Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the impact of the digital economy and artificial intelligence (AI) on GDP growth in 10 developed and developing countries during the period 2010–2024. It was based on the hypothesis that increased digitalization and AI investments promote sustainable economic growth by improving national productivity and efficiency, in accordance with modern technological growth theory, which links digital innovation to economic development. The study used tablet data comprising 150 observations, which were analyzed using fixed- and random-effects models, controlling for traditional variables such as employment, human capital, and investment. The results showed that the Digitalization Indicators (DIGI) had a significant positive impact on growth (fixed: 0.003479, p < 0.01; random: 0.003325, p < 0.01), and that investment in AI also had a significant positive impact (fixed: 0.063695, p < 0.05; random: 0.066548, p < 0.05). In contrast, workforce size had a limited impact, while education and human capital emerged as key drivers of sustainable growth (Constant: 0.003257, p < 0.01; Random: 0.003264, p < 0.01). The inclusion of dummy variables further differentiated between developed and developing countries in the random-effects model, reinforcing the economic interpretation of the findings. The study suggests that integrating digitalization, education, and investment in artificial intelligence is an effective strategy for promoting sustainable economic growth, while emphasizing the importance of workforce skills development to maximize its impact.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the global economy has undergone profound structural transformations as a result of the rapid development of information and communication technologies and artificial intelligence applications. The digital economy has become a major driver of economic growth and productivity worldwide [1,2,3]. Digitalization and artificial intelligence have reshaped patterns of production, distribution, and consumption, created new sources of added value, and increased the efficiency of resource allocation within national economies [4,5,6]. However, the economic value of the digital economy and artificial intelligence is not accurately measured in GDP, especially when comparing developed and developing countries, creating a significant knowledge gap in assessing real economic growth [7,8,9].

The integration of intangible assets, such as software, data, algorithms, and intellectual capital, into production processes has also presented conceptual and methodological challenges to traditional accounting frameworks [9,10,11,12]. While advanced economies have achieved tangible productivity gains through digitalization, developing economies face difficulties related to digital infrastructure, human capital, and weak statistical measurement mechanisms [13,14,15,16]. Therefore, assessing the economic impact of artificial intelligence and the digital economy requires updated methodologies that accurately reflect digital productivity within GDP calculations [17,18,19,20]. Recent studies also indicate that artificial intelligence (AI) effectively contributes to improving the efficiency of supply chains and reducing operational risks. Jebbor et al. (2024) observed that AI applications in predicting logistical disruptions enhance productivity and improve resource management, thus supporting economic growth within the context of digital transformation [20].

This study addresses this research gap and aims to analyze the dynamic relationship between digitalization and artificial intelligence development, on the one hand, and economic growth and GDP, on the other. It uses a panel of data from ten countries representing varying levels of economic and technological development: five developed countries (South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Germany, and Finland) and five developing countries (Egypt, Algeria, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia). The study focuses on three main objectives: (1) assessing the impact of the digital economy and artificial intelligence on GDP; (2) examining the differences in this impact between developed and developing countries; and (3) highlighting the need to develop better measurement methodologies for integrating digital productivity into national accounts [21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

In light of recent developments in the System of National Accounts (SNA 2008), Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is no longer limited to measuring traditional physical capital but increasingly reflects the contributions of intangible assets, particularly digital technology, innovation, and knowledge [22,23,24]. The SNA 2008 introduced significant improvements that allow for the inclusion of research and development activities, software, databases, and other components of the digital economy within national accounts as long-term sources of productivity [25,26].

Accordingly, this study uses real GDP at constant prices (US$2015) as an indicator of actual productivity, enabling the measurement of the true impact of digitalization and artificial intelligence within the framework of national accounts, free from accounting distortions resulting from price changes or inflation [27]. This choice contributes to improving the accuracy of economic analysis, particularly in comparative studies between advanced and developing economies, where inflation rates and price structures differ significantly.

Furthermore, using real output aligns with recent literature emphasizing that the impact of the digital economy and artificial intelligence on growth is not fully reflected in nominal measures but is more clearly manifested when analyzing real indicators of productivity and value added (Brynjolfsson et al., 2019; IMF, 2018 [28,29]). Therefore, this methodological approach enhances the credibility of the results and supports the integration of digital activities and artificial intelligence into the overall analysis of national accounts.

The study’s findings aim to provide analytical support to policymakers in designing digital strategies that promote sustainable economic growth and contribute to narrowing the digital divide between developed and developing economies. The remaining sections of the paper are organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature, Section 3 explains the research model, variables, and economic methodology, Section 4 presents and analyzes the experimental results, Section 5 discusses the results and their policy applications, and finally, Section 6 concludes with the findings.

2. Literature Review: A Thematic Analysis of the Digital Economy, Artificial Intelligence, and Economic Growth

In light of the rapid developments in the digital economy and artificial intelligence, a systematic review of the literature addressing the impact of these technologies on economic growth and productivity, as well as the challenges related to national accounting and the digital divide, has become essential. Instead of relying on the traditional chronological order of studies, a thematic aggregation methodology was adopted. This approach examines the impact of digitalization and digital transformation on various dimensions of the economy and society. To facilitate understanding of the literature and connect research findings to key themes, previous studies were divided into four main areas, which are summarized below.

2.1. Digital Economy and Economic Growth

The concept of the digital economy refers to economic activities that rely primarily on digital technologies, such as the internet, big data, cloud computing, and e-commerce platforms. New growth theories (such as the theory of innovation-driven growth—Romer, 1990 [30]) have shown that technology and knowledge constitute a long-term source of economic growth [31,32,33]. In the same context, the digital economy is viewed as a key driver for enhancing efficiency, improving resource allocation, and stimulating institutional innovation. The digital economy has become one of the primary engines of economic growth in the midst of the swift technological changes occurring throughout the world. By increasing productivity, efficiency, and opening up new investment and job opportunities, it is changing the global economy [34,35]. Value chains, production, and services can undergo a structural transformation thanks to digital technologies like artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and the internet, which are used in a variety of economic activities that are included in the digital economy [36,37]. Numerous studies indicate a positive relationship between the development of the digital economy and economic growth, particularly in countries that have successfully adopted effective digital strategies, which have contributed to stimulating innovation, improving the business climate, and expanding the base of economic participation [38,39,40]. In this context, the digital economy emerges as a development lever capable of overcoming traditional constraints to growth, enhancing economic inclusion, and increasing the resilience of economies to external shocks, such as financial or geopolitical crises [41,42].

Digital resources cannot be treated as a linear extension of traditional factors of production such as labor and physical capital, given their distinct economic characteristics and mechanisms of impact on growth. Data, algorithms, software, digital platforms, and artificial intelligence applications are characterized as non-competitive resources in terms of consumption, highly scalable, and possessing a near-zero marginal cost of reproduction after the initial development phase. They also generate increasing returns due to network effects, knowledge diffusion, and the integration of intangible assets, unlike traditional capital, which is often subject to the law of diminishing returns. Furthermore, digital resources do not function as independent inputs of production, but rather play an integrative role that enhances the productivity of both labor and capital simultaneously, and brings about structural transformations in traditional production functions, thus supporting the emergence of self-sustaining growth pathways. These characteristics are consistent with endogenous growth models and general-purpose technology theories, which assert that the long-term impact of digital innovation is embodied through knowledge accumulation, investment in intangible capital, institutional and organizational integration, as well as the non-competitive nature of data and the delayed returns of advanced digital technologies [25,30,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

Modern economic literature focuses on explaining the relationship between the digital economy and economic growth within the framework of endogenous growth theories, which emphasize that innovation, technological advancement, and human capital are key drivers of long-term growth. According to this framework, the digital economy is not merely a technological tool, but rather an integrated system that enhances the productivity of factors of production and supports knowledge accumulation and innovation [50,51,52]. Studies on internal growth confirm that innovation and digital technologies—particularly the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), and mobile technologies—play a pivotal role in boosting economic growth by increasing production efficiency, achieving economies of scale, and enhancing total factor productivity. Edquist et al. (2021) [50] demonstrated that the proliferation of IoT technologies contributes to improving industrial processes through predictive maintenance, automation, and increased inter-sectoral connectivity, positively impacting productivity levels and growth.

