Abstract

Sustainable development is a central objective of contemporary spatial planning; however, empirical evidence on how sustainability principles are implemented through municipal planning instruments remains limited. This study examines how sustainable development is embedded in Municipal Spatial Plans (MSPs) and reflected in spatial development practice in four Slovenian municipalities—Gornja Radgona, Hrastnik, Kostanjevica na Krki, and Lenart. A qualitative, indicator-based comparative framework was applied, structured around five thematic areas, twelve sub-themes, and thirty-one indicators. The analysis triangulated statutory planning documents, ten-year official statistical data, and five-year municipal investment reports, deliberately avoiding composite indices to prevent false precision in cross-municipal comparison. The results show that all MSPs formally incorporate sustainability as a guiding principle; however, significant differences emerge in how concretely these principles are translated into spatial provisions, investments, and observed development trends. Lenart demonstrates the strongest alignment between planning objectives and implementation, while Hrastnik and Gornja Radgona exhibit persistent gaps related to demographic decline and mobility patterns. Kostanjevica na Krki illustrates a protection-oriented sustainability approach shaped by flood risk and constraints relating to cultural heritage. The study concludes that MSPs primarily function as strategic and coordinating instruments, while effective implementation of sustainable development depends on complementary governance arrangements, investment alignment, and monitoring mechanisms beyond statutory spatial planning. The findings provide transferable insights for municipalities facing similar sustainability challenges.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development has become a dominant paradigm shaping contemporary policy and research agendas in response to climate change, demographic change, economic restructuring, and widening social inequalities [1,2,3]. Since the late twentieth century, spatial planning has increasingly been framed as a key integrative policy field through which sustainability principles can be translated into concrete spatial decisions [4,5,6,7]. By mediating between environmental protection, economic development, social cohesion, and cultural values, spatial planning is widely regarded as a critical arena for operationalising sustainable development in practice [6,8,9]. International and European policy frameworks, including the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the New Urban Agenda, the Territorial Agenda 2030, and the New Leipzig Charter, consistently emphasise this integrative role, positioning spatial planning not merely as a regulatory activity but as a strategic instrument for coordinating long-term development trajectories [10,11,12].

In recent years, a critical gap has emerged within the sustainability-planning literature: the need for a comprehensive examination of how MSPs translate sustainability principles into concrete spatial outcomes at the local level [9]. Within this broader planning framework, the municipal level occupies a particularly important position. Municipalities are responsible for land-use regulation, local infrastructure provision, and the coordination of development interests, making MSPs central instruments for steering sustainable spatial development [5,13,14,15]. At the same time, implementation at the municipal level is often constrained by limited institutional capacity, demographic decline, fiscal dependence on higher governance levels, and structural economic conditions that lie largely beyond the control of local planning authorities [8,16,17,18]. As a result, while sustainability principles are frequently embedded in MSPs, their capacity to influence actual development trajectories remains uneven. This tension between strategic intent and practical steering power makes municipal spatial planning a critical yet challenging arena for assessing how sustainability is realised in practice [7,13,19,20].

A growing body of research points to a persistent gap between sustainability-oriented planning intentions and observed spatial development outcomes [19,21,22]. MSPs commonly articulate objectives related to compact settlement patterns, sustainable mobility, environmental protection, and social infrastructure, yet empirical trends often reveal continued population ageing, labour commuting, car dependency, and uneven investment patterns. Despite widespread recognition of this implementation gap, systematic empirical research examining how sustainability principles translate from statutory municipal plans into observable development outcomes remains limited. This gap is closely linked to an unresolved methodological debate: how sustainability in spatial planning should be assessed in ways that meaningfully capture implementation rather than formal compliance alone [14,17].

Many existing assessments rely on composite indices or quantitative rankings, which can obscure local context and produce false precision when applied to small and medium-sized municipalities [3,17]. Such approaches tend to prioritise aggregate outcomes while paying little attention to the specific role of statutory planning instruments or to the interaction among planning provisions, development trends, and investment decisions. In response, scholars increasingly advocate context-sensitive, qualitative assessment approaches that conceptualise sustainability as a planning practice shaped by local conditions, governance arrangements, and development trajectories rather than as a single measurable outcome [4,14,21]. However, empirical studies that operationalise such approaches to examine MSPs and their implementation effects systematically remain scarce.

These methodological and theoretical debates are particularly relevant in Slovenia, where sustainable development is explicitly embedded in national spatial planning legislation and MSPs function as legally binding instruments with strong regulatory authority [23]. Slovenian municipalities face diverse sustainability challenges, including demographic ageing, post-industrial restructuring, environmental risks, and peri-urbanisation pressures [24]. Empirical evidence suggests that, despite strong formal integration of sustainability principles into MSPs, their implementation often remains uneven and highly dependent on local governance capacity, investment priorities, and external structural conditions [17,25].

Despite the recognised importance of MSPs as instruments for sustainable development, empirical research systematically examining how sustainability principles translate from statutory plans into observed development outcomes at the municipal level remains limited. Existing assessments are predominantly based on aggregated indicators or composite indices and rarely analyse how sustainability is operationalised within planning documents or aligned with long-term demographic and economic trends and municipal investments [22]. Moreover, few studies explicitly address MSPs as coordinating and adaptive instruments rather than as direct drivers of sustainability outcomes [14,18].

Against this background, this study applies a qualitative, indicator-based and context-sensitive comparative framework to examine how sustainable development is embedded in MSPs and reflected in spatial development practice in four Slovenian municipalities: Gornja Radgona, Hrastnik, Kostanjevica na Krki, and Lenart.

Three research questions guide the study:

(1) Do the Municipal Spatial Plans of the selected municipalities include provisions for implementing sustainable development principles?

(2) To what extent are planned spatial developments aligned with demographic, social, and economic trends and with municipal investment priorities?

(3) How effectively do Municipal Spatial Plans function as instruments for steering sustainable development in practice?

The contribution of this paper lies in demonstrating how sustainability is operationalised at the municipal level, identifying systematic gaps between planning intentions and observed development outcomes, and offering transferable insights for municipalities facing similar sustainability challenges.

It is important to note that the aim of the analyses was not to comprehensively measure or quantify the overall level of sustainable development implementation, as such an undertaking would exceed the scope of the study. Instead, the focus lies on identifying patterns, consistencies, and discrepancies between planning intentions and observed development trends.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the research design and methods. Section 3 presents the analytical framework and policy context. Section 4 provides municipality-level results. Section 5 discusses findings and the limits of MSPs. Section 6 concludes with a summary of the main contributions, implications, and limitations.

2. Research Design and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Research Aim

The study was conducted as part of the HEI-TRANSFORM project and served as a baseline analysis, laying the groundwork for heritage reuse proposals. Four revitalisation laboratories (RevitLabs) were established to test the Cultural Heritage 4.0 model within real spatial contexts. Each RevitLab represented a distinct typology of immovable cultural heritage: archaeological heritage in Gornja Radgona, a historic urban centre in Kostanjevica na Krki, a castle complex in Lenart, and industrial heritage in Hrastnik. These municipalities were selected because each paired a specific heritage typology with unique demographic, economic, and environmental profiles, enabling a comparative analysis of how similar planning instruments function under different structural constraints [26].

The study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of MSPs in steering sustainable spatial development, focusing on how well planning intentions align with actual development trends and municipal investment priorities. By selecting municipalities that faced similar sustainability challenges—such as demographic change, economic restructuring, environmental risks, and limited institutional capacity—but differed in their development trajectories, the research directly addressed questions about the integration of sustainability principles in MSPs, their alignment with real-world trends and investments, and the practical effectiveness of MSPs as planning tools. This approach provides analytically transferable insights into how sustainability is implemented at the municipal planning level.

