Abstract

In the face of growing demand for marine nutrition and restrictions on wild fish capture, mariculture offers significant potential to enhance marine food production. The natural environment directly influences the growth of marine organisms, but socio-economic conditions are equally critical for sustainable and efficient development. This study investigated the multifaceted factors shaping mariculture in China, Vietnam, and India. We analyzed the natural environment and social economy qualitatively and quantitatively by adopting zonal statistics, chart analysis, and correlation analysis. Results show that all three countries generally possess suitable marine environments for the growth of cultured species. Meanwhile, China and Vietnam demonstrate how robust socio-economic systems and strategic policy support drive successful mariculture development, whereas India’s comparatively underdeveloped socio-economic foundation appears to constrain its sectoral advancement. These analyses suggest a principle: the natural environment is the necessary condition and the social economy serves as the sufficient condition, together determining the state of mariculture. Our study highlights the joint role of environmental suitability, socio-economic readiness, and policy frameworks, providing valuable insights for identifying potential mariculture sites and informing policy strategies to promote sustainable marine aquaculture globally.

1. Introduction

With the global population growing and living standards improving, the demand for food—particularly high-nutrient food—is increasing significantly [1]. While land-based food production faces constraints from water scarcity and limited arable land [2], the ocean offers immense potential for meeting future food demands [3,4]. Marine-derived food, sourced from both wild capture fisheries and mariculture, currently supplies 17% of the global meat consumption [5,6]. Regions differ in their reliance on capture fisheries versus aquaculture, but together these sectors sustain local seafood demands. Notably, in 2022, global aquaculture production accounted for 51% of total fishery output, surpassing capture fisheries for the first time [7]. Though capture fishery production is twice that of aquaculture in marine areas, it has shown a relatively stagnant trend [7,8]. It is foreseeable that there will be more and more edible marine production coming from mariculture [1]. However, expectations of where and how quickly mariculture will expand are fraught with uncertainty [9,10]. Thus, identifying the factors that constrain or promote mariculture expansion is essential for guiding regional development, ensuring food security, and addressing global nutrition needs.

The future of mariculture is closely tied to its site selection, which has been a key research focus: where is suitable for mariculture development [11]? These studies primarily examine environmental constraints such as temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and sea water velocity, which are necessary conditions for successful mariculture [8,12,13,14]. While environmental factors dominate current site selection research, socio-economic benefits afforded by mariculture have gained increasing attention [15,16]. In addition, documented studies also suggest that the broader socio-economic conditions of a region or nation influence both the direction and success of mariculture expansion. On a macro level, governments play a critical role in shaping the trajectory of the mariculture industry through policies and national strategies [17,18]. For example, in Canada, national legislation on aquaculture is considered urgently needed to leverage its potential role in the blue economy strategy. When it comes down to the individual, people’s preferences and acceptability of fish as a food [19], as well as concerns about the potential negative impacts of mariculture [20], significantly shape the industry’s success. The planning for aquaculture development also ought to meet the needs and priorities of stakeholders [21,22]. Moreover, the evaluation of green development in Chinese oyster mariculture shows that low regional economic income has a passive effect [23]. In fact, economic, social, and environmental outcomes are considered to be mutually reinforced in global aquaculture systems [24].

A global spatial distribution of offshore surface mariculture published by Liu et al. [25] demonstrates the spatial heterogeneity of mariculture distribution and deepens the understanding of the uneven development of this sector. Such disparities are evident not only globally but also within Asia. In 2023, China alone accounted for approximately 73% of Asia’s mariculture output, while countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam also acted as active producers [7]. By contrast, the output from nations including India and Iran remained minimal. From a supply–demand perspective, densely populated Asian countries theoretically possess a stronger impetus to develop mariculture. Although freshwater aquaculture in several countries serves as a substantial source of aquatic products—meeting domestic demand while also augmenting global supply—sustained demographic growth underscores the necessity of adopting an integrated perspective on terrestrial and marine food systems [26]. Investigating the multifaceted factors that influence mariculture development may open novel pathways for enhancing food production in nations where it is currently underutilized.

Here, we explore various factors shaping the state of mariculture, ranging from natural environmental conditions to socio-economic dimensions. We examine mariculture in China, Vietnam, and India—three countries with distinct developmental trajectories—to derive comparative insights; a more detailed explanation is provided in Section 2.1. Mariculture here is construed broadly to encompass all forms of marine-based cultivation of aquatic foods, without distinction among species. Our analysis begins by assessing the marine environments of these countries to determine whether natural conditions constrain the emergence of mariculture. Then, we investigate the role of socio-economic factors in driving mariculture expansion, using time-series data. Specifically, we combine qualitative and quantitative analysis by employing zonal statistics, chart analysis, and correlation analysis. Additionally, we investigate the influence of policy frameworks on mariculture development. Overall, we demonstrate the necessary and sufficient conditions for the development of mariculture, providing actionable insights for its sustainable growth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

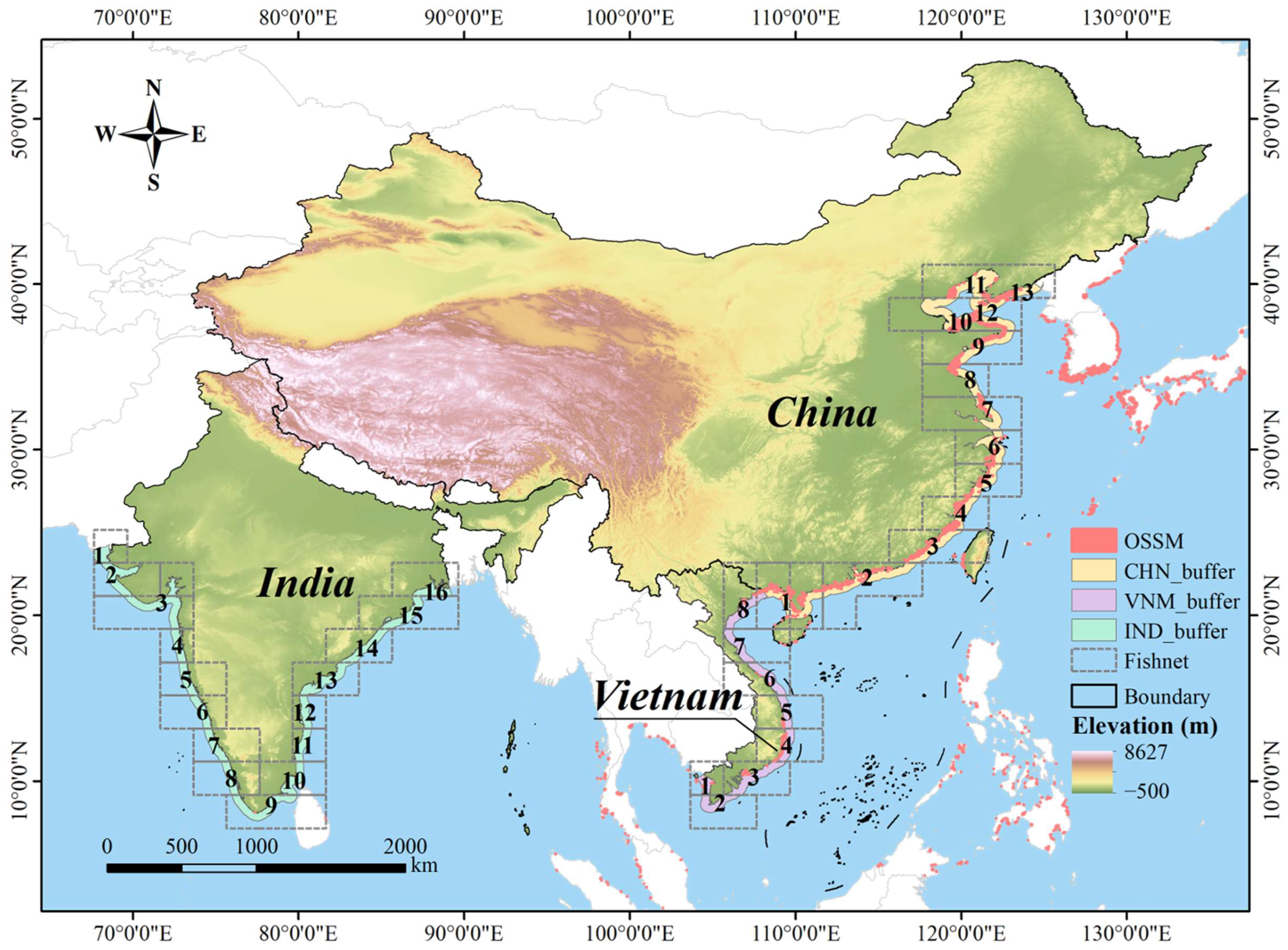

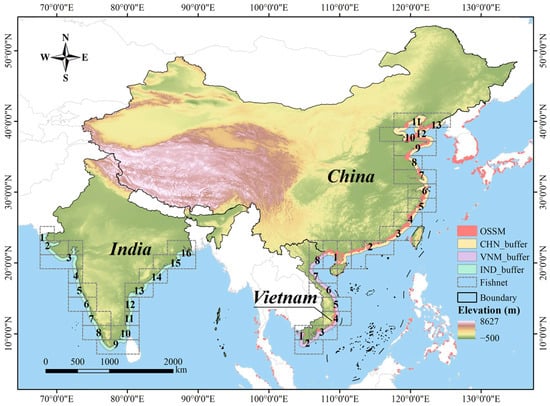

The research focused on three neighboring Asian countries: China, Vietnam and India (Figure 1). Liu et al. [25] counted the area of mariculture and showed that China ranked first in terms of overall offshore surface seawater mariculture area and Vietnam ranked sixth, accounting for 2.32% of the total. By comparison, there was almost no mariculture in India. These three countries can effectively characterize the high, medium, and low development levels of mariculture.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the study areas and partition of the buffer zone. The buffers of China, Vietnam and India were divided into 13, 8 and 16 zones respectively, and the serial numbers of each zone are shown in the figure.

China (3°52′–53°34′ N, 73°33′–135°05′ E) has a long coastline and vast sea area, with diverse climate changes from north to south. It shares a border with Vietnam (8°10′–23°24′ N, 102°09′–109°30′ E), and their sea areas are connected. Vietnam and India (8°24′–37°36′ N, 68°7′–97°25′ E) share a significant latitude overlap and exhibit a comparable climate, belonging to the tropical monsoon climate. The geographical analogy among the three countries is of great value. Moreover, China, Vietnam and India are all coastal continental countries with abundant land resources and diverse industries and cultures in Asia, which makes their socio-economic conditions comparable. The similarity and diversity allow for a comparative analysis of the multiple factors influencing mariculture among the above three countries. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the three countries.

