Abstract

This paper develops a comprehensive macro stress-testing (MST) framework to evaluate the resilience of Saudi Arabia’s financial sector against systemic risk over the period 2010–2025. The approach integrates macro financial linkages, credit risk modeling, and scenario analysis to simulate the impact of severe but plausible shocks on capital adequacy ratios (CAR) and capital shortfalls. Using Saudi macroeconomic data, the study demonstrates that GDP growth and oil price fluctuations are dominant drivers of systemic risk, while inflation and unemployment exert significant but secondary effects. Under severe adverse conditions, the banking sector’s aggregate CAR declines to 9.6%, requiring an estimated capital injection of 3.7% of GDP. The findings underscore the strength of Saudi Arabia’s financial buffers, while emphasizing the importance of dynamic capital buffer calibration, sectoral diversification, and cross-border macroprudential coordination within the GCC. Policy recommendations are provided to enhance stress-testing governance and fiscal and financial alignment. The findings highlight the importance of dynamic counter-cyclical capital buffers, sectoral diversification, liquidity resilience, and enhanced fiscal–financial coordination. Policy recommendations are provided to guide SAMA and the Financial Stability Council in capital planning, stress-test governance, and macroprudential policy design.

1. Introduction

Saudi Arabia’s financial system, one of the largest in the Middle East, has remained relatively stable during recent episodes of global turbulence, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 oil price shock, owing to prudent regulation and substantial capital buffers [1]. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA) has implemented Basel III standards, diversified its supervisory approach, and promoted stress-testing practices aligned with G20 guidelines [2]. However, the increasing integration with global financial markets and the ongoing diversification of the Saudi economy under Vision 2030 have created new channels for systemic risk, including exposure to oil price volatility, foreign exchange fluctuations, and cross-border capital flows [3].

The global financial system has undergone a profound transformation since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The crisis revealed how interconnectedness between banks, capital markets, and the real economy could amplify localized shocks into system-wide crises [4,5]. Traditional risk management tools, centered on micro prudential supervision, proved inadequate for identifying and mitigating these spillovers. In response, regulators introduced macroprudential frameworks that emphasize system-wide resilience rather than the health of individual institutions [6,7].

Macro stress testing (MST) has therefore become an indispensable tool for regulators and policymakers in Saudi Arabia. Unlike micro stress tests, which evaluate the resilience of individual institutions, MST captures feedback effects and contagion mechanisms across the financial system [8]. It provides forward-looking assessments of how adverse macroeconomic scenarios, such as a sharp decline in GDP growth, rising unemployment, or exchange rate pressure, might affect banks’ capital adequacy and liquidity positions [9]. For emerging economies, these tests serve an additional policy purpose, identifying macro-financial linkages that may amplify domestic vulnerabilities during external shocks [10].

The importance of such frameworks is underscored by the Saudi banking sector’s rapid credit growth from 2010 to 2025, as well as its increasing exposure to real estate, consumer, and corporate loans [1]. The interaction between fiscal expansion, oil market cycles, and monetary policy transmission channels implies that systemic stress in Saudi Arabia could arise from both domestic and external sources [11]. Therefore, a comprehensive macro stress-testing framework tailored to the Kingdom’s economic structure and data realities is essential for forward-looking financial stability surveillance.

This study contributes to the literature by developing an evidence-based MST framework customized for Saudi Arabia’s financial sector between 2010 and 2025. It models the probability of default (PD) of banks as a function of key macroeconomic variables such as GDP growth, inflation, unemployment, government debt, exchange rate, and economic growth to capture the complex macro-financial linkages observed in emerging markets. The analysis builds upon the methodology used in the Malaysia-wide stress test (MAST) conducted by [12]. It adapts to the Saudi context, where oil-linked revenues and fiscal buffers play a central role in credit dynamics.

By focusing on systemic vulnerabilities and potential capital shortfalls, the study offers insights into the resilience of the Saudi banking sector. It contributes to the broader discourse on macroprudential policy design in the GCC. It seeks to answer three core questions:

- (1)

- How do macroeconomic shocks translate into banking sector vulnerabilities in Saudi Arabia?

- (2)

- Which macro-financial variables most significantly influence credit risk and capital adequacy?

- (3)

- What policy insights can be drawn for SAMA and other GCC regulators to enhance financial stability under Vision 2030?

