Optimization of Spatial Sampling in Satellite–UAV Integrated Remote Sensing: Rationale and Applications in Crop Monitoring

Highlights

- Layout configuration of satellite–UAV integrated remote sensing was transformed into a spatial sampling problem.

- An SSO (spatial sampling optimization) model was proposed.

- Sampling efficiency requires considering both cost and accuracy.

- The SSO-optimized plan improved efficiency by at least 38.7% over conventional plans.

Abstract

1. Introduction

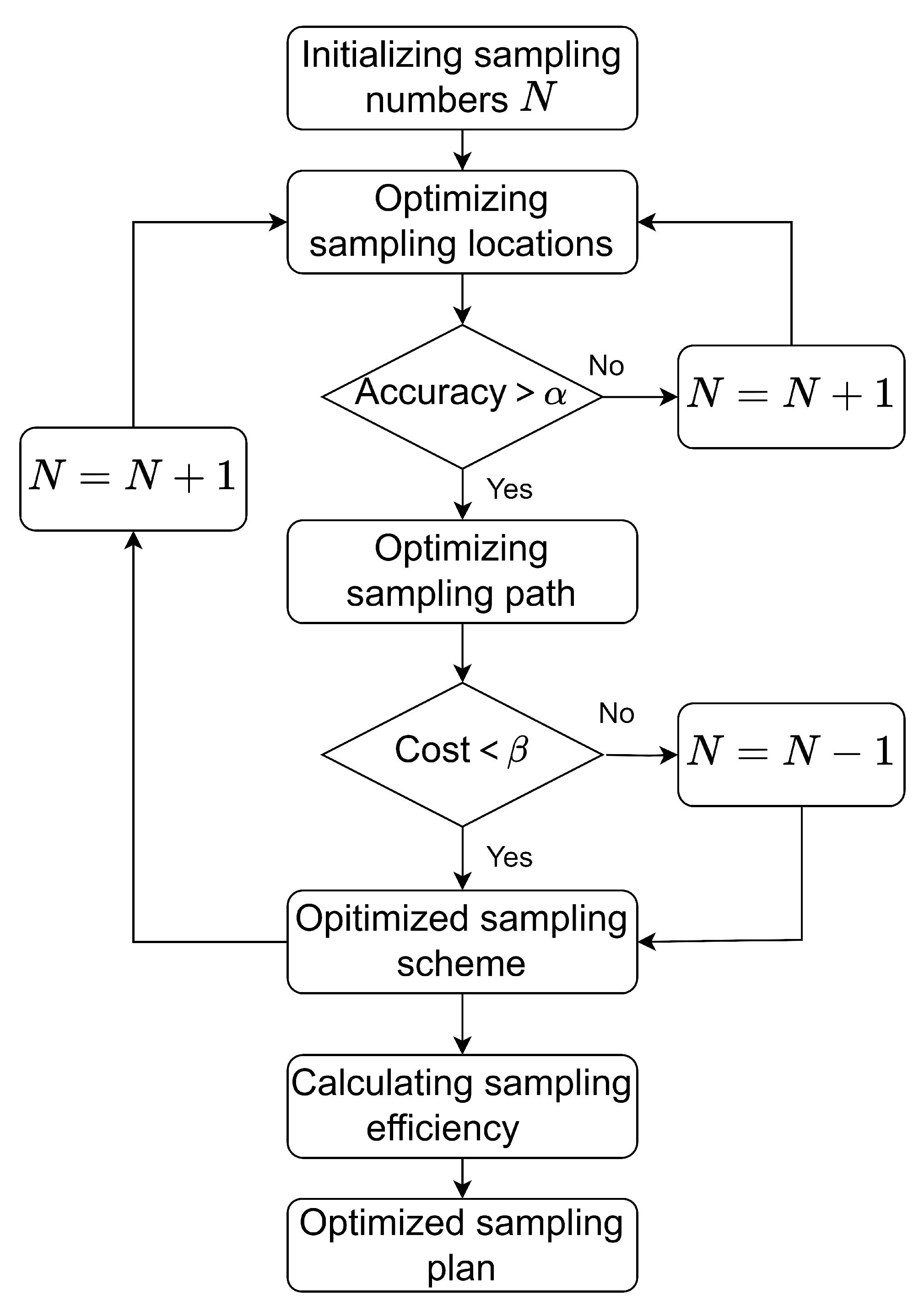

2. Spatial Sampling Optimization Model

2.1. Problem Formulation

2.2. Assumptions

- The UAV sampling frame was fixed at m. Each sampling point required 5 s to complete, and the UAV could operate continuously for 25 min (1500 s) on a single battery charge without replacement during the entire sampling process. These parameters were determined based on actual flight tests and the study area characteristics.

- The UAV flight speed was fixed at 6 m/s, which meets the minimum cruising speed requirement for multirotor UAVs specified in the Chinese national standard GB/T 39612-2020 [22].

- Instrument reuse precluded exact cost calculation; thus, sampling cost was proxied by total time, with accuracy evaluated via sampling error per conventional practice.

