Abstract

As global value chains integrate firms operating under varied institutional contexts and distinct technological capabilities, the uniform adoption of green standards becomes challenging. A “one-size-fits-all” sustainability approach often fails to account for the voids faced by firms in different contexts participating in one value chain, particularly in developing economies an area where academic research remains limited and fragmented. This research gap is the motivation for the present study. Through a systematic review of 56 articles, this paper examines how technological gaps and institutional voids in global value chains (GVCs) affect firms’ capacity to leverage environmental performance across different national and organizational contexts. Building on this synthesis, we develop an integrative conceptual framework that elucidates these dynamics and offers actionable insights for managers seeking to navigate environmental performance in heterogeneous institutional and technological settings. Our findings contribute to the literature on sustainable GVCs and guide practitioners aiming to foster effective cross-border collaborations that enhance environmental performance.

1. Introduction

A global value chain (GVC) comprises multiple actors from countries with distinct technological and institutional characteristics. Consequently, environmental performance cannot be universally adopted or standardized across all participants. Barriers and facilitators therefore arise from institutional voids and technological gaps among firms operating in different countries within the same value chain. Institutional voids in emerging markets are defined as gaps in rules and norms between two or more countries, such as developing and developed markets, that can negatively affect environmental sustainability outcomes in GVCs [1]. On the other hand, technological gaps refer to differences in technological and innovation capabilities between firms or countries. Relative technological progress measures the distance between a country’s technology and the global technological frontier, effectively representing its technology gap [2].

Institutional voids in developing countries often make them destinations for high-industries due to weaker environmental regulations [3,4]. This creates significant environmental challenges, especially as GVCs grow in complexity, complicating the assessment of their impacts. While globalization’s environmental effects have been widely studied, the specific context of GVCs remains underexplored [5]. Key impacts include energy consumption, GHG emissions, carbon footprints, and maritime pollution [6].

Secondly, partnerships between developing and developed countries within GVCs can help mitigate the significant effects of the technology gap. Existing research has rarely explored how changes in the technology gap influence pollution [2]. Some studies indicate that technological progress can improve environmental performance by reducing energy consumption, shifting consumption patterns, and promoting cleaner, more efficient production methods [7]. Conversely, other studies highlight that technological advances cannot fully replace natural resource use and may simultaneously foster economic growth while increasing energy consumption and pollution emissions [2,8]. Therefore, technological progress has the potential both to enhance environmental performance and to heighten environmental risks [9,10]. However, these analyses generally focus on the absolute level of technological advancement, and no consensus has been reached on whether technological progress ultimately increases or decreases pollution [2].

Nevertheless, despite increasing academic interest in GVCs and environmental performance, research examining context-specific influencing factors, such as the impact of institutional voids on environmental performance across firms from different countries, remains fragmented and limited [1,11]. Although the technology gap has been recognized as a key determinant of energy and carbon intensity [12], there remains a notable scarcity of research examining its influence on the environmental performance of global value chains (GVCs). Existing studies indicate that narrowing the technology gap can substantially reduce GHG emissions, particularly in high-carbon industries, and that this effect may operate through improved GVC positioning [13]. Furthermore, the technological gap can indirectly affect pollution by shaping international trade dynamics, technological progress, and other structural factors influencing production-related emissions [2]. However, most studies have focused either on technological progress or trade effects in isolation, without integrating these mechanisms within the broader GVC framework [8]. Therefore, understanding how cross-country differences in technological capability and their relative distance from the global technology frontier shape environmental performance within GVCs remains a critical yet underexplored area of research [2,12].

To address this gap in the literature, it is important to note that although several studies have examined environmental upgrading, standards, and governance in GVCs, they have largely overlooked how institutional voids and technological gaps jointly influence environmental performance across developed and developing economies (see Table 1 and Table 2). Our study responds to this gap and sits at the intersection of trade, environment, and global value chains (GVCs), an area of high policy relevance. It provides an initial mapping of methodological approaches, industrial and geographic coverage, and proposes a conceptual model along with a forward-looking research agenda. The paper’s contribution is mainly based on offering a conceptual framework and an agenda-setting piece. Additionally, our paper inventories existing green GVC reviews (Table 1) and emphasizes how prior studies have largely neglected the combined effects of institutional voids and technological gaps (Table 2), providing a novel perspective compared to reviews that concentrate primarily on environmental upgrading, standards, or governance.

Table 1.

Major existing reviews on green GVCs.

Table 2.

Differentiation matrix.

Thus, there is a lack of a systematic review that synthesizes the dispersed body of knowledge on the interplay between institutional voids and technological gaps both at the national and firm levels and environmental performance within global value chains. To address this gap, the present study seeks to consolidate existing evidence, identify key patterns and methodological trends, and highlight the limitations of current research.

This research contributes to theory by integrating institutional theory and the resource-based view (RBV) to explain how institutional voids and technological gaps jointly shape environmental performance in global value chains. It advances existing perspectives by linking external institutional constraints with internal capability-based mechanisms, offering a multi-level understanding that connects firm and national dynamics. Building on these theories, it further develops an analytical and empirically testable framework driven by theoretical hypothesis development to guide future studies and provide an integrated understanding of how these factors jointly influence environmental outcomes across countries and industries. To consolidate existing knowledge and advance an integrated understanding of how institutional voids and technological gaps shape environmental performance in global value chains, the following research questions are posed:

Research Question 1: How have institutional voids and technological gaps been conceptualized and examined in the literature, and what patterns emerge from existing studies regarding their influence on environmental performance within global value chains?

Research Question 2: How do institutional voids and technological gaps interact to shape environmental performance, and what mediating, moderating, or bidirectional effects influence these relationships?

Based on the results of both the bibliometric analysis and the systematic review of interactions between institutional voids, technological gaps, and environmental performance, this study proposes a forward-looking research agenda. The findings highlight key theoretical gaps, underexplored contexts, and limitations in methodological approaches, which serve as the foundation for identifying priorities for future research. Specifically, the agenda outlines opportunities to advance theory by integrating multi-level perspectives, refine methodological approaches for studying GVCs, and guide empirical investigations that address the complex and context-dependent relationships identified in the literature.

The key results of this study highlight that the reluctance of firms in developing markets to achieve environmental performance is not merely a matter of unwillingness, but rather a consequence of structural constraints. These firms operate within environments shaped by economic pressures and institutional voids, such as weak regulatory frameworks, lack of incentives, and technological gaps, such as, the limited access to green technologies. Yet, despite these challenges, developing markets play a crucial role in global value chains by offering cost advantages in terms of labor, raw materials, and production. Therefore, they cannot be excluded from efforts to improve environmental performance along the chain. This research calls on managers and policymakers to design better coordination mechanisms between firms, ones that acknowledge and adapt to local realities instead of imposing uniform standards. A more context-sensitive approach is essential to foster inclusive and effective environmental performance across the entire chain.

Our research contributes significantly to the intersection of GVC research, sustainability, and the international business (IB) field by consolidating the fragmented empirical and conceptual research on the influence of institutional voids and technological gaps at country and firm level on the environmental performance of different firms embedded in GVCs.

2. Literature Review

The concept of the global value chain (GVC) emerged in the late 1990s. Porter first introduced the idea of the value chain within firms, later extending it to inter-firm linkages through the notion of a value system, which laid the groundwork for GVCs [4]. Building on this, Gereffi and Korzeniewicz developed the global commodity chain perspective, emphasizing globally dispersed yet integrated production networks [17]. Gereffi (1995) identified four key components input-output structure, regional distribution, governance, and institutional context forming the basis of today’s GVC concept [4,18,19]. The rise of international production has led to increased focus on GVC research and its implications for economies and industries. However, GVCs also pose complex and multifaceted environmental challenges across different sectors, including manufacturing [20,21], services [22,23], and transportation [24,25]. One significant concern is the influence of institutional voids; where developing countries may become destinations for high-pollution industries due to weaker environmental regulations [3,4].

This situation raises critical environmental challenges, especially as the complexity of GVCs increases, complicating the assessment of their environmental effects. Many studies tend to focus on globalization’s broader impact on the environment without addressing the specific context of GVCs [5]. Key environmental impacts include energy consumption, GHG emissions, carbon footprints, and maritime pollution [26,27,28]. In addition, a smaller technology gap reflects a stronger technical comparative advantage, enhancing a country’s position in the global economy [29]. It can encourage cleaner production practices and indirectly influence the nation’s environmental performance, a concept closely related to research on international trade and environmental pollution [2].

Despite these challenges, there is a growing trend among business actors within GVCs to address their environmental impacts. Increased consumer awareness, environmental campaigns, and regulatory pressures are prompting companies to evaluate and mitigate their activities and the environmental footprint of their suppliers [30]. These efforts include trying to reduce the environmental impacts associated with production and transportation, which are often geographically dispersed yet organizationally coordinated. Developing countries and emerging economies, positioned at various stages within GVCs, face significant disparities in economic benefits, technology access, and environmental costs. These nations often struggle to achieve environmental performance, particularly in areas such as energy conservation and emissions reduction [31]. While global environmental regulations are improving and there is increasing demand for cleaner production methods [32], creating universally applicable eco-friendly practices remains challenging due to the diverse economic contexts and operational realities of firms involved in GVCs.

As GVCs expand, they encounter significant environmental challenges that require urgent attention and action. Recent research has increasingly explored how specific actions within GVCs can mitigate environmental damage, including examining the broader socio-ecological context in which GVCs operate and considering the interactions between environmental upgrading process and value chain structures [33,34]. Despite growing scholarly attention to GVCs and environmental performance, studies examining how institutional voids and the technology gap between economies and firms affect environmental performance remain fragmented and limited [1,11].

Institutional voids refer to the absence or weakness of market-supporting institutions such as legal frameworks, regulatory bodies, information intermediaries, and financial markets, which are crucial for facilitating efficient exchanges and reducing transaction costs between firms [35,36]. Institutional voids are especially prevalent in emerging and developing markets, where multinational enterprises (MNEs) face institutional conditions that differ significantly from their home countries, complicating strategic planning and hindering sustainable competitive advantage [37]. Given the uneven development and diversity of institutions across emerging markets, institutional voids manifest in varied ways, requiring context-specific managerial approaches [38]. Under the conditions of an open economy, technological progress not only affects the environment through a series of domestic mechanisms but also leads to changes in the technology gap between the economy and the global technology frontier [2]. Therefore, there is a need to understand how institutional and technological voids shape the structural challenges firms face in developing markets and to design effective strategies in these complex environments.

3. Methodology

Systematic reviews involve a meticulous, transparent, and reproducible process aimed at identifying, selecting, evaluating, analyzing, and synthesizing research evidence on a particular topic [39,40]. Our review followed the five stages outlined by Tranfield et al. (2003) and widely utilized by other systematic studies: (1) Question formulation; (2) Locating studies; (3) Study selection and evaluation; (4) Analysis and synthesis; (5) Reporting the results [41]. Below, we provide a detailed account of each stage.

3.1. Question Formulation

The research design builds on an initial review of key debates across relevant research streams to ensure a solid foundation in the field. The study proceeds in two main stages, each corresponding to a research question discussed in the introduction. The first-stage methodology relies on a bibliometric analysis that maps how institutional voids and technological gaps have been conceptualized and examined in the literature, identifying dominant theories, methodological trends, geographical focus, and industrial contexts in relation to environmental performance within global value chains. The second-stage methodology employs a systematic content analysis to examine the interactions between institutional and technological factors and their influence on environmental outcomes, including potential mediating and moderating mechanisms. Drawing on insights from both analyses, the study concludes with a research agenda that highlights theoretical gaps, underexplored contexts, and methodological challenges, while suggesting directions to advance theory and empirical research on GVCs.

3.2. Locating Studies

3.2.1. Information Sources and Database Coverage

Given the novelty of the topic: the influence of institutional voids and technological gaps on environmental performance in global value chains we aimed for an exhaustive search. Initially, we consulted ABI/INFORM and Business Source Premier. However, after consulting with a research librarian, we determined that these databases alone were insufficient to capture the full body of relevant literature. Consequently, we included Web of Science as a complementary source to ensure coverage of additional relevant studies.

A comprehensive search string was developed collaboratively by the research team, using keywords related to GVCs and environmental issues (See Table 3). We initially extracted articles from Web of Science, EBSCO (Business Source Premier), and ProQuest (ABI/INFORM) using our search strings and compiled all results into a single Excel file. We then used Google Scholar for backward snowballing to check whether any additional peer-reviewed articles might have been missed. This search yielded 15 potentially relevant articles. For each of these, we compared the Google Scholar articles with our initial extraction file, which included all articles retrieved from the three primary databases. We found that all Google Scholar articles were already present in this file, confirming that our initial coverage was comprehensive.

Table 3.

Keywords string strategy.

No grey literature was considered, as our review focused exclusively on peer-reviewed journal articles. Therefore, Google Scholar was not included as a separate database in our review, since all relevant articles it identified were already captured in our extraction from Web of Science, Business Source Premier, and ABI/INFORM. Table 3 presents the full Boolean query for Web of Science (including wildcards, field limits, logic operators, extraction date, and counts per stage). The complete Boolean queries for EBSCO and ProQuest are provided in Tables S8 and S9, respectively. The extraction date was 7 November 2024. To ensure that no relevant studies published shortly after this date were missed, alerts were created in all three databases (Web of Science, EBSCO, and ProQuest). These alerts allowed us to identify any newly published articles that could be considered for inclusion before 31 December 2024.

