Abstract

The Thailand 4.0 agenda elevates entrepreneurship education (EE) as a lever to escape the middle-income, inequality, and imbalance traps, yet EE remains weakly embedded in basic education—especially in Thai language. We designed and piloted a community-economy context-based learning model integrating EE (CEC-EE) for Grade 12 Thai via a two-cycle R&D process: needs analysis (surveys and focus groups with teachers and students) and prototype development. The model operationalizes six instructional steps (6Cs: connect, comprehend, clarify, construct, carry over, and conclude) anchored in Mae Chan’s community economy and targets entrepreneurial language skills (ELSs) consisting of analytical reading and creative writing. In a one-group pretest–posttest with Grade 12 students (n = 32), academic achievement and ELSs—analytical reading and creative writing—improved markedly. Posttest means exceeded pretests with very large effect. Experts rated the model appropriate, feasible, and useful; teachers and students reported high perceived value alongside concerns about implementation cost, support capacity, and student readiness. The CEC-EE model offers a context-responsive pathway for embedding EE in Thai-language instruction; future work should employ comparative designs, multi-site samples, and cost-effectiveness analyses to assess scalability and sustained impact.

1. Introduction

Thailand remains stuck in the “middle-income trap”—caught between low-wage competitors and innovation-led economies. Long reliance on efficiency/volume production created a “competitive nutcracker,” stalling productivity and incomes and deepening inequality—the region’s second highest, with the richest quintile taking over half of income and the poorest under five percent [1]. In response, Thailand 4.0 prioritizes innovation, technology, and creativity to build a sustainable, inclusive, innovation-driven economy [2]. Thailand 4.0 is a national economic transformation agenda launched in 2016 to shift the country from efficiency-driven growth toward a value-based, innovation-driven economy, emphasizing technological upgrading, innovation ecosystems, and workforce reskilling. Consistent with this direction, policy analyses describe Thailand’s Industry/Thailand 4.0-related measures as spanning digital infrastructure development, skill formation, and targeted industry support, highlighting the centrality of human capital for competitiveness in an innovation era.

Although Thailand 4.0 is frequently framed as an economic upgrading agenda, national policy discourse also includes sustainability-oriented extensions that emphasize bioeconomy, circularity, and green growth. In particular, Thailand’s Bio-Circular-Green (BCG) model is presented as a mechanism underpinning Thailand 4.0 by integrating bioeconomy, circular economy, and green economy principles, with explicit attention to environmentally friendly development and SDG alignment. This matters for education because it implies that “entrepreneurship capacity” should not be interpreted as profit seeking alone, but as competence for value creation under resource constraints, ethical trade-offs, and community–environment interdependence.

Strengthening entrepreneurship and human capital, therefore, is central: Thailand hosts around 3.3 million SMEs, accounting for 99.5% of all firms and serving as a primary source of employment (about 69% of total private-sector jobs) [1]; SMEs contribute roughly 35% of GDP. Yet SMEs continue to face infrastructure, regulatory, and capability constraints [3], making entrepreneurship capacity-building crucial for productivity growth, inclusive development, and community resilience.

The link between Thailand’s macroeconomic challenge, entrepreneurship, and community economy is as follows. Thailand 4.0 frames competitiveness as a function of innovation and human capital, but in practice, the most widespread “innovation system” is not large corporations; it is the SME sector that anchors local employment and livelihoods. Therefore, entrepreneurship capacity-building must occur not only at the national level but also at the local level, where enterprises are embedded in communities, cultures, and natural resource systems. The community-economy lens is relevant here because it defines economic activity as more than market exchange: it includes cooperation, reciprocity, local governance of shared resources, and ethical negotiation of value. In other words, community economy specifies the type of entrepreneurship that can realistically strengthen resilience and inclusion under resource and sustainability constraints. This is why community enterprises are not incidental examples but theoretically appropriate learning contexts for developing entrepreneurship and sustainability-oriented competencies through schooling.

Entrepreneurship is also recognized as a 21st-century competency: UNESCO [4] calls for foundational, cross-occupational, and career-specific skills, while EE fosters creativity, problem-solving, adaptability, and initiative [5] and builds self-confidence and transferable skills for uncertain labor markets [6]. In Thailand, the Ministry of Education promotes career readiness via self-awareness, interest exploration, and labor-market preparation, and national initiatives support entrepreneurship through the National Education Council and university curricula [7]. Yet substantive EE integration in basic education is limited, with little evidence of EE embedded in Thai language—a subject central to communication, identity, and cultural continuity.

Prior Thai EE research centers on vocational/higher education as cognitive-apprenticeship for vocational students [8], junior-entrepreneur curriculum for upper-secondary learners [9], undergraduate concentrations [10], graduate incubation [11], and crowdsourcing pedagogy [12], showing national attention but a post-secondary bias. Basic education seldom embeds EE in subjects, and Thai language that is vital for communication, analytical reading, and creative writing receives even less. Thus, a model that explicitly integrates entrepreneurial skills into Thai-language learning while leveraging local community contexts for authenticity and meaning is still lacking.

Embedding EE in local community contexts can bridge education and the economy: local enterprises offer authentic cases that build pride, attachment, and practical skills; e.g., studying agricultural enterprises grounds abstract concepts in real activity, fostering globally relevant yet locally anchored entrepreneurial thinking aligned with Thailand 4.0 [13]. Despite policy momentum, systematic basic-education models using community-economy enterprises are scarce, and Thai-language strategies that pair analytical reading/creative writing with entrepreneurial orientation remain underdeveloped. This gap matters because well-rounded entrepreneurs need not only technical knowledge but also strong communication skills; cultural grounding; and the capacity to interpret, persuade, and innovate through language.

In this study, entrepreneurial language skills (ELSs) refer to the Thai-language competencies required to enact entrepreneurship in real settings. Beyond general literacy, ELSs include the ability to (1) read analytically to identify opportunities and constraints from community/enterprise texts (e.g., product narratives, regulations, customer feedback, and sustainability claims); (2) write creatively and persuasively to communicate value (e.g., proposals, pitches, promotional narratives, and reflective reports); and (3) negotiate meaning with stakeholders through appropriate register, evidence use, and culturally credible storytelling. In this sense, ELSs are the practical bridge between EE and Thai-language education: entrepreneurial thinking becomes actionable only when learners can translate ideas into clear, credible communication that mobilizes resources, persuades audiences, and justifies decisions. This bridge is directly aligned with Thailand 4.0’s emphasis on innovation-driven talent, because innovation is not merely having ideas but communicating them and articulating a value proposition, explaining novelty, and gaining social acceptance, especially within community-based enterprises, where trust, culture, and legitimacy matter. This study treats ELSs as measurable Thai-language performance that can be demonstrated through students’ analytic reading processes and the quality of their creative, audience-oriented writing in entrepreneurial genres.

This study develops an instructional model that integrates EE into Grade 12 Thai through community-economy contexts. Situated in Mae Chan District, Chiang Rai, and by using the Choui Fong Tea Plantation as a key enterprise, the model embeds Thai instruction in lived local realities to demonstrate meaningful EE integration within a core basic-education subject. We acknowledge that a tea plantation is a commercially oriented enterprise; however, community-economy perspectives explicitly include hybrid forms where market activities are embedded within local social and ecological relations. In this study, the plantation context is used not to idealize business success, but as a concrete site for students to analyze how enterprises depend on natural resources and community legitimacy.

1.1. Research Questions

The research is guided by two questions: (a) What are the instructional conditions, challenges, and needs for integrating entrepreneurship education into Grade 12 Thai-language learning through community economy contexts? (b) To what extent, and in what ways, can such a community economy context and EE model improve students’ academic achievement and entrepreneurial language skills?