In this way, the research not only fills a literature gap on systemic risk assessment in the Kingdom but also provides a comparative perspective for emerging market economies facing similar challenges in financial deepening and regulatory modernization.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Systemic Risk and Macroprudential Frameworks

Systemic risk refers to the potential for widespread disruptions in financial intermediation that severely impact the real economy [4,13]. Following the GFC, central banks and regulators worldwide shifted from a macroprudential focus to a macroprudential approach that explicitly targets systemic vulnerabilities [14]. Macroprudential policy aims to contain the procyclicality of financial systems and limit the buildup of leverage and liquidity mismatch across institutions. The Basel III framework incorporates several macroprudential tools, including counter-cyclical capital buffers, liquidity coverage ratios, and systemic capital surcharges, which help address the time and cross-sectional dimensions of systemic risk [6].

In the Saudi context, SAMA has adopted these instruments and introduced stress-testing regulations to align with international best practice [1]. However, most existing studies on stress testing in the GCC remain qualitative and lack integrated empirical frameworks linking macroeconomic shocks to banking sector capital adequacy [15].

2.2. Macro-Financial Linkages and Credit Risk Transmission

Macro-financial linkages describe the feedback mechanisms between the real economy and the financial system [16]. During economic expansions, credit growth and asset prices reinforce each other, while downturns exacerbate losses through credit contraction and fire-sale effects [17]. Empirical evidence from the OECD and emerging economies suggests that variables such as GDP growth, inflation, and unemployment rates have a significant impact on non-performing loans (NPLs) and default probabilities [18].

In the GCC, research suggests that economic growth and fluctuations in oil prices are the primary determinants of credit risk [11,19]. Saudi banks remain well-capitalized, but their profitability and credit portfolios are sensitive to macroeconomic cycles [3]. Macro stress-testing models that explicitly incorporate these variables enable more accurate estimation of probabilities of default and capital shortfalls.

Despite this rich body of work, few studies systematically apply an integrated MST framework—combining macro financial linkages, VAR modeling, and scenario analysis—to the specific institutional and economic context of Saudi Arabia’s oil-dependent financial system. Our study fills this gap by tailoring the MST approach to Saudi Arabia from 2010 to 2025, capturing the unique role of oil price dynamics, currency peg stability, and fiscal-financial interactions in shaping banking sector resilience. This contributes to the emerging literature on stress testing in emerging and commodity-dependent economies and provides a context-specific framework for macroprudential policy design [3,18].

2.3. Contagion and Interconnectedness Channels

Financial systems are increasingly interconnected through funding, derivatives, and interbank markets. Contagion can spread via solvency, funding liquidity, and market liquidity channels [20]. Studies by [21,22] demonstrate that network topologies influence the propagation of shocks through banking systems. Macro stress-testing frameworks that neglect these channels risk underestimating systemic vulnerability. Hence, the integration of multi-channel contagion mechanisms is a key advancement in modern stress-testing models.

2.4. Empirical Insights from Global and Regional Stress Testing

Stress testing shows how a firm’s operations and financial stability are affected by changes in macroeconomic conditions. It looks at the possible impact on income, liquidity, and capital adequacy, helping to understand how risks spread across the entire portfolio. Internationally, the IMF and ECB have standardized macro stress testing as a core component of their Financial Sector Assessment Programs (FSAP) [7]. For example, the European Banking Authority (EBA) conducts regular EU-wide stress tests that simulate adverse macroeconomic scenarios and assess capital shortfalls across banks. Similarly, the Bank of England integrates market, credit, and liquidity risk in its system-wide stress tests [23]. Evidence from these programs indicates that credit risk remains the dominant channel of systemic losses.

In Malaysia, the MAST framework (2016) demonstrated that even under severe adverse scenarios, capital buffers can absorb significant losses without resulting in bank failures. This experience offers valuable lessons for Saudi Arabia. Comparatively, studies on GCC banking systems highlight the importance of integrating oil-price and fiscal variables into stress-testing [24]. These insights support the development of a Saudi-specific macro stress testing model that captures the unique interplay between energy markets and financial stability.

2.5. Conceptual Gap and Contribution

Although numerous studies have explored macro stress testing in advanced economies, there is limited empirical work addressing systemic risk in the Saudi banking sector from a macro-financial perspective. Most available research either examines individual bank soundness or focuses on oil-market exposure without quantifying system-wide capital resilience. This paper bridges that gap by developing an integrated framework that links macroeconomic drivers to banking sector solvency and assesses aggregate capital adequacy under multiple adverse scenarios. The approach provides a policy-relevant contribution to Saudi Arabia’s financial stability architecture and to the global literature on stress testing in resource-based economies.

