Abstract

In the face of accelerating climate change and urbanization, sustainable mobility infrastructure plays a critical role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This article assesses the Sunglider concept—an elevated, solar-powered transport system—through the New European Bauhaus (NEB) Compass, which emphasizes sustainability, inclusion, and esthetic value. Designed by architect Peter Kuczia and collaborators, Sunglider combines photovoltaic energy generation with modular, parametrically designed wooden pylons to form a lightweight, climate-positive mobility solution. The study evaluates the system’s technological feasibility, environmental performance, and urban integration potential, drawing on existing design documentation and simulation-based estimates. While Sunglider demonstrates strong alignment with NEB principles, including zero-emission operation and material circularity, its implementation is challenged by high initial investment, political and planning complexities, and integration into dense urban environments. Mitigation strategies—such as adaptive routing, visual screening, and universal station access—are proposed to address concerns around privacy, esthetics, and accessibility. The article positions Sunglider as a scalable and replicable model for mid-sized European cities, capable of advancing inclusive, carbon-neutral mobility while enhancing the urban experience. It concludes with policy and research recommendations, highlighting the importance of embedding infrastructure innovation within broader ecological and cultural transitions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of Sustainable Urban Mobility in the Climate Crisis

The global climate crisis has intensified the need for sustainable transformations in city systems, particularly in transportation. Urban mobility plays a pivotal role in the broader landscape of climate change mitigation. While cities occupy only 3% of the Earth’s surface, they are responsible for over 70% of global GHG emissions, and transportation represents a significant share of this output [1]. According to the International Energy Agency [2], nearly 25% of energy-related CO2 emissions come from transport, with road traffic being the dominant source.

Car-centric development has not only increased carbon emissions but also exacerbated social inequity, air pollution, and urban sprawl [3]. In response, sustainable urban mobility has emerged as a strategic lever in climate change mitigation. This concept promotes a shift from car-centric infrastructure to more inclusive, efficient, and low-emission alternatives, such as public transit, cycling, walking, and shared mobility services [4,5]. However, the success of this transition hinges not only on modal substitution but also on the development of integrated, appealing, and user-centric infrastructure.

The European Union has placed urban mobility at the heart of its climate strategy through initiatives such as the European Green Deal and the Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy, which aim to reduce emissions by 90% in the transport sector by 2050 [6]. Complementing these is the New European Bauhaus (NEB), a cultural and design movement launched in 2021 to connect sustainability, esthetics, and social inclusion in the built environment [7]. NEB reframes the mobility transition not just as a technological shift, but as a holistic transformation rooted in community well-being, urban beauty, and accessibility.

However, despite numerous initiatives in green infrastructure and sustainable transport, there remains a significant research and design gap in the integration of renewable energy, esthetic urban design, and inclusive access into a single, scalable mobility system. In particular, few mobility concepts have been critically evaluated through the lens of the New European Bauhaus (NEB) framework, which emphasizes the interconnected values of sustainability, esthetics, and inclusion. This paper aims to fill this gap by using the NEB Compass to evaluate the Sunglider concept as a prototype for future urban infrastructure.

1.2. Introduction to the Sunglider Concept: Solar-Powered, Elevated Mobility Solution

Within this context, the Sunglider project, designed by architect Peter Kuczia and the multidisciplinary team, represents a paradigm shift in mobility infrastructure. It proposes a modular, elevated vehicle corridor powered entirely by integrated photovoltaic (PV) technology [8]. Blending architectural innovation with renewable energy and digital technology, the Sunglider concept promotes an environmentally regenerative and culturally embedded form of urban mobility.

A key feature of the Sunglider concept is its intelligent transport system (ITS) compatibility: sensors, adaptive lighting, and digital control systems are embedded into the infrastructure to enable real-time monitoring, efficient traffic regulation, and enhanced safety. Deployed as a highline-style overground transit transportation variant, the Sunglider aims to function as a flexible, autonomous, digitally enabled mobility network.

Visually and structurally, one of the Sunglider’s most distinctive elements is the use of parametrically designed wooden pylons. These support structures are not only engineered for load-bearing performance and material efficiency but are also an architectural statement rooted in sustainability and bio-based innovation. Constructed from laminated timber or cross-laminated timber (CLT), the pylons express a commitment to material circularity, low embodied carbon, and tactile esthetic quality—hallmarks of New European Bauhaus thinking.

The pylon forms are generated via parametric modeling, allowing their geometry to respond dynamically to spatial constraints, wind loads, and local material availability. This approach ensures that each installation can be site-responsive, structurally optimized, and visually integrated into its surrounding environment [9].

While the flagship vision of Sunglider centers on elevated transportation infrastructure, the concept also proposes subsurface implementation in high-density urban zones. In such contexts, the Sunglider could function as a small-footprint, fully electric underground metro, relying on the same solar power and smart control systems as its elevated counterpart. The system would remain modular, lightweight, and designed for climate resilience, flood protection, and energy efficiency—addressing urban constraints while maintaining the project’s environmental and design ethos [10].

The underlying concept of the Sunglider is far more expansive. The system is designed not only to function as a next-generation overground metro—comprising parametrically designed wooden pylons, suspended covered tracks, and intermodal stations—but also to act as a flexible infrastructural platform capable of integrating multiple dimensions of urban life: mobility, energy, logistics, leisure, and culture.

This article presents a conceptual and design-based exploration of the Sunglider, grounded in existing architectural and engineering proposals, supported by energy modeling from published sources. While no physical pilot project has been implemented to date, the system is analyzed through scenario-based data, official design documents, and publicly available simulations, offering a vision-driven yet technically grounded contribution to sustainable urban mobility discourse.

