Abstract

The international literature shows significant growth in relation to sustainable rural development in response to ongoing problems. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-RAI) enable projects to be aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this article, we present an empirically grounded analysis of these RAI principles based on in-depth case studies in seven countries (Spain, Ecuador, Peru, Dominican Republic, Bolivia, Colombia, and Mexico). This experience comes from an international project coordinated by the GESPLAN Research Group at the Polytechnic University of Madrid. The Working with People model is incorporated into the methodological process to analyze rural actors’ understanding of the CFS-RAI principles in different countries and in university–business relation contexts. The results show the effectiveness of the WWP model based on the integration of three dimensions—ethical–social, technical–business, and political–contextual—as an effective method for planning sustainable rural development projects in various contexts. The empirical evidence presented indicates that combining the WWP model with the principles of CFS-RAI in rural contexts allows progress toward sustainable development, balancing economic aspects with human, social, and environmental well-being.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development has been on the global agenda for decades and has experienced significant growth as a field of study, establishing itself as one of the most important areas of research. There are numerous challenges [1] to meeting the current needs without compromising future generations [2].

Sustainable development has evolved from economic development to a more holistic approach that seeks to balance social, economic, and environmental dimensions [3,4]. More recently, many have suggested integrating a fourth dimension into sustainable development: governance [5,6].

In this regard, for several years now, governance has become the basic paradigm for rural development programs, projects, policies, and strategies [7].

Rural areas play an important role in sustainable development [8] and, over time, have been exposed to multiple global crises [9], including the COVID-19 pandemic [10,11] which has exacerbated pre-existing problems such as poverty and food insecurity [12], as well as other phenomena such as international migration [13], the population shift from rural to urban areas [14,15], and land grabbing [16,17,18,19]. In the face of these challenges, achieving sustainability in rural regions takes on a key importance [9].

For this reason, international organizations have shown a growing interest in sustainable rural development, integrating human rights and recognizing the promotion of equitable and responsible progress [20,21]. The Committee on World Food Security (CFS), an intergovernmental body of the United Nations coordinated by the FAO, approved the Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems in 2014 [22]. Subsequently, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were approved by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015, as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [23]. Both instruments were created to guide and promote sustainable and responsible interventions that preserve the availability of resources for future generations [24,25].

Approved a year before the adoption of the SDGs, the CFS-RAI principles anticipate and reinforce many of the goals contained in the 2030 Agenda. However, little research has been conducted on how the CFS-RAI principles function as a practical tool for implementing the SDGs in the agricultural and food sectors and for guiding governments, businesses, and institutions in making responsible and sustainable decisions.

In 2016, the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) entered into a collaboration agreement to implement CFS-RAI principles in specific territories through university–business relationships in the fields of agriculture, food, the environment, and climate change.

Within the framework of this agreement, coordinated by the GESPLAN Research Group at the UPM (https://www.ruraldevelopment.es), an RU-RAI Network has been created in recent years, currently comprising 49 universities and 50 companies from 13 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain [26], with the aim of promoting the implementation of the CFS-RAI principles in teaching, research, and development cooperation, as well as through their application in collaborative sustainable and responsible investment initiatives [27].

Following this period of collaboration, this research analyzes the conceptual framework developed by the GESPLAN Research Group, which is recognized for its multidisciplinary approach and extensive experience in the planning and management of sustainable rural development projects [27].

1.1. Rural Development Projects Based on the Working with People Model

Sustainable rural development projects have evolved significantly over the years [28]. In the 1960s and 1970s, the traditional model prevailed, which viewed rural regions as incapable of developing on their own, with a strong emphasis on modernization and economic growth [29]. Given the failure of these models, starting in the 1980s and 1990s, a more people-centered approach emerged, which emphasized local participation, recognizing the importance of endogenous development and the creation of local organizational structures [30,31,32].

An important milestone in this evolution was the LEADER (Liaisons entre activités de Développement de l’Économie Rurale) approach in the European Union in the 1990s. This new perspective emerged in the context of transition, giving way to a postmodern vision of rural development based on a territorial approach, the creation of new participatory local government structures, and decentralized management [32].

This approach also emphasizes social innovation, multilevel governance, and cooperation between local actors, enabling the promotion of sustainable projects that are more adapted to local contexts and the specific needs of each region, with significant impacts on social cohesion and territorial development [33].

Sustainable rural development recognizes people as the central axis of change processes, promoting their active participation in building resilient and equitable territories [34,35,36]. As an integral process, it involves the incorporation of social, cultural, and environmental values that strengthen community cohesion and contribute to improving the population’s quality of life [37].

In this context, rural development projects have incorporated various strategies aimed at strengthening territorial sustainability. Among them are the value chain approaches [38], which promote economic sustainability through productive articulation, and perspectives of territorial resilience [39], which enhance the adaptive capacity of local systems to social and environmental changes.

The “Working with People” model [28,40] is presented as a model that transcends the traditional technical vision of rural development by emphasizing local participation, capacity building, and strengthened governance through alliances between actors in the territory.

The WWP model is primarily being applied within the framework of the European LEADER initiative in collaboration with Local Action Groups in response to a new experimental approach to rural development in the EU [31]. In addition to the specific features of the LEADER initiative, the WWP model incorporates elements of planning as social learning [41,42], the logic of participation [43,44,45], methodologies for formulating and evaluating rural development projects [31,46], and international skills for project management [32,47,48].

Numerous studies have shown that integrating project management skills based on the International Project Management Association (IPMA) standard is a significant factor in the sustainability of rural development projects in contexts other than those of the European Union, enabling the formation of Local Action Groups that can act effectively in diverse rural areas [49,50,51]. Over the years, the WWP model has been successfully implemented in rural development processes in countries across Europe [52,53,54] and Latin America, such as Mexico [32], Peru [55,56], Ecuador [57], Argentina [50], Colombia [58], and Chile [59], where it has contributed to improving rural prosperity. In its latest evolution, it has aligned with the CFS-RAI principles, reinforcing responsible investment practices and their contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals [49,60,61,62,63].

Projects planned and executed using the social learning approach based on the WWP model have therefore been found to be suitable for promoting ethical values of social responsibility and for developing the capacities of the affected population. By placing people at the center of development, they empower them, turning them into leaders of their own development, which contributes to strengthening the social structure and sustainability of rural development projects [64].

Rural development projects based on the WWP model, like rural development itself, are influenced by various factors [65] and integrate a holistic approach from its three dimensions. One of the critical factors is ethical governance, which establishes the necessary framework for planning, executing, and evaluating projects effectively, ensuring teamwork and trust in sustainability [66,67]. Similarly, the development of skills within work teams, and especially among project managers, is a decisive factor for sustainability and is key to the success of projects and rural development [49,50].

1.2. Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-RAI) of the Committee on World Food Security

The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-RAI) are presented as a guide to guide projects toward the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They have been demonstrated to be a strategic framework for orienting investments toward the achievement of the SDGs in rural areas [62,63].

This link between the SDGs and the CFS-RAI is based on five interrelated pillars, known as the 5 Ps: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnerships [23,61]. This structure facilitates the organization and analysis of experiences based on the different dimensions that make up sustainability.

Achieving the SDGs requires concrete actions and responsible investments, particularly in rural areas affected by complex challenges such as climate change, energy, food security, migration, and poverty [68].

For this reason, the FAO led a global participatory process involving various stakeholders from five continents, with the aim of establishing a consensus-based set of principles to enable the achievement of sustainable development. As a result of this initiative, in October 2014, the ten principles of the CFS-RAI were approved [22], designed as voluntary guidelines, focusing on rural areas and promoting sustainable and responsible investment in agriculture and food systems [49,62,63,69].

The multi-stakeholder nature of these principles allows for the active participation of a wide range of actors, including governments, businesses, civil society organizations, universities, and producers, creating a collaborative environment that promotes consistency and effectiveness in interventions. The CFS-RAI principles establish a framework that guides projects toward comprehensive development, ensuring that they contribute effectively to the achievement of the SDGs.

In this process of disseminating, raising awareness of, and implementing the CFS-RAI Principles, since the agreement was signed between the UPM and the FAO in 2016, strategic actions have been coordinated to promote sustainable projects that integrate these principles under the leadership of GESPLAN. The FAO selected the GESPLAN Research Group at the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) for its experience and planning of rural development and sustainable management projects based on the WWP model to promote teaching, research, and links with societies in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain based on these principles. Its extensive network of doctors specializing in Projects and Planning in Sustainable Rural Development, many of them graduates of the UPM, has enabled it to create an innovative approach to the development of rural areas.

In this context, various training initiatives have been developed and promoted by the RU-RAI Network, such as seminars and workshops, which have facilitated the training of various university professors, professionals in the agri-food sector, representatives of public and private organizations, and members of civil society. These activities have contributed to knowledge transfer, capacity building, and the creation of multi-stakeholder dialog spaces for the implementation of the CFS-RAI principles, creating a community committed to sustainable rural development based on these principles.

