Abstract

Climate change has become the most severe challenge among current global crises, with harsh environmental conditions profoundly impacting inclusive green growth. This study employs data envelopment analysis (DEA) to measure the levels of inclusive green growth in 280 Chinese cities from 2010 to 2022, utilizing a difference-in-differences (DID) model to examine the channels and spatial effects of the pilot policy for the construction of climate-resilient cities (CCRC) on inclusive green growth. The findings reveal that CCRC significantly promotes inclusive green growth. In addition, CCRC drives inclusive green growth through incentivizing technological innovation, with regional economic agglomeration and public environmental participation exerting positive moderating effects. CCRC also generates positive spatial spillover effects on the inclusive green growth of neighboring cities.

1. Introduction

In the context of global climate change, resource scarcity, and social inequality, the necessity for sustainable development has become increasingly evident [1]. Inclusive green growth is broadly acknowledged as a core principle of safeguarding sustainability and has become a key indicator for gauging national development progress [2]. In 2012, the World Bank introduced the concept of “inclusive green growth”, defining it as a new development philosophy emphasizing economic growth, ecological sustainability, social inclusion, and coordination. Subsequently, countries actively pursued related explorations [3]. Developed economies such as the European Union integrated inclusive green growth with environmental controls, social benefits, and technological innovation, balancing ecological shifts and social equity; emerging economies, on the other hand, have prioritized balancing resource usage, environmental regulation, and social inclusiveness [4,5,6]. As the world’s largest energy consumer, China faces acute pressure to coordinate economic development with climate governance. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China shows that the nation’s per capita GDP soared from USD 156 in 1978 to USD 13,445 in 2024, both at current year exchange rates. However, this extensive growth model has also caused severe environmental degradation. Over-exploitation and inefficiency of traditional energy sources; massive emissions of wastewater, gas, and solid waste; and social disparities have greatly exacerbated structural contradictions.

To address the pressing challenges, climate-resilient cities have emerged as a critical development paradigm. As early as 1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) introduced the core concept of “climate change adaptation”, laying a vital theoretical foundation for a series of following actions [7]. The Rotterdam Climate Initiative (RCI), which systematically integrated climate risk responses into urban spatial planning, stands as an early landmark case [8]. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development identifies building inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities as a key objective [9]. To actively practice these goals, China’s constituent departments of the State Council launched the pilot project for the construction of climate-resilient cities (CCRC) across 28 regions nationwide in 2017. This initiative, tailored to local conditions and supported by expert deliberation, aims to integrate climate change as a critical factor in urban planning. It seeks to explore locally relevant models for managing climate adaptation in cities, enhancing urban resilience to achieve sustainable development.

This study adopts data envelopment analysis (DEA) to measure inclusive green growth levels, with panel data covering 280 Chinese cities over the period 2010–2022. By treating CCRC as a quasi-natural experiment and integrating a difference-in-differences (DID) model, it examines the impact of climate governance actions on inclusive green growth and its underlying mechanisms. The analysis specifically addresses the following questions: First, does CCRC promote inclusive green growth? Second, what are the mechanisms through which CCRC influences inclusive green growth? Are spillover effects present? Third, does CCRC exhibit heterogeneous effects? By addressing these questions, this study not only evaluates the effectiveness of establishing climate-resilient cities in the Chinese context but also offers an insightful approach for synergistically advancing global climate adaptation and inclusive growth.

2. Literature Review

A review of the relevant literature reveals that current research on pilot policies for CCRC primarily focuses on implementation outcomes, existing challenges, and future strategies. Fu et al. (2020) noted that while CCRC has achieved certain successes overall, it still faces numerous challenges [10]. Kou et al. (2023) observed that since CCRC’s inception, cities have actively pursued tailored explorations, achieving positive progress in promoting climate adaptation concepts and establishing operational workflows [11]. On the prospects of CCRC, researchers propose that fulfilling citizens’ aspirations for a better life should be people-centered [12]. Formulating urban resilience strategies and establishing regional experience-sharing platforms are also considered as critical directions [13].

In addition, empirical tests have been conducted on policy effectiveness. For instance, Zhang, Z. et al. (2024) and Liu, W. et al. (2025) employed the DID model to examine how pilot policies influence urban resilience [14,15]. By integrating mechanism and spatial effect analyses, they assessed policy outcomes from multiple perspectives [14,15]. Yu et al. (2025) focused on the impacts of CCRC on urban sustainability and its underlying mechanisms, conducting empirical analysis using panel data from 269 prefecture-level cities in China from 2011 to 2020 [16]. Zhang, J. et al. (2025) demonstrated that pilot policies reduce carbon emissions by enhancing green technological innovation, reducing energy consumption intensity, and increasing public climate awareness [17]. In addition, CCRC’s enhancement effects on corporate resilience, its supply chain spillover effects, and its positive incentives for green innovation were explored, with suggestions on building supply chain resilience and supporting green innovation [18,19]. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2025) employed a DID model to assess the impact of CCRC on corporate greenwashing, finding that climate governance actions significantly reduced such practices [20]. Meanwhile, Liu, Y. et al. (2025) utilized a dual machine learning (DML) approach to elucidate CCRC’s influence on green development efficiency, suggesting climate resilience and green technological innovation capabilities are the crucial channels [21].

Regarding inclusive green growth, existing research primarily focuses on three aspects: conceptual definition, measurement methods, and influencing factors. In terms of conceptual definition, international studies mainly draw upon perspectives from development economics and welfare economics. For instance, Spratt and Griffithjones (2013) argue that the core of inclusive green growth lies in achieving balanced development socially, economically, and environmentally [22]. Bouma and Berkhout (2015) further contend that inclusive green growth must not only balance green development, inclusiveness, and economic growth, but also enhance the welfare of both present and future generations [23]. Rauniyar et al. (2010) approach the topic from the perspective of social equity, highlighting that equal opportunities characterize the essence of inclusive green growth [24]. Wang, F. et al. (2022) define inclusive green growth as China’s sustainable development model for achieving economic expansion, social justice, and ecological conservation [25]. Li, H. and Dong (2021) further elaborate that inclusive green growth encompasses multiple dimensions, including innovation, coordination, greening, and sharing [26]. Ma et al. (2024) argue that inclusive green growth should also encompass the symbiotic coordination of greening production and consumption with public welfare [27].

Accordingly, the evaluation framework has been established for measurement. Zhou and Wu (2018) employed the fixed-base range method to measure inclusive green growth across four dimensions [28]. Aminata et al. (2022) focused on economic growth and social equity for design, further calculating the inclusive green growth levels across 34 Indonesian provinces [29]. Ofori et al. (2023) and Zhang, T. et al. (2023) completed the calculation of inclusive green growth indices using principal component analysis (PCA) and a combined subjective–objective weighting method [30,31]. Additionally, DEA has been applied for measuring inclusive green growth. For instance, both Ren et al. (2022) and Wu et al. (2024) utilized the slack-based measure (SBM) to assess inclusive green growth [32,33]. Peng et al. (2025) integrated economic, social, and environmental indicators to construct an efficiency evaluation framework incorporating undesirable outputs, adopting a global super-efficiency Energy-Based Model to measure inclusive green levels [34].

Regarding the influencing factors of inclusive green growth, perspectives such as fintech [35], digital finance [36], the digital economy [37], and urbanization [38] have been covered in the current literature. Among these, Xie et al. (2025) and Ai et al. (2025) showed that low-carbon city pilot policies boost inclusive green growth effectively [39,40]. Wang, Q. et al. (2024) empirically examined the positive impact of new quality productivity on inclusive green growth, with economic agglomeration and technological innovation serving as key channels [41]. Zhou et al. (2024) delved into how industrial intelligence affects inclusive green growth based on China’s urban industrial robot applications [42]. Wang, L. et al. (2020) examined whether environmental regulations can enhance the “green content”, revealing a U-shaped relationship between environmental regulations and carbon productivity [43].

