Abstract

Efficient coordination within the supply chain of prefabricated construction remains a significant challenge due to the high level of interdependence among supply chain participants, the complexity of information flows, and the sensitivity of construction processes to communication delays. This study proposes an integrated methodological framework that combines fuzzy logic and social network analysis (SNA) to evaluate the structural stability and interaction dynamics of supply chain participants. First, a synthetic indicator—link stability—is introduced to quantify the robustness of relationships between supply chain actors. Link stability is defined as a function of five determinants: collaboration level, trust level, communication quality, adoption of digital tools, and effectiveness of dispute resolution. Fuzzy logic is applied to calculate this indicator for each pair of participants, reducing subjectivity in expert assessments. Second, the link stability matrix is used to compute a wide set of centrality measures, including degree, betweenness, closeness, eigenvector, PageRank, information, harmonic, and second-order centralities. These metrics reveal the structural influence of each actor within the network and allow for the identification of core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral roles. A heatmap demonstrates a highly centralized network structure dominated by managerial and design roles. The results contribute to improving supply chain resilience, enhancing communication pathways, and supporting decision-making in prefabricated construction projects.

1. Introduction

The technology of prefabricated construction requires the supply and installation of a wide variety of preassembled components, which demands intensive coordination and collaboration among numerous business units. Consequently, the networked structure of the supply chain becomes complex, multi-layered, risk-prone, and inherently uncertain, making supply chain stability an essential requirement. Recent global events further emphasize that today’s world is highly volatile and unpredictable. The very mechanism of supply chain functioning contains internal risks of unexpected disruptions. To minimize these risks, supply chains must be multidimensional and multidisciplinary, designed to ensure preparedness for critical events, the ability to respond effectively, and the capacity to recover to their original—or even improved—state after a disruption.

The concept of stability originates from physics, and Holling introduced it into ecological studies in 1973, emphasizing the importance of a system’s ability to absorb disturbances without undergoing structural transformation. Inspired by his work, scholars expanded the concept to other disciplines—engineering, economics, psychology, sociology—to describe the behavior of complex dynamic systems under uncertainty. In its broad interdisciplinary meaning, stability describes the degradation and subsequent recovery of system performance caused by various threats [1].

In the supply chain literature, the term “stability” lacks a single universally accepted definition. Ponomarov and Holcomb described supply chain stability as the ability to anticipate risks, respond to disruptions, and recover afterward [2]. Other definitions emphasize the capacity of an enterprise to maintain stability, adapt, and thrive under dynamic conditions [3], or the ability to proactively organize and design supply chain structures that prevent random disruptions [4]. Rajesh and Ravi highlighted flexibility as the core of stability, describing it as the ability to respond effectively to diverse changes in the supply chain [5]. An integrated view defines stability as the proactive capacity to plan and design supply chain networks to prevent unexpected failures. Given increasing political, economic, and social uncertainties, which raise the likelihood of supply chain disruptions, scholarly interest in this topic has grown substantially.

Researchers have proposed different classification schemes for supply chain stability. Azevedo et al. [6] identified three levels—internal, supplier, and customer—based on potential disruption points. Hohenstein et al. [7] distinguished four dimensions: event preparedness, response, recovery, and growth. Birkie et al. [8] divided stability into internal and external anticipation and passiveness, while Bhamra et al. [9] emphasized three forms: workforce stability, organizational stability, and structural stability.

Several quantitative approaches have also been developed. Xu et al. applied fuzzy decision-making, decision laboratory analysis, and network analytics to examine interactions among stability indicators based on the literature and expert evaluation [10]. Musavi and Hosseini introduced a modeling-based quantitative method for assessing supply chain stability under different disruption scenarios [11]. Chen et al. developed an environment-oriented stability measurement model focusing on supply chain cost elements [12]. Cunhua proposed a stability indicator system tailored for prefabricated construction supply chains using interval fuzzy indexes, AHP, and barrier degree analysis [13].

On the inter-organizational level, Brandon et al. (using data from 264 UK enterprises) confirmed the significance of information-sharing resources, supplier–buyer linkages, and cooperative relationships for improving supply chain stability and reliability [14]. From a managerial perspective, Colicchia conducted empirical analyses revealing the determinants of supply chain stability, including leadership capability, effective information dissemination, customer relationships, inter-organizational collaboration, and overall management competence [15]. Shang Jing and Chen Min examined the impact of digital technologies on stability and proposed targeted strategies for improvement [16].

Despite a growing body of literature, studies on stability in prefabricated construction remain limited. Shishodia et al. defined stability in prefabricated construction supply chains as the ability of project-related organizations to survive, adapt, and perform under risky, uncertain, and volatile conditions [17]. In this study, supply chain stability in prefabricated construction is defined as the capability to remain stable under normal conditions, rapidly recover from disruptions, and adapt to changes in a dynamic environment [18].

Scholars have also attempted to identify the factors influencing stability in prefabricated construction. Zhu et al. grouped 15 key factors into six categories associated with different stages: supply chain level, design units, component manufacturers, logistics companies, contractors, and supervisory bodies [19]. Lu et al. summarized similar factors into six high-level clusters: risk management, inventory management, contingency planning, visibility, environmental risks, and information technologies [20]. Ji divided factors into component design adaptability, managerial competence of module manufacturers, logistics reliability, and construction personnel expertise. Kabirifar applied the TOPSIS method to prioritize stability-related factors in large-scale housing projects [21]. Other researchers identified 57 stability indicators and organized them into five domains: procurement processes, operational efficiency, relational coordination, strategic alignment, and corporate social [22,23]. In the context of information cooperation, authors [24] structured stability attributes into four groups: information collaboration, stakeholders, external stability mechanisms, and digital technologies.

Synthesizing findings from the literature reveals several patterns. First, most research focuses on the manufacturing sector, whereas the construction industry—and prefabricated construction in particular—remains underexplored. Second, much of the existing research is qualitative and grounded primarily in theoretical reasoning, which limits its practical applicability. Third, many studies adopt a static view of stability, overlooking its dynamic nature, which depends on evolving internal and external conditions.

Despite the growing body of literature on supply chain resilience and coordination in construction, existing studies differ substantially in terms of analytical focus, treatment of uncertainty, and level of relational detail. Table 1 summarizes and compares representative studies across construction, prefabricated construction, and general supply chain management, highlighting their analytical scope and limitations.

Table 1.

The comparison of representative studies across construction, prefabricated construction, and general supply chain management.

The extended comparative analysis further confirms that recent studies on prefabricated construction increasingly acknowledge the importance of coordination and digitalization but still rely predominantly on actor-level or project-level assessments using crisp analytical methods. Even when advanced modeling techniques are applied, relational uncertainty and interaction quality between participants remain largely unaddressed.

By contrast, the present study advances the state of knowledge by introducing a link-level stability construct grounded in fuzzy logic and embedding it within a weighted network framework. This integration enables a more nuanced understanding of both relational robustness and structural influence in prefabricated construction supply chains.

Based on integrated insights from the literature, the following key factors influencing the “link stability” in a supply chain can be identified:

Level of collaboration. Collaboration acts as the integrative mechanism connecting supply chain participants and reducing uncertainty. It is closely related to visibility and requires willingness to share even sensitive or confidential information.

Level of trust. Trust forms the foundation of supply chain management, enhancing collaboration, reducing conflict, and improving joint decision-making under uncertainty. Lack of trust is a key driver of supply chain risks.

Quality of communication. Critical attributes include timeliness, accuracy, bidirectionality, and adequacy of information exchanged among supply chain nodes.

Use of digital tools. Digital technologies increasingly support communication, coordination, transparency, and operational efficiency in construction, reducing time and cost while improving accuracy.

Effectiveness of dispute resolution. The ability to resolve conflicts swiftly and constructively reduces stress, prevents fragmentation, and maintains productivity within the supply chain.

