Abstract

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is a rapidly growing pedagogical model that uses a learner-centered educational approach to address the needs of the 21st century. Relating to the sustainability of teaching, this approach addresses the systematic and complementary learning dimensions (e.g., cognitive, epistemic, and affective) relevant to the evolving needs of students, curricula, and technology. This study uses adaptive management as a theoretical model which views teachers as dynamic learning managers to investigate the integration of IBL in sustainable education targeting Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) (Quality Education). With the participation of 11 physics teachers, this phenomenological study delves into the inquiry-based learning implementation and experiences of physics teachers in building a sustainable learning culture in Türkiye’s public schools. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews to elicit teachers’ perceptions of the sustainability of the inquiry ecosystem, and thematic analysis was utilized to interpret and convey the essence of teaching experiences. The findings reveal that the use of adaptive management mechanisms for IBL reinforces students’ conceptual understanding and the long-term sustainability of teaching practices in physics education. The results also highlight the applicability of adaptive inquiry-based paradigms across disciplinary contexts to offer insights for the integration of new educational technology. This study suggests practical implications for teachers, school leaders, and teacher training programs for sustainable and flexible pedagogies.

1. Introduction

Contemporary educational systems increasingly respond to the complexity, unpredictability, and dynamism of development [1,2]. These global challenges, including technological transformation, call for equity and quality to support a more student-centered approach that provides students with opportunities to engage in deep conceptual and analytical thinking and advanced problem-solving [3,4]. Inquiry-based learning is a teaching methodology that emphasizes an active, participatory, and meaningful approach to knowledge acquisition and fosters an emotional and motivational learning experience in the 21st century [5]. Education is not merely a technical vehicle; it is a vital resource for long-term social, economic, and environmental sustainability [6,7]. This is articulated in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4), which aims to support inclusive, equitable, and quality education as a platform for sustainable development [8]. Sustainable education adapts instruction to students’ needs, curriculum requirements, and context, thereby promoting students’ capabilities in critical thinking, problem-solving, and lifelong learning [9]. However, in science education, content-related instruction remains largely traditional, encompassing curriculum content and procedural problem-solving [10,11]. These practices discourage opportunities for student interaction, sense-making, and adaptation, and raise concerns about their capacity to withstand a rapidly changing world [2]; thus, it is increasingly necessary to think of teaching science as an active practice rather than a series of fixed teaching–learning routines. This demands pedagogy that enables teachers to respond flexibly to their own contexts while remaining consistent with broader educational aspirations [12,13]. In this sense, educational sustainability can be understood as educators’ ability to respond to the instructional process in a responsive and adaptive manner.

Inquiry-based science education supports the construction of sound explanations of natural phenomena through the analysis of evidence, with an emphasis on formulating arguments [14]. IBL stems from constructivist and sociocultural theories of learning, which view learners as more than passive recipients of information [15]. Likewise, science practices describe scientific knowledge in terms of ways of knowing and of working in the world, enabling students to learn to be producers rather than consumers [16]. Inquiry skills involve asking questions and defining problems, planning and designing investigations for data collection and analysis, constructing explanations, and using mathematics and computational thinking [17]. Such genuine practices can provide students with opportunities to develop high-level thinking and metacognition skills, including communication and collaboration, transfer across contexts, and reasoning [18]. IBL connects to learning through competencies in critical thinking, self-direction, collaboration, autonomy, and adaptability, all of which are integral to sustainability education [19,20]. These abilities are essential for equipping learners to navigate an uncertain future. Students’ engagement with science positively increases their motivation and interest in understanding scientific and technological issues in their lives. Physics teachers need to develop expertise in reform-based strategies to understand curricular innovations and integrate scientific inquiry into classroom instruction; however, teachers often face constraints related to curricular demands, assessment conditions, time constraints, and students’ prior experiences with conventional instruction [21]. This has prompted discussions about the need to maintain IBL as a regular course of instruction rather than a unique pedagogical intervention [12,22]. The emergence of IBL as a sustainable pedagogical model may involve examining teachers’ implementation, practice, observation, and adjustments to inquiry-based instruction in response to classroom dynamics.

Using adaptive management as a conceptual lens, this paper examines teachers’ instructional practices to address the challenge of maintaining inquiry-based instruction. The theory of adaptive management comprises four stages of planning, action, observation, and reflection, which can be used to alter the direction of practices within a context [23]. In educational settings, adaptive management offers a rich theoretical model that views teachers as masters of dynamic learning environments. IBL places both high cognitive and pedagogical demands on teachers aiming to navigate students’ diverse ideas and sense-making processes [11,24]. To successfully employ IBL, teachers can engage in learning in the moment, monitor learning, and use evidence to adjust instruction [25], as well as routinely analyze classroom evidence, develop effective instructional strategies, and adjust instruction to individual learning goals [26]. This view aligns with inquiry-oriented pedagogy, which relies on adaptability and responsiveness to students’ emergent thinking. Making teachers adaptive managers positions their professional resourcefulness as the basis for long-term, research-based learning. It aims to examine how teachers navigate uncertainty and make informed pedagogical decisions [27] to adapt to shifting curricular demands, learner needs, and institutional contexts [28].

The empirical literature on the link between inquiry-based learning and adaptive management has been limited, although there is theoretical support for this relationship, particularly in sustainability-oriented education. Building on this gap, the current study explores how physics teachers practice inquiry-based learning through adaptive management, with a focus on teaching and learning practices that ensure sustainability. Bringing these perspectives together in a single study provides greater clarity on how inquiry-based instruction can be embedded and sustained in real classrooms on the path to achieving SDG4 aspirations. The aim of this study is to examine inquiry-based learning (IBL) as a pedagogical practice aligned with adaptive management, situating the teacher as the operator and manager of dynamic learning systems. The study proposes characterizing teacher types and teaching practices for sustainable learning through adaptive management, presents a framework that regards teacher knowledge as a multidimensional construct, and provides a holistic picture of the complex interplay between knowledge, beliefs, context, and pedagogical choices. In line with Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education), this study examines how inquiry-based teaching strategies can contribute to sustainable pedagogical practices in physics education. The following are the study’s guiding questions:

RQ1. How do physics teachers enact inquiry-based learning through adaptive management principles to promote sustainable education?

RQ2. What adaptive teaching practices support or constrain the sustainability of inquiry-based learning in physics classrooms?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Adaptive Management Theory

The theoretical framework of this study centers on adaptive management theory and inquiry-based learning, which describe teaching as the process of planning, action, monitoring, and facilitating sustainable, student-centered instruction. Educational systems involve uncertainty, complexity, and heterogeneity, challenging conventional models of instruction and requiring the maintenance of effective learning over time to become a transformation agent of society [1,12]. For inquiry learning contexts, teachers must dynamically adapt instruction to students’ conceptual understandings, epistemic practices, and sociocultural and material contexts; thus, the teacher is placed between the practitioner role of an instructor and the manager role in the learning process. Learning is seen as an iterative and socially constructed process through disciplinary practices [11,29]. When properly scaffolded by teachers, however, IBL has been strongly correlated with enhanced conceptual understanding, scientific reasoning, and epistemic engagement [19,20]. As researchers have argued, inquiry-based instruction is context-bound, requiring teachers to consistently make teaching decisions according to students’ developing thoughts and affective states, as well as classroom constraints [12,21]. Such features treat inquiry-based teaching as an active rather than a passive approach.