1.3. Objectives of the Paper

The aim of this paper is to critically assess the Sunglider infrastructure concept through the lens of the New European Bauhaus (NEB) Compass, a guiding framework that operationalizes the values of sustainability, inclusiveness, and esthetics/quality of experience in built environment projects [11]. As a pioneering case of integrated transportation and renewable energy infrastructure, Sunglider offers a unique testbed for examining how emerging mobility systems can embody NEB principles in both form and function.

Specifically, this paper aims to:

- Synthesize the publicly available technical and design documentation of the Sunglider concept and identify the key system features relevant to energy performance, spatial footprint, and urban integration.

- Assess the sustainability potential of Sunglider by examining renewable energy integration, material strategy, and land-use efficiency using available simulation-based estimates and feasibility documentation.

- Evaluate the urban integration potential of the concept by identifying opportunities and constraints related to routing logic, station interfaces, multimodal connectivity, and context sensitivity in dense and heritage environments.

- Operationalize the NEB Compass by translating its three core dimensions into explicit qualitative assessment criteria for mobility infrastructure and applying these criteria consistently across the case.

- Derive a structured agenda for future validation, indicating which aspects of the concept require further empirical investigation (e.g., life-cycle assessment, techno-economic modeling, user experience research, and pilot testing).

By framing the analysis within the NEB Compass, the article contributes to ongoing research that seeks to bridge technological innovation with civic values and spatial quality in the transition toward sustainable mobility. While the paper provides a structured conceptual evaluation supported by existing simulations and design sources, it does not claim to replace full engineering validation or field-based evidence, which remain necessary steps for future implementation.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. New European Bauhaus Compass Principles

The New European Bauhaus (NEB) is a cross-disciplinary initiative launched by the European Commission in 2021 as a cultural and design-driven component of the European Green Deal. It aims to reimagine the built environment and everyday life in ways that integrate climate action with social and esthetic transformation. The initiative is grounded in three core values, which are operationalized in the NEB Compass [12]:

- −

- Sustainability: This principle extends beyond carbon neutrality to include circular economy principles, biodiversity conservation, and environmental stewardship. It encourages designs and systems that are energy-efficient, resource-responsible, and resilient to climate risks.

- −

- Esthetics and Quality of Experience: NEB emphasizes the cultural, sensory, and emotional dimensions of design. Aesthetics are not limited to visual appeal but include how spaces feel, sound, and support human well-being. Quality of experience also relates to craftsmanship, heritage, and beauty in innovation.

- −

- Inclusion: Central to the NEB vision is the creation of spaces and systems that are equitable, participatory, and accessible to all. This principle underscores the importance of involving diverse communities in design processes and ensuring that outcomes reflect pluralistic needs, including those of marginalized or vulnerable groups.

These principles serve as a normative compass, enabling policymakers, planners, and innovators to align physical and technological infrastructure with broader humanistic and ecological values.

While the Green Deal sets out policy and regulatory pathways in energy, transport, and construction, the NEB complements this with an emphasis on how these transformations are lived, designed, and experienced.

Within urban innovation policy, the NEB is shaping new standards and funding criteria for spatial development, especially in the areas of:

- −

- Sustainable mobility infrastructure, where esthetic and inclusive design is essential to promote modal shift.

- −

- Urban regeneration and architecture, encouraging adaptive reuse, biophilic design, and low-carbon materials.

- −

- Civic participation, with emphasis on co-design and community-led initiatives.

The NEB has also been integrated into Horizon Europe, the LIFE Program, and Cohesion Policy Funds, embedding its values across EU research, innovation, and regional development strategies [12].

For infrastructure projects like Sunglider, the NEB Compass provides a conceptual tool for evaluation and alignment, enabling assessment beyond technical performance to include cultural relevance, human experience, and societal impact.

2.2. Theoretical Positioning

Sunglider can be interpreted through several established perspectives in mobility and urban transformation research, including the sustainable mobility paradigm, accessibility-oriented planning, and broader debates on multifunctional infrastructure and socio-technical transitions in transport systems [4]. While these approaches provide important analytical tools, they often prioritize either technical performance or spatial policy outcomes. This paper adopts the New European Bauhaus (NEB) Compass as its primary evaluative framework because it explicitly integrates environmental ambition with inclusion and quality of experience, allowing mobility infrastructure to be assessed not only as a transport technology but also as a civic and cultural intervention in the built environment [11]. In this sense, the NEB Compass provides a coherent structure for examining how an emerging system such as Sunglider may contribute to climate-neutral mobility while simultaneously addressing spatial integration, public acceptance, and experiential quality.

2.3. Urban Mobility and Infrastructure Innovation

Over the past decade, urban mobility has undergone a profound shift, driven by the dual pressures of climate change and urban congestion. Central to this transformation is the rise of micromobility and public electromobility as a viable and sustainable alternative to private car usage for short- and medium-distance travel [13]. This shift is supported by advances in smart infrastructure, which leverages real-time data, sensors, modularity, and renewable energy integration to create adaptive and efficient transport systems [14].

Smart infrastructure goes beyond conventional transportation lanes by embedding technology into transport networks—such as intelligent lighting, traffic sensing, digital navigation, and integrated energy systems. These innovations not only improve safety and efficiency but also align with broader smart city goals of resilience, intermodality, and user-centric design [15].

Comparative global initiatives illustrate the potential of infrastructure-led urban transformation grounded in sustainability, esthetics, and civic engagement: High Line (New York City) and Superblocks (Barcelona).