According to growth theory, technology diffusion is a key channel for the transfer of growth effects across sectors and regions. The digital economy accelerates this transfer by reducing transaction costs and enhancing connectivity between businesses and markets. Solomon and Van Klyton (2020) [53] demonstrated that the use of the internet and mobile technologies in developing countries, particularly in Africa and Indonesia, has helped integrate less developed regions into the global economy, create new jobs, and stimulate local development.

Numerous studies confirm that investment in digital infrastructure—such as high-speed internet, data centers, and financial technology—is essential for achieving sustainable growth. Kravchenko et al. (2019) [54] noted that countries with robust ICT infrastructure achieve higher rates of economic growth compared to those lagging behind digitally. Fernández-Portillo et al. (2020) [55] also demonstrated that digital transformation increases business efficiency, reduces transaction costs, and improves the quality of decision-making.

In this context, a World Bank study (2021) showed that a 10% increase in internet penetration in developing countries leads to an increase in GDP of between 1.2% and 1.9%, which reflects the direct impact of the digital economy on economic growth [56].

2.2. Artificial Intelligence and Productivity (AI)

Artificial intelligence plays a crucial role in enhancing labor productivity and developing industrial value chains. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) report confirmed that digital transformation strengthens global value chains and creates high-value-added jobs, while emphasizing the need for comprehensive policies to ensure the equitable distribution of benefits. Furthermore, pilot studies in Africa have shown that investment in digital platforms in countries like Nigeria and Kenya has contributed to the emergence of new economic sectors, the creation of high-value-added jobs, and increased growth rates [57,58]. Recent evidence suggests that artificial intelligence (AI) not only boosts productivity but also contributes to cleaner production and sustainable industrial practices. Studies such as Jebbor et al. (2025) and Revolutionizing Cleaner Production Jebbor, I., Z. Benmamoun (2024) demonstrate how AI applications can improve resource utilization, reduce emissions, and increase process efficiency across various industries [20,21].

International applied literature indicates a growing positive relationship between the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and improved productivity levels. However, this relationship is neither linear nor uniform across countries and sectors. Reports from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2025) confirmed that AI contributes to increased labor productivity through intelligent automation, improved resource allocation, and data-driven decision-making [59]. However, its positive impact is contingent upon the availability of a qualified workforce and advanced digital infrastructure. Similarly, the McKinsey Global Institute (2018) estimated that AI applications could increase global labor productivity by 0.8% to 1.4% annually, reflecting its significant potential as a driver of long-term growth [60].

However, more in-depth studies indicate that the productive impact of artificial intelligence (AI) may be delayed and heterogeneous. Brynjolfsson et al. (2021) demonstrated that AI investments do not lead to immediate productivity gains, but rather follow a J-shaped productivity curve, requiring complementary investments in skills, organizational structure, and intangible capital before their full positive effects are realized [48]. This argument is reinforced by Aghion et al. (2017), who classified AI as a general-purpose technology (GPT), whose productive impact is strongest when integrated within a comprehensive innovation ecosystem that supports research and development and human capital development [61]. A study by Murthy et al. (2021) demonstrated a positive correlation between artificial intelligence indicators and GDP and GDP per capita in both developed and developing countries [62]. However, this effect was more pronounced in developed economies, indicating a widening digital productivity gap between nations. Furthermore, the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2023 [63]) warned that while AI can boost productivity, it could exacerbate economic inequalities if not supported by robust education policies and a flexible labor market capable of reskilling the workforce [64].

In the context of advanced digital technologies, recent literature points to the growing role of digital twins and metaverse technologies in supporting sustainable and circular economic systems. Jebbor et al. (2025) [65] indicated that integrating digital twins with metaverse environments enables real-time simulation of economic systems, optimization of production processes, and more efficient resource management. These technologies also contribute to enhanced decision-making, reduced waste, and improved efficiency in value chains, positively impacting the long-term sustainability of economic operations. These digital innovations represent an advanced stage of digital transformation and strengthen the link between digitalization, artificial intelligence, and economic sustainability [65].

Recent empirical findings confirm that the relationship between artificial intelligence (AI) and productivity is neither linear nor homogeneous, but rather subject to structural and institutional constraints that reflect varying levels of digital readiness across economies. Studies by Brynjolfsson et al. (2021) [48] and Acemoglu & Restrepo (2018) [47] have shown that AI investments follow a J-shaped productivity curve, requiring adjustment periods involving complementary investments in skills, organizational structures, and intangible capital before tangible productivity gains are realized. Furthermore, findings by Autor et al. (2019) [66] and the OECD (2025) [67] indicate that advanced economies benefit more from AI than developing economies, reflecting the widening global digital productivity gap. This evidence supports the argument that AI is not an automatic driver of growth, but rather requires an institutional and educational environment capable of absorbing technological shocks and transforming them into sustainable productivity gains, as the IMF (2023) has cautioned [68].

2.3. National Accounting Challenges in the Digital Age

Traditional national accounts face methodological difficulties in measuring the economic value of modern digital activities, particularly those that do not generate direct revenue or lack a clear market for pricing. A major challenge is measuring the economic value of free digital services, such as Google, Facebook, and social media, which enable consumers to access significant benefits without direct monetary exchange [69]. Consequently, these services are often excluded from GDP calculations, despite their clear impact on economic well-being and productivity. Research in national accounting indicates that the United Nations Statistical Commission and the International Monetary Fund are working to update their measurement approaches, but traditional methodologies still suffer from gaps in accounting for these digital services within GDP, potentially leading to an underestimation of the true growth of the digital economy [70]. Research also underscores the importance of integrating intangible capital, including software, data, and digital innovation, into productivity and growth measurements, as neglecting these components leads to underestimates of GDP (Corrado et al., 2009; Brynjolfsson et al., 2003) [25,71]. Furthermore, OECD (2019) and UNCTAD (2021) reports indicate that digital trade, data exchange, and cross-border services further complicate the measurement of the digital economy’s contribution to traditional GDP [72,73].

Most current national accounts systems rely on traditional concepts of physical goods and services, making them unable to capture a significant portion of the economic value generated by digital assets, or the “invisible economy” driven by digital platforms. This underestimates the contribution of the digital economy and AI to GDP, particularly in developing countries that lack accurate measurement mechanisms.

Intellectual Property and Knowledge Assets Flows Across Borders

The 2008 System of National Accounts classifies intellectual property assets into five categories:

- Research and development;

- Mineral exploration and appraisal;

- Computer software and databases;

- Original entertainment, literary, and artistic works;

- Other intellectual property assets. (Subject: Other intellectual property products.)