Adaptive management provides a model for understanding teachers’ instructional practices in this complex context, treating decision-making as a circular process in which planning, action, monitoring, reflection, and adaptation operate under conditions of uncertainty [26]. Furthermore, adaptive management aims to learn from practice and adapt over time in response to feedback. As a teaching framework used in general education settings, adaptive management conceptualizes instruction as an ongoing, dynamic process in which teachers use classroom evidence, such as students’ questions, explanations, levels of engagement, and emotions, to adjust their strategies [13,30]. A system manager in management theory is an actor responsible for coordinating resources, regulating processes, and making decisions under uncertainty to accomplish the system’s objectives [31]. In an educational context, a teacher controls both the learning process and the introduction of content. Instruction is a management function that involves making decisions based on feedback from learners and the instructional context. This perspective aims to strengthen education through equity, creativity, lifelong learning, and community action. Aligning with 21st-century skills, new education models aim to create confident and creative individuals who are successful lifelong learners and informed community members [32]. Therefore, teachers become change agents and professional developers of the curriculum and classroom contexts from a sociocultural perspective, ensuring sustainability, coherence, and equity in the learning process [13].

The role of teachers should be not only to impart knowledge but also to manage the dynamics of the educational process through continuous adaptation of pedagogical decisions. Adaptive management provides a practical management framework for teachers in the inquiry-learning ecosystem. It is an approach derived from environmental and organizational management by Holling (1978) [26] that focuses on continuous monitoring, feedback, and iteration through which decision-making occurs under conditions of uncertainty. This approach integrates multiple dimensions of the sustainable inquiry ecosystem, such as conceptual and social understanding, to reduce uncertainty. In this process, teachers, as managers of the learning process, must view an action as an informed experiment rather than a fixed plan [31,33]. They should accommodate management notions and the learning process as a complex, dynamic, and non-linear adaptive system through managerial decisions relying on feedback, such as students’ prior knowledge, epistemic beliefs, and interactional patterns. These decisions are the result of professional judgment, pedagogical content mastery, and continuous learner feedback, in accordance with the teacher’s professional autonomy and management behaviors within adaptive systems for system sustainability [33]. Moreover, adaptive management is focused on the sustainability aspect of the system and sustainability issues related to long-term system viability, resilience, and capacity to learn [34]. In education, sustainability extends beyond environmental content to include the sustainability of learning processes. A sustainable inquiry-based learning ecosystem requires continuous alignment between instructional goals and learner needs, responsiveness to contextual limitations, teacher agency, and professional expertise. When teachers serve as adaptive managers, inquiry-based learning becomes a sustainable management practice.

Combining IBL and adaptive management in this study helps to reveal how inquiry-based instruction is created, enacted, and sustained over time; while IBL defines the pedagogical intention and practice of inquiry, adaptive management describes how teachers can use IBL to guide and sustain inquiry-based instructional practice within an ongoing feedback loop. This integrated perspective is employed not only to inform the research design and ensure that the data inform teachers’ instructional decisions and reflective practices, but also to enable teachers to respond flexibly to inquiry lessons. It also provides an analytical framework by identifying a few conceptual categories for understanding how teachers handle uncertainty, respond to student thinking, and sustain inquiry-based learning across multiple classroom contexts. In summary, this framework aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) because it treats sustainability as an integral part of pedagogy rather than a secondary concern [6]. Emphasizing teachers’ adaptive expertise and responsiveness, the framework contributes to the literature on which sustainable pedagogy-based practices form the foundation of practices that promote sustainable learning within disciplinary and contextual constraints [7,9]. In their management role, the teacher demonstrates that sustainability is enacted in class through iterative decision-making, feedback use, and system regulation. This model also provides theoretical grounds for analyzing teachers’ lived experiences—especially descriptions of regulating inquiry processes, responding to uncertainty, and adapting instruction—from phenomenological analysis.

2.2. Sustainable Education and Teaching

Sustainable education is not only about protecting our environment; it is also about adaptive and equitable pedagogies that adapt and respond to our long-term needs. A critical perspective on this concerns critical thinking, problem-solving, cooperation, and lifelong learning as enablers of sustainable development [6]. It argues for the quality and relevance of pedagogical experience and moves away from a restricted view to a pedagogy that is responsive to social, technological, and educational reforms on a time-bound basis. Studies in sustainability education illustrate the implications of pedagogies that center learning on a purposeful integration of all involved participants and on learning to make sense for students [35,36]. Conventional teaching models have been increasingly criticized for failing to achieve these aims, particularly in science education, where active and purposeful engagement and sense-making are the bedrock of teaching practice [37]. Indeed, many educators and researchers realize that sustainability in learning relies on such active learning practices to facilitate adaptable instruction and is rooted in teachers’ capacity for informed instruction in a classroom that is constantly evolving. Sustainable teaching practices, according to Evans and Ferreira (2020) [38], are best summarized as those that can be maintained and refined over time, rather than implemented piecemeal as a single, standalone innovation. This perspective places teachers in roles beyond that of lecturers and/or curricular producers, wherein teachers create, shape, and adapt the learning process to its context.

2.3. Inquiry-Based Learning in Science Education

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) has been widely studied as a pedagogical method and is aligned with the objectives of science education reform. Basing its philosophy on a constructivist and sociocultural perspective on learning, IBL emphasizes students’ responsibility to pose questions, design inquiries, analyze evidence, and develop explanations [39,40]. This aligns with Dewey’s experiential learning, which involves students in producing knowledge in real-world, experiential, and problem-based contexts, grounded in experiences and situations, through a learning cycle consisting of hypothesizing, investigating, interpreting results, and generating new questions [41]. The Next-Generation Science Standards (NGSS) promote students’ research, model building, data collection, analysis, and argumentation about their epistemic practices within inquiry [42]. Moreover, Vygotsky (1978) [29] suggests an inquiry-based perspective: individuals jointly construct knowledge through social interaction, and learning increases with support from knowledgeable others (ZPD) when guided by someone more capable in the field. Vygotsky’s sociocultural perspective advocates that learning is internalized through language, collaboration, classroom discussion, peer work, and teacher input and feedback. Through activities such as peer research or scientific reasoning, students practice scientific thinking skills that contribute to their understanding of the world and their capacity to learn in the future [43]. They can validate ideas with evidence of their knowledge, draw associations, review, and revise explanations in response to a peer’s critique.

To develop a sustainable learning approach that fosters long-term planning, monitoring, and evaluation of students’ learning, the teacher establishes a scientific conversation and a classroom space for discussion [44]. As guides and designers, they ensure students experience and understand the science process and build interdisciplinary relationships, which means that inquiry learning will persist and foster a lifelong learning environment through continuous questioning.

More resilient inquiry ecosystems require the teacher’s purposeful, conscious, and ongoing guidance of students’ learning to cultivate lifelong learning habits [43,45]. Teachers design the environment in which students learn, drive the learning processes, and establish an ongoing cycle of inquiry among learners rather than knowledge transfer. The teacher role can be framed as a sustainable practice for integrating pedagogical, curricular, assessment, and contextual knowledge. The inquiry ecosystem is an organizational structure in which a teacher performs both planning activities and the design of an entire learning environment. In this ecosystem, the teacher is not just a guide; the teacher develops questions to guide students’ thinking and coaches them in asking questions without providing answers. Furthermore, teachers provide the prompt students need at the right time to help them discover their own path by including assessment at every stage of the learning journey. Assessment is more than the product of inquiry-based learning; it is a process that enables a teacher to continue the assignment, record observation notes, discuss evidence, review student notebooks, use rubrics, and more while demonstrating thinking and feedback. Teachers use these resources as evidence of progress, rather than for grading. Process assessments for monitoring students’ development are part of sustainable learning [42]. It follows that inquiry-based learning is sustainable when teachers’ professional development needs are continually integrated into teaching practice. In a sustainable inquiry ecosystem, assessment and feedback are tools that allow students to continuously improve their scientific processes, epistemic practices, and self-regulation skills by enhancing learning strategies [46,47]. Teachers must direct the path of investigation and provide immediate, structured feedback to ensure the continuity of the student learning cycle. Such an approach creates a more lasting influence of inquiry-based learning and ensures the sustainability of the learning ecosystem.