The selection of the five determinants: collaboration level, trust level, communication quality, level of digital tools adoption, and effectiveness of dispute resolution, was guided by a synthesis of prior research on construction supply chain resilience, coordination, and organizational stability. Previous studies consistently identify collaboration and trust as core relational enablers affecting coordination effectiveness and risk propagation in construction networks [38]. Communication quality is widely recognized as a critical mechanism for mitigating uncertainty, resolving design changes, and synchronizing interdependent tasks, particularly in prefabricated construction contexts characterized by high coupling [39]. Digital tools adoption (e.g., BIM platforms, shared information systems) has been repeatedly associated with improved transparency, coordination speed, and error reduction across supply chain interfaces, while dispute resolution effectiveness reflects the institutional capacity of a supply chain to absorb conflicts without disrupting production flows [40]. Together, these determinants capture relational, informational, technological, and governance dimensions of supply chain interactions, which are jointly emphasized in the construction management and supply chain resilience literature. Finally, effective dispute resolution and conflict avoidance are recognized as critical for maintaining continuity of project delivery and preventing escalation that disrupts schedules and material flows [41]. The selected set was therefore considered sufficiently comprehensive for representing the dominant mechanisms influencing link stability in prefabricated construction supply chains, while maintaining a balance between conceptual completeness and practical measurability in expert-based assessment settings.

Thus, this article presents an interdisciplinary research study that

- (1)

- Proposes a synthetic indicator “link stability” for assessing the stability of the supply chain, defined as a function of five determinants: the level of collaboration, the level of trust, the quality of communication, the degree of digital tools adoption, and the effectiveness of dispute resolution;

- (2)

- Computes the link stability indicator using fuzzy logic techniques, thereby reducing the subjectivity associated with individual expert judgments;

- (3)

- Applies network analysis methods to calculate various centrality measures that capture the influence and structural importance of each supply chain participant.

The systematization and integration of these methodological approaches constitute the principal scientific and practical contributions of this study.

The object of the research is the supply chain within the context of prefabricated construction. The following research tasks were defined:

- (1)

- To develop a synthetic index for evaluating supply chain stability in prefabricated construction;

- (2)

- To calculate the link stability index for each pair of supply chain participants using fuzzy logic;

- (3)

- To analyze key centrality metrics derived from the link stability matrix, in order to assess the structural importance of individual participants.

Addressing these tasks contributes to solving the broader problem of improving the efficiency and coordination of delivery processes in prefabricated construction supply chains.

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide practitioners and researchers in the construction industry with a structured approach to strengthening communication and enhancing collaboration among supply chain participants.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodological framework, including data collection, the computation of the “link stability” indicator using fuzzy logic, and the determination of the principal centrality metrics for network nodes; Section 3 reports the results of the study, covering the calculation of link stability and the evaluation of centrality measures; and Section 4 provides an integrated discussion of the findings and concludes the paper.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The initial stage of the study involved collecting data from supply chain participants through a survey. A survey is a method of data collection in which questions are posed to specific groups of individuals. It makes it possible to obtain information not only about facts and events but also about respondents’ opinions and evaluations. Unlike written correspondence, a survey provides more systematized and accurate information. In addition, it broadens the range of information sources by engaging those who may not be inclined to express their views voluntarily. The survey concerned the construction process of a multi-family residential building with a total area of approximately 3600 m2.

The empirical study is based on a single prefabricated residential construction project and includes responses from 50 participants representing key supply chain roles. The sample size was determined by the number of actors directly involved in coordination, information exchange, and decision-making processes within the project at the stage of peak interaction intensity.

In network-based studies of construction projects, analytical relevance is primarily driven by coverage of relational structures rather than statistical representativeness in a population-based sense. The collected sample captures the majority of active coordination links within the project network, which is sufficient for exploratory analysis of interaction patterns and relative actor influence.

The achieved sample size (N = 50) is consistent with typical ranges reported for expert-based surveys and instrument development studies, where the emphasis is placed on expertise and information richness rather than statistical representativeness of a general population [42]. Data cleaning followed predefined rules. Incomplete submissions and responses with missing values for the core items were excluded, and duplicate entries (if any) were removed. Additionally, responses showing clear invalid patterns (e.g., contradictory answers across key items or non-differentiated “straight-lining” across all factors) were screened out. After cleaning, the final dataset used for analysis contained 50 valid responses.

The research was conducted with the consent and full support of the investor. All key stakeholders of the project agreed to participate in the study and were informed of its results. The study took place at a stage when most of the construction works had already been completed and when the concentration of supply chain participants was at its highest.

The primary task during the data collection phase was the identification of existing connections (links) between participants. In a construction supply chain, a link is any information and communication relationship between organizations or individuals involved in production, delivery, construction, or related processes. Links within a supply chain may exist between manufacturers, distributors, contractors, service providers, or end users who interact with one another.

Accordingly, the stability of a link in the supply chain refers to the ability of that link to function without interruption, even in the case of unforeseen events or disruptions [43]. The stability of each link is essential for the overall stability of the construction supply chain [44].

Links between participants were established based on reported communication relationships. A link was considered present if at least one of the involved parties reported communication related to project execution. This conservative rule reflects the practical reality of construction projects, where information exchange may be asymmetric and not equally perceived by both parties.

Although communication processes are inherently directional, the present study models links as undirected. This choice was made to focus on the stability of relationships rather than the directionality of information flow, which is consistent with the exploratory and structural objectives of the analysis. To identify the links, a questionnaire was used in which respondents were asked to select the participants with whom they had communicated. “Communication” was understood as the use of any verbal method (face-to-face conversations, telephone, zoom, etc.) or any other available form of communication (such as email, messaging applications, and so on). The purpose of this communication was to resolve issues related to the implementation of the supply chain: introducing changes to planned works, modifying execution deadlines, addressing missing elements in drawings, correcting errors in the design documentation, and similar matters. If respondents provided a positive answer to the first question, the next task in the data collection phase was to assess the factors that influence the indicator of “link stability”. Based on the analysis of the set of factors influencing “link stability”, the following determinants were identified: the level of collaboration, the level of trust, the quality of communication, the level of digital tools adoption, and the effectiveness of dispute resolution.

Respondents were asked to assess the perceived influence of each determinant on the stability of a given relationship rather than the absolute level of the determinant itself. This formulation reflects the fact that participants can more reliably judge how strongly specific factors affect collaboration outcomes than quantify abstract relational states. Such influence-based assessments are particularly suitable for fuzzy logic modeling, which is designed to accommodate subjective and imprecise judgments.

The five determinants were treated as conceptually distinct input variables representing different dimensions of supply chain interaction. To avoid introducing additional subjectivity at the modeling stage, equal weighting was initially assumed within the fuzzy inference system. This assumption reflects the exploratory nature of the proposed framework and is consistent with prior fuzzy-based decision-support studies in construction management.

To assess the robustness of this assumption, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by perturbing the relative importance of the input determinants within plausible ranges and examining the stability of the resulting link-stability rankings.

The degree of influence of each of the five factors was selected by respondents using a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, where “0” indicated no influence and “4” represented the maximum level of influence.

Participation in the survey was voluntary, and all respondents were informed about the purpose of the study and the anonymous treatment of their responses. No personal or sensitive data were collected, and the study did not involve interventions or experiments on human subjects. Therefore, formal ethical approval was not required under applicable national regulations.

2.2. Using Fuzzy Logic to “Link Stability” Indicator Calculation

The development and application of fuzzy inference systems involve several stages implemented through the fundamental principles of fuzzy logic [45]. Measured input variables corresponding to real control processes are supplied to the input of the fuzzy inference system, while the output consists of the resulting variables, which likewise represent the variables of the control process [39]. Fuzzy inference systems are used to transform the values of input variables into output variables based on fuzzy rules. To accomplish this, such systems must include a database of fuzzy rules and perform fuzzy inference according to conditions expressed in the form of fuzzy linguistic statements [46]. To assess the robustness of the rule base, sensitivity checks were conducted by selectively perturbing rule consequents and examining the stability of link-stability rankings. The results indicate that moderate variations in rule definitions do not significantly affect the relative ordering of links, supporting the robustness and interpretability of the fuzzy inference system.

