Multi-Source Joint Water Allocation and Route Interconnection Under Low-Flow Conditions: An IMWA-IRRS Framework for the Yellow River Water Supply Region Within Water Network Layout

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- Building a water resource allocation model that considers multiple routes and multiple water sources

- (b)

- Conducting water diversion and regulation under different low-flow scenarios of the Yellow River for the mutual support of the Eastern, Middle, and Western Routes of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project.

2. Description of the Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the IMWA-IRRS Model

3.2. The Main Principle of the Model

3.2.1. Spatial Allocation of Water Demand Data

- (1)

- The readsubcty_resd subroutine identifies CUs belonging to the provincial administrative division. Based on the construction land area and farmland area within each CU, it accumulatively calculates the total construction land area and farmland area of the provincial administrative division, computes the area proportions of construction land and farmland for each CU, and transmits the data to the wdemd subroutine for subsequent processing.

- (2)

- The wdemd subroutine identifies the included CUs in the provincial administrative division. According to the proportions of construction land area and farmland area in each CU, it distributes the water demand data to each CU.

3.2.2. Cyclic Simulation of Managed Water Flow

3.2.3. Priority Calculation of Water Use and Water Supply

3.2.4. Optimization Method

- ➀

- Define boundary conditions and invoke the process subroutine to construct the optimization framework.

- ➁

- During the coordination layer computation phase, global strategies are formulated according to the correlation among sub-objectives to approximate global optimality; subsequently, each subsystem executes parallel local optimization and feeds back results to the subsequent phase.

- ➂

- In the parameter updating phase, optimization outcomes are integrated to iteratively recalibrate coordination variables and compute the global objective function.

- ➃

- Iteration termination criteria are determined based on predefined optimization iterations and convergence thresholds, ultimately outputting the system’s optimal solution.

- (1)

- Objective function

- ➀

- Water deficit index

- ➁

- Equity index

- (2)

- Constraints

- ➀

- Reservoir storage capacity

- ➁

- Ecological flow requirements

- ➂

- Water demand satisfaction

- ➃

- Water transfer capacity

- ➄

- Hydraulic capacity of water networks

- ➅

- Channel water conveyance loss

3.3. Data and Model Setup

3.3.1. Data

- Water resources data

- (1)

- Runoff data: Long-term monthly natural and measured runoff data from 1978 to 2016 for 15 hydrological stations along the main stem and major tributaries of the Yellow River, including Tangnaihai, Lanzhou, Shizuishan, Huayuankou, Lijin, Minhe, Hengtang, Hongqi, Wenjiachuan, Baijiachuan, Zhangjiashan, Huaxian, Heishiguan, Wushe, and Daicunba, were provided by the Yellow River Conservancy Commission.

- (2)

- Water diversion project data:

- (a)

- Adjustable water volumes for the Eastern, Middle, and Western Routes of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project and the Hanjiang-to-Weihe River Water Diversion Project for 2035.

- (b)

- Key hydraulic parameters of water diversion channels, including flow capacity and length.

- (c)

- Projected 2035 water demand, exploitable groundwater capacity, and unconventional water utilization potential in the Yellow River Basin and its water supply areas.

- (d)

- Ecological guarantee flow rates at key sections of the Yellow River.

- 2.

- Water consumption and supply data

- (1)

- Water supply data: Annual water supply data from 1998 to 2016 for various sources, including surface water, groundwater, unconventional water, and transferred water, in the 85 prefecture-level administrative regions.

Unconventional water refers to water resources that can be utilized after treatment or directly used under certain conditions. In this study area, unconventional water includes reclaimed water, harvested rainwater, brackish water, and mine water.- (2)

- Water consumption data:

- (a)

- Annual water consumption data from 1998 to 2016 for domestic, ecological, industrial, and agricultural sectors across 85 prefecture-level administrative regions within the Yellow River Basin and its water supply areas.

- (b)

- Water consumption rates for various sectors in the Yellow River Basin and its water supply areas.

3.3.2. Model Setup

- (1)

- Generalization of water network systems

- (2)