2.3. Model Establishment

2.3.1. Objective Function

2.3.2. Constraints

2.3.3. Solution Assessment

2.4. Solution Algorithm

3. Materials and Methods

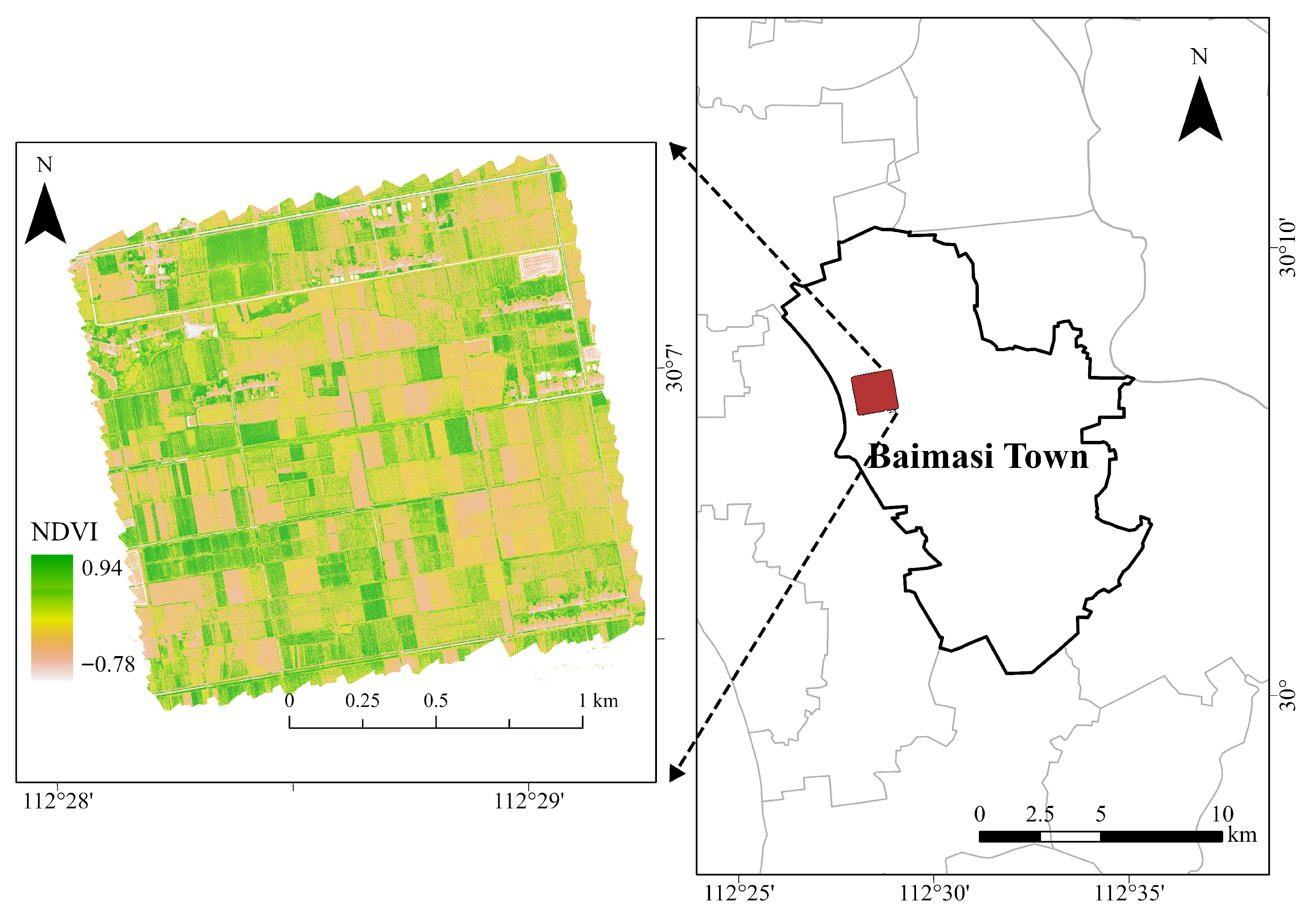

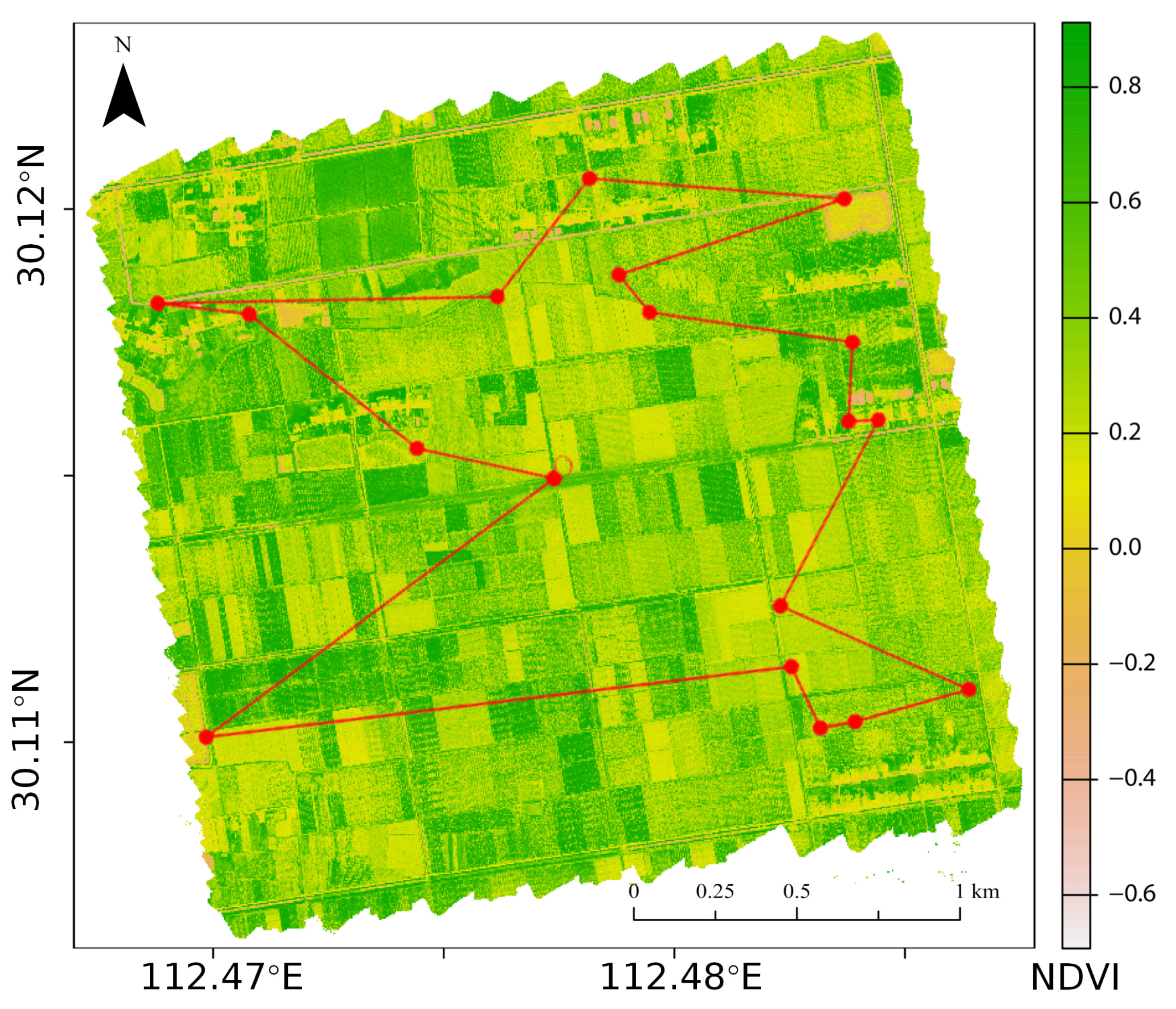

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Satellite Image Data

3.3. UAV Image Data