2.2. Data and Preprocessing

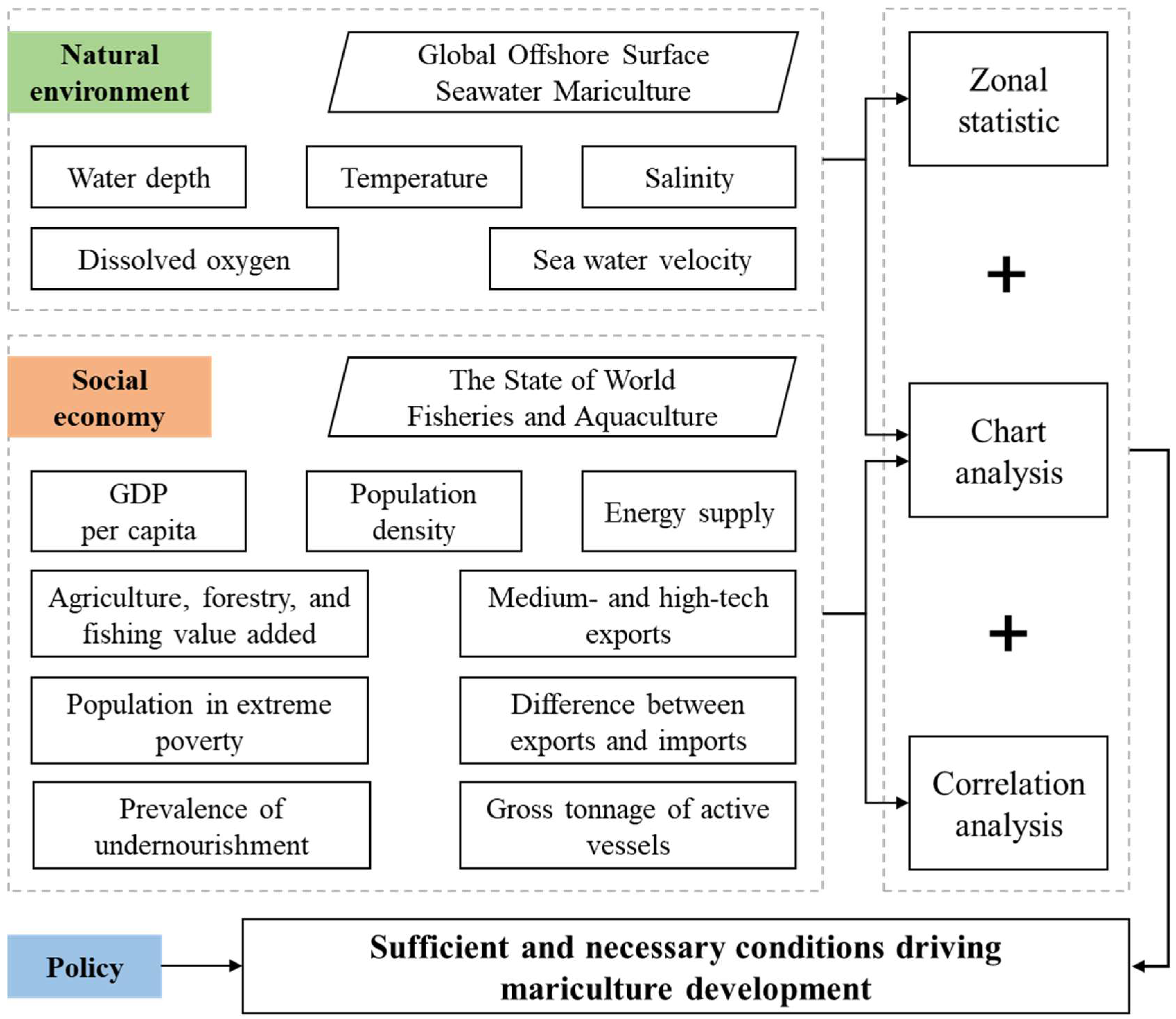

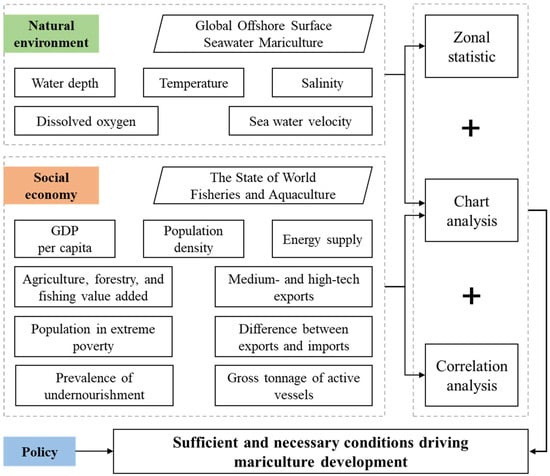

This study mainly unfolded in two distinct stages, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the multi-factor analysis of the development of mariculture.

Initially, we explored whether the natural factors constrained the development of mariculture without distinguishing between specific mariculture species, as we sought to derive broader conclusions. Investigating previous studies [12,13,16,27], we finally chose six natural indicators that may affect the growth of marine organisms: water depth, temperature, dissolved oxygen, salinity, sea water velocity and chlorophyll concentration (Table 1). The cost of mariculture increases with the depth of water [28], and adequate water depth is an essential factor when selecting sites for mariculture [8]. The physiological health of farmed species is affected by temperature; therefore, optimal temperature determination is an important practice in mariculture [29]. Dissolved oxygen plays a significant role in mariculture: if the oxygen concentration is reduced far enough, it can cause reduction in fitness and even death [30]. Salinity influences the growth of ocean species [31], which can be cultivated better in a suitable range. Appropriate water currents contribute to water circulation and are beneficial to the supply of dissolved oxygen and food particles and the dissipation of waste products [32]. Phytoplankton concentration is positive for the feeding and growth of bivalves [33], whereas excessively high or low values may impair their health. Thus, chlorophyll concentration is equally important for mariculture. Water depth data was derived from GEBCO_2023 Grid, which provides elevation data on a 15 arc-second interval grid. Other environmental data could not be used directly and we did some preprocessing.

Table 1.

Data summarization. The sector relates to the field of data.

The temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen data utilized in our study were obtained from the World Ocean Atlas (WOA), which were produced based on profile data from the World Ocean Database (WOD). The salinity indicator here was unitless. Every data point includes ocean information at different depths ranging from the sea surface to 1500 m underwater. To facilitate subsequent analysis, we adopted the aforementioned data at the depth of 5 m and interpolated it using Inverse Distance Weighting methods [34]. Thus, the vector point data was converted to raster data with a resolution of 15 arc seconds (the same as occurrence rasterized data).

Copernicus Marine Service provides free and open-access marine data and services to enable scientific innovation, and Global Ocean Physics Analysis and Forecast production delivers a special dataset for surface current which also includes wave and tidal drift, which is called SMOC (Surface Merged Ocean Current). The sea water velocity data (netCDF-4 format) was obtained from it. Eastward sea water velocity and northward sea water velocity are two types of variables included in the data. We calculated the vector sum of the two variables to produce the actual sea water velocity, making no distinction between directions. Utilizing the package netCDF4 provided by Python 3.12, the netCDF-4 data was converted to raster format.

The Ocean Biology Processing Group (OBPG) of NASA supported our analysis by providing chlorophyll concentrations. We chose the production of concentrations generated based on the Aqua-MODIS instrument, and the format was netCDF4. Similarly, the data was converted to raster format.

In the second part of the study, we sought to answer whether fishery production was related to social and economic development; several macro-level indicators were considered. A country’s economic development can be demonstrated through factors such as gross domestic product, industrial structure, and the proportion of high-tech industries. From the perspective of supply and demand, residents’ dietary habits will affect the production of marine food. Related facility resources also have an impact on mariculture. In addition, referring to the assessment of the sustainable development of aquaculture [24,35], we adopted some socio-economic indicators. The period of socio-economic analysis in this paper was from 1990 to the present.

In conclusion, we combined global offshore surface seawater mariculture data (OSSM) [25] and ocean environmental data to research the influence of geographical environment, and based on long-term statistics data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, the socio-economic impact was explored. The data employed in this study is summarized in Table 1.

2.3. Zonal Statistics of Natural Factors

The comparative analyses here proceed from the premise that the mere presence of mariculture in a region implies that its natural conditions are suitable for the cultured species. Given that observed mariculture in India is negligible, we primarily compared India with the reference countries of China and Vietnam to investigate whether the marine environment along the Indian coast is unsuitable for the establishment of mariculture farms. Past research shows that more than 90% of China’s mariculture area is located in the marine area within 20 km of the coastline [36]. Given the rationality and computational complexity of the analysis, we focused our study within a 50 km offshore marine zone. Only mainland areas of the three countries were considered, with the buffer zone defined using the continental shoreline as the baseline. The geographical characteristics of the three countries necessitated a refined division of the study area. China spans a wide range of latitudes, while India covers a broad longitude range. To facilitate a precise comparison of the natural environments across regions, we divided the study area. Specifically, we first established a 50 km buffer zone along the coastline towards the ocean (“CHN_buffer”, “VNM_buffer” and “IND_buffer” in Figure 1) and created 2° × 2° fishing nets covering the entire study area. Then we overlaid the fishing nets with the buffer zone, retained the intersecting parts and merged adjacent fishing nets at the same latitude. Next, the processed fishing nets were used to segment the buffer zone, completing the smaller-scale division of the buffer zone (small zone). Finally, we employed the zonal statistics tool to calculate the indicator values of each small zone and draw statistical charts based on these zone units. The above analyses were performed using ArcGIS 10.2. Figure 1 shows the partition results of the buffer zone. There were 13 zones generated in China, 8 zones in Vietnam and 16 zones in India.

2.4. Correlation Analysis of Socio-Economic Factors

The FAO categorizes fishery production into aquaculture and capture fisheries, further dividing aquaculture into marine aquaculture, brackish water aquaculture, and freshwater aquaculture. This classification provides a long-term time series of data, capturing changes over time. We sequentially used canonical correlation analysis and partial correlation analysis to explore the correlation between fishery production and socio-economic indicators in long time series. Both analyses were performed using the R 4.2.2.

Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) is one of the multivariate statistical analyses, which studies the correlation between two or more groups of random variables [37]. This method is essentially an application of Principal Component Analysis to each of the two groups in a way that maximizes the correlation between its components [38]. In this study, we selected four fishery variables, marine aquaculture, brackish water aquaculture, freshwater aquaculture and capture fisheries, and four socio-economic indicators, perGDP (GDP per capita), PopDensity (population density), MHE (medium- and high-tech exports) and AAF (agriculture, forestry, and fishing value added). The correlation between fishery variables and socio-economic indicators was tested by canonical correlation analysis. Additionally, subsets of socio-economic indicators (containing at least two variables) were analyzed to assess how different combinations influenced the correlation between fishery production and socio-economic factors.

Partial correlation analysis is a method to measure the degree of linear correlation between two variables among multiple variables under the premise of controlling the influence of other variables. The correlation coefficient ranges from 0 to 1: the larger the absolute value is, the higher the degree of correlation between the variables is [39]. This method was applied to examine three groups of variables: (1) fishery production (sum of aquaculture and capture fisheries), perGDP, PopDensity, MHE and AFF; (2) marine aquaculture, brackish water aquaculture, freshwater aquaculture and capture fisheries; (3) marine aquaculture, capture fisheries and GTActive (gross tonnage of active vessels).

By employing these two complementary statistical techniques, the study uncovered insights into the relationships between fishery production and socio-economic factors under different variable combinations and scenarios.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Natural Environment

