Abstract

Education and post-licencing training programmes for novice drivers are widely implemented to improve road safety, yet their effectiveness remains debated. This study evaluates short-term attitudinal changes relating to participation in a mandatory post-licencing training programme for novice drivers in Slovenia. A within-subject pre–post survey methodology was used to evaluate self-reported driving attitudes across six safety-related domains among 225 novice drivers at a Slovenian driving training centre in 2024. Paired t-tests revealed minor yet statistically significant improvement following the programme in perceived support for the additional driver training, lowered overconfidence, heightened care in speeding and intersection behaviour, and enhanced attitudes towards vehicle operation and utilization of safety equipment. Attitudes regarding attention and adherence to traffic regulations showed negligible shifts, indicating a strong baseline attitude towards safe driving. The findings indicate a modest but fairly consistent short-term change in attitudes after programme participation. Due to the lack of a control group and dependence on self-reported data, the findings should be seen as evaluative rather than causative, necessitating more longitudinal and behavioural research to evaluate long-term and behavioural effects.

1. Introduction

Road transport is integral to our daily lives, enabling economic development, community integration, and access to basic needs such as education, healthcare, and commerce. Nevertheless, road transport also brings challenges, especially in safety. Traffic accidents have become a global concern that requires constant efforts to prevent and control them, since over 1.3 million people worldwide still lose their lives in traffic accidents, and moreover, 20 to 50 million people suffer non-mortal damages, sometimes leaving them disabled [1]. The same trend is evident in the EU as well, since about 20,600 people died from traffic accidents in 2022, which is a 3% increase in comparison to the previous year [2]. It is nearly impossible to estimate the damages and consequences that these accidents cause, since they do not only include the costs of healthcare and material costs, but they also incur damages such as reduced abilities for work, inability to perform daily functions, direct and indirect medical and rehabilitation costs, costs of insurance, police work, etc. Depending on the country, it is estimated that these costs can be as high as 1% to up to 3% of the total gross domestic product [1]. As Wijnen et al. [3] find, the average costs of EU countries’ traffic accidents amount to 0.4–4.1% of the EU’s gross domestic product, and they estimate that, for example, the direct and indirect costs of one death, caused by a traffic accident, amount to from 0.7 to 3.0 million EUR. The costs of a severe injury amount to 2.5% to 34.0% of the costs of lethal traffic accidents (28,000–959,000 EUR), while the costs of more minor injuries amount to 0.03% to 4.2% of the cost of a lethal traffic accident (296 EUR to 71,740 EUR) [4].

Consequently, traffic safety is one of the utmost concerns of the EU, which is preparing a new EU-wide action plan for traffic safety. Its main goal is to reduce the number of deaths on EU roads and to encourage its members to ensure that their systems will, among other tasks, encourage or even demand various programmes for additional driving education (e.g., a requirement for additional training for safe driving for younger drivers or drivers with a history of risky driving) [5].

This is of utmost importance, especially given that the trend involves lowering the age requirements for beginner drivers of personal and heavy freight vehicles, as set out in the last recommendations from the EU [6]. Globally, young novice drivers exhibit a significantly higher incidence of injury and fatality in vehicular accidents than their older, more experienced driver counterparts, and are frequently characterized as high-risk, exhibiting driving behaviours that increase susceptibility to road traffic accidents. Novice drivers are particularly susceptible to road traffic accidents due to their lack of experience and inattention [7], which is confirmed by Gifty et al. [8] who find that key contributory factors to accidents among young adults include inexperience, mobile phone distractions, excessive speed, and inadequate hazard recognition. Hu et al. [9] found that drivers aged 18–30 years are more likely to cause accidents than other age groups. This is also confirmed by Klauer et al. [10], who show that inexperienced drivers have been found to have a higher risk of crashes and near-crashes compared to experienced drivers.

Studies have shown that the inexperience of younger drivers often results in the errors that are typically made by them [11]. Therefore, novice drivers must gain as much on-road driving experience as possible, although this exposure also puts them at risk on the road [12]. Additionally, the severity of traffic accidents involving novice drivers can be influenced by various factors, including driving behaviour and skills [13]. The lack of driving skill can be demonstrated in different ways, for example, in the differences in eye movement and scanning behaviour during driving. Wallis and Horswill [14] found that experienced drivers are flexible in adapting their eye-scanning patterns to different road types and traffic situations. In contrast, novice drivers are inflexible and exhibit longer fixation durations.

In addition to the identified potential behavioural and perceptual deficits in novice drivers, several established psychological frameworks can help explain why post-licensure educational interventions may influence novice driver attitudes. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) suggests that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control shape drivers’ intentions and subsequent driving behaviour [15]. Risk detection and a lack of the ability to assess their own skills point to a mismatch between perceived and actual skills that is common among young and inexperienced drivers [16]. Social Cognitive Theory, as developed by Bandura, emphasizes learning through experience and feedback through the social environment [17], while cognitive-load and attentional models explain why novice drivers are potentially particularly vulnerable to reduced hazard perception [18]. Together, these frameworks provide a coherent conceptual rationale for targeting attitudes, risk perception, and self-evaluation as potential and proximal outcomes of post-licensure driver training programmes.

Furthermore, the relationship between driving offences and subsequent crash risk in young novice drivers has been explored [19]. Researchers Clarke et al. [20] found that younger drivers, particularly males, were more likely to be involved in accidents related to speeding, single-vehicle accidents, overtaking on bends, rear-end collisions, and right turns. Researchers also found that young female novice drivers have fewer chances of being involved in a traffic crash than their male counterparts [21]. Young novice drivers may not recognize the risk of certain driving behaviours, such as high speeds and drinking, which may change with longer licensure [22]. The age at which novices obtain their driver’s licence can also impact their crash rates. Older novices tend to have higher traffic violation rates, but delaying licensure can still lead to fewer crashes [23].

Overall, addressing the risky driving behaviours of novice and young drivers is essential to improving road safety. As shown, novice drivers are more likely to engage in risky driving behaviour due to their lack of experience and relatively weak driving skills [24], which points to the need for interventions and training programmes to improve novice drivers’ risk awareness and perception [11].

However, prior studies evaluating educational interventions often show mixed outcomes. Some demonstrate positive effects on attitudes, hazard perception, or self-reported behaviour (e.g., ref. [25], or a meta-analysis shown in [26]), while others find no meaningful reduction in collisions or violations, even though there were improvements in secondary outcomes [27]. Contemporary road traffic safety strategies clearly define the factors that actually lead to accidents, regardless of whether it is the driver, the environment, or the vehicle itself. A differentiation like this can enable finding better solutions that aim to prevent human mistakes and errors by utilizing knowledge of the causes of driving errors and encouraging better ergonomics in accordance with human capabilities and weaknesses [28].

Education and training programmes that aim to increase knowledge of strategies for overcoming potentially dangerous driving situations have been put into place in many environments and have also been studied concerning their impact on traffic safety. Several studies have explored the effectiveness of educational interventions in improving road safety outcomes, as described below. A study by Keeler [29] found evidence that educational programmes positively affect road safety, even exceeding the returns to income. This suggests that education significantly promotes traffic safety [30]. Results of a multi-group analysis of young drivers that participated in an educational programme showing potential outcomes of traffic accidents based on personal stories of actual victims showed that participants different from non-participants especially in the relationship between violations as a category of the driver behaviour questionnaire and the accidents that the participants caused later on, but the same results did not show up for errors as another category of the DBQ. Nonetheless, a potential positive effect of educational measures on young and novice drivers through personal contact and empathy was shown [31].