- Computational unit division

3.3.3. Model Comparison

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance

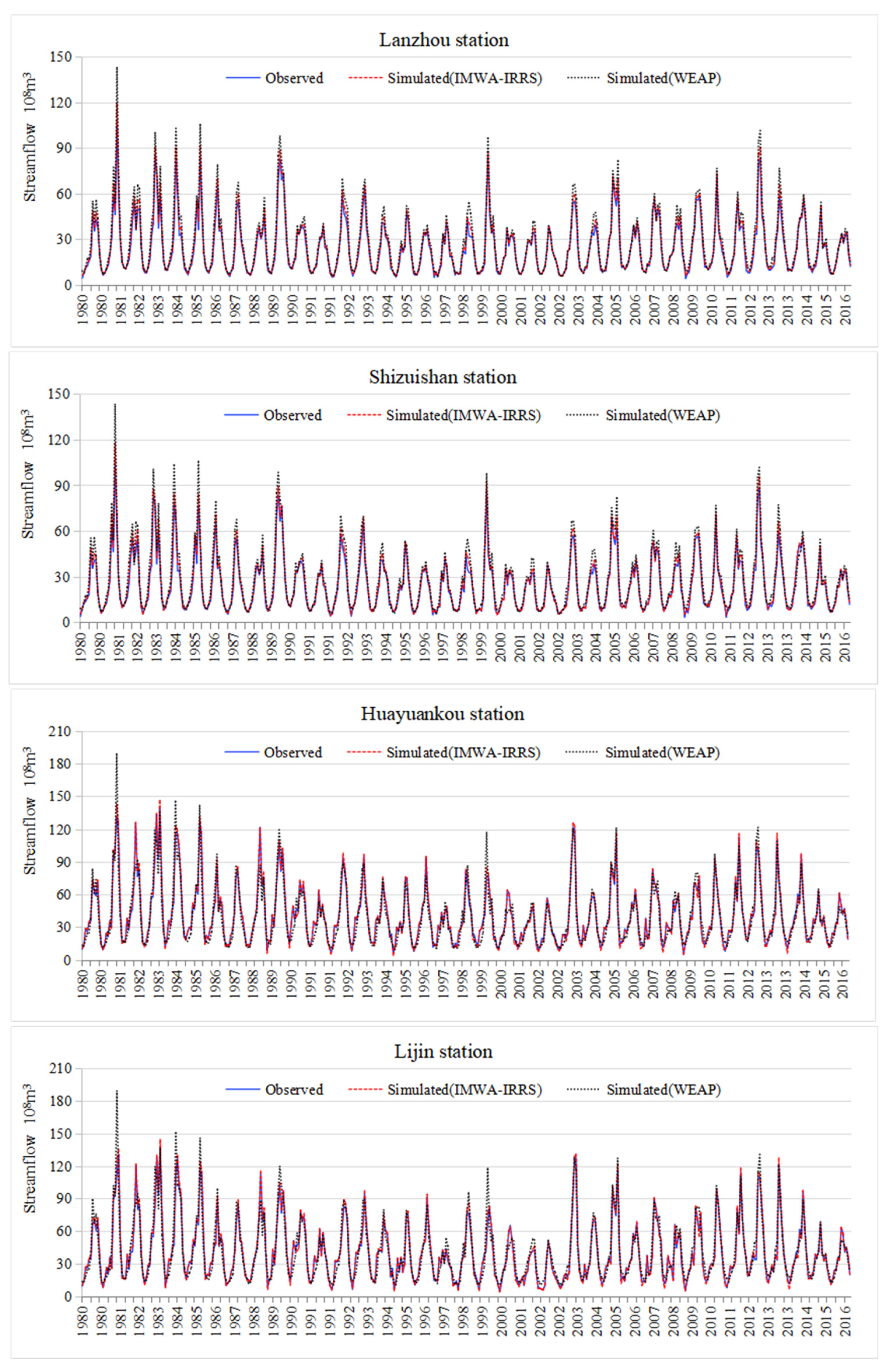

4.1.1. Natural Runoff Process

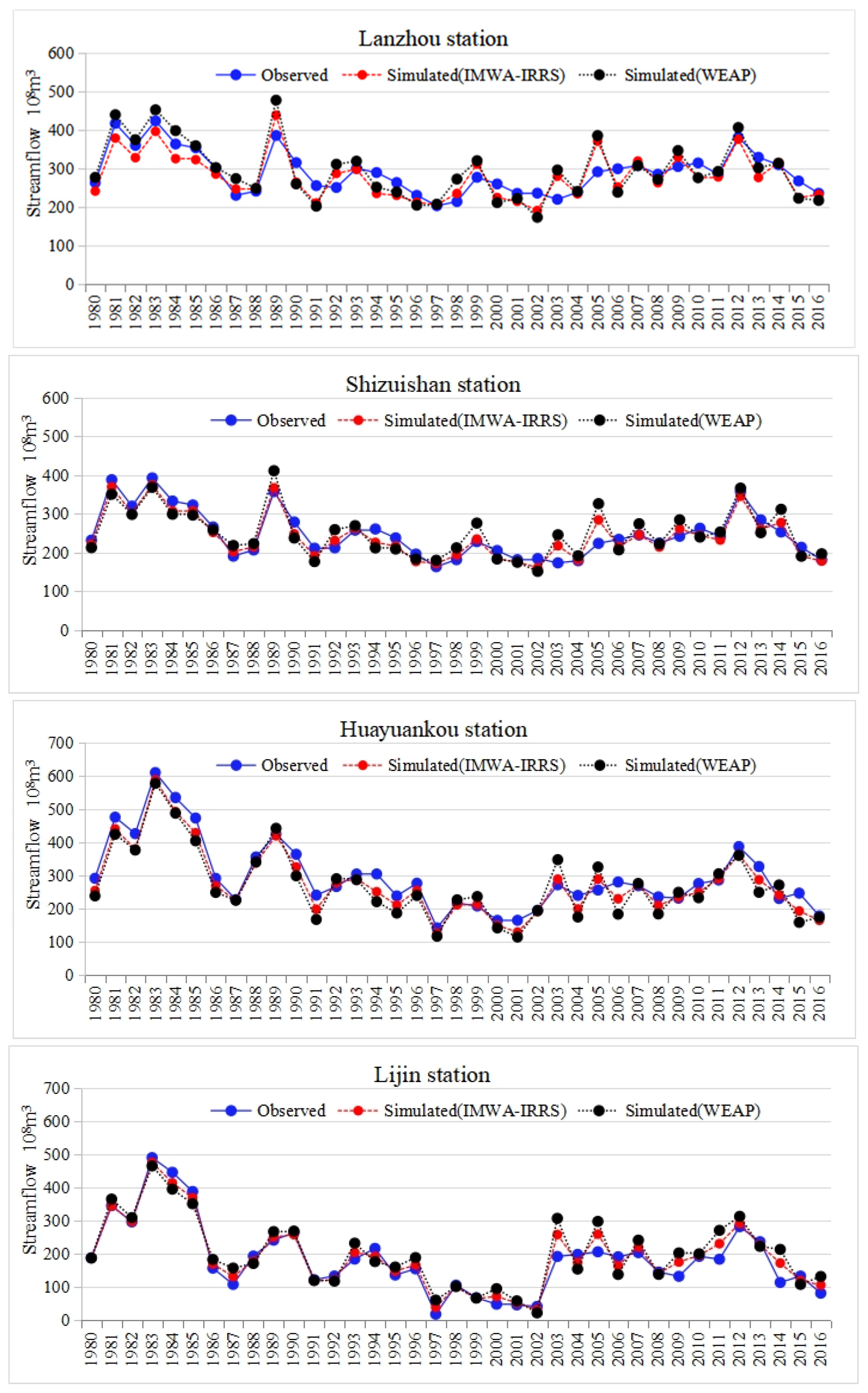

4.1.2. Human-Impacted Runoff Process

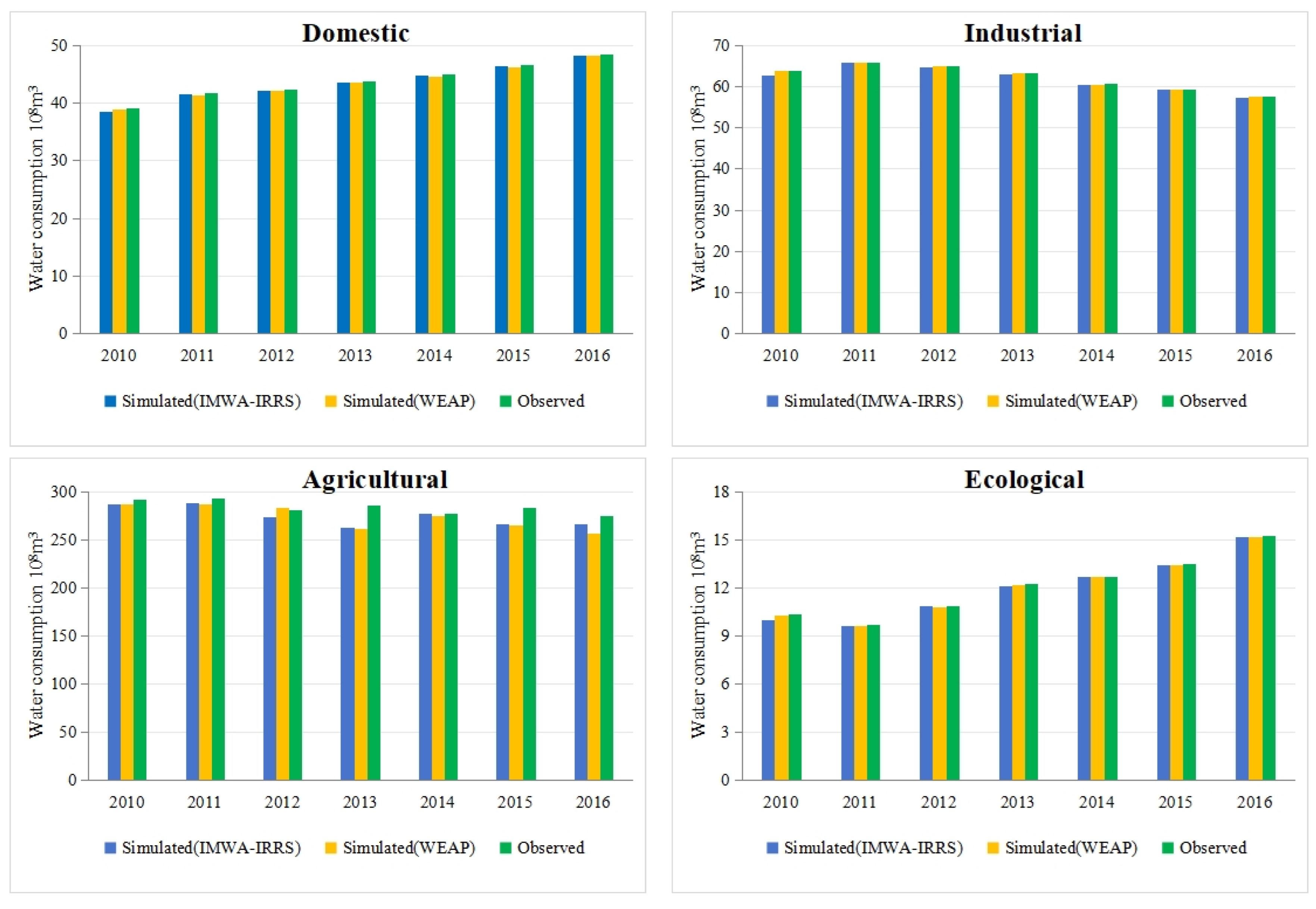

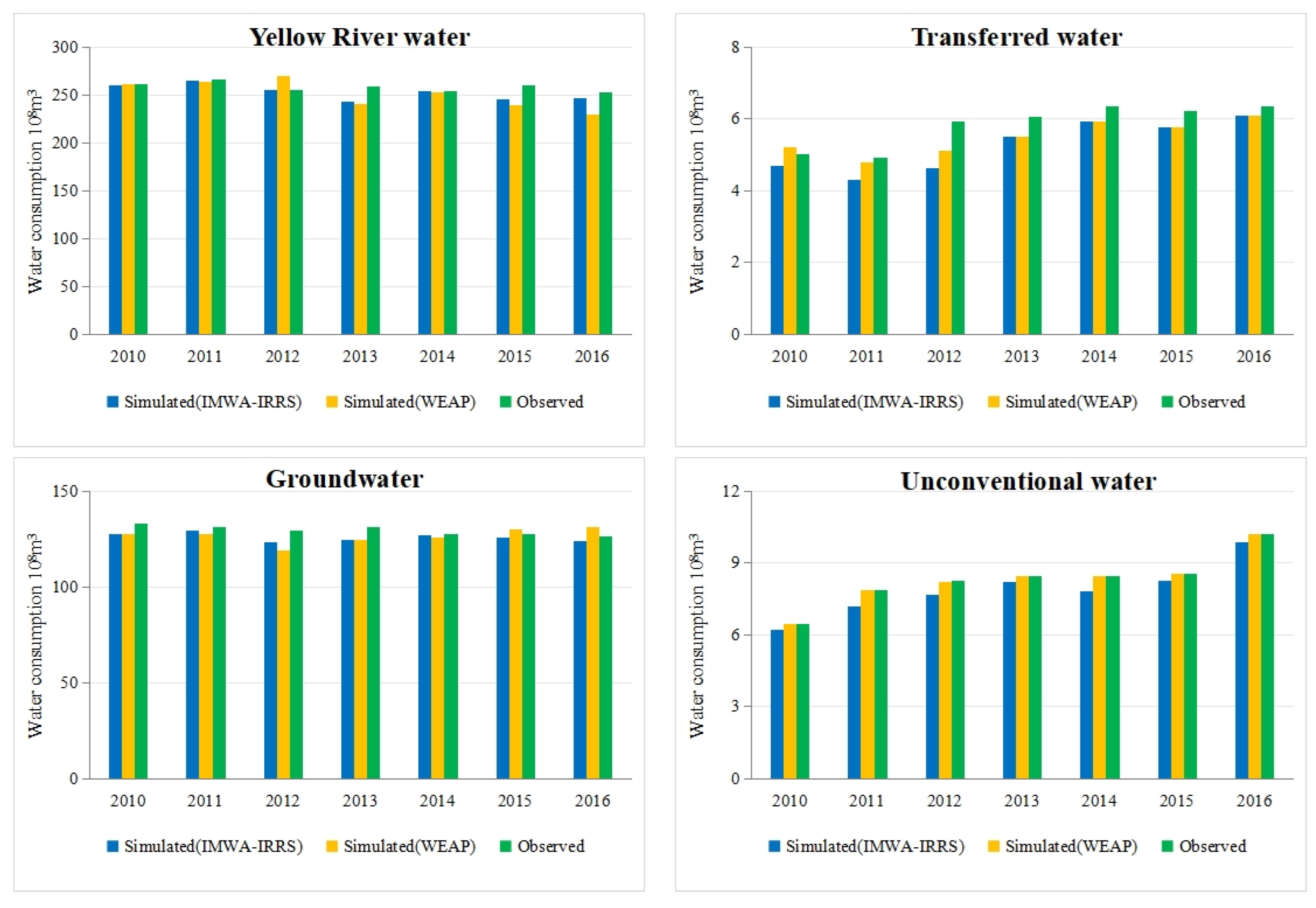

4.1.3. Water Consumption and Water Supply

4.2. Multi-Source and Multi-Route Allocation Under Low-Flow Conditions

4.2.1. 75% Low-Flow Condition

4.2.2. 95% Low-Flow Condition

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Advantages of IMWA-IRRS

5.2. Limitations and Future Improvements

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The IMWA-IRRS model characterizes the spatiotemporal dynamics of multi-source water, including local surface water, groundwater, inter-basin transfers, and unconventional water, while explicitly describing water network topology and transmission relationships between sources and users. By integrating simulation and optimal allocation, it realistically reflects network regulation, a strength that is rooted in its macroscopic rule-based framework, simulation accuracy, and applicability to regional water allocation planning, thereby serving as a powerful tool for the refined management of complex water systems.