3.2.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search string was developed collaboratively by the research team, using keywords related to GVCs and environmental issues. The title and topic fields were used with boolean operators to refine the results:

3.2.3. Search Saturation

To ensure search saturation, we employed several complementary strategies. Following the example of Dekkers et al. (2022), we began with an iterative search process, starting with an initial set of keywords and databases and gradually expanding both sources and terms [42]. At each stage, we recorded the number of relevant studies retrieved, noting that a decreasing yield indicated that saturation was approaching. When adding new databases or keywords produced very few additional studies, the search was considered saturated, meaning that most relevant research had been identified. Duplication of studies across sources was distinguished from true saturation. Finally, after analysis, we checked whether new studies generated novel insights; if they confirmed existing findings without providing major new discoveries, this strengthened the evidence without indicating incomplete saturation. Experts provided a list of seven articles to include; however, after cross-checking with our initial article extraction, we found that all the articles proposed by the experts had already been captured in the PRISMA reporting standard.

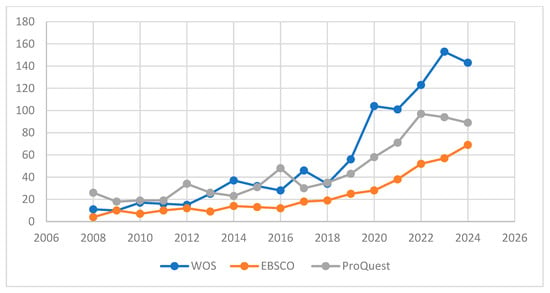

3.2.4. Timeline Justification

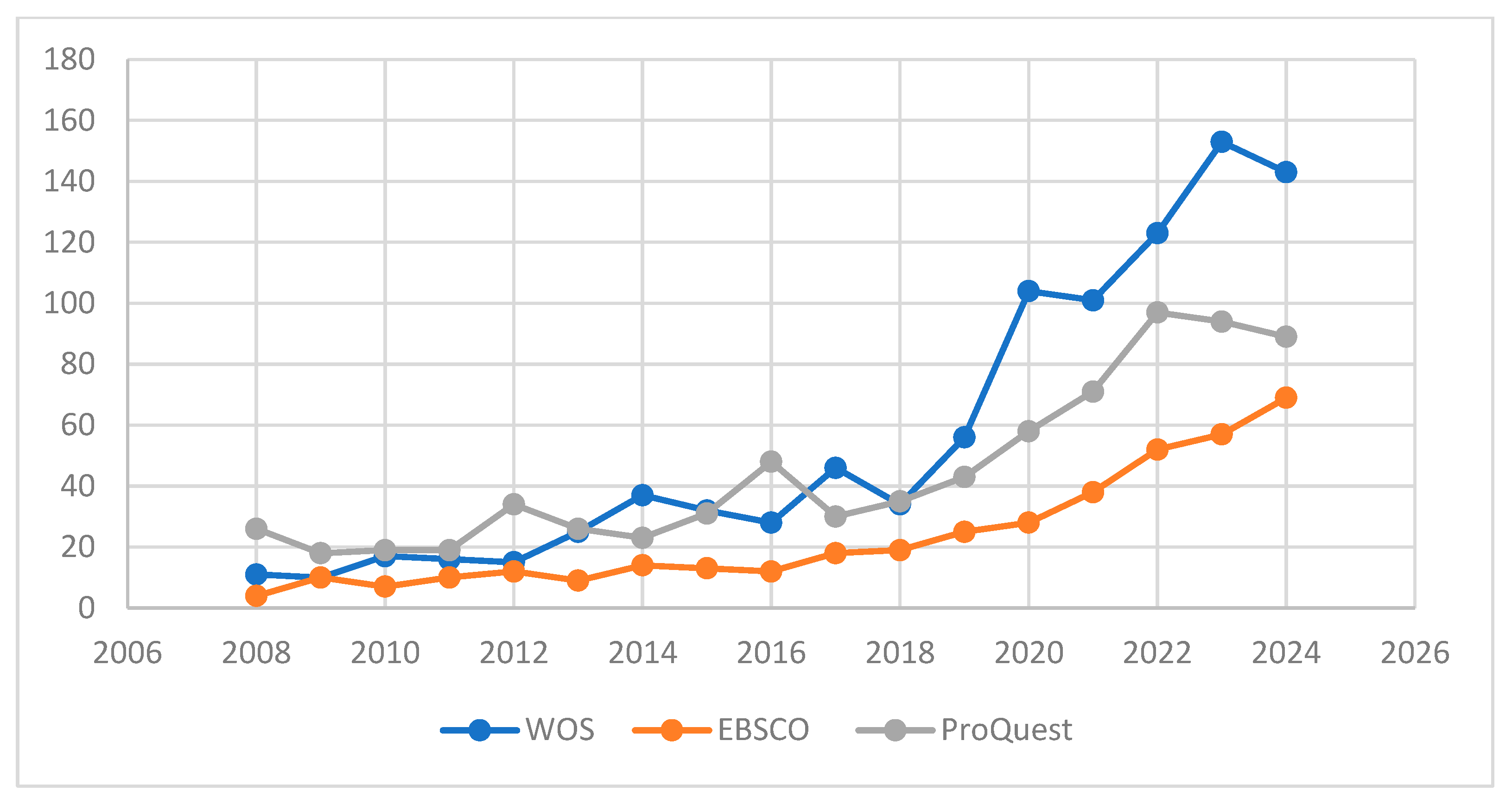

The search was limited to studies published between 1 January 2012, and 31 December 2024. To justify the selection of this period, we based our decision on three complementary arguments. First, we initially considered starting from 2008, the year when the United Nations published the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) report, which marked the emergence of global attention on environmental sustainability. This starting point reflects our intention to capture early developments in environmental performance in global value chains. Second, our choice was also informed by the publication trend on this topic. To verify the evolution of research interest, we applied our keyword search strings in Web of Science, EBSCO (Business Source Premier), and ProQuest (ABI/INFORM) for the period 2008–2024. The results show that between 2008 and 2011, the number of publications was very low across all databases, indicating limited scholarly attention (see Figure 1). Starting in 2012, there is a clear increase in publications across the three databases (see Figure S2), which continues steadily and accelerates in recent years (2020–2024).

Figure 1.

Overall publication frequency (2008–2024).

Additionally, we analyzed the publications between 2008 and 2011, and they largely did not meet our inclusion criteria, such as discussing the nexus between either institutional voids or the technology gap and environmental performance in GVCs. These statistics demonstrate that 2012 represents the point when research activity became substantive, justifying the choice of this year as the starting point.

Another key reason is the publication of a highly influential article in 2012 [43]. “Environmental Strategies, Upgrading and Competitive Advantage in Global Value Chains,” Business Strategy and the Environment. This article (cited over 500 times) investigates how firms implement green strategies to improve environmental performance while achieving economic benefits and competitiveness at both the firm and value chain levels [43]. It introduces the concept of environmental upgrading and provides empirical evidence directly aligned with one of our review objectives. The publication of this article marks a turning point in the literature, reinforcing the decision to start our review in 2012.

By selecting 2012–2024, our review captures the period of substantive scholarly activity, including seminal contributions and the steady growth of research on environmental performance within global value chains. This ensures that the review is both comprehensive and focused, while earlier publications (2008–2011) are scarce and largely outside the scope of our objectives.

3.3. Study Selection and Evaluation

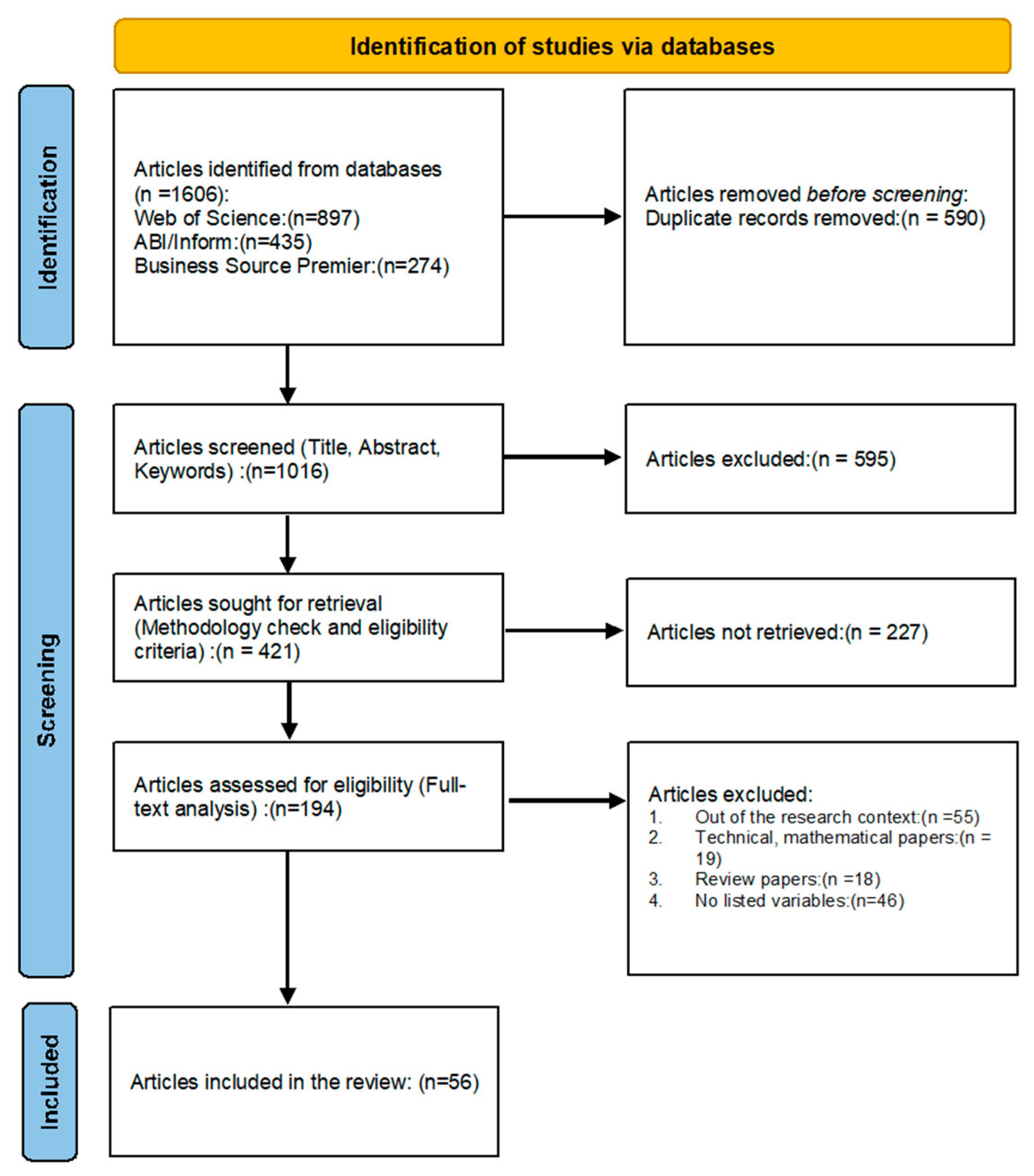

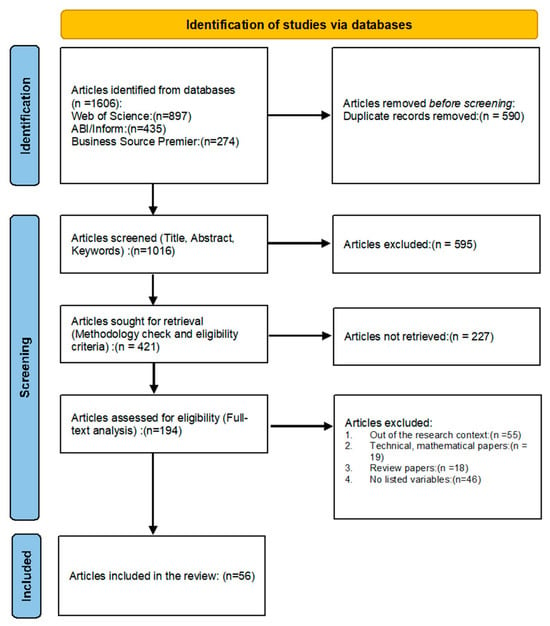

Table 4 present the PRISMA counts at each stage (hits → de-duped → screened → included), including exclusion reasons, which are also detailed in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Full selection and evaluation criteria.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow diagram (Source: By the authors).

Screening & Coding Reliability

Dual independent screening and manual coding were conducted by two researchers. Inter-coder reliability was assessed using Cohen’s κ; discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consensus. We provide below the kappa test results for each stage:

For Stage 1 (title, abstract, and keyword screening), 1016 articles were independently assessed by two reviewers. The Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was 0.90, indicating almost perfect agreement according to Landis and Koch [44]. The raw agreement was 95.1%, with 49 articles (4.8%) initially in disagreement, which were resolved through discussion (See Table 5).