However, not all studies have directly linked education to reduced traffic accidents or injuries. For example, a systematic review by Richmond et al. [32] found that while educational and skills training bicycling programmes may increase knowledge of cycling safety, they do not seem to translate into a decrease in injury rates or improved bicycle handling ability and attitudes. Similarly, Duperrex et al. [33] systematically reviewed randomized controlled trials on pedestrian safety education. While such education can change observed road-crossing behaviour, it is unclear whether this reduces the risk of pedestrian injury in road traffic crashes. In the context of driver education, a systematic review of systematic reviews by Akbari et al. [27] found that the resources allocated to educational programmes may fail to improve traffic safety, as traffic collisions and related injuries do not decrease significantly among participants. Yamani et al. [34] evaluated the effectiveness of a multi-skill programme for training younger drivers on higher cognitive skills. The study found that the programme effectively improved the participants’ cognitive skills, which suggests that comprehensive training programmes targeting multiple skills can benefit beginner drivers. Another study [35] conducted a meta-analysis of training studies focused on latent hazard anticipation in young drivers, and its findings provide valuable insights into the design considerations for training programmes aimed at improving hazard anticipation skills in young drivers. This suggests that specific training programmes targeting hazard anticipation can effectively improve novice drivers’ safety. On the other hand, Mayhew et al.’s [36] study results suggest that the effectiveness of a course for efficient driving alone may not improve safety performance in terms of fewer collisions and convictions.

Taken together, prior research highlights persistent uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of driver education programmes, especially mandatory ones, and of the mechanisms through which educational programmes exert influence. Because theoretical models suggest that attitudes, perceived behavioural control, and risk perception serve as precursors to behavioural intention, studying short-term attitudinal change remains a meaningful and appropriate approach for evaluating the proximal effects of such programmes, even if behavioural outcomes are not immediately measurable. However, the lack of empirical evidence from compulsory, nationally enforced post-licensure programmes such as the one evaluated here is evident. Notably, limited research has methodically investigated these programmes in real-world contexts, despite their fundamental role in graduated licencing systems and their clear emphasis on risk awareness, self-reflection, and hazard anticipation. This study fills the gap by presenting a domain-specific evaluation of short-term attitudinal changes in Slovenia’s compulsory novice driver training programme. The study provides context-specific insights regarding the direction and extent of attitudinal calibration associated with programme participation, based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour and risk-calibration perspectives, rather than calculating causal or behavioural impacts. As such, it examines whether participation in the Slovenian additional training programme is associated with meaningful changes in attitudes linked to safe driving, such as compliance with traffic rules, distraction, risk perception, self-evaluation of driving skill, and acceptance of further training.

Driver education is varied throughout the world, with different entry requirements and ages, as well as various approaches to graduated licensing. Even in EU members, these requirements and procedures vary greatly. As a case country, Slovenia also implements a graduated licensing scheme that puts into place an educational intervention after holding a driver’s licence for a maximum of two years, which aims to increase additional knowledge and skills for novice drivers of personal vehicles. The Drivers Act (ZVoz-NPB1) [37] defines a Novice Driver as an individual who passed a driving test in the Republic of Slovenia and obtained a driving licence to drive a motor vehicle of category A2, A, or B. Such a driver is required to complete a programme of additional training for Novice Drivers no sooner than six months after the issuing of their driving licence, and it has to be concluded after no more than two years after obtaining the original driver’s licence in order for the driver to achieve a permanent licence. The additional training programme for novice drivers includes safe driving training and a group workshop on road safety and psychosocial relations between road users. It was put into place in August 2010 in an effort to reduce traffic crashes involving, and especially caused by, novice drivers. The programme is carried out in groups of up to twelve participants and consists of two parts, namely (1) a theoretical part lasting one pedagogical hour and (2) a practical part lasting six pedagogical hours. The theoretical component covers vehicle dynamics, risk situations, emergency maneuvers, and the use of safety systems, while the practical component focuses on braking, obstacle avoidance, vehicle control in curves, and hazard response.

The programme at the centre of this study is structured as an intensive programme that integrates theoretical instruction with practical driving exercises and facilitated reflection on hazardous driving behaviours. Considering its well-defined content, homogeneous participant group of novice drivers, and concise timeframe, it offers an appropriate framework for evaluating the short-term impact of driver training on participants’ perceptions of road safety and self-assessed driving proficiency, as well as attitudes towards measures of traffic safety. Accordingly, the primary aim of this research is to assess whether participation in the safe driving programme is associated with statistically significant short-term changes in novice drivers’ safety-related attitudes and perceptions using a within-subjects pre–post survey design.

Based on the reviewed literature and the programme’s explicit focus on self-reflection, risk awareness, and hazard anticipation, we hypothesize that taking part in the safe driving course will lead to quantifiable short-term improvements in participating novice drivers’ attitudes and perceptions in a variety of road safety-related categories. In particular, it is anticipated that post-programme answers will exhibit reduced levels of agreement with statements that represent risky or risk-tolerant attitudes. Since these are categories and topics that are directly addressed during the programme, the largest changes are expected in self-perception-related items and general attitudes towards driver education.

2. Materials and Methods

The study employs a pre/post evaluation that involved novice drivers who attended the additional training programme in the second half of 2024. The main data collection method was a survey, which mainly measured attitudes towards factors of safe driving, which was filled out prior to the programme and immediately after.

2.1. Measures and Data Collection

Data collection took place among participants of the additional programme for safe driving in the second half of 2024 in one of the driving centres in Slovenia, which performs these trainings. Overall, we covered approximately 35 groups of participants and obtained 307 pre- and 302 post-programme questionnaires. Participation was completely voluntary; therefore, the sampling procedure used was a non-probability convenience sample based on voluntary response. To be able to identify pairs of pre- and post-programme questionnaire answers in an anonymous manner, the respondents were asked to make up a unique code, consisting of a colour and an animal (e.g., blue giraffe), and to input their code into both questionnaires, which provided even more anonymity than pre-given codes. Consequently, around 35% of the questionnaires from the pre- or post-programme could not reliably connect with their pair, so they were eliminated from further analysis. In total, 225 pairs, each consisting of a pre- and a post-questionnaire, were fully filled out, uniquely identifiable, and connectable based on their unique code, and this set represented the final dataset for analysis.

The main part of the questionnaire consisted of 34 items covering aspects of safe driving practices from the fields of speed, distractors, highway safety, interactions with other traffic participants, alcohol and other psychoactive substance abuse while driving, seatbelt use, and general attitudes towards the completed programme and other drivers. The full 34-item set showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.81), indicating acceptable internal consistency for evaluative purposes. The questionnaire items were selected a priori on the basis of the literature review and established theoretical frameworks, with the aim of covering domains that prior research consistently identifies as crucial concerns for novice drivers, including risk perception, self-evaluation of driving skill, hazard awareness, distraction, and compliance with traffic rules, and were further clarified based on programme content and policy objectives, rather than being empirically generated through factor analysis. The instrument was created for assessment within a particular application setting and was not meant to serve as a fully validated psychometric scale. Respondents evaluated their level of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale ((1) Strongly Disagree; (2) Disagree; (3) Neither Agree nor Disagree; (4) Agree; (5) Strongly Agree). The main part of the questionnaire consisted of identical questions in the pre-programme and the post-programme questionnaire, while the pre-programme questionnaire also included demographic data. The full set of items and their grouping in terms of topics is shown in the table in Appendix A, along with statistical results. The items in the table correspond to the questionnaire items.

In total, 225 participants fully completed the questionnaire before and after education. A slightly higher percentage of the sample were male (55.6%), and most were up to 21 years of age (63.8%), with an additional 29.5% aged between 22 and 35 years.

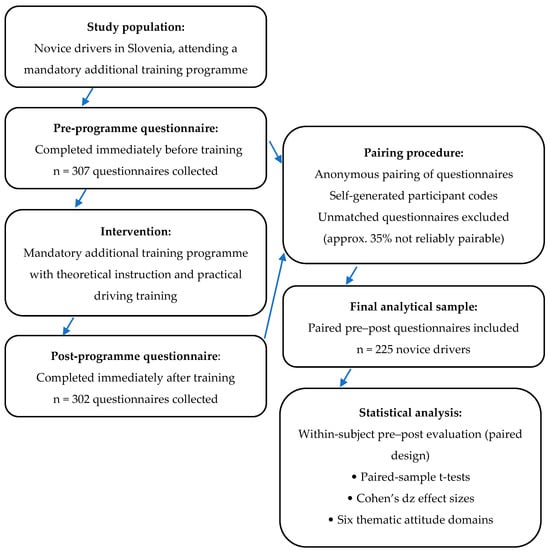

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of the study design, including participant inclusion, pre- and post-programme data collection, anonymous pairing of questionnaires, and the formation of the final analytical sample used for statistical analysis.

