Abstract

The rise in seasonal lifestyle tourism, characterized by winter-escape health and wellness stays and long-term leisure residence, has intensified peak–off-peak imbalances and pressures on the allocation of tourism service supply in tropical island destinations. However, existing research lacks a systematic comparison of seasonal fluctuations and long-term evolution for this subgroup at the city/county level. Therefore, this study aims to characterize the seasonal pattern, long-term trend features, and typological differentiation of seasonal lifestyle tourism at the county level, and to compare differences across types. Using monthly data on seasonal lifestyle tourism for 18 cities/counties in Hainan from 2021 to 2024, we apply TRAMO/SEATS decomposition to identify seasonal structures and measure seasonal amplitude and employ the Hodrick–Prescott (HP) filter to extract trend components and determine their directions of change. We further construct five development types by integrating trend categories and changes in seasonal amplitude and test between-type differences using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results show that Hainan exhibits a stable “winter–spring peak and summer–autumn trough” pattern (peaks concentrated in January–March and December, with the off-season typically spanning May–October), with strong seasonality and pronounced spatial heterogeneity. The four-year mean seasonal range at the county level is 215.01, with high values clustered in southern Hainan; Haikou remains relatively low, while Wenchang shows an upward trend. Long-term trends are clearly differentiated: 13 counties show sustained growth, 2 show decline, and 3 display a U-shaped recovery (decline followed by rebound). Growth rates also vary substantially, with Qionghai increasing at roughly 27 times the rate of Qiongzhong. Integrating seasonal and trend characteristics yields five types, of which the Robust Development type accounts for the largest share (50%). Between-type differences are mainly reflected in tourism service supply capacity: the number of star-rated hotels (p = 0.033, η2 = 0.530) and overnight visitors (p = 0.004, η2 = 0.676) differ significantly across types, whereas differences in natural-environment conditions are not significant. This study provides a scientific basis for zoning management and optimizing low-season strategies in Hainan.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Existing Problems

Tourism is a widespread socio-economic phenomenon [1,2], and has become a vital component of the tertiary sector. It serves not only as a major driver of regional economic growth but also stimulates the expansion in ancillary industries, such as real estate, service sectors, and infrastructure development [3,4]. As the social economy matters and consumer preferences evolve, tourism is shifting from simple sightseeing to lifestyle choice, leading to the emergence of seasonal lifestyle tourists. Although a unified academic definition for this growing demographic remains elusive, a general consensus acknowledges that they are distinct from conventional tourism, characterized by their seasonality, itinerancy, and long-term engagement [5,6]. This group primarily engages in seasonal, circuit-like migrations driven by the pursuit of a superior living environment rather than specific tourist attractions, marking a fundamental shift from the “experiential consumption” of traditional tourists to “lifestyle consumption.” This paradigm shift manifests in several key dimensions: in core motivation, from seeking novelty and sightseeing to pursuing livability; in spatiotemporal patterns, from short-term, one-off visits to long-term, repetitive, circuit migrations; and in their relationship with the destination, from being peripheral service consumers to becoming temporary residents deeply integrated into the local community. Consequently, the necessity for specialized research into their seasonality lies in the fact that their migration rhythms exert a sustained and profound impact on the social and ecological systems of the destination, far exceeding the short-term economic fluctuations associated with traditional tourists.

Tropical islands, favored for their pleasant climate, abundant coastal resources, and distinctive natural and cultural landscapes, have long served as prominent tourism destinations worldwide [7,8,9]. Studies on tropical island destinations such as those in the Indian Ocean and the Caribbean also indicate that tourism demand often exhibits pronounced seasonal peak–trough differentiation [10,11]. However, existing studies have largely focused on aggregate tourist flows or analyses at macro spatial scales. While such approaches can describe general seasonal patterns, they struggle to reliably distinguish seasonal lifestyle tourists as a specific market segment from the overall tourist population, and they are even less able to simultaneously capture this group’s seasonal fluctuations, long-term trends, and spatial heterogeneity at the city/county level. As China’s only tropical island province, Hainan also exhibits pronounced intra-provincial differences across its cities and counties in terms of resource endowments, transport accessibility, and service provision, which leads to a highly differentiated spatial pattern of seasonal lifestyle tourism [12]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a dynamic analytical framework to systematically identify the spatiotemporal evolutionary heterogeneity of seasonal lifestyle tourism at micro spatial scales within Hainan, thereby providing targeted evidence to support the sustainable development of island tourism. It should be noted that the study period (2021–2024) falls within the post-COVID recovery phase, during which the pace of recovery may have, to some extent, disrupted recent seasonality patterns in tourism demand; therefore, this study will take this contextual factor into full consideration when interpreting the results.

1.2. Analysis of Existing Research

Existing research on tourism seasonality has developed a substantial theoretical and empirical foundation, revealing seasonal regularities driven by natural and institutional factors and their impacts on destinations [13,14]. In terms of measurement, static indicators such as the annual concentration ratio, seasonal intensity index, and the Gini coefficient have been widely used [15,16]. These measures are straightforward to compute and enable comparability across cases, but they are limited in capturing the dynamic evolution of seasonal fluctuations and their linkage with long-term trends. To address this limitation, some studies have introduced time-series decomposition approaches such as TRAMO/SEATS [17,18], which allow a more refined characterization of temporal variation. Nevertheless, two major gaps remain. First, regarding the research object, many studies rely heavily on aggregate tourist flow data, and relatively few examine seasonality within specific market segments [19,20,21]. Second, regarding spatial scale, existing work has largely focused on macro-level differences across countries or regions [22,23,24], with insufficient attention to spatial heterogeneity at the micro (city/county) level within a province. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop an integrated analytical framework oriented toward segmented groups that can simultaneously capture seasonal fluctuations, long-term trends, and city/county-level spatial differentiation, thereby addressing the limitations of existing research in terms of research object and spatial scale.

1.3. Advantages of the Research

In response to the limitations of existing research, the advantages of this study are reflected in three dimensions: object precision, scale refinement, and feature-based typology. First, in terms of the research object, this study focuses on seasonal lifestyle tourists as a behaviorally segmented group. Compared with the “homogenization” of tourist flows in traditional studies, this focus enables a more precise identification of the distinctive temporal rhythms shaped by their long-term stays and cyclical migrations. Second, in terms of spatial scale, the analysis is downscaled from macro regions to city/county units. Through a systematic comparison of intra-provincial spatial heterogeneity, it captures internal differences that are often smoothed out from a macro perspective, thereby providing more fine-grained empirical evidence to support differentiated destination resource allocation. Third, with respect to typology construction, this study employs mature time-series tools—TRAMO-SEATS decomposition and the Hodrick–Prescott (HP) filter—to extract seasonal and trend components. Based on the seasonal and trend-evolution characteristics of tourists, it develops a destination development typology and further investigates the underlying differences across types.

1.4. Structure and Main Contributions of This Work

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 systematically reviews the literature on tourism seasonality and summarizes key research progress and remaining gaps. Section 3 introduces the study area, data sources, research methods, and the overall methodological framework. Section 4 presents the empirical results, including the identification of seasonal and trend characteristics, destination typology construction and inter-type differentiation; robustness checks and questionnaire-based analyses are further conducted to strengthen interpretation. Section 5 summarizes the study by synthesizing the main findings, highlighting contributions and limitations, discussing potential applications and practical value, and outlining directions for future research.

This study makes three main contributions. First, based on official monthly arrivals data of seasonal lifestyle tourists for 18 cities and counties in Hainan from 2021 to 2024, we provide a systematic characterization of the temporal patterns of this segmented group, offering finer-grained evidence for tourism seasonality research beyond aggregate tourist flows. Second, by downscaling the analysis to the city/county level, we reveal pronounced intra-provincial spatial heterogeneity in seasonal intensity and development trends, especially the more differentiated dynamics during the low season—patterns that are often smoothed out or obscured in macro-scale studies. Third, we propose a governance-oriented diagnostic framework that integrates seasonal decomposition with long-term trend identification to scientifically classify city/county tourism development types, thereby providing an operational basis for zoning management and targeted low-season strategies in tropical island destinations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concept, Drivers, and Impacts of Tourism Seasonality

Tourism seasonality is commonly regarded as a periodic imbalance in tourism activities and is one of the defining characteristics of the tourism industry [25]. Early explanations emphasized the joint effects of natural conditions and institutional arrangements [13]. Subsequent studies have incorporated additional factors such as social customs, industry practices, marketing activities, and calendar effects, forming a multifactor explanatory framework [14]. In terms of impacts, peak seasons often trigger concentrated environmental and social pressures—including ecological degradation, stress on cultural heritage, environmental pollution, traffic congestion, and rising prices—thereby affecting residents’ quality of life and tourists’ experiences [26,27]. By contrast, low seasons may lead to resource underutilization and operational risks, while also offering a window for ecosystem recovery and cultural heritage restoration [26,27,28]. Overall, research on tourism seasonality should not be limited to describing fluctuations in visitor volumes, but should also examine how such variability affects destination resource allocation and public service provision, thereby elucidating its linkage with sustainable tourism development.