3. Methodology

The methodological framework for this study integrates both conceptual and empirical components of macro stress testing (MST), drawing upon established practices of the International Monetary Fund [7], the Bank for International Settlements [25], and comparable studies in emerging markets [10,12]. The goal is to design a Top-Down (TD) model that quantifies the resilience of Saudi Arabia’s banking sector under severe but plausible macroeconomic shocks between 2010 and 2025.

The TD approach is chosen because it allows consistent, system-level assessment using aggregated supervisory and macroeconomic data, reducing dependence on bank-specific internal models while maintaining analytical rigor [26].

3.1. Overall Framework

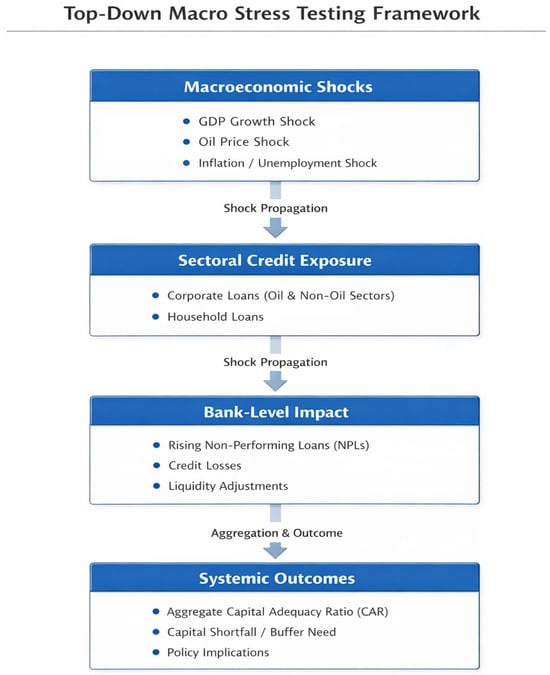

Based on the previous literature review, we developed a flow-chart model as follows in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Stress-Testing Framework Flowchart. Source: Developed by the Authors.

The macro stress-testing process comprises five interlinked stages, provided in the following Table 1.

Table 1.

The macro stress-testing process.

The structure ensures internal consistency and transparency [9].

3.2. Modeling Framework and Econometric Specification

The model follows a macro-financial linkages approach in which each bank’s credit risk exposure is modeled as a function of selected macroeconomic indicators.

3.2.1. Credit Risk Equation

The Probability of Default (PD) at time t is derived from the ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to total loans:

PDt = NPLt/Total Loanst

Following [27] and recent extensions by [28], the PD is converted into a macro-index using a logit transformation:

yt = ln (PDt/(1 − PDt))

Changes in yt; are regressed on key macroeconomic variables:

where the vector Xt includes GDP growth, inflation, unemployment, exchange rate, government debt/GDP, and economic growth. This specification enables the estimation of both contemporaneous and lagged effects using a Vector Autoregression (VAR) framework when multivariate dynamics are significant.

Δyt = β0 + Σi=1k βi Xi,t + εt

3.2.2. Model Selection and Estimation

The VAR approach was selected because it allows for the modeling of dynamic interrelationships among multiple macroeconomic and financial variables simultaneously, capturing feedback effects that are essential for stress testing. Unlike single-equation or static models, VAR can accommodate endogenous interactions between GDP, oil prices, inflation, unemployment, and banking sector indicators, which are central to our study of systemic risk in Saudi Arabia.

Additionally, VAR provides a flexible framework to simulate the propagation of shocks and generate scenario-based forecasts, making it well-suited for macro stress testing where understanding the time-path of responses is crucial. We have added a brief explanation in the methodology section to clarify this rationale and to guide readers on why VAR was chosen over alternative approaches such as single-equation regressions or structural models.

A VAR specification is typically adequate for capturing macro-financial feedback in quarterly data [29]. Parameters are estimated via Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) under stability constraints. Model adequacy is verified using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and serial-correlation diagnostics. For robustness, a Bayesian Vector Autoregressive (BVAR) model can be app lied to address small-sample uncertainty [30]. The summary of the variables, expected signs, and data sources is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the variables, expected signs, and data sources.

3.3. Scenario Design and Stress Calibration

Stress scenarios are constructed to represent baseline, adverse I, and adverse II conditions over a three-year horizon (2025–2027). Each scenario applies shocks consistent with historical extremes in Saudi macroeconomic data (2010–2025), given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Saudi Arabian macro-economic data shocks.