To calculate the indicator of “link stability,” the Mamdani algorithm was employed—one of the earliest and most widely used algorithms in fuzzy inference systems. The Mamdani algorithm includes the following steps [47]:

- Formation of the rule base for the fuzzy inference system.

- Fuzzification of the input variables.

- Aggregation of conditions in accordance with the fuzzy rules. To determine the degree of truth of each rule’s conditions, pairwise fuzzy logical operations are applied. Rules whose degree of truth is non-zero are considered active and are used in subsequent computations.

- Activation of the consequents in the fuzzy rules, where only the active rules are taken into account in order to reduce computation time.

- Accumulation of the conclusions of fuzzy production rules. This is performed using the formula for the union of fuzzy sets that correspond to the terms of the consequents associated with the same output linguistic variables.

- Defuzzification of the output variables, traditionally carried out using the centroid (center of gravity) method.

The fuzzy rule base was constructed using a monotonic and symmetric expert-driven design. “Monotonic” means that improving any input determinant (e.g., increasing collaboration while keeping other inputs unchanged) cannot decrease the inferred link stability. “Symmetric” means that all five determinants were treated with equal priority in the inference logic; no determinant was assumed a priori to dominate the others. The consequents were assigned to reflect the intuitive principle that higher overall interaction quality corresponds to higher link stability, while very low values in multiple determinants result in low link stability.

The rule base was screened for logical contradictions and monotonicity violations. Specifically, we verified that (i) rules with uniformly higher input terms do not yield lower output terms compared to otherwise identical rules, and (ii) extreme combinations behave as expected (e.g., “very low” inputs across determinants map to “low/very low” link stability, whereas “high/very high” inputs map to “high/very high” link stability). These checks ensure internal coherence of the rule base and reduce the risk of unintended “black-box” behavior.

2.3. The Methodology of the Principal Centrality Metrics for Network Nodes

The supply chain can be represented as a graph, in which the degree of each node is determined based on the adjacency matrix. The adjacency matrix of a graph with n nodes is a square matrix A of size n, where the value of the element aᵢⱼ corresponds to the number of edges from node i to node j.

Multiple centrality measures were employed to capture complementary aspects of actor influence within the supply chain network. Degree-based measures reflect direct interaction intensity; closeness centrality captures access efficiency to other actors; betweenness centrality highlights brokerage and control over information flows; while flow-based and eigenvector-related measures reflect the capacity to influence network performance through indirect paths.

The use of multiple indices was motivated by the heterogeneous nature of coordination mechanisms in prefabricated construction, where influence may arise from both direct communication frequency and strategic intermediary positions. No single centrality metric is sufficient to fully represent these roles.

Accordingly, the degree centrality of node i can be calculated using the following formula [48]:

Betweenness centrality is calculated as the ratio of the shortest paths that pass through a given node to the total number of shortest paths in the network [49]:

where is the number of shortest paths from node k to node j that pass through node iii; and is the total number of shortest paths from node k to node j.

The closeness centrality of a node is calculated by the following formula [50]:

where —sum of geodesic distances from node i to other nodes of the graph.

The eigenvector centrality for node i is proportional to the sum of the centralities of its neighbors i and can be calculated by the following formula [51]:

where —adjacency matrix element; —eigenvector centrality of node j; —eigenvalues of the adjacency matrix A, and − the largest of them.

The PageRank centrality of a node is calculated by the following formula [52]:

where —constants, —number of edges coming out of the node j.

Centrality measures based on the concept of the “shortest path” are often criticized because their computation assumes that flow moves strictly along the shortest routes. The flow-based betweenness centrality measure, in contrast, is grounded in the analogy of electric current flowing through a circuit, where each edge weight is treated as conductance, that is, the quantity inverse to resistance [53]. A unit of current is introduced into the network at the source node i, while simultaneously a unit of current is removed at the target node l. It is assumed that electric current flows from higher to lower potential. When a unit of current is added at i and removed at l, the current passes through the path j → k. The intermediate current associated with node k is defined as the amount of current flowing through node k, averaged across all possible source–receiver pairs i and l.

The concept of closeness (flow) centrality is also based on the physical properties of electric current and is defined by the following formula [54]:

Loading centrality for is defined as

Second-order centrality can be calculated as follows [55]:

The information centrality for a node is given by

where —the path centrality from node i to j.

Harmonic centrality is calculated by the following formula [56]:

where —the shortest distance between v and u.

3. Results

3.1. The Determination of the Indicator “Link Stability” Using Fuzzy Logic

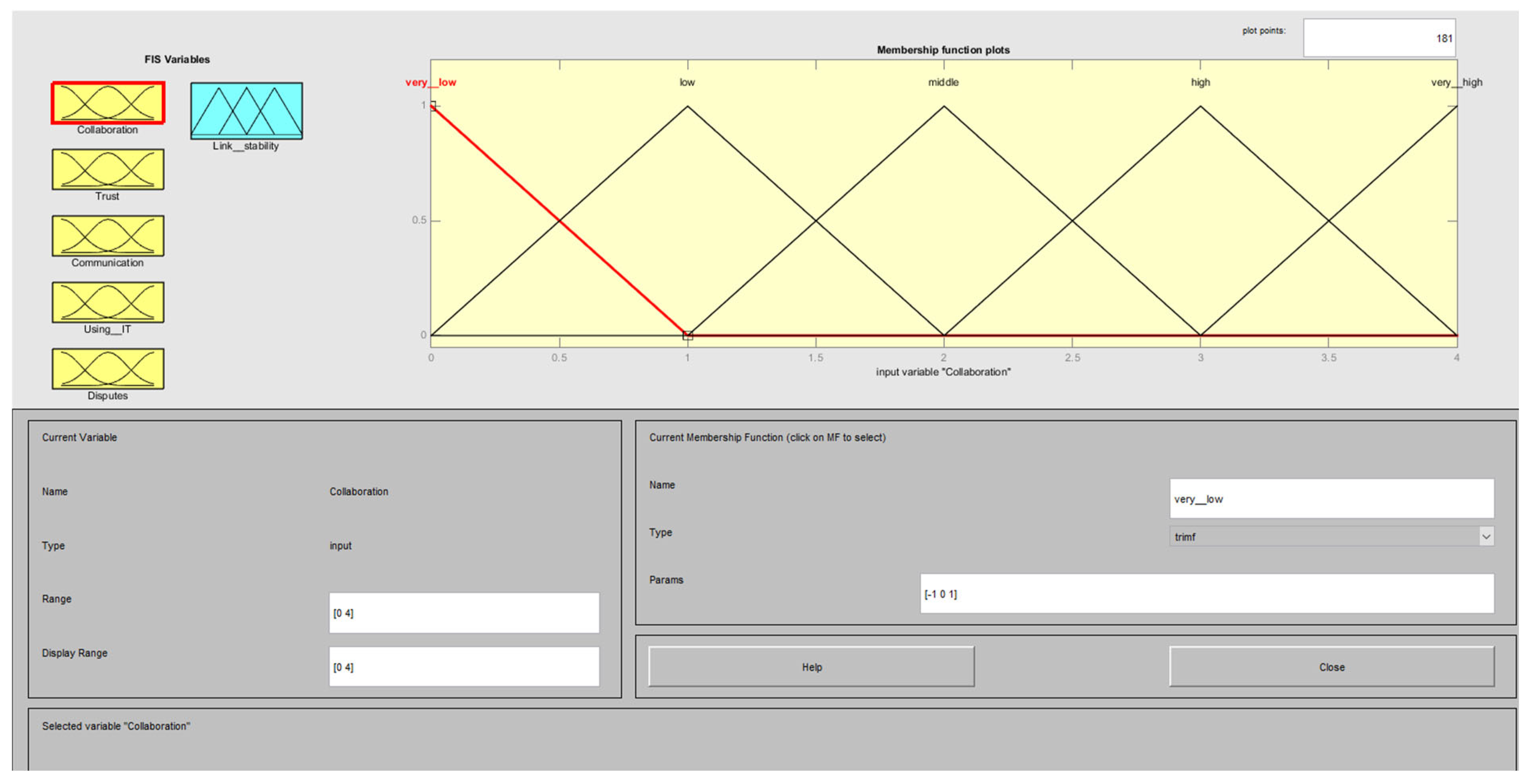

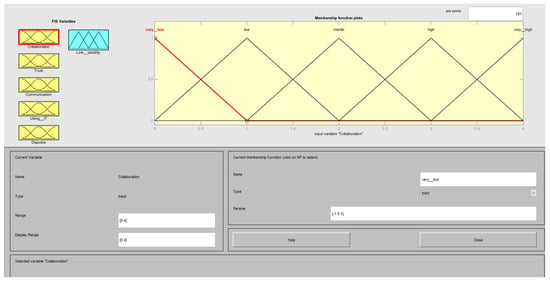

The calculation of the link stability indicator was performed using fuzzy-logic tools implemented in the Fuzzy Logic Toolbox of Matlab R2015b. Each input variable was defined by five linguistic terms, with corresponding membership ranges assigned as follows: very low [−1 0 1], low [0 1 2], middle [1 2 3], high [2 3 4], and very high [3 4 5].