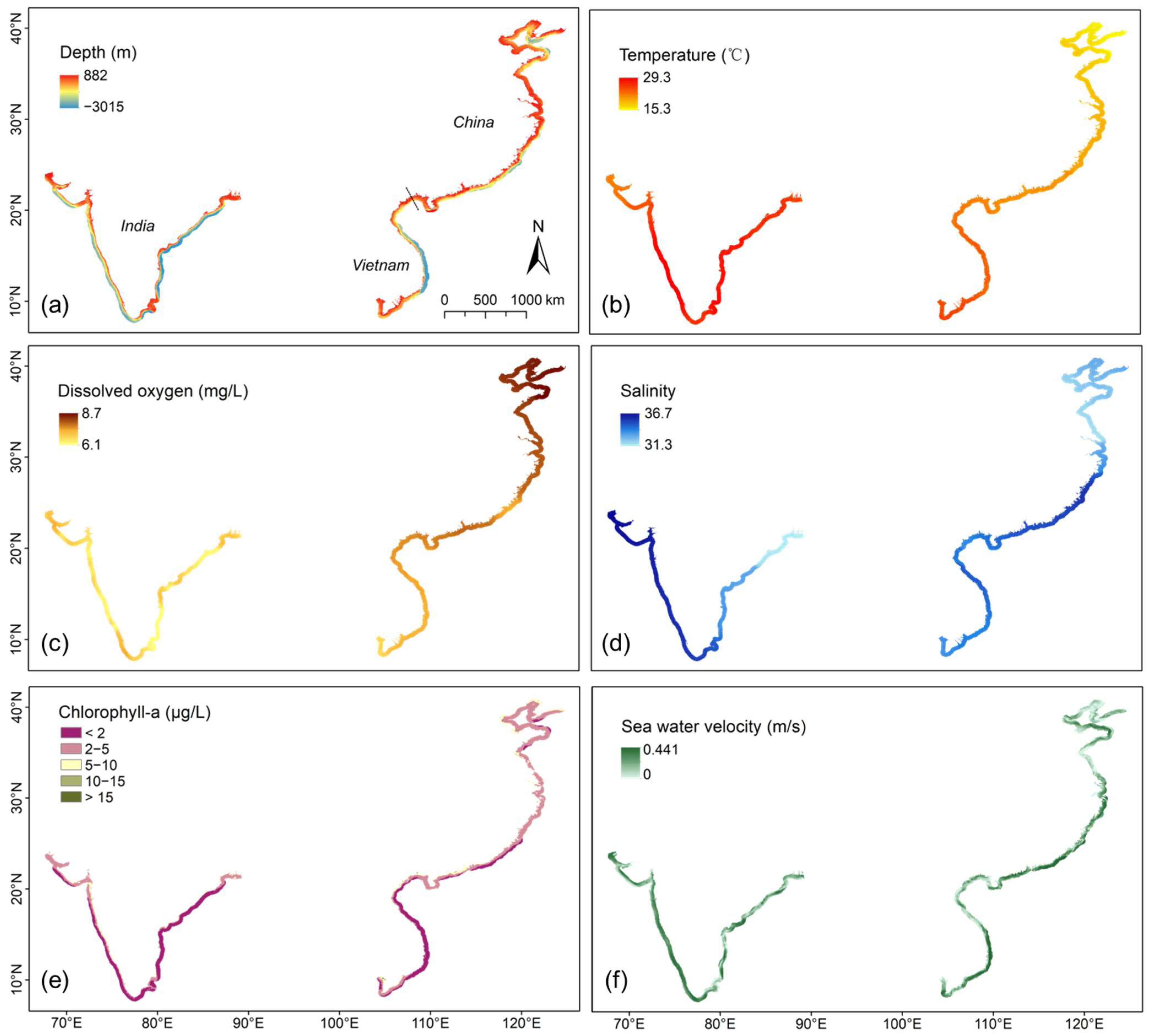

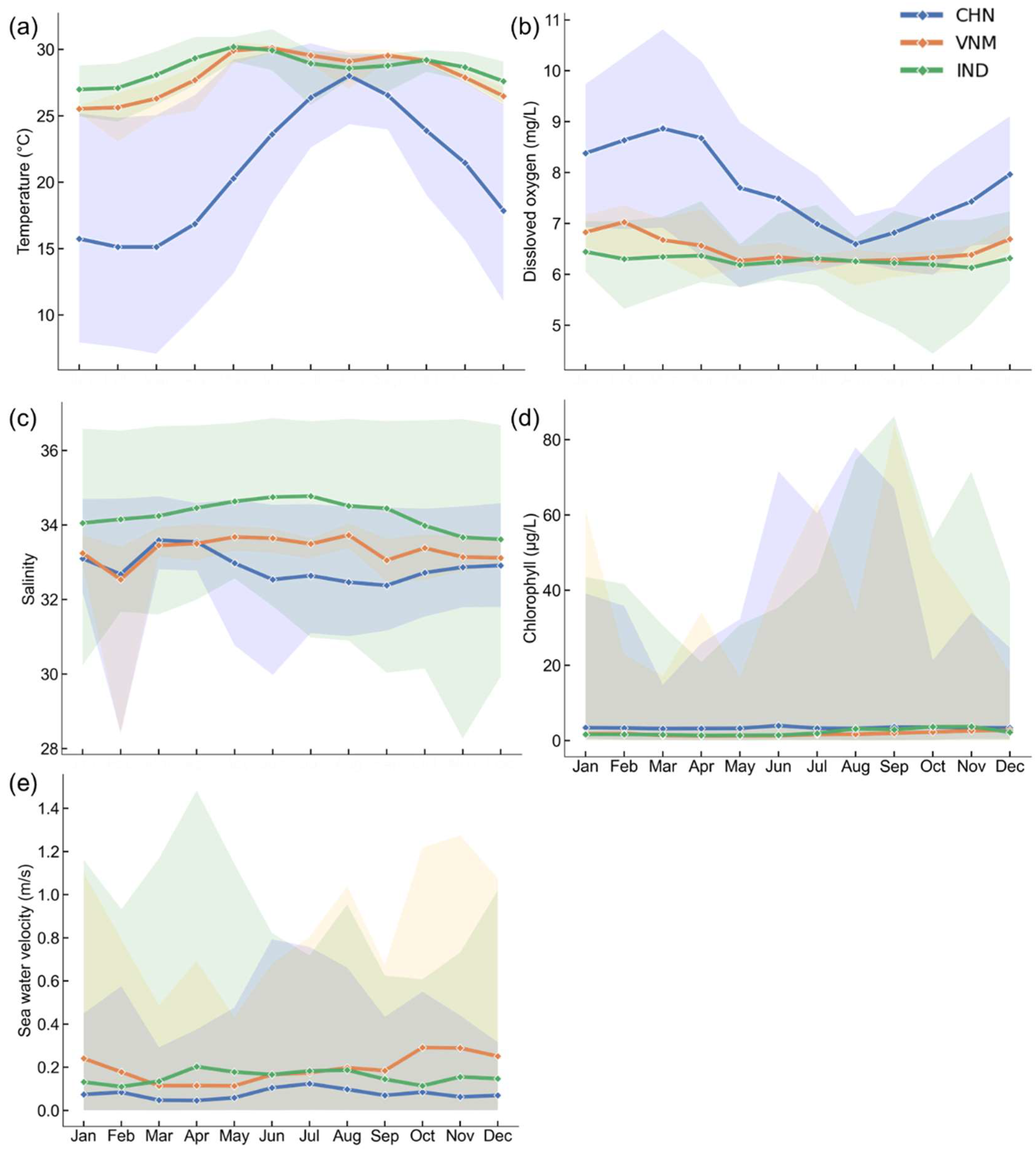

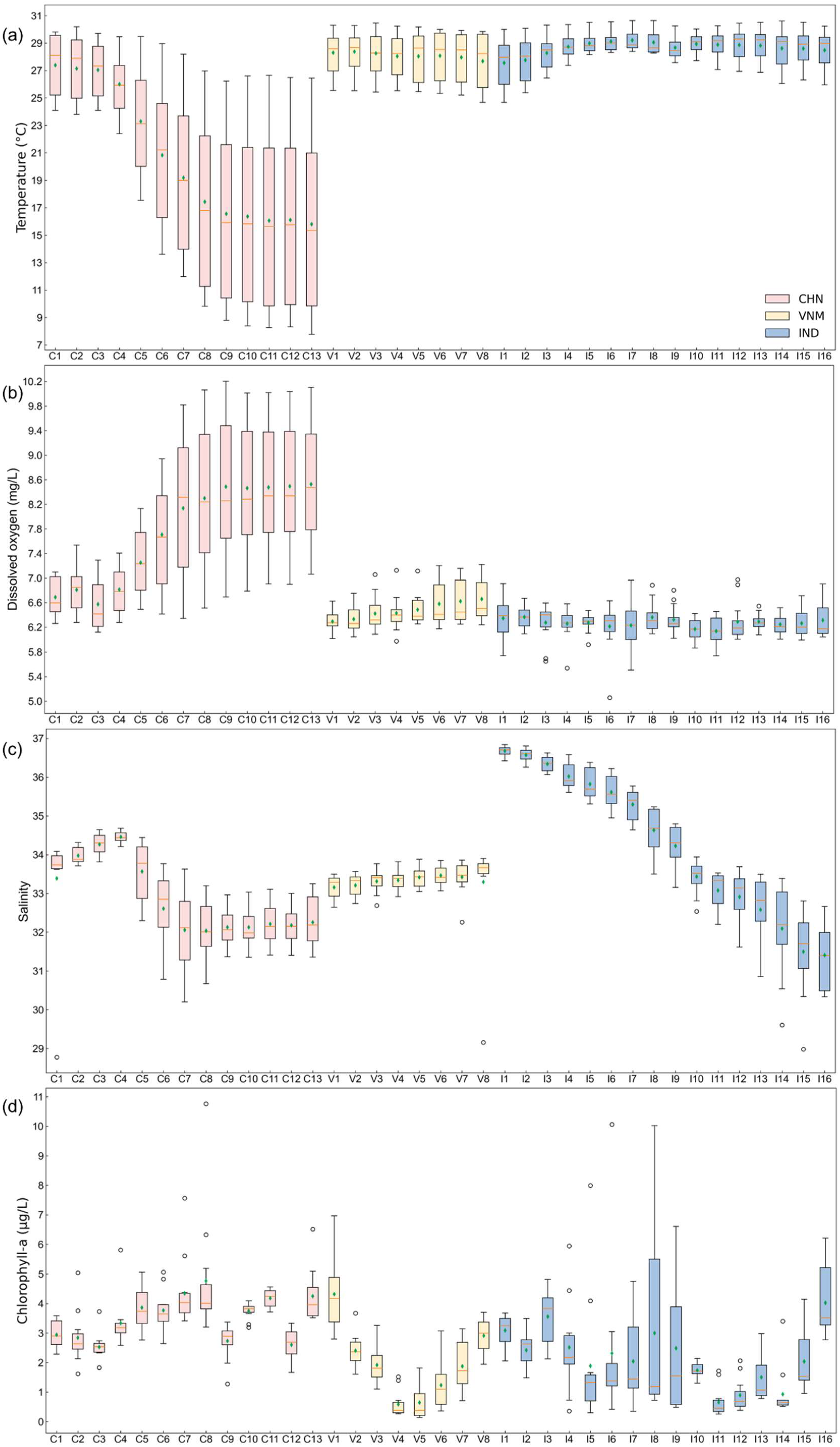

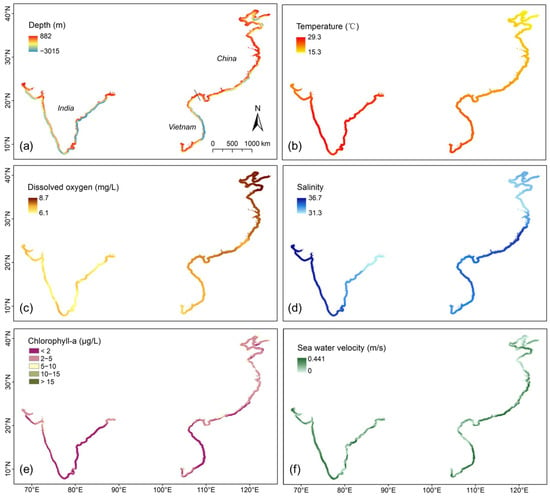

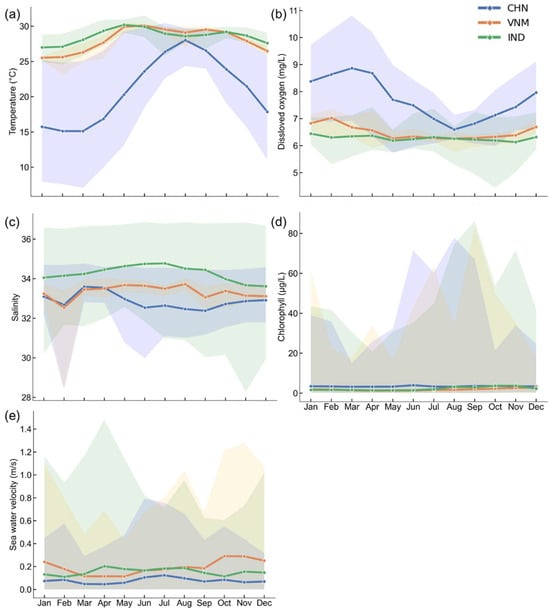

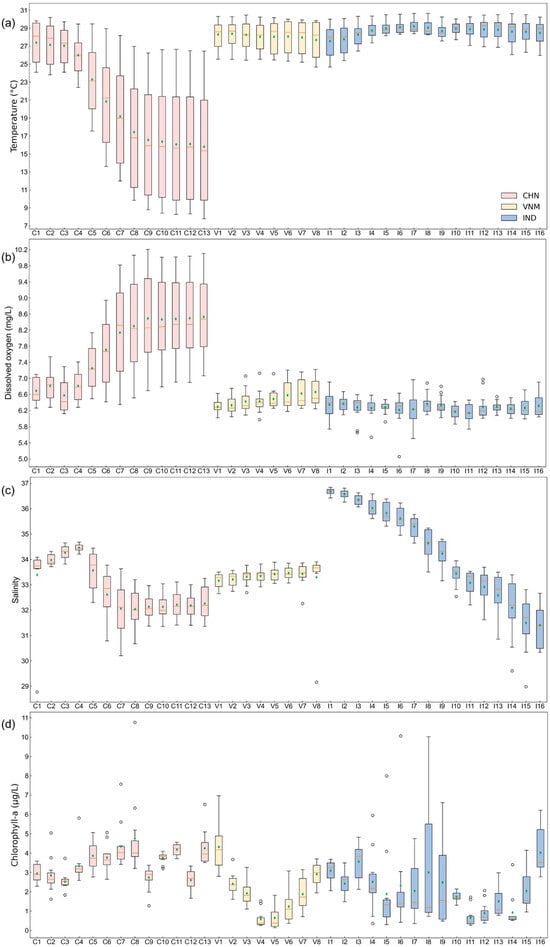

The results align closely with the study’s aims of assessing the natural environmental factors influencing mariculture across China, Vietnam, and India at multiple scales (holistic, local, temporal, and spatial). Using zonal statistics and monthly variability assessments, we evaluated key natural indicators—water depth, temperature, dissolved oxygen, salinity, sea water velocity and chlorophyll concentration—to uncover spatial and temporal patterns influencing mariculture potential. Specifically, we firstly mapped the natural indicators within a 50 km buffer zone to show the annual averages of indicators (Figure 3). Afterwards, the overall monthly changes in each country were calculated (Figure 4). In more detail, we displayed the monthly changes in each zone for each indicator by boxplot chart (Figure 5). The following is what we found.