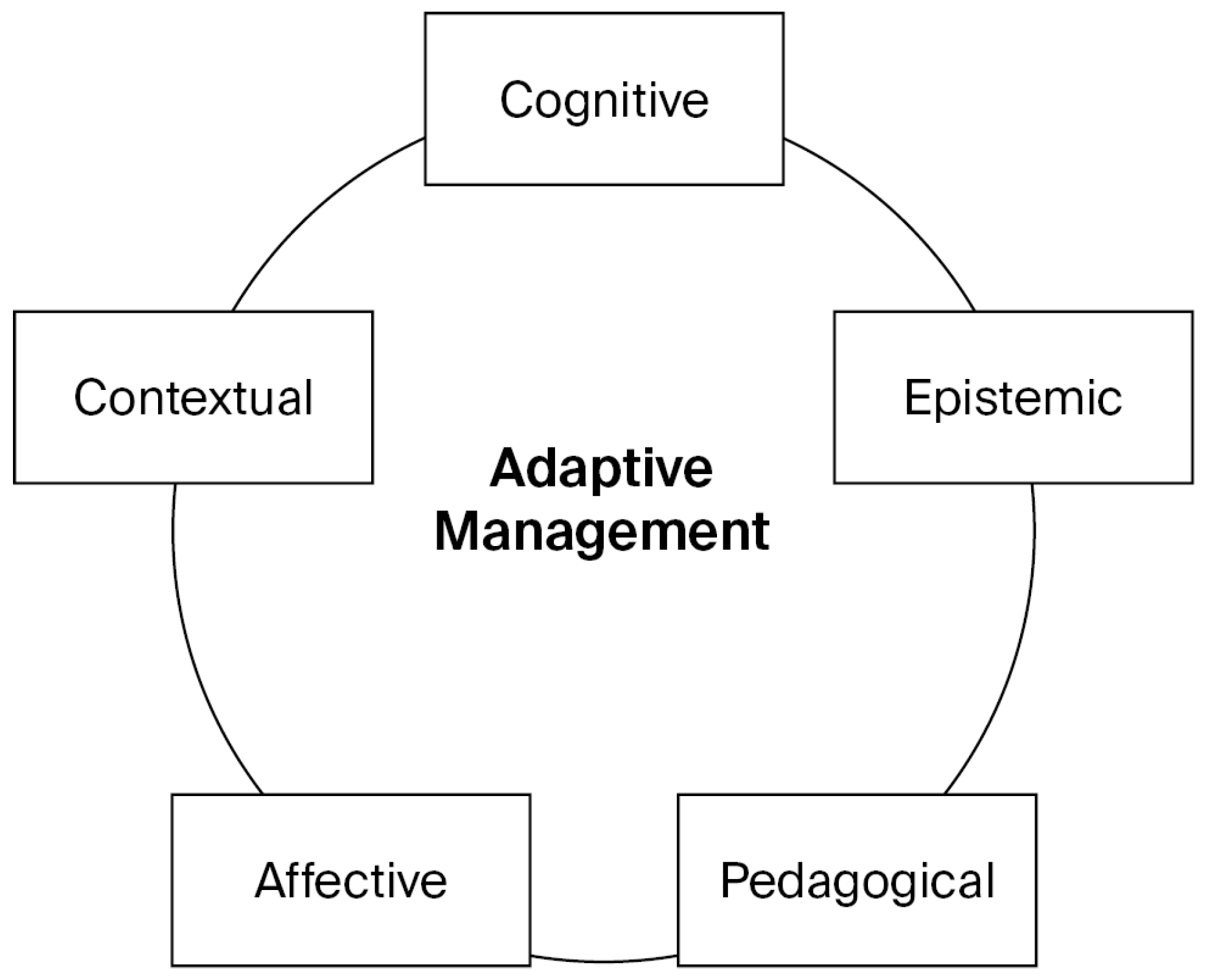

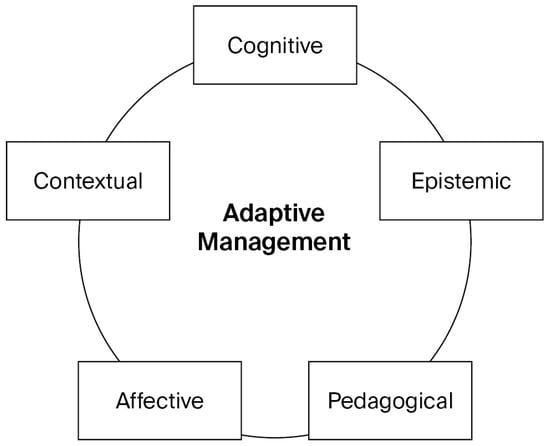

Recent research [39] has found that inquiry-based learning has the potential to address cognitive, affective, and contextual elements. The inquiry ecosystem supports students’ learning agency (cognitive), knowledge production and scientific thinking skills (epistemic), contextual meaning-making and transfer (contextual), and learning retention through emotional engagement and motivation (affective), along with a learning environment connected with the broader environment and life through pedagogical structures and pedagogical approaches (pedagogical) for sustainable learning. For example, the holistic inquiry approach asks students to sustain their own learning in the long term. This capacity goes beyond mere knowledge to encompass ongoing learning and the practice of cognitive and affective norms such as curiosity, questioning, scientific thinking, and self-regulation [19,43]. Students’ motivation, curiosity, and confidence, the classroom culture, the available resources, and the school’s physical environment determine the quality of inquiry. Consequently, inquiry is not only an instructional strategy but also a learning ecology in which teachers, students, resources, evaluation, and setting are interdependent. By linking abstract concepts to tasks that promote the production and appraisal of evidence-based knowledge, this approach guides students toward evidence-based inference and builds their scientific reasoning skills. When viewed as an ecosystem, inquiry-driven learning encompasses not only cognitive processes but also the pedagogical structure, learning resources, contextual and epistemic elements, and affective factors (Figure 1). These findings indicate that the sustainability of IBL should be examined not only in terms of curricular design but also in terms of teachers’ instructional judgment and their capability to tailor inquiry techniques to local settings.

Figure 1.

Cycle of sustainable inquiry ecosystem through adaptive management.

Studies have shown that positive, caring, and supportive student–teacher relationships are associated with improved learning performance and engagement, enhanced emotional regulation, increased social competence, and greater readiness to take on challenges [47]. Learning cannot take place in an environment in which students do not feel physically or psychologically safe because fear and anxiety are barriers to cognitive processing in the course of learning. Positive relationships can enhance students’ development and well-being and foster them to be culturally competent, creating links between what takes place in school and the world students know and experience. School and classroom organization should support student–teacher attachment and positive, long-term relationships in students’ academic and social–emotional life, thereby fostering developmentally appropriate competencies, emotional security, resilience, and agency. Making the learning environment more personalized can help students feel seen and understood, and meeting their needs more effectively is a powerful lever for enhancing student outcomes.

2.4. Adaptive Instruction for Sustainable Inquiry-Based Learning

Enacting and sustaining inquiry-based learning (IBL) in classroom contexts requires an attentive study of teachers’ management decisions. Studies of teacher cognition and professional practice consistently show that teaching is a complex, ongoing, and contingent process constructed through active negotiation of students’ understandings, actions, and preferences [48,49]. Instead of providing learning in a linear or deterministic fashion, teachers make continuous choices as they respond to the classroom, negotiate curriculum objectives, and manage uncertainty in real time [27]. This view positions adaptive expertise among the key aspects of effective teaching.

Research indicates that effective inquiry-based pedagogy relies heavily on teachers’ ability to make pedagogical decisions moment by moment. Inquiry-based classrooms need teachers to balance openness and structure, provide timely and responsive scaffolding, and respond productively to unexpected student ideas and questions [11,50]. Teachers constantly need to assess when to intervene, when to withhold support, and how to facilitate inquiry without compromising students’ sense-making [24,51]. For example, Hardy et al. (2022) [52] showed that teachers’ diagnostic strategies and contingent support moves in science lessons predicted long-term conceptual understanding and student engagement. These results indicated that iterative monitoring and adjustment of learning led to sustained inquiry through teachers’ real-time adaptations of discourse. These adaptive instructional strategies are essential for continued productive inquiry and for aligning inquiry with learning.

