Abstract

Digital–intelligent technologies and their extensive application across real-world scenarios are profoundly reshaping traditional industries while fostering emerging and future industries, becoming a key engine for industrial intelligence and the development of new quality productive forces. Advancing new quality productive forces in coal enterprises is a core pathway to overcome bottlenecks such as high safety risks and stringent environmental constraints in the traditional coal sector and to achieve high-quality industrial development; digital–intelligent transformation provides critical support for this process. Using panel data from 30 Chinese A-share listed coal companies from 2012 to 2024, this study empirically examines the impact of digital–intelligent transformation on the development of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises, and explores the mediating role of resource allocation efficiency and the moderating role of local governments’ economic performance assessment pressure. The results show that digital–intelligent transformation significantly promotes the development of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises. Resource allocation efficiency plays a mediating role in this relationship, accounting for 14.89% of the total effect. Moreover, local economic performance assessment pressure negatively moderates the effect of digital–intelligent transformation on the development of new quality productive forces, and this negative moderating effect persists along the mediating pathway via resource allocation efficiency. This study aims to uncover the internal mechanism through which digital–intelligent transformation promotes new quality productive forces in coal enterprises, providing a new theoretical basis and research perspective for coal enterprises to cultivate new quality productive forces.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of digital and intelligent technologies, production methods and organizational models in traditional industries are undergoing profound changes [1]. Digitalization, intelligentization, and deep integration have gradually become critical technological foundations for improving industrial productivity and achieving high-quality development by restructuring production processes, optimizing resource allocation (RA), and enhancing decision-making efficiency [2]. Existing studies suggest that the diffusion of digital–intelligent technologies can, under certain conditions, improve firm productivity and organizational efficiency, yet the magnitude and channels of these effects vary substantially across industries—particularly in resource-based and traditional industrial sectors [3]. As a result, the underlying mechanisms and practical effectiveness remain insufficiently understood.

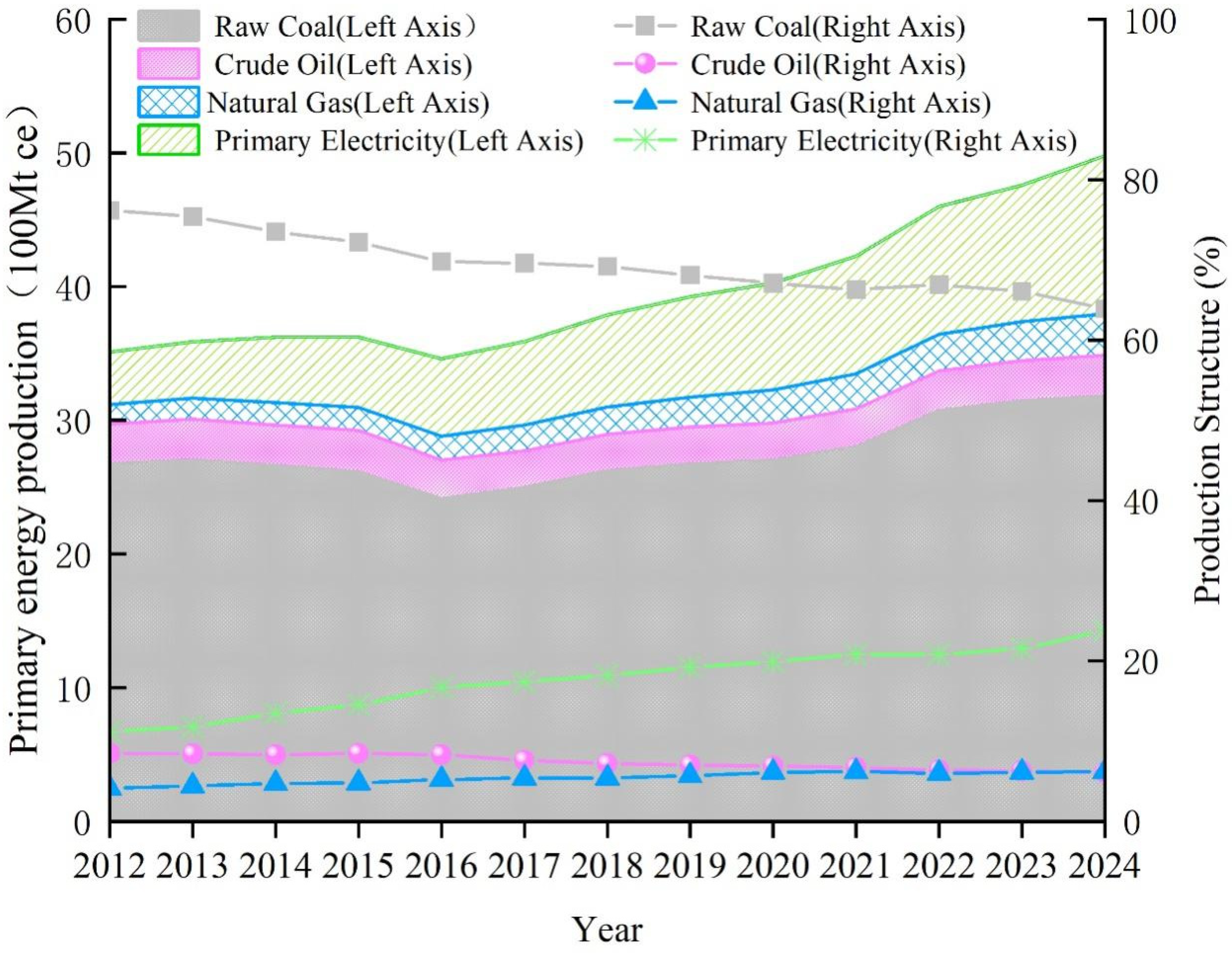

From an industry-wide perspective, coal has long occupied a central position in China’s energy system. As illustrated in Figure 1, during 2012–2024, coal production consistently accounted for more than 60% of primary energy production. Although the share has shown a downward trend, overall raw coal output continued to rise, and coal still serves as a strategic “ballast” for energy security. However, relative to its scale and strategic importance, the coal industry exhibits a pronounced structural lag in cultivating new quality productive forces. On the one hand, the sector’s digital development remains behind the energy-system average. In 2021, the digital economy in the coal industry accounted for only 15.2% of total industrial output, far below the national share of the digital economy in GDP (39.9%) over the same period. Moreover, the coal industry’s digital talent base is insufficient to meet transformation needs: personnel dedicated to informatization and digitalization total roughly 20,000, accounting for only about 1% of the workforce in large coal enterprises, which constrains the deep application of digital technologies in production and management. On the other hand, the coal industry’s capacity to absorb and translate digital technologies remains limited. Long et al. report that digital policies improve energy efficiency in coal enterprises by only about 10.5%, which is notably lower than in other energy sub-sectors such as oil and electricity [4]. In addition, although the fatality rate per million tons of coal mined fell sharply from 5.71 in 2000 to 0.059 in 2020, this improvement has largely relied on stringent regulation and high-intensity safety investment rather than a transformation path centered on endogenous technological innovation and the restructuring of production organization [5]. Meanwhile, intelligentization in the coal sector requires substantial capital outlays: in smart-mine development plans, the benchmark investment for a ten-million-ton-scale mine is RMB 250 million, and the standard investment for each coal preparation plant is RMB 20 million, further raising the entry barrier to system-wide digital–intelligent transformation (DIT) in the coal industry.

Figure 1.

Primary Energy Production in China.

Coal enterprises, as the key micro-level carriers and foundations of the coal industry [6], provide an essential setting for examining whether digital–intelligent transformation can effectively enhance new quality productive forces (NQP) at the firm level. Existing studies have explored, in a general sense, the impacts of digital–intelligent transformation on production efficiency, innovation capability, and cost efficiency [7,8,9,10]. However, the evidence remains mixed, and empirical findings for resource-based industries such as coal are relatively limited [11]. Some studies argue that digital–intelligent transformation does not automatically translate into productivity gains; instead, its effectiveness is highly contingent on firms’ resource allocation capability, organizational structure, and the external institutional environment [12,13].

Against this background, using panel data on 30 Chinese A—share listed coal companies from 2012 to 2024, this study systematically measures the extent of digital–intelligent transformation and the development level of NQP, and investigates the effects and internal mechanisms through which digital–intelligent transformation empowers NQP in coal enterprises. Specifically, we first construct a measurement system for coal enterprises’ digital–intelligent transformation by integrating text analysis with quantitative indicators, and evaluate firms’ NQP using a projection pursuit model. Second, we test the direct enabling effect of digital–intelligent transformation using a baseline regression framework. Third, we incorporate mediation and moderation analyses to uncover the roles of resource allocation efficiency and local economic performance assessment pressure in the linkage between digital–intelligent transformation and NQP improvement.