1.2. Purposes of the Study

The purpose of this study was to develop and test a community economy context-based entrepreneurship education model (CEC-EE) for Grade 12 Thai-language instruction in Mae Chan, Thailand. Specifically, the study aimed (1) to identify instructional conditions, implementation challenges, and stakeholder needs for integrating entrepreneurship education into Thai-language learning through community-economy contexts; and (2) to evaluate the model’s effectiveness in improving students’ Thai academic achievement and entrepreneurial language skills (ELSs), with attention to analytical reading and creative writing outcomes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Positioning

Beyond summarizing prior work, this study is explicitly anchored in a sociocultural and practice-based view of learning, where knowledge and skills develop through participation in meaningful activities mediated by language, tools, and social relations [14,15,16]. We treat entrepreneurship not only as an economic activity but as a situated social practice embedded in local norms, networks, and resource-governance arrangements [13,17,18]. In parallel, language is conceptualized as social action that people use for genre-structured discourse to coordinate work, negotiate value, and legitimate ideas in public settings. This combined theoretical stance provides the logic for why community-economy contexts can function as authentic “learning ecologies” for EE and ELS development.

To improve conceptual clarity, the literature is organized from context to policy alignment to pedagogy/competencies and then language mechanism. Consequently, this review consists community economy, entrepreneurship education (EE), and entrepreneurial language skills (ELSs) to inform Thai-language education.

2.2. Community Economy

Community economy reframes economic life as plural practices, including cooperation, reciprocity, commons, and beyond market exchange [18,19]. Communities are asset-based systems generating socially and ecologically embedded value [20]. Embeddedness highlights how social relations, trust, and norms structure activity [17]. Ostrom [21] shows communities can govern shared resources via local rules and monitoring, informing community-owned and anchor-linked enterprises that retain local wealth [22]. Tools like the Community Capitals Framework and local multipliers assess how investments spiral into well-being [23]. Strategies blend cooperatives, social enterprises, mission finance, and democratic participation [19], while cautioning against romanticizing the local without inclusive, multilevel policy links [17,18].

Taken together, community-economy theory clarifies that entrepreneurship is not only market behavior but a relational and governance-based practice shaped by trust, norms, and shared resource management. This perspective is crucial for education because it identifies what counts as “value” in community enterprises (social, cultural, and ecological, as well as economic) and explains why locally grounded enterprises can function as authentic learning settings. Therefore, community economy provides the contextual foundation for a learning model that positions students as participants in community value-creation practices rather than passive recipients of abstract business concepts.

2.3. Thai Policy and Education

Thai policy aligns via SEP and people-centered development [1]. The National Education Act positions schools as community-linked [8]; OBEC emphasizes career readiness, teamwork, and entrepreneurial mindsets [4,7]. Integrating community enterprises—agroinnovation, textiles, and recycling—links Thai-language, cross-curricular learning, and entrepreneurship [12,23], contingent on governance, equity, and policy support [4,20].

Synthesizing these policy directions, Thai basic education is expected to develop not only academic proficiency but also transferable competencies as initiative, collaboration, and career readiness, while remaining culturally grounded and responsive to local development agendas. However, policy aspirations do not automatically translate into subject-specific pedagogy. In practice, Thai-language classrooms often remain assessment-driven, leaving limited structured opportunities for students to use Thai for authentic public communication tied to economic and community life. This policy–practice gap motivates the need for a concrete instructional model that shows how entrepreneurship-relevant competencies can be enacted inside Thai-language learning through structured tasks, community partnerships, and assessable language outputs. This creates the bridge to the EE and ELS literature.

2.4. Entrepreneurship Education (EE)

Entrepreneurship encompasses innovation, value creation, and personal growth [24], so EE cultivates opportunity recognition, risk-taking, leadership, and creative problem-solving [5]; evidence links EE to greater creativity, confidence, and resilience [25], with effective programs balancing cognitive and experiential learning, experimentation, and reflection on failure [26], while reviews foreground inclusivity, pedagogy, technology, and mindset [27,28], and comparative analyses identify five dimensions: attributes, curriculum design, PEK, guidance/monitoring, and evaluation [29,30]. In Thailand, EE appears in vocational, secondary, and higher education and incubators [8,31], including crowdsourcing approaches [12], yet integration remains weak in basic education and especially in Thai language [32].

Recent syntheses argue that the EE field is moving toward more integrative and multidisciplinary models (e.g., combining ethics, culture, and social capital with pedagogy) and that future EE research must clarify mechanisms rather than merely reporting outcomes [28]. In parallel, rigorous school-level evidence suggests that EE effects depend heavily on design features and implementation conditions: for example, compulsory EE has been tested using field quasi-experimental approaches, showing that entrepreneurship instruction can shape behavioral outcomes, but effects are sensitive to how learning activities are structured and supported [33]. However, even when EE is effective, many studies still treat communication as a generic “soft skill,” leaving under-specified how learners develop the language practices through which opportunities are articulated, evaluated, and presented to audiences. This limitation is crucial for subject-based schooling: if entrepreneurship is enacted through discourse (e.g., making claims, using evidence, and persuading stakeholders), then EE models implemented inside language subjects must define and assess these discourse practices explicitly. This creates the need for an ELS mechanism in Thai-language education.

The EE literature offers clear guidance on what should be developed (opportunity recognition, creativity, resilience, and leadership) and how it is most effectively developed (experiential tasks, reflection, iteration, and supportive assessment). Importantly, the Thai literature indicates that EE has been implemented mainly in vocational, higher education, and incubator contexts, leaving a gap in basic education and subject-specific integration. This suggests a need for a model that translates EE competencies into discipline-based classroom practices, leading directly to the role of language: entrepreneurial competencies must be enacted and assessed through communication, genre performance, and interaction.

2.5. Entrepreneurial Language Skills (ELSs)

ELSs, which refer to opportunity recognition, pitching, negotiating, and value communication, align with learner-centered policy and transferable skills [1,4,7]. Theoretically, ELSs extend communicative competence into entrepreneurial genres [34,35], drawing on ESP and genre pedagogy for authentic events [36], and on CLIL and multiliteracies for multimodal, intercultural communication [32,37]. Pedagogically, project/problem-based learning supports inquiry, iteration, and public communication, with Thai applications via apprenticeship, incubators, and crowdsourcing tied to local enterprises [8,12]. Assessment uses genre-based rubrics that integrate linguistic accuracy with feasibility/value creation [35], alongside UNESCO’s integrated competency frameworks [4], with iterative drafting/feedback building language and entrepreneurial thinking. However, systematic ELS integration in Thai-language curricula is scarce; few models connect Thai instruction to community-economy contexts [38], and priorities include co-design with enterprises, scaffolding register shifts, and equity [35,37]. To date, no models have integrated EE and ELSs into basic-education Thai using community-economy contexts—an urgent gap relative to Thailand 4.0, SEP, and global competencies.

Recent empirical work strengthens the case that entrepreneurship-related learning can be advanced through language-focused interventions when entrepreneurial practice is translated into teachable communicative tasks. For instance, an entrepreneurship awareness-raising intervention with ELT learners reported improvements in entrepreneurial intention, mindset, and self-efficacy, indicating that entrepreneurship-oriented content can be meaningfully integrated into language-learning designs [38]. In addition, multimodal and genre-based pedagogy has been used to teach entrepreneurial presentation genres such as elevator pitches, helping learners manage audience engagement, persuasive structuring, and strategic use of multimodal resources [39]. Complementing this, entrepreneurship research itself increasingly emphasizes pitching as a central entrepreneurial practice through which ventures are evaluated and legitimacy is negotiated, underscoring why genre awareness, rhetorical control, and evidence-based claims are not peripheral but core entrepreneurial competencies [40,41]. Together, these studies support treating ELS as a measurable mechanism linking EE to language education, yet they also highlight a remaining gap: secondary-level, subject-based models (especially in national-language subjects such as Thai) are still rare, and few studies embed entrepreneurial genres within community-economy contexts where social, cultural, and ecological value are negotiated alongside economic value.