2.2. Analytical Framework and Indicator Selection

The analysis employs a qualitative, indicator-based evaluation framework to examine how sustainable development is interpreted and operationalised in MSPs and how planning intentions align with observed development trends and municipal investment priorities. Rather than measuring overall sustainability performance or ranking municipalities, the framework focuses on assessing the internal coherence and practical steering capacity of MSPs in relation to sustainable spatial development.

2.2.1. Conceptual Premises

The indicator framework is grounded in three conceptual premises drawn from contemporary spatial planning theory and the sustainability assessment literature.

First, sustainable development in spatial planning is a multidimensional and context-dependent concept that aggregated indices cannot adequately capture at the municipal level. Previous studies have shown that composite indicators often obscure local institutional conditions, governance arrangements, and territorial specificities, thereby producing a misleading sense of precision when applied to small and medium-sized municipalities [27,28,29]. Consequently, this study adopts a qualitative approach that prioritises interpretative depth over numerical comparability.

Second, MSPs are understood as strategic and regulatory coordination instruments rather than as direct drivers of demographic, economic, or behavioural change. Therefore, the framework does not assume causal relationships between planning provisions and observed development trends. Instead, it uses indicators to assess whether sustainability-related topics are meaningfully addressed in MSPs, and whether planning intentions are broadly aligned with—or diverge from—empirical trends and public investment priorities.

Third, the framework is designed to enable context-sensitive comparison. Indicators are formulated to be sufficiently generic for cross-municipal comparison, while remaining grounded in the statutory scope, content, and regulatory logic of Slovenian municipal spatial planning. This approach ensures analytical consistency without imposing a standardised sustainability model across heterogeneous territorial contexts.

2.2.2. Structure of the Indicator Framework

The framework is organised into three analytical levels: thematic areas, sub-themes, and indicators.

At the first level, sustainable spatial development is addressed through five thematic areas: space, society, economy, environment, and culture. This structure reflects the multidimensional understanding of sustainability in international policy frameworks and planning scholarship and is consistent with the integrative role assigned to spatial planning in Slovenian legislation.

At the second level, twelve sub-themes are defined to reflect both international sustainability agendas and the statutory requirements of MSPs under Slovenian spatial planning law. These sub-themes translate broad sustainability principles into planning-relevant domains, such as settlement structure, transport infrastructure, social services, economic activity, environmental protection, and cultural heritage.

At the third level, thirty-one indicators operationalise these sub-themes. The indicators are formulated as qualitative descriptors, enabling assessment of whether specific sustainability-related topics are explicitly addressed in MSPs and substantiated by corresponding empirical evidence. For example, the indicator “promotion of sustainable mobility modes” assesses whether the MSP includes provisions for cycling or pedestrian infrastructure and whether corresponding investments or improvements are evident in the municipal context. Rather than directly measuring performance, the indicators serve as analytical lenses to examine MSPs’ contributions to sustainable spatial development.

2.2.3. Indicator Selection Process

The indicator set was developed through an iterative, multi-stage selection process combining top-down and bottom-up approaches.

In the first stage, a broad pool of potential indicators was identified through a review of international sustainability frameworks, European territorial and urban policy documents, and the academic literature on sustainable spatial development and planning evaluation. Internationally, the review focused on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals most relevant to spatial planning (SDGs 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 15, and 16) [30]; and the New Urban Agenda, identifying 37 spatially relevant commitments [17]. The Global Urban Monitoring Framework, with about 120 indicators across domains and scales, was also considered as a harmonised tool for SDG and New Urban Agenda monitoring [31]. At the European level, the review covered the Urban Agenda for the EU (14 thematic partnerships and 132 policy actions), and European territorial policy frameworks, including ESPON analytical frameworks (COMPASS) and the Territorial Agenda 2030, examined across 14 thematic domains and priorities [11,31,32].

This stage ensured conceptual completeness and alignment with sustainability principles, providing an overview of relevant themes before analysing Slovenian spatial planning legislation and MSPs. The academic literature showed that applying sustainability in spatial planning requires scale-sensitive, context-specific adaptation, and ongoing local validation through stakeholder engagement rather than simple transfer. Since none of the frameworks could be adopted directly, they served to verify the structure of five thematic areas and twelve sub-themes and were not used for direct indicator extraction.

In the second stage, the preliminary pool of indicators was systematically evaluated against the legal and institutional framework governing MSPs in Slovenia, including national spatial planning legislation and regulatory guidelines. Indicators that could not reasonably be addressed within the statutory scope of MSPs were excluded at this point.

In the third stage, a bottom-up review of the MSPs from the four case-study municipalities was conducted to assess empirical feasibility. Indicators were retained only if they met two criteria:

- (i)

- The indicator topic is explicitly addressed or clearly implied in at least one MSP.

- (ii)

- The indicator supports a meaningful qualitative assessment in relation to planning provisions, statistical development trends, or municipal investment data.

This process resulted in a final set of thirty-one indicators that collectively reflect both normative sustainability goals and the practical realities of municipal spatial planning. The complete indicator framework, including definitions and data sources, is presented in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

2.2.4. Explicit and Implicit Indicators

To address the varying levels of detail and regulatory specificity across MSPs, the framework distinguishes between explicit and implicit indicators.

Explicit indicators pertain to sustainability topics clearly and directly defined in MSPs, such as flood risk management, protection regimes for natural and cultural heritage, promotion of renewable energy, or wastewater infrastructure. These indicators generally correspond to legally binding planning provisions and enable a relatively unambiguous qualitative assessment.

Implicit indicators capture sustainability dimensions that are not always explicitly formulated as objectives in MSPs but can be inferred from planning logic, spatial design principles, or investment priorities. Examples include support for settlement revitalisation, improvements in living environment quality, or the promotion of sustainable mobility modes. The inclusion of implicit indicators acknowledges that sustainability is often embedded indirectly in planning documents, particularly where competencies overlap with sectoral policies or higher governance levels.

This distinction enhances analytical transparency and addresses differences in plan articulation without penalising municipalities for variations in planning language or document structure.

2.2.5. Indicator Assessment Logic

Indicators were evaluated using a binary qualitative logic (0/1) to determine whether a sustainability-related topic is meaningfully addressed in the MSP and substantiated by at least one empirical evidence source. A value of “1” signifies that (i) the indicator topic is explicitly or implicitly addressed in the MSP with sufficient specificity to influence spatial development, and (ii) at least one supporting empirical signal is present, such as alignment with long-term statistical trends or corresponding municipal investment.

A value of “0” indicates that the indicator topic is absent from the MSP, articulated only in very general terms, or lacks any observable connection to empirical evidence. Notably, the binary notation is not a performance score and does not reflect the degree, quality, or success of implementation. Its sole purpose is to offer a technical comparative reference that facilitates systematic cross-municipal analysis.

The binary assessment is complemented by detailed qualitative interpretation for each municipality and thematic area. Descriptive statistics and investment data are selectively employed to illustrate trends and support interpretation, without implying causality or establishing quantitative rankings.