- (2)

- Multi-criteria calibration of natural and human-impacted runoff, water consumption, and water supply using R, Ens, and PBIAS demonstrated excellent performance: monthly runoff simulations during both the calibration and validation periods achieved R > 0.98, Ens > 0.98, and PBIAS within ±10%; human-impacted runoff R > 0.8, PBIAS ± 10%; sectoral water consumption PBIAS < 5%; source-specific water supply PBIAS < 10%. These validate IMWA-IRRS’s excellent predictive performance in the Yellow River water supply region.

- (3)

- The IMWA-IRRS model exhibits comparable simulation performance to the WEAP model in terms of natural runoff, human-impacted runoff, and water consumption and water supply simulations. For natural runoff during validation periods, IMWA-IRRS achieved an Ens of 0.99, an R of 1.0, and a PBIAS of 2.09%, compared with WEAP’s Ens of 0.94, R of 0.98, and PBIAS of 5.68%. In human-impacted flow simulations, IMWA-IRRS produced an R of 0.79 and a PBIAS of 1.03%, compared with WEAP’s 0.73 and −1.38%. For water consumption and water supply, the PBIAS was 2.53% for IMWA-IRRS versus 2.65% for WEAP. These results confirm the comparable performance of the two models, validating the applicability of IMWA-IRRS.

- (4)