The shocks are based on one to two standard deviations of historical movements in each variable [7,25]. The adverse II scenario corresponds roughly to conditions similar to 2020’s oil-price collapse compounded by global financial tightening.

3.4. Solvency and Capital Adequacy Computation

The Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) is calculated according to the Basel III standard:

where Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA) comprise credit, market, and operational components, and the post-stress CAR for each scenario is derived by adjusting regulatory capital and RWA according to projected PDs and losses.

CAR = Regulatory Capital/Risk-Weighted Assets

If post-stress CAR < 10.5% (minimum Basel III requirement plus conservation buffer), the shortfall is computed as follows:

Capital Shortfalli = (10.5% − CARi (post)) × RWAi

The aggregate systemic shortfall is expressed as a percentage of GDP to gauge fiscal implications [12].

A stylized example of CAR computation is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

CAR calculations.

3.5. Sensitivity and Robustness Checks

To ensure reliability, the model undergoes several robustness assessments:

- Elasticity Testing: Evaluate the marginal impact of ±1 SD change in each macro variable on PD.

- Alternative Specifications: Compare VAR vs. BVAR vs. ARDL models for parameter stability.

- Reverse Stress Testing: Identify the minimum shock magnitude required to breach the 10.5% CAR threshold [31].

- Cross Validation: Compare results against parallel MST exercises in Malaysia and Bahrain to benchmark systemic sensitivity [12,32].

3.6. Data and Implementation Strategy

Data are obtained from the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA), General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT), the World Bank, and the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database. The study employs quarterly data (2010–2025) to ensure granularity sufficient for macro financial interactions. Missing observations are imputed using multiple imputation techniques to preserve sample size [33].

All computations are implemented in Python 3.12 and EViews 13, ensuring replicability. Parameter uncertainty is assessed through bootstrapped confidence intervals (10,000 iterations) following EBA (2023) standards for stress-testing disclosure.

3.7. Expected Analytical Outcomes

The final model produces estimates of:

- Macro financial elasticities (β-coefficients) indicating the sensitivity of bank PDs to each macro variable;

- Scenario-adjusted CARs for each bank category;

- Aggregate capital shortfall (% of GDP) under baseline and adverse scenarios;

- Policy elasticities, demonstrating how fiscal and monetary adjustments affect systemic resilience.

These outcomes enable the identification of key macroprudential levers, such as counter-cyclical capital buffers or liquidity coverage ratios, that can mitigate the propagation of systemic risk in the Saudi financial system.

4. Data and Proposed Empirical Analysis

4.1. Data Sources and Coverage

The empirical component of this research utilizes quarterly data from Q1 2010 to Q1 2025, capturing both pre- and post-pandemic economic conditions and major financial market reforms in Saudi Arabia. The data is organized into three tiers, as listed in the following table. The primary data sources are provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Primary data sources.

All variables are seasonally adjusted and transformed to log differences where appropriate to ensure stationarity. Missing observations, primarily from the early 2010–2012 periods, were interpolated using the multiple imputation method developed by [33].

The dataset provides a sufficient number of observations (≈approximately 60 quarters) for VAR-based estimation. It enables the assessment of structural changes before and after regulatory milestones, such as the full implementation of Basel III in 2018 and the fiscal diversification reforms under Vision 2030, which began in 2016.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics (2010–2025)

Table 6 summarizes the descriptive statistics of key macro-financial variables.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of key macro-financial variables.

The data reveal strong fiscal buffers and consistent CAR levels above 15%, confirming the pre-shock soundness of Saudi banks. However, variance in GDP growth and oil prices indicates exposure to cyclical volatility, a crucial input for scenario calibration.

4.3. Model Estimation and Results

4.3.1. Regression Results

A baseline VAR (2) model was estimated with Δyₜ (the logit-transformed PD) as the dependent variable. Table 7 presents the estimated elasticities.

Table 7.

Estimated elasticities.

The signs conform to theoretical expectations, declines in GDP growth or oil prices increase PDs, while rising inflation and unemployment exacerbate credit risk. Exchange rate pass-through effects are mild due to the SAR to USD peg, but become more relevant under global tightening episodes.

The model explains approximately 68% of the variation in PD (Adj. R2 = 0.68), consistent with [7] benchmarks for emerging market stress-testing accuracy.