2.2. Heterogeneity of Tourism Seasonality

Driven by multiple factors such as climate and market structures, tourism seasonality exhibits substantial variation in both form and intensity across places [29]. Existing studies have documented cross-national and cross-regional differences, for example, distinct seasonal patterns of overnight tourism across European countries [22] and differentiated seasonality among Mediterranean islands [23]. Within a single country, diverse seasonal rhythms have also been observed across destinations—for instance, substantial differences among Canadian vacation destinations [24] and varying degrees of seasonal concentration across Spanish provinces [30]. Even within the same region, coastal and inland areas may follow different seasonal dynamics; for example, tourism demand seasonality in Alaska is stronger in inland areas than in coastal areas [31]. For island destinations, fragile ecosystems and the high costs of scaling public services often amplify the environmental and social consequences of seasonal fluctuations [23,32,33,34]. However, compared with the extensive discussion of macro-scale differences, micro-scale heterogeneity at the city/county level within a province remains insufficiently examined, which provides an entry point for this study in Hainan.

2.3. Segment-Specific Seasonality Across Visitor Types

Although research on seasonality in overnight and inbound tourism is relatively mature [19], studies increasingly introduce segmented tourist groups to better understand seasonal structures. Evidence suggests that seasonal patterns vary across origin markets and tourism forms: for example, elderly tourists from Germany and the Netherlands contribute substantially to low-season tourism in Turkey [35]; cruise tourism in North America exhibits relatively weak seasonality [17]; in Estonia, popular destinations in different seasons may attract tourists from different origins or ethnic groups [15]; and in the UK, holiday travel shows the strongest seasonality concentrated in summer, VFR peaks in December, and business travel is comparatively stable with weaker seasonal fluctuations [19]. These studies have expanded the understanding of seasonality across segmented groups. Nevertheless, much of the segmentation remains based on external attributes such as origin, age, and travel mode, with relatively limited attention to internal dimensions such as behavioral motivations and lifestyle identities. For seasonal lifestyle tourists—who pursue a livable environment and engage in cyclical seasonal migration—although the phenomenon has been noted, systematic and quantitative research remains constrained by data availability, particularly with respect to their temporal dynamics and spatial distribution patterns.

2.4. Measurement Approaches: From Static Indices to Decomposition

Methodologically, tourism seasonality measurement has evolved from static descriptions to dynamic decomposition. Static indicators such as annual concentration ratios, seasonal intensity indices, and the Gini coefficient are intuitive and facilitate cross-regional comparisons [16,20,30], but they often have limited capacity to capture the dynamic evolution of seasonality. To address this, scholars have proposed moving-average-based seasonal indices, which better reflect temporal variation. Karamustafa et al. compared alternative measurement approaches and argued that moving-average seasonal indices can provide a more objective assessment and help interpret seasonal patterns [21]. In addition, decomposition approaches such as TRAMO/SEATS and X-12-ARIMA can separate a time series into trend, seasonal, and irregular components, thereby revealing finer-grained structures [17,18,36]. However, existing applications mainly serve macro-level descriptions of aggregate demand and are less frequently applied to behaviorally segmented groups such as seasonal lifestyle tourists or integrated with city/county-level spatial analysis. Thus, while the tools themselves are well established, their systematic use in segmented-market and micro-scale governance contexts remains relatively limited.

In summary, despite substantial progress in measuring tourism seasonality and identifying its drivers, three gaps remain. First, most studies rely on aggregate flows or macro-scale units, making it difficult to isolate the distinctive rhythms of long-stay seasonal lifestyle tourists as a segmented market. Second, static seasonality indicators have limited ability to characterize the dynamic evolution of seasonal intensity and its coupling with long-term trends, constraining the assessment of destination resilience and risk. Third, although time-series decomposition can extract seasonal and trend components, many applications remain largely descriptive and rarely integrate the two signals to evaluate sustainable destination development or statistically validate differences across destination types. Therefore, building on a city/county-level characterization of the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of seasonal lifestyle tourism, this study identifies and summarizes destination development types based on seasonal and trend-evolution characteristics.

To facilitate comparison across research objects/scales, data granularity, and methodological approaches, Table 1 summarizes representative studies on tourism seasonality, including their key findings and limitations.

Table 1.

Representative studies on tourism seasonality: objects/scales, methods, findings, and limitations.

3. Research Region, Data Sources, and Research Methods

3.1. Research Region

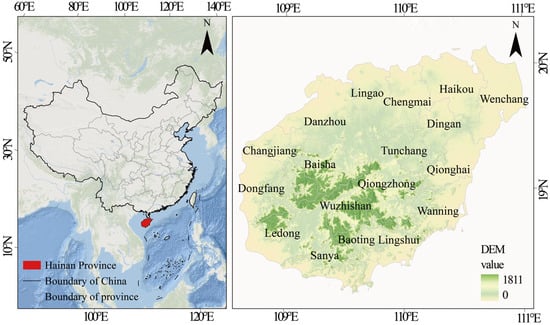

Hainan Province consists of 19 cities and counties (Figure 1). Due to the lack of publicly available tourism data and regulatory restrictions on tourism activities, Sansha City is excluded from this study, and the analysis focuses on the remaining 18 administrative units. Additionally, the type of tourism in Sansha City differs from seasonal lifestyle tourism, so its exclusion does not impact the core conclusions of this study. The island topography is dome-shaped, featuring low-lying edges and an elevated central section. Its landscape include mountains, hills, terraces, and plains arranged in a distinct stepped pattern. Mountains are concentrated in the south-central part of the island, while hills are mainly distributed inland and across the northwest and southwest. Terraces and steppe areas are typically located around the mountain and hill zones, with coastal plains encircling the island [37]. Benefiting from the ocean’s moderating influence, Hainan experiences warm winters and cool summers. Combined with warm coastal water and abundant sunshine, these conditions provide year-round suitability for sea bathing, sunbathing, and sandbathing [38].

Figure 1.

Location and DEM Map of Hainan Province.

Hainan’s unique geographical and climatic conditions have positioned it as one of China’s leading destinations for seasonal lifestyle tourists. According to statistics from the Hainan Provincial Political Consultative Conference, between 1 October 2017 and 30 April 2018, seasonal lifestyle tourists constituted approximately 17% of the island’s total registered population, underscoring its prominence as a prime destination [39]. However, tourism resources in Hainan are unevenly distributed across the province, with Haikou, Sanya, and Wenchang hosting the most abundant resources [40]. Consequently, differences in resource empowerment and regional development give rise to varying seasonal patterns and visitor preferences across cities and counties, further accentuating seasonal fluctuations among seasonal lifestyle tourists.

3.2. Data Sources

To assess the seasonal characteristics and cyclical fluctuations of an economic phenomenon, it is common to choose general indicators that are widely applicable, comparable, and capable of capturing overall patterns of economic activity. Hainan stands out as the only province in China that publicly releases official data on seasonal lifestyle tourists, providing a unique and authoritative basis for examining the seasonality and regional variations in seasonal lifestyle tourism. Accordingly, guided by the principles of data integrity, availability, and horizontal comparability, this study focuses on 18 cities and counties in Hainan Province (excluding Sansha City), and draws on data of monthly arrivals of seasonal lifestyle tourists spanning from January 2021 to December 2024.

The data on seasonal lifestyle tourists are obtained from the Hainan Provincial Department of Tourism, Culture, Radio, Film, and Sports (https://lwt.hainan.gov.cn/). According to the department’s definition, seasonal lifestyle tourists are individuals who travel away from their usual place of residence for purposes such as leisure, sightseeing, vacation, visiting relatives and friends, business, conferences, health and wellness, or cultural, sports, and religious activities. These tourists typically stay within the province for a period ranging from 21 days to a year, either in tourist accommodation, self-owned housing, or at the residences of relatives and friends, without employment being their primary motive.

The climate comfort index is derived from the daily surface climate data set (V3.0) provided by the National Climate Data Center of China. Data on wellness and leisure facilities are gathered through web scraping of Points of Interest (POI) information from the Gaode Map API. Road data is sourced from the Open Street Map platform. All other data originates from the 2023 Statistical Yearbook of Hainan Province. These data are included in the Analysis of variance to investigate whether there are significant differences in socioeconomic conditions and public services across the development types.