Table 5.

Cohen’s κ stage 01.

For Stage 2 (methodology screening), 421 articles were independently assessed by two reviewers. The Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was 0.976, indicating almost perfect agreement [44]. The raw agreement was 98.8%, with 5 articles (1.2%) initially in disagreement. These discrepancies were carefully discussed by both reviewers, with each reviewer explaining the rationale behind their initial decision. Through this discussion, a consensus was reached for each article, ensuring that inclusion decisions were fully justified and aligned with the predefined eligibility and exclusion criteria (See Table 6).

Table 6.

Cohen’s κ stage 02.

For Stage 3 (final selection of included studies), 194 full-text articles were assessed. Initially, Reviewer 1 identified 56 articles for inclusion, while Reviewer 2 suggested 58 articles, adding two conceptual/theoretical papers on environmental performance in GVCs. These two additional papers were carefully reviewed and discussed by both reviewers and were ultimately excluded, as they were non-empirical and did not identify any independent, mediating, or moderating variables relevant to the nexus between environmental performance and GVCs. After consensus, 56 empirical studies were included in the final systematic review. This process demonstrates a rigorous and transparent approach to study selection, ensuring that all included studies are directly relevant and methodologically appropriate. The Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was 0.975, indicating almost perfect agreement [44]. The raw agreement was 98.9%, with only 2 articles (1.0%) initially in disagreement, resolved through consensus discussion. This demonstrates a rigorous and transparent approach to final study selection, ensuring that all included studies are methodologically appropriate and directly relevant to the research objectives (see Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Cohen’s κ stage 03.

Table 8.

Agreement and disagreement in the final selected studies.

In the final stage, the 56 included articles and all excluded studies were independently coded by two reviewers according to predefined exclusion categories (See Table S4). The inter-coder agreement was very high across all categories: 100% for included studies, 100% for articles with no listed determinants, 100% for articles not aligned with research objectives, and 100% for technical/mathematical modeling papers. For conceptual/theoretical/review articles, the agreement was 88.88%, with minor discrepancies discussed and resolved through consensus (See Table 8). This demonstrates that exclusion decisions were consistently and rigorously applied, supporting the reliability and transparency of the study selection process.

3.4. Analysis and Synthesis

3.4.1. Data Collection and Thematic Coding Procedure for Framework Building

To systematically organize the selected literature, we developed a structured Microsoft Excel database to record and analyze relevant data from each study. For each article, the database included descriptive and analytical fields such as bibliographic details, study design, country, industry, theoretical framework, variables with negative or bidirectional effects on green GVCs (see Table S1), variables with moderation, mediation, and control effects (see Table S2), and drivers of green GVCs (see Table S3). We applied a qualitative content analysis method to synthesize and interpret the data across the selected studies [42].

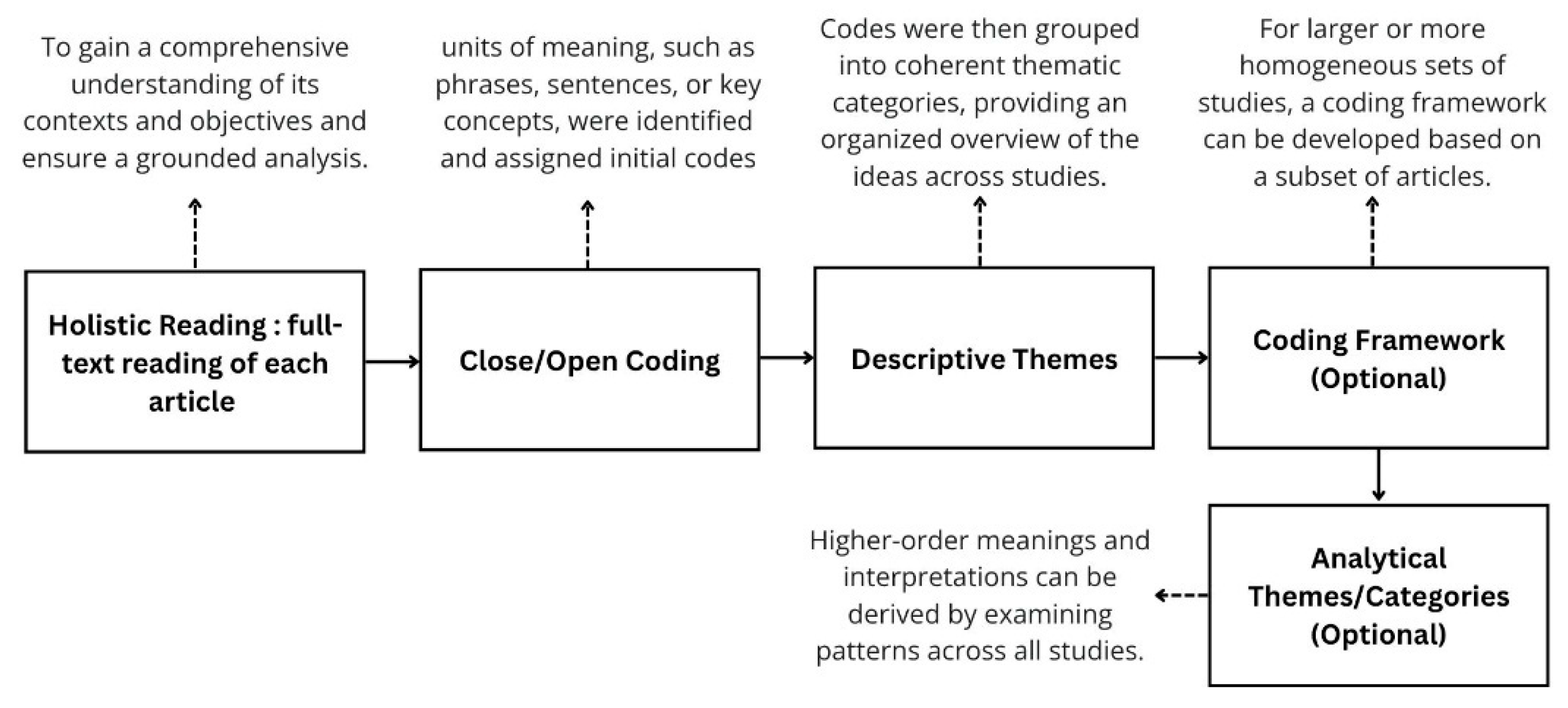

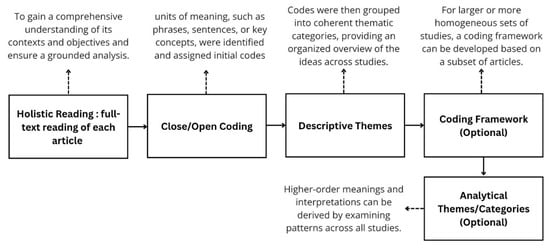

The thematic analysis followed a structured, step-by-step approach based on Bearman (2022) [45], as presented in Figure 3. In addition, the complete chain of evidence, from coding to final data extraction and synthesis, is presented in Tables S1–S3. This systematic and transparent process ensured a reproducible thematic analysis [42], enabling the identification of patterns and insights regarding the influence of institutional voids and technological gaps on environmental performance in global value chains.

Figure 3.

Five-step thematic analysis process.

3.4.2. Quality Assessment/Risk of Bias Evaluation

To assess methodological quality and risk of bias, a quality assessment matrix was developed based on predefined criteria (see Table 9 and Table 10). Each study was independently evaluated by two researchers, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion (See Table S6 for quantitative studies and Table S7 for qualitative studies). Green boxes indicate a high-quality tier, yellow boxes indicate a moderate level, and red boxes indicate a low-quality tier.

Table 9.

Quality appraisal and risk bias matrix for the qualitative studies (Credibility and transferability).

Table 10.

Quality appraisal and risk bias matrix for the quantitative studies (method, model specification quality, external validity, and treatment of endogeneity).

For qualitative studies, high-quality ratings were assigned to research designs demonstrating strong methodological rigor, data triangulation, and empirical credibility. These studies relied on extensive qualitative evidence, often combining institutional analysis, stakeholder reports, and secondary sources to enhance reliability. Triangulation across multiple actors such as firms, suppliers, NGOs, and consumers strengthened the trustworthiness and depth of the findings. Examples include longitudinal case studies covering more than a decade of industry evolution, action research involving direct observation of firm-level governance practices, and comparative analyses across global contexts (e.g., European, North American, and African value chains). In these cases, the integration of diverse data sources (e.g., interviews, official statistics, field observations, and organizational reports) ensured methodological robustness and enhanced internal validity. Collectively, these studies provided detailed and contextually grounded insights into sustainability and governance mechanisms within global value chains, warranting their classification as high quality.

Others were highly context-specific particularly those focused solely on China making their conclusions less generalizable to other economies. In some cases, the strong regional focus on inter-regional trade, energy-intensive sectors, or carbon-intensive intermediate product flows further restricted the external validity of the findings.

Studies rated as moderate quality displayed solid methodological grounding but with contextual or conceptual limitations that constrained the breadth or generalizability of their findings. These works often offered valuable insights within specific value chains such as the canned tuna industry, biofuel production, or local agri-food clusters yet their conclusions remained highly context-dependent. In several cases, the narrow geographical or sectoral focus limited transferability to other industries or institutional settings. Low-quality studies had narrow focus, limited analytical depth, or insufficient coverage of key sustainability aspects, reducing the robustness and transferability of their conclusions.

For quantitative studies, the quality and risk of bias were assessed based on methodological rigor, data transparency, and robustness of statistical techniques. Articles rated as high quality typically employed advanced analytical frameworks, such as input–output models, Pareto sensitivity analyses, or multi-criteria methods, combined with decomposition or econometric techniques that accounted for industry heterogeneity and included relevant control variables (e.g., environmental regulation, R&D, FDI). These studies also demonstrated clear model specifications, robustness checks (e.g., alternative samples, two-stage least squares estimations), and extensive use of firm-, industry-, and year-fixed effects. Despite minor limitations—such as temporal restrictions or incomplete environmental data their methodological soundness justified a high-quality rating.

In contrast, articles rated as moderate relied on sound but less sophisticated approaches or faced notable data limitations that affected the generalizability of findings. Studies categorized as low quality exhibited unclear methodological designs, insufficient robustness testing, or a lack of transparency in data sources, increasing the risk of bias and reducing confidence in their conclusions.

Studies rated as moderate quality partially addressed key sources of bias. While they often relied on panel data methods and included robustness checks, potential omitted variable bias remained. Some used aggregated data (e.g., WIOTs) due to differences in sectoral classification or geographic coverage, potentially introducing inaccuracies. Others lacked firm-level controls related to performance or prior internationalization experience, or failed to conduct endogeneity tests despite including control variables.

Articles rated as low quality showed greater risks of bias due to unaddressed methodological limitations. Several studies failed to explicitly test or correct for endogeneity, reducing confidence in the causal interpretation of results.

4. Results

The results of this review are presented in two main sections. First, we provide a bibliometric analysis of the selected studies. Second, we present a thematic synthesis and framework development that addresses the second research question.

4.1. Results of the Bibliometric Analysis

The first-stage methodology relies on a bibliometric analysis to provide a structured, evidence-based overview of the research landscape rather than a purely descriptive account. Specifically, it identifies publication trends, methodological patterns, and the geographical distribution of studies addressing institutional voids and technological gaps in the context of green global value chains. Through this analysis, the study maps the evolution of research methods and empirical techniques employed in the field, highlighting the predominance of certain approaches and the relative neglect of others. It also reveals geographical skew, showing how scholarship has disproportionately focused on certain regions while underrepresenting others, thus pointing to promising avenues for future research. Beyond simple publication counts, the analysis develops a two-dimensional evidence map that cross-tabulates identification strategies (e.g., DiD, GMM, threshold, nonparametric, structural modeling, etc.) with the direction of results (promoting, hindering, ambiguous). This methodological mapping helps visualize the diversity and directionality of findings across studies. In addition, the bibliometric approach allows for the systematic extraction of key information, including the research methods employed, the dependent and independent variables, the level of analysis, the indicators used to measure green GVCs, and the direction of results (linear, non-linear, positive, negative, mixed, or conditional). Altogether, this stage provides a comprehensive empirical foundation that informs and justifies the subsequent content analysis.