A significant majority of the literature on professional development and curriculum design has focused primarily on strategies or activity structures while ignoring the processes that enable teachers to make sense of classroom evidence and shape feedback around it [53]. Thus, inquiry-based learning is often considered a technique for teaching with fidelity, rather than a dynamic, situation-sensitive pedagogy that develops over practice. This gap underscores the importance of conceptual frameworks that directly consider teachers’ adaptive practices when exploring the sustainability of inquiry-based learning. Honke and Becker-Genschow (2025) [54] underlined the significance of adaptive management environments in science education and emphasized the importance of technology-mediated adaptability for sustaining the scientific experience of grasping a concept.

Adaptive management provides a robust theoretical model [26] which involves iterative cycles of planning, action, monitoring, reflection, and adjustment in practice, underscoring the importance of learning through practice as a fundamental means of improvement [55]. Adaptive management is about avoiding optimal or fixed solutions and emphasizes responsiveness, evidence-informed decision-making, and an ongoing learning process. In the context of education, it views teaching as the management of a dynamic learning system, rather than a prescribed process [56]. From this vantage point, teachers become adaptive managers who assess the effectiveness of instructional strategies using classroom data, taking into account students’ reactions (ideas, engagement, and emotions) as well. This perspective resonates closely with knowledge on teacher noticing and pedagogical reasoning, focusing on teachers’ professional judgment and interpretive practice in directing instruction [57,58]. From a sustainability perspective, the integration of adaptive management is highly relevant to inquiry-based learning. Sustainability-based education means teaching methods that not only have proven effective at stimulating learning but can also be adjusted over time in light of ongoing curricular demands, learner heterogeneity, and institutional constraints [7,36]. An inquiry-based approach to pedagogical learning enables both teaching and learning to be more effective and sustained, fostering professional development by making teachers more reflective practitioners who learn from their practice [28,38].

While prior studies have focused on inquiry-based pedagogy, teacher decision-making, and adaptive management strategies, empirical work on inquiry-based learning and sustainability is limited, especially in physics education. The current study seeks to address this gap by using adaptive management as a conceptual lens to explore how physics teachers perform and maintain inquiry-based learning through continuous decision-making. The work foregrounds teachers’ adaptive practices, which add an important dimension to the exploration of sustainable, inquiry-based teaching, in line with the goals of quality and equitable education promoted by Sustainable Development Goal 4.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This theoretical framing informed both the study’s design and the analytical lens used to interpret the teachers’ accounts. The study evaluated teachers’ views on inquiry, the methods they adopt to cultivate students’ science process skills, disciplinary epistemic practices, and the strategies they use to ensure the continuity of these practices. It is phenomenological in nature, with phenomenology being a qualitative research method that aims to explore and understand meaning-making processes in the human experience and strives to bring out and examine individuals’ lived versions of that experience [59,60]. The phenomenological perspective aims to understand how people experience a phenomenon, thereby clarifying its meaning, and it is particularly appropriate here, as the goal of this study is to examine the inquiry-based learning ecosystem, classroom implementation strategies, and sustainable learning perspective of physics teachers in public schools in Türkiye. It allows us to understand the experiences and pedagogical and epistemic meanings that teachers bring to their interactions with inquiry, and how their own contexts can be positioned within these processes. Phenomenology was selected to explore the participants’ experiences and the subjectivity that governs their meaning-seeking and is also applicable to the description of complex pedagogical processes that involve adaptive decision-making under situational constraints. In contrast, a case study design is frequently used in the study of a context or institution, allowing a comprehensive view of the events, practices, and processes [61]; however, since this study focuses on teachers’ experiences and perceptions rather than the context, a case study would be of limited significance [61]. Furthermore, while other qualitative research designs (e.g., ethnographic, action research) are oriented towards the sociocultural setting or the mechanisms of action and change, this study aims to capture teachers’ inquiry-based learning experiences and their meanings, which are subjective matters. Thus, a phenomenological approach was adopted to ensure a qualitative research design consistent with the study’s purpose. Through the topics and understandings generated from the teachers’ lived experiences, we gain a rich, locally valid understanding of the sustainability of the inquiry-based learning ecosystem.

Phenomenological Stance and Researcher Positioning

This study is phenomenological in its orientation to participants’ lived experiences and meaning-making contexts relating to inquiry-based learning (IBL). Our central analytic concern is understanding teachers’ perceptions, interpretations, and responses to uncertainty in the context of IBL in their own practice. Therefore, the study does not aim to explore all previous assumptions in a phenomenological sense, but rather puts teachers’ understandings and the variability of their experiential narratives into focus. In practice, we put this position in operational terms by applying thematic analysis as a pragmatic, transparent analytical strategy for uncovering patterns of meaning embedded in the interview data in a way that addresses the experiential dimensions that phenomenological approaches promote.

All interviews were conducted by the first author, a researcher experienced in inquiry-based learning in science and physics education. This experience contributed to the drafting of the interview approach and facilitated an adequate focus on teachers’ narrative. The process also required reflexive reflection on possible assumptions regarding the worth and use of IBL. During data gathering and analysis, the research team engaged in reflexive conversations to guard against interpretations that did not come from participants’ own experiences or evaluative assessments of practice.

Sample size is an important consideration in qualitative research design, and a sample size of eleven teachers was chosen to prioritize depth of experiential variation over statistical representation of the phenomenon of inquiry-based learning. The sampling was never meant to demonstrate the generalizability of the findings to a broader population, but rather to record how teachers may have interacted with and made sense of adaptive decision-making in inquiry-based learning in different forms. Such work aligns with phenomenologically informed qualitative research that supports analytical rather than quantitative generalization.

3.2. Participants

A purposeful sampling method was used to select participants for this study. Using the aforementioned phenomenological approach, we sought to collect data about physics teachers’ experiences and implementation of inquiry-based learning. These practitioners had at least 8 years of teaching experience and an undergraduate degree in physics or a teaching degree in physics, including, for example, teachers with undergraduate physics degrees who had obtained a pedagogical formation certificate from faculties of education. Eleven teachers from public schools in a metropolitan city in Türkiye, including both Anatolian High Schools and Vocational High Schools, volunteered to help with the study and interpret the inquiry-based learning (Table 1). To support transferability, Table 1 provides details on the participants and their teaching environments. These contextual details are important for understanding the structural and material conditions under which the inquiry-based learning was undertaken, including conditions with crowded classrooms and limited laboratory resources.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating physics teachers.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted to collect qualitative data and were audio-recorded with participant consent for thematic analysis. Each interview lasted 60–90 min and aimed to capture rich discussions with the educators about their experiences, understandings, and/or implementation practices within the IBL ecosystem. This approach involved a phenomenological investigation into the nature of participants’ experiences, and the following interview questions were used to elicit teachers’ perceptions of the sustainability of the inquiry ecosystem and help them to express their experiences and explain classroom cases and insights from these experiences:

- How do you describe inquiry-based learning (IBL)?

- How do you develop a learning culture through inquiry?

- What kinds of inquiry activities do you plan and implement in your classes?

- In what ways do you develop students’ science process skills?

- What type of assessments do you utilize in the context of IBL?

- How do these assessments help you improve students’ learning?

- Do you think IBL is a continuous process? Why?

- Are there any challenges to integrating IBL into classroom teaching?

In addition to this predetermined set of questions, the semi-structured interview technique employed allowed the teachers to reflect on and explain the content and meaning of the interview [62].