The High Line, New York City: Originally an abandoned elevated railway, the High Line was reimagined as a linear public park, combining ecological restoration with iconic urban design. It has not only catalyzed economic regeneration in adjacent neighborhoods but also reshaped how infrastructure is viewed—as a cultural and social asset, not merely a functional conduit [16]. Its success underscores the importance of adaptive reuse, architectural quality, and place-making in infrastructure innovation.

Superblocks, Barcelona (Superille in Catalan): A groundbreaking urban planning model that reorganizes city blocks to prioritize pedestrians, cyclists, and community life over car traffic. Each superblock restricts through traffic, reclaims public space, and introduces green infrastructure, reducing pollution while fostering social cohesion [17]. Superblocks exemplify a shift from car-centric planning to human-centered urban design, integrating environmental justice with spatial democracy.

These cases highlight how infrastructure can serve as a vehicle for systemic change, embedding ecological values, improving urban livability, and sparking public imagination.

From the perspective of the New European Bauhaus, both the High Line and the Superblocks can be understood as early, implicit manifestations of NEB principles—developed prior to the formalization of the NEB Compass, yet closely aligned with its values. The High Line exemplifies adaptive reuse and esthetic revalorization of infrastructure, while Superblocks foreground inclusion, everyday urban life, and participatory reconfiguration of mobility systems. These precedents provide a comparative lens through which Sunglider can be assessed as a next-generation, explicitly NEB-oriented infrastructure—one that integrates sustainability, aesthetic experience, and inclusion at the level of technological systems rather than solely spatial policy or landscape intervention.

2.4. Technological Framework of Sunglider

2.4.1. Structural Innovation

Sunglider’s modular design employs prefabricated segments mounted on timber pylons spaced 18–24 m apart. These pylons are fabricated from LVL or CLT and are parametric in design—engineered to adapt to local load, wind, and spatial requirements [10].

The Sunglider infrastructure is built upon a modular and lightweight construction paradigm, rejecting the traditional “wagon-paradigm” of heavy rail systems. Instead, it introduces compact, autonomous shuttle units—such as the PANOS (passenger), CARGO (freight), and KATOS (last-mile minibus)—which reduce vehicle weight and increase design flexibility. These 10-meter-long units run on a filigree “Top-Rail” structure that either suspends or supports the vehicles, depending on local needs.

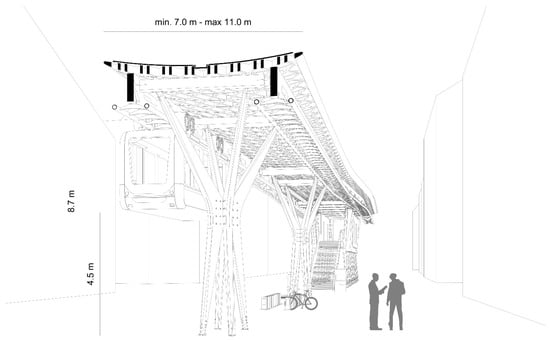

The elevated track system of the Sunglider employs a lightweight, modular construction that minimizes spatial and visual intrusion in dense urban environments (Figure 1). Central to this design are parametrically modeled wooden pylons, fabricated from engineered timber such as laminated veneer lumber (LVL) or cross-laminated timber (CLT). These pylons are spaced at intervals of approximately 20 m and support a dual-track corridor enabling bidirectional movement, elevated at a height of roughly 4.5 m above ground level (measured to the lowest edge of the structure).

Figure 1.

Axonometric section through the Sunglider queue structure, showing the urban context and proportions.

The use of parametric design tools allows each pylon to be geometrically optimized for local load conditions, wind exposure, and spatial constraints, resulting in a structurally efficient and site-responsive system. The wooden supports not only reduce the carbon footprint of the structure compared to conventional steel or concrete but also contribute to a warmer, more tactile esthetic in the urban landscape.

Above, the transit corridor integrates photovoltaic panels directly into the roof envelope, transforming the infrastructure into a solar-generating mobility platform. This dual-purpose design maximizes land use efficiency by combining renewable energy production with zero-emission transport, in line with contemporary goals for climate-neutral and multifunctional urban infrastructure.

2.4.2. Energy and Environmental Performance

Each meter of the elevated structure includes a 6-meter-wide PV canopy, capable of installing approximately 1 MWp of solar capacity per kilometer. For over a 254 km structure, this yields up to 256 MWp of installed solar capacity. The system uses transparent and semi-transparent PV films embedded into the vehicle surfaces and station rooftops, maximizing solar exposure while preserving light access and esthetic quality (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Selected views illustrating the shading simulation of shading on the façades of adjacent buildings; Photovoltaic panels are indicated in green, while the direction of solar radiation is indicated in yellow.

The Sunglider operates as a net-zero transport infrastructure, producing more energy annually than it consumes. Specifically, it generates over 211,000 MWh/year, of which approximately 180,000 MWh are needed for full operation—including all vehicles, stations, and auxiliary systems. The excess 31,000 MWh can be directed toward regional e-mobility needs or stored via grid integration using net-metering schemes.

These estimates are grounded in technical feasibility studies conducted by INTIS (Innovative Transport Systems), the technological partner responsible for system integration and infrastructure development. According to the Sunglider project’s internal white paper, each kilometer of track integrates approximately 1 MWp of photovoltaic capacity, using lightweight solar films and semi-transparent PV panels installed over a 6-meter-wide roof. The annual generation capacity of ~211,000 MWh across a proposed 254 km network was calculated using regional solar irradiation data for Lower Saxony, assuming average module efficiency of 20% and a specific yield of approximately 830 kWh/kWp/year in the Osnabrück region.