With the exception of mineral exploration and appraisal, intellectual property products are subject to extensive international trade. As demonstrated by the OECD study on base erosion and profit shifting, intellectual property products have increased firms’ ability to transfer the registration (legal ownership) of their products from one (high-tax) jurisdiction to another (low-tax) jurisdiction, thereby transferring the inherent added value generated by these assets. Figure 1 below illustrates the classification of knowledge-based assets.

Figure 1.

Classification of Knowledge-Based Assets. * Contains assets currently capitalized in the official measure of investment. Source: Corrado, Hulten and Sichel (2005) [74].

Therefore, a key challenge lies in including free digital services, data, and digital innovation within traditional GDP measurements. Current measurement gaps may lead to underestimates of real digital growth, necessitating the development of new metrics that account for indirect economic value and non-monetary productivity.

2.4. The Digital Divide and Related Studies

Digital access gaps remain a major obstacle to achieving inclusive and sustainable economic growth. A comprehensive study in Asia showed that e-commerce contributes positively to boosting international trade, but uneven ICT infrastructure limits the benefits that less developed countries and regions can derive from digital integration (Chen et al., 2020 [75]). Using Digital Development Index data for 30 Asian cities during the period 2015–2019, another study demonstrated that technological progress contributes significantly to economic growth, but this progress varies between eastern and northern regions compared to central and western regions, reflecting a geographical digital divide that affects the distribution of the benefits of the digital economy Feng and Qi, 2024 and Zhang et al., 2021 [76,77].

The literature confirms that the digital divide encompasses both infrastructure and digital skills. An OECD report (2022) indicates that a lack of digital skills in the workforce reduces individuals’ ability to benefit from digital transformation, while technological education and training provide greater economic participation and reduce digital inequalities [78]. Similarly, the UNCTAD report (2021) indicated that policies promoting equitable access to digital infrastructure, developing digital skills, and removing regulatory barriers are essential to ensuring inclusive and sustainable growth that reduces the digital divide between countries and regions [57].

Other studies supporting this trend include Van Deursen & Van Dijk (2019), which demonstrated that the digital divide encompasses three main dimensions: technological access, digital skills, and the ability to utilize digital services, impacting productivity and economic well-being [79]. Hilbert (2016) also pointed out that the global digital divide between developed and developing countries directly impacts opportunities for economic growth and digital innovation [80]. Hargittai & Hinnant (2008) showed that individuals’ level of education and digital skills determine their ability to capitalize on digital opportunities, reinforcing the need for targeted education policies to bridge the digital divide [81]. Hence, the literature confirms that the main challenges of the digital divide lie in the disparity in digital infrastructure and skills, and that addressing this divide requires comprehensive policies that combine the development of digital infrastructure, education and training in digital skills, and support for digital integration to ensure that all regions and groups benefit from digital growth.

Despite the relatively rich literature on the digital economy, artificial intelligence, and economic growth, most previous studies have addressed these issues in a fragmented and piecemeal fashion. They have focused either on the impact of digitalization or AI on growth and productivity, or discussed measurement challenges in national accounts in isolation from the systematic interaction between these elements. Furthermore, much of this literature has relied on homogeneous samples limited to either developed or developing countries, thus hindering the ability to explain the structural gaps in digital productivity between the two groups. In addition, the interactive relationship between AI, human capital, investment, and the labor market has not received sufficient attention within a unified framework that integrates these variables into the measurement of real output. Based on these gaps, the current study seeks to make an original contribution by integrating AI-driven productivity and the digital economy within the framework of national accounting, through an applied standard model that uses a comparative sample of five developed and five developing countries, and tests the combined impact of the digital economy, AI, investment, labor, and human capital on real GDP, allowing for a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the structural differences in the effects of digital transformation between developed and emerging economies.

3. Materials and Methods

To answer the problem posed and test and prove the validity of the formulated hypotheses, we decided to adopt the descriptive approach with its analysis tool so that we could describe the various concepts and theories related to Measuring the Impact of the Digital Economy and Artificial Intelligence on GDP and Economic Growth: Towards Developing National Accounts Methodologies in the Digital Age. This is in the theoretical aspect of the research. As for the applied aspect related to the econometric study, we will rely on the experimental approach with its measurement tool by Measuring the Impact of the Digital Economy and Artificial Intelligence on GDP and Economic Growth: Towards Developing National Accounts Methodologies in the Digital Age. The study also adopts a comparative approach between two groups of countries, developing countries (Egypt, Algeria, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia). and technologically advanced countries (South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Germany, and Finland), to extract variations in impact and identify structural and institutional determinants. Annual data covering the period (2010–2024) was collected from reliable sources.

3.1. Applied Analysis

We assume that real GDP (or economic growth rate) depends on a combination of traditional factors as well as indicators of the digital economy and artificial intelligence.

Basic linear model:

where

Real GDP (GDP at constant 2015 US$).

: A measure of the growth of the digital economy (e.g., the World Bank’s Digital Economy Index, the percentage of internet users, or the amount of e-commerce).

It helps to separate the impact of developed and developing countries on GDP, it allows for a comparison of the structural effects of the digital economy and artificial intelligence between two different groups of countries. And it facilitates the verification of a clear digital divide between developed and developing economies within the statistical model.

For example, AI investments as a percentage of GDP and number of AI patents.

Investment rate as a percentage of GDP.

: Employment size or labor force participation rate.

HEDUt: The index of human capital, which includes the rate of tertiary education.

DUM1 = 1 if the country is developed (South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Germany, Finland).

DUM0 = 0 if the country is developing (Egypt, Algeria, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Armenia).

An unobserved effect that varies by country.

: Random error.

The statistical methodology used in this study relied on panel data models due to their high predictive accuracy. These models take into account the effects of time variability and the effect of variance between elements. The panel data models will be constructed according to the following steps [82,83]:

- −

- Homogeneity test (Hsiao test).

- −

- Stationarity study of the panel data models.

- −

- Estimation of the panel data models.

- −

- Selection of the appropriate model.

- −

- Examination of the model’s suitability.

- −

- Analysis of the results of the model estimation.

The steps are as follows:

If we have N cross-sectional observations over a time period T, then the panel data models take the following form [84]:

where

Yit: The value of the dependent variable in observation i at time interval t.

: The value of the intersection point in observation i (constant).

βj: The value of the slope of the regression line.

: The independent variable j in observation i at time interval t.

: The value of the error in observation i at time interval t.

Using panel data models requires first verifying the homogeneity of the data under study and the feasibility of applying these models. This is done through the Hsiao test, introduced in 1986. The test is administered in three stages as follows [85]:

- −

- Overall homogeneity testing phase:

That is, verifying that the constants α and coefficients are identical according to the following hypothesis:

The decision is made based on Fisher’s (f) statistical value, which is calculated according to the following formula:

where : the sum of the squared residuals for the unconstrained model. The sum of the squared residuals for N units (countries) for each observation T is equal to:

SCR1,c: The sum of the squares of the remainders of the constrained model (in the case of the constrained model, only one equation is estimated for all countries together, by combining all observations, and then calculating the sum of the squares of the remainders) under hypothesis is used to estimate the model by combining all observations: N: number of countries, T: number of years, K: number of model coefficients.

If is accepted, the optimal model is the overall (constrained) homogeneity model.

If is rejected, we move to the second stage to determine if the heterogeneity stems from differences in coefficients between the countries.

- −

- Parameter homogeneity testing phase

That is, determining whether the heterogeneity originates from the coefficients or not.

