Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A comprehensive review of recent advances in oil spill detection, classification, and thickness estimation from the perspectives of artificial intelligence (AI) and remote sensing (RS) technology.

- The open datasets and multi-source data fusion enhance model accuracy and generalization in oil spill detection, classification, and thickness estimation.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- AI–RS integration enables real-time, automated marine oil spill monitoring and rapid response.

- Future research should focus on explainable, adaptive, and cross-scene intelligent monitoring systems.

Abstract

Marine oil spill incidents are one of the major global marine pollution issues, which pose significant threats to ocean ecosystems. However, traditional monitoring methods often suffer from time delays, high costs, and limited real-time capability, making them inadequate for timely and large-scale oil spill detection. With the development of remote sensing (RS) technology and artificial intelligence (AI) methods, as well as the increasing frequency of marine oil spill accidents, plenty of AI-based methods using RS imagery have been proposed for more efficient and accurate oil spill monitoring. This review presents a comprehensive and systematic overview of recent progress in marine oil spill analysis using RS imagery, emphasizing the integration of AI methods across three key tasks: detection, classification, and thickness estimation. Specifically, we first introduce the main types of RS data and discuss the significance of publicly available datasets, which can facilitate method validation and model comparison. Second, we briefly review the application of RS imagery from different sensors in oil spill detection, highlighting the strengths of various spectral and polarimetric methods. Third, we summarize advances in oil spill classification, including AI-based methods that enable differentiation between mineral oil, biogenic films, and various emulsified oils. Fourth, we discuss emerging techniques for oil spill thickness estimation. Finally, we analyze the challenges of existing methods and future directions, including the need for real-time monitoring, the integration of multi-source RS data, and the development of robust models that can generalize across different environmental conditions. This review adopts a comprehensive perspective from both AI methods and RS technology, provides a systematic overview of recent advancements, identifies critical gaps in current methodologies, and serves as a valuable reference for researchers and practitioners working on oil spill monitoring.

1. Introduction

Marine oil spills are among the most devastating environmental disasters with profound consequences for marine ecosystems, coastal communities, and the global economy. In 2010, the Deepwater Horizon explosion in the Gulf of Mexico triggered one of the most catastrophic oil spills in history, leading to profound ecological and socioeconomic consequences [1]. Another major spill occurred in 2018 when the Sanchi oil tanker collided with a bulk carrier near Hong Kong, releasing oil that spread over 100 km2 of the sea surface and required nearly two weeks for initial cleanup [2]. These incidents highlight the critical need for effective oil spill monitoring. Early detection is essential for minimizing the spread and impact of pollution, enabling a faster response. Meanwhile, these efforts play a vital role in promoting the protection and sustainable utilization of ocean, sea, and marine resources, thereby supporting the realization of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14 [3].

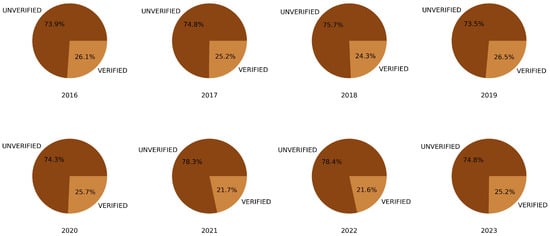

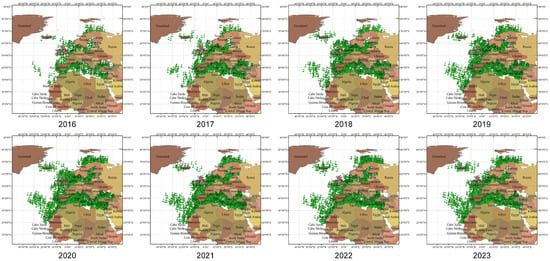

Traditional oil spill monitoring relies on visual inspections, ship-based sampling, and in situ sensors [4], which can provide accurate localized information. However, these methods are limited by subjectivity, adverse weather, labor-intensive and time-consuming analyses, and narrow spatial coverage with high operational costs. For example, Figure 1 shows the proportion of verified and unverified oil spill events reported by the CleanSeaNet program from 2016 to 2023. A considerable number of reported incidents were not manually validated, highlighting the resource-intensive nature of manual validation. Specifically, before the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) methods, each detection had to undergo manual verification to determine whether it truly represented an oil spill or a look-alike phenomenon such as low-wind areas, algal blooms, or biogenic films. This verification process typically requires cross-referencing with ancillary data and expert interpretation, making it highly resource-intensive and underscoring the urgent need for robust and scalable AI methods capable of generalizing across diverse environmental conditions. The advancement in remote sensing (RS) technology and the wider availability of satellite imagery have made RS a practical and effective alternative to traditional oil spill monitoring. RS enables large-scale, rapid detection and timely response during major spill events. In particular, the integration of AI methods has significantly enhanced the capability for automated oil spill detection, classification, and thickness estimation. Furthermore, the Marine Pollution Products of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) [5], CleanSeaNet program of the EMSA [6,7], and Copernicus Sentinel Program [8] provide extensive publicly available RS imagery and oil spill coordinates. These open resources support the construction of large-scale deep learning training and benchmark datasets, significantly advancing research on oil spill monitoring. As shown in Figure 2, the spatial distribution of oil spill incidents reported by CleanSeaNet from 2016 to 2023 demonstrates the wide geographic coverage and long-term monitoring capability of these datasets. Therefore, recent research has focused on developing AI-enabled methods using RS imagery that significantly improve monitoring efficiency and analytical accuracy. These advances have played a pivotal role in both technological innovation and practical deployment for marine oil spill monitoring and response [9].

Figure 1.

Proportion of verified and unverified oil spill events reported by the CleanSeaNet program from 2016 to 2023.

Figure 2.

The spatial distribution of oil spill incidents reported by CleanSeaNet from 2016 to 2023.

The methods based on RS imagery for marine oil spill research primarily rely on three major types of imagery: optical, synthetic aperture radar (SAR), and thermal infrared (TIR). Each data source has been explored for oil spill detection (OSD), oil spill type classification (OSTC), and thickness estimation, with varying levels of effectiveness and challenges. Optical RS offers multi-spectral and high-resolution imagery, allowing for detailed analysis of sea surface composition and texture. This capability makes it particularly effective in identifying oil spills and distinguishing them from look-alike phenomena such as algal blooms or low-wind areas [10,11]. In the context of OSD, both multispectral and hyperspectral images have been used in combination with thresholding [12,13], spectral index [14], or classification models [15,16]. However, optical RS data are strongly affected by sun glint, cloud cover, water turbidity, and atmospheric scattering [17,18]. For OSTC, optical RS data enable the differentiation of oil spill types based on spectral features, although the spectral similarity between different oils and changes induced by emulsification and weathering reduce the accuracy [19,20,21,22]. In oil spill thickness estimation, reflectance-based models and regression analysis have been used to estimate the thickness [23,24]. Traditional methods struggle with subtle spectral differences, while recent studies employ convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and spectral–spatial feature learning to improve generalization [25,26].

SAR is widely used in marine oil spill monitoring due to its all-weather, day–night imaging capability and its sensitivity to changes in sea surface roughness [27]. Traditional OSD methods utilizing SAR imagery typically consist of three major steps: dark-spot detection, threshold segmentation, and classification [28,29]. However, these methods generally rely on conventional machine learning methods such as Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Decision Trees, which require manual feature extraction [30]. With the rapid development of deep learning, data-driven methods have been widely adopted in OSD. Deep neural networks can automatically learn high-level spatial and contextual features from large-scale SAR imagery, thereby significantly improving detection accuracy, robustness, and efficiency compared to traditional methods [30,31,32]. For the task of OSTC, polarimetric features were widely used to differentiate various oil spill types [33,34,35]. In terms of thickness estimation, existing methods typically combine neural networks or machine learning with entropy, damping ratio, or planning information to invert oil spill thickness [36,37,38,39].