While the energy generation model has been validated at the conceptual level using simulation tools and site-specific PV potential analyses, no real-world pilot or full-scale dynamic simulation of vehicle energy demand or grid integration has yet been performed. As of 2025, the Sunglider system remains a high-TRL (Technology Readiness Level 6–7) prototype, combining proven technologies (PV modules, lightweight vehicles, modular construction) into a new systemic application. Further empirical studies—including simulation of vehicle loads, seasonal fluctuations, and net metering behavior—are proposed for future development phases.

The system’s energy architecture supports off-grid operation via distributed generation and real-time load-balancing, enabling resilient performance even during grid outages. The power infrastructure supports dynamic energy sharing among vehicles, stations, and users through smart grid interfaces and app-based energy management.

2.5. Safety and Climate Resilience

The elevated structure provides wind protection, UV shielding, and ambient lighting. Vehicles are monitored in real time and stations include climate control. Unlike at-grade systems, Sunglider avoids flood zones and traffic bottlenecks, offering reliable all-weather operation [18].

The elevated structure and stations are designed for climate protection and user comfort. Covered with solar canopies, the railways offer wind shielding and UV protection, while advanced LED lighting and reflective surfaces enhance visibility and safety. All vehicles and infrastructure elements are embedded with real-time monitoring systems for diagnostics, traffic flow, and predictive maintenance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Approach

This study adopts a qualitative, design-based case study methodology to evaluate the Sunglider concept as an example of next-generation sustainable mobility infrastructure. Given that Sunglider has not yet been implemented as a full-scale pilot project, the research does not aim to produce empirical performance validation through operational data. Instead, it focuses on a structured, framework-driven assessment of technological, spatial, and socio-cultural dimensions, aligned with contemporary sustainability and policy-oriented research practices.

The methodological approach combines three complementary perspectives: (1) conceptual infrastructure analysis, (2) scenario-based performance estimation drawing on existing simulation data, and (3) normative evaluation using the New European Bauhaus (NEB) Compass as an analytical framework. This triangulation enables a systematic assessment of Sunglider’s potential impacts while remaining transparent about current data limitations.

3.2. Case Study Selection: Sunglider

Sunglider was selected as a case study due to its explicit ambition to integrate renewable energy generation, zero-emission mobility, and architectural quality within a single infrastructural system. Unlike conventional transport projects, Sunglider positions infrastructure not merely as a technical asset, but as a cultural and spatial intervention—making it particularly suitable for evaluation through the New European Bauhaus framework.

The case study draws on publicly available design documentation, project descriptions, technical reports, and published feasibility estimates produced by the project’s design and engineering partners. These sources are supplemented by secondary literature on smart infrastructure, sustainable mobility, and energy-positive transport systems.

3.3. Data Sources and Analytical Material

The analysis is based on the following data sources:

- −

- Architectural and infrastructural design documentation, including parametric structural concepts and spatial layouts;

- −

- Energy production and consumption estimates derived from photovoltaic simulation studies and regional solar irradiation data;

- −

- Scenario-based performance assumptions reported in technical white papers and published project descriptions;

- −

- Policy and conceptual documents related to the European Green Deal and the New European Bauhaus.

No primary field measurements or operational transport simulations were conducted, as the Sunglider system remains at a high technology readiness level (TRL 6–7). The study therefore explicitly positions its findings as exploratory and indicative rather than predictive.

3.4. Evaluation Framework: Operationalizing the NEB Compass

The core analytical framework of the study is the New European Bauhaus Compass, which operationalizes sustainability, inclusion, and esthetics/quality of experience as evaluative dimensions for the built environment. Each of these dimensions was translated into a set of qualitative assessment criteria relevant to mobility infrastructure:

- −

- Sustainability: renewable energy integration, emissions reduction, material circularity, and land-use efficiency;

- −

- Inclusion: universal accessibility, spatial reach, mobility equity, and potential social impact;

- −

- Esthetics and quality of experience: spatial experience, architectural integration, sensory qualities, and place-making potential.

The Sunglider concept was systematically examined against these criteria using descriptive analysis and cross-referencing with comparative precedents (e.g., the High Line and Barcelona’s Superblocks). This approach enables consistency across evaluation dimensions and ensures that Section 5 presents structured analytical results rather than purely conceptual framing.

3.5. Methodological Limitations

Several limitations of the adopted methodology must be acknowledged. First, the absence of a realized pilot project restricts the availability of empirical operational data. Second, energy and performance values are based on simulation-based estimates rather than real-time measurements. Third, social inclusion and experiential qualities are assessed qualitatively, drawing on established urban design and mobility literature rather than user surveys.

These limitations are consistent with the early-stage nature of the infrastructure concept and are addressed through transparent reporting and cautious interpretation of results. Future research should complement this qualitative assessment with quantitative simulations, lifecycle assessment (LCA), cost–benefit analysis, and field-based user studies once pilot implementations become available.

4. Urban and Spatial Integration

4.1. Land Use and Urban Impact

The Sunglider concept is designed with minimal intrusion into existing ground-level infrastructure, making it highly adaptable to complex urban and peri-urban environments. Its elevated tracks require support only every 18–24 m, with slender pylons minimizing land consumption. This small footprint allows it to be deployed above existing transport arteries, such as roads, railways, or riverbanks, without the need for extensive demolition or land reallocation.

Sunglider’s linear infrastructure model enables it to follow pre-existing transport corridors or underutilized urban edges. This strategy reduces spatial conflict and allows for harmonious integration into the urban fabric. Where needed, new routes can be established with minimal surface disruption, unlocking opportunities for mobility in low-access or newly developing zones.