In addition to the official statistical data, this study also incorporates questionnaire survey data to supplement and corroborate the time-series analysis from a micro-behavioral perspective. The survey was conducted in January 2025 in major seasonal lifestyle tourism destinations in Hainan, targeting both short-stay visitors and seasonal lifestyle tourists. A mixed-mode approach was adopted, combining on-site paper-based questionnaires with online responses. In total, 292 questionnaires were collected; after data cleaning and validity screening, incomplete responses and questionnaires with substantial missing key items were removed, yielding 264 valid questionnaires (valid-response rate: 90%). Offline questionnaires were distributed and retrieved in areas such as coastal zones with high-quality landscape amenities and core urban districts with well-developed public service facilities, while online responses were obtained via tourism-related social media groups. The questionnaire covered respondents’ seasonal preferences, pull factors, and travel purposes. These survey data are used to compare the behavioral characteristics and demand profiles of the two visitor groups and to provide micro-level evidence supporting the temporal patterns identified in the official monthly statistics.

3.3. Research Methods

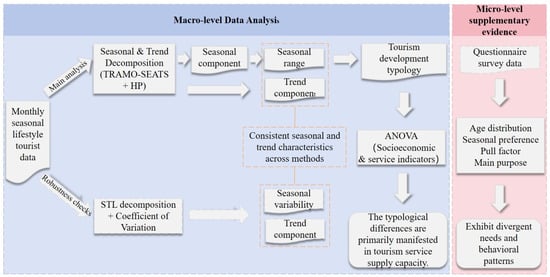

To improve the readability of the Methods section, Figure 2 summarizes the research workflow: at the macro level, monthly data are subjected to seasonal decomposition and trend extraction, which are then used to construct development types and to test between-type differences via ANOVA; meanwhile, STL decomposition and the coefficient of variation (CV) are employed as robustness checks. The orange dashed lines and arrows indicate the transition and connections between different analysis steps. Questionnaire data are incorporated as micro-level supplementary evidence to characterize tourists’ preferences and behavioral features.

Figure 2.

Framework Diagram of the Research Workflow.

3.3.1. TRAMO/SEATS

Time series data generally contains long-term trends, seasonal patterns, and random disturbances. To uncover underlying structure and eliminate noise, time series decomposition is often applied. This technique separates the data into trend, seasonal, and residual components, allowing for a clearer analysis of long-term dynamics and seasonal variations. Time series decomposition can be performed using either an additive or a multiplicative model. The additive model is appropriate when component fluctuations remain relatively constant over time, whereas the multiplicative model is more suitable when the magnitude of fluctuations changes vary over time [41]. This study adopts the multiplicative model.

Given that the study period covers only four years, we restrict the application of TRAMO/SEATS strictly to the identification of trend–seasonal structures, rather than using it for long-term forecasting or strong statistical inference. This practice is consistent with the recommendations of the ESS Seasonal Adjustment Guidelines (2024), which suggest that model-based methods may be used with caution for short series of 3–6 years [42]. A previous study has applied TRAMO/SEATS to time series of around seven years in length [17], using it primarily to characterize trend and seasonal structures rather than for advanced forecasting; moreover, some research comparing seasonal adjustment results based on 5-year and 8-year time spans has found that the shorter 5-year series performs better, indicating that a shorter time span is not necessarily inferior to a longer series [43]. On this basis, we further employ STL decomposition and coefficients of variation to test the robustness of the TRAMO/SEATS results, thereby reducing reliance on a single model.

To implement this method, this study used the TRAMO/SEATS program in EViews 13.Built on the TRAMO and SEATS modules, it is widely used in the processing and analysis of economic time series data. TRAMO provides regression modeling and preprocessing, addressing issues such as missing values, non-stationarity, and outliers. SEATS, based on the ARIMA framework, extracts signals from the time series and decomposes them into trend-cycle, seasonal, and irregular components. Compared to X-12-ARIMA, TRAMO/SEATS is easier to apply, requires less subjective input, and offers greater automation, making it a more robust and broadly applicable tool in practice [44].

- Additive model:

- Multiplicative model:

3.3.2. Hodrick-Prescott Filtering

Seasonal adjustment methods can decompose economic time series into components, but they do not distinguish between trend and cycle, treating them as a single element. This limitation makes it difficult to identify long-term trends. To address this, researchers often apply specialized techniques to decompose the series into distinct trend and cyclical components, with the Hodrick-Prescott filter being among the most popular choices.

The Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter, introduced by Hodrick and Prescott during their study of post-war economic fluctuations in the United States, has become a staple technique in economic cycle research. Its core function is to separate the low-frequency trend component from the high-frequency cyclical component. The HP filter assumes that the time series is composed of a trend component and a cyclical component [45], such that:

In Equation (3), t = 1, 2, 3, ……, T. The HP filter separates the series into its components. Typically, the unobservable trend component in the time series is defined as the solution to the following minimization problem:

In Equation (4), , when λ = 0, the trend series that solves the minimization problem is . As λ increases, the estimated trend becomes progressively smoother. If λ tends towards infinity, the estimated trend will converge to a linear function. According to convention and standard practice, λ = 14,400 is commonly used for monthly data to effectively smooth high-frequency noise while preserving long-term trends. Therefore, this study adopts λ = 14,400.

3.3.3. Analysis of Variance

Analyzing variance was conducted using an Analysis of variance (ANOVA), which is a statistical technique used to test whether the means of several populations differ significantly, thereby assessing the effect of a categorical independent variable on a continuous dependent variable. ANOVA can be categorized into one-way, two-way, and three-way. One-way ANOVA specifically tests whether the means of multiple groups defined by a single factor are equal [46]. In this study, one-way ANOVA is applied to examine whether significant differences exist among different development types.

3.3.4. Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Using Loess

STL (Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess) is a commonly used time-series decomposition method that employs robust locally weighted regression (LOESS) as the smoothing technique [47]. It decomposes a time series into trend, seasonal, and remainder components. Compared with other seasonal decomposition methods, STL is more robust to outliers and is particularly suitable for additive decomposition:

In Equation (5), denotes the tourist volume at time t, is the trend component at time t, is the seasonal component at time t, and is the remainder component at time t, t = 1, 2, ……, N. For time series with a multiplicative seasonal structure, a logarithmic transformation can first be applied to the original series to convert the multiplicative relationship into an additive one, after which STL can be used for decomposition.

4. Results

This section establishes a three-dimensional analytical framework encompassing “seasonal characteristics, development trends, and typological differentiation” to systematically reveal the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of Hainan’s lifestyle tourism market. Initially, seasonal decomposition models are applied to analyze the dynamic characteristics and spatial variations in intra-annual and inter-annual market fluctuations. Subsequently, HP filtering is employed to identify differentiated long-term development trajectories across regions. Finally, by integrating seasonal and trend indicators, a five-category typology—including Robust Development and Fluctuating Expansion types—is constructed. Analysis of variance confirms significant differences among these types in terms of tourism service facilities, while no statistically significant disparities are observed in fundamental elements such as the natural environment.

4.1. Seasonal Patterns in Hainan’s Seasonal Lifestyle Tourism Market

This section analyzes the seasonal patterns of Hainan’s lifestyle tourism market, focusing on the intra-annual fluctuations and multi-year seasonal changes across the island’s cities and counties. The analysis shows that Hainan’s seasonal structure follows a distinct “two peaks and one trough” pattern: the peaks occur in the winter and spring months, while the trough appears during the summer and autumn months. This seasonal variation is influenced by climatic factors, with the high season primarily attracting tourists seeking warm weather, while the low season coincides with high temperatures, heavy rainfall, and the risk of typhoons. However, there are significant regional differences in the timing, duration, and intensity of these seasonal patterns, reflecting variations in climate, resource endowment, and tourist demand. Over time, the seasonal amplitude has changed in some regions, with certain areas experiencing increased seasonal fluctuations, while others show a trend of decreasing volatility. Overall, although Hainan’s tourism market remains strongly seasonal, the intensity and structure of these fluctuations vary significantly across regions. Some areas exhibit more stable tourist flows, while others face greater risks due to concentrated seasonal demand.

4.1.1. Intra-Annual Seasonality Across Regions

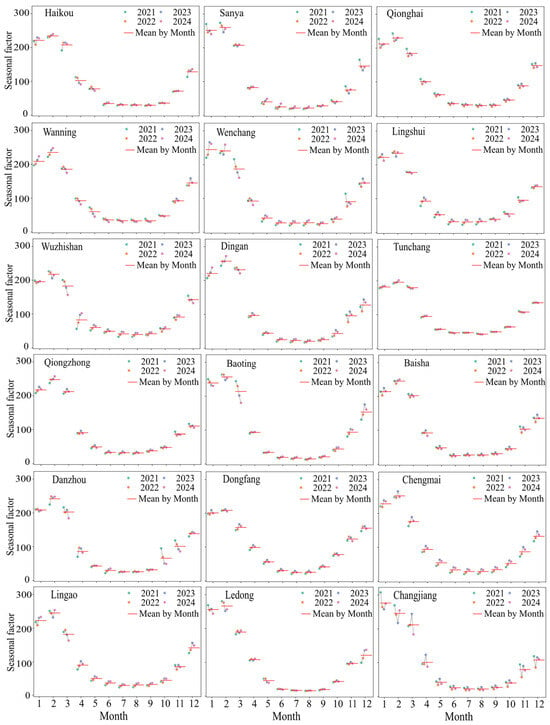

We employed the TRAMO/SEATS seasonal adjustment method to decompose the seasonal lifestyle tourism market in Hainan’s cities and counties into seasonal, trend-cycle, and irregular factors. This decomposition enables us to explore the market’s underlying seasonal structure. Seasonal factors were plotted monthly for each city and county, and their mean values were calculated to analyze the intra-annual fluctuation patterns.