In summary, the existing literature provides inspirations for this study, yet further exploration remains warranted. Compared to prior work, this paper’s potential contributions are as follows: First, by constructing an indicator system for inclusive green growth, it evaluates the policy effects of CCRC on inclusive green growth across temporal and spatial dimensions, thereby supplementing micro-level evidence for climate governance policy assessments. Second, drawing upon theories of sustainable development and inclusive growth, this study reveals the direct and indirect effects through which the pilot policy for CCRC promotes inclusive green growth. It demonstrates synergistic pathways formed by technological innovation effects and factor allocation effects, offering valuable insights for future research.

3. Policy Background and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Policy Evolution

3.1.1. The Evolution of International Climate Policy

Countries have forged distinctive paths in the evolution of their climate policies. This section focuses on the developmental trajectories and characteristics of climate policies in the United States, South Korea, and the United Kingdom.

U.S. climate policy exhibits a “partisan-driven, fluctuating” pattern. During the 1990s and 2000s, the U.S. made commitments but failed to implement substantive measures. While Obama tied actions to energy strategies and promoted clean energy subsidies, Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement during both terms and relaxed fossil fuel regulations. However, the Biden administration has re-engaged in cooperation, supporting clean industries. This policy oscillation fundamentally stems from the conflict between short-term interests and long-term transformation. Both parties have aligned themselves with fossil fuel and clean energy interests, respectively, leading to hesitant corporate investment, fragmented action at the state level between “red states” and “blue states,” and persistent avoidance of international climate financing responsibilities.

South Korea pursued a gradual approach driven by economic transformation. From 1998 to 2008, it transitioned to actively assessing climate impact, introducing national strategies; it then relaxed carbon trading to build manufacturing competitiveness; and after 2017, it shifted to proactive measures, legislating a target and many initiatives. South Korea’s policies aligned with the rhythm of transformation: early compromises with energy-intensive manufacturing gave way to leveraging carbon neutrality to capture green industrial chain shares while reducing energy dependence on foreign sources.

A legislation-driven governance framework was established systematically in the UK. It began in 1988, introducing the foundational concept of a “low-carbon economy” over a few decades. The carbon budgeting system started from The 2008 Climate Change Act, which legislated an upgraded target towards carbon neutrality. Post-Brexit, an independent carbon trading system has been launched, driving international cooperation using high carbon prices. Its core approach lies in reducing transition risks through institutional certainty, legally locking in targets to achieve synergies between emissions reduction and economic growth, positioning it as a global pioneer in carbon neutrality legislation.

3.1.2. The Evolution of China’s Climate Policy

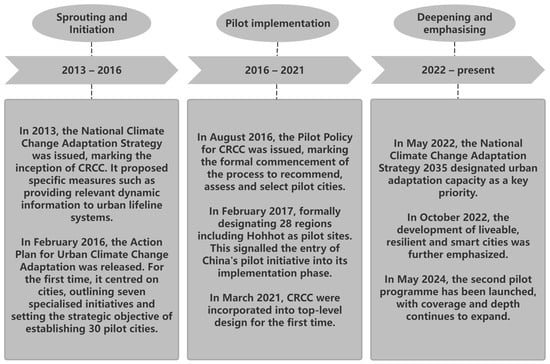

China has progressively established a multi-tiered climate adaptation policy framework, forming a stepwise governance model of “top-level design—pilot exploration—national rollout.” The evolutionary trajectory is illustrated in Figure 1. From 2013 to 2016, China successively introduced specialized national strategies to incorporate climate change factors into urban infrastructure planning, completing the establishment of a top-level policy framework. From 2016 to 2021, action plans and pilot programs at the city level were released to advance policy implementation from planning to practice. Pilot cities were selected across diverse climatic, geographic, and developmental contexts to explore differentiated governance pathways. From 2022 to present, enhancing urban adaptation capacity has been prioritized as a key task, with a focus on building “resilient cities.” Drawing on the experience from the first batch of pilot cities, the second round of pilot applications has been launched, continuously expanding the breadth of policy coverage and the depth of implementation to provide institutional and practical support for building climate resilience in cities.

Figure 1.

Policy evolution in China’s climate-adaptive urban development.

3.1.3. Typical Pilot City Construction Practice Cases

This study examines three pilot cities, namely Yinchuan, Lishui, and Shenzhen, all of which exhibit diversified climatic conditions and developmental stages. By analyzing their practical initiatives, it provides validation for theoretical analysis, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Typical pilot cities and their measures.

3.2. Stylized Facts

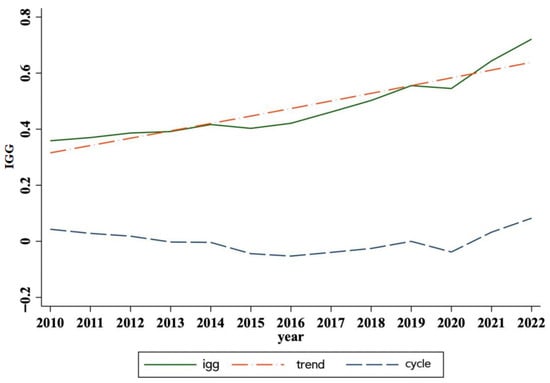

The Hodrick–Prescott Filter (HP Filter) is a commonly used time-series decomposition method. Its core principle involves separating the long-term trend component from the short-term volatility component within a time-series, thereby clearly identifying the core evolutionary patterns and disturbance of the data. To provide a more intuitive analysis of the development trajectory of inclusive green growth in urban economies, this paper employs the Hodrick–Prescott (HP) Filter to process the inclusive green growth rates of 280 cities from 2010 to 2022. A time-series-filtered chart is presented in Figure 2. Among these, “IGG” represents inclusive green growth efficiency. The higher the IGG, the better the cities perform environmentally, economically, and socially. In 2010, IGG across cities stood at just 0.38, reflecting the low level of such synergy among the three under the crude development at that time. Prior to the pilot policy for CCRC in 2017, it steadily climbed to 0.45, showing growth but at a moderate pace. Following policy implementation, growth significantly accelerated. By 2022, the average IGG rose above 0.75, representing a 66.7% increase compared to pre-policy levels. HP filter decomposition revealed that the “trend” curve reflected the long-term trajectory, rising steadily from 0.38 in 2010 to over 0.75 in 2022, confirming the sustained driving force of CRCC initiatives. The “cycle” curve captured cyclical fluctuations, with its relative position to zero indicating deviations due to short-term factors: from 2010 to 2016, the curve remained largely below zero, constrained by crude development and insufficient climate resilience, keeping IGG values below their long-term potentials. From 2016 to 2019, it fluctuated near zero. Following the launch of CCRC in 2017, localized transformation gains offset short-term disruptions, allowing growth to revert. Between 2019 and 2022, the curve rose from −0.01 to 0.05. Policy effects and technological innovation transformed disruptions into growth, sustaining rising IGG values.

Figure 2.

HP filter analysis.

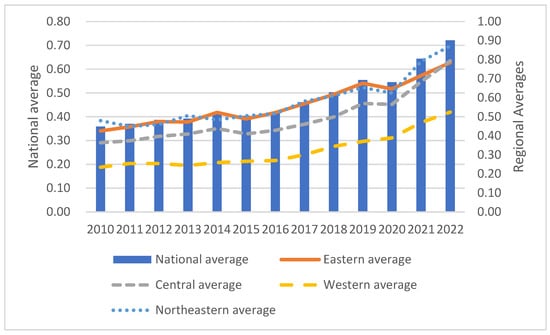

This paper also charts the evolution of average inclusive green growth levels across China’s sub-regional cities from 2010 to 2022. As shown in Figure 3, the levels of inclusive green growth across the nation and its eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions all exhibit long-term upward trends: the eastern region maintains a sustained lead with gradual increases; the central region grows steadily with accelerated momentum in later stages; the western region shows initial flatness followed by rapid growth after 2020; and the northeastern region experiences fluctuations but overall upward movement. This pattern stems from multiple factors: the east leads due to its solid economic foundation, rapid industrial upgrading, and factor concentration; the central region balances green transformation with industrial relocation while accelerating through transportation hub development; the west initially lags due to infrastructure constraints but accelerates growth with the launch of the Western Development Strategy and ecological compensation policies; and the northeast experiences fluctuations due to the difficulty in transforming heavy industries but has recently risen through revitalization policies for old industrial bases.