2.2.6. Analytical Role of the Indicator Framework

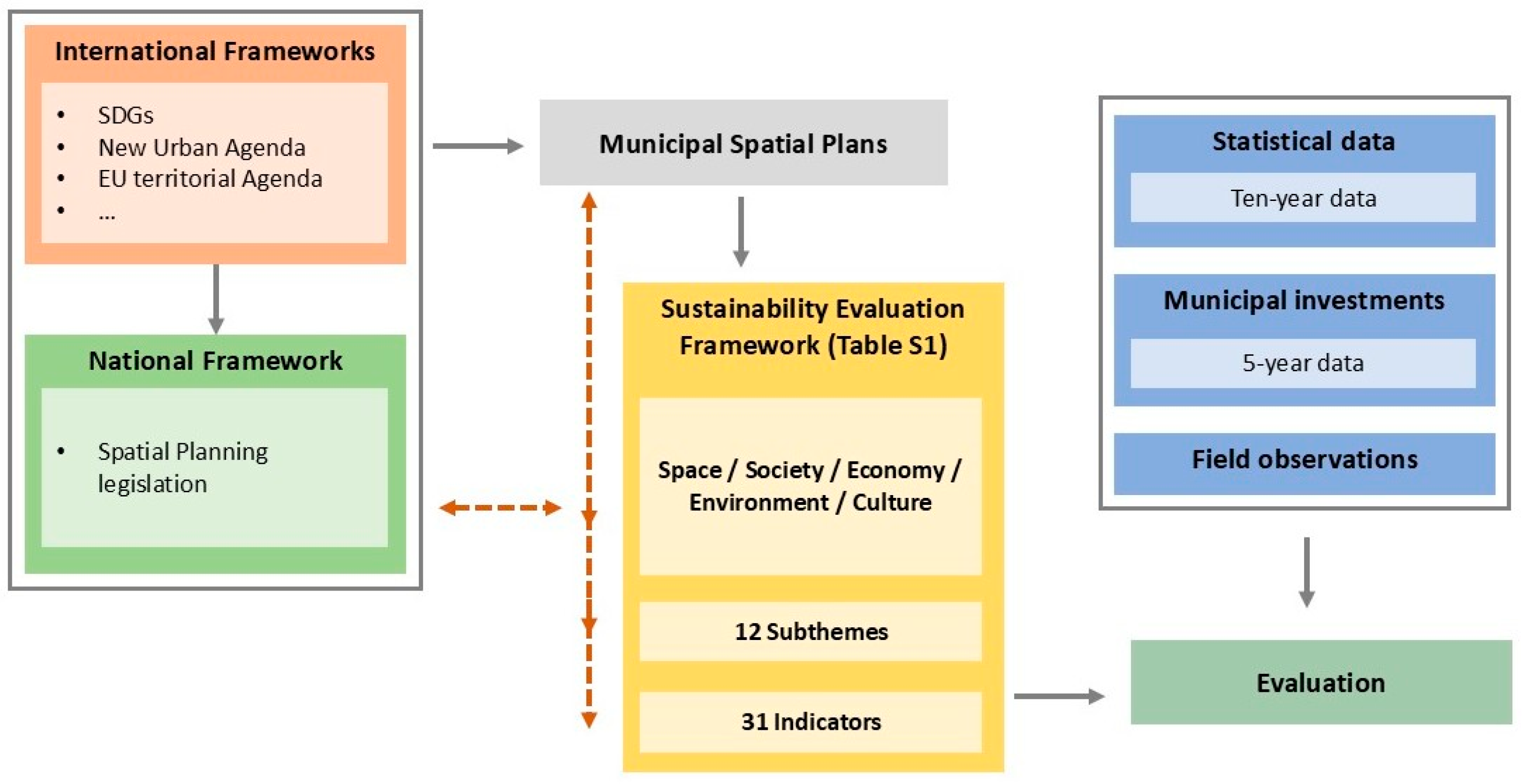

The indicator framework serves as an analytical scaffold rather than an evaluative or predictive tool. It facilitates the identification of patterns, consistencies, and discrepancies among planning intentions, observed development trends, and investment priorities. Differences between municipalities are interpreted as reflections of territorial context, governance capacity, and structural conditions rather than as measures of planning success or failure. A schematic representation of this iterative analytical process is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework.

2.3. Data Sources and Triangulation

The evaluation is based on triangulating multiple qualitative and quantitative data sources to capture both planning intentions and development realities. The analysis includes:

- MSP of Gornja Radgona, Hrastnik, Kostanjevica na Krki, and Lenart;

- Ten-year official statistical data (2013–2023) on demographic, transport, construction, and economic trends, obtained from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Public Legal Records and Related Services, and the Employment Service of Slovenia;

- Five-year municipal investment reports related to spatial development (2019–2024), used to assess development priorities and their alignment with MSP provisions.

Triangulation allows for cross-validation of findings and supports assessing whether sustainability principles articulated in MSPs are reflected in demographic trends and vice versa, and whether development priorities align with MSP provisions.

2.4. Evaluation Approach

The study adopts a qualitative evaluation approach and deliberately avoids assigning numerical scores or constructing composite indices. This methodological choice is intended to prevent false precision and to acknowledge variations in local context, scale, and development trajectories.

To ensure consistency and comparability across municipalities, all indicators were evaluated using a standardised qualitative assessment protocol. For each indicator, the same set of evidence sources was systematically reviewed across all four municipalities, including MSP, official statistical data covering 10 years, and municipal investment reports for the most recent 5 years. Evidence-informed qualitative judgments are used to assess alignment or mismatch between planning intentions and observed outcomes. Descriptive statistical indicators (e.g., percentages and index changes) are used selectively to illustrate the magnitude and direction of observed trends, without implying statistical inference or quantitative ranking, and to support qualitative interpretation within the indicator-based framework.

Indicators were assessed using uniform interpretative criteria focusing on three dimensions: (i) explicit inclusion of the indicator topic in the MSP, (ii) alignment between planning provisions and observed statistical trends or spatial development patterns, and (iii) evidence of corresponding municipal investments or implementation measures. An indicator was considered positively addressed when these dimensions showed coherent alignment, while divergences or absence of implementation evidence were noted qualitatively. This standardised evaluation procedure ensured that differences observed between municipalities reflect substantive variations in planning practice and development context rather than methodological inconsistency.

The analytical purpose of the indicator framework is not to evaluate sustainability performance, but to reveal how different categories of sustainability objectives interact with MSPs’ institutional steering capacity under different territorial conditions.

3. Sustainable Spatial Development as an Analytical Framework

This section provides the analytical foundation for indicator selection by reviewing the evolution of sustainable development, international sustainability agendas, and European and Slovenian spatial planning frameworks.

In spatial planning, sustainable refers to shaping how land, resources, settlements, and infrastructure are organised and used in ways that balance environmental, social, and economic needs—both now and in the future.

Sustainable development has become an important concept and approach to spatial planning in many countries worldwide, in response to pressing issues related to climate change, demographic change, economic development, and social justice. Sustainable spatial development means resolving conflicts in space from all three perspectives [6,10]. The economic perspective emphasises spatial solutions to promote economic growth and innovation while ensuring social justice and access to resources [5]. The environmental perspective means preserving natural ecosystems, protecting biodiversity, using natural resources rationally, and reducing environmental impacts, such as air, water, and soil pollution, as well as climate change [11]. The social aspect involves creating spaces that enable a high quality of life for all social groups, ensuring social inclusion, equality, and safety, and encouraging cooperation and participation of all stakeholders in decision-making on spatial interventions [12]. The cultural dimension of spatial planning recognises the significance of preserving cultural heritage, safeguarding local identity, and supporting cultural diversity as integral components of sustainable urbanism [13].