Figure 1.

Research flow diagram illustrating participant inclusion, pre- and post-programme data collection, questionnaire pairing procedure, and analytical steps.

2.2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis

Building on established theoretical models, this study evaluates whether participation in the Slovenian additional training programme leads to short-term attitudinal change among novice drivers as assessed by a self-assessment of attitudes towards commonly used predictors of safe driving attitudes. The programme combines theoretical instruction with practical, feedback-rich driving exercises, which are expected to influence drivers’ attitudes toward risk, self-perception, and safe-driving behaviours. Due to the short duration and obligatory nature of the programme, substantial effect sizes were not anticipated; thus, research concentrated on the consistency and direction of change across domains rather than solely on magnitude.

Accordingly, the main hypothesis of the research is that participation in the additional training programme will lead to short-term improvements in novice drivers’ safety-related attitudes, with the largest effects expected in domains that are directly targeted by the intervention. This can be measured by three specific sub-hypotheses:

H1

(Self-perception and overconfidence). Participants will show a significant reduction in self-enhancing or overconfident attitudes following the programme.

H2

(Attitudes toward driver education). Participants will report more positive attitudes toward the relevance and usefulness of post-licencing training.

H3

(Risk evaluation in speeding, intersection behaviour, and distraction). Participants will demonstrate improved attitudes toward high-risk behaviours such as speeding, intersection violations, and in-vehicle distraction.

2.3. Analytical Approach

Data was stored and analyzed using IBM-SPSS Statistics (version 29.0). Missing data diagnosis, univariate, and bivariate analyses were performed. Initial examinations encompassed the utilization of descriptive statistics. Additionally, we employed Little’s test within SPSS to assess the potential systematic connection between the presence of missing values and the observed data, excluding the missing data. This test was used to determine whether the missing data were missing completely at random (MCAR). This procedure was performed using a pairwise option for »Before« (Pre) responses and »After« (Post) responses. The percentage of maximum missingness for variables on the pretest was 0.4%, and the same for the post-test. The Little’s MCAR test for all pretest items (Chi-square = 86,028; DF = 66; Sig. = 0.050) and post-test items (Chi-square = 162,554; DF = 66; Sig. = 0.000) are not missing completely at random (if the value is less than 0.05, the data are not missing completely at random). Missing data were imputed using expectation–maximization (EM) values for further analysis.

After preliminary testing, a paired t-test was conducted to test the set hypothesis and evaluate the potential impact of programme participation on the respondents and the effect of the training programme. We report both statistical significance and estimates of effect sizes for all pre-post comparisons. Cohen’s d was calculated for the paired observations, which is defined as the mean pre-post difference divided by the standard deviation of the difference scores. The dz values of 0.20 were interpreted as small, 0.50 as medium, and 0.8 as large. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was also reported for the mean pre–post change.

To reduce the number of tests and to align the analysis with our conceptual framework, we computed composite scores for six domains of safe-driving attitudes; the items in each domain and the pre/post scores are given in the table in Appendix A. Pre- and post-programme scores were calculated for each domain as the mean of the included items (after reverse-coding where necessary). First, the internal consistency of the 34-item attitude questionnaire items was examined using Cronbach’s alpha for both pre- and post-programme responses. In addition to the overall alpha, internal reliability was also assessed separately for each of the six thematic domains defined in Appendix A. Items that were conceptually framed in the “safe” direction (Q19, Q23, Q27, Q28) were reverse-coded prior to all composite and reliability calculations to ensure consistent interpretation, with higher scores reflecting less safe attitudes. Paired-sample t-tests were performed on each domain composite to assess pre–post changes, accompanied by Cohen’s dz effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals. Third, an overall safety-attitude index was created by averaging all 34 items (after reverse coding where appropriate), providing a general measure of participants’ safety orientation. Pre–post differences were evaluated using paired t-tests with effect sizes, thereby offering a global assessment of attitudinal change across the full item set.

Finally, exploratory subgroup analyses were conducted to examine whether programme effects differed by participant characteristics. Specifically, interaction effects between time (pre vs. post) and gender or age group were analyzed by comparing change scores across subgroups. Although the study design was not powered for detailed subgroup inference, these analyses provided descriptive insights into potential variations in attitudinal change across demographic groups.

3. Results

A total of 225 participants’ pre- and post-questionnaires were successfully paired based on the self-selected unique codes and were consequently included in the analysis. The descriptive statistics were used to determine pre- and post-programme inclusion attitudes towards the given items connected to safe driving; the results are shown in the table in Appendix A. The results show a low average disagreement with unsafe driving elements and low variability, which could indicate that most participants went into the programme with generally positive safety attitudes even before the intervention. Nevertheless, some important statistically significant differences between the pre- and post-programme results were observed, which point to measurable short-term effects of the intervention for novice drivers.

Before analyzing pre–post differences, internal consistency of the 34-item attitude set was evaluated. Cronbach’s alpha values indicated good reliability for the overall item set (α_pre = 0.81; α_post = 0.86). Reliability coefficients for the six thematic domains ranged from low to acceptable, with the highest values observed for domains covering traffic rule compliance (α_pre = 0.75; α_post = 0.80) and distraction-related attitudes (α_pre = 0.63; α_post = 0.62). Lower alphas in the remaining domains reflect their conceptual heterogeneity, as they capture multiple facets of driver perception and behaviour rather than single constructs, which is one of the limitations of the thematic constructs as they are set out in the study.

3.1. Item-Level Changes

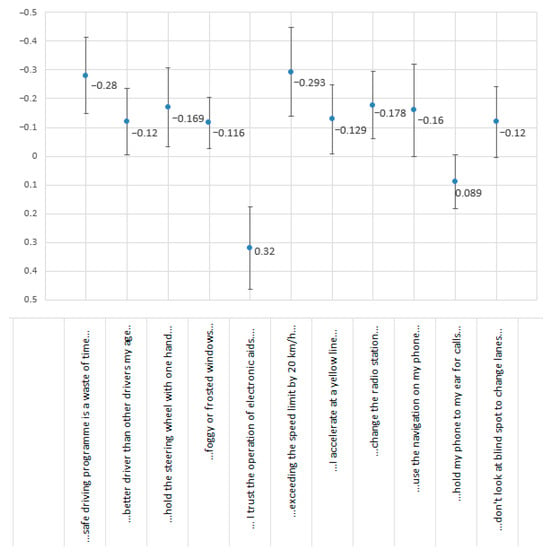

For a more detailed analysis of the differences in responses before and after the programme, a paired-sample t-test was conducted. For the analysis, we assumed the null hypothesis H_0 = μ_PRE-μ_POST and the research hypothesis H_1 = μ_POST < μ_PRE. The paired-samples t-test was conducted for each of the 34 statements to compare the mean ratings of individual items on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree) before and after the programme. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found for ten statements, while two additional statements showed near-significant trends (p < 0.07). Even though these changes were statistically significant, they were small in size with item-level pre–post changes generally small in magnitude (Cohen’s d between −0.29 and 0.28), with no medium or large effects. Only a few items exceeded the conventional threshold for a small effect (|d| ≥ 0.20), and many statistically significant differences were trivial (|d| < 0.20). Most significant changes reflect a decrease in agreement with unsafe or overconfident driving attitudes, and this could suggest a modest yet meaningful improvement in the included novice drivers’ self-perceived safety orientation and attitudes as a result of being included in the programme. It should be noted that some items are reverse-coded, meaning that the expected shift would be towards higher agreement post programme, e.g., “Current well-being can affect my driving,” and these are marked as such in the table in Appendix A. Figure 2 shows item-level mean change (Δ = post−pre) with 95% CI for statements showing significant or near-significant pre–post differences (n = 225). Negative Δ indicates reduced agreement with unsafe attitudes (safer) for items phrased in an unsafe direction; for items phrased in a safe direction (e.g., trust in electronic aids), positive Δ indicates a safer shift.

Figure 2.