This corridor-based strategy aligns with established principles of sustainable mobility and accessibility planning, which emphasize improving network connectivity and service coverage by leveraging existing rights-of-way and underused urban corridors rather than introducing disruptive new infrastructure [4,19]. In this sense, the concept may “unlock opportunities” particularly in areas where conventional rail investment is constrained by cost, space, or governance capacity, by offering an additional layer of public transport connectivity with a limited ground footprint. Moreover, the intention of “harmonious integration” should be understood as context-sensitive alignment with human-scale urban environments—prioritizing multimodal interchange, legibility, and spatial compatibility with everyday urban life rather than maximizing infrastructural dominance [20]. Finally, Sunglider’s modular and scalable deployment logic can be interpreted as a form of targeted network intervention comparable to “urban acupuncture”, where small, strategic mobility investments can catalyze broader system-level improvements and modal shift without requiring immediate city-wide transformation [19].

The ability to “float” above ground makes the Sunglider particularly suited for retrofitting car-dependent landscapes and regenerating suburban sprawl. This also aligns with brownfield revitalization and smart densification strategies, supporting climate-resilient land use transitions. Sunglider functions as a complementary layer within multimodal networks. Its stations interface with bike shares, bus systems, and regional rail. Its scalability makes it suitable for both urban acupuncture and regional backbones [19].

4.2. Connectivity and Urban Morphology

The Sunglider system is envisioned as a complementary layer to existing urban mobility networks. Its stations are designed for integration with major transit hubs, bike-sharing systems, pedestrian networks, and regional rail lines. This ensures intermodality and reduces dependence on fossil-fueled last-mile transport.

The design supports horizontal (intra-urban) and vertical (multi-level) connections, allowing for direct links between ground-level transport and elevated Sunglider routes. This adaptability ensures relevance across both dense urban centers and peri-urban regions.

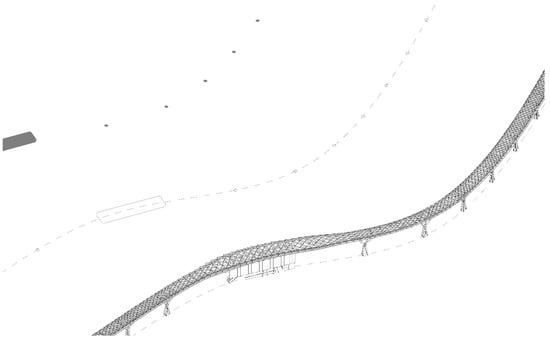

Sunglider operates across multiple scales (Figure 3). On one hand, it can serve as a targeted intervention—an “urban acupuncture” strategy—providing high-efficiency corridors in areas with acute transport needs. On the other, its modular and expandable system allows for regional-scale deployment, creating continuous, high-capacity transit backbones for metropolitan regions.

Figure 3.

Stages of the automated generation of the Sunglider structure; from top to bottom: (i) determination of station locations together with the subdivision of distances between supports, (ii) determination of the cableway route alignment, (iii) generation of the structural system.

This scalability offers cities flexibility: they may begin with limited pilot lines and incrementally expand to city-wide or intercity networks. As such, Sunglider merges bottom-up intervention logic with top-down strategic planning, offering a unique tool for urban innovation.

4.3. Spatial Experience and Esthetics

Riding the Sunglider provides an elevated travel experience, distinct from both street-level transit and enclosed underground systems. Passengers enjoy panoramic views, improved daylight exposure, and a quiet, gliding rhythm that contrasts with the stop-and-go nature of conventional transport modes. This spatial experience contributes to both psychological comfort and perceived urban connectivity.

Moreover, by placing passengers above the noise, congestion, and pollution of street-level mobility, Sunglider enhances the dignity and desirability of public transport—an objective in line with the New European Bauhaus’ emphasis on beauty and well-being.

The infrastructure’s design—inspired by cableway systems—introduces a light and futuristic visual identity to the cityscape. Beyond technical function, Sunglider contributes architecturally to urban character: it is not merely infrastructure but a spatial landmark. Its potential to enhance the cultural and esthetic dimension of mobility mirrors interventions like New York’s High Line or Copenhagen’s Bicycle Snake—elevated paths that double as icons of sustainable urbanism [16,20].

5. Evaluation Through the NEB Compass

The following section presents the results of the qualitative evaluation of the Sunglider concept based on the methodological framework described above.

5.1. Sustainability

The Sunglider system exemplifies sustainability at both the energy systems level and the material-infrastructure level. It promotes biodiversity by reducing ground-level disruption and supports decarbonization goals [11,12].

Emission-Free Mobility and Renewable Energy Integration. As a fully electric and solar-powered infrastructure, Sunglider operates with zero direct CO2 emissions. Each kilometer of track integrates photovoltaic modules generating approximately 1 MWp of capacity, producing surplus energy beyond the system’s operational needs. This not only offsets the energy consumed by vehicles and stations but can also feed energy back to local grids, supporting wider decarbonization efforts.

Material Circularity and Resource Efficiency. Sunglider’s infrastructure uses lightweight, modular construction, designed for easy assembly, disassembly, and repurposing. The use of wood and composite materials in standardized modules facilitates maintenance, reuse, and recycling. Moreover, the elevated design avoids significant ground disturbance, preserving ecological surfaces and reducing construction waste. This aligns with the circular economy principles outlined in the European Green Deal and NEB framework.

