Abstract

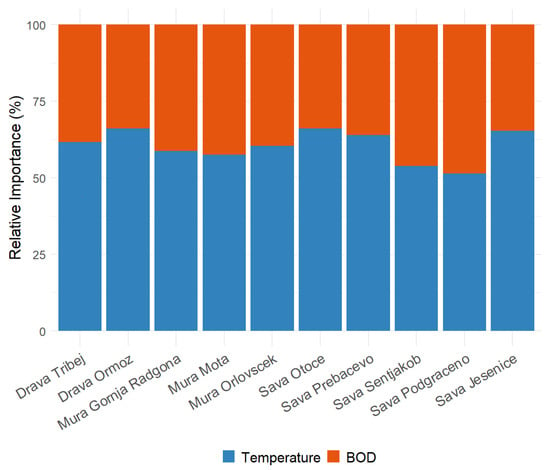

Climate change affects surface water quality parameters, including river quality. This study analyses changes in climate parameters, specifically air temperature and solar radiation, and their impact on river water temperature. It also examines how changes in river water temperature and organic matter load affect oxygen saturation levels, a key indicator of river water quality. Using water quality data, the status as well as temporal and spatial trends of the analysed parameters were assessed for the period between 2007 and 2024 on the three largest Slovenian rivers: the Drava, Mura, and Sava. Relative importance analysis of temperature and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) using the Random Forest machine learning method showed that water temperature in the analysed rivers has an impact ranging from 51% to 66% on predicting oxygen saturation. The selected approach to analysing watercourse quality parameters enables the assessment of the impact of these parameters on river water quality. Based on these results, it will be possible to implement appropriate measures promptly to achieve sustainable river management by establishing a strategy that, under climate change conditions, safeguards water quality and maintains ecosystem protection, ensuring long-term ecological and socio-economic benefits.

1. Introduction

Under the influence of climate change over the past decade, changes in atmospheric temperatures have become evident. Research by Molina et al. [1] and Zscheischler et al. [2] identified this on a global scale, while Folton et al. [3] reached similar conclusions in Mediterranean basins. Forster et al. [4] estimated a global warming of 2.35 °C for 2024. This value represents the warming indicated by the climate index, which is based on the annual or seasonal maximum daily temperature, determined from the global reanalysis dataset prepared by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts for the period 1850–1900. The estimated value for 2024 is 0.05 °C higher than in 2023. The authors [4] also state that the average land temperature in the last 10 years has increased by 0.49 °C compared to the decade 2005–2014 and by 1.90 °C compared to pre-industrial conditions. Climate change is reflected in altered precipitation patterns, which have an impact on the hydraulic and qualitative properties of the rivers [5,6,7,8]. Research into the impact of climate change is being conducted in two directions, (i) the impact on river discharge and consequently on changes in sediment transport and flood safety in riparian areas [5,9], and (ii) the impact on changes in the quality of watercourses [10,11].

Vigiak et al. [12], in their analysis of the anthropogenic impact on the ecological status of European rivers, emphasise that the quality of surface waters is sensitive to increased concentrations of dissolved biodegradable organic substances, whether of natural or anthropogenic origin. With the growing human population and the expected increase in industrial and agricultural production, the amount of pollutants discharged into water bodies is increasing. Water quality and the condition of the entire aquatic ecosystem of rivers may deteriorate further due to increased temperatures in the atmosphere. Negative effects may manifest themselves in the form of eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, oxygen depletion, a reduction in aquatic biodiversity and the contamination of drinking water and groundwater [13,14,15,16]. The European Environment Agency (EEA) published The State of Water 2024 [17], the most comprehensive assessment to date of quality of European groundwater, rivers, lakes, and coastal waters. The study revealed that 63% of surface waters in the EU have poor ecological status, particularly in central and north-west Europe, where intensive agriculture and high population density are present. It is encouraging that water quality has steadily improved since 2010 [17].

Olsson et al. [18], in their analysis of the mutual influence of hydrological changes and air temperature on surface water quality, found that water temperature affects the physical and chemical properties of water. Rising water temperature reduces dissolved oxygen saturation and influences the rates of chemical reactions, biological activity, and decomposition of organic matter. Oxygen concentrations below critical thresholds cause stress, reduced growth and reproduction, or even mortality in organisms. If the inflow of biodegradable organic matter is too high, oxygen is rapidly depleted, leading to hypoxia or even anoxia [13,19]. Therefore, it is important to monitor not only the temperature in river water but also the concentration of dissolved oxygen to determine the impact of climate change on river water quality, as also emphasized by Anh et al. [20]. Recorded climate change leads to increased water temperatures, which alter the physico-chemical and ecological characteristics of aquatic systems, thereby reducing their capacity to maintain biodiversity and meet essential human needs such as drinking water supply, agricultural irrigation, and energy production. As Moatar and Gailhard [21] noted, it is essential to understand how the thermal regime has changed in the past to predict future trends. Rising river temperatures, combined with constant or increased input of organic substances, cause harmful physico-chemical, biochemical, and ecological changes in water bodies. Kaznowska et al. [22] state that achieving sustainable development goals requires recognizing current challenges in water management, including assessing the impacts of climate change and economic activities on water resources. Sustainable management of water resources is a fundamental prerequisite for preserving river ecosystems and ensuring long-term environmental prospects. An integrated approach is necessary, addressing both environmental and economic aspects of water management. Economic sustainability is inextricably linked to environmentally responsible practices, as key sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, energy production, and tourism are critically dependent on the quality of freshwater systems. However, reducing the burden on water ecosystems requires additional financial investment, which increases the cost of products. Therefore, a development strategy that balances ecological conservation with economic viability is necessary to protect river ecosystems and promote positive social outcomes.

Ficklin et al. [23] state that climate change and other human activities are modifying river water temperature globally. A more holistic understanding of river temperature dynamics in an integrated climate–land–hydrology–human framework is urgently needed for sustainable river management and adaptation strategies. Sustainable management of water resources requires a comprehensive approach that integrates economic factors with environmental objectives. The costs of cleaning and maintaining river quality constitute a significant portion of public and private expenditure, yet these measures are essential to prevent long-term negative externalities such as loss of biodiversity, reduced access to drinking water, and diminished economic activities related to tourism and recreation. Investments in modern technologies for cleaning and monitoring aquatic ecosystems should be regarded as strategic, as they yield long-term savings by preventing service interruptions and health costs. In this context, the economy and the environment are inextricably linked, as effective cost management preserves natural resources, strengthens the circular economy, and reduces financial losses resulting from ecosystem degradation. The principles of “polluter pays” and “user pays” ensure that the costs of environmental restoration are aligned with economic incentives, supporting the financial sustainability of investments in water infrastructure. Such a systemic and coordinated approach advances the objectives of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [24], as defined in SDG 6 of the UN-Water 2030 Strategy, and ensures a balance between economic growth and environmental protection.