The seasonal factors (SF) of Hainan’s lifestyle tourism market exhibit a clear annual “two peaks and one trough” pattern (Figure 3). Peaks occur from January to March and again in December, whereas the trough is concentrated between June and August. Using the four-year mean monthly SF, the within-year range (max–min across the 12 monthly means) varies substantially across cities/counties, from 153.35 in Tunchang to 253.89 in Changjiang, indicating pronounced spatial heterogeneity in seasonal intensity. Overall, monthly SF values across cities/counties span 14.78–276.06, further confirming strong seasonality. Interannual differences are relatively small during trough months, whereas peak-month dynamics diverge across cities/counties: Wanning, Wenchang, Ding’an, and Qiongzhong show an upward tendency, Sanya, Qionghai, Wuzhishan, Baoting, Ledong, and Changjiang show a downward tendency, while Haikou, Lingshui, Tunchang, Baisha, Danzhou, Dongfang, Chengmai, and Lingao remain relatively stable.

Figure 3.

Intra-annual fluctuations of seasonal factors in Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market.

The peak–trough structure of seasonal lifestyle tourism identified in this study is not consistent with the “three peaks and two troughs” pattern reported in earlier work based on monthly domestic tourist data for Sanya (1996–2001) [48].

The seasonality of each city and county has shifted over time, with the seasonal amplitude changing dynamically. Three major patterns were identified: (1) relatively stable seasonality with constant amplitude (Haikou, Sanya, Qionghai, Lingshui, Wuzhishan, Tunchang, Qiongzhong, Baisha, Danzhou, Dongfang, and Chengmai); (2) increasing seasonal amplitude over time (Wanning, Wenchang, Ding’an, and Lingao); (3) decreasing seasonal amplitude over time (Baoting, Ledong, and Changjiang). The third pattern is considered favorable, as declining seasonality can help ease problems such as resource shortages during peak months and low demand during off-seasons.

This study aims to pinpoint the patterns of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market by evaluating the seasonal factor (SF), where SF ≥ 105 indicates the peak season, 85 < SF < 105 indicates the shoulder season, and SF ≤ 85 indicates the low season [49]. As summarized in Table 2, for most cities/counties, the peak season concentrates in January–March and December (4 months), the low season typically spans May–October (6 months) and extends to November in several counties (7 months), and the shoulder season is generally short (1–2 months), most commonly occurring in April and/or November. The overall pattern shows a peak in winter and spring, and a low in summer and autumn in Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market. This pattern is closely related to tourist preferences and local climatic conditions: Hainan primarily attracts visitors seeking winter warmth and spring holidays, whereas adverse summer–autumn weather—such as high temperatures, heavy rainfall, and typhoons—may suppress travel demand, thereby contributing to a prolonged low season lasting about 6–7 months. Despite this shared rhythm, noticeable spatial differences remain across cities and counties. Moreover, in terms of peak–trough timing, this overall pattern is broadly consistent with the general findings reported in previous studies on inbound tourism seasonality [50].

Table 2.

Seasonal patterns of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market by city and county.

Despite this general pattern, significant spatial differences exist due to variations in resource endowment, climate conditions, and tourist sources. The seasonal structures of cities and counties can be categorized into four types: (1) long low season without shoulder season, such as Sanya, where the market shifts directly from a prolonged low season to a concentrated high season; (2) long high season with a single shoulder season, such as Tunchang, Dongfang, and Ledong, where the peak and low seasons are nearly equal in length, with only one transitional period; (3) short high season with dual shoulder seasons, such as Qionghai, Wanning, Wenchang, Lingshui, Ding’an, Qiongzhong, Baoting, Baisha, Danzhou, Chengmai, and Lingao, where two shoulder seasons appear but the low season is slightly longer overall; (4) long low season with a short shoulder season, e.g., Haikou, Wuzhishan, and Changjiang, where the shoulder season lasts only one month and the low season dominates.

To further examine market differences, the coefficient of variation (CV) of monthly SF across the 18 counties exceeds 20% during May–October, indicating substantial spatial heterogeneity even within the conventional low-season window, whereas variability is relatively smaller during the peak and shoulder seasons.

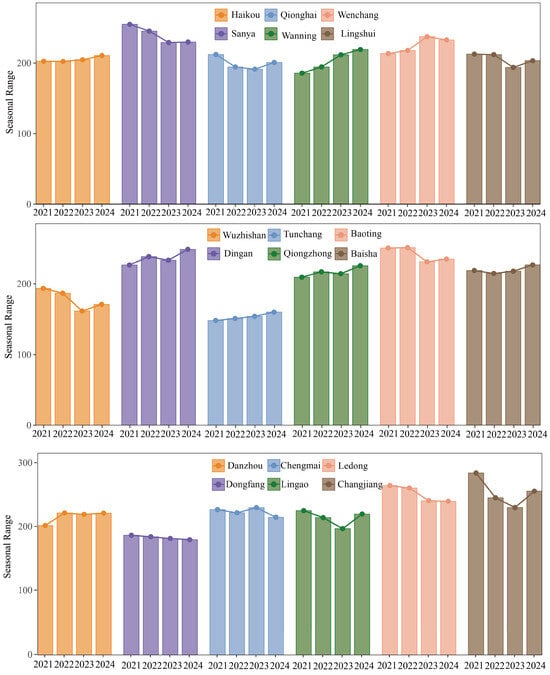

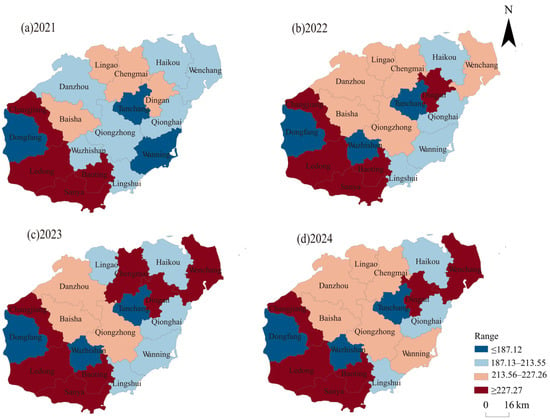

4.1.2. Multi-Year Seasonality of Hainan’s Seasonal Lifestyle Tourism Market

The seasonal range, defined as the difference between the maximum and minimum monthly seasonal factors within a year, reflects the intensity of seasonal influence on Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market [49]. Based on the city/county-level four-year mean seasonal range (2021–2024), the distribution is centered at a relatively high level (mean = 215.01, SD = 26.21; median = 216.60; Q1 = 203.97; Q3 = 231.20) and spans a wide range (153.35–254.33), indicating pronounced seasonality in Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market, though the magnitude of seasonal impact differs considerably across regions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Seasonal range of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market (2021–2024).

Tunchang consistently recorded the smallest seasonal range during the study period, suggesting relatively stable demand, weaker fluctuations, and a more balanced tourist distribution. In contrast, Changjiang exhibited the largest seasonal range in 2021 and 2024, while Ledong recorded the highest values in 2022 and 2023, both demonstrating highly concentrated seasonal demand. Across all cities and counties, seasonal ranges varied from 148.22 (Tunchang, 2021) to 284.78 (Changjiang, 2021), with the maximum nearly 1.92 times the minimum. Regions with larger seasonal ranges, such as Changjiang, Ledong, and Sanya show stronger intra-annual tourist concentration, indicating greater market volatility and potential risks. Conversely, areas with smaller seasonal ranges, including Wuzhishan, Dongfang, and Tunchang, demonstrate a more even tourist distribution, reduced sensitivity to seasonal fluctuations, and a more stable market structure.

The annual changes in seasonal range reveals the seasonal fluctuations trends Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market Figure 4 shows Haikou, Wanning, and Tunchang experienced a consistent yearly increase in their seasonal range, while Wenchang, Ding’an, Qiongzhong, Baisha, and Danzhou exhibited a fluctuating upward trend. This indicates a rising intra-annual seasonal concentration of tourism demand, which, over the long term, may worsen seasonal imbalances and hinder healthy market development. In contrast, Dongfang and Ledong experienced steady declines in seasonal range, while Sanya, Qionghai, Lingshui, Wuzhishan, Baoting, Chengmai, Lingao, and Changjiang showed fluctuating downward trends. These patterns suggest reduced volatility, contributing to greater market stability and supporting sustainable development.