This study used phenomenological and thematic analysis to explore teachers’ perspectives on inquiry-based learning, which enabled us to collect data on the participants’ lived experiences and systematically generate the thematic categories [59,62]. All interviews were transcribed verbatim, and audio recordings were compared for accuracy. Transcriptions of the teacher interviews were grouped into units of meaning to convey the essence of these teachers’ experiences. At this stage, the researcher aimed to identify the subjective and/or interpretive aspects of teachers’ perceptions and their implementation of inquiry-based and sustainability practices. Because subjective experience was conveyed through the respondents’ responses, the phenomenological approach enabled their statements to be sensitively coded using thematic coding and categorization, generating phenomenological codes that could help to identify recurring patterns. The codes were derived from the research questions and the IBL elements (cognitive, epistemic, affective, contextual, and pedagogical). In this phase, themes were grouped according to teachers’ personal experiences. Codes and themes were gathered and compiled into a codebook which provided definitions for the focus on IBL elements (Table 2).

Table 2.

Themes and their focus for an inquiry-based learning ecosystem.

Several strategies were employed to enhance the study’s trustworthiness. First, both authors discussed the coding process to establish consistency, and the themes, subthemes, and codes, along with the teachers’ quotes, were compiled in the final step. This iterative process identified five interrelated approaches to sustaining IBL: student-centered, experiential, flexible, scientific, and emotional. This process not only revealed how the analysis was conducted but also the phenomenological properties of teachers’ experiences and the thematic classification based on analytic consensus. Thereafter, peer debriefing was conducted to facilitate critical analysis of emerging interpretations and refine the thematic structures. In this process, the authors documented the coding decisions, theme development, and analytic memos through continued reflection.

In the analysis, adaptive management was identified as a teacher’s decision-making in the face of uncertainty, rather than predetermined instructional strategies. Teachers make sense of feedback from student responses, engagement, and difficulties during inquiry-based learning activities, and then adapt their practice by applying their interpretations. These changes are neither linear nor predetermined but cyclical processes of observation, interpretation, and response in which each move alters the instructional context, which remains a work in progress. From this perspective, adaptive management is an iterative process in which teachers make sense of feedback generated from cognitive, affective, and epistemic responses during inquiry-based learning and adjust their actions. To explicitly articulate this analytical position, we revised Table 2 to present Adaptive Management Actions as the analytical categories that represent teachers’ interpretive and responsive decisions made in response to observed classroom feedback, rather than as isolated or prescriptive teaching practices. Table 2 shows how teachers’ interpretive and responsive decisions are systematically connected to cognitive, affective, epistemic, pedagogical, and contextual dimensions.

4. Results

This investigation framed inquiry-based learning using five frameworks drawn from constructivist theory: student-centered (guidance-focused), experiential (practice-oriented), flexible (meaning-focused), scientific (systematic), and emotional (human-centered). These frameworks show how physics teachers enact IBL through their pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) and the adaptive instructional practices they employ. These dimensions articulate how teachers implement an inquiry model of inquiry education that blends cognitively with sense-making, epistemically with scientific thinking, contextually with links to resources and curriculum constraints, pedagogically with responsive instructional design, and affectively with motivation and emotional security. In this way, this analysis highlights teachers’ instructional decisions and students’ active engagement and interaction with the cognitive, epistemic, contextual, pedagogical, and affective systems of learning. Teaching is conceived as an adaptive activity in which teachers interpret evidence to adjust their practices to accommodate learners’ needs across various situations.

The findings suggest that teachers’ PCK mediates inquiry-based instruction, aligning disciplinary goals with students’ ideas. For instance, the participating teachers’ pedagogical knowledge relates to how they address students’ alternative conceptions through a variety of instructional techniques, thereby cultivating a genuine climate. Their approaches to students and assessment align with both instructional and epistemic perspectives, thereby accommodating learning difficulties and uncovering each student’s thinking. Their contextual and curricular knowledge allows for contextual and affective learning, enabling the appreciation of a cultural way of knowing. These teachers’ adaptive management of inquiry-based learning was observed to be an interaction between teaching and learning in a cyclical process comprising planning, enacting, monitoring, and adjusting. These elements of PCK facilitate the holistic nature of teacher knowledge and are beneficial in unique ways, thereby laying the foundation for inquiry-based learning.

4.1. Student-Centered and Guidance-Oriented Approach

This theme centers around a democratic, reflective learning culture, illustrating teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) in action as they balance disciplinary goals with responsiveness to learners’ needs. Audrey, Bella, and Camila employ a student-centered pedagogy, viewing teaching not as imparting knowledge but as coaching. Adaptive management is evident in their student-centered instruction to enhance students’ awareness. These teachers explained that teacher adaptation to a student-centered and guidance-focused approach is a process involving ongoing monitoring of students’ reasoning and decision-making where non-intervention is no longer productive. Rather than relying on a rigid set of guidelines, the teachers reported delaying intervention until they noticed signs of a problem, such as repeated unproductive trial-and-error and explanations lacking causal justification. These cases led to deliberate choices to include tailored prompts or constraints. Therefore, guidance is not a fixed instructional mechanism but rather a context-specific response to perceived adaptations in students’ meaning-making.

Audrey believes that learning is achieved through doing and repeating: “I am only concerned that the students should produce their questions by trial; they shouldn’t just search out, slowly find an answer, but they should learn a process,” she said. She reflected that adaptive decision-making is achieved through students’ active participation, with teachers serving as mentors throughout the process.

Bella attributed this influence to formative monitoring of students’ participation, stating, “I help students find their way; I help students find knowledge on their own, not just give it to them on a plate or spoon-feed them; I become a guide and a coach.” She delays explanations and promotes independent thinking by prompting, questioning, and waiting for students’ pauses before responding. This is a strategic guidance method where teachers vary the level and timing of the intervention given to students based on their ongoing responses.

Camila employs the principles of structure and system in constructivist learning. She said, “The information isn’t what I tell them in my class, but it is in what they discover within the process.” By structuring her pedagogy, Camila supports students in developing independent inquiry skills, thereby fostering active student participation in learning. She continued, “I consider which of my students would try it and which would prefer to watch. Some students prefer to experiment, while others wait to see what others have done.” Such a statement implies an awareness of students’ diverse learning characteristics obtained through an adaptive cycle of observation, interpretation, and instructional adjustment.

Audrey noted, “Fashion design is a kind of department where we have in vocational schools; these students generally fail in school academically; those kids suffer failure, they have a lack of progress, they suffer from a loss of confidence in education.” Audrey’s understanding helps students overcome their struggles by valuing them as individuals and highlighting adaptive replanning based on their needs.

Bella also remarked, “I feel like learning is permanent for that moment when a student’s question made me assure the learning. I wait until I am sure that the student understood.” Adaptive management is evident in the alignment of inquiry activities with students’ epistemic curiosity.

The teachers believe they could monitor student learning in a formative manner, for example, through observation. “It’s more valuable for me to see how students think, not the results,” said teacher Audrey. Teachers should support students in reflecting on their learning and in monitoring their ability to act on their development; teacher judgment is essential within the learning process.

Camila said of students’ attitudes, “I can tell from the expression on their faces… You can tell what will happen on the exam by their attitude in class.” She also described adjusting guidance in response to students’ affective states: “There must be an emotional connection in learning, learning is not only a cognitive dimension, as it must involve teachers on an emotional level.” This illustrates affective monitoring as part of adaptive management; the adaptive response reflects teachers’ PCK by integrating content goals with knowledge of learners’ emotional needs. Bella also addresses the social and emotional contexts of her students: “I use students’ immediate experiences to present the topic from their perspective.” In other words, she wants to show how the topic connects with students’ lives.

The teachers defended generative learning in the face of the limitations of the curriculum and adapt course materials to the students’ needs. Bella said, “We follow the Ministry of National Education curriculum, but I use additional resources based on students’ levels and design the instruction to support learning outcomes.” This example shows how teachers adaptively manage inquiry-based learning within contextual constraints, reinforcing the sustainability of these instructional practices.