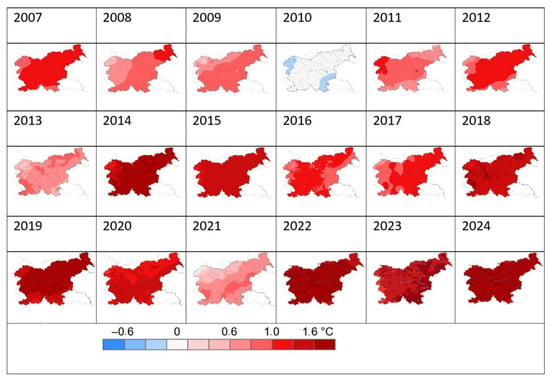

Slovenia is situated in a temperate climatic zone, where Mediterranean, continental, and mountain climate types are present. Temperature measurements indicate climate change, as observed elsewhere in Europe [25]. Average temperatures in Slovenia are rising, with the largest increase occurring in the past 20 years [26]. The timeline from 2007 to 2024 for Slovenia, showing average deviations from the 30-year average air temperature based on measurements from 1981 to 2010, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Deviation of the annual average air temperature from the average for the thirty-year period 1981–2010. Darker red indicates greater warming relative to the long-term average [26].

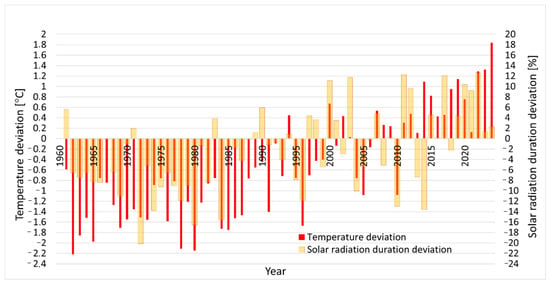

When analysing the influence of heat flows on the energy budget of the lowland Świder River, Łaszewski [27] found that water temperature in the natural environment is mainly influenced by atmospheric temperature and solar radiation. Figure 2 shows the average annual values of these two parameters for the period from 1961 to 2024 for the area of Slovenia [28]. The average annual values of solar radiation do not correspond to the average annual temperatures. Over the past 30 years, both variables have increased, with the rise most pronounced after 2015.

Figure 2.

Deviation of average annual atmospheric temperatures and solar radiation for Slovenia from the reference average value for the period 1991 to 2020 [28].

Due to the varying characteristics of water bodies, climatic conditions, pollution levels in watercourses, and their environmental impact, it is important to analyse the impact of climate change and pollution levels in individual regions. The main aim of the study is to investigate the impact of changes in atmospheric temperature, solar radiation, and the level of organic pollution on water quality in three major Slovenian rivers with different characteristics: (i) a river with a chain of reservoirs for electricity production built before the study period (Drava), (ii) a protected river where anthropogenic influences are limited (Mura), and (iii) a river where hydroelectric power plants were built during the data collection period for the study (Sava).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

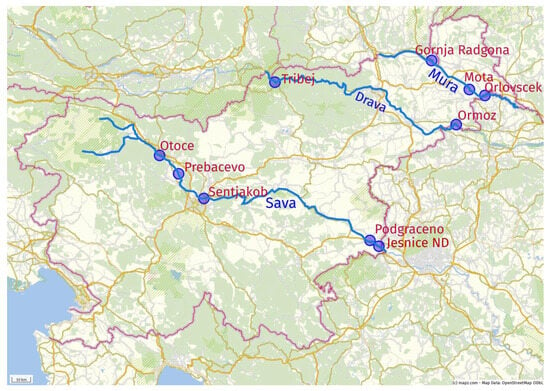

The Slovenian rivers Drava, Sava, and Mura (Figure 3) are significant not only for their length and flow but also for their impact on the natural environment, economy, and cultural landscape of the wider river basin area. The lengths and typical flows of the analysed rivers at the last downstream station in Slovenia are shown in Table 1 [29,30,31]. Data for the measuring stations shown in Figure 3 are presented in Table 2.

Figure 3.

The courses of Drava, Mura, and Sava rivers in Slovenia and the locations of measuring stations where water quality data are obtained (purple line: state border of the Republic of Slovenia; blue line: course of the analysed river).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the analysed rivers [29,30,31].

Table 2.

Measuring stations data [29].

The areas along the Drava, Mura, and Sava rivers are predominantly temperate continental, with local submontane and transitional sub-Mediterranean influences determined by the relief, distance from the sea, and Alpine-Dinaric barrier effects [32,33]. The Drava region represents a transition between continental and Alpine climates, with average January temperatures around −2 °C, July temperatures between 20 °C and 24 °C, and annual precipitation between 1000 and 1300 mm, with pronounced peaks in spring and autumn [33,34]. Prekmurje, along the Mura river, has distinctly Pannonian characteristics, with cold winters (average −1 °C to −3 °C), hot summers (often above 30 °C), and annual precipitation of approximately 800–1000 mm, with the highest amounts in summer [34,35]. Along the Sava in central Slovenia, due to orographic lifting of air masses, annual precipitation is among the highest in the lowlands, with a pronounced autumn peak, and temperatures are milder than in the northeast [34,35]. The upper reaches of the Sava in the Alpine part (Julian Alps, Karavanke) are characterised by an alpine climate: cold, long winters, short summers, average temperatures significantly lower than in the lowlands, and precipitation among the highest in Slovenia (often over 2000 mm/year), with pronounced autumn and early summer peaks [33,34].

The Drava River originates in Italy and flows through Austria. In Slovenia, it passes through the north-eastern part of the country before continuing into Croatia. The total length of the Drava River is 749 km. The Drava River Basin in Slovenia is situated in the Alpine and Prealpine regions, with its lower part situated in the Pannonian Plain. Geologically, the Drava River Basin is highly diverse, as shown on the geological map published by the Geological Survey of Slovenia [36]. The upper part of the basin consists mainly of crystalline and metamorphic rocks, along with carbonate strata. The lower part is dominated by Quaternary gravel deposits, which have been transformed into river terraces. These sediments form extensive gravel-sand aquifers that are hydraulically well connected to the Drava River [37]. A chain of 11 hydroelectric power plants was built on the Drava River in Austria, and 8 hydroelectric power plants were built in Slovenia. All hydroelectric power plants were constructed before the analysed period, so the construction of reservoirs did not affect the values of the analysed parameters [30,31].