4.3.2. Impulse Response and Shock Analysis

Impulse response functions (IRFs) indicate that a one-standard-deviation drop in GDP growth increases PD by approximately 0.42 percentage points after two quarters. Similarly, a one SD increase in unemployment increases PD by approximately 0.34 points, confirming the pro-cyclicality of credit risk. Inflation shocks lead to short-term deterioration in loan quality, while oil price shocks have lagged effects on bank capital through corporate exposures in energy-linked sectors.

Variance decomposition analysis attributes about 45% of PD fluctuations to GDP growth shocks and 18% to unemployment changes, underscoring the dominance of fundamental sector drivers in systemic stress.

4.4. Scenario Simulation Results

The estimated model was used to project PD and CAR trajectories under the three scenarios (baseline, adverse I, and adverse II) introduced earlier. Table 8 summarizes aggregate results.

Table 8.

Summaries of aggregate results.

Under Adverse II, aggregate CAR drops below the 10.5% regulatory threshold, requiring a system-wide recapitalization of almost 3.7% of GDP (approx SAR 120 billion). This shortfall is manageable within Saudi Arabia’s fiscal capacity, but it signals potential liquidity strain if combined with external funding pressures.

The pattern mirrors Malaysia’s MAST findings [12], where a 5% CAR decline in severe conditions required a capital injection of nearly 3.5% of GDP. Comparatively, GCC neighbors such as Bahrain and Kuwait exhibited similar elasticities [15,32], suggesting regional consistency in the transmission of macro financial stress.

4.5. Cross-Country Comparative Insights

The comparison highlights Saudi Arabia’s unique dependence on oil cycles and exchange rate stability as transmission mechanisms for systemic stress. The findings support the argument for counter-cyclical buffers linked to oil revenue volatility, consistent with the [7] recommendations for resource-based economies. Table 9 provides the summary of cross-country comparative insights.

Table 9.

Summary of Cross-country comparative insights.

4.6. Policy-Relevant Interpretation

The results indicate that Saudi banks are robust under moderate stress but sensitive to combined shocks in GDP and oil. Key policy implications include:

- Macroprudential Calibration: Adopt dynamic capital buffers that tighten during boom periods and loosen during downturns.

- Diversification Incentives: Encourage banks to reduce sectoral concentration in oil-linked industries.

- Liquidity Management: Enhance contingent liquidity lines through SAMA’s repo facilities for stress periods.

- Data Transparency: Improve granularity of loan-level and off-balance sheet data for more precise MST calibration.

5. Findings, Conclusions, and Policy Implications

5.1. Synthesis of Findings

This study developed a macro stress-testing framework to evaluate systemic risk and financial sector resilience in Saudi Arabia between 2010 and 2025. By linking key macroeconomic variables to banks’ probabilities of default (PDs) through a top-down econometric model, it quantified how adverse macro-financial conditions are transmitted through the banking system.

The empirical results show that:

- GDP growth and oil price shocks exert the most decisive influence on credit risk, confirming the pro-cyclicality of bank asset quality in Saudi Arabia’s oil-based economy.

- Inflation and unemployment contribute to short-term deterioration in loan performance, reflecting sensitivity to domestic demand conditions.

- Exchange rate and government-debt variables, though stable in regular times, amplify stress when combined with global tightening or fiscal deficits.

- The post-stress CAR remains above the regulatory threshold under moderate shocks (Adverse I). However, it falls to around 9.6% in severe conditions (Adverse II), requiring an estimated capital injection of 3.7% of GDP.

Table 10 summarizes the key empirical insights and their macro prudential relevance.

Table 10.

Key empirical insights and their macro prudential relevance.

Table 10 systematically translates empirical stress-testing results into operational macroprudential policy actions. The table links each major risk transmission channel identified in the model to a corresponding regulatory response, implementation tool, and expected stabilizing effect.

First, the empirical finding that GDP growth and oil price shocks are the dominant drivers of credit risk confirms the strong pro-cyclicality of bank asset quality in Saudi Arabia’s oil-dependent economy. During economic expansions and oil price booms, credit grows rapidly, and risk tends to be underestimated, while downturns generate sharp deterioration in asset quality. This motivates the recommendation to introduce a dynamic counter-cyclical capital buffer linked to the credit-to-GDP gap and supported by semi-annual internal stress testing. The expected effect is to accumulate capital buffers during upswings and release them during downturns.

Second, the sensitivity of loan performance to inflation and unemployment reflects short-term exposure to domestic demand fluctuations and household purchasing power. These dynamics increase liquidity pressure and refinancing risk during tightening cycles or labor market stress.

