualization, B.M.; supervision, B.M.; project administration, B.M. and Y.M.; funding acquisition, Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 42405093, 42230610, U2242208].

Data Availability Statement

The in situ observed daily data were obtained from multiple comprehensive observation networks, including the TPE Integrated Three-dimensional Observation and Research Platform (TPEITORP) (https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.300977 (accessed on 1 May 2025), https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Meteoro.tpdc.270910 (accessed on 1 May 2025)), the upper reaches of the Heihe River Basin (HRB) (https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.301233 (accessed on 10 May 2025)), the Integrated Monitoring Dataset of Permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau (https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Geocry.tpdc.271107 (accessed on 10 May 2025)), the Alpine Semi-Arid Grassland and Lake Underlying Surface Process Observation Dataset in the Source Region of the Yellow River (SRYR) (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.07048 (accessed on 15 May 2025)), the Cold and Arid Region Network of Lanzhou University (CARN; https://mcs.lzu.edu.cn/), and the China Terrestrial Ecosystem Flux Research Network (ChinaFLUX; http://www.chinaflux.org/). Due to institutional data policies, these station-based data are not publicly available but can be requested from the respective data providers for research purposes. The multi-source remote sensing data used in this study are publicly available and were obtained from the following sources: MOD09GA and MYD09GA surface reflectance products from NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/); MCD19A2 aerosol optical depth and atmospheric water vapor content products (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/); MOD10A1F and MYD10A1F daily snow cover products (https://nsidc.org/); SRTM15 + V2.0 digital elevation model (https://www.usgs.gov/); MOD11A1 and MYD11A1 land surface temperature products (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Menenti, M.; Feddes, R.A.; Holtslag, A.A.M. A remote sensing surface energy balance algorithm for land (SEBAL)—1. Formulation. J. Hydrol. 1998, 212, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaersgaard, J.H.; Cuenca, R.H.; Plauborg, F.L.; Hansen, S. Long-term comparisons of net radiation calculation schemes. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2007, 123, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Choi, M.; Lee, S.; Seo, J. Estimation of instantaneous and daily net radiation from MODIS data under clear sky conditions: A case study in East Asia. Irrig. Sci. 2013, 31, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Liang, S.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Jia, K.; Yao, Y.; Jia, A. GLASS daytime all-wave net radiation product: Algorithm development and preliminary validation. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liang, S.; He, T.; Shi, Q. Estimation of daily surface shortwave net radiation from the combined modis data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 5519–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.H.; Li, Z.L.; Wu, H. Estimation of daily net surface shortwave radiation from modis data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 26–31 July 2015; pp. 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Jiang, B.; Liang, S.; Li, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Han, J.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Significant discrepancies of land surface daily net radiation among ten remotely sensed and reanalysis products. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 3725–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharekhan, D.; Nigam, R.; Bhattacharya, B.K.; Desai, D.; Patel, P. Estimating regional-scale daytime net surface radiation in cloudless skies from GEO-LEO satellite observations using data fusion approach. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 131, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Bai, P.; Yang, Z.L. CHiRAD: A high-resolution daily net radiation dataset for China generated using meteorological and albedo data. J. Hydrol. 2025, 654, 132854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, D.; Trigo, I.; Dutra, E.; Ermida, S.; Ghent, D.; Hulsman, P.; Gómez-Dans, J.; Miralles, D.G. High-resolution (1 km) all-sky net radiation over Europe enabled by the merging of land surface temperature retrievals from geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 567–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, L.F.; Fu, Z. Estimating net radiation flux in the Tibetan Plateau by assimilating MODIS LST products with an ensemble Kalman filter and particle filter. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Singal, G.; Saha, S.; Mittal, H.; Srivastava, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Mahato, S.; Saikia, B.; Thakur, S.; Samanta, S.; et al. Machine learning approach to predict net radiation over crop surfaces from global solar radiation and canopy temperature data. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; He, Q.; Zhu, L.; Yu, M.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, M. A cross-resolution surface net radiative inversion based on transfer learning methods. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, B.; Liang, S.; Peng, J.; Liang, H.; Han, J.; Yin, X.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, J.; et al. Evaluation of nine machine learning methods for estimating daily land surface radiation budget from MODIS satellite data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 1784–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Gao, Y.C.; Singh, V.P. Estimation of daily average net radiation from MODIS data and DEM over the Baiyangdian watershed in North China for clear sky days. J. Hydrol. 2010, 388, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yan, G.; Mu, X.; Jiao, Z.; Chen, L.; Chu, Q. Clear sky net surface radiative fluxes over rugged terrain from satellite measurements. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2011; pp. 4265–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.L.; Liou, K.N.; Wang, C.C. Impact of 3-D topography on surface radiation budget over the Tibetan Plateau. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2013, 113, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; He, T.; Jiang, B.; Liang, S. Estimation of all-sky all-wave daily net radiation at high latitudes from MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 245, 111842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roupioz, L.; Jia, L.; Nerry, F.; Menenti, M. Estimation of daily solar radiation budget at kilometer resolution over the Tibetan Plateau by integrating MODIS data products and a DEM. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.M.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zhang, L.L. Validation and spatiotemporal analysis of surface net radiation from cra/land and era5-land over the Tibetan Plateau. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbois, H.; Saint-Drenan, Y.-M.; Becquet, V.; Thiery, A.; Blanc, P. Retrieval of surface solar irradiance from satellite imagery using machine learning: Pitfalls and perspectives. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2023, 16, 4165–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lu, N.; Qin, J.; Tang, W.; Yao, L. A deep learning algorithm to estimate hourly global solar radiation from geostationary satellite data. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 114, 109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Yang, K.; Tang, W.; He, J. Convolutional neural network-based homogenization for constructing a long-term global surface solar radiation dataset. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yao, T.; Zhong, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, X.; Hu, Z.; Ma, W.; Sun, F.; Han, C.; Li, M.; et al. Comprehensive study of energy and water exchange over the Tibetan Plateau: A review and perspective: From GAME/Tibet and CAMP/Tibet to TORP, TPEORP, and TPEITORP. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 237, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hu, Z.; Xie, Z.; Ma, W.; Wang, B.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Zhong, L.; Sun, F.; Gu, L.; et al. A long-term (2005–2016) dataset of hourly integrated land-atmosphere interaction observations on the Tibetan Plateau. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 2937–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, T.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Tan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Xiao, L.; Deng, J.; et al. Integrated hydrometeorological, snow and frozen-ground observations in the alpine region of the Heihe River Basin, China. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Che, T.; Xu, Z.; Shang, L.; He, X.; Meng, X.; Ma, W.; et al. Dataset of spatially extensive long-term quality-assured land-atmosphere interactions over the Tibetan Plateau. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 3017–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zou, D.; Hu, G.; Wu, T.; Du, E.; Liu, G.; Xiao, Y.; Li, R.; Pang, Q.; Qiao, Y.; et al. A synthesis dataset of permafrost thermal state for the Qinghai-Tibet (Xizang) Plateau, China. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4207–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lyu, S.; Li, Z.; Ao, Y.; Wen, L.; Shang, L.; Wang, S.; Deng, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; et al. Dataset of Comparative observations for land surface processes over the semi-arid alpine grassland against alpine lakes in the source region of the Yellow River. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 40, 1142–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Lyu, S.; Ao, Y.; Luo, S.; Wen, L.; Zhao, L.; et al. A 10-year dataset of land surface observations for the semi-humid alpine grassland in the source region of the Yellow River. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 42, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evett, S.R.; Prueger, J.H.; Tolk, J.A. Water and energy balances in the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum. In Handbook of Soil Sciences: Properties and Processes; Huang, P.M., Li, Y., Sumner, M.E., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.L.; Tang, B.H.; Wu, H.; Ren, H.; Yan, G.; Wan, Z.; Trigo, I.F.; Sobrino, J.A. Satellite-derived land surface temperature: Current status and perspectives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 131, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liang, S.; He, T.; Yu, Y.; Schaaf, C.; Wang, Z. Estimating daily mean land surface albedo from MODIS data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 4825–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Ding, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. TRIMS LST: A daily 1-km all-weather land surface temperature dataset for the Chinese landmass and surrounding areas (2000–2021). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 387–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyapustin, A.; Wang, Y. MODIS Multi-Angle Implementation of Atmospheric Correction (Maiac) Data User’s Guide; NASA: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2018; Volume 6, pp. 1–19.