The Mura River originates in Austria. In Slovenia, it flows through flat terrain and retains a distinctly natural character. The geological structure of the Mura River area is dominated by silicate Quaternary sediments (gravel, sand, clay). These sediments form highly permeable alluvial aquifers with high porosity, allowing rapid infiltration and horizontal groundwater flow [36]. There are numerous meanders, wetlands, and floodplains along its course. Due to its exceptional natural value, the area is included in the NATURA 2000 network, the European network of protected areas [38].

The Sava River is important in Slovenia for drinking water supply, recreation, and hydroelectric power generation. Its channel is regulated, especially in urban areas. Four hydroelectric power plants were built in the upper reaches of the river, with construction completed in 1987. Four hydroelectric power plants were built in the lower, gentler part of the river; one was completed in 2006, and the others in 2010, 2013, and 2017. All newly built hydroelectric power plants are located within the last 40 km upstream from the border with Croatia, where the river continues to flow. The Sava River Basin is the largest and most hydrologically diverse basin in Slovenia, encompassing Alpine, Pre-Alpine, Karst, and Pannonian landscapes. Owing to its vastness, the geological structure of the Sava River Basin is highly complex. In the upper part, carbonate rocks predominate, enabling rapid underground runoff. In the central part, areas composed of limestone and dolomite alternate with Palaeozoic shales and sandstones. The plains along the river consist of thick deposits of conglomerate, gravel, and sand [36]. Ravbar and Goldscheider [39] state that the hydrogeological diversity, particularly the presence of karst aquifers and shallow alluvial systems, increases the vulnerability of water resources.

2.2. Data

The data used in this study are obtained from the official database of the Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO, https://www.arso.gov.si/en/). ARSO manages the national system for monitoring meteorological, hydrological, climatic, and environmental parameters. The data are publicly available via the online platform [40], where aggregated data can be downloaded. Data with higher temporal resolution or additional parameters can be obtained through a formal request to ARSO. In addition to data collection, ARSO carries out processing, validation, and analysis, including statistical processing, and the preparation of reports and forecasts. This ensures the quality of the data and their interpretation in accordance with international standards for observation and reporting.

Water temperature, BOD and dissolved oxygen saturation data were obtained for selected monitoring stations on the Drava, Mura and Sava rivers for the period 2007–2024. However, during this period, not all parameters were measured systematically at every planned station.

A total of 1495 measurements of the selected parameters were analysed. The length of the series for individual parameters varies at each measuring station and ranges from 54 to 442 measurements. The river water temperature in the analysed cases ranges from 0.1 °C to 27.1 °C. This temperature difference affects the values of oxygen concentration in the saturated state, which range from 14.6 mg O2/L to 8.3 mg O2/L [29]. To capture the influence of water temperature on oxygen concentration in the analyses, the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the water is considered as the degree of oxygen saturation, expressed as a percentage.

2.3. Methods

The measurements of the analysed parameters were conducted by ARSO (Slovenian Environment Agency) in accordance with the relevant standards for the implementation of each parameter. Water temperature, concentration, and dissolved oxygen saturation are measured in the field using multi-parameter meter HACH HQ4000 (Hach Company, 56000 Lindbergh Drive, Loveland, CO 80539, USA). BOD analyses are conducted in the laboratory. Temperature was measured according to the SIST DIN 38404-C4:2000 standard [41], with a measurement uncertainty of 0.3 °C. Oxygen saturation was measured according to the ISO 17289:2014 standard [42], with an uncertainty of 1.5%. BOD values were determined in accordance with the ISO 5815-2:2003 standard [43]. The measurement uncertainty depends on the BOD value: for values from 0.6 to 2.0 mg O2/L, it is 12.64%; from 2.1 to 4.0 mg/L, it is 16.88%; and from 4.1 to 6.0 mg/L, it is 13.76%. The limit of quantification (LOQ) is 0.5 mg O2/L.

2.4. Data Analysis and Processing

The study analysed spatial and temporal trends in river water temperature, concentrations of biodegradable substances, and river water oxygen saturation. Values for water temperature and BOD were determined to indicate the extent of impact on the water quality of the rivers analysed.

The data were processed and analysed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA, version 2408) and the open-source software R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria, version 4.5.1) [44]. These tools were used to determine statistical values and spatial and temporal trends of individual parameters. To account for the uneven timing of measurements, parameters were aggregated into annual mean values for each monitoring station and year, and these averages were used to analyse long-term trends. The temporal unevenness of the data includes varying numbers of measurements between individual months or seasons and occasional interruptions in measurement series. In general, aggregation can mask seasonal variability. However, processing data with uneven measurement distribution over time can introduce uncertainty into seasonal or monthly analyses, as the aggregates mainly reflect the season with the higher measurement value rather than the entire signal. In such cases, annual aggregation serves as a stabilizing procedure that addresses short-term gaps, varying measurement densities, and incomplete series, allowing for interannual comparability.

The temporal trend analysis for each parameter assumes a linear trend. The slopes of the trend lines for each parameter were calculated for each year from 2007 to 2024. In the trend line diagrams, positive values indicate an increase in the value of the analysed parameter over the given period, while negative values indicate a decrease. The slope of the trend line represents the intensity of change in the parameter between the average annual value for the specified year on the abscissa and the average value in 2024.

To assess the influence of temperature and the presence of organic biodegradable pollution on the level of dissolved oxygen saturation in river water, relative influence of parameters was calculated using the Random Forest machine learning algorithm [45]. The target variable was daily dissolved oxygen saturation (Saturation, %), and the predictors were daily water temperature (°C) and BOD (mg O2 L−1). The model was trained separately for each station using daily observations, after removing records with missing values in the target or predictors. Annual aggregation was not used for the Random Forest analysis; it was applied only in the trend analysis. While annual aggregation can smooth seasonal variability, the Random Forest analysis preserved the original daily scale information.

3. Results

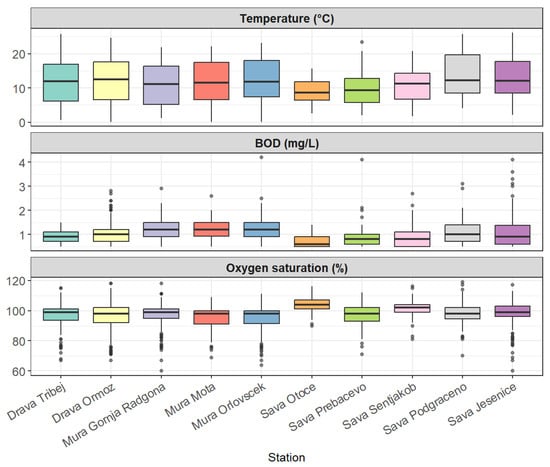

The results of the statistical processing of measured values for the analysed parameters at individual measuring points are shown as box plots in Figure 4. Table 3 shows the number of measurements at individual measuring stations (n), the average measured value ± standard error of the mean (M ± m), the median and interquartile range (Q1–Q3), and the range (min–max).