4.1.1. Employed Methods

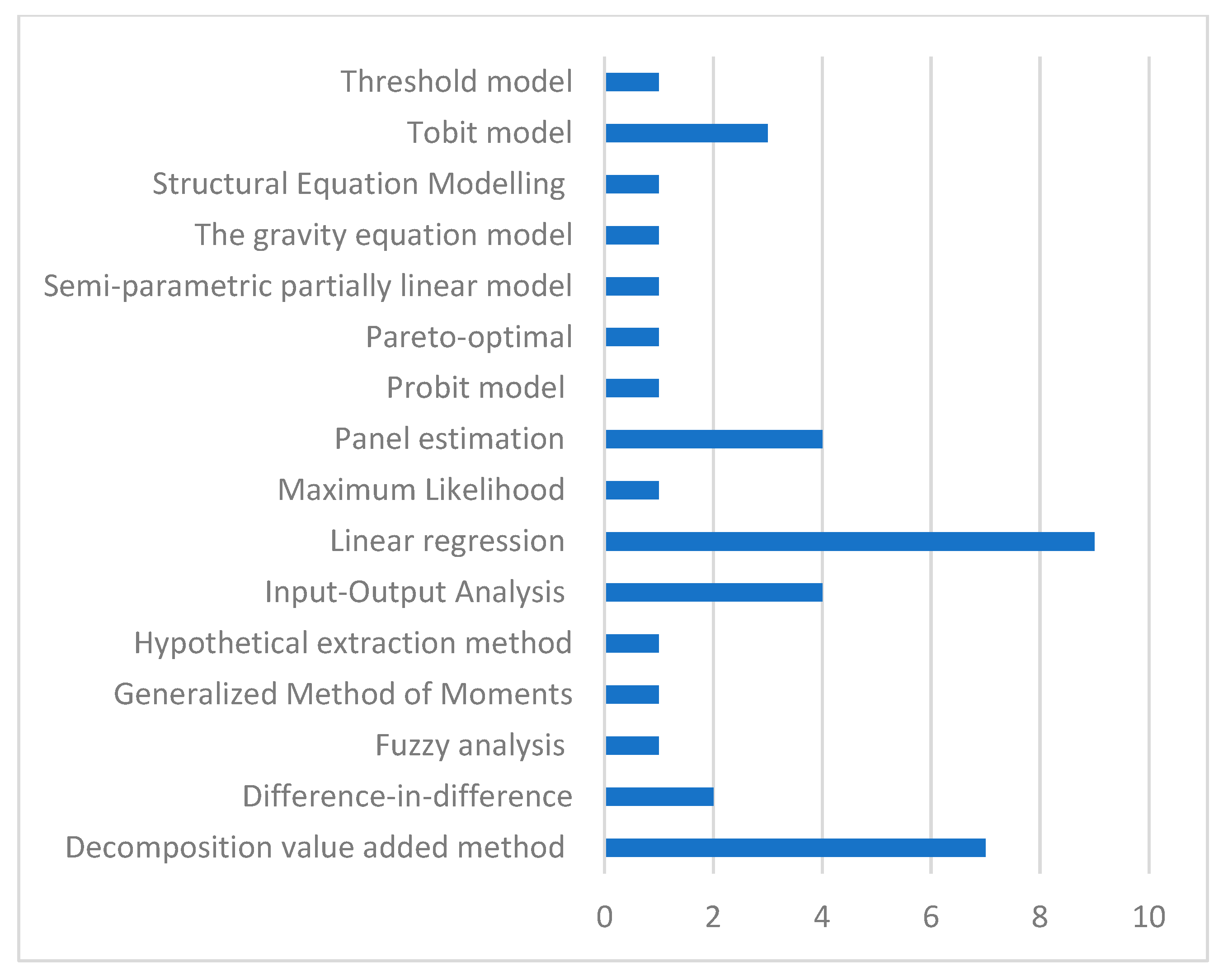

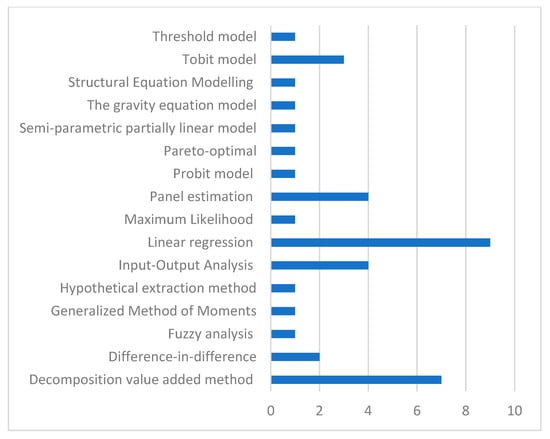

The dominance of quantitative studies reflects a methodological preference in the field. These studies employed a wide range of econometric and modeling techniques (Figure 4). The most frequently used methods included linear regression (n = 9), decomposition of value-added (n = 7), panel estimation (n = 4), and Tobit models (n = 3). Several less common but sophisticated approaches were also observed, such as the gravity equation model, generalized method of moments, and semi-parametric models.

Figure 4.

Quantitative used techniques.

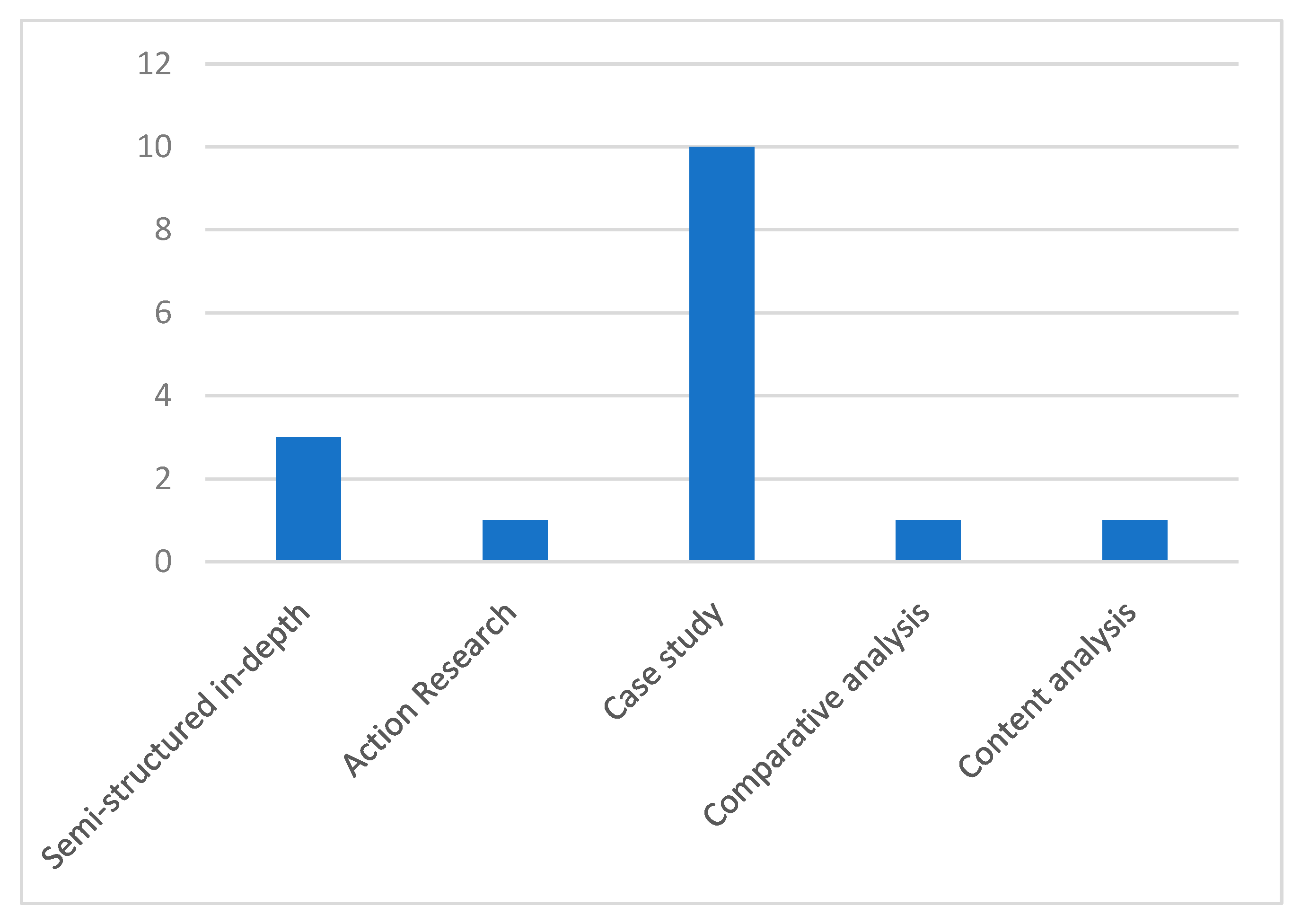

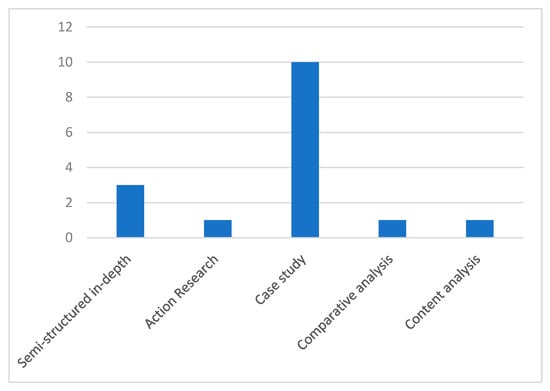

In contrast, qualitative research (Figure 5) relied primarily on case studies (n = 10) and semi-structured interviews (n = 3), with limited use of content analysis (n = 1) and action research (n = 1). While quantitative rigor is prevalent, the field could benefit from greater inclusion of exploratory and theory-building studies grounded in qualitative inquiry.

Figure 5.

Qualitative used methods.

4.1.2. Two-Dimensional Evidence Map of Identification Strategies and Outcomes

The evidence map illustrates how different identification strategies relate to observed outcomes on environmental performance and green GVCs (See Table 11). Methods such as linear regression, Difference-in-Differences (DiD), Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), Probit models, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), and the Gravity equation model generally report positive effects, indicating that these approaches often find the studied factors promote environmental improvements. In contrast, value-added decomposition, Input-Output analysis, and panel estimation frequently yield ambiguous results, reflecting context-dependent effects or mixed evidence. Some specialized methods, including Fuzzy analysis, Maximum Likelihood, semi-parametric models, and Threshold models, show mixed outcomes in single studies, while methods like Pareto optimal analysis and the Hypothetical Extraction Method appear only once and are inconclusive. Overall, the map suggests that traditional econometric methods tend to identify promoting effects more consistently, whereas structural or decomposition-based methods are more sensitive to context, highlighting the importance of method selection when interpreting environmental outcomes in GVC research.

Table 11.

Identification method and direction of results.

The journal studies have been published in the leading journals focused on sustainability and environmental management (Table 12). Notably, Sustainability, Journal of Cleaner Production, and Frontiers in Environmental Science emerged as the most frequent sources, reflecting their central role in advancing research on environmental performance, technological and institutional gaps, and sustainable practices within global value chains. This concentration underscores the importance of these journals as key platforms for disseminating knowledge in the field. Detailed journals are listed in Table S9.

Table 12.

Journals’ frequency.

