Abstract

Compressed air systems are widely used in industry, and air leaks that occur over time lead to significant and unnecessary energy losses. This study aims to quantify the energy-saving potential of compressed air leaks in a manufacturing plant and to develop machine learning (ML) regression models for sustainable leak management. A total of 230 leak points were identified by measuring three periods using an ultrasonic device. Using the measured acoustic emission level (dB) and probe distance (x) as inputs, the leak flow rate, annual energy-saving potential, cost loss, and carbon footprint were calculated. As a result of the repairs, energy consumption improved by 8% compared to the initial state. Three regression models were compared to predict leak flow: Linear Regression, Bagging Regression Trees, and Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines. Among the models evaluated, the Bagging Regression Trees model demonstrated the best prediction performance, achieving an R2 value of 0.846, a mean squared error (MSE) of 389.85 (L/min2), and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 12.13 L/min in the independent test set. Compared to previous regression-based approaches, the proposed ML method contributes to sustainable production strategies by linking leakage prediction to energy performance indicators.

1. Introduction

1.1. Compressed Air Systems (CASs)

The increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere has accelerated global warming, making climate change one of the most critical problems of our time. Therefore, increasing energy efficiency is a fundamental strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and is considered one of the most essential for the sustainability of our planet [1]. Given this reality, developing energy-efficiency-based policies and technological solutions is a priority for reducing environmental, economic, and social risks globally. Therefore, determining the carbon footprint (CFP) of industrial facilities has become a focal point for policymakers and researchers as a measurable indicator of global warming [2]. In this context, carbon taxes and carbon pricing stand out as practical economic tools to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Studies show that implementing carbon taxes can reduce per capita CO2 emissions by 1.3% in the short term and by 4.6% in the long term [3]. It should be noted that a carbon price of approximately €100/t-CO2 is increasingly used in the literature and policy analyses as a scenario-based reference value to represent strict climate policy conditions, rather than an actual tax applied equally across all industrial facilities [4,5,6].

One of the energy-intensive systems in industrial facilities is a compressed air system (CAS) [7]. A CAS is defined as the ‘fourth essential service’ after electricity, natural gas, and water, and constitutes a significant portion of total electricity consumption in many industrial facilities [8,9]. The CAS is widely used in various industrial sectors due to its versatility, cleanliness, and operational safety. It operates pneumatic tools, actuators, controls, and numerous production processes. The efficiency of a CAS ranges from 6% to 10%, depending on the compressor type, which is a relatively low value [10]. CAS offers energy efficiency potential in many areas, such as the use of variable speed motors, high-efficiency motors, elimination of air leaks, replacement of filters and silencers, and optimization of the pneumatic network [11]. Due to the high consumption of CASs, small improvements to the system can yield significant savings in energy recovery and costs [12]. Energy efficiency improvements in the CAS and the resulting costs determine the payback period. Accordingly, payback periods in CASs range from 2 to 5 years [13].

Energy efficiency initiatives in CASs can generally be divided into two main categories: systematic and operational interventions. Systematic interventions are improvements that directly affect the entire system. These include technical interventions such as reducing the operating pressure, implementing variable speed drive systems, increasing the diameter of the pressure lines, utilizing the heat generated at the compressor’s outlet air, upgrading the compressor with a more efficient motor, or adjusting the inlet temperature. Such initiatives have high initial investment costs [14]. On the other hand, operational energy efficiency measures are operational approaches aimed at reducing inefficiencies while the system is running. For example, preventive strategies such as detecting and repairing air leaks immediately or activating parallel pressure lines at different times can be implemented to improve the dynamic performance of the system.

1.2. Positioning the Study Within the Sustainability Literature

Improving the energy efficiency of industrial auxiliary systems is widely accepted as a fundamental pillar of industrial decarbonization and sustainable production. Recent studies in the literature demonstrate that systemic efficiency improvements in steam, compressed air, and other auxiliary subsystems can deliver significant energy savings and emission reductions while supporting long-term plant-level competitiveness and resilience [15]. Similarly, technical-economic evaluations of industrial steam systems show that structured assessment of efficiency options, when combined with decision-driven indicators, enables the industry to align operational improvements with broader sustainability goals and investment constraints [16]. Building on this literature, the present study extends the sustainability discussion to a multi-auxiliary system perspective by quantifying and predicting the performance of interconnected auxiliary subsystems using data-driven models. In this way, the study contributes to sustainable production by linking plant-level operational analytics to measurable progress toward industrial-scale energy efficiency and de-carbonization goals.

1.3. Air Leakages in CAS

Compressed air leakages in the CAS are among the most significant energy-saving opportunities and have a high recovery rate. In poorly maintained CAS, leakage rates can reach up to 30% of total compressed air production [17]. These leakages are significant sources of energy loss, cost inefficiency, and environmental impact, especially considering the energy-intensive nature of compressed air production [18]. However, producing compressed air at high cost, releasing it into the environment for trivial, avoidable reasons, and paying carbon taxes are highly undesirable practices. The problem is further compounded by the fact that leakages are often inaudible, intermittent, and difficult to detect without specialized equipment such as ultrasonic leakage detectors [19]. Leakages in CASs can occur for many reasons, including improper system installation, leakages or poor material quality, and improper use of pipes, valves, and fittings. Leakages observed in the field have most commonly been attributed to lose or damaged fittings, such as pressure regulators, oil filters, and hoses. Furthermore, workers often resort to temporary solutions to address these leakages. These solutions typically fail in the long term and usually exacerbate the problem. Common leakage problems include low-cost filters, regulators, and lubricators, especially when installed incorrectly. Welding defects can also occur in pipe connections and flanges [20]. Identifying leaks in a continuously operating factory environment is challenging because the acoustics emitted by leaks interfere with production noise, making detection nearly impossible. There are numerous methods for detecting and tracking air leakages. For example, Dindorf et al. [21] proposed a technique that uses ultrasonic detectors, differential measurements of the total air flow rate, and infrared thermography to detect air leaks regardless of size. Doyle and Cosgrove [22] developed a non-intrusive method to determine CAS energy consumption and energy loss due to air leakages. The process was tested with case studies conducted at five different industrial facilities. Monitoring the facilities revealed energy losses of approximately 500,000 kWh, and it was determined that 30–60% of these losses could have been prevented. The implementation reduced electricity consumption by up to 60% at one facility. Furthermore, non-energy benefits were observed through increased awareness of system losses. Dudic et al. [23] compared two different non-contact methods for measuring compressed air leakages, ultrasound and infrared thermography, and analyzed the reliability and accuracy of the results. They concluded that thermography yielded reliable results for leakage measurements through holes larger than 1.0 mm, and that ultrasound could detect leaks across all hole sizes. They also proposed diagrams that correlate the acoustic sound level emitted by the leakage with temperature changes. Lee et al. [24] designed and manufactured two non-contact ultrasonic leakage detectors, one with a parabolic reflector and one with a conical horn, for remote pipe leakage detection. They also conducted field tests and achieved signal-to-noise ratios of 4.97 dB and 1.89 dB, respectively, in accordance with ASTM E1002–05 validation standards [25].

1.4. Regression Analysis of CAS

Regression analysis, an artificial intelligence (AI) technique, is a powerful machine learning (ML) method [26]. It is often used to study and optimize complex, multi-objective energy systems [27]. Researchers and engineers can use regression analysis to learn much about energy systems and to make informed optimization decisions. ML methods, including regression analysis, have fundamentally changed the study and analysis of energy systems [28]. Traditionally, energy systems were studied using statistical methods that often failed to capture the complex relationships and patterns within them. However, thanks to advances in ML, scientists can now analyze large amounts of data and discover previously unnoticed correlations and patterns. To understand the interactions among multiple variables, a mathematical model must be fitted to a dataset [29].