To verify the consistency between linguistic terms and expert perception, the definitions of the membership functions were reviewed by domain experts involved in the study. The experts confirmed that the numerical representations adequately reflected their understanding of qualitative terms in the context of supply chain interactions. This qualitative validation supports the semantic interpretability of the fuzzy model.

Triangular membership functions were selected for all input and output variables due to their simplicity, interpretability, and widespread use in fuzzy decision-support systems applied to construction management problems. Triangular functions provide a transparent linear mapping between linguistic terms and numerical ranges, which is particularly suitable when expert judgments are elicited using discrete Likert-type scales.

The boundary values of the input membership functions were aligned with the original 0–4 Likert scale used in the survey. Overlapping ranges were intentionally introduced to reflect gradual transitions between adjacent linguistic terms and to avoid artificial discontinuities in inference. For example, the term “middle” partially overlaps with both “low” and “high,” capturing the inherent ambiguity of expert perception in assessing interaction quality.

The output membership functions for link stability were defined on a normalized scale [0, 1], with extended support beyond this interval to reduce edge effects during defuzzification. This design ensures smooth aggregation of fuzzy consequents and stable centroid-based defuzzification.

Figure 1 illustrates an example of a triangular membership function defined for the factor “Collaboration”.

Figure 1.

An example of a triangular membership function defined for the factor “Collaboration”.

In the proposed fuzzy inference system, the values of each linguistic variable are processed using a set of fuzzy logic rules, which transform the input parameters into the output linguistic variable. After fuzzification, the next stage of the inference procedure involves aggregating the partial results generated by the rule base: all rules are activated simultaneously, and their outputs are combined into a single final decision through the fuzzy inference mechanism. The fuzzy inference system was constructed using an expert-driven rule design reflecting practical knowledge of interactions in prefabricated construction supply chains. Each rule follows a standard IF–THEN structure, linking combinations of the five input determinants to an output linguistic assessment of link stability.

Given five input variables and five linguistic terms per variable, the complete combinatorial rule space consists of 3125 possible rules. However, to maintain model interpretability and avoid redundancy, only 125 representative rules were implemented, covering the most practically relevant interaction patterns observed in expert assessments (there are in Supplementary Materials). The remaining combinations correspond to extreme or rarely occurring scenarios and do not materially affect the inference results.

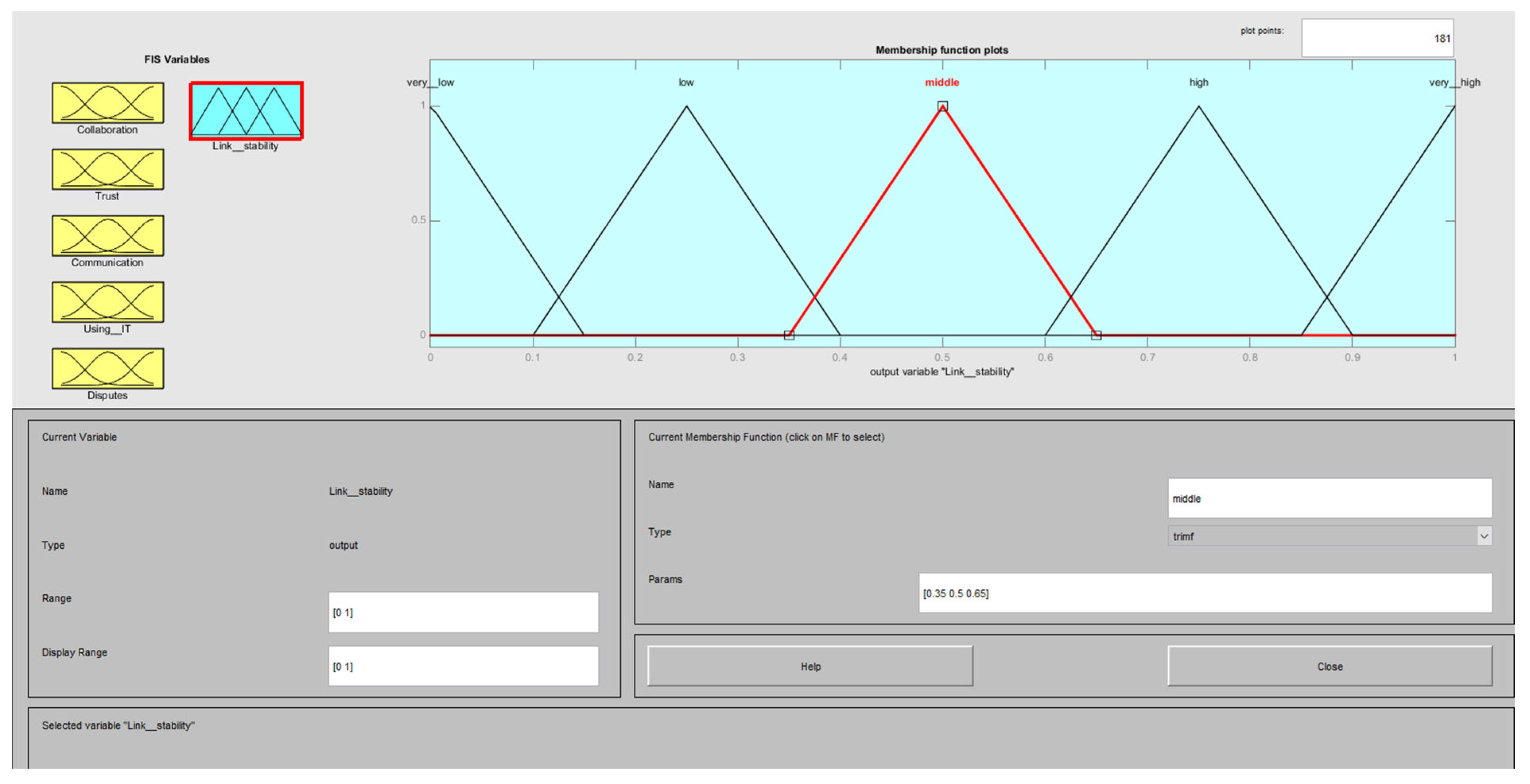

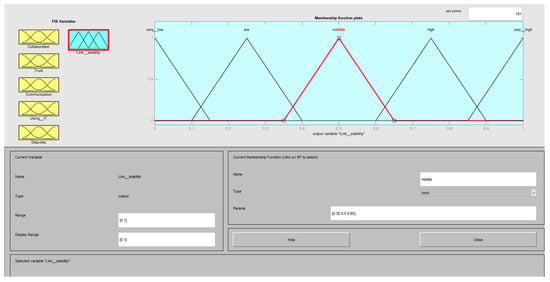

The rule base was validated through expert consistency checks, ensuring logical monotonicity (i.e., increasing input quality does not decrease link stability) and internal coherence across similar rule structures. To obtain a crisp output value, the centroid defuzzification method was employed, in which the final result corresponds to the center of gravity of the aggregated output fuzzy set. The output variable was described using five linguistic terms with the following ranges: very low [−0.15, 0.001, 0.15], low [0.10, 0.25, 0.40], middle [0.35, 0.50, 0.65], high [0.60, 0.75, 0.90], and very high [0.85, 1.00, 1.15]. Figure 2 presents an example of a membership function corresponding to the output linguistic term “middle.”