The ELS literature provides the missing mechanism linking entrepreneurship to Thai-language learning: entrepreneurial action requires students to read critically, negotiate meaning, and produce genre-appropriate texts (e.g., pitches, proposals, and promotional narratives). While existing research supports certain pedagogies, there remains limited evidence on integrated models that combine EE competencies and entrepreneurial genres within Thai basic education using community-economy contexts. Accordingly, the present study addresses this gap by developing and testing a community economy context-based learning model that integrates EE and ELSs within Grade 12 Thai, with outcomes evaluated across achievement, analytical reading, and creative writing.

Despite growing interest in EE and CBL, three gaps remain salient for secondary-level language education. First, many EE studies emphasize mindsets or intentions but do not specify how disciplinary learning mechanisms (e.g., reading-to-write processes, genre control, and rhetorical decision-making) produce observable gains in language outcomes. Second, CBL research in schools often demonstrates benefits in STEM or vocational domains, yet rarely theorizes language as the mediating tool through which entrepreneurial activity is learned, coordinated, and legitimized. Third, empirical work that explicitly integrates EE with language education in basic education settings remains limited and often focuses on general communication rather than the specific discourse practices through which entrepreneurial value is enacted.

Accordingly, this study contributes by (i) theorizing entrepreneurship as a situated practice that is linguistically mediated; (ii) operationalizing this mechanism through ELS-oriented reading–writing tasks embedded in community-economy contexts; and (iii) providing an R&D-tested instructional model for Grade 12 Thai that produces measurable outcomes in achievement, analytical reading, and creative writing.

3. Research Methodology

This study used a two-cycle Research and Development (R&D) design. R1 aimed to develop a prototype CEC-EE model by diagnosing current condition, challenges, and needs of CEC-EE. R2 evaluated students’ academic achievement and ELSs after CEC-EE instruction. The research design is organized around two research questions (RQ1–RQ2) and two corresponding phases (Phase 1, needs assessment and model development; Phase 2, model implementation and outcome evaluation).

R1: Exploring current conditions, challenges, and needs of CEC-EE instruction.

RQ1: What are the instructional conditions, challenges, and needs for integrating entrepreneurship education into Grade 12 Thai-language learning through community-economy contexts?

The primary objective of R1 was to examine teachers’ and students’ perspectives of current conditions, challenges, and needs of CEC-EE. We used a mixed-methods combining survey with focus group discussions (FGDs). Quantitatively, two parallel questionnaires—for Thai-language teachers (n = 86) and Grade 12 students (n = 165), recruited via purposive sampling from schools in Mae Chan and surrounding areas where community-economy contexts (e.g., local enterprises, OTOP, and tourism/agriculture) were accessible and relevant to implementation. We employed five-point Likert scales across three domains (current conditions, 14 items; challenges, 14 items; and needs

Content validity for both was established by five experts yielding IOC indices of 0.80–1.00 across all domains. Pilot testing showed strong internal consistency: for teachers (n = 30), Cronbach’s α = 0.87 (current conditions), 0.81 (challenges), and 0.88 (needs); for students (n = 35), α = 0.90, 0.87, and 0.85, respectively. The finalized instruments were administered to purposively selected participants: 86 teachers and 32 Grade 12 students. Quantitative data were summarized with frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations.

3.1. FGDs

The qualitative component used FGDs to elicit in-depth perspectives on the current conditions, challenges, and needs of CEC-EE. FGDs were held separately with two stakeholder groups: 12 teachers, guided by a six-item semi-structured protocol (three current-condition questions, one challenge question, and two needs questions) as Appendix A, and 6 Grade 12 students, using an equivalent six-item guide. Participants were selected to represent a range of experience with context-based learning and/or EE. Both guides were reviewed by five experts; content validity assessed via IOC was 0.80–1.00 across all items, exceeding accepted thresholds. Following expert feedback, the guides were pilot-tested with three non-sample Thai-language teachers and three students to verify wording and optimize discussion dynamics. Thai-language teachers (n = 12) with more than five years’ CEC/EE teaching experience and Grade 12 students with prior CEC/EE learning were purposively sampled.

FGD transcripts were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s [42] six-phase thematic analysis: familiarization, systematic coding, theme development, theme review/refinement, defining and naming themes, and reporting. The coding process was conducted independently by two authors (intercoder reliability = 0.82, above conventional benchmarks), with discrepancies resolved by consensus. Drawing on surveys, FGDs, and the literature, the authors developed the first draft of the CEC-EE model and then engaged a panel of five experts to evaluate its propriety, accuracy, feasibility, and utility [43].

R2: Evaluating the impacts of CEC-EE model.

RQ2: To what extent, and in what ways, can such a community-economy context and EE model improve students’ academic achievement and ELSs (analytical reading and creative writing)?

This research phase evaluated the effects of the CEC-EE model on Grade 12 students’ academic achievement and ELSs using a one-group pretest–posttest design (p. 113) [44]. Adopted for practical and developmental reasons, such exploratory designs are recommended for initial model development and refinement [45,46]. Conducted in a single school where random assignment and parallel comparison groups were infeasible due to administrative constraints, ethical concerns about withholding instruction, and small enrollment, the design measured the same participants before and after CEC-EE to estimate short-term change, acknowledging threats to internal validity and framing results as exploratory rather than confirmatory [45,46]. The population was 165 Grade 12 students at Mae Chan Witthayakhom School; the sample was one intact class (M.6/4, n = 32), selected as a naturally occurring cluster.

We developed a Grade 12 academic achievement test aligned to the CEC-EE model using Mae Chan’s community economy as context: the first draft had 70 multiple-choice items, content validity was reviewed by five experts (IOC = 0.50–1.00), and a pilot with 30 students informed item selection based on acceptable difficulty (P = 0.20–0.80), retaining 40 items with P = 0.45–0.60 and discrimination within the acceptable range (r = 0.20–1.00), specifically r = 0.65–0.89; reliability for these 40 items was 0.86. The ELS evaluation comprised two sections—analytical reading and creative writing—with corresponding five-point rubrics; its IOC ranged from 0.80 to 1.00. For creative writing, two expert raters independently scored all scripts with the analytic rubric, yielding Cohen’s kappa = 0.84; minor discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and final scores reflected agreed ratings, enhancing scoring consistency and validity.

3.2. The CEC-EE Instructional Model

The CEC-EE instructional model consists of four key components, as follows:

- 1.

- Principles and Concepts

The CEC-EE model fuses context-based learning (CBL) and entrepreneurship education (EE): CBL anchors classroom content in real-life contexts, while EE aligns curriculum with entrepreneurial practice to foster goal-setting, self-monitoring, and experiential learning. Together, they connect theory to practice and build students’ capacity to identify, create, and pursue business opportunities.

- 2.

- Objectives

The CEC-EE instructional model is designed to enhance Grade 12 students’ academic achievement and ELSs in Thai language.

- 3.