Researchers can forecast how energy systems will behave in various scenarios and pinpoint the major factors influencing them by using ML regression analysis. For energy systems to be optimized and operated effectively and sustainably, this information is essential [30]. Another crucial component of energy system analysis that regression analysis can successfully handle is multi-objective optimization. Numerous competing goals, including reducing costs or emissions while increasing reliability, are frequently present in energy systems [31]. Regression analysis’s capacity to handle large datasets is one of its main benefits for analyzing and optimizing energy systems. Energy systems from diverse sources generate large volumes of data. Regression analysis enables effective processing of this data and the extraction of useful information. This enables scientists to understand the system’s behavior better and forecast its future performance [32]. One significant benefit of regression models, also known as data-driven or empirical models, is that they are simpler to build than models based on physical laws and do not require knowledge of the process’s physical underpinnings. Mathematical correlations between input and output variables can be built using data gathered from the system under study; these models typically achieve higher accuracy [33]. All AI techniques, including ML, have recently been applied to identify and characterize compressed-air leaks, particularly in energy-intensive systems. Neves et al. [34] investigated the impact of economic and production factors on reducing energy consumption in industrial environments. They applied regression analysis to the data to identify key energy-saving measures across various technologies. Four logistic models were developed to examine the relationships among costs, production, and energy efficiency across these technologies. The aim was to gain insight into how these factors affect energy efficiency in industries. Doner and Ciddi [35] investigated the energy-saving potential of a CAS designed to reduce electricity consumption in an industrial facility. They first evaluated the feasibility of methods such as repairing line leaks, operating compressors in different modes, and using waste heat recovery systems. Later, they conducted regression analyses to examine the correlations among leakage airflow, noise, and system pressure in a compressor system. The results were shown to contribute to energy-efficiency solutions in industrial facilities. They demonstrated strong correlations between system pressure, air leakage diameter, noise, and annual leakage cost. Schenk et al. [36] developed a device using ML algorithms to automate the detection and prevention of air leakages in an industrial facility. Consequently, they demonstrated the ability to distinguish ambient noise from leakage sounds. Zhang et al. [37] investigated the detection and localization of leaks, a significant cause of energy loss in pneumatic systems. The ability to identify 11 different leakage locations using measurement signals taken from a single point was investigated by using ML methods. The Convolutional Neural Network was used for feature extraction, and the algorithms of Gaussian Process, Support Vector Machine, Regression Tree, Multi-Layer Perceptron, and Random Forest were compared. The results demonstrated that ML methods are effective at detecting and localizing multiple-point leaks.

1.5. Compressed Air Systems, Sustainable Manufacturing, and the SDGs

Compressed air systems (CASs) are among the most energy-intensive utilities in manufacturing plants and typically account for 5–20% of total industrial electricity consumption, depending on sector and plant scale [38]. Modern sustainability frameworks, particularly the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), emphasize that such cross-cutting utility systems must be optimized to support affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), resilient industrial infrastructure and innovation (SDG 9), responsible production (SDG 12), and climate action (SDG 13). Recent studies have shown that systematic efficiency improvements in compressed air generation, storage, and distribution can significantly reduce specific electricity consumption while maintaining required service levels at the point of use [39,40]. Beyond direct energy savings, CAS optimization also reduces indirect greenhouse gas emissions and supports factory-level decarbonization pathways aligned with SDG-oriented energy transitions [41]. In this context, compressed air can no longer be treated as an auxiliary “free” resource; instead, it should be managed as a strategic energy carrier whose performance must be continuously monitored, modeled, and improved using data-driven methods and digital tools [42]. Present study adopts this perspective and positions the optimization of an industrial CAS as a concrete lever for operationalizing the SDGs at the shop-floor scale in a real manufacturing environment.

1.6. Problem Statement and Research Contribution

As stated in the literature, developing a methodology to prevent leaks is crucial because systems operate continuously throughout the year, whether loaded or unloaded. Leaks can prevent the system from reaching the required pressure and cause production stoppages. Therefore, air leaks should be monitored via an energy monitoring system, and the resulting data should be processed using machine learning methods to generate predictions and recommendations for future operations. This study presents field measurements from a manufacturing plant and consists of two parts. The first part evaluates air leakage in the plant’s CAS with respect to energy efficiency and CFP.

In contrast, the second part aims to reveal the correlation between input and output parameters using machine learning methods. A detailed parametric analysis of these inputs and outputs has not yet been reported in the literature. Therefore, by conducting a comprehensive regression analysis, this study aims to fill a gap in the literature. In this context, a detailed examination of air leaks that significantly affect CAS efficiency has been conducted. Three measurements were taken over 6 months using a CSI Instruments LD510 ultrasonic leak detector. These measurements determined the annual flow rate, cost, location, and resulting CO2 emissions associated with air leaks at the CAS. This analysis determined the facility’s energy-saving potential and led to improvements in its CFP.

1.7. Novelty Relative to Existing AI-Based Utility and Leak-Detection Studies

Data-driven and deep learning methods have increasingly been adopted in sustainability for anomaly and leak detection in infrastructure networks, such as water distribution systems and gas pipelines. For example, Lee and Yoo [43] developed an RNN–LSTM-based leak detection model for water distribution networks, demonstrating high detection accuracy and the potential of deep learning to support sustainable water resource management. More recently, Zeng et al. [44] proposed a deep learning framework for precise identification of gas leakage, explicitly framing leak detection as a key enabler of gas pipeline sustainability and safety. While these studies focus primarily on network-scale leak events in single-fluid systems, the present work is novel in three respects: (i) it targets industrial utility subsystems within manufacturing plants (e.g., compressed air, steam, and cooling water) rather than external networks; (ii) it couples AI-based performance modeling with sustainability-oriented indicators such as energy efficiency, specific consumption, and CO2-equivalent emissions; and (iii) it provides an integrated evaluation framework that supports multi-objective decision-making at the plant level, rather than only binary leak/no-leak classification. This combination of scope (plant-level), methodology (hybrid statistical/AI modeling), and sustainability metrics differentiates the proposed approach from the existing literature. It directly addresses the aims and scope of sustainability works.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measurements

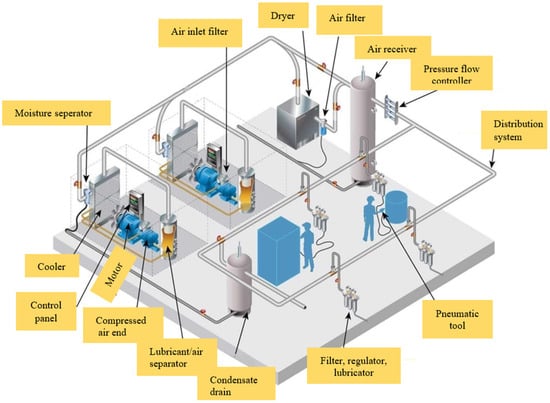

As is well known, there are many areas where energy can be saved in CAS. These include eliminating air leaks, using variable-speed motors and high-efficiency motors, replacing filters and mufflers, and optimizing the pneumatic network [45]. In particular, air leakage significantly affects the efficiency of a CAS. Figure 1 schematically shows the layout of the CAS examined in this study, including the main system components such as the compressor unit, distribution pipelines, and end-use points, as well as the locations where leak measurements were conducted.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of CAS components in the facility.

The air leakage flow rate from the hole in the CAS is measured using an ultrasonic device as follows. Ultrasonic leakage detection devices actually detect the acoustic energy of the compressed air exiting the leakage point, but they do not directly measure the flow rate. These devices calculate the leakage flow rate using empirical models embedded in their software, based on standard compressible-flow equations. The most commonly used basic formula is a derivative of the orifice flow equation for compressible fluids. Some technical data of the leakage detector is listed in Table 1. Therefore, Table 1 provides transparency into how raw measurement data were transformed into model inputs and target variables, thereby linking the experimental measurements to the dataset used for machine learning analyses.

Table 1.

Properties of the leakage detection device.