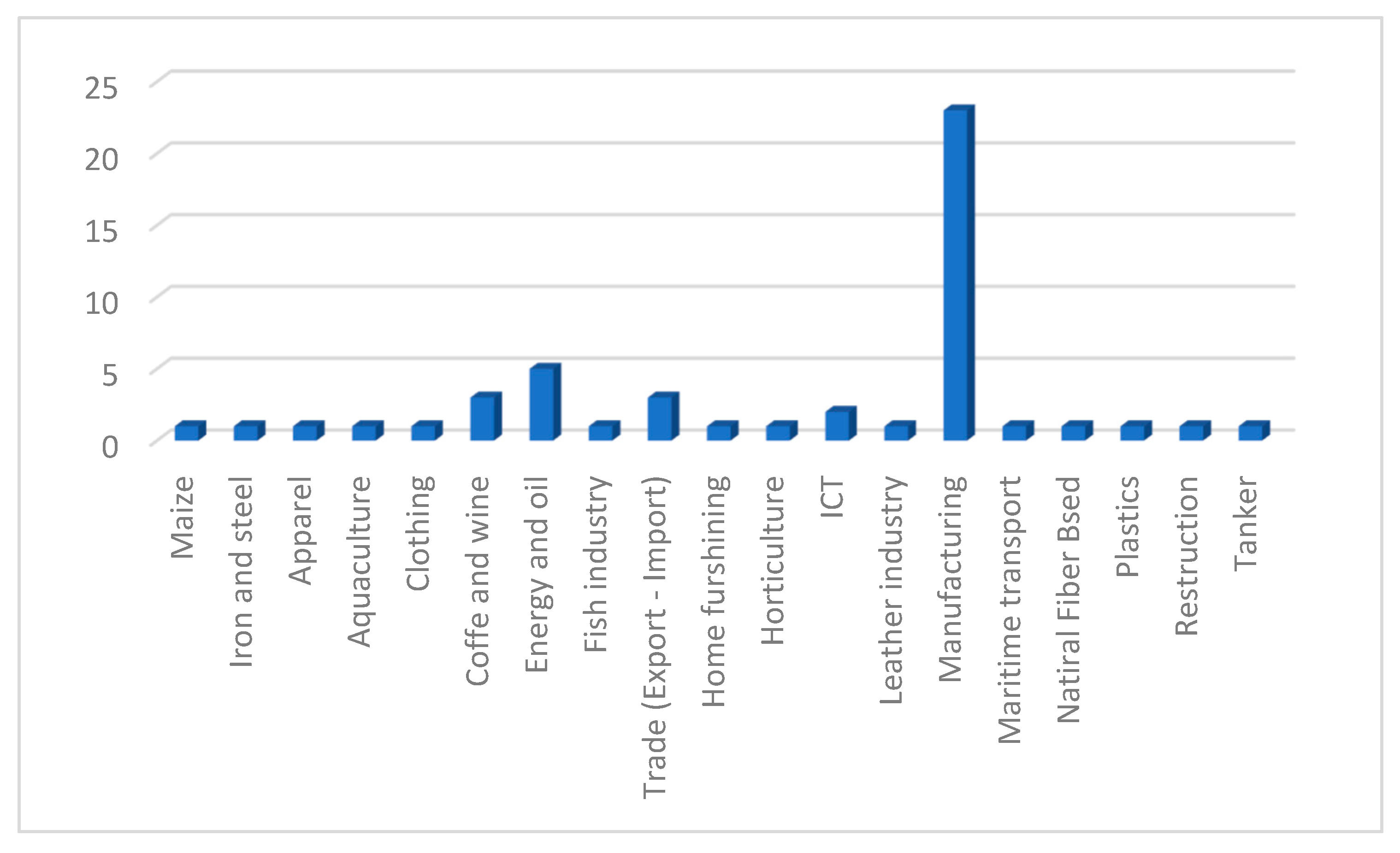

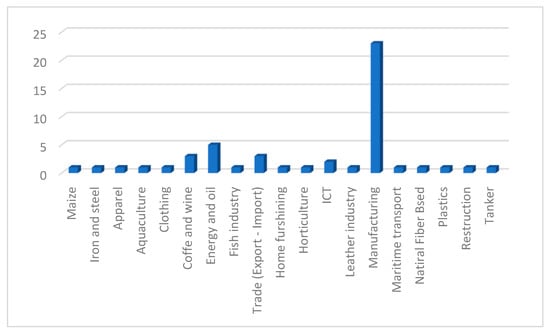

4.1.3. Industrial Sector and Geographical Skew

The literature also reflects a diverse but uneven distribution of industrial sectors studied. Manufacturing dominates the field, appearing in 23 articles (Figure 6). Other sectors receiving limited but notable attention include energy and oil (n = 5), coffee and wine (n = 3), and trade/export–import (n = 3). Several niche sectors, such as aquaculture, natural fiber, maritime transport, and ICT, were examined in only one or two articles. This narrow industrial focus suggests that our understanding of green transitions remains concentrated in traditional sectors, highlighting opportunities for research in emerging or service-based industries.

Figure 6.

Industries used for data collection.

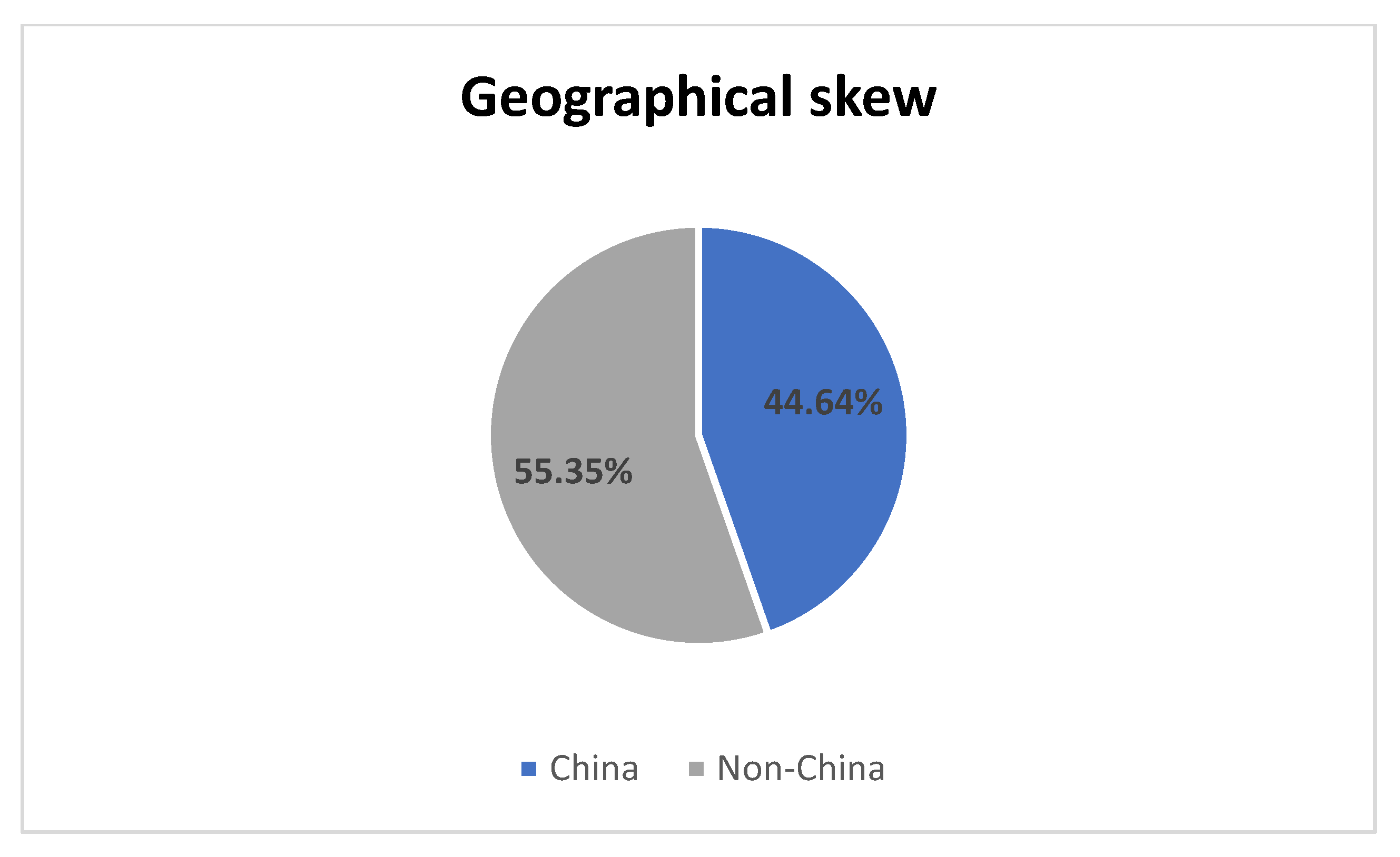

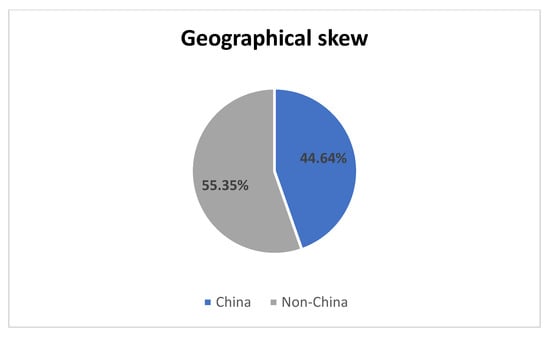

In terms of geographical coverage (Figure 7), research remains highly concentrated in a few regions. Notably, China emerged as the most studied context, with 25 of the 56 articles focusing on Chinese cases.

Figure 7.

Geographical skew.

Other developing and emerging economies were represented to a much lesser extent, including India (n = 2), Brazil (n = 1), Mexico (n = 1), and Russia (n = 1). African countries received very limited attention, with only isolated studies focusing on Kenya, Burkina Faso, and North Africa (see Figure S3 for detailed geographical distribution by region of the included studies). Overall, the literature exhibits a geographical imbalance that future research should address, particularly by examining underrepresented regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, and the Middle East. Consequently, external validity represents a central concern in this body of literature, given the heavy concentration of studies conducted in China (Figure 7). Although China provides a rich empirical context for examining the intersection of GVC participation, industrial upgrading, technology adoption, and environmental transformation, future research should expand comparative analyses across diverse institutional contexts. Such cross-country studies, particularly in underrepresented regions like Sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Latin America, would help determine whether the mechanisms identified in Chinese cases hold under varying levels of state capacity, market openness, and regulatory enforcement, thereby testing the robustness and transferability of current theoretical assumptions.

4.1.4. Theoretical Lens

Table 11 and Table 13 note that while empirical richness is often present, the lack of theoretical anchoring undermines cumulative knowledge-building and limits the generalizability of findings. It also hinders the ability to compare results across contexts, which is particularly important in GVC and environmental research, given the high institutional and industrial heterogeneity.

Table 13.

Theoretical lens.

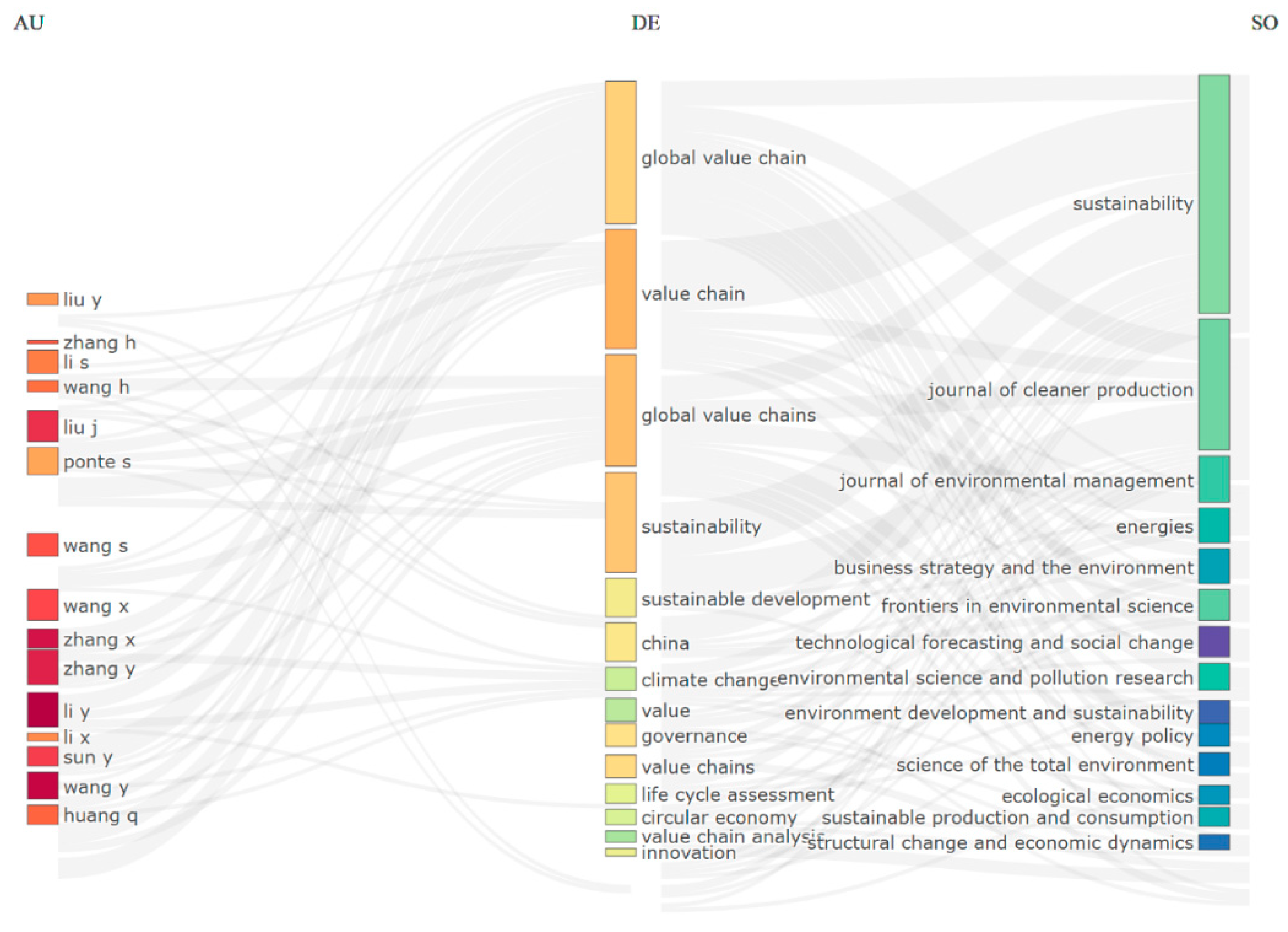

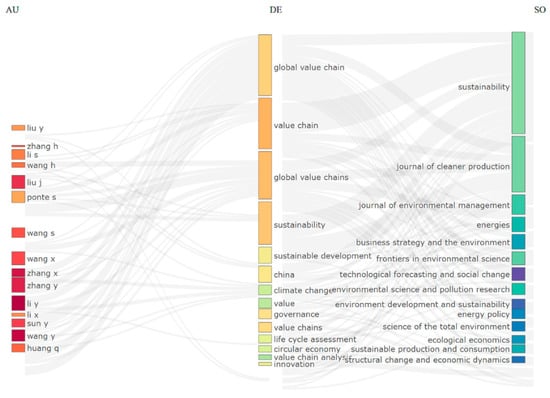

4.1.5. Three-Field Plot (Authors—Keywords—Sources)

The Three-Field Plot (Figure 8) was generated using biliometrix illustrates the relationships among the most prolific authors (AU), the most frequent keywords (DE), and the most relevant journals (SO) in the field. It shows that authors such as Liu Y, Zhang H, Li S, and Wang H are leading contributors to the literature, with a particular focus on themes like global value chains, value chains, and sustainability.

