Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The MSA-Mamba module is designed herein. By combining large-kernel convolution with a multi-directional structure-aware scanning strategy, it effectively captures local details and long-range spatial dependencies, significantly enhancing the modeling capability for multi-scale objects.

- The MCSA module is developed, which utilizes parallel convolution branches with different receptive fields to simultaneously model multi-granularity channel context information. This enhances semantic discriminative power and effectively alleviates feature confusion caused by similar textures or dense objects.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The MSA-Mamba and MCSA modules are integrated in parallel to construct a dual-branch FIBlock architecture, which realizes the joint context modeling of spatial structure and channel semantics and forms complementary advantages.

- Extensive experiments on the DOTA-v1.0, DOTA-v1.5 and HRSC2016 datasets show that FI-MambaNet outperforms various advanced methods in terms of mAP (mean Average Precision) while maintaining high computational efficiency, demonstrating its effectiveness and practicality.

Abstract

Remote sensing object detection (RSOD) faces challenges such as large variations in target scale, diverse orientations, and complex backgrounds. Existing approaches struggle to simultaneously balance local feature extraction and global context modeling, while also failing to capture fine-grained semantic information across channel dimensions. To address these issues, we propose a novel remote sensing object detection backbone network, FI-MambaNet. Specifically, we design the Multi-Scale Architecture-Aware Mamba module, which combines multi-scale convolutions with multi-directional architecture-aware scanning strategies to capture both local details and long-range spatial correlations. Additionally, we introduce the Multi-granularity Contextual Self-Attention module, which employs multi-branch convolutions with varying receptive fields and strides. This simultaneously enhances semantic discrimination and models channel-level context. These modules enable efficient spatial–channel interactions within the FIBlock architecture. Extensive testing on the HRSC2016, DOTA-v1.0 and DOTA-v1.5 datasets demonstrates that FI-MambaNet achieves detection performance surpassing baseline methods while maintaining high computational efficiency. This validates its potential for handling multi-scale complex scenes in remote sensing object detection.

1. Introduction

Remote Sensing Object Detection (RSOD) is an important research area within computer vision [1,2,3], focused on accurately identifying and localizing objects of interest (e.g., aircraft, ships, vehicles) in aerial or satellite imagery. Compared to general object detection in natural images, remote sensing images often present unique challenges, including large variations in object scale, high spatial resolution, and complex background clutter. This results in objects within the imagery displaying significant diversity in scale, orientation, and density. In recent years, considerable research efforts have been devoted to the development of various Oriented Bounding Box (OBB) detectors [4,5,6] and enhancing the angular prediction accuracy of OBBs [7,8,9] to more precisely fit the true shapes of tilted or rotated objects. For instance, orientation detection frameworks such as RoI Transformer [10], Oriented R-CNN [11], and R3Det [12], combined with specific rotation loss functions such as KLD [8] and GWD [13], have successfully improved the accuracy of orientation regression and angle prediction. However, feature extraction has not been fully explored due to the unique properties of remote sensing images.

Remote sensing imagery primarily consists of high-resolution aerial photographs taken from a bird’s-eye view. Some studies use explicit data augmentation techniques [14,15,16] to learn feature representations that are more invariant to scale and background clutter, while others emphasize multi-scale feature integration [17,18] to capture rich contextual cues at different scales. However, most existing methods suffer from significant limitations—they typically rely on fixed receptive fields or simple feature pyramid structures for multi-scale modeling, which struggles to adequately adapt to the extreme scale and aspect ratio variations inherent in remote sensing imagery. CNN-based methods are limited by their local receptive fields, which complicates detection. While Transformers are not subject to this limitation, their high complexity significantly increases the detection cost, limiting their application in real-time scenarios.

Recent research has gradually introduced approaches to address the problem of insufficient context modeling of large-scale objects by adaptively expanding the spatial receptive field [19]. This approach is achieved by introducing large kernel convolutions and dilated convolutions into the backbone framework.To further enhance feature extraction flexibility, ALM-YOLOv8 [20] introduces a large-kernel separation attention mechanism to capture long-range dependencies under lightweight constraints, while Gaussian-based R-CNN [21] integrates large-selection kernels to dynamically adjust the receptive field based on target rotation and scale characteristics. Building on this strategy, PKINet [22] improves the design by adopting a parallelized multi-scale convolution structure, thereby improving the network’s robustness to handling different object scales. However, this approach also has drawbacks. The receptive field of the convolution is “fixed”, relying on a preset kernel size and dilation rate to capture spatial information. It cannot dynamically adjust the region of interest based on the input content, making it difficult to flexibly adapt to the feature distribution of objects of different scales and shapes. Furthermore, modeling long-range spatial dependencies typically requires stacking multiple convolutional layers or increasing the kernel size. This approach not only significantly increases the computational cost but also may distort the contextual semantics due to the over-expansion of the information propagation chain.

Fortunately, state-space models (SSMs) with selective scanning mechanisms have shown significant advantages in spatial modeling. In particular, Mamba [23] achieves lower computational complexity and higher long-range modeling capabilities. However, when applying SSMs—which inherently process one-dimensional sequences—to two-dimensional visual tasks, the core challenge lies in effectively preserving the inherent spatial structure of images. Although existing research has explored diverse scanning strategies to adapt to visual tasks, they often face common limitations. On one hand, forcibly arranging two-dimensional pixels into one-dimensional sequences inevitably distorts the spatial topological relationships between pixels. For example, vertically adjacent pixels in an image may become widely separated in the sequence, thereby compromising the effective modeling of spatial correlations. On the other hand, fixed, insufficiently comprehensive scanning paths (such as simple quadrilateral scanning) struggle to flexibly adapt to the complex variability of target morphology and spatial relationships in remote sensing imagery. Therefore, designing a scanning mechanism that preserves two-dimensional spatial neighborhood relationships while efficiently integrating contextual information—thereby better aligning with the intrinsic demands of visual tasks—remains a critical issue for improving SSM-based methods.

Meanwhile, at the feature channel dimension, enhancing semantic discriminative power is crucial for distinguishing between objects, particularly in challenging scenarios involving cluttered environments and textural ambiguities in remote sensing images. One approach (e.g., SENet [24]) aggregates channel information through global average pooling, then adaptively recalibrates channel features to highlight key channel information and enhance the network’s representational capacity. However, such channel interactions primarily rely on aggregating information within local receptive fields, making it difficult to establish broad channel semantic associations across scales and regional boundaries. When confronting multi-scale targets and diverse backgrounds in complex remote sensing scenarios, this limitation hinders models from effectively integrating semantic clues across different scales, thereby restricting their discrimination capabilities for target categories. Another class of models, represented by Transformers, can capture long-range dependencies but predominantly employs single-scale global correlation calculations at the channel level. For instance, in ViT [25] and its derivatives [26,27], the self-attention operation computes global dependencies uniformly across all channels, lacking the ability to capture channel context with precision and differentiation under varying receptive fields. This results in insufficient sensitivity to subtle semantic differences. When processing remote sensing targets with similar textures or spectral characteristics, feature confusion easily leads to false positives or false negatives. This confusion problem is further amplified in small object detection or low-contrast scenarios.

In remote sensing imagery, which contains rich multi-scale data and complex semantic information, designing a mechanism to precisely model channel context and effectively enhance channel-wise discriminability remains a critical unresolved issue.To overcome these challenges, we introduce FI-MambaNet, a flexible backbone architecture designed to address the inherent difficulties of remote sensing object detection, especially the significant variations in object scale and semantic representation.