TIR RS operates independently of solar illumination and therefore enables all-weather monitoring, particularly effective for oil spill detection at night or under low-light conditions [40]. Temperature contrasts exist between oil spills and the surrounding seawater, which allows for the extensive use of TIR RS in oil spill detection [41,42,43,44] and thickness estimation [45,46,47]. However, because thermal contrast is significant only when oil layers are sufficiently thick, it is highly sensitive to thick oil layers but less effective for detecting thin films or emulsified oil [48]. To overcome the limitations of individual sensors and enhance model robustness, multisource data fusion has attracted increasing attention in oil spill monitoring [49,50,51,52]. The combination of optical RS and SAR can provide complementary information on both spectral characteristics and surface roughness [53,54], while the integration of optical and TIR data enables the joint analysis of spectral and temperature features [52,55]. However, multimodal approaches still face several technical challenges, including spatiotemporal alignment, discrepancies in data resolution, and high computational complexity [30].

In recent years, numerous review articles have summarized the applications of RS technologies and AI methods in marine pollution or oil spill monitoring. Fingas et al. discussed the current RS techniques used for oil spill surveillance [17,56]. Al-Ruzouq et al. reviewed various sensors and machine learning approaches for oil spill detection [4]. Jafarzadeh et al. provided an overview of studies employing SAR for oil spill detection [57]. Temitope Yekeen et al. examined the application of AI techniques in marine oil spill detection, prediction, and vulnerability assessment [58]. In addition, some recent reviews have emphasized specific aspects of marine pollution. Srinivasan et al. [59] focused primarily on unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technologies for detecting oil pollution in seawater and discussed the role of AI in addressing marine oil contamination. Prakash et al. concentrated on the broader applications of AI technologies in marine pollution monitoring [60]. Samsuria et al. mainly addressed the problems, impacts, and monitoring methods associated with petroleum pollution [61]. Unlike these previous reviews, the review aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic overview of recent progress at the intersection of RS technology and AI methods for marine oil spill monitoring. Specifically, we highlight recent progress in AI-driven methods and different sensor data within marine oil spill detection, classification, and thickness estimation. First, we provide a systematic summary of the RS data types, primary data sources, and publicly available datasets commonly used for oil spill monitoring. Second, we comprehensively review the latest advances in AI and RS technologies for oil spill detection, classification, and thickness estimation, highlighting their strengths and limitations. Finally, based on existing studies, we analyze the current challenges in oil spill monitoring and discuss potential future research directions and solutions. This review integrates recent advances in RS and AI, providing a unified perspective and valuable reference for improving oil spill monitoring and response systems. The main contributions are as follows.

- 1.

- We provide a comprehensive review of recent advances in applying AI and RS to oil spill detection, classification, and thickness estimation, highlighting the strengths, limitations, and complementary roles.

- 2.

- We summarize key publicly available datasets and data sources that support the oil spill RS monitor with AI methods.

- 3.

- From the aspects of tasks, data, and methods, we discuss major challenges and propose future directions for developing more accurate, real-time, and explainable marine oil spill monitoring systems.

2. Remote Sensing Data & Datasets

2.1. Remote Sensing Data

The major RS technology applied to oil spill monitoring include SAR, optical RS, and TIR RS. Optical RS data further comprise multispectral and hyperspectral data, ultraviolet, RGB imagery and laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) [40,62]. SAR enables wide-area, all-weather monitoring but lacks oil type and thickness discrimination [27]. Multispectral imagery offers broad coverage and basic oil differentiation but suffers from limited spectral resolution [63]. Hyperspectral data provide detailed spectral signatures for oil characterization but are constrained by environmental sensitivity and scale [64,65]. Ultraviolet RS offers unique advantages in detecting thin oil spills through fluorescence and high reflectance contrast, but its practical application remains limited. It high dependence on illumination conditions, and significant background interference from biogenic and organic materials on the sea surface [42]. RGB imagery is low-cost, easy to acquire, and offers high spatial resolution. However, it contains only three broad spectral bands, and the color space is easy to alias [66]. LIF can operate effectively at night. It is insensitive to solar glare and sea-surface whitecaps, but struggles to differentiate between oils with similar fluorescence spectra [67]. TIR can be used effectively for detecting thick oil spills. Its sensitivity decreases sharply for thin films, and its performance strongly depends on environmental conditions such as solar illumination, wind, and sea surface temperature. Moreover, TIR sensors generally have lower spatial resolution, are prone to false positives from other thermal anomalies [68].

Different types of RS data are suitable for different oil spill monitoring tasks. Various countries have launched multiple satellites dedicated to acquiring RS imagery for these purposes. These satellites possess distinct sensor characteristics, spatial and temporal resolutions, revisit frequencies, spectral ranges, and observation capabilities, making them suitable for diverse monitoring objectives and environmental conditions [4]. Table 1 presents an overview of commonly used satellites in oil spill research, including their sensor types, revisit times, sources, launch dates, spatial resolutions, and bands, as well as the corresponding data download links. Sentinel-1, Envisat, and RADARSAT-2 are dedicated to SAR imaging, which enables detecting oil spills under all-weather and day-night conditions due to the capability to penetrate clouds and darkness [69,70,71]. Landsat-8, Sentinel-2, and MODIS can provide valuable information for oil type classification and spill thickness estimation by capturing spectral signatures at different wavelengths [72,73]. Moreover, Landsat-8 and Landsat-9 also play an important role through their TIR sensors, providing complementary information for identifying thick oil slicks. TIR is effective for detecting oil spills due to the temperature differences between oil and water, especially at night or under low-light conditions [43,68]. The selection of an appropriate satellite depends on the monitoring objective, whether it is oil spill detection, type classification, or thickness estimation.

Table 1.

An overview of commonly used satellites in oil spill research, including their sensor types, revisit times, sources, launch dates, spatial resolutions, and bands, as well as the corresponding data download links.

In addition to spaceborne platforms, airborne RS plays a significant role in oil spill monitoring. Airborne sensors, such as hyperspectral cameras, TIR imagers, and laser fluorosensors, provide higher spatial and spectral resolutions than satellite sensors, making them particularly effective for localized spill assessment and validation of satellite-derived results [74]. Specifically, Hyperspectral sensors, such as (Airborne Imaging Spectrometer for Applications) AISA and (Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer) AVIRIS, further enhance discrimination capabilities by offering hundreds of contiguous spectral bands, making them particularly useful for oil characterization and differentiation from other oceanic features [15,75,76,77]. Airborne synthetic aperture radar (AIRSAR) and drone-based multispectral imaging have also been increasingly utilized for near-real-time oil spill response [78]. The integration of satellite and airborne observations enhances the reliability and accuracy of OSD and characterization, enabling more effective environmental management and response strategies. Table 2 shows an overview of commonly used airborne platforms in oil spill research.

Table 2.

Summary of airborne platforms for oil spill monitoring.

2.2. Datasets

AI-driven RS methods for oil spill monitoring increasingly rely on publicly available labeled imagery. Such datasets typically provide RS images, pixel-level annotations, and auxiliary environmental metadata, which are essential for training, validating, and benchmarking machine-learning models. The availability of these resources has substantially accelerated progress in algorithm development, enabling reproducible comparisons, model generalization studies, and performance improvements in detection, classification, and thickness-estimation tasks. Table 3 summarizes several key publicly accessible datasets used in oil spill research.

Table 3.

Summarizes the key datasets that are publicly available for oil spill research. SOS denotes Deep-SAR Oil Spill, OSD stands for Oil Spill Detection, HSI refers to Hyperspectral Imagery, and HOSD represents the Hyperspectral Oil Spill Database.