In this study, an empirical analysis of the implementation of CFS-RAI principles in 11 case studies from seven countries (Spain, Ecuador, Peru, Dominican Republic, Bolivia, Colombia, and Mexico) was conducted to present collaborative experiences of sustainable and responsible investments that are being continuously developed. The case studies and the criteria by which they were selected are presented in Section 2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Case study selection.

To apply and integrate the CFS-RAI principles into rural development projects, this study proposes a metamodel based on the WWP model. Eleven case studies conducted in different countries and contexts formed the basis for the comparative analysis that supports the proposal, providing a diverse set of empirical data and territorial contexts for its formulation. The metamodel integrates the principles as a guiding framework and links them with participatory governance processes, territorial planning, and capacity building, contributing to sustainability and improving decision-making in rural development projects.

1.3. Research Questions

To guide the analysis of the application of the Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-RAI) in sustainable rural development projects, the following research questions were posed:

- How do the CFS-RAI principles contribute to sustainable rural development in different international contexts?

- How can the CFS-RAI principles be integrated into the Working with People (WWP) model to contribute to sustainable rural development?

- How do university–business relationships influence rural actors’ understanding and adoption of the CFS-RAI principles?

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach used is the WWP model [28,40], which has been applied to implement the CFS-RAI principles in various contexts, in collaboration with universities, businesses, and civil society.

2.1. Working with People Model

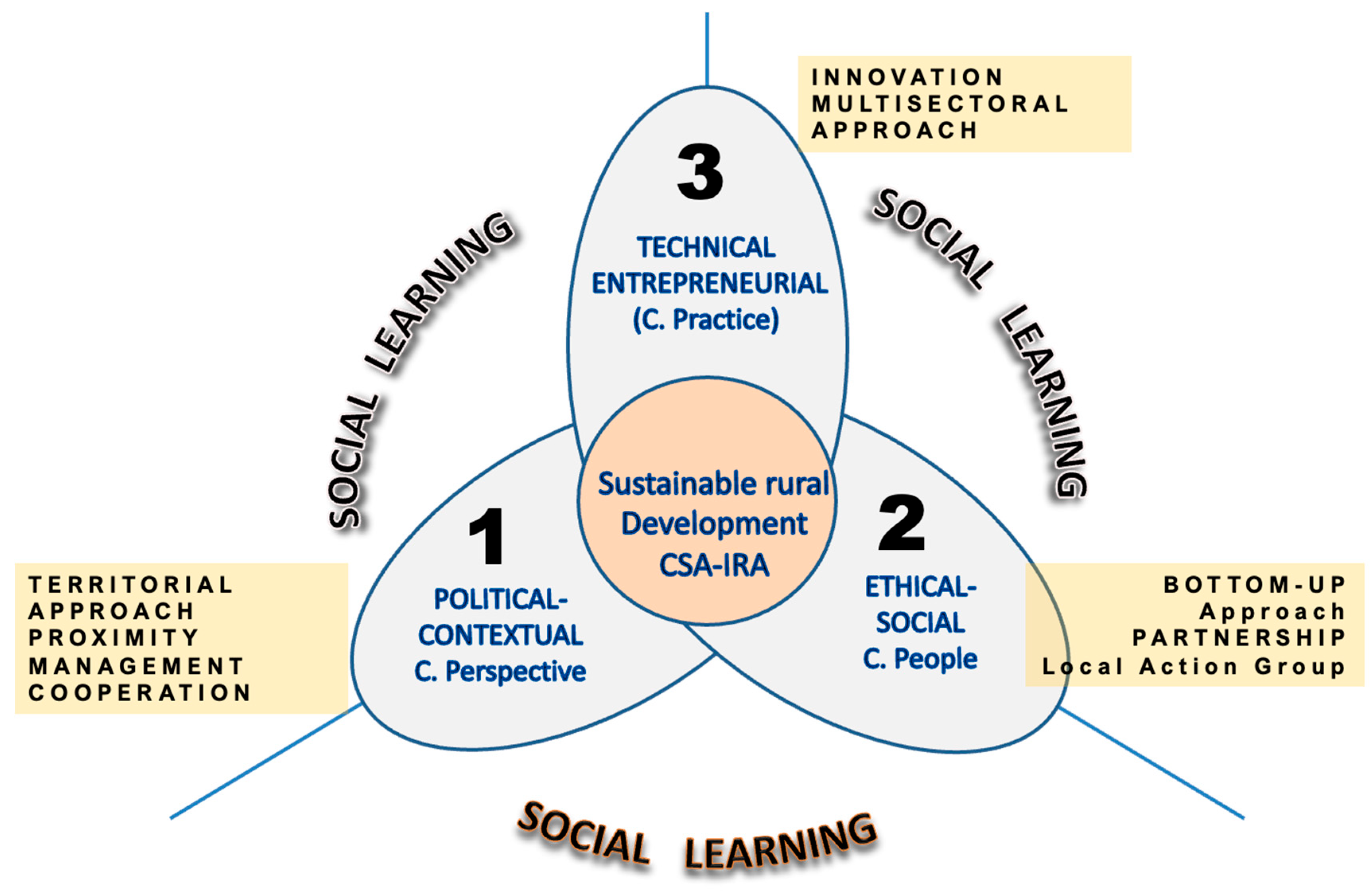

The WWP model prioritizes the value of people in the planning of sustainable rural development projects and the connection between knowledge and action from its three dimensions: political–contextual, ethical–social, and technical–entrepreneurial [40].

This WWP model integrates the specific features of LEADER [31] and the development of project management skills [47,48], contributing significantly to the sustainable development of various rural areas [28,70].

The specific features of the LEADER approach comprise seven elements [31,71]: (a) a bottom-up approach; (b) a territorial approach; (c) a comprehensive and multisectoral approach; (d) innovation; (e) the creation of Local Action Groups (LAGs); (f) proximity management and financing; (g) learning in collaborative networks [31,72].

On the other hand, IPMA (International Project Management Association) competencies are structured in three dimensions: (a) personal competencies (People), related to behavior, social skills, and the ability to lead and work with others; (b) technical competencies (Practice) necessary for managing projects and programs; and (c) contextual competencies (Perspective), related to understanding the project environment and its alignment with the organization’s strategic objectives [47].

The WWP model seeks to connect knowledge and action through its three dimensions or components as follows.

The political–contextual dimension encompasses the capacity of different actors to build relationships with political organizations and international, regional, and local public administrations in the context in which they operate. This dimension considers the territorial approach and proximity management of the LEADER approach for sustainable development [56] and the IPMA’s perspective on competency. The implementation of CFS-RAI principles begins with this dimension, providing the essential framework for the political support, resources, and collaborative environment necessary for the successful implementation and long-term sustainability of projects.

The ethical–social dimension includes the behaviors, attitudes, and values of the people involved in actions at the personal and collective levels. It constitutes a system of social relations based on people’s moral attitudes and behaviors that enable effective teamwork and cooperation among actors through commitment, trust, and personal freedom. It is related to the personal competencies area of the IPMA model and to the bottom-up approach and partnership building of the LEADER approach. The processes of awareness raising, participation, and empowerment of local communities for the integration of the CFS-RAI principles correspond to this dimension. The creation of the LAG partnership promotes coordination and strategic planning for the efficient management of development projects [62].

The technical–entrepreneurial dimension allows the different actors involved to be the main source of innovation and to create products and services for society in accordance with quality standards based on their technical skills. It focuses on promoting business strengthening and integrates the practical skills of the IPMA model for execution. It connects with the multisectoral and innovative approach of the LEADER approach to generate synergies and added value for the project. This technical–entrepreneurial dimension is also considered crucial for success and sustainability based on the CFS-RAI principles.

Finally, the social learning component provides the WWP model with an integrative component to ensure the space and processes for learning among the different subsystems, which leads to learning change agents.

Figure 1 summarizes these three dimensions of the WWP model with the specific features of LEADER [28,40] for the process of integrating CFS-RAI principles based on the WWP model and learning among multiple stakeholders from different areas of politics, public administration, business, universities, and civil society.

Figure 1.

Synergies of the WWP model and the LEADER approach. Source: Adapted from [28].

Each actor, through their own behavior, attitudes, and values, interacts and contributes to the process of integration and learning, contributing, and receiving knowledge from technical, organizational, and political practices and changes [40].

2.2. Case Studies

This research is based on 11 case studies within the framework of the international FAO-UPM project coordinated by the GESPLAN Research Group at the UPM, in which the CFS-RAI principles from the WWP model were integrated. The cases were implemented in various contexts over the eight years of research by the international network. The criteria used to select the 11 case studies were as follows:

C1: Common conceptual framework: all case studies incorporated the WWP model to implement the CFS-RAI principles by promoting university–business collaboration.

C2: Relevance and richness of available information: each case study provided important data that enabled us to answer the central research questions related to the application of the CFS-RAI principles in various contexts.

C3: Maturity: the selected cases were sufficiently developed and advanced to offer solid information with accessible, sufficient, and representative data on the implementation of the principles and model in different environments.

C4: Learning: the knowledge gained had to be generalizable, allowing for its application in other contexts and contributing to progress toward the SDGs.

These criteria ensured that the selected cases were representative and added value to the international study.