Figure 2 provides a visual overview of the ultrasonic leak detection device’s use during measurements. The figure illustrates how the ultrasonic device records the acoustic signal emitted by a compressed-air leak at various distances and how experimental data are collected before machine-learning modeling.

Figure 2.

Measurement device, (a) CSI LD 510 brand detector, (b) a photo from measurements.

2.2. Data Reduction

The tonne of oil equivalent (TOE) is a standardized unit of energy commonly used in energy statistics to enable comparison across different energy sources and systems. In this study, electrical energy consumption associated with leaks is expressed in both kWh/year and TOE/year to facilitate comparison with national statistics. The conversion factor of 1 TOE = 11,630 kWh was used. Therefore, expressions such as “20.39 TOE/year” refer solely to energy quantities and do not combine TOE and kWh in the same unit. All subsequent calculations of cost and carbon emissions are based on the kWh values derived from these energy figures.

The most common method for estimating leakage flow in CASs is to apply the isentropic choked-flow equation for compressible fluids, given the geometry of the leakage point, the line’s absolute pressure, and the ambient temperature. In this approach, the leakage point is treated as an orifice, and the flow rate is calculated as follows [46]:

where is the mass flow rate of the compressed air leakage in (kg/s), Cd is the discharge coefficient, A is the area of the orifice (m2), P0 is the air pressure in the system (Pa), T0 is the air temperature in the system (K), R is the specific gas constant (287 J/kgK), and k is the isentropic exponent for air (1.4).

Since Equation (1) contains unknown constants, it is not possible to obtain these data under operational conditions. Therefore, the air flow rate was obtained as [17]

where S is the measured sound in dB. A, B, and C are correlation constants that depend on the operating pressure and the measuring device [15]. Equations (1) and (2) represent two methods used in calculating the ultrasonic flow rate. However, it should be explicitly stated that the dataset used in this study is derived from the ultrasonic device output, and that Equation (2) is used solely for interpretive purposes. The compressor’s label information is given in Table 2. The steps to find the unit cost of the compressed air produced are shown below.

Table 2.

Properties of an air compressor.

Specific power is the energy required by a compressor to compress a given volume of air to a specified pressure. Specific power is a measure of how efficiently a compressor converts the energy it consumes into compressed air. Specific power is calculated by dividing the compressor’s power consumption (kW) by the compressed air production rate (m3/min). The resulting value is expressed as kW/m3/min.

where WC,S, Pmotor, QV, Cm,air, and Celectric represent the motor’s specific power (kWh/m3), the power consumption (kW), the free air delivery (m3/min), the cost of air per unit produced by the compressor (€/m3) and the unit price of electricity (€/kWh), respectively.

To calculate the cost of 1 m3 of air produced by the compressor, the compressor’s specific power was divided by the unit price of electricity. The unit price of electricity was determined by examining company invoices. The amount of energy lost due to air leakages in the CAS is found by

where N denotes the number of compressor stages, V is the air leakage flow rate (m3/s), Pi is the atmospheric pressure (Pa), Ea is the compressor’s adiabatic efficiency, and Em is the compressor motor efficiency [17].

The two biggest challenges in calculating CFP are accurately collecting relevant data and determining emission factors. Both are necessary to calculate the carbon emissions associated with an input or output.

The CFP caused by air leakages is calculated by multiplying the amount of energy lost due to leakages by the carbon emission factor CEF, which is 0.435 kg-CO2/kWh [47]. Here, CFP denotes the annual CO2 emissions resulting from electrical energy losses due to air leakage.

The CO2 emissions associated with the electricity consumption of the compressed air system were estimated using an emission factor of 0.435 kg-CO2/kWh, which is representative of the average grid electricity mix in Türkiye for the reference year 2025 [47]. This factor reflects the combined effect of fossil and renewable generation in the power system. While actual plant-specific emissions may vary depending on the contracted electricity supplier and future changes in the grid mix, the chosen value provides a consistent basis for comparing leakage-related emissions with other studies and scenarios.

To monetize the avoided CO2 emissions, a carbon price of 100 €/t-CO2 was assumed, consistent with recent price levels in the European Union Emissions Trading System and with projections under stringent climate policies. It is acknowledged that the facility investigated here does not necessarily pay this exact price for emissions, particularly if an emissions trading scheme does not directly cover it. The carbon cost values reported in this work should therefore be interpreted as scenario-based indicators that illustrate the potential financial relevance of emissions under high-carbon-price regimes rather than as actual tax savings.

3. Regression Analysis

3.1. ML Dataset Description

The dataset was obtained from an industrial CAS powered by a 110 kW compressor, and the entire system was scanned with an ultrasonic leakage detection device. The ultrasonic sensor used simultaneously recorded the acoustic intensity of the sound leakages in decibels (dB) and the distance between the sensor and the leakage point in cm. A total of 230 observations were collected to ensure sufficient variation in both acoustic and spatial conditions.

The dataset consists of two input and one output variable. Input variables are defined as the acoustic emission sound level in decibels (dB), which reflects the intensity of the leakage and the measurement distance (x) in cm. The output variable is the leakage flow rate (V) in L/min.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Various preprocessing steps were implemented to ensure numerical consistency and reliability in the dataset. First, the numeric format was standardized. Because varying decimal separators in the data (for example, use of decimal commas in some values) could lead to errors in the modeling process, all decimal commas were replaced with periods. Furthermore, unit expressions, symbols, and unnecessary spaces in variable names or cell contents were removed, ensuring that each column contained only pure numerical values. This step is essential for accurate model training.

In the second stage, missing data were imputed. It was determined that some values were missing due to errors in sensor measurements or recording. This problem was addressed using a forward-backward filling method, in which missing values were estimated from neighboring observations. However, if specific rows or columns were consistently missing, these values were removed from the dataset. This minimized data loss and prevented the model from being misled.

In the third step, the dataset was split into training and test sets. The cleaned dataset was randomly divided into 75% for training and 25% for testing. This separation allowed the model not only to fit the training data but also to evaluate its performance on unseen data. A fixed seed value (random seed = 42) was used to ensure reproducibility.

When these preprocessing strategies are combined, the risk of overfitting to the training data is reduced, and a solid basis for objective, bias-free performance evaluation on independent test data is established.

The dataset used to develop and evaluate the proposed models comprises 230 leak observations collected during routine ultrasonic inspections of the compressed air system over several months of regular operation. Inspections were conducted across different production shifts to capture typical variations in load and background noise. For each leak, the sound pressure level (dB) and the distance between the ultrasonic probe and the suspected leak point were recorded. In addition, contextual information, such as the location within the plant, pipe diameter, approximate operating pressure, and accessibility of the leak point, was recorded by the inspection team. Before each measurement, the ultrasonic detector was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s guidelines to minimize systematic measurement errors. When the acoustic signal was unstable or affected by surrounding equipment, repeated readings were taken, and outliers were discarded. The leak volume rate associated with each observation was obtained from the instrument as an estimated flow value, which serves as the reference target for the supervised learning models.

3.3. ML Regression Models

The supervised learning models were implemented using a standard machine learning workflow. The available data were randomly split into a training set comprising 75% of the observations and a test set containing the remaining 25%, with a fixed random seed to ensure reproducibility. Several regression algorithms were initially considered, including decision trees, ensemble methods, and linear baselines. Based on preliminary experiments, a bagging regression with decision tree base learners was selected as the primary model because it offered a favorable trade-off among predictive accuracy, robustness, and interpretability. Bagging outperformed linear regression, GAM, and MARS in preliminary baseline comparisons, consistently achieving higher accuracy and lower prediction errors under identical training and testing conditions. For the bagging model, the number of base estimators was set to 600, and the minimum number of samples per leaf was fixed at 5. Tree depth was left unconstrained to allow the ensemble to capture nonlinear interactions between sound pressure level and distance. Model performance was evaluated on an independent test set obtained using a 75%/25% train–test split with a fixed random seed to ensure reproducibility. Model quality was quantified using common regression metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R2 and adjusted R2), mean square error, and root mean square error, computed on the independent test set.