At the international level, the United Nations has addressed urbanisation and settlement development through its Habitat agendas. Habitat I in Vancouver [33] primarily focused on providing adequate shelter, while Habitat II in Istanbul [34] emphasised operationalising the principles of sustainable urban development introduced at the Rio Earth Summit (1992). Habitat III, formally the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, convened in Quito in 2016, represented a milestone in articulating a global vision for sustainable cities and human settlements [10]. A recurrent theme in these debates is the recognition of trade-offs between economic and social development, where progress in one domain may undermine achievements in another, as first articulated by the World Commission on Environment and Development. The Quito conference sought to renew and strengthen global political commitment to sustainable urban development. Its outcome, the New Urban Agenda (NUA), provides a strategic roadmap for sustainable urbanisation over the next two decades [10]. Unlike legally binding frameworks such as the United Nations Climate Change Conferences, the NUA is a non-binding instrument intended to guide governments, municipalities, and other stakeholders in implementing integrated approaches to urban planning and management [35,36].

3.1. Sustainable Spatial Development Within the Legal Framework of the European Union

Although the European Union (EU) does not directly regulate spatial planning, its institutional frameworks and strategic documents have played a decisive role in shaping spatial development across Europe. Much of this influence has been coordinated through the Conference of Ministers responsible for National Spatial Planning (CEMAT), established within the Council of Europe in 1970, which has consistently embedded the principles of sustainable development into its policy outputs. The early phase of European spatial policy emphasised broad principles and cross-border cooperation. The European Charter on Spatial Planning [37] laid the foundation by defining spatial planning as a tool for balanced development and environmental protection. This was followed by the European Spatial Development Perspective [38], which was the first comprehensive EU-level strategy integrating economic and social cohesion with the protection of natural and cultural heritage. Scholars note that this perspective marked a shift from declarative principles toward more operational programs [16].

During the early 2000s, European policy began explicitly linking sustainable development with urban issues. The Lille Action Programme [39] highlighted participation, integration, and urban balance, while the Urban Acquis [40] provided strategic guidance for integrated urban policy. The Bristol Accord [41] expanded this agenda by defining sustainable communities as safe, inclusive, well-planned, and equitable. These documents collectively emphasised urban sustainability as a multidimensional challenge, in line with Healey’s [5] call for spatial planning to address social equity alongside growth.

Later charters consolidated an integrated and interdisciplinary approach. The Leipzig Charter on Sustainable Urban Development [42] stressed the interdependence of social, economic, and environmental factors. At the same time, the Marseilles Reference Framework for Sustainable Cities [43] translated sustainability principles into practical urban tools. The Toledo Declaration [44] advanced a cross-sectoral model of urban governance, foreshadowing what would later be described as “multi-level governance” in EU policy [6].

The most recent phase demonstrates closer alignment between European and global sustainability frameworks. The Territorial Agenda 2030 and the New Leipzig Charter outline long-term strategies that correspond to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the New Urban Agenda [10,30]. These strategies highlight the transformational function of cities in advancing sustainable development and reinforce the EU’s cohesion policy objectives. Complementary initiatives, including the European Green Deal, the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, and the New European Bauhaus [45,46,47], link ecological sustainability with the cultural, economic, and social dimensions of urban life.

The Urban Agenda for the EU, established by the Amsterdam Pact, represents a milestone in the application of multi-level governance, engaging EU institutions, member states, regions, cities, and stakeholders in co-creating urban policies [48]. Its update, through the Ljubljana Agreement, reaffirmed priorities for urban resilience, housing, mobility, and financing mechanisms [49]. Scholars argue that these developments illustrate the EU’s growing reliance on “soft law” and non-binding frameworks to influence national and local planning practices [50].

Finally, financial mechanisms such as the Connecting Europe Facility, Cohesion Funds, Horizon Europe, and the Recovery and Resilience Facility provide the material foundation for implementing these strategic visions. Together, policy frameworks and financial instruments draw attention to the EU’s dedication to integrating sustainable development into spatial and urban planning, even in the absence of direct legal competence.

3.2. Sustainable Spatial Development in Slovenian Spatial Planning Legislation

In Slovenia, sustainable spatial development is embedded in national legislation, primarily through the Spatial Management Act (Zakon o urejanju prostora—ZUreP-3) and supported by complementary acts, including the Environmental Protection Act (Zakon o varstvu okolja—ZVO), the Nature Conservation Act (Zakon o ohranjanju narave—ZON), and the Cultural Heritage Protection Act (Zakon o varstvu kulturne dediščine—ZVKD) [23,51,52,53]. Together, these laws define sustainable development as a guiding principle for spatial planning, integrating economic, social, environmental, and cultural dimensions.

The Spatial Management Act explicitly states that spatial planning must promote sustainable spatial development by balancing present and future needs. It requires coordination between social, economic, and environmental aspects in line with the spatial potential of specific areas. Provisions emphasise quality of life, rational land use, accessibility to socially and economically significant services, and the complementary distribution of activities in space. Significantly, planning decisions must be based on an assessment of economic, social, and environmental impacts to select the most favourable and broadly acceptable solutions [23].

The Environmental Protection Act further mandates comprehensive environmental impact assessments for plans, programs, and projects likely to affect the environment [43]. This includes the explicit integration of cultural heritage protection into planning procedures [51]. Similarly, the Nature Conservation Act provides the legal framework for biodiversity conservation and the protection of natural values, requiring that biodiversity measures be incorporated into spatial planning and resource management to ensure long-term ecological balance [52]. In addition to this, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act establishes heritage protection as a component of sustainable development, framing cultural heritage not only as a value to be preserved but also as an active element in development planning at the state, regional, and municipal levels [53].

Sustainable spatial development in Slovenia is implemented through the preparation of national, regional, and municipal spatial acts guided by these legislative principles. A key feature of the system is the requirement for stakeholder participation, involving local communities, non-governmental organisations, businesses, and individuals at different stages of planning. Such participatory approaches enhance the legitimacy and social acceptability of planning decisions, which is consistent with broader European governance principles [5].

Practical measures in Slovenian spatial planning include promoting sustainable mobility (walking, cycling, public transportation, and car sharing), increasing energy efficiency in buildings and industry, and deploying renewable energy sources (solar, wind, and hydropower). Policies also support the local economy, culture, and sustainable tourism, which help preserve community identity and strengthen social cohesion. Decision-making in spatial planning is, therefore, oriented toward reconciling conflicting interests and ensuring that chosen solutions achieve synergies between economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

Ultimately, sustainable spatial development in Slovenia is realised through an integrated, multi-level, and interdisciplinary approach. Successful implementation depends on cooperation between national and local authorities, as well as the active involvement of disciplines such as economics, environmental science, social policy, and cultural studies.

4. Results

Results are presented for each municipality and structured according to the five thematic areas of the analytical framework: space, society, economy, environment, and culture, with sub-themes and all indicators. Table 1 provides a qualitative synthesis of this evaluation by indicating whether sustainability-related topics addressed in MSPs are supported by at least one form of empirical evidence. The table does not represent a scoring or ranking exercise and does not imply causal relationships between planning provisions and observed development outcomes.

4.1. Municipality of Gornja Radgona

The MSP for Gornja Radgona explicitly adopts sustainable development as its guiding principle and operationalises this commitment through several strategic orientations. Core spatial objectives focus on compact settlement development via infill and densification, safeguarding agricultural land and flood-prone areas along the Mura River, reinforcing green infrastructure, and advancing sustainable mobility. The MSP also acknowledges demographic ageing and economic restructuring as long-term challenges, positioning sustainability as a framework for spatial consolidation, environmental risk mitigation, and quality-of-life enhancement, rather than for territorial expansion.

