Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Persistent Scatterer InSAR (PSInSAR) decomposition of Sentinel-1A data (2017–2022), validated with GNSS and precision leveling, revealed vertical and eastward motions across northern Taiwan.

- Results show minor subsidence in the Taipei Basin, uplift in northeastern Taoyuan and Linkou, and eastward motions consistent with Shanchiao Fault activity and regional block rotation.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The main finding confirms that PSInSAR, when integrated with GNSS and leveling, provides reliable, multidirectional deformation fields for tectonic, volcanic, and hydrological monitoring.

- It also offers critical insights for assessing geohazards and infrastructure safety near faults, volcanoes, and nuclear power stations in northern Taiwan.

Abstract

Northern Taiwan is a tectonically and volcanically active region shaped by plate convergence, active faulting, and subsurface hydrological processes. To investigate surface deformation across this complex setting, we applied Persistent Scatterer InSAR (PSInSAR) to Sentinel-1A imagery acquired from 2017 to 2022. Using data from ascending and descending tracks, and removing GNSS-derived northward motion, we decomposed line-of-sight velocities into vertical and eastward components. The resulting deformation fields, validated by dense precision leveling and continuous GNSS observations, reveal consistent but minor (less than 1 cm/year) land subsidence in the Taipei Basin, spatially variable uplift near the Tatun Volcano Group, and a previously vaguely documented uplift zone in northeastern Taoyuan. InSAR-derived eastward motion is consistent with expected kinematics along the southern Shanchiao Fault and supports broader patterns of clockwise tectonic rotation near Keelung. Our InSAR results show the effectiveness of PSInSAR in resolving multidirectional surface motion and exemplifies the value of integrating satellite-based and ground-based geodetic data for fault assessment, hydrologic monitoring, and geohazard evaluation in northern Taiwan.

1. Introduction

Taiwan is situated at the complex and highly active boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the Philippine Sea Plate. To the northeast, the Philippine Sea Plate is subducting in a northwestward direction beneath the Eurasian Plate along the Ryukyu Trench, forming the Ryukyu Arc. In contrast, to the south of Taiwan, the Eurasian Plate is subducting eastward beneath the Philippine Sea Plate along the Manila Trench, giving rise to the Luzon Arc. At the junction of these opposing subduction systems, Taiwan experiences intense plate convergence at a rate of approximately 7–8 cm/year [1], resulting in significant crustal deformation and frequent seismic activity.

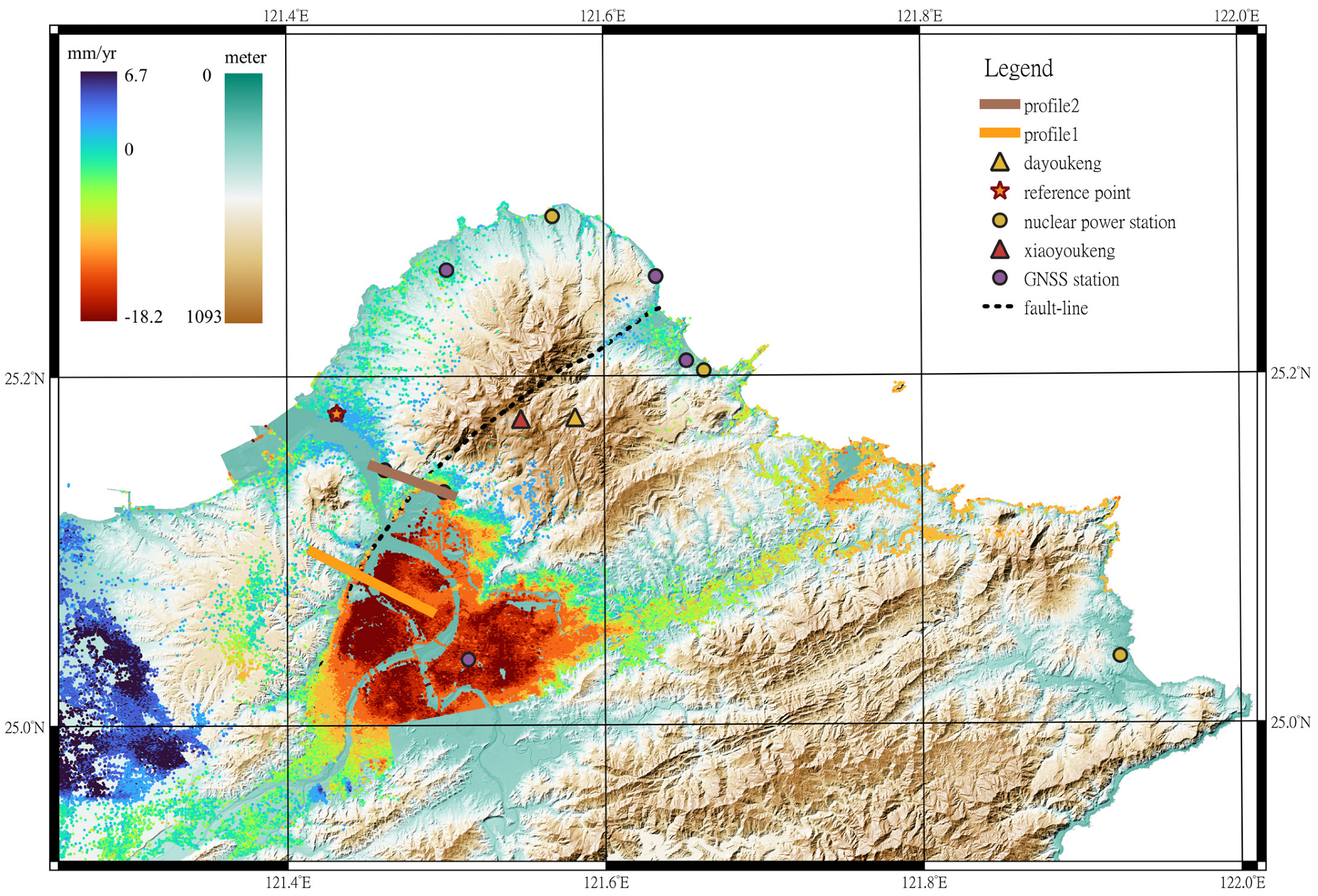

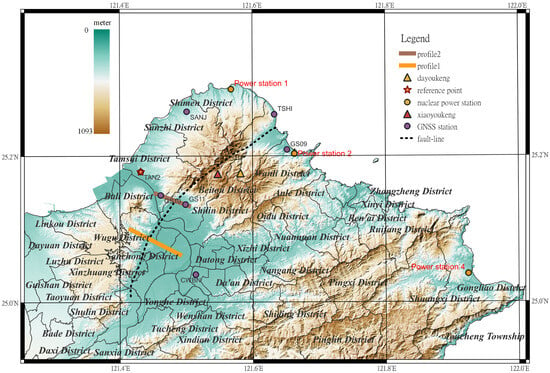

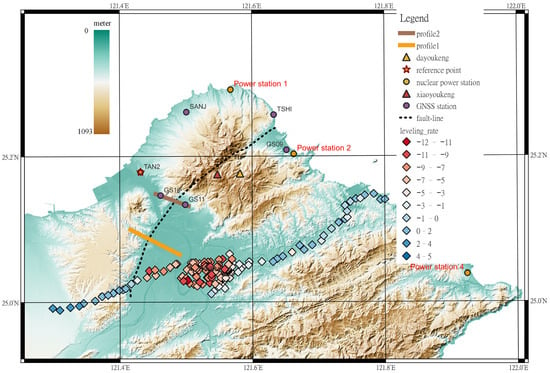

Northern Taiwan is of particular geological interest due to its proximity to critical tectonic and volcanic features, including the Shanchiao Fault, the Tatun Volcano Group (TVG), and the Taipei Basin (Figure 1), which together contribute to the region’s heightened susceptibility to both seismic and volcanic hazards. Two prominent fumaroles—Dayoukeng and Xiaoyoukeng—are located within the TVG and are marked in Figure 1. Around these fumaroles, GNSS stations operated by Academia Sinica have been installed to monitor surface deformation potentially associated with magma activity beneath the TVG.

Figure 1.

Study area in northern Taiwan, including the administrative boundaries of districts and townships. The Shanchiao Fault is marked by a black dashed line, and the PSInSAR profile by a purple line. Key features include two major fumaroles—Dayoukeng and Xiaoyoukeng (orange triangles), GNSS stations (purple circles), nuclear power stations (yellow circles, Stations 1, 2 and 4), and the PSInSAR reference point (red star), located at GNSS station TAN2 in Tamsui District.

In addition to these natural hazards, three of Taiwan’s nuclear power stations—Power Station 1, Power Station 2, and Power Station 4—are situated along the northern and northeastern coasts (Figure 1). The proximity of these facilities to active faults and volcanic features underscores the importance of continuous geophysical monitoring in the region, to support both hazard assessment and infrastructure safety.

Over the past decades, various geodetic techniques have been employed to monitor surface deformation in northern Taiwan. Traditional geometric methods such as precision leveling and Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) have been widely used. While leveling provides high vertical accuracy, it is labor-intensive and challenging for large-scale or long-term monitoring. GNSS enables continuous observations and is relatively easy to install, yet it suffers from reduced accuracy in the vertical component and is limited by terrain and atmospheric conditions in urban or forested areas [2]. Differential Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (DInSAR) has emerged as a powerful technique for mapping ground deformation over wide areas. Among DInSAR approaches, Persistent Scatterer InSAR (PSInSAR) and Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) have proven effective for capturing long-term deformation trends using radar phase information [3,4,5]. Recent studies have also demonstrated the integration of GNSS and InSAR to recover three-dimensional ground motion, including applications in Italy [6], California [7], the Tibetan Plateau [8,9], and Iran [10].

Despite these advances, current satellite-based techniques primarily measure deformation along the line-of-sight (LOS) direction, which represents a combination of vertical and horizontal movements. This limitation is particularly problematic. This limitation is particularly critical in northern Taiwan, where distinguishing between vertical, eastward, and northward motions is crucial for understanding fault mechanics, volcanic processes, and subsidence patterns. Existing methods for decomposing LOS measurements into vertical and horizontal components have been developed and applied in various tectonic settings [11,12,13,14]. However, in northern Taiwan—particularly the Taipei region—such methods have rarely been accompanied by detailed validation using independent ground-based data or thorough geological interpretations. This limits their effectiveness in capturing the full complexity of deformation patterns in tectonically and hydrologically active areas.

Although previous studies have applied InSAR in northern Taiwan, few have decomposed LOS velocities into vertical and eastward components while validating the results against wide-area ground-based data from GNSS and precision leveling across regions from Taoyuan to Keelung. A unique aspect of this study is the use of a dense and extensive precision leveling dataset to validate InSAR-derived vertical velocities. We apply a GNSS-corrected (in the northward direction) decomposition method to two-track Sentinel-1A data, which are then validated using measurements from seven continuous GNSS stations and 141 leveling benchmarks. The resulting deformation maps reveal localized uplift in northeastern Taoyuan, subsidence and horizontal motion in the Taipei Basin, and eastward motion consistent with fault-parallel extension and regional rotation near Keelung. These deformation results provide a foundation for more advanced studies on fault activity, land subsidence, and tectonic signatures in northern Taiwan.

2. Method for Decomposing Line-of-Sight Velocities into Eastward and Vertical Velocity Components

Surface deformation detected by Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) is expressed in the LOS direction, which combines contributions from vertical and horizontal motions. To derive interpretable vertical and eastward velocities, we applied a two-dimensional decomposition method using SAR data from both ascending and descending tracks. For each SAR pixel, the LOS deformation velocity VLOS can be related to the deformation components as:

where θ and α are the mean incidence and azimuth angles of the satellite, respectively. VE, VN, and VU are the eastward, northward, and vertical deformation velocities. Equation (1) was also derived by C. Hwang in Appendix B of the paper by Hung et al. [15], using a concept widely applied in satellite geodesy. Recent papers on the decomposition issues are, e.g., Brouwer and Hassen [13] and Brouwer and Hassen [14].