3.3.1. Linear Regression Model

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was used as the baseline method in this study. The model established for each output variable is mathematically expressed as follows:

where the parameters , , and represent the coefficients estimated by the model, and represents the residual error term. This model structure enables direct interpretation of the marginal effects of independent variables on output. For example, the coefficient indicates the magnitude of change in the relevant output variable caused by a one-unit increase in decibel value. Similarly, the coefficient quantifies the effect of distance on output.

This feature gives OLS regression a significant advantage in model transparency and interpretability. However, because it relies on linear assumptions, it may be limited in capturing complex, nonlinear relationships among variables. Therefore, the OLS model is used solely as a benchmark for comparison and as a basis for evaluating the performance of more flexible, nonlinear methods (e.g., Bagging and MARS).

3.3.2. Bagging Regression Trees Model

In this study, the Bootstrap Aggregating (Bagging) method was applied to regression trees to capture nonlinear relationships and interactions among variables. Bagging is a powerful ensemble method designed to mitigate the high-variance problem inherent in single decision trees. Its basic principle is to generate multiple bootstrap samples from the training data, train independent tree models on each sample, and combine the resulting predictions. The implemented algorithm consists of the following steps:

- ✓

- B = 600 bootstrap samples were randomly selected from the training set.

- ✓

- An independent regression tree () was trained on each bootstrap sample with a minimum leaf size of 5.

- ✓

- Estimates from all trees were combined by taking the arithmetic mean using the following formula:

This ensemble approach reduces the risk of overfitting, increases the stability of estimates, and provides variable importance based on tree-splitting criteria. The Bagging method’s robust modeling of the nonlinear behavior and interactions expected in acoustic leakage dynamics is the primary reason for choosing it for this problem. The method’s flexibility enables more accurate capture of the effects of both decibel level and distance on leakage flow across different combinations.

3.3.3. Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS) Model

The MARS (Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines) method is a powerful approach that combines the interpretability of regression models with the flexibility of nonlinear modeling. This method uses piecewise linear basis functions (hinge functions) in addition to a linear structure to describe the dependent variable. Mathematically, the model is expressed as follows:

where is the constant term, the coefficients represent the weights estimated by the model, and represents the piecewise basis functions. Each basis function is defined in one of the following forms:

where represents the independent variable and represents the knot point.

The MARS algorithm works in two stages:

Forward selection: In this phase, all possible basis functions are added to the model, including variables and different nodes. The result is a complex and extensive model that exhibits overfitting.

Backward pruning: In the second stage, the added basis functions are sequentially removed to reduce model complexity and prevent overfitting. This process results in a more parsimonious model by balancing model flexibility and generalization capability.

MARS demonstrates particularly high success in detecting threshold-based behaviors. For example, it can readily reveal phenomena such as rapid energy loss above a certain decibel level or reduced detectability of leakage at a certain distance threshold. Therefore, MARS is a highly suitable modeling technique for identifying nonlinear relationships between decibel and distance variables in acoustic leakage analyses.

3.4. Model Evaluation Metrics

The predictive performance of all models was evaluated using four complementary metrics on the test dataset.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): MAE represents the average of the absolute differences between the predicted and actual values. This metric measures the overall accuracy of the model, regardless of error direction, and is often preferred for its interpretability.

Mean Squared Error (MSE): The MSE calculates the mean value by squaring the prediction errors. Because squaring penalizes large errors, this metric is particularly strong at reflecting the impact of outliers.

Coefficient of Determination (R2): R2 indicates the extent to which the model explains the total variance of the dependent variable. Its value ranges from 0 to 1, and the closer it is to 1, the greater the explanatory power of the model. A high R2 value indicates that the model can explain the observations with high accuracy.

Adjusted Coefficient of Determination (Adjusted R2): Here, n represents the number of test observations, and represents the number of inputs (independent variables). Adjusted R2 is used to prevent R2 from becoming inflated, particularly in multiple regression problems. R2 often increases artificially when the number of variables increases; however, Adjusted R2 provides a more reliable measure of performance by balancing whether each variable added to the model actually contributes.

When these four metrics are evaluated together, both the error levels (MAE and MSE) and the explanatory power (R2 and Adjusted R2) of the models can be comprehensively assessed, enabling a fair and robust comparison of different modeling approaches.

3.5. Model Interpretability and Visualization

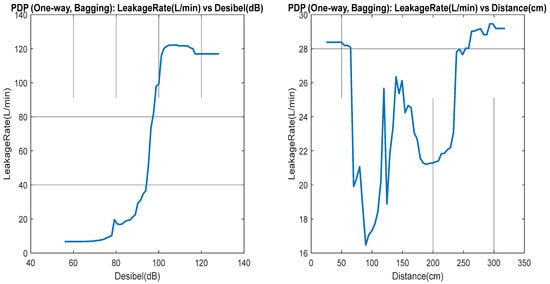

Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) were used, especially for the Bagging model, to increase model transparency and provide a better understanding of the predictive mechanisms.

In one-way PDP analyses, one input variable (e.g., decibel or distance) was held constant, and the effect of the other variable on the output was visualized. This allowed the marginal impact of each variable to be examined independently, and it was observed that certain thresholds (e.g., a sudden increase in leakage after high decibel values) emerged in the model’s predictions.

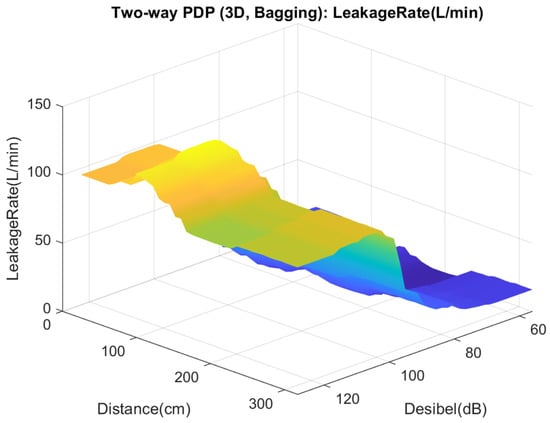

In the two-way PDP phase, the decibel and distance variables were considered jointly, and the effects on the output variable across the two-dimensional input space were illustrated using three-dimensional surface plots. This visualization clearly illustrates the nonlinear relationships arising from the interaction of the two variables and the critical threshold regions. It was determined that leakage reached maximum levels, particularly at low-distance, high-decibel combinations, while at intermediate levels the variables interactively influenced the output.

In addition, scatter plots of predicted and actual values and time series comparison plots (index vs. value plots) were prepared for each model-output pair. Scatter plots demonstrate the model’s predictive power by showing how predictions are distributed around the regression line, while time-series plots compare predicted and observed values over time. This allows for detailed identification of systematic model biases, over- and under-prediction tendencies, and deviations due to outliers.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Measurements

As part of periodic compressed air leakage measurements at the production facility, all compressed air lines were inspected, from the compressor room to the final consumption points. If the CAS is not continuously monitored, leakage can reach up to 30%. As a result of this study, using an ultrasonic device, a dataset was created by identifying leaks at 230 points in the CAS at 7 bar using a 110 kW compressor, the specifications of which are detailed above. Decibel (dB), measurement distance (x), leakage rate (L/min), energy consumption (TOE), annual cost (€), and annual carbon dioxide emissions (t-CO2) were obtained from the ultrasonic leakage detection device.