Figure 4.

Seasonal range fluctuations of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism.

The spatial and temporal distribution of seasonal range is illustrated in Figure 5. Overall, the seasonal range exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity: high-value areas are mainly clustered in southern Hainan and remain relatively stable across years, whereas low-to-medium values are primarily distributed in the northern and western parts of the province. Specifically, Sanya and its surrounding southern counties generally fall into higher classes, while Haikou consistently remains in the lower class during the study period, indicating smaller intra-annual fluctuations and a comparatively smoother seasonal pattern. Notably, although both Haikou and Sanya are major destinations for seasonal lifestyle tourism, Haikou—as the provincial capital—has persistently lower seasonal ranges than the southern core areas, reflecting more stable year-round dynamics. During the study period, while the southern high-value clustering pattern largely persists, several northeastern counties (e.g., Wenchang) shift from low-to-medium to higher classes in later years, suggesting a northward expansion and localized intensification of the seasonal range.

Figure 5.

Spatial and temporal distribution of seasonal range.

4.2. Development Trends of Hainan’s Seasonal Lifestyle Tourism Market

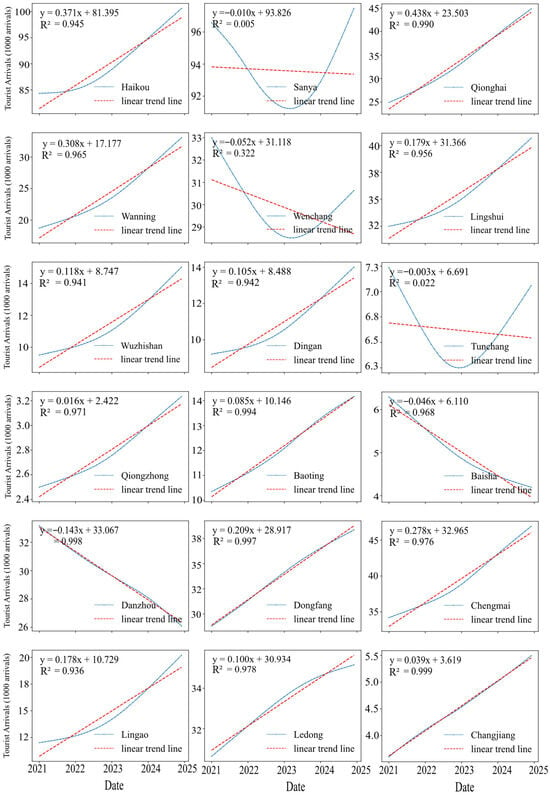

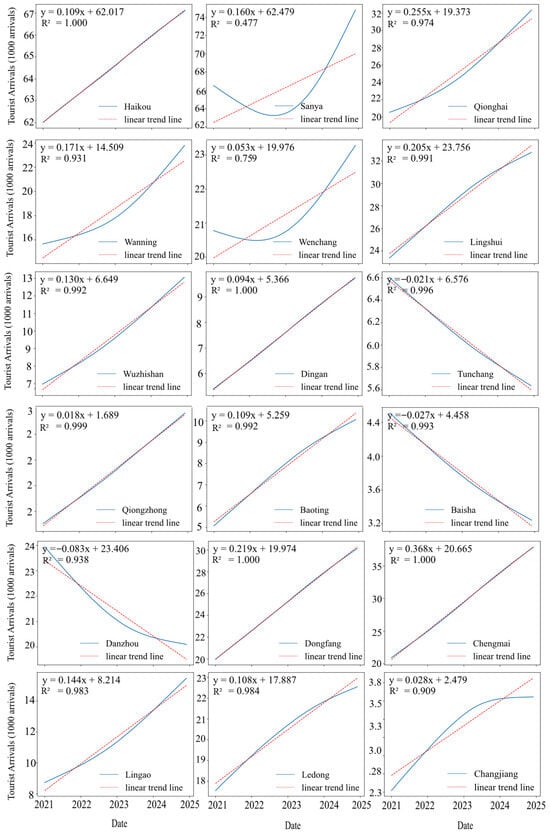

In this section, we apply the Hodrick-Prescott filter to break down the trend-cycle components for each city and county to explore long-term market trends. This analysis provides a foundational understanding for regional expansion tactics. The development trends of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market vary significantly across different cities and counties (Figure 6). Overall, the vast majority of cities/counties exhibit a sustained upward trajectory, indicating an overall expansion of market scale amid the post-pandemic recovery; meanwhile, a small number show declining paths, suggesting mounting market pressure and weakened growth momentum. Notably, Sanya, Wenchang, and Tunchang display a typical U-shaped recovery pattern: the trend component bottomed out around late 2022 to early 2023 and then gradually rebounded, indicating a certain degree of resilience after a short-term downturn. Taken together, the long-term trends across cities/counties include both steady-growth trajectories and declining or recovery pathways, implying that market evolution is not synchronized but instead follows differentiated development trajectories.

Figure 6.

Development trends of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market by city/county.

To facilitate cross-county comparison, Table 4 further summarizes the trend type, fitted linear slope (β), goodness-of-fit (R2), and the turning-point month for U-shaped trajectories for each city/county. The results show that monotonic growth dominates (13 of 18 cities/counties), with β ranging from 0.016 to 0.438 (1000 arrivals/month), indicating that most areas exhibit a stable long-term expansion trend. Qionghai records the fastest growth (β = 0.438, 1000 arrivals/month), approximately 27 times that of Qiongzhong (β = 0.016, 1000 arrivals/month). Declining trends are observed only in Baisha and Danzhou, with Danzhou showing the steepest decrease (β = −0.143, 1000 arrivals/month). In terms of model fit, linear trends perform well for most cities/counties outside the U-shaped group (generally high R2), suggesting that their long-term trajectories are relatively smooth and can be adequately summarized by a linear slope. By contrast, Sanya, Wenchang, and Tunchang exhibit markedly low R2 values (0.005–0.322), consistent with their non-linear recovery patterns; therefore, classifying them as U-shaped trajectories is more appropriate.

Table 4.

Trend types and fitted trend statistics for Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market (2021–2024).

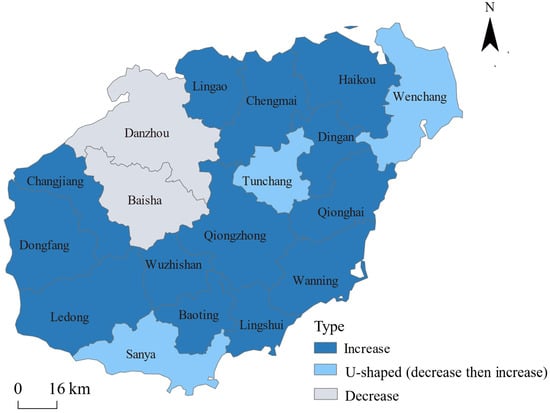

Figure 7 shows the development trends of cities and counties in Hainan Province. Baisha and Danzhou, both located in the central-western region, display a linear decline. Wenchang, Tunchang, and Sanya show U-shaped trends, with an initial decrease followed by recovery, spanning the northern, central, and southern parts of the province. The majority of cities and counties exhibit linear upward trends, reflecting overall market growth. The fastest-growing areas are concentrated in the north and east, including Haikou and Chengmai in the north, and Qionghai and Wanning in the east.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of development trends.

4.3. Development Types of Hainan’s Seasonal Lifestyle Tourism Market

According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), sustainable tourism development is defined as “meeting the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunities for the future.” Seasonality has long been recognized as one of the most critical challenges affecting sustainable tourism development, given its implications for resource allocation, economic stability, and market resilience [51,52]. Consequently, it is necessary to analyze not only the growth trajectory but also the structural balance within the annual cycle [53].

In this study, the seasonal lifestyle tourism markets are classified into five standard types by integrating information on seasonal range dynamics with long-term market trends. The seasonal range change rate (SR) measures the variation in seasonal amplitude between 2021 and 2024, calculated as:

where represents the observed value in month of year . A value of SR > 1 indicates stronger seasonality, as the seasonal range increases relative to the base year, whereas SR < 1 indicates weaker seasonality, reflecting a reduced seasonal range. To handle the boundary case, we treat SR = 1 as indicating no change in seasonality and group it together with SR ≤ 1.

The trend growth rate is derived from a linear trend model fitted to the monthly time-series data:

where is the observed value in month and is the trend coefficient. The coefficient reflects the overall direction of trend growth development. A positive indicates an raise trend, a negative indicates a downward trend, and when is near zero but Figure 6 shows a “decline recovery” pattern along with low , the trend is classified as U-shaped.