A total of 15 case studies were identified through the RU–RAI international network. The selection was carried out by the research team applying the criteria described above. After the evaluation, four case studies were excluded for not meeting Criterion 2 (relevance and sufficiency of information) and Criterion 3 (process maturity). Consequently, 11 case studies were included in the final analysis.

Table 1 presents the evaluation results for each case study, showing the compliance with the criteria and the final decision of inclusion or exclusion.

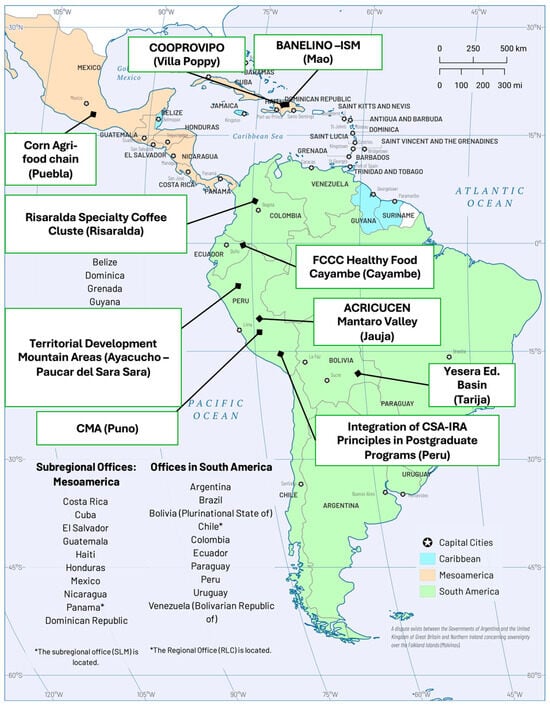

Figure 2.

The body of the figure identifies the territorial location of the 11 case studies on the FAO map of Latin America and the Caribbean Member States UN Geospatial information. Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the FAO map [73].

Figure 2.

The body of the figure identifies the territorial location of the 11 case studies on the FAO map of Latin America and the Caribbean Member States UN Geospatial information. Source: Prepared by the authors, based on the FAO map [73].

Table 2.

Overview of the 11 case studies.

Table 2.

Overview of the 11 case studies.

| Country | Case Study/Key Topics | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | FESBAL-Food Banks: best practices in reducing food waste and responsible consumption. | [61] |

| Bolivia (Tarija, Cercado) | Yesera Educational Basin: Sustainable water resource management by local communities, linking research and local knowledge. | [74] |

| Colombia (Risaralda) | Risaralda Specialty Coffee Cluster: Optimizing the cluster’s logistics, strengthening business capabilities. | [75] |

| Ecuador (Cayambe, Pichincha) | FCCC Healthy Food Cayambe: Cooperation and microcredit for rural women for sustainable food production and marketing. | [76] |

| Mexico (Puebla) | Corn Agri-Food Chain: Comprehensive improvement of the corn agri-food chain in rural communities, strengthening partnerships for the application of CFS-RAI principles. | [77] |

| Peru (Jauja, Junín) | ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley: Formation of the GAL partnership for sustainable practices, innovation, and improvement of the guinea pig value chain. | [49,62] |

| Peru (Puno) | CMA—Aymara Women Artisans: skills development and production and marketing of sustainable artisanal textiles. | [64,78] |

| Peru (Paucar del Sara Sara, Ayacucho) | Territorial development in mountain areas: Territorial model for optimizing resource allocation for sustainable development in mountain areas. | [60] |

| Peru (three ecosystems) | Integration of CFS-RAI Principles into Postgraduate Programs in three ecosystems in Peru: the coast, the Andes, and the Amazon rainforest. | [74] |

| Dominican Republic (Constanza, La Vega) | Villa Poppy–Family Farming: A Family Farming System in accordance with CFS-RAI principles: sustainable practices and partnerships with tourism. | [69] |

| Dominican Republic (Santiago Rodríguez, Valverde, Dajabón) | University–Business Alliance UTESA, BANELINO, ISM: for sustainable territorial development through CFS-RAI principles: family social responsibility program with entrepreneurship. | [79] |

2.3. Data Collection: Instruments and Processes

Mixed methods, combining quantitative and qualitative data, has been used to provide a comprehensive view of the analyzed cases [80]. To this end, primary data obtained through surveys, conferences, and workshops conducted by project teams, local coordinators of the RU-RAI Network, and FAO agents have been used. Secondary sources, such as scientific articles and project monitoring reports, have also been used.

2.3.1. Participatory Process: Conferences, Workshops, and Seminars

During the eight years that the RU-RAI Network has been in operation, conferences and workshops have been held with local actors, academics, organizations, and communities linked to the projects. These participatory spaces have made it possible to capture the perceptions, experiences, and proposals of participants regarding the implementation of the CFS-RAI principles and their impact on sustainable rural development processes. These have reached more than 11,257 direct participants, including 441 entrepreneurs, 1205 teachers and business executives, 218 representatives of public administration bodies, 8868 undergraduate students, and 559 graduate students [26]. Table 3 shows a summary of these key events for promoting the CFS-RAI principles within the framework of the UPM-FAO agreement.

Table 3.

Conferences and workshops to promote the CFS-RAI principles.

2.3.2. Survey of Project Leaders

A survey was designed and implemented in 2024 to collect qualitative and quantitative data on the progress of the projects. The Survey123-ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute) tool in ArcGIS Online software (version 3.20.69) was used. This geocoded platform facilitated the collection, analysis, and generation of data reports [81].

The survey was organized into four thematic blocks:

- Project characterization: identification of stakeholders, collaborating entities, and beneficiaries.

- Implemented activities: description of actions carried out to apply the CFS-RAI principles.

- Results and difficulties: main achievements and barriers encountered during implementation.

- Assessment of actions and contribution to sustainable development: a set of items using a five-point Likert scale 1 (very low) to 5 (very high), that measured the level of implementation of the CFS-RAI principles based on actions grouped into the three dimensions of the WWP model (political–contextual, ethical–social, and technical–entrepreneurial), as well as their perceived contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the territory.

Participants were selected through purposive sampling, inviting three profiles for each of the 11 case studies: the academic coordinator, the project manager or operational lead, and an additional key informant (e.g., community leader or representative of an associated organization). This approach ensured triangulation of perspectives and sectoral and territorial representation of the projects analyzed. In total, 33 invitations were sent, and 26 complete responses were obtained, corresponding to a response rate of 78.8%.

The survey was conducted between January and May 2024. The data collected were complemented with scientific publications, technical reports, and records from seminars and workshops in which the project teams presented and discussed their progress, thereby strengthening the internal validity of the study through source triangulation.

Prior to participation, all respondents were informed about the objectives of the research and provided their informed consent. Data collection complied with the ethical guidelines of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) and the FAO.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis integrated quantitative and qualitative information from the results [82,83,84,85], providing a solid analytical framework for testing the validity of the findings. The survey data was downloaded from ArcGIS Survey123 in shapefile format and analyzed using Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365. The information from the conferences and workshops was analyzed using the common methodological framework of the WWP model, grouping the results according to the three dimensions (political–contextual, ethical–social, and technical–entrepreneurial) using the CFS-RAI principles [40,62], as shown in Table 4.

The analysis was based on the 11 case studies. From the conceptual framework of the WWP model, the actions were defined, classified into the three mentioned dimensions, and analyzed in relation to the degree of implementation of the ten CFS-RAI principles using a 1-to-5 scale [86]. From these evaluations, proportional values were calculated, expressed as the relative weight of each dimension across the set of cases and the weight of each action within its dimension, always using the global sum of all valued actions (as the denominator. In this way, the tables present the relative importance of dimensions and actions in the implementation of the CFS-RAI principles.

Table 4.

Relationship between the CFS-RAI principles and the dimensions of the WWP model.

Table 4.

Relationship between the CFS-RAI principles and the dimensions of the WWP model.

| CFS-RAI Principles | WWP Model Dimension 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P-C | E-S | T-E | |

| P1. Contribute to food security and nutrition | X | ||

| P2. Contribute to economic development and poverty eradication | X | ||

| P3. Promote gender equality and women’s empowerment | X | ||

| P4. Enhance the participation and empowerment of young people | X | ||

| P5. Respect the tenure of land, fisheries, forests, and access to water | X | ||

| P6. Conserve and sustainably manage natural resources, increase resilience, and reduce disaster risks | X | ||

| P7. Respect cultural heritage and traditional knowledge, and support diversity and innovation | X | ||

| P8. Promote safe and healthy agricultural and food systems | X | ||

| P9. Incorporate inclusive and transparent governance structures, processes, and grievance mechanisms | X | ||

| P10. Evaluate and address impacts and promote accountability | X | ||

1 WWP Model Dimensions: P-C: political–contextual, E-S: ethical–social, T-E: technical–entrepreneurial. Source: [60].

3. Results and Discussion

The results of 11 case studies across seven countries (Spain, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and the Dominican Republic) are presented here, where the subsections correspond to the main research questions presented in the introduction.

3.1. Contribution of the CFS-RAI Principles to Sustainable Development in the Territories

The implementation of the CFS-RAI principles in different territories suggests a contribution to rural development and to progress toward the SDGs [49,60,61,62,63,76].