Policy Context: Climate Neutrality, CBAM, and Industrial Decarbonization

European climate policy increasingly links industrial energy performance to trade and competitiveness through mechanisms such as the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Recent quantitative assessments in the literature demonstrate that CBAM will alter cost structures and trade patterns in carbon-intensive sectors, and that regions and industries with higher embodied emissions face greater vulnerability to border carbon charges [48]. Although CBAM initially targets selected basic materials, the underlying logic—pricing embedded emissions across global value chains—creates a strong incentive for manufacturing firms to reduce the carbon intensity of all energy-using systems, including compressed-air systems. CAS-related electricity consumption and associated emissions, therefore, become relevant not only for internal cost reduction but also for maintaining export competitiveness and mitigating exposure to future carbon constraints. At the same time, policy-oriented sustainability studies emphasize that credible decarbonization trajectories require plant-level measures that can be transparently monitored, verified, and reported to external stakeholders [41,48]. In this policy context, the present work positions its CAS optimization efforts as a concrete, measurable contribution to industrial decarbonization, capable of supporting firms’ compliance with emerging climate regulations and alignment with long-term climate-neutrality targets.

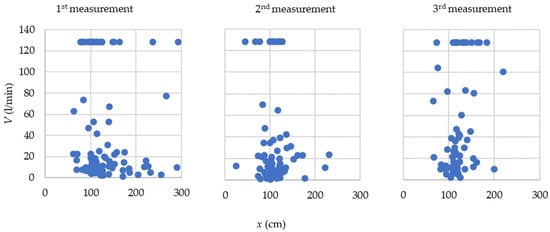

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the distance to the leakage and the leakage rate measured by the ultrasonic device for three measurements. It can be seen that, across all measurements, the leakage airflow rate from the CAS holes is concentrated in the ranges of 10–50 L/min and 120–140 L/min. This non-uniform distribution suggests that while the majority of detected leaks correspond to relatively small leakage rates, a limited number of high-flow leakage points exist. These higher-flow leaks account for a disproportionately large share of the total leakage volume and therefore dominate the associated energy, cost, and environmental impacts. From a practical perspective, this distribution highlights the importance of prioritizing the identification and mitigation of a small number of severe leaks to achieve significant energy and sustainability gains. Additionally, this study determined that the initial total compressed air leakage rate was 20% of the installed compressor capacity before any repair work was undertaken. This value is close to the upper range reported in the literature for industrial compressed air systems, indicating a serious leakage situation and thus justifying the selected case study’s suitability and representativeness.

Figure 3.

Relationship between distance (x) and leakage rate (V).

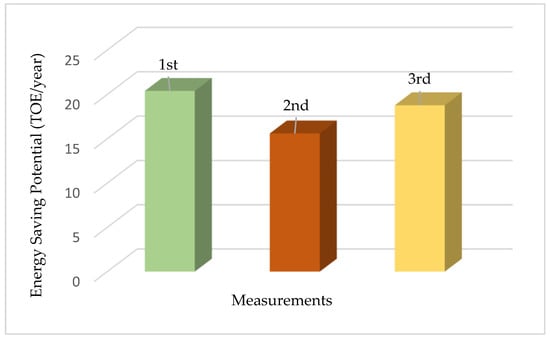

Figure 4 shows the annual energy savings potential from preventing air leaks detected in CAS measurements and the change in this potential between measurements. The initial specific energy loss of the system, ESL,CAS was 20.39 TOE/year before any corrective actions. After repairing the identified leakage points, this value decreased to 15.6 TOE/year, indicating a substantial improvement in the system’s energy performance. A subsequent measurement found ESL,CAS to be 18.77 TOE/year, primarily due to new leaks, likely caused by poor-quality sealing materials and ongoing operational wear. However, compared with the initial state, the system shows an overall improvement of approximately 8%. The detected compressed air leaks were reported and sent to the facility’s maintenance unit for repair. The 8% improvement rate represents the total improvement from the first to the last measurement within one year. The payback period for this study was calculated by dividing the energy efficiency consulting and maintenance costs by the monetary value of the energy savings potential. The calculated payback period is only 0.3 years.

Figure 4.

Calculated energy saving potential (TOE/year).

A parametric sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the estimated economic and environmental benefits with respect to key external parameters. The electricity price and grid emission factor were varied by ±20% around their base values (0.0759 €/kWh and 0.435 kg CO2/kWh). The results indicate that a ±20% change in the emission factor leads to a variation of approximately ±1.8 t-CO2/year in the estimated carbon savings, while a ±20% change in the electricity price results in a variation of approximately ±€714/year in the annual cost savings. These results demonstrate that, although absolute values depend on external assumptions, the relative sustainability benefits of leakage reduction remain robust.

The financial loss caused by these loss has decreased from €18,206 to €14,635, leaving €3571 in the company’s coffers. Under the Border Carbon Adjustment, the CFP tax is expected to be around €100 per t-CO2 [6]. By preventing these leakages, the corporate CFP will be reduced, and approximately €11,500 in carbon tax revenue will remain in the company’s coffers. The carbon cost values reported in this study are not the actual costs currently incurred by the facility under investigation. €100 per t-CO2 was used as a scenario-based assessment to demonstrate the potential financial impacts of compressed air leaks under emerging policy frameworks such as CBAM. This approach aims to support the magnitude of potential future exposure to carbon-related costs and the forward-looking sustainability perspective.

4.2. Results of ML Regression Analysis

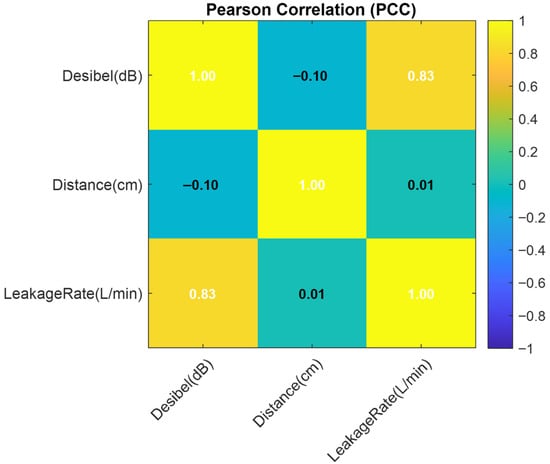

Figure 5 illustrates the statistical relationship between the input variables (decibels, distance) and the output variable (leakage rate) using the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC). Correlation analysis quantitatively demonstrates the linear relationship between the inputs and outputs. A high positive correlation coefficient in the figure indicates a tendency for the leakage amount to increase as acoustic noise (dB) increases. In contrast, a negative correlation coefficient indicates that leakage detection sensitivity decreases with increasing distance. These results demonstrate that the acoustic measuring device is more sensitive at close range and that the noise level is directly related to the leakage flow rate.

Figure 5.

PCC Correlation for decibel, distance, and leakage rate.

Figure 6 shows the marginal effect of each input on the output using the Bagging model in isolation. When decibels alone are considered, the leakage rate increases rapidly above a threshold (e.g., 80 dB). For the distance variable, the model is highly sensitive at short distances, but its predictive power decreases with increasing distance. One-way PDPs clarify the contribution of individual variables to the dependent variable. Figure 6 also shows the marginal effect of each input variable on the predicted leakage flow rate using the Bagging regression model, evaluated independently through one-way partial dependence plots. When varying the sound pressure level while keeping the measurement distance constant, the model response reveals a clear nonlinear pattern, with the leakage rate increasing sharply beyond a certain acoustic threshold (approximately 80 dB). This behavior suggests that high-intensity ultrasonic emissions are strongly associated with severe leaks and confirms the dominant role of the acoustic level in leakage prediction.

Figure 6.

One-way partial analysis between inputs and outputs.

Figure 7 presents a three-dimensional surface plot of the interactive effects of decibels and distance on leakage. The analysis shows that leakage reaches its maximum at the combination of low distance and high decibels. Furthermore, the distance factor is clearly dominant at medium decibel levels, while its effect becomes relatively weaker at higher decibel levels. This confirms the presence of nonlinear threshold behavior in the system.

Figure 7.

Two-way partial analysis between inputs and outputs.