Figure 8.

Three field plot (Source: by the authors, Software: Bibliometrix 5.0).

These central keywords indicate that the field primarily addresses the environmental and strategic implications of global value chain structures. Additional keywords, including climate change, circular economy, life cycle assessment, and governance, reflect an interdisciplinary approach that integrates ecological, economic, and policy dimensions. The main publication outlets are Sustainability, Journal of Cleaner Production, and Journal of Environmental Management, indicating that the most influential work is published in journals specializing in environmental sciences, sustainable development, and business strategy. This visualization, therefore, provides a comprehensive overview of the intellectual structure of the field, linking the most active authors to key research topics and the journals shaping academic discourse. Multiple authors connect to the same keywords, indicating shared research interests or collaboration within thematic areas.

The flows indicate which topics dominate in which journals and highlight the primary outlets for specific research areas. Thicker flows show strong associations between authors, topics, and journals. For example, the “global value chain” keyword has strong connections to several authors and is published in high-frequency sources. Thin or isolated flows represent niche topics or emerging connections. Colors in the left field distinguish different authors, making it easier to trace their contributions across keywords and journals.

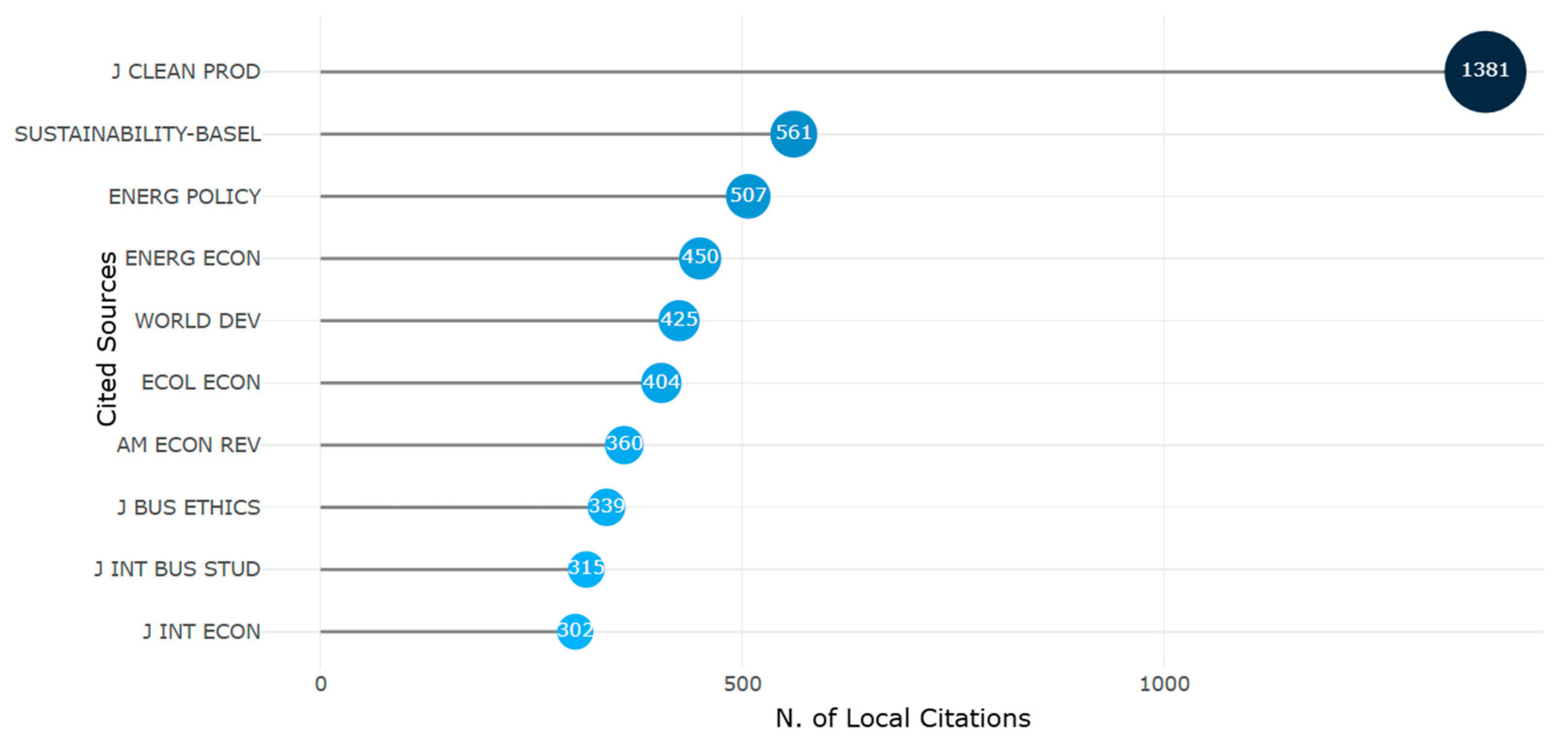

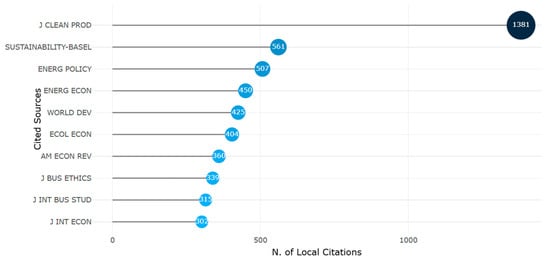

4.1.6. Most Local Cited Sources

The results shown in (Figure 9) highlight the most cited journals in the field of green GVCs. Journal of Cleaner Production leads with 1381 citations, underscoring its central role in sustainability and clean production research. Sustainability follows with 561 citations, while Energy Policy (507) and Energy Economics (450) are key outlets for studies on energy policy and economics. World Development (425) emphasizes global development, including environmental sustainability.

Figure 9.

Most local cited sources (Source: by the authors, Software: Bibliometrix 5.0).

Other journals, such as Ecological Economics, American Economic Review, and Journal of Business Ethics, cover ecological economics, business ethics, and international relations. Collectively, these journals concentrate on energy, sustainability, and economics, reflecting their alignment with research on global value chains and eco-friendly transitions.

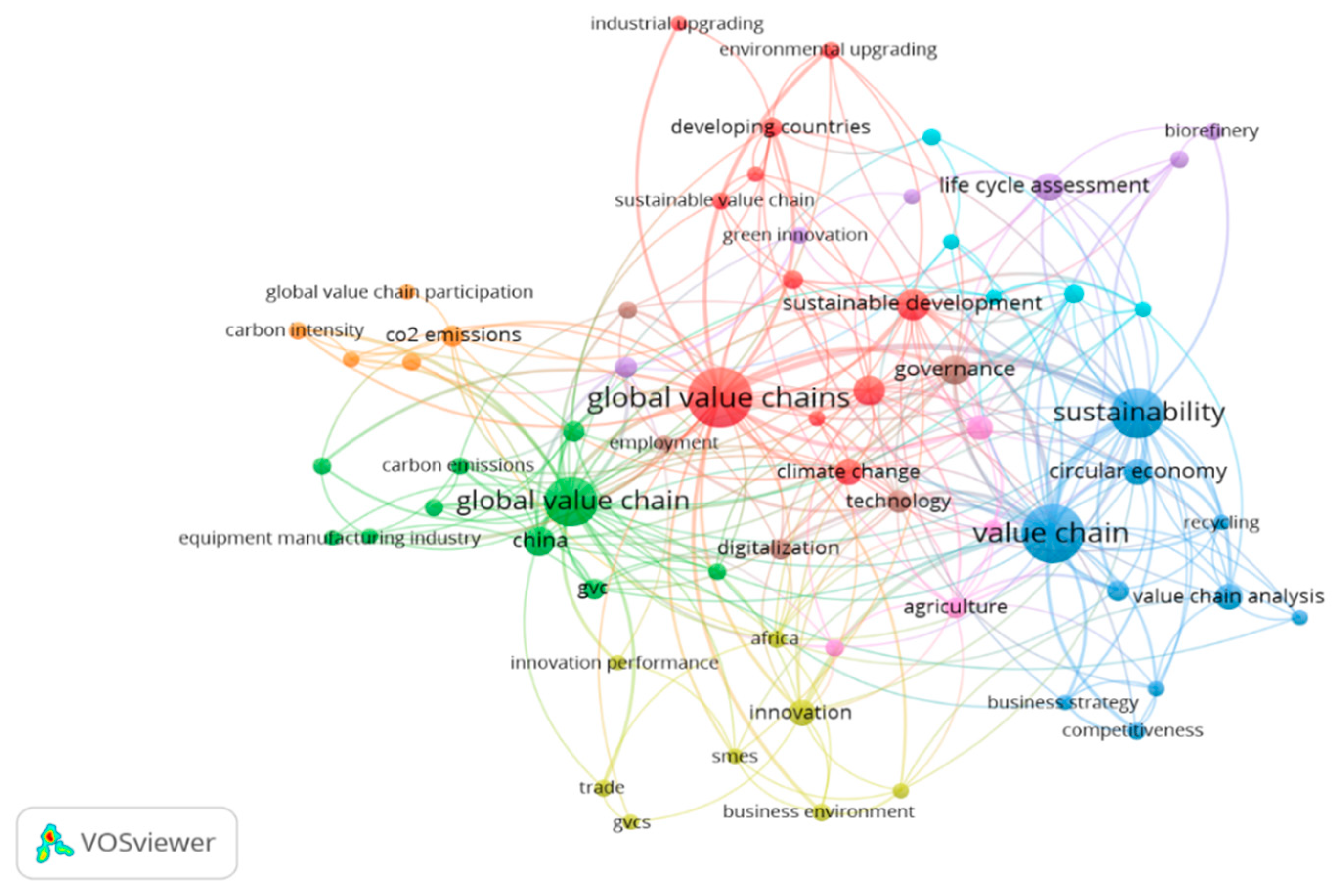

4.1.7. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis Summary (VOSviewer)

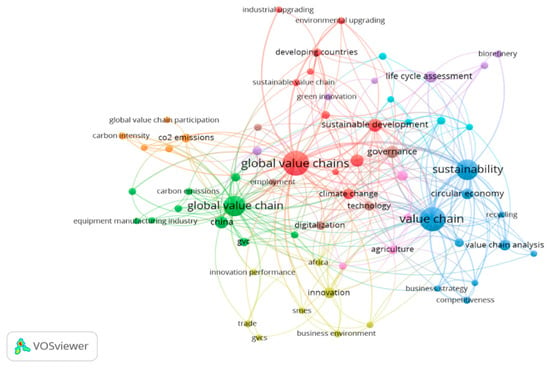

The VOSviewer (1.6.20 version) keyword clustering reveals six major thematic clusters surrounding the central topic of global value chains (GVCs), illustrating a complex and interconnected research landscape (Figure 10). The red cluster, centered on global value chains, reflects a development-oriented and policy-driven perspective, encompassing terms such as developing countries, environmental upgrading, sustainable development, and governance. This indicates a focus on institutional and structural challenges faced by emerging economies in transitioning toward sustainability. The blue cluster, anchored by value chain and sustainability, emphasizes environmental and circular economy concerns, with related terms like recycling and value chain analysis, highlighting efforts to reduce waste and enhance resource efficiency along supply chains. The green cluster, led by global value chain and China, presents a more industrial and emissions-focused orientation. Keywords such as carbon emissions, equipment manufacturing industry, and digitalization indicate an interest in the environmental consequences of industrial GVC participation, particularly within key manufacturing hubs. The yellow cluster highlights themes of innovation, trade, and SMEs, investigating how firm-level dynamics and broader economic environments shape GVC engagement and performance.

Figure 10.

Keyword Co-Occurrence (Source: by the authors, Software: VOSviewer (1.6.20 version)).

Functioning as a conceptual bridge, it connects economic and institutional considerations. Meanwhile, the orange cluster, containing terms like CO2 emissions, carbon intensity, and GVC participation, overlaps with both the green and red clusters, focusing on the environmental consequences of GVC integration and the quantification of emissions. Finally, the purple cluster, centered on life cycle assessment and biorefinery, represents methodological tools for sustainability assessment, often linked to technological innovation and resource analysis, thereby aligning with both the blue and red clusters. These clusters are not isolated; rather, they exhibit strong interconnections. Bridging terms such as climate change, technology, and digitalization link the governance and sustainability dimensions (red and blue clusters) with industrial and innovation-related themes (green and yellow clusters), demonstrating that sustainable transitions in GVCs require coordinated efforts across environmental policy, technological advancement, and institutional reform.