Figure 4.

Distribution of river water temperature, BOD, and dissolved oxygen saturation at the monitored stations of the three analysed rivers during the period 2007–2024. The horizontal lines represent the median, the box shows the interquartile range, the whiskers indicate the range of non-outlier values, and individual points are outliers.

Table 3.

Values of measured temperatures, BOD and oxygen saturation at measuring stations with n (number measurements), M ± m (mean value ± standard error of the mean), Median (Q1–Q3) (median and interquartile range) and Range (entire data range, min–max). The median in the interval for the data type is indicated.

The range of water temperatures in the Drava River clearly increases downstream (Figure 4). The mean temperatures rise by 1 °C from the Drava Tribej to the Drava Ormož measuring points. BOD values increase from the upstream measuring point at Tribej to the downstream point at Ormož on the Drava River (Figure 4), indicating an additional input of organic load between these locations. A marked increase of 0.15 mg O2/L was noticeable in the maximum recorded BOD value. The average values of oxygen saturation levels differ by approximately 1%, while the range of measured values increases by 2% in both directions (Figure 4). The mean saturation levels are approximately 3% lower than the corresponding medians, indicating occasional below-average oxygen saturation, which result from higher organic load input.

The temperatures measured on the Mura River in Slovenia increased during the period analysed (Figure 4). The mean temperature rose by 0.65 °C from the Gornja Radgona measuring station to Mura Mota, and by a further 0.53 °C to the Mura Orlovšček measuring station. The statistical values of BOD (Figure 4) remained almost unchanged throughout the entire section. Despite the observed increase in the temperature of the Mura River in the direction of flow, a minimal decrease in oxygen saturation from 99% to 98% was recorded.

Analysis of temperature data along the Sava River through Slovenia shows an increase in temperature along the entire section (Figure 4). Average temperatures increase from 8.7 °C at the Sava Otoče station to 12.4 °C at the Sava Podgračeno and Sava Jesenice ND stations. Organic pollution with biodegradable substances increases downstream, leading to a rise in BOD values from 0.65 mg O2/L to 0.95 mg O2/L. Due to external pressures, the oxygen saturation level in the first third of the flow decreases slightly, from an average of 104% to 98%. The lowest quality of the Sava River, as assessed by the average oxygen saturation level, is at the Sava Prebačevo measuring station. This is due to the presence of industrial plants and settlements along the river, which, particularly in the initial period of the analysis, lacked adequate wastewater discharge and necessary treatment [46,47].

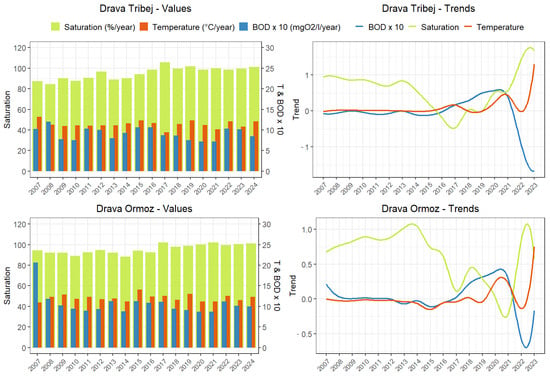

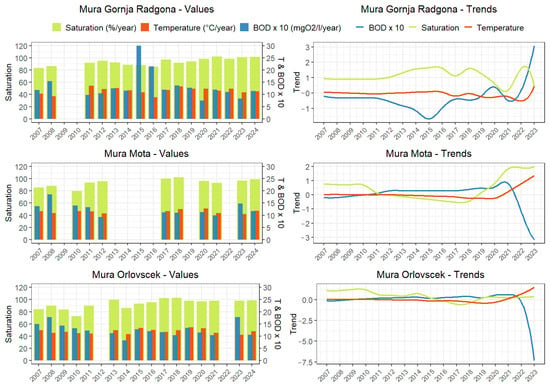

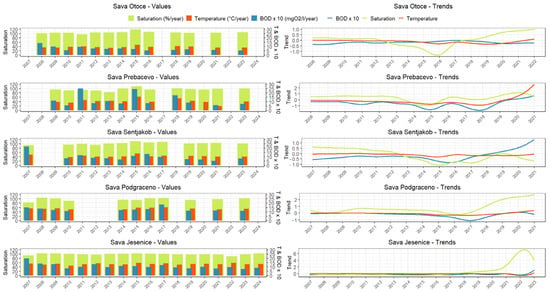

The results of the analysis of temporal changes in selected parameters are presented in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, which show the average annual values of temperature, BOD, and saturation levels, as well as temporal changes in the slopes of trend lines for measuring stations on the Drava (Figure 5), Mura (Figure 6), and Sava (Figure 7) rivers.

Figure 5.

Mean annual values and temporal trends of temperature, BOD, and saturation level at the Drava Tribej and Drava Ormož measuring stations.

Figure 6.

Mean annual values and temporal trends of temperature, BOD, and saturation level at the Mura Gornja Radgona, Mura Mota, and Mura Orlovšček measuring stations.

Figure 7.

Mean annual values and temporal trends of temperature, BOD, and saturation level at the Sava Otoče, Sava Prebačevo, Sava Šentjakob, Sava Podgračeno, and Sava Jesenice ND measuring stations.

Water temperatures at the Drava Tribej measuring station remain relatively stable throughout the analysed period. Average annual temperatures range between 10 and 12 °C. The first year of the period stands out with a high average temperature of 13.17 °C, exceeding all other annual averages. BOD values range from 0.75 to 1.07 mg O2/L throughout the entire analysis period. From 2007 to 2015, there is a slight downward trend in BOD values. The trend then reverses and rises until 2021, before falling again from 2022 onwards. In 2024, a noticeable decrease in BOD values is observed. The oxygen saturation level shows an upward trend from 2007 to 2016, with the rate of increase slowing over time. Between 2017 and 2020, oxygen concentrations decrease, then increase again until the end of the period under review. At the Drava Tribej measuring site, an upward trend in water temperatures and a downward trend in organic matter loading of the Drava River can be observed in the latter part of the observation period, from 2021 onwards. Despite increased water temperatures, lower organic loads are associated with an upward trend in the oxygen saturation level.