In contrast to adaptive reuse projects such as the High Line, which primarily enhance environmental quality through landscape regeneration, and policy-driven mobility reductions exemplified by Barcelona’s Superblocks, Sunglider embeds sustainability directly into its infrastructural metabolism. By combining zero-emission transport with on-site renewable energy generation, it extends the sustainability paradigm from spatial intervention to systemic energy–mobility integration.

5.2. Inclusion

Universal design ensures accessibility for all demographics. Real-time digital tools assist users with disabilities. In peri-urban areas, Sunglider increases mobility equity and economic opportunity.

Accessibility for Diverse Users. Sunglider stations and vehicles are designed according to universal design standards, ensuring step-free access for people with disabilities, older adults, children, and those with limited mobility. Station platforms align seamlessly with vehicle entrances, and vehicle cabins accommodate wheelchairs, strollers, and bicycles, ensuring multimodal and equitable access. Real-time information systems, intuitive interfaces, and integrated mobile applications enhance digital accessibility for all users, including those with cognitive or sensory impairments.

Addressing Socio-Economic and Physical Barriers. Sunglider addresses mobility inequality by offering a low-cost, energy-efficient alternative to private car dependency. In suburban and peri-urban zones—often underserved by public transit—the elevated system offers rapid, predictable connections to employment, education, and public services. Its modular deployment model allows cities to start with limited segments in vulnerable areas, functioning as targeted interventions (“urban acupuncture”) before expanding into denser regions. Furthermore, by reducing travel costs, exposure to air pollution, and traffic injuries, the system contributes to health equity and social well-being.

While Superblocks strongly emphasize participatory governance and neighborhood-level inclusion, and the High Line demonstrates open public accessibility with contested social outcomes, Sunglider addresses inclusion primarily through universal design, mobility equity, and spatial reach. Its potential contribution lies especially in connecting underserved peri-urban areas, positioning inclusion not only as access to space but as access to opportunity.

5.3. Esthetics and Experience

Through its elevated journey, elegant design, and bio-based materials, Sunglider transforms transit into a daily cultural experience—fostering beauty, calm, and connection.

Design as an Emotional and Cultural Experience. Passengers travel above street-level chaos, benefiting from panoramic views, natural lighting, and a calm, gliding rhythm that contrasts with the stress of conventional transit. This elevated spatial experience fosters a positive emotional connection to public infrastructure. The system’s visual transparency, slender form, and quiet operation reflect a design ethos grounded in lightness, clarity, and openness, contributing to citizens’ psychological and environmental comfort.

Aligning Function with Architectural Beauty and Place-Making. By integrating solar technology, smart lighting, and minimalist structural design, Sunglider fuses technical efficiency with visual and architectural integrity. The infrastructure doubles as a linear landmark, enhancing the identity of its host city. In this way, Sunglider is not just a tool for movement, but a place-making strategy.

Comparable to the High Line’s transformation of obsolete infrastructure into an experiential urban landmark, Sunglider reframes mobility infrastructure as a daily cultural experience. However, unlike landscape-based or policy-driven interventions, its esthetic dimension emerges from the integration of technology, lightness, and movement—positioning infrastructure itself as a carrier of beauty and emotional resonance, in line with NEB principles.

6. Critical Discussion

6.1. Strengths: Scalability, Innovation, and Alignment with NEB Values

- −

- Modular scalability for varying urban contexts

- −

- Technological innovation (ITS, PV integration)

- −

- Alignment with NEB values

One of the Sunglider system’s most compelling strengths lies in its scalable and modular design, making it highly adaptable to diverse urban and regional contexts. By employing lightweight, prefabricated structures and flexible deployment strategies, cities can implement the system incrementally—starting with critical corridors or underserved areas and expanding as needed. This modularity also simplifies maintenance and upgrades, reducing long-term operational costs and lifecycle impacts.

Technologically, Sunglider stands at the forefront of infrastructure innovation by integrating autonomous electric vehicles, renewable energy production, and real-time mobility management. Its closed-loop energy system, powered entirely by solar photovoltaics integrated into the infrastructure itself, represents a paradigm shift toward truly energy-self-sufficient public transport. As demonstrated in Section 5.1, the integration of on-site renewable energy differentiates Sunglider from landscape-based interventions such as the High Line, positioning energy-positive performance as a core infrastructural attribute rather than a secondary environmental benefit.

Equally important is Sunglider’s deep resonance with the New European Bauhaus (NEB) values of sustainability, esthetics, and inclusion. The elevated structure enhances urban landscapes rather than degrading them; the seamless, universally accessible design fosters social equity; and its zero-emission operation contributes to climate-neutral urban goals. In this sense, Sunglider is not merely a transportation project but one of the multidimensional responses to ecological, social, and cultural transformation.

6.2. Risks and Implementation Barriers

- −

- Costs: At € 3.14 million/km, Sunglider requires significant upfront investment.

- −

- Implementation and governance complexity. Political Feasibility

- −

- Urban integration challenges: In historic cores, concerns about privacy, heritage impact, and visual intrusion must be mitigated (e.g., with screening, careful alignment, barrier-free access).

Cost and Funding Complexity. One significant barrier is the initial capital investment required. Although Sunglider’s operational costs are relatively low, the upfront infrastructure costs remain substantial. With estimated expenses of approximately €3.14 million per kilometer, including photovoltaic infrastructure, this investment, while lower than traditional metro or tram systems, poses a considerable financial challenge, particularly for smaller municipalities with constrained budgets. Consequently, successful implementation will likely necessitate complex financing structures, such as public–private partnerships, leveraging EU-level funding mechanisms like Horizon Europe or Cohesion Funds, and generating robust, data-driven cost–benefit analyses that clearly articulate long-term advantages in terms of emissions reduction, energy resilience, and socio-economic inclusion.