In summary, the key contributions of this study can be outlined as follows:

- 1.

- To tackle the challenges posed by varying target scales and complex structures in remote sensing images, this work introduces the Multi-scale Structure-Aware Mamba (MSA-Mamba) module. By integrating multi-scale feature extraction with a multi-directional scanning strategy incorporating a normalized structure-aware state mechanism, this module significantly enhances the modeling capabilities for both local structures and global context in remote sensing images;

- 2.

- To further enhance information interaction and discrimination across channel dimen- sions, a Multi-granularity Contextual Self-Attention (MCSA) Block is designed. This block employs deep convolutional branches, each configured with a distinct kernel size and stride, to concurrently model multi-granularity channel contextual information, effectively mitigating confusion caused by abundant similar textures or dense targets in remote sensing images;

- 3.

- Our FI-MambaNet model delivers leading detection performance. When evaluated on the DOTA-v1.0, DOTA-v1.5 and HRSC2016 remote sensing benchmarks, the model strikes an excellent balance between accuracy and inference speed, underscoring its significant potential for real-world applications.

2. Related Works

In this section, we reviewed relevant work on object detection frameworks, state-space models, and attention mechanisms in the field of remote sensing.

2.1. Remote Sensing Object Detection

Detectors for remote sensing object detection are primarily based on CNN and Transformer architectures. CNN-based methods are divided into single-stage and two-stage frameworks, with the latter category proving particularly influential. Models like Oriented R-CNN [11] have inspired many variants in the R-CNN paradigm. For example, Ding et al. [10] utilized linear layers to rotate anchor candidate points in the first stage, enabling efficient intra-anchor feature extraction. Similarly, Xu and Xie [6,11] proposed improved bounding box encoding strategies that address angular periodicity and help stabilize training. In terms of feature extraction, LSKNet [19] achieves efficient feature extraction by designing large-scale convolutional kernels. However, using large-kernel convolutions may introduce significant background noise, hindering the accurate detection of small objects. PKINet [22] aggregates multi-scale information through multi-branch Inception-style convolutions and context anchor attention modules, yet lacks the capability for fine-grained channel context modeling. In contrast, single-stage detectors avoid predefined anchors by directly performing classification and regression on dense grid samples. Representative works include Han et al. [5], which strengthens feature representation through directional alignment, and Pan et al. [28], which integrates attention mechanisms into the backbone to improve feature learning. Concurrently, oriented bounding boxes (OBBs) were proposed to overcome the limitation of horizontal bounding boxes (HBBs) in accurately representing rotated objects. Early RRPN [29] improved coverage through rotated anchors, while subsequent approaches like RoI Transformer [10], R3Det [12], S2Anet [5] optimized feature alignment and proposal generation, ReDet [30] achieves rotation isometry. Gliding Vertex [6] and Oriented RepPoints [4] enhanced accuracy via sliding vertices and point set representations, respectively. However, this approach has relatively limited geometric expressiveness and is prone to boundary discontinuities during angular regression, particularly sensitive to small targets and those with extreme aspect ratios. Consequently, such methods still face performance bottlenecks in complex remote sensing scenarios. For transformer-based methods, Zeng et al. ARS-DETR [31] pioneered the application of DETR [32] to remote sensing object detection. AO2-DETR [33] introduced oriented proposals to enhance feature interactions, while FPNformer [34] combined FPN with Transformer decoders to capture multi-scale and rotation-aware features. Although these methods possess powerful global modeling capabilities, they often suffer from high computational overhead, difficulty in capturing local structural details, and insufficient sensitivity to multi-scale features in remote sensing scenarios. These approaches have driven breakthroughs in RSOD performance across both framework design and detailed modeling. However, most methods still struggle to balance multiscale feature extraction with the ability to model fine-grained contextual information. In contrast, the proposed FI-MambaNet significantly enhances multiscale feature extraction and contextual information modeling capabilities for remote sensing targets by integrating Mamba with multi-granularity self-attention.

2.2. State Space Model

In recent years, state space models (SSMs), including Mamba [23], have attracted considerable attention in both NLP and computer vision. They offer an effective alternative to transformers and CNNs due to their strong capability for modeling long-range dependencies and their inherent suitability for processing continuous signals. Early work like S4 [35] introduced an efficient linear state space modeling framework, significantly enhancing long sequence modeling capabilities. Subsequently, S5 [36] further improved modeling efficiency by incorporating multi-branch structures and segmented convolution strategies. Although originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), state space models (SSMs) have recently shown great promise in computer vision applications. Inspired by the pioneering Mamba framework, a series of Mamba-like models have been introduced for vision and remote sensing tasks. Examples include VMamba [37], RS3 Mamba [38], RSMamba [39] and MSFMamba [40], which extends Mamba to more complex scenarios. In addition, Change Mamba [41] leverages a Mamba-like encoder to model global spatial context for change detection. More recently, Zhu et al. [42] proposed an encoder architecture based on the Mamba design that efficiently extracts semantic information from remote sensing images. However, most of these methods are designed for global semantic modeling or scene-level representation, lacking the capability for fine-grained structural modeling of dense small objects. They remain limited in remote sensing object detection scenarios and cannot be directly applied to meet the stringent requirements for local texture, spatial continuity, and geometric sensitivity in remote sensing object detection. Concurrently, to adapt to visual tasks, related studies have progressively explored diverse scanning strategies, Zhu et al. [43] and Liu et al. [37] employ bidirectional and quad-path scanning strategies, respectively, to optimize spatial direction modeling.However, these simple row-column scans still result in spatial discontinuities at path junctions and fail to adequately account for local structural relationships between pixels, Yang et al. [44] address Sweeping scan’s neglect of spatial continuity by proposing sequential scanning to enhance integration of visual data induction biases; Huang et al. [45] argued that global scanning struggles to capture local spatial relationships effectively, thus designing LocalMamba. This approach divides images into multiple windows via local scanning patterns to strengthen modeling of local dependencies. Additionally, strategies like Hilbert scanning [46] and dynamic tree scanning [47] have been successively proposed, advancing SSM adaptation for visual tasks.However, these strategies lack the ability to perceive local texture structures and cannot adapt to the demands of dense small targets or fine-grained textures in complex remote sensing scenarios. The proposed MSA-Mamba method first extracts information at different scales through multi-scale feature extraction. It not only employs a more comprehensive multi-directional zigzag scanning approach to ensure spatial coverage, but more importantly incorporates a structure-aware state fusion mechanism to perceive the local spatial relationships between neighboring pixels in the image. This addresses the distortion issues caused by the limited receptive field and spatial discontinuity inherent in SSM during feature extraction.