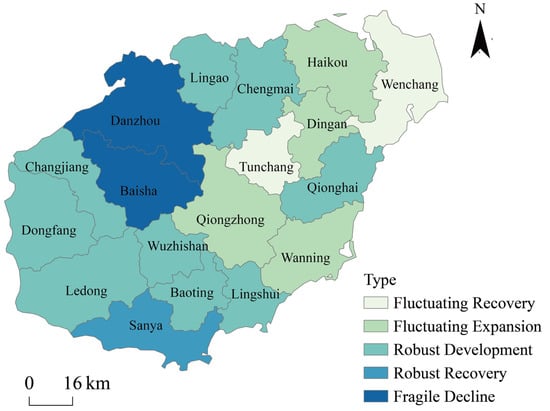

The classification framework is defined in Table 5. The Robust Development type is characterized by an increasing trend (β > 0) and non-increasing seasonality (SR ≤ 1); the Fluctuating Expansion type by an increasing trend (β > 0) and strengthened seasonality (SR > 1); the Robust Recovery type by a U-shaped trend and non-increasing seasonality (SR ≤ 1); the Fluctuating Recovery type by a U-shaped trend and strengthened seasonality (SR > 1); and the Fragile Decline type by a declining trend (β < 0) and strengthened seasonality (SR > 1).

Table 5.

Development types of the seasonal lifestyle tourism market.

The spatial distribution of development types in Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market reveals distinct regional patterns (Figure 8). The Robust Development Type accounts for 50% of Hainan’s cities and counties, showcasing an extensive spatial presence throughout the island and signifying a well-balanced and healthy growth pattern in most areas. The Fluctuating Expansion Type shows rapid trend growth coupled with an increasing seasonal range fluctuation, suggesting intensified seasonal disparities in tourism demand. The Robust Recovery Type, represented by Sanya, a key southern tourism hub, experienced a modest decline in 2023 but resumed growth while maintaining a stable intra-annual seasonal structure throughout. The Fluctuating Recovery Type, which includes Wenchang and Tunchang, demonstrates both erratic trend movements and a skewed intra-annual seasonal structure. Lastly, the Fragile Decline Type, observed in some western regions, is under the dual challenge of diminishing demand and expanding seasonal gaps.

Figure 8.

Development types of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market by city/county.

We employed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test for significant differences among the five defined development types concerning natural environment, socioeconomic conditions, tourism services, and public service facilities. The design of this indicator system closely aligns with the core demands of seasonal lifestyle tourists: the Natural Environment Dimension (climate, air quality) reflects the environmental drivers of seasonal lifestyle tourists [54,55]; the Socioeconomic Dimension (GDP, urbanization rate) delineates urban function and living convenience [56,57]; the Tourism Service Dimension (star-rated hotels, health/wellness facilities) directly corresponds to the demand for long-stay and health/wellness conditions [58,59]; and the Public Service Dimension (medical institutions, traffic accidents) gauges the basic assurance and safety concerns of this population [60,61]; The Transportation Network Dimension (density of main roads and railways) captures the accessibility and everyday mobility conditions experienced by seasonal lifestyle tourists [62,63]. It is worth noting that this set of indicators should be understood as a background test of structural differences in the macro conditions of the seasonal lifestyle tourism market, constructed under a demand-oriented perspective while balancing parsimony and data availability. Therefore, it is not intended to constitute an exhaustive explanatory model that covers all potential dimensions of destination attractiveness.

The one-way ANOVA results in Table 6 indicate that, at the 5% significance level, most indicators show no statistically significant differences across the five development types, except for tourism-service-related measures. Specifically, in terms of the natural environment, neither climate comfort (F = 1.021, p = 0.433, η2 = 0.239) nor air quality (F = 0.736, p = 0.583, η2 = 0.185) differs significantly among types. Regarding socioeconomic conditions, GDP (F = 0.820, p = 0.535, η2 = 0.201), year-end resident population (F = 0.801, p = 0.546, η2 = 0.198), and urbanization level (F = 0.609, p = 0.663, η2 = 0.158) are also not significantly different. Public-service indicators likewise show no significant between-type differences, including the number of healthcare institutions (F = 0.884, p = 0.501, η2 = 0.214) and traffic accidents (F = 0.451, p = 0.770, η2 = 0.122). For the transport network, neither main road network density (F = 0.642, p = 0.642, η2 = 0.165) nor railway network density (F = 0.476, p = 0.753, η2 = 0.128) is significant.

Table 6.

Analysis of variance among different tourism development types.

In contrast, tourism-service indicators show more pronounced differences across development types and larger effect sizes. The number of star-rated hotels differs significantly among types (F = 3.658, p = 0.033, η2 = 0.530), and the number of overnight visitors exhibits an even stronger type effect (F = 6.787, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.676). The number of resorts and wellness facilities is only marginally significant (F = 3.064, p = 0.055, η2 = 0.485), suggesting relatively weaker statistical evidence for this indicator. Table 7 reports the mean values of the significant tourism-service indicators across development types. The results show that the Robust Recovery type ranks highest in both star-rated hotels and overnight visitors, whereas the Fragile Decline type ranks lowest; the remaining types form an overall decreasing gradient, in the order of Fluctuating Recovery, Robust Development, and Fluctuating Expansion. Overall, the ANOVA results indicate that the proposed typology primarily captures systematic differences in tourism-service supply capacity rather than in natural endowments, baseline socioeconomic conditions, or public-service provision, thereby providing empirical support for subsequent type-specific policy recommendations.

Table 7.

Mean values for significant tourism-service indicators across development types.

4.4. Robustness Checks

Given the relatively short study period, we employ the coefficient of variation (CV) as an auxiliary validation metric to ensure the robustness and reliability of the seasonal decomposition results. For each city and county, we calculate the annual CV of monthly seasonal lifestyle tourist data for the years 2021–2024 (Table 8). The validation results show that, in most jurisdictions, the annual trend of the CV is highly consistent with the annual trend of the seasonal range obtained from time series decomposition.

Table 8.

Coefficient of Variation of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market (2021–2024).

To further assess the robustness of the seasonal adjustment results, particularly the reliability of the long-term trend component, we introduce the STL decomposition method as a complementary validation tool for TRAMO/SEATS. STL (Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess) is a nonparametric decomposition approach based on Loess smoothing, with a notable advantage of strong robustness in the presence of outliers and local fluctuations. Specifically, we apply the STL method to decompose the monthly seasonal lifestyle tourist data for each city and county over the period 2021–2024, and extract the corresponding long-term trend component (Figure 9). The results show that, in the vast majority of cities and counties, the long-term trend obtained from STL is highly consistent with the trend component derived from TRAMO/SEATS in terms of overall shape, turning points, and direction of change. In other words, the two methods yield convergent and mutually corroborative conclusions regarding trend identification.

Figure 9.

Trend component of Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market based on STL decomposition.

Taken together, the coefficient of variation and the STL decomposition provide complementary robustness checks for the TRAMO/SEATS-based time series decomposition. The former focuses on the magnitude of seasonality and its interannual variation, whereas the latter concentrates on the shape and direction of the long-term trend-cycle component. In most cities and counties, these two sets of robustness checks yield highly consistent and mutually reinforcing conclusions, indicating that both the seasonal patterns and long-term development trends identified under the post-pandemic short-series context are reasonably stable and credible. Methodologically, this dual robustness assessment strengthens the reliability of the subsequent regional classification and policy analysis based on the seasonality and trend dimensions.

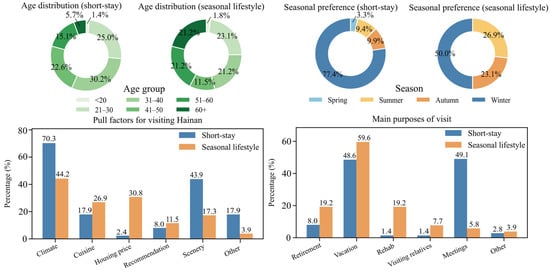

4.5. Behavioral Differences and Demand Profiles

At the micro level, the questionnaire results provide strong behavioral evidence in support of the above time-series patterns. The findings show that seasonal lifestyle tourists and short-stay visitors differ significantly in terms of seasonal preference, pull factors, and travel purposes (Figure 10). Although both groups clearly prefer to visit Hainan in winter, short-stay visitors exhibit a much higher concentration in the winter season, reflecting more pronounced seasonal fluctuations. By contrast, seasonal lifestyle tourists still display a non-negligible preference for summer and autumn, indicating a greater tendency to schedule or extend their stays over a longer time window. In terms of pull factors, short-stay visitors are primarily driven by climate and scenery, reflecting a typical sightseeing-oriented, short-term vacation profile. Seasonal lifestyle tourists, however, are more sensitive to housing prices, food, and other factors related to the cost of living and everyday residential experience, revealing a stronger “lifestyle-oriented” and “long-term residence” orientation. Differences in demographic structure and travel purposes are even more evident: among seasonal lifestyle tourists, the proportions of retirement and health/rehabilitation as main purposes are substantially higher than among short-stay visitors, and the share of middle-aged and older respondents is also markedly greater.