Implementation Complexity. Sunglider’s sophisticated integration of technological components—including autonomous vehicles, distributed solar energy generation, smart routing, and real-time monitoring—requires high levels of coordination, sophisticated project management, and technical expertise. Cities lacking strong institutional capacity, coherent governance frameworks, or adequate digital infrastructure could struggle to manage the technical complexity associated with implementing Sunglider. Moreover, effective deployment requires strong local collaboration between various municipal departments, technology providers, and energy utilities, further underscoring the complexity of successful execution. The novel and transformative nature of Sunglider’s design may trigger resistance from established urban transportation actors, including traditional public transit providers, automotive interests, and conservative urban planning bodies. Political feasibility hinges on visionary leadership capable of navigating complex stakeholder landscapes, fostering broad public support, and cultivating cross-sectoral alliances between public authorities, private investors, civil society, and citizens themselves. Failure to secure such buy-in could significantly limit the system’s acceptance and ultimately hinder practical implementation.

Challenges of implementation in dense urban contexts: privacy, integration, and accessibility. One immediate concern in dense neighborhoods relates to privacy, as elevated corridors could inadvertently provide passengers views into private residential spaces, thereby compromising privacy and comfort. Effective strategies to mitigate this risk include strategically routing corridors along less sensitive commercial streets, existing transportation arteries, or natural urban features such as rivers or green spaces. Additionally, incorporating vegetated or semi-transparent screening and context-aware elevation adjustments—such as raising the track height or introducing curved alignments using parametric modeling tools—can minimize direct sightlines into private dwellings, preserving residential privacy.

Introducing elevated infrastructure in tightly organized historical districts risks disrupting traditional street profiles and heritage esthetics. Overhead transit lines could cast shadows, obstruct views, or compete visually with significant architectural landmarks. To mitigate these risks, the Sunglider design employs minimalist, slender structural elements, such as the wooden parametrically designed pylons and low-profile photovoltaic roofs, to reduce visual mass. Aligning Sunglider routes with existing transport corridors further maintains urban spatial coherence.

Ensuring universal accessibility presents another critical challenge, particularly for elevated infrastructure requiring vertical mobility solutions to access stations. Stations must comprehensively accommodate diverse user needs—including those of elderly individuals, wheelchair users, families with young children, and temporary mobility impairments. Adhering strictly to barrier-free design standards (e.g., Directive (EU) 2019/882) is imperative, incorporating ramps, elevators, and escalators at each station. Moreover, designing Sunglider stations as integrated components of existing urban infrastructure—such as mixed-use developments or multimodal transit hubs—can reduce spatial disruption, encourage adaptive reuse of urban space, and enhance overall accessibility.

Designing for Contextual Sensitivity. The successful integration of the Sunglider system into dense urban contexts requires more than technical feasibility alone; it demands careful sensitivity to local human-scale experience, privacy concerns, heritage continuity, and inclusive accessibility. Applying context-aware routing, parametric optimization techniques, and inclusive design principles can help Sunglider seamlessly blend into complex urban environments. By addressing privacy, visual coherence, and vertical accessibility proactively, the Sunglider system can realize its promise as a sustainable, esthetically appealing, and socially inclusive mobility solution—truly embodying the New European Bauhaus values. Ultimately, careful attention to these contextual factors will ensure Sunglider’s conceptual robustness translates effectively into tangible and socially accepted urban infrastructure transformations.

6.3. Replicability

The Sunglider system is inherently designed for replication across European cities and metropolitan regions, particularly in medium-sized cities and polycentric urban networks—where traditional metro systems are financially or spatially unfeasible. With EU-level policy support and cross-sector funding, the model can be scaled regionally.

Its modular deployment allows for tailored implementations: in some contexts, it may serve as a feeder system to regional rail, while in others it may function as a primary urban mobility backbone. Its compatibility with solar energy, e-mobility integration, and app-based sharing ecosystems aligns it with EU-wide climate targets and digital transition agendas.

Furthermore, the Sunglider aligns closely with the New European Bauhaus mission to support lighthouse demonstrators that combine climate neutrality, inclusive design, and esthetic transformation. With appropriate piloting, knowledge sharing, and policy support, Sunglider holds strong potential to become a replicable and symbolic model of next-generation European mobility infrastructure.

Given its modular construction and limited ground footprint, Sunglider is particularly well-suited to medium-sized European cities facing spatial and modal bottlenecks but lacking the resources or density to justify heavy rail investments. Urban regions such as Osnabrück, Erfurt, or Regensburg in Germany, Klaipėda in Lithuania, and Plzeň in the Czech Republic offer promising conditions: linear urban corridors, growing populations, and policy commitments to modal shift. These cities exhibit morphological patterns—such as radial or elongated layouts with industrial edges or riverfronts—that can accommodate elevated structures without major expropriation. Moreover, their governance structures are agile enough to coordinate pilot programs in line with EU NEB and Green Deal initiatives. Regional replication may be most feasible through cross-border demonstration clusters, allowing scalability within similar climate, policy, and energy profiles.

7. Conclusions

Sunglider represents an innovative approach to next-generation urban mobility—combining zero-emission transport, renewable energy generation, and context-sensitive design. Evaluated through the New European Bauhaus Compass, the concept aligns with core sustainability values while reimagining the role of infrastructure in the urban realm.