Item-level mean pre–post changes (Δ) with 95% confidence intervals for statistically significant and near-significant questionnaire items. For increased clarity, the items are shown in shortened form in the x axis on the graph since the item text is too long.

The direction of all significant changes indicated improved safety orientation, which is shown either through lower agreement with items describing unsafe attitudes or a more realistic self-assessment of their driving ability. The items were set in a way that they describe six thematic categories that reflect the conceptual structure of the questionnaire, and the results across the thematic categories are presented below.

The programme positively influenced participants’ general attitudes toward road safety education. A significant reduction was shown in the attitude towards safe driving programmes being a waste of time (t = 4.17, p < 0.001), with mean values decreasing from 1.90 before the programme to 1.62 after the programme. This suggests that participants recognized the value and relevance of post-licencing education and showed better agreement with the sensibility of attending them. The other item in the group, related to the perceived necessity of training for licenced drivers (Q33), was reverse-coded since it measured the opinion on whether additional training for drivers should only be mandatory when their licence is withdrawn. The opinion on this was not significantly changed from pre- to post-programme measuring.

Participants exhibited a significant decrease in their self-assessment in terms of being a better driver than their peers (t = 2.04, p = 0.042). This points to an increased awareness of the potential for traffic crashes, potentially mitigating overconfidence, which is a recognized risk factor in novice driver crashes. No significant difference appeared in the respondents’ assessment of their confidence regarding hazard management, and responses to items concerning the influence of current well-being on driving and receptiveness to passenger feedback (reversely coded) also remained stable, suggesting that in the short-term, the programme did not substantially change attitudes related to emotional regulation and interpersonal sensitivity.

Significant improvements were shown in several statements that reflect correct vehicle handling and driving skills. Agreement declined regarding the evaluation of safety while steering with one hand (t = 2.43, p = 0.016) and the need for adequately clearing the windscreen in frosty or foggy conditions (t = 2.56, p = 0.011), indicating heightened awareness of appropriate driving posture and visibility. A statistically significant increase in trust towards electronic braking and stability aids was found (t = 4.40, p < 0.001), likely due to the practical component of the programme, during which participants utilized these aids and received education on their potential benefits. The remaining three items in this category, concerning tyre pressure and the use of the handbrake in snowy conditions, presented no significant change, likely due to the statements being exaggerated or clearly indicating the “correct” answer.

The programme produced some noticeable effects regarding rule compliance and risk perception. Participants showed lower agreement with the acceptability of exceeding the speed limit by 20 km/h outside built-up areas (t = 3.76, p < 0.001) and accelerating to drive across the intersection in time when the traffic light turns yellow (t = 2.13, p = 0.035). Both results demonstrate improved attitudes towards traffic laws and a reduction in tolerance for speeding and risk-taking at intersections. Other items concerning signalling, overtaking, seatbelt use, pedestrian crossings, and maintaining safety distance did not significantly change, but it has to be pointed out that attitudes towards these items were fairly low (under a mean of 2) even pre-programme. Additionally, no significant changes were observed in more extreme or infrequent violations (e.g., transporting passengers in the trunk, overtaking at solid lines), which participants overwhelmingly rejected at both measurement points, which was to be expected since these items measured very problematic behaviours.

In the category of distractions, two significant and one marginal effect were identified. Participants reduced agreement with the safety of changing radio stations while driving (t = 2.97, p = 0.003), and also with using navigation on their phone while driving (t = 1.977, p = 0.049), suggesting increased awareness of in-vehicle distraction risks. A near-significant reduction was shown for attitudes towards using a handheld phone for making calls during driving (p = 0.061), while other forms of distraction, i.e., texting or checking social media while driving, did not change significantly. The lack of difference for these items is most likely due to already low baseline values and a generally strong social disapproval of phone use while driving. The modest improvement in attention-related attitudes aligns with prior evidence that short theoretical inputs can influence awareness, though it is hard to predict if these will successfully transfer into driving behaviour.

Items that assessed situational awareness showed a generally stable pattern pre- and post-programme, with most participants already demonstrating safe attitudes before the programme. A marginally non-significant but favourable change appeared in the importance of checking blind spots while driving on the highway (p = 0.057), which implies a slightly improved attitude towards caution in lane-changing behaviour after the course. High agreement with “When there is a traffic jam on the highway, I position my car to leave space for the rescue lane” (reversely coded) was maintained across both measurements, confirming strong compliance with this critical safety measure. Items related to alcohol use, rest breaks, and fatigue displayed consistently already responsible attitudes even pre-programme and therefore showed only minimal change post-programme.

3.2. Overall Attitudinal Index

Overall, the analysis confirmed that the additional training programme for novice drivers in Slovenia led to statistically significant short-term improvements in selected safety-related attitudes; however, the changes were minor in absolute terms. The largest effect was observed in the assessed benefits of driver education, reduced self-overconfidence, increased negative acceptance of speeding and aggressive intersection behaviour, improved understanding of correct vehicle handling, and greater trust in electronic safety systems. Attitudes toward rule compliance, distraction, and situational awareness remained largely positive and stable, reflecting a high pre-existing level of safety awareness among participants. Most notably, items that describe very critical or extremely dangerous behaviour had low agreement rates even pre-programme, showing a general safety-positive attitude among the included novice drivers.

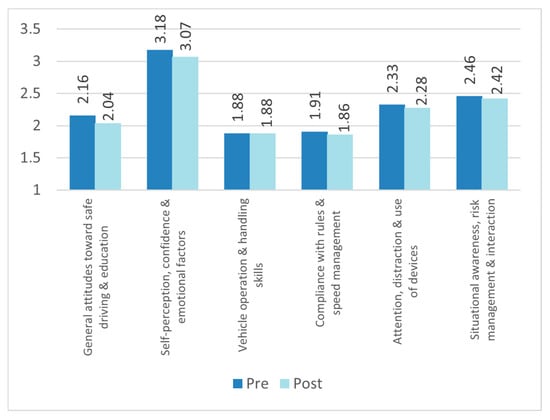

To provide an aggregated overview of these changes, Figure 3 presents mean pre- and post-programme scores across the six thematic categories of safe-driving attitudes (see Appendix A). To ensure interpretive consistency across all items, responses to reverse-coded statements (Q19, Q23, Q27, Q28) were numerically reversed before this analysis.

Figure 3.

Mean pre- and post-programme scores across six thematic categories of safe-driving attitudes, illustrating the direction and relative magnitude of short-term attitudinal change following programme participation (n = 225).

The post-programme means were lower than the pre-training means in all categories except one, indicating a shift toward safer driving attitudes post programme. The largest improvement was observed in general attitudes toward safe driving and education (M_pre = 2.16, M_post = 2.04; Δ = −0.12), which points to the somewhat improved opinion on educational programmes after the intervention. A moderate positive change was also seen in self-perception, confidence, and emotional factors (M_pre = 3.18, M_post = 3.07; Δ = −0.11), which reflects a small potential change in overconfidence while driving. Vehicle operation and handling skills remained stable (M_pre = 1.88, M_post = 1.88; Δ = 0.00), indicating that participants’ self-assessed attitudes towards elements of operational driving did not change, at least on average. Compliance with traffic rules and speed management moderately improved (M_pre = 1.91, M_post = 1.86; Δ = −0.05), with participants showing slightly greater awareness of the importance of rule adherence and appropriate speed selection. Small, but consistent with previous results, improvements were also evident in attention, distraction, and use of devices (M_pre = 2.33, M_post = 2.28; Δ = −0.05), pointing to a reduced acceptance of in-vehicle distractions, and finally, in situational awareness, risk management, and road interaction (M_pre = 2.46, M_post = 2.42; Δ = −0.04), showing a potential for greater sensitivity to situational risk factors and cooperative road behaviour. Even though the changes occurred in the desired directions and domains, the overall absolute changes were very small, since none were over |Δ| = 0.20, pointing to potentially negligible changes, which could also be a consequence of test bias.