Sentinel-1A is a polar-orbiting satellite with a right-looking sensor, making its radar measurements insensitive to northward displacements. Therefore, we estimate the northward velocity using continuous GNSS data and compute its contribution to the LOS deformation, which is then removed. The LOS contribution from northward motion modeled as:

where λ and ϕ are the longitude and latitude of a GNSS station, respectively. The coefficients a, b, and c are determined using least-squares estimation. The LOS velocities from the ascending and descending tracks are then corrected as follows:

where are the corrected LOS velocities after removing the northward contribution. The subscript i denotes interpolation from the planar model in Equation (2), and subscripts a and d refer to ascending and descending tracks, respectively.

With the northward motion removed, we are left with two observations ( and ) for two unknowns (VE and VU):

Solving the system yields:

To ensure reliable decomposition, we applied an additional screening procedure to identify suitable persistent scatterer (PS) points. First, we computed the residual LOS velocities by removing the northward and eastward components derived from GNSS. These residuals, denoted and , are projected onto the vertical direction as:

where and are the estimated vertical velocities from ascending and descending tracks, respectively. A PS point is retained for decomposition only if the difference between these two vertical estimates is less than 10 mm/yr. That is:

This 10 mm/yr threshold approximates the upper bound of long-term vertical-rate uncertainty when integrating PSInSAR with GNSS and leveling in northern Taiwan. To test its robustness, we repeated the decomposition using thresholds of 5, 10, 15, and 20 mm/yr (Table 1). The deformation patterns remained consistent across all cases (e.g., Taipei Basin subsidence and Taoyuan uplift), but PS density and noise levels varied. At the threshold of 5 mm/yr, PS density dropped by ~30% (50,550 points) relative to the 10 mm/yr case (66,510 points), while higher thresholds (15–20 mm/yr) only marginally increased PS density (68,128–68,164 points) but introduced more noise (eastward std up to ~1.9 mm/yr, vertical std ~3.8 mm/yr). Thus, the adopted 10 mm/yr threshold provides a practical balance between coverage and reliability.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of PS density and velocity noise levels to different vertical consistency thresholds.

3. Data

3.1. Sentinel-1A SAR Images and Processing

Sentinel-1A is part of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Copernicus Programme for environmental monitoring and security. Launched on 3 April 2014, the satellite operates in a sun-synchronous orbit and carries a C-band synthetic aperture radar (SAR) instrument. Key parameters of the Sentinel-1A mission are summarized in Table 2. In this study, Single Look Complex (SLC) products were acquired from the Alaska Satellite Facility (ASF) data portal.

Table 2.

Parameters of the Sentinel-1A mission.

To detect surface deformation in northern Taiwan, we used SAR images from both ascending and descending tracks covering the period from 2017 to 2022 (Table 3). Specifically, the ascending track data span from 28 March 2017 to 1 January 2022, while the descending track data span from 11 April 2017 to 3 January 2022. All images were captured in VV polarization. The mean incidence angles for the ascending and descending tracks are 42.597° and 36.204°, respectively. These values were used to calculate the projection coefficients necessary for two-dimensional decomposition of LOS velocities.

Table 3.

Summary of Sentinel-1 SAR imagery used in this study.

3.2. Global Navigation Satellite Systems Dataset

The GNSS dataset used in this study serves three primary purposes:

- (1)

- to model the northward contribution to LOS deformation,

- (2)

- to validate the PSInSAR and decomposed velocity results, and

- (3)

- to assist in the screening of persistent scatterer (PS) points by providing independent eastward and northward velocities for removing horizontal motion components from LOS measurements; see Equations (7)–(9).

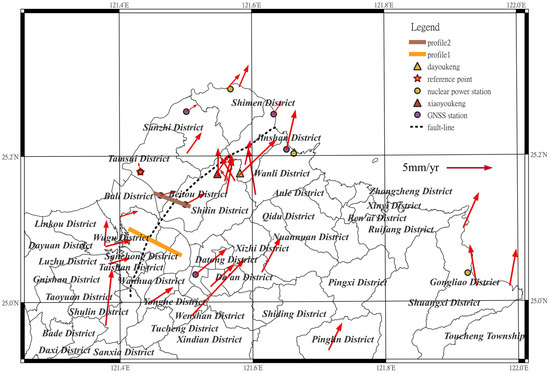

We obtained GNSS displacement data from the Taiwan Geodetic Model (TGM), established by the Institute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica (https://tgm.earth.sinica.edu.tw/, accessed on 13 October 2025). Figure 2 shows the relative velocities at all stations available at TGM, referenced to a stable site located in Penghu (station S01R).

Figure 2.

GNSS-derived horizontal velocities from 2017 to 2022, shown relative to the reference station S01R at Penghu (23.6553°N, 119.5924°E). Each arrow represents the direction and magnitude of horizontal displacement at a GNSS station. The Shanchiao Fault is shown as a black dashed line, and district boundaries are indicated by gray lines. The reference arrow in the upper right corresponds to 5 mm/yr.

Seven GNSS stations from TGM were selected for validation purposes (see Section 4.4) based on two criteria: (1) the station is surrounded by PS points and (2) it has data covering the same observation period as the Sentinel-1A imagery. The selected GNSS stations and their locations are shown in Figure 1 Due to the inherent limitations of SAR in areas with dense vegetation—especially in mountainous regions like the TVG—the density of PS points is low, making reliable InSAR analysis difficult. Consequently, GNSS stations located in the TVG and similar mountain regions were excluded from the validation analysis to ensure robust cross-comparison (see Section 4.4).

Among the selected GNSS stations, TAN2 was also selected as the reference point for PSInSAR phase unwrapping due to its stability. In the ITRF2014 reference frame, TAN2 exhibits a relatively small vertical deformation rate of approximately 4.5 mm/yr, and stable and consistent displacement time series. Accordingly, its relative velocities were set to zero during PSInSAR phase unwrapping and velocity calculation, consistent with its role as the reference station.

3.3. Precision Leveling Data

The precision leveling data (Figure 3) used in this study for the Taipei region were obtained from a project funded by the Water Resources Agency of Taiwan [16]. The dataset comprises repeated elevation measurements on benchmarks located in urban and suburban areas, covering the period from 2001 to 2023. An earlier paper on 30 years of precision leveling by Chen et al. [17] was not used in this study because those data do not reflect the current status of vertical land deformation in northern Taiwan.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of leveling benchmarks and other key features in the Taipei and Taoyuan regions (same as those in Figure 1). Benchmarks are color-coded by vertical velocity over 2017–2022 (mm/yr; see the rates below the legend “leveling benchmark”), revealing both subsidence and uplift patterns. Notably, several benchmarks in northeastern Taoyuan exhibit positive rates, indicating marked uplift. The vertical scale bar shows the elevations.

Each benchmark in the WRA [16] leveling dataset is referenced by a unique ID (e.g., LJ010, LJ8906), along with its TWD97 (Taiwan Datum 1997) northing and easting coordinates, which were converted to geodetic latitudes and longitudes in this study. The elevation measurements were collected annually. This allows for the estimation of mean vertical velocity over a given time span, provided that more than two measurements are available. In some locations, the data coverage extends over two decades, enabling analyses of long-term trends and elevation anomalies. However, a few benchmarks lack elevation records in specific years.

To ensure consistency with InSAR observations, only elevation measurements from 2017 to 2022 were used to compute leveling-derived vertical rates. This overlapping time span enables meaningful comparison and validation of the InSAR-derived vertical deformation rates. The total number of selected benchmarks is 141.

In addition to widespread subsidence across the Taipei Basin, the leveling data reveal localized zones of uplift occurring exclusively in the Taoyuan area (Figure 1). Several benchmarks in northeastern Taoyuan exhibit positive vertical rates exceeding 2 mm/yr, contrasting sharply with the subsidence observed in Taipei. These uplift signals, though spatially limited, may reflect localized tectonic or hydrological processes and warrant further analysis in conjunction with InSAR and GNSS observations (see Section 5).

4. Result: Vertical and Eastward Velocities from InSAR and Assessments

4.1. InSAR Data Preprocessing

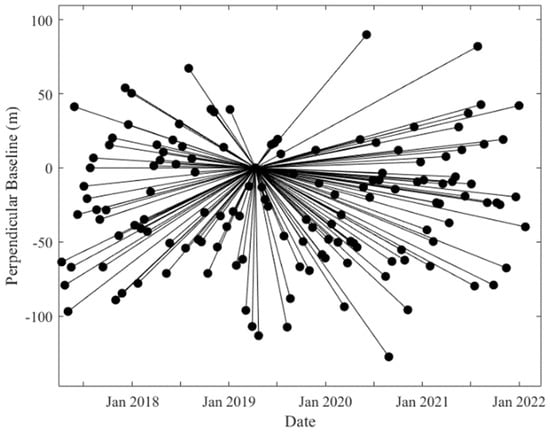

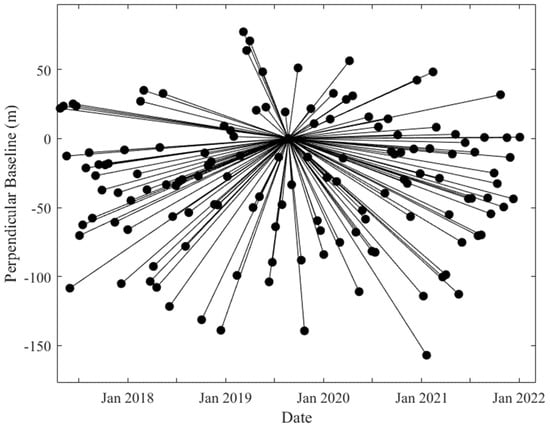

For this study, Sentinel-1A SAR images from both ascending and descending tracks acquired between 2017 and 2022 were processed. Using the 2022 version of Sentinel Application Platform (SNAP, available at https://step.esa.int/main/toolboxes/snap/ (accessed on 8 May 2025)), we selected master images with the lowest temporal and perpendicular baselines to ensure high coherence. As a result, the chosen master image for the ascending track was acquired on 11 April 2019, and for the descending track on 23 August 2019. In total, 139 slave images were used for the ascending dataset and 137 for the descending dataset.

Image coregistration and interferogram generation were performed with the InSAR Scientific Computing Environment (ISCE) [18], incorporating a digital elevation model (DEM) and precise orbit data. To minimize misregistration, the Enhanced Spectral Diversity (ESD) method was applied. The resulting interferograms captured phase differences between each slave image and the master.

To detect long-term surface deformation, we applied the Stanford Method for Persistent Scatterers (StaMPS) [5], which uses amplitude, phase, and statistical analyses to identify PS points (pixels) and unwrap phase signals. Tropospheric corrections were carried out using the Toolbox for Reducing Atmospheric InSAR Noise (TRAIN) [19], which estimates atmospheric delays based on pressure, temperature, and relative humidity data from the ERA5 archive, sampled on a 30 km global grid.

The PSInSAR-derived LOS velocities were validated using GNSS and leveling data (see Section 3.2 and Section 3.3). These velocities were then decomposed into vertical and eastward components following the method described in Section 2. Several interferograms from the ascending track—specifically those acquired on 2 July 2017; 31 August 2017; 10 May 2018; 27 June 2018; and 9 July 2018—showed unwrapping errors and were excluded from the velocity analysis.