Figure 3.

Mapping of natural environment indicators within a 50 km buffer zone. The raster value represents the annual average. (a) Seawater depth; (b) seawater temperature; (c) oxygen level in seawater; (d) salinity of seawater; (e) chlorophyll concentration; (f) sea water velocity.

Figure 4.

Monthly changes in natural environment indicators. The line represents changes in the average, and the shadow is generated from the maximum and the minimum values across all grids within the buffer zone of each month. (a) Seawater temperature; (b) oxygen level in seawater; (c) salinity of seawater; (d) chlorophyll concentration; (e) sea water velocity.

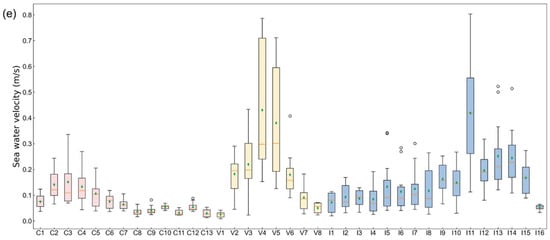

Figure 5.

Zone statistics of natural environment indicators. The boxplot shows the distribution of indicators in each zone over 12 months, where the orange line represents the median and the green diamond denotes the mean value. The x-axis labels represent the small zone segmented by fishing nets corresponding to Figure 1. (a) Seawater temperature; (b) oxygen level in seawater; (c) salinity of seawater; (d) chlorophyll concentration; (e) sea water velocity.

3.1.1. Water Depth

In terms of water depth, the gradient changes in India were more pronounced than the other two countries in the direction of 50 km towards the sea along the coastline (Figure 3a). In addition, we counted the cells with water depth between −4 and −30 m, which was mostly considered the suitable water depth for mariculture [16,40] across the three countries:

- China: 65.86% of the buffer zone had a water depth within the suitable range, supporting significant mariculture activity.

- Vietnam: 50.17% of the buffer zone had a water depth within the suitable range, not much more than India.

- India: 42.43% of the water depth was suitable, yet mariculture remains underdeveloped compared to Vietnam. Although suitable water depth does not account for a large proportion in India, development in Vietnam highlights that water depth is not inherently limiting for India.

3.1.2. Temperature

Latitude is an important factor affecting climate [41], and most of the temperature differences among the three countries also stem from latitude differences. As shown in Figure 3b, the annual average temperature in China varied significantly from north to south, while the temperatures in Vietnam and India were both high. And more detailed findings include:

- China: The temperature in zones C1–C3 (23.81–30.20 °C) was comparable to Vietnam and India (Figure 5a).

Overall, temperature was not a limiting factor in any of the three countries. When the temperature is extremely high or low, some marine species may not be suitable for cultivation, while generally there was no abnormal phenomenon in India’s seawater temperature.

3.1.3. Dissolved Oxygen

The analysis revealed:

The extremely high outliers in Vietnam and India, which were even higher than China’s dissolved oxygen concentration, were not considered unsuitable for marine aquaculture. Despite localized low values, dissolved oxygen does not broadly constrain mariculture expansion in India.

3.1.4. Salinity

As shown in Figure 3d, the annual averages of salinity were different not only among countries but also within countries. The more detailed analysis showed distinct patterns among and within countries:

- China: Salinity increased from north to south and imposed no discernible constraint on mariculture development.

- Vietnam: Zones with extremely low outliers (V3, V7, and V8: ~29–32) still supported mariculture activity (Figure 5c).

Thus, although India exhibited greater salinity variability, this factor is not uniformly prohibitive for mariculture.

3.1.5. Chlorophyll Concentration

For chlorophyll concentration, the average annual values across the three countries were predominantly low (<5g/L), with sporadic high values observed in the fjords (Figure 3e), which resulted in the large shaded area in Figure 4d.

- China: The highest annual and monthly average chlorophyll concentration among three countries (Figure 4d).

- Vietnam and India: Some extremely high outliers appeared in Figure 5d, but the changes in different zones did not show significant differences from China. The outlier in zone I6 (10.06 g/L) was still lower than the outlier in zone C8 (10.76 g/L).

On the whole, though outliers in zones were commonly present, chlorophyll concentration does not pose a constraint in the development of mariculture in India.

3.1.6. Sea Water Velocity

Figure 3f shows that the annual average sea water velocity in southern China, southern Vietnam, and western India was relatively high. The monthly average changes in sea water velocity in the three countries were similar, and the difference between the maximum and minimum values for each month was substantial (Figure 4e).

- China: The differences among zones were relatively less pronounced compared to Vietnam and India (Figure 5e).

- Vietnam: Zone V4 and V5 had significant variability (0.15–0.79 m/s and 0.13–0.71 m/s), supporting mariculture despite pronounced fluctuations (Figure 5e).

- India: Zones had extremely high outliers (I5: 0.34 m/s, I6: 0.28 m/s, I7: 0.30 m/s, I13: 0.52 m/s, and I14: 0.51 m/s) that were still lower than Vietnam’s peak (Figure 5e).

Patterns similar to Vietnam indicate that the abnormal velocity is not considered a major obstacle to the expansion of mariculture in India.

3.2. Socio-Economic Analysis

The development of socio economy is a long-term process, with the current state playing a pivotal role in both continuing past trends and laying the foundation for future progress. Meanwhile, various industries are interrelated and jointly contribute to the progress of the country. From the perspective of fishery production, we conducted a qualitative analysis of the socio-economic development of the three countries by employing statistical charts. This multi-faceted analysis highlights the interplay between fishery production, industrial development, trade, and nutrition.

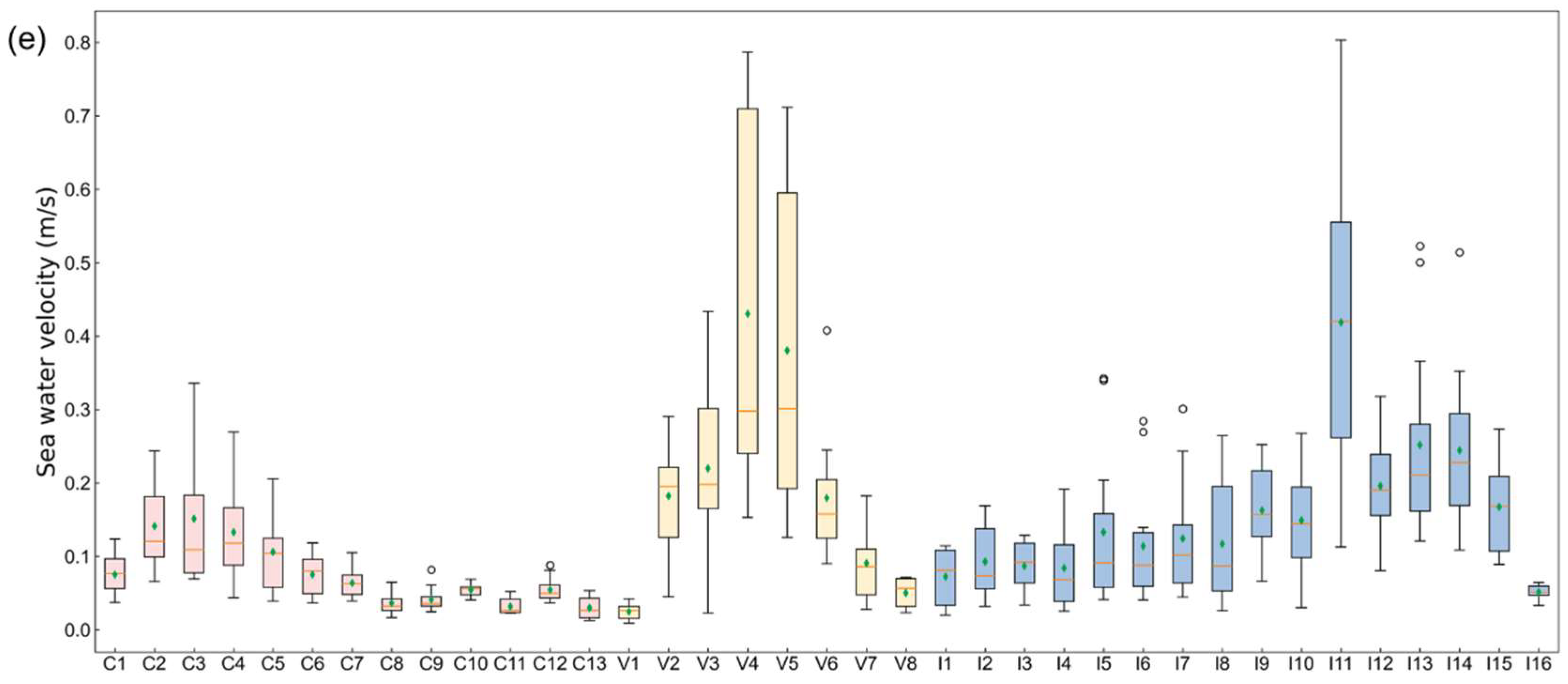

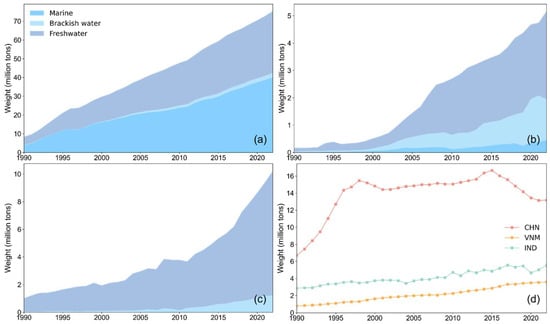

3.2.1. Fishery Production and Structure

Figure 6 shows that China’s aquaculture and capture fishery production was higher than that of Vietnam and India. In terms of aquaculture structure, China’s marine aquaculture and freshwater aquaculture occupied a dominant position (about 97% of the total), with very little brackish water aquaculture. Both freshwater and brackish water aquaculture in Vietnam were more developed than marine aquaculture, while mariculture had been growing steadily. Freshwater aquaculture was flourishing in India, about nine times that of brackish water aquaculture, and the production of marine aquaculture was negligible. Although India lagged behind Vietnam in mariculture production, its capture fishery production was higher than that of Vietnam, and the total fishery production was nearly twice that of Vietnam. It can be observed that fishery production from different sources compete within the overall fishery structure of a country, leading to a zero-sum dynamic, which means that when there are multiple sources of aquatic species, promoting the development of one may suppress the others.

Figure 6.

Aquaculture and capture fishery production. (a) Aquaculture production of China; (b) aquaculture production of Vietnam; (c) aquaculture production of India; (d) capture fishery production of the three countries.

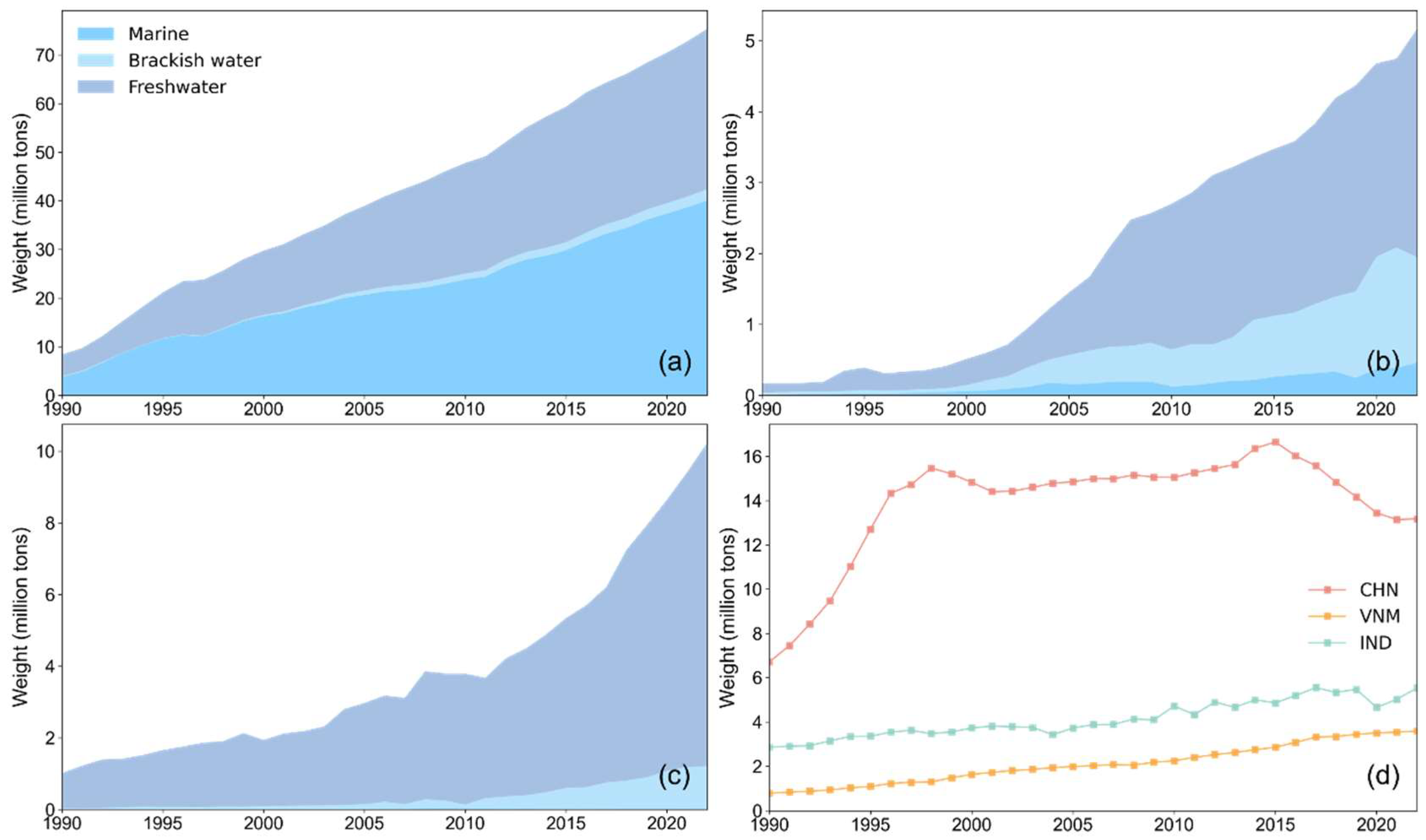

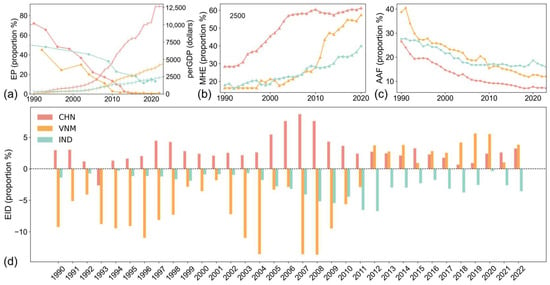

3.2.2. Economic Development

As shown in Figure 7, the study highlights substantial disparities in economic progress among the three countries since the 1990s. China has made the most significant advancements in poverty reduction, reducing the proportion of people living in extreme poverty (below $2.15/day) to zero by 2017. Vietnam also achieved substantial progress, with poverty rates falling below 1%. In comparison, India continues to face a higher poverty rate of approximately 12%. These differences correspond to variations in per capita GDP, with China’s per capita GDP being about three times that of Vietnam, while India’s GDP per capita is less than two-thirds that of Vietnam (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Economic and industrial development. (a) Share of population in extreme poverty and GDP per capita; (b) share of medium- and high-tech manufactured exports in total manufactured exports; (c) agriculture, forestry, and fishing value added of GDP; (d) difference in the proportion of exports and imports of goods and services of GDP.

Industrial composition further illustrates these economic disparities. Medium- and high-tech manufactured exports (Figure 7b) account for more than 50% of total exports in both China and Vietnam, reflecting significant investments in high-value-added industries. By contrast, India lags behind, with medium- and high-tech exports contributing less than 40% of its total exports. The share of primary industry in GDP (Figure 7c) also indicates that China and Vietnam have made greater progress in developing secondary and tertiary industries with higher added value, whereas India remains more reliant on primary industries. Trade balance, obtained by the difference in the proportion of exports and imports of goods and services of GDP, as shown in Figure 7d, reinforces these trends. Both China and Vietnam exhibit trade surpluses, where exports consistently exceed imports [42]. While the two are experiencing booming foreign economies, the relatively high perGDP and MHE and low EP and AAF also promote a stable and positive development of their domestic economies. Overall, the economic development of China and Vietnam is more robust than that of India.

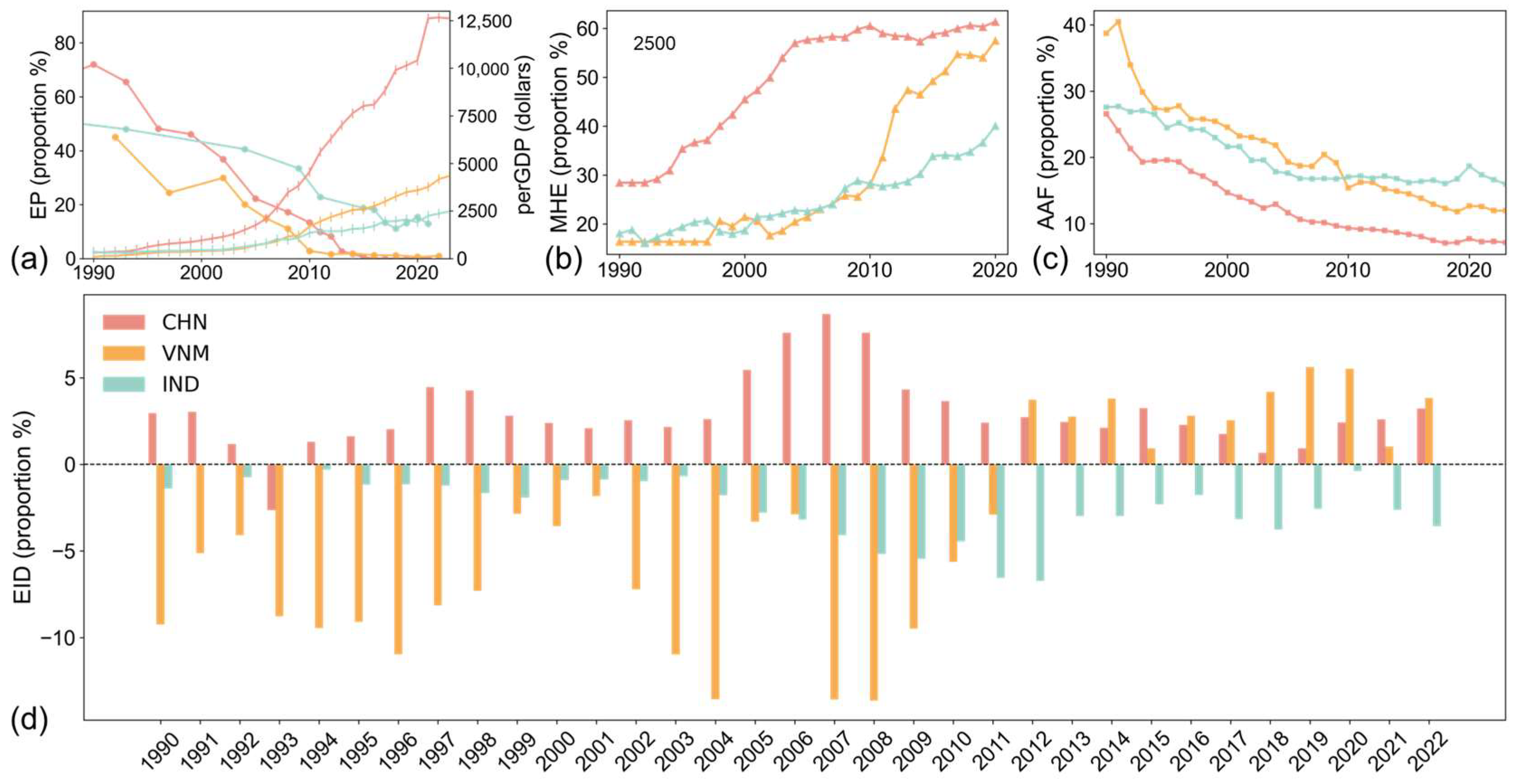

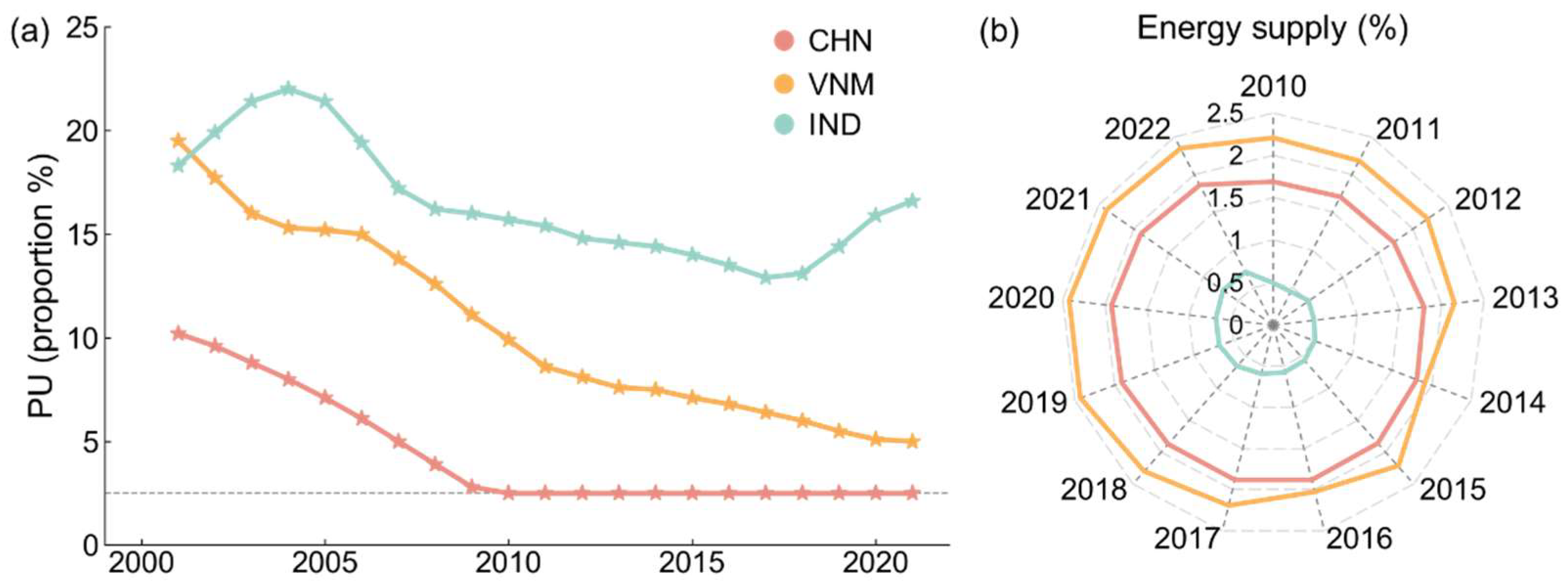

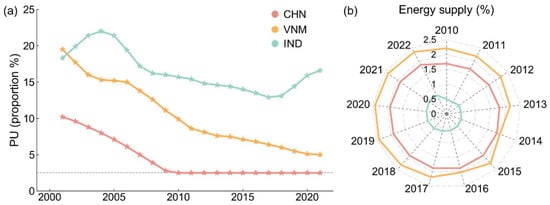

3.2.3. Nutritional Status and Dietary Energy Supply

We also studied nutritional structure, which is shown in Figure 8. People in undernourishment are those whose habitual food consumption is insufficient to provide the dietary energy levels that are required to maintain a normal active and healthy life, which can result from not eating enough or eating a diet that lacks nutrients. The prevalence of undernourishment in China has dropped to 2.5% (or even below 2.5%) and it has continued to decline in Vietnam, while India has shown an upward trend in recent years (Figure 8a). As shown in Figure 8b, Vietnam has the highest energy contribution from seafood in the daily diet compared to China and India, underscoring its role in improving national nutritional intake. Fish consumption provides bioavailable micronutrients and essential fatty acids that are often not readily available in terrestrial foods [43,44]. As a result, increasing fish production and consumption in Vietnam has significant nutritional benefits, while China maintains a moderate contribution and India is lagging behind. Overall, the dietary energy and nutrition supply in China and Vietnam are more abundant than in India, reinforcing the broader socio-economic findings.

Figure 8.

Nutritional structure. (a) Prevalence of undernourishment; (b) share of energy from fish and seafood in total food energy (actual consumption).

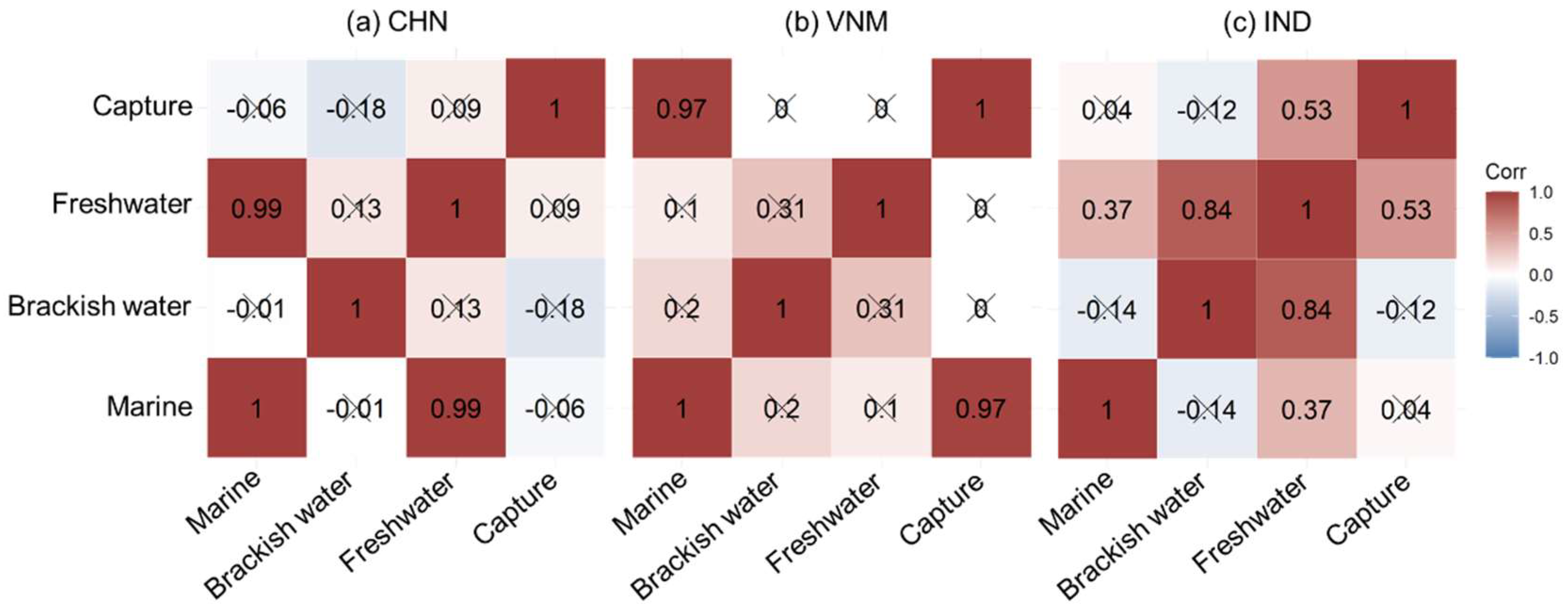

3.3. Correlation Between Fishery and Social Economy

In Table 2, we present the canonical correlation coefficients between fishery and social economy in the three countries under different combinations of socio-economic indicators. The calculation results combining the data of the three countries were represented as the CVI. All correlation coefficients exceeded 0.95 and passed the significance test (using the F-approximations of Shapiro–Wilk’s test statistics), indicating that the interaction of various factors in the economic development of a country played a crucial role in fishery production. Partial correlation analysis was applied to further explore the correlation. Table 3 shows the partial correlation coefficients of each factor. Given the redundancy in the full results, we focused on significant correlations that were consistent across all three countries to identify common patterns. Notably, some of the correlation coefficients were 1, which led to produced in significance tests. Results of partial correlation analysis show that perGDP and PopDensity were most strongly correlated with fishery production, followed by MHE. These findings emphasize the links between fishery production and key aspects of national economy, population density, and industrial structure, particularly the development of medium- and high-tech industries.

Table 2.

Canonical correlation coefficients between fishery and social economy.

Table 3.

Partial correlation coefficients between fishery and social economy.

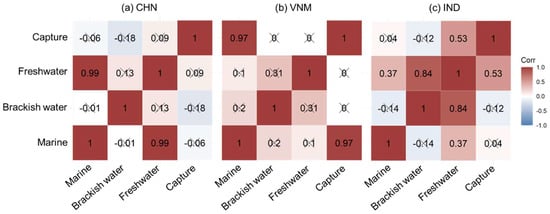

The correlation among different fishery production sectors was quantitatively explored, and the results are shown in Figure 9. In China, mariculture and freshwater aquaculture—which dominate fishery production—exhibited a strong correlation. They respectively harness terrestrial and marine resources, exhibiting comparable trends of development despite disparities in their current levels of advancement. There was a significant correlation between marine aquaculture and capture fisheries in Vietnam, which might be related to the high proportion of energy supply from fish and seafood in the daily diet of Vietnamese people (Figure 8b). The two together contributed to the production of marine species in the country. India displayed correlations between freshwater aquaculture and the other three fishery production sectors, with the highest correlation observed between freshwater and brackish water aquaculture. Referring to Figure 6, freshwater aquaculture in India led to the development of other sectors of fishery production to meet the demand of aquatic products. Various fishery production sectors showed different correlations due to different national conditions, jointly contributing to the country’s food supply.

Figure 9.

Partial correlation coefficients among different fishery production sectors. “×” indicates insignificant correlation.

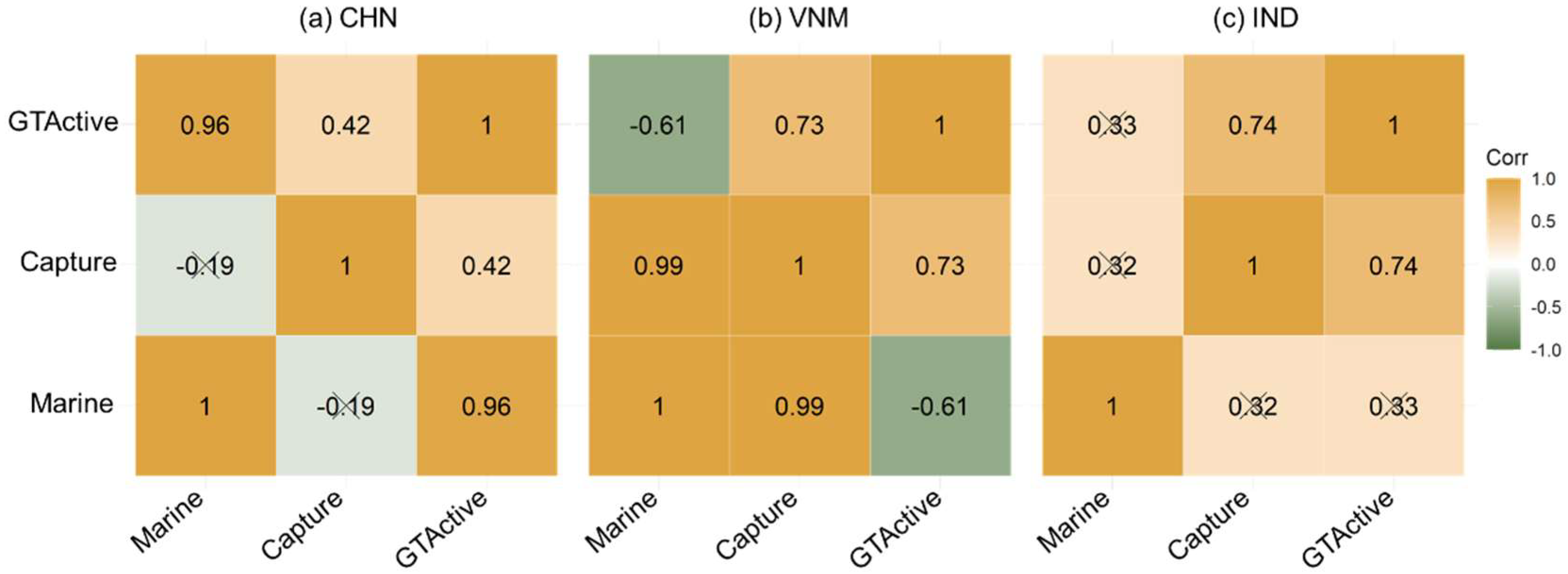

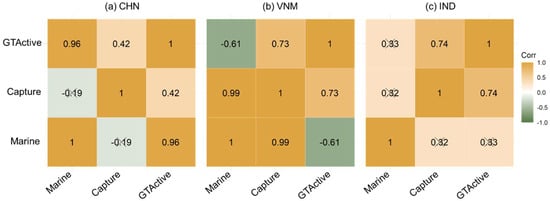

As a key tool needed for mariculture and capture fisheries, vessels influenced the development of both sectors. As shown in Figure 10, we studied the partial correlation among mariculture, capture and GTActive. In China, GTActive exhibited the highest correlation with marine aquaculture, followed by capture. The main source of China’s marine species production was marine aquaculture, which was consistent with the result shown in Figure 6. Mariculture and capture showed a high correlation in Vietnam (similarly to the result of Figure 9b). GTActive had a positive partial correlation with capture and a negative partial correlation with marine aquaculture. As shown in Figure 6, the mariculture production was less than one fifth of capture production, indicating that domestic vessels were more employed for the latter. When the focus of production is placed on capture, marine aquaculture receives less attention. Mariculture was scarce in India, and there was a significant partial correlation between GTActive and capture. Due to the different priorities of national fishery production, the application priorities of fishing vessels were different. The production of marine food and vessels were interdependent and correlated.

Figure 10.

Partial correlation coefficients among mariculture, capture and gross tonnage of active vessels. “×” indicates insignificant correlation.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to enhance understanding of the complex factors shaping mariculture development in China, Vietnam and India. By integrating comparative analyses of natural environments, socio-economic indicators, and fishery production systems, this research contributes valuable insights into the determinants of mariculture development.

4.1. Necessary Conditions for Mariculture

Darwin’s theory of biological evolution emphasizes that natural selection is the key mechanism of evolution, and organisms that adapt to nature can survive better [45]. The vigorous development of marine aquaculture relies on a suitable natural environment, including water depth, temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, etc., which are considered to be the necessary conditions for it. We conducted a comparative analysis of the natural environment within 50 km offshore marine areas of China, Vietnam, and India, attempting to determine whether India lacks the necessary conditions for mariculture.

Taking China as the reference, India and Vietnam shared similarities in temperature and seawater depth. Vietnam’s medium-level mariculture development ruled out inhibitory effects of these factors, suggesting that India also possesses suitable temperature and seawater depth for mariculture. Extremely low outliers of dissolved oxygen were observed in India, the minimum value of which was 5.06 mg/L. Ninety percent of the experiments conducted in a study reported median sublethal oxygen concentrations below 5 mg/L, which could cause declines in feeding and growth [46]. Water quality standard for fisheries published by the National Environmental Protection Administration of China states that the dissolved oxygen concentration in the aquaculture water area needs to be greater than 5 mg/L for more than 16 h in a continuous 24 h period. Obviously, the dissolved oxygen concentration in India was above the threshold, and thus marine aquaculture should not be restricted by this factor. Salinity levels presented regional variability. Some zones in India had high salinity values (>35), which were considered to affect the growth and survival of marine species [47,48]. Nonetheless, zones I8–I16 in India exhibited salinity within the suitable range, suggesting that these regions could still support mariculture. On the one hand, primary productivity indicated by chlorophyll is a food source for mollusks. On the other hand, high concentration values signify eutrophication of the water body, which is detrimental to the health of fish. For cage/pen fish culture in brackish water estuaries, a suitable level of chlorophyll concentration is lower than 25 g/L [8]. The optimal chlorophyll concentrations for shellfish [14] and Pacific oyster [16] aquaculture are >2g/L and 1–55g/L, respectively. The chlorophyll concentration in India was within an appropriate range and was unlikely to inhibit the development of marine aquaculture. Sea water velocity also demonstrated no discernible patterns in China and Vietnam, regions with advanced and moderately developed mariculture, respectively. A water current value higher than 0.1 m/s and lower than 2 m/s may be suitable for the growth of farmed species [16]. Although there was an outlier in zone I16 of India, it remained within the appropriate range.

Overall, India possesses the necessary conditions (suitable natural environment) for mariculture. Even though some zones have excessively low dissolved oxygen and high salinity values that are not conducive to the breeding of species, it is perplexing that mariculture is scarce in the other suitable zones, highlighting the need to explore socio-economic factors.

4.2. Sufficient Conditions of Mariculture

While natural conditions are necessary, socio-economic factors represent the sufficient conditions for mariculture development. This refers to two theories in economics: one is Mankiw’s Economic Principle 8, which states that a country’s standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services [49]; the other is that the nature of demand is to encourage industry mentioned in the book Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy. Seafood obtained from marine aquaculture as a commodity should also follow these two patterns. Namely, the industry of mariculture will flourish only when a country has the technology and capital to develop it, as well as the capacity to consume marine products.

Combining qualitative and quantitative analysis, we explored the relation between fishery production and social economy and analyzed the interrelationship between various sectors within the fishery industry. China’s economic development has always been at the forefront of the three countries, with Vietnam emerging as a latecomer and gradually surpassing India around 2010, showing an increasingly positive economic outlook. In comparison, India’s development lags behind, burdened by challenges of poverty and food insecurity (Figure 7 and Figure 8a). As shown in Table 4, we looked at the share of land used for agriculture, with India having the highest proportion at 60.05%. The large share of agriculture land represents India’s emphasis on food production. The country endeavors to ensure adequate food sources to meet people’s basic needs. In this context, hunger alleviation takes precedence over the pursuit of higher-nutrient foods [50,51] such as marine products. Meanwhile, in terms of fishery production in India, freshwater aquaculture accounts for the largest share, and the capture industry is also developing. The technological and funding requirements of these two sectors are relatively rudimentary, allowing for the same output with lower costs. Together, the lack of mariculture in India, which provides high-nutrient food and requires a higher technical and economic base, is interpretable.

Table 4.

Population and land area.

Further, marine product consumption in India is notably low. The energy supply from fish and seafood in the Indian diet is minimal (Figure 8b), reflecting a reliance on terrestrial food sources. The geographical connection between residents and the ocean may influence their demand for marine food [52]. Coastal populations constitute 40% of China’s total population [53,54], 80% of Vietnam’s [55] and 48% of India’s [56]. Meanwhile, Vietnam’s coastal zone area accounts for as much as 27.79% of the total area (Table 4); the close cultural and economic connection to marine resources also explain why Vietnamese people consume more marine products in their daily diet. India’s coastal population and area proportion fall between those of China and Vietnam, suggesting demand for marine products in theory. Nevertheless, there is a pronounced aquatic product trade deficit in India, with domestically produced aquatic food being extensively exported to global markets, forming an export-oriented production paradigm [57]. Under this circumstance, constrained domestic availability redirects consumers toward alternative protein sources, while comparatively low purchasing power further limits demand for higher-priced aquatic products. Together, these factors suppress per capita consumption of fish and seafood, thereby providing insufficient market stimulus to catalyze the expansion of marine aquaculture.

In summary, India’s relatively underdeveloped economic foundation, combined with low demand for marine products, represents a critical barrier to mariculture development. Even if a suitable natural environment is necessary, the development of mariculture in India has a long way to go due to the lack of socio-economic impetus, which is the sufficient condition.

4.3. Guiding Role of Policy

Policy plays a critical role in shaping the development of mariculture by aligning environmental, economic, and social priorities. China is the world’s largest producer of mariculture [7], whose vigorous development is inseparable from policy guidance and support. The On Relaxing the Policy and Accelerating the Development of the Fishery Industry policy enacted in 1985 formulated ten policy measures in terms of the decentralization of management authority, economic incentives, and technology promotion. It clarified the direction of national fishery development, ushering it into a fast-track growth phase. In recent years, policy documents such as the Outline of Long-term Goals for 2035 have shifted scale expansion to sustainable development, introducing mechanisms such as ecological red line zoning (restricting aquaculture in ecologically sensitive areas), green certification systems (linking eco-friendly practices to market access), and ecological compensation funds (supporting farmers in converting to low-impact aquaculture models). These mechanisms collectively realize the transition from “industry” to environment, people, and society in China’s mariculture governance and continue to ensure the steady progress of the modernization of China’s mariculture industry.

Similarly, the development of mariculture in Vietnam has also benefited from the government’s management policies [58,59]. These policies adopt a mix of licensing and resource-use regulation, community and cooperative support, and export promotion measures that have enabled rapid mariculture expansion while integrating it with rural livelihoods and regional development.

Despite the lack of mariculture, India ranked the second for the total production of aquatic animals, which was also supported by the government. For instance, the Coastal Aquaculture Authority Act (2005) regulated the activities connected with coastal aquaculture to protect the livelihood of various sections of people living in the coastal areas. Over the past decade, the government of India has also introduced some initiatives to boost mariculture research and development. The Draft National Mariculture Policy (NMP) prepared in 2018 proposed a spatial planning mechanism, introducing a multi-criteria decision-making framework based on satellite remote sensing data and GIS to identify suitable mariculture sites. The 2019 Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana (PMMSY) introduced financial and technical support measures to make all available facilities accessible to fishermen through various welfare schemes, which has played a significant role in promoting and supporting sea cage farming. The Coastal Aquaculture Authority (Amendment) Bill (2023) amending the Coastal Aquaculture Authority Act (2005) expands the scope of coastal aquaculture and leads it to prioritize industry growth. It is anticipated that further support and guidance from the government will facilitate the realization of India’s mariculture potential. Meanwhile, scholars have conducted a series of studies on aquaculture, providing reference for government management [60,61,62]. It is noteworthy that they frequently mentioned the significant potential for the development of mariculture in India and expressed optimism regarding its contribution to national food security [63,64,65]. These recommendations merit greater adoption and effective implementation.

The comparison of these policies reveals context-specific differences. China emphasizes top–down systematic planning driven by national strategies; Vietnam adopts market-oriented measures to link domestic production to global markets; and India focuses on bottom-up capacity building to overcome foundational constraints. This confirms that effective mariculture policy relies not just on policy existence but also on the combination and implementation of specific mechanisms (spatial planning and site selection, environmental impact assessment and monitoring, targeted incentives, and financial support). If policy frameworks can integrate explicit spatial planning and environmental protection measures with sustained technical support and market linkages, the development of mariculture is more likely to be productive and sustainable, whereas deficiencies in policy implementation or supervision mean that relying solely on policy statements is insufficient to ensure sustainable outcomes.

4.4. Limitations and Prospects

Through a multidimensional analysis of natural environmental, socio-economic and policy factors, this study provides new insights into the development of mariculture. The results indicate that mariculture is shaped jointly by natural environmental conditions and socio-economic factors, both of which form the necessary and sufficient conditions for its development. Moreover, national policies play a guiding role, which comprehensively consider environmental, economic, and social aspects to enhance public well-being. Nevertheless, several limitations remain in the current study, and future research could be expanded and refined in the following aspects.

First, there are inherent limitations in the data used and factors considered. On the data front, the relatively coarse granularity of temperature, dissolved oxygen, and salinity data might introduce potential biases, despite interpolation processing being performed. On the factor selection front, this study focused on several macro socio-economic variables, yet it paid insufficient attention to fine-grained factors including governance, economic subsidies, cultural customs, market structures and technological progress, which have also been proven to influence the development of mariculture [20,66,67]. More refined methods could be adopted to elucidate the correlations between these factors and mariculture development.

Second, environmental suitability was analyzed without distinguishing among specific species, despite substantial interspecific differences in environmental tolerance. Future studies could address this limitation by incorporating species-level analyses. In addition, some important environmental constraints were not explicitly considered, including tropical cyclones, storms, and harmful algal blooms. Even in regions where average environmental conditions are suitable, these factors may undermine the stability of mariculture.

Third, future research could develop various scenarios, such as policy investment, market demand, and climate change, to simulate the potential development trends of mariculture and quantify the impacts of key uncertain factors, thereby providing more targeted support for policy formulation. In such analyses, the negative environmental impacts associated with its excessive expansion should not be overlooked, as they may in turn constrain or undermine its long-term development.

5. Conclusions

This paper takes China, Vietnam, and India as cases to perform a multi-factor analysis on the development of mariculture. Initiating our study from the natural environment and combining the distribution of mariculture, we employed zonal statistics to examine the spatiotemporal differences in the marine environment from a holistic to a local scale. Incorporating time-series socio-economic data, we analyzed the correlation between mariculture and socio-economic conditions. In addition, the role of policy was discussed. Although parts of western India exhibit dissolved oxygen and salinity challenges, these do not significantly limit mariculture expansion across other suitable zones. Instead, India’s relatively lagging economic foundation and low demand for marine products constrain its development, underscoring that favorable environmental conditions alone are insufficient. The experiences of China and Vietnam demonstrate that strategic policy support and economic growth are critical for driving mariculture, ensuring its contributions to food security and sustainable development. In summary, the necessary natural environment and the sufficient social economy jointly influence the development of mariculture, wherein national policies exert a pivotal guiding influence. By aligning environmental suitability with socio-economic development, countries can unlock mariculture’s substantial potential to address food security and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Y., Y.L., X.Y., Z.W., V.L. and D.M.; Methodology, G.Y., Y.L., X.Y. and Z.W.; Software, G.Y. and Y.L.; Validation, G.Y., Y.L. and X.Y.; Formal analysis, G.Y., Y.L., X.Y., Z.W. and V.L.; Investigation, X.Y.; Resources, G.Y., Y.L. and X.Y.; Data curation, G.Y. and Y.L.; Writing—original draft, G.Y. and Y.L.; Writing—review & editing, G.Y., Y.L., X.Y., Z.W., V.L. and D.M.; Visualization, G.Y. and V.L.; Supervision, X.Y. and Z.W.; Project administration, X.Y. and Z.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.L., X.Y. and Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant No. 2024YFD2400300; the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences under Grant No. XDB0740300; the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 42306246; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 42371473.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Costello, C.; Cao, L.; Gelcich, S.; Cisneros-Mata, M.Á.; Free, C.M.; Froehlich, H.E.; Golden, C.D.; Ishimura, G.; Maier, J.; Macadam-Somer, I.; et al. The future of food from the sea. Nature 2020, 588, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockstroem, J.; Falkenmark, M.; Karlberg, L.; Hoff, H.; Rost, S.; Gerten, D. Future water availability for global food production: The potential of green water for increasing resilience to global change. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, 142–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Y. Resources for fish feed in future mariculture. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2011, 1, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellars, L.; Franks, B. How mariculture expansion is dewilding the ocean and its inhabitants. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, P.; Zhang, W.; Belton, B.; Little, D.C. Misunderstandings, myths and mantras in aquaculture: Its contribution to world food supplies has been systematically over reported. Mar. Policy 2019, 106, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.M.; Cabral, R.B.; Froehlich, H.E.; Battista, W.; Ojea, E.; O’Reilly, E.; Palardy, J.E.; García Molinos, J.; Siegel, K.J.; Arnason, R.; et al. Expanding ocean food production under climate change. Nature 2022, 605, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: Blue Transformation in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi, M.; Thirumurthy, S.; Samynathan, M.; Kumararaja, P.; Muralidhar, M.; Vijayan, K.K. Multi-criteria based geospatial assessment to utilize brackishwater resources to enhance fish production. Aquaculture 2021, 537, 736528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, R.R.; Ruff, E.O.; Lester, S.E. Temporal patterns of adoption of mariculture innovation globally. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Marín Del Valle, T.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wei, J.; He, G.; Yang, W. Scenario analyses of mariculture expansion in Southeastern China using a coupled cellular automata and agent-based model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 204, 107508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radiarta, I.N.; Saitoh, S.-I.; Miyazono, A. GIS-based multi-criteria evaluation models for identifying suitable sites for Japanese scallop (Mizuhopecten yessoensis) aquaculture in Funka Bay, southwestern Hokkaido, Japan. Aquaculture 2008, 284, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Kim, W. Potential for offshore aquaculture development in North Korea: Focusing on Atlantic salmon farming. Mar. Policy 2020, 119, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, R.R.; Froehlich, H.E.; Grimm, D.; Kareiva, P.; Parke, M.; Rust, M.; Gaines, S.D.; Halpern, B.S. Mapping the global potential for marine aquaculture. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J. Selection of mariculture sites based on ecological zoning—Nantong, China. Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Takeshige, A.; Miyake, Y.; Kimura, S. Selection of suitable coastal aquaculture sites using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in Menai Strait, UK. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 165, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Ferreira, J.; Bricker, S.; DelValls, T.; Martín-Díaz, M.; Yáñez, E. Site selection for shellfish aquaculture by means of GIS and farm-scale models, with an emphasis on data-poor environments. Aquaculture 2011, 318, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, G.; Brugere, C.; Diedrich, A.; Ebeling, M.W.; Ferse, S.C.A.; Mikkelsen, E.; Pérez Agúndez, J.A.; Stead, S.M.; Stybel, N.; Troell, M. A revolution without people? Closing the people–policy gap in aquaculture development. Aquaculture 2015, 447, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.E.; Gentry, R.R.; Lemoine, H.R.; Froehlich, H.E.; Gardner, L.D.; Rennick, M.; Ruff, E.O.; Thompson, K.D. Diverse state-level marine aquaculture policy in the United States: Opportunities and barriers for industry development. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 890–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Terry, G.; Rajaratnam, S.; Pant, J. Socio-cultural dynamics shaping the potential of aquaculture to deliver development outcomes. Rev. Aquac. 2017, 9, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, G.; Rubino, M.C. The Political Economics of Marine Aquaculture in the United States. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2016, 24, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.M.; Alam, M.F.; Bose, M.L. Demand for aquaculture development: Perspectives from Bangladesh for improved planning. Rev. Aquac. 2010, 2, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Unibazo, J.; León, P.; Vásquez-Lavín, F.; Ponce, R.; Mansur, L.; Gelcich, S. Stakeholder perceptions of enhancement opportunities in the Chilean small and medium scale mussel aquaculture industry. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Mu, Y. Evaluation of green development in mariculture: The case of Chinese oyster aquaculture. Aquaculture 2023, 576, 739838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlock, T.M.; Asche, F.; Anderson, J.L.; Eggert, H.; Anderson, T.M.; Che, B.; Chávez, C.A.; Chu, J.; Chukwuone, N.; Dey, M.M.; et al. Environmental, economic, and social sustainability in aquaculture: The aquaculture performance indicators. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Meng, D.; Gao, K.; Zeng, X.; Yu, G. Mapping the fine spatial distribution of global offshore surface seawater mariculture using remote sensing big data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2402418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, R.; Fleming, A.; Fulton, E.; Nash, K.; Watson, R.; Blanchard, J. Considering Land-Sea Interactions and Trade-offs for Food and Biodiversity. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 24, 580–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J. Marine Cultivation Technology in China; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, M. Offshore Aquaculture in the United States: Economic Considerations; Implications & Opportunities NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS F/SPO-103; US Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Imsland, A.K.D.; Sunde, L.M.; Folkvord, A.; Stefansson, S.O. The interaction of temperature and fish size on growth of juvenile turbot. J. Fish Biol. 1996, 49, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.O.; Maguire, G.B.; Edwards, S.J.; Johns, D.R. Low dissolved oxygen reduces growth rate and oxygen consumption rate of juvenile greenlip abalone, Haliotis laevigata Donovan. Aquaculture 1999, 174, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyinlola, M.A.; Reygondeau, G.; Wabnitz, C.C.C.; Troell, M.; Cheung, W.W.L. Global estimation of areas with suitable environmental conditions for mariculture species. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzi, S.; Caramori, G.; Rossi, R.; De Leo, G.A. A GIS-based habitat suitability model for commercial yield estimation of Tapes philippinarum in a Mediterranean coastal lagoon (Sacca di Goro, Italy). Ecol. Model. 2006, 193, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.; Boss, E.; Weatherbee, R.; Thomas, A.C.; Brady, D.; Newell, C. Oyster Aquaculture Site Selection Using Landsat 8-Derived Sea Surface Temperature, Turbidity, and Chlorophyll a. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, D. A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly-spaced data. In Proceedings of the 1968 23rd ACM National Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–19 August 1968; pp. 517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Valenti, W.C.; Kimpara, J.M.; Preto, B.d.L.; Moraes-Valenti, P. Indicators of sustainability to assess aquaculture systems. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 88, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Meng, D.; Ding, K.; Gao, K.; et al. Changes in the spatial distribution of mariculture in China over the past 20 years. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 2377–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Yang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, G. Linkage between soil nutrient and microbial characteristic in an opencast mine, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andaryani, S.; Nourani, V.; Abbasnejad, H.; Koch, J.; Stisen, S.; Klöve, B.; Haghighi, A.T. Spatio-temporal analysis of climate and irrigated vegetation cover changes and their role in lake water level depletion using a pixel-based approach and canonical correlation analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, R.; Cao, W.; Liu, Y.; Lu, B. The impacts of landscape patterns spatio-temporal changes on land surface temperature from a multi-scale perspective: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divu, D.N.; Mojjada, S.K.; Pokkathappada, A.A.; Sukhdhane, K.; Menon, M.; Mojjada, R.K.; Tade, M.S.; Bhint, H.M.; Gopalakrishnan, A. Decision-making framework for identifying best suitable mariculture sites along north east coast of Arabian Sea, India: A preliminary GIS-MCE based modelling approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saupe, E.E.; Myers, C.E.; Townsend Peterson, A.; Soberón, J.; Singarayer, J.; Valdes, P.; Qiao, H. Spatio-temporal climate change contributes to latitudinal diversity gradients. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Choi, E.K. Profits and losses from currency intervention. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2013, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kawarazuka, N.; Béné, C. Linking small-scale fisheries and aquaculture to household nutritional security: An overview. Food Secur. 2010, 2, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.C.; Cohen, P.J.; Graham, N.A.J.; Nash, K.L.; Allison, E.H.; D’Lima, C.; Mills, D.J.; Roscher, M.; Thilsted, S.H.; Thorne-Lyman, A.L.; et al. Harnessing global fisheries to tackle micronutrient deficiencies. Nature 2019, 574, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C.R.; Wallace, A.R. On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection. J. Proc. Linn. Soc. Lond. Zool. 1858, 3, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquer-Sunyer, R.; Duarte, C.M. Thresholds of hypoxia for marine biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 15452–15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, R.L.; Burreson, E.M.; Baker, P.K. The decline of the Virginia Oyster fishery in Chesapeake Bay considerations for introduction of a non-endemic species, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793). J. Shellfish Res. 1991, 10, 379. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, M.; Hofmann, E.E.; Powell, E.N.; Klinck, J.M.; Kusaka, K. A population dynamics model for the Japanese oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture 1997, 149, 285–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N.G. Principles of Economics, 4th ed.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, P.; Araújo, R.; Lopes, F.; Ray, S. Nutrition and Food Literacy: Framing the Challenges to Health Communication. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, D.R.; Villinger, K.; König, L.M.; Ziesemer, K.; Schupp, H.T.; Renner, B. Healthy food choices are happy food choices: Evidence from a real life sample using smartphone based assessments. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Luan, W.; You, D.; Su, M.; Jin, X. Seafood availability and geographical distance: Evidence from Chinese seafood restaurants. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 225, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Marinello, F. Exploration of eco-environment and urbanization changes in coastal zones: A case study in China over the past 20 years. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 119, 106847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Bertness, M.D.; Bruno, J.F.; Li, B.; Chen, G.; Coverdale, T.C.; Altieri, A.H.; Bai, J.; Sun, T.; Pennings, S.C. Economic development and coastal ecosystem change in China. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliani, S.; Bellucci, L.G.; Nhon, D.H. The coast of Vietnam: Present status and future challenges for sustainable development. World Seas Environ. Eval. 2019, 2, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Khan, S. Coastal Resilience and Urbanization Challenges in India. In International Handbook of Disaster Research; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Marine Products Export Development Authority (MPEDA). Annual Report 2023–2024; Marine Products Export Development Authority (MPEDA), Ministry of Commerce & Industry Government of India: Kochi, India, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, A.T.N.; Speelman, S. Involving stakeholders to support sustainable development of the marine lobster aquaculture sector in Vietnam. Mar. Policy 2020, 113, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, Q.T.K.; Xuan, B.B.; Sandorf, E.D.; Phong, T.N.; Trung, L.C.; Hien, T.T. Willingness to adopt improved shrimp aquaculture practices in Vietnam. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2021, 25, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, M.; Kumaran, M.; Vijayakumar, S.; Duraisamy, M.; Anand, P.R.; Samynathan, M.; Thirumurthy, S.; Kabiraj, S.; Vasagam, K.P.K.; Panigrahi, A.; et al. Integration of land and water resources, environmental characteristics, and aquaculture policy regulations into site selection using GIS based spatial decision support system. Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, M.; Anand, P.R.; Kumar, J.A.; Ravisankar, T.; Paul, J.; Vasagam, K.P.K.; Vimala, D.D.; Raja, K.A. Is Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) farming in India is technically efficient?—A comprehensive study. Aquaculture 2017, 468, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiruba-Sankar, R.; Saravanan, K.; Haridas, H.; Praveenraj, J.; Biswas, U.; Sarkar, R. Policy framework and development strategy for freshwater aquaculture sector in the light of COVID-19 impact in Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, India. Aquaculture 2022, 548, 737596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutty, M. Aquaculture development in India from a global perspective. Curr. Sci. 1999, 76, 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lakra, W.; Gopalakrishnan, A. Blue revolution in India: Status and future perspectives. Indian J. Fish. 2021, 68, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divu, D.N.; Mojjada, S.K.; Sudhakaran, P.O.; Sundaram, S.L.P.; Menon, M.; Mojjada, R.K.; Tade, M.S.; Vishwambharan, V.S.; Shree, J.; Subramanian, A.; et al. Economic performance and marine policy implications of mud spiny lobster mariculture in Tropical Sea Cages, North-Eastern Arabian Sea, India: An empirical study in marine economics. Mar. Policy 2024, 161, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Engle, C.; Tucker, C. Factors Driving Aquaculture Technology Adoption. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2018, 49, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckensteiner, J.; Kaplan, D.; Scheld, A. Barriers to Eastern Oyster Aquaculture Expansion in Virginia. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.