Third, although exchange rate and government debt variables remain stable under normal conditions, the stress scenarios demonstrate that they amplify systemic risk when combined with global monetary tightening or fiscal pressures. This interaction highlights the importance of institutional coordination between fiscal and financial authorities. The recommended policy response is enhanced fiscal and financial coordination through structured mechanisms.

Fourth, sectoral concentration risks, particularly exposure to oil-linked corporates, are implicitly captured in the sensitivity of credit risk to oil price shocks. The recommended response is to promote sectoral diversification by applying differentiated sectoral risk weights and encouraging SME financing.

Finally, the stress test shows that while the aggregate capital adequacy ratio remains above regulatory thresholds under moderate scenarios, it declines to approximately 9.6% under severe stress, implying a potential capital shortfall equivalent to about 3.7% of GDP. This quantitative result justifies stronger capital buffer calibration, forward-looking capital planning, and improved data transparency. The establishment of granular credit registries and the regular publication of macro stress-testing outcomes enhance supervisory effectiveness, market discipline, and investor confidence.

5.2. Comparative and Regional Perspective

Comparing results across Malaysia, Bahrain, and Kuwait reveals that Saudi Arabia’s banking system ranks among the most resilient in the GCC region, yet exhibits greater macro-financial cyclicality due to its oil dependence. Malaysia’s MAST [12] achieved comparable stability through diversification of credit exposures and active macro-prudential calibration.

By contrast, Saudi Arabia’s stress outcomes indicate room for improvement in sectoral diversification and dynamic capital-buffer adjustment, especially as Vision 2030 initiatives expand non-oil sectors and expose banks to new credit risks.

In the GCC context, the results strengthen the argument for a regional stress-testing platform, coordinated by the GCC Monetary Council or Arab Monetary Fund, to harmonize methodologies and data standards for systemic risk assessment [7,25].

5.3. Policy Framework for Saudi Arabia

The empirical results provide an evidence-based foundation for policy design under the Saudi Central Bank’s financial stability mandate.

The dynamic counter-cyclical capital buffer (CCyB) can be operationalized by linking buffer levels to the credit-to-GDP gap, a widely used indicator of cyclical credit expansion. During periods of strong credit growth relative to GDP, SAMA could gradually increase the CCyB to build additional capital buffers. Conversely, during downturns or credit contractions, the buffer can be partially released to support lending and absorb losses, ensuring that banks remain resilient without constraining economic recovery.

Implementation would require semi-annual monitoring of macroeconomic and credit indicators, stress-testing of banks’ capital adequacy under alternative scenarios, and regulatory guidance communicated through formal directives or FSC coordination. Similar approaches could be applied to sectoral diversification policies, liquidity requirements, and fiscal–financial coordination, tailoring each tool to the observed risk exposures in the banking sector.

Specifically, the dominant influence of GDP growth and oil price shocks on credit risk directly motivates the introduction of a dynamic counter-cyclical capital buffer and sectoral exposure limits to mitigate pro-cyclicality and concentration risk. The observed sensitivity of loan performance to inflation and unemployment supports strengthening liquidity resilience and forward-looking stress testing to absorb short term macro demand shocks. The amplification role of exchange rate and government debt variables under global tightening conditions justifies enhanced fiscal–financial coordination and contingency capital planning frameworks. Furthermore, the finding that aggregate CAR remains above regulatory thresholds under moderate stress but declines to approximately 9.6% under severe scenarios informs the calibration of capital buffers and the estimated scale of potential public or private capital backstopping (3.7% of GDP).

To improve transparency and operational relevance, we have consolidated these linkages in a structured policy matrix (Table 10) that maps empirical drivers to policy tools, expected effects, implementation mechanisms, while Table 11 provides Strategic framework for macro prudential and fiscal coordination, and we have strengthened the comparative policy discussion (Table 12) to position Saudi Arabia’s framework relative to Malaysia and GCC peers. These revisions enhance the coherence between empirical evidence and actionable policy guidance.

Table 11.

Strategic framework for macro prudential and fiscal coordination.

Table 12.

Cross Country and GCC Comparative policy insights.

Based on the findings, discussion, and results above, we recommend the following practical timelines and benchmarks for policymakers to facilitate the adoption of the recommendations.

Counter Cyclical Capital Buffer: Semi-annual assessment of the credit to GDP gap, with buffer adjustments phased in over one to two quarters to avoid sudden capital shocks.

Liquidity Requirements: Quarterly monitoring of liquidity ratios, with corrective actions implemented within the same quarter if thresholds are breached.