- Instructional Procedures

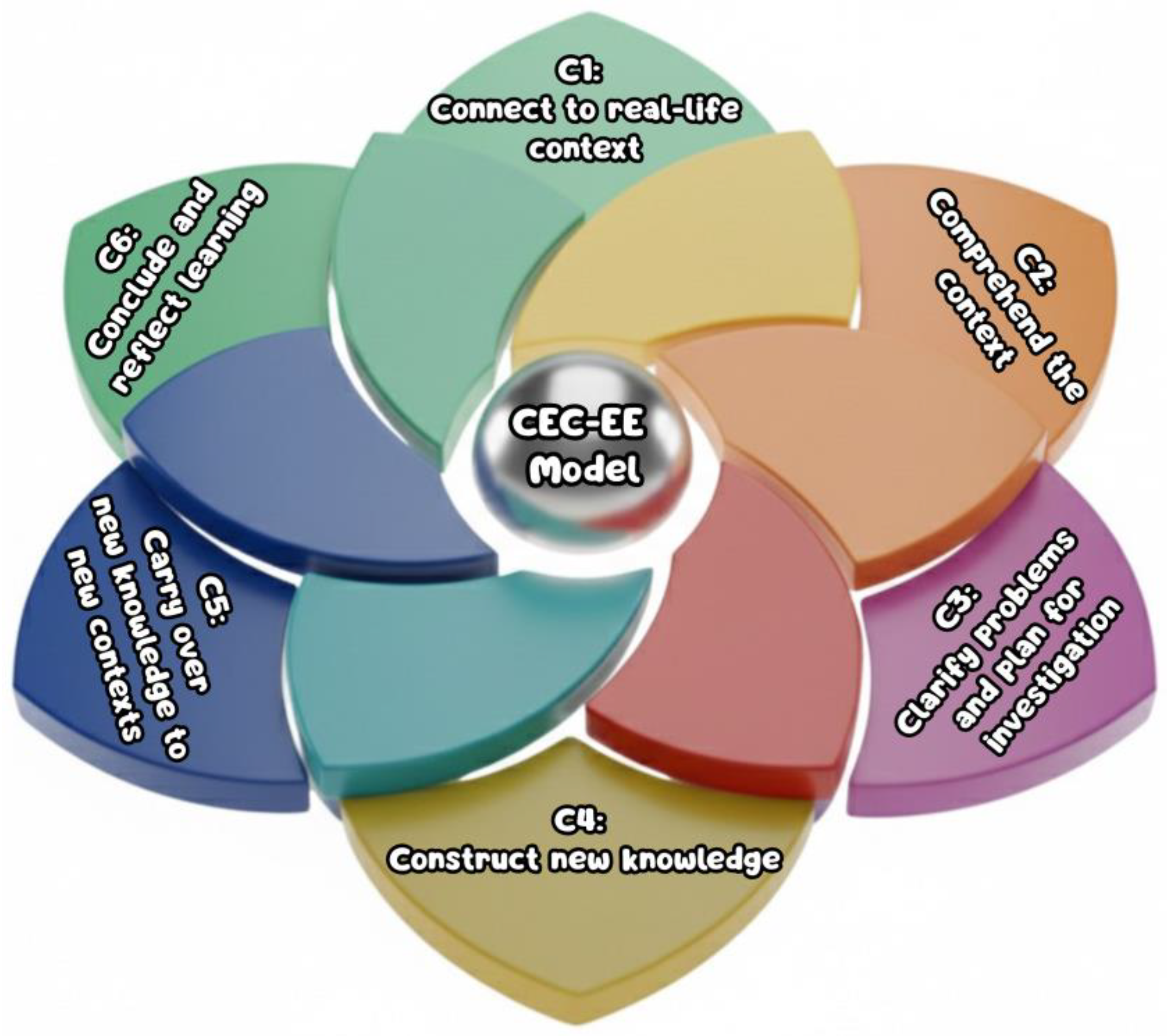

The instructional procedures of CEC-EE model are structured into six steps, as follows (6Cs of CEC-EE model):

C1: Connect to real-life context.

The teacher starts by gauging prior knowledge with a brief quiz or questioning, then introduces relevant community contexts via engaging media, drawing on Mae Chan’s local economy, i.e., Choui Fong Tea Plantation.

C2: Comprehend the context.

Students form mixed-ability groups to discuss and build a shared understanding of the community context, while the teacher guides key aspects—context characteristics, entrepreneurial opportunities, and relevant Thai-language knowledge and skills.

C3: Clarify problems and plan for investigation.

In groups, students pose questions and pinpoint problems of interest in the context. The teacher trains them to generate sub-questions, identify entrepreneurship challenges in the local economy, and craft inquiry plans.

C4: Construct new knowledge.

Students carry out authentic investigations in Mae Chan’s community economy, constructing new knowledge through real tasks that aim to improve academic achievement and ELSs in line with curriculum standards.

C5: Carry over new knowledge to new contexts.

Students transfer learning from Mae Chan’s economy to related settings—applying ELSs in other community-based contexts (e.g., different local tourist sites) and extending integrated language skills to more complex situations.

C6: Conclude and reflect learning.

Teachers and students jointly synthesize and reflect on knowledge and language skills gained through CEC-EE centered on Mae Chan’s economy. Students share reflections on their practices—what they encountered and understood, and how they solved problems. The six teaching steps of CEC-EE model can be illustrated as Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The CEC-EE instructional model (6Cs).

To clarify the pedagogical mechanisms, the 6Cs function as a deliberately sequenced reading-to-writing apprenticeship cycle. The model first builds contextual schema and purpose (C1–C2); then develops analytical inquiry and evidence-use (C3–C4); and finally strengthens transfer, stylistic mastery, and reflective revision (C5–C6). Analytical reading is primarily developed through repeated cycles of questioning, evidence evaluation, and inference using authentic community texts and data, while creative writing is developed through style-based modelling, ideation grounded in local narratives, iterative drafting, audience awareness, and revision linked to real community communication purposes (e.g., proposals, promotional narratives, reflective stories, and reports).

- 4.

- Assessment and Evaluation

The CEC-EE model uses formative and summative assessment. Formative checks occur throughout via lesson activity sheets, tracking Grade 12 learning achievement and ELSs (analytical reading and creative writing). A summative assessment at the end tests academic achievement and ELSs. Together, these monitor both process and outcomes for a comprehensive view of progress and skill development.

Five external experts evaluated the CEC-EE model using MacMillan and Schumacher’s [43] four criteria, i.e., propriety, accuracy, feasibility, and utility—on a 5-point rubric. Ratings were high across domains (means, 4.40–4.70; SD, 0.20–0.35), indicating the model was appropriate, accurate, feasible, and useful. Experts advised refining inquiry prompts in Step C3 (Clarify problems) and adding ELS exemplars to aid implementation; these were incorporated. The finalized teaching unit comprises five lesson plans totaling 29 instructional hours (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The CEC-EE teaching unit.

To strengthen implementation consistency, we developed a standardized CEC-EE intervention protocol specifying lesson objectives, required materials, activity sequence, time allocation, and assessment procedures for each of the five lesson plans (total 29 h). The protocol included (a) teacher scripts for key prompts aligned to each 6C step, (b) student worksheets and evidence-collection templates, (c) exemplar texts and genre-based rubrics for analytical reading and creative writing, and (d) minimum required outputs per lesson. The intervention was implemented by the first author, who is Thai-language teacher responsible for the intact class.

Data analysis assessed students’ academic achievement, analytical reading, and creative writing via two-tailed paired t-tests (pre–post), reporting Cohen’s dz and 95% CIs. Lesson-level mastery was tested against a 70% benchmark with one-sample t-tests.

3.3. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (MU-CIRB), Faculty of Medicine, Salaya, Nakhon Pathom (Approval No. MU-CIRB 2024/179.0207; 2 July 2024). All procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki and Thai regulations.

4. Results

The results of this study are divided into two sections, according to two loops of R&D.

4.1. Current Conditions, Challenges, and Needs of CEC-EE Instruction

Thai-language teachers’ perspectives on current conditions, challenges, and needs of CEC-EE instruction:

From the questionnaire analysis, it was found that, overall, Thai-language teachers reported their opinions at a high level across all domains: current conditions (M = 4.38, SD = 0.676), challenges (M = 4.28, SD = 0.807), and needs (M = 4.13, SD = 0.468). The details are as follows:

Teachers’ opinions regarding current conditions of CEC-EE instruction for Grade 12 students revealed the three most highly rated aspects: (1) schools are well-prepared with physical facilities and learning environments (M = 4.62; SD = 0.636); (2) schools are well-prepared with media and materials to support community-economy, context-based learning (M = 4.59; SD = 0.582); and (3) schools are well-prepared with media and materials to support EE (M = 4.58; SD = 0.538).