Figure 10.

Comparison of seasonal lifestyle tourists and short-stay visitors.

Taken together, these survey results clearly indicate that seasonal lifestyle tourists are not simply a subset of general overnight visitors, but rather a distinct market segment whose core concerns center on long stays, health and wellness, and quality of life. Their behavioral decisions are driven mainly by relatively stable factors such as climate, cost of living, and access to health and wellness resources, rather than short-term events or temporary policy changes. This behavioral profile is consistent with the “winter–spring peak, summer–autumn trough” pattern and the relatively stable seasonal and long-term trends identified in the official time-series data, and it provides an important behavioral mechanism for interpreting the spatiotemporal evolution of the seasonal lifestyle tourism market.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

Based on monthly seasonal lifestyle tourism data for 18 cities/counties in Hainan from 2021 to 2024, this study yields the following key conclusions:

First, Hainan’s seasonal lifestyle tourism market exhibits a stable intra-annual pattern characterized by “winter–spring peaks and a summer–autumn trough”: the peak season is concentrated in January–March and December, while the low season generally spans May–October and extends to November in some cities/counties. This indicates that, during the study period, the segment follows a clear and relatively predictable seasonal rhythm.

Second, the intensity of seasonality displays pronounced spatial heterogeneity at the city/county level. Overall seasonal amplitude remains relatively high with substantial regional disparities, and interannual changes are not uniform, as some jurisdictions show increasing seasonal concentration whereas others exhibit declining volatility or relative stability.

Third, long-term trends are upward on the whole but markedly differentiated: most cities/counties experience sustained growth during the study period, yet declining trajectories and U-shaped recoveries coexist, suggesting that expansion and recovery dynamics are not synchronized across the island.

Fourth, the five development types constructed by combining trend changes and seasonal-amplitude changes reveal clear inter-county differentiation. The Robust Development type accounts for the largest share, while the Fluctuating Expansion, Fluctuating Recovery, and Fragile Decline types indicate that some areas still face structural issues such as widening seasonal gaps or weakening demand. One-way ANOVA further shows that between-type differences are concentrated in tourism service supply and reception capacity, whereas no significant differences are observed in basic conditions such as the natural environment.

In addition, robustness checks and the questionnaire survey provide complementary support for these findings from the perspectives of macro-level temporal consistency and micro-level behavioral differences, respectively.

5.2. Contributions and Limitations

The seasonal lifestyle tourism market identified in this study exhibits a clear intra-annual “two peaks–one trough” structure, which is not consistent with the “three peaks–two troughs” seasonality pattern reported in earlier work based on sightseeing tourism in Sanya [48]. At the same time, in terms of the overall peak–off-peak timing, the “winter–spring peak and summer–autumn trough” pattern revealed here is consistent with the generalized conclusions reported in studies on inbound tourism seasonality [50]. This discrepancy may be related to differences in the seasonal drivers associated with tourist type and length-of-stay patterns. It should be emphasized that these studies differ in research objects, time periods, and statistical definitions; therefore, the peak–trough structures are not directly comparable on a one-to-one basis. Rather than simply negating or replacing existing findings, the purpose of this study is to refine the analysis to the city/county scale under a consistent time window and statistical definition, thereby characterizing the intra-island differentiation of this market segment. In addition, because our sample covers the post-pandemic recovery phase, differences from pre-2020 studies may partly reflect rebound effects and transitional demand adjustments, and should be interpreted accordingly.

The study’s novelty first lies in its focused research object: it shifts from aggregate visitor flows to seasonal lifestyle tourists as a long-stay market segment, allowing seasonality analysis to better reflect the demand and supply constraints associated with quasi-residential stays and helping to fill the gap of quantitative evidence for this group. Second, by downscaling the analysis to 18 cities/counties in Hainan, the study demonstrates that seasonal intensity and long-term trends do not evolve synchronously within the island, and that spatial differences are particularly pronounced during the low-season window, providing finer-grained evidence for differentiated resource allocation and low-season strategy design within the province. Third, the study evaluates seasonal and trend components in parallel based on monthly time-series decomposition, constructs five development types by combining seasonal- and trend-related changes, and applies one-way ANOVA to test differences across types. The results indicate that type differentiation is primarily associated with tourism service supply and reception capacity rather than basic conditions such as the natural environment, thereby directing policy attention toward adjustable levers such as service provision and low-season product systems. The Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model conceptualizes destination evolution around changes in visitor volumes, typically summarizing development into stages such as exploration, involvement, consolidation, and stagnation, which may further lead to decline or rejuvenation [64]. In recent years, this framework has remained widely used in contemporary tourism research and has been further extended in contexts such as shocks and recovery [65,66,67]. Against this backdrop, this study separates long-term trends from seasonal fluctuations using monthly data, providing finer temporal granularity for identifying seasonal structure and long-term trajectories, and offering dynamic evidence to support stage identification and governance assessment of strongly seasonal destinations from a life-cycle perspective.

In terms of strengths, this study builds a systematic, comparable evidence base using official monthly city/county data, enabling intra-island differences to be identified and presented under a consistent statistical definition. Methodologically, the coefficient of variation (CV) and STL decomposition serve as complementary robustness checks and cross-validation, indicating that the main identified patterns are relatively stable in a short time-series context. Moreover, after constructing the development typology, the study employs ANOVA to test between-type differences and finds that significant differences are concentrated in controllable dimensions such as tourism service supply and reception capacity, while differences in basic conditions such as the natural environment are not significant, strengthening the evidential basis and policy orientation of the typology. Meanwhile, the questionnaire survey provides supplementary micro-level evidence on differences between seasonal lifestyle tourists and short-stay visitors in seasonal preferences, pull factors, and travel purposes, offering behavioral support for the seasonal rhythm observed in the macro time series.

This study also has several limitations. First, because official statistics on “seasonal lifestyle tourists” have only been published since 2021, although robustness checks help enhance reliability, the ability to depict longer-term life-cycle stages and structural turning points remains limited. Second, the statistical associations revealed by ANOVA cannot establish causality or fully explain underlying mechanisms; the pathways linking supply capacity, demand preferences, and institutional factors require stronger causal identification strategies and finer-grained data for validation. Third, the lack of mobile signaling data, interviews, and comparable data with the same definition from other regions constrains cross-regional comparisons and assessments of external validity.

5.3. Practical Implications

The pronounced regional differentiation of seasonal lifestyle tourism in Hainan suggests that peak–off-peak regulation should not rely on a one-size-fits-all approach. Based on the identified city/county development types, this study proposes differentiated strategies (Table 9), providing operational zoning guidance for resource allocation and low-season product provision, and thereby improving the targeting and efficiency of low-season governance. At the practical level, some local initiatives are broadly consistent with the low-season governance logic proposed in this study and show certain positive signals. For example, the Sanya West Island Eco-Art Festival was held continuously from June to October 2024, which may help extend the tourism activity cycle and enrich the portfolio of low-season products; during the festival period, Sanya’s seasonal index ranks relatively high in same-month comparisons within the sample period. Likewise, the Hainan Island Carnival was moved from winter to summer for the first time in 2024, with Danzhou hosting the closing ceremony; same-month comparisons indicate that Danzhou’s seasonal index in June 2024 reached the highest level among June observations from 2021 to 2024. It should be noted that these observations do not constitute strict causal evidence, but they provide a practical reference for a governance pathway in which branded festivals and low-season product supply are used to enhance low-season attractiveness and improve the structure of visitor flows.

Table 9.

Strategies for Different Tourism Development Types.