The M4D dataset [79,80,81], built from Sentinel-1 imagery collected between September 2015 and October 2017, provides labeled SAR images for oil spill detection and segmentation, thereby facilitating the development and evaluation of deep learning models in marine pollution monitoring [30,32,89]. It contains a total of 1100 SAR images, of which 1000 are used for training and 100 for testing. Meanwhile, it also introduces the classes of look-alike and ship to improve the model performance. The Deep-SAR Oil Spill (SOS) dataset [82,83] composed of two parts: SOS-PALSAR and SOS-Sentinel. The SOS-PalSAR dataset is from the Gulf of Mexico and was acquired by the PalSAR sensor. It uses HH polarization with a spatial resolution of 12.5 m. The dataset contains 2877 images, including 3101 for training and 766 for testing. The SOS-Sentinel dataset is from the Persian Gulf and was collected by the Sentinel-1 satellite. It uses VV polarization with a spatial resolution of 10 m. The dataset includes 4193 images, with 3354 used for training and 839 for testing. Although the SOS dataset provides a larger collection of images than the M4D dataset, it contains only two classes of oil spill and non-oil spill. With the development of RS technology and the increasing availability of satellite imagery, an increasing number of datasets for oil spill detection have been proposed. Liu et al. selected the Baltic Sea as the study area and constructed oil spill and dark spot detection datasets [84,85], which used ENVISAT satellite imagery, based on oil spill information released by HELCOM. Dark spot detection serves as an essential preliminary step in oil spill detection, enabling the identification of potentially contaminated regions over large marine areas [84]. The oil spill detection dataset provides high-quality samples. Liu et al. combined the knowledge graph method to achieve more effective oil spill identification [85]. Trujillo-Acatitla et al. [86] combined oil spill information released by NOAA and EMSA and acquired 685 full-resolution Sentinel-1 SAR GRD images from the Copernicus Sentinel Program to construct an oil spill detection dataset. Compared with the M4D dataset, the constructed dataset contains a larger number of oil spill and look-alike images, providing a more comprehensive representation of marine oil spill conditions. Specifically, 1200 oil spill images and 1200 non-spill and look-alike images were used for training, while 150 oil spill, 150 non-spill, and 150 look-alike images were used for testing.

In addition, optical RS has become an important data source for oil spill detection, leading to the development of several related datasets. Duan et al. [88] constructed a Hyperspectral Oil Spill Database (HOSD) based on 18 hyperspectral images for oil spill detection. The dataset uses imagery acquired by AVIRIS, covering a spectral range of 365–2500 nm. HOSD provides an effective experimental platform for hyperspectral oil spill detection. However, since the dataset is pixel-based, each sample is treated independently, which limits the incorporation of spatial contextual information. Therefore, compared with image-based semantic segmentation datasets, its applicability to complex real-world scenarios is relatively limited. De Kerf et al. [87] constructed a dataset for port oil spill detection using RGB images acquired by UAVs. The dataset consists of three classes and contains 1268 sample images, with 811, 203, and 254 images used for training, validation, and testing, respectively. Specifically, 994 images contain oil spill targets, 929 include water targets, and 1106 contain other types of objects. This dataset provides a pioneering foundation for oil spill monitoring in port environments. The UAV platform enables rapid and flexible data acquisition, and the captured RGB images offer high spatial resolution [90]. Although the dataset does not include additional spectral bands, its high-resolution visual information and realistic scene characteristics make it a valuable resource for nearshore oil spill detection research.

3. Literature Review of Oil Spill Monitoring

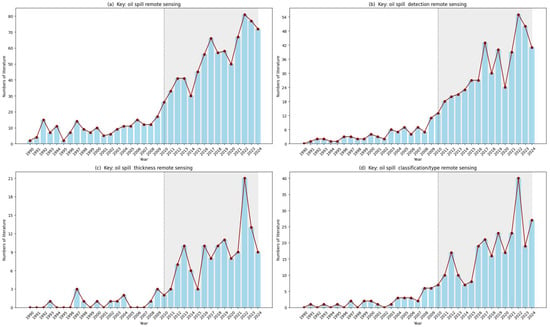

Accurate and timely monitoring of oil spills plays a vital role in the effective management of sudden spill events and in ensuring a swift, coordinated emergency response. With continuous advancements in RS technology and AI methods, AI-driven RS methods have become an essential and efficient tool for marine oil spill monitoring. Hence, we systematically analyzed relevant literature primarily sourced from the Web of Science, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the latest advancements in remote sensing applications for oil spill monitoring. Specifically, we employed the keywords “oil spill remote sensing”, “oil spill detection remote sensing”, “oil spill thickness remote sensing”, and “oil spill classification/type remote sensing” to retrieve relevant publications. Figure 3 illustrates the trend of publications retrieved using our selected keywords from 1990 to 2024, demonstrating a steady rise in research interest in this field, which has stabilized in recent years. Notably, we can observe a notable surge in research on oil spill RS after 2010, which can be driven by the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico. This event provides a unique opportunity for field application and integration of new sensor technology, thereby promoting the development of oil spill monitoring methods based on RS technology [91]. In addition, since 2015, oil spill monitoring methods have also developed rapidly, largely driven by the advances in deep learning methods and RS technology. Specifically, the launch and operation of satellites such as Sentinel-1 and Gaofen series have provided abundant high-quality RS data. Meanwhile, the introduction of deep learning methods has significantly improved the automation and accuracy of oil spill detection, promoting the transition of oil spill monitoring toward more intelligent and precise methods.

Figure 3.

The trend of publications retrieved using our selected keywords from 1990 to 2024.

Numerous methods based on RS imagery have been proposed for oil spill monitoring, and previous studies have reviewed the integration of machine learning, deep learning, and RS technology for oil spill detection [58]. However, there is still a lack of comprehensive reviews that systematically summarize the applications of AI methods in combination with RS technology for oil spill detection, classification, and thickness estimation. Therefore, this study provides an in-depth review and summarizes recent advances in these areas, aiming to offer a systematic reference and valuable insights for future research in this field.

3.1. RS for Oil Spill Detection

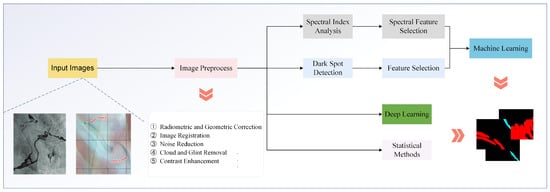

Figure 4 shows a general framework integrating AI methods with multi-source RS imagery for oil spill detection. First, the input images undergo a series of image preprocessing steps to improve data quality and reduce interference. Then, the images can be analyzed using spectral index analysis for feature extraction or dark spot detection to identify potential oil spill areas. Extracted features are further processed through spectral signature matching or feature selection, which are used to train machine learning models to detect oil spills. Moreover, deep learning enables the automatic extraction of high-level features for OSD, whereas statistical methods offer conventional pattern recognition capabilities.

Figure 4.

A general framework integrating AI methods with multi-source RS imagery for oil spill detection.

3.1.1. Optical RS for Oil Spill Detection

After an oil spill occurs, the oil spill spreads over the sea surface, damping small-scale waves and altering the surface roughness. These changes create visible texture contrasts between the oil-covered and clean water areas in RS imagery, thereby enabling oil spill detection using optical RS [48]. Traditional methods primarily identify oil spill areas by applying statistical methods or analyzing optical properties. Song et al. proposed an improved multi-dimension Chan–Vese model based on region for OSD [92]. Shi et al. utilized a peak-trough detection method to characterize the different spectral groups, thereby determining the spectral features of oil emulsions and Sargassum [11]. Ren et al. proposed a multi-angle polarization measurement approach that computes parameters such as amplitude ratio, phase delay, refractive index, and degree of polarization to characterize pixel-level optical properties for accurate OSD [93]. Zhu et al. proposed a novel separability index to assess spatial heterogeneity and effectively differentiate oil spills from surrounding waters [94]. Zhao et al. introduced the Spectral Gene Extraction method, enabling robust detection performance under limited training data conditions. Specifically, the maximum intra-class similarity (LIS) strategy and the maximum inter-class difference (LID) strategy were first used to extract the spectral genes of oil spill samples. Then the leakage condition was determined by calculating the similarity between the extracted spectral genes and the DNA-encoded image [95]. Xie et al. proposed two fully automatic models for oil spill detection based on UV imagery. The first is a binary classification model based on an adaptive threshold. The second is an unsupervised image segmentation model using image clustering and grayscale histogram analysis. Experimental results showed that both models accurately detected thin oil films under stable imaging conditions [96]. Sulma et al. used an oil spill index threshold to segment oil and non-oil targets from RS images [12]. These methods are fast and effective for OSD. However, reliable operation requires substantial expert knowledge and experience for parameter and threshold selection. In addition, performance can vary significantly under different illumination and marine conditions.