This study makes three marginal contributions. First, it extends the analytical framework for understanding how digital–intelligent transformation empowers NQP in coal enterprises. By focusing on coal firms, we introduce NQP into the context of resource-based industries and articulate the internal logic through which digital–intelligent transformation promotes NQP by optimizing resource allocation. By highlighting resource allocation efficiency as a key transmission channel, the study enriches the theoretical understanding of the relationships among digital–intelligent transformation, resource allocation, and firm-level NQP and offers a new perspective on the role of digital–intelligent technologies in the upgrading of resource-based industries. Second, the study empirically identifies and verifies the mechanism through which digital–intelligent transformation enhances NQP in coal enterprises. Given practical constraints frequently faced by coal firms—such as complex strategic choices and inefficient resource allocation during transformation—this study uses micro-level firm data to systematically test the mediating effect of improved resource allocation efficiency. In doing so, it helps address the shortage of empirical evidence on how digital–intelligent transformation in resource-based enterprises translates into NQP improvement, thereby deepening academic understanding of the actual effectiveness of transformation in the coal sector. Third, the study provides targeted managerial and policy implications for coal enterprises’ digital–intelligent transformation and the cultivation of NQP. By revealing the pivotal mediating role of resource allocation and the moderating effect of local economic performance assessment pressure, we demonstrate that enabling NQP through digital–intelligent transformation is not merely a matter of technology investment, but rather requires coordinated advancement of resource allocation mechanisms and the institutional environment. These findings provide robust empirical support for coal enterprises seeking to optimize transformation pathways and for policymakers aiming to design differentiated and precision-oriented support policies.

2. Literature Review

The state of “new quality productive forces” was proposed by the Chinese government in September 2023 and is defined as an advanced form of productivity driven by scientific and technological innovation and aligned with the principles of high-quality development [14]. Rather than a simple aggregation of traditional production factors, new quality productive forces reshape the production structure through fundamental changes in technological paradigms and organizational forms [15]. Their essence lies in the efficient coordination among new types of workers, new means of labor, and new objects of labor, thereby enabling a systemic leap in total factor productivity [16]. At the firm level, new quality productive forces emphasize innovation-led development and the deep integration of digital and intelligent technologies with the real economy, driving the reconstruction of production modes, organizational structures, and value-creation models [14]. For coal enterprises, new quality productive forces highlight digitalization and intelligent coal mining as key pathways, aiming to address structural bottlenecks such as high safety risks and stringent environmental constraints, and to form a new productivity paradigm oriented toward safety, intelligence, efficiency, and green development. The development of new quality productive forces in the coal sector helps break through the dual constraints of resources and safety, injecting endogenous momentum into breakthroughs in key core technologies and the high-end upgrading of traditional industries, while also providing micro-level support for Chinese modernization [17].

Existing approaches to the assessment and quantification of new quality productive forces generally fall into two categories: parsimonious measurement schemes based on a single proxy indicator and comprehensive evaluation frameworks built on multidimensional indicator systems. The former is typically represented by total factor productivity (TFP) and green total factor productivity (GTFP), which emphasize capturing the overall performance of new quality productive forces through efficiency improvements and technological progress. The latter starts from the Marxist triad of productive forces, as well as the salient features and intrinsic attributes of new quality productive forces, and constructs multi-layered and multi-dimensional composite evaluation systems. Parametric estimation methods based on production functions, provide intuitive tools for total factor productivity (TFP) measurement. However, they are prone to estimation biases when the prespecified form of production technology deviates from the actual operational conditions. Among nonparametric approaches, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and the Malmquist index construct the production frontier without imposing any prior assumptions on the functional form of the production function. These methods can decompose TFP changes into two components, namely technical efficiency change and technological progress, and have been widely applied to heterogeneous contexts including the cultural industry, artificial intelligence enterprises, and toll road operators. Semiparametric estimation methods, such as the Olley-Pakes (OP) and Levinsohn-Petrin (LP) models, introduce investment or intermediate inputs as proxy variables, which effectively mitigate the endogeneity issue. These approaches have been employed for TFP calculation in the manufacturing sector, food industry, and tobacco trading enterprises. In particular, the improved dynamic OP model enables the characterization of the “super-growth effect” among newly established firms.

Single-indicator measures offer advantages in operability and comparability, providing a useful basis for dynamic analysis and intertemporal comparisons. By contrast, multidimensional index systems are more informative for structural identification and mechanism analysis, and better reflect the complexity and contemporary characteristics embedded in the concept of new quality productive forces. Nevertheless, the existing literature still faces several limitations. First, the mapping between the concept and its measurable indicators remains insufficiently clarified. Interpretations of what constitutes “new quality” are not fully consistent across studies, resulting in heterogeneous measurement practices and fragmented empirical operationalization [18]. Second, the dynamic evolution of productivity upgrading is not adequately captured: high-frequency data and nonlinear development patterns have not been fully incorporated. Third, industry- and context-specific measurement remains relatively weak. Although measurement tools tailored to specific sectors such as coal, agriculture, and finance have been explored [19], systematic and standardized schemes are still lacking. Accordingly, grounded in the connotation of the three elements of productive forces and incorporating the characteristics of digital–intelligent development and resource–environment constraints in coal enterprises, this study develops an industry-consistent measurement system for new quality productive forces.

At present, digital–intelligent transformation has become one of the most central topics and emerging trends in digital economy research. With the rapid iteration and accelerated development of new technology clusters—such as big data, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and digital twins—the connotation of digital–intelligent transformation has been continuously enriched and diversified [18]. Enterprises can use digital–intelligent technologies to reshape organizational structures and strengthen innovation decision-making; by integrating powerful digital intelligence with forward-looking digital–intelligent strategies, firms achieve synergistic integration with traditional production factors and further develop a trend toward digital–intelligent convergence [19]. Guo et al. argue that the core of firms’ digital–intelligent transformation lies in continuously improving technology, organization, and management, thereby fostering reform and innovation, value coordination, resource allocation capabilities, and competitive advantage, which in turn expands business scenarios and functional boundaries [20]. Although the academic community has not yet reached full consensus on the concept of digital–intelligent transformation, most scholars agree that it includes and evolves from digital transformation and can be regarded as an upgraded stage or higher-order form of digital transformation [21]. Building on prior research on digital transformation, this study conceptualizes firms’ digital–intelligent transformation as a systematic, comprehensive, multi-dimensional, and higher-level shift and leap—from business models to operational paradigms, and from products and services as well as production and operations to organizational and managerial systems [22]. This transformation is enabled by digital–intelligent technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and cloud computing; it is centered on “data + algorithms + computing power”; it targets the application of these capabilities in firm-specific business scenarios; and it ultimately aims to achieve an overall enhancement of firm value.

For the measurement of digital–intelligent transformation, most existing studies rely on either a single quantitative proxy or a text-analysis approach to gauge firms’ digital–intelligent transformation levels. Existing studies largely rely on either quantitative proxies or text analysis. Quantitative approaches extract information from financial statements or third-party databases to measure financial inputs (e.g., the share of software and hardware investment [23]) or quantified outputs (e.g., the number of digital–intelligent-related patents [24]), providing an objective assessment of transformation efforts. By contrast, text analysis constructs keyword sets based on the underlying technological architecture of digital–intelligent transformation, integrates prior literature and policy reports, and applies text-mining methods to extract keyword frequencies from listed firms’ annual reports to measure the extent of transformation [25]. Under such approaches, annual-report disclosures may be strategically “packaged” to cater to market expectations, leading to inflated keyword frequencies. Moreover, focusing solely on managerial strategic attention cannot adequately capture firms’ actual inputs to digital–intelligent transformation or their realized output performance. Digital–intelligent transformation is a complex systems project. For coal enterprises in particular, it is a dynamic process in which cognition guides investment, investment determines output, and output feeds back into cognition. These three dimensions correspond to the full transformation cycle and, in essence, follow a “strategy–resources–outcomes” logic. This end-to-end logic is also consistent with the intrinsic nature of digital–intelligent transformation. Accordingly, this study adopts a composite indicator system and measures coal enterprises’ digital–intelligent transformation from three dimensions—digital–intelligent cognition, digital–intelligent investment, and digital–intelligent output—to capture transformation dynamics systematically across the entire process and to comprehensively reflect its multidimensional content.