Figure 2.

Example of a membership function corresponding to the output linguistic term “middle”.

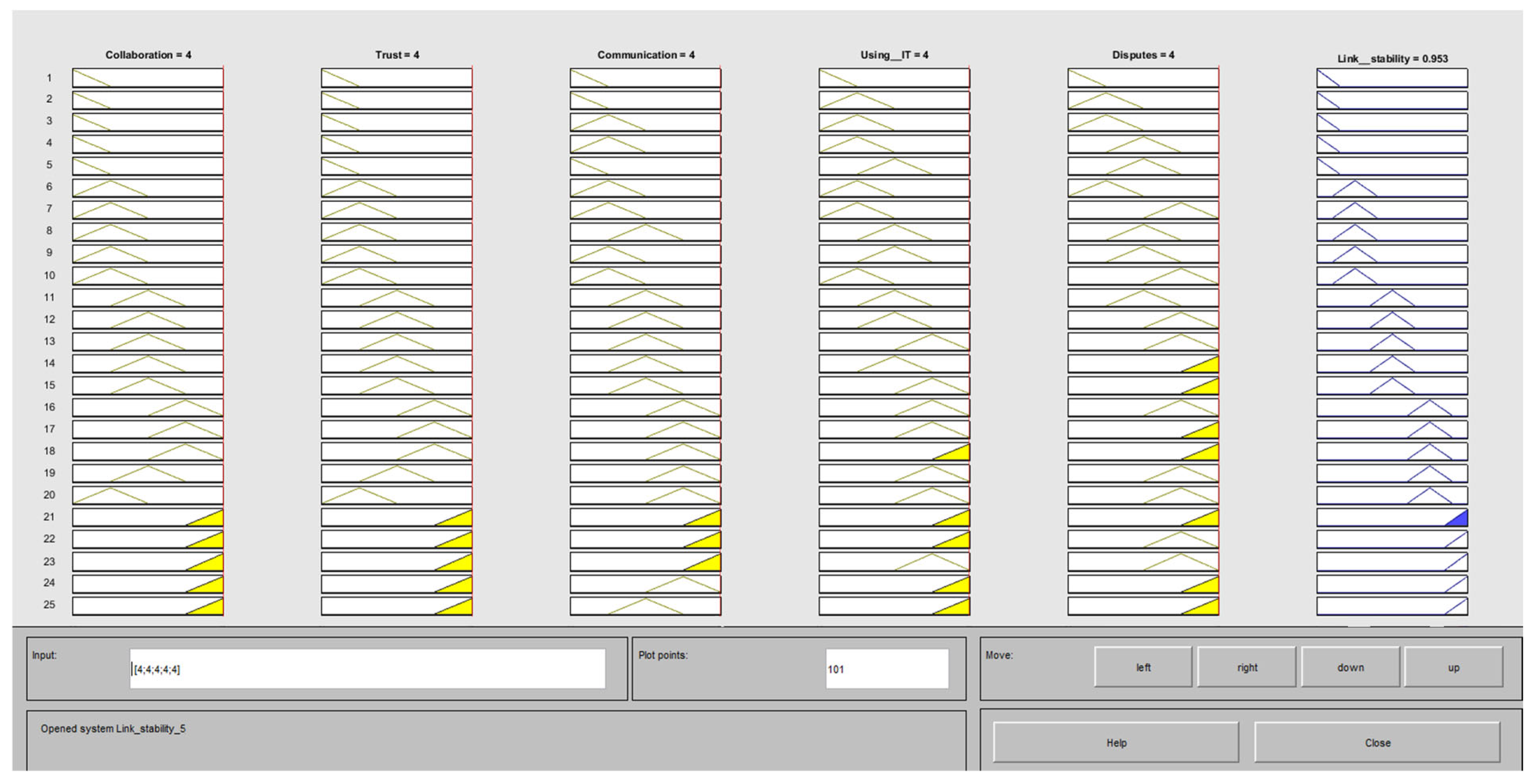

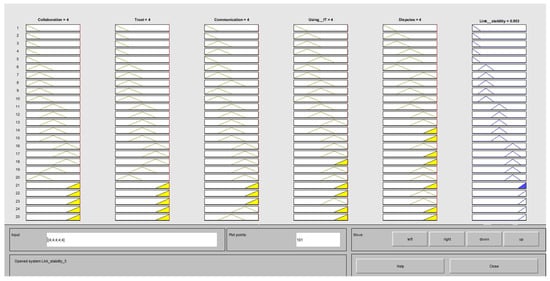

The final stage of the fuzzy model involves defuzzification, during which the linguistic fuzzy output variables are converted into precise numerical values. For example, according to Figure 3, for the maximum values of all input parameters [4; 4; 4; 4; 4], the resulting value of the output variable (link stability) is 0.953.

Figure 3.

Example of defuzzification for input variable values [4;4;4;4;4].

Sensitivity analysis indicates that moderate variations in determinant weights do not materially alter the relative ordering of link stability values, suggesting that the model outcomes are not driven by a single dominant factor. This supports the internal robustness of the proposed indicator under alternative weighting assumptions. Selected examples of the results obtained at the defuzzification stage are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected examples of the results obtained at the defuzzification stage.

In this way, 50 questionnaires completed by respondents were processed, and the final values of the link stability indicator were calculated.

To address concerns regarding the empirical credibility and construct validity of the computed link stability values, a set of descriptive and robustness-oriented statistical analyses was conducted using the full link stability matrix derived from the fuzzy inference system.

The analysis was performed on all off-diagonal elements of the 25 × 25 link stability matrix (N = 600 links), excluding self-links (there is in Supplementary Materials). The following descriptive statistics were computed: mean, median, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation.

The computed link stability values range from 0.000 to 0.953, indicating a wide spectrum of interaction strength within the supply chain network. The mean value equals 0.250, while the median equals 0.000, reflecting a sparse network structure in which many actor pairs exhibit no or very weak interaction, and a limited subset of links concentrates relatively high stability values.

The standard deviation amounts to 0.342, and the coefficient of variation (CV = 1.37) confirms substantial dispersion of link stability values. This high variability demonstrates that the proposed indicator does not produce uniform or trivial numerical outputs, but meaningfully differentiates between weak, moderate, and strong supply chain relationships.

To further assess the robustness of the link stability indicator, rank-based sensitivity tests were conducted using Spearman correlation. First, the weighted network was compared with a binarized representation obtained using a threshold value of 0.5. The resulting Spearman correlation equals 0.825 (p < 0.001), indicating strong consistency in the relative ranking of links across different network representations.

Second, a perturbation analysis was performed by introducing random ±10% noise to all link stability values. The Spearman correlation between the original and perturbed values equals 0.998 (p < 0.001), demonstrating near-perfect stability of link rankings under moderate input uncertainty.