Audrey described the curriculum as a framework and adds new content that can increase student engagement. “I don’t address the objectives individually; I prepare questions appropriate for each objective. This way, I try to engage students in the process.” Through these activities, Audrey incorporates inquiry-based learning as an intervention, allowing inquiry-based instruction to be adapted to students, classrooms, or schools in ways that reach a broader range of students. For instance, she defined context as follows: “If I realize one in 30 students doesn’t understand at all, I can’t continue explaining.” Some teachers employ experiments and physical activities in a student-centered manner, fostering a positive learning environment.

Camila also shifts students’ ideas about space, turning the extracurricular space into a laboratory: “For me, the laboratory isn’t just a place to experiment; it’s a place where students learn to think. So, context deepens learning.” The teacher believes that the laboratory’s contextual value can deepen students’ engagement.

This theme is important because it positions student-centered guidance not as a fixed teaching strategy but as an adaptive management decision under uncertainty. Teachers do not anticipate when guidance would be needed; instead, they make decisions about timing and format based on emergent feedback from students’ reasoning processes. This realization emphasizes that student-centered inquiry is sustained through ongoing judgment and responsiveness, not by an instructional protocol. Inquiry-based learning focuses on student agency in sustainability as students experience self-regulation, curiosity, and the capacity to learn new things. By continuously monitoring students’ ideas and engagement and adjusting guidance accordingly, teachers sustain inquiry as an ongoing learning process rather than a fixed instructional routine.

4.2. Experiential and Practice-Oriented Approach

This theme reveals that teachers are advocates of inquiry-based learning as a means of engaging in experience and action rather than passively constructing knowledge. In such a learning ecosystem, students engage in observation, hypothesis generation, experimentation, problem-solving, data collection, and analysis to learn science, observe practice, and apply it. It is during this process that students learn, as they can apply knowledge across the cognitive, sensory, and emotional domains. It was found that students can understand the nature of science or experience concrete applications of abstract ideas. PCK is used to create and adapt these experiences, while adaptive management involves tailoring activities to classroom realities. Despite their divergent beliefs, Daniel, Elena, and Bella all argued that physics courses should be made more experimental and that students should actively engage with conceptual knowledge. A common pedagogical feature of these teachers is their belief that learning is both conceptual and practical, occurring through active, perceptual, and empirical processes. In an inquiry-based learning environment, experience is already a form of knowledge; students learn by observing, touching, and applying what they have learned.

Physics teachers are pedagogical gateways that materialize abstract ideas into an experience. The following quote by Daniel illustrates this position: “Experiential learning is solid knowledge. Because they can’t understand what the circuit elements mean, they understand after they put their hands on them. Abstract knowledge takes on concrete form in the lab.” This means that experience using the hands is responsible for developing epistemic awareness in learning. Daniel is a teacher who chooses pedagogical methods by considering them to be flexible and creative.

Elena often decides to use a different process and build lessons based on students’ feedback, giving students many opportunities to shape lessons: “There are certain things that are easier to explain in practice… Sometimes an experiment gives an error, but it’s okay. Students can also learn that way.” As she described her method, she revealed that she serves as a guide for students, including those who make mistakes. It is what makes an adaptive cycle of action, monitoring, and adjustment to convert failure into an inquiry question. These practices support students’ epistemic engagement, emphasizing reasoning and explanation over procedural correctness.

Bella defines experience not only as practice but also as a background for generating questions: “My favorite lesson is when the student is interested and asks endless questions.” This quotation suggests that experience is a source of cognitive productivity. Thus, these teachers demonstrated that they adapt pedagogical strategies to their students’ needs and develop practical, logical methods that encourage active student participation.

The teachers were concerned about what they had observed, what was problematic, and what was misunderstood in practice. Daniel stated, “We come across a lot of misconceptions. It just continues from middle school. Watching while understanding how they think shows me what they are ready for… My criterion is not whether a student concluded, but how the students think.” This quote shows that he wants to remain conscious of students’ cognitive activity. Rather than correcting answers immediately, he focuses on students’ explanations when deciding how to recommend revisions for later tasks.

Elena considers students’ different learning styles, voicing the idea that students have preconceptions about physics: “In fact, there are a lot of clever students in vocational high school, but their backgrounds are very weak… I think most of them could reach this level if they were addressed from the beginning.” She tries to make her lessons enjoyable to help her students change their thinking. Elena also observed that the process does not depend on the outcome but is dynamic: “It is not just the result of an experiment but also the extent of how the experiment developed.” Teachers’ management is evident in how they evaluate students’ competence and confidence, as experiential learning is linked to students’ cognitive and affective readiness.

Bella explained that students’ emotional reactions indicate learning: “When a student questions, learning begins”. Thus, she understands the emotional function of curiosity in terms of skills and performance in practical activities and problem-solving. Bella, who uses her students’ post-exam tensions, also believes that teachers should employ more non-verbal over verbal forms of assessment. She said, “Just students’ reactions in the class can tell. Then you see it. By their faces…you can see their expressions- by their attitudes, you can see how their exam will go.” This teacher focuses on students’ curiosity and motivation as signs of productive engagement, and on adapting instruction to make inquiry responsive to learners’ motivations.

Teachers enrich the context through experiments and hands-on activities, aiming to help students learn the concepts. Daniel supports the curriculum by incorporating material students have learned, everyday examples, and mini-experiments. Regarding the experiments and curriculum content mandate books, he said, “National books… there’s only one question in them, you solved it, you passed. I don’t look at the list of learning outcomes; I look at the practical aspects of the learning outcome.” This statement suggests that Daniel views the tests he administers as learning tools rather than as instruments of judgment. Daniel adapts activities based on an experiential approach to accommodate contextual constraints. He also extends this to the laboratory and the out-of-class observation field, saying, “Then I take them for evening observation around a pond next to our school. Observation by a pond can sometimes teach more than a week’s lesson.” He concluded that the context could better convey the natural complexity.

Bella argued that the curriculum should promote experimentation, observation, and modeling among students. This, she said, enables students to learn both scientific practices and physics concepts through experimentation. Bella herself aims to deepen learning by combining the cognitive and affective dimensions: “Experimental results should surprise students; when they are surprised, it makes it easier for them to think scientifically, and they experience that their predictions may not be correct.” She argued that experimental education is necessary for learning physics and that students should engage in scientific inquiry and discovery to provide formative feedback. Science is perceived as an epistemic endeavor that links the experiential approach to the formation of scientific thought. “Being a scientist isn’t just about measuring, it’s about being able to imagine,” Bella said. This comment led her to define scientific thought more broadly, including imagination and other forms of creative and experiential learning.

Elena provides examples from everyday life during her lessons: “Physical knowledge comes from nature… most of the work I do to discover things from the universe is the same… every innovation is almost an old practice… when you add something new, it changes… It’s initially about experience, then it becomes research,” integrating scientific knowledge and experiential processes into everyday life. This example illustrates how experiential engagement functions within an adaptive management cycle to use evidence-based strategies.

This theme highlights that teachers can introduce abstract ideas by exploring students’ own lives through experiences and examples. Teachers’ adaptive responses are grounded in feedback and analysis from students’ direct physical engagement with materials and activities. The teachers shared examples of planned hands-on activities that did not yield the expected results, leaving them confused about whether the difficulties stemmed from an inherent conceptual misunderstanding or from limitations of the activity. They explained how they would make decisions immediately when adjusting experimental procedures, simplifying materials, or focusing on specific aspects of the task. These adjustments referred to their goals and the ability to restore experiential learning epistemologically. This pattern suggests that experiential adaptation results from practice-based feedback and the reconfiguration of task strategies to foster productive inquiry, rather than simply adding to students’ activity. Analytically, this is relevant because it signals that experiential learning is sustained through adaptive reshaping of practice. The teachers’ own decisions reflect ongoing consideration of whether experience is functioning as an epistemic resource. Therefore, by continuously monitoring, providing responsive scaffolding, and adapting to context, teachers facilitate students’ active engagement with physical phenomena and sustained management of uncertainty.