2.3. Attention Mechanism

Attention mechanisms have emerged as an effective strategy for feature refinement and are now extensively employed in computer vision. Models like SENet [24], which are a prominent example of channel attention, leverage a global average pooling operation to adaptively reweight feature responses across different channels. In contrast, spatial attention [48,49,50] strengthen contextual modeling by generating spatial masks. However, its spatial weights often lack multi-scale characteristics, limiting its adaptability to remote sensing scenes with significant scale variations. To combine the benefits of both dimensions, hybrid designs such as CBAM [51] and BAM [52] integrate channel and spatial attention in a unified framework, yet their attention computation still relies on single-scale features, failing to differentiate modeling approaches for the non-uniform distribution of extensive background noise and densely clustered small targets in remote sensing imagery. To enhance efficiency, ECA-Net [53] proposed a local cross-channel interaction strategy that captures dependencies between channels without requiring dimensionality reduction. Subsequently, the introduction of Transformers [54] and their successful application in vision further demonstrated the powerful capabilities of self-attention.However, standard attention mechanisms are computationally expensive in remote sensing scenarios and lack sensitivity to small targets, making them susceptible to interference from large background areas. To enhance the flexibility and efficiency of Transformers, Dynamically Composable MHA [55], DFormerv2 [56], SCSA [57], and others enhance structural adaptability through dynamic graphs, geometric constraints, or sparse attention. However, they still primarily rely on single-scale inputs and lack discriminative modeling of features with different receptive fields. Swin Transformer [58] enhances local modeling capabilities through window partitioning and sliding mechanisms, yet its fixed window size struggles to fully adapt to the significant scale variations in remote sensing imagery. Furthermore, research has extended attention concepts to new dimensions and domains: Dynamic Layer Attention [59] focuses on enhancing interactions between different network layers rather than intra-layer information, while Gated Attention Coding [60] combines gating mechanisms with attention for training high-performance, efficient spiking neural networks. While these approaches strengthen cross-layer or cross-structural information exchange, they fail to model channel context from a multi-scale receptive field perspective. Consequently, they struggle to address common challenges in remote sensing scenarios, such as textural similarity, complex backgrounds, and small object confusion. This paper employs multi-branch, multi-stride convolutions to concurrently capture channel-level context within different receptive fields, effectively mitigating the feature confusion commonly observed in remote sensing imagery.

3. Methods

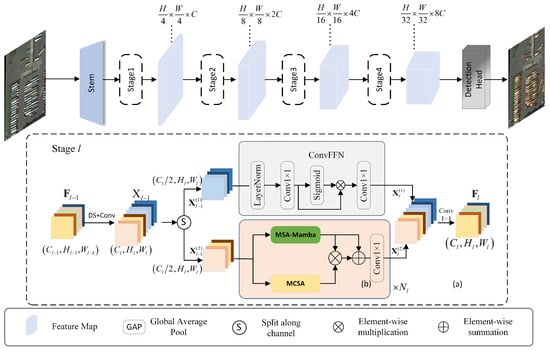

As shown in Figure 1, the backbone network constructed in this paper draws inspiration from classic architectures such as VGG [61] and ResNet [62], adopting a four-stage feature extraction framework. Each stage employs a Cross-Stage Partial (CSP) connection structure [63] to enhance feature utilization efficiency and information flow.

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of FI-MambaNet. This network comprises four cascaded stages, where (a) illustrates the internal structure of each stage, and (b) represents its core FIBlock.

At each stage, input features are split into two subpaths along the channel dimension: one path consists of a lightweight feed-forward network (FFN) for rapid capture of local semantic information; the other path comprises multiple serial feature integration blocks (FIBlocks, see Section 3.3). Each FIBlock module internally incorporates a parallel Multi-scale Structure-Aware Mamba (MSA-Mamba, see Section 3.1) and a Multi-scale Contextual Self-Attention (MCSA, see Section 3.2), enabling joint modeling of spatial structure and channel semantics.

This backbone network can be flexibly integrated into various oriented object detectors (e.g., Oriented RCNN [11]), enabling efficient and precise detection of ground objects in remote sensing images.

3.1. Multi-Scale Structure-Aware Mamba Block

Mamba effectively captures long-range dependencies between features. Traditional Mamba modules model state transitions and observations through one-dimensional sequences, but when processing data like images with two-dimensional spatial structures, issues arise such as spatial information distortion and long-path dependencies. Simultaneously, remote sensing images often feature objects with large size variations, diverse morphologies, and significant complex background interference, imposing dual demands on detection models: Strong multi-scale representation capabilities and the capacity to capture long-range spatial dependencies.Therefore, to address the difficulties presented by significant disparities in object size and complex backgrounds in remote sensing images, and to more effectively capture multi-scale spatial dependencies, we propose MSA-Mamba. As shown in Figure 2, this module combines large-core convolutions with batch fusion strategies to extract multi-scale texture features. It further incorporates a multi-directional scanning Mamba block with structure-aware capabilities to achieve joint modeling of local details and long-range dependencies.

Figure 2.

The structure of MSA-Mmaba Block.

Specifically, based on the CSP architecture, the module processes an incoming feature tensor, represented by . MSA-Mamba first performs multi-scale structural extraction using four depth-separable convolutional branches with different kernel sizes. After fusing features across all scales, we apply a pointwise convolution to obtain an output with a unified spatial dimension:

This structure can explicitly encode spatial edges, textures, and local context at different scales, effectively enhancing adaptability to targets with varying scales. Then, the resulting from the fusion of multi-scale features is normalized and converted into a sequence format:

Feature is processed through two parallel pathways. The first pathway subjects the feature to a sequence of operations: a linear transformation, depth-wise convolution, SiLU activation, a Multi-directional Structure-aware SSM (MDSa-SSM) layer, and LayerNorm (LN). Concurrently, in parallel, a shallower shortcut path applies a simple linear layer followed by a SiLU activation. The outputs from both pathways are then merged via element-wise multiplication. Subsequently, this fused representation is projected back to its original dimensionality with a linear projection. Finally, the residual connection is applied by adding the input feature to the projection result, yielding the final output . The computation of MSA-Mamba can be formulated as:

The MDSa-SSM constitutes a core component of the MSA-Mamba module. To overcome the spatial discontinuity caused by traditional row-by-row or column-by-column (sweep-scan) methods at path junctions (e.g., row ends), our Mamba flattens input images into one-dimensional sequences using a multidirectional zigzag scanning strategy. These eight directions comprise four fundamental scans (row-first, column-first, and their respective reverse scans) along with their horizontally or vertically flipped (Flip) variants. This enables the model to “examine” and “connect” pixels from multiple angles and paths, thereby capturing contextual information about targets oriented in any direction within remote sensing imagery with greater flexibility:

Each scan sequence is modeled through an independent state space modeling unit (SSM), then the state variable is computed based on the state transition equation: . Subsequently, these raw state variables computed in the 1D sequence are reshaped back into a 2D image format. However, these raw states can only capture dependencies along the 1D scan path, lacking direct perception of the 2D spatial structure. To address this issue and establish neighborhood connections directly within the state space, we introduce the “Normalized Structure-Aware State Fusion (SASF)” equation:

For each state , we apply normalized weights to its adjacent states within the neighborhood , integrating information from neighboring states in 2D space to compute a novel “structure-aware state” rich in 2D spatial context. This processing facilitates the acquisition of feature representations with enhanced contextual semantics.

To achieve Structure-Aware State Fusion (SASF), we employ deep separable convolution with varying dilation rates. Specifically, we utilize three deep separable convolution kernels with dilation rates to construct the neighborhood set , thereby integrating state information from near, intermediate, and far-range neighborhoods. The fusion process is as follows:

where denotes the normalized convolution kernel weight at position when the porosity is d; represents a neighboring feature to state , found at the relative coordinates , while w is the image’s width.

In this manner, the fused state integrates spatial contextual information from multiple directions, including horizontal, vertical, and diagonal. Finally, this state , rich in 2D structural information, enters the observation equation to generate the final output for that direction.