Regarding the effects of digital–intelligent transformation, existing research has primarily examined its industrial applications as well as the associated social impacts and economic benefits. From the perspective of social outcomes, the adoption of digital and intelligent technologies has generated positive effects on public governance, including grassroots governance and fiscal performance [26]. It has also created innovative pathways for public services and education. At the industrial level, traditional sectors have achieved output growth and efficiency gains through integration with AI and other digital–intelligent technologies. In manufacturing, for example, digital–intelligent transformation—enabled by massive data resources, advanced algorithms, and intelligent technologies—has improved quality and efficiency, alleviated resource constraints, and promoted innovative development of service-oriented business models. At the firm level, digital–intelligent transformation can enhance organizational resilience by strengthening green technological innovation. Specific applications such as digital–intelligent forecasting and intelligent management systems can support the internationalization of “specialized, refined, distinctive, and innovative” firms. For state-owned enterprises, both foundational and advanced forms of digital–intelligent empowerment have been found to promote high-quality development. However, some studies suggest negative or nonlinear effects. For instance, Zhang and Du argue that digital–intelligent transformation increases the quantity of innovation but reduces its quality [26]. Pang and Liu find that digital–intelligent transformation promotes innovation, yet when digital–intelligent transformation is at a low level, learning effects dominate and stimulate innovation, whereas beyond a certain threshold, competitive effects become dominant and inhibit innovation [27]. In addition, city-level evidence suggests that digital–intelligent development may induce a rebound effect in electricity consumption, although this rebound effect tends to weaken over time.

This study focuses on the effects and mechanisms of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces. The rapid development of digital–intelligent technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data has fostered a new economic form and provided a technological foundation for firms to cultivate new quality productive forces [28]. Firms that implement digital–intelligent transformation can leverage breakthrough applications—such as data-driven operations, intelligent cognition, and dynamic intelligent decision-making—to reduce reliance on traditional growth models and production modes, thereby enabling a leap in new quality productive forces [29]. Specifically, three core channels are emphasized. First, technological innovation and intelligent upgrading—through the deep application of AI, big data, and intelligent manufacturing—optimize production processes and decision-making patterns, generating quantifiable efficiency improvements: intelligent manufacturing is associated with a 15–20% increase in total factor productivity, data-driven decision-making can further reduce operating costs, and open innovation can improve R&D efficiency and the commercialization of research outputs. Second, organizational change and improved resource allocation function as key mediating mechanisms: digital tools such as ERP systems facilitate managerial flattening and shorten decision chains; smart supply-chain pilots significantly reduce coordination costs and enhance firms’ new quality productive forces; and digital finance and online training can relax financing constraints and improve the matching of human capital, respectively, thereby enabling coordinated optimization of capital, labor, and technology. Third, market-oriented factor allocation and data empowerment—through data trading platforms and mechanisms for pricing and circulating data as a factor—reduce information and transaction costs, promote deeper digital–intelligent transformation, and translate it into measurable efficiency gains.

Overall, the literature on digital–intelligent transformation and firm-level new quality productive forces remains limited, particularly regarding its effects on coal enterprises. Moreover, prior research on evaluating digital–intelligent transformation has largely relied on text-based descriptive measures, with relatively few studies combining text analysis and quantitative proxies to assess transformation in the coal sector. Existing studies mainly examine the relationship between digitalization and new quality productive forces, while empirical evidence remains scarce on how resource allocation and local economic performance assessment pressure shape the linkage between digital–intelligent transformation and the development of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises. Accordingly, this study focuses on how digital–intelligent transformation promotes the development of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises through the optimization of resource allocation.

3. Mechanism Analysis and Research Hypotheses

- (1)

- Direct effect of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces in coal enterprises

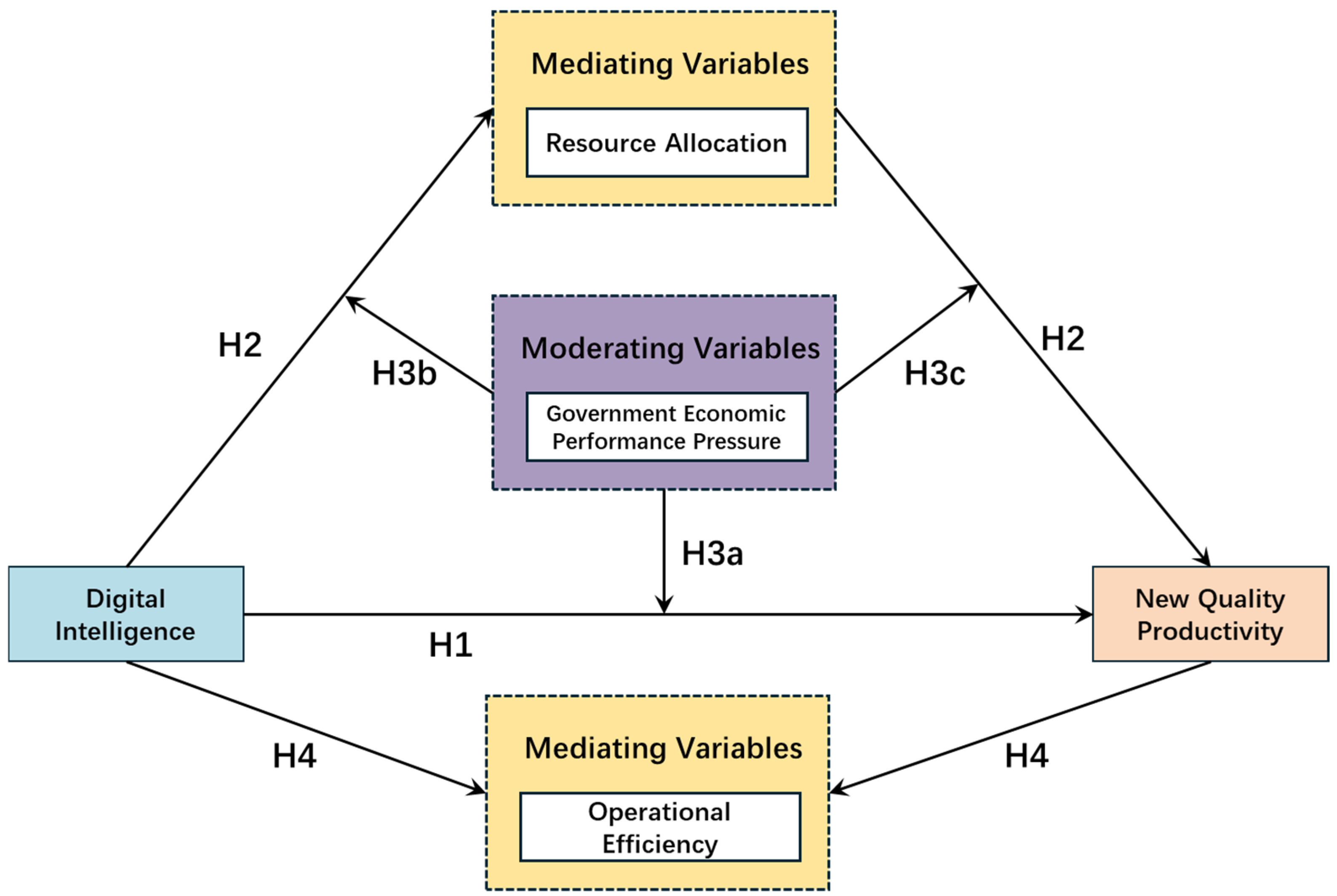

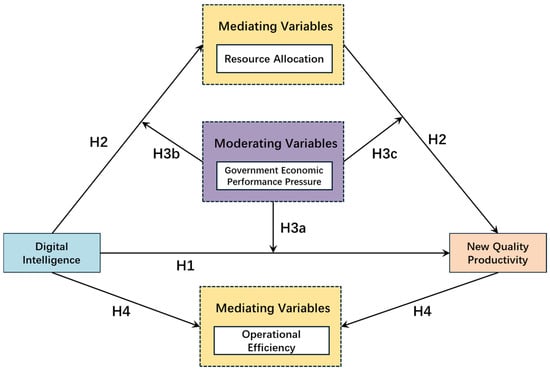

New quality productive forces in coal enterprises are characterized by “intelligence, efficiency, greenness, and safety.” Their development requires overcoming technological bottlenecks, efficiency constraints, and ecological pressures embedded in traditional production modes. Leveraging rapid technological iteration and data-driven advantages, digital–intelligent transformation can directly restructure coal enterprises’ production and operational systems [30], thereby providing critical support for the development of new quality productive forces (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The theoretical framework of this study.