Analysis of the case studies shows how application of these principles based on the WWP model has enabled the development of strategies and actions and the consolidation of processes to promote responsible investments adapted to local contexts, ranging from the development of stakeholders’ skills and the creation of university–business partnerships to the transformation and innovation of agri-food systems.

Table 5 shows how the CFS-RAI principles were implemented in each case study according to the initial agreements in each of the projects, and Table 6 provides the overall results according to the three dimensions (political–contextual, ethical–social, and technical–entrepreneurial) of the actions undertaken associated with the CFS-RAI principles.

Table 5.

Integration of the CFS-RAI principles into case studies.

Table 6.

Integration of the CFS-RAI principles into case studies in relation to the dimensions of the WWP model.

The results show a heterogeneous adoption of the principles in the projects developed, with a predominant trend towards P1, P2, and P3 (Table 5), indicating that the projects prioritize food security, sustainable economic development, and women’s empowerment as key determinants. This orientation was chosen in response to research highlighting the role of women in good governance [55] and the critical structural conditions of rural areas in Latin America, marked by high levels of poverty, food insecurity, and inequality [87,88,89]. The focus on these principles is relevant and consistent with the most urgent needs of the territory, in line with what has been pointed out by Woodhill et al. [90], who assert that the future well-being of people in rural areas depends on the transformation of food systems towards more equitable, sustainable, and resilient models.

Similarly, the incorporation of principles P4, P6, P7, and P8 shows a shift toward comprehensive approaches to rural sustainability. Strengthening the role of young people reflects progress in building human capital and the challenge of generational renewal in the context of high socioeconomic vulnerability [91]. At the same time, there has been a gradual adoption of sustainable natural resource management practices, and the valorization of traditional knowledge has lent sociocultural legitimacy to development strategies, integrating local knowledge into technical and organizational processes [92]. In addition, the promotion of healthy and safe food systems is contributing to improved food security and community health in rural areas [93].

Principles P9 and P10, relating to governance, impact assessment, and accountability, are being implemented to a lesser extent, but some projects are beginning to institutionalize monitoring and transparency mechanisms. This process is essential for building trust, legitimacy, and sustainability in rural interventions.

Principle P5 (respect for land tenure, fisheries, forests, and water), while the least developed, is highly relevant in five cases. This low frequency can be explained by two factors: in some contexts, tenure rights are already formalized and therefore do not require direct intervention, while in others, the legal and political complexity of these issues limits community projects’ capacity for action. Previous studies have pointed out that the effective implementation of principle 5 requires profound institutional reform, recognition of customary rights, and inclusive mechanisms of territorial governance [94]. These results should be considered in the context of global challenges such as population growth, increased demands for food, and pressure on natural resources, which require more sustainable and resilient strategies.

At the global level, the political–contextual dimension (P5, P6, P9, and P10) stands out (34.72%), followed by the ethical–social dimension (P1, P3, P4, and P7) (32.66%) and the technical–entrepreneurial dimension (P2 and P8) (32.62%), highlighting the need for the CFS-RAI principles to be implemented with a holistic and balanced approach regarding the three dimensions of the WWP model, as shown in Table 6.

All case studies illustrate processes that contribute to the sustainable development of territories, reflecting not only their technical aspects but also the fact that they serve as instruments for delivering multisectoral initiatives in economic, social, environmental, and governance areas [49,60,61,62,76].