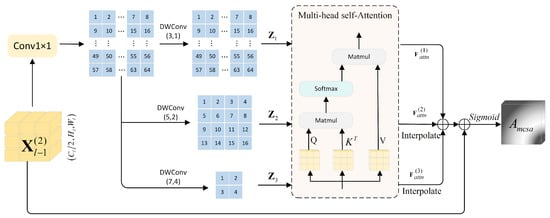

3.2. Multi-Granularity Contextual Self-Attention Block

In remote sensing imagery, spectral and textural differences between land cover types are often subtle. Therefore, uncovering more discriminative semantic correlations at the channel dimension has become a key direction for improving target recognition accuracy. Although MSA-Mamba possesses strong spatial perception and long-range modeling capabilities, it primarily focuses on spatial structures and multi-directional sequence modeling within feature maps. Consequently, its modeling of feature channel dimensions and processing of global semantic correlations remain relatively inadequate.

As mentioned in the introduction, traditional global self-attention mechanisms process all channels uniformly, lacking the ability to capture contextual differences across channels with varying receptive fields. To address this issue and complement the spatial modeling of MSA-Mamba, this paper introduces the Multi-granularity Contextual Self-Attention (MCSA) module, as shown in Figure 3. This module supplements the channel semantic modeling path, forming a joint contextual perception mechanism for both spatial and channel information.

Figure 3.

The structure of MCSA Block.

MCSA and MSA-Mamba are connected in parallel to input the same feature map . Their core objective is to perform semantic compression and importance modeling of inter-channel information, outputting an attention mask as a context modulation factor to control the response intensity of each channel during final fusion. The detailed procedure is defined as follows: The input feature undergoes channel mapping and nonlinear enhancement through convolutions:

This operation does not alter the spatial resolution but enhances semantic expression, laying the groundwork for subsequent channel attention operations.

Next, a multi-granularity strategy is employed to generate multi-granularity features through deep convolutions (DWConv) with different kernel sizes and strides. These features undergo multi-head self-attention processing and multi-path propagation to optimize representation. Specifically, three parallel deep convolution branches with distinct parameters generate multi-granularity feature maps: First group: employs a depthwise convolution with a kernel and a stride of 1; Second group: convolution with stride 2; Third group: kernel with stride 4. The feature map obtained is processed in parallel through multi-head self-attention to yield .

To compute the query, key, and value matrices required for the self-attention mechanism, we employ a weight-sharing strategy. A set of shared linear projection layers (implemented via convolutions) is independently applied to the multi-scale feature maps generated in the previous step, thereby producing corresponding for each branch.

For each branch i, the attention mechanism is:

Finally, the feature maps are downsampled through residual connections and interpolation fusion. We generate the attention weight map by applying the Sigmoid function, as defined in the following equation:

Among these, “Inter” represents an interpolation operation, while sigmoid ensures the attention map remains within the range (0, 1).

This process achieves non-local modeling across channel dimensions, enabling the perception of fine-grained dependencies between different semantic categories and enhancing the recognition capability of small objects in complex scenes.

The preceding MSA-Mamba module primarily addresses deficiencies in spatial modeling, while the MCSA module focuses on mitigating insufficient channel discriminative power. Combined, they achieve joint enhancement across both spatial and channel dimensions, collectively tackling the complexity of remote sensing imagery.

3.3. FI Stage

FI-MambaNet adopts a modular design with stacked stages, where the entire network consists of four main stages arranged sequentially. In the l stage, the input features are denoted as , and the output features are .

The structure of each stage is illustrated in Figure 1a. The overall stage architecture adopts a Cross-Stage Partial (CSP) connection scheme, enabling efficient channel partitioning and information flow decoupling in feature processing.

Specifically, the input features of stage l undergo an initial feature transformation through a convolution followed by a downsampling operation.Subsequently, the initial feature is split channel-wise into two parts and fed into two distinct branches:

The first parallel branch of this model consists of a lightweight Convolutional Feedforward Network (ConvFFN), designed to achieve efficient local semantic modeling and nonlinear feature transformation.Specifically, the input feature tensor is first processed by Layer Normalization, which stabilizes the data distribution. This is followed by an expansion layer composed of convolutions to increase the feature dimension in the channel dimension:

To achieve dynamic feature selection, the network incorporates a gating mechanism. Features after dimensionality expansion pass through a Sigmoid activation function, generating an attention weight map ranging from 0 to 1. This weight map is multiplied element-wise with the pre-expanded features, thereby adaptively amplifying or suppressing them. Finally, the features adjusted by the gating mechanism are restored to the target dimension through a projection layer composed of another convolution, ultimately yielding the output features :

The second branch, centered on context-enhanced pathways, is composed of a FIBlock formed by the parallel integration of MSA-Mamba and MCSA modules, as depicted in Figure 1b. This architecture possesses multi-scale spatial perception capabilities and channel semantic modeling capabilities:

Here, denotes the number of stacked FIBLOCK modules in the l stage.

Specifically, the attention map generated by the MCSA module acts as a channel-wise modulator. It adaptively enhances or suppresses the spatial features output by the MSA-Mamba module through element-wise multiplication.

Subsequently, residual connections are added to form an ’attention-gated residual learning’ mechanism, enabling the model to focus on the most critical spatio-channel joint features:

Here, ⊗ represents element-wise multiplication, and ⊕ represents element-wise summation. Finally, we denote the output of each FIBLOCK stage as .

Finally, features from both paths are merged on the channel axis and compressed via a convolutional layer with a kernel size of , with the output serving as the final feature for each stage:

This architecture achieves complementary integration of local rapid response and deep context modeling through a dual-branch design while maintaining computational efficiency.

4. Experiments

To validate the performance of the proposed model on remote sensing object detection tasks, this section details a comprehensive set of experiments. The chapter is organized as follows: first, we outline the public datasets used for our evaluation. Second, we describe the detailed settings and the metrics for performance assessment. Finally, we report and thoroughly analyze the results from comparative benchmarks and ablation studies to fully demonstrate the model’s advantages.

4.1. Datasets

DOTA-v1.0 [3] is a large-scale dataset for remote sensing object detection. It contains 2806 images. The dataset includes 188,282 object instances across 15 categories, including bridges (BRs) and ground runways (GTFs). The images are of various orientations and scales. Officially, the dataset is split 50% for training, 33% for testing, and the remainder for evaluation.

DOTA-v1.5 [3] dataset is a more challenging version of the DOTA-v1.0 benchmark, released for the 2019 DOAI Challenge. Compared with its predecessor, DOTA-v1.5 introduces a new object category named Container Crane (CC) and significantly increases the number of tiny instances whose sizes are less than 10 pixels.

HRSC2016 [2] is a remote sensing image dataset focused on vessel detection. Its images are primarily captured from real port scenarios, featuring high resolution, dense targets, and significant scale variations. The dataset comprises 1061 images, including 436 for training, 444 for testing, with the remainder reserved for validation. The dataset contains a total of 2976 ship instances, all precisely annotated using oriented bounding boxes. Such a property makes it well-suited for rigorous evaluation of model performance in the context of rotated object detection tasks.