4.3. Flexible and Meaning-Oriented Approach

This theme centers around learning through the contextual reproduction of knowledge, fostering a dynamic, flexible learning environment that nurtures curiosity and meaning-making, and encouraging inquiry to promote meaningful learning through cause-and-effect relationships, while fostering flexible thinking, and supporting students’ flexibility. Teachers assume roles as guides, transformers, and contextual adaptors within the ecosystem, fostering students’ meaningful learning and ensuring they are active participants in the lesson. They focus on students’ conceptual understanding, adjusting instructional flow based on evidence of comprehension, confusion, or emerging ideas. This method aligns with teachers’ PCK and their capacity to adaptively manage inquiry under conditions of uncertainty.

Florence’s pedagogy is adapted to students’ contexts of meaning, with sufficient flexibility for implementation. Florence referred to the adaptivity of pedagogy, stating, “I don’t want stereotypes. Everybody has their method. I mean, everything works… teach in every way to explore student conceptions. Let them learn, however they can.” The teacher demonstrated structured freedom, with behavioral flexibility in knowledge and its application, as well as in student-centered education.

Pedagogical adaptivity and the metacognition process establish a student learning ecology; pacing choices reflect students’ understanding of the concept rather than the content. Gabriel presented the implementation of a flexible, creative method that enables the redesign of demonstrations and the contextualization of the teaching context within the teaching process. His humor and example-based teaching methods engage students.

Hadi, however, introduced a progressive method and teaching process design concept, strengthening the system approach’s principle and teaching adaptation; “First of all, for students to be curious… We can ask question tactics to pull into the subject.” Hadi clarified that questioning is an active discussion in the learning process.

These teachers consider students’ learning pace, differences, motivations, and needs. Florence said, “Some learn about it by seeing it in their own lives, some with analogies. The thing to do is to maintain this relationship.” This statement also illustrates meaning-focused student knowledge, where the teacher emphasizes the learner as both a cognitive and cultural subject, demonstrating how the teacher adjusts the inquiry path to modify students’ comprehension and suggesting that learning is an iterative process.

Gabriel said, “You know, according to the conditions, our medium-scale class is 27 students, and our more limited-scale class is 30. Although 27 students are currently enrolled in the class, only one or two are usually ready. Actually, readiness has to be good because if students contribute to the course, I believe the success of teaching effectiveness of the classroom and its increasing effect a lot.” This teacher views students’ readiness as a key indicator for guiding their learning, showing a flexible, understanding approach to working. This is also an adaptive decision-making approach to responding to uncertainty, as teachers need to evaluate not only whether students’ notions are correct, but also whether they are ready to benefit from more guidance.

Elena added, “Some students see and discover words by themselves, while some learn the meaning of words by talking to each other; and when I speak, I constantly switch between those ways.” Here, the teacher shows her flexibility in adapting to students’ ways of constructing meaning.

Hadi, in contrast, said, “One student receives quickly. He has an open perception, a little curiosity. Compared to other students, learning… he understands and integrates information more quickly.” He considers student readiness and characteristics in developing a student-centered approach. His flexible pacing is used to respond to students’ epistemic engagement, framing their ideas as resources for collective sense-making.

These teachers implement assessment processes in contexts where students’ processes, reflecting their understanding, should be analyzed across various application and problem-solving situations. For instance, when she talked about her approach to student achievement, Florence said, “I don’t ask students, ‘What did you learn?’ I say, ‘What did you notice?” This underscores the value of reflective, qualitative forms of assessment that lead to internalized learning.

Gabriel, in contrast, tries short, fast measures, for example, administering short tests every two hours using technology such as Kahoot: “We can’t do that right now, but to understand that we are getting feedback, the child has to respond to questions outside the curriculum.” He explained that the system limits the potential of non-exam assessments and feedback.

Assessment, Elena also noted, is visible and not quantifiable: “Even if a student isn’t understanding the material, the difference in their questions just tells me that they have learned.” She talks about assessment as meaning- and reflection-based. Teachers cannot administer specific tests because they are time-bound or do not align with the curriculum, but they can conduct assessments using traditional tests, situational measurements, and observations, she noted.

Hadi employs continual feedback: “I know if they’re beginning to learn just by the questions I’m asking at the end of the lesson. If they get feedback on what they read, what they did, and what cases they made, I can tell if they’re learning.” Hence, she prioritizes students’ ability to express and generate knowledge rather than degrading it through memorization.

Teachers adapt the curriculum flexibly to the context and students. Hadi’s statement shows how the curriculum is adapted to relate to students’ context: “I provide examples appropriate to the student’s context for meaningful learning.” He also adapts the curriculum flexibly to students’ levels by critically evaluating it since the curriculum serves as a framework for meaningful learning for him: “I’m interested in how the student internalizes the outcome as much as the outcome itself.” Hadi added that the curriculum should help build meaningful knowledge. The curriculum’s density and the number of learning outcomes, particularly in the 11th and 12th grades, constrains student-centered learning practices, as teachers feel constrained in their autonomy to modify the curriculum. He prefers transforming the curriculum into a contextualized learning environment and improving students’ readiness.

Contextual constraints include not only limited learning infrastructure, such as the absence of desk attachments or shared laboratory equipment, but also the interrelated processes of learning and meaning-making. Florence adapts her teaching by managing learning contextually: “A topic isn’t taught the same way in every classroom: as the environment, students, and agenda change, so does the lesson.” This quotation reinforces flexibility as an adaptive decision-making process under uncertainty, encouraging teachers to consider whether uniform treatment of a topic limits students’ conceptual engagement.

Gabriel seeks to derive knowledge from experience, but has limited opportunities for its implementation as he primarily only has access to simulations and video materials: “We don’t have a laboratory… We demonstrate with YouTube or a simulation.” The teacher addresses flexibility as a pedagogical re-appropriation of resources, in which meaning is produced outside of prescribed laboratory practices.

Hadi’s confession reveals the limitations and context of the school and classroom in relation to learning physics: “Lack of materials… we had problems when there wasn’t enough experimental equipment… We couldn’t fully explain the procedures to the children.” Teachers have to balance flexibility with curricular demands through strategic decisions. Adaptive management is evident in teachers’ selective focus on conceptual meaning and in their sustained inquiry within constraints.

These teachers implement science activities flexibly and appropriately for each student. Students experience meaningful learning through hands-on activities, everyday examples, and experiments. Florence is currently experiencing experimentation and modeling: “We can model by taking spatial intelligence into account. We try to really put the child in a concrete sense of what happened.” Teachers tend to structure their lessons so that students can understand them through the scientific process and scientific modeling.

Gabriel described science as a human activity: “Science is not knowing nature,” he said, “it is understanding the relationship between humans and nature.” The integration of scientific knowledge with cultural awareness and the coordination of both facts and personality are precise for the student. Teachers explain the concept of accumulation in science to students and encourage them to think critically about it with a meaningful, contextual orientation.

Hadi explained the testability of knowledge: “Science exists as long as knowledge is realized, renewed, and confirmed experimentally, as knowledge can be tested… Science combines observation and meaning; the concepts are the words of natural reality. Science will be for all humanity.” Therefore, science is synonymous with the search for meaning. The teacher guides students’ curiosity and helps them understand its meaning.