The Drava Ormož measuring station recorded average annual temperatures between 10.9 °C and 13 °C. The water temperature in the Drava River reservoirs in Slovenia increases by approximately 0.5 °C. Temperature trends at the Drava Ormož measuring station show no significant changes until 2019. After that year, there is an upward trend in temperatures. Although the highest atmospheric temperatures in the analysed period were recorded in 2024, the highest average annual water temperature at the Drava Ormož measuring station occurred in 2015. The average annual BOD values range from 0.87 mg O2/L in 2020 to 2.06 mg O2/L in 2007. The BOD trend values at the Drava Ormož measuring station are very similar to those at the Drava Tribej measuring station. The year 2024 is notable, as the average annual BOD value at the Drava Ormož measuring station is similar to the average annual value in 2023, unlike at the Drava Tribej measuring station, where a significant drop in BOD values is observed. This results in a lower growth trend in oxygen saturation recorded at the Ormož station. The oxygen saturation level at the Drava Ormož measuring point ranges from 88% to 102%. The lowest oxygen saturation values were recorded in the first half of the analysed period. In the second half, the oxygen saturation improved and remained very close to 100%. The combined negative impact of rising water temperature and BOD on oxygen saturation levels at the Ormož measuring station is evident in 2022, when the slope coefficient of the oxygen saturation trend becomes negative. At both measuring stations on the Drava River, there has been an increasing trend in water temperature since 2019, a decreasing trend in organic matter loading since 2020, and an increasing trend in oxygen saturation levels over the same period.

Figure 6 presents the results of the analysis of the average annual values of water temperature, BOD, and oxygen saturation levels of the Mura River at the Mura Gornja Radgona, Mura Mota, and Mura Orlovšček measuring stations.

At the Mura Gornja Radgona measuring site, the temperature trend does not change significantly during the analysed period and shows a slight downward slope until 2022. In 2024, higher average annual temperatures were recorded, but these did not exceed the values from 2011 and 2018. Average annual BOD values range from 0.75 mg/L to 3.0 mg/L. The BOD trend is downward until 2015. In 2015 and 2016, BOD values almost double, reaching above 2.2 mg O2/L. In 2024, a slight increase in the inflow of organic matter is again observed, with an average annual value of 1.3 mg O2/L, which does not exceed the values typical of watercourses of very good quality. The oxygen saturation level shows an increasing trend throughout the analysed period, but the growth has slowed significantly since 2022.

At the Mura Mota and Mura Orlovšček measuring stations, the characteristics of temperature trends are very similar. The average measured temperature between the Mura Gornja Radgona and Mura Mota stations increased by 0.35 °C over the analysed period. A declining temperature trend at the Mura Mota station persisted until 2020. The oxygen saturation level is mostly below 100%, which is not surprising given the hydrodynamic characteristics of the Mura River. In the first years of the analysis, up to 2011, the BOD value was even lower than 90%. With the falling temperature trend and the rising BOD trend, the oxygen saturation level declined until 2020. Despite the recent rising temperature trend, the trend in oxygen saturation is positive due to a significant reduction in organic matter loading.

At the Mura Orlovšček measuring point, recorded oxygen saturation values are mostly slightly below 100%. Since 2019, there has been a slight increase in the saturation level. BOD values have been on an upward trend for most of the analysed period, mainly due to high values in 2023, when the average annual organic matter load reached 1.8 mg/L, almost equal to the value measured in 2008. The marked decline in the BOD trend in the last year further contributes to the increase in the intensity of the oxygen saturation level trend.

Figure 7 presents the average annual values and time trends of temperature, BOD, and oxygen saturation levels at the Sava River monitoring stations.

A comparison of the direction and intensity of trends at all stations does not reveal significant differences in the characteristics of temporal changes in water temperature at individual measuring points. The temperature trend slope diagrams show negative slopes until 2019 and 2020. The town of Sava Šentjakob stands out, as extremely high temperatures at the beginning of the analysed period result in a decreasing trend that continues until the end of the analysis period. The highest measured average annual temperatures during the analysed period were recorded in 2015 along the entire section of the Sava River in Slovenia, ranging between 12 and 15.5 °C. Both values are related to the upstream measuring stations Sava Otoče and Sava Prebačevo. BOD values at all measuring points show a slight decreasing trend. Analyses of trend values for oxygen saturation levels show a similar pattern throughout the Sava River. The lowest values of the intensity of the oxygen saturation trend were recorded at most stations in 2015, when above-average water temperatures and BOD values between 0.7 and 2.45 mg O2/L were recorded at the same two upstream measuring points. Over the past eight years, an increasing trend in oxygen saturation levels has been observed along most of the Sava River, except at the Sava Šentjakob station, where the trend has been decreasing since 2012 due to discharges from municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants [48].

Analysis of the influence of water temperature and organic load on the oxygen saturation level allows the relative importance of each parameter to be determined. For this purpose, the advanced machine learning method Random Forest [45], included in the R software package [44], was used. The results of the analysis are presented in Figure 8. At all measuring stations, a greater influence of water temperature changes was observed, ranging from 51% to 66%. On the Drava River, with increasing water temperature and BOD downstream (Figure 4), the influence of water temperature increases from 61.5% to 66%. No significant changes in temperature and BOD values are observed along the Mura River (Figure 4). Water temperature has a greater influence, with its importance slightly below 60%. On the Sava River, the relative importance of water temperature decreases along the river, from 66% at the Sava Otoče station to 51% at the Sava Podgračeno station.

Figure 8.

Relative importance of the influence of temperature and BOD on the assessment of oxygen saturation (Random Forest).

4. Discussion

Results of this research shows that the range of measured temperature values in all analysed watercourses increases downstream, most noticeably in the Sava River in the upper two thirds of its flow, where velocities are higher. Given the length of the analysed watercourse section, such responses of river water temperature to climatic conditions are expected and in accordance with findings of Andrews et al. [49]. Furthermore, Zhi et al. [50] investigated the spatial distribution of dissolved oxygen concentration in a cascade river and the mechanisms influencing oxygen concentration values. The authors used a combination of field measurements and numerical modelling. They found that temperature is a key factor determining oxygen dependence. The analysed area is similar to the upper reaches of the Sava River, where comparable hydrodynamic conditions exist, such as cascades that promote additional water re-aeration. Analyses of this study also show a similar pattern of oxygen saturation, with the highest values observed at the Otoče measuring station (Figure 4). It should be noted that this study was also conducted on a river (Sava) with very low organic load. BOD median values ranged from 0.6 mg/L O2 to 1 mg/L O2. The influence of air temperature on water temperature was also investigated just downstream from the Slovenian-Croatian border on the Sava River [51], and the findings were consistent with the findings of this research. Bonacci et al. [51] analysed water temperature data from the Sava River at the Zagreb gauging station and, like our research, encountered data gaps. Only 53 of the 73 years from 1948 to 2020 had complete records. Nevertheless, they emphasized the importance of analysing long-term water temperature changes, as a significant increase in air temperatures has been observed in the region, especially in Zagreb. They found an increasing trend in water temperature over the entire period, with a more pronounced rise after 1988, attributing the main cause to the increase in air temperatures.