With the rapid development of machine learning techniques, a variety of machine learning-based methods have been proposed for marine OSD. Shi et al. extracted texture features using the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) and subsequently employed the Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) clustering algorithm to classify oil spills and seawater regions [97]. Gai et al. first extracted texture features using GLCM, then constructed a decision tree classifier to identify the oil spill based on spectral and texture features [98]. Sun et al. used a fuzzy mean clustering algorithm to cluster the color feature space, and then determined the segmentation result of oil spill area according to the oil spill color model [99]. Li et al. combined low-level and high-level visual saliency features to detect oil spills. This method first utilized a simplified GBVS model and spectral similarity matching to locate oil regions, then the oil spill saliency was calculated to extract the region of interest (ROI). Finally, a genetic neural network is used for image segmentation [100]. Pelta et al. classified polluted and non-polluted pixels using data normalization, band selection, dimensionality reduction, and a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) model, achieving high-accuracy pollution area identification under complex conditions where spectral features were not clearly distinguishable [15]. Zhang et al. utilized different data combinations to train decision tree classifiers for OSD and explored the impact of different polarization features using open-source POLDER/PARASOL polarization time-series data [101]. Sun et al. proposed a framework for OSD under strong sun glint conditions. This method first uses the preprocess steps to enhance the target boundary contrast and mitigate the influence caused by sun glint. Then linear clustering and decision tree are used to distinguish oil spill [13]. Duan et al. removed noisy bands using a noise estimation method and applied PCA to reduce dimensionality. They estimated oil spill probabilities with an isolation forest, generated pseudo-labels by clustering, and refined SVM detection results using an extended random walk model [88]. Jiang et al. proposed an object-oriented classification method based on multiple feature parameters and fuzzy logic for detecting strip-shaped marine oil spills in narrow waterways [102]. Arslan et al. rapidly detected oil spills using principal component analysis with different band combinations [73]. Machine learning-based methods can learn patterns from training data and exhibit good robustness across different marine environments. Compared to traditional methods, they are less susceptible to noise interference. However, most conventional machine learning approaches still depend on manual feature extraction, which is time-consuming and may lead to the loss of critical information, particularly when handling complex, high-dimensional RS data.

Recent progress in computer vision has promoted the use of deep learning methods in marine OSD. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that rely on manually designed features, deep learning-based methods can automatically learn hierarchical representations from data, thereby eliminating the need for manual feature extraction and improving generalization performance. To overcome the limitations of the dataset, a series of methods has been proposed [75,103,104]. Duan et al. proposed a self-supervised learning method for OSD, which employed the spectral and spatial enhancement technology to improve the robustness of the model and achieved strong generalization performance on unlabeled hyperspectral data [103]. Yang et al. proposed a decision fusion method based on fuzzy membership degree to combine deep and shallow learning methods. Although the shallow learning method, such as SVM, often performs better on small datasets, selecting an appropriate shallow learning method can be challenging [75]. Cai et al. first used a small-scale marine oil spill dataset captured by the Landsat-8 satellite as the training set. Then, they employed the Single Image Generative Adversarial Network (SinGAN) for dataset augmentation and applied transfer learning to pretrain YOLOv8, thereby enhancing model performance [104]. In addition, some methods have achieved improved detection performance by training models on labeled samples. Seydi et al. designed a residual kernel convolutional neural network with multi-scale and multi-dimensional structures to enhance the detection accuracy of marine oil spills. Due to the method including several complex modules, more time for training was required [105]. Wang et al. proposed a Spectral–Spatial Feature Integration Network (SSFIN) for marine oil spill detection. The 1D-CNN and 2D-CNN were employed to extract spectral and spatial features, which effectively address the classification errors of traditional methods that rely on single-feature representations [16]. Hu et al. proposed spectral–spatial feature extraction (SSFE), which similarly used the 1DCNN and 2DCNN to extract the combined spatial-spectral feature to improve the performance of OSD [106]. Compared with SSFIN, this method employed PCA to reduce feature dimensionality, and the L2 regularization, class weight, and dropout were used to address the issue of sample imbalance. Du et al. introduced a Class-Balanced F loss function designed to enhance CNN performance in multispectral oil spill detection tasks, particularly when dealing with class imbalance issues [107]. Sun et al. investigated the performance of three commonly used deep learning models, namely UNet, BiSeNetV2, and DeepLabV3+, combined with attention modules for oil spill detection. The used RS images were acquired from the Sentinel-2 MSI, Landsat-8 OLI, and Landsat-9 OLI-2 satellites. Experimental results demonstrated that UNet combined with the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) significantly outperformed the other methods [108].

Furthermore, due to the interference of sunlight and shadows, the spectral differences between seawater and oil spills are often weakened. To address this issue, Yang et al. integrate dual-branch spatial and spectral information based on a graph convolutional network architecture, consisting of a spectral feature extraction module, a spatial feature extraction module, and a spatial–spectral information fusion module [76]. The environment near ports is more complex, and the risk of oil spills is higher, requiring real-time monitoring and detection. With the development of UAV technology, its advantages, such as high mobility, flexible deployment, and wide coverage, can effectively meet the requirements of port oil spill monitoring [87,90,109]. De Kerf et al. explored the application of UAVs in oil spill monitoring and constructed a dataset based on RGB images captured by UAVs over port areas [87]. Dong et al. proposed a novel Scene-category Guided Dual-branch Network (SGDBNet), which effectively addresses the challenges of detecting oil spills in complex port environments, small-scale targets, and irregular boundaries in UAV RS imagery [109]. Compared with traditional statistical and machine learning methods, deep learning methods offer superior feature extraction and detection accuracy. However, the real-time performance remains a serious limitation. In addition, the cost of labeled data is extremely high, and the limited availability of annotations restricts the generalization capability of models across diverse scenes. Although a series of unsupervised and semi-supervised methods have been proposed to address this issue, data generated by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) may introduce bias, and the performance of unsupervised methods is still unstable.

3.1.2. SAR for Oil Spill Detection

Although optical RS imagery provides an efficient means for oil spill monitoring with superior temporal resolution and strong detection capability, its applicability remains limited under adverse weather conditions. In cloudy or foggy environments, the use of radar technologies such as SAR can significantly enhance monitoring effectiveness. SAR enables all-weather and day-and-night monitoring of marine oil spills, remaining unaffected by weather conditions and illumination. Therefore, numerous methods based on SAR imagery have been developed for OSD [30,86,110,111,112,113,114,115,116].

In the early stage, the methods based on SAR imagery mainly concentrated on detecting oil spills by extracting grayscale, textural [110,113], contour [117], and morphological [118] features. In general, traditional methods follow a three-step procedure comprising dark spot detection, feature extraction, and oil spill identification [28,119]. Garcia-Pineda et al. proposed a texture-classifying neural network algorithm (TCNNA). The method extracts 46 feature vectors, including textural descriptors, and employs an artificial neural network to detect oil spills [110]. Solberg et al. applied an adaptive thresholding technique to segment dark spots in SAR imagery, and a large number of features were then calculated for each segmented region. Finally, these features were classified using a combination of statistical and rule-based approaches to identify oil spills [28]. Topouzelis et al. proposed a novel feature selection and classification method for oil spill detection based on decision tree forests, formulated as a binary classification problem to distinguish oil spills from look-alike phenomena. Experimental results indicated that a combination of 9 features achieved the most effective discrimination. However, under complex and dynamic marine conditions, the optimal feature combination may vary, leading to inconsistencies in detection performance [111]. Zhao et al. employed the Otsu thresholding method to segment SAR imagery and utilized a feedforward backpropagation neural network to classify dark spots into oil spills and look-alike features. During this process, morphological filtering was applied to suppress speckle noise in the SAR images, which significantly improved the classification accuracy of the model [112]. Lang et al. developed a multi-feature fusion classification approach for oil spill dark spot segmentation using single-polarization SAR imagery. Then, the method integrates gray-level, geometric, and textural features within an artificial neural network framework, enabling accurate discrimination of oil spills from look-alike phenomena [120]. Xu et al. developed a marine oil spill identification approach combining Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), a Random Forest classifier, and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). The method first preprocesses marine radar images to extract HOG features, employs the Random Forest classifier to detect active oil regions, and then applies PSO to adaptively optimize dual threshold parameters for accurate oil spill segmentation [121].