From the perspective of technological upgrading, deep integration of 5G communications, artificial intelligence, and digital twins with coal production scenarios can improve mining precision and efficiency while reducing safety risks and resource losses. Intelligent monitoring and fine-grained control systems can further optimize energy-saving and emission-reduction strategies, lowering pollutant and carbon intensities and enabling cleaner production [31]. From the perspective of efficiency enhancement, integrated information management platforms built through digital–intelligent transformation can break down intra-firm information silos and enable real-time data sharing and coordinated dispatch across the full value chain of mining, processing, and transportation [30]. By using data analytics to identify bottlenecks and optimize processes, firms can reduce inter-stage waste and shift production management toward a data-driven paradigm, thereby improving resource utilization and operational performance [32,33]. From the perspective of factor upgrading, digital–intelligent transformation incentivizes enterprises to strengthen digital skills training and attract high-level talent with digital and R&D backgrounds, thereby optimizing the composition of new quality labor [34]. It also activates the value of data as a production factor by converting multi-dimensional data (production, management, environment) into decision inputs and enabling synergy with traditional factors such as technology and capital, thus upgrading the quality of production factors [35].

Taken together, digital–intelligent transformation can directly relax technological, efficiency, and factor constraints on the development of new quality productive forces and promote “intelligent, efficient, green, and safe” development through multiple channels. Accordingly, we propose:

H1:

Digital–intelligent transformation has a significantly positive enabling effect on the development of firms’ new quality productive forces.

- (2)

- Mediating effect of resource allocation efficiency

The cultivation of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises depends on the effective integration and precise allocation of production factors such as capital, technology, talent, and data. However, the traditional coal industry is often subject to information asymmetry and experience-based decision-making, leading to pervasive resource misallocation. On the one hand, the asset-heavy nature of coal enterprises slows capital turnover, resulting in insufficient long-term investment in intelligent equipment R&D and green technological innovation, while funds tend to flow toward traditional capacity with quicker returns. On the other hand, shortages of specialized technical and digital talent, mismatches between labor structures and intelligentization needs, and limited integration of data with physical production processes reduce factor-use efficiency and become key constraints on the development of new quality productive forces.

Digital–intelligent transformation, by breaking information barriers and reshaping decision logic, can reconstruct resource allocation mechanisms and improve allocation efficiency, thereby forming a transmission channel of “technological enabling–factor optimization–productivity upgrading” [36]. Specifically, industrial internet platforms can integrate data across the industrial chain for predictive analytics, support rational capital allocation, and dynamically adjust the coordination between labor and intelligent equipment, improving the matching between factor supply and demand [37] and enhancing capital allocation efficiency [38]. Moreover, digital–intelligent management systems can mitigate departmental information isolation, strengthen flexible resource dispatch, and reduce equipment idleness and technological waste, thereby directing capital, technology, and talent toward core domains of new quality productive forces [39].

Therefore, digital–intelligent transformation can significantly improve resource allocation efficiency, which in turn provides factor and a clear pathway for developing new quality productive forces, constituting a mediating mechanism of “digital–intelligent transformation–resource allocation efficiency-new quality productive forces.” Accordingly, we propose:

H2:

Digital–intelligent transformation promotes the development of new quality productive forces by improving resource allocation efficiency.

- (3)

- Moderating effect of local economic performance assessment pressure

Local economic performance assessment pressure, typically centered on GDP growth targets, substantially shapes local government behavior and firms’ resource allocation decisions [40], and thus systematically moderates the transmission mechanism of “digital–intelligent transformation–resource allocation efficiency–new quality productive forces.” As pillar firms in many regions, coal enterprises are particularly susceptible to such pressure. When local governments face overly stringent GDP growth targets, they tend to prioritize short-term output expansion to rapidly boost regional economic performance. Digital–intelligent transformation, however, is characterized by large upfront investment, long payback periods, and risks associated with technological iteration; its enabling effects on new quality productive forces generally materialize through sustained capability accumulation and organizational restructuring, and are unlikely to translate into immediate GDP gains [39]. Consequently, local governments may, through policy guidance and resource tilting, incentivize coal enterprises to allocate key resources to short-term capacity expansion rather than long-horizon transformation activities such as intelligent equipment R&D and digital platform development. This may prevent the technological enabling potential of digital–intelligent transformation from being fully realized and weaken its positive effect on new quality productive forces.

The improvement of resource allocation efficiency through digital–intelligent transformation typically requires reallocating resources toward long-term value-creating domains and achieving precise factor matching via data-driven management [40]. Yet local economic performance assessment pressure may distort firms’ allocation choices. First, high growth targets may force firms to prioritize stable output from traditional capacity, shifting resources toward short-term, high-output, low-risk businesses and crowding out investment in intelligent mining R&D and digital talent development that is essential for long-term allocation efficiency [41]. Second, administrative intervention by local governments to meet assessment targets may disrupt the market-oriented allocation mechanism enabled by digital–intelligent transformation, aggravating factor misallocation (e.g., equipment idleness and technological waste) and significantly constraining the efficiency-enhancing role of digital–intelligent transformation.

Moreover, the productivity-enhancing role of resource allocation efficiency depends on the directionality of allocation—resources must flow toward core domains such as intelligent transformation and green, low-carbon development. Under strong assessment pressure, efficiency improvements may be concentrated on the refined management of traditional capacity rather than factor optimization aligned with digital–intelligent transformation, thereby providing limited support for new quality productive forces [36]. In addition, assessment pressure reinforces short-termism: even when allocation efficiency improves, firms may continue to invest the released resources in traditional businesses to expand short-term output rather than cultivate new quality productive forces. This weakens the positive incentive effect along the mediated pathway and may generate negative moderation on the “resource allocation efficiency-new quality productive forces” link by reinforcing path dependence on traditional production modes and impeding transformation.

Accordingly, we propose:

H3a:

Local economic performance assessment pressure weakens the positive effect of digital–intelligent transformation on the development of new quality productive forces.

H3b:

Local economic performance assessment pressure weakens the positive effect of digital–intelligent transformation on firms’ resource allocation efficiency.

H3c:

As local economic performance assessment pressure increases, improvements in resource allocation efficiency weaken the positive incentive of the digital–intelligent transmission mechanism and exert a negative moderating effect along the “resource allocation efficiency–new quality productive forces” pathway.

- (4)

- Mediating Effect of Firm Operating Efficiency in the Digital–Intelligent Transformation–NQP Linkage

New quality productive forces (NQP) emphasize high-quality productive capacity driven by technological progress, factor synergy, and improvements in organizational efficiency. Their formation depends not only on optimizing the structure of factor inputs but also, crucially, on systematic enhancements in firms’ internal operating efficiency. Firm operating (or managerial) efficiency reflects a firm’s comprehensive capability to transform inputs into outputs under given resource constraints through organizational coordination, process management, and information processing, and thus constitutes a key channel linking technological change to production performance.

Digital–intelligent transformation provides critical technological and organizational foundations for coal enterprises to improve operating efficiency. On the one hand, by introducing big data analytics, artificial intelligence, and intelligent dispatching systems, digital–intelligent transformation shifts core functions—such as production planning, equipment operation, inventory management, and logistics scheduling—from experience-based decisions to data-driven decisions, thereby reducing operational frictions caused by information asymmetry and decision delays. With real-time monitoring and predictive analytics, firms can coordinate mining, coal preparation, and transportation processes more precisely, reducing duplicated work, waiting time, and non-value-added procedures, and thus significantly improving operating efficiency. On the other hand, digital–intelligent transformation reshapes organizational operating modes. Platform-based management supported by information systems helps break down departmental silos and hierarchical fragmentation, strengthening cross-departmental collaboration and process integration. By centrally integrating and sharing data on production, equipment, safety, and operations, digital–intelligent systems enhance information transparency and organizational responsiveness, enabling more efficient resource dispatching and operational management in complex production environments. Such improvements in operating efficiency—centered on process optimization and organizational coordination—provide essential organizational support for the development of NQP.

Moreover, higher operating efficiency facilitates the conversion of the technological advantages of digital–intelligent transformation into stable and sustainable productivity gains. First, improved operating efficiency reduces the comprehensive cost per unit of output and increases the utilization efficiency of capital and labor, thereby freeing internal resources for technological innovation and green transition. Second, enhanced operating efficiency strengthens firms’ capabilities to absorb and internalize new technologies and new operating models, making it more likely that digital–intelligent investments translate into “intelligent, efficient, green, and safe” production practices, and thus supporting the continuous accumulation and upgrading of NQP. Based on the above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4:

Digital–intelligent transformation promotes the development of new quality productive forces by improving firm operating efficiency.

4. Methods and Data

4.1. Baseline Regression Model

- (1)

- Baseline Specification

To examine the direct effect of digital–intelligent transformation on the development of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises, we construct the following baseline regression model (1):

In this model, NQP is the dependent variable and represents the level of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises. i indicates the firms, while t indicates years. DIT denotes the key explanatory variable, measuring the level of digital–intelligent transformation. X is a vector of control variables. μᵢ and λₜ represent firm fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively, and εᵢₜ is the error term.