This is done according to the following assumption:

The decision is made based on Fisher’s () statistical value, which is calculated according to the following formula:

SCR2,c: The sum of the squares of the remainders of the constrained model (in the case of the constrained model, only one equation is estimated for all countries together, by combining all observations, and then calculating the sum of the squares of the remainders) under hypothesis is used to estimate the model by combining all observations: N: number of countries, T: number of years, K: number of model coefficients.

If is accepted, the optimal model is the overall (constrained) homogeneity model.

If is rejected, we move to the second stage to determine if the heterogeneity stems from differences in coefficients between the countries.

- −

- Constant homogeneity testing phase

Any test of the equality of individual constants under the assumption that coefficients are common to all items, is carried out according to the following assumption:

The decision is made based on Fisher’s () statistical value, which is calculated according to the following formula:

In the case of rejection , we obtain a segmental time series model with individual effects, which is represented by the following formula:

3.1.1. Studying Static Nature of Panel Data Models

After confirming the applicability of the time series models, the second step is to ensure the stability of the time series used in the model under study. If these series are not stable, their use in estimation will lead to misleading, and sometimes even erroneous, results. To achieve this, we will use the following tests and apply them to each of the study variables: the LLC test proposed by Levin and Lin et al. (2002) [86], the IPS test proposed by Im and Pesaran et al. (2003) [87], and the ADF–Fisher test.

The null hypothesis for the three tests (ADF, IPS, LLC) is that the unit root exists, meaning the time series is not stationary. The alternative hypothesis is that the unit root does not exist, meaning the time series is stationary. If the value of p-value is less than the specified significance level of 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis, i.e., the time series is stationary.

- −

- Pooled Regression Model (PRM)

This model is considered the simplest of the panel data models, where all coefficients are constant for all time intervals; i.e., the effect of time is neglected. By reformulating Equation (4), we obtain the pooled regression model in the following form:

where E() = 0 Var() =

The model is estimated using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method.

- −

- Fixed-Effects Model (FEM)

The fixed-effects model determines the behavior of each cross-sectional dataset individually by making the parameter different from one set to another, while keeping the slope coefficients constant for each cross-sectional dataset. Therefore, the model takes the following form:

The term constant effects indicate that the value of the α for each cross-sectional dataset does not change over time; rather, the change occurs only within the cross-sectional datasets themselves. The model is estimated using the least squares method of dummy variables (LSDV) by adding (N − 1) dummy variables. After adding these variables, the model takes the following form:

where the quantity + represents the change in the cross-sectional groups for the parameter α.

3.1.2. Random-Effects Model (REM)

In the fixed-effects model, the error limit has a normal distribution with a mean of zero and a variance of . For the parameters of the fixed-effects model to be valid and unbiased, the error variance must be constant for all cross-sectional views, and there must be no autocorrelation between any set of cross-sectional views within a given time period. If none of the above conditions are met, the random-effects model will be used. Randomness.

In a random-effects model, the cutoff value is treated as a random variable with a constant value µ. Therefore:

Thus, we find that the random-effects model takes the following form:

where represents the error limit in the cross-sectional dataset i, expressing the random deviations of each dataset during the time period due to factors outside the model limits. The model is estimated using the Generalized Least Squares (GLS) method.

3.1.3. Choosing the Appropriate Model

When considering individual effects in model (6), based on the results of Hsiao’s homogeneity test, it is necessary to choose between the fixed-effects model and the random-effects model. This is done through Housman’s test, as follows [88]:

: The random-effects model is the appropriate model. : The fixed-effects model is the appropriate model.

The test statistic (H) is then calculated as follows:

where

The variance vector for the parameters of the fixed-effects model.

: The variance vector for the parameters of the random-effects model.

If the value of (H) is greater than the tabulated value of in degrees of freedom K, then is rejected, meaning that the fixed-effects model is the appropriate model, and vice versa.

To provide a clear overview of the variables used in this study and their respective data sources, Table 1 summarizes the definitions and sources for all key variables employed in the analysis.

Table 1.

Definition of Variables and Data Sources.

3.2. Digitalization and National Accounts

This study does not include differences in national accounts systems between countries as an explicit independent variable, as these differences are relatively fixed structural characteristics for each country during the study period. Instead, they are implicitly controlled using fixed effects and time-fixed-effects models, which absorb country-wide variations in national accounts methodologies, statistical capacities, and the level of integration of digital activities. Thus, the standard estimates are based on changes within a single country over time, allowing for the measurement of the true impact of digital productivity and artificial intelligence on real GDP.

Study Hypotheses:

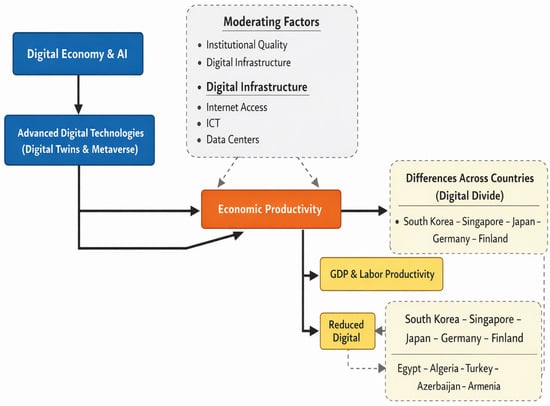

This study is based on an endogenous growth framework that posits the digital economy and artificial intelligence as key drivers of economic growth through improved productivity and fostered innovation. Accordingly, the study assumes a positive impact of the digital economy (H1) and artificial intelligence (H2) on real GDP. However, the strength of these impacts varies among countries depending on their level of digital readiness and human capital, reflecting a clear digital divide between developed and developing economies, as outlined in the third hypothesis (H3). Figure 2 illustrates these relationships and contextual differences among the countries under study.

Figure 2.

The conceptual framework for the relationship between the digital economy, artificial intelligence, and economic growth, with digital disparity between countries. Source: Prepared by the authors based on previous studies.

H1.

There is a statistically significant positive impact of the digital economy on GDP.

H2.

There is a positive impact of artificial intelligence on economic growth.

H3.

There are significant differences between the four countries that reflect the digital divide.

The conceptual diagram (Figure 2) illustrates the relationship between the digital economy, artificial intelligence, and advanced digital technologies such as digital twins and metaverse technologies, and their impact on economic productivity and growth. The model shows that the digital economy and artificial intelligence are the primary drivers of productivity enhancement and digital innovation, while advanced digital technologies improve operational efficiency and resource management, thereby supporting economic performance and reducing the digital divide between countries. The model also highlights the role of moderating variables such as institutional quality (governance, rule of law, anti-corruption) and digital infrastructure (internet, ICT, data centers) in either enhancing or limiting the impact of these technologies. Furthermore, the diagram illustrates the differences between developed countries (South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Germany, Finland) and developing or emerging countries (Egypt, Algeria, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Armenia) in the impact of digitalization on productivity and growth, emphasizing the importance of improving digital infrastructure and institutional quality to bridge the digital divide and promote sustainable economic development. This model is based on recent literature on Digital Twins (Jebbor, Benmamou, 2025 [89]) and shows how advanced digital technologies can be effective tools to support the circular economy and sustainable systems.

4. Results

4.1. Estimating and Analyzing Results

The descriptive statistical results presented in Table 2 indicate a significant disparity in the levels of economic and technological variables among the sample countries during the period 2010–2024. This reflects the different stages of economic and digital development between developed and developing economies. For example, the Digitalization (DIGI) ranges from 12.5 to 97.9, with a mean of 69.6 and a standard deviation of 22.3, demonstrating wide gaps in digital infrastructure levels among the sample countries. Similarly, the Artificial Intelligence (AI) variable shows considerable variation, with values ranging from 0.15 to 5.35, and a mean of 1.86, reflecting the varying capacities for adopting and utilizing AI technologies across the countries under study.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Variables for a Panel of Developed and Developing Countries (2010–2024).