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, median, and maximum) for all variables used in the analysis. The average acoustic emission level is 88.42 dB, indicating that the detected leaks are generally associated with high-intensity ultrasonic signals in an industrial environment. The maximum value of 128.2 dB corresponds to severe leakage and indicates substantial potential for energy loss. For the measurement distance, the average is 124.27 cm, with a maximum of 318 cm, demonstrating that the ultrasonic sensor effectively captures leakage signals over both short and long distances under real operating conditions. Regarding leakage flow rate, values range from 0.613 to 128.19 L/min, with an average of 53.90 L/min. The relatively high standard deviation (48.43 L/min) and the notable difference between the mean (53.90 L/min) and median (18.95 L/min) values indicate a right-skewed distribution, in which a small number of significant leaks dominate the overall leakage volume. This highlights the critical importance of prioritizing high-flow leakage points to achieve substantial energy, economic, and environmental benefits.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the analyzed variables.

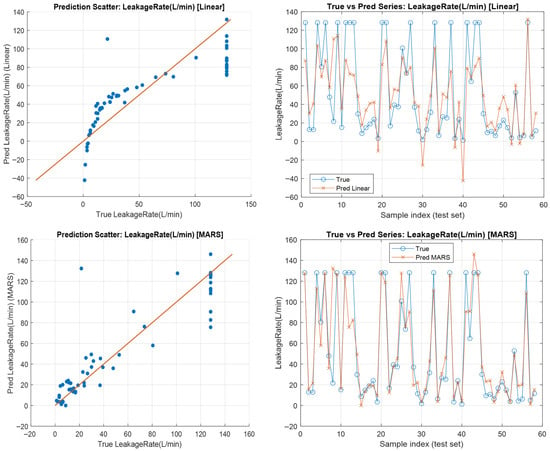

The results presented in Table 4 enable a detailed comparison of the performance of three regression models. First, the Bagging method achieved the highest accuracy with R2 (0.846), demonstrating its explanatory power on the test set. Furthermore, the low MSE (389.85) and MAE (12.134) values indicate that the model is stable not only in terms of overall accuracy but also in its error distribution. This confirms that the Bagging approach effectively captures nonlinear relationships among input variables and reduces the risk of overfitting, thanks to bootstrap sampling and tree-ensemble logic.

Table 4.

Model prediction performance for leakage rate (L/min).

The MARS model comes in second with R2 = 0.823 and is particularly successful in modeling nonlinear transitions between threshold values and variables. While this model’s error rates are slightly higher than those of Bagging, its flexibility in capturing sudden changes in the dependent variable within specific ranges is of practical importance in engineering applications. In contrast, the classical linear regression model exhibited the lowest performance, with R2 = 0.681, and the high MSE (807.72) and MAE (22.604) values indicated that linear assumptions were insufficient to explain the data structure. In particular, ignoring the complex interactions between input variables and outputs limited the model’s predictive capabilities. Therefore, the results strongly suggest that, while linear models provide a benchmark, ensemble-based methods (especially Bagging regression trees) offer a more reliable and effective solution for multidimensional and nonlinear processes such as acoustic leakage prediction.

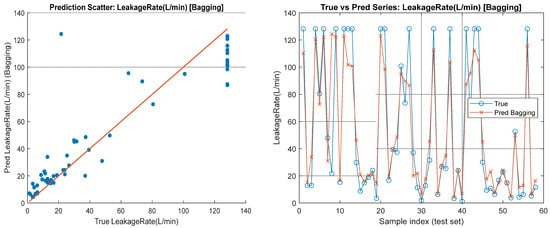

Figure 8 presents the comparison of predicted values to actual values from two different perspectives: first, a scatter plot of predicted and actual values, and second, a comparison of curves over the time series. The scatter plot shows that the Bagging model’s predicted points are densely clustered around the regression line. This demonstrates the model’s high accuracy and strong generalization ability. For low and moderate leakage values, the Bagging model reproduced the actual measurements with high accuracy. In contrast, the Linear Regression model’s point distribution deviates more from the regression line, exhibits systematic biases, and generates significant errors, especially at outliers. While the MARS model does not perform as well as Bagging, it significantly reduces these systematic deviations observed in the linear model and provides a more balanced fit.

Figure 8.

Leakage rate value prediction scatter and true-pred series graphs.

Examining the time-series plot, it is observed that the prediction curves of the Bagging and MARS models broadly capture the actual measurements in the test data, tracking their fluctuations. However, it is observed that, particularly at high leakage flow rates, the predicted curves can fall below or above the actual values, resulting in partial deviations. This suggests that the models struggle to learn extreme values that are rarely represented in the dataset. That additional feature engineering or more complex modeling strategies are needed to capture the dynamics of significant leaks fully. The fluctuations observed in the actual-predicted time series are related to the nature of field measurements conducted in a production facility environment. Leak measurements were taken at different points in the CAS, with varying leak sizes, local flow conditions, and background noise levels. These variations cause uneven changes in the measured leak flow rates, which appear as distortions in the time-series graphs. Therefore, these fluctuations reflect real production conditions.

As a result, the variable importance analysis from the Bagging Regression Trees model indicates that sound pressure level (dB) is the most influential feature for predicting leakage flow rate. In contrast, probe distance makes a comparatively smaller yet non-negligible contribution. This result is consistent with the physical mechanism of ultrasonic leak detection, in which acoustic intensity is primarily governed by leakage severity, whereas distance mainly affects signal attenuation. The dominance of the dB feature also supports the robustness of the model predictions under varying measurement conditions.

4.3. Uncertainty and Sensitivity Considerations

In addition to point estimates of model performance, the variability and uncertainty of the predictions were examined. The distribution of residuals on the independent test set was analyzed to identify potential systematic biases and to verify that prediction errors remained within acceptable limits across the full range of observed leakage values. To indicate the robustness of the results, the sensitivity of the error metrics to the specific test data composition was qualitatively assessed based on the observed residual behavior. While these analyses indicate that the model predictions are reasonably stable, several sources of uncertainty remain outside the strict scope of the machine learning framework. These include the intrinsic uncertainty of the ultrasonic instrument, potential variations in operating pressure during measurements, and the effects of background noise and human factors on probe positioning. Moreover, translating predicted leakage volumes into annual energy consumption, monetary savings, and avoided emissions introduces additional uncertainty stemming from assumptions about operating hours, electricity tariffs, and emission factors. These aspects should be considered when interpreting the numerical results and using them to support decision-making.

4.4. Organizational and Behavioral Dimensions of Industrial Energy Efficiency

Although technological interventions such as high-efficiency compressors, advanced storage designs, and leak-reduction programs are necessary, the literature consistently shows that organizational and behavioral factors largely determine the realized energy savings in industry [49]. Case studies from energy-intensive sectors reveal that barriers such as limited management attention, insufficient time and internal expertise, fragmented responsibilities, and weak feedback on energy performance often prevent cost-effective energy-efficiency measures from being implemented or sustained [49]. Recent sustainability research has also highlighted that energy-related behaviors—such as how operators use equipment, respond to alarms, or follow maintenance instructions—interact strongly with technological solutions. That nudging, feedback schemes, and training can foster more energy-conscious routines [50]. In the context of compressed air systems, this implies that improvements in pressure set points, compressor operation scheduling, and systematic leak management must be embedded within a broader energy management culture, ideally supported by ISO 50001-type practices, key performance indicators, and continuous improvement cycles [40]. By explicitly integrating organizational routines and operator practices into the technical optimization of the CAS, this study responds to calls in the sustainability literature to bridge the persistent gap between technically feasible and actually realized industrial energy efficiency.