To provide an aggregated perspective, an overall safety-attitude index was computed from the mean of all 34 items. A small but statistically significant improvement was observed (M_pre = 2.22, M_post = 2.18; Δ = −0.04; t = 2.44; p = 0.015; dz = −0.16). While modest in absolute size, this finding suggests a general shift toward safer perceptions across the full spectrum of attitudes measured.

3.3. Subgroup Analysis

To explore whether the attitudinal effects of the programme differed across demographic groups, subgroup analyses were conducted for gender and age. Gender was coded as 1 = male and 2 = female (Vpr_PRED_3), while age was reported in four ordered categories (Vpr_PRED_4). Analyses were performed on the overall safety-attitude index (mean of all 34 items, after reverse coding), as this composite provides the most stable and interpretable indicator of general attitudinal change. Subgroup analyses are presented descriptively to explore patterns of change across participant characteristics and were not intended as inferential tests of differential programme effects.

For gender, male participants (n ≈ 98) showed a mean change of −0.02 on the overall index (M_pre = 2.39; M_post = 2.36), whereas female participants (n ≈ 127) showed a slightly larger mean improvement of −0.07 (M_pre = 2.17; M_post = 2.10). An independent-samples t-test comparing change scores between genders indicated that this difference was not statistically significant, t (223) = 1.11, p = 0.266. The effect size was small (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.15), suggesting no meaningful gender-based variation in the programme’s impact.

A within-group paired-sample comparison between pre- and post-answers also indicated significant improvements for both males (t ≈ 2.39, p < 0.02) and females (t ≈ 2.79, p < 0.01), but the magnitude of change was relatively small in both groups (|dz| < 0.20). These findings suggest that both genders benefited from the intervention to a similar extent.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted on the change scores across the four reported age categories. The analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences between age groups, F (3, 220) = 1.88, p = 0.134. Post hoc comparisons likewise showed no meaningful pairwise differences. Mean change scores varied only minimally between groups (range: −0.03 to −0.08), indicating that the programme produced consistent attitudinal effects irrespective of participants’ age.

Together, these analyses indicate that the short-term attitudinal improvements observed in the sample were broadly uniform across demographic subgroups. Overall, neither gender nor age demonstrated statistically significantly different effects of the programme, suggesting that the intervention influenced participants in a relatively consistent manner regardless of age or gender.

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that participation in the Slovenian additional training programme for novice drivers, which all novice drivers have to take part in, in order to obtain their permanent licence, leads to measurable short-term improvements in some safety-related attitudes. Although the participants already demonstrated generally positive attitudes toward safe driving through the pre-programme questionnaire before the intervention, overall, the findings revealed several statistically significant but small post-programme shifts, indicating limited short-term attitudinal calibration rather than substantive change. It has to be pointed out that many pre-programme scores already reflected relatively safe attitudes, which could limit the potential for large observable improvements.

Most consistent improvements were found in the categories associated with self-perception, overconfidence, and general attitudes toward road-safety education, which could be theoretically linked to perceived behavioural control and risk calibration as described by the Theory of Planned Behaviour and driver risk-perception models. The general improvement in attitudes toward driver education suggests that the programme could strengthen the perceived importance of continued learning among novice drivers or improve their self-awareness regarding potential shortcomings in the role of drivers, which is in line with the broader understanding that education can positively influence road safety outcomes. As earlier research has shown, educational measures can have measurable benefits (e.g., refs. [22,23,24] all found that an educational programme has positive outcomes); therefore, the present findings confirm that even a short, structured programme combining theoretical and practical components can have a role in reinforcing positive safety orientations.

An important change in attitudes is also presented with changes in participants’ self-perception and overconfidence, where the reduction in belief that they are better drivers than peers suggests increased realistic self-assessment, which is relevant given the consistent association between overconfidence, inexperience, and novice-driver crash risk [7,8]. This effect may come from the programme’s practical component that exposes participants to risky driving situations and may help them to assess their limitations. Improvements were also observed in attitudes related to speeding and intersection behaviour, which are frequently linked to crashes among young and inexperienced drivers [16,18]. Positive changes in the domain of vehicle operation and handling suggest that experience-based learning reinforces theoretical instruction. Attitudes toward distraction and situational awareness remained relatively stable, likely due to already low baseline acceptance of unsafe practices even before the programme. Regardless, small but consistent improvements were found across thematic categories, in accordance with prior evaluations of educational programmes, which often report modest attitudinal, rather than behavioural, change among road users [25,26,27]. Nevertheless, the modest effect sizes observed across all domains indicate that these shifts, while statistically detectable, may have limited practical significance. In this context, statistical significance reflects consistency of direction across participants rather than meaningful individual-level change. Participants entered the treatment with relatively strong baseline self-reported safety attitudes, allowing only limited opportunity for significant absolute change. The results suggest a moderate yet systematic adjustment in attitudes rather than significant individual change. From a pragmatic standpoint, even small average shifts may be relevant when implemented at the population level and across various safety-related domains concurrently, especially in mandatory national programmes. Attitudinal changes did not extend uniformly across all constructs, which is consistent with previous research. Certain areas, such as situational awareness or attitude towards compliance with regulation, showed little to no change. This potentially points to the conclusion that short-term attitudinal responses represent only one aspect of driver development and do not necessarily predict sustained behavioural change.

Overall, the study findings can offer some support for the rationale of integrating post-licencing education into national traffic safety systems, as encouraged by the European Transport Safety Council [5]. While the observed short-term effects are moderate, they confirm that even brief, standardized interventions can, to an extent, enhance awareness of safe driving principles and promote more responsible attitudes among novice drivers. It has to be taken into account, though, that the pattern of results has illustrated an important distinction between statistical and substantive significance. Although several individual items showed improvements, including reduced acceptance of distraction, greater recognition of speed-related risks, and increased trust in vehicle safety systems, the absolute magnitude of these changes was small (Δ < 0.30 on a five-point scale). This is similar to previous research findings, where short-term attitude shifts are often observed but are likely to be modest and context-dependent, and often do not translate into behaviour on the road. This suggests that while the programme may reinforce certain safety-relevant cognitions, its immediate influence should be interpreted with caution relative to broader developmental factors such as real-world driving experience, peer influence, and gradual increases in hazard-perception skills with age and experience. These elements are well recognized in the literature as dominant contributors to novice-driver crash risk, and they are unlikely to shift substantially during a brief, structured training session.

The present results also highlight the challenge of translating attitudinal improvements into sustained behavioural change. Although attitude theories (e.g., TPB) claim that attitudes contribute to behavioural intention, the relationship between attitudes and on-road behaviour is complex and often dependent on situations, emotional regulation, and real-time decision-making processes, or even on effects such as emotions or vehicle occupancy. Systematic reviews similarly report that even when educational programmes successfully shift attitudes or increase hazard awareness, these changes do not necessarily translate into a reduction in collision rates or risky driving behaviours. Accordingly, the findings of this study should not be interpreted as evidence of enhanced driving safety in itself, but rather as preliminary indications of the potential for cognitive adjustments that may support safer behaviour when combined with continued experience and reinforcement. Additional longitudinal research is needed to determine whether the observed attitudinal changes remain beyond the immediate post-training period or meaningfully influence driving outcomes, such as combining self-reported attitudes with actual driving outcomes or at least on-field testing.

Another important observation comes from the relatively uneven distribution of attitudinal change across the six thematic domains included in the questionnaire. While the items included in the self-perception and confidence categories generally demonstrated the clearest improvement, items related to situational awareness, interaction with other road users, and certain aspects of compliance showed little or no measurable change for pre-post comparisons. This may stem from the different cognitive demands associated with each item, since, for example, risk calibration and self-assessment of driving ability could be more influenced in the short term immediately following structured feedback or supervised practice, as supported by Social Cognitive Theory and prior empirical research. In contrast, situational awareness and higher-order hazard-management skills typically require prolonged experience and repeated exposure to varied traffic environments, which a short training intervention cannot sufficiently provide. We estimate that the category-specific findings are theoretically coherent and suggest that the programme’s strengths lie in areas where attitudinal adjustment is potentially most achievable with a short-term intervention like the one researched here.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, the findings of this study indicate that Slovenia’s additional training programme may contribute to modest short-term improvements in selected safety-related attitudes, particularly those linked to self-perception, acceptance of training, and specific behavioural judgments about speed and distraction. However, the overall pattern of results suggests that the programme’s attitudinal influence is limited and should not be overinterpreted as evidence of an expected broad cognitive or long-term attitudinal change. The largely positive baseline attitudes, in addition to the small effect sizes that were observed, indicate that many participants entered the programme with an already high level of safety-related attitudes, which could have a potential ceiling effect. This ceiling effect, combined with the inherent stability of certain cognitive constructs (such as rule compliance and situational awareness), likely additionally reduced the extent to which further improvements could be achieved inside a single training day.