The variation in the investment variable (INV) reflects differences in production structures and levels of physical capital accumulation, ranging from 12.0% to 51.8%, with a mean of 26.4%. The labor force variable (LAB) ranges from 39.6% to 70.7%, indicating structural differences in labor markets and levels of economic participation across countries. The higher education variable (HEDU) exhibits the greatest degree of relative dispersion, with values ranging from 19.3% to 127.9%, a mean of 68.0%, and a relatively high standard deviation of 28.1. This highlights the heterogeneous role of human capital in supporting digital transformation and enhancing the economic impact of modern technologies.

It is also noteworthy that the relatively high standard deviations for the digitization (DIGI), artificial intelligence (AI), and higher education (HEDU) variables reflect a high degree of heterogeneity within the tablet sample. This methodologically supports the suitability of using standard models that account for structural heterogeneity among countries, allowing for more accurate short- and long-term impact analysis. Based on this variability among the sample countries, the following section of the study employs a set of standard models appropriate for the tablet data to analyze the relationship between integrating digital and AI-driven productivity into national accounts and economic performance, taking into account the structural differences between advanced and developing economies.

To validate the econometric analysis used in this study, it is essential to verify the stationarity of the variables. The extended Dickey–Fuller test (ADF) was used to determine whether the time series for each variable contained a unit root, which indicates non-stationarity. The results of this test are presented in Table 3, showing the ADF statistics, the corresponding p-values, and the decision on stationarity at a significance level of 5%. These results provide important information regarding the suitability of the variables for use in regression models and cross-sectional and time-based data analysis. Stable variables can be used directly in their original form, while non-stationary variables may require transformations such as differentiation to avoid spurious regression results.

Table 3.

ADF–Fisher Chi-square stability test results.

The results of the ADF–Fisher chi-square test, presented in Table 3, indicate that all study variables are non-stationary at the level, but become stationary at the first difference. This implies that the variables are first-order integrals (I(1)). This finding is methodologically significant in the context of panel models, as it reflects the dynamic characteristics of the time series under study. Therefore, the study’s subsequent econometric analysis relies on fixed-effects (FE) and random-effects (RE) models, addressing the non-stationary issue. This is achieved either by using the variables as their first differences or by incorporating appropriate time trends, thus avoiding spurious regression and ensuring the consistency of the estimates. The fixed-effects model allows for the control of unobserved, time-constant properties for each country—such as institutional and structural factors—that may be associated with explanatory variables. In contrast, the random-effects model assumes that these unobserved properties are independent of the explanatory variables. Consequently, the two models will be compared using the Hausman test to select the most efficient and consistent estimate. Therefore, combining the results of the static test and using the FE and RE models provides a suitable standard framework for analyzing the impact of digitalization, artificial intelligence, investment and human capital on economic growth, taking into account the structural differences between developed and developing countries within the study sample.

To assess the existence of a long-term syntegration relationship between RGDP and the digital economy, artificial intelligence, human capital, investment, and employment, the Pedroni test for residual integration was performed on sample data (10 countries, 2010–2024). The Null Hypothesis: No Cointegration was adopted, assuming a deterministic intercept and trend, and automatic interval lengths were used according to the MSIC criterion with a maximum interval of 1.

The results of the test within the shared dimension indicate statistical significance for several indicators, such as Panel v-Statistic, Panel PP-Statistic, and Panel ADF-Statistic, at the 1–5% levels, while the results between the dimensions provide further support for cross-country syntegration relationships. These results confirm a stable long-term relationship between the variables, justifying the use of regression at levels in both fixed- and random-effects models and enhancing the credibility of long-term economic interpretations.

Table 4 shows the results of the Pedroni cointegration test for digital, structural, and human economic variables over the period 2010–2024 for a sample of 10 countries. The results show that some statistics, such as Panel v-Statistic (p = 0.0000), Panel PP-Statistic (p = 0.0013), and Group PP-Statistic (p = 0.0000), strongly reject the null hypothesis of the absence of cointegration, indicating a long-term equilibrium relationship between GDP and factors of investment, digitalization, artificial intelligence, labor force, and human capital.

Table 4.

Results of the Pedroni cointegration test.

In contrast, some statistics, such as Panel rho-Statistic (p = 0.9872), did not show statistical significance, which is typical in this type of test and reflects the varying strength of the relationship across different dimensions (within-dimension and between-dimension).

In general, it can be concluded that the main variables of the study are related to each other in the long term, which enhances the credibility of using cross-sectional regression models (Fixed & Random Effects) in analyzing long-term effects on GDP, and reduces the risk of spurious regression resulting from the use of non-integrated variables at their levels.

From the previous table, it is clear that p < 0.05, so we reject the homogeneity of variance hypothesis → there is heterogeneous variance in the data.

The Breusch–Pagan test was conducted to examine the homogeneity of variance hypothesis in the regression model used in this study, which addresses the impact of digitalization (DIGI), artificial intelligence (AI), investment (INV), labor force (LAB), and higher education (HEDU) on real GDP (lnRGDP) for the selected sample of countries. The test results showed an LM statistic of 3.87 with a p-value of 0.425, while the F statistic was 1.12 with a p-value of 0.358. These values clearly indicate that the homogeneity of variance hypothesis cannot be rejected at a significance level of 5%, meaning that the error variance in the model is constant across all observations.

Therefore, the results confirm that the basic assumption of linear regression is valid, supporting the use of both fixed-effects and random-effects models in analyzing the relationship between the studied economic variables. This finding strengthens the validity of the conclusions drawn regarding the impact of digitalization, AI, investment, labor force, and higher education on the economic performance of the sampled countries.

To check for multicollinearity among the independent variables, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used. Multicollinearity is one of the most significant problems facing regression models, as it refers to the presence of a strong linear relationship between two or more independent variables in the model. This problem inflates the variance in parameter estimates, reducing the accuracy of their estimation and weakening the power of statistical tests. The VIF measures the extent to which the variance in the coefficient estimate of each independent variable is inflated by its correlation with other variables. The decision rule is based on the premise that VIF values less than 10 indicate no serious multicollinearity problem, while values greater than 10 indicate a problem that must be addressed. This can be illustrated in the following Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the multiple correlation test between independent variables using the variance inflation factor (VIF).

The regression model was checked for multicollinearity using the VIF test. The results showed that all independent variables fell within the acceptable range (<10), indicating that the model can reliably infer the effect of each variable on lnRGDP without fear of error amplification or distortion of estimates.

4.2. Results of the Linear Regression Model and Testing of the Study Hypotheses

Based on the study hypotheses, which assume a positive and significant impact of the digital economy on GDP (H1), a positive impact of artificial intelligence on economic growth (H2), and the existence of structural differences between countries reflecting the digital divide (H3), a linear regression model was estimated using balanced panel data covering 10 countries during the period 2010–2024, with a total of 150 observations. This model aims to test the combined impact of digitization indicators, artificial intelligence, and the dummy variable representing differences between countries on economic performance. Table 6 presents the results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the estimated model, allowing for an assessment of the overall significance of the model and its empirical support for the study hypotheses.

Table 6.

Results of the Linear Regression Model Estimating the Impact of Independent Variables on GDP.