Figure 3.

Trends of inclusive green growth averages by subregion in China, 2010–2022.

3.3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

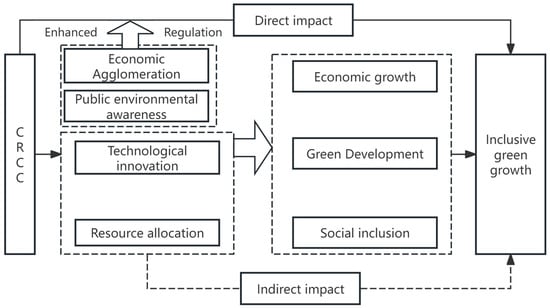

The theory of sustainable development underscores the evolution of economic, social, and ecological systems, suggesting that the developmental rights of both present and future generations should be balanced. This provides core theoretical support for the direct link between CCRC and inclusive green growth. As a systematic practice for addressing climate change, CCRC creates foundations for inclusive green growth by optimizing the synergistic efficiency of urban economic, ecological, and social systems. Economically, climate-resilient infrastructure mitigates the impact of climate risks on production, steering resources toward low-carbon, high-efficiency sectors. Ecologically, the restoration of urban ecology brought by CCRC not only enhances ecosystems’ regulation capacity but also activates the economic value of ecological resources, solidifying the foundation for green growth. At the social level, CCRC emphasizes equitable distribution of public services and development opportunities, alleviating disparities among different groups and regions. The synergistic interaction among the three dimensions positions CCRC as a pivotal link connecting ecological conservation, economic growth, and social equity, ultimately achieving coordinated enhancement of urban economic inclusiveness and green attributes. In summary, this paper proposes the following research Hypothesis 1:

H1:

CCRC promotes inclusive green growth.

The theory of green growth asserts that technological innovation is the core driving green economic growth, and CCRC provides the policy incentive for green technological innovation. China’s Action Plan for Urban Climate Change Adaptation explicitly calls for “developing and promoting key adaptation technologies”, compelling cities to increase R&D investment in low-carbon technologies, disaster monitoring, early warning systems, and ecological restoration techniques. Such innovations not only mitigate economic losses from climate disasters but also promote production efficiency and optimize resource allocation. This directly reduces environmental costs per unit of output, aligning with the green attributes of inclusive green growth. Simultaneously, the application of technological innovations creates employment opportunities for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and vulnerable groups, promoting inclusive sharing of economic growth outcomes. This aligns with the principle of equal opportunities inherent in inclusive growth theory.

Moreover, balanced resource allocation has been emphasized. CCRC optimizes factor allocation, effectively reducing resource misallocation and safeguarding the equity of inclusive green growth. CCRC imposes stricter standards on high-energy-consuming and high-emission industries, compelling their transformation or exit. Accordingly, resource reallocation will move towards green, high-efficiency domains. This process not only optimizes resource allocation among industries and reduces resource misallocation caused by structural imbalances but also boosts employment through the expansion of green industries. Consequently, it narrows wealth gaps and enhances the inclusiveness of economic growth. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes research Hypothesis 2:

H2:

CCRC promotes inclusive green growth by enhancing technological innovation and optimizing resource allocation.

Economic agglomeration refers to the concentrated development pattern of economic activities within specific regions, serving as a key indicator of high-efficiency economic operations. The theories of spatial economics suggest that economic agglomeration can act as a powerful catalyst, enhancing the effectiveness of CCRC in promoting inclusive green growth. Through positive externalities and spillover effects such as technology diffusion, economies of scale, and factor reallocation, economic agglomeration enables optimal resource allocation, leverages external economies, and enhances innovation capacity. Consequently, cities with higher levels of economic agglomeration possess stronger economic strength and innovation capabilities, allowing them to invest more resources in climate-resilient infrastructure development and related technological R&D. This helps cities reduce environmental pressures while achieving economic growth, thereby advancing inclusive green growth in urban economies.

Furthermore, public environmental awareness, as an informal environmental regulatory mechanism, positively modulates the impact of CCRC on inclusive green growth. From the perspective of producers and based on stakeholder and signaling theories, environmental information disclosure reinforces the positive driving force of “economic incentives,” prompting green innovation and advancing green economic growth in cities. At the government and corporate level, heightened public environmental awareness prompts governments to adopt stricter environmental regulations and encourages enterprises to pursue more proactive green development strategies. This increases investment in CCRC, thereby strengthening the impetus for inclusive green growth. From a societal perspective, heightened public environmental awareness enhances societal recognition and acceptance of green development, driving increased green economic activities such as green consumption and investment, which in turn promotes inclusive green growth. In summary, this paper proposes Hypothesis 3:

H3:

Economic agglomeration and public environmental awareness exert a positive moderating effect on the relationship between CCRC and inclusive green growth.

In summary, the theoretical mechanism diagram for this paper is illustrated as shown in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Theoretical framework of how CCRC impacts inclusive green growth.

4. Research Design

4.1. Empirical Setting

- (1)

- Baseline model

As a quasi-natural experiment method, the DID model effectively controls potential confounding factors by capturing the net policy effect through comparing time-series changes between treatment and control groups. It is widely applied in policy impact evaluations. Therefore, this study employs the DID model to identify the impact of CCRC on inclusive green growth. A two-way fixed effects model is utilized to control for city and time effects, while robust standard errors address heteroskedasticity. The benchmark model is constructed as follows:

In the above equation, i denotes a city, t denotes a year, and represents the inclusive green growth level of city i in year t; denotes participation in CCRC, taking a value of 1 when city i is included in the pilot list for year t and subsequent years, and 0 otherwise; is the constant term; represents the coefficient of the pilot policy’s impact on inclusive green growth; comprises the control variables; and denote city and time fixed effects, respectively; while is the disturbance term.

- (2)

- Mediation effect model

To verify Hypothesis 2 of how technological innovation and resource misallocation mediate the link between CCRC and inclusive green growth, this paper develops the following mediation effect model based on Jiang (2022) [44]:

Here, denotes the mediating variable, encompassing technological innovation level () and degree of resource misallocation (). represents the coefficient gauging the core explanatory variable’s effect on the mediating variable. The remaining variables retain the same definitions as before.

- (3)

- Moderation Effect Model

To verify Hypothesis 3 and explore how economic agglomeration levels and public environmental awareness moderate the nexus between CCRC and inclusive green growth, the following moderation model is formulated:

Among these, denotes the moderating variables, comprising economic agglomeration intensity () and public environmental awareness intensity (). represents the interaction term of CCRC and the moderating variables, while the remaining variables retain the same meaning as previously defined.

4.2. Variable Specification

4.2.1. Independent Variable

Inclusive green growth (igg) represents a people-centered sustainable development model that seeks to balance economic growth, environmental protection, and social equity. Therefore, measuring inclusive green growth requires a comprehensive assessment of the overall efficiency of factor inputs and outputs. Data envelopment analysis (DEA) does not require normalized data, can process data in different measurement units, and can be used to evaluate production efficiency under multiple factor inputs without subjective influence. It is widely applied in productivity measurement. Therefore, this paper characterizes inclusive green growth through its efficiency metrics. Following the methodology of Song et al. (2023) [45], we employ a super-efficiency SBM model incorporating non-desirable outputs for measurement.

This model assumes n decision-making units, each with m inputs, s1 desired outputs, and s2 undesired outputs. The super-efficiency SBM model incorporating undesired outputs is expressed as follows:

Among these, , represent elements in the input, expected output, and non-expected output matrices, respectively. , , and denote the slack values for inputs, expected outputs, and non-expected outputs, respectively, all of which are greater than or equal to zero. λ is the weighting factor. IGG denotes the inclusive green growth efficiency value, which is greater than zero. A higher IGG indicates greater efficiency for the unit.