In addition, several methods adopt feature selection to enhance the accuracy and robustness of oil spill detection models. Chehresa et al. extracted 74 distinct features, including 32 texture, 19 geometric, 19 physical, and 4 contextual features. Then, an evolutionary algorithm was employed to select an optimal feature subset. Finally, a Bayesian network was used to classify dark spots, effectively distinguishing oil spills from look-alike phenomena [122]. Zhou et al. adopted the minimum redundancy and maximum relevance (mRMR) to select the features, further utilized the SVM for image classification, effectively distinguishing oil spills from look-alikes [123]. Lentini et al. proposed RIOSS for detecting oil spills from SAR imagery. The method involves image segmentation, SAR feature extraction, and classification using the random forest algorithm to distinguish oil slicks from look-alike phenomena. Among the 42 extracted features, 11 optimal features were selected, with the fractal dimension and the mean absolute gradient showing particularly strong discriminative capability between oil spills and look-alike [114]. Vasconcelos et al. combined polarimetric features with texture features derived from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM). Then, a random forest classifier was employed for image classification. In the methods, the Gini index was used to remove irrelevant features, which can improve the performance of the model [113]. Carvalho et al. investigated the performance of six machine learning algorithms, including Naive Bayes, K-nearest Neighbor, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Artificial Neural Network, as classifiers for oil spill detection. Furthermore, several feature selection techniques, such as the Gini coefficient, were applied to assess the contribution of different features to model performance [29]. Aghaei et al. applied a high-order local filter to reduce noise in SAR imagery. A multi-objective grey wolf optimization algorithm combined with K-means clustering was then used to determine the optimal segmentation threshold. Legendre moments were extracted as features and classified using a support vector machine. Finally, a hierarchical region-based level-set method was employed to delineate oil spill boundaries. The method achieved high accuracy and robustness, even for noisy images with heterogeneous textures and weak boundaries [119]. While these traditional methods have proven effective, they rely heavily on manual feature extraction and expert interpretation. This reliance restricts their efficiency and robustness when applied to complex marine environments.

With the rapid advancement of deep learning, researchers have increasingly focused on employing deep learning techniques for oil spill detection from SAR imagery. These approaches aim to address several major challenges inherent in SAR-based oil spill detection, including limited labeled data, image distortion, and the interference of look-alike phenomena. To address the limitation of insufficient training data, techniques such as generative adversarial networks (GANs) [115,124], transfer learning [32], few-shot learning [125], and pseudo-labeling [126,127] are commonly employed to enhance model generalization and detection performance. Fan et al. proposed a multi-task generative adversarial network (MTGAN) framework for marine oil spill detection. MTGAN addresses the challenge of distinguishing oil spills from look-alikes in SAR imagery by integrating two GANs within a unified architecture. The first GAN performs oil spill classification, while the second generates corresponding semantic segmentation maps. This design enhances the discrimination capability between oil spills and look-alike regions and achieves high detection accuracy even with limited training samples [115]. Ahmed et al. designed a segmentation framework based on a conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN) combined with an improved Seg-Net for marine oil spill detection using Sentinel-1 SAR imagery. The model employs a Patch-GAN discriminator and demonstrates superior segmentation accuracy over the conventional Seg-Net, even with limited training data [124]. Chai et al. proposed TransOilSeg, a model that employs transfer learning to capture generalized feature representations and utilizes a gradient aggregation algorithm to overcome the limitations caused by data imperfections [32]. Jiang et al. proposed a pseudo-label-based semi-supervised semantic segmentation method for SAR oil spill detection, which adopts a dual-student network architecture that integrates consistency and stability constraints with pixel-level contrastive learning to enhance the generalization and segmentation accuracy under limited labeled data conditions [126]. Cui et al. proposed an enhanced unsupervised domain adaptation method, which enables cross-event oil spill segmentation by transferring knowledge from historical SAR oil spill data to new spill events with limited samples. The framework integrates domain adaptation, prior-knowledge-based target domain partitioning, and iterative pseudo-label refinement. However, the method still relies on manually defined priors such as satellite parameters and wind speed, and its performance may be affected by the quality of initial pseudo-labels when faced with large domain gaps or scarce target samples [127]. Song et al. proposed a cross-domain few-shot SAR oil spill detection network named HA-CP-Net. It uses a hybrid attention mechanism to effectively extract global and local features of oil spill images. A class-aware loss function is designed to compact intra-class features and separate inter-class ones, improving the discrimination between real and suspected oil spills under few-shot conditions [125]. These methods can achieve robust oil spill detection performance even with a limited number of training samples. However, from the perspectives of generative adversarial networks, transfer learning, pseudo-labeling, and few-shot learning, several limitations remain. GAN-based methods may suffer from unstable training and mode collapse, leading to inconsistent generation quality. Transfer learning approaches are highly dependent on the relevance between source and target domains, which can limit their adaptability. Pseudo-labeling methods risk propagating labeling errors, especially in noisy marine SAR data. Few-shot learning techniques, while data-efficient, often struggle to generalize under complex and dynamic sea surface conditions.

Hence, with the release of labeled SAR datasets for marine oil spills, an increasing number of semantic segmentation-based approaches have been developed [80,82,86]. These methods perform pixel-level classification, enabling accurate and fine-grained segmentation of different targets in SAR imagery. Krestenitis et al. constructed a dataset based on Sentinel-1 imagery containing five classes and evaluated the performance of various semantic segmentation algorithms. Experimental results demonstrated that the DeepLabv3+ model achieved the best performance, reporting the highest accuracy and inference time [80]. Shaban et al. proposed a two-stage method for SAR oil spill detection. In the first stage, a 23-layer CNN is employed to classify image patches as oil spill or non-oil spill. In the second stage, a U-Net network is utilized to perform pixel-level segmentation for more precise detection [128]. Similarly, Trujillo-Acatitla et al. also introduced a two-stage deep learning framework. The CNN and U-Net are used for classification and segmentation, respectively [86]. Zhang et al. proposed a dual-polarization oil spill detection method for Sentinel-1 SAR imagery by integrating superpixel-based image stretching with a deep CNN. The image stretching step enhances the visual distinction of oil spill regions, while the semantic segmentation model enables precise delineation of spill boundaries [129]. Wang et al. proposed BO-DRNet, an improved deep learning model based on polarimetric features for oil spill detection in SAR imagery. The method integrates the ResNet-18 and DeepLabv3+ architectures, while employing Bayesian Optimization (BO) for hyperparameter tuning, which significantly enhances feature extraction capability and the utilization of multi-scale information [70]. Hasimoto-Beltran et al. proposed a multi-channel deep neural network for oil spill detection in SAR imagery. The model constructs a three-channel input comprising the original SAR image, variance map, and wind field map, and integrates U-Net with ResNet architectures for pixel-level semantic segmentation. Experiments conducted on a self-developed multi-scale oil spill dataset demonstrated high detection accuracy and robustness across diverse marine conditions [116]. Li et al. designed a self-evolving deep learning method to enable fully automatic oil spill detection in SAR imagery without the need for manual labeling or dataset construction. The method employs a closed-loop optimization framework composed of three interconnected modules: oil spill detection, new training data generation, and model enhancement. Specifically, dual models are first used to detect oil regions and their boundaries, followed by adaptive thresholding to automatically produce high-quality training data. Finally, the model parameters are iteratively updated to progressively enhance detection performance [130]. Wang et al. proposed a novel polarimetric feature, termed relative feature, derived from the Cloude–Pottier target decomposition for oil spill detection. Experimental results demonstrated that incorporating the relative feature into the U-Net architecture significantly improved detection performance [131]. Soh et al. optimized a U-Net encoder-decoder framework for marine oil spill detection by introducing depthwise separable convolutions, group normalization, and a focal loss function, achieving higher accuracy with reduced computational cost [132].