Teachers’ opinions on challenges of implementing CEC-EE instruction for Grade 12 students indicated the top three concerns: (1) the outcomes of community-economy, con-text-based learning were not worth the investment (M = 4.62; SD = 0.800); (2) students’ limited potential made them unsuitable for CEC-EE instruction (M = 4.53; SD = 0.762); and (3) the outcomes of EE were not worth the investment (M = 4.51; SD = 0.526).

Teachers’ opinions on needs regarding CEC-EE instruction for Grade 12 students highlighted the three most important aspects: (1) community-economy, context-based learning is appropriate for developing students’ ELSs (M = 4.73; SD = 0.495); (2) teachers want CEC-EE instruction (M = 4.71; SD = 0.482); and (3) CEC-EE instruction is suitable for enhancing students’ academic achievement (M = 4.70; SD = 0.510).

The pattern of high ratings across “current conditions,” alongside equally high ratings for “challenges,” suggests a readiness–risk tension rather than simple endorsement. Teachers perceived strong structural readiness (facilities and materials) yet expressed doubts about cost–benefit and student readiness, indicating that the main perceived barrier is not infrastructure but the anticipated return on instructional investment (time, coordination, supervision, and assessment load). Notably, the highest “needs” ratings emphasize ELSs and academic achievement, implying that teachers are willing to adopt CEC-EE when its outcomes are visible, assessable, and aligned with Thai-language standards, which is an insight that informed the model’s emphasis on analytic reading and creative writing as core outputs.

Qualitative data were gathered via an FGD with 12 Thai-language teachers under the Chiang Rai Secondary Educational Service Area Office. Teachers highlighted six intertwined themes: CEC-EE integrates learning with community resources and household practices; the model is appropriate and accessible, rooted in students’ surroundings, and enables practical, income-generating applications; it promotes clarity and enjoyable, engaging learning; implementation occurred during COVID-19, which shaped organization, environments, and feasibility; it builds students’ cultural awareness, pride, and commitment to preserving local wisdom by linking lessons to indigenous practices; and it depends on authentic, hands-on practice so students apply knowledge in real contexts and form lasting understanding.

4.2. Grade 12 Students’ Perspectives on Current Conditions, Challenges, and Needs of CEC-EE Instruction

Overall, Grade 12 students expressed a high level of opinion across the three domains: current conditions (M = 4.32; SD = 0.545), challenges (M = 4.30; SD = 0.650), and needs (M = 4.28; SD = 0.591). The details are as follows:

With regard to CEC-EE instruction for Grade 12 students, the three highest-rated items were the appropriateness of entrepreneurship education for students (M = 4.83; SD = 0.377); the appropriateness of context-based learning for students (M = 4.66; SD = 0.475); and students’ satisfaction with entrepreneurship education (M = 4.34; SD = 0.558).

The three most frequently reported challenges were the outcomes of EE not being worth the investment (M = 4.54; SD = 0.473); students’ limited potential, making them less suitable for EE (M = 4.50; SD = 0.502); and insufficient school support for context-based learning (M = 4.47; SD = 0.536), the third issue prioritized for resolution by the researcher.

In terms of needs, the three highest-rated items were the usefulness of CEC-EE instruction (M = 4.62; SD = 0.487); the appropriateness of CEC-EE instruction for improving students’ academic achievement (M = 4.60; SD = 0.491); and the appropriateness of CEC-EE instruction for developing students’ ELSs (M = 4.54; SD = 0.579).

Students rated CEC-EE as appropriate and satisfying, but they also reported high perceived challenges, especially doubts about its being “worth the investment” and concerns about readiness. This combination indicates that students differentiate between engagement value (the model feels relevant and enjoyable) and implementation constraints (time, workload, and uneven school support). Importantly, the “needs” results show students expect academic and ELS gains, suggesting that they view the approach as valuable when it leads to measurable improvements, not merely as an activity-based enrichment.

An FGD with Grade 12 students at Mae Chan Witthayakhom School (Chiang Rai Secondary Educational Service Area Office) qualitatively examined the current conditions, challenges, and needs for CEC-EE instruction. We found that CEC-EE instruction integrates knowledge from multiple sources by linking classroom work with community resources and household practices; it is widely seen as accessible because it is rooted in students’ everyday surroundings and can extend to practical, income-generating applications. The model promotes clarity and understanding while making learning engaging and enjoyable. Its adoption during the COVID-19 pandemic shaped teaching conditions and the feasibility of activities. Crucially, CEC-EE cultivates students’ awareness and pride in their communities and supports the preservation of local wisdom by connecting learning to indigenous knowledge and cultural heritage, thereby strengthening both entrepreneurial capacities and local identity.

4.3. Summary of R1

R1 surveys showed strong agreement (means > 4.0) from Thai-language teachers and Grade 12 students on current conditions, challenges, and needs for CEC-EE: teachers cited adequate facilities, media, and materials; students reported appropriateness and satisfaction, while both flagged doubts about cost–benefit, limited entrepreneurial readiness, and insufficient school support. Despite concerns, demand was high due to perceived gains in academic achievement and essential language skills. Qualitative findings echoed this, portraying CEC-EE as accessible, engaging, and culturally relevant, fostering awareness, pride, and stewardship of local wisdom through authentic links to community enterprises and households. These results grounded the model’s design: favorable infrastructure and community context signaled readiness, but challenges required a design demonstrating value, feasibility, and alignment with learner capacity. Needs analysis set objectives to improve Grade 12 analytical reading and creative writing via contextually grounded EE; FGDs led to anchoring lessons in Mae Chan’s economy, student-centered multimodal activities, cultural-heritage content, and experiential, project-based work, which were distilled into the 6Cs—connect, comprehend, clarify, construct, carry over, and conclude with reflection—yielding an evidence-based, context-responsive model addressing accessibility, capacity, hands-on practice, and cultural pride.

The R1 findings provide a coherent explanation for why the CEC-EE model was designed as a structured, evidence-based model rather than an open-ended project. Survey results indicate that both teachers and students perceived high feasibility (resources and appropriateness) yet expressed concerns about cost–benefit, uneven school support, and student readiness. The FGDs clarify this tension: stakeholders valued community-linked learning because it is familiar, culturally meaningful, and practical, but they worried about the workload and logistics required to sustain it. These R1 patterns directly informed design choices in the 6Cs, particularly the emphasis on structured inquiry planning (C3), manageable evidence collection and task sequencing (C4), and reflection/public sharing that makes learning outcomes visible (C6). In other words, the CEC-EE model was intentionally designed to demonstrate value quickly while addressing the feasibility constraints shown in R1.

4.4. Impacts of CEC-EE Model

Grade 12 students’ academic achievement before and after learning with the CEC-EE instructional model is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Paired comparison of Grade 12 students’ academic achievement before and after the CEC-EE unit (n = 32).

Students’ overall academic achievement improved significantly after instruction with the CEC-EE model. A paired-samples t-test indicated that mean posttest scores (M = 37.78; SD = 1.77) were substantially higher than pretest scores (M = 15.19; SD = 3.84), t(31) = 30.75, p < 0.001. The effect size was very large, i.e., Cohen’s d = 5.43, suggesting that the CEC-EE model had a profound positive impact on students’ academic achievement.

The researcher then assessed Grade 12 students’ analytical reading skills before and after CEC-EE instruction; the results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Paired comparison of Grade 12 students’ analytical reading skills before and after the CEC-EE unit (n = 32).