4.2. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

In this work, we conducted a thorough evaluation of the proposed FI-MambaNet’s performance on oriented object detection, utilizing the DOTA-v1.0, DOTA-v1.5 and HRSC2016 benchmarks. To ensure fair comparisons, all experiments followed standard data handling protocols. For data preprocessing on DOTA-v1.0 and DOTA-v1.5, we adopted a multi-scale strategy for training and inference. Source images were first rescaled to factors of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5, and then partitioned into tiles with a 200-pixel overlap between them. This approach enhances robustness to object scale diversity and dense scenes. For the HRSC2016 dataset, images were resized by setting their longer edge to 800 pixels while preserving the aspect ratio, balancing scale normalization with geometric integrity. Regarding the training process, all backbones were initialized with ImageNet-1K pre-trained weights, followed by a fine-tuning phase on the target remote sensing datasets to enhance high-resolution feature extraction. In our comparative benchmarks with leading approaches, backbones were pre-trained for 300 epochs to maximize representational capacity, while ablation studies used an efficient 100-epoch schedule. Our model was implemented within the Oriented R-CNN framework; it was trained on the designated data splits, and final performance was measured on the test set. For optimization, we employed the AdamW optimizer, training for 36 epochs on HRSC2016, 30 epochs on DOTA-v1.0 and DOTA-v1.5. The initial learning rates were set to 0.0004 (HRSC2016) and 0.0002 (DOTA-v1.0, DOTA-v1.5), respectively, with dynamic adjustments made via a Cosine Annealing schedule with Warmup. A weight decay coefficient of 0.05 was used consistently for all experiments.

Model training was carried out using the MMRotate framework, leveraging four NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs in parallel under an Ubuntu 20.04 environment, with a total batch size of 8. During inference, evaluation was performed on a single RTX 4090 GPU. All reported FLOPs are computed based on input images of resolution. Detection performance is primarily assessed using the standard Mean Average Precision (mAP), which quantifies accuracy across different datasets.

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance, we employed four key metrics. MAP serves as the core standard for measuring detection accuracy; it is calculated from the area under the Precision-Recall curve across all categories, with a higher value indicating superior accuracy. FPS quantifies the model’s inference speed by representing the quantity of images the model can handle each second, which directly reflects its real-time performance and deployment efficiency.To enhance training and inference efficiency, we adopted FP16 mixed-precision computation. This configuration boosts inference speed without compromising detection accuracy. Finally, model complexity is assessed by Params and FLOPs. The Params (M) relates to the model’s size and storage requirements, while FLOPs (GFLOPs) measure the computational load for a single forward pass, indicating its computational efficiency.

4.3. Experimental Comparison

Performance on DOTA-v1.0: we benchmarked FI-MambaNet against 15 leading object detection models using the DOTA-v1.0 dataset. The integrity and consistency of the evaluation were maintained by processing all model predictions through the official evaluation server. As presented in Table 1, our model achieved a superior mAP of 80.2%. This represents a performance gain of 1.81% over PKINet-S and 2.71% over LSKNet-S, confirming the effectiveness and efficiency of our methodology in complex remote sensing contexts.

Table 1.

Comparison of detection results on the DOTA-v1.0 test set. Values highlighted in red indicate the best performance within each column.

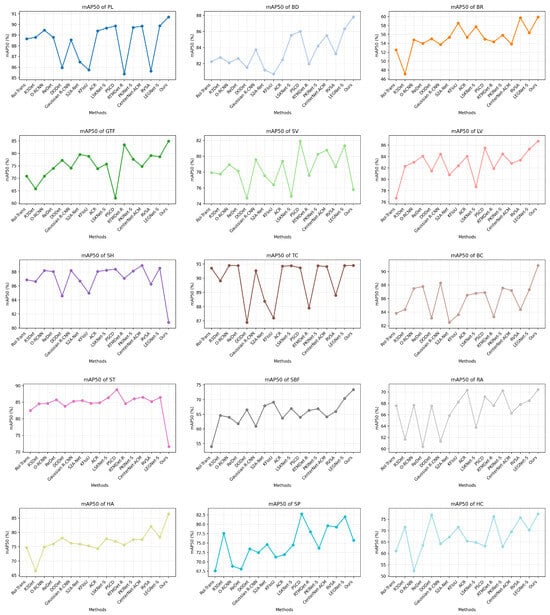

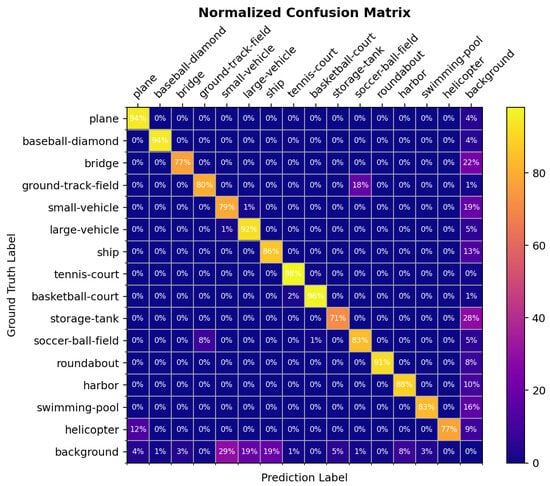

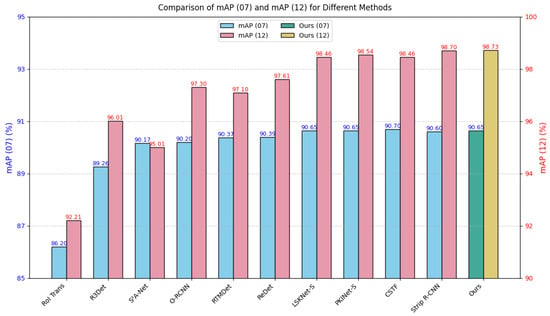

Additionally, Figure 4 presents a bar chart illustrating the overall detection performance, while Figure 5 displays a line chart showing the detection accuracy for each category. This visualization aims to demonstrate how detection performance varies across different backbones for each category, facilitating an intuitive analysis of FI-MambaNet’s strengths and weaknesses across different classes. This further demonstrates that FI-MambaNet maintains stable and excellent detection performance across most categories. However, we observe that the AP values for categories such as SH, SV, and ST are relatively low. This is primarily due to their smaller object sizes, higher intra-class similarity, and strong background interference. These factors make it more challenging to distinguish fine features. Figure 6 presents the confusion matrix obtained on the DOTA-v1.0 test set. Rows denote ground-truth categories, columns indicate predicted ones, and diagonal elements reflect the classification accuracy of each class. This visualization underscores FI-MambaNet’s strong discriminative capability and consistent robustness across multiple object categories. However, within the confusion matrix, certain small or visually similar categories still exhibit a certain probability of missed detection. This phenomenon primarily stems from the limited pixel representations of such targets and their densely clustered spatial distribution. To further investigate this issue, we conducted supplementary experiments on the DOTA-v1.5 dataset, which contains a greater number of small, rotation-sensitive targets.

Figure 4.

Map comparison of different detection frameworks.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Average Precision (AP) across different backbone networks on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset. The horizontal axis lists the compared models (discrete categories), while the vertical axis displays the AP values for each object category. Each curve corresponds to an object category, illustrating how its AP value varies across different models. Gridlines are included to enhance readability.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset.

Performance on DOTA-v1.5: The DOTA-v1.5 dataset contains a substantially larger number of small, densely distributed, and arbitrarily rotated objects compared with DOTA-v1.0, making it particularly suitable for evaluating detection robustness under complex remote sensing conditions. We conducted a comprehensive comparison between the proposed FI-MambaNet and seven representative detection methods on this dataset. As shown in Table 2, FI-MambaNet achieves a mean average precision (mAP) of 72.09%, outperforming PKINet-S by 0.62% and LSKNet-S by 1.83%. Notably, FI-MambaNet maintains strong detection accuracy in categories dominated by dense small objects and large rotation variations (e.g., SV, SH, ST). Although it does not achieve the highest AP in all classes, FI-MambaNet consistently ranks second, reflecting its stable and reliable detection performance.