- The proposed 2035 water resource allocation scheme integrates water transfers from the Yangtze to the Yellow River. Under 75% low-flow conditions, total supply reaches 59.691 billion m3 with a shortage of 3.462 billion m3. Under 95% low-flow conditions, supply is 58.746 billion m3 with the shortage increasing to 4.407 billion m3. However, limited coverage of the Middle and Eastern Routes of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project poses uncertainties to regional water security. Therefore, future efforts should prioritize expanding the coverage of these two routes to enhance inter-route complementarity, while simultaneously reducing the local water demand to improve regional water security capacity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ma, C.; Wang, H. Driving factors and regulation strategies for resilience of water resources system in the Yellow River Basin. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2025, 56, 1253–1266. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Zuo, D.; Xu, Z.; Wang, G.; Han, Y.; Peng, D.; Pang, B.; Abbaspour, K.; Yang, H. Changes in water conservation and possible causes in the Yellow River Basin of China during the recent four decades. J. Hydrol. 2024, 637, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Zheng, X. Key scientific issues of water allocation plan optimization and comprehensive operation for Yellow River basin. Adv. Water Sci. 2018, 29, 614–624. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K. Study on the dynamic prediction and optimum regulation scheme of water resource carrying capacity in the yellow river basin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lu, Z.; Yan, D.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; Ma, Q. Assessing spatiotemporal dynamics of water and land resources matching under dynamic environmental conditions in the Yellow River basin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 525, 146498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Zheng, X. Study on the propagation law of meteorological drought to hydrological drought under variable time Scale: An example from the Yellow River Water Supply Area in Henan. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zheng, X.; Yan, D.; Shang, W. New situation and countermeasures of water resources supply and demand in the Yellow River Basin. China Water Resour. 2021, 18–20+26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Rosegrant, M.W. Optional water development strategies for the Yellow River Basin: Balancing agricultural and ecological water demands. Water Resour. Res. 2004, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H.; Liu, J.J.; Yan, Z.Q.; Wang, H.; Jia, Y. Attribution analysis of the natural runoff evolution in the Yellow River basin. Adv. Water Sci. 2022, 33, 27–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Son, K.; Hung, F.; Tidwell, V. Impact of climate change on adaptive management decisions in the face of water scarcity. J. Hydrol. 2020, 588, 125015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.; Elagib, N.A.; Zhuguo, M.; Saleem, F.; Mohammed, A. Water scarcity in the Yellow River Basin under future climate change and human activities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Su, F.; Yang, D.; Tong, K.; Hao, Z. Impacts of recent climate change on the hydrology in the source region of the Yellow River basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2016, 6, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, X. Identification of Continuous Low Water Period in the Yellow River’s Centennial Runoff Series and Analysis of Water Use Characteristics. Yellow River 2024, 46, 20–25+42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, W. Evolution of Water and Sediment Situation in the Middle and Lower Reaches of Yellow River in Recent 50 Years and Analysis of Its Influencing Factors. Water Power 2020, 46, 48–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Shang, W.; Zhou, X.; Lv, H.; Song, Y. Study on water resources security gurantee strategies for the Yellow River Basin during extreme water scarcity year. China Water Resour. 2024, 55–59+77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y. Preliminary study on harnessing strategies for Yellow River in the new period. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2019, 50, 1291–1298. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Qiao, L.; Sun, S. Spatial distribution and dynamic change of water use efficiency in the Yellow River Basin. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 57–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, G. Ecological water demand in the lower Yellow River and its estimation. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2002, 595–602. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Tian, W.; Xie, J. Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development of the Yellow River Basin Urgently need to Solve the Water Shortage Problem. Yellow River 2020, 42, 6–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Tang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Water scarcity under various socio-economic pathways and its potential effects on food production in the Yellow River Basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshid Mousavi, S.; Anzab, N.R.; Asl-Rousta, B.; Kim, J.H. Multi-objective optimization-simulation for reliability-based inter-basin water allocation. Water Resour. Manag. 2017, 31, 3445–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Peng, S.; Li, K. Study on the Joint Operation of Key Reservoirs to Cope with Drought in the Yellow River Main Stream. Yellow River 2019, 41, 31–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hhua, Y.; Cui, B. Environmental flows and its satisfaction degree forecasting in the Yellow River. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 92, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J. Collaboration of national water resources with eco-social system in China. China Water Resour. 2016, 7–9. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- You, J.; Wang, Z.; Gan, H.; Zang, J. Stepwise compensatory allocation of inter-basin water diversion. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2008, 39, 870–876. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Zhou, X.; Wu, J.; Shang, W.; Yan, D. Water allocation scheme optimization in the Yellow River based on incremental dynamic equilibrium configuration. Water Resour. Prot. 2022, 38, 48–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Xia, M.; Zhang, J.; Tan, X.; Yuan, C. A multi-scale multi-objective optimization model for water resources scheduling in complex inter-basin water transfer systems. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 134032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, R. Thoughts and proactive measures for strengthening water resources regulation in the Yellow River Basin. China Water Resour. 2021, 8–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. Assessing the impact of the Central Line Project of South-to-North Water Diversion on urban economic resilience: Evidence from prefecture-level cities in Henan and Hebei provinces. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Peng, S.; Wu, J.; Ming, G.; Zheng, X. Water allocation of the first phase of South-to-North Water Diversion Western Route Project based on balanced provisioning of water resources in the Yellow River basin. Adv. Water Sci. 2023, 34, 336–348. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Fan, L.; Ding, W. Digital Dynamic Capability Model and Practice of Water Resource Scheduling in Water Transfer Project. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 42, 195–204. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Wen, J.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Cai, C. Optimal allocation and dispatching of water resources in reservoir dam cascade system based on IA-PSO. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2023, 54, 60–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Y.; Xu, J.; Xiao, W.; Yang, M.; Hou, B. Development and application of the water amount, quality and efficiency regulation model based on dualistic water cycle. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 51, 1473–1485. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Xu, J.; Sang, L.; Liu, Q. Development and application of the distributed water resources allocation and regulation model based on hydrological cycle. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2022, 53, 456–470. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Xu, J.; Yin, D.; He, S.; Zhu, S.; Li, S. Modified Multi–Source Water Supply Module of the SWAT–WARM Model to Simulate Water Resource Responses under Strong Human Activities in the Tang–Bai River Basin. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ji, C.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Large system decomposition-coordination model for optimal power-generation scheduling of cascade reservoirs. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2015, 34, 40–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Yao, F.; Xu, Z. Optimizing regional irrigation water allocation for multi-stage pumping-water irrigation system based on multi-level optimization-coordination model. J. Hydrol. X 2019, 4, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Hao, M.; Ren, W. Water resources supply and demand balance in Hebei Province based on WEAP model. Water Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, D.; Sieber, J.; Purkey, D.; Lee, A. WEAP21—A demand-,priority-,and preference-driven water planning model. Water Int. 2005, 30, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Qian, T. Improvement of WEAP model considering regional and industrial water distribution priority and its application. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 47, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutiga, J.K.; Mavengno, S.T.; Zhongbo, S.; Woldai, T.; Becht, R. Water allocation as a planning tool to minimise water use conflicts in the upper Ewaso Ng′iro North Basin, Kenya. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 3939–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadded, R.; Nouiri, I.; Alshihabi, O.; Maßmann, J.; Huber, M.; Laghouane, A.; Yahiaoui, H.; Tarhouni, J. A decision support system to manage the groundwater of the Zeuss Koutine Aquifer using the WEAP-MODFLOW framework. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 1981–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouklia-Hassane, R.; Yebdri, D.; Tidjani, A.E. Prospects for a larger integration of the water resources system using WEAP model:a case study of Oran Province. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 5971–5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katirtzidou, M.; Latinopoulos, P. Allocation of surface and subsurface water resources to competing uses under climate changing conditions: A case study in Halkidiki, Greece. Water Sci. Technol.-Water Supply 2018, 18, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, G.; Liu, D.; Guo, H.; Wang, J. Evaluating water supply risk in the middle and lower reaches of Hanjiang River basin based on an integrated optimal water resources allocation model. Water 2016, 8, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, L.; Li, X.; Lin, J.; Kang, J. Simulation of urban water resources in Xiamen based on a WEAP model. Water 2018, 10, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Bai, X.; Khanna, N.Z.; Yi, S.; Hu, Y.; Deng, J.; Gao, H.; Tuo, L.; Xiang, S.; Zhou, N. Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) model application for exploring the water deficit at catchment level in Beijing. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 118, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.; Arnold, J.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module Category | Submodule | Number of Subroutines | Main Subroutines | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main program module | Main | 4 | mainform, allo_parms, information | Initializing program execution and defining array dimensions for model parameters. |