Based on the characteristics of inclusive green growth and the findings of Zhou et al. (2024) [42], Hu et al. (2025) [46], and Yan et al. (2024) [47], this study conceptualizes inclusive green growth across three dimensions: economic growth, social equity, and environmental sustainability. An input–output indicator system for economic inclusive green growth is constructed, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusive green growth indicator system.

- (1)

- Input. Labor input: measured by the number of persons employed at year-end; capital input: represented by fixed asset stock, with asset stock estimated using the perpetual inventory method as per Zhang, J. et al. (2004) [48]; energy input: following Shi et al. (2020) [49], urban energy consumption is characterized by introducing night-time light data fitted to an energy consumption table.

- (2)

- Expected output. Output indicators encompass three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. Expected outputs represent the economic and social benefits generated by inputs. Economic benefits are measured using actual GDP and fiscal revenue as indicators. Real GDP, adjusted for price fluctuations, accurately reflects the aggregate changes in urban production activities and the actual scale of economics. Fiscal revenue serves as a crucial indicator of economic growth quality, reflecting the sustainability of economics and governance capacity. It provides the essential foundation for environmental governance and social welfare enhancement. Together, these two metrics form the core for measuring economic growth. Social benefits are evaluated across four dimensions: household consumption, healthcare, social security, and educational services. These are quantified through retail sales of consumer goods, physicians per 10,000 population, pension scheme enrolment figures, and pupil–teacher ratios in primary and secondary schools. Residents’ consumption serves as a core indicator for measuring how economic development benefits people’s livelihoods, reflecting urban residents’ living standards, consumption capacities, and the vibrancy of the consumer market. Healthcare services are vital to residents’ health and well-being, demonstrating the sophistication of public health systems within CCRC. Social security serves as a critical pillar of inclusive growth, with pension insurance as a core coverage type, its enrollment directly reflects the scope of retirement’s inclusion and embodies the development goal of making welfare shared. The equity and quality of educational services represent the enduring manifestation of social benefits; a lower student–teacher ratio indicates greater investment and higher educational service quality.

- (3)

- Undesirable output, which encompasses both environmental and social damage. Environmental damage refers to pollution emissions generated by production activities, measured by urban waste discharge volumes: exhaust gases (sulphur dioxide), wastewater, and solid waste (industrial dust). The three pollutants represent the main types of contaminants in urban production activities, covering the three major pollution domains of air, water, and solid waste. Among them, sulfur dioxide serves as the signature pollutant of air pollution, with its emissions highly correlated to industrial energy consumption; wastewater discharge volumes reflect the damage caused by industrial and domestic sewage to water resources; and industrial dust directly impacts air quality. Together, these three pollutants form the fundamental evaluation dimensions for urban environmental quality. Social damage manifests as non-inclusive characteristics in the development process, primarily encompassing three dimensions: equality of opportunity, distributive fairness, and outcome sharing. These are represented by three indicators, respectively: unemployment rate, ratio of urban to rural disposable income, and ratio of urban to rural consumption expenditure. Changes in unemployment rates can measure whether employment inclusiveness is achieved. That is, whether large-scale unemployment is avoided and job opportunities for diverse groups are safeguarded. The ratio of disposable income between urban and rural residents can assess whether rural areas are benefited, and whether the income gap is narrowed. The ratio of consumption between urban and rural residents reflects disparities in living standards and measures whether the outcomes of CCRC are equitably shared across urban and rural areas, serving as a crucial factor for evaluating inclusiveness. Indicator selection and explanations are detailed in Table 2.

4.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

Dummy variable for CCRC (policy). Based on the pilot list established in China’s Notice on Issuing the Pilot Work for Climate-Resilient City Construction, cities are divided into two groups: pilot policy-implementing cities form the experimental group, assigned a value of 0 before 2017 and 1 from 2017 onward; non-participating cities act as the control group, coded 0 across all years.

4.2.3. Channel Variables

- (1)

- Mediating variables: Level of technological innovation (tec), measured by the number of patent applications per 10,000 population, is used as a proxy variable. Degree of resource misallocation (avg) using the resource misallocation index as proposed by Gao (2024) [50] assesses regional resource misallocation.

- (2)

- Moderating variables: Economic agglomeration (eag) is measured by employment density—the ratio of employed population to regional land area; public environmental awareness (pea) is assessed by taking the natural logarithmic form of the annual average Baidu search index for “environmental pollution” and “smog.”

4.2.4. Control Variables

Drawing on existing research, the following control variables are introduced: (1) Science and Technology Investment (sti), proxied by the ratio of fiscal spending on science and technology to total fiscal outlays; (2) Local Government Competition (lgc), gauged by the ratio of fiscal receipts to fiscal outlays; (3) environmental regulation (ers), represented by the overall utilization rate of industrial solid waste within urban jurisdictions; (4) Cultural Resources (cr), measured by the number of library books per capita; and (5) financial development (fdl), calculated as the percentage of year-end deposit and loan balances of financial entities relative to regional GDP.

4.3. Data Source

This research employs panel data spanning 2010 to 2022, covering 280 prefecture-level cities across China, excluding Bozhou, Jining, Sansha, Danzhou, Bijie, Tongren, Lhasa, Shigatse, Qamdo, Nyingchi, Shannan, Nagqu, Haidong, Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Wuzhong, Karamay, Turpan, Hami, Laiwu City, and Chaohu City (see Appendix A for details). The year of 2010 was selected as the starting point for the sample, as it marked the publication of the “Climate Change Response Plan (2010–2020),” which for the first time systematically outlined specific requirements for climate change response at the urban level. Furthermore, the Fifth Plenary Session of the 17th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China explicitly stated that “building a resource-conserving and environment-friendly society must be upheld as a key focus in accelerating the transformation of the economic development model.” This period marked a pivotal juncture in establishing China’s climate adaptation policy framework and implementing the concept of inclusive green growth. Data was sourced from the Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Cities, statistical bulletins of Chinese cities, the China National Research Data Service (CNRDS), Statistical Yearbook of China’s Energy, Baidu Search Index, and the National Information Center’s Macroeconomic and Real Estate Database. Missing values were supplemented using linear interpolation. Descriptive statistics pertaining to key variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of key variables.

5. Results

5.1. Baseline Results

To examine the impact of CCRC on inclusive green growth, this study employs a DID model for regression analysis, with results presented in Table 4. Column (1) of Table 4 shows that without any additional control variables, the pilot program’s coefficient for inclusive green growth is 0.052, significant at the 1% level. This indicates that CCRC can elevate the levels of inclusive green growth by approximately 5%. CCRC can mitigate the impact of extreme weather on production activities by building climate-resilient infrastructure. This, in turn, drives the production factors toward low-carbon, high-efficiency sectors. The findings align with the results of Zhang, J. et al. (2025) [17]. Moreover, existing research often focuses on emission reduction, whereas this study highlights the innovative perspective of adaptation and growth. Hypothesis 1 is validated.

Table 4.

Benchmark results of CCRC on inclusive green growth.

5.2. Robustness Test

5.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

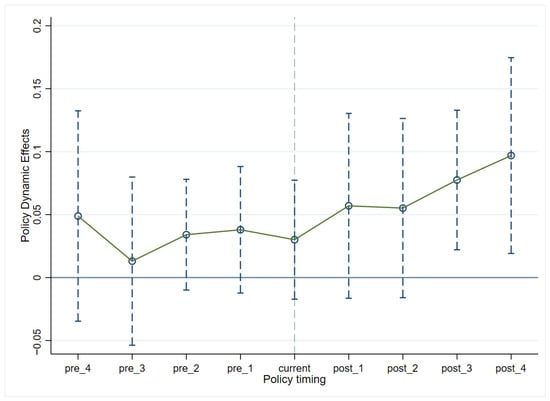

The parallel trend assumption between the experimental and control groups is a prerequisite for applying the DID model. To ensure model accuracy and result robustness, this study conducted parallel trend tests referencing Jacobson et al. (1993) [51], with results shown in Figure 5. The dummy variable on the horizontal axis represents the difference between the pilot policy implementation year and the actual year, with end-point trimming applied to retain the five years preceding the policy. To mitigate multicollinearity, the fifth period preceding the policy shock (pre_5) is selected as the baseline group and excluded. The vertical axis represents the dynamic policy effect. Prior to the implementation of the pilot policy, the estimated coefficient is not statistically significant, indicating that both the experimental and control group cities report similar trends of change. Following the policy’s implementation, the estimated coefficient gradually becomes significantly positive, signifying that the pilot policy exerts a clear positive impact on inclusive green growth in cities.