Table 2.

Comparison of detection results on the DOTA-v1.5 dataset. Values highlighted in red indicate the best performance within each column.

The improved performance on DOTA-v1.5 can be attributed to its richer sample distribution and more precise annotation quality. Compared with DOTA-v1.0, the significantly increased number of small-object instances and higher annotation accuracy effectively reduce label noise, enabling FI-MambaNet to learn more discriminative fine-grained boundary and structural features. This allows the model’s multi-scale attention mechanism and structure-aware Mamba module to fully exploit their advantages under dense and rotation-sensitive conditions. Overall, FI-MambaNet shows strong adaptability to small-scale, high-density, and highly rotated targets, demonstrating competitive performance across challenging categories. Figure 7 further visualizes the overall accuracy comparisons among different models.

Figure 7.

Comparison of overall detection accuracy across different models on the Dota-v1.5 dataset.

Performance on HRSC2016: Ship objects in the HRSC2016 dataset demonstrate large variations in aspect ratios, arbitrary orientation shifts, and inconsistent scales even within the same class. These characteristics impose stringent requirements on the detector’s ability to generalize and maintain high detection accuracy. We systematically evaluated our proposed FI-MambaNet method against nine mainstream remote sensing object detection approaches on this dataset.

According to Table 3, FI-MambaNet records mAP values of 90.65% on VOC 2007 and 98.73% on VOC 2012, highlighting both its accuracy and strong generalization ability across datasets. These outcomes confirm the model’s robustness and adaptability in coping with pronounced scale variations. Moreover, Figure 8 provides a visual comparison of mAP(07) and mAP(12) across different approaches on the HRSC2016 dataset, clearly illustrating FI-MambaNet’s superior performance. Notably, while achieving high accuracy, FI-MambaNet demonstrates remarkable computational efficiency, requiring only 116 GFLOPs, which is substantially lower than PKINet-S (190 GFLOPs) and Strip R-CNN (159 GFLOPs). Additionally, FI-MambaNet achieves an inference speed of 25.3 FPS, significantly outperforming most comparison methods. However, despite its lower computational complexity (FLOPs), the overall FPS does not reach the maximum due to Mamba’s sequential feature computation and limited parallelism.

Table 3.

Comparison of detection performance on the HRSC2016 benchmark, with the highest results in each column highlighted in red.

Figure 8.

Comparison of different models on the HRSC2016 dataset.

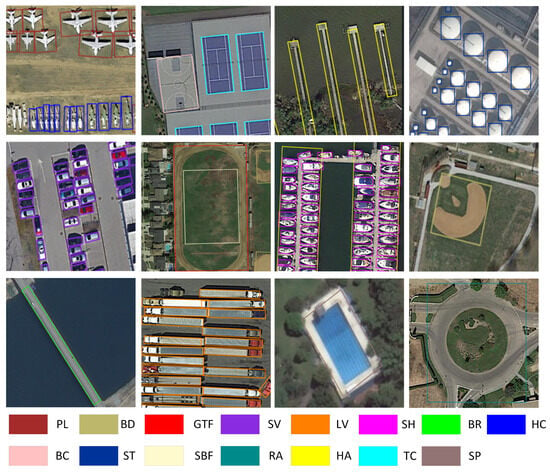

In summary, experiments demonstrate that FI-MambaNet achieves significant accuracy improvements on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset and delivers superior detection results on the more challenging DOTA-v1.5 and HRSC2016 datasets. The improvements in remote sensing object detection accuracy can be attributed to the following factors: (1) The MSA-Mamba module designed in the model integrates multi-scale feature extraction with multi-directional scanning spatial perception state modeling capabilities. Through a normalized structural perception state mechanism, it significantly enhances the modeling capabilities for local structures and global context in remote sensing images, effectively adapting to the characteristics of diverse target scales and complex structures. (2) The proposed MCSA module employs convolutional branches with varying receptive fields and dilation rates to concurrently model multiscale channel contextual information. This enhances information exchange and discriminative power across channel dimensions, effectively mitigating confusion caused by similar textures or dense targets. Together, these components form the joint spatial channel perception mechanism in FIBLOCK, enhancing the discriminative power and robustness of feature representation, thereby enabling accurate detection of remote sensing targets. Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show visualization results on the DOTA-v1.0, DOTA-v1.5 and HRSC2016 datasets.

Figure 9.

Visualization of detection results from our proposed method on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset. Bounding boxes are color-coded by object category.

Figure 10.

Visualization of our proposed algorithm’s partial category detection results on the DOTA-v1.5 dataset, where CC represents the newly added container crane in DOTA-v1.5.

Figure 11.

Visualization of detection results from our proposed method on the HRSC2016 dataset.

4.4. Ablation Study

The proposed FI-MambaNet consists of two core modules: the MCSA module and the MSA-Mamba module. To validate its effectiveness, we conducted several ablation experiments and compared the results with the O-RCNN baseline model.

4.4.1. Ablation Study on Multi-Scale Fusion in the MSA-Mamba Block

As seen in Table 4, we looked into kernel designs for MSA-Mamba’s group fusion technique. The findings show that using just kernels with small receptive fields (e.g., and ) leads to inferior detection accuracy, as their restricted receptive fields hinder the effective extraction of texture details, despite achieving a marginal reduction in parameter size. To address this limitation, we further introduced a grouped kernel configuration with sizes (5, 7, 9, 11). When kernel sizes spanned the range of to , the model achieved optimal performance with an mAP of 80.2% and the FPS only dropped slightly. However, further increasing kernel sizes (e.g., (5, 9, 13, 17), (9, 13, 15, 17)) led to substantially higher parameters (27.62 M) and computational cost (159G FLOPs), while mAP declined (to a minimum of 79.65%). indicating that larger kernels introduce excessive background noise, disrupting target feature learning while simultaneously slowing down inference speed.

Table 4.

Impact of different convolution kernel combinations in MSA-Mamba on parameters, FLOPs, FPS, and mAP on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset.

These results indicate that the grouping fusion strategy (5, 7, 9, 11) achieves an optimal balance between detection speed and accuracy. This approach efficiently extracts multi-scale contextual features while mitigating excessive computational overhead, achieving strong performance in both FPS and mAP. It thus emerges as a highly practical preferred solution for balancing accuracy requirements and inference efficiency in remote sensing object detection tasks.

4.4.2. Analysis of Scanning Directions in the MSA-Mamba Block

As shown in Table 5, We examined the impact of the number of scanning directions on remote sensing target detection. The first column in the table indicates the number of scanning directions. Experimental results demonstrate that when the number of scanning directions is 2, the model parameters (Params = 24.72 M) and computational overhead are low. However, due to insufficient coverage of multi-directional features of the target, the mAP is only 77.69%. Increasing to 4 directions simultaneously boosted parameters (25.29 M) and feature representation capability, achieving an mAP of 78.92%, validating that multi-directional scanning captures richer spatial information of the target. Conversely, expanding to 8 directions further increased parameters (26.44 M) while comprehensively covering the target’s texture and structural features, elevating mAP to 80.2%.

Table 5.

Impact of the number of scanning directions on Params and mAP on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset.