- Wang, K.; Dickinson, R.E. Global atmospheric downward longwave radiation at the surface from ground–based observations, satellite retrievals, and reanalyses. Rev. Geophys. 2013, 51, 150–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A.; DiGirolamo, N.E.; Román, M.O. Evaluation of MODIS and VIIRS cloud-gap-filled snow-cover products for production of an Earth science data record. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 5227–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Ma, Y.; Ma, W.; Xie, Z.; Han, C.; Wang, B. Estimating the daily mean blue-sky land surface albedo on the Tibetan Plateau using convolutional neural network. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 2024, 17, 2431621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Menenti, M.; Jia, L.; Gao, B.; Zhao, F.; Cui, Y.; Xiong, X.; Liu, X.; Li, D. A scalable software package for time series reconstruction of remote sensing datasets on the Google Earth Engine platform. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements-FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 5; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998; Volume 300, p. D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.L.; Kindermans, P.-J.; Ying, C.; Le, Q.V. Don’t decay the learning rate, increase the batch size. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.00489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, D.; Luschi, C. Revisiting Small Batch Training for Deep Neural Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.07612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Taylor, G.; Goldstein, T. Visualizing the loss landscape of neural nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 6391–6401. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Z. Solar Energy Fundamentals and Modeling Techniques: Atmosphere, Environment, Climate Change and Renewable Energy; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wang, D.; He, T.; Yu, Y. Remote sensing of earth’s energy budget: Synthesis and review. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 2019, 12, 737–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Zhang, W.; Arshad, A. Regional distribution of net radiation over different ecohydrological land surfaces. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Liu, S.; Zhu, W.; Yan, N.; Xing, Q.; Tan, S. An improved approach for estimating daily net radiation over the Heihe River Basin. Sensors 2017, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Network in Network. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Gao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, C. A survey of remote sensing image classification based on CNNs. Big Earth Data 2019, 3, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhao, J. High-resolution remote sensing image classification method based on convolutional neural network and restricted conditional random field. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, Y.; Passe, U.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.; Asrar, G.R.; Li, Q.; Li, H. Improving estimation of diurnal land surface temperatures by integrating weather modeling with satellite observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 315, 114393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitraka, Z.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Kamarianakis, Y.; Partsinevelos, P.; Tsouchlaraki, A. Improving the estimation of urban surface emissivity based on sub-pixel classification of high resolution satellite imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Cheng, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, X. Global Land Surface Satellite (Glass) Products: Algorithms, Validation and Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, Y.; Yan, J.; Chang, V.; Zomaya, A.Y. pipsCloud: High performance cloud computing for remote sensing big data management and processing. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 78, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).