Across the five thematic areas of the analytical framework, sustainability is most concretely articulated in relation to space and environment, moderately addressed in economy and culture, and more weakly operationalised in social infrastructure, particularly with respect to ageing-related spatial services.

Space

Indicators addressed in the MSP: revitalisation of existing settlements, mixed land use, quality of living environment, sustainable mobility strategy, cycling and pedestrian infrastructure, green infrastructure system, and recreational areas.

The MSP prioritises infill development and restricts outward expansion of the settlement. Empirical evidence shows partial implementation: from 2013 to 2023, housing stock rose by 5.1% and average dwelling size by 4.2%, indicating qualitative upgrades over greenfield expansion. A sharp increase in building permits per 1000 inhabitants (+77.7%) suggests intensifying development pressure within existing settlement boundaries.

The MSP promotes sustainable transport through investments in cycling paths and pedestrian infrastructure. However, despite these efforts, private car ownership grew by about 10% during the same period, revealing a gap between policy objectives and actual travel behaviour. The lack of a fully accessible public transport network further constrains progress, highlighting the disconnect between strategic intent and practical mobility outcomes.

Society

Indicators addressed in the MSP: revitalisation of depopulated areas and education and healthcare infrastructure.

The MSP recognises demographic decline and ageing as primary challenges, advocating for settlement renewal and improved service accessibility. Nevertheless, empirical evidence suggests the municipality’s limited ability to reverse structural demographic shifts. From 2013 to 2023, the population fell by 1.2%, natural growth was persistently negative, and the ageing index rose by 41.6%. Household composition shifted markedly towards single- and two-person households.

Municipal investment reports indicate steady support for healthcare and essential social services, in line with MSP commitments to maintain living standards. However, infrastructure tailored to older people—such as care facilities and age-friendly housing—is neither explicitly planned nor prioritised in investments. This leads to only partial achievement of social sustainability goals: while general service levels are upheld, long-term adaptation to demographic change remains insufficiently addressed.

Economy

Indicators addressed in the MSP: employment promotion and sustainable tourism development.

The MSP approaches economic sustainability through diversification, supporting agriculture and industry, and expanding the Mele industrial zone. Employment rates rose by 5.2% during the period, reflecting moderate economic resilience. However, the proportion of residents working within the municipality declined by 16.9%, underscoring a rising reliance on external labour markets and daily commuting.

Tourism indicators are positive, with arrivals up 9.7% and overnight stays up 27.1%. These outcomes reflect MSP goals for nature-based and cross-border tourism, which are supported by investments in public space upgrades and cultural heritage. However, tourism remains supplementary rather than transformative, confirming sustainability as incremental adaptation rather than structural change.

Environment

Indicators addressed in the MSP: protection regimes for flood protection and risk management, renewable energy promotion, energy-efficient renovation, and separate waste collection.

Environmental sustainability is where planning intent and implementation align most closely. The MSP enforces strict development limits in flood-prone areas along the Mura River and embeds environmental protection into land-use regulation. Municipal investments consistently prioritise flood protection, wastewater treatment, energy-efficient renovation of public buildings, and renewable energy projects.

Here, the indicator assessment extends beyond formal adoption: planning provisions translate directly into spatial restrictions, investment decisions, and tangible infrastructure outcomes. Environmental sustainability, thus, acts as a binding constraint rather than being simply a declarative goal in local planning.

Culture

Indicators addressed in the MSP: legal protection of cultural heritage and local cultural programmes.

Gornja Radgona has 156 registered cultural heritage units, all formally protected under national law and incorporated into the MSP. Cultural heritage supports tourism development and town-centre regeneration, with targeted investments in façade renewal, public spaces, and cultural events.

However, the MSP lacks a dedicated heritage management plan or structured historic town-centre framework. As a result, cultural sustainability is pursued selectively through individual projects rather than through integrated governance.

Overall, the evidence suggests that in Gornja Radgona, sustainable development is most successfully implemented when strong regulatory frameworks and external funding are in place (e.g., environmental protection, infrastructure, and energy). In contrast, indicators that depend on behavioural change (mobility), long-term demographic adaptation (ageing), or cross-sectoral coordination (employment localisation) exhibit weaker alignment between planning intentions and outcomes.

This pattern indicates that the MSP primarily serves as a strategic coordination tool—effective at managing spatial constraints and guiding public investment, yet limited in its ability to influence more profound socio-economic change. Here, sustainability provides a framework for managing gradual decline and risk, rather than driving transformative development.

4.2. Municipality of Hrastnik

Hrastnik’s MSP frames sustainable development mainly as a strategy of post-industrial restructuring, spatial consolidation, and environmental remediation. The plan prioritises the redevelopment of degraded industrial and residential areas, protecting sensitive zones along the Sava River, improving public spaces, and strengthening social infrastructure. While sustainability is explicitly acknowledged as a guiding principle, it is mostly expressed in adaptive and mitigating terms that reflect long-term demographic decline and structural economic constraints.

Compared to other municipalities, Hrastnik’s MSP puts stronger emphasis on social cohesion and environmental recovery, while economic competitiveness and demographic revitalisation are addressed more cautiously.

Space

Indicators addressed in MSP: revitalisation of settlements, improvement of quality of living environment, and sustainable mobility strategy.

Spatial development in Hrastnik is primarily oriented toward internal restructuring rather than expansion. From 2013 to 2023, the housing stock declined slightly (–0.9%), while average dwelling size grew (+4.2%), signalling a pattern of selective renovation and consolidation rather than new residential construction.

Despite the MSP’s promotion of sustainable mobility and the prioritisation of public transport, results remain limited. Private car ownership increased by 8.3% (15.8% per 1000 inhabitants), demonstrating persistent car dependency. Improvements to cycling and pedestrian infrastructure have been limited and fragmented, diminishing their effectiveness as alternatives. This demonstrates that the presence of sustainability objectives in planning is insufficient without supporting structural mobility systems.

Society

Indicators addressed in the MSP: revitalisation of depopulated areas and education and healthcare infrastructure.

Hrastnik faces the most acute demographic challenges of the four municipalities. From 2013 to 2023, the population declined by 8.5%, with persistently negative natural growth and net migration. The ageing index rose by 49.7%, and nearly two-thirds of households are single- or two-person units.

The MSP acknowledges these trends and emphasises the need to maintain service accessibility and social infrastructure. Investment data confirm consistent funding for education, social services, and community facilities, including participatory budget projects focused on neighbourhood improvements. However, no spatially explicit strategies for elderly care infrastructure are included in the MSP, nor are such facilities evident in investment priorities. As a result, social sustainability indicators are only partially fulfilled: the municipality manages decline rather than adapting spatial structures to demographic realities.

Economy

Indicators addressed in the MSP: employment promotion, reduction in daily labour migration, and sustainable tourism development.

Economic sustainability in Hrastnik centres on stabilisation and diversification after industrial decline. Employment rates increased by 11.9%, and the number of registered companies rose by 5.2%. However, unemployment remains relatively high, and the proportion of residents employed locally declined by 6%, confirming continued outward commuting.

Tourism has grown strongly, with arrivals up 10.4% and overnight stays up 36.3%, primarily driven by the reuse of industrial heritage and natural landscapes. These results correspond with MSP objectives, indicating selective success in culture- and environment-based regeneration. Nevertheless, tourism does not offset broader employment losses, limiting its role as a transformative driver of sustainability.

Environment

Indicators addressed in the MSP: flood and landslide risk management, energy efficiency, and separate waste collection.