Table 6 presents the results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for a linear regression model using a balanced panel of 150 observations. The aim was to evaluate the explanatory power of the independent variables combined to explain changes in real GDP. The results show that the model has a high degree of statistical significance, with an F-value of 54.88865 at 6 and 143 degrees of freedom, and a significance level of less than 1%. This rejects the null hypothesis and confirms the existence of a statistically significant combined effect of the explanatory variables on GDP.

The R-squared value of 0.697 indicates that approximately 69.7% of the changes in GDP can be explained by the independent variables included in the model. The adjusted R-squared value of 0.6614 reflects the model’s efficiency after correcting for the number of variables and sample size. The small difference between the two values indicates that the added variables, including the dummy variable, effectively contribute to improving the explanatory power of the model.

In terms of analysis of variance, the Model SS totaled approximately 324.822 out of a total of 465.202 total variance squares, while the Residual SS totaled only 140.380, indicating that the unexplained portion of GDP changes is relatively small. The significant difference between the Model SS mean (MS = 54.137) and the Residual SS mean (MS = 0.981) reflects the model’s high explanatory power, which explains the high F-statistic.

The Root MSE value of 0.9908 confirms the low mean estimation error of the model, demonstrating its good fit and predictive accuracy. Based on these results, hypotheses H1 and H2, which posit a positive and significant impact of both the digital economy and artificial intelligence on economic growth, can be accepted. Furthermore, the significance of the dummy variable supports hypothesis H3, which relates to structural differences between countries reflecting the digital divide. In general, the results indicate that digitalization and artificial intelligence are pivotal factors in explaining economic performance, consistent with the theoretical framework of the study and previous literature.

4.3. Estimation of Cross-Sectional Time Series Models

Three models were estimated: the PRM (Plugin Regression Model), the FEM (Fusion Effects Model), and the REM (Riot Effects Model). Table 7 shows the estimation results.

LNRGDP = 32.0102198998 − 0.0217177752767 × DIGI + 0.933222317564 × AI − 0.0275174275188 × INV − 0.0992884882723 × LAB + 0.00357527087546 × HEDU + 1.31645306499 × DUMMY

Table 7.

Results of Parameter Estimation for Panel Data Models Programmed Regression Mechanism (PRM Dependent Variable: RGDP).

Table 7 presents a linear regression model using Panel (PRM) data to estimate the impact of independent variables on the real GDP of the ten countries during the period 2010–2024. The results indicate that the independent variables collectively explain approximately 69.7% of the changes in GDP (R2 = 0.697), with high statistical significance for the model as a whole (F = 54.889, p = 0.000), confirming the model’s suitability for testing the study’s hypotheses. For the individual variables, artificial intelligence (AI) appears to have a significant positive impact on GDP (β = 0.933, p < 0.01), while the dummy country variable (DUMMY) is also positively significant (β = 1.316, p < 0.01), reflecting structural differences between the countries that reflect the digital divide. Conversely, digitalization (DIGI), investment (INV), and labor force (LAB) showed statistically significant negative effects on GDP, while human capital (HEDU) was not statistically significant, suggesting that the impact of these variables depends on the quality of technology use and the economic transformation of countries. The low mean estimation error (S.E. = 0.991) reflects the model’s accuracy in estimating GDP, although the autocorrelation probability of residuals (Durbin–Watson = 0.026) needs to be addressed to ensure more reliable conclusions. Therefore, the model supports the hypothesis that artificial intelligence and the digital divide between countries impact economic growth. However, the results indicate the need for further analysis to understand the nature of the impact of digitalization, investment, and labor force on GDP, particularly in the context of varying levels of technology adoption and utilization efficiency across countries.

The Hsiao test was performed to check for individual effects and determine whether there were significant differences between countries and time periods. The test aimed to determine whether a pooled regression model was sufficient or whether a fixed-effects (FE) or random-effects (RE) model was more appropriate for the pooled data. The results below demonstrate the importance of the effects of countries and periods, both independently and collectively, justifying the use of a fixed-effects model for estimating the coefficients of the economic variables.

To assess the presence of redundant fixed effects in the model, we applied the Hsiao Test. Table 8 presents the test results, including F-statistics and Chi-square statistics for cross-section effects, period effects, and combined cross-section, period effects.

Table 8.

Hsiao Test (Redundant Fixed-Effects Test) Results Table.

The table above shows the results of the Hsiao test for Individual Effects, which aims to assess whether there are significant differences between countries and time periods in the dataset. The results of the cross-sectional test for countries indicate strong statistical significance (F = 4308.561, Chi-square = 865.936, p < 0.001), meaning that the differences between countries are not negligible. Similarly, the period tests showed a significant effect (F = 2.713, Chi-square = 40.950, p < 0.01), indicating significant temporal variations in the dependent variable. The cross-sectional/period tests also confirm the significance of the effects independently and combined (F = 1713.892, Chi-square = 868.394, p < 0.001).

These results suggest that the Pooled Regression model is inadequate for accounting for differences between time units and countries, thus justifying the use of the Fixed-Effects (FE) model for estimating the coefficients of economic variables. However, it should be noted that including a fixed DUMMY variable for each country is not feasible within the FE model, and if the study wishes to include it, the Random-Effects (RE) model is the more appropriate alternative.

Based on the results of the homogeneity test (Hsiao), the estimation results of the pooled regression model (PRM) were excluded, as the test results indicate that the model used in the study is a single-effects model. After considering single effects in the model, it was necessary to examine the nature of this effect. The first stage of the analysis involved identifying the type of effects used for the parameter αi, specifically whether it tracked a random effect (components of error model) or a determined effect (fixed-effects model). Therefore:

- −

- Fixed-Effects Model: Assumes that each country has a fixed threshold. The dummy variable is not considered.

- −

- Random-Effects Model: Assumes that each country has a different threshold.

4.4. Estimating the Fixed-Effects Model

Based on the results of Hsiao’s Individual Effects Test, which demonstrated the significance of differences between countries and time periods, a Fixed-Effects model was adopted to estimate the relationship between economic variables and real GDP (LNRGDP). This model allows for control of country-specific and time-period constants, ensuring that observed changes in the dependent variable reflect the actual effects of independent variables such as digitalization (DIGI), artificial intelligence (AI), investment (INV), labor force (LAB), and education (HEDU). The following table presents estimates of the Fixed-Effects model coefficients, along with statistics on the quality of fit and the significance of each variable in explaining changes in GDP across the studied sample.

Table 9 clearly shows the results of the Fixed-Effects model for LNRGDP, providing a detailed illustration of the impact of economic, digital, and human variables on sustainable economic growth. The table shows that the constant C is estimated at 26.06703, which is highly significant (p < 0.01). This indicates a baseline for GDP assuming all independent variables are constant, reflecting the baseline on which the effects of all other variables are measured.

Table 9.

Results of the Panel Fixed-Effects model estimation for the dependent variable LNRGDP.

Regarding Digital Transformation (DIGI), the positive coefficient 0.003479 is also highly significant (p = 0.0001), meaning that an increase in the digitization index is associated with a significant rise in GDP. This supports the study’s hypothesis that digitization enhances economic efficiency and national productivity. Artificial intelligence (AI) registered a significant positive coefficient of 0.063695 at a p < 0.05 level, indicating that investment in advanced technologies stimulates economic growth, although its impact is less pronounced than that of comprehensive digitalization.