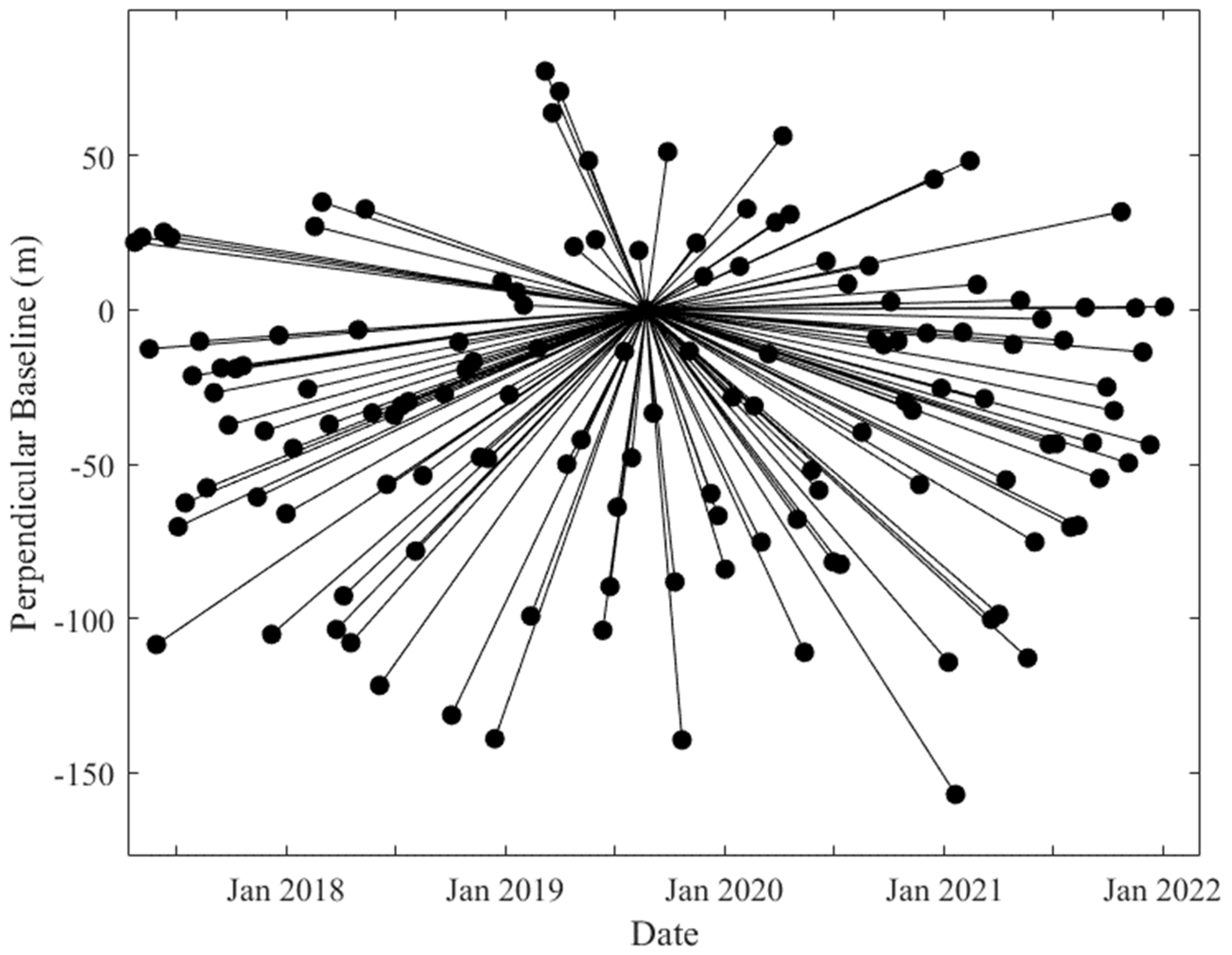

Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the spatial–temporal baselines of the SAR image pairs for the ascending and descending tracks. In both datasets, perpendicular baselines were constrained within ±150 m. Negative perpendicular baselines indicate acquisition positions located south of the master image.

Figure 4.

The spatial-temporal baselines of the image pairs from the ascending track. Spatial–temporal baselines of Sentinel-1A image pairs from the ascending track, showing perpendicular baselines (in m) relative to the master image acquired on 11 April 2019. Each dot represents an acquisition, and lines connect each slave image to the master.

Figure 5.

Spatial-temporal baselines of Sentinel-1A image pairs from the descending track, showing perpendicular baselines (in m) relative to the master image acquired on 23 August 2019. Each dot represents an acquisition, and lines connect each slave image to the master.