These findings strongly point to the importance of viewing post-licensure training as only one of the potential components of a wider developmental process and licensure system, rather than a single solution to novice-driver risk changes. Attitudes present just one layer of the psychological factors that shape driving behaviour, and their influence is influenced by experience, feedback, emotional regulation, and real-world decision-making. Consequently, educational programmes should be seen as providing cognitive and attitudinal support, which must be complemented by continued experience and broader systemic measures to produce lasting reductions in crash risk. Further research, including longitudinal and behavioural studies, is required to determine whether the small attitudinal shifts observed here persist over time or translate into measurable safety outcomes, and the potential of these changes, albeit small in scale, when applied to the population of novice drivers in a country as a whole.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered while interpreting the results. The study utilized a within-subject pre–post design without a control group, therefore limiting causal inference. Due to the mandatory requirement of the additional training programme for all novice drivers in Slovenia, the introduction of a comparable control or quasi-experimental group proved unfeasible within the national policy framework. Thus, the observed shifts cannot be solely attributed to the programme, but rather be seen as short-term attitudinal adjustments linked with programme participation.

Secondly, the research depended only on self-reported attitudes, which are susceptible to response biases such as social desirability and demand characteristics. Despite assurance of anonymity via self-generated participant codes, respondents may have nonetheless offered socially desirable responses, especially within a training context centred on road safety. Furthermore, attitudinal measures do not necessarily equate to observed driving behaviour or lasting safety results.

The short duration of the measurement results in a significant limitation. Attitudes were evaluated immediately prior to and following programme participation, therefore indicating only immediate or short-term effects. This design hinders any deductions regarding the lasting impact of attitudinal changes or their possible effects on future driving behaviour, crash involvement, or traffic-related offences

Fourth, while the overall internal consistency of the questionnaire was satisfactory, certain thematic domains demonstrated comparatively low reliability, indicating their conceptual heterogeneity. The domains were determined a priori based on programme content and policy relevance, rather than through empirical scale development, and construct validity was not evaluated using factor-analytic methods. The domain-level findings should be regarded as suggestive rather than conclusive psychological constructs.

The sample was derived from voluntary participation in a mandatory programme, and around one-third of the collected questionnaires could not be accurately matched due to anonymous coding. This approach maintained participant anonymity but may have resulted in selection bias, leading to potential differences between the final analytical sample and the excluded participants in unobserved aspects.

The study was conducted within Slovenia’s distinct institutional, legal, and cultural environment, hence limiting the generalisability of the findings to other countries with differing licensing systems, training frameworks, or traffic cultures. The results should be seen as context-specific data from a nationally implemented post-licensing programme rather than globally applicable impacts.

Future research should refine the measurement instrument, either by aligning it more explicitly with established theoretical constructs or by using empirical validation techniques such as factor analysis.

Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable empirical evidence from a substantial, mandatory, real-world novice driver education programme, a setting where controlled experimental designs are frequently unfeasible. The results provide realistic expectations concerning the extent and range of short-term attitudinal change and can direct the development of future quasi-experimental or longitudinal assessments. A more longitudinal study design incorporating behavioural measures (e.g., telematics, simulator performance, or official offence records) would offer a stronger basis for evaluating the long-term programme effectiveness. A concurrent approach could involve correlating participant data with administrative records of traffic violations or accident involvement and/or conducting longitudinal follow-ups to evaluate the durability of attitudinal and behavioural changes over time, which would provide triangulation between self-reported attitudes and observed behaviours within the identical policy context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.T. and T.C.O.; methodology, D.T.; formal analysis, D.T.; investigation, T.C.O.; data curation, D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C.O.; writing—review and editing, D.T. and T.C.O.; visualization, T.C.O.; supervision, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study falls under the “no risk” category since it involved voluntary and anonymous participation of adult individuals who completed attitude questionnaires before and after attending a mandatory post-licencing training course for novice drivers. Because the study relied entirely on anonymized questionnaire data, no personal identifiers were collected, not even in the form of pre-set codes to connect pre- and post- questionnaires since the participants were free to choose their own codes here. Participants were only asked to indicate age group, gender, and the length of time they had held a driving licence, none of which allows individual identification (e.g., male, 21 years, driving licence for 1 year). The researchers did not have access to any lists of participants’ names or other identifying information. Since they were independent of the actual course, they only came at the beginning and end of the course to invite participants to take part in the survey, give them the questionnaires, and collect them at the end. The Personal Data Protection Act (Official Gazette RS, No. 163/22, https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO7959) (accessed on 15th September 2025) that is the main law in Slovenia governing protection of personal data and also the GDPR state that personal data is relating to an identified or identifiable natural person, which the present study does not operate with, and therefore, it is considered no-risk and therefore exempt from prior ethics committee review. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised 2013) and with the principles of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) concerning anonymized data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, and participation was completely voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full results of statistical analysis on the item level. Items marked with an asterisk (*) are statistically significant.

Table A1.

Full results of statistical analysis on the item level. Items marked with an asterisk (*) are statistically significant.

| Item Level Mean | Std. Error of Item Level Means | Std. Deviation on Item Level | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | df | Two-Sided p | Cohen’s d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||||||

| General attitudes toward safe driving and education | |||||||||||||

| Attending a safe driving programme is a waste of time. | PRE (Q_B_1) | 1.9 | 0.065 | 0.968 | 0.280 | 1.007 | 0.067 | 0.148 | 0.412 | 4.169 | 224 | 0.000 * | 0.278 |

| POST (Q_A_1) | 1.62 | 0.057 | 0.858 | ||||||||||

| Training for drivers who already hold a driving licence should only be mandatory in the event of the withdrawal of a driving licence. | PRE (Q_B_33) | 2.42 | 0.074 | 1.107 | −0.036 | 1.239 | 0.083 | −0.198 | 0.127 | −0.431 | 224 | 0.667 | 0.136 |

| POST (Q_A_33) | 2.45 | 0.074 | 1.114 | ||||||||||

| Self-perception, confidence, and emotional factors | |||||||||||||

| I am a better driver than other drivers my age. | PRE (Q_B_2) | 2.9 | 0.061 | 0.913 | 0.120 | 0.881 | 0.059 | 0.004 | 0.236 | 2.044 | 224 | 0.042 * | 0.069 |

| POST (Q_A_2) | 2.78 | 0.068 | 1.020 | ||||||||||

| I am confident in my ability to handle potential hazards while driving. | PRE (Q_B_3) | 3.6 | 0.059 | 0.892 | 0.071 | 1.024 | 0.068 | −0.063 | 0.206 | 1.042 | 224 | 0.299 | −0.017 |

| POST (Q_A_3) | 3.52 | 0.055 | 0.819 | ||||||||||

| Current well-being can affect my driving. (reverse coded) | PRE (Q_B_19) | 4.06 | 0.242 | 3.63 | 0.009 | 3.576 | 0.238 | −0.461 | 0.479 | 0.037 | 224 | 0.970 | 0.162 |

| POST (Q_A_19) | 4.05 | 0.064 | 0.957 | ||||||||||

| I should consider my passenger when they criticize the way I drive. (reverse coded) | PRE (Q_B_23) | 1.93 | 0.067 | 1 | −0.018 | 0.901 | 0.060 | −0.136 | 0.101 | −0.296 | 224 | 0.768 | 0.027 |