The results indicate that increasing the number of multi-directional scan directions enhances detection accuracy by improving multidimensional feature coverage, but this also leads to higher parameter complexity and computational demands. Among these, 8-directional scanning demonstrated optimal performance in both feature completeness and accuracy improvement. Within the computational constraints tolerable by the model, it achieved comprehensive extraction of multi-directional features, providing a reference for optimizing performance using the Mamba multi-directional scanning mechanism in remote sensing object detection.

4.4.3. Analysis of the MCSA Block

The ablation study on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset reveals that the downsampling frequency within the MCSA module has a substantial influence on detection performance. As presented in Table 6, increasing the number of paths from 0 to 3 gradually raises the parameter count from 22.47 M to 28.46 M. This is because additional downsampling paths introduce extra convolutional and feature processing operations, thereby increasing model complexity and computational overhead. Regarding detection accuracy, the mAP reached its peak value of 80.2% when the subsampling path count was set to 2. This result indicates that combining the original resolution with two subsampling paths achieves a more reasonable complementarity between features at different scales: high-resolution features preserve fine-grained semantic information, while subsampling paths effectively capture spatial dependencies of large-scale objects. This balance achieves an optimal trade-off between feature redundancy and critical information retention, thereby enhancing performance. In contrast, models with fewer than two paths struggle to adequately cover multi-scale object features, resulting in suboptimal performance. Performance degrades when the number of paths increases to three. We speculate this may stem from excessive downsampling causing loss of critical fine-grained information, where introduced noise or feature redundancy outweighs the gains from multi-scale context. In summary, experiments validate that incorporating an appropriate number (two) of downsampling paths within the MCSA module most effectively leverages the advantages of the multi-scale scanning strategy.

Table 6.

Effect of downsampling frequency on Params and mAP on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset.

4.4.4. Collaborative Analysis of MSA-Mamba and MCSA

In addition to parameter adjustments within individual modules, we also examined the distinct and joint effects of the MCSA block and the MSA-Mamba block on overall performance. To this end, three comparative experimental settings were established: (1) Baseline with only MSA-Mamba, (2) Baseline with only MCSA, and (3) the complete FI-MambaNet integrating both modules. The detection results on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset are summarized in the Table 7 below.

Table 7.

Ablation study of MSA-Mamba and MCSA blocks on FPS and mAP.

The results show that introducing the MSA-Mamba block alone can elevate the baseline mAP to 78.73%, indicating that this module effectively enhances feature extraction capabilities, captures long-range spatial dependencies, and enables the model to identify targets with greater precision. The standalone introduction of the MCSA block increases the baseline to 79.05%, demonstrating that the MCSA block efficiently strengthens channel and semantic correlations. When the two modules are integrated, the model achieves 80.20% mAP, yielding a 4.33% improvement over the baseline. This performance gain stems from the complementary nature of the modules, which together enable more comprehensive extraction of both local and global features, thereby enhancing semantic representation and inter-channel dependencies for more accurate object detection. However, despite these components significantly improving detection accuracy and global-local feature interaction effects, FI-MambaNet’s FPS is slightly lower than the baseline due to the additional matrix operations introduced by MSA-Mamba’s sequential state updates and MCSA’s channel correlation calculations.

4.4.5. Performance Evaluation of FI-MambaNet Across Diverse Detection Frameworks

We incorporate the proposed FI-MambaNet backbone into a number of representative remote sensing object recognition frameworks to fully evaluate its generalization ability. We conducted rigorous performance comparisons against the widely adopted ResNet-50 as a baseline. To ensure fairness in the comparisons, all detection frameworks employed identical training hyperparameters and data preprocessing procedures, adhering to the settings described in Section 4.2.

The experimental results are shown in Table 8, where FI-MambaNet consistently outperforms the ResNet-50 baseline. For single-stage architectures, our backbone achieves significant mAP improvements of 3.32%, 3.77%, and 2.63% when integrated with Rotate FCOS, R3Det, and S2ANet, respectively. For two-stage architectures, FI-MambaNet also achieves substantial gains, improving performance by 3.34%, 4.86%, and 4.33% when integrated with RoI Trans, Faster R-CNN, and ORCNN, respectively. Notably, when paired with the advanced detector ORCNN, our method achieves an mAP of 80.20%, delivering the best result across all tested frameworks. Experimental data demonstrate that FI-MambaNet’s architectural advantages exhibit outstanding universality, enabling it to serve as an efficient base network empowering diverse detection models rather than being tightly coupled with specific architectures. Figure 12 illustrates the relationship between parameter count and detection accuracy for different models using ResNet-50 and our FI-MambaNet as backbones, further demonstrating the efficiency and effectiveness of FI-MambaNet.

Table 8.

Comparing ResNet-50 with FI-MambaNet using various frameworks on the DOTA-v1.0 dataset.

Figure 12.

Compared to different remote sensing detectors [5,10,11,12,77,78], our method has fewer parameters and performs better. Circles represent detection results using ResNet50 as the backbone, while triangles denote results after replacing it with our FI-MambaNet.

5. Conclusions

Remote sensing object detection (RSOD) is hindered by challenges such as significant variations in target scale, background clutter, and highly similar surface textures. To overcome these issues, this paper introduces a novel backbone network, FI-MambaNet. Our work designs two core modules operating across orthogonal spatial and channel dimensions. Firstly, the Multi-Scale Structure-Aware Mamba (MSA-Mamba) effectively mitigates spatial information distortion inherent in traditional state-space models when processing two-dimensional images. This is achieved by combining multi-scale convolutions with a multi-directional scanning strategy incorporating structure-aware state fusion, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to capture both local structural details and global contextual information for multi-scale objects. Secondly, the Multi-granularity Contextual Self-Attention (MCSA) module enhances semantic discrimination capabilities in the channel dimension by processing features from different receptive fields in parallel, effectively mitigating feature confusion caused by similar object textures or dense distributions.

FI-MambaNet was used as the backbone model for the Oriented R-CNN detection framework and rigorously evaluated on three datasets: DOTA-v1.0, DOTA-v1.5 and HRSC2016. Experimental results demonstrated that FI-MambaNet achieved mAPs of 80.20%,71.99% and 90.65% on the three datasets, respectively. Comprehensive ablation studies further demonstrated that both the MSA-Mamba and MCSA modules contribute to improved model performance, and their combined application has a synergistic effect, enhancing the robustness of feature representation.

While FI-MambaNet has achieved significant breakthroughs in detection accuracy, several limitations remain. First, the introduction of more complex modules results in a decrease in inference speed (FPS) compared to the baseline model. Second, experimental validation focused on common optical remote sensing datasets, with a relatively limited number of state-of-the-art methods for comparison. Finally, due to the inherent recognition challenges posed by small-sized and densely distributed targets, performance on several small object categories (such as SH, SV, and ST) remains slightly inferior to certain specialized small object detectors. Further optimization of small object representation remains an open direction for future research. Therefore, the model’s generalization capabilities require further verification. Future work will focus on the following areas:

- 1.

- Focus on model lightweighting and inference optimization, such as simplifying redundant linear operations through module reparameterization, knowledge distillation, and network pruning to enhance deployment efficiency;

- 2.

- Exploring the extension of FI-MambaNet’s design principles to multi-source remote sensing data, such as SAR, hyperspectral, and lidar imagery, whilst investigating corresponding model adaptation adjustments to enhance robustness across broader application scenarios;

- 3.