A paired-samples t-test showed analytical reading improved markedly after CEC-EE: posttest (M = 22.50, SD = 0.50) > pretest (M = 14.59, SD = 0.52), t(31) = 29.12, p < 0.001, with an exceptionally large effect (Cohen’s d = 5.15). This indicates that the CEC-EE model substantially enhanced Grade 12 students’ analytical reading in Thai. Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of Grade 12 students’ analytical reading performance across each individual CEC-EE lesson plan.

Table 4.

Grade 12 students’ analytical reading skills in each CEC-EE lesson plan. (n = 32).

The CEC-EE lesson plans significantly improved Grade 12 students’ analytical reading skills, causing them to exceed the 70% benchmark across all instructional plans (p < 0.05).

Subsequently, the researcher evaluated Grade 12 students’ creative-writing skills before and after instruction with the CEC-EE model; the comparative results are detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Paired comparison of Grade 12 students’ creative writing before and after the CEC-EE unit. (n = 32).

A paired-samples t-test showed large gains in creative writing after CEC-EE: posttest M = 28.66 (SD = 0.62) vs. pretest M = 18.88 (SD = 0.77), t(31) = 33.32, p < 0.001; effect size, d = 5.89 (exceptionally large). This indicates that the CEC-EE model markedly enhanced Grade 12 students’ creative writing and higher-order language skills. Table 6 presented Grade 12 students’ creative writing skills across each individual CEC-EE lesson plan.

Table 6.

Grade 12 students’ creative writing skills in each CEC-EE lesson plan. (n = 32).

CEC-EE lesson plans significantly improved Grade 12 creative writing: mean scores on all five lessons exceeded the 70% benchmark (p < 0.05). This threshold was selected as a conservative indicator of competent performance that is meaningfully above minimum passing levels and is consistent with the mastery-learning tradition, where a specified percentage correct is used to determine whether learners have mastered a unit before progressing.

4.5. Summary of R2

The R2 findings revealed that the CEC-EE instructional model had a profound positive impact on Grade 12 students’ academic achievement and ELSs. Students’ overall academic performance improved dramatically, with posttest scores significantly higher than pretest scores, supported by very large effect sizes. Analytical reading skills also increased substantially, as posttest results exceeded the 70% benchmark across all lesson plans, indicating consistent gains in higher-order comprehension and critical thinking. Similarly, students’ creative writing skills improved markedly, with statistically significant differences between pre- and posttests, and all five lesson plans surpassing the 70% threshold. These results demonstrate that the CEC-EE model not only enhanced students’ academic achievement but also effectively developed key ELSs—analytical reading and creative writing—through meaningful, context-based, and integrated learning experiences.

5. Discussion

This study tested a community economy context-based learning model that integrates entrepreneurship education (CEC-EE) into Grade 12 Thai. Students showed substantial gains in academic achievement, analytical reading, and creative writing, with very large effects; performance exceeded benchmarks, and teacher/student satisfaction was high. Embedding Thai instruction in authentic, community-based entrepreneurial contexts enhanced cognitive outcomes, cultural engagement, and motivation.

Findings align with research showing that familiar, real-world contexts deepen understanding in mathematics and science [47]. This study extends such benefits to Thai language and uniquely integrates entrepreneurship, highlighting interdisciplinary gains. This pattern of very large gains is plausible given how the CEC-EE design changed the learning conditions rather than only adding new content. In conventional Thai-language lessons, analytical reading and creative writing can remain abstract and exam-oriented, which limits students’ opportunity to use language for consequential purposes. In contrast, CEC-EE positioned Thai as a tool for real decision-making and public communication in community-enterprise settings. When learners read, evaluate, and write texts that have authentic audiences (teachers, peers, and community stakeholders) and real constraints (feasibility, credibility, and cultural appropriateness), they tend to invest more cognitive effort, monitor meaning more carefully, and revise more strategically, behaviors that are directly linked to gains in comprehension and composition quality. Put simply, the model likely increased both time on task and quality of processing by making language use purposeful, socially visible, and outcome-relevant.

Grounded in Mae Chan’s community economy (e.g., Choui Fong Tea Plantation and OTOP), the model used authentic materials for analysis and composition, boosting engagement, critical reflection, and higher-order language learning. Concretely, the community-enterprise materials functioned as “texts worth reading” and “reasons to write.” For reading, students analyzed real product narratives and enterprise communications, identifying persuasive strategies, implicit assumptions, and cultural values; they then evaluated credibility and alignment with community goals. For writing, students produced parallel texts under constraints (target audience, purpose, ethical claims, and feasibility evidence), which required them to control register, cohesion, and rhetorical structure. This tight coupling of reading-to-write tasks likely reduced the common classroom gap where comprehension activities end at answering questions and writing tasks begin without meaningful sources or purposes. However, challenges still remain: investment demands, limited student readiness, and uneven school support—echoing earlier cautions about resources, teacher preparation, and institutional commitment [48,49], plus concerns about scalability and sustainability across diverse locales.

Although the quantitative findings show very large short-term gains, the qualitative data highlight a clear implementation tension: stakeholders viewed CEC-EE as meaningful and effective, yet they expressed concerns about workload, logistics, student readiness, and sustainability. This is not necessarily a contradiction in results; rather, it suggests that CEC-EE is high-impact but resource- and capacity-intensive, and that outcomes may depend on whether enabling conditions are present. In the FGDs, teachers consistently described the approach as motivating and “making Thai learning real,” but simultaneously emphasized constraints such as time for planning, coordination with enterprises, transport/safety procedures, and assessment load. Students likewise reported enjoyment and clearer purpose for reading and writing, yet noted that fieldwork and open-ended tasks could feel demanding and uneven across group members.

A plausible interpretation is that students benefited because the model increased time on task, feedback, and purposeful language use, even if implementation felt demanding. Teachers’ concerns therefore likely reflect implementation cost, whereas the quantitative outcomes reflect learning benefit within a supported pilot context. This trade-off matters for scalability: without adequate support, the model’s most powerful mechanisms (iterative inquiry, real audiences, and revision cycles) may be reduced to superficial activities (e.g., a one-time trip or simple product description), weakening effects.

The qualitative findings also clarify that “authenticity” and “cultural proximity” are not general features of the model; they operate through identifiable components. Specifically, authenticity is enacted through (a) C1–C2, where local enterprise texts and contexts activate prior knowledge and establish a consequential purpose for reading; (b) C3, where students generate inquiry questions that determine what evidence matters; and (c) C4, where learners engage with real constraints (feasibility, credibility, and stakeholder expectations) that force deeper evaluation of texts and more disciplined writing. Cultural proximity functions primarily in C1–C2 by legitimizing local knowledge and values as academic content, which increases willingness to persist, and in C6 by enabling students to publicly share outputs in culturally meaningful forms (e.g., community-facing narratives, proposals, and presentations). Stakeholders’ concerns indicate that the same components that generate impact, especially C4 authentic investigation and C6 public dissemination/reflection, also increase the burden of coordination and support requirements.

Based on the qualitative concerns, we propose four practical adjustments to preserve effectiveness while improving feasibility. (1) Reduce logistical load while protecting C4’s mechanism: when off-campus fieldwork is limited, use “enterprise evidence packages” (videos, brochures, interviews, product labels, and pricing/market data) and schedule one enterprise interaction (in-person or virtual) as the minimal authentic contact. This retains evidence-based reading and writing without requiring multiple trips. (2) Strengthen student readiness through staged scaffolding (C3 to C4): introduce structured inquiry templates (question stems, evidence checklists, and claim–evidence–reasoning frames) and progressively increase task openness across lessons. This responds to student-readiness concerns while preserving analytical-reading demands. (3) Institutionalize feedback and revision efficiently (C6): use short, rubric-aligned feedback cycles (peer review and teacher comments) and require at least one revision per major text. Teachers reported time pressure; streamlined feedback preserves writing gains without unsustainable workload. (4) Improve equity and group accountability: assign rotating roles (researcher, evidence-checker, writer/editor, and presenter) and include individual accountability components (brief individual reflections, and mini-quizzes on texts) so that group work does not mask uneven participation.