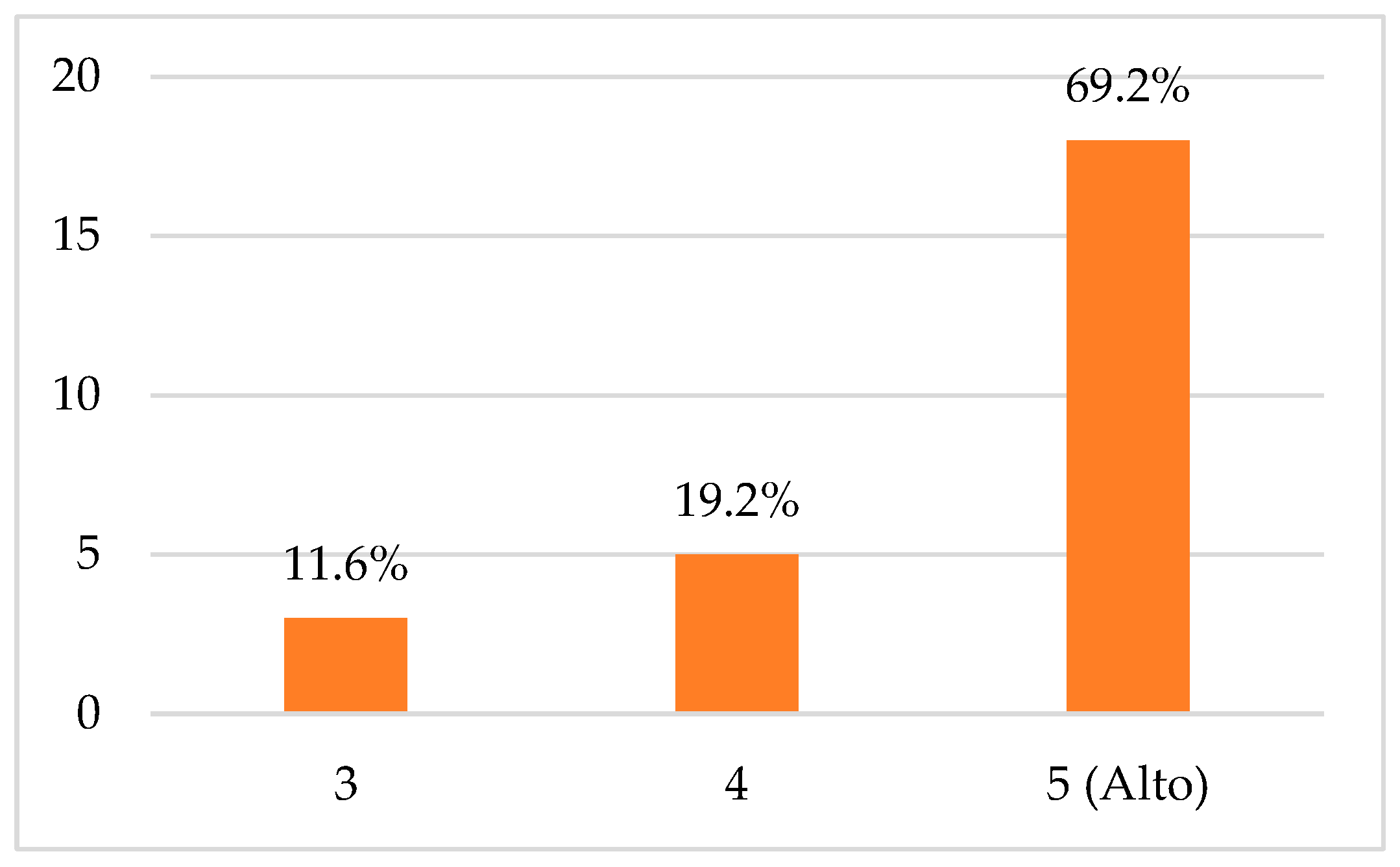

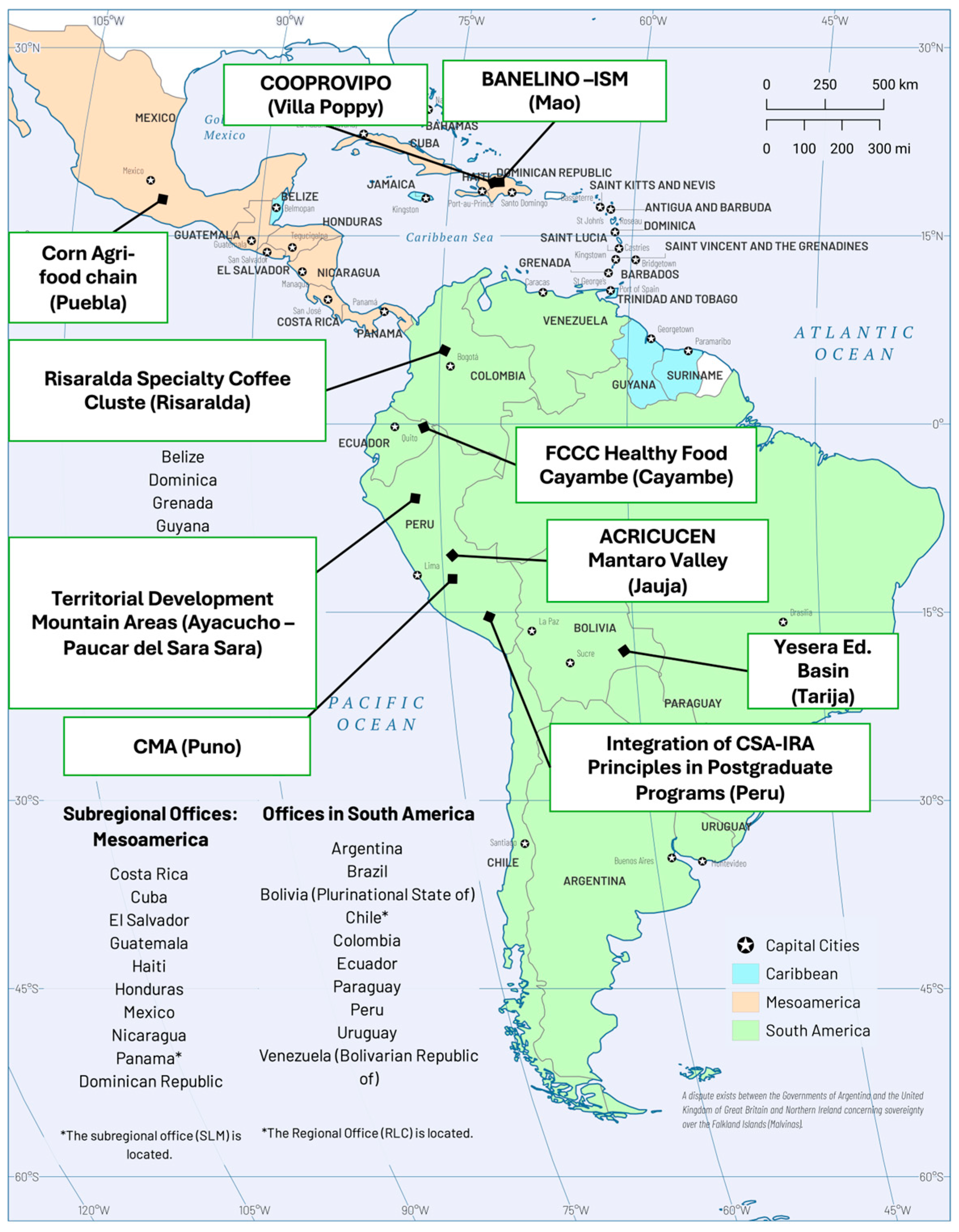

Figure 3 shows the results of local actors and leaders’ assessments of the contribution of these principles to sustainable development, with a significant majority rating their contribution to implementation as high (level 5).

Figure 3.

Perception of the contribution of the CFS-RAI principles to sustainable development.

3.2. Actions from the Political–Contextual Dimension: P5, P6, P9, and P10

Actions from the political–contextual dimension accounted for 34.72% of all those implemented, making it the most prominent dimension among the three dimensions of the WWP model. This dimension emphasizes the importance of understanding and managing the political, regulatory, and contextual structures in which rural development projects are carried out. This dimension also incorporates the perspective competencies defined by the IPMA standard. Actions in this dimension are therefore essential for interventions to be adapted to local realities, with participatory governance structures, greater coordination between actors, and the capacity to respond to the global challenges of sustainable rural development (social, environmental, economic, and political).

Table 7 shows the actions carried out from this political–contextual dimension during rural development projects as a central axis for initiating processes and achieving the sustainability of rural development [28]. Its relevance is evident in the need to form organizational structures to establish solid relationships both internally—among community actors—and externally through partnerships with public, private, academic, and international institutions [95,96].

Table 7.

Main actions from the political–contextual dimension.

The results highlight the central role that governance and institutional coordination processes have come to play in rural areas. Among the most important activities are university–business agreements (6.42%), partnerships for cooperation between agents (6.25%), and the creation of new local–regional governance structures (6.04%), which reflects a sustained focus on building collaborative frameworks between various actors, as shown in Table 8 below.

Table 8.

Main actors in the case studies.

University–business agreements (6.42%) are present in all case studies, playing a key role in linking technical and academic knowledge with the socioeconomic dynamics of the territory, promoting networks with management, innovation, and sustainability capabilities. This link has been consolidated through the exchange of expert and experiential knowledge, as a social learning process characteristic of the WWP model [28,40]. Various researchers agree that universities act as facilitators of sustainable development in rural contexts by actively engaging with local actors [97], promoting co-creation and applied research processes that address real needs [98,99]. In the context of the FAO-UPM project and the CFS-RAI Network [26], university–business agreements are a key strategic component for the implementation of CFS-RAI principles through various engagement processes.

Partnerships and cooperation with other actors (6.25%) are also a key activity in all implemented projects, playing a crucial role in achieving sustainable development by enabling joint learning and synergies between endogenous and exogenous knowledge and in optimizing resources. Collaboration with governments, business entities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and community groups fosters innovation and the alignment of common goals, which, in turn, leads to more comprehensive and resilient solutions [100]. In line with this perspective, the SDGs emphasize the importance of establishing effective public–private partnerships, maximizing the acquisition of experience and the use of resources [23].

These collaborations have also made it possible to create and consolidate local governance structures (6.04%), enabling the creation of innovative interventions consistent with territorial priorities. These types of structures are facilitating the generation of trust and the empowerment of actors, especially women, in line with the notion of “institutional structuralism” proposed by Midgley [101], where multiple actors actively participate in planning and implementing local developments [49,60,62,74,76,77].

As other research shows [64,102], the WWP model reinforces and highlights the need for institutional structuralism, with solid organizations for local governance that guarantee sustainable development processes, especially in contexts where the state does not play an active role. In this sense, universities have played a key role as articulators of technical, scientific, and social knowledge in the different case studies, promoting this institutional structuralism and local governance for participatory planning processes, applied research, local capacity building, and technical support for producers, women, youth, and community associations. Through international cooperation networks and university–business links, they have promoted the transformation of agri-food systems towards more sustainable models, consolidating themselves as key agents in rural development [49,60,74,76,77].

Along with the above actions, associations and cooperatives (5.80%) have been legally formalized to strengthen the institutional legitimacy of producer organizations [62,64,77] as a determining factor for their entry into more demanding markets.

Finally, within this political–contextual dimension, the implementation of impact monitoring and evaluation mechanisms (5.03%) and participation in national and international networks (5.18%) represent relevant aspects for the integration of the CFS-RAI principles and project sustainability. The evaluation of results and accountability is closely linked to building trust among actors, which is a fundamental aspect for the establishment of good governance [103].

In this dimension, the project of the Catholic University Sedes Sapientiae (Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Postgraduate Programs in Peru) stands out. Through training programs, it has incorporated an innovative territorial approach in relation to principle 5 (respect land, fishing, and forest tenure, and access to water) and principle 6 (conserve and sustainably manage natural resources and increase resilience and reduce disaster risks) through rural development actions and by contributing to strengthening the professional capacities aimed at responsible rural development management in three natural regions of Peru (coast, highlands, and jungle). Another case that highlights the high relevance of principles 5 and 6 in the Peruvian context is territorial development in mountain areas [60], which reflects principle 5 by prioritizing land and water tenure and access as key elements of territorial planning, an essential condition for reducing inequalities in rural areas. At the same time, the sustainable and long-term use of these resources in local development plans is encouraged, territorial management is linked with the social and economic stability of communities, and the importance of principles 5 and 6 as a basis for responsible and sustainable investment in highly vulnerable territories is reinforced.

Other relevant principles in this dimension are P9 (incorporate inclusive and transparent governance structures, processes, and grievance mechanisms) and P10 (evaluate and address impacts and promote accountability), which highlight the experiences of FESBAL-Food Banks (Spain), Corn agri-food chain Puebla (Mexico), and ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley (Peru), projects that promote transparent and inclusive governance structures.

In the ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley project (Peru), the implementation of principles 9 and 10 is evident in the creation of an LAG (Local Action Group), a governance space that brings together actors from different levels and sectors through participatory processes. This mechanism has not only improved inclusion in decision-making but also generated trust and social cohesion among producers, institutions, and local governments. Openness to participation and the establishment of strategic alliances have strengthened organizational capacity and commercial innovation, factors that contribute to increased incomes and a better quality of life in rural areas [49,62]. Similarly, Corn agri-food chain Puebla (Mexico), through its LAG, brings together a variety of actors, including producers, public institutions, and academics, who interact through participatory and transparent mechanisms [77]. This formalization of organizations, in addition to strengthening the management of local structures, allows access to new resources, generates greater transparency and legal stability, and promotes participation in production chains [104].

Another innovative case is that of FESBAL-Food Banks (Spain), which stands out for its ability to coordinate with different sectors focused on reducing waste and ensuring food security. In this context, the implementation of principles 9 and 10 of the CFS-RAI principles is reflected in the consolidation of solid, transparent, and inclusive governance structures, positioning them as benchmarks for governance in the third sector [61].

3.3. Actions from the Ethical–Social Dimension: P1, P3, P4, and P7

Actions in the ethical–social dimension represent 32.66% of all actions implemented, making it the second most important of the three dimensions of the WWP. This dimension focuses on building values, attitudes, and behaviors that guide people’s participation in development processes and enable the construction of relationships based on trust, cooperation, and commitment. The ethical–social dimension, through its various actions, is vital because it provides the basis for trust, shared values, and the collaborative relationships necessary to effectively implement projects aligned with CFS-RAI principles, contributing to sustainable development from a human perspective [28].