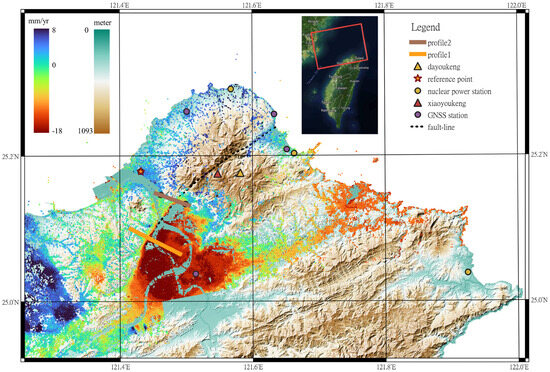

4.2. InSAR-Derived LOS Velocities

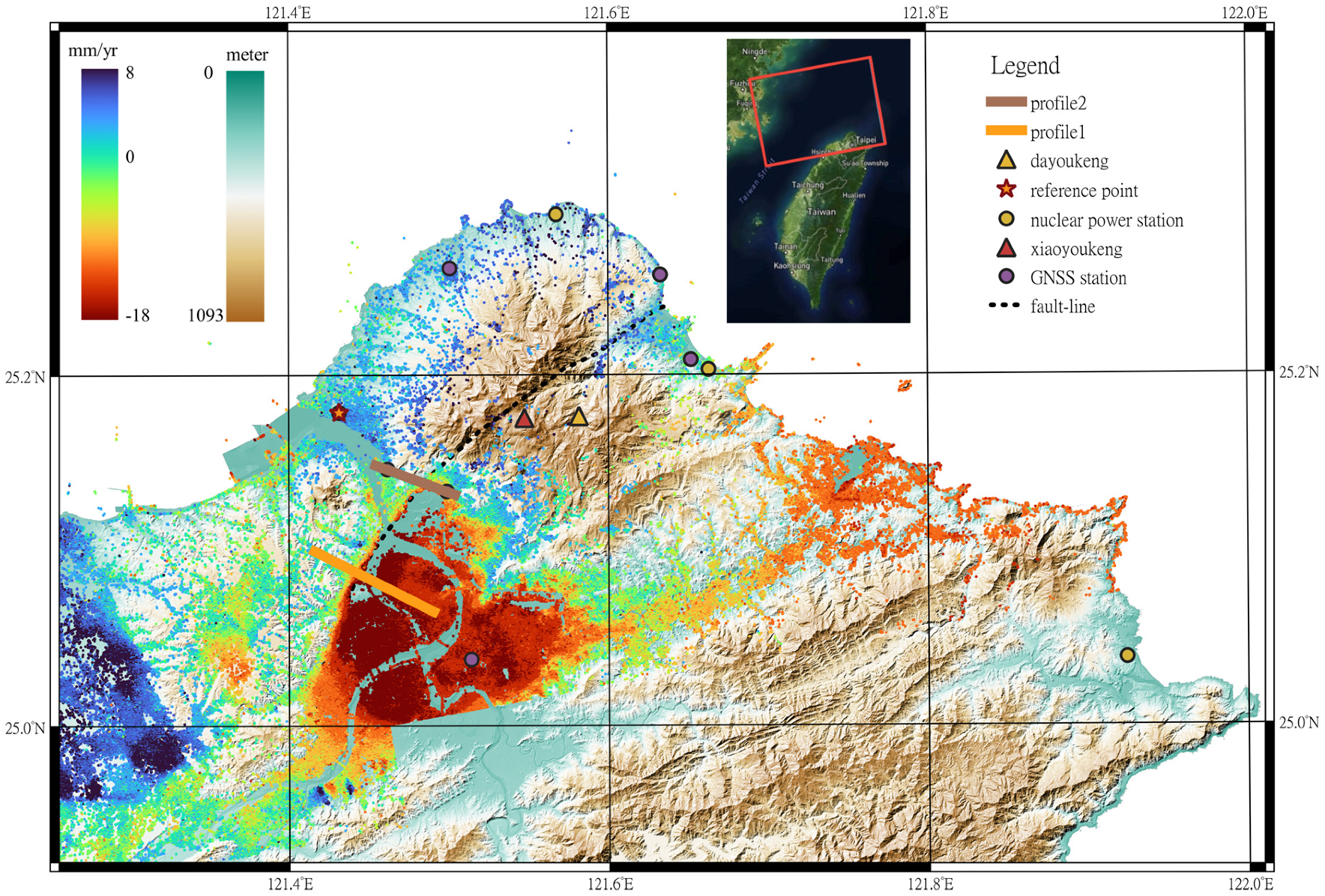

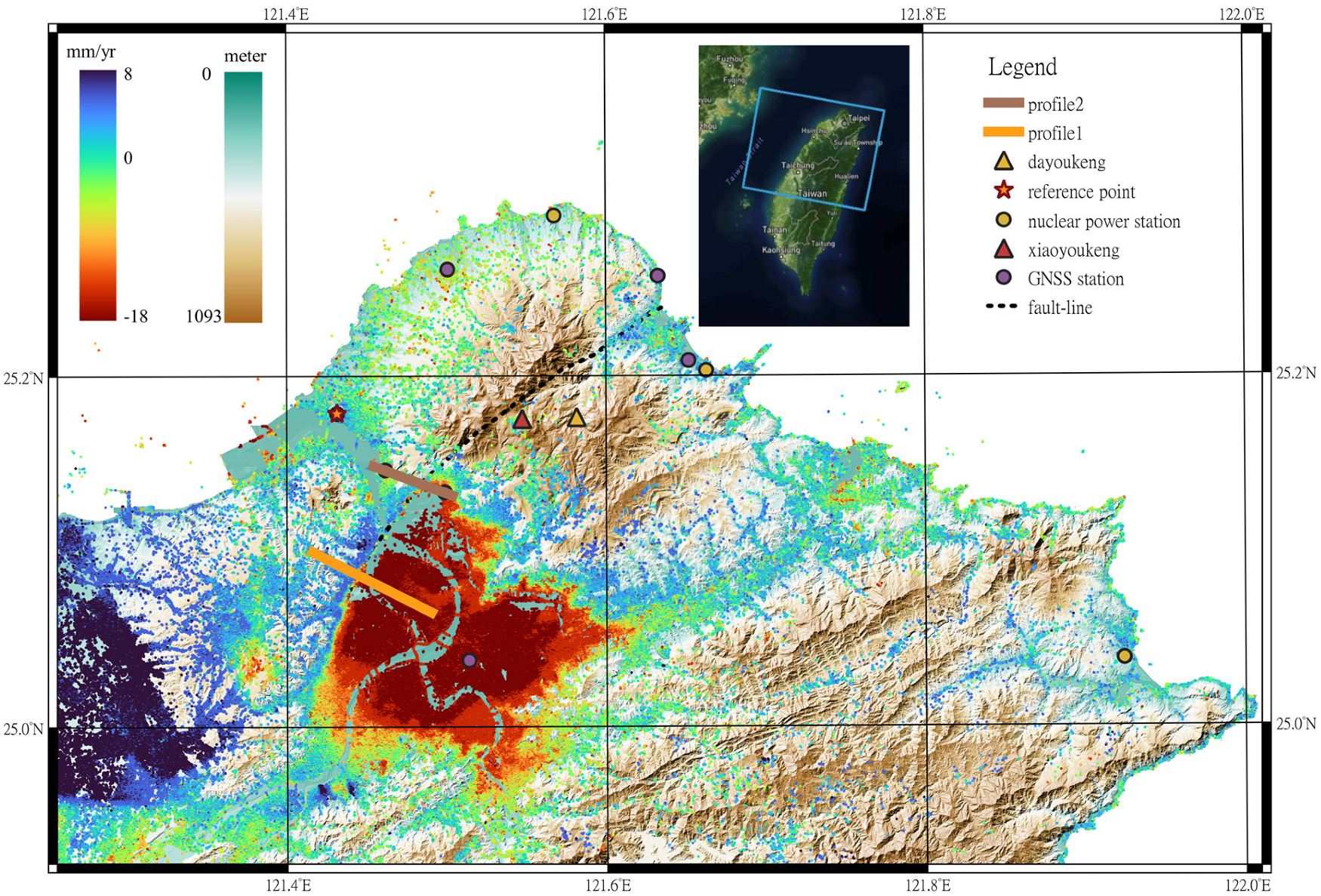

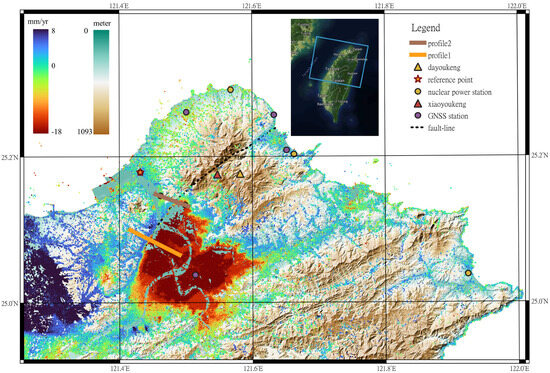

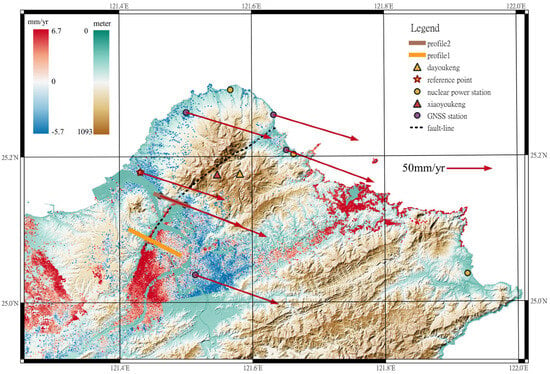

Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the InSAR-derived deformation velocities in the LOS direction, derived from ascending and descending Sentinel-1A datasets, respectively. These velocity fields have been corrected for topographic contributions and tropospheric delays and are referenced to the GNSS station TAN2 (Figure 1, red star). In this convention, positive values represent motion toward the satellite, while negative values indicate motion away from it.

Figure 6.

LOS deformation velocities from the ascending track. The red star marks the reference point for phase unwrapping near GNSS station TAN2. The mean local incidence angle of the ascending dataset is 42.6°. The red box in the inset map shows the path and frame of the ascending track.

Figure 7.

LOS deformation velocities from the descending track, with the same reference point and directional arrows as in Figure 6. The mean local incidence angle of the ascending dataset is 36.2°. The blue box in the inset map shows the path and frame of the descending track.

Both datasets reveal coherent and spatially continuous deformation patterns across northern Taiwan. A prominent contrast in LOS velocities is observed across the Shanchiao Fault system, particularly near the intersection of its northern and southern segments. The Taipei Basin exhibits the largest LOS deformation rates in the study area, dominated by negative velocities in the ascending track and corresponding positive signals in the descending track; these patterns that are characteristic of subsidence. In contrast, adjacent regions such as the Linkou Plateau and the TVG, including Shilin and Jinshan, show relatively low-magnitude LOS velocities, indicating either surface stability or slower rates of vertical or horizontal motion.

A marked difference in LOS velocities between the hanging wall (east of the Shanchiao Fault) and the footwall (west of the fault) suggests that the deformation is not solely driven by hydrological factors, but also reflects fault-controlled subsidence and differential motion across the basin margin. While both tracks display similar deformation patterns, the opposite radar viewing angles lead to expected differences in signs, particularly in areas such as Keelung City, where the same displacement vector projects differently onto the LOS vector. These LOS velocity fields provide the basis for the two-dimensional decomposition presented in Section 4.3, where they are used to extract vertical and eastward components of surface motion.

4.3. Decomposing the Two-Track InSAR LOS Velocities into Vertical and Eastward Velocity Components

We performed the two-dimensional decomposition described in Section 2 to separate the InSAR-derived line-of-sight (LOS) velocities into vertical and eastward components. Prior to decomposition, LOS contributions from northward motions were estimated using GNSS data and removed. In northern Taiwan, the LOS contribution from northward motion ranges from approximately 0.14 to 0.78 mm/yr for the ascending track and from 0.13 to 0.72 mm/yr for the descending track of Sentinel-1A. These contributions are small and spatially smooth in northern Taiwan and are therefore not shown in this paper. To further improve the reliability of the decomposed velocities, we also applied an additional PS selection criterion based on the consistency between ascending and descending vertical projections, as defined in Equation (9).

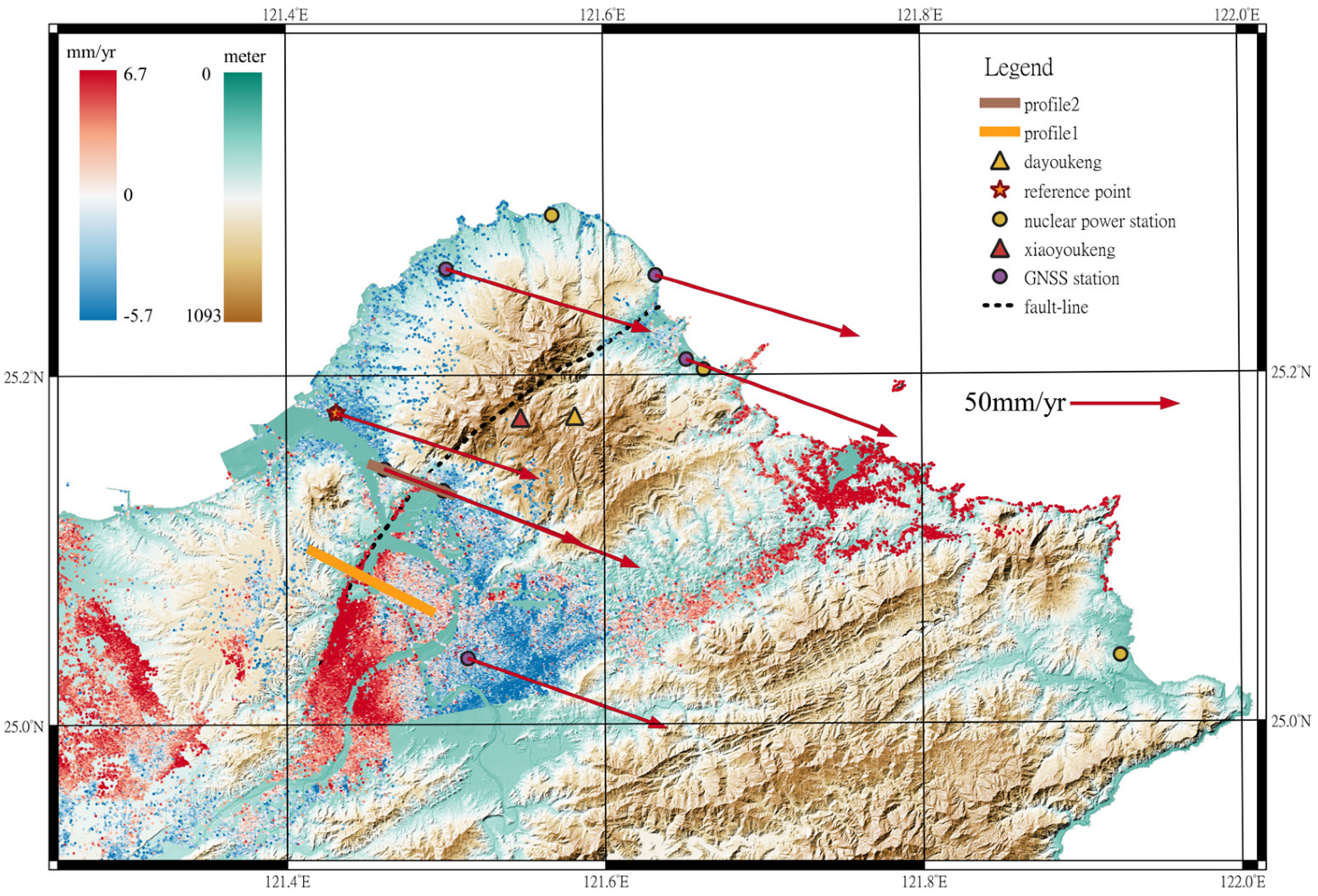

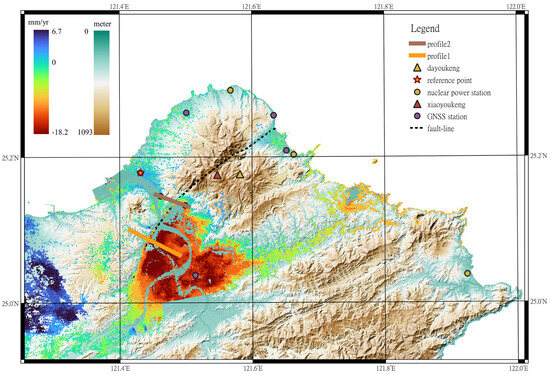

Due to geometric and coherence limitations of SAR data in vegetated and mountainous terrain—particularly in regions such as the Tatun Volcano Group (TVG) and rural areas of Taipei, New Taipei, and Taoyuan—the number of valid PS points used in the decomposition was lower than in the original LOS velocity datasets. Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the final eastward and vertical velocity maps, both referenced to GNSS station TAN2. These maps highlight deformation signals primarily in urbanized regions such as the Taipei Basin and townships in northern Taiwan, where PS density remains high and the decomposition is more reliable.

Figure 8.

Eastward velocities derived from the two-track decomposition (color background), shown relative to the reference GNSS station TAN2 (red star). Positive values (red) indicate eastward motion, and negative values (blue) indicate westward motion. Overlaid arrows represent GNSS-derived horizontal velocities (2017–2022, absolute velocities in ITRF), with arrow length proportional to the velocity magnitude and a reference arrow of 50 mm/yr shown for scale. Major landmarks, GNSS stations, fault lines, and key volcanic features such as Dayoukeng and Xiaoyoukeng are also marked for reference (see also Figure 1). The vertical color scale on the left is for the InSAR-derived eastward velocities, and the vertical color scale on the right is for elevations (same as that for Figure 1).

The decomposed velocity fields reveal regional-scale patterns, including eastward motion and subsidence in the Taipei Basin, slight uplift near the western, southern, and northern flanks of the TVG, and spatial variability across the Shanchiao Fault system. Slight subsidence occurs in the city of Keelung, around Keelung Harbor, and along the corridor from Taipei to Keelung. However, interpreting these results requires careful consideration of the geological context and local conditions. More detailed analyses and interpretations of the vertical and eastward velocities—based on the decomposed results shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9—are presented in Section 5.