4.5. Research Gap and Contribution of This Study

The sustainability literature offers essential insights into CAS modeling, storage design, and factory-level energy management; however, several gaps remain. First, existing CAS studies often focus on component-level modeling (e.g., compressors or storage tanks) or on generic simulation frameworks for sustainable manufacturing, without integrating high-resolution operational data from a real industrial plant with a comprehensive assessment of energy, environmental, and economic impacts [38,39]. Second, many energy-efficiency contributions in manufacturing analyze production systems, such as flow shops or assembly lines, but treat utilities, such as compressed air, as background parameters rather than primary decision variables [40]. Third, there is limited empirical evidence on how CAS optimization can be directly mapped to SDG-related indicators and to emerging climate policy instruments, such as CBAM [41,48]. Addressing these gaps, the present study develops and applies a data-driven methodology that (i) characterizes the baseline performance of an industrial CAS at the system level, (ii) designs and evaluates improvement scenarios using measured plant data, and (iii) quantifies the resulting benefits in terms of energy savings, avoided CO2 emissions, and economic payback. By doing so, this work contributes a practice-oriented case study that links shop-floor optimization of compressed air systems with the broader sustainability agenda discussed in the literature.

4.6. Conceptual Linkage to Sustainability Theory and the Triple Bottom Line

Conceptually, the study is grounded in the triple bottom line (TBL) perspective, which frames sustainability as the joint pursuit of economic, environmental, and social performance [51]. By providing a data-driven framework to monitor and optimize industrial utility systems, the proposed approach contributes to all three TBL dimensions: it reduces energy consumption and emissions (environmental pillar), lowers operating costs and improves productivity (economic pillar), and enhances the reliability of energy services that support worker safety and product quality (social pillar). From a sustainable manufacturing standpoint, integrating such analytical tools into utility management aligns with calls to embed sustainability considerations into design and operational decisions across the full life cycle of manufacturing systems [52]. Accordingly, the models and indicators developed in this work can be interpreted not only as technical instruments but also as practical enablers of sustainability-oriented decision-making in industrial plants, supporting Sustainability’s emphasis on translating sustainability theory into operational practice.

5. Discussion

Because the operating line pressure in the facility is maintained at a constant 7 bar, the relationship between pressure variation and leaks is not explicitly included as an input variable in the machine learning models. Under these operating conditions, the effect of pressure on leak flow is implicitly captured in the measured acoustic emission levels. While this assumption is suitable for the facility under study, it is recommended that line pressure be included in future studies to increase the model’s applicability to systems operating under different or more dynamic pressure regimes.

The quantitative outcomes of this study establish a direct link between shop-floor optimization actions and the broader sustainability agenda defined by the SDGs. The demonstrated reduction in compressed air energy losses, corresponding to an approximately 8% improvement in system performance and measurable annual electricity savings, directly contributes to SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) by enhancing industrial energy efficiency. The reduction in greenhouse gas emissions supports SDG 13 (Climate Action) by avoiding CO2-equivalent emissions from lower electricity demand. In addition, the economic savings achieved through targeted leakage mitigation align with SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) by promoting more resource-efficient and resilient industrial operations.

Use of Embedded Instrument Correlations and Study Limitations

The leak volume rates used as target values in this study are not direct physical measurements from an independent flow meter, but rather estimates calculated by the ultrasonic detector using internal correlations among sound pressure level, probe distance, and flow rate. Because these correlations are proprietary and cannot be fully inspected or modified, the machine learning models effectively learn to reproduce and generalize the instrument’s embedded physical–empirical relationship under real plant conditions. This dependency constitutes a limitation of the present work, as any systematic bias or simplification inherent in the internal instrument model may be propagated to the trained models.

Although the primary output of the regression models is the leak volume rate, several additional indicators were derived to support sustainability-oriented decision-making. Specifically, the predicted leak volume rates were converted to annual leakage quantities by assuming typical operating hours for the compressed air system. The corresponding annual electricity consumption attributable to each leak was then estimated using the compressor’s specific energy consumption. Subsequently, the annual economic loss associated with each leak was calculated using the prevailing electricity tariff, and the associated greenhouse gas emissions were obtained by multiplying the electricity consumption by an appropriate grid emission factor. These derived indicators, expressed in units such as Nm3/year, kWh/year, monetary units per year, and tonne of CO2-equivalent per year, represent leakage volumes within performance metrics that are directly meaningful to plant engineers, energy managers, and sustainability officers. From a modeling perspective, these indicators are algebraically linked to the primary leakage flow prediction; therefore, improvements in regression accuracy directly translate into more reliable estimates of energy, cost, and emission impacts.

Despite this study’s contributions, additional limitations should be acknowledged. The analysis is based on data from a single compressed air system in a single manufacturing facility, which limits the generalizability of the quantitative results to other industrial contexts. Furthermore, the machine learning framework relies on a relatively small dataset and a limited set of predictor variables, namely acoustic emission level and probe distance. As a result, other potentially influential parameters, such as pipe diameter, operating pressure, and background noise conditions, are not explicitly considered in the current model.

Future research should address these limitations by collecting larger, multi-site datasets across diverse industrial facilities and operating conditions. Validating leakage flow rates against independent reference measurement techniques would further enhance model reliability and transferability. Extending the feature set to include operational and environmental variables is expected to improve prediction robustness and generalizability. Beyond operational parameters, incorporating material condition monitoring data represents a promising research direction. In particular, tracking the aging and degradation of sealing materials, such as elastomer gaskets subjected to thermal–oxidative stresses, may enable the identification of early precursors of leakage before detectable acoustic signatures. Recent experimental and numerical investigations of gasket aging provide valuable insights into these degradation mechanisms [53]. Integrating such multi-domain information into advanced machine learning frameworks could support a more comprehensive leakage lifecycle model and facilitate preventive maintenance strategies in sustainable manufacturing systems.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study can be presented in two stages. However, before presenting the results, it should be noted that although four main results are presented in the first stage (leakage rate (V), energy savings (ESL,CAS), cost of leakage air (Cm,air), and annual CFP of leakage air), only leakage rate outputs are presented. This is because energy savings, leakage air cost, and annual CFP were derived using formulas that include the leakage rate. It should be emphasized that the machine learning models were trained solely to predict the leakage flow rate. In contrast, energy savings, cost, and carbon footprint indicators were subsequently derived using established engineering equations. Therefore, the trends of the remaining three output parameters are similar to that of the leakage rate. In the second stage, a comprehensive regression analysis was performed on the energy analysis results using Linear Regression, Bagging Regression Trees, and MARS regression models. Some results from the energy analysis and regression analysis are provided below:

- ✓

- Air leaks ranging from 10 to 140 L/min were detected through the holes in the CAS.

- ✓

- The energy savings potential, initially determined as 20.39 TOE/year, was reduced to 18.77 TOE/year through repairs, resulting in an 8% improvement across the facility. These improvements were valued at €3571.

- ✓

- The CFP, which was 125 t-CO2/year in the initial measurement, was reduced to 115 t-CO2/year with the improvements, contributing 9 t-CO2/year to the overall CFP reduction.

- ✓

- The highest Pearson correlation coefficient (0.83) was observed between the acoustic emission level (dB) and leakage flow rate. This indicates that the acoustic measuring device is more sensitive at close range and that the noise level is directly related to the leakage flow rate.

- ✓

- The bagging method achieved the highest accuracy, with an R2 of 0.846, demonstrating its explanatory power on the test set.

- ✓

- Furthermore, the low MSE (389.85) and MAE (12.134) values indicate that the model is stable not only in overall accuracy but also in error distribution.