This dimension relates to the personal competencies of the IPMA standard—leadership, communication, reliability, conflict management, and results orientation—which are key to facilitating participatory processes and empowering the population. The bottom-up approach of the WWP model, aligned with the LEADER approach, reinforces this ethical–social framework by placing communities at the forefront when identifying needs, making decisions, and in rural development planning. This participatory logic has made it possible to establish spaces for dialog between diverse actors—producers, universities, local governments, and businesses—creating environments of mutual trust.

The total number of actions implemented in the case studies reflects their relevance to the rural development processes analyzed, recognizing the need for training to strengthen the social fabric, ethical foundations, and active involvement of communities as necessary conditions for advancing toward the integration of CFS-RAI principles and sustainable development [105,106].

The main strategies promoted in this area are detailed in Table 9, highlighting those aimed at developing skills and capacities, awareness-raising, and training processes as key axes for promoting transformative and sustainable processes in the territories.

Table 9.

Actions from the ethical–social dimension.

Skill development, awareness-raising, and training actions are carried out in the 11 case studies. However, these are not merely support activities but are understood as fundamental and necessary components for the effective implementation of the CFS-RAI principles and the achievement of sustainable development, especially through the empowerment of communities and the construction of ethical and collaborative systems. Both actions are essential for building bridges between “knowledge and action” and are deeply intertwined.

Skills and abilities (7.05%) have been developed in all projects through three international training programs coordinated by the UPM and supervised by the FAO. These programs were based on IPMA standards, focusing on the development of skills in the following different dimensions: practice (project management elements), perspective (contextual understanding), and person (personal and interpersonal skills, including ethical, emotional, and social aspects). These personal competencies are considered essential for success in managing responsible investment projects, in organizational strengthening, and in community leadership [49,62,64,74,76].

Awareness-raising and training processes (6.90%) include educational campaigns, training workshops, and public awareness initiatives. The FESBAL–UPM Food Bank Chair project (Spain) stands out as a far-reaching experience in raising awareness and promoting ethical values aimed at reducing food waste and strengthening solidarity towards vulnerable populations. This experience includes volunteer network and service-learning projects from the university, aligned with the CFS-RAI principles. P1 contributes to food security and nutrition [61], for which the Healthy Food: Cayambe People project stands out, where P1 constitutes the ethical basis, establishing the right to food and food security as central pillars of community management [76].

Mechanisms for active and effective participation (6.53%) stood out for their practices linked to principle 3 (promote gender equality and women’s empowerment), such as those in the Yesera Educational Basin project in Bolivia, which promotes the inclusion of women through their active participation in water management committees and technical training that combines local knowledge and research and their involvement in dialog spaces for the development of a Local Watershed Management Plan. These mechanisms not only recognize their strategic role in water conservation but also strengthen their leadership [74].

Other cases stand out for their practices related to principle 4 (enhance the participation and empowerment of young people), such as FESBAL-Food Banks, where youth volunteering has become a central mechanism for inclusion and learning. Through their active participation in the collection, sorting, and distribution of food, young people have not only contributed to reducing waste but also acquired key skills in leadership, organizational management, and teamwork. This process reinforced values of solidarity and social commitment [61,107].

The promotion of cultural identity and traditional knowledge (6.35%) is visible in the Healthy Food: Cayambe People, CMA Aymaras, and Yesera Educational Basin (Bolivia) projects, where traditional agroecological and textile practices were recovered, revaluing ancestral knowledge as an essential part of their territorial development, as also recognized in principle 7 of the CFS-RAI principles. The CMA Aymara Women Artisans project, for example, focused on strengthening female leadership, with a comprehensive vision that included economic autonomy, the valuation of traditional knowledge, and the construction of networks of trust among participants, allowing for the recovery of weaving as ancestral knowledge and a means of cultural expression. In addition to articulating this knowledge with market colors and trends, new products have been developed for the global market using local production techniques [64].

Finally, the creation of partnerships and Local Action Groups (5.83%) was key in the Corn agri-food chain Puebla (Mexico), ACRICUCEN Mantaro Valley (Peru), Villa Poppy—Family Farming (Dominican Republic) projects, where multi-stakeholder collaboration structures were created to facilitate joint work between producers, institutions, universities, and local governments. These partnerships made it possible to articulate long-term strategies and generate synergies for the inclusive and sustainable development of the territory.

From a theoretical perspective, this approach coincides with that proposed by Friedman [108], who emphasizes that planning processes must be based on personal relationships and shared values that reflect the lived reality of communities. Likewise, various authors highlight that active participation and a sense of belonging strengthen the legitimacy and sustainability of decisions collectively made [109,110,111].

Empowerment in rural development is a fundamental process that enables rural communities to actively participate, make decisions, negotiate, influence, and control key aspects of their environment [112].

All the case studies studied in this dimension strengthened social capital and community cohesion, and social empowerment and active participation were promoted. Women’s entrepreneurship in rural areas is key to sustainable development and social inclusion. Through leading business initiatives, women not only empower themselves but also contribute to reducing poverty, improving family income, and decreasing inequalities, thereby transforming rural communities [113,114].

3.4. Actions from the Technical–Entrepreneurial Dimension: P2 and P8

The main objective of sustainable rural development is to improve the quality of life of rural populations [37]. The technical–entrepreneurial dimension, which accounts for 32.62% of the total actions evaluated in the case studies, comprises a set of activities aimed at strengthening productive capacities, incorporating appropriate technologies, improving the quality of products and processes, and the development of technical–entrepreneurial strategies in line with the conditions of rural areas. It is also linked to IPMA practical skills that enable efficient project implementation. Table 10 shows the main strategies and actions developed in the case studies: transformation and innovation to generate value for products; marketing and access to differentiated markets; logistics management and optimization of production systems; standardized production systems and product quality; product certification; and digitization and improvement of production processes.

Table 10.

Actions from the technical–entrepreneurial dimension.

The most highly valued action was transformation and innovation to generate value for products (6.58%), which suggests the momentum behind strategies aimed at developing new products, diversifying supply, and increasing added value in agri-food chains. Secondly, marketing and access to differentiated markets (6.51%) is a priority in these projects, promoting the competitive positioning of local products in higher value segments and favoring the insertion of small producers into sustainable marketing circuits.

Logistics management and production system optimization (6.46%) highlight the interest in improving operational efficiency and coordination at different stages of the value chain, which helps reduce losses, costs, and distribution times. In turn, the implementation of standardized production systems and product certification (6.54%) shows progress toward compliance with quality, sustainability, and traceability standards, which are increasingly demanded by national and international markets. Finally, the digitization and improvement of production processes (6.53%) mark the beginning of a technological transition that incorporates digital tools for production, commercial, and organizational management, increasing the responsiveness and adaptability of rural actors to the current challenges of the agri-food system.

Based on the analysis of the case studies, projects linked to the implementation of the CFS-RAI principles are being developed in a wide variety of sectors, particularly in agriculture, agri-food, textiles, and academia. This sectoral diversity reflects the versatility of the CFS-RAI principles in different contexts, strengthening both productive innovation and learning and knowledge transfer processes in these territories.

The link between these technical processes and the CFS-RAI principles is clearly expressed. Principle 2, which promotes economic development and poverty eradication, is reflected in the creation of local capacities to sustain autonomous, market-oriented production processes. Principle 8, which advocates for safe and healthy agri-food systems, is observed in the adoption of quality, traceability, food safety, and responsible marketing practices, applied at multiple stages of the technical–productive processes of the projects implemented.

Noteworthy projects in this area include the Risaralda Specialty Coffee Cluster (Colombia), Villa Poppy—Family Farming (Dominican Republic), and the University–Business Alliance UPM-UTESA–BANELINO–ISM (Dominican Republic).

In the case of the University–Business Alliance UPM-UTESA–BANELINO–ISM, the company BANELINO has obtained international certifications such as certification from the Fairtrade Labeling Organization (FLO International), among others, which endorse the social and environmental sustainability of its agricultural production. These achievements have been made possible thanks to continuous technical assistance processes in traceability, agronomic management, and compliance with quality standards. The adoption of these systems requires technical records, control protocols, and the training of producers in management and international marketing [79].

For its part, the Villa Poppy—Family Farming project (Dominican Republic) applied precision agricultural technologies such as weather stations, which have contributed to efficient crop planning. Improved agronomic practices and management tools such as inventory control, sales planning, and production systematization were introduced and integrated into a joint marketing strategy through a local cooperative [69].

In the Risaralda’s Specialty coffee sector project, local capacity building strengthened coffee growers’ autonomy and consolidated market-oriented production processes, contributing to income generation and rural poverty reduction. Likewise, the adoption of quality, traceability, and food safety practices ensured the production of differentiated and competitive coffee, while strengthening safe and sustainable agri-food systems for communities in the region [75].

To highlight the scope and processes developed by the projects analyzed in the technical–business dimension, Table 11 below shows the number of direct beneficiaries in each of the case studies. This information is key to understanding the scale of the initiatives, as well as their contribution to strengthening the productive fabric, boosting the economy, and improving living conditions in the rural areas involved.

Table 11.

Number of direct beneficiaries per case study.