- (2)

- Mediation Model

To test Hypothesis H2—namely, that digital–intelligent transformation promotes the development of new quality productive forces by improving resource allocation efficiency—this study adopts the three-step approach to examine the mediating effect. Specifically, the mediation test consists of Model (2), Model (3), and the main-effect Model (1) as the three regression steps. The mediation regressions are specified as Models (2) and (3) as follows:

In these equations, M is the mediating variable, representing resource allocation efficiency. and firm operating efficiency.

- (3)

- Moderation Model with an Interaction Term

To test Hypothesis H3a—that under local economic performance assessment pressure, the positive effect of digital–intelligent transformation on the development of new quality productive forces will be weakened—we extend Model (1) by introducing local economic performance assessment pressure and the interaction term between digital–intelligent transformation and this pressure. This yields Model (4), which is used to further examine the moderating role of city-level economic performance assessment pressure in the relationship between digital–intelligent transformation and new quality productive forces in coal enterprises.

In this model, EP denotes the moderating variable, capturing the local government’s economic growth target. DIT × EP is the interaction term between digital–intelligent transformation and local economic performance assessment pressure.

To test the moderating effect of local economic performance assessment pressure and to examine how it affects the enabling mechanism of digital–intelligent transformation on firms’ new quality productive forces by shaping the efficiency of the transmission channel via resource allocation, this study follows Heubeck [42]. Specifically, we employ a moderation framework to investigate the moderating role of local economic performance assessment pressure in the process through which resource allocation efficiency contributes to new quality productive forces. By introducing interaction terms between local economic performance assessment pressure and both digital–intelligent transformation and resource allocation efficiency [43], we construct a moderated mediation model, consisting of Models (5) and (6).

In Model (6), RA × EP denotes the interaction term between resource allocation efficiency and local economic performance assessment pressure.

4.2. Variable Definitions

4.2.1. Dependent Variable: Firms’ New Quality Productive Forces

This study develops a multidimensional framework to measure firms’ new quality productive forces by integrating the dimensions of labor, objects of labor, and means of labor [44]. The framework encompasses employee quality, managerial capability, innovation, green development, environmental performance, and development capability. To ensure objectivity, we employ a projection pursuit model (PPM) optimized by an accelerated genetic algorithm (AGA) to estimate the level of firms’ new quality productive forces. This approach derives the composite evaluation score based on the structural characteristics and information density of high-dimensional indicators along the optimal projection direction. Indicator weights are determined endogenously by the internal structure and distribution of the sample data rather than through subjective assignment, which reduces human interference while effectively capturing nonlinear relationships among indicators and overall heterogeneity, thereby improving the objectivity and robustness of the evaluation results [45]. Detailed indicator definitions are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Construction of the Indicator System for New Quality Productive Forces in Coal Enterprises.

4.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

The core explanatory variable in this study is firms’ digital–intelligent transformation (DIT). Building on the connotation and key features of digital–intelligent transformation in the coal sector, we develop a measurement system that combines text analysis and quantitative proxies. We then apply the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method to weight the indicators and obtain a composite index of each coal enterprise’s digital–intelligent transformation level. As shown in Table 2, the measurement system comprises three dimensions: digital–intelligent cognition, digital–intelligent investment, and digital–intelligent output.

Table 2.

Indicator System for Digital–Intelligent Transformation in Coal Enterprises.

The digital–intelligent cognition indicator is constructed as follows. First, we compile a “digital–intelligent transformation” lexicon covering technology support and scenario applications based on firms’ annual reports as well as national policy documents, major conferences, and news reports. Second, using Python (3.7), we extract word-frequency information from the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section of firms’ annual reports. We conduct word segmentation and keyword matching, and then aggregate the occurrences of the keywords to obtain the cognition score. Finally, given the right-skewed distribution of the raw counts and to reduce scale differences across indicators, we use the natural logarithm of (the number of digital–intelligent keywords in the MD&A text + 1) as the firm-level measure of digital–intelligent cognition.

Digital–intelligent investment is proxied by the intensity of investment in digital–intelligent assets, while digital–intelligent output is proxied by digital–intelligent innovation efficiency.

4.2.3. Mediating Variable

Resource allocation efficiency in this study is measured as the absolute value of the residual obtained from the Richardson model. Specifically, a larger absolute residual (i.e., a higher RA value) indicates a greater deviation of a firm’s actual investment from its optimal investment level and thus lower resource allocation efficiency; conversely, a smaller value implies higher resource allocation efficiency [46]. This measure can accurately capture misallocation in the distribution of production factors—such as capital, technology, and labor—within coal enterprises, and is particularly suitable for assessing the rationality of dedicated investments in intelligent mining equipment and green technology R&D under digital–intelligent transformation.

4.2.4. Moderating Variable

The moderating variable is local economic performance assessment pressure (EP). Its primary role is to moderate the strength of the transmission pathway “digital–intelligent transformation–resource allocation efficiency-new quality productive forces,” thereby revealing heterogeneous effects of the external institutional environment on firms’ technological transformation and productivity upgrading. Following Chai et al. [47], we use the annual GDP growth target announced at the beginning of each year in the provincial government work report of the province where each listed coal enterprise is located as a proxy for local economic performance assessment pressure. These growth targets are explicitly policy-oriented and directly reflect the intensity of local governments’ economic assessment pressure: higher GDP growth targets imply stronger incentives for local governments to pursue short-term economic expansion, greater motivation to intervene in the operating decisions of firms—especially pillar industries such as coal—and thus higher economic performance assessment pressure faced by firms [48].

In this study, firm operating efficiency (OE) is proxied by the asset turnover ratio. Asset turnover is commonly used to evaluate the quality of asset management and operational efficiency, as it reflects the speed at which a firm’s total assets are converted from inputs into outputs over the course of operations. Therefore, it provides an effective measure of firm operating efficiency.

4.2.5. Control Variables

Operating capability (OC) is measured as the natural logarithm of a firm’s annual operating revenue. Tobin’s Q (TQ) is measured as the ratio of a firm’s market value to total assets. Leverage (Lev) is measured as the ratio of total liabilities to total assets at year-end. Firm size (Size) is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets at year-end. Board size (Board) is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of board directors. Listing age (FirmAge) is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of years since listing.

4.2.6. Data Sources

Given the research scope and data availability, we construct a panel dataset of 30 Chinese listed coal companies over 2012–2024. Firm-level data are obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, supplemented with companies’ annual and financial reports, as well as ESG index data from Huazheng. Data on local GDP growth targets are collected from government work reports issued by the relevant provincial governments. After data cleaning, the final sample comprises 390 firm-year observations. Table 3 reports descriptive statistics for all variables.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables.