In general, river flow, along with temperature, significantly influences the degree of oxygen saturation. This study did not take flow into consideration. Supporting this simplified approach are the findings of Zhi et al. [50], who provided a study of 580 rivers in the USA showing that flow has only a very small effect on the daily dynamics of dissolved oxygen. Deep learning models indicated that the contribution of flow to predicting dissolved oxygen is minimal compared to temperature, which is by far the strongest factor.

Širca and Rajar [52] conclude in their study that average monthly river water temperatures will not change after the construction of the HPP (hydroelectric power plants) chain. In the analysed decade, 2005–2015, the natural increases in average river water temperatures at the beginning of the section were of the same order of magnitude as the potential increases due to reservoirs. These findings are confirmed by the analysis of water temperature measurements, which show that run-of-river reservoirs, where water velocity and retention times do not change significantly, do not significantly impact water temperature. This is consistent with the results of our analyses of water temperature time courses on the Sava River at measuring stations downstream of newly built reservoirs. These are flow-through reservoirs where construction did not result in significant changes in water flow rate.

Analysis of the influence ratio of parameters for individual rivers showed specific characteristics related to the type of watercourse. In watercourses with lower velocities, such as the Drava River, with a chain of hydroelectric power plants, the influence of climatic parameters is greater. In river sections with lower velocities—specifically, those with built reservoirs with lower flow velocities (the Drava River–HPP and the Sava River in the upper sections), as well as the Mura River due to its naturally slow flow—climate parameters had a significant influence on river water temperature. This aligns with the findings of Bonacci et al. [53], who analysed the impact of the Botovo reservoir (Croatia) on the Drava River and the effects of new reservoir construction on water temperature between 1969 and 2021. Authors observed an increase in water temperature, which accelerated in 1982 after the commissioning of the second reservoir. Under conditions of reduced flow rates and longer residence times, water temperature has a stronger influence on oxygen saturation. In the Mura River, where no significant changes in water temperature or organic matter loading were recorded in the relatively short section analysed, no significant changes in oxygen saturation were detected. The recent increasing trend in water temperature, along with the decreasing trend in organic matter loading, is reflected in a greater influence on oxygen saturation levels. The most pronounced reduction in oxygen saturation occurs in the upper Sava River, downstream of the Otoče monitoring site (Figure 4), an area with higher flow velocity and greater exposure to temperature changes. This finding aligns with Chapra et al. [54], who state that higher temperatures affect fast-flowing rivers the most. This aligns with theoretical analyses of the influence of BOD temperature on oxygen saturation, where oxygen depletion due to BOD oxidation accelerates during re-aeration. Most modelling and observational studies provide insight into the factors influencing river oxygen saturation under climate change. Studies by Rajesh and Rehana [55] and Yavuz [56] consistently report that increasing water temperatures have a dominant influence on dissolved oxygen dynamics, often exceeding the effect of BOD. These studies emphasize temperature as the main factor associated with dissolved oxygen decline, except in cases of severe nutrient loading, when organic pollution plays a larger role in dissolved oxygen depletion. We have reached the same conclusions in our research. Under conditions of lower loads of degradable organic matter in watercourses, water temperature has a dominant influence on oxygen saturation. Rajesh and Rehana [55] found that each 1 °C increase in water temperature results in a 2.3% decrease in oxygen saturation. Graham and colleagues [57] emphasize the key role of spatial analysis in assessing dissolved oxygen dynamics under climate change and show that the impact of excessive dissolved oxygen depletion varies considerably between watercourses. The results of dissolved oxygen analysis conducted during global climate change on the Drava, Mura, and Sava rivers confirm the importance of these analyses. Findings on the extent of the impact of water temperature and organic pollution indicate a similar relationship. Taken together, these findings highlight the complexity of the impacts on water’s dissolved oxygen content and the need for robust monitoring and updated strategies to enhance freshwater ecosystems.

The quality status of the analysed rivers Drava, Mura, and Sava is good, with BOD values mostly below 1.5 mg/L O2. Patel and Jariwala [58] analysed how temperature affects dissolved oxygen (DO) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) in a 22 km section of the Tapi River using the QUAL2Kw model. The climatic conditions, with water temperatures between 22 and 34 °C and BOD values between 6 mg/L O2 and 20 mg/L O2, were significantly different from those in the Drava, Mura, and Sava rivers. Such high temperatures had a large impact on BOD values. This example shows the need to be cautious when applying results and conclusions to river water with different temperature and quality conditions.

In quality prediction research, machine learning models have become popular for making predictions. In our study, as we examined the relationship between water temperature, organic load, and oxygen concentration, Liu et al. [59] analysed the impact of climatic conditions on estimating oxygen saturation using various machine learning models, primarily the Random Forest model. They also faced the issue of missing recent measurements. Based on the available data, they found that in regions with significant anthropogenic emissions, models considering only climatic conditions struggled to accurately predict dissolved oxygen. This indicates that, in such cases, it is also necessary to include degradable loads in river water that affect oxygen consumption. This supports the validity of the value analysis approach used in our study. Due to the complexity of interactions among many parameters, machine learning techniques are increasingly used to analyse and predict river water quality. These approaches often face data shortages, especially when using complex models and analysing their interactions [60,61]. Granata et al. [62] state that the consistently robust performance of the models compared to previous studies on dissolved oxygen levels highlights their potential as more effective tools for predicting this essential water quality parameter.

5. Conclusions

Higher average air temperatures and increased solar radiation due to climate change interactively contribute to rising surface water temperatures. These factors, together with dissolved organic matter from both natural and anthropogenic origin, affect oxygen saturation levels, which can serve as a reliable indicator of watercourse quality.

The highest average annual water temperatures were recorded in 2015 and 2019, when sunlight and atmospheric temperatures were above the long-term average. Trend values for all rivers indicate an increase in water temperature, most pronounced after 2022. Water temperatures did not reach the expected extreme values in 2024, which was the year with the highest measured atmospheric temperature in Slovenia.

Spatial analysis shows a consistent downstream increase in water temperature across all rivers, accompanied by a similar trend in BOD values. The most pronounced deterioration in water quality occurs in the Sava River. Temporal trend analysis reveals an overall improvement in water quality, characterized by varying rates of increase in oxygen saturation, despite rising water temperatures. An exception to this pattern is found at the Šentjakob monitoring station on the Sava River, where a negative trend has persisted since 2013.