For policymakers, the integration of Sunglider within NEB Lighthouse Demonstrator projects could accelerate the transition toward climate-positive infrastructure. Cities should prioritize adaptable corridors with multimodal interchanges, existing right-of-way opportunities, and renewable energy integration potential. Public–private partnerships and EU co-financing mechanisms could support early-phase deployment.

Urban designers and planners are encouraged to adopt parametric design principles and co-creative processes to ensure spatial, social, and ecological responsiveness. Meanwhile, researchers should focus on filling current knowledge gaps through:

- −

- Dynamic simulations of vehicle energy loads, seasonal performance, and station accessibility.

- −

- Lifecycle and cost–benefit assessments comparing Sunglider to metro, tram, and bike highway systems.

- −

- Field-based studies evaluating public acceptance, visual integration, and policy feasibility.

Overall, Sunglider offers more than a mobility solution—it proposes a paradigm shift in how we conceive infrastructure: not just as a connector of places, but as a regenerative and cultural asset embedded within the evolving European city.

7.1. Implications

The Sunglider model challenges conventional infrastructure to become:

- −

- Multifunctional (mobility + energy generation),

- −

- Intermodally integrated,

- −

- Visually expressive, and

- −

- Climate-adaptive.

It dares to conceive infrastructure not just as technical hardware, but as spatial, cultural, and environmental systems that actively shape urban life. The integration of renewable energy generation into mobility corridors sets a precedent for climate-positive infrastructure.

7.2. Future Research

To strengthen the evidence base and enable implementation-oriented assessment, future research should follow a staged roadmap addressing the key current knowledge gaps. First, seasonal photovoltaic performance modeling should be expanded across different climate zones and urban morphologies, including storage and grid-integration scenarios. Second, life-cycle assessment and techno-economic comparison should be conducted to benchmark Sunglider against established modes (e.g., tram, metro, and bus systems) in terms of embodied emissions, operating impacts, and long-term costs. Third, pilot deployment and operational monitoring are required to generate empirical data on energy demand, system reliability, and passenger flow under real-world conditions. Fourth, user research and participatory governance studies should be implemented to evaluate accessibility needs, acceptance, and inclusion outcomes across diverse demographic groups. Finally, heritage-context integration testing should be undertaken through scenario-based design studies in dense and historic districts to refine routing, station typologies, and privacy/visual mitigation strategies.

To translate Sunglider’s vision into practical reality, further inquiry is needed in several areas:

- −

- Pilot testing in diverse urban contexts—especially in medium-sized and polycentric cities—to evaluate scalability, social acceptance, and local adaptation.

- −

- Techno-economic modeling to quantify lifecycle costs, emissions savings, and return on investment relative to other transit modes.

- −

- Governance frameworks for cross-sector collaboration (energy, mobility, planning) and inclusive public participation.

- −

- Design research exploring spatial esthetics, urban integration, and user experience across different geographies.

By embedding these investigations into EU programs like Horizon Europe, Cohesion Policy, and the New European Bauhaus Lighthouse Demonstrators, Sunglider could evolve from a conceptual innovation into a replicable, symbolic infrastructure of the European green transition.

7.3. Final Thought

In an era marked by ecological urgency and urban transformation, Sunglider illustrates how transport infrastructure can be intentionally designed to support both functional mobility and elevated user experience, potentially reshaping perceptions of daily commuting as more than purely utilitarian. Its realization will depend not only on engineering ingenuity, but also on the collective imagination and courage to reshape the future of infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.O., K.T.-S., and E.G.; methodology, K.T.-S.; software, K.T.-S., and E.G.; validation, K.T.-S., and E.G.; formal analysis, K.T.-S., and E.G.; investigation, K.T.-S.; resources, D.O., and K.T.-S.; data curation, K.T.-S., and E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.O., K.T.-S., and E.G.; writing—review and editing, K.T.-S., and E.G.; visualization, E.G.; supervision, K.T.-S.; project administration, K.T.-S.; funding acquisition, D.O., K.T.-S., and E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2022. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/wcr/2022/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- International Energy Agency IEA. Transport. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- WHO. Sustainable Transport for Health. World Health Organization 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-ECH-AQH-2021.6 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Banister, D. The sustainable mobility paradigm. Transp. Policy 2008, 15, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. The End of Automobile Dependence; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy. COM/2020/789 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=COM:2020:789:FIN (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- European Commission. The New European Bauhaus: Beautiful, Sustainable, Together 2021. Available online: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Design Award Agency. Sunglider—Smart Überground Metro Designed by Peter Kuczia, 2023. Available online: https://www.designawardagency.com/post/sunglider-smart-uberground-metro-designed-by-peter-kuczia-sunglider (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Muse International. Charting the Future with Sunglider 2023. Available online: https://muse.international/index/charting-the-future-with-sunglider-smart-uberground-metro/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Kuczia, P.; Sunglider. Nachhaltige Mobilität; Lorenz, D., Staiger, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 647–660. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The New European Bauhaus Compass 2022. Available online: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/system/files/2023-01/NEB_Compass_V_4.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- European Commission. New European Bauhaus Progress Report 2022. Available online: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/about/progress-report_en (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A. Shared Micromobility Policy Toolkit; UC Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Papa, E.; Ferreira, A. Sustainable Accessibility and the Implementation of Automated Vehicles: Identifying Critical Decisions. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F.; Ratti, C. The impact of autonomous vehicles on cities: A review. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 25, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, C.; Rosa, B. Deconstructing the High Line; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, S. Superblocks for the design of new cities. In Designing Sustainable Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Behling, S. Solar Architecture and Industrial Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, L. Planning the Mobile Metropolis: Transport for People, Places and the Planet; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.