Sectoral Diversification: Annual review of sectoral exposures, with policy adjustments incorporated in the next supervisory cycle.

Fiscal Financial Coordination: Annual joint meetings of SAMA and the Ministry of Finance under the Financial Stability Council (FSC), with contingency planning and stress-test results reviewed each cycle.

These benchmarks provide actionable timelines while maintaining flexibility for macroeconomic developments. The manuscript has been updated to include these suggestions, making the policy recommendations more concrete and operationally implementable. Table 11 below provides a strategic framework for macro prudential and fiscal coordination.

5.4. Comparative Policy Insights (Malaysia vs. Saudi vs. GCC)

The comparison highlights that Saudi Arabia’s framework is evolving toward global best practices but requires greater transparency and public disclosure of stress test outcomes to enhance market confidence [2].

5.5. Broader Policy Implications

Table 12 benchmarks Saudi Arabia’s macroprudential framework against Malaysia and the GCC peer average, allowing an assessment of institutional maturity, coordination mechanisms, and stress-testing practices.

Malaysia represents a mature macroprudential regime characterized by proactive regulation, centralized policy coordination between the central bank and fiscal authorities, publicly disclosed annual stress tests, and relatively high capital buffers (15% to 17%). Systemic risks are primarily driven by domestic credit cycles and market liquidity, reflecting a diversified economic structure.

Saudi Arabia occupies a transitional position. Although its average capital adequacy ratio is relatively high (17% to 18%), systemic risk remains heavily influenced by macroeconomic variables such as GDP growth, oil prices, and public debt. Policy coordination has improved with the establishment of the Financial Stability Council since 2020, but stress test disclosure remains limited. This indicates progress toward an integrated macroprudential framework, while highlighting the need for greater transparency, formalized coordination protocols, and enhanced scenario governance.

GCC peers, on average, exhibit more fragmented regulatory coordination, irregular stress-testing practices, and stronger exposure to real estate and exchange rate risks. While capital buffers remain adequate, institutional alignment and policy integration are comparatively weaker, suggesting vulnerability to cross-border spillovers and synchronized shocks.

The comparative analysis reinforces the paper’s policy conclusions by showing that Saudi Arabia has a solid capital base but must continue strengthening governance structures, transparency, and cross-institutional coordination to reach its best.

- Institutional Strengthening: Establish a permanent Macro Financial Stability Unit within SAMA to integrate stress testing, early-warning indicators, and policy simulation tools.

- Regional Data Sharing: Collaborate with GCC counterparts to create a unified systemic-risk database, enabling cross-border contagion analysis.

- Inclusion of Non-Banking Financial Institutions (NBFIs): Extend MST coverage beyond commercial banks to insurance, fintech, and investment funds.

- Climate and ESG-related Risks: Incorporate energy-transition scenarios in future stress tests as carbon pricing and sustainability mandates evolve under Vision 2030.

- Public–Private Communication: Periodic disclosure of aggregate stress test outcomes can reduce uncertainty and anchor market expectations.

5.6. Limitations and Future Research

While the current model provides a robust quantitative framework, limitations remain. First, the time series (2010–2025) may not fully capture the structural breaks resulting from post-COVID fiscal dynamics or the expansion of financial technology. Second, the lack of granular, loan-level data hinders the modeling of heterogeneous exposures across banks. Future work could incorporate agent-based simulations and macro financial network models [20] to map contagion paths more precisely. Additionally, integrating climate stress variables and digital finance metrics would enhance predictive accuracy and policy relevance.