Environmental sustainability is among the more coherently implemented areas. The MSP strictly limits development in landslide- and flood-prone areas along the Sava River. Investments prioritise upgrades to wastewater treatment, drinking water infrastructure, and energy renovation of public buildings.

Renewable energy initiatives have emerged in recent years, but remain small in scale and at an early stage of implementation. Overall, environmental indicators show only moderate alignment between planning intent and implementation, driven more by regulatory requirements and infrastructure funding than by proactive sustainability strategies.

Culture

Indicators addressed in the MSP: legal protection of cultural heritage and local cultural programmes.

Hrastnik has 113 registered cultural heritage sites, most of which are linked to its industrial past. These sites are legally protected and increasingly incorporated into tourism and cultural initiatives. However, like other municipalities, the MSP lacks a comprehensive heritage management plan or historic centre strategy. As a result, cultural sustainability is implemented project by project, rather than through an integrated spatial governance approach.

In Hrastnik, sustainable development primarily serves as a framework for mitigation and adaptation. The MSP effectively coordinates environmental protection and basic service provision, but has limited ability to influence demographic decline, mobility behaviour, or labour market restructuring. Sustainability is operationalised in ways that allow decline to be managed institutionally, yet structural socio-economic trends remain largely beyond planning control.

4.3. Municipality of Kostanjevica na Krki

Kostanjevica na Krki’s MSP adopts a protection-oriented approach to sustainable development, shaped by extensive flood risk and significant cultural heritage value. The plan imposes strict limits on spatial expansion, prioritises settlement renewal within existing boundaries, preserves cultural landscapes, and advances risk-sensitive infrastructure. Sustainability is explicitly defined as balancing environmental constraints with quality of life and economic viability.

Space

Indicators addressed in the MSP: revitalization of settlements, mixed land use, improvement of the quality of the living environment, public open space in new developments, sustainable mobility strategy, promotion of sustainable transport modes, cycling infrastructure, pedestrian infrastructure, green infrastructure system, recreational areas, green spaces, and parks.

Empirical data show a slight decline in housing stock (–1.9%), alongside increased dwelling size (+4.3%) and greater construction activity—reflecting targeted upgrading within tight spatial constraints. Investments in public spaces, cycling infrastructure, and sports facilities align with MSP objectives to improve settlement quality without expanding the built area.

Despite these efforts, private car ownership rose significantly (+17.7%), reflecting limited alternatives in a small, spatially constrained municipality. Thus, sustainable mobility objectives remain only partially effective, constrained by geography and limited connectivity.

Society

Indicators addressed in the MSP: revitalisation of depopulated areas and education and healthcare infrastructure.

Unlike other cases, Kostanjevica na Krki saw modest population growth (+2.3%), driven by net in-migration, though population ageing persists. The number of households increased, especially among single-person households.

Municipal investments strongly support healthcare, education, preschool facilities, and emergency services, demonstrating close alignment between MSP objectives and implementation. However, as in other municipalities, spatial infrastructure tailored to older people is lacking, highlighting an ongoing gap between demographic trends and spatial adaptation.

Economy

Indicators addressed in the MSP: employment promotion, business subsidies and sustainable tourism development.

Economic activity grew sharply (≈+40%), yet the share of residents employed locally declined, confirming continued outward commuting. While the number of businesses increased (+7.9%), unemployment also rose, signalling a persistent structural imbalance.

Tourism performance declined slightly despite the MSP’s emphasis on tourism. Recent investments aim to diversify offerings (such as motorhome infrastructure), indicating that sustainability strategies are still evolving rather than fully consolidated.

Environment

Indicators addressed in the MSP: protection regimes, management and development plans, nature-based solutions, renewable energy promotion, energy-efficient renovation, eco-islands, separate waste collection, and rainwater reuse.

Flood risk is the dominant influence on spatial planning, with around 865.6 ha classified as flood prone. Environmental indicators show strong alignment: investments prioritise flood protection, water supply, waste management, and renewable energy (biomass and solar). Here, sustainability operates as a binding spatial constraint, shaping all development decisions.

Culture

Indicators addressed in MSP: legal protection of cultural heritage and local cultural programme.

With 76 registered heritage units, cultural heritage is systematically protected and integrated into infrastructure and tourism projects. Although no comprehensive heritage management plan exists, heritage considerations strongly shape spatial decisions, making culture a de facto organising principle for sustainability.

In Kostanjevica na Krki, sustainability is primarily shaped by constraints and protection priorities. MSP implementation is most effective in areas where environmental and heritage restrictions are legally binding, whereas economic and mobility objectives remain secondary. In this context, sustainability focuses on safeguarding viability within strict spatial limits rather than pursuing transformative change.

4.4. Municipality of Lenart

Lenart’s MSP sets out the most comprehensive and proactive sustainability framework among the four cases. Sustainable development is articulated as an integrated strategy that combines controlled growth, a polycentric settlement structure, protection of agricultural land, environmental responsibility, and enhanced social infrastructure. Unlike the other municipalities, Lenart explicitly approaches sustainability as a challenge of managing growth rather than decline.

Space

Indicators addressed in the MSP: mixed land use, improvement of the quality of the living environment, sustainable mobility strategy, promotion of sustainable transport modes, cycling infrastructure, pedestrian infrastructure, recreational areas, and green spaces.

Empirical trends strongly support MSP objectives: housing stock rose by 6.6%, average dwelling size by 6.9%, and construction activity by 41.1%. Investments in cycling infrastructure, e-mobility, and road upgrades further demonstrate active implementation.

However, private car ownership rose by 17.6%, indicating that, even under favourable local conditions, sustainable mobility still competes with broader regional travel patterns. Implementation is substantial, but not comprehensive.

Society

Indicators addressed in the MSP: revitalisation of depopulated areas, education, healthcare, and elderly care.

Lenart experienced population growth (+5.2%), driven by positive net migration despite negative natural growth. Household numbers increased significantly, highlighting the municipality’s residential appeal.

Investments strongly align with MSP objectives—health, education, social care, and town-centre regeneration receive sustained funding. Uniquely, Lenart explicitly addresses elderly care in both planning and investment, demonstrating greater demographic responsiveness than its peers.

Economy

Indicators addressed in the MSP: employment promotion and reduction in daily labour migration.

Business activity and company numbers increased substantially, unemployment remains low (3.3%), and labour migration declined (–14.9%). Although commuting continues, Lenart demonstrates the strongest alignment between economic planning objectives and observed trends among the four cases.

Tourism remains modest and complementary, rather than central, which is consistent with MSP priorities.

Environment

Indicators addressed in the MSP: protection regimes, nature-based solutions, renewable energy promotion, energy-efficient renovation, separate waste collection, and rainwater reuse.

Environmental investments prioritise wastewater treatment, waste management, energy efficiency, irrigation systems, and light-pollution reduction.

Culture

Cultural heritage (58 registered units) is actively restored and woven into community projects with targeted funding.

Lenart demonstrates the strongest alignment between MSP intentions, investments, and outcomes. Sustainability serves as a coordinating framework for growth management, supported by favourable demographic trends and robust institutional capacity. Remaining gaps, such as persistent car dependence, are attributable to broader regional dynamics rather than deficiencies in planning.

4.5. Comparison of Municipalities

Across all four municipalities, MSPs consistently incorporate sustainability principles across the five thematic areas. However, the degree of implementation varies. Lenart demonstrates the strongest alignment between planning provisions, investments, and observed trends, while Hrastnik and Gornja Radgona show greater discrepancies, particularly in relation to demographic decline and mobility trends. Kostanjevica na Krki illustrates a protection-oriented sustainability approach shaped by flood risk and heritage constraints.