Funding

This study is supported by the Firat University Scientific Research Projects Management Unit (FUBAP) under Project Number MF.25.113.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| dB | Sound | decibel |

| CFP | Carbon footprint | t-CO2 |

| ESL,CAS | Energy saving potential | TOE/year |

| V | Leakage flow rate | L/min |

| P | Pressure | Pa |

| WC,S | Specific power of motor | kWh/m3 |

| QV | Free air delivery | m3/min |

| Cm,air | Cost of leakage air | €/year |

| Celectric | Unit price of electricity | €/kWh |

Abbreviations

| CAS | Compressed Air Systems |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| LR | Linear Regression |

| MARS | Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines |

| TOE | Tons of Oil Equivalent |

| CBAM | Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| CEF | Carbon dioxide emission factor |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MARS | Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines |

| € | Euro |

References

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Yu, F.; Yuan, Q.; Sheng, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, D.; Dai, S.; Hou, Z.; Wang, Q. Understanding carbon footprint: An evaluation criterion for achieving sustainable development. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 22, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, G.E.; Weisbach, D. The design of a carbon tax. Harv. Environ. Law Rev. 2009, 33, 499–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Kohlscheen, E.; Nguyen, C.; Volkov, V. Carbon taxation and CO2 emissions: New evidence from panel data. Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107405. [Google Scholar]

- Sitarz, J.; Pahle, M.; Osorio, S.; Luderer, G.; Pietzcker, R. EU carbon prices signal high policy credibility and farsighted actors. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unver, U.; Kara, O. Energy efficiency by determining the production process with the lowest energy consumption in a steel forging facility. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapan, S.; Celik, N.; Camdali, U.; Taskiran, A. Energy and exergy analyses of a submerged arc furnace used for ferrochrome production. Int. J. Exergy 2024, 44, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourin, F.N.; Espindola, J.; Selim, O.M.; Amano, R.S. Energy, exergy, and emission analysis on industrial air compressors. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2022, 144, 042104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Roller, J.; Kim, T.; Barad, D.; Rasmussen, B.P. Experimental Characterization of Compressed Air Nozzles. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Portland, OR, USA, 17–21 November 2024; Volume 8, pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.; Rahim, N.A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. A review on compressed-air energy use and energy savings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, H.H.; Villalba, D.P.; Angarita, E.N.; Ortega, J.L.S.; Echavarría, C.A.C. Energy savings in CASs: A case study. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1154, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medojevic, M.; Petrović, J.; Medojevic, M. Energy Efficiency and Optimization Measures of Compressed Air Systems in Exhibition Hall. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341163957 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Benedetti, M.; Bonfà, F.; Bertini, L.; Introna, V.; Ubertini, S. Explorative study on CASs’ energy efficiency in production and use: Steps towards benchmarking for energy-intensive firms. Appl. Energy 2018, 227, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramoorthy, S.; Kamath, D.; Nimbalkar, S.; Price, C.; Wenning, T.; Cresko, J. Energy efficiency as a foundational technology pillar for industrial decarbonization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Amidpour, M.; Moradi, M.A.; Hajivand, M.; Siahkamari, E.; Shams, M. Technical–economic analysis of energy efficiency solutions for the industrial steam system of a natural gas processing plant. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagman, S.; Soylu, E.; Unver, U. Easy-to-use energy efficiency performance indicators for industrial CAS audits and monitoring. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trianni, A.; Accordini, D.; Cagno, E. Factors affecting adoption of energy efficiency measures within CASs. Energies 2020, 13, 5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Jamil, M.; Ma, P.; He, N.; Gupta, M.K.; Khan, A.M.; Pimenov, D.Y. Ultrasonic-based detection of air leakage in aircraft components. Aerospace 2021, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas Copco. Company Website. Available online: https://www.atlascopco.com/en-eg (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Dindorf, R. Estimating potential energy savings in CASs. Procedia Eng. 2012, 39, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, F.; Cosgrove, J. Optimising CASs in production operations. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2018, 39, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudic, S.; Ignjatovic, I.; Šešlija, D.; Blagojevic, V.; Stojiljkovic, M. Leakage quantification of compressed air using ultrasound and infrared thermography. Measurement 2012, 45, 1689–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Choi, Y.R.; Cho, J.W. Pipe leakage detection using ultrasonic acoustic signals. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 349, 114061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E1002–05; Standard Practice for Leaks Using Ultrasonic Leak Detectors. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2005.

- Celik, N.; Kapan, S.; Tasar, B. Effects of various parameters on entropy generation and exergy destruction using DL neural networks. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 161, 108481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, N.A.; Alshehri, M.A.; Alshaban, E.; Alatawi, A. ML-driven analysis of heat transfer and entropy generation in blood nanofluid flow. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 75, 107136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pambudi, S.; Jongyingcharoen, J.S.; Saechua, W. Explainable ML for activation energy prediction in biomass & biochar. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 75, 107064. [Google Scholar]

- Entezari, A.; Aslani, A.; Zahedi, R.; Noorollahi, Y. AI and machine learning in energy systems: Bibliographic perspective. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2023, 45, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dong, H.; Zheng, W.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Xi, L. Data-driven techniques for load forecasting in integrated energy systems. Appl. Energy 2022, 321, 119269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gao, L.; Lin, Z.; Lian, D.; Lin, Y. ML-based prediction of pollution status in coal-fired boilers. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 74, 106953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Colantonio, E.; Gattone, S.A. Renewable energy consumption, social factors, and health: Panel VAR analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, P.; Wu, H.; Alsenani, T.R.; Bouzgarrou, S.M.; Alkhalaf, S.; Alturise, F.; Almujibah, H. AI-based optimization in compressed air energy storage integrated systems. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.D.O.; Ewbank, H.; Roveda, J.A.F.; Trianni, A.; Marafão, F.P.; Roveda, S.R.M.M. Economic and production implications for industrial energy efficiency. Energies 2022, 15, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doner, N.; Ciddi, K. Regression analysis of operational parameters and energy saving potential of industrial CASs. Energy 2022, 252, 124030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, A.; Daems, W.; Steckel, J. Automated air leakage localization using ML-enhanced ultrasonic and LiDAR-SLAM. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 66492–66504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Xiong, W. Leakage detection in pneumatic systems using ML and upstream signals. Int. J. Fluid Power 2025, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, V.; Jeon, H.-w.; Wang, C. An Integrated Energy Simulation Model of a Compressed Air System for Sustainable Manufacturing: A Time-Discretized Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindorf, R. Study of the Energy Efficiency of Compressed Air Storage Tanks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Junior, M.M.; de Mattos, C.A.; Lima, F. Toward Cleaner Production by Evaluating Opportunities of Saving Energy in a Short-Cycle Time Flowshop. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhe, M.L. Advancing Sustainable Electrical Energy Technologies: A Multifaceted Approach Towards SDG Achievement. Processes 2025, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, K.; Ma, L.; Wang, J.; Dooner, M.; Miao, S.; Li, J.; Wang, D. Overview of Compressed Air Energy Storage and Technology Development. Energies 2017, 10, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-W.; Yoo, D.G. Development of leakage detection model and its application for water distribution networks using RNN-LSTM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Shen, K.; Weng, W. Safeguarding gas pipeline sustainability: Deep learning for precision identification of gas leakage characteristics. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grybós, D.; Leszczy’nski, J.S. Review of energy overconsumption reduction in CASs. Energies 2024, 17, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstencroft, H.R. Ultrasonic Air Leakage Detection: Improving Accuracy of Leakage Rate Estimation. Master’s Thesis, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wurma, S.; Tschepe, T.; Petrovic, O.; Herfs, W. Methodology for accurate product carbon footprint calculation in machining. Procedia CIRP 2025, 135, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Ning, Y.; Cong, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, T.; Shi, X. Quantitative Assessment of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Impacts on China–EU Trade and Provincial-Level Vulnerabilities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsson, J.; Johansson, M.T. Barriers to and Drivers for Improved Energy Efficiency in the Swedish Aluminum Industry and Aluminium Casting Foundries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, S.; Hristea, A.M.; Kailani, C.; Cruceru, A.; Bălă, D.; Pernici, A. Exploring Influencing Factors of Energy Efficiency and Curtailment: Approaches to Promoting Sustainable Behavior in Residential Context. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, E.; Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M. Triple bottom line, sustainability, and economic development: What binds them together? A bibliometric approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; Kishawy, H.A. Sustainable manufacturing and design: Concepts, practices and needs. Sustainability 2012, 4, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, S.-L.; Zhou, A.N. Performance of composite EPDM gaskets for underground structures: Experimental and numerical investigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 500, 143951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.