4.4. Validation of InSAR-Derived Eastward Velocities by GNSS Data

To assess the reliability of the eastward velocities derived from PSInSAR (Figure 8), we performed a validation using GNSS measurements (see Section 3.2). GNSS remains the only ground-based geodetic technique capable of directly capturing horizontal displacements, including those in the east–west direction. With its high temporal resolution and accurate three-dimensional positioning, GNSS is well-suited for evaluating horizontal velocities derived from InSAR, particularly in contexts involving tectonic deformation, fault creep, or anthropogenic surface movements.

Table 4 summarizes the comparison of eastward velocities obtained from PSInSAR and GNSS at 6 stations, where the GPS time series are stable without interruptions by events such as earthquakes and antenna changes. All values are referenced to GNSS station TAN2 to ensure a consistent local reference frame and eliminate potential systematic biases. All station names in Table 4 are defined by TGM (Section 3.2). Overall, the results demonstrate good agreement between the two datasets. At most stations, the differences are within approximately ±1.3 mm/yr, which supports the validity of the PSInSAR-derived eastward velocities.

Table 4.

Comparison of PSInSAR-derived and GNSS-derived eastward velocities at 6 stations (velocities relative to station TAN2; units in mm/yr).

Nonetheless, some discrepancies are noteworthy. For instance, station GS10 shows a difference of 2.57 mm/yr, while GS09 differs by −1.21 mm/yr. These larger deviations may result from several factors, including localized atmospheric artifacts, geometric differences between the InSAR and GNSS observation techniques, or reduced coherence in the InSAR time series at those locations. SANJ and TSHI exhibit relatively small differences (−0.22 mm/yr and −0.38 mm/yr, respectively), suggesting strong consistency between the two methods at those sites.

In conclusion, the comparison presented in Table 4 confirms that PSInSAR provides reliable estimates of eastward velocities in most locations, with generally minor deviations from GNSS-derived values. The results reinforce the applicability of two-track InSAR decomposition for resolving horizontal motion, although site-specific anomalies may require further investigation to improve local accuracy.

4.5. Validation of the InSAR-Derived Vertical Velocities by Leveling Data

To assess the accuracy of the PSInSAR-derived vertical velocities, we compared them against leveling-derived rates, which offer the most precise measurements of vertical ground motion. While GNSS provides three-dimensional positioning, its vertical accuracy is generally lower due to satellite geometry and atmospheric effects. In contrast, precision leveling achieves sub-millimeter precision over short to moderate distances, making it particularly valuable for validating vertical displacements, especially in regions experiencing subtle uplift or subsidence.

Although TAN2 is used as the phase reference point in the InSAR processing, it does not affect our comparison with leveling data because we compare rates of vertical motion, not absolute elevations. The leveling and InSAR velocities are both relative, so their reference points do not need to coincide.

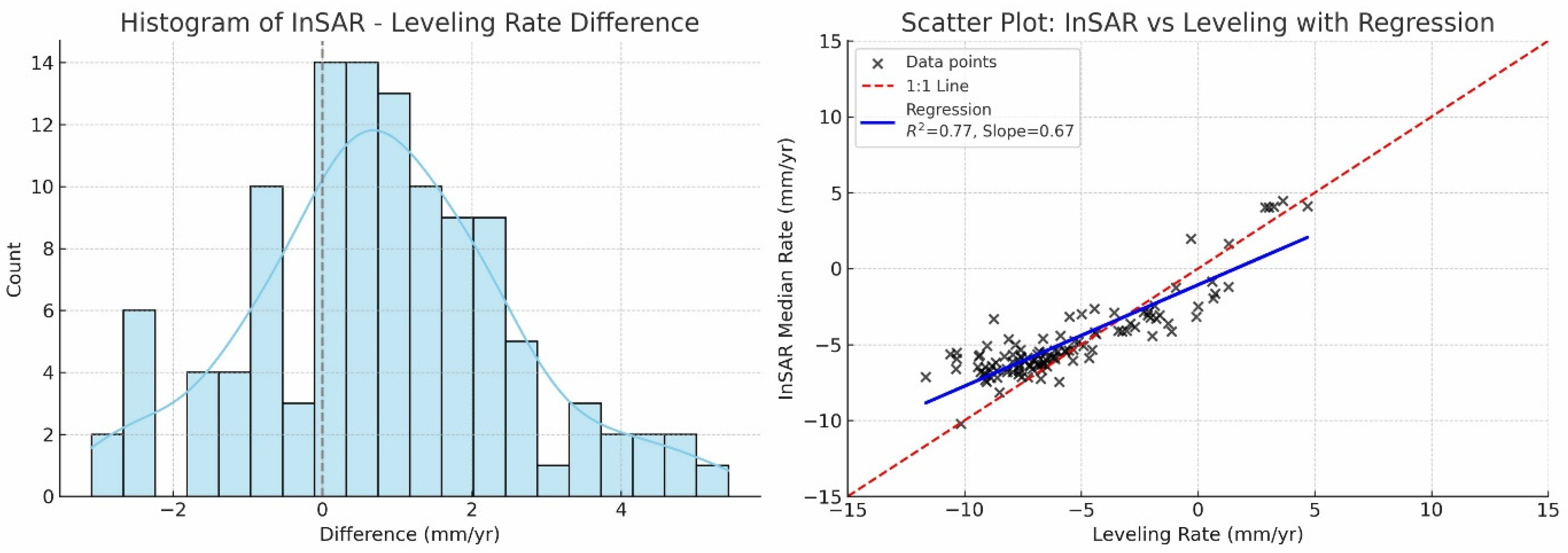

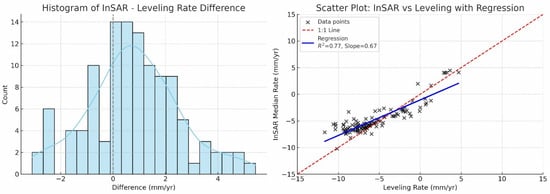

Given the large number of comparison points (141 benchmarks, Figure 3), we present the results in graphical form rather than a table. Figure 10 illustrates the comparison between InSAR-derived and leveling-derived vertical velocities. The left panel shows a histogram of the differences (InSAR minus Leveling). The distribution is centered slightly to the right of zero and shows a positive skew, indicating that InSAR generally yields more positive vertical rates than leveling. This implies that InSAR tends to underestimate subsidence or overestimate uplift relative to leveling benchmarks. The differences range from −3.09 mm/yr to 5.43 mm/yr, with a mean difference of 0.79 mm/yr and a root mean squared difference of 1.27 mm/yr, suggesting a mild but systematic bias.

Figure 10.

(Left) Histogram of the differences between InSAR-derived and leveling-derived vertical velocities. The vertical dashed line shows the zero difference. The differences follow a normal-distribution curve, centered slightly above zero, indicating a mild positive bias. (Right) Scatter plot comparing InSAR and leveling vertical velocities, with the 1:1 reference line (dashed red) and a linear regression line (solid blue).

The right panel of Figure 10 presents a scatter plot comparing the InSAR median vertical velocities with their leveling-derived counterparts. Most points fall above the 1:1 line (dashed red), consistent with the histogram’s implication that InSAR measurements tend to overestimate vertical displacement. Nonetheless, the points cluster around a regression line (solid blue), with a regression coefficient (R2) of 0.77 and a slope of 0.67. These values indicate a strong linear relationship between the two datasets, despite the slight bias. This confirms that InSAR successfully captures the spatial variability and relative patterns of vertical deformation across the region.

In summary, while PSInSAR tends to slightly overestimate vertical rates compared to leveling data, it still provides a reliable representation of regional vertical deformation patterns. The consistency in spatial trends, supported by strong correlation metrics, highlights the capability of two-track InSAR decomposition for detecting vertical ground motion. Together with the horizontal velocity validation in Section 4.4, these results confirm the robustness of PSInSAR as a tool for long-term geodetic monitoring of vertical and eastward motions in northern Taiwan.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Patterns from the InSAR Results

The decomposed PSInSAR velocity fields reveal spatially coherent and geophysically meaningful surface deformation across northern Taiwan, shaped by the interplay of regional tectonics, active faulting, groundwater processes, and volcanic activity. Figure 8 illustrates widespread eastward motion in the Taipei Basin and adjacent areas, while Figure 9 highlights vertical displacements ranging from strong subsidence to localized uplift.

In the vertical velocity field, the Taipei Basin stands out with significant subsidence reaching −18 mm/yr in some locations. These patterns are consistent with previous leveling-based studies [2,17,20] and are independently validated by precision leveling data from 141 benchmarks collected between 2018 and 2022 (Figure 3). However, PSInSAR provides a much denser spatial perspective, revealing continuous deformation across both monitored and previously unmonitored areas. Unlike leveling, which is constrained to fixed routes, PSInSAR captures large-scale trends as well as fine-scale heterogeneity across the basin and its flanks.

The eastward velocity field reveals localized horizontal displacements exceeding +6 mm/yr from Xinzhuang and Wugu toward Keelung, reflecting crustal extension and clockwise block rotation associated with the oblique convergence between the Philippine Sea and Eurasian Plates [21]. Variability near fault zones indicates distributed strain rather than localized fault slip. Notably, the southern Shanchiao Fault segment shows clear kinematic contrasts between the hanging wall and footwall (see Section 5.3), underscoring its role in accommodating deformation through broad, rather than discrete, fault behavior.

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show that the coastal areas near nuclear power Stations 1 and 2 exhibit no notable interruptions or spatial gradients in either vertical or eastward velocities, in contrast to the sharp changes observed near the southern segment of the Shanchiao Fault. Near nuclear power Station 4, no valid PSInSAR result is available due to insufficient persistent scatterers or failure to meet the vertical consistency condition (Equation (9)). Similarly, no decomposed InSAR velocities are available at the fumaroles of Dayoukeng and Xiaoyoukeng, likely due to dense vegetation, rugged terrain, and the inability to meet the screening criteria for reliable decomposition. Future improvements in PS selection or decomposition methods may enable valid estimates at these geologically critical sites.

Compared to GNSS, which offers high-accuracy point measurements, PSInSAR enables continuous, basin-wide mapping of both vertical and horizontal displacements at high spatial resolution. A combination of PSInSAR, GNSS, and leveling thus provides a powerful framework for identifying deformation sources and validating spatial patterns. This GNSS-aided decomposition is consistent with approaches used in other tectonically active regions such as Tibet [8,9] and Iran [10]. The following three sections present targeted analyses derived from the PSInSAR results, focusing on land subsidence in the Taipei Basin, fault-related deformation across the Shanchiao Fault, and uplift patterns in northeastern Taoyuan and Linkou.

5.2. Land Subsidence in the Taipei Basin

The Taipei Basin exhibits the most pronounced vertical deformation in our study area, with Persistent Scatterer InSAR (PSInSAR) detecting subsidence rates up to −18 mm/yr. These high rates are concentrated in central and southwestern districts such as Wugu, Sanchong, Xinzhuang, and Banqiao (Figure 1)—areas known for historical groundwater extraction and compressible alluvial deposits. The spatial pattern of PSInSAR-derived subsidence closely matches results from the 141 precision leveling benchmarks monitored by WRA (Figure 3), many of which report annual vertical displacements exceeding −15 mm/yr [16].

PSInSAR significantly enhances conventional geodetic monitoring by offering high-density, spatially continuous observations over the entire basin. While leveling networks are invaluable for high-accuracy validation along fixed lines, they lack spatial resolution and cannot capture localized anomalies or heterogeneous behaviors between benchmarks. In contrast, PSInSAR clearly delineates regions of uplift around the basin margins and detects small-scale westward motion toward the subsidence center, implying horizontal stress redistribution and centripetal compaction within a bowl-shaped basin geometry.