3.4. Assessment of the SSO Model

4. Results

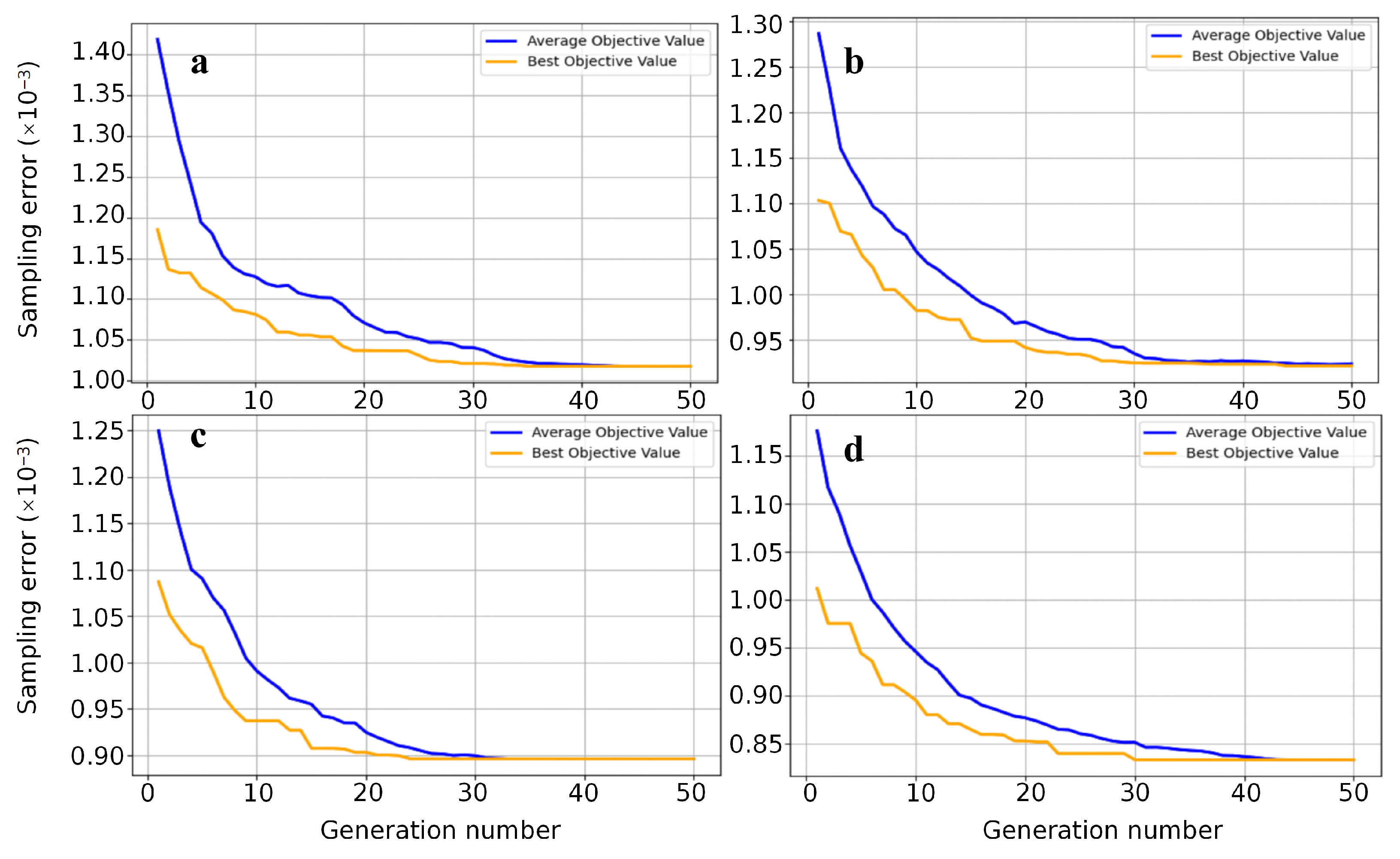

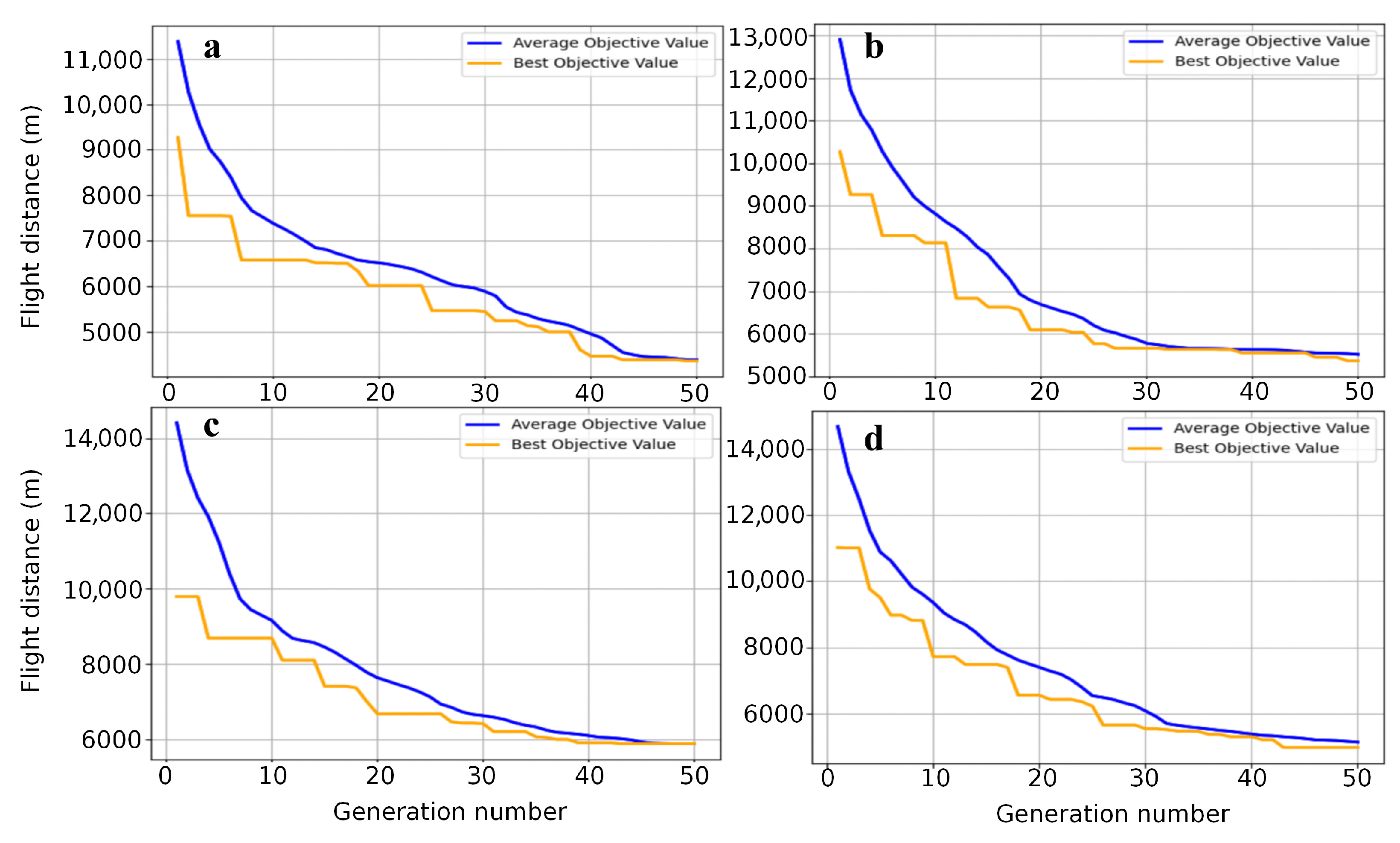

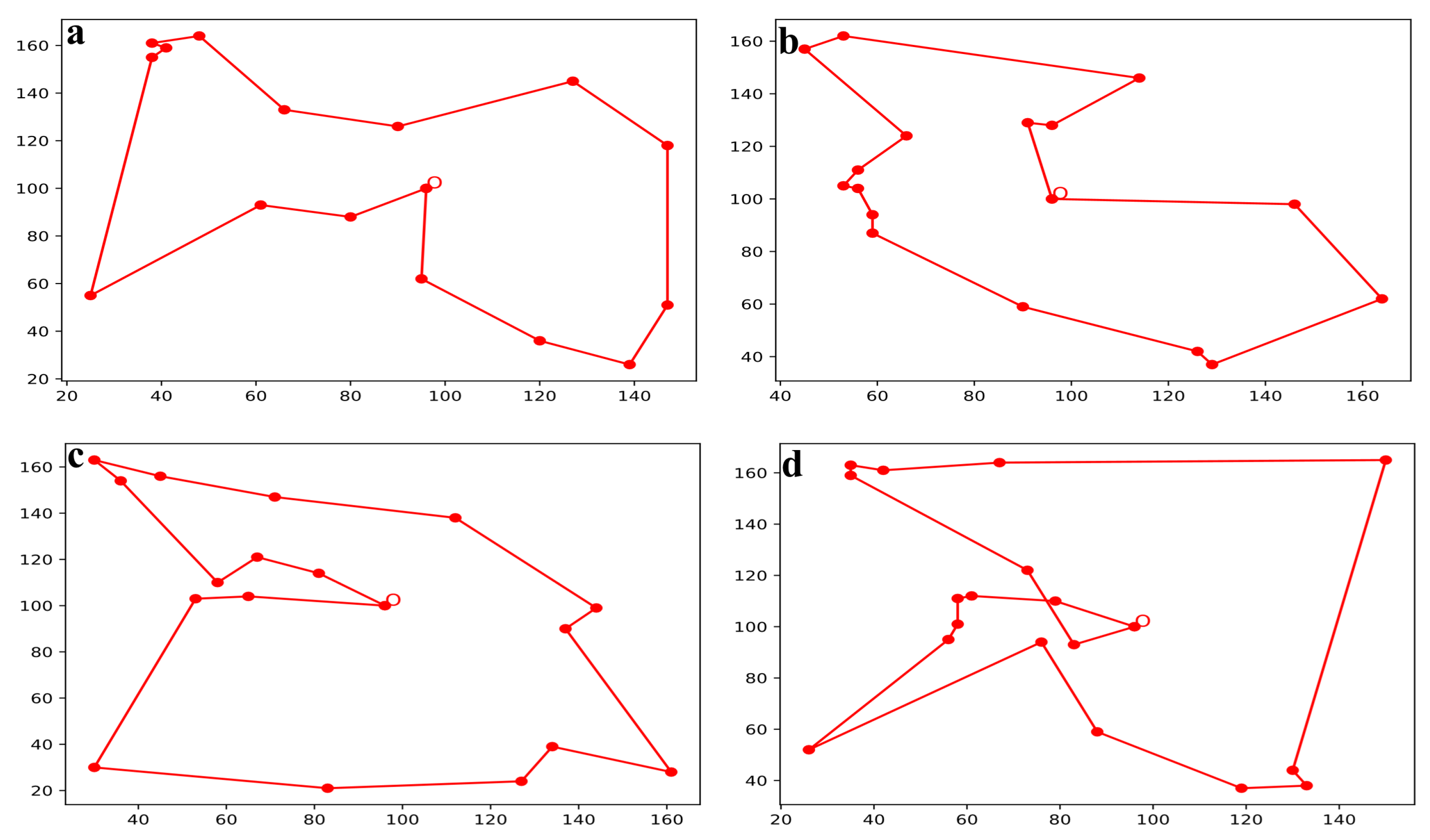

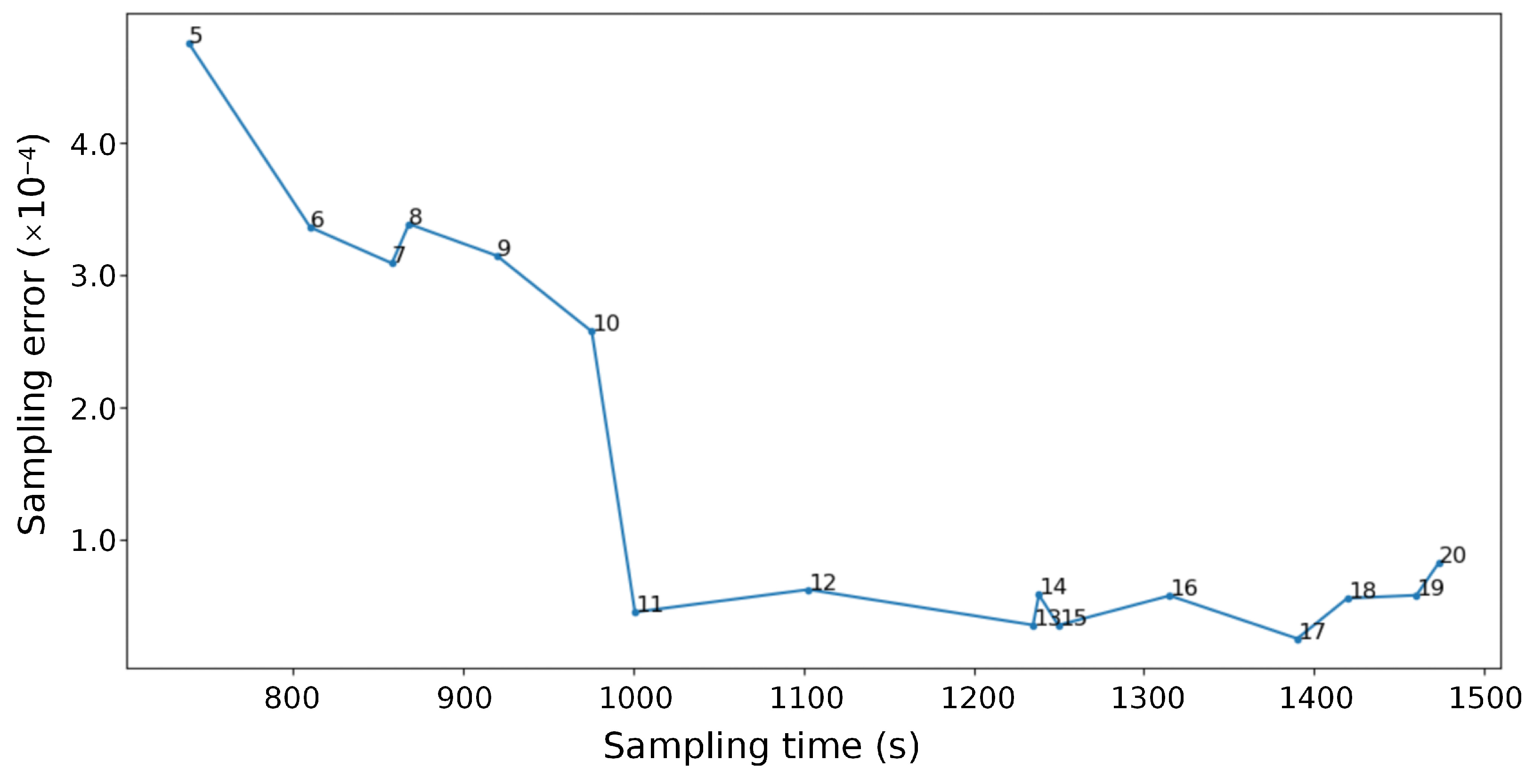

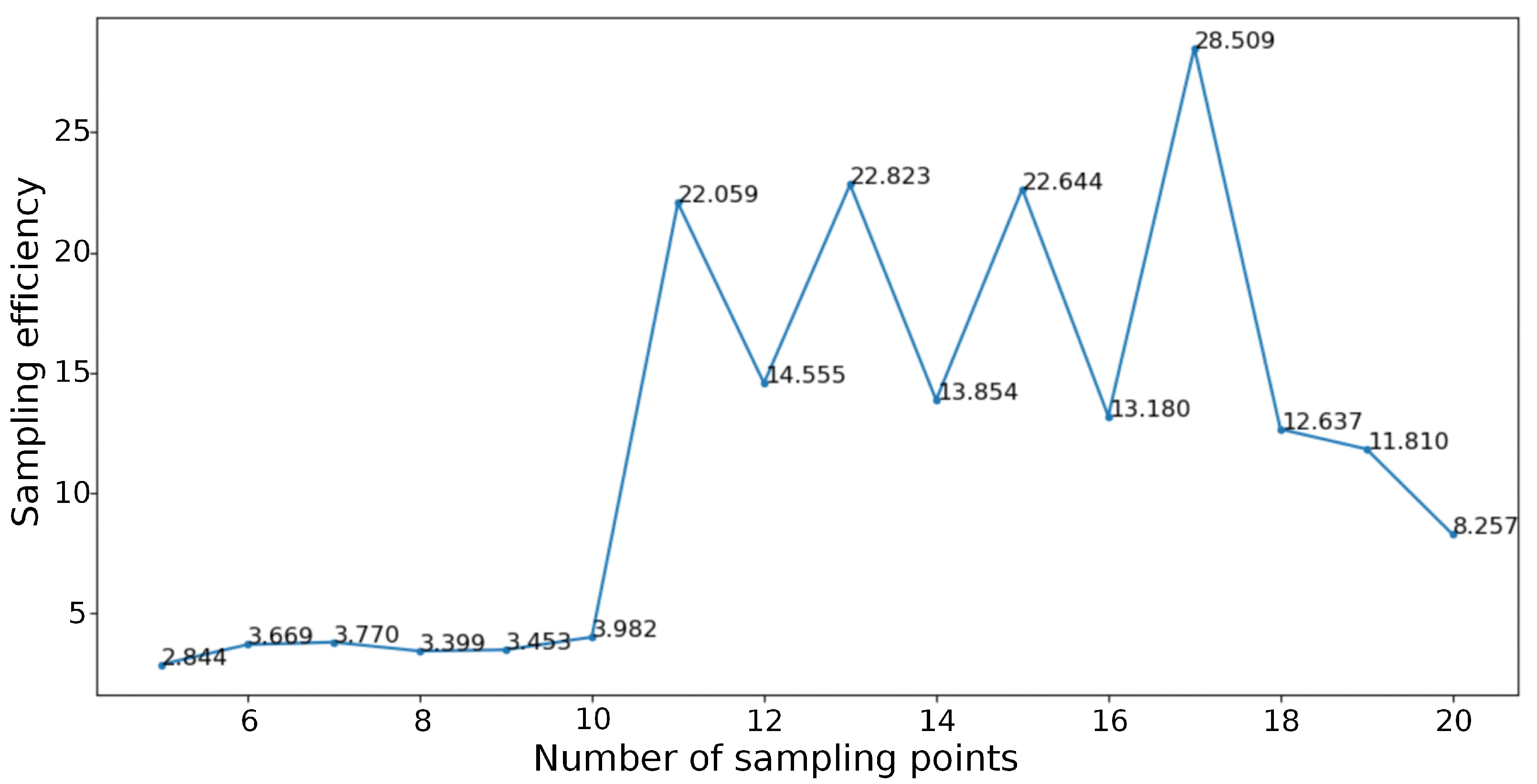

4.1. Sampling Optimization

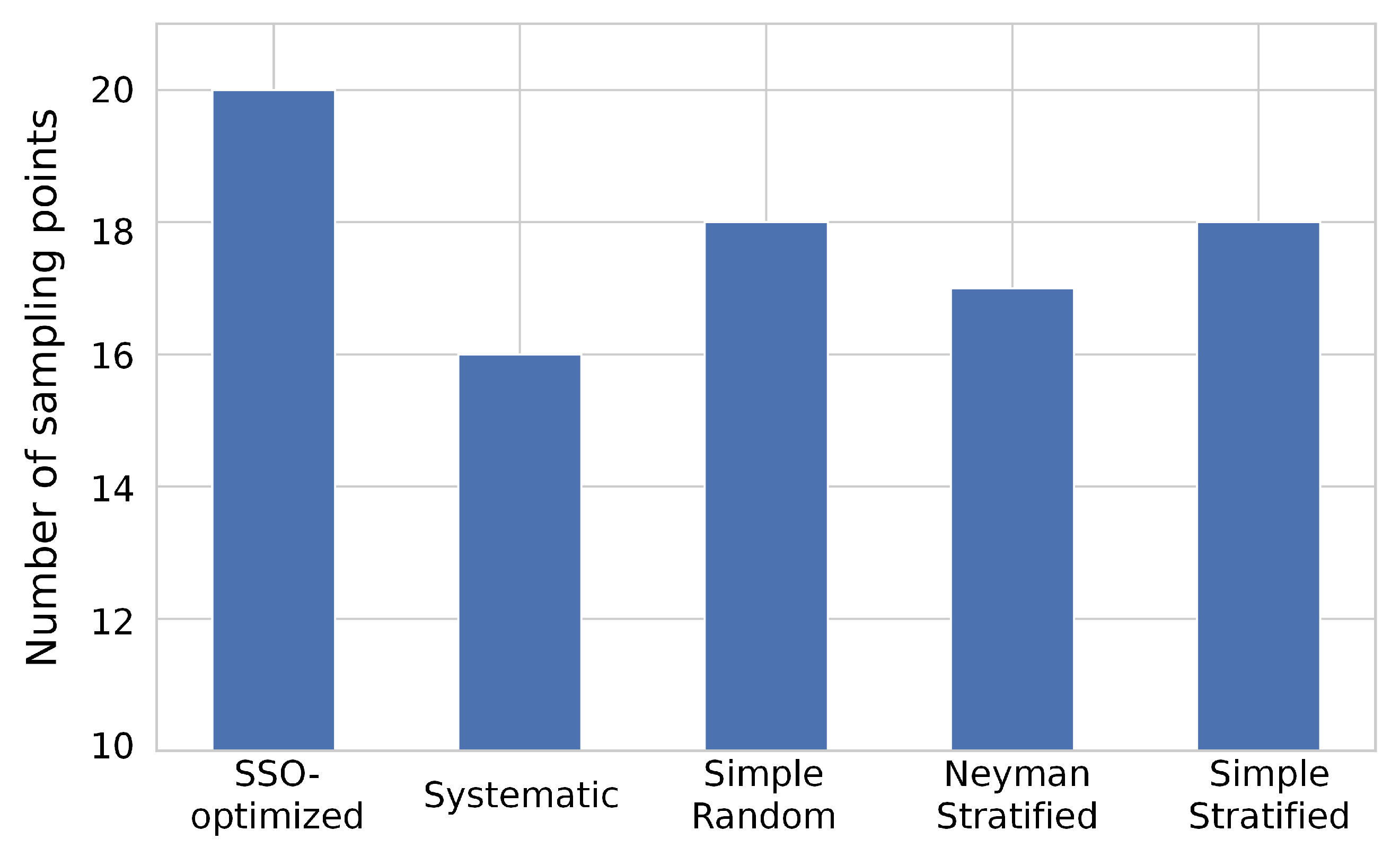

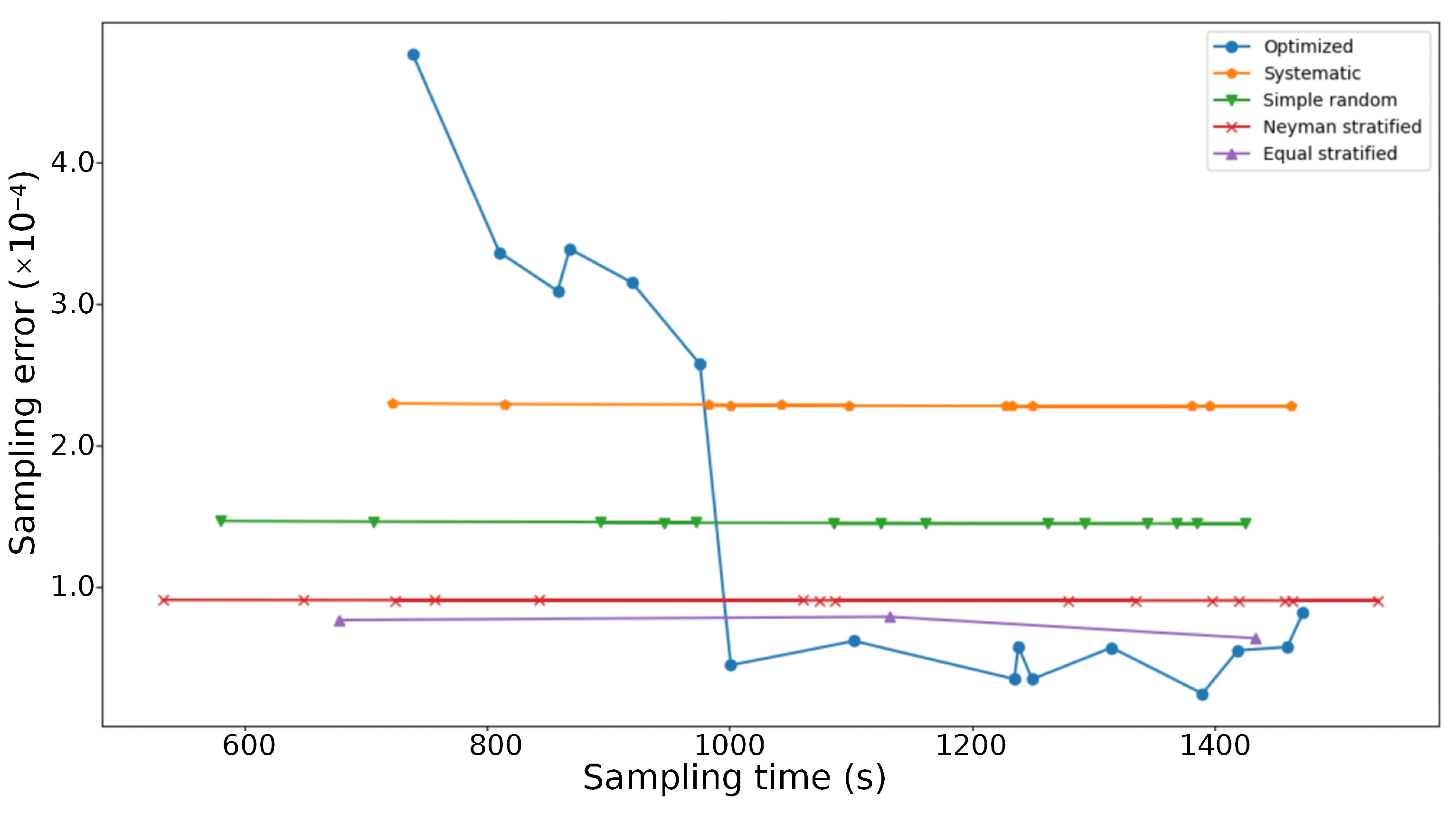

4.2. Comparison of Sampling Methods

4.2.1. Maximum Number of Sampling Points

4.2.2. Cost and Accuracy

4.2.3. SSO-Optimized Plan

5. Discussion

5.1. The Unique Value of EGA in Solving SSO Model

5.2. SSO Model Improved the Sampling Efficiency

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

- The SSO model can improve the efficiency of observations by optimizing the sampling design. Under the same cost constraint, the SSO model increased the number of sampling points by at least 11.1% and the sampling efficiency was at least 38.7% higher than the conventional sampling plans.

- The heuristic algorithm helps to solve the multi-objective optimization problem. The EGA can efficiently solve the SSO model optimally. The average sampling error of the final SSO-optimized plan was reduced by about 27.3%, and the sampling distance was shortened by 7000 to 8000 m.

- The problem of optimizing the layout of satellite remote sensing and UAV-based remote sensing can be transformed into a spatial sampling problem. It is necessary to consider cost constraints and increase efficiency by applying optimization methods in agricultural monitoring and government census in the future.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicles |

| EGA | Elite genetic algorithm |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| SSO | Spatial sampling optimization |