Actions within the technical–entrepreneurial dimension were carried out within the framework of collaborative innovation processes, where local actors actively participate in the adaptation of technical solutions. This approach is in line with that proposed by Pandey et al. [115], who highlight the importance of cooperation for innovation and knowledge appropriation. In turn, the results coincide with the work of Knickel et al. [116] by considering rural innovation as a social process based on networks and collective learning. In addition, the projects featured both extension services and technical training, an aspect that Mapiye et al. [117] identify as key to facilitating the efficient management of productive systems and their sustainability in rural contexts.

3.5. Social Learning Through University–Business Relationships

The results obtained from applying the WWP model to rural development projects suggest its applicability and methodological soundness for addressing rural development project planning. It constitutes a novel methodological approach that allows the complexity of rural development to be addressed from a participatory perspective.

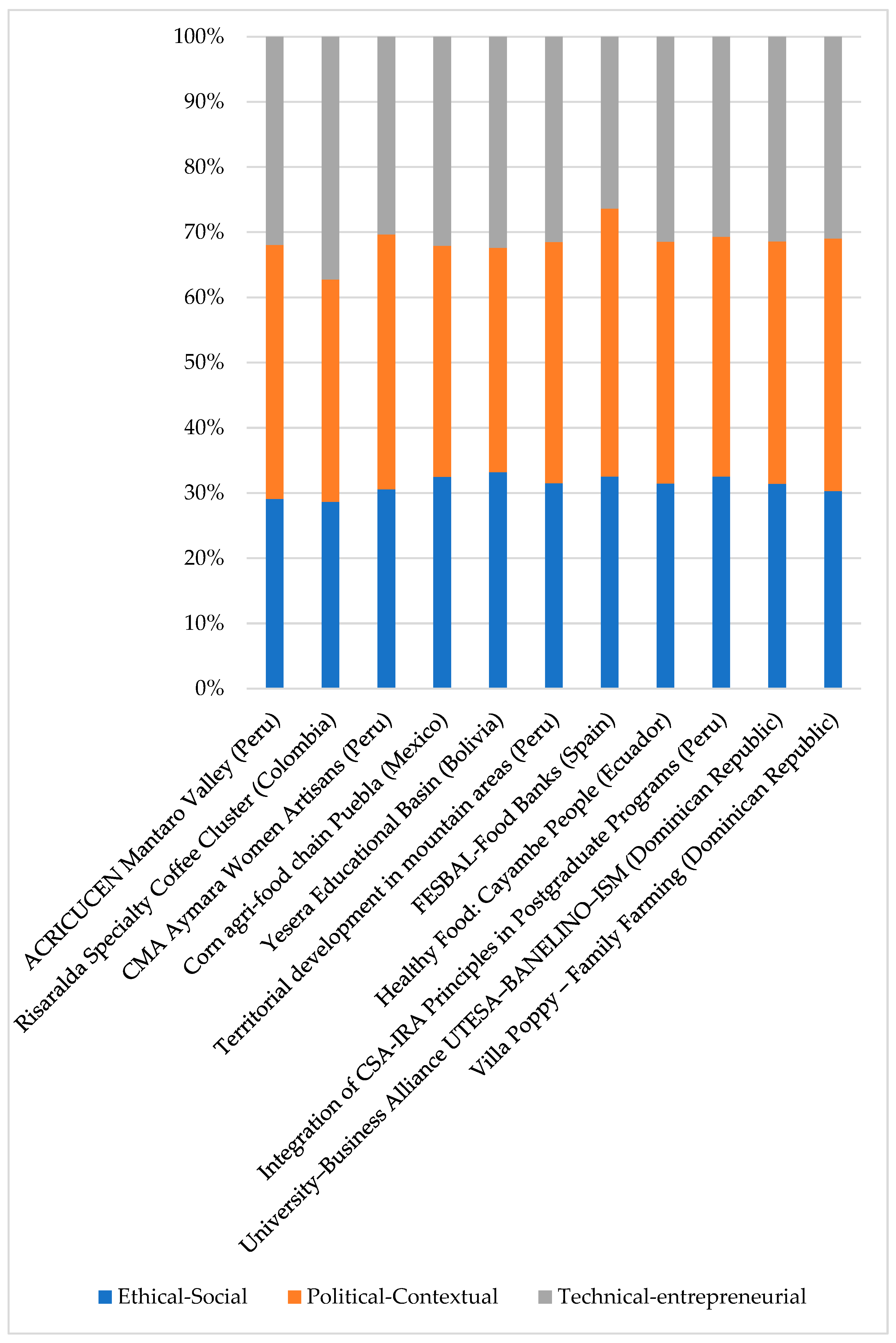

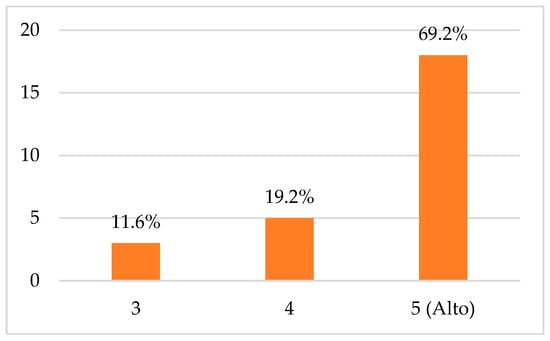

The WWP model seeks to promote a balance between its three dimensions: political–contextual, ethical–social, and technical–entrepreneurial. Figure 4 reflects the degree of balance achieved in the cases analyzed. The results show that, although there is variability between cases, in general, the three dimensions are balanced through processes of social learning, active participation, and institutional cooperation, which are key for the implementation of the CFS-RAI principles and the promotion of sustainable development.

Figure 4.

Balance between the three dimensions (Political–Contextual, Ethical–Social and Technical–Entrepreneurial) of the WWP model in case studies. The results show the total percentage of actions taken in each of the case studies, according to their integration into each of the three dimensions of the WWP model.

The WWP model promotes sustainable rural development by integrating training in IPMA standard competencies, which enables the professionalization of project management in its key dimensions: technical, personal, and contextual. This capacity building contributes to consolidating local leadership, improving resource management efficiency, and creating conditions for organizational and productive autonomy. For its part, the LEADER approach provides a territorial, multisectoral, and participatory framework, notable for its bottom-up approach, which places local actors at the forefront of identifying problems and solutions. The complementarity between the WWP model, the IPMA competency approach, and the LEADER approach reinforces their use in the planning and management of projects aimed at sustainable rural development.

In addition, the Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-RAI) were adopted as a guide to orient actions towards sustainable rural development. Principle 1, linked to food security, was operationalized through strategies that ensured stable and sufficient access to high-quality food. Principle 2, encompassing economic development and poverty eradication, was related to the strengthening of enterprises and value chains. Principles 3 and 4, on gender equality and youth empowerment, were integrated through mechanisms for participation and inclusion, while principle 5, considering respect for land tenure, fisheries, forests, and access to water, together with principle 6—which promotes the conservation and sustainable management of natural resources, increased resilience, and risk reduction—were addressed through the implementation of agroecological practices, efficient technologies, and local knowledge to conserve soils, manage water, and strengthen environmental resilience. Principle 7, relating to respect for culture and traditional knowledge, was incorporated through the valorization of local knowledge and territorial practices, and finally, principles 9 and 10, considering responsible governance and accountability, were integrated through participatory organizational structures, inter-institutional coordination, and transparent monitoring and evaluation mechanisms.

Applying the WWP model, the LEADER approach, IPMA competencies, and the CFS-RAI principles together provides a novel framework for implementing rural development processes aimed at inclusion, sustainability, and capacity building in local territories.

3.6. Limitations

This study presents some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there is a potential selection bias, as the cases analyzed are part of the network and depend on the availability of information provided by those responsible. Second, there is an advocacy risk, since the network carries out both implementation and evaluation functions, which could influence the interpretation of the results. Future research should consider comparative designs with contexts outside the network and complementary methodologies to help reduce these biases and strengthen the validity of the findings.

4. Conclusions

The findings obtained from the analysis of the experiences of the case studies presented suggest that combining the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-RAI) with the Working with People (WWP) model constitutes a solid, adaptable, and innovative methodological proposal. This integration responds to the need to rethink intervention approaches in rural areas, incorporating not only technical criteria but also ethical and social criteria from local contexts.

The WWP model, structured around three dimensions—ethical–social, technical–entrepreneurial, and political–contextual—offers a framework that transcends the instrumental logic of traditional planning. Its application allows development processes to be understood as collective learning experiences, where rural actors are not only recipients of projects but also active protagonists in the formulation, execution, and evaluation of development processes.

The implementation of the CFS-RAI principles has provided a coherent regulatory framework to guide projects toward responsible and sustainable investments. In territories where these principles were incorporated from the project design stage, processes such as community organization, the inclusion of women and young people, and inter-institutional coordination have been strengthened, highlighting their potential to guide local governance processes and promote the creation of Local Action Groups (LAGs) as innovative territorial management structures. The presented case studies show that project progress does not depend solely on the capital invested, but also on the quality of inter-institutional relations, the recognition of local knowledge, and the ability to generate participatory processes.

One of the most significant contributors identified is university–business partnerships, which act as coordinating agents, facilitators of knowledge, and promoters of the sharing of both scientific and local knowledge, thereby facilitating training and innovation.