Our results primarily represent long-term average subsidence patterns during 2017–2022. In this post-subsidence phase, groundwater levels have shown signs of stabilization or recovery due to sustained regulation and reduced pumping. Although we do not directly analyze groundwater level time series or elastic aquifer behavior, our vertical velocity patterns are broadly consistent with those reported by Lin et al. [22], who identified transient and recoverable surface displacements in the basin related to groundwater recharge. Our findings are complementary, offering spatially extensive measurements that validate and contextualize previous localized observations. Moreover, our PSInSAR displacement time series could enable future investigations into elastic aquifer responses and groundwater-storage dynamics, similar to the approaches demonstrated by Lin et al. [22].

5.3. Deformation Across the Shanchiao Fault

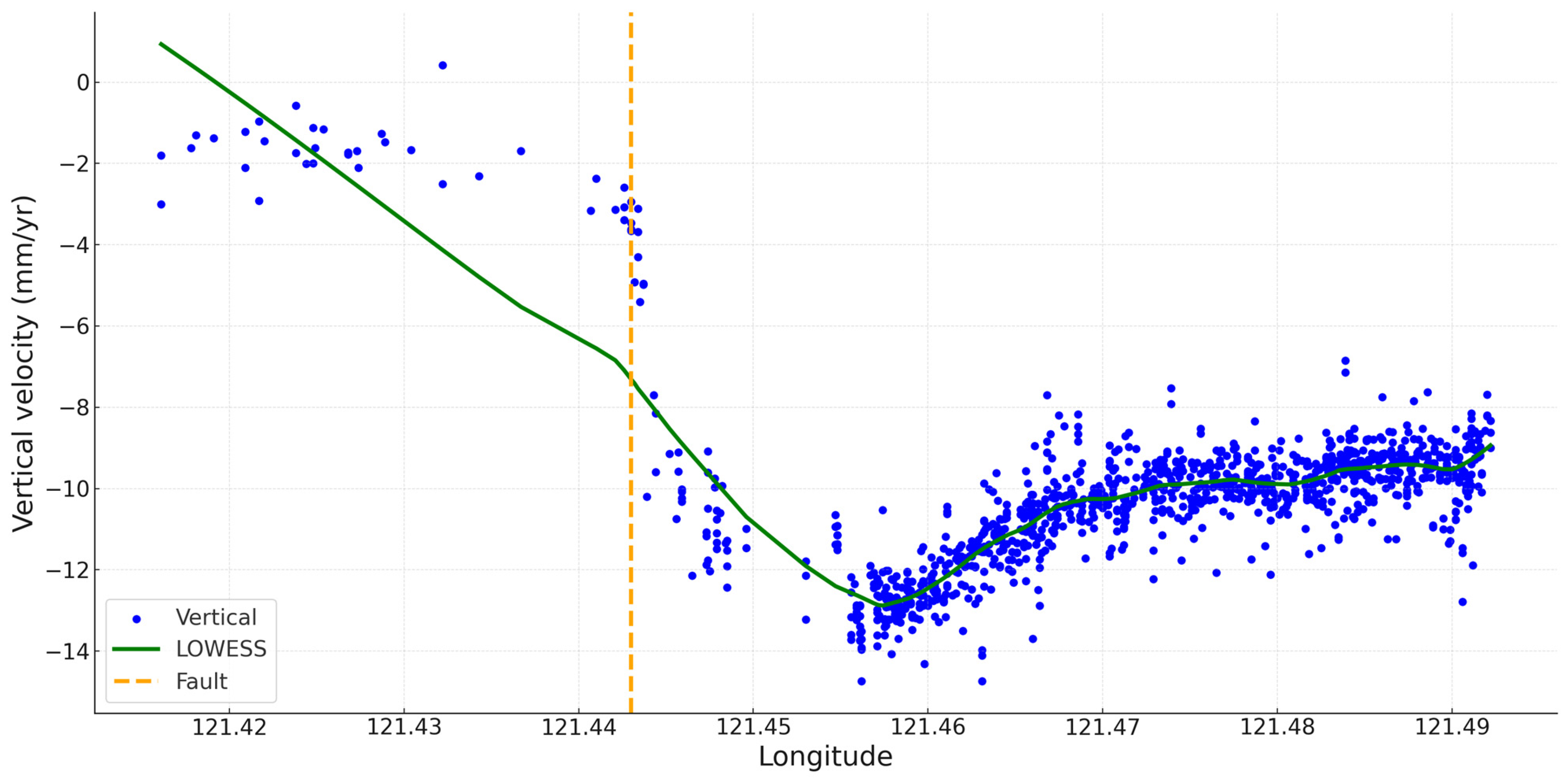

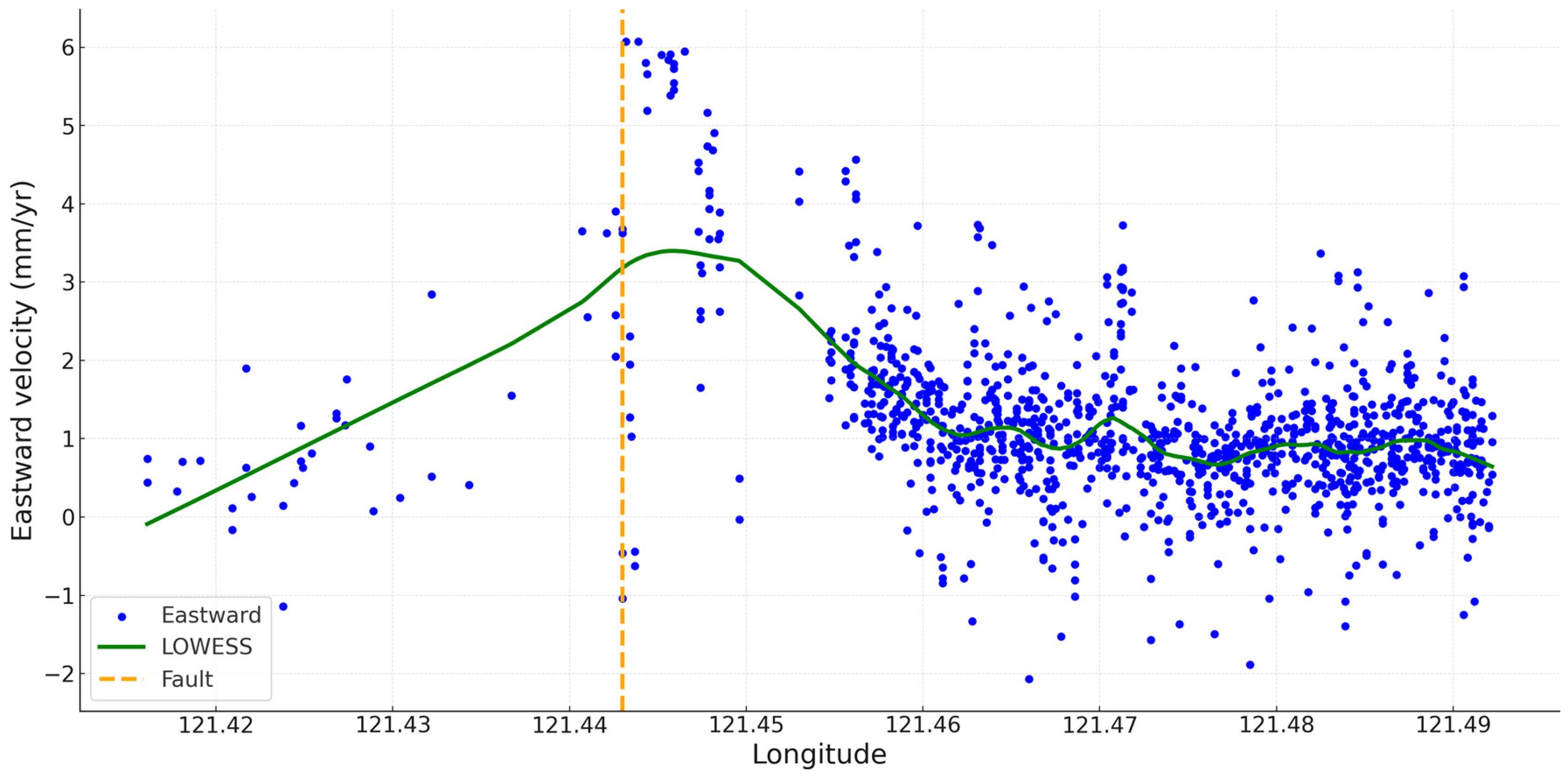

The Shanchiao Fault is a major north–south trending normal fault marking the western boundary of the Taipei Basin. It plays a crucial role in accommodating crustal extension and shaping surface deformation in northern Taiwan. Our PSInSAR-derived velocity fields clearly reveal spatially coherent deformation patterns across the fault, particularly along its southern segment, where the density of persistent scatterers enables high-resolution analysis.

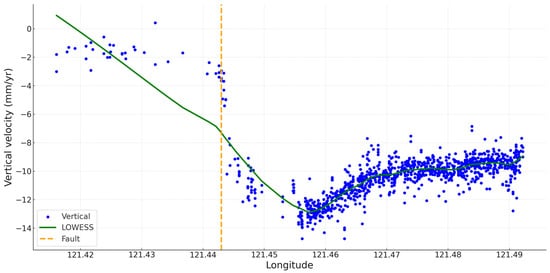

Figure 11 and Figure 12 provide profile-based views of the vertical and eastward deformation rates across the fault trace (the profile is shown in Figure 1, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). In Figure 11, the vertical velocity profile shows a sharp contrast at the fault: the footwall to the west exhibits weak or near-zero subsidence, whereas the hanging wall to the east shows markedly higher subsidence rates, commonly exceeding −10 mm/yr, with peak values approaching −14 mm/yr. This deformation gradient suggests a combination of tectonic extension and non-tectonic influences such as groundwater withdrawal and sediment compaction in the Taipei Basin. These observations are consistent with leveling and hydrological studies [2,16,17].

Figure 11.

Vertical deformation velocities along the profile shown in Figure 1. Blue dots represent PSInSAR-derived vertical velocities, and the orange dashed line marks the location of the Shanchiao Fault. The entire profile lies within Holocene alluvial deposits (gravel, sand, and clay); therefore, the sharp subsidence step near the fault reflects structural control rather than lithological contrasts, with maximum subsidence rates approaching −14 mm/yr east of the fault. The green line results from locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS) filter using the original InSAR-derived velocities. LOWESS is applied to Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

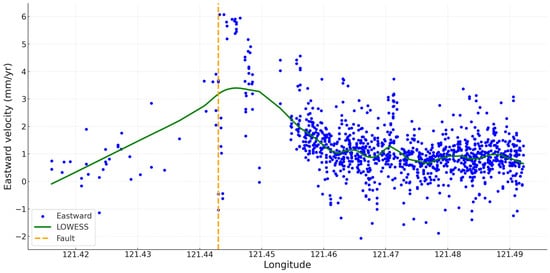

Figure 12.

Eastward deformation velocities along the profile1 shown in Figure 1. Blue dots represent PSInSAR-derived eastward velocities, and the orange dashed line marks the location of the Shanchiao Fault. The entire profile lies within Holocene alluvial deposits (gravel, sand, and clay), so the velocity discontinuity near the fault reflects structural control rather than lithological contrasts, with peak eastward velocities of ~6 mm/yr close to the fault.

The eastward velocity profile in Figure 12 further underscores the kinematic asymmetry across the fault. West of the fault, eastward motion is negligible (near 0 mm/yr), indicating a relatively stable footwall block. In contrast, the hanging wall displays a progressive increase in eastward velocity, peaking at ~6 mm/yr immediately east of the fault and tapering gradually basin ward. This pattern resembles distributed extension or clockwise rotation rather than a sharp velocity step, which would be expected if shallow fault creep were present.