The interference of look-alike phenomena and noise poses significant challenges to reliable oil spill detection. Specifically, the presence of look-alike phenomena, such as low-wind areas, algal blooms, or ship wakes, often leads to misclassification and significantly reduces the reliability of oil spill detection models. Moreover, strong speckle noise, nonuniform backscatter intensity, and indistinct boundaries further complicate accurate segmentation, reducing model robustness in complex marine environments. To mitigate these effects, a variety of advanced methods have been developed. Li et al. applied a slicing strategy during preprocessing to mitigate limited data availability and employed a semantic segmentation model based on U-Net to distinguish oil spills from look-alike phenomena [133]. Song et al. developed a scene-adaptive oil spill detection network integrating dynamic convolution and boundary constraint modules to enhance the accuracy of Polarimetric SAR (PolSAR) data analysis in complex marine environments. The boundary constraint module refines spill contour delineation, which effectively addresses challenges such as algae blooms, wave shadows, and wind-induced texture variations [134]. Prajapati et al. proposed GSCAT-UNET, a deep learning architecture composed of a Spatial Channel Attention Gate (SCAG), a Triple-Level Attention Module (TLM), and a Global Feature Module (GFM). These components enhance the extraction of global oil spill features, enabling effective detection and improved discrimination between oil spills and look-alike phenomena [31]. Zhu et al. proposed a Context- and Boundary-supervised Detection Network (CBD-Net) for oil spill detection in marine SAR imagery. This method integrates multi-scale feature fusion and enhanced boundary supervision, and can effectively identify oil spill regions in images characterized by uneven intensity, high noise, and blurred boundaries [82]. Zhai et al. improved the U-Net architecture by introducing a dual attention mechanism in the encoder stage to adaptively integrate local features with global dependencies, enhancing multi-scale feature representation. A Gradient Profile (GP) loss function was further employed to refine boundary delineation in noisy SAR images with blurred and nonuniform spill regions [135]. Li et al. proposed the Dual-Stream U-Net, which integrates an edge feature extraction module and a multi-scale alignment module to capture both local and global features for oil spill detection. The edge features are utilized to suppress speckle noise in SAR images and improve localization accuracy [136]. Dong et al. proposed FFDNet-TransUNet, a hybrid framework combining FFDNet and TransUNet architectures. FFDNet, a fast and flexible image denoising algorithm based on deep CNN, is employed to suppress speckle noise and enhance image quality [137]. The denoised output is subsequently processed by TransUNet for accurate oil spill segmentation, achieving superior performance in complex sea surface environments [138]. Wu et al. proposed a composite OSD framework called SAM-OIL for marine oil spill monitoring. The method first employs the YOLOv8 algorithm to identify the categories and bounding boxes of relevant objects. Then, an improved large model, the Segment Anything Model (SAM), is used to generate class-agnostic masks. Finally, the masks are fused with the category information to produce the final OSD results [89]. Dong et al. proposed shape-aware and adaptive strip self-attention guided progressive network (SAGPNet), a deep learning model designed to tackle the challenges of marine OSD in SAR imagery. It incorporates shape-aware modules, an adaptive stripe self-attention mechanism, and a progressive learning framework, which significantly enhance its capability to detect small oil spills and distinguish them from look-alike objects such as ocean waves and biogenic films [30]. These methods have achieved remarkable accuracy in oil spill detection and segmentation. However, the generalization capability has not been fully validated under diverse and dynamic marine environments. Second, the semantic segmentation models employed are computationally intensive, resulting in high memory consumption and limited real-time applicability. Third, their performance often depends on large annotated datasets and careful hyperparameter tuning, which restricts scalability and operational efficiency in practical monitoring systems.

3.1.3. Thermal Infrared Oil Spill Detection

Compared with optical and SAR sensors, TIR sensors offer distinct advantages for oil spill detection. TIR sensors can directly capture the temperature contrast between oil films and surrounding seawater, enabling reliable detection even under low illumination or moderate cloud conditions. Unlike optical sensors, TIR is less affected by sunlight reflection and atmospheric scattering. In addition, it can complement SAR observations by providing thermal information that helps distinguish oil slicks from look-alike phenomena such as low-wind areas or organic films. These characteristics make TIR imagery a valuable component in oil spill monitoring systems. Casciello et al. developed a robust satellite-based approach for oil spill detection using NOAA-AVHRR TIR bands. The method identifies oil spills through standardized anomaly detection and achieves high reliability with a low false alarm rate [41]. De Kerf et al. proposed an oil spill detection method based on TIR imagery and CNNs. Multiple CNN architectures and feature extractors were tested to optimize real-time detection performance [42]. Li et al. introduced two TIR-based oil spill detection methods using support vector machine classifiers. The first approach employs a histogram of oriented gradients features and a radial basis function kernel SVM to extract geometric and optical-invariant characteristics for efficient oil spill identification [43]. The second method utilizes gray-level co-occurrence matrix texture features, including energy and correlation, combined with an SVM model to achieve accurate detection of small-scale oil spills [44]. These methods achieve reliable oil spill detection by exploiting the thermal contrast between oil films and surrounding seawater. However, their effectiveness is limited to conditions with sufficient temperature gradients. Under low thermal contrast, thin oil layers, or rapidly changing sea surface temperatures, the detection accuracy declines significantly, restricting the applicability of TIR techniques in large-scale or long-term monitoring.

3.1.4. Multi-Source Data for Oil Spill Detection

Traditional OSD methods typically rely on a single RS data source. SAR enables all-weather, day-and-night monitoring, but it often suffers from a high false alarm rate and difficulties in distinguishing oil spills from lookalike phenomena. Optical RS provides high spatial resolution and rich spectral information. However, it is susceptible to sunlight reflection, cloud cover, and atmospheric interference. Differences in spatial and spectral resolution also impose limitations on the accuracy and applicability of oil spill detection. TIR imagery has limited spatial resolution and struggles to detect thin oil films. These limitations have motivated researchers to investigate multi-source RS approaches, which exploit the complementary advantages of different sensors to improve detection accuracy and robustness [139,140].

Pisano et al. employed both SAR and optical RS data for OSD. First, this SAR module extracts a series of geometric and radiometric features from the SAR imagery, which are then analyzed using the Oil Spill Automatic Detector (OSAD) to discriminate between oil spills and look-alike phenomena. The OSAD, proposed by Nirchio et al., classifies the extracted features primarily through multivariate linear regression [141]. Second, the optical module serves as a complementary approach, applicable under cloud-free and daytime conditions, and is particularly effective for identifying thin oil films and heavily contaminated areas [139]. Carvalho et al. employed linear discriminant analysis on multi-source datasets to enhance the discrimination between oil spills and look-alike phenomena [51]. Du et al. initially fused optical, ultraviolet, and thermal scanner imagery to produce a high-resolution dataset with ten bands spanning the ultraviolet–visible–near-infrared spectrum. Then, MS3OSD, a parallel dual-branch architecture integrating a CNN and a Vision Transformer, was employed for joint spatial–spectral feature extraction from the fused data. Experiments demonstrated the robustness and accuracy of MS3OSD in oil spill detection under varying illumination conditions [140]. Shin et al. proposed a novel framework for oil spill detection that integrates SAR and optical imagery. Specifically, oil spill information is first extracted from optical images using the Optical Slick Index (OSI) and thresholding techniques. Then, deep learning methods are applied to SAR data to identify oil spill features. In the third step, the detected results are manually validated to confirm their authenticity. Finally, a new dataset is constructed based on the verified results to train deep learning models for improved detection performance. It is worth noting that the choice of deep learning model depends on the specific platform characteristics and application scenario [54]. Trongtirakul et al. proposed an automated oil spill detection method integrating TIR and optical polarization imaging. The method applies multilevel thresholding segmentation and contrast enhancement techniques to achieve more precise delineation of oil spill boundaries [52].