| Simulation | 5 | process, sim_ini, cmd | Conducting annual and monthly time-step simulations of hydrological and allocation processes. | |

| Water allocation | 6 | readsubcty_resd, wdemd, wsupply, walloc, wcsm, wdr | Performing multi-source water allocation calculations based on supply–demand relationships. | |

| River | 7 | river, riverini, rtm, rchwp | Simulating channel routing, river network confluence, and in-stream water delivery. | |

| Water transfer | 3 | outwp, add, minus | Managing cross-basin water diversion and inter-channel flow distribution. | |

| Reservoir | 3 | reservoir, resini, res | Modeling reservoir storage-release dynamics and reservoir-based water supply. | |

| Groundwater | 3 | unit, gwsp, virt | Simulating groundwater extraction using unit response and virtual aquifer methods. | |

| Statistics | 4 | Stats, writem, riverm, output_results | Generating statistical summaries of simulation results and outputting monthly hydrological metrics. | |

| Other | 12 | rewind_ini, unitallo | Supporting auxiliary functions. | |

| Data input module | 15 | readinput, readfile, readsubattr, readsetup, readctywuse | Reading fundamental input data, including runoff, available water transfers, ecological flow requirements, and various allocation and optimization rules, etc. | |

| Optimization module | 6 | analy_gradient, adjust_ratios | Implementing multi-objective optimization algorithms for optimal water allocation strategies. | |

| Model | Hydrological Station | Calibration (1980–2000) | Validation (2001–2016) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBLAS | R | Ens | PBLAS | R | Ens | ||

| IMWA-IRRS | Lanzhou | 6.27% | 1.00 | 0.98 | 4.46% | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| Shizuishan | 6.09% | 1.00 | 0.98 | 3.78% | 1.00 | 0.99 | |

| Huayuankou | 1.72% | 1.00 | 0.99 | −0.35% | 1.00 | 0.99 | |

| Lijin | 2.58% | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.46% | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| WEAP | Lanzhou | 14.50% | 0.99 | 0.91 | 10.58% | 0.99 | 0.94 |

| Shizuishan | 13.79% | 0.98 | 0.90 | 11.66% | 0.98 | 0.93 | |

| Huayuankou | −4.54% | 0.93 | 0.87 | −0.27% | 0.97 | 0.94 | |

| Lijin | 4.22% | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.76% | 0.97 | 0.93 | |

| Model | Hydrological Station | Calibration (1980–2000) | Validation (2001–2016) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBLAS | R | PBLAS | R | ||

| IMWA-IRRS | Lanzhou | −3.18% | 0.89 | 1.34% | 0.71 |

| Shizuishan | 3.59% | 0.97 | 0.51% | 0.82 | |

| Huayuankou | 7.79% | 0.99 | 1.24% | 0.80 | |

| Lijin | 0.02% | 0.99 | 1.04% | 0.83 | |

| WEAP | Lanzhou | 4.36% | 0.89 | 2.35% | 0.72 |

| Shizuishan | 1.95% | 0.89 | −5.60% | 0.74 | |

| Huayuankou | 9.59% | 0.97 | 6.74% | 0.68 | |

| Lijin | −3.14% | 0.98 | −9.00% | 0.79 | |

| Terms | Model | Domestic | Industrial | Agricultural | Ecological | Total Water Consumption |

| Water consumption | IMWA-IRRS | 0.63% | 0.58% | 3.32% | 0.92% | 2.53% |

| WEAP | 0.62% | 0.05% | 3.67% | 0.60% | 2.65% | |

| Terms | Model | Yellow River Water | Transferred Water | Groundwater | Unconventional Water | Total Water Supply |

| Water supply | IMWA-IRRS | 2.16% | 9.65% | 2.78% | 5.12% | 2.53% |

| WEAP | 2.80% | 5.98% | 2.37% | 0.04% | 2.65% |

| Terms | Water Demand (108 m3) | Water Supply (108 m3) | Water Deficit (108 m3) | Water Deficit Rate (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow River | Groundwater | Unconventional Water | Water Diversion | ||||||||

| South-to-North Water Diversion | Han River–Wei River Water Diversion | Total | |||||||||

| Western Route | Middle Route | Eastern Route | |||||||||

| Shanxi | 77.66 | 41.92 | 21.06 | 0.17 | 14.51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.51 | 0 | 0% |