6. Conclusions

This study (R1D1) mapped conditions, challenges, and needs for integrating CEC-EE into Thai-language instruction and (R2D2) estimated its effects on Grade 12 academic achievement and entrepreneurial language skills (analytical reading and creative writing). Teachers and students judged CEC-EE highly appropriate, engaging, and culturally meaningful; structured lesson plans produced very large short-term gains across outcomes. Anchoring learning in authentic community contexts boosted motivation, comprehension, and performance.

Theoretically and practically, the model extends context-based learning by explicitly integrating entrepreneurship into language instruction, aligning academics with real economic practices. Mechanisms of effectiveness, that is, authenticity, cultural proximity, and hands-on practice, cohere with situated learning and transfer. Students found community-linked lessons accessible and meaningful; teachers reported support for both achievement and identity formation, positioning CEC-EE as a culturally responsive route to jointly strengthen academic and entrepreneurial capacities.

CEC-EE contributes a distinct integration logic that differs from three common strands in the literature. First, unlike general CBL that situates academic tasks in local themes without specifying an applied competency domain, CEC-EE operationalizes context through a community-economy lens and explicitly targets entrepreneurship competencies (opportunity recognition, value creation, and stakeholder reasoning) within Thai-language standards. Second, unlike EE programs that are often delivered as stand-alone modules, extracurricular projects, or business-track initiatives, CEC-EE embeds entrepreneurship inside a core subject (Thai language) and makes it assessable through discipline-relevant outcomes, as analytical reading and creative writing, rather than treating language as an ancillary skill. Third, unlike generic project-based learning, the 6Cs specify a reading-to-writing mechanism: learners move from contextual schema-building (C1–C2) to evidence-driven inquiry (C3–C4), and then to transfer and revision for real audiences (C5–C6). This sequencing clarifies how ELSs develop (genre control, persuasion, negotiation, and evidence use) and explains why the model yields gains in both comprehension and production.

There are four enabling conditions for successful implementation of CEC-EE model: (1) partnership readiness, at least one accessible community enterprise or learning site willing to provide information, texts, and authentic audiences for student communication products; (2) logistical feasibility, protected time for fieldwork or equivalent community interaction (on-site or virtual), with transport/safety arrangements and a modest operational budget; (3) instructional capacity, a teacher team (or one trained teacher) able to enact genre-based reading-to-writing cycles, manage mixed-ability inquiry groups, and provide iterative feedback and reflection; and (4) institutional support and alignment, administrative approval for off-campus learning (or sanctioned alternatives), assessment alignment with curriculum standards, and scheduled opportunities for public dissemination (school showcases, community presentations, and digital exhibitions). Where these conditions are weak, e.g., remote areas with limited enterprises, high safety constraints, or minimal school support, the CEC-EE model should be implemented through resource-sensitive adaptations (school-based micro-enterprises, case-based enterprise datasets, and virtual stakeholder interviews) while preserving the core mechanism of authentic purpose plus evidence-based reading-to-writing cycles.

However, several challenges remain, including perceived cost–benefit concerns, logistical demands, limited school support, and feasibility for sustained use. Methodological limits (one-group pre–post design, single site, possible ceiling effects, and a 70% mastery benchmark needing validation) temper causal claims and generalizability. Going forward, conditional scaling is warranted where community partnerships and logistics are strong. Policy should fund protected fieldwork time, formal enterprise linkages, and budgets for community-based learning. Future studies should use quasi-experimental or randomized, multi-site designs with longitudinal follow-up and cost-effectiveness analyses to assess durability and broader impact. Overall, CEC-EE aligns Thai-language learning with local economies, raising achievement while cultivating pride, identity, and entrepreneurial vision.

7. Recommendations

Successful CEC-EE implementation requires coordinated action by teachers, administrators, and policymakers: teachers should adapt the model across subjects, integrate local resources, and build analytical reading and creative writing through authentic, hands-on tasks; involve students in selecting learning sites to boost ownership and motivation; and link fieldwork to class via structured reflection and public dissemination of outputs. Schools must provide logistics—time, budget, and safety—for off-campus learning and create venues for sharing work with peers, parents, and local stakeholders. Administrators should forge partnerships with community enterprises, fund transportation and supervision, and institutionalize recognition for student and teacher achievements, while Supervisors and Educational Service Area Offices issue guidelines, ensure curriculum alignment, and build networks of community learning sites. At the policy level, the Basic Education Commission should formalize school–enterprise partnerships, set quality standards for learning sites, and resource regional scaling of community-based entrepreneurship education.

Future research should test CEC-EE beyond a single site and cohort to assess transferability, using larger samples across regions, school types, and grade levels, and involving parents, community members, and even tourists to examine broader stakeholder effects; it should also explore model variations across educational contexts to gauge adaptability. Methodologically, more rigorous designs—randomized controlled or matched-comparison trials—are needed to strengthen causal inference, alongside longitudinal tracking to assess durability of gains in academic achievement and entrepreneurial language skills. Instruments should be refined to avoid ceiling effects, align with national standards, and capture both cognitive and socio-emotional outcomes, and cost-effectiveness analyses should weigh the model’s logistical demands against its benefits.

8. Limitations

This pre-experimental, no-comparison design leaves alternative explanations (history, maturation, testing, regression, and Hawthorne) plausible. Small samples limit precision/power, so p-values are exploratory; emphasis should be on effect sizes and confidence intervals. Single-site implementation and context dependence constrain external validity, warranting cautious generalization. Outcomes focus on short-term cognitive/instructional gains, omitting behavioral and community-level measures crucial for sustainability. Future work should use quasi-experimental or randomized, multi-site designs and longitudinal follow-up. Overall, CEC-EE is a promising, context-responsive pathway that improves language achievement while fostering entrepreneurial awareness, cultural pride, and community connection; scaling will require attention to cost-effectiveness and adaptation to varied school contexts.

Additional limitation is that the observed gains may partly reflect novelty effects, where students’ motivation and performance improve temporarily because the learning experience is new, socially engaging, and receives heightened attention during an intervention period. In this study, CEC-EE introduced unfamiliar features which could elevate engagement beyond what would be sustained under routine implementation. Although the pattern of improvements across multiple outcomes suggests substantive learning, future studies should incorporate comparison conditions with equivalent teacher attention and instructional time, measure student engagement longitudinally, and include delayed posttests to determine whether effects persist once the novelty diminishes.

Also, the 6Cs model depends on access to viable community-economy contexts and partnerships. Areas with limited enterprises, constrained transportation budgets, safety restrictions, or low institutional capacity may struggle to implement C4 (authentic investigation) and C6 (public dissemination) as originally designed. Thus, generalizability may be bounded by local resource availability and partnership strength. To address this constraint, future work should test low-resource adaptations such as school-based micro-enterprises, simulated community cases using multimedia datasets, virtual enterprise interviews, and regional/shared partnerships coordinated by Educational Service Area Offices, while monitoring whether these adaptations preserve the model’s core mechanism, i.e., authentic purpose, evidence-based reading-to-writing, and iterative feedback.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.W. and K.B.; methodology, K.B.; software, P.W.; validation, P.W.; formal analysis, P.W. and K.B.; investigation, P.W.; resources, P.W.; data curation, P.W., K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, P.W.; writing—review and editing, K.B.; visualization, P.W.; supervision, K.B.; project administration, P.W.; funding acquisition, K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project has been funded by Mahidol University (Fundamental Fund: fiscal year 2024 by National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF)).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (MU-CIRB), Salaya, Nakhon Pathom, approval number COA. No. MU-CIRB 2024/179.0207, date of approval 2 July 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jirutthitikan Pimvichai, Institute for Innovative Learning, Mahidol University, for her valuable contributions to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EE | entrepreneurship education |

| CEC | community economy context-based learning |

| CEC-EE | community economy context-based learning integrating entrepreneurship education |

Appendix A. Interview Questions on Current Conditions, Challenges, and Needs of CEC-EE Instruction

Appendix A.1. Current Condition

- 1.