Figure 5.

Parallel trend test.

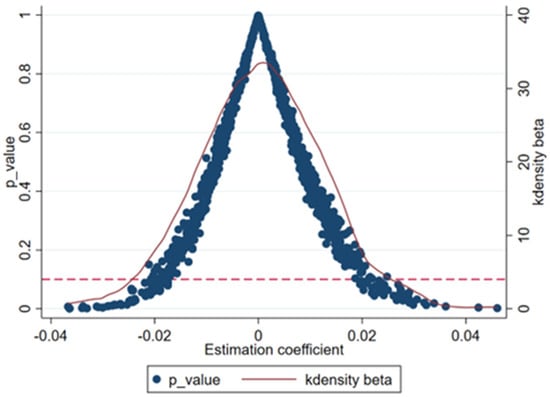

5.2.2. Placebo Test

To eliminate the influence of other unobservable factors on the benchmark regression results, this study further conducted a placebo test. Based on the distribution of CCRC variables in the baseline regression, 1000 pseudo-policy dummy variables were randomly generated through sampling. A new regression analysis was then performed, with the results shown in Figure 6. It can be observed that the estimated coefficient values of the randomly generated virtual policy primarily cluster around zero, with most p-values exceeding 0.1. The coefficient for policy in the benchmark regression result is 0.049, which emerges as a distinct outlier among the 1000 simulation results, thus confirming the robustness of the study’s conclusions.

Figure 6.

Placebo test.

5.2.3. Endogeneity Test

To prevent the potential risk of suffering from endogeneity brought about by omitted variables or reverse causality, this paper selects river density as an instrumental variable and employs two-stage least squares (2SLS) for endogeneity testing. Due to stringent upstream regulations of rivers, regions with high river density cannot directly discharge pollutants into rivers. This implies that these areas may face greater pollution control pressures, making them likely candidates for inclusion in pilot programs when governments implement environmental regulatory policies. Thus, this variable satisfies the correlation requirement [52]. The regression results are presented in Table 5. In the first-stage regression, the instrumental variable river is significant, indicating that the instrument satisfies the correlation condition. In the second-stage regression, policy remains significant, and its effect direction on the dependent variable is consistent with the benchmark regression. This suggests that after accounting for endogeneity, the pilot policy can still significantly enhance inclusive green growth.

Table 5.

Endogeneity test: two-stage least squares method.

5.2.4. PSM-DID Test

Although the DID model effectively addresses endogeneity issues, given that the pilot policy for CCRC carries inherent policy orientation and is not a purely natural experiment, sample selection bias may exist. A preferable method to avoid selection bias is propensity score matching. To this end, kernel matching is further applied based on the PSM-DID model, and the matched samples are re-estimated using the approach via model (1). As shown in Table 6, column (1), the coefficient for policy is 0.053, consistent with the baseline results, indicating that CCRC significantly promotes inclusive green growth.

Table 6.

Additional robustness test results.

5.2.5. Additional Robustness Checks

- (1)

- Exclude other policy disturbances. Throughout the sample adopted in this study, China also implemented other pilot policies that may have influenced inclusive green growth, potentially introducing extraneous factors into the regression results beyond the pilot policies themselves. Therefore, to assess the pure effect of CCRC while controlling for other concurrent policy disturbances, this study includes low-carbon city and smart city pilot programs into the model. We construct policy interaction variables (0–1) measuring low-carbon pilot (low carbon) and smart city (smart city) initiatives, respectively, and conduct multi-period DID regressions. The regression results in columns (2) and (3) of Table 6 show that the coefficients of the core explanatory variables are all significantly positive at the 1% level, confirming the robustness of the benchmark model’s empirical results.

- (2)

- Exclude municipalities. Due to significant disparities in population size, economic development levels, and infrastructure development between municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing) and ordinary prefecture-level cities, these differences may impact the regression results presented in this paper. Therefore, to eliminate this potential confounding factor, this study excludes municipalities directly under the central government in the robustness test, retaining only 276 prefecture-level cities for regression analysis. The results in column (4) of Table 6 show that the policy coefficient remains statistically significant at the 5% level and maintains the same direction as the baseline regression, further validating the reliability of the baseline regression results.

- (3)

- Replace the dependent variable. Drawing on the methodology of Li, Z. et al. (2023) [53], this study re-calculates the level of inclusive green growth using the entropy weight method and adopts it as the new dependent variable. We re-examine the relationship between CCRC and inclusive green growth using model (1), and the regression outcomes are reported in column (5) of Table 6. The results reveal that the coefficients and significance levels of key variables remain largely consistent with the benchmark regression findings. This further confirms CCRC’s promotional effect on inclusive green growth and underscores the robustness of the empirical conclusions presented earlier.

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3.1. Regional Heterogeneity

Due to significant developmental disparities across different urban locations, this study divides the sample into southern and northern groups based on the Qinling–Huaihe natural regional classification for regression analysis. This approach investigates the regional heterogeneity effects of CCRC. As shown in Table 7, columns (1) and (2), CCRC significantly promotes inclusive green growth in the south, but there are no such effects for the northern regions. This outcome likely stems from the southern regions’ more pronounced monsoon climate, which brings higher frequencies of extreme weather events like heatwaves, torrential rains, and typhoons. The urgent need for climate adaptation makes the pilot policy implementation more directly address local development challenges, effectively mitigating climate risks’ socioeconomic impacts and fostering synergistic economic growth with ecological conservation. In contrast, northern regions face climate challenges characterized by droughts and cold waves, which are relatively dispersed impacts. Consequently, the targeted nature and urgency of policy implementation are somewhat weaker, making it difficult for the short-term promotion of inclusive green growth to be readily apparent.

Table 7.

Tests for heterogeneity.

5.3.2. Resource Endowment Heterogeneity

Resource endowment advantages can be leveraged as the core foundation for building climate-resilient cities. According to the classification criteria of China’s National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-Based Cities, this study categorizes 280 sample cities into resource-based cities (coded as 1) and non-resource-based cities (coded as 0), conducting separate regressions for each group. The results in columns (3) and (4) of Table 7 indicate that the pilot policy significantly promotes inclusive green growth in non-resource-based cities, whereas this policy effect fails to pass the significance test in resource-based cities. This discrepancy may stem from the relatively monolithic industrial structure of resource-based cities, whose development heavily relies on natural resource industries. The extraction and transportation of natural resources consume substantial energy and generate pollutants, which are the factors that partially diminish the pilot policy’s promotional effect on inclusive green growth. In comparison, non-resource-based cities rely more heavily on sound industrial structures and technological innovation. The implementation of CCRC promotes technological innovation and enhances economic efficiency, and thus strengthens inclusive green growth in non-resource-based cities.

5.3.3. Urban Hierarchical Heterogeneity

Urban tiers fundamentally reflect disparities in administrative resources and economic strength among cities, and these differences directly impact investment capacity for climate resilience development and the spillover effects of inclusive green growth. Taking China’s 2022 City Commercial Appeal Ranking as the basis, this paper categorizes 280 sample cities into economically developed and economically underdeveloped regions, conducting separate regression analyses for each. The results in columns (5) and (6) of Table 7 indicate that CCRC significantly promotes inclusive green growth in economically developed regions, while the impact shows no evidence in the rest. This disparity likely stems from differing resource endowments across cities at varying stages of economic development. Economically advanced cities possess more developed infrastructure and ample fiscal resources, enabling them to effectively implement the pilot policy for CCRC and achieve significant gains in inclusive green growth. In contrast, less developed cities face constraints in resource allocation due to lower economic development levels, making it difficult to mobilize sufficient funds for the infrastructure and talent development required for CCRC. This, to some extent, limits the effectiveness of pilot implementation in economically underdeveloped regions.