The results indicate that both water temperature and BOD have similar influences on oxygen saturation levels, with water temperature showing a slightly stronger effect. Along the Drava River, the relative significance of the oxygen concentration increases downstream, coinciding with rising water temperature and BOD values. On the Mura River, where minimal changes in water temperature were recorded, the change in the relative importance of both parameters is very small. On the Sava River, with increasing water temperature and BOD values downstream, the influence of water temperature decreases.

The results of the analyses indicate that predicting the course of oxygen saturation levels in watercourses with varying characteristics is highly uncertain without appropriate analyses. Based on the research findings, it is possible to determine priority actions for preserving and improving watercourse quality and to predict the impact of changes in anthropogenic load on the watercourse. Traditional water management should be updated to include the development and implementation of new strategies to mitigate the negative effects of climate change and increase the resilience of all freshwater ecosystems [63]. The approach presented for analysing river water quality parameters can provide a solid basis for decision-makers and watercourse managers to ensure optimal and sustainable use of river water and riparian areas and to achieve appropriate quality conditions for the population, nature protection and economic activity under climate change conditions. To achieve sustainable water resource quality, it is necessary to optimize the ratio between the costs and effects of measures. Preventive measures, such as cleaning, monitoring, and protection against pollution, are more economically effective in the long term than rehabilitating degraded resources [64]. Adequate planning must combine ecological and economic sustainability, as only the integration of these aspects ensures a stable economy and the preservation of water system quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K. and L.R.; software, L.R.; validation, M.K., L.R. and M.Š.; formal analysis, M.K. and L.R.; investigation, M.K., L.R. and M.Š.; data curation, M.K. and L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and M.Š.; visualization, M.K. and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the research program P2-0180: “Water Science and Technology and Geotechnical Engineering: Tools and Methods for Process Analyses and Simulations and Development of Technologies” that is financially supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Environmental Agency of the Republic of Slovenia (ARSO) for data provision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| ARSO | Slovenian Environment Agency |

References

- Molina, M.O.; Soares, P.M.M.; Lima, M.; Gaspar, T.; Lima, D.; Ramos, A.; Russo, A.; Trigo, R. Updated Insights on Climate Change-Driven Temperature Variability across Historical and Future Periods. Clim. Change 2025, 178, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zscheischler, J.; Raymond, C.; Chen, Y.; Le Grix, N.; Libonati, R.; Rogers, C.D.W.; White, C.J.; Wolski, P. Compound Weather and Climate Events in 2024. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folton, N.; Martin, E.; Arnaud, P.; L’Hermite, P.; Tolsa, M. A 50-Year Analysis of Hydrological Trends and Processes in a Mediterranean Catchment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 2699–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.M.; Smith, C.; Walsh, T.; Lamb, W.F.; Lamboll, R.; Cassou, C.; Hauser, M.; Hausfather, Z.; Lee, J.-Y.; Palmer, M.D.; et al. Indicators of Global Climate Change 2024: Annual Update of Key Indicators of the State of the Climate System and Human Influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 2641–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basim, K.; Al-Saadi, R.; Abdulameer, L.; Al Maimuri, N.; Al-Dujaili, A. Climate Change Impacts on River Hydraulics: A Global Synthesis of Hydrological Shifts, Ecological Consequences, and Adaptive Strategies. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, M.T.H.; Thorslund, J.; Strokal, M.; Hofstra, N.; Flörke, M.; Ehalt Macedo, H.; Nkwasa, A.; Tang, T.; Kaushal, S.S.; Kumar, R.; et al. Global River Water Quality under Climate Change and Hydroclimatic Extremes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacci, O. Factors Affecting Variations in the Hydrological Cycle at Different Temporal and Spatial Scale. Acta Hydrotech. 2023, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacci, O.; Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Roje-Bonacci, T. Comparative Hydrological Analysis at Two Stations on the Boundary River Sotla/Sutla (Slovenia-Croatia). Acta Hydrotech. 2025, 38, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, R.; Hu, X.; Ren, N.; Tian, Y. Natural and Anthropogenic Imprints on Seasonal River Water Quality Trends across China. npj Clean Water 2025, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado-Guerra, D.Y.; Paredes-Arquiola, J.; Pérez-Martín, M.Á.; Corzo-Pérez, G.; Ríos-Rojas, L. Effect of Climate Change on the Water Quality of Mediterranean Rivers and Alternatives to Improve Its Status. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.C.; Bierwagen, B.; Bridgham, S.D.; Carlisle, D.M.; Hawkins, C.P.; Poff, N.L.; Read, J.S.; Rohr, J.R.; Saros, J.E.; Williamson, C.E. Indicators of the Effects of Climate Change on Freshwater Ecosystems. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigiak, O.; Udias, A.; Pistocchi, A.; Zanni, M.; Aloe, A.; Grizzetti, B. Probability Maps of Anthropogenic Impacts Affecting Ecological Status in European Rivers. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.S.; Moatar, F.; Recoura-Massaquant, R.; Chaumot, A.; Zarnetske, J.; Valette, L.; Pinay, G. Hypoxia Is Common in Temperate Headwaters and Driven by Hydrological Extremes. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 109987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.S.U.H.; Wang, Y.Y.L.; Cai, Y.-E.; Wang, Z. Temperature Effects in Single or Combined with Chemicals to the Aquatic Organisms: An Overview of Thermo-Chemical Stress. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, J.; Misra, A.K. Modeling the Impact of Harmful Algal Blooms on Aquatic Life and Human Health. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2025, 140, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyadh, A.; Peleato, N.M. Natural Organic Matter Character in Drinking Water Distribution Systems: A Review of Impacts on Water Quality and Characterization Techniques. Water 2024, 16, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications Office of the European Union. Europe’s State of Water 2024—The Need for Improved Water Resilience; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024.