Together, the vertical and horizontal velocity profiles do not support the presence of discrete, surface-breaching slips along the southern segment of the Shanchiao Fault. Instead, they point to a broad deformation zone where strain is distributed over several kilometers. This is consistent with prior geophysical interpretations that the southern Shanchiao Fault is either inactive near the surface or deforms in a ductile or segmented manner [21]. Moreover, the gradual velocity transitions across the fault zone suggest lithological and hydrological controls on surface deformation, superimposed on a regional tectonic extension regime.

In summary, the combined evidence from PSInSAR velocity maps and fault-crossing profiles highlights a strong kinematic contrast across the southern Shanchiao Fault. However, the deformation characteristics deviate from those expected of a classic normal fault with surface rupture. Instead, they point to a complex interplay of tectonic stretching, sediment compaction, and anthropogenic subsidence in shaping the present-day surface deformation of the Taipei Basin.

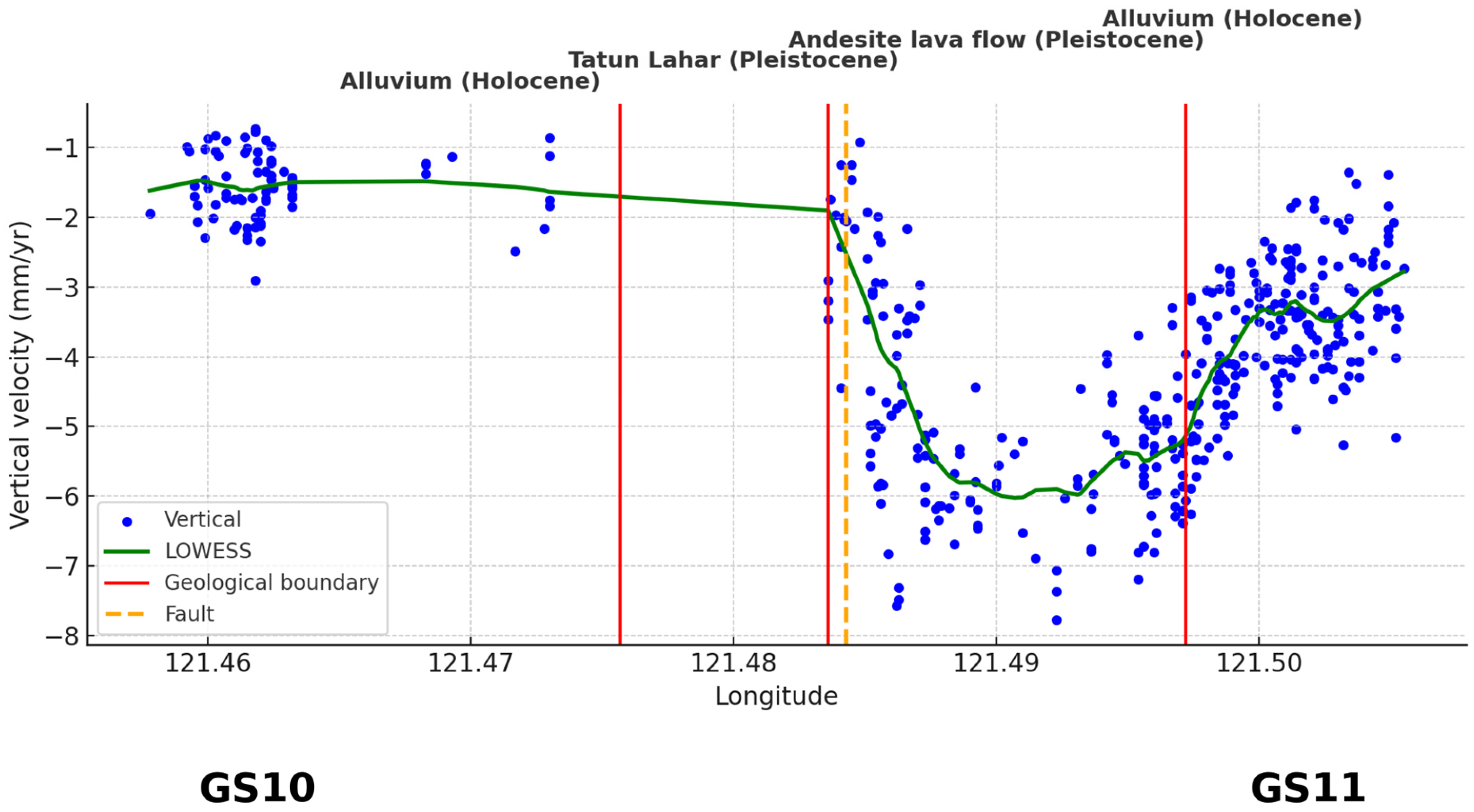

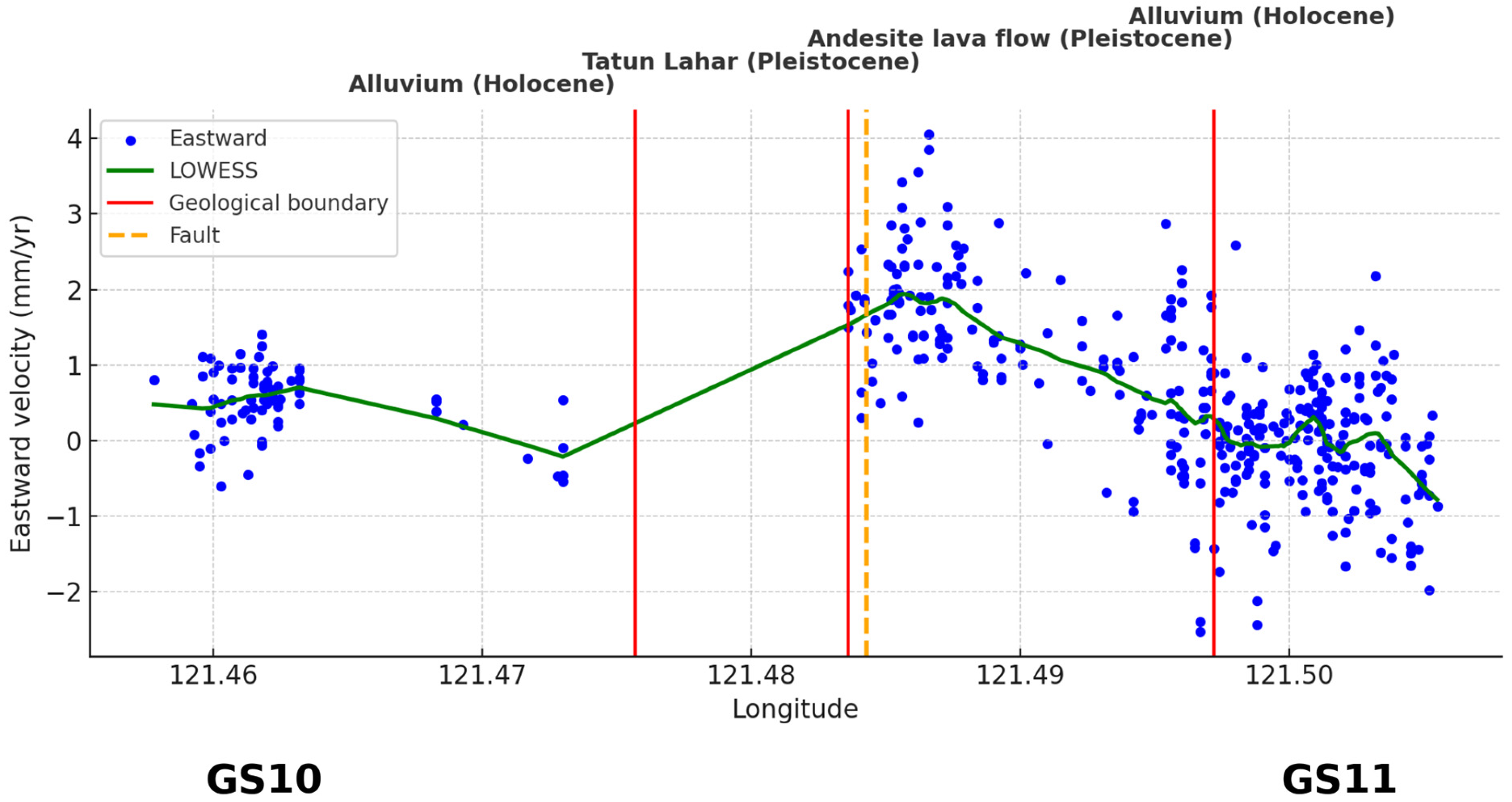

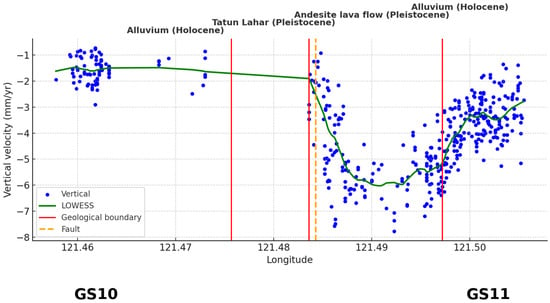

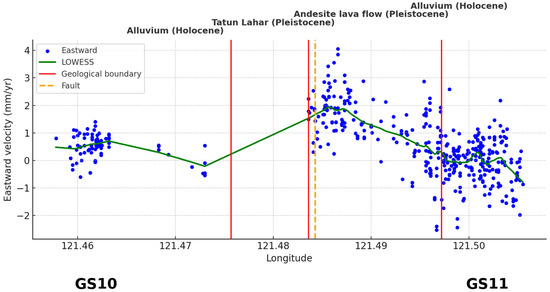

To further integrate lithologic information with the deformation signals, we extracted an additional profile across the Shanchiao Fault between Beitou and Shilin, crossing GNSS stations GS10 and GS11 (Figure 1). The vertical (Figure 13) and eastward (Figure 14) velocity profiles clearly show distinct deformation patterns across different lithologies: Alluvium (Holocene), Tatun Volcano Group—Lahar (Pleistocene), Tatun Volcano Group—Andesite lava flow (Pleistocene), and Alluvium (Holocene). The Shanchiao Fault coincides with the boundary between the Lahar and Andesite units at ~121.484°E, indicating that the deformation discontinuity is lithologically controlled. The vertical velocities reveal a sharp subsidence gradient, while the eastward velocities highlight systematic lateral offsets, both of which are enhanced by lithologic contrasts. Together, these results suggest that the distributed strain across the Shanchiao Fault reflects a combined effect of faulting, lithologic mechanical contrasts, and possible hydrogeological differences.

Figure 13.

Vertical deformation velocities along the profile2 as in Figure 11 (see also Figure 1) across the Shanchiao Fault. Blue dots represent PSInSAR-derived vertical velocities, the green line shows the LOWESS fit, and the orange dashed line indicates the location of the Shanchiao Fault. The vertical red lines divide the geological units along the profile: Alluvium (Holocene), Tatun Volcano Group—Lahar (Pleistocene), Tatun Volcano Group—Andesite lava flow (Pleistocene), and Alluvium (Holocene). The locations of GNSS stations GS10 (left) and GS11 (right) are also marked.

Figure 14.

Eastward deformation velocities along the profile2 as in Figure 11 (see also Figure 1) across the Shanchiao Fault. Blue dots represent PSInSAR-derived eastward velocities, the green line shows the LOWESS fit, and the orange dashed line indicates the location of the Shanchiao Fault. The vertical red lines divide the geological units along the profile: Alluvium (Holocene), Tatun Volcano Group—Lahar (Pleistocene), Tatun Volcano Group—Andesite lava flow (Pleistocene), and Alluvium (Holocene). The locations of GNSS stations GS10 (left) and GS11 (right) are also marked.