5.4. Channel Analysis

5.4.1. Estimated Results of the Mediation Model

This study constructs a mediation model for identification and testing, with results presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 8. The coefficient for CCRC’s effects on technological innovation is significantly positive. This indicates that the pilot policy effectively promotes R&D investment and commercialization of green technologies, giving policy incentives and demand stimulation. This conclusion aligns with the logic in green growth theory that policies stimulate technological innovation.

Table 8.

Results of the mediation and the moderation models.

However, the coefficient for CCRC on the resource misallocation index was 0.038 and was significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that CCRC did not optimize resource allocation but instead exacerbated resource misallocation to some extent. This finding contradicts the theoretical expectation in Hypothesis 2, yet it possesses clear economic logic and practical rationality: First, CCRC centers on green principles; it concentrates capital, labor, technology, and other production factors toward environmentally sustainable and climate-resilient sectors, driving the flow of resources from traditional industries to green industries. Such targeted concentration optimizes factor allocation within the green development sector; however, from a holistic industrial perspective, this reduces supplies to non-green sectors, leading to an overall increase in resource misallocation. Second, CCRC’s stricter standards on heavy industries exhibit stickiness, making it difficult to rapidly shift them to green sectors. This creates a lag in factor allocation between traditional and green industries, exacerbating short-term resource misallocation.

5.4.2. Estimated Results of the Moderation Model

To investigate the moderating effects of economic agglomeration levels and public environmental awareness on the policy outcomes of CCRC, this study constructs a moderation model. The results are presented in Table 9, columns (3) and (4). Column (3) reveals that the coefficient for CCRC and the interaction coefficient between economic agglomeration and CCRC are both significantly positive at the 1% level. This aligns with the agglomeration externalities of spatial economics, suggesting that high-density economic activities enhance policy transmission efficiency. This indicates that economic agglomeration positively moderates CCRC’s promoting effects on inclusive green growth. Column (4) shows that the coefficient for the interaction term between public environmental awareness and CCRC is significantly positive at the 5% level. By intensifying urban environmental protection efforts and encouraging enterprises, residents, and organizations to participate in pilot city construction, CCRC fully stimulates public enthusiasm for environmental protection and governance. Furthermore, public environmental awareness exerts a significant positive moderating effect on the relationship between CCRC and inclusive green growth [54]. In conclusion, Hypothesis 3 is verified.

Table 9.

Moran’s I values for inclusive green growth.

5.5. Spatial Metric Analysis

To more accurately assess the impact of CCRC on inclusive green growth, this study further examines the spatial correlation of inclusive green growth using a spatial weighting matrix. Table 9 presents the spatial correlation test results for inclusive green growth based on the global Moran’s I index. It is evident that between 2010 and 2022, the global Moran’s I index for inclusive green growth was significantly positive at the 1% level. Therefore, spatial factors must be incorporated when examining the impact of CCRC on inclusive green growth.

In addition, this study refers to Elhorst (2014) [55] to conduct spatial model applicability tests. Based on the results in Table 10, the fixed effects spatial Durbin model (SDM) was ultimately selected for regression analysis, with the SAR model and SEM employed as robustness tests.

Table 10.

LM, Robust-LM, LR, Wald, and Huasman test results.

As shown in columns (1), (5), and (6) of Table 11, the policy coefficients for all three spatial regression models are significantly positive. This aligns with the benchmark regression, confirming that CCRC significantly promotes inclusive green growth. Further decomposing the impact of CCRC on inclusive green growth into direct, indirect, and total effects (as shown in columns (2)–(4)), the coefficients for all three components are statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates that while the pilot policy directly stimulates local inclusive green growth, it also drives the inclusive green growth levels of neighboring regions through spatial spillover effects.

Table 11.

SDM regression results.

6. Conclusions

This study utilizes a dataset from 280 Chinese cities spanning 2010–2022 to examine the channels and spatial effects of the pilot policy for CCRC on inclusive green growth. The conclusions are drawn. (1) CCRC significantly promotes inclusive green growth. (2) The pilot policy exhibits distinct heterogeneity in driving inclusive green growth: regionally, it significantly impacts southern regions, while there are no such effects in northern parts; by city type, it significantly affects non-resource-based cities; and by economic development level, it significantly impacts economically developed regions. (3) CCRC enhances inclusive green growth through the mediating effects of technological innovation, although it does aggravate resource misallocation; the channels of economic agglomeration and public environmental awareness play moderating roles. (4) The pilot policy for CCRC generates positive spatial spillover effects on the inclusive green growth of neighboring cities.

7. Discussion

The pilot policy for CCRC serves as a key driver for achieving inclusive green growth, balancing the dual objectives of “enhancing resilience” and “promoting inclusive growth.” The policy’s effectiveness demonstrates the synergy between climate governance and economic development. The mediating role of technological innovation, alongside the moderating effects of economic agglomeration and public participation, reveals a collaborative pathway characterized by “policy guidance + market-driven forces + social engagement.” Regional heterogeneity, resource endowments, and urban hierarchy necessitate moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches toward locally tailored policies. Spatial spillover effects underscore the transboundary nature of climate governance, requiring the dismantling of administrative barriers to build collaborative networks. This approach offers valuable Chinese experience—both theoretically and practically—for advancing global climate adaptation and green growth in tandem.

7.1. Recommendations

First, we recommend implementing a differentiated pilot advancement strategy with clearly defined operational pathways for each category. Develop regional- and city-specific implementation guidelines:Southern developed cities should delineate demonstration zones, incorporate climate adaptation metrics into high-tech enterprise certification scoring, and allow tax deductions for R&D expenses on low-carbon technologies via specialized reports. Northern cities should establish specialized industry technology catalogs. Arid regions should provide equipment purchase subsidies for water-saving irrigation technology R&D firms while concurrently establishing technology promotion service stations. Resource-based cities may apply for central budgetary investment based on succession industry plans, with priority support for biomedical project implementation. A dynamic evaluation process where third-party institutions conduct biennial assessments using unified metrics should also be established, generating adjustment recommendations for provincial department filing.

Second, we recommend building a “technology + industry + public” coordination mechanism to refine full-chain implementation measures. Technologically, science and technology departments will spearhead cross-departmental innovation platforms, establish billion-yuan special funds, and provide one-time rewards to teams achieving breakthroughs in key technologies. “Industry–academia–research–application” transformation agreements will clarify responsibilities and revenue sharing among parties. Industrially, a “checklist + accountability system” will be implemented, setting timelines and task lists for emissions reductions in traditional industries. Compliant enterprises will gain priority access to land based on verification reports. Emerging industrial clusters will designate aggregation zones with shared environmental facilities. At the public level, a “Green Points” online platform will be launched with clear redemption standards and monthly updates to science outreach activity listings. The environmental information platform will publish quarterly emission data accompanied by visual charts illustrating policy implementation outcomes.

Third, we recommend establishishing a cross-regional collaborative governance network and implementing coordinated action mechanisms. Collaborative alliances should be formed based on urban clusters, with the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta immediately establishing smart collaboration platforms. Data-sharing catalogs should be defined and cross-city ecological corridor construction standards developed based on Shenzhen’s experience. The “enclave industrial park” model should be standardized by defining industrial positioning, environmental standards, and tax revenue sharing ratios for jointly developed parks between eastern and central/western regions. A cross-provincial evaluation mechanism should be established incorporating green growth indicators of neighboring cities into pilot assessments. Cities demonstrating significant collaborative achievements will receive special incentives, creating replicable linkage processes.