| POST (Q_A_23) | 1.95 | 0.065 | 0.978 | ||||||||||

| Vehicle operation and handling skills | |||||||||||||

| In normal road conditions, it is enough that I hold the steering wheel with one hand. | PRE (Q_B_5) | 2.4 | 0.077 | 1.162 | 0.169 | 1.043 | 0.070 | 0.032 | 0.306 | 2.429 | 224 | 0.016 * | 0.198 |

| POST (Q_A_5) | 2.24 | 0.077 | 1.162 | ||||||||||

| If I have foggy or frosted windows on my car, it is enough to clear enough to see the road. | PRE (Q_B_8) | 1.72 | 0.059 | 0.886 | 0.116 | 0.678 | 0.045 | 0.026 | 0.205 | 2.556 | 224 | 0.011 * | 0.170 |

| POST (Q_A_8) | 1.60 | 0.054 | 0.813 | ||||||||||

| I should inflate my car tyres as much as possible to save on fuel. | PRE (Q_B_9) | 1.67 | 0.054 | 0.817 | 0.040 | 0.960 | 0.064 | −0.086 | 0.166 | 0.625 | 224 | 0.533 | 0.042 |

| POST (Q_A_9) | 1.63 | 0.056 | 0.841 | ||||||||||

| In case of snow, I can use the handbrake to help maneuver in bends. | PRE (Q_B_10) | 1.59 | 0.055 | 0.831 | −0.062 | 0.904 | 0.060 | −0.181 | 0.057 | −1.032 | 224 | 0.303 | −0.069 |

| POST (Q_A_10) | 1.65 | 0.058 | 0.874 | ||||||||||

| I have enough abilities so that I do not need to adjust my speed when driving in severe weather conditions. | PRE (Q_B_15) | 1.43 | 0.041 | 0.609 | 0.009 | 0.713 | 0.048 | −0.085 | 0.103 | 0.187 | 224 | 0.852 | −0.037 |

| POST (Q_A_15) | 1.42 | 0.047 | 0.710 | ||||||||||

| While driving a car, I trust the operation of electronic braking and vehicle stability aids. | PRE (Q_B_34) | 2.45 | 0.07 | 1.052 | −0.320 | 1.092 | 0.073 | −0.463 | −0.177 | −4.397 | 224 | 0.000 * | 0.010 |

| POST (Q_A_34) | 2.77 | 0.074 | 1.113 | ||||||||||

| Compliance with traffic rules and speed management | |||||||||||||

| If there is no one on the road around, I do not need to use the turn signals. | PRE (Q_B_4) | 1.74 | 0.063 | 0.944 | −0.013 | 0.770 | 0.051 | −0.115 | 0.088 | −0.260 | 224 | 0.795 | 0.112 |

| POST (Q_A_4) | 1.75 | 0.064 | 0.959 | ||||||||||

| At distances shorter than 500 m, it makes no sense to fasten with a seat belt. | PRE (Q_B_11) | 1.39 | 0.047 | 0.711 | −0.022 | 0.608 | 0.041 | −0.102 | 0.058 | −0.548 | 224 | 0.584 | 0.012 |

| POST (Q_A_11) | 1.41 | 0.043 | 0.649 | ||||||||||

| I do not need to stop for a pedestrian standing at a pedestrian crossing. | PRE (Q_B_13) | 1.52 | 0.051 | 0.762 | 0.009 | 0.906 | 0.060 | −0.110 | 0.128 | 0.147 | 224 | 0.883 | 0.007 |

| POST (Q_A_13) | 1.51 | 0.055 | 0.819 | ||||||||||

| Driving too safely can also be dangerous. | PRE (Q_B_14) | 3.11 | 0.081 | 1.21 | 0.124 | 1.115 | 0.074 | −0.022 | 0.271 | 1.674 | 224 | 0.096 | 0.251 |

| POST (Q_A_14) | 2.99 | 0.085 | 1.273 | ||||||||||

| In case there are more passengers than there are available seats in the car, I can transport them in the trunk on short distances. | PRE (Q_B_16) | 1.34 | 0.04 | 0.607 | 0.004 | 0.637 | 0.042 | −0.079 | 0.088 | 0.105 | 224 | 0.917 | 0.142 |

| POST (Q_A_16) | 1.34 | 0.041 | 0.621 | ||||||||||

| Exceeding the speed limit by 20 km/h outside a built-up area does not pose a major danger to me. | PRE (Q_B_17) | 2.24 | 0.076 | 1.135 | 0.293 | 1.170 | 0.078 | 0.140 | 0.447 | 3.761 | 224 | 0.000 * | 0.002 |

| POST (Q_A_17) | 1.94 | 0.074 | 1.115 | ||||||||||

| In the event that the yellow light comes on at the traffic light, I accelerate to drive across the intersection in time. | PRE (Q_B_18) | 2.39 | 0.074 | 1.105 | 0.129 | 0.909 | 0.061 | 0.009 | 0.248 | 2.126 | 224 | 0.035 * | −0.107 |

| POST (Q_A_18) | 2.26 | 0.077 | 1.152 | ||||||||||

| On the highway, I can drive in the overtaking lane all the time. | PRE (Q_B_20) | 1.62 | 0.051 | 0.765 | −0.089 | 0.830 | 0.055 | −0.198 | 0.020 | −1.607 | 224 | 0.109 | −0.088 |

| POST (Q_A_20) | 1.71 | 0.051 | 0.764 | ||||||||||

| In the event that a passenger in the car does not fasten their seat belt, I do not need to warn them, as this is not my job. | PRE (Q_B_21) | 1.58 | 0.05 | 0.753 | −0.067 | 0.756 | 0.050 | −0.166 | 0.033 | −1.323 | 224 | 0.187 | −0.126 |

| POST (Q_A_21) | 1.64 | 0.053 | 0.801 | ||||||||||

| A large safety distance at 50 km/h is not important. | PRE (Q_B_29) | 1.64 | 0.053 | 0.797 | 0.107 | 1.016 | 0.068 | −0.027 | 0.240 | 1.574 | 224 | 0.117 | −0.020 |

| POST (Q_A_29) | 1.53 | 0.059 | 0.882 | ||||||||||

| Overtaking a slower car at a solid line on the road is sometimes necessary. | PRE (Q_B_32) | 2.44 | 0.079 | 1.19 | −0.044 | 1.025 | 0.068 | −0.179 | 0.090 | −0.650 | 224 | 0.516 | −0.071 |

| POST (Q_A_32) | 2.48 | 0.085 | 1.279 | ||||||||||

| Attention, distraction, and use of devices | |||||||||||||

| In case of fatigue, I can successfully distract myself with increased volume of the music. | PRE (Q_B_6) | 2.46 | 0.08 | 1.202 | 0.027 | 0.972 | 0.065 | −0.101 | 0.154 | 0.411 | 224 | 0.681 | 0.012 |

| POST (Q_A_6) | 2.43 | 0.077 | 1.156 | ||||||||||

| I can change the radio station while driving if I want to. | PRE (Q_B_7) | 3.67 | 0.075 | 1.121 | 0.178 | 0.899 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.296 | 2.967 | 224 | 0.003 * | 0.132 |

| POST (Q_A_7) | 3.49 | 0.076 | 1.142 | ||||||||||

| I can hold my phone to my ear and make phone calls while driving. | PRE (Q_B_22) | 1.35 | 0.036 | 0.547 | −0.089 | 0.708 | 0.047 | −0.182 | 0.004 | −1.884 | 224 | 0.061 | 0.063 |

| POST (Q_A_22) | 1.44 | 0.047 | 0.699 | ||||||||||

| I can easily look at the received message on my phone and respond while driving. | PRE (Q_B_24) | 1.42 | 0.042 | 0.637 | −0.053 | 0.748 | 0.050 | −0.152 | 0.045 | −1.069 | 224 | 0.286 | 0.057 |

| POST (Q_A_24) | 1.48 | 0.048 | 0.714 | ||||||||||

| When I am standing in a queue in front of a traffic light, I can check social media and reply to messages. | PRE (Q_B_25) | 1.96 | 0.066 | 0.995 | 0.013 | 1.151 | 0.077 | −0.138 | 0.165 | 0.174 | 224 | 0.862 | 0.105 |