Furthermore, to enhance the accuracy and reliability of OSD methods, several studies have integrated SAR or optical RS data with auxiliary information such as wind speed, temperature, and Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, enabling a more comprehensive analysis and discrimination of oil spill events [49,50,142]. Salberg et al. and Garello et al. integrated SAR observations with wind speed and external AIS information to improve the confidence and reliability of oil spill detection outcomes [49,50]. Chen et al. employed a UNet model with attention gates to detect oil spills from Sentinel-1 PolSAR imagery. Compared with methods that rely solely on polarization information, this method incorporates sea surface wind speed data during both training and testing, which significantly enhances the performance of the oil spill detection model [142]. Amri et al. developed segmentation models based on FC-DenseNet and Mask R-CNN for detecting oil spill regions in SAR imagery. Their multimodal deep learning framework further combines SAR data with environmental context information, such as wind speed and infrastructure location, to improve detection accuracy and reduce false positives [143]. Liu et al. introduced a knowledge graph inference framework that integrates SAR imagery, atmospheric and oceanic model data, vector information, and textual sources to address data isolation issues. The framework employs rule-based filtering and graph neural networks (GNNs) to achieve robust oil spill identification [85]. Liao et al. trained a DeepLabv3+ model using 35 Sentinel-1 images, incorporating PolSAR polarization information and meteorological conditions to improve oil spill detection accuracy [144]. Considering that polarization decomposition parameters can enhance the distinction between oil spills and look-alike features, Ma et al. employed DeepLabv3+, which integrates polarization features, polarimetric decomposition parameters, and meteorological data from Sentinel-1 SAR imagery to achieve high-precision oil spill detection in Jiaozhou Bay [145].

These studies demonstrate that the integration of heterogeneous RS data and auxiliary information can substantially improve the accuracy, robustness, and generalization capability of oil spill detection models. The combined use of multi-sensor observations and contextual information enables more reliable identification and characterization of oil spills under diverse environmental and illumination conditions. However, achieving effective feature alignment and information fusion across heterogeneous data sources remains a critical challenge. Discrepancies in spatial resolution, temporal coverage, spectral characteristics, and data representation often result in inconsistency and information loss during integration. Overcoming these issues is essential for the development of unified and scalable frameworks for multi-source oil spill detection.

3.2. RS for Oil Spill (Type) Classification and Thickness Estimation

Figure 5 illustrates a general framework of AI and RS for oil spill type classification and thickness estimation. Specifically, existing methods can be categorized into two groups according to data acquisition strategies: real satellite imagery and outdoor simulated experimental data. Real satellite data are affected by various environmental factors such as atmospheric interference, sea surface roughness, and illumination variations, and therefore often require extensive preprocessing and noise reduction. In contrast, outdoor simulated data are collected under controlled conditions, offering higher data quality, well-defined ground truth, and greater flexibility for model validation. The modeling methods based on these two data sources can be further divided into traditional machine learning and deep learning methods. Traditional machine learning techniques include K-nearest neighbor, random forest, Bayesian network, and decision tree classifiers. Deep learning methods can be broadly classified into pixel-based and image-based frameworks, which differ in their spatial feature representation and learning strategies.

Figure 5.

The general framework of AI and RS for oil spill type classification and thickness estimation.

3.2.1. Oil Spill (Type) Classification

Marine oil spills can be classified based on water content or the type of spilled substance. From the perspective of water content, oil spills are commonly divided into pure oil, water-in-oil emulsions, and mousse-like mixtures [21,146]. As weathering progresses, emulsification increases the water content, altering the physical properties and viscosity of the oil, which complicates detection and cleanup operations. From the perspective of spilled substance, oil spills are categorized according to the type of petroleum product involved, such as crude oil, diesel, or lubricants, each exhibiting distinct optical, thermal, and chemical characteristics [62,147,148]. These differences significantly influence the environmental persistence, spreading behavior, and required response strategies. Therefore, accurate classification of oil spill types is crucial for assessing ecological risks and implementing targeted mitigation measures. Optical RS and SAR imagery are the two most commonly used data sources for oil spill type classification [62,147,148]. Different types of oil spills exhibit distinctive spectral signatures due to variations in their chemical composition, thickness, and degree of emulsification. These spectral characteristics enable the discrimination of oil types based on their reflectance and absorption properties across multiple wavelength bands. In contrast, SAR captures the microwave backscatter from the sea surface, which is highly sensitive to surface roughness [33,34,35]. Oil films dampen short surface waves, leading to reduced backscatter intensity and the appearance of dark patches in SAR imagery. Since different oil types modify surface roughness to varying degrees depending on their viscosity and concentration, SAR data can be effectively used to analyze oil type and spreading behavior, even under adverse weather conditions or low illumination.

Laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) enables the rapid identification of oil types based on their unique fluorescence spectra. Loh et al. developed a portable LIF spectrometer for rapid on-site identification of four types of oil, including marine diesel, light fuel oil, heavy fuel oil, and lubricating oil. In combination with chemometric modeling, fluorescence spectra were classified using Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and Support Vector Machine Discriminant Analysis (SVM-DA), enabling fast and reliable screening of oil types in field conditions [147]. Zhao et al. proposed a multi-condition oil spill classification method for ice-covered regions using LIF technology. The method established a total of twenty-four classification categories by collecting fluorescence spectra of six types of oil under four ice conditions. Then employed the Golden Sine Algorithm (Gold-SA) to optimize the CatBoost model, achieving highly accurate identification of oil type, volume, and ice coverage conditions [148]. Hyperspectral RS, characterized by its high spectral resolution, can effectively distinguish spectral differences among various oil types and has been widely applied in oil spill type identification [21,26,146,149]. Yang et al. utilized hyperspectral RS to analyze the spectral characteristics of five common marine oils, including crude oil, fuel oil, diesel, gasoline, and palm oil. Based on the selected characteristic bands, a support vector machine model was developed to accurately classify the oil types [26]. Li et al. combined hyperspectral RS data with machine learning algorithms, including random forest, support vector machine, and deep neural network (DNN), to classify four common marine oil spill types. The results showed that the DNN and its optimized version (DP-DNN) achieved the best accuracy and efficiency [150]. Jiang et al. developed a classification method based on an adaptive long-term momentum estimation optimizer (ALTME) and a 1D-CNN to improve oil spill type identification using hyperspectral data [151]. Zhang et al. conducted outdoor simulation experiments to determine the most discriminative spectral bands. Then, utilizes the PCA for dimensionality reduction and employs a random forest algorithm to classify crude oil, water-in-oil emulsion, oil-in-water emulsion, and seawater [149]. Xie et al. proposed a semi-supervised learning model that combines image segmentation and a 1D-CNN to classify oil emulsions on the sea surface, reducing the need for manual labeling [21]. Several studies have also shown that medium-resolution optical RS images, such as those from Landsat, can distinguish different oil spill types [146,152]. Lu et al. used optical RS imagery collected by the Landsat satellite and a decision tree model to classify water-in-oil (WO) and oil-in-water (OW) emulsions [146].