On the other hand, labor force size (LAB) did not show a significant impact on growth, with a coefficient of −0.0000533 and a p = 0.9914, demonstrating that simply increasing the number of workers does not guarantee an increase in output without improving efficiency or skills. In contrast, human capital (HEDU) demonstrated a clear and positive impact, with a highly significant coefficient of 0.003257 (p < 0.01), confirming the importance of education and training in promoting sustainable growth, consistent with the assumptions of the endogenous growth model.

Looking at the Labor Force Index (LAB), we find it to be negative and insignificant (−0.0000533, p = 0.9914). This structural reality reflects the fact that the size of the workforce alone does not guarantee increased productivity or economic growth unless it is coupled with improved digital and technical skills and competencies. In contrast, the Human Capital Index (HEDU) stands out as positive and significant, confirming that investment in education and training is the true driver of sustainable growth. These results demonstrate that digital economic policies should focus on enhancing workforce efficiency and linking it to digital and educational capabilities, rather than simply increasing the number of workers, in line with modern economic theory of knowledge- and technology-led growth.

The model’s statistics demonstrate its strong internal explanatory power, with an R-squared (within) of 0.6245. This means the model explains approximately 62% of the changes within countries over time, while the inter-country variability remains low (R-squared between = 0.0454), indicating that time-related differences within a single country are more significant than differences between countries. Furthermore, the F-statistic of 21.62 with Prob > F = 0 confirms the overall significance of the model, while the rho value of 0.9908 suggests strong fixed effects for each country, justifying the use of a fixed-effects model.

Based on these results, it can be concluded that the most influential factors on sustainable economic growth in this sample are digitalization and human capital. The size of the workforce remains less important unless accompanied by improvements in skills and training. The impact of artificial intelligence also reflects the need to invest in modern technology to enhance productivity and economic efficiency, consistent with the research’s theoretical hypotheses on sustainable growth and digital innovation.

To present the results of the GLS random effects regression model estimation, Table 10 summarizes all the model’s key values, including the estimated coefficients, standard deviation, t-statistic, p-values, 95% confidence intervals, and the statistical significance level for each variable. This table reflects the impact of the Digital Economy Index (DIGI), the Artificial Intelligence Index (AI), investment, employment, education, and other variables on the dependent variable, and it also describes the characteristics of the random and fixed effects used in the model. These results help explain the strength of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables and assess their statistical significance within the economic context of the study.

Table 10.

Results of estimating the regression model using the random-effects method (GLS Regression).

The Random-Effects (EGLS) model presents estimates of the impact of independent variables on economic growth (LNRGDP) to estimate differences between countries and time periods. The table shows that the constant (C) reached 25.25478 with a standard error of 0.4543, t = 55.591, and p-value = 0.0000, making it highly significant at the 1% level. This suggests that real GDP, in the absence of the influence of other variables, is approximately 25.25. For the main independent variables, DIGI was found to have a highly significant positive effect (coefficient 0.003325, t = 3.929, p = 0.0001), with each one-unit increase in digitization associated with a 0.0033 increase in LNRGDP. The 95% confidence interval [0.001667, 0.004983] supports this conclusion. AI also showed a statistically significant positive effect at the 1% level (coefficient 0.066548, t = 3.067, p = 0.0026), indicating the contribution of AI applications to economic growth, with a 95% confidence interval [0.023904, 0.109192]. On the other hand, neither INV (coefficient 0.001373, t = 0.768, p = 0.4437) nor LAB (coefficient −0.001304, t = −0.266, p = 0.7904) showed a statistically significant effect, as confidence intervals were zero, indicating that these variables did not contribute to growth during the study period. HEDU, however, had a highly statistically significant positive effect at the 1% level (coefficient 0.003264, t = 4.603, p = 0.0000), further supporting the role of education in boosting real GDP. Furthermore, the DUMMY variable showed significance at the 5% level (coefficient 1.783206, t = 2.610, p = 0.0101), reflecting the importance of structural differences between countries in explaining variations in economic growth. This highlights why the random-effects model is more suitable than the fixed-effects model when including this type of variation. The overall model statistics reflect the explanatory power, with a weighted R-squared of 0.8005 and an adjusted R-squared of 0.7696. An F-statistic of 25.881 and a p-value of 0.0000 indicate the overall significance of the model. This analysis suggests that digitalization, artificial intelligence, and education are key drivers of sustainable economic growth, while investment and human capital remain insignificant in this context, thus confirming the study’s hypotheses regarding the importance of digital and educational technologies as growth catalysts.

The findings indicate that the impact of digitalization in developing countries remains limited compared to developed countries, highlighting the need for a phased approach to digital investment, starting with the development of digital infrastructure and human skills, and then expanding investments in artificial intelligence, to ensure maximizing the impact of digitalization on economic growth in a sustainable manner.

Table 11 below presents the results of the Hausman Correlated Random-Effects (CRV) test, a crucial step in estimating table models to determine whether a random-effects model is more suitable than a fixed-effects model. The null hypothesis of the test assumes that state-specific effects are not correlated with independent variables, making the RE model valid and efficient. The alternative hypothesis suggests a correlation between state-specific effects and independent variables, making the FE model more accurate for estimating coefficients.

Table 11.

Results of Hausman Test Comparing Fixed- and Random-Effects Models.

The overall test result (Chi-Sq = 8.6017, d.f. = 5, p-value = 0.126) indicates insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis at the 5% significance level, suggesting that the Random-Effects model is generally appropriate for the data used in this study. Detailed comparisons of the FE and RE estimates for each variable show that DIGI, INV, LAB, and HEDU have non-significant differences (p-value > 0.05), confirming that the RE model provides efficient estimates for these variables without significant bias. In contrast, AI shows a significant difference between FE and RE (p-value = 0.0065 < 0.01), indicating that its effect on GDP is related to state effects, and therefore, FE can be considered more accurate for estimating this variable.

From an econometric perspective, this test reflects the reality of the tablet data in the study: most economic factors (DIGI, INV, LAB, HEDU) can be modeled as random effects across countries and time periods, thus maintaining the efficiency of the estimates, while some specific variables, such as AI, require handling fixed effects to ensure accurate and unbiased estimates. These results support the study’s hypothesis that the impact of digitalization, AI, investment, employment, and education on economic growth varies from country to country, with a strong country-specific AI effect, while the remaining variables remain generalizable using the RE model.

For the null hypothesis (H0): There is no systematic difference between the estimates of the two models, meaning that the random model is appropriate (there is no correlation between the unobserved components and the explanatory variables).

For the alternative hypothesis (H1): There is a systematic difference, meaning that the fixed model is appropriate.

Test statistic value = 8.601741.

p-value = 0.1260 (i.e., more than 0.05).

There are systematic differences between the estimates of the two models, meaning that the explanatory variables are related to unobserved factors (such as fixed characteristics within each country, such as the institutional framework, organizational culture, etc.). To determine the most appropriate model for estimating the relationship between the studied variables, the Hausmann test was performed to compare the fixed-effects (FE) model with the random-effects (RE) model. The null hypothesis (H0) states that there is no systematic difference between the coefficient estimates in the two models, implying that the random-effects model is consistent and appropriate. The alternative hypothesis (H1) posits the existence of systematic differences, suggesting that the fixed-effects model is more suitable. As shown in Table 11, the test statistic was 8.601741 with 5 degrees of freedom, and the p-value was 0.1260. Since this value is greater than the traditional significance level of 0.05, we do not reject the null hypothesis, indicating a lack of strong evidence for a systematic difference between the FE and RE estimates for most variables.