5.4. Uplifts and Eastward Motions in Northeastern Taoyuan City and Linkou Township in New Taipei City

In the northeastern portion of Taoyuan City and adjacent Linkou Township in New Taipei City, our PSInSAR decomposition reveals coherent and localized surface uplift alongside positive eastward velocities. As shown in Figure 9, vertical rates in these zones exceed +2 mm/yr relative to TAN2. Simultaneously, the eastward velocity map (Figure 8) shows horizontal motion of approximately +1 to +2 mm/yr, highlighting a zone of combined uplift and eastward displacement.

These signals are not isolated to single pixels but appear in clusters of PS points with consistent deformation trends, suggesting they are not artifacts of noise or atmospheric delay. Precision leveling data from benchmarks in northeastern Taoyuan (Figure 3), confirm long-term elevation gain in this area, providing independent validation of the PSInSAR vertical results.

The combined presence of uplift and eastward motion may reflect interactions between localized tectonic processes and hydrogeologic effects. The area lies near the edge of the subsiding Taipei Basin and may be subject to basin-edge flexure or the accumulation of elastic strain at the transition between basin fill and more competent bedrock. The eastward component of motion aligns with regional tectonic models indicating clockwise rotation of northern Taiwan [21], and may represent the far-field expression of larger block movement. Notably, this dual signal of uplift and eastward motion has not been previously highlighted in earlier InSAR studies, emphasizing the improved resolution and spatial coverage of the current PSInSAR dataset. It complements localized deformation studies over the Tatun Volcano Group [23].

Given the localized nature and persistence of the observed deformation, this region should receive increased attention for future monitoring. Continued uplift and horizontal displacement could indicate evolving tectonic strain or subtle structural adjustments, which may have implications for long-term infrastructure stability, hazard potential, or groundwater–fault interactions. High-resolution geodetic monitoring, combined with structural and geological investigations, will be critical for evaluating the underlying mechanisms and assessing possible risks in this transition zone between the Taipei Basin and the western foothills.

Further investigation of this region should consider both structural and multiple datasets to differentiate between fault-related uplift and non-tectonic drivers. The integration of PSInSAR with long-term GNSS and geodynamic models will be essential for constraining the origin and persistence of this deformation pattern.

5.5. Implications for Nuclear Power Stations

Using the decomposed PSInSAR velocity fields (2017–2022), we quantified ground motion around Taiwan’s coastal nuclear facilities via circular buffers centered at each site. For Station 1 (Chin-shan) and Station 2 (Kuosheng) we considered 0.5 km, 1 km, and 2 km radii; for Station 4 (Longmen) we report a 5 km radius due to sparse persistent scatterers (PS) in the near field. For each buffer we summarize PS sampling density, median eastward and vertical rates, and a local vertical plane-fit gradient (mm yr−1 km−1) as a compact measure of spatial smoothness. Table 5 summarizes the parameters used to assess vertical deformation around the three nuclear power plants.

Table 5.

Parameters used in the analysis of the vertical deformations around the three nuclear power plants (NPP1, 2 and 4; Figure 1).

At NPP1 (Chin-shan), deformation magnitudes are low and spatially smooth across all examined radii. Within 0.5 km, the eastward motion is −0.30 mm yr−1 and the vertical motion −1.04 mm yr−1, with a vertical gradient of 0.60 mm yr−1 km−1. At 1 km, the values remain nearly unchanged (eastward −0.23, vertical −1.04, gradient 0.51). Even at 2 km, the results show little variation (eastward −0.25, vertical −1.07, gradient 0.18), confirming the absence of localized deformation.

At NPP2 (Kuosheng), motions are also small in magnitude and smooth. The eastward component shifts slightly positive, from +0.44 mm yr−1 at 0.5 km to +0.57 mm yr−1 at 2 km, while the vertical component remains stable near −1.15 mm yr−1. The corresponding gradients decline steadily from 1.11 to 0.21 mm yr−1 km−1, suggesting no anomalous deformation features in the vicinity.

At NPP4 (Longmen), the PS density within 1–2 km is too sparse for reliable assessment. At 5 km, limited sampling (24 PS, 0.31 PS km−2) indicates moderate but spatially smooth subsidence, with eastward motion of −1.84 mm yr−1, vertical subsidence of −3.72 mm yr−1, and a gradient of 0.23 mm yr−1 km−1. Given the data scarcity, these values must be interpreted with caution.

Taken together—and considering the leveling-based vertical accuracy (RMSD ≈ 1.27 mm yr−1; see Section 4.5)—no significant deformation anomalies or sharp gradients are detected around NPP1 and NPP2 between 2017 and 2022. For NPP4, the lack of near-field PS highlights the need for continued monitoring with sensors more suitable for coastal and vegetated terrain (e.g., L-band SAR) and/or denser GNSS deployments to ensure robust coverage. These findings directly revisit the infrastructure safety concerns raised in the Introduction and reinforce the importance of sustained geodetic surveillance at critical facilities.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of PSInSAR in resolving vertical and eastward deformation across northern Taiwan by integrating multi-track Sentinel-1A imagery and decomposing LOS velocities after correcting for northward motion. The results, validated against precision leveling and GNSS data, reveal key deformation features, including widespread (but minor) subsidence in the Taipei Basin, localized uplift in northeastern Taoyuan and Linkou, and eastward motions consistent with tectonic extension and block rotation. The decomposed velocity fields provide spatially continuous observations that complement and enhance ground-based geodetic monitoring networks.

By capturing both vertical and eastward components of surface motion, this work shows the potential interplay between tectonic structures—such as the Shanchiao Fault—and hydrological or anthropogenic processes in the region. The use of GNSS and leveling data is critical for validating the quality of our InSAR results. These three datasets can also be fused into a joint velocity field, as demonstrated in other studies. The methodology developed in this study can also be applied to other parts of Taiwan exhibiting significant horizontal motions, such as the Tainan, Kaohsiung, Pingtung, and eastern Taiwan regions, where GNSS data reveal large west–east velocities [1].

It should be noted that the Sentinel-1A satellite operates at C-band, which is limited in its ability to penetrate dense vegetation. As a result, PSInSAR analysis is often restricted in forested or rugged terrains such as the TVG. Future studies may benefit from incorporating L-band SAR imagery from missions such as ALOS and ALOS-2, which are better suited for coherent signal retrieval in vegetated areas. This would enhance the detectability of vertical and eastward deformation in geologically critical but observationally challenging zones. Future efforts should also aim to extend the temporal baseline, incorporate additional GNSS and leveling data, and apply this approach to other high-risk regions in Taiwan and beyond.

Author Contributions

C.H. and H.-M.H. conceptualized the initial idea and experimental design. C.H. and S.G. wrote the manuscript. H.-M.H. carried out the initial computations, which were upgraded and finalized by S.G. and S.-H.L. commented and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under grant numbers: 112-2221-E-A49-025-MY3 and 113-2611-M-A49-001.

Data Availability Statement

Free Sentinel-1A SAR images were provided by the European Space Agency. Free GNSS data were provided by Academia Sinica at https://tgm.earth.sinica.edu.tw (accessed on 13 October 2025). The precision leveling data a were provided by the Water Resources Agency of Taiwan by request.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under grant numbers: 112-2221-E-A49-025-MY3 and 113-2611-M-A49-001.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shao-Hung Lin was employed by the company Green Environmental Engineering Consultant Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, S.-B.; Chen, H.-Y.; Kuo, L.-C. Velocity field of GPS stations in the Taiwan area. Tectonophysics 1997, 274, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, H.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hu, J.-C.; Ching, K.-E.; Chen, H.; Yang, K.-H. Transient deformation induced by groundwater change in Taipei metropolitan area revealed by high resolution X-band SAR interferometry. Tectonophysics 2016, 692, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lanari, R.; Mora, O.; Manunta, M.; Mallorquí, J.J.; Berardino, P.; Sansosti, E. A small-baseline approach for investigating deformations on full-resolution differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, A.; Segall, P.; Zebker, H. Persistent scatterer interferometric synthetic aperture radar for crustal deformation analysis, with application to Volcán Alcedo, Galápagos. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, B07407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farolfi, G.; Del Soldato, M.; Bianchini, S.; Casagli, N. A procedure to use GNSS data to calibrate satellite PSI data for the study of subsidence: An example from the north-western Adriatic coast (Italy). Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 52, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sandwell, D.T.; Klein, E.; Bock, Y. Integrated Sentinel-1 InSAR and GNSS Time-Series Along the San Andreas Fault System. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2021JB022579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemrabet, L.; Doin, M.-P.; Lasserre, C.; Durand, S. Referencing of Continental-Scale InSAR-Derived Velocity Fields: Case Study of the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2022JB026251. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Qu, C.; Zhao, D.; Shan, X.; Li, C.; Dal Zilio, L. Large-Scale Extensional Strain in Southern Tibet from Sentinel-1 InSAR and GNSS Data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL110512. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A.R.; Elliott, J.R.; Lazecký, M.; Maghsoudi, Y.; McGrath, J.D.; Walters, R.J. An InSAR–GNSS Velocity Field for Iran. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL108440. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, T.; Garthwaite, M.C. Resolving three-dimensional surface motion with InSAR: Constraints from multi-geometry data fusion. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, K.R.; Huang, M.H. Revealing crustal deformation and strain rate in Taiwan using InSAR and GNSS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, W.S.; Hanssen, R.F. A treatise on InSAR geometry and 3-D displacement estimation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, W.S.; Hanssen, R.F. Estimating three-dimensional displacements with InSAR: The strapdown approach. J. Geod. 2024, 98, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, W.C.; Hwang, C.; Tosi, L.; Lin, S.H.; Tsai, P.C.; Chen, Y.A.; Wang, W.J.; Li, E.C.; Ge, S. Toward sustainable inland aquaculture: Coastal subsidence monitoring in Taiwan. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 30, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Resources Agency (WRA). Monitoring and Analyzing Land Subsidence of Taipei, Chiayi, Tainan, Pingtung and Yilan Area in 2023; Water Resources Agency: Taichung, Taiwan, 2023; Available online: https://gpi.culture.tw/books/1011201941 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Chen, C.-T.; Hu, J.-C.; Lu, C.-Y.; Lee, J.-C.; Chan, Y.-C. Thirty-year land elevation change from subsidence to uplift following the termination of groundwater pumping and its geological implications in the Metropolitan Taipei Basin, Northern Taiwan. Eng. Geol. 2007, 95, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, P.A.; Gurrola, E.; Sacco, G.F.; Zebker, H. The InSAR scientific computing environment. In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2012, 9th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, Nuremberg, Germany, 23–26 April 2012; pp. 730–733. [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert, D.P.S.; Walters, R.J.; Wright, T.J.; Hooper, A.J.; Parker, D.J. Statistical comparison of InSAR tropospheric correction techniques. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 170, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-P.; Yen, J.-Y.; Hooper, A.; Chou, F.-M.; Chen, Y.-A.; Hou, C.-S.; Hung, W.-C.; Lin, M.-S. Monitoring of surface deformation in northern Taiwan using DInSAR and PSInSAR techniques. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2010, 21, 447. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, R.-J.; Ching, K.-E.; Hu, J.-C.; Lee, J.-C. Crustal deformation and block kinematics in transition from collision to subduction: GPS measurements in northern Taiwan, 1995–2005. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, B09404. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.H.; Hu, J.C.; Wang, S.J. Assessing potential groundwater storage capacity for sustainable groundwater management in the transitioning post-subsidence metropolitan area. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036951. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, R.-F. Mapping Surface Deformation Over Tatun Volcano Group, Northern Taiwan Using Multitemporal InSAR. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).