3.2. The Determination of the Principal Centrality Metrics for Network Nodes

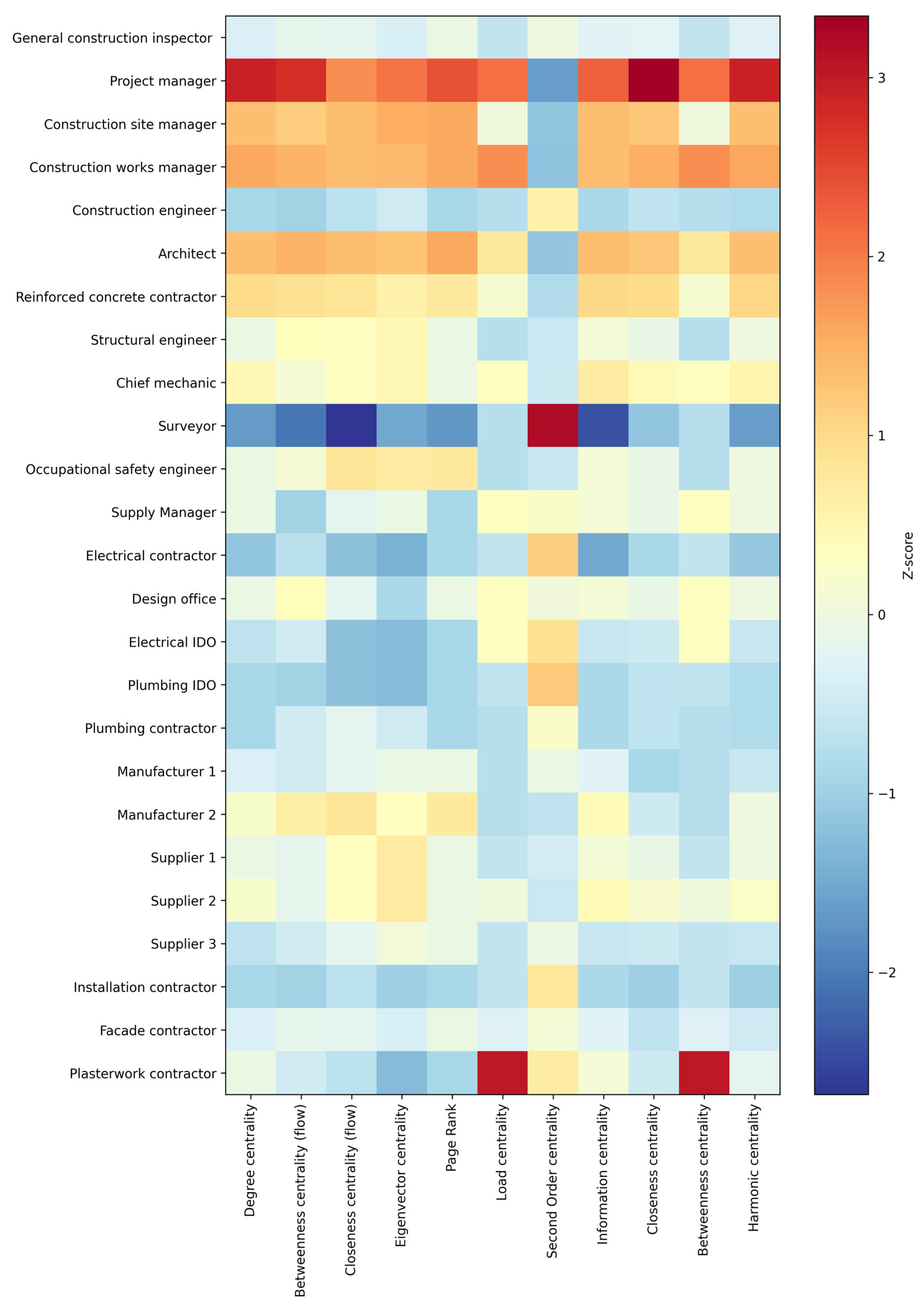

A comprehensive network analysis was conducted to evaluate the role and importance of individual participants in the supply chain of prefabricated construction (Table 3).

Table 3.

The determination of the principal centrality metrics for network nodes.

The use of an extended set of centrality measures makes it possible to assess not only the density of communication links but also the structural influence of different roles on information flow, material coordination, and synchronization between production and on-site assembly processes.

Degree centrality reflects the number of direct connections between participants. High values are typical for roles with intensive coordination responsibilities, such as the Project Manager, Construction Site Manager, and Construction Works Manager. Their extensive network integration indicates active involvement in planning, supervising, and coordinating production, transportation, and installation of prefabricated elements. Low degree values among suppliers and specialized subcontractors confirm their limited interaction scope and predominantly vertical communication structure.

Betweenness centrality measures the frequency with which a participant functions as an intermediate point along the shortest communication paths. High values for the Construction Site Manager, Construction Works Manager, and Supply Manager highlight their position as essential intermediaries linking design, production, logistics, and on-site operations.

Load centrality further quantifies the share of network flows passing through these nodes, confirming that the majority of logistical coordination, schedule alignment, and resource dispatching is concentrated within a small set of operational roles.

Closeness centrality indicates how quickly information originating from a given participant can reach all other nodes in the network. In prefabricated construction—where delays in communication have direct consequences for assembly windows, crane scheduling, and delivery synchronization—closeness becomes a critical metric. The highest values belong to the Project Manager, Structural Engineer, Architect, and Construction Site Manager, reflecting their ability to influence decision-making and adapt to changes with minimal communication delay. These metrics evaluate the influence of a participant while considering the importance of the nodes with which they are connected.

High eigenvector and PageRank values for the Architect, Project Manager, Structural Engineer, and Construction Site Manager indicate the existence of a strongly connected “decision-making core” whose actions shape the entire flow structure of the supply chain. This core serves as the foundation for design validation, change management, and technical coordination.

Second-order centrality assesses the stability of a node’s importance under changing network topologies. High values for the Supply Manager, Construction Site Manager, and selected technical specialists suggest that their structural relevance remains high even if subcontractors or communication pathways change.

This means that these participants are consistently critical for maintaining flow continuity and operational stability of the prefabricated supply chain.

In the context of supply chain management for prefabricated construction, the network demonstrates a distinctly formed coordination core that concentrates the majority of information flows and decision-making procedures, a configuration characteristic of project-oriented environments where technical and managerial control prevails over repetitive production processes. At the same time, such centralization increases the risks of system overload, the emergence of communication bottlenecks, and disruptions associated with critical roles, which may negatively affect the overall stability and operational efficiency of the supply chain.

In the context of prefabricated construction logistics, the overall efficiency of processes is largely determined by the quality of coordination among production, delivery, and on-site assembly, which in turn strongly depends on managerial functions and organizational discipline. Extended and overly complex information flows increase the likelihood of delay accumulation and can destabilize the entire supply rhythm. Under these conditions, delivery and installation schedules must be precisely synchronized with the project’s critical path to minimize time losses and prevent disruptions to the planned sequence of construction activities.

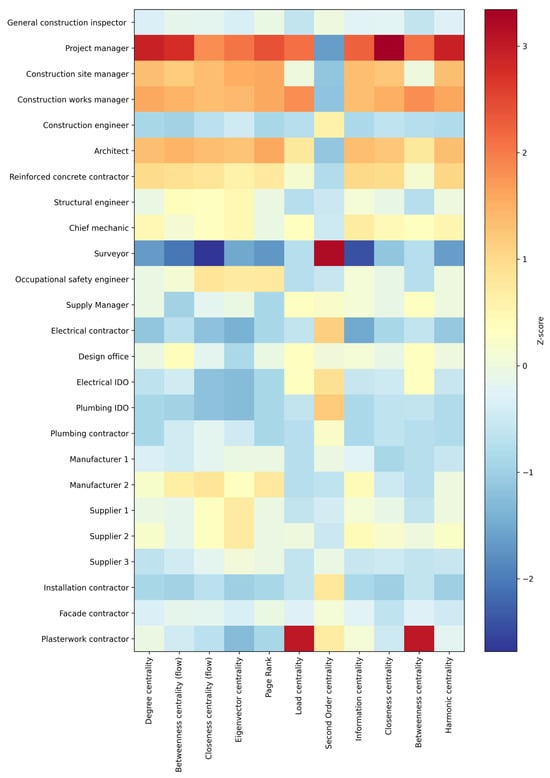

Figure 4 presents a normalized heatmap that illustrates the comparative distribution of all calculated centrality measures for each supply chain participant. The applied normalization eliminates scale differences between metrics, such as second-order centrality and betweenness, ensuring a valid basis for comparison.

Figure 4.

The comparative distribution heatmap of centrality measures for supply chain participants.

The visualization clearly reveals a structured differentiation within the network: the managerial core (Project Manager, Construction Site Manager, Construction Works Manager, Architect, Structural Engineer) exhibits the highest values across most indicators, represented by saturated warm colors; technical specialists and local subcontractors display a mixed centrality profile corresponding to their moderate level of involvement; whereas peripheral actors—suppliers and manufacturers—predominantly occupy the “cold” areas of the heatmap, indicating low values for the majority of metrics. This stratification confirms the hierarchical nature of the communication structure and the uneven distribution of influence among participants within the project network.