Looking at the individual variables, only the artificial intelligence (AI) variable showed a significant difference (p = 0.0065), while the other variables (DIGI, INV, LAB, HEDU) did not show significant differences (p > 0.05). This suggests that the random-effects model provides consistent estimates for most variables, while the fixed-effects model offers more accurate estimates for the AI variable. Given the high rho coefficient of the fixed-effects model (ρ ≈ 0.99) and the structural differences between countries, the fixed-effects model remains important for capturing unobserved country-specific differences, such as institutional and cultural factors. However, the Hausmann test results indicate that the random-effects model is statistically justified for most variables and provides high efficiency without bias. Therefore, both models are robust and reliable, but the fixed-effects model is preferred when analyzing the impact of AI because of its potential association with unobserved country-specific factors, while the random-effects model is sufficient for the remaining variables. This balance ensures accurate estimates while controlling for unobserved differences between countries.

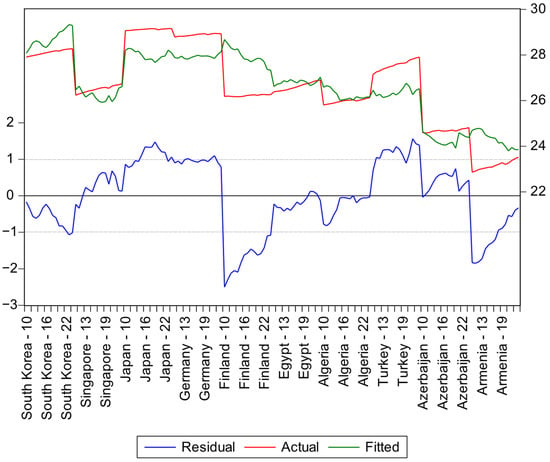

Figure 3 illustrates the graphical representation of actual, fitted, and residual values for the study variables over the period 2010–2024 for a sample of 10 countries (5 developed and 5 developing). The figure uses three colors—red for actual values, green for fitted values, and blue for residuals—to accurately show the difference between the actual and fitted values for each economic and technological variable. This representation aims to provide a comprehensive visual overview of how the fitted effects (FE) models fit the data, while also highlighting the degree of deviation between the fitted and actual values over time and across different countries.

Figure 3.

Graphic representation of current and estimated values for study variables. Source: Prepared by researchers based on outputs EViews 12.

Figure 3 demonstrates that the fixed-effects (FE) model accurately reflects temporal and variable patterns across countries. The estimated (fitted) values closely match the actual values for most variables, while the residuals remain limited, thus enhancing the reliability of the standard results. The figure also highlights the disparity between developed and developing countries. Developed countries achieve higher levels of digitalization (DIGI), artificial intelligence (AI), and education (HEDU), while developing countries exhibit a clear gap. This graphical representation reflects the strength of the statistical models used and transforms quantitative analysis into a visual tool for understanding digital economic dynamics. It reinforces the study’s conclusions regarding the impact of digitalization and technology on sustainable economic growth and the need for tailored policies for each country.

5. Discussion

The study results reveal a clear and sharp disparity between developed and developing countries regarding economic and technological variables during the period 2010–2024, indicating a digital and structural gap that directly impacts economic growth. This confirms the earlier hypothesis that differences in digitalization, artificial intelligence, and human capital play a crucial role in determining each country’s economic outcomes.

5.1. Digitalization (DIGI) and Economic Growth

The Digitalization Index ranged from 12.5 to 97.9, with a mean of 69.62 and a standard deviation of 22.30, reflecting significant variations in the levels of digital transformation among countries. The results of the fixed-effects (FE) model showed that digitalization is a fundamental factor with a significant positive impact on GDP, with GDP increasing with each substantial increase in the level of digitalization. This demonstrates that digital technology is not merely a tool for improving productivity, but a key driver of sustainable growth, particularly in developed countries with robust infrastructure and the capacity to rapidly adopt new technologies.

5.2. Artificial Intelligence (AI) as a Growth Catalyst

The AI variable recorded a mean of 1.857 and a standard deviation of 1.23, reflecting the varying levels of technological innovation among countries. The results showed that AI has a significant positive impact on GDP, confirming that investment in AI promotes long-term economic growth and increases global competitiveness. However, the impact of AI is stronger in developed countries compared to developing countries, highlighting the need to use a fixed-effects (FE) model to ensure an accurate estimate of the country-specific impacts. This aligns with the findings of Shanmugalingam et al. (2023) [90], which confirmed that AI adoption amplifies the productivity gap between developed and emerging economies.

The results indicate that the positive impact of the digitalization and artificial intelligence index on GDP reflects not merely accounting updates in national accounts systems, but a genuine improvement in economic productivity. This is underscored by the use of real GDP and fixed-effects models, which isolate methodological differences between countries and highlight the actual role of digital capital as a component of sustainable economic growth.

Developing a Practical Framework for Updating National Accounts Based on Standard Results

Based on these standard results, a practical framework was developed to update national accounts, reflecting the contribution of the digital economy and technological innovation to GDP. The standard results underpin the framework’s four key principles:

Classifying Digital Assets Based on Measurement Results: Using DIGI and AI data, digital activities with a significant impact on GDP, such as software, data, digital platforms, and artificial intelligence, were identified.

Estimating Digital Productivity Based on Measurements: Standard model results were used to estimate the contribution of these activities to GDP, controlling for structural and fixed variables using fixed-effects models to ensure high accuracy in the estimates.

Integrating Digital Indicators into GDP: Based on composite standard data for the period 2010–2024, composite indicators reflecting digital and technological contributions were created to be added to official national accounts and illustrate the true impact of the digital economy.

A measurement-based periodic updating mechanism: It is proposed that indicators be updated annually by national statistical agencies to reflect ongoing changes in digitalization, artificial intelligence, and human capital, thus transforming econometric analysis into a practical tool for planning and public policy.

This framework is a direct result of the economic measurements and models in the study. It is not merely theoretical but is based on econometric evidence to determine how digital productivity and technological innovation can be integrated into official national GDP accounts, thereby enhancing the reliability of the study’s conclusions and making them practically applicable.

5.3. Human Capital and Education (HEDU)

The education variable recorded a mean of 68.04 and a standard deviation of 21.7, demonstrating a significant positive impact on economic growth. These results confirm that improving the quality of education and linking it to digital and technical skills is essential for sustainable growth. In contrast, the size of the workforce (LAB) did not show a significant effect, indicating that quantity alone is insufficient; rather, competence and digital literacy are the decisive factors. This aligns with Katz & Jung (2021) [91], who highlighted that the quality of skills, not the size of the workforce, is the primary determinant of growth in digital economies.

5.4. Growth Stability and Macroeconomic Factors

Breusch–Pagan and VIF tests confirmed the absence of homogeneous variance or multicollinearity issues after constructing the composite indices, thus reinforcing the validity of the conclusions. Long-term stability tests (Pedroni) also confirmed a stable cumulative relationship between GDP and technological and educational variables, justifying the use of the fixed-effects (FE) model as the best representation of structural differences between countries.

5.5. The Gap Between Developed and Developing Countries and the DUMMY Variable

The DUMMY variable was used to distinguish developed countries (1) from developing countries (0). The analyses showed that developed countries benefit more from digitalization, artificial intelligence, and education than developing countries. This significant structural disparity underscores the need for specialized national policies aimed at bridging the digital divide, fostering innovation, and maximizing the economic benefits of technological transformation in emerging economies.