Methods that rely only on spectral features for oil spill classification often ignore spatial characteristics, which can weaken robustness and cause misclassification when different oil types have similar spectra or are affected by environmental noise. In complex marine environments, variations in oil film thickness, shape, and sea background can further reduce accuracy. To address these limitations, recent studies have integrated spectral information with spatial distribution features to improve the reliability and precision of oil spill classification. Yang et al. proposed an oil spill type identification method based on the RPnet deep learning model, achieving precise classification of different oil types by integrating spectral and spatial features [19]. Wang et al. introduced GCAT to extract multi-level spectral–spatial features for precise oil spill type and thickness classification [153]. Kang et al. introduced a self-supervised spectral–spatial transformer network (SSTNet) that uses contrastive learning to extract discriminative features and achieves accurate classification of different oil spill types with only a few labeled samples [154]. Zhang et al. first utilized a multiscale superpixel-level group clustering framework to select the spectral feature bands with strong separability, then employed the dual-attention model to classify the oil spill and its emulsions. The methods consider both the spatial-spectral features, which enhance the performance of the model [77]. Huang et al. employed a standard deviation–mutual information (SD-MI) feature selection method to extract key spectral bands and utilized a 3D-CNN to simultaneously capture spectral and spatial features of targets, achieving high-accuracy classification of marine oil emulsions (water-in-oil and oil-in-water) and crude oil [20]. Jiao et al. integrated spectral, spatial, and geometric features using a deep learning model to classify and estimate oil spill type and thickness, while using changes in reflectance at blue and near-infrared wavelengths to quantify the characteristics of non-emulsified and emulsified oil spills [22].

To achieve all-weather oil spill monitoring, several studies have focused on using SAR imagery for oil spill type classification. Tian et al. explored the effectiveness of SAR polarization features in distinguishing heavy, medium-viscosity, and light oils [33]. Genovez et al. applied a random distance region classification method to PolSAR data to detect and classify bio-oil, emulsified oil, and crude oil [34]. Hassani et al. used an SVM algorithm to extract key features from UAVSAR polarimetric radar data, successfully classifying thick oil, thin oil, oil/water mixtures, and clear water [35]. Although these methods can roughly distinguish between different oil types, their performance is highly sensitive to environmental factors such as wind speed, sea state, and sensor noise, which often degrade classification accuracy and consistency. Hence, multi-source RS data fusion is adopted to mitigate the limitations of single-sensor methods. Yang et al. proposed a multi-dimensional feature extraction method combining hyperspectral and TIR RS, significantly improving the identification accuracy of oil spill types and oil film thickness while exploring the potential of TIR data in classifying high-concentration water-in-oil emulsions [40]. Jiang et al. designed an optical and TIR dual-driven model that integrates sample expansion modules and deep learning methods to enable efficient oil spill identification across multiple scenarios [55]. Jiang et al. also proposed a spatiotemporal RS OSD model that combines optical and TIR response characteristics. This model employs a 3D generative adversarial network (3DCGAN) for sample augmentation and a deep learning module guided by optical and TIR features (SSF-CDBN) to achieve precise detection of oil spills under complex light and mixed-pixel conditions [155].

3.2.2. Oil Spill Thickness Estimation

In oil spill emergency response and environmental assessment, accurately identifying the thickness of oil spills is of great significance. Thick and thin oil spills have different environmental impacts, especially thick oil spills typically contain higher concentrations of toxic chemicals, posing a greater threat to marine life and ecosystems. Hence, effective thickness identification can assist in determining the spread rate, location, and cleanup priority of the spill, thereby improving the accuracy and precision of RS systems in practical applications. Furthermore, thickness information can also aid in estimating the total volume of the spill, providing a basis for cleanup strategies. These factors have collectively accelerated the rapid development of oil spill thickness classification research. The data commonly used for oil spill thickness classification include optical, TIR, and SAR imagery. Optical RS imagery offers abundant spectral information and fine spatial resolution, making it well suited for characterizing variations in oil spill thickness. Existing optical-based oil spill thickness estimation methods can generally be divided into two groups: quantitative inversion and relative thickness classification. Quantitative inversion techniques establish numerical relationships between spectral reflectance and oil film thickness by employing laboratory measurements and physical modeling, enabling the retrieval of absolute thickness values. In contrast, relative classification methods typically follow the Bonn Agreement [156], which categorizes oil films into discrete visual classes such as sheen, rainbow, metallic, transition, and dark.

Kieu et al. conducted laboratory and outdoor pool experiments to acquire hyperspectral images, extracting pixels and augmenting data to create training datasets. Dense artificial neural networks (DANN) and CNN were then trained for oil spill thickness identification [157]. Hilario et al. proposed a physics-based model that analyzes local maxima in the reflection spectra of oil films covering the water surface to estimate oil spill thickness [23]. Qin et al. employed a weighted CatBoost classification model and multi-scale continuous wavelet transform to precisely identify oil films and estimate thickness [158]. Chang et al. proposed a spatial-spectral information joint stacked autoencoder model that utilizes hyperspectral data to extract spectral features of oil films at multiple levels, classifying oil films into five categories. This method demonstrated the advantage of hyperspectral data in oil film thickness classification, particularly in handling complex environments with high resolution and accuracy [25]. Jiang et al. introduced the OG-CNN model, which integrates a self-expansion module with spectral feature extraction techniques, achieving an inversion accuracy of over 98%, particularly excelling in noise robustness [159]. Song et al. used wavelet transform and maximum likelihood classification algorithms to identify thin oil films, thick oil films, and seawater in hyperspectral RS data [160]. Liu et al. proposed a decision tree classification method based on minimum noise fraction (MNF) transformation, which reduces data redundancy and separates image noise [161]. Niu et al. used six spectral indices and an SVM algorithm to identify oil spill thickness from hyperspectral data [162]. Zhu et al. improved traditional stacked autoencoder (SAE) and CNN models to address challenges in combining spectral and spatial features in complex marine environments, significantly enhancing classification accuracy and efficiency [163]. Wang et al. introduced a 1D CNN combined with a GRU network to quantitatively invert marine oil film thickness [24]. Quantitative oil spill thickness inversion methods can accurately estimate the thickness. However, such approaches require extensive experimental data and complex physical modeling, with performance being highly sensitive to environmental variations, which limits applicability in real marine scenarios. In contrast, relative thickness classification approaches categorize oil films into several visual levels for rapid estimation, but reliance on empirical classification criteria makes it difficult to maintain consistent accuracy across different sensors and environmental conditions.

TIR sensors can accurately differentiate oil films of varying thickness by detecting temperature differences between the oil film and the water surface. Jiang et al. proposed a marine oil spill TIR detection SVC model that adaptively selects kernel functions to identify oil spill types and detect oil spill thickness [46]. Li et al. used TIR RS imagery to invert sea surface temperature and estimate oil spill thickness [45]. Wang et al. designed a simulation experiment using TIR imaging to observe the temperature variations of oil spills with different thicknesses over a 24-h period, revealing a positive correlation between oil thickness and temperature during the daytime [47]. TIR RS can distinguish oil films of different thicknesses by detecting temperature differences between the oil and the seawater, offering high sensitivity and real-time capability. However, its performance is easily affected by weather conditions, solar radiation, and sea surface temperature variations, which limit its stability and applicability.

The methods based on SAR data typically analyze variations in the damping ratio of backscattered signals and subsequently construct an inversion model. Garcia-Pineda et al. used SAR data and entropy-damping ratio techniques to propose an oil spill thickness classification method, successfully distinguishing different oil film thicknesses [37]. Meng et al. employed damping ratio and neural networks to invert marine oil spill thickness [39]. Chaudhary et al. extracted polarization information from SAR data and combined it with machine learning methods (SVM and radial basis function) to detect marine oil spill events. By calculating the damping ratio, they also distinguished thick oil layers from thin oil layers [38]. Hammoud et al. combined reflectance and the maximum likelihood estimation algorithm to evaluate oil spill thickness [36]. To improve the accuracy of oil spill thickness detection, several multi-source RS data fusion methods have been proposed. Yang et al. proposed a joint oil spill thickness estimation method based on hyperspectral and TIR RS, employing an SVR model to estimate thickness from spectral reflectance and brightness temperature difference (BTD). They then integrated results using a decision-level fusion algorithm based on fuzzy membership functions [164]. Jie et al. integrated optical image classification results with SAR image damping ratio and introduced a segmented inversion formula, achieving high-precision spatial distribution inversion of oil films with different thickness ranges [165]. Despite remarkable progress, existing oil spill thickness estimation approaches still face challenges such as spectral ambiguity between oil and seawater, limited labeled data, and sensitivity to environmental factors.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations