Abstract

The Jordanian portion of the Jordan Valley serves as a critical geostrategic and agricultural corridor, yet it faces an existential threat from absolute water scarcity, climate change, and regional demographic pressures. This study provides an exhaustive qualitative analysis of water governance in the valley, drawing on national strategies, institutional archives, and longitudinal data from 2000 to 2025. The research evaluates the transition of the Jordan Valley Authority (JVA) from a centralized development agency toward a mature, tri-tier decentralization framework involving Water User Associations (WUAs). Despite these reforms, systemic challenges such as elite capture, non-revenue water (NRW) losses in the King Abdullah Canal (KAC), and the subsidies continue to hinder efficiency. The study applies the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem (WEFE) nexus framework to examine the interdependencies between energy-intensive pumping, the reuse of Treated Wastewater (TWW) for 98% in certain sectors, and the preservation of the Dead Sea ecosystem. Findings indicate that while land-use policies have preserved 371,000 dunums of agricultural land, approximately 71,000 dunums remain uncultivated due to water shortages. The manuscript identifies the Amman-Aqaba Water Conveyance Project (AAWA) and the 2030 Digital IT Roadmap as essential catalysts for long-term resilience. The paper concludes with adaptive governance recommendations aimed at reconciling national strategic priorities with localized operational efficiency.

1. Introduction

The Jordan Valley, a profound geological rift reaching the lowest point on the Earth’s surface, constitutes the agricultural heartland of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (Figure 1) [1]. Stretching from the Yarmouk River in the north to the Dead Sea in the south, this 5000 km2 region provides a unique microclimate that allows for year-round cultivation, particularly during the winter months when it supplies the majority of the nation’s fresh produce [1,2]. However, this vital corridor is currently the epicenter of a severe water crisis. Jordan is classified as the second-most water-scarce nation globally, with annual renewable freshwater availability dropping to approximately 61 cubic meters per capita, significantly below the international absolute scarcity threshold of 500 cubic meters [3,4]. This scarcity is not merely a product of the region’s semi-arid climate but is exacerbated by rapid population growth, climate-driven rainfall variability, and the geopolitical complexities of hosting over 1.3 million Syrian refugees [5,6].

Figure 1.

The Jordan Valley, located within the Jordan Rift Valley.

Water governance in the Jordan Valley is a complex tapestry of historical institutional mandates and modern reform efforts. Since the early 1970s, the Jordan Valley Authority (JVA) has exercised centralized control over the region’s hydraulic infrastructure and land distribution [1,7]. This state-led model was designed to foster rural development and ensure social stability among tribal communities, creating what scholars refer to as a “moral economy” of subsidized water and land [1,8]. However, as urban demand in Amman and the highland cities has surged, the JVA has been forced to reallocate significant volumes of freshwater, approximately 48 million cubic meters (MCM) annually away from agriculture to municipal use [1,9]. To compensate, the valley has become a global testbed for the large-scale reuse of treated wastewater (TWW), which now constitutes nearly 98% of the irrigation supply in the middle and southern segments of the valley [1,10].

The conceptual framework of the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem (WEFE) nexus is particularly salient in this context [11,12]. The nexus approach recognizes that interventions in one sector—such as increasing wastewater treatment—have profound ripple effects on food security (through irrigation), energy consumption (through pumping costs), and ecosystem health (through the management of the Dead Sea’s declining water levels) [11,13]. In the Jordan Valley, the energy-intensive process of moving water from the low-lying rift to the highlands represents one of the kingdom’s largest electricity consumers, while the resulting reliance on saline TWW for irrigation has led to 63% of the valley’s soils suffering from salinity buildup [14,15]. As the kingdom approaches 2026, the institutional landscape is undergoing a significant transformation under the USAID-funded Water Governance Activity (WGA), which concludes in August 2026 [16,17]. This project aims to finalize a tri-tier decentralization model that empowers local Water User Associations (WUAs) to manage operational delivery, thereby reducing the administrative burden on the JVA and improving technical efficiency [1,16]. This transition, however, is complicated by entrenched power structures, as local elites often exert disproportionate control over WUA decision-making, leading to inequities in water distribution [1,8]. Furthermore, non-revenue water (NRW) losses in the King Abdullah Canal (KAC)—estimated at up to 30%—reflect a combination of aging infrastructure and socio-political “theft” that the state has struggled to curtail [1,18] (Figure 2).

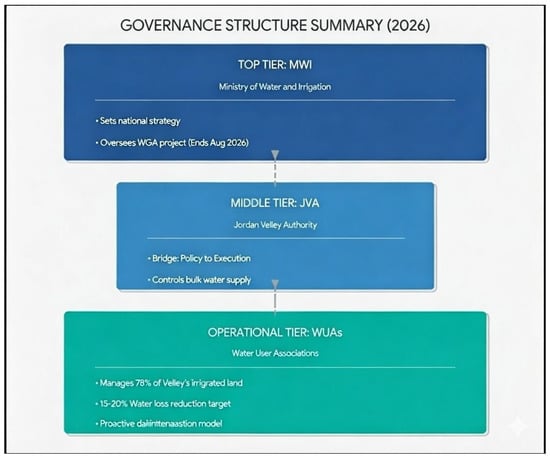

Figure 2.

Institutional governance framework for the Jordan Valley water sector (2026): The tri-tier structure.

This study provides an exhaustive examination of these governance dynamics. By synthesizing data from national water strategies, transboundary agreements like the 1994 Peace Treaty, and environmental impact assessments, the research seeks to identify pathways toward a more sustainable and equitable WEFE nexus in the Jordan Valley [3,19]. The analysis moves beyond technical solutions to explore the socio-political constraints on reform, evaluating how political priorities and regional stability influence water allocation [1,8]. Ultimately, the manuscript argues that achieving long-term resilience requires a fundamental shift toward adaptive governance that integrates local participation with large-scale infrastructure investments, such as the Amman-Aqaba Water Conveyance Project (AAWA), whose construction is planned to start in early 2026 [20,21].

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilizes a qualitative case study design, incorporating an extensive document review and longitudinal analysis of Jordan’s water sector policies and performance data from 2000 to 2025 [1,3]. The methodology is grounded in the WEFE nexus framework, which serves as the primary analytical lens for evaluating the interdependencies between water management, agricultural output, energy requirements, and environmental preservation in the Jordan Valley [11,12].

The primary data sources include official government publications from the Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI), the Jordan Valley Authority (JVA), and the Water Authority of Jordan (WAJ) [3,7]. Key strategic documents reviewed include the National Water Strategy 2023–2040, the JVA Strategic Plan 2024–2026, and the National Water Conservation Roadmap 2024 [3,22]. Additionally, the study incorporates transboundary legal frameworks, most notably the 1994 Treaty of Peace between the State of Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, to assess the reliability of international water transfers [19].

Quantitative indicators regarding water balance, agricultural production, and socio-economic trends were extracted from FAO AQUASTAT, the Department of Statistics (DOS), and the Jordan Response Plan for the Syria Crisis [5,8]. These datasets were used to construct comparative analyses of national versus valley-specific water usage [8]. The study also analyzed specific environmental research, such as the Ammari et al. (2013) study on soil salinity, to quantify the long-term ecological consequences of current irrigation practices [14].

The institutional analysis focused on the evolution of decentralized management. This involved tracing the development of Water User Associations (WUAs) from their inception in 2008 to the projected mature framework of 2026 [1,16]. Power dynamics within these associations were evaluated using literature on “elite capture” and the political economy of water in Jordan [1,8]. The transition toward a digitalized water sector was assessed through the IT Roadmap for the Water Sector in Jordan (2025–2030), which outlines the implementation of SCADA systems, AI-driven operations, and smart metering [23]. By reconciling these diverse data streams, the study provides a comprehensive overview of the Jordan Valley’s governance landscape. The qualitative reasoning is synthesized into a fluid narrative that accounts for the historical origins of institutional mandates, the mechanisms of current water allocation, and the future outlook for regional water security under varying climate and demographic scenarios [1,11] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Methodological framework of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Water Governance Institutions and Policies in the Jordan Valley

3.1.1. The Institutional Evolution: From Centralization to Tri-Tier Decentralization

The institutional framework governing water in the Jordan Valley is rooted in the 1973 establishment of the Jordan Valley Authority (JVA), an organization initially conceived as a multi-sectoral development agency [1,7]. Under the oversight of the Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI), the JVA’s mandate traditionally encompassed the construction of irrigation networks, the management of land leases, and the provision of essential social infrastructure [1]. However, the inefficiencies of this centralized approach became evident by the early 2000s, leading to donor-backed reforms that promoted participatory irrigation management and the establishment of Water User Associations (WUAs) [1,16]. This aligns with earlier evidence showing that water pricing and irrigation reform policies in the Jordan Valley often overestimate efficiency gains due to institutional, social, and political constraints [24]. These reforms laid the foundation for the current transition toward a tri-tier decentralization framework that redistributes operational responsibilities while retaining strategic oversight at the national level [1,16]. However, the inefficiencies of this top–down approach became apparent by the early 2000s, leading to donor-backed reforms aimed at introducing participatory irrigation management [1,16]. These early efforts culminated in the formal creation of Water User Associations (WUAs) in 2008, intended to devolve operational responsibilities to the farmers themselves [1]. As of 2025–2026, the sector is finalizing a mature “tri-tier decentralization framework,” a hierarchical structure designed to optimize the strengths of different administrative levels [1,16]:

- (a)

- National Strategy (MWI): The apex of the system, responsible for macro-level policy, legislative reform, and the management of large-scale infrastructure projects like the Amman-Aqaba Water Conveyance Project (AAWA) [3,20]. The MWI also coordinates with international donors to ensure financial sector stabilization [17].

- (b)

- Bulk Supply Management (JVA): Acts as the intermediary institutional bridge, retaining control over the King Abdullah Canal (KAC), primary reservoirs, and transboundary water allocations [1,7]. The JVA is also responsible for long-term land-use planning and the management of public agricultural leases [1].

- (c)

- Operational Execution (WUAs): The localized frontline, now managing roughly 78% of the valley’s irrigated acreage [1]. WUAs are tasked with water distribution at the tertiary level, canal maintenance, and the resolution of local disputes. This tier is expected to spearhead technical interventions to reduce non-revenue water (NRW) by 15–20% through proactive leak detection [1,18].

While this model provides a clear theoretical hierarchy, the reality on the ground is characterized by significant institutional inertia. The JVA continues to bear the financial burden of large-scale maintenance, as many WUAs remain financially unsustainable and dependent on government transfers [1,16]. Furthermore, the transition has been supported by the USAID WGA project, which provides the technical expertise required for this institutional shift [17].

3.1.2. Water Allocation Policies and the “Amman Reallocation”

Water allocation in the Jordan Valley is a high-stakes balancing act between the needs of 30,000 agricultural units and the municipal requirements of Jordan’s growing urban centers [1]. Historically, the majority of surface water from the Yarmouk and Jordan Rivers was dedicated to valley agriculture [1,19]. However, since the late 1990s, the MWI has implemented a systematic reallocation policy to meet the domestic needs of Amman and Irbid [1,9]. Currently, approximately 48 million cubic meters (MCM) of freshwater are pumped annually from the King Abdullah Canal to Amman [1]. This transfer represents a critical lifeline for the capital, which has seen its population nearly double due to natural growth and refugee inflows [5]. To maintain agricultural productivity in the valley, this freshwater is “substituted” with Treated Wastewater (TWW), primarily from the As-Samra treatment plant [1,10]. This strategy has fundamentally altered the valley’s water budget, as illustrated in the following Table 1:

Table 1.

National Aggregate vs. Jordan Valley Specific Water Balance (2021–2022).

This reallocation has profound implications for the valley’s WEFE nexus. While it secures urban drinking water, it forces farmers to rely on lower-quality water, leading to soil salinity challenges [14]. The National Water Strategy 2023–2040 aims to deepen this reliance on non-conventional sources, targeting an increase in TWW production to ~235 MCM by 2030 and potentially 300+ MCM by 2040 [3,10]. This transition is intended to achieve full urban–agricultural integration, where urban wastewater becomes the reliable fuel for the kingdom’s food basket [3,10].

3.2. Land Use, Agriculture, and Socio-Political Dynamics

3.2.1. The “Uncultivated Paradox” and Land Tenure

Land tenure in the Jordan Valley is characterized by a centralized leasing system managed by the JVA, which was designed to prevent the fragmentation of agricultural land through inheritance [1,7]. Arable land is leased in parcels of 3–5 hectares under strict long-term contracts [1]. This policy has been remarkably successful in preventing urban encroachment, which is a significant problem in the highland governorates [1]. However, a critical “uncultivated paradox” has emerged: of the 371,000 dunums of potentially irrigated land in the valley, approximately 71,000 dunums remain fallow [1,14]. This non-utilization is not due to a lack of interest from farmers but is a direct consequence of persistent water shortages and erratic freshwater delivery [1]. In the northern and middle Ghors, water quotas are often slashed during drought years, leaving thousands of dunums without the necessary irrigation to sustain high-value crops [1]. Consequently, the “preservation” of agricultural land in official policy is often a legal status rather than an operational reality [1]. Despite these constraints, the Jordan Valley remains the kingdom’s primary source of horticultural produce, contributing nearly all of the nation’s citrus and two-thirds of its fresh vegetables [1]. The output data of Table 2 reflects the valley’s dominance in the agricultural sector:

Table 2.

Jordan Valley Contribution to National Agricultural Output (2021).

The microclimate of the valley enables farmers to capitalize on winter markets in Europe and the Gulf, making the region a key driver of agricultural exports [1]. However, this intensive production is energy-dependent, requiring electricity for both groundwater pumping and the operation of drip irrigation systems, which are now ubiquitous in the valley [11,12].

3.2.2. Non-Revenue Water: Technical Failures and Socio-Political Safeguards

Non-revenue water (NRW) remains the single greatest technical and governance hurdle in the Jordan Valley [1,18]. In 2021, losses within the King Abdullah Canal (KAC) specifically were estimated at 19–30%, a volume of roughly 48 MCM [1]. This volume is equivalent to the entire municipal transfer to Amman, meaning that every cubic meter pumped to the capital is matched by a cubic meter lost to leakage or theft [1].

The composition of these losses reveals a deep-seated socio-political crisis. While physical seepage from aging, unlined sections of the canal accounts for ~40% of the loss, administrative losses (primarily “illegal withdrawals”) account for 57% [1]. This high rate of “theft” is not merely a criminal issue but is often a “survival strategy” for farmers receiving only 60% of their calculated crop water requirements [1,8] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Non-Revenue Water (NRW) Breakdown in the Jordan Valley (2021).

Enforcement against these illegal withdrawals is often inconsistent. The state’s reliance on tribal loyalty in the valley means that aggressive prosecution of water theft could trigger social unrest in a geopolitically sensitive border region [1,8]. This “moral economy” of water allows for a certain level of unauthorized use as a pressure-release valve for the region’s extreme scarcity [1,8].

3.3. Transboundary Context and Climate Pressures

3.3.1. Treaty Allotments vs. Actual Flows

The Jordan Valley’s water security is inextricably linked to its neighbors, Syria and Israel [19]. Under the 1994 Peace Treaty, Jordan is entitled to a base allocation of 50 MCM/year from Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee) and an agreed share of the Yarmouk River [19]. However, as regional water stress has intensified, Jordan has increasingly relied on “extra” water purchases from Israel, bringing actual delivery from Tiberias to nearly 100 MCM in some years [19]. Conversely, the Yarmouk River—once the valley’s primary freshwater source- has seen its flows decimated by upstream diversions and dam construction in Syria [19]. Historical flows that once reached several hundred MCM have dwindled to roughly 83–99 MCM [19]. This transboundary deficit is the primary driver of the valley’s reliance on treated wastewater [10] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Transboundary Water Allotments vs. Actual Receipts (Yarmouk and Jordan Rivers).

3.3.2. Climate Variability and Reservoir Depletion

Climate change has moved from a future projection to a current reality in the Jordan Valley [11,12]. Rainfall patterns have become increasingly erratic, with the 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 water years demonstrating extreme deviations from the Long-Term Average (LTA) [11]. These dry years have led to the critical depletion of Jordan’s 13 main dams, which serve as the primary storage for valley irrigation [11] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Rainfall Performance and Dam Utilization (2020–2022).

A major challenge for dam management is siltation. Approximately 27% of the original storage capacity in 4 out of the 16 main dams has been lost to sediment accumulation [25]. This reduces the JVA’s ability to “buffer” against seasonal drought, making the irrigation system increasingly vulnerable to the immediate impacts of a dry winter [11].

3.4. The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Regional Water Demand

The demographic shock of the Syrian refugee crisis has fundamentally reshaped the water demand profile in the northern Jordan Valley [5,6]. In governorates like Irbid and Mafraq, which share water resources with the valley, the population increase has driven a 40% surge in municipal water needs [5]. This has created a direct conflict with agricultural interests, as the MWI is often forced to prioritize domestic supply over irrigation during peak summer months [5]. Research into “refugee discourses” in Jordan shows that water scarcity is frequently portrayed in political narratives as an “external” problem caused by neighboring countries and refugees, rather than a structural issue of internal mismanagement [6]. However, data from the Jordan Response Plan (2018–2020) confirms that the infrastructure strain in the northern governorates—where refugees comprise over 50% of the population in some areas—is a primary driver of the national water deficit [5].

4. Discussion

4.1. Reconciling the WEFE Nexus in a Scarcity-Trapped System

The findings from the Jordan Valley demonstrate that water governance is not a siloed technical challenge but is the core of a delicate WEFE nexus [11,12]. The valley’s reliance on treated wastewater (TWW) for ~98% of irrigation in the central and southern regions is a masterclass in resource circularity, yet it comes with severe trade-offs [1,10]. The “substitution” of freshwater with TWW has allowed for the reallocation of 48 MCM to Amman, effectively trading soil health for urban survival [1,9].

Soil salinity now threatens the very sustainability of the “food basket.” With 63% of the valley’s soils showing signs of salinity, the lack of periodic freshwater flushing (due to treaty deficits and urban transfers) is leading to a slow-motion ecological crisis [14]. Addressing this requires a “Nexus-informed” land-use policy that matches crop selection with water quality, encouraging a shift away from salt-sensitive citrus toward salt-tolerant dates and modern greenhouse production [1,14].

4.2. Institutional Trust and the “Moral Economy” of Water

The transition to a tri-tier decentralization model by 2026 is an ambitious attempt to restore institutional trust [1,16]. However, the persistence of “elite capture” within WUAs suggests that decentralization without accountability can entrench local inequalities [1,8]. In regions where tribal hierarchies are strong, larger landowners often dominate WUA boards, ensuring that their parcels receive water even during shortages, while smallholders are left to dry [1,8].

Furthermore, the state’s tolerance of “desperation theft” (illegal KAC withdrawals) reflects the socio-political constraints of the Hashemite kingdom [1,8]. Because agriculture is viewed as a “social stabilizer,” the regime is hesitant to implement the aggressive enforcement required to reduce NRW to the targeted 25% by 2040 [3,18]. Moving forward, the state must replace this “moral economy” of patronage with a “technical economy” of efficiency, supported by the digital tools outlined in the 2030 IT Roadmap [23].

4.3. Large-Scale Infrastructure: The AAWA Project as a Paradigm Shift

The proposed Amman-Aqaba Water Conveyance Project (AAWA) represents the kingdom’s best hope for breaking its scarcity trap [20,21]. By providing 300 MCM/year of desalinated water from the Red Sea to Amman, the AAWA project would fundamentally decouple the capital’s survival from the Jordan Valley’s freshwater resources [20]. If municipal transfers to Amman were reduced or replaced by desalinated water, the JVA could potentially “re-fresh” the KAC with Yarmouk water, allowing for the soil leaching necessary to save the valley’s agricultural productivity [1,20].

However, the AAWA project’s multi-billion-dollar price tag and massive energy requirements create a new nexus challenge [20]. Powering the project will require a significant expansion of Jordan’s renewable energy portfolio, further intertwining the water and energy sectors [12,20]. Without this holistic nexus planning, the solution to the water crisis could inadvertently trigger an energy or financial crisis [11,20].

4.4. The 2030 IT Roadmap: Digitalizing the Operational Frontline

The IT Roadmap for the Water Sector (2025–2030) identifies digitalization as the key to reducing NRW and improving transparency [23]. By implementing unified SCADA architectures and enterprise GIS for spatial data management, the MWI and JVA aim to gain real-time visibility into the irrigation network [23]. For WUAs, smart metering at scale is essential for “accurate invoicing,” which currently accounts for a significant portion of administrative losses [1,23]. This “digital foundation” is not just about hardware; it is a strategic transformation intended to replace human discretion (and potential favoritism) with data-driven decision-making [23].

5. Policy Implications and Recommendations

5.1. Reforming Irrigation Management and WUA Empowerment

To move from “nominal” to “genuine” co-governance, the following reforms are essential [1,16]:

- (a)

- Capacity Building for WUAs: Projects must focus on the “train-the-trainer” approach to build sustainable internal capabilities in financial and technical management [17].

- (b)

- Legal Autonomy: Restructure groundwater extraction legislation and the JVA’s land-leasing bylaws to incentivize farmers who prioritize efficient water management [7].

- (c)

- Transparency Measures: Implement public, real-time reporting of water deliveries at the farm-unit level to expose “elite capture” and build trust between smallholders and the state [1].

5.2. Scaling Non-Conventional Water Resources

Jordan should continue its trajectory as a world leader in non-traditional water use [3,10]:

- Tertiary Treatment Expansion: Ensure that all decentralized wastewater plants are upgraded to tertiary treatment standards (JS 893/2022 [26]) to protect soil health and crop quality [10].

- Brackish Water Desalination: Expand the use of off-grid, solar-powered RO systems for Palestinian and Jordanian farmers in the valley to supplement dwindling groundwater sources [13].

- Rainwater Harvesting: Invest in the 620+ water harvesting sites currently in the desert pastoral areas to recharge valley aquifers and reduce the burden on the KAC [3].

5.3. Nexus-Informed Planning and Regional Diplomacy

Integrated Energy–Water Pumping: Synchronize water pumping schedules with renewable energy generation peaks to reduce the fiscal burden on the WAJ and JVA [11,12].

Transboundary Cooperation: Continue technical-level water diplomacy through the Joint Water Committee to ensure that treaty allocations from Lake Tiberias are maximized during drought years [19].

Food Security Re-Orientation: Support the transition from staples (wheat) to high-value horticulture in the valley, as Jordan already imports 98% of its grains, and the valley’s water is most efficiently used for crops that generate export revenue [1].

6. Conclusions

The Jordanian portion of the Jordan Valley stands at a crossroads. As the kingdom moves toward the 2026 tri-tier decentralization maturity, it is attempting to reconcile the “moral economy” of the past with the technical imperatives of an arid future [1,16]. This analysis confirms that water scarcity in the valley is as much a governance challenge as it is a hydrological one [1,8]. The persistent losses in the KAC and the 71,000 dunums of uncultivated land are symptoms of a system struggling to adapt to the overlapping shocks of climate change and regional conflict [11,14].

However, the pathways toward resilience are clearly delineated. The integration of the WEFE nexus provides a holistic framework for managing the trade-offs between urban drinking water and rural livelihoods [11,12]. Large-scale infrastructure projects like the AAWA conveyance and the 2030 Digital IT Roadmap offer a “techno-strategic” solution to the kingdom’s water deficit [20,23]. Ultimately, the Jordan Valley’s future depends on the state’s willingness to empower local associations, enforce water laws impartially, and invest in the non-conventional water resources that will serve as the region’s new lifeblood [3,10]. Addressing the valley’s needs is not just a sectoral priority but is the foundation of Jordan’s national stability in an increasingly volatile century [1].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology M.A.N., validation, A.A. and N.P.N. investigation, L.H. and S.A.; resources, R.A.-R.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.N.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; visualization, N.P.N.; supervision, A.A. and N.P.N.; project administration, A.A. and N.P.N.; funding acquisition, N.P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PRIMA, grant number 2234, PRIMA Call 2022 Section 1 NEXUS WEFE IA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAWA | Amman-Aqaba Water Conveyance Project |

| DOS | Department of Statistics |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| JVA | Jordan Valley Authority |

| KAC | King Abdullah Canal |

| LTA | Long-Term Average |

| MCM | Million Cubic Meters |

| MWI | Ministry of Water and Irrigation |

| NRW | Non-Revenue Water |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| TWW | Treated Wastewater |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| WAJ | Water Authority of Jordan |

| WEFE | Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem |

| WGA | Water Governance Activity |

| WUA | Water User Association |

References

- Chebaane, M.; USAID. Participatory Irrigation Management in the Jordan Valley: A Review of Institutional and Policy Reforms; USAID: Amman, Jordan, 2004.

- Ballard, S. Water Scarcity in the Jordan River Valley; Ballard Brief (Brigham Young University): Provo, UT, USA, 2021; Available online: https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/water-scarcity-in-the-jordan-river-valley (accessed on 15 January 2026).

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). National Water Strategy 2023–2040; MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2023.

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). Rainfall Season Report 2021–2022; MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2023.

- Government of Jordan. Jordan Response Plan for the Syria Crisis 2018–2020; Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation: Amman, Jordan, 2018.

- Hussein, H.; Natta, A.; Yehya, A.A.K.; Hamadna, B. Syrian Refugees, Water Scarcity, and Dynamic Policies: How Do the New Refugee Discourses Impact Water Governance Debates in Lebanon and Jordan? Water 2020, 12, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan Valley Authority (JVA). Strategic Vision for the Jordan Valley Authority, 2000–2020; JVA: Amman, Jordan, 2000.

- FAO AQUASTAT. Jordan Country Profile: Water Resources and Use; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). Annual Water Budget Reports 2001–2022; MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2022.

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). Wastewater Management and Reuse Policy; MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2023.

- Chemura, A.; Al-Smadi, W.; Abkar, A.; Sawwan, J.; Alananbeh, A.; Farhan, I.; Ghnaimat, A.; Alkhatatbeh, H.A.; Al Daraien, R.; Al-Qudah, T.; et al. Stakeholder perspectives on fostering the water-energy-food nexus in Jordan. Environ. Res. Food Syst. 2025, 2, 015009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Jordan Water Sector: Institutional Trust and Reform Pathways; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.A.; Baronian, M.; Burlace, L.; Davies, P.A.; Halasah, S.; Hind, M.; Hossain, A.; Lipchin, C.; Majali, A.; Mark, M.; et al. Off-grid desalination for irrigation in the Jordan Valley. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019, 168, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammari, T.G.; Tahhan, R.; Abubaker, S.; Al-Zu’bi, Y.; Tahboub, A.; Ta’Any, R.; Abu-Romman, S.; Al-Manaseer, N.; Stietiya, M.H. Soil Salinity Changes in the Jordan Valley Potentially Threaten Sustainable Irrigated Agriculture. Pedosphere 2013, 23, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Addous, M.; Bdour, M.; Alnaief, M.; Rabaiah, S.; Schweimanns, N. Water Resources in Jordan: A Review of Current Challenges and Future Opportunities. Water 2023, 15, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). Strategic Framework for Water Sector Decentralization: Transitioning to 2026; MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2024; pp. 12–15.

- USAID/MWI. USAID Water Governance Activity (WGA) Project Documentation; USAID/MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2021–2026.

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). Water Sector Institutional Set-Up Report (MWI/GTZ); MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2006.

- Haddadin, M.J. The Jordan River Basin 70 Years After the Johnston Plan. Water 2023, 15, 841. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). JVA Strategic Plan 2024–2026; JVA: Amman, Jordan, 2024.

- Attili, S. The Jordan River Basin 70 Years After the Johnston Plan. In Routledge Handbook of Water Diplomacy; Islam, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 729–742. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). National Water Conservation Roadmap 2024; MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2024.

- Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI). IT Roadmap for the Water Sector in Jordan (2025–2030); MWI: Amman, Jordan, 2025.

- Molle, F.; Venot, J.-P.; Hassan, Y. Irrigation in the Jordan Valley: Are water pricing policies overly optimistic? Agric. Water Manag. 2008, 95, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venot, J.-P.; Molle, F.; Courcier, R. Dealing with Closed Basins: The Case of the Lower Jordan River Basin; IWMI Research Report No. 127; International Water Management Institute: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- JS 893/2022; Water—Reclaimed Wastewater. JSMO: Amman, Jordan, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.