7.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7.2.1. Limitations

Regarding data selection, constrained by the availability and consistency of statistical data across certain cities, the research sample does not fully cover all prefecture-level cities in China. Additionally, some variables are measured using proxy indicators. Although multiple tests have been conducted to ensure the reliability of the results, subtle differences remain compared to directly observed data. Regarding the indicator system construction, inclusive green growth encompasses three core dimensions: economic growth, environmental governance, and social equity. Its influencing factors exhibit complexity and diversity. Constrained by the observability and quantifiability of variables, this study selects only key measurable indicators for empirical analysis. Consequently, it does not comprehensively cover all potential influencing factors, and certain dimensions that are difficult to quantify are not included in the consideration. Furthermore, the indicator system is constructed based on current theoretical understanding and available data. However, the concept and influencing factors of inclusive green growth are dynamically evolving. This system may not fully adapt to future development scenarios and research needs, potentially leading to discrepancies between subsequent studies and the findings of this research. Regarding the research perspective, this study mainly examines the macro-level impact of CCRC on inclusive green growth. It does not delve into micro-level variations in policy responses among enterprises of different scales and industrial sectors, leaving room for further exploration of corporate-level heterogeneity.

7.2.2. Future Research Directions

Future research can be further expanded from multiple dimensions: First, as the statistical system gradually improves, the sample can be expanded to include more prefecture-level city and county-level data, as well as micro-level enterprise survey data. This will establish a multi-level analytical framework encompassing macro-, meso-, and micro-levels, thereby refining the transmission pathways of policy effects. Second, aligning with the dynamic evolution of inclusive green growth, the breadth and depth of the indicator system should be expanded by incorporating additional potential influencing factors. Simultaneously, alternative measurement methods should be explored for dimensions that are difficult to quantify, enhancing the comprehensiveness and precision of research through a multidimensional, multi-level indicator framework. Third, research perspectives should be broadened to deeply explore synergies between CCRC and strategic initiatives like the digital economy and new urbanization, analyzing the combined impact of multiple overlapping policies on inclusive green growth and providing comprehensive references for optimizing policy portfolios. Fourth, interdisciplinary theories and methodologies should be introduced. For instance, case studies can be employed to track policy implementation processes in exemplary pilot cities, or machine learning utilized to extract key influencing factors from unstructured data, thereby enriching research paradigms. Simultaneously, research timeframes should be extended to examine long-term dynamic effects, investigate the evolution of policy outcomes across different stages, and assess the stability of policy impacts under extreme climate events. This will provide more vigorous support for long-term policy improvements.

Author Contributions

Data curation, W.L.; Writing—original draft, W.L.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Z., W.L., D.Z., and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shaanxi Provincial Social Science Fund Project [2023D044]; Xi’an Shiyou University [YCS23214335]; and the National Social Science Fund Western Region Project [24XJY025].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the authors upon request. To obtain the data from this study, please contact Wenya Lu at the following email address: 23211091199@stumail.xsyu.edu.cn.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

This study selected 280 sample cities across 30 Chinese provinces as samples. The remaining 20 cities were excluded to eliminate the potential bias caused by incomplete statistical data. Notes of samples have been added in the data explanation section. Because of space limitations, not all cities are listed in the main text. The full list is below.

| Beijing Municipality | Beijing Municipality |

| Tianjin Municipality | Tianjin Municipality |

| Hebei Province | Shijiazhuang City, Tangshan City, Qinhuangdao City, Handan City, Xingtai City, Baoding City, Zhangjiakou City, Chengde City, Cangzhou City, Langfang City, Hengshui City |

| Shanxi Province | Taiyuan City, Datong City, Yangquan City, Changzhi City, Jincheng City, Shuozhou City, Jinzhong City, Yuncheng City, Xinzhou City, Linfen City, Lvliang City |

| Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | Hohhot City, Baotou City, Wuhai City, Chifeng City, Tongliao City, Ordos City, Hulunbuir City, Bayannur City, Ulanqab City |

| Liaoning Province | Shenyang City, Dalian City, Anshan City, Fushun City, Benxi City, Dandong City, Jinzhou City, Yingkou City, Fuxin City, Liaoyang City, Panjin City, Tieling City, Chaoyang City, Huludao City |

| Jilin Province | Changchun City, Jilin City, Siping City, Liaoyuan City, Tonghua City, Baishan City, Songyuan City, Baicheng City |

| Heilongjiang Province | Harbin City, Qiqihar City, Jixi City, Hegang City, Shuangyashan City, Daqing City, Yichun City, Jiamusi City, Qitaihe City, Mudanjiang City, Heihe City, Suihua City |

| Shanghai Municipality | Shanghai City |

| Jiangsu Province | Nanjing City, Wuxi City, Xuzhou City, Changzhou City, Suzhou City, Nantong City, Lianyungang City, Huai’an City, Yancheng City, Yangzhou City, Zhenjiang City, Taizhou City, Suqian City |

| Zhejiang Province | Hangzhou City, Ningbo City, Wenzhou City, Jiaxing City, Huzhou City, Shaoxing City, Jinhua City, Quzhou City, Zhoushan City, Taizhou City, Lishui City |

| Anhui Province | Hefei City, Wuhu City, Bengbu City, Huainan City, Ma’anshan City, Huaibei City, Tongling City, Anqing City, Huangshan City, Chuzhou City, Fuyang City, Suzhou City, Lu’an City, Chizhou City, Xuancheng City |

| Fujian Province | Fuzhou City, Xiamen City, Putian City, Sanming City, Quanzhou City, Zhangzhou City, Nanping City, Longyan City, Ningde City |

| Jiangxi Province | Nanchang City, Jingdezhen City, Pingxiang City, Jiujiang City, Xinyu City, Yingtan City, Ganzhou City, Ji’an City, Yichun City, Fuzhou City, Shangrao City |

| Shandong Province | Jinan City, Qingdao City, Zibo City, Zaozhuang City, Dongying City, Yantai City, Weifang City, Tai’an City, Weihai City, Rizhao City, Linyi City, Dezhou City, Liaocheng City, Binzhou City, Heze City |

| Henan Province | Zhengzhou City, Kaifeng City, Luoyang City, Pingdingshan City, Anyang City, Hebi City, Xinxiang City, Jiaozuo City, Puyang City, Xuchang City, Luohe City, Sanmenxia City, Nanyang City, Shangqiu City, Xinyang City, Zhoukou City, Zhumadian City |

| Hubei Province | Wuhan City, Huangshi City, Shiyan City, Yichang City, Xiangyang City, Ezhou City, Jingmen City, Xiaogan City, Jingzhou City, Huanggang City, Xianning City, Suizhou City |

| Hunan Province | Changsha City, Zhuzhou City, Xiangtan City, Hengyang City, Shaoyang City, Yueyang City, Changde City, Zhangjiajie City, Yiyang City, Chenzhou City, Yongzhou City, Huaihua City, Loudi City |

| Guangdong Province | Guangzhou City, Shaoguan City, Shenzhen City, Zhuhai City, Shantou City, Foshan City, Jiangmen City, Zhanjiang City, Maoming City, Zhaoqing City, Huizhou City, Meizhou City, Shanwei City, Heyuan City, Yangjiang City, Qingyuan City, Dongguan City, Zhongshan City, Chaozhou City, Jieyang City, Yunfu City |

| Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region | Nanning, Liuzhou, Guilin, Wuzhou, Beihai, Fangchenggang, Qinzhou, Guigang, Yulin, Baise, Hezhou, Hechi, Laibin, Chongzuo |

| Hainan Province | Haikou, Sanya |

| Chongqing Municipality | Chongqing |

| Sichuan Province | Chengdu, Zigong, Panzhihua, Luzhou, Deyang, Mianyang, Guangyuan, Suining, Neijiang, Leshan, Nanchong, Meishan, Yibin, Guang’an, Dazhou, Ya’an, Bazhong, Ziyang |

| Guizhou Province | Guiyang, Liupanshui, Zunyi, Anshun |

| Yunnan Province | Kunming City, Qujing City, Yuxi City, Baoshan City, Zhaotong City, Lijiang City, Pu’er City, Lincang City |