Presenting evaluation results in tabular form, using a binary (0/1) scoring scheme, provides a clear technical overview of the presence or absence of basic conditions for sustainability implementation across municipalities and indicator themes. Analytical emphasis is placed on the qualitative assessment of each indicator within its territorial context, while the binary notation serves as a synthetic comparative reference.

Table 1.

Qualitative synthesis matrix of sustainability indicator implementation across the four municipalities. The table indicates whether each indicator theme is explicitly addressed in MSPs and substantiated by at least one empirical evidence source (statistical trend or municipal investment). The matrix is not a scoring or ranking tool, but a technical comparative orientation that complements the preceding detailed qualitative analyses.

Table 1.

Qualitative synthesis matrix of sustainability indicator implementation across the four municipalities. The table indicates whether each indicator theme is explicitly addressed in MSPs and substantiated by at least one empirical evidence source (statistical trend or municipal investment). The matrix is not a scoring or ranking tool, but a technical comparative orientation that complements the preceding detailed qualitative analyses.

| Thematic Area | Sub-Theme | Indicator | Gornja Radgona | Hrastnik | Kostanjevica na Krki | Lenart |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space | Housing and construction | Revitalization of settlements | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mixed land use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Improvement of the quality of the living environment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Public open space in new developments | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Transport infrastructure | Sustainable mobility strategy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Promotion of sustainable transport modes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Accessible public transport network | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cycling infrastructure | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Pedestrian infrastructure | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Green and recreational spaces | Green infrastructure system | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Recreational areas | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Green spaces | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Parks | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Society | Demographic structure | Revitalization of depopulated areas | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Social infrastructure | Education | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Healthcare | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Elderly care | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Economy | Economic development | Employment promotion | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Daily labour migration addressed | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Business subsidies | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Tourism | Sustainable tourism promotion | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Environment | Natural heritage | Protection regimes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Management and development plans | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Disaster risk management | Nature-based solutions | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Energy | Renewable energy promotion | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Energy-efficient renovation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Waste and water management | Eco-islands | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Separate waste collection | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rainwater reuse | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Culture | Cultural heritage | Legal protection | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Conservation plan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Historic town centre management plan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Local cultural programme | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

5. Discussion

This study examined how sustainable development principles are embedded in MSPs and implemented in practice across four Slovenian municipalities with distinct development trajectories. Using a qualitative, indicator-based framework, the analysis revealed that sustainability is consistently embedded in statutory planning, but its translation into concrete development outcomes remains uneven.

The findings are presented in relation to the three research questions, focusing on (i) the integration of sustainability principles in MSPs (RQ1), (ii) alignment between planning intentions and observed development trends (RQ2), and (iii) territorial differences in sustainability implementation (RQ3).

5.1. Integration of Sustainability in Municipal Spatial Plans

The analysis shows that all four MSPs explicitly recognise sustainable development as a guiding principle, integrating it across five thematic areas: space, society, economy, environment, and culture. MSPs incorporate provisions for compact settlement patterns, infill development, environmental protection, energy efficiency, and the preservation of cultural heritage. This confirms findings from previous studies that sustainability has become a dominant normative framework in contemporary spatial planning [4,5].

Despite this shared formal commitment, the analysis shows notable differences in how sustainability principles are expressed within the MSPs. Lenart demonstrates the most balanced and coherent approach, giving consistent attention across thematic areas. Gornja Radgona holds an intermediate position, with strong environmental and service-related provisions but less emphasis on long-term demographic and mobility challenges. Kostanjevica na Krki adopts a protection-oriented approach, primarily shaped by flood risk management and cultural heritage preservation. Hrastnik’s framework emphasises regeneration, environmental remediation, and the maintenance of social services in post-industrial contexts.

Overall, while sustainability is formally embedded in all MSPs, the specificity, internal balance, and operational focus of related provisions vary considerably. Sustainability is most clearly articulated in areas where planning competencies are legally enforceable, such as land-use regulation, environmental protection, and infrastructure provision. Conversely, issues requiring behavioural change, long-term socio-demographic adaptation, or cross-sectoral coordination—like sustainable mobility, ageing-related spatial services, or labour market localisation—are generally addressed more abstractly. This supports the view of MSPs as strategic and coordinating tools, rather than comprehensive mechanisms for delivering all dimensions of sustainability [5,14,19].

5.2. Alignment Between Planning Intentions and Development Trends

A central finding of the study is the persistent mismatch between planning intentions and observed demographic, mobility, and employment trends. Although all MSPs formally promote sustainable mobility and local employment, the rise in private car ownership across the municipalities highlights a disconnect between planning intentions and mobility outcomes. Similarly, although demographic ageing and population change are acknowledged, spatial strategies often include provisions for moderate growth or service maintenance rather than explicit, long-term spatial adaptation. This suggests that while alignment may exist in some areas, significant gaps often remain between planned developments and real-world trends.

These mismatches seem particularly apparent in municipalities experiencing structural decline. In Hrastnik and Gornja Radgona, sustainability-focused planning appears alongside continued population loss, ageing, and increasing labour commuting, creating challenges in translating planning objectives into tangible outcomes. Conversely, municipalities with more favourable demographic or economic trends—especially Lenart and, to a lesser degree, Kostanjevica na Krki—exhibit greater congruence between MSP provisions, municipal investments, and observed development across multiple thematic areas.

Importantly, these mismatches do not signify planning failure. Rather, they reflect the inherent limitations of MSP influence in domains shaped by regional, national, or market-driven factors, such as demographic change, labour markets, and mobility systems. In this context, MSPs serve primarily as frameworks for coordination, mitigation, and adaptation rather than as instruments capable of independently directing these complex processes [10,17].

5.3. Territorial Differentiation of Sustainability Implementation

The comparative analysis demonstrates that MSPs function as instruments for steering sustainable development, but their effectiveness is highly context specific. While all MSPs embrace similar sustainability principles, their practical interpretations, priorities, and implementation strategies differ considerably in response to local circumstances. In practice, MSPs’ capacity to guide sustainable development varies depending on local socio-economic realities, environmental constraints, and institutional capacities.

In Lenart, sustainability serves primarily as a growth-management tool, supported by positive migration, robust economic activity, and ongoing investment. MSP provisions here are closely aligned with implementation across several thematic areas. Kostanjevica na Krki, by contrast, exemplifies a protection-oriented approach, with flood risk and cultural heritage constraints driving spatial decisions and rooting sustainability efforts in risk management and preservation. Hrastnik follows a trajectory centred on post-industrial adaptation, environmental remediation, and the maintenance of social infrastructure, but faces significant challenges in reversing long-term demographic decline. Gornja Radgona holds an intermediate position, balancing ecological management and service provision in the face of gradual ageing and increased labour commuting.

These diverse trajectories confirm that “one-size-fits-all” sustainability models are ineffective for municipal spatial planning. The success of sustainability initiatives depends on local socio-economic realities, environmental constraints, and institutional capacities. This supports the view that statutory spatial plans operate within broader governance frameworks rather than as stand-alone agents of change [16,18].

5.4. Key Statements, Structural Limits, and Implementation Gaps in Municipal Spatial Plans

The following key statements regarding MSPs and sustainable development are presented, with a particular focus on their structural limits and the types of implementation gaps identified through analysis:

- MSPs are essential strategic and coordinating tools, providing a necessary normative framework for sustainability. However, their capacity to translate these principles into observable outcomes varies considerably across thematic areas and territorial contexts, underlining their dual nature as both essential and inherently limited instruments.