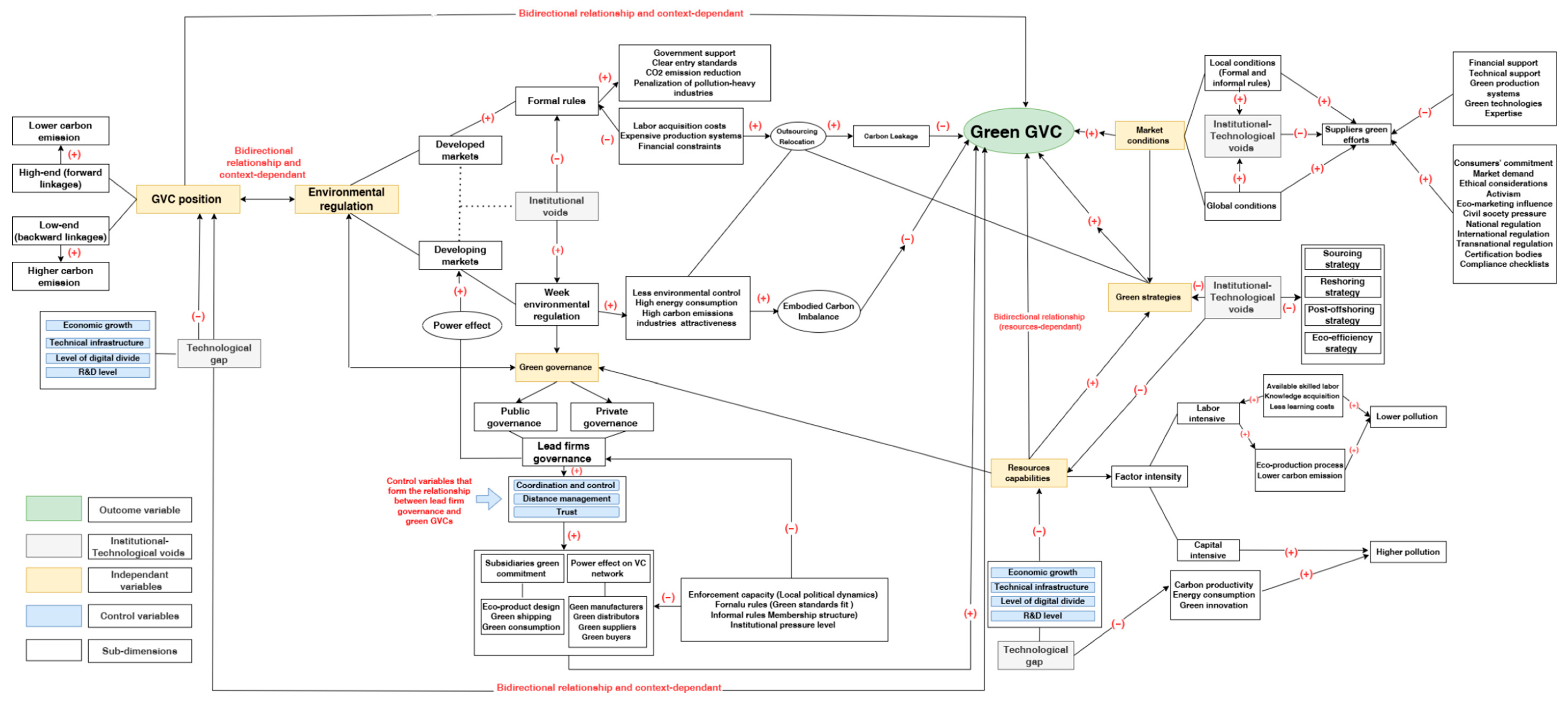

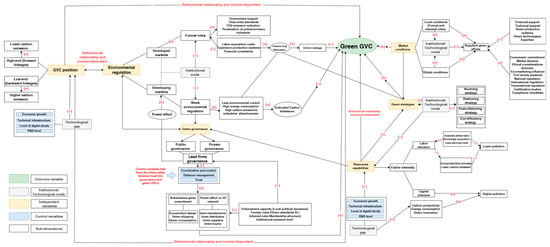

4.2. Results of the Content Analysis and Framework Building

Our systematic review identified two major themes concerning the interplay between GVCs and environmental performance, which are defined and explained below under two dedicated subheadings. The first theme of institutional voids examines how gaps in formal institutions, governance mechanisms, and regulatory environments in which GVCs are embedded influence environmental practices. This theme represents top-down mechanisms through which institutional voids shape environmental behaviors and broader environmental performance. The second theme focuses on the role of technology gaps and the capacities of less-developed firms in contributing to the environmental sustainability of their GVCs. The conceptual model developed in this study (Figure 11) illustrates the complex interactions among independent, control, and moderating variables and their collective influence on the outcomes of Green Global Value Chains (GVCs). It highlights how technological gaps, institutional gaps, or their combined effects can shape green GVC performance while explicitly considering the contextual conditions of the countries involved. All extracted outcome variables, control variables, moderators, mediators, and drivers are listed in Tables S1–S3. By integrating these multiple pathways, the model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the mechanisms through which technological gaps and institutional voids affect environmental performance, capturing both direct and indirect effects as well as potential moderating influences. This visualization enables readers to see the interplay between various factors and the conditional relationships that drive green GVC performance. Overall, our review considers both the influence of institutional voids and technological gaps on green GVC outcomes and supports the development of an integrative framework based on all the identified variables (See Tables S1–S3), depicted in Figure 11, that synthesizes insights from the reviewed literature.

Figure 11.

Environmental performance in GVC framework (Source: Authors’ elaboration).

4.2.1. Institutional Voids’ Influence on GVC Environmental Performance

The influence of the institutional environment on the environmental performance of GVCs has been widely discussed [22,32,50,55,66,76]. Environmental regulations create a framework that encourages industries to adopt cleaner practices by setting clear standards and discouraging environmentally harmful activities [31,55]. They are considered effective tools for promoting green practices in GVCs that align with sustainability goals and minimize negative ecological impacts [26,34,46], playing a critical role in reducing GHG emissions by incentivizing cleaner production and penalizing pollution-intensive industries [28]. However, despite their core objective of promoting green production, environmental regulations may face adoption challenges. Strict regulations increase costs related to labor and green investments in production systems, particularly for firms in developing countries with limited financial and innovative capabilities. These higher costs can discourage the transition to eco-friendly initiatives. Consequently, it is necessary to recognize that each region embedded in a GVC requires environmental support policies tailored to its distinctive characteristics. One key challenge is carbon leakage through international trade due to differences in environmental regulation levels across countries [32]. Given the institutional voids across regions, environmental regulations should be adapted to local contexts to effectively reduce emissions [56]. Strict and uniform environmental policies in developed countries increasingly drive polluting firms to relocate or outsource production to nations with weaker regulations [63]. As developing countries become more integrated into GVCs, this can result in higher energy consumption and increased pollutant emissions. Weak environmental regulations in these countries may turn them into “pollution havens,” attracting high-emission industries due to their comparatively lower institutional environmental standards. This leads to imbalances in the environmental impact of imports and exports of intermediate products produced for developed economies [57]. Therefore, while such regulations aim to reduce overall pollution, they may instead shift polluting activities to regions with less stringent environmental controls [63].

Moreover, previous research shows that environmental regulations can benefit high-polluting sectors within global value chains (GVCs) because these industries often relocate operations to countries with weaker environmental laws, allowing them to continue operating with minimal disruption [20]. As a result, these pollution-shifting practices to developing countries with fewer regulations fail to account for long-term environmental performance in both regions, operational outcomes related to knowledge transfer and expertise, and financial outcomes associated with the costs of relocating operations [64,79]. A strong environmental framework can also be attractive to some multinational enterprises (MNEs) in their market choice and partnership decisions along the value chain and is closely associated with the firm’s level of GVC participation [29]. Conversely, weak environmental regulations can disadvantage countries with less stringent policies, as these countries may receive business propositions aimed at circumventing stricter regulations, potentially leading to long-term environmental degradation. Research also highlights the link between environmental regulation and firm-level characteristics, such as financial and innovation capabilities, which determine a firm’s ability to adopt green technologies. Some studies suggest a positive causal relationship, where higher levels of environmental regulation promote green technologies and low-carbon innovations in GVCs [31,65]. However, other authors argue that properly designed environmental standards can trigger innovation due to cost pressures. Accordingly, policies should shift focus from mere pollution control to enhancing resource productivity, thereby fostering both environmental protection and industrial competitiveness [23]. Weak environmental regulation can harm a country’s environmental reputation and hinder future partnership opportunities with firms that base market decisions on environmental values and outcomes. In addition, the relationship between environmental regulation and firm-level responses is conditioned by external factors such as trade methods, factor intensity (labor or capital), and the degree of ecological damage generated by the industry sector [32]. Under certain conditions, government regulation may exert some influence, but it alone cannot drive innovation. Innovation is primarily guided by external factors such as governance challenges, high costs, and limited financial support from the government [65].

Role of Green Governance

Green governance represents a mechanism for aligning human-nature interactions by establishing institutional frameworks that support scientific decision-making and maintain environmental system stability. Nevertheless, implementing green governance practices remains challenging, regardless of government support for firms through taxation or the country’s economic and market conditions. In some contexts, private actors take the lead in green governance, implementing effective mechanisms to reduce ecological deficits within GVCs [1,19,66]. However, in certain regions, particularly developing countries, institutional quality may be insufficient irrespective of financial capabilities or technological advancement. This underscores the role of contextual disparities and the complexity of their influence on environmental outcomes. A key challenge lies in creating voluntary sustainability standards in developing countries that are both effective and equitable, particularly considering the economic disparities between developed and developing economies [50]. Although these standards aim to reflect the interests of developing countries, they face significant obstacles. Research emphasizes the role of lead firms as key power holders in driving environmental upgrading within GVCs by implementing instruments and directives that encourage subsidiaries to enhance their green commitment [80,81]. This type of governance, known as lead-firm or relational governance, relies on cooperation between lead firms and their subsidiaries [47]. Lead firms represent a hybrid governance form guided by institutional principles, aiming to develop governance instruments and intervene to achieve environmental sustainability outcomes in GVCs [30]. Recent studies suggest that lead firms are particularly effective in emerging economies, promoting the adoption of environmental practices across GVCs [55,82]. Consequently, the success of environmental practices in firms from emerging economies appears to be shaped by the interaction between private regulations, public institutions, and value chain governance [83,84]. Lead firms thus act as intermediaries between public and private green governance actors. Their ability to enhance eco-friendly practices in GVCs depends on critical success factors such as distance management, coordination and control mechanisms, and the establishment of trust between the parties [47]. Inter-firm relationships play a vital role in driving environmental upgrading within a GVC. Collaborative efforts among manufacturers, suppliers, and distributors/buyers are central to “greening” the value chain [43].

Lead firms, instead, adopt a mentoring-driven or relational governance approach, fostering trust, cooperative problem-solving, innovation, and motivating suppliers to upgrade in their own interest [47,48]. They exert influence across the entire chain network and extract value from subsidiaries and suppliers by shifting the hidden costs of sustainability compliance and associated risks upstream, often unseen by consumers, governments, or NGOs [81]. Moreover, lead firms play a critical role in managing environmental issues in GVCs amid contextual disparities between developed and developing countries. They are primary actors in legitimizing and influencing the adoption of standards by developing firms, either through direct participation in their development or by replicating established global norms [50]. The effectiveness of their influence is conditioned by local political dynamics and the interactions between private and public actors, which determine how these standards align with those from developed economies. Firms from developed economies typically exhibit greater capability and willingness to address environmental challenges [85]. Consequently, the diffusion of green values from MNEs in developed economies to firms in developing countries occurs mainly through membership, value chain governance, and institutional pressures [80]. This process is shaped by the complex and evolving interplay of transnational and local public–private actors within specific sectors and country contexts [50]. The relational governance model employed by lead firms enhances collaboration and coordination among actors to enable mutual ecological problem-solving [47]. Power relations and interactions among different actors influence chain activities affecting carbon emissions and ecological impacts, including product design, shipping operations, and consumption practices [30]. Research also highlights challenges in green governance across geographical distances, particularly in implementing standardized norms for all subsidiaries. The effectiveness of such standards is critical for governing highly complex and geographically dispersed production relationships between lead firms and local suppliers [50]. Therefore, green governance mechanisms are essential for guiding MNC behavior, improving economic governance, strengthening business environments, and ensuring corporate social responsibility compliance in developing countries [78].

Market Conditions

Local and global market conditions can either facilitate or hinder a firm’s efforts to adopt green practices within its embedded GVCs. At the local level, market conditions can support investments in green production systems, technologies, and expertise. Globally, consumer commitment to sustainable products plays an important role, guiding firms to respond to market demand for greener goods along the value chain. However, while consumers may express ethical concerns through activism, strong marketing strategies often emphasize product promotion, which can dilute pressure for meaningful change [22]. Simultaneously, business actors along GVCs are increasingly assessing and seeking to mitigate the environmental impact of their activities, as well as those of their suppliers and service providers. This trend is driven by rising consumer awareness of the environmental consequences of production and transportation, numerous environmental campaigns by civil society groups, and the proliferation of national, international, and transnational environmental regulations [25]. Moreover, the growing demand from ethically conscious consumers for greener products creates new market opportunities for firms capable of modifying existing offerings or developing new, environmentally friendly products. Consumers increasingly consider environmental attributes as part of their broader purchasing decisions [16,25,34]. Despite lead firms’ commitment to sustainability, they often do not provide direct financial or technical support to suppliers for environmental upgrading [52]. In some cases, their role remains distant; rather than directly investing in greener supply practices, they rely on certification bodies and compliance checklists, creating an appearance of responsibility while shifting the actual burden onto suppliers [52]. For suppliers, environmental upgrading is both necessary to meet market demand and costly. Those who proactively adopt green practices can differentiate themselves, appeal to eco-conscious buyers, and secure long-term business [34]. However, the financial reality is often challenging: costs increase while promised benefits remain uncertain. Buyers demand sustainability but frequently refuse to invest in it, enforcing a double standard that forces suppliers to trade profitability for compliance [34]. In this context, sustainability is not merely a business strategy but a high-cost investment that may exceed the resources and capabilities of some firms.