| Shaanxi Province | Xi’an City, Tongchuan City, Baoji City, Xianyang City, Weinan City, Yan’an City, Hanzhong City, Yulin City, Ankang City, Shangluo City |

| Gansu Province | Lanzhou City, Jiayuguan City, Jinchang City, Baiyin City, Tianshui City, Wuwei City, Zhangye City, Pingliang City, Jiuquan City, Qingyang City, Dingxi City, Longnan City |

| Qinghai Province | Xining City |

| Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region | Yinchuan City, Shizuishan City, Guyuan City, Zhongwei City |

| Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | Urumqi City |

References

- Ma, R.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Fu, S. Promoting sustainable development: Revisiting digital economy agglomeration and inclusive green growth through two-tier stochastic frontier model. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 355, 120491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, I.K.; Figari, F.; Ojong, N. Towards sustainability: The relationship between foreign direct investment, economic freedom and inclusive green growth. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 137020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ding, W.; Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Du, J. Measuring China’s regional inclusive green growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Xia, J. Towards Inclusive Green Growth in China: Synergistic Roles and Mechanisms of New Infrastructure Construction. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.; Ghouse, G. Targeting the New Sustainable Inclusive Green Growth: A Review. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 11, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Dandgawhal, P.S.; Giri, A.K. Impact of ICT Diffusion and Financial Development on Economic Growth in Developing Countries. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2023, 28, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change: The IPCC Impacts Assessment. In Contribution of Working Group II to the First Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, A.; Driessen, P.P.; van Rijswick, M.; Rietveld, P.; Salet, W.; Spit, T.; Teisman, G. Towards adaptive spatial planning for climate change: Balancing between robustness and flexibility. J. Eur. Environ. Plan. Law 2013, 10, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Dawson, R.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Delgado, G.; Salisu Barau, A.; Dhakal, S.; Dodman, D.; Leonardsen, L.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Roberts, D.C.; et al. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature 2018, 555, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Cao, Y.; Yang, X. Progress analysis and policy recommendation on climate adaptation city pilots in China. Clim. Change Res. 2020, 16, 770–774. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, J.; Gao, B.; Cao, W.; Dou, H. Develop climate-resilient cities tailored to local conditions. People’s Daily, 22 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Upholding the Important Concept of “People-Centered Urban Development” and Steadily Promoting the Construction of Climate-Adaptive Cities. J. Explor. Free Views 2022, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, L. The Significance and Pathways of Building Resilient Cities in the Context of Climate Change. J. Gov. 2023, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yao, M.; Zheng, Y. Impact of the pilot policy for constructing climate resilient cities on urban resilience. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, L. Do climate change adaptation policies raise urban resilience?—Evidence from ‘climatic adaptive cities’ construction pilot. J. Resour. Ind. 2025, 27, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z. The effect of pilot climate-adapted city policy on urban sustainability: An empirical analysis based on difference-in-differences model. J. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 10065–10076. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Fang, S.; Tian, Y. Climate Governance and Urban Carbon Emission Reduction—A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Pilot Policy of Climate-Resilient City Construction. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 27, 76–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Hu, K.; Yao, J. Climate Governance and Corporate Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from China’s Climate Resilient City Pilot Program. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2025, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xia, Q.; Sun, H. Climate-adapted Urban Construction, Corporate Resilience and Supply Chain Spillovers. J. Tech. Econ. Manag. 2025, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Niu, J.; Niu, J.; Wang, Y. Pilot Policies for Climate-Adaptive Urban Development and Corporate Greenwashing Behavior. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 104, 104741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Deng, N.; Li, T. Resilience and Efficiency: Assessing China’s Climate Adaptation Policy Impact on Urban Green Development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 134, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, S.; Griffithjones, S. Mobilising Investment for Inclusive Green Growth in Low-Income Countries; International Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, J.; Berkhout, E. Inclusive green growth. In PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency; PBL Publication: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2015; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Rauniyar, G.; Kanbur, R. Inclusive growth and inclusive development: A review and synthesis of Asian Development Bank literature. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2010, 15, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, R.; Wu, J. Research Progress of Inclusive Green Growth and the Transformation of Its Driving Forces. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2022, 44, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Dong, Y. China’s High-quality Economic Development Level and the Source of Differences: Based on the Inclusive Green TFP Perspective. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 47, 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Liao, M.; Zhang, H. Network Infrastructure Construction, Knowledge Flow and Inclusive Green Growth in Cities: Based on the Moderated and Serial Mediating Analysis Framework. J. Stat. Res. 2024, 41, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, W. The Measurement and Analysis of the Inclusive Green Growth in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2018, 35, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aminata, J.; Nusantara, D.I.K.; Susilowati, I. The analysis of inclusive green growth in Indonesia. J. Ekon. Studi Pembang. 2022, 23, 140–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori, I.K.; Gbolonyo, E.Y.; Ojong, N. Foreign direct investment and inclusive green growth in Africa: Energy efficiency contingencies and thresholds. Energy Econ. 2023, 117, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, J. Network Infrastructure, Inclusive Green Growth, and Regional Inequality: From Causal Inference Based on Double Machine Learning. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2023, 40, 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Li, L.; Han, Y.; Hao, Y.; Wu, H. The emerging driving force of inclusive green growth: Does digital economy agglomeration work? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1656–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Luo, S.; Li, S.; Xue, Y.; Hao, Y. Fostering urban inclusive green growth: Does corporate social responsibility (CSR) matter? J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 189, 677–698. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, J.; Song, P. Regional Differences and Spatial-temporal Evolution of Urban Inclusive Green Efficiency in China. Inq. Into. Econ. Issues 2025, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.A.; Kaya, E.; Çitil, M.; Pilatin, A.; Barut, A. Natural resource trade and financial technology as drivers of inclusive green growth in Belt and Road initiative countries. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 62, 101903. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Wen, G. How does digital finance influence urban inclusive green growth? Empirical evidence from China. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100737. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, Q. How does digital economy achieve inclusive economic growth with efficiency, equity and green? International evidence. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2025, 36, 1283–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yuan, T.; Zhao, Z. Threshold effect between urbanization and green development performance. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2019, 33, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Ding, B. Green Growth with Equity: How Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy Builds Coordinated Development Pathways in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.; Wang, P.; Bu, Y. Climate policy and inclusive green growth: The role of China’s low-carbon city pilot policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 519, 145959. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, X. Can new quality productive forces promote inclusive green growth: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1499756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wu, Y.; Song, J. Symbiosis and co-prosperity: Industrial intelligence development and inclusive green growth. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 34, 162–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, G. Environmental regulation, technological innovation and carbon productivity. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T. Mediating Effects and Moderating Effects in Causal Inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Wei, X. Low-carbon C ity Construction, Green Technology Innovation and Inclusive Low-carbon Growth. J. Econ. Surv. 2023, 40, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y. The Impact of New Quality Productive Forces on Inclusive Green Growth in Cities. J. Reg. Econ. Rev. 2025, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Ding, C.; Xin, L. A Study on the Impact of Carbon Inclusion System on Inclusive Low-Carbon Development. J. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 40, 13–22+47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Zhang, J. The Estimation of China’s provincial capital stock: 1952–2000. Econ. Res. J. 2004, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Li, S. Emissions Trading System and Energy Use Efficiency—Measurements and Empirical Evidence for Cities at and above the Prefecture Level. China Ind. Econ. 2020, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Xia, S.; Chen, Y.; Da, Y. Target Management of Local Economic Growth, Resource Misallocation and Market Integration: Empirical Evidence from Yangtze River Delta. J. Yunnan Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 40, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, L.S.; LaLonde, R.J.; Sullivan, D.G. Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Rui, J. Environmental Regulation, Economic Growth Target Management and China’s High-Quality Economic Development. J. Macro-Qual. Res. 2023, 11, 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Sun, W. Digital Infrastructure Construction Enables Inclusive Green Growth: Internal Mechanism and Empirical Evidence. J. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2023, 15–24+156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wan, G.; Sun, W.; Luo, D. Public Demands and Urban Environmental Governance. J. Manag. World 2013, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2014, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.