| TSP | Traveling salesman problem |

References

- Ghamisi, P.; Rasti, B.; Yokoya, N.; Wang, Q.; Hofle, B.; Bruzzone, L.; Bovolo, F.; Chi, M.; Anders, K.; Gloaguen, R.; et al. Multisource and Multitemporal Data Fusion in Remote Sensing: A Comprehensive Review of the State of the Art. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2019, 7, 6–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, N.; Weng, W.; Peng, D.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Z. Development and Evaluation of Remote Sensing-Derived Relative Growth Rate (RGR) for Rice Yield Estimation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 25735–25747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Vanhard, E.; Corpetti, T.; Houet, T. UAV & Satellite Synergies for Optical Remote Sensing Applications: A Literature Review. Sci. Remote Sens. 2021, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattenborn, T.; Lopatin, J.; Förster, M.; Braun, A.C.; Fassnacht, F.E. UAV Data as Alternative to Field Sampling to Map Woody Invasive Species Based on Combined Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 227, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Sam, L.; Akanksha; Martín-Torres, F.J.; Kumar, R. UAVs as Remote Sensing Platform in Glaciology: Present Applications and Future Prospects. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 175, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Vanhard, E.; Houet, T.; Mony, C.; Lecoq, L.; Corpetti, T. Can UAVs Fill the Gap Between In Situ Surveys and Satellites for Habitat Mapping? Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 243, 111780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, C.M.; Suomalainen, J.; Tang, J.; Kooistra, L. Generation of Spectral–Temporal Response Surfaces by Combining Multispectral Satellite and Hyperspectral UAV Imagery for Precision Agriculture Applications. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 3140–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafkan, A.; Igathinathane, C.; Bandillo, N.; Flores, P. Optimizing Integration Techniques for UAS and Satellite Image Data in Precision Agriculture—A Review. Front. Remote Sens. 2025, 6, 1622884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzer, C.; Dech, S.; Wagner, W. Remote Sensing Time Series Revealing Land Surface Dynamics: Status Quo and the Pathway Ahead. In Remote Sensing Time Series: Revealing Land Surface Dynamics; Kuenzer, C., Dech, S., Wagner, W., Eds.; Remote Sensing and Digital Image Processing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Stein, A.; Gao, B.B.; Ge, Y. A Review of Spatial Sampling. Spatial Stat. 2012, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.L., Jr.; Olsen, A.R. Spatially Balanced Sampling of Natural Resources. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004, 99, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, J.; Huang, R.; Weng, W.; Liang, G.; Zhou, C.; Shao, Q.; Tian, Q. The Illusion of Success: Test Set Disproportion Causes Inflated Accuracy in Remote Sensing Mapping Research. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 135, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.; Harrison, A.R. Two-Dimensional Systematic Sampling of Land Use. J. R. Stat. Soc. C (Appl. Stat.) 1993, 42, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.; Feng, Y.; Gong, Y.; Han, W.; Zhang, H.; Tong, X. Fractal Theory Based Stratified Sampling for Quality Assessment of Remote-Sensing-Derived Geospatial Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 7100–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Christakos, G.; Hu, M.G. Modeling Spatial Means of Surfaces with Stratified Nonhomogeneity. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 4167–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, S.; Xu, D.; Hong, Y.; Li, S.; Peng, J.; Ji, W.; Guo, X.; Zhao, X.; Shi, Z. Strategies for Predicting Soil Organic Matter in the Field Using the Chinese Vis-NIR Soil Spectral Library. Geoderma 2023, 433, 116461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Liao, R.; Meng, R.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Ye, S. Strategic Sampling for Training a Semantic Segmentation Model in Operational Mapping: Case Studies on Cropland Parcel Extraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 331, 115034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, L. A Review on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing: Platforms, Sensors, Data Processing Methods, and Applications. Drones 2023, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Qin, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Song, D. AoI Analysis of Satellite–UAV Synergy Real-Time Remote Sensing System. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ji, F.; Wang, Y.; Yao, K.; Chen, F. Space–Air–Ground–Sea Integrated Network with Federated Learning. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haining, R. Spatial Data Analysis: Theory and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 39612-2020; Specifications for Low-Altitude Digital Aerial Photography and Data Processing. Ministry of Natural Resources, People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Lyu, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, T.; Pan, Q. UAV Coverage Path Planning of Multiple Disconnected Regions Based on Cooperative Optimization Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2025, 17, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, T.S.; Kim, J.H. Efficient Nearest Neighbor Heuristic TSP Algorithms for Reducing Data Acquisition Latency of UAV Relay WSN. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2017, 95, 3271–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Wang, X. Hybrid Optimization Algorithm Based on Wolf Pack Search and Local Search for Solving Traveling Salesman Problem. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Sci.) 2019, 24, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, L.; Xu, B.; Yin, G.; Peng, J. A Sampling Strategy for Remotely Sensed LAI Product Validation over Heterogeneous Land Surfaces. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 3128–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Outline for a Logical Theory of Adaptive Systems. J. ACM 1962, 9, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, J. A Markov Chain Analysis on Simple Genetic Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1995, 25, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilin, V.; Simić, D.; Simić, S.D.; Simić, S.; Saulić, N.; Calvo-Rolle, J.L. A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm, List-Based Simulated Annealing Algorithm, and Different Heuristic Algorithms for the Travelling Salesman Problem. Log. J. IGPL 2023, 31, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeck, T.; Fogel, D.B.; Michalewicz, Z. (Eds.) Handbook of Evolutionary Computation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine Learning: Trends, Perspectives, and Prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A Review on Genetic Algorithm: Past, Present, and Future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Threshold for acceptable sampling accuracy | ||

| 1500 | Threshold for acceptable time cost | |

| Population size | 60 | Number of individuals per generation |

| Max generations | 50 | Termination condition of evolution |

| Mutation probability | 0.50 | Probability of mutation |

| Crossover rate | 0.70 | Probability of crossover |

| Convergence threshold | Criterion for stopping evolution | |

| Selection method | Tournament | Strategy for selecting parents |

| Mutation operator | Inversion | Reverses a random gene segment |

| Crossover operator | PMX | Partially matched crossover (permutation encoding) |

| Encoding type | Permutation | Suitable for route/layout optimization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Xiong, H.; Yu, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhang, J. Optimization of Spatial Sampling in Satellite–UAV Integrated Remote Sensing: Rationale and Applications in Crop Monitoring. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233895

Zhao Z, Xiong H, Yu Y, Xu B, Zhang J. Optimization of Spatial Sampling in Satellite–UAV Integrated Remote Sensing: Rationale and Applications in Crop Monitoring. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233895

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhen, Hang Xiong, Yawen Yu, Baodong Xu, and Jian Zhang. 2025. "Optimization of Spatial Sampling in Satellite–UAV Integrated Remote Sensing: Rationale and Applications in Crop Monitoring" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233895

APA StyleZhao, Z., Xiong, H., Yu, Y., Xu, B., & Zhang, J. (2025). Optimization of Spatial Sampling in Satellite–UAV Integrated Remote Sensing: Rationale and Applications in Crop Monitoring. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233895