Green Strategies

A firm can transform its internal processes by redesigning them according to new environmental standards or goals, adopting different strategies based on its characteristics and objectives. However, the implementation of green strategies is often constrained by the firm’s financial capacity, particularly when buyers provide limited support for the costs associated with environmental upgrading. In addition, restricted access to intangible resources, such as technology and expertise necessary for implementing effective green strategies. Researchers have proposed various strategies (See Table 14 and Table 15), such as sustainable sourcing, but these often fail to ensure lasting social and environmental improvements along GVCs and production networks [53]. Indeed, lead firms’ sourcing practices can sometimes undermine long-term sustainability goals. Meanwhile, sustainability departments often demand strict compliance with social and environmental standards, creating tensions between financial viability and sustainability objectives [52]. Green strategies can also be driven by government policies; for instance, some developing countries have implemented carbon reduction measures, including low-carbon pilot provinces, energy substitution programs, and the optimization of industrial and energy structures [61]. Furthermore, a firm’s embeddedness in GVCs and the development of the digital economy directly influence green strategies and innovation. Regions with higher numbers of green patents demonstrate greater technological and environmental innovation [29]. Another approach is reshoring, whereby firms’ commitment to environmental sustainability shapes internationalization decisions, supporting green GVC transitions through reduced GHG emissions and improved sustainability practices [64]. Moreover, firms’ relocation decisions are influenced not only by cost considerations but also by strategic alignment with green values and sustainability goals [64,79]. Stricter environmental regulations often act as a pull factor for sustainable reshoring decisions, as discussed in the previous section. However, a firm’s commitment to sustainability does not automatically result in reshoring. Instead, it can lead to two types of relocation strategies: global strategy introversion, in which firms return to their home country to align with domestic sustainability standards, or global strategy evolution, where firms relocate to another foreign country offering greener supply chains or regulatory incentives [64].

Table 14.

Government instruments for environmental performance in GVCs.

Table 15.

Lead firms’ instruments for environmental performance in GVCs.

An alternative green strategy, focused on processes rather than governance, is eco-efficiency, defined as an effective method for measuring and managing the sustainable development of economic and resource environments, reflecting the coordinated development of the economy–resource environment system [86]. This process-upgrading strategy reduces environmental impacts and resource consumption along the value chain, resulting in lower costs and economic gains [43]. However, its practical implementation remains challenging, as uniform eco-friendly practices across all firms are difficult to enforce, regardless of the degree of value chain participation or the firms’ organizational and technological capabilities.

Despite the lead firm’s commitment to sustainability, they do not provide direct financial or technical support for environmental upgrading to any supplier [52]. In some cases, their role remains distant; instead of directly investing in greener supply, they rely on certification bodies and compliance checklists, creating an illusion of responsibility while shifting the actual burden onto suppliers [52]. For suppliers, environmental upgrading is necessary to satisfy market demand but represents a sacrifice due to the associated costs. Those who take the initiative can differentiate themselves, appeal to eco-conscious buyers, and secure long-term business [34]. However, the financial reality often tells a different story: costs surge while promised benefits remain elusive. Buyers demand sustainability yet refuse to invest in it, enforcing a double standard that forces suppliers to trade profitability for compliance [34]. In this context, sustainability is not just a business strategy but a high-cost investment that may not align with each firm’s available resources and capabilities. Table 14 on government role, instruments, and enabling factors: This table summarizes how governments influence environmental performance in GVCs through regulations, locally adapted policies, and measures to prevent carbon leakage. It also highlights their role in promoting green innovation and supporting micro-firm capabilities, providing an enabling institutional environment for sustainable practices. In addition, Table 15 summarizes the role of lead firms, the instruments they employ, and the enabling factors that influence environmental performance in global value chains (GVCs). Lead firms act as central governance actors, guiding sustainability practices across the value chain through relational and mentoring-driven approaches. They deploy instruments such as environmental standards, certifications, monitoring mechanisms, and directives to encourage suppliers and subsidiaries to adopt eco-friendly practices. The effectiveness of these instruments depends on enabling factors, including the local institutional environment, firm capabilities, inter-firm trust, coordination mechanisms, and market conditions. By aligning governance tools with these enabling factors, lead firms can foster environmental upgrading, enhance compliance, and promote sustainable transitions across GVCs.

4.2.2. Technological Gap Influence on GVCs Environmental Performance

The literature identifies various factors related to national and firm technological capabilities, as well as the influence of firms’ limited resources and quality [87]. Firms participating in GVCs with different factor intensities exhibit varying production efficiencies due to differences in capital and technology levels [6,66]. Labor- or capital-intensive firms may struggle to adopt resource-efficient technologies, reducing their overall efficiency. In the context of green GVCs, firms relying on traditional methods face difficulties in meeting green standards and integrating into sustainable supply chains [57]. An increase in capital factors leads to higher production in capital-intensive sectors, altering the industry’s output structure and affecting carbon emission efficiency [71]. Moreover, capital intensity has significant negative effects on the impact of environmental regulation on upgrading a firm’s GVC position [20]. Therefore, labor-intensive firms embedded in GVCs have a key opportunity to improve their production processes. Businesses can reduce pollutant emissions through technological advancements, especially when the cost of compliance is high due to environmental regulations [32].

However, labor intensity also poses challenges, as achieving green outcomes requires a skilled workforce, which entails knowledge acquisition and learning costs. Therefore, firms within the same value chain are influenced by their internal, organizational, and technological capabilities in supporting the green transition mechanisms implemented across the chain. Research shows that high-skilled labor can reduce pollution, as it is concentrated in knowledge-based and high-tech industries that generate fewer emissions. A higher proportion of skilled labor is associated with lower pollution levels [70,78]. Skilled labor is crucial for high-tech, high-value subsectors focused on R&D, design, marketing, and after-sales, which can mitigate environmental impacts. However, an increase in skilled workers in polluting sectors may boost productivity and output, potentially leading to higher emissions [20,70,87].

Another perspective discussed in the literature is the role of technology and its significant influence on GHG emission levels in GVCs [66,77]. In recent years, with the continuous integration of digital technology into the real economy, GVCs have undergone substantial changes [60]. This section synthesizes the literature on the impact of technology on green GVCs, focusing on its effectiveness as a tool and examining how institutional and economic contexts, a firm’s position within its ecosystem, and a country’s digital maturity influence outcomes.

Green technologies effectively minimize pollution and other ecological damages along the global value chain [31]. Investments in technology enhance carbon productivity, reduce energy consumption, improve efficiency, and contribute to lower emissions across industries [56]. Low-carbon technological innovations support effective green industry transitions by improving environmental outcomes across production, trade, and consumption processes [68].

However, the benefits of investing in greener technologies, such as recyclable packaging, often favor exporters and retailers, while farmers and small-scale producers may lack the resources to adopt sustainable methods effectively [34]. Technology adoption is also context-dependent: significant differences in carbon productivity exist across regions, with technologically advanced economies achieving higher carbon efficiency [26]. Developed economies, with access to advanced green technologies, are better equipped to reduce the carbon intensity of their production processes, whereas developing economies face challenges due to limited technology adoption [57].

The lack of technology adoption can be related to firm-specific characteristics, a country’s level of connectedness, and the policies in place to support innovation. Moreover, existing studies on the relationship between technological progress and emission intensity often focus on a single country [2,12]. Since carbon emissions are a global issue, studies investigating the link between technology gaps and GHG emission intensity should adopt a cross-country perspective.

In developing countries, research has found a significant positive relationship between green technologies and sustainability [13]. This relationship can generate economic, social, and ecological value but also entails risks in consumer and financial markets [68]. Its effectiveness is conditioned by the government’s role in creating a supportive environment for green technology innovation, including strengthening intellectual property protections, providing green financial incentives, and cultivating talent for green innovation. Such support encourages companies to develop green technologies, which in turn can drive GVC upgrading [71]. Research also highlights the influence of a firm’s position within the GVC on technology adoption and its effectiveness.

The interaction between a firm’s GVC embedding position and technological progress reduces the positive impact of embedding on carbon emissions, as technological advances mitigate the environmental pollution associated with higher GVC positions [67]. An increase in GVC embedding significantly enhances green technology innovation efficiency, with industry heterogeneity characterized by pollution intensity and factor density [31,77].

Active GVC participation in developing countries promotes green innovation and sustained regional growth, with the effect being more pronounced for firms facing greater financial constraints, state ownership, labor-intensive operations, or pollution-intensive industries [72]. However, the degree of digitalization varies considerably across firms, largely depending on their connectivity levels. At the national level, disparities in digital maturity create further differences among countries within the same value chain.

The digital divide presents a major challenge, as countries with lower digital development struggle to adopt advanced technologies necessary for producing eco-friendly goods. In contrast, firms in advanced economies benefit from widespread technological diffusion, facilitating their transition to greener production processes. These challenges are particularly acute in developing countries, where the focus should be on the quality of GVC participation rather than merely its degree [74]. Furthermore, developing countries should prioritize foreign investment and technology transfer to build innovation capacity, avoid “low-end lock-in,” and achieve industrial upgrading and improved energy efficiency [74].

Disparities between developed and developing countries significantly influence the green transition of GVCs. Developed countries, aiming to maintain their dominant positions within GVCs, often control the outflow of high-tech products and services, which can generate greater environmental pressures globally [60]. This situation can negatively affect less developed and technologically advanced economies. While GVC participation can facilitate the import of advanced technologies and environmental standards promoting better energy management and renewable energy adoption it can also lead to the relocation of the most polluting production stages to developing countries, contributing to environmental degradation and energy inefficiency [63].

In this context, digital transformation plays a crucial role in facilitating the environmental performance of GVCs. The development of the digital economy has both direct and indirect positive effects on green innovation, enhancing technological capabilities and improving the integration of regional economies into GVCs by facilitating knowledge and resource exchange [29]. Research also highlights that Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) are particularly affected by digitalization; higher digital maturity improves their ability to integrate into sustainable value chains, optimize resources, and reduce inefficiencies [54].

Overcoming the digital divide between developed and developing countries is essential to ensure the global dissemination of green technologies through digital spillovers [60]. Developing countries should invest in building absorptive capacities within traditional industries to reap long-term benefits from digitalization. Leveraging foreign investment and technology can further enhance local innovation capacity, helping to avoid “low-end lock-in,” achieve industrial upgrading, and improve energy efficiency through scale and learning effects [74].

Moderating Role of Research and Development

Research and development (R&D) enable the development of green innovations and eco-friendly products. Encouraging investment in R&D is therefore essential for improving carbon productivity, achieving carbon neutrality, and maximizing energy efficiency [21,56,75]. From a global perspective, R&D enhances the competitive edge of regions embedded in GVCs by optimizing resource allocation, strengthening technological capabilities, and increasing innovation outputs, thereby improving their positioning in global markets [29]. Both technological and production-focused R&D represent key drivers of the green transition [69].

According to studies grounded in endogenous economic growth theory, R&D investment is a major driver of technological progress and positively contributes to green growth [4]. Technological gaps, however, remains a critical factor: while R&D investment can be challenging in developed countries, it provides a comparative advantage in global markets and enhances both environmental and economic performance [74]. Consequently, firms operating under institutional environmental regulations should increase investment in R&D and innovation to maintain green operations, accelerate industrial restructuring, and improve environmental outcomes [20,65]. Integrating R&D promotes subsidiaries’ adoption of low-carbon management practices [77] and strengthens firms’ capacities for technological upgrading [78].

GVC Embedding Modes and Technology Gap

Research suggests that distance is a crucial factor in mapping the ecological outcomes of GVCs. With the fragmentation of international production, the linkage between embedded industrial value chains and carbon emissions becomes increasingly complex, influencing both economic strategies and environmental governance [59,73]. Embedding modes affect green GVC performance, and GVCs can promote green growth only when a country’s GVC position is strong [58]. Institutional voids and technological gaps also matter: countries’ positions within GVCs significantly influence their carbon footprints. Forward industries such as basic materials, public utilities, machinery, energy supply, and transportation are deeply embedded and drive upstream value, whereas backward industries like consumer goods, real estate, education, arts, and professional services dominate global industrial structures [59,62,74].

These dynamics create distinct challenges for nations depending on their institutional and economic contexts [74]. Shorter, localized value chains tend to exhibit higher carbon emissions, as international fragmentation increases pollution [26,56,67]. Therefore, developing countries engaging in GVCs should focus not only on the extent but also on the quality of participation, improving market mechanisms, strengthening infrastructure, and fostering conditions that integrate domestic industries [74].