5. Empirical Results and Discussion

5.1. Measurement and Analysis of New Quality Productive Forces in Coal Enterprises

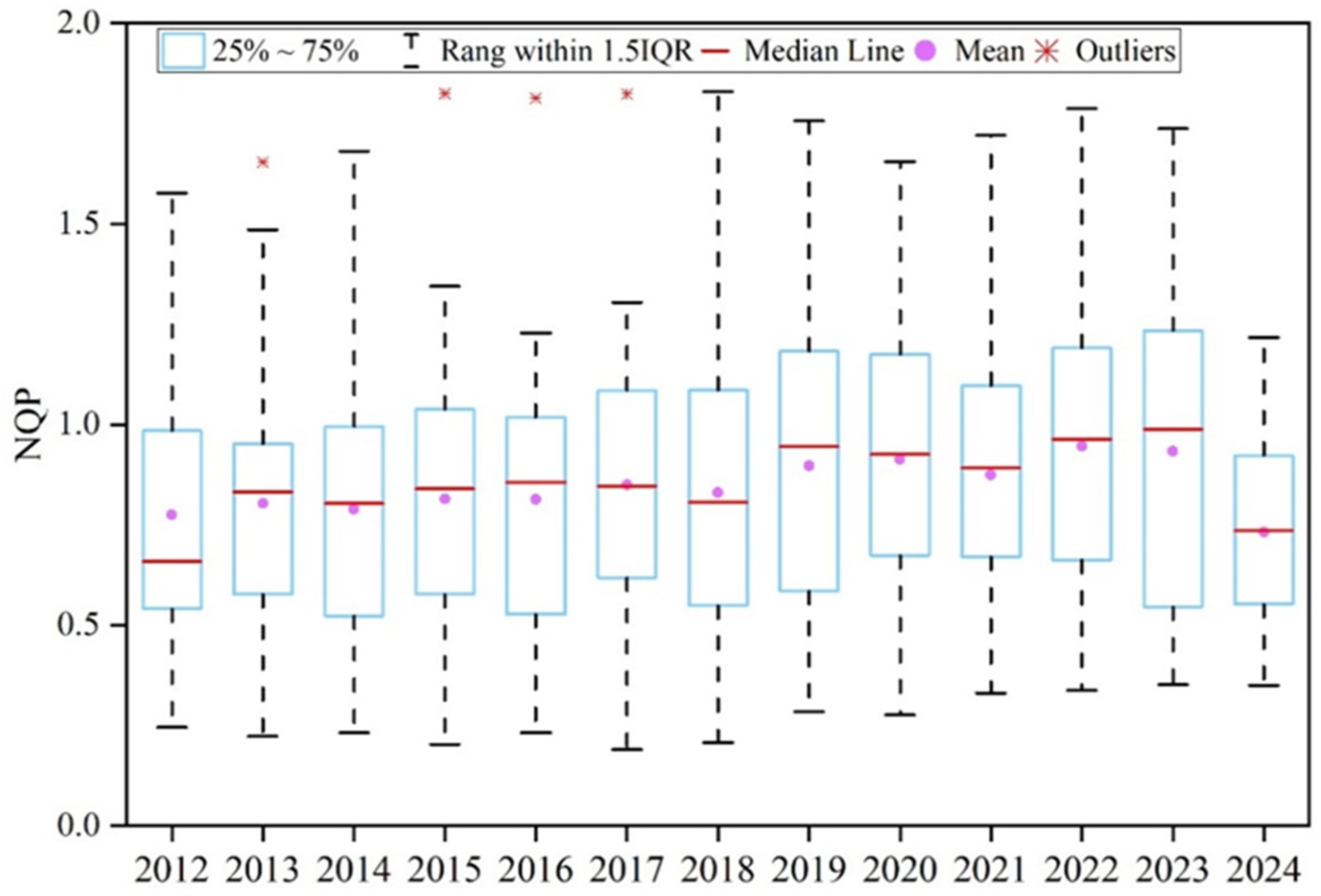

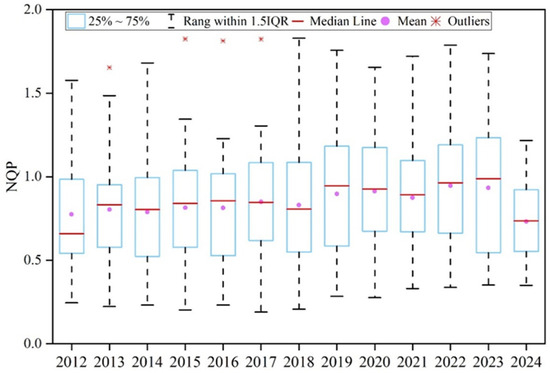

Figure 3 presents the boxplot distribution of new quality productive forces (NQP) for coal enterprises from 2012 to 2024. Overall, both the median and the mean show a fluctuating upward trend, indicating that NQP has improved steadily over the sample period and that the overall quality of industry development has continued to advance. In particular, after 2018, the median and mean shift upward more noticeably, suggesting a pronounced stage-wise improvement. This pattern is consistent with the structural upgrading of the coal sector under the ongoing digital–intelligent, smart, and green transformation.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of New Quality Productive Forces in Chinese Coal Enterprises, 2012–2024.

In 2024, however, both the median and the mean decline visibly, implying a short-term downturn in NQP. This may reflect that, as the transformation enters a deepening phase, earlier high investments and organizational adjustment costs become more salient, while efficiency gains and innovation returns have not yet been fully realized. Such a decline is more likely a short-term fluctuation during transition rather than a reversal of the long-term upward trajectory.

In terms of dispersion, the interquartile range remains relatively stable across years. Although substantial differences in NQP exist across firms, these disparities do not appear to widen markedly over time, indicating no clear evidence of increasing within-industry polarization. Moreover, several high-value outliers emerge gradually during 2015–2017, suggesting that a subset of coal enterprises achieved breakthrough improvements in NQP-possibly associated with earlier adoption of digital–intelligent transformation, technological upgrading, and managerial innovation.

5.2. Baseline Regression Results

Based on the baseline specification and the Hausman test, we adopt a two-way fixed-effects model for the empirical analysis. Table 4 reports the estimated effects of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces in coal enterprises. Column (1) presents results without control variables, while Columns (2)–(7) sequentially add operating capability (OC), firm value (TQ), leverage (Lev), firm size (Size), board size (Board), and listing age (FirmAge), respectively.

Table 4.

Baseline Regression Results.

The results show that across all specifications, the coefficient on the core explanatory variable remains significantly positive at the 10% level, indicating that advancing digital–intelligent transformation significantly enhances the level of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises. This finding supports Hypothesis H1. Regarding the control variables, operating capability (OC), leverage (Lev), firm size (Size), board size (Board), and listing age (FirmAge) all exhibit significantly positive effects on new quality productive forces. The positive impact of operating capability suggests that higher operating revenue not only dilutes the fixed costs of digital–intelligent investment and strengthens the sustainability of R&D expenditure, but also accelerates knowledge iteration and the translation of R&D into practice through market feedback, forming a positive “revenue–R&D–efficiency” feedback loop. The significantly positive coefficient on leverage implies that more highly leveraged firms can rely on external financing to strengthen funding support for digital–intelligent transformation, thereby further improving productivity. Board size is positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that a moderately larger board can pool diverse professional expertise and industry experience, generate knowledge aggregation effects, and enhance the board’s ability to evaluate and endorse digital–intelligent transformation, green low-carbon technologies, and new business models at the strategic level. It may also help firms secure critical technological, capital, and policy resources, thereby reducing uncertainty and transaction costs associated with innovation. The coefficient on listing age is significantly positive, indicating that more established firms may benefit from accumulated experience, technological capabilities, and market foundations, allowing them to better integrate digital technologies with existing competencies and achieve further productivity gains.

In contrast, firm value (TQ) exhibits a significantly negative coefficient, implying an inverse association between market valuation and new quality productive forces. Specifically, a 1% increase in Tobin’s Q is associated with a 0.1586% decrease in new quality productive forces. A plausible explanation is that when Tobin’s Q rises and market valuation becomes relatively high—particularly when market value exceeds replacement cost—management may have stronger incentives to pursue short-term gains through capital operations rather than allocate resources to long-horizon, high-uncertainty projects such as intelligentization and green transformation. Meanwhile, capital market pricing preferences for resource-based rents may reinforce path dependence toward the traditional logic of “extract more coal–earn more–achieve higher valuation,” further crowding out investment in digital, intelligent, and low-carbon initiatives.

Overall, the stepwise regression results consistently indicate a positive and robust effect of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces in coal enterprises, which remains stable after controlling for a wide range of financial and governance characteristics. Therefore, Hypothesis H1 is supported.

5.3. Endogeneity and Robustness Checks

- (1)

- Instrumental Variable (IV) Approach

This study employs an instrumental variable (IV) approach to address potential reverse causality and endogeneity in the regression model. Specifically, we use the natural logarithm of total river length in the city where a coal enterprise is located as an exogenous instrument for the endogenous explanatory variable, and estimate the model using two-stage least squares (2SLS).

The rationale is as follows. River length is a natural geographic attribute and is unlikely to directly affect a firm’s new quality productive forces, thereby satisfying the exogeneity requirement. At the same time, river length reflects local hydrological density: regions with denser river networks tend to be more ecologically sensitive and are therefore subject to stricter environmental regulation. Greater pressure to protect water environments typically induces local governments to intensify emissions monitoring, safety oversight, and ecological governance for resource-based enterprises. For coal firms, which are exposed to higher pollution risks, a stricter regulatory environment increases incentives to adopt digital monitoring systems, intelligent production equipment, and information-based management platforms to reduce compliance costs and strengthen environmental management capacity, thereby accelerating digital–intelligent transformation. Hence, river length is plausibly correlated with firms’ digital–intelligent transformation through its influence on the intensity of local environmental regulation, satisfying the relevance condition.

The identification tests indicate LM = 19.069 (p = 0.0000), rejecting the null hypothesis of under-identification, and F = 19.022, exceeding the 10% critical value of 16.38, suggesting that the instrument is sufficiently strong. As reported in Table 5, Column (8) confirms the correlation between the instrument and the endogenous regressor, while Column (9) shows that digital–intelligent transformation has a significantly positive effect on firms’ new quality productive forces. Overall, the baseline findings remain robust after accounting for endogeneity.

Table 5.

Endogeneity Test Results.