In short, not only does this methodological combination illustrate innovations in project management, but it also promotes ethical development based on respect for human dignity and social equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: I.d.l.R.-C. and M.L.A.M.; methodology: I.d.l.R.-C. and M.L.A.M.; validation: I.d.l.R.-C., M.L.A.M. and X.N.D.; formal analysis: I.d.l.R.-C. and M.L.A.M.; investigation: I.d.l.R.-C., M.L.A.M. and X.N.D.; resources: I.d.l.R.-C. and M.L.A.M.; data curation: I.d.l.R.-C. and M.L.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation: I.d.l.R.-C. and M.L.A.M.; writing—review and editing: I.d.l.R.-C., M.L.A.M. and X.N.D.; visualization: I.d.l.R.-C., M.L.A.M. and X.N.D.; supervision: I.d.l.R.-C. and M.L.A.M.; project administration: I.d.l.R.-C.; funding acquisition: I.d.l.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through the collaboration agreement between the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) within the framework of the project TCP/RLC/4018 for the implementation of the CFS-RAI Principles in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review by the Polytechnic University of Madrid, as no personal information from the people interviewed and surveyed has been used.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the GESPLAN research group and the RU-RAI university network, whose collaboration and contributions were essential to the development of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Farrukh, M.; Meng, F.; Raza, A.; Tahir, M.S. Twenty-Seven Years of Sustainable Development Journal: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hajian, M.; Kashani, S.J. Evolution of the Concept of Sustainability. From Brundtland Report to Sustainable Development Goals. In Sustainable Resource Management: Modern Approaches and Contexts; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Sustainability and Sustainable Development Research around the World. Manag. Glob. Transit. 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, I.; Ateljević, J.; Stević, R.S. Good governance as a tool of sustainable development. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 5, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M.; Zwolinska-Ligaj, M. The “Smart Village” as Away to Achieve Sustainable Development in Rural Areas of Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Appiah, D.; Zulu, B.; Adu-Poku, K.A. Integrating Rural Development, Education, and Management: Challenges and Strategies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cao, C.; Song, W. Bibliometric Analysis in the Field of Rural Revitalization: Current Status, Progress, and Prospects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumareswaran, K.; Jayasinghe, G.Y. Systematic Review on Ensuring the Global Food Security and COVID-19 Pandemic Resilient Food Systems: Towards Accomplishing Sustainable Development Goals Targets. Discov. Sustain. 2022, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.T.; McConnell, K.; Berne Burow, P.; Pofahl, K.; Merdjanoff, A.A.; Farrell, J. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Rural America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 2019378118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Reflections on China’s Food Security and Land Use Policy under Rapid Urbanization. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, C.; Bartolini, F.; Brunori, G.; D’Haese, M. How Does International Migration Impact on Rural Areas in Developing Countries? A Systematic Review. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busso, M.; Chauvin, J.P.; Herrera, L.N. Rural-Urban Migration at High Urbanization Levels. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 91, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Long, H.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Yang, R. Effects of Rural–Urban Migration on Agricultural Transformation: A Case of Yucheng City, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolford, W.W.; White, B.; Scoones, I.; Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M. Global Land Deals: What Has Been Done, What Has Changed, and What’s Next? J. Peasant Stud. 2024, 7, 1409–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla-Quiñones, P.; Uribe-Sierra, S.E. Rural Shrinkage: Depopulation and Land Grabbing in Chilean Patagonia. Land 2024, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, J. Global Land Grabbing: A Critical Review of Case Studies across the World. Land 2021, 10, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burja, V.; Tamas-Szora, A.; Dobra, I.B. Land Concentration, Land Grabbing and Sustainable Development of Agriculture in Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshanew, S. Rights in the Collaboration between the World Bank and the United Nations in the Areas of Investment in Agriculture, Rural Development and Food Systems. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2023, 27, 1086–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingst, K.A.; Karns, M.P.; Lyon, A.J. The United Nations in the 21st Century; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on World Food Security (CFS). Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/au866e/au866e.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Leal Filho, W.; Tripathi, S.K.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.; Giné-Garriga, R.; Orlovic Lovren, V.; Willats, J. Using the Sustainable Development Goals towards a Better Understanding of Sustainability Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I.; Morioka, S.N.; Sznelwar, L.I. Are We Making Decisions in a Sustainable Way? A Comprehensive Literature Review about Rationalities for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I. Towards a Meta-University for Sustainable Development: Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems. In Proceedings of the XXVIII International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Jaén, Spain, 3–4 July 2024; pp. 1959–1973. [Google Scholar]

- GESPLAN. Principios CSA-IRA: Inversión Responsable En Agricultura y Sistemas Alimentarios En La Universidad y La Empresa. Available online: https://ruraldevelopment.es/index.php/es/docencia-lms/principios-iar-universidad (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I. From “Putting the Last First” to “Working with People” in Rural Development Planning: A Bibliometric Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Planning as Social Learning; IURD Working Paper Series; Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, J.N. My Paradigm or Yours? Alternative Development, Post-Development, Reflexive Development. Dev. Change 1998, 29, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Díaz-Puente, J.M. The LEADER Community Initiative as Rural Development Model: Application in the Capital Region of Spain. Agrociencia 2005, 39, 697–708. [Google Scholar]

- Ottomano Palmisano, G.; Govindan, K.; Boggia, A.; Loisi, R.V.; De Boni, A.; Roma, R. Local Action Groups and Rural Sustainable Development: A Spatial Multiple Criteria Approach for Efficient Territorial Planning. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dax, T.; Oedl-Wieser, T. Rural Innovation Activities as a Means for Changing Development Perspectives—An Assessment of More than Two Decades of Promoting LEADER Initiatives across the European Union. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2016, 118, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, W.; Dirix, J.; Sterckx, S. Putting Sustainability into Sustainable Human Development. J. Human Dev. Capab. 2013, 14, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Başak Dessane, E.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing Nature’s Contributions to People: The IPBES Approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hull, V.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Tilman, D.; Gleick, P.; Hoff, H.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Xu, Z.; Chung, M.G.; Sun, J.; et al. Nexus Approaches to Global Sustainable Development. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Roldan, C.; Méndez Giraldo, G.A.; López Santana, E. Sustainable Development in Rural Territories within the Last Decade: A Review of the State of the Art. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.; Belliggiano, A.; Grando, S.; Felici, F.; Scotti, I.; Ievoli, C.; Blackstock, K.; Delgado-Serrano, M.M.; Brunori, G. Characterizing Value Chains’ Contribution to Resilient and Sustainable Development in European Mountain Areas. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 100, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetta, G.; Ceravolo, R.; Barbieri, C.A.; Borghini, A.; de Carlo, F.; Mela, A.; Beltramo, S.; Longhi, A.; De Lucia, G.; Ferraris, S.; et al. Territorial Resilience: Toward a Proactive Meaning for Spatial Planning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De Los Ríos, I.; Salvo, M. Working with People (WWP) in Rural Development Projects: A Proposal from Social Learning. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla, A.; Friedmann, J. Planificación e Ingeniería: Nuevas Tendencias; Taller de Ideas; Universidad Politecnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, M. Social Learning in Planning: Seattle’s Sustainable Development Codebooks. Prog. Plann. 2008, 69, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, N. Paraprojects as New Modes of International Development Assistance. World Dev. 1990, 18, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. Putting People First: Sociological Variables in Rural Development, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA): Challenges, Potentials and Paradigm. World Dev. 1994, 22, 1437–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falero, E.; Trueba, I.; Cazorla, A.; Alier, J.L. Optimization of Spatial Allocation of Agricultural Activities. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1998, 69, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA. Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme, and Portfolio Management, version 4.0; International Project Management Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.ipma-greece.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/IPMA_ICB_4_0_WEB.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- El-Sabaa, S. The Skills and Career Path of an Effective Project Manager. Int. J. Project Manag. 2001, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Huamán Cristóbal, A.E.; Aliaga Balbín, H.; Marroquín Heros, A.M. Competencies and Capabilities for the Management of Sustainable Rural Development Projects in the Value Chain: Perception from Small and Medium-Sized Business Agents in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratta Fernández, R.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; López González, M. Developing Competencies for Rural Development Project Management through Local Action Groups: The Punta Indio (Argentina) Experience. In International Development; Appiah-Opoku, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Arroyo, F.; Sacristán López, H.; Yagüe Blanco, J.L. Are Local Action Groups, under LEADER Approach, a Good Way to Support Resilience in Rural Areas? Ager 2015, 18, 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.; Cazorla, A.; Panta, M.d.P. Rural Entrepreneurship Strategies: Empirical Experience in the Northern Sub-Plateau of Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Reyes, A.T.; Carmenado, I.D.L.R.; Martínez-Almela, J. Project-Based Governance Framework for an Agri-Food Cooperative. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šūmane, S.; Kunda, I.; Knickel, K.; Strauss, A.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Rios, I.D.I.; Rivera, M.; Chebach, T.; Ashkenazy, A. Local and Farmers’ Knowledge Matters! How Integrating Informal and Formal Knowledge Enhances Sustainable and Resilient Agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]