- Please describe your experience with context-based learning (CBL) and/or entrepreneurship education (EE). How long have you implemented these approaches, and what motivated or triggered your initial adoption (e.g., policy, school goals, training, local community needs, and personal interest)?

- 2.

- In your view, is CBL and/or EE suitable for your students and your school context? Why or why not? (Probe: student readiness, school culture, community resources, time, and curriculum alignment.)

- 3.

- What aspects of CBL and/or EE have you found most impressive or satisfying? Why? (Probe: student engagement, learning outcomes, real-world relevance, teacher collaboration, and community partnership.)

Appendix A.2. Challenges

- 4.

- What major challenges or barriers have you encountered in implementing CBL and/or EE that could hinder success? (Probe: teacher workload, assessment, student differences, resources/budget, administrative support, community coordination, and sustainability.)

Appendix A.3. Needs

- 5.

- Do you think CEC-EE instruction should be continued or expanded (in your classroom, school, and at the national level in Thailand)? Why and how? (Probe: priority levels, what “expansion” would look like, and conditions for scaling.)

- 6.

- What recommendations do you have to improve CEC-EE Instruction to make it more effective and sustainable? (Probe: professional development, lesson design supports, partnerships, assessment tools, and policy/administrative actions.)

References

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB). The Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017–2021); Office of the Prime Minister: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017. Available online: https://backoffice.onec.go.th/uploaded2/Category/202110/nesdbplan12.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2026).

- Secretariat of the Prime Minister. Pracharath Mechanism and the Twenty-Year National Strategy: Thailand 4.0 Implementation; Secretariat of the Prime Minister: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017.

- World Bank. Thailand Economic Monitor February 2025: Unleashing Growth-Innovation, SMEs and Startups; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Educating the Next Wave of Entrepreneurs: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Capabilities to Meet the Global Challenges of the 21st Century; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Thailand. Monetary Policy Report Q3/2025: Box 3—Business and Financial Conditions of SMEs; Bank of Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. The Basic Education Core Curriculum B.E. 2551 (A.D. 2008); Office of the Basic Education Commission: Bangkok, Thailand, 2008.

- Office of the Basic Education Commission. Education for All 2015 National Review: Thailand; Office of the Basic Education Commission: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015.

- Kaewsaensai, K.; Kijkuakul, S. Development of context-based learning guideline in the topic probability of Grade 10 students. J. Yala Rajabhat Univ. 2021, 16, 42–51. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Faculty of Business Administration, Chiang Mai University. B.B.A. Program in Business Management [Curriculum Document]; Chiang Mai University: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2013; Available online: https://www.cmubs.cmu.ac.th/en/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Nuansri, M.; Pantuworakul, K. Effects on developing the curriculum for incubating graduates to possess skills as a new generation of entrepreneurs. J. Educ. Stud. 2020, 14, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Suksomwat, C.; Wongwanich, S.; Piromsombat, C. Instructional guidelines to enhance students’ entrepreneurship: Crowdsourcing. Online J. Educ. 2020, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Education Council. Research Report: Education Provision for Entrepreneurship Education; Office of the Education Council: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018.

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, 2nd ed.; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. A Postcapitalist Politics; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, M.; Flora, C. Spiraling-up: Mapping community transformation with community capitals framework. Community Dev. 2006, 37, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M.; McKinley, S. Cities Building Community Wealth; The Democracy Collaborative: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: http://marjoriekelly.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CitiesBuildingCommunityWealth-Web.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Tosophon, S.; Kaewurai, W. An Entrepreneurship Curriculum Development to Enhance Entrepreneurship Competence Based on Cognitive Apprenticeship Approach for the Higher Vocational Certificate Students. J. Educ. Innov. 2020, 22, 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, M.K.; Singh, S.K. Entrepreneurship education: Concept, characteristics and implications for teacher education. Shaikshik Parisamvad 2015, 5, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ememe, O.N.; Ezeh, S.C.; Ekemezie, C.A. The role of head-teacher in the development of entrepreneurship education in primary schools. Acad. Res. Int. 2013, 4, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Crosina, E.; Frey, E.; Corbett, A.C.; Greenberg, D. From negative emotions to entrepreneurial mindset: A model of learning through experiential entrepreneurship education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2024, 23, 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.; Wu, W.; Moberg, K.; Singer, S.; Gabriel, B.; Valente, R.; Carlos, C.; Fannin, N. Exploring inclusivity in entrepreneurship education provision: A European study. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2024, 22, e00494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarelli, M.; Bongiorno, G. Is it the time to reshape entrepreneurship education? State-of-the-art and further perspectives. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Entrepreneurship Education at School in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016.

- Johansen, V.; Schanke, T. Entrepreneurship education in secondary education and training. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 57, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-amnonkul, P. Research and development of junior entrepreneur curriculum based on cognitive apprenticeships approach to enhance business competence of upper secondary school students. Silpakorn Educ. Res. J. 2010, 2, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Instructional Management for Learners in the Thailand 4.0 Era; Cooperative League of Thailand Printing House: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018.

- Smolka, K.M.; Geradts, T.H.J.; van der Zwan, P.W.; Rauch, A. Why bother teaching entrepreneurship? A field quasi-experiment on the behavioral outcomes of compulsory entrepreneurship education. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 2396–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M.; Swain, M. Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Appl. Linguist. 1980, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K. Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2007, 16, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley-Evans, T.; St John, M.J. Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, D.; Hood, P.; Marsh, D. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah, N.; Kiany, G.R.; Tajeddin, Z. Exploring the effect of an entrepreneurship awareness-raising intervention on ELT learners’ entrepreneurial intention, mindset, self-efficacy and outcome expectations. Lang. Teach. Res. Q. 2022, 27, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Palanques, V. Teaching elevator pitch presentations through a multimodal lens. TESOL J. 2024, 15, e769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvapalle, S.G.; Phillips, N.; Cornelissen, J.P. Entrepreneurial pitching: A critical review and integrative framework. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2024, 18, 550–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, J.J.; McSweeney, K.T.; Allison, T.H.; Anglin, A.H. The entrepreneurial pitching process: A systematic review using topic modeling and future research agenda. J. Bus. Ventur. 2025, 40, 106519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education: A Conceptual Introduction, 5th ed.; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz-Gibbon, C.T.; Morris, L.L. How to Design a Program Evaluation, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Stanley, J.C. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ekaphan, P.; Thongmoon, M. The Development of Mathematical Literacy for Matthayomsuksa 5 Students in Graph Theory Section Using Context-Based Learning. Master’s Thesis, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham, Thailand, 2020. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Kudhom, P.; Jomhongbhibhat, B.; Boonchai, P. The development of enrichment curriculum using metacognition and context-based learning to enhance mathematical skills and processes of Grade 11 students. J. Grad. Sch. Pitchayatat 2019, 14, 91–98. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Kumpiro, P.; Gumjudpai, S.; Chomnankit, P. Development of an enrichment curriculum according to the concepts of context-based learning through the use of problem-based learning for enhancing mathematical skills and processes for sixth grade students. J. Grad. Sch. Pitchayatat 2018, 13, 127–135. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.