- (2)

- Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

To mitigate estimation bias arising from sample selection, we conduct propensity score matching (PSM). First, we classify firms into high-DI and low-DI groups based on the annual mean of the digital–intelligent transformation level. Firms in the high-DI group are assigned DIM = 1, and those in the low-DI group are assigned DIM = 0. As shown in Table 6, Model (10) uses the control variables from the baseline regression as matching covariates. We estimate propensity scores using a Logit model and implement 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching, pairing each high-DI firm-year observation with the closest low-DI observation in terms of propensity score [49]. Model (11) applies radius matching, retaining all control observations within a caliper of 0.05 in propensity score distance [50]. As reported in Table 6, Columns (10) and (11), the coefficient on DI remains significant at the 10% level, indicating that digital–intelligent transformation significantly improves new quality productive forces and that the baseline results are not driven by selection bias.

Table 6.

PSM Test Results.

- (3)

- Excluding the COVID-19 Shock

Because the COVID-19 pandemic had substantial impacts on firms’ operations and productivity, we exclude the year 2020, when the pandemic shock was most severe, and re-estimate the model. As shown in Table 7, the coefficient of digital–intelligent transformation remains significantly positive at the 10% level, suggesting that while COVID-19 may have induced short-term fluctuations in new quality productive forces, it does not alter the long-run positive effect of digital–intelligent transformation. This further supports the robustness of our findings.

Table 7.

Results Excluding the COVID-19 Period.

- (4)

- Adjusting the Sample by Region

Municipalities directly under the central government generally exhibit higher levels of economic development. Their factor agglomeration, degree of policy intervention, and digital infrastructure are substantially stronger than those of other regions, which may affect the generalizability of the estimated impact of digital–intelligent transformation on coal enterprises’ new quality productive forces. Therefore, we re-estimate the model after excluding observations from these municipalities. As shown in Table 8, the main conclusions remain unchanged, indicating that our results are not driven by extreme values or structural differences associated with more developed regions.

Table 8.

Regression Results after Excluding Firms Located in Centrally Administered Municipalities.

5.4. Heterogeneity Testing

Regional heterogeneity. Differences in regional resource endowments imply that coal enterprises may adopt heterogeneous development models, which can lead to heterogeneous effects of digital–intelligent transformation on firms’ new quality productive forces. Accordingly, we divide the sample by geographic location and conduct subgroup regressions for firms in eastern, central, and western China. The results are reported in Columns (16)–(17) of Table 9. The estimates indicate that, relative to the eastern and western regions, coal enterprises in central China are better able to leverage digital–intelligent transformation to promote the development of new quality productive forces. This regional disparity may reflect substantial cross-regional differences in economic development, industrial structure, resource endowments, and policy environments in China. The coefficient for eastern firms is negative but statistically insignificant, which may be attributable to the early start of digitalization and increasingly saturated infrastructure in the eastern region, resulting in diminishing marginal returns; moreover, high post-implementation maintenance costs, together with pressures from resource depletion and industrial relocation, may hinder the translation of digital–intelligent investments into NQP improvements. For central China, the coefficient is significantly positive at the 1% level, suggesting that the region’s coal industry benefits from a relatively strong scale base and comparative advantage and is currently in a phase of rapid digital–intelligent penetration. Under the combined effects of industrial transfer/undertaking, policy support, and factor reallocation, digital–intelligent transformation is more likely to enhance NQP by improving production efficiency and resource allocation efficiency. The coefficient for western firms is positive but statistically insignificant, possibly because relatively weak digital infrastructure and higher transformation costs mean that the enabling effects of digital–intelligent transformation remain at an early stage of accumulation and have not yet fully materialized.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity Analysis.

Heterogeneity by marketization level. Beyond geographic location, the productivity-enhancing effect of digital–intelligent transformation may also vary with the degree of regional marketization. We therefore use the regional marketization index provided by prior studies [51] as a proxy for marketization level. Using the annual national median, we classify regions into high- and low-marketization groups, and then conduct subgroup regressions accordingly. As shown in Columns (19)–(20) of Table 9, the coefficient on the core explanatory variable (DIT) is significantly positive at the 5% level in the low-marketization subsample, whereas it is negative but insignificant in the high-marketization subsample. This suggests that the effect of digital–intelligent transformation on NQP is stronger in less marketized regions. A plausible explanation is that low-marketization regions often feature concentrated coal resources but relatively inefficient traditional allocation mechanisms; firms may be technologically lagging and managerially conservative, leaving greater room and stronger urgency for transformation, while government support tends to be more intensive. In such contexts, digital–intelligent transformation can improve resource allocation, stimulate innovation, and promote managerial change, thereby significantly enhancing NQP under supportive policies. In contrast, in highly marketized regions, coal markets are more competitive and firms may already operate with relatively efficient resource allocation, mature management systems, and near-saturated technologies. Digital–intelligent transformation may face higher costs and limited room for breakthrough, with less policy support; moreover, coal firms may also face challenges in attracting and retaining digital–intelligent talent. These factors can weaken the observable impact of digital–intelligent transformation on NQP, resulting in statistically insignificant effects.

5.5. Mechanism Analysis

- (1)

- Mediation via Resource Allocation Efficiency

To uncover the transmission mechanism through which digital–intelligent transformation promotes the development of new quality productive forces, we use resource allocation efficiency as the mediating variable and apply the three-step mediation procedure. Table 8 reports the estimation results. In Column (21) of Table 10, the coefficient on digital–intelligent transformation is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that digital–intelligent transformation significantly improves resource allocation efficiency in coal enterprises (given that a lower QV implies higher efficiency). Column (22) further shows that the coefficient on resource allocation efficiency is also significantly negative, suggesting that improvements in allocation efficiency contribute to higher new quality productive forces. The estimated mediating effect accounts for 14.89% of the total effect, thereby supporting Hypothesis H2.

Table 10.

Mediation Test Results for Resource Allocation Efficiency.

- (2)

- Moderation Mechanism

To further examine the moderating role of local economic performance assessment pressure, we use local governments’ GDP growth targets as a proxy for such pressure and construct the moderating variable accordingly. The regression results are presented in Table 9. The coefficients on the interaction term between digital–intelligent transformation and local economic performance assessment pressure are significantly negative at the 10% level, indicating a negative moderating effect: higher GDP growth targets weaken the positive relationship between digital–intelligent transformation and firms’ new quality productive forces. This finding supports Hypothesis H3a.

- (3)

- Moderated Mediation Test

We further incorporate interaction terms between local economic performance assessment pressure and both digital–intelligent transformation and resource allocation efficiency into the mediation framework. Table 11, Columns (23) and (24), capture the role of local economic performance assessment pressure in the first and second stages of the mediated pathway, respectively, and test whether it moderates (i) the effect of digital–intelligent transformation on resource allocation efficiency and (ii) the effect of resource allocation efficiency on new quality productive forces.

Table 11.

Moderated Mediation Test Results.

Consistent with the earlier evidence, Table 12 (Column (28)) shows that the interaction between local economic performance assessment pressure and digital–intelligent transformation is significantly negative at the 10% level, suggesting that such pressure significantly weakens the enabling effect of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces. Table 11 (Column (23)) further indicates that the interaction term between digital–intelligent transformation and local economic performance assessment pressure is significantly positive at the 5% level, implying that local economic performance assessment pressure suppresses the efficiency-enhancing effect of digital–intelligent transformation on resource allocation (because a higher QV corresponds to lower allocation efficiency). Hypothesis H3b is thus supported. Table 11 (Column (24)) shows that the interaction between digital–intelligent transformation and local economic performance assessment pressure is significantly negative at the 10% level, indicating that such pressure reduces the direct effect of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces. Moreover, the coefficient on the interaction between local economic performance assessment pressure and resource allocation efficiency is positive, suggesting that local economic performance assessment pressure weakens the contribution of improved resource allocation efficiency to the development of new quality productive forces. These results support Hypothesis H3c.

Table 12.

Moderation Test Results.

5.6. Cost–Benefit Dynamics and Context Dependence

Although the empirical results indicate that digital–intelligent transformation significantly enhances the level of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises, consistent with the findings of Yu et al., this enabling effect is neither “low-cost” nor “instantaneous.” Instead, it is gradually realized under sufficient investment scale and supportive institutional conditions, and its practical impact likely depends on the joint influence of cost structures, pathways through which returns are realized, and the external environment [52].

Digital–intelligent transformation in coal enterprises typically involves substantial upfront investment, including expenditures on intelligent equipment and information infrastructure, digital platforms and system integration, as well as the recruitment and training of digital and cross-disciplinary talent. Compared with light-asset or technology-intensive industries, coal enterprises are characterized by high asset specificity, complex production systems, and harsh operating environments, which raise the adaptation and implementation costs of digital–intelligent technologies and lengthen payback periods. Moreover, in the short run, digital–intelligent transformation may trigger organizational adjustment costs and managerial friction, thereby imposing transitional pressure on firm performance.