5.7. Conclusions

In summary, the Saudi financial system demonstrates strong resilience under moderate macroeconomic stress and manageable vulnerability under severe shocks. Macro stress testing emerges as a vital instrument for Saudi policymakers, bridging micro prudential supervision with macroeconomic surveillance. The findings reinforce the need to institutionalize MST as a recurring analytical exercise within SAMA’s Financial Stability Report cycle. By adopting dynamic buffers, diversifying credit exposures, and enhancing transparency, Saudi Arabia can further solidify its position as a regional benchmark for financial stability and a leading example among G20 emerging markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.P.S., N.M.N. and N.A.; methodology, D.P.S., N.M.N. and N.A.; software, N.M.N., D.P.S. and N.A.; validation, D.P.S., N.A. and N.M.N.; formal analysis, D.P.S. and N.A.; investigation, D.P.S. and N.M.N.; resources, D.P.S., N.M.N. and N.A.; data curation, N.M.N. and N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P.S. and N.M.N.; writing—review and editing, N.M.N., D.P.S. and N.A.; visualization, D.P.S.; supervision, D.P.S.; project administration, D.P.S. and N.M.N.; funding acquisition, D.P.S. All authors accept the responsibility for entire content of this manuscript and consent to the submission of this article to the journal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the ongoing research funding program (ORF-CBA-2025-G3-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the article will be made available without any reservation and concerns.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the editors and the reviewers for their constructive suggestions on this article. The authors acknowledge the contributions to the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- SAMA. Annual Financial Stability Report 2025; SAMA: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FSB. Evaluation of Too-Big-to-Fail Reforms; FSB: Basel, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abdou, H.A.; Elamer, A.A.; Abedin, M.Z.; Ibrahim, B.A. The impact of oil and global markets on Saudi stock market predictability: A machine learning approach. Energy Econ. 2024, 132, 107416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, C. Macroprudential frameworks: Experience, prospects, and a way forward. BIS Work Pap. 2018, 49, 754. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, S.; Kose, M.A. Frontiers of Macrofinancial Linkages; BIS Pap.; BIS: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; Voluem 95, pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-92-9259-124-3. (online). [Google Scholar]

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Basel III: Finalising Post-Crisis Reforms; BIS: Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. Financial Sector Assessment Program: Stress Testing Methodology Review; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.; Jobst, A. Systemic Contingent Claims Analysis: Estimating Market-Implied Systemic Risk; IMF Work. Pap.; 13/54; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Laeven, L.; Ratnovski, L.; Tong, H. Bank size, capital, and systemic risk: Some international evidence. J. Bank. Financ. 2016, 69, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Abdel Monem, H.; Garcia Martinez, P. Macroprudential Policy and Financial Stability in the Arab Region; IMF Working Papers; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, M.; Morsy, H. Determinants of inflation in GCC countries. Middle East Dev. J. 2011, 3, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank Negara Malaysia. Malaysia-Wide Stress Test Report 2013–2015; Bank Negara Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016.

- Brunnermeier, M.; Crockett, A.; Goodhart, C.; Persaud, A.; Shin, H. The Fundamental Principles of Financial Regulation; ICMB: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Galati, G.; Moessner, R. Macroprudential policy—A literature review. J. Econ. Surv. 2013, 27, 846–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutairi, A.; Gallali, M. Stress testing in GCC banking systems: Challenges and prospects. Arab. J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 12, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian, T.; Boyarchenko, N.; Giannone, D. Vulnerable growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 1263–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnermeier, M.; Pedersen, L. Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 2201–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, A.; Chen, S.; Ratnovski, L. The dynamics of non-performing loans during banking crises: A new database. IMF Work. Pap. 2019, 272, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Dridi, J. The effects of the global crisis on Islamic and conventional banks: A comparative study. J. Int. Commer. Econ. Policy 2011, 2, 163–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, S.; Caldarelli, G.; May, R.; Roukny, T.; Stiglitz, J. Complexity theory and financial regulation. Science 2016, 351, 818–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Carletti, E. Systemic risk from real estate and macroprudential regulation. Int. J. Banking Account. Financ. 2013, 5, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Ozdaglar, A.; Tahbaz-Salehi, A. Systemic risk and stability in financial networks. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 564–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of England. System-Wide Stress Testing Framework; BoE: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, P.; Miyajima, K.; Santos, A. The Impact of Oil Prices on the Banking System in the GCC; IMF Work. Pap.; WP/16/161; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BIS. Macroprudential Stress Testing Handbook; BIS: Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cihák, M.; Ong, L.L. Of Runes and Sagas: Perspectives on Liquidity Stress Testing Using an Iceland Example; IMF Work. Pap.; WP/10/156; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. Portfolio credit risk. Econ. Policy Rev. 1998, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Schuermann, T.; Smith, L. Forecasting economic and financial variables with VAR models. In Oxford Handbook of Economic Forecasting; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, C. Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica 1980, 48, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbura, M.; Giacomini, R.; Reichlin, L. Large Bayesian VARs. J. Appl. Econom. 2010, 25, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobst, A.A.; Ong, L.L. Stress Testing at the IMF: Principles, Concepts, and Frameworks. In Stress Testing: Concepts, Applications, and Challenges; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBB. Financial Stability Report 2021; Central Bank of Bahrain: Manama, Bahrain, 2021.

- Honaker, J.; King, G. What to do about missing values in time-series cross-section data. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2010, 54, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators Database; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 10 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.