5.4. Future Research Directions

Building on the limitations discussed above, future research could proceed in the following directions: (1) integrating multi-source data (e.g., tourist expenditure data, mobile signaling data, and interview materials) to deepen the analysis of tourist behavior and market dynamics, thereby characterizing the seasonal evolution of supply–demand interactions more precisely; (2) introducing panel data and causal inference models to further identify the key drivers of seasonal fluctuations and to disentangle the seasonal elasticities of demand and supply; and (3) conducting cross-regional or cross–climate-zone comparative studies to examine seasonality patterns across destinations with different climatic conditions and development stages. Despite data constraints, this study provides valuable empirical insights into seasonal lifestyle tourism and lays a foundation for subsequent research. With longer time spans and broader spatial coverage, future studies are expected to further validate and extend the conclusions of this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Y. and X.Y.; methodology, C.W.; software, C.W.; validation, C.W.; formal analysis, C.W.; resources, C.W., W.Y. and X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, W.Y., X.Y., C.L. and F.A.; visualization, C.W.; funding acquisition, W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is under the auspices of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72061137072) and the Dutch Research Council (482.19.607).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by Institution Committee due to Legal Regulations (the Measures for Ethical Review of Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (2023)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is sourced from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Radio, Television and Sports of Hainan Province (https://lwt.hainan.gov.cn/) and the Hainan Provincial Bureau of Statistics (https://stats.hainan.gov.cn/tjj/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, H.; Wu, D.C. A Critique of Tourism-Led Economic Growth Studies. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Cárdenas-García, P.J. Analyzing the Bidirectional Relationship between Tourism Growth and Economic Development. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Muñoz, D.R.; Medina-Muñoz, R.D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, F.J. The Impacts of Tourism on Poverty Alleviation: An Integrated Research Framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 270–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, A.; Song, H. Does Tourism Support Supply-Side Structural Reform in China? Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L.S.; Kingma, H.L. Seasonal Migration of Retired Persons: Estimating Its Extent and Its Implications for the State of Florida. J. Econ. Soc. Meas. 1989, 15, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.M.; Musa, G. Retirement Motivation among ‘Malaysia My Second Home’ Participants. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiló, E.; Alegre, J.; Sard, M. The Persistence of the Sun and Sand Tourism Model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmatov, R.; Fernandez, X.L.; Coto Millán, P.P. The Change of the Spanish Tourist Model: From the Sun and Sand to the Security and Sand. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1650–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Bai, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, H. Mitigation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Nitrogen Losses Caused by Migration and Tourism in China’s Tropical Island Cities. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutty, M.; Scott, D.; Matthews, L.; Burrowes, R.; Trotman, A.; Mahon, R.; Charles, A.; Rutty, M.; Scott, D.; Matthews, L.; et al. An Inter-Comparison of the Holiday Climate Index (HCI:Beach) and the Tourism Climate Index (TCI) to Explain Canadian Tourism Arrivals to the Caribbean. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeeu, A.; Ramos, D.L.; Rahim, A.B.A. Measuring Seasonality in Maldivian Inbound Tourism. J. Smart Tour. 2022, 2, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Xin, L.; Cao, J.; Wu, Z. The Impact of an Ageing Population on Domestic Tourism. J. Simul. 2022, 10, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Rudihartmann. Tourism, Seasonality and Social Change. Leis. Stud. 2006, 5, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Hagen, L. Responses to Seasonality: The Experiences of Peripheral Destinations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahas, R.; Aasa, A.; Mark, Ü.; Pae, T.; Kull, A. Seasonal Tourism Spaces in Estonia: Case Study with Mobile Positioning Data. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćorluka, G.; Vukušić, A.; Kelić, I. Measuring Tourism Seasonality: Application and Comparison of Different Methods. In Proceedings of the Tourism & Hospitality Industry 2018: Congress Proceedings, Faculty of Tourism & Hospitality Management, University of Rijeka, Opatija, Croatia, 26–27 April 2018; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Wu, X.; Feng, X. Cruise Tourism Seasonality: An Empirical Study on the North American Market. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, E.; Altinay, G. An Analysis of Seasonality in Monthly per Person Tourist Spending in Turkish Inbound Tourism from a Market Segmentation Perspective. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Morales, A.; Cisneros-Martínez, J.D.; McCabe, S. Seasonal Concentration of Tourism Demand: Decomposition Analysis and Marketing Implications. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Morales, A.; Mayorga-Toledano, M.C. Seasonal Concentration of the Hotel Demand in Costa Del Sol: A Decomposition by Nationalities. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamustafa, K.; Ulama, S. Measuring the Seasonality in Tourism with the Comparison of Different Methods. EuroMed J. Bus. 2010, 5, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M.; Lo Magno, G.L.; De Cantis, S. Measuring Tourism Seasonality across European Countries. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, G.; Platania, M. Islands’ Tourism Seasonality: A Data Analysis of Mediterranean Islands’ Tourism Comparing Seasonality Indicators (2008–2018). Sustainability 2024, 16, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.J. The All-Season Opportunity for Canada’s Rosorts. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1994, 35, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Lundtorp, S. (Eds.) Seasonality in Tourism, 1st ed.; Advances in Tourism Research Series; Pergamon: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; ISBN 978-0-08-051680-6. [Google Scholar]

- Andolina, C.; Signa, G.; Tomasello, A.; Mazzola, A.; Vizzini, S. Environmental Effects of Tourism and Its Seasonality on Mediterranean Islands: The Contribution of the Interreg MED BLUEISLANDS Project to Build up an Approach towards Sustainable Tourism. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 8601–8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponi, V. The Economic and Environmental Effects of Seasonality of Tourism: A Look at Solid Waste. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 192, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Dai, L.; Wu, B. Analysis on the Features and Causes of Seasonality in Rural Tourism: A Case Study of Beijing Suburbs. Prog. Geogr. 2012, 31, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zhu, H. Review on Seasonality in Tourism Abroad. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 25, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.A. Seasonality of Hotel Demand in the Main Spanish Provinces: Measurements and Decomposition Exercises. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snepenger, D.; Houser, B.; Snepenger, M. Seasonality of Demand. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 628–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, M.; Dodds, R.; Butler, R. Introduction to Special Issue on Island Tourism Resilience. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. From insularity, archipelago to aquapelago: Research progress on island studies under the relational turn. J. Nat. Resour. 2025, 40, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Olya, H.G.T.; Maleki, P.; Dalir, S. Behavioral Responses of 3S Tourism Visitors: Evidence from a Mediterranean Island Destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Martin, D. Tourism Life Cycle and Sustainability Analysis: Profit-Focused Strategies for Mature Destinations. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccia, T.; Rizzo, I. Tourism Seasonality in Cultural Destinations: Empirical Evidence from Sicily. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y. An Estimation and Development Model of Tourism Resource Values at the Township Scale on Hainan Island, China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P. Evaluation on Climate for Tourism and Its Influence in Hainan Island. Master’s Thesis, Hainan Normal University, Haikou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hainan Daily Properly Treat and Effectively Utilize ‘Seasonal Migratory Talent’. Available online: https://www.zmgrc.gov.cn/show-13984.html (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Zhang, S.; Ju, H. The Regional Differences and Influencing Factors of Tourism Development on Hainan Island, China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y. The Historical Evolution and New Development Trend of Seasonal Adjustment Method. Stat. Res. 2015, 32, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Statistical Office of the European Union. ESS Guidelines on Seasonal Adjustment: 2024 Edition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; ISBN 978-92-68-15943-9. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, T.; Mirică, A.; Glăvan, I.-R.; Ferariu, G.A.; Radulescu-George, I.M. Seasonal Adjustment of Tourism Data for Romania Using JDemetra+. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Applied Statistics 2019, Bucharest, Romania, 8–9 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, V.; Maravall, A. Seasonal Adjustment and Signal Extraction Time Series. In A Course in Time Series Analysis; Peña, D., Tiao, G.C., Tsay, R.S., Eds.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 202–246. ISBN 978-0-471-36164-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hodrick, R.J.; Prescott, E.C. Postwar U.S. Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation. J. Money Credit Bank. 1997, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; He, X.; Jin, Y. Statistics, 6th ed.; Renmin University of China: Beijing, China, 2015; ISBN 978-7-300-20309-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, R.B.; Cleveland, W.S.; McRae, J.E.; Terpenning, I. STL: A Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Procedure Based on Loess. J. Off. Stat. 1990, 6, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Xuan, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D. An Approach to Seasonality of Tourist Flows Between Coastland Resorts and Mountain Resorts: Examples of Sanya, Beihai, Mt. Putuo, Mt. Huangshan and Mt. Jiuhua. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2002, 57, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Feng, X. On the Seasonal Characteristics, Fluctuation Cycle and Development Trends of Shanghai’s Inbound Tourist Market: Based on X-12-ARIMA and HP Filter Methods. Tour. Sci. 2016, 30, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, L. A Study of the Character of Hainan Inbound Tourism Seasonal and Regulation Measures. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 28, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, G.; Hetherington, A.; Inskeep, E. Sustainable Tourism Development: Guide for Local Planners, 1st ed.; A Tourism and the Environment Publication; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1993; ISBN 978-92-844-0038-6. [Google Scholar]

- Duro, J.A.; Turrión-Prats, J. Tourism Seasonality Worldwide. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Martínez, J.D.; McCabe, S.; Fernández-Morales, A. The Contribution of Social Tourism to Sustainable Tourism: A Case Study of Seasonally Adjusted Programmes in Spain. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnes, A.M.; Williams, A. Older Migrants in Europe: A New Focus for Migration Studies. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2006, 32, 1257–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Liu, S.; Zhou, J.; Li, N.; Long, W.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Yang, B.; Xue, P. Effect of Natural Environmental Changes on Hainan Migratory Population with Hypertension in China and Related Plasma Metabolism Features. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, R.; Suardi, S.; Ji, C.; Hanyu, Z. Is Urbanization the Link in the Tourism–Poverty Nexus? Case Study of China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3357–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]