| Nei Monggol | 119.42 | 51.39 | 25.11 | 2.24 | 28.46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28.46 | 12.23 | 10.24% |

| Shandong | 26.41 | 14.91 | 6.17 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 | 5.15 | 0 | 5.33 | 0 | 0% |

| Henan | 75.51 | 47.02 | 20.77 | 0.83 | 0 | 5.31 | 0 | 0 | 5.31 | 1.58 | 2.09% |

| Sichuan | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 1.96% |

| Shaanxi | 93.89 | 49.87 | 25.79 | 0 | 8.24 | 0 | 0 | 10.00 | 18.24 | 0 | 0% |

| Gansu | 53.54 | 33.00 | 5.68 | 3.56 | 7.32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.32 | 3.99 | 7.44% |

| Qinghai | 25.34 | 14.99 | 3.27 | 0.40 | 4.97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.97 | 1.71 | 6.75% |

| Ningxia | 76.07 | 45.79 | 7.68 | 1.34 | 14.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.67 | 6.58 | 8.66% |

| Yellow River Basin | 548.27 | 299.30 | 115.53 | 8.54 | 78.16 | 5.49 | 5.15 | 10.00 | 98.80 | 26.10 | 4.76% |

| Outside the basin | 83.26 | 50.93 | 0 | 0 | 1.84 | 6.87 | 15.10 | 0 | 23.81 | 8.52 | 10.23% |

| Total | 631.53 | 350.23 | 115.53 | 8.54 | 80.00 | 12.36 | 20.25 | 10.00 | 122.61 | 34.62 | 5.48% |

| Terms | Water Demand (108 m3) | Water Supply (108 m3) | Water Deficit (108 m3) | Water Deficit Rate (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow River | Groundwater | Unconventional Water | Water Diversion | ||||||||

| South-to-North Water Diversion | Han River–Wei River Water Diversion | Total | |||||||||

| Western Route | Middle Route | Eastern Route | |||||||||

| Shanxi | 77.66 | 40.23 | 21.06 | 1.86 | 14.51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.51 | 0 | 0% |

| Nei Monggol | 119.42 | 49.68 | 25.11 | 2.24 | 28.46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28.46 | 13.94 | 11.67% |

| Shandong | 26.41 | 11.68 | 9.40 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 | 5.15 | 0 | 5.33 | 0 | 0% |

| Henan | 75.51 | 45.40 | 21.56 | 0.83 | 0 | 5.31 | 0 | 0 | 5.31 | 2.41 | 3.19% |

| Sichuan | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 5.45% |

| Shaanxi | 93.89 | 48.53 | 27.12 | 0 | 8.24 | 0 | 0 | 10.00 | 18.24 | 0.00 | 0% |

| Gansu | 53.54 | 32.54 | 5.68 | 3.56 | 7.32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.32 | 4.45 | 8.31% |

| Qinghai | 25.34 | 14.99 | 3.27 | 0.40 | 4.97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.97 | 1.71 | 6.75% |

| Ningxia | 76.07 | 45.30 | 7.68 | 1.34 | 14.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.67 | 7.08 | 9.30% |

| Yellow River Basin | 548.27 | 288.75 | 120.89 | 10.23 | 78.16 | 5.49 | 5.15 | 10.00 | 98.80 | 29.60 | 5.40% |

| Outside the basin | 83.26 | 44.98 | 0 | 0 | 1.84 | 6.87 | 15.10 | 0 | 23.81 | 14.47 | 17.38% |

| Total | 631.53 | 333.72 | 120.89 | 10.23 | 80.00 | 12.36 | 20.25 | 10.00 | 122.61 | 44.07 | 6.98% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; Li, X.; Song, K.; Ma, R.; Wang, D.; He, J.; Jing, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L. Multi-Source Joint Water Allocation and Route Interconnection Under Low-Flow Conditions: An IMWA-IRRS Framework for the Yellow River Water Supply Region Within Water Network Layout. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031541

Yang M, Li X, Song K, Ma R, Wang D, He J, Jing H, Zhang X, Wang L. Multi-Source Joint Water Allocation and Route Interconnection Under Low-Flow Conditions: An IMWA-IRRS Framework for the Yellow River Water Supply Region Within Water Network Layout. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031541

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Mingzhi, Xinyang Li, Keying Song, Rui Ma, Dong Wang, Jun He, Huan Jing, Xinyi Zhang, and Liang Wang. 2026. "Multi-Source Joint Water Allocation and Route Interconnection Under Low-Flow Conditions: An IMWA-IRRS Framework for the Yellow River Water Supply Region Within Water Network Layout" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031541

APA StyleYang, M., Li, X., Song, K., Ma, R., Wang, D., He, J., Jing, H., Zhang, X., & Wang, L. (2026). Multi-Source Joint Water Allocation and Route Interconnection Under Low-Flow Conditions: An IMWA-IRRS Framework for the Yellow River Water Supply Region Within Water Network Layout. Sustainability, 18(3), 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031541