- MSPs exert their greatest influence in domains where planning competencies are legally enforceable and closely tied to public investment, such as land-use regulation, environmental protection, flood risk management, and the provision of technical infrastructure. In these areas, sustainability objectives tend to be more consistently aligned with observed development trends and investment priorities, underscoring the regulatory and coordinating role of statutory planning.

- Conversely, MSPs display limited steering capacity in domains shaped mainly by structural socio-economic forces and multi-level governance dynamics, such as demographic change, labour mobility, and transport behaviour. Despite the formal inclusion of sustainability objectives related to ageing, local employment, and sustainable mobility, broader regional and market-driven dynamics often override municipal planning influence.

- The analysis demonstrates that implementation gaps in sustainable spatial planning are not uniform; rather, they manifest in three analytically distinct types that limit the effectiveness of MSPs. For example, regulatory implementation gaps can be observed in the weak translation of sustainable mobility objectives into binding provisions.

- This can be seen in municipalities where MSPs promote sustainable transport but lack enforceable measures or infrastructure investments. Investment alignment gaps are evident when planning objectives, such as the provision of elderly care facilities, are formally included in MSPs but are not matched by corresponding allocations in municipal investment reports. Structural context gaps appear most prominently in areas like demographic change or car dependency, where MSP intentions are consistently overridden by broader socio-economic trends or regional labour markets, despite clearly articulated objectives within statutory plans. These examples illustrate how each type of gap arises from specific interactions between planning instruments, investment priorities, and external structural factors.

- Methodologically, the study highlights the benefits of qualitative, indicator-based evaluation approaches that avoid composite indices and enable nuanced interpretation. These methods are especially appropriate for small and medium-sized municipalities, where local territorial factors influence sustainability challenges and standard quantitative rankings may overlook important local dynamics.

6. Conclusions

The study demonstrates that while all MSPs in Slovenia formally incorporate sustainable development principles, their translation into tangible development outcomes varies widely among municipalities. Sustainability objectives are most effectively achieved in policy areas supported by robust regulatory frameworks and targeted public investments, such as land-use management, environmental protection, and infrastructure development. However, persistent challenges remain in sectors influenced by broader socio-economic factors, including population ageing, labour mobility, and car dependency. Municipalities with stable or growing populations tend to show stronger alignment between planning intentions and actual outcomes, while those experiencing demographic decline or structural change face greater implementation challenges. In practice, MSPs primarily function as strategic and coordinating instruments, whose ability to advance sustainable development depends on the interplay between local context, governance capacities, and investment alignment, rather than operating as autonomous levers for transformative change.

Methodologically, the study demonstrates that qualitative, indicator-based approaches tailored to local realities not only prevent the risk of false precision but also enhance the capacity to identify nuanced implementation gaps and their structural origins. These findings carry broader implications: the effectiveness of municipal spatial planning in advancing sustainability can be deepened by pursuing governance arrangements and investment strategies that more directly address context-specific barriers, and by adopting evaluative methodologies capable of revealing both the limitations and potential of planning instruments in diverse territorial settings.

While the empirical findings are grounded in four Slovenian municipalities, the analytical insights of this study extend beyond the specific project context. The indicator framework identifies recurring patterns in the relationship between statutory planning instruments, investment alignment, and structural conditions that are characteristic of many small and medium-sized municipalities operating within European planning systems. In this sense, transferability lies not in replicating outcomes, but in recognising the similar configurations of growth, decline, and constraint in which MSPs function primarily as coordinating rather than transformative instruments.

Limitations of the Study

The study does not attempt to comprehensively measure or rank the overall level of sustainable development in the analysed municipalities. Rather, it is designed to identify patterns, consistencies, and discrepancies between planning intentions and observed outcomes. Consequently, while the findings are not statistically generalizable, they provide analytical insights that may be transferable to municipalities encountering similar demographic, environmental, and economic challenges. By focusing on the processes and outcomes within these cases, the study offers reflective guidance for localities with comparable planning contexts, underscoring the potential for broader relevance beyond the specific municipalities examined.

Additional limitations should be noted. First, the analysis does not establish causal relationships between MSPs and observed development trends, as broader socio-economic and institutional dynamics beyond municipal planning control shape many sustainability outcomes. Second, because spatial planning unfolds over long time horizons while the empirical data cover shorter periods, some planning measures may not yet have produced observable effects. Third, the evaluation relies on secondary data sources and the qualitative interpretation of indicators, which—even with systematic triangulation—may involve some degree of subjective judgment. Finally, the study does not explicitly examine governance processes, political decision-making, or municipal administrative capacity, all of which could influence implementation effectiveness but remain outside the empirical scope of this research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18031408/s1. Table S1. Sustainability indicator framework used for the evaluation of Municipal Spatial Plans.

Funding

This research was funded by the Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Research and Innovation under the grant agreement J7-4641.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| MSP | Municipal Spatial Plan |

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S. Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities? Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1996, 62, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, V.; Stead, D. European Spatial Planning Systems. disP—Plan. Rev. 2008, 44, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Dammers, E. The Territorial Futures of Europe: Introduction to the Special Issue. Futures 2010, 42, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmendinger, P. Planning Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tosics, I. European Urban Development: Sustainability and Governance. Cities 2010, 27, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, R.; Owens, S. Governing Space: Planning Reform and the Politics of Sustainability. Environ. Plan. C 2010, 28, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation. The New Urban Agenda; United Nations: Quito, Ecuador, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Territorial Agenda 2030: A Future for All Places; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- European Commission. The New Leipzig Charter: The Transformative Power of Cities for the Common Good; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Owens, S.; Cowell, R. Land and Limits: Interpreting Sustainability in the Planning Process; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Janin Rivolin, U. Global Crisis and Systems of Spatial Governance: Towards a Comparative Analysis. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 994–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, B. Planning, Law and Economics: The Rules We Make for Using Land; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Faludi, A. European Spatial Planning; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Solly, A.; Berisha, E.; Cotella, G.; Janin Rivolin, U. How Sustainable Are Land Use Tools? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadin, V. Spatial Planning Systems in Europe: Multiple Trajectories. Plan. Pract. Res. 2023, 38, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic Planning as a Catalyst for Transformative Practices. In Encounters in Planning Thought: 16 Autobiographical Essays from Key Thinkers in Spatial Planning; Haselsberger, B., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining Urban Social Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Foth, M.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; da Costa, E.; Ioppolo, G. Towards Smart Sustainable Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103445. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Slovenia. Spatial Management Act (ZUreP-3); Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nared, J.; Razpotnik Visković, N.; Ciglič, R. Sustainable Development Challenges in Slovenia. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2015, 55, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewska, L.; Tölle, A. Towards Sustainable Spatial Development in Small and Medium-Sized Cities: Planning Aspirations and Realities. Econ. Environ. Stud. 2018, 18, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifko, S.; Kosec, M.; Bračič, A. (Eds.) Heritage for Inclusive Sustainable Transformation (HEI-Transform): Experimental Laboratories (RevitLabs); Faculty of Architecture, University of Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bossel, H. Indicators for Sustainable Development: Theory, Method, Applications; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu, D.; Yigitcanlar, T. Integrating Urban Ecosystem Sustainability Assessment. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 34, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, J.A.; Benedek, J.; Ivan, K. Measuring Sustainable Development Goals at a Local Level: A Case of a Metropolitan Area in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Global Urban Monitoring Framework: Metadata and Implementation Guidance; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON EGTC. COMPASS—Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe; ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements; United Nations: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Habitat Agenda: Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements; United Nations: Istanbul, Turkey, 1996. [Google Scholar]