| POST (Q_A_25) | 1.95 | 0.080 | 1.196 | ||||||||||

| While driving, I can safely use the navigation on my phone to guide me to my destination. | PRE (Q_B_26) | 3.09 | 0.078 | 1.171 | 0.160 | 1.214 | 0.081 | 0.000 | 0.320 | 1.977 | 224 | 0.049 * | 0.128 |

| POST (Q_A_26) | 2.93 | 0.078 | 1.169 | ||||||||||

| Situational awareness, risk management, and road interaction | |||||||||||||

| Driving after drinking one beer or glass of wine does not seem problematic to me. | PRE (Q_B_12) | 2.21 | 0.086 | 1.294 | 0.138 | 1.344 | 0.090 | −0.039 | 0.314 | 1.537 | 224 | 0.126 | 0.021 |

| POST (Q_A_12) | 2.07 | 0.091 | 1.367 | ||||||||||

| In the event of a car breakdown on the motorway, I should stop in the emergency lane, put up a signal and wait for help in the vehicle. | PRE (Q_B_27) | 3.07 | 0.101 | 1.516 | 0.084 | 1.339 | 0.089 | −0.091 | 0.260 | 0.946 | 224 | 0.345 | 0.021 |

| POST (Q_A_27) | 2.99 | 0.096 | 1.447 | ||||||||||

| When there is a traffic jam on the highway, I should position my car on the far side in any case to leave space for the rescue lane. (reverse coded) | PRE (Q_B_28) | 4.26 | 0.075 | 1.128 | 0.080 | 1.409 | 0.094 | −0.105 | 0.265 | 0.852 | 224 | 0.395 | −0.043 |

| POST (Q_A_28) | 4.18 | 0.077 | 1.155 | ||||||||||

| On the highway, I do not have to look at my blind spot to change lanes, as using the side mirrors is enough. | PRE (Q_B_30) | 1.62 | 0.063 | 0.952 | 0.120 | 0.940 | 0.063 | −0.003 | 0.243 | 1.916 | 224 | 0.057 | −0.029 |

| POST (Q_A_30) | 1.50 | 0.053 | 0.791 | ||||||||||

| While driving, it makes sense to take breaks when I start to fall asleep. | PRE (Q_B_31) | 3.73 | 0.085 | 1.276 | 0.027 | 1.295 | 0.086 | −0.144 | 0.197 | 0.309 | 224 | 0.758 | −0.293 |

| POST (Q_A_31) | 3.70 | 0.081 | 1.208 | ||||||||||

References

- World Health Organization. Road Traffic Injuries. 20 June 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- European Commission. Road Safety in the EU; European Commission Press Release: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_953 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Wijnen, W.; Weijermars, W.; Schoeters, A.; van den Berghe, W.; Bauer, R.; Carnis, L.; Elvik, R.; Martensen, H. An analysis of official road crash cost estimates in European countries. Saf. Sci. 2019, 113, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schützenhöfer, A.; Krainz, D. Auswirkungen von Driver Improvement Maßnahmen auf die Legalbewährung. Z. Verkehrsrecht 1999, 4, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- European Transport Safety Council (ETSC). 5th EU Road Safety Action Programme 2020–2030; European Transport Safety Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: http://etsc.eu/wp-content/uploads/5th_rsap_2020-2030_etsc_position.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- European Transport Safety Council (ETSC). New EU Rules on Driving Licences—The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; European Transport Safety Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://etsc.eu/new-eu-rules-on-driving-licences-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Underwood, G. Visual attention and the transition from novice to advanced driver. Ergonomics 2007, 50, 1235–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifty, G.; Zubair, S.M.; Poobalan, A.; Sumit, K. Effective interventions in road traffic accidents among the young and novice drivers of low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 12, 100865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bao, X.; Wu, H.; Wu, W. A study on correlation of traffic accident tendency with driver characters using in-depth traffic accident data. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 9084245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauer, S.; Guo, F.; Simons-Morton, B.; Ouimet, M.; Lee, S.; Dingus, T. Distracted driving and risk of road crashes among novice and experienced drivers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollatsek, A.; Narayanaan, V.; Pradhan, A.; Fisher, D. Using eye movements to evaluate a PC-based risk awareness and perception training program on a driving simulator. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2006, 48, 447–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Parker, B.; Watson, B.; King, B.; Hyde, M. Mileage, car ownership, experience of punishment avoidance, and the risky driving of young drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2011, 12, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hanyin, S.; Ji, X. Insights into factors affecting traffic accident severity of novice and experienced drivers: A machine learning approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, T.; Horswill, M. Using fuzzy signal detection theory to determine why experienced and trained drivers respond faster than novices in a hazard perception test. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2007, 39, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, H.A. Hazard and risk perception among young novice drivers. J. Saf. Res. 1999, 30, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Social cognitive theory. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol. 1. Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues; Harris, K.R., Graham, S., Urdan, T., McCormick, C.B., Sinatra, G.M., Sweller, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horswill, M.S.; McKenna, F.P. Drivers’ hazard perception ability: Situation awareness on the road. In A Cognitive Approach to Situation Awareness; Banbury, S., Tremblay, S., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2004; pp. 155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, H.; Cullen, P.; Senserrick, T.; Rogers, K.; Boufous, S.; Ivers, R. Driving offences and risk of subsequent crash in novice drivers: The DRIVE cohort study 12-year follow-up. Inj. Prev. 2022, 28, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, D.D.; Ward, P.; Truman, W. Accident Mechanism in Novice Drivers. Behavioural Research in Road Safety IX; PA3524/99; TRID: Wokingham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Garawi, N.; Dalhat, M.; Aga, O. Assessing the road traffic crashes among novice female drivers in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, P.F.; Elliott, M.R.; Shope, J.T.; Raghunathan, T.E.; Little, R.J.A. Changes in young adult offense and crash patterns over time. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2001, 33, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.; Masten, S.; Browning, K. Crash and traffic violation rates before and after licensure for novice California drivers subject to different driver licensing requirements. J. Saf. Res. 2014, 50, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Y.; Lou, Y. Research on risky driving behavior of novice drivers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.L.; Pollatsek, A.P.; Pradhan, A. Can novice drivers be trained to scan for information that will reduce their likelihood of a crash? Inj. Prev. 2006, 12, i25–i29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakharan, P.; Bennett, J.M.; Hurden, A.; Crundall, D. The efficacy of hazard perception training and education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 202, 107554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.B.; Lankarani, K.; Heydari, S.T.; Motevalian, S.A.; Tabrizi, R.J.; Sullman, M. Is driver education contributing towards road safety? A systematic review of systematic reviews. J. Int. Violence Res. 2021, 13, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elslande, P.; Naing, C.; Engel, R. Analyzing Human Factors in Road Accidents: TRACE WP5 Summary Report; Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler, T. Highway safety, economic behavior, and driving environment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 684–693. [Google Scholar]

- Kopits, E.; Cropper, M. Traffic fatalities and economic growth. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2005, 37, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolšek, D.; Babić, D.; Fiolić, M. The effect of road safety education on the relationship between driver’s errors, violations and accidents: Slovenian case study. European Transport Research Review 2019, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, S.; Zhang, Y.; Stover, A.; Howard, A.; Macarthur, C. Prevention of bicycle-related injuries in children and youth: A systematic review of bicycle skills training interventions. Inj. Prev. 2013, 20, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duperrex, O.; Bunn, F.; Roberts, I. Safety education of pedestrians for injury prevention: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br. Med. Assoc. 2002, 324, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamani, Y.; Samuel, S.; Knodler, M.; Fisher, D. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a multi-skill program for training younger drivers on higher cognitive skills. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unverricht, J.; Samuel, S.; Yamani, Y. Latent hazard anticipation in young drivers: Review and meta-analysis of training studies. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2018, 2672, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, D.; Vanlaar, W.; Lonero, L.; Robertson, R.; Marcoux, K.; Wood, K.; Clinton, K.; Simpson, H. Evaluation of beginner driver education in Oregon. Safety 2017, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drivers’ Act. Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia No. 92/22, 2022. Vol. 84, No. 3 (Jun., 1994). Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO7164 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.