- Olsson, F.; Mackay, E.B.; Spears, B.M.; Barker, P.; Jones, I.D. Interacting Impacts of Hydrological Changes and Air Temperature Warming on Lake Temperatures Highlight the Potential for Adaptive Management. Ambio 2025, 54, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Srivastava, R.K.; Bhatt, A.K. Battling Air and Water Pollution; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Anh, N.T.; Can, L.D.; Nhan, N.T.; Schmalz, B.; Luu, T. Le Influences of Key Factors on River Water Quality in Urban and Rural Areas: A Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moatar, F.; Gailhard, J. Water Temperature Behaviour in the River Loire since 1976 and 1881. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2006, 338, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaznowska, E.; Wasilewicz, M.; Hejduk, A.; Stelmaszczyk, M.; Hejduk, L. Long-Term Trends and Characteristics of Water Temperature Extremes of a Large Lowland River During the Summer Season from 1920 to 2023—Case Study of the Bug River in Poland, Eastern Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficklin, D.L.; Hannah, D.M.; Wanders, N.; Dugdale, S.J.; England, J.; Klaus, J.; Kelleher, C.; Khamis, K.; Charlton, M.B. Rethinking River Water Temperature in a Changing, Human-Dominated World. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Water. 2030 Strategy; UN-Water: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Twardosz, R.; Walanus, A.; Guzik, I. Warming in Europe: Recent Trends in Annual and Seasonal Temperatures. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2021, 178, 4021–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSO Animation—Deviation of the Annual Mean Air Temperature 1981–2020. 2025. Available online: https://meteo.arso.gov.si/met/sl/climate/current/animacija_temperatura/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Łaszewski, M. Heat Fluxes and River Energy Budget on the Example of Lowland Świder River. Quaest. Geogr. 2015, 34, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSO Time Series for Slovenia. Available online: https://meteo.arso.gov.si/met/sl/climate/current/climate_series/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- ARSO Data of Automated Hydrological Stations. 2025. Available online: http://hmljn.arso.gov.si/vode/podatki/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- DEM Drava River. Available online: https://www.dem.si/sl/v-sozvocju-z-okoljem/reka-drava/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Slovenian Water Agency Drava Region Sector. Available online: https://www.gov.si/drzavni-organi/organi-v-sestavi/direkcija-za-vode/o-direkciji/urad-za-vzdrzevanje-voda/sektor-obmocja-drave/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Ogrin, D. Climate Types in Slovenia. Geogr. Vestn. 1996, 68, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ogrin, D.; Repe, B.; Štaut, L.; Svetlin, D.; Ogrin, M. Climate Classification of Slovenia Based on Data from the Period 1991–2020. Dela 2023, 2023, 5–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSO Thematic Maps: Temperatures and Precipitation; Trends and Deviations. Available online: https://meteo.arso.gov.si/met/sl/climate/maps/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Arnes, O. About Slovenian Climate. Available online: https://ifeelslovenia.splet.arnes.si/o-podnebju/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Geo ZS Geology Map. Available online: https://ogk100.geo-zs.si/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Vengust, A.; Koroša, A.; Urbanc, J.; Mali, N. Development of Groundwater Flow Models for the Integrated Management of the Alluvial Aquifer Systems of Dravsko Polje and Ptujsko Polje, Slovenia. Hydrology 2023, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency Natura. 2000. Available online: https://biodiversity.europa.eu/natura2000/en/natura2000 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Ravbar, N.; Goldscheider, N. Comparative Application of Four Methods of Groundwater Vulnerability Mapping in a Slovene Karst Catchment. Hydrogeol. J. 2009, 17, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSO Meteo. Available online: https://meteo.arso.gov.si/ (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- SIST DIN 38404-4:2000; German Standard Methods for the Examination of Water, Waste Water and Sludge—Physical and Physico-Chemical Parameters (Group C)—Determination of Temperature (C4). Slovenian Institute for Standardization (SIST): Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2000.

- ISO 17289:2014; Water Quality—Determination of Dissolved Oxygen—Optical Sensor Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 5815-2:2003; Water Quality—Determination of Biochemical Oxygen Demand After n Days (BODₙ)—Part 2: Method for Undiluted Samples. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: http://www.r-project.org (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikoš, M.; Muck, P.; Savić, V. The Sava River Channel Changes in Slovenia. Acta Hydrotech. 2015, 28, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, U. Sava White Book: The River Sava—Threats and Restoration Potential; EuroNatur: Radolfzell, Germany; Riverwatch: Wien, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ARSO Monitoring of Watercourses for Discharges from Municipal and Industrial Wastewater Treatment Plants: Report for 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.si/assets/organi-v-sestavi/ARSO/Vode/Stanje-voda/Porocilo-o-ekoloskem-stanju-vodotokov-za-iztoki-iz-cistilnih-naprav-za-leto-2023.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025). (In Slovene)

- Andrews, R.M.; Hayes, D.B.; Zorn, T.G. Multimodel Evaluation of Longitudinal Stream Temperature Gradient and Dominant Influencing Factors in Michigan Streams. River Res. Appl. 2022, 38, 1829–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, W.; Ouyang, W.; Shen, C.; Li, L. Temperature Outweighs Light and Flow as the Predominant Driver of Dissolved Oxygen in US Rivers. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacci, O.; Žaknić-Ćatović, A.; Roje-Bonacci, T. Significant Rise in Sava River Water Temperature in the City of Zagreb Identified across Various Time Scales. Water 2024, 16, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širca, A.; Rajar, R. Thermal Load of the Sava River in Slovenia after Construction of a Chain of Run-of-the-River HPPs. In Proceedings of the IAHR Europe Congress—New Challenges in Hydraulic Researchand Engineering; Aronne, A., Elena, N., Eds.; Research Publishing: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacci, O.; Đurin, B.; Bonacci, T.R.; Bonacci, D. The Influence of Reservoirs on Water Temperature in the Downstream Part of an Open Watercourse: A Case Study at Botovo Station on the Drava River. Water 2022, 14, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapra, S.C.; Camacho, L.A.; McBride, G.B. Impact of Global Warming on Dissolved Oxygen and BOD Assimilative Capacity of the World’s Rivers: Modeling Analysis. Water 2021, 13, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, M.; Rehana, S. Impact of Climate Change on River Water Temperature and Dissolved Oxygen: Indian Riverine Thermal Regimes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavuz, V.S. Impact of Temperature and Flow Rate on Oxygen Dynamics and Water Quality in Major Turkish Rivers. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, D.J.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; Jones, E.R.; Sutanudjaja, E.H.; van Vliet, M.T.H. Climate Change Drives Low Dissolved Oxygen and Increased Hypoxia Rates in Rivers Worldwide. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Jariwala, N. Analyzing the Effect of Temperature on DO and BOD of the Tapi River Using QUAL2Kw Model. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2023, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Ling, J.; Wu, F. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Based Dissolved Oxygen Predictions in the Yellow River Basin: The Role of Diverse Environmental Predictors. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, P.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z. A Coupled Model to Improve River Water Quality Prediction towards Addressing Non-Stationarity and Data Limitation. Water Res. 2024, 248, 120895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, W.; Appling, A.P.; Golden, H.E.; Podgorski, J.; Li, L. Deep Learning for Water Quality. Nat. Water 2024, 2, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, F.; Zhu, S.; Di Nunno, F. Dissolved Oxygen Forecasting in the Mississippi River: Advanced Ensemble Machine Learning Models. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 1537–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, K.; Mi, C.; Magee, M.R.; Carey, C.C. Increasing Exposure to Global Climate Change and Hopes for the Era of Climate Adaptation: An Aquatic Perspective. Ambio 2025, 54, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Wang, W.; Huang, R.; Su, R. A Review of Typical Water Pollution Control and Cost-Benefit Analysis in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1406155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.