The flexible and meaning-focused approach demonstrates that teachers maintain inquiry-based learning through adaptive pacing and sequencing. Teachers produce learning environments that prioritize conceptual understanding and coherence with curricular and contextual realities by repeatedly attending to students’ sense-making. In this approach, teachers’ adaptive actions reflected their interpretations of students’ various conceptual framings, not just accuracy. The teachers referred to students’ explanations as scientifically incomplete yet internally coherent. These situations led to confusion about whether to correct, expand, or temporarily agree with alternative meanings. These teachers reported resolving this uncertainty by altering task framing, representations, or questioning strategies so that students’ sense-making was retained while also steadily integrating it within disciplinary expectations. The adaptive decision was not about whether students were right or wrong, but about how to keep epistemic spaces open without losing conceptual orientation, shedding light on the judgment inherent in the inquiry-based learning. As a result, this theme highlights adaptation as a meaning-based decision under uncertainty, in which teachers must decide whether to intervene early to avoid disrupting students’ conceptual engagement. This reframes flexibility not simply as being open, but as an adaptive process embedded in interpretations of students’ epistemic progress.

4.4. Scientific and Systematic Approach

Inquiry-based learning endeavors to develop scientific thinking through observation, experimentation, data collection, and evidence-based reasoning. Teachers aim to engage students in central disciplinary procedures such as using evidence, creating and modifying models, and generating arguments. Teachers’ PCK is a key factor in coordinating these practices; adaptive management guides the maintenance of scientific rigor in light of students’ capabilities and classroom conditions. Irven, Hadi, Jamieson, and Camila noted that teaching scientific thinking requires cyclical and constructivist methods, and that their courses incorporate these methods. These teachers advocated scientific process skills, systematic thinking, modeling, and structured instructional design as epistemic processes and pedagogical strategies.

Irven puts all of this into practice in terms of pedagogical systematicity: “A systematic and constructivist approach allows students to understand concepts more deeply.” He then stated the following: “Actually, the child learns to question. Because when we talk about science lessons, they seek answers to questions like ‘why, wherefore, how.’ We try to teach this awareness and why-how to our students.” These statements reveal that the teacher bridges the gap between pedagogical and field knowledge through a cycle of monitoring and refining reasoning.

Camila aims to ensure retention by connecting abstract physics concepts to real-life examples and through practical inquiry steps: “When we give examples of a pair of scissors, a pencil, a slide at the park… it sticks in the children’s minds.” This is a constructivist pedagogy based on scientific process skills.

Hadi defines science as a process of generating conceptual meaning: “Concepts appear abstract to students, but when they are combined with context, they acquire scientific meaning,” thus establishing a science pedagogy based on conceptual construction. He defines a student as someone who seeks meaning and develops scientific explanations; thus, he seeks to identify the student’s causal reasoning styles and high-level awareness.

Jamieson stated, “Science is not only done with reason but also with curiosity; student interest is the beginning of the system,” thus combining an emotionally oriented science pedagogy with systematic thinking and intrinsic motivation.

Teachers want to consider students’ individual differences and support their thinking through open inquiry and questioning. They prefer to adapt instruction to students’ learning and prior knowledge and to ensure that students’ experiences are used to create more meaningful learning. In addition to promoting students’ in-depth conceptual learning, teachers use concrete, real-world examples. In Jamieson’s view, students’ mathematical and laboratory-based learning influences their physics learning. Jamieson said, “The number of students who like physics is very low. The cause of failure is the unwillingness.” Thus, the teacher considers the students’ level of preparation, their interest, and their motivation.

Irven, on the other hand, described his competence in understanding students’ cognitive and affective characteristics as follows: “I try to guide them with simple problem-solving questions so I can ask them questions they can do and get them to return to the lesson… First, students need curiosity… We introduce the topic by stimulating students’ curiosity with question tactics.” He uses various methods to stimulate students’ interest and seeks to identify and develop students’ scientific reasoning styles.

Assessment is based on systematic observation and application of students’ scientific processes and problem-solving skills. Irven uses continuous feedback to understand student learning: “I can tell they’re learning if I can give feedback on students’ understanding, what they’ve done, and what inferences they’ve drawn towards the end of the lesson.” Moreover, the teacher evaluates how well students express their knowledge and understanding, rather than focusing on memorization.

Camila gave this example of assessing whether students have learned the material: “Have they internalized the logical reasoning involved in the material? If they can multiply it by 5 and put it into another question, then they have learned.” This is another way the teacher uses a more holistic approach, relating conceptual understanding to its application. The teacher’s assessment methods are based on performance-oriented skills, conceptual understanding, and non-testing-oriented assessments.

Teachers plan the curriculum in line with scientific processes and constructivist methods. Jamieson stated that lessons were planned within the curriculum framework, but factors such as time and class density limited ideal teaching methods: “Classes are crowded, and we have a curriculum. We have to act according to its duration.” This situation demonstrates that teachers must plan lessons by blending curriculum knowledge with current conditions.

Camila stated that the curriculum did not align with the exam system and students’ needs: “We don’t need pages of books explaining topics; we need books that will ask you to solve many problems.” These statements demonstrate that the teacher has a strong awareness of the incompatibility between the curriculum and practice in developing critical thinking skills at the system level.

Irven demonstrates a professional profile that not only implements the curriculum but also interprets and adapts it according to context: “With the new educational model, we aim to do this better for the student… We aim to encourage students to learn by questioning, rather than simply accepting ready-made information.” The teacher recognizes the aims and models of the curriculum, applies them flexibly in light of time, student levels, and school conditions, and makes pedagogical choices to extend the curriculum when necessary to address students’ misconceptions.

Applied and systematic teaching strategies are developed in response to the classroom environment and material constraints. According to Irven, the physical and sociocultural context also affects the teaching process. He plans his teaching methods based on three dimensions: school facilities, the sociocultural environment, and student profiles. For example, despite the financial constraint of lacking a laboratory, he achieves this through creative approaches such as thought experiments, simulations, and outdoor gardening activities. “I do not have enough experience to show experiments, but I explain it with simulation and with demonstrations… For example, students may need to learn what circular motion is. I take them to the garden, draw a circle, and explain it there. I make them experiment with stones; I mean, I went to the garden…. Our lab is not suitable for experiments…” These quotes express that the professional context develops the teacher in an environmentally and culturally sensitive way, referring to the physical characteristics of their work: the professional context shapes the teacher.

Jamieson stated, “Society needs physics to enlighten… thanks to physics, we can manage and consume technology.” He develops knowledge into a contextual dimension. In this context, Jamieson focuses on group arrangement and planning. His vision extends beyond the physical sciences and encompasses the social dimensions of being human in the physical world.

The scientific and systematic approach provides insights into how teachers sustain inquiry-based learning by continually managing students’ engagement with evidence, modeling, and argumentation. Through continuous monitoring and responsive scaffolding, teachers support students’ epistemic participation in scientific practices while reinforcing inquiry as a systematic, evidence-based learning process. In this theme category, teachers referred to adaptation to track the coherence and structure of students’ inquiry. For instance, students showed uncertainty if they pursued active investigation and did not link their observations to models, variables, or evidence-based explanations. Teachers interpreted this gap as a signal to build rigor by reminding students about the phases of inquiry, naming variables, or emphasizing the need to justify conclusions with evidence. These findings suggest that systematic adaptation emerges as part of a regulatory response to epistemic change, enabling teachers to rebalance inquiry procedures and preserve student agency.

4.5. Emotional and Human-Centered Approach

Inquiry-based learning involves not only cognitive but also motivational and emotional processes, helping students learn about the emotions of curiosity, surprise, stress, and anxiety in a sustainable way during the learning process. This approach supports students’ awareness of social, ethical, and environmental issues, in addition to cognitive activities, to provide value-oriented processes. Teachers in this theme category aim to establish an emotional connection in learning, strengthen students’ intrinsic motivation, and foster individual awareness. Teachers’ PCK guides them to address students’ emotional cues. For example, Kamal and Jamieson prioritize students’ emotional and social dimensions in their lessons and shape their pedagogical practices accordingly.