- Conduct testing on larger and more diverse datasets, alongside comprehensive comparisons with the latest detection algorithms, to more thoroughly evaluate the model’s overall performance;

- 4.

- FI-MambaNet still faces limitations in dense small-sized targets and complex environments. Future research will focus on reducing missed detections through refined small-object feature modeling, adaptive attention mechanisms, and improved rotation-aware alignment strategies;

- 5.

- In the future, we will focus on enhancing the detection capability of extremely small and highly rotating targets. We plan to explore adaptive receptive field adjustment and rotation-aware feature encoding to improve robustness, reduce the missed detection rate, and further enhance performance in dense and complex scenes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L., C.Y. and L.Y.; methodology, J.L. and L.Y.; validation, C.Y. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L., C.Y. and X.T.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, X.T.; project administration, L.Y.; funding acquisition, L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (62472149, 62302155).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all providers of the datasets used in this study. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable comments that contributed to the improvement of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, X.; Wang, P.; Yan, Z.; Xu, F.; Wang, R.; Diao, W.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Feng, Y.; Xu, T.; et al. FAIR1M: A benchmark dataset for fine-grained object recognition in high-resolution remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 184, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Weng, L.; Yang, Y. Ship rotated bounding box space for ship extraction from high-resolution optical satellite images with complex backgrounds. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA:A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3974–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhu, J. Oriented reppoints for aerial object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Xia, G.S. Align deep features for oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5602511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fu, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xia, G.S.; Bai, X. Gliding vertex on the horizontal bounding box for multi-oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Hou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Yan, J. Dense label encoding for boundary discontinuity free rotation detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 15819–15829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Tian, Q.; Yan, J. Learning high-precision bounding box for rotated object detection via kullback-leibler divergence. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 18381–18394. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q. The KFIoU loss for rotated object detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.12558. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.S.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI transformer for oriented object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 2849–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Oriented R-CNN for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3520–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, Z.; He, T. R3det: Refined single-stage detector with feature refinement for rotating object. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 3163–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q. Rethinking rotated object detection with gaussian wasserstein distance loss. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 11830–11841. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Meng, G.; Xiang, S.; Sun, J.; Jia, J. Stitcher: Feedback-driven data provider for object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.12432. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsolmoali, P.; Zareapoor, M.; Chanussot, J.; Zhou, H.; Yang, J. Rotation equivariant feature image pyramid network for object detection in optical remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5608614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ma, W.; Jiao, L.; Chen, P.; Yang, S.; Hou, B. Multi-scale image block-level F-CNN for remote sensing images object detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 43607–43621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lu, X. Hierarchical and robust convolutional neural network for very high-resolution remote sensing object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 5535–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Ji, K.; Leng, X.; Kuang, G. Squeeze and excitation rank faster R-CNN for ship detection in SAR images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 16, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hou, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, M.M.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Large selective kernel network for remote sensing object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 16794–16805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shen, X.; Zhang, X.; Guan, F. Lightweight Ship Object Detection Algorithm for Remote Sensing Images Based on Multi-scale Perception and Feature Enhancement. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2025, 91, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Mohamed, A.S.A. Gaussian-based R-CNN with large selective kernel for rotated object detection in remote sensing images. Neurocomputing 2025, 620, 129248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Lai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Yao, Y. Poly kernel inception network for remote sensing detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 27706–27716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Talebi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P.; Bovik, A.; Li, Y. Maxvit: Multi-axis vision transformer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, L.; Wu, B.; Lin, B.; He, X.; Liu, W. Crossformer++: A versatile vision transformer hinging on cross-scale attention. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 3123–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Ren, Y.; Sheng, K.; Dong, W.; Yuan, H.; Guo, X.; Ma, C.; Xu, C. Dynamic refinement network for oriented and densely packed object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11207–11216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabati, R.; Qi, H. Rrpn: Radar region proposal network for object detection in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 3093–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Xia, G.S. Redet: A rotation-equivariant detector for aerial object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 2786–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Yan, J. ARS-DETR: Aspect ratio-sensitive detection transformer for aerial oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Online, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.; Liu, H.; Tang, H.; Wu, Z.; Song, P. Ao2-detr: Arbitrary-oriented object detection transformer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 33, 2342–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, W. FPNFormer: Rethink the method of processing the rotation-invariance and rotation-equivariance on arbitrary-oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T.; Warrington, A.; Linderman, S.W. Simplified state space layers for sequence modeling. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.04933. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00396. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. Vmamba: Visual state space model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 103031–103063. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.O. Rs 3 mamba: Visual state space model for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6011405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Rsmamba: Remote sensing image classification with state space model. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 8002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Jin, X.; Zhou, X.; Dong, J.; Du, Q. MSFMamba: Multi-scale feature fusion state space model for multi-source remote sensing image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5504116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Han, C.; Xia, J.; Yokoya, N. ChangeMamba: Remote sensing change detection with spatiotemporal state space model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4409720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Cai, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Fan, L.; Nguyen, A. Samba: Semantic segmentation of remotely sensed images with state space model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision mamba: Efficient visual representation learning with bidirectional state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Z.; Espinosa, M.; Ericsson, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Crowley, E.J. Plainmamba: Improving non-hierarchical mamba in visual recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.17695. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Pei, X.; You, S.; Wang, F.; Qian, C.; Xu, C. Localmamba: Visual state space model with windowed selective scan. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, Q.; Chen, H.; Gan, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Tian, G.; Xie, L. Mambaad: Exploring state space models for multi-class unsupervised anomaly detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 71162–71187. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Song, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Song, S.; Ge, Y.; Li, X.; Shan, Y. Grootvl: Tree topology is all you need in state space model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.02395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Vedaldi, A. Gather-excite: Exploiting feature context in convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, J.; Lin, S.; Wei, F.; Hu, H. Gcnet: Non-local networks meet squeeze-excitation networks and beyond. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, X.; Yang, J. Spatial group-wise enhance: Improving semantic feature learning in convolutional networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.09646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Woo, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Bam: Bottleneck attention module. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, D.; Meng, Q.; Li, S.; Yuan, X. Improving transformers with dynamically composable multi-head attention. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.08553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.W.; Cao, J.L.; Cheng, M.M.; Hou, Q. Dformerv2: Geometry self-attention for rgbd semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 19345–19355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Meng, X. SCSA: A Plug-and-Play Semantic Continuous-Sparse Attention for Arbitrary Semantic Style Transfer. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 13051–13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xia, X.; Liu, J.; Yi, Z.; He, T. Strengthening layer interaction via dynamic layer attention. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.13392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhu, R.J.; Chou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Deng, L.j.; Li, G. Gated attention coding for training high-performance and efficient spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, J.W.; Yeh, I.H. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Yao, Y.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Dual-aligned oriented detector. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5618111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gan, W.; Wang, Z.; Song, S.; Huang, G. Adaptive rotated convolution for rotated object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 6589–6600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Da, F. Phase-shifting coder: Predicting accurate orientation in oriented object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 13354–13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, K. Rtmdet: An empirical study of designing real-time object detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.07784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, C.; Dai, F. Rethinking boundary discontinuity problem for oriented object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 17406–17415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Du, B.; Tao, D.; Zhang, L. Advancing plain vision transformer toward remote sensing foundation model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 61, 5607315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chen, S.B.; Li, H.D.; Shu, Q.L.; Ding, C.H.; Tang, J.; Luo, B. Legnet: Lightweight edge-Gaussian driven network for low-quality remote sensing image object detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.14012. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]