To illustrate the practical applicability of the proposed framework, a simple scenario-based what-if analysis was conducted. The scenario assumes targeted managerial intervention aimed at improving selected determinants of link stability (e.g., digital tools adoption and dispute resolution effectiveness) for a subset of critical links associated with highly central actors.

Conceptually, such interventions correspond to organizational actions frequently observed in practice, including the introduction of shared digital platforms, standardized communication protocols, or formalized conflict-resolution procedures. Under this scenario, the framework enables qualitative assessment of how incremental improvements in specific link attributes may propagate through the network structure and influence the overall coordination capacity of the supply chain. Simpler aggregation methods assume precise and commensurable inputs, which is rarely the case for relational attributes such as trust or collaboration. Fuzzy logic provides a structured mechanism to incorporate such ambiguity without forcing artificial precision.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The analysis of the supply chain network in prefabricated construction, a pronounced differentiation of roles and varying levels of influence among participants was identified, providing deeper insight into the mechanisms that shape the functioning and stability of logistics–production interactions.

From an academic perspective, the contribution of this study lies in shifting the analytical focus from actor-level or project-level performance to link-level relational stability within construction supply chains. Rather than explaining individual behaviors, the study introduces a structural perspective that reveals how heterogeneous relationship quality shapes network vulnerability and coordination capacity.

By integrating fuzzy logic with network analysis, the study provides a methodological contribution that enables systematic treatment of relational uncertainty and its propagation through the supply chain structure.

Unlike traditional static indicators, the integrated fuzzy logic and network analysis framework supports scenario-based reasoning by allowing practitioners to explore the potential effects of targeted interventions before their implementation. This capability is particularly relevant in prefabricated construction, where coordination failures often originate from a limited number of critical links or actors.

While the present study focuses on a single project snapshot, the framework is readily extendable to longitudinal data and multi-project comparisons, enabling future benchmarking against traditional construction supply chains or alternative assessment methods such as weighted averages or AHP. The added analytical complexity of fuzzy logic is justified by its ability to capture subjective and imprecise expert judgments that cannot be reliably represented using crisp scoring approaches.

This study adopts a single-case design, which imposes limitations on statistical generalizability. However, the objective of the research is not to produce universal parameter estimates, but to demonstrate and validate an integrated methodological framework for assessing supply chain stability in prefabricated construction. The case study serves as a proof of concept, illustrating how fuzzy logic and network analysis can be combined to support managerial decision-making in complex, highly coupled construction supply chains.

Future research may extend the proposed framework to multiple projects, different building typologies, or longitudinal data in order to assess cross-project variability and temporal dynamics of link stability.

The results indicate that several roles form critical “control nodes” that directly determine the efficiency of coordinating material, information, and operational flows. The observed dispersion and robustness of link stability values support the construct validity of the proposed indicator. The combination of high variability, realistic sparsity, and stable rank ordering under perturbation suggests that the indicator captures heterogeneous interaction strength rather than numerical artifacts of the fuzzy inference process.

In particular, the persistence of relative rankings under both binarization and random perturbation indicates that the identification of strong and weak links is structurally grounded and not sensitive to specific parameter settings or minor fluctuations in input assessments.

Actors were classified as core, semi-peripheral, or peripheral based on their consistent presence among the top-ranked positions across several centrality measures rather than on a single metric. This relative, multi-criteria classification avoids reliance on arbitrary thresholds and reflects the multifaceted nature of influence in construction supply chain networks. The Project Manager shows the highest degree, closeness, eigenvector, and PageRank centralities, acting as the central integrator between design, logistics, and assembly processes. The Construction Site Manager demonstrates high betweenness and closeness centrality, serving as a key mediator between production facilities, transportation logistics, and assembly crews. The Construction Works Manager forms essential “communication and operational corridors,” controlling the sequencing of tasks that directly affect the takt and synchronization of on-site assembly. The Supply Manager exhibits elevated load and information-based centralities, ensuring stability of the material flow, alignment of deliveries with assembly schedules, and availability of resources across all critical stages. The Architect/Structural Engineer holds high eigenvector centrality, as their engineering decisions determine logistical requirements, constructability criteria, and the feasibility of transport and assembly for prefabricated elements. The visual representation of the network, dominated by cool colors, indicates low values of most metrics for the remaining participants, reflecting a clear stratification of influence levels and confirming the hierarchical structure of the supply chain in the analyzed system.