The positive effect of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces is therefore more likely to materialize in the medium to long term. On the one hand, by enhancing the visibility, controllability, and coordination of production processes, digital–intelligent transformation can reduce safety risks, curb resource losses, and improve energy efficiency, thereby simultaneously improving productive efficiency and environmental performance. On the other hand, by reshaping resource allocation mechanisms, it facilitates the efficient allocation of capital, technology, labor, and data, providing sustained momentum for the cultivation of new quality productive forces. The significant mediating role of resource allocation efficiency further suggests that the benefits of digital–intelligent transformation do not primarily arise from simple technological substitution, but rather from gradual factor reallocation and structural optimization.

Importantly, the cost–benefit profile of digital–intelligent transformation is heterogeneous and highly contingent on contextual conditions. Under strong local economic performance assessment pressure, enterprises are more likely to be constrained by short-term output targets, which crowds out resources for high-investment, long-horizon digital–intelligent projects and weakens the long-run return potential of transformation [53]. These findings imply that when the external institutional environment places excessive weight on short-term economic performance, the gains from digital–intelligent transformation may fail to fully offset its costs, thereby dampening firms’ incentives to undertake and sustain transformation.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study first develops a theoretical framework to clarify the mechanisms through which digital–intelligent transformation, local economic performance assessment pressure, and resource allocation affect the development of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises, and specifies the underlying transmission pathways. We then conduct empirical analyses using a two-way fixed-effects baseline model, a mediation model, and moderation models. A series of endogeneity and robustness checks—including an instrumental-variable (IV) approach, propensity score matching (PSM), and excluding the COVID-19 shock—are implemented to ensure the reliability of the results. In addition, we conduct mechanism tests that focus on the mediating role of resource allocation efficiency and the moderating role of local economic performance assessment pressure, and further examine moderated mediation to identify the key drivers of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises.

The main findings are as follows. First, digital–intelligent transformation significantly promotes the development of new quality productive forces in coal enterprises, and this result remains robust after the IV estimation, PSM, and excluding the COVID-19 period. Second, resource allocation efficiency plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between digital–intelligent transformation and new quality productive forces. The mediating effect accounts for 14.89% of the total effect, indicating that digital–intelligent transformation enhances new quality productive forces partly through improving firms’ resource allocation efficiency. Third, local economic performance assessment pressure exerts a negative moderating effect on the positive impact of digital–intelligent transformation on new quality productive forces, and this negative moderation persists along the mediated pathway via resource allocation efficiency.

6.2. Policy Implications

(1) At the firm level (coal enterprises): Anchoring core capabilities and leveraging digital–intelligent transformation to achieve a leap in new quality productive forces.

Coal enterprises should act along four dimensions—cognition, investment, management, and mechanisms—to translate digital–intelligent transformation into an endogenous driver of new quality productive forces. In terms of strategic cognition, firms should avoid the common pitfalls of “hardware over application” and “form over substance.” Digital–intelligent transformation is not merely a single upgrade of intelligent equipment; rather, it is a system-wide change spanning the entire value chain of production, management, and coordination. It should therefore be incorporated into long- and medium-term strategic planning. Firms should design differentiated transformation pathways aligned with their resource endowments, capacity scale, and technological foundations, rather than following generic trends.

In terms of investment, firms should build an integrated “technology–talent–data” investment system. This includes increasing investment in core equipment and systems such as intelligent mining machinery, industrial internet platforms, and data middle platforms, and prioritizing the integration of big data analytics, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things into critical processes such as geological exploration, gas control, and intelligent dispatching. Firms should also establish dedicated R&D funds for digital–intelligent transformation, collaborate with universities and research institutes to tackle key technological bottlenecks, and attract high-end talent (e.g., algorithm engineers and data analysts). In parallel, tiered digital-skills training programs should be implemented to build multidisciplinary transformation teams. Moreover, enterprises should upgrade IT infrastructure in an orderly manner and accumulate high-quality data assets to strengthen the foundation for data-driven decision-making.

In management optimization, digital–intelligent tools should be used to break down departmental barriers and information silos, restructure internal governance and management models, and enable digital coordination across production, safety, supply chains, and finance. Supported by intelligent dispatching systems and data analytics, firms can implement refined allocation and dynamic optimization of capital, labor, energy, and technology to reduce resource misallocation and redundant investment. This facilitates a shift in mining organization, equipment maintenance, and safety management from experience-driven operations to data-driven and intelligent decision-making, thereby improving the marginal productivity of production factors. Firms should also build inter-firm collaboration platforms to deepen coordination with upstream and downstream partners and promote resource sharing and efficient linkage across the industrial chain.

(2) At the government level: Strengthening policy guidance and building an enabling system for digital–intelligent transformation and NQP cultivation.

Governments should play a “policy steering” role and create a supportive environment for coal enterprises to cultivate new quality productive forces through digital–intelligent transformation. On the support side, differentiated fiscal, tax, and financial policies are needed: provide targeted subsidies, enhanced tax deductions for R&D expenses, and tax incentives for transformation projects; develop tailored credit products to alleviate financing pressure; and establish a digital–intelligent innovation fund for the coal industry to support core technology R&D, shared platform development, and the scaling of demonstration projects.

On incentives and governance, local government performance assessment systems should be improved by reducing the weight of traditional indicators such as output and capacity expansion, and incorporating progress in digital–intelligent transformation, improvements in new quality productive forces, and low-carbon performance into evaluation criteria. Such reforms can strengthen accountability and encourage more precise and service-oriented policy implementation.

On demonstration and ecosystem building, governments should develop digital–intelligent transformation demonstration projects covering the entire coal value chain and cultivate benchmark enterprises in areas such as intelligent geological exploration, unmanned production processes, digital supply chains, and precision energy management. By summarizing replicable and scalable practices, these programs can drive system-wide upgrading and innovation. Meanwhile, a more complete standard system for coal digital–intelligent transformation should be established, clarifying requirements for data security, technology deployment, and equipment compatibility. Introducing high-quality technology service providers and fostering a collaborative innovation ecosystem—linking government, enterprises, research institutions, and service providers—can offer sustained technical support and service guarantees for transformation.

(3) At the societal level: Building consensus and creating a favorable environment for digital–intelligent transformation–driven industrial upgrading.

The public can contribute through supervision, participation, and dissemination, providing diversified momentum for coal enterprises’ digital–intelligent transformation and NQP cultivation. In terms of communication, multiple channels (e.g., media, community outreach, and industry-oriented science communication) can be used to disseminate the significance, technological achievements, and societal value of transformation, helping to update conventional perceptions of the coal industry as “high-pollution and low-tech,” and fostering broader acceptance and support for transformation in a culture that respects innovation and tolerates exploration.

In terms of oversight and feedback, stakeholders can pay attention to green development and safety performance during transformation and provide constructive suggestions through appropriate channels, encouraging firms to uphold safety and environmental red lines and to integrate digital–intelligent transformation with low-carbon development so that transformation outcomes deliver societal benefits. In terms of talent supply, universities and vocational institutions should be encouraged to optimize program offerings by adding majors and training tracks related to coal digital–intelligent technologies, intelligent mining, and data management. Social organizations can also be encouraged to provide vocational skills training, increasing the supply of digitally skilled workers and alleviating talent shortages, thereby forming a virtuous cycle of “society cultivating talent and enterprises utilizing talent.”

However, this study has several limitations that warrant further research and refinement. First, our analysis relies on group-level data from listed coal companies to examine the drivers of new quality productive forces. Future work could leverage more granular micro-level data at the coal enterprise and individual mine (pit) levels to provide more detailed evidence on policy impacts, thereby improving the explanatory power and practical relevance of the findings. Second, there is still no unified definition of new quality productive forces in the literature. As the concept continues to evolve and expand, future studies should develop more systematic and multidimensional evaluation indicator systems to comprehensively measure the development of new quality productive forces, providing a stronger theoretical basis for policymaking and industry practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.D.; Methodology, J.W. and Y.S.; Software, X.D.; Formal analysis, X.D.; Investigation, X.D.; Data curation, Y.S.; Writing—original draft, X.D.; Writing—review & editing, R.Z.; Visualization, X.D. and J.W.; Supervision, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Zhiyuan Science Foundation grant number 2026220. And The APC was funded by Zhiyuan Science Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z. Digital New Quality Productivity and High-Quality Development of Enterprises. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 109, 104811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Yang, Y.; Xie, E.; Xie, Y. The Dual Effects of Digitization: An Enterprise Perspective. J. Asian Econ. 2025, 100, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]