In examining the peripheral participants within the supply chain network, it becomes evident that suppliers and manufacturers (Supplier 1–3, Manufacturer 1–2) exhibit low degree, eigenvector, and closeness centrality values, indicating limited interaction paths that typically connect only to the Supply Manager or the Construction Site Manager. Specialized subcontractors responsible for electrical works, plumbing, façade installation, and technical systems show similarly low betweenness centrality and minimal integration into core communication flows, performing predominantly task-specific activities based on instructions provided by central management. The surveyor, safety engineer, and IDO specialists occupy the lowest eigenvector and harmonic centrality positions, as their functions are localized, technical, or supervisory and do not influence major information or decision-making processes. This structural configuration introduces several critical risks for effective supply chain management: the concentration of communication and decision-making within a small cluster of central nodes increases vulnerability to bottlenecks; insufficient integration of suppliers and manufacturers raises the likelihood of scheduling inconsistencies and delivery delays; and the limited involvement of specialized subcontractors may lead to coordination issues and misalignments during the assembly phase. Overall, the observed hierarchical and stratified network configuration underscores both the strengths and fragilities of the prefabricated construction supply chain, suggesting that enhancing horizontal integration, improving multi-actor information exchange, and reducing dependency on a narrow group of central nodes are critical pathways for increasing stability and operational reliability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18031380/s1. Table S1: The base of rules; Table S2: The matrix of link stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. (Roman Trach) and I.C.; methodology, Y.T., M.D., I.C. and R.T. (Roman Trach); software, D.R., R.T. (Ruslan Tormosov) and G.R.; validation, D.R., M.D., R.T. (Ruslan Tormosov), G.R. and I.C.; formal analysis, Y.T. and M.D.; investigation, Y.T., M.D., D.R. and R.T. (Roman Trach); resources, G.R. and I.C.; data curation, Y.T., D.R., R.T. (Roman Trach) and R.T. (Ruslan Tormosov); writing—original draft preparation, Y.T.; writing—review and editing, R.T. (Roman Trach); visualization, D.R., R.T. (Ruslan Tormosov), G.R. and Y.T.; supervision, D.R., M.D., R.T. (Ruslan Tormosov), G.R. and I.C.; funding acquisition Y.T., R.T. (Roman Trach), R.T. (Ruslan Tormosov), G.R. and I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics committee or Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study, as it did not involve biomedical or behavioral research on human subjects. The research was based exclusively on an anonymous questionnaire survey of adult experts, conducted on a voluntary basis, without collecting personal, sensitive, or identifiable data. In accordance with applicable Ukrainian national regulations, such non-interventional and anonymized survey-based research does not require ethical approval. All procedures were carried out in line with ethical principles and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Francis, R.; Bekera, B. A Metric and Frameworks for Resilience Analysis of Engineered and Infrastructure Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014, 121, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarov, S.Y.; Holcomb, M.C. Understanding the Concept of Supply Chain Resilience. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2009, 20, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T.J.; Croxton, K.L.; Fiksel, J. Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience: Development and Implementation of an Assessment Tool. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 46–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukamuhabwa, B.R.; Stevenson, M.; Busby, J.; Zorzini, M. Supply Chain Resilience: Definition, Review and Theoretical Foundations for Further Study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5592–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.; Ravi, V. Supplier Selection in Resilient Supply Chains: A Grey Relational Analysis Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, S.G.; Govindan, K.; Carvalho, H.; Cruz-Machado, V. Ecosilient Index to Assess the Greenness and Resilience of the Upstream Automotive Supply Chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenstein, N.-O.; Feisel, E.; Hartmann, E.; Giunipero, L. Research on the Phenomenon of Supply Chain Resilience: A Systematic Review and Paths for Further Investigation. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 90–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkie, S.E.; Trucco, P.; Fernandez Campos, P. Effectiveness of Resilience Capabilities in Mitigating Disruptions: Leveraging on Supply Chain Structural Complexity. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, R.; Dani, S.; Burnard, K. Resilience: The Concept, a Literature Review and Future Directions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xiong, S.; Proverbs, D.; Zhong, Z. Evaluation of Humanitarian Supply Chain Resilience in Flood Disaster. Water 2021, 13, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, J.; Hosseini, S. Simulation-Based Assessment of Supply Chain Resilience with Consideration of Recovery Strategies in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 160, 107593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Dui, H.; Zhang, C. A Resilience Measure for Supply Chain Systems Considering the Interruption with the Cyber-Physical Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 199, 106869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Xiao, Z. Research on Spatio-Temporal Heterogeneity of Global Cross-Border e-Commerce Logistics Resilience under the Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic. J. Geogr. Res. 2021, 40, 3333–3348. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon-Jones, E.; Squire, B.; Autry, C.W.; Petersen, K.J. A Contingent Resource-Based Perspective of Supply Chain Resilience and Robustness. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colicchia, C.; Creazza, A.; Noè, C.; Strozzi, F. Information Sharing in Supply Chains: A Review of Risks and Opportunities Using the Systematic Literature Network Analysis (SLNA). Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Qi, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Assessing and Prioritising Delay Factors of Prefabricated Concrete Building Projects in China. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishodia, A.; Verma, P.; Dixit, V. Supplier Evaluation for Resilient Project Driven Supply Chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 129, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Green Construction of Coastal Prefabricated Buildings Based on Bim Technology. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2022, 31, 8590–8599. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, J.; Yuan, J. Research on Critical Factors Influencing the Resilience of Prefabricated Building Supply Chain Based on ISM. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2020, 37, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Yuan, C.; He, J.; Chen, Z. Influencing Factors Analysis of Supply Chain Resilience of Prefabricated Buildings Based on PF-DEMATEL-ISM. Buildings 2022, 12, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirifar, K.; Mojtahedi, M. The Impact of Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) Phases on Project Performance: A Case of Large-Scale Residential Construction Project. Buildings 2019, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broft, R.D.; Badi, S.; Pryke, S. Towards Supply Chain Maturity in Construction. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2016, 6, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, J.; Połoński, M.; Lendo-Siwicka, M.; Trach, R.; Wrzesiński, G. Method of Assessing the Risk of Implementing Railway Investments in Terms of the Cost of Their Implementation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, T.; Qin, Y.; Li, P.; Deng, Y. Influence Mechanism of Construction Supply Chain Information Collaboration Based on Structural Equation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgui, A.; Ivanov, D.; Sokolov, B. Ripple Effect in the Supply Chain: An Analysis and Recent Literature. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Gou, Q.; Yue, J.; Zhang, Y. Equilibrium Decisions for an Innovation Crowdsourcing Platform. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 125, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. The Construction Industry as a Loosely Coupled System: Implications for Productivity and Innovation. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2002, 20, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Wu, J.; Cao, Y. Study on the Impact of Trust and Contract Governance on Project Management Performance in the Whole Process Consulting Project—Based on the SEM and fsQCA Methods. Buildings 2023, 13, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikal, M.; Abd El Aleem, S.; Morsi, W.M. Characteristics of Blended Cements Containing Nano-Silica. HBRC J. 2013, 9, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Chan, A.P.C.; Yeung, J.F.Y. Developing a Fuzzy Multicriteria Decision-Making Model for Selecting Design-Build Operational Variations. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2011, 137, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Simulation Analysis of Supply Chain Resilience of Prefabricated Building Projects Based on System Dynamics. Buildings 2023, 13, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar Balbino Barbosa Filho, A.; Mauro Da Silva Neiro, S. Fine-Tuned Robust Optimization: Attaining Robustness and Targeting Ideality. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 165, 107890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.; Kim, K.P.; Tam, V.W.; Rahnamayiezekavat, P. Exploring the Status, Benefits, Barriers and Opportunities of Using BIM for Advancing Prefabrication Practice. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 20, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhwlani, M.; Ayesh, A. Access Network Selection Using Combined Fuzzy Control and MCDM in Heterogeneous Networks. In 2007 International Conference on Computer Engineering & Systems, Cairo, Egypt, 27–29 November 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Yue, P.; Ye, F.; Tapete, D.; Liang, Z. Bidirectionally Greedy Framework for Unsupervised 3D Building Extraction from Airborne-Based 3D Meshes. Autom. Constr. 2023, 152, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryke, S.; Badi, S.; Almadhoob, H.; Soundararaj, B.; Addyman, S. Self-Organizing Networks in Complex Infrastructure Projects. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 49, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenijam, A. Advancing Regression Based Analytics for Steel Fabrication Productivity Modeling. Doctoral Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trach, R.; Khomenko, O.; Trach, Y.; Kulikov, O.; Druzhynin, M.; Kishchak, N.; Ryzhakova, G.; Petrenko, H.; Prykhodko, D.; Obodianska, O. Application of Fuzzy Logic and SNA Tools to Assessment of Communication Quality between Construction Project Participants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trach, R.; Pawluk, K.; Lendo-Siwicka, M. The Assessment of the Effect of BIM and IPD on Construction Projects in Ukraine. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 22, 1844–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, N.; Elliott, F. Conflict Avoidance and Dispute Resolution in Construction; RICS: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawan, J.; Marzilli, C.; Aungsuroch, Y. Establishing Appropriate Sample Size for Developing and Validating a Questionnaire in Nursing Research. Belitung Nurs. J. 2021, 7, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. Predicting Out-of-Stock Risk Under Delivery Schedules Using Neural Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaur, J.M.R.; Ruz, G.A.; Goycoolea, M. Predicting Out-of-Stock Using Machine Learning: An Application in a Retail Packaged Foods Manufacturing Company. Electronics 2021, 10, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goguen, J.A. L. A. Zadeh. Fuzzy Sets. Information and Control, Vol. 8 (1965), pp. 338–353.-L. A. Zadeh. Similarity Relations and Fuzzy Orderings. Information Sciences, Vol. 3 (1971), pp. 177–200. J. Symb. Log. 1973, 38, 656–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizunov, P.; Biloshchytskyi, A.; Kuchansky, A.; Andrashko, Y.; Biloshchytska, S. Improvement of the Method for Scientific Publications Clustering Based on N-Gram Analysis and Fuzzy Method for Selecting Research Partners. East. Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2019, 4, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniani, D.; Lioi, D.S.; Mancini, I.M.; Masi, S. Hierarchical Classification of Groundwater Pollution Risk of Contaminated Sites Using Fuzzy Logic: A Case Study in the Basilicata Region (Italy). Water 2015, 7, 2013–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. A Set of Measures of Centrality Based on Betweenness. Sociometry 1977, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trach, R.; Lendo-Siwicka, M.; Pawluk, K.; Bilous, N. Assessment of the Effect of Integration Realisation in Construction Projects. Teh. Glas. 2019, 13, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trach, R.; Lendo-Siwicka, M. Centrality of a Communication Network of Construction Project Participants and Implications for Improved Project Communication. Civ. Eng. Environ. Syst. 2021, 38, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, P. Power and Centrality: A Family of Measures. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine. Comput. Netw. ISDN Syst. 1998, 30, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E. A Measure of Betweenness Centrality Based on Random Walks. Soc. Netw. 2005, 27, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, U. Network Analysis: Methodological Foundations; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3418. [Google Scholar]

- Kermarrec, A.-M.; Le Merrer, E.; Sericola, B.; Trédan, G. Second Order Centrality: Distributed Assessment of Nodes Criticity in Complex Networks. Comput. Commun. 2011, 34, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, M.; Latora, V